Abstract

Objective

This study estimates the prevalence of fecal incontinence (FI) in overweight and obese women with urinary incontinence and compares dietary intake in women with and without FI.

Study Design

A total of 336 incontinent and overweight women in the Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise clinical trial were included. FI was defined as monthly or greater loss of mucus, liquid, or solid stool. Dietary intake was quantified using the Block Food Frequency Questionnaire.

Results

Women had a mean (± SD) age of 53 ± 10 years, body mass index of 36 ± 6 kg/m2, and 19% were African American. Prevalence of FI was 16% (n = 55). In multivariable analyses, FI was independently associated with low fiber intake, higher depressive symptoms, and increased urinary tract symptoms (all P < .05).

Conclusion

Overweight and obese women report a high prevalence of monthly FI associated with low dietary fiber intake. Increasing dietary fiber may be a treatment for FI.

Keywords: diet, fecal incontinence, female, food frequency questionnaire, obesity, stress incontinence, urge incontinence, urinary incontinence, weight loss

Fecal incontinence (FI) is a common condition that results in significant physical and psychological disability.1-3 The reported prevalence of FI varies considerably depending on the population studied and definition of incontinence. In population-based samples, the prevalence of FI has been reported to be 2-12% depending on the age of the cohort.1-6

More than 50% of US women are overweight (body mass index [BMI], 25-30 kg/m2) or obese (BMI, ≥ 30 kg/m2), and the prevalence of obesity is increasing by almost 6% per year.7,8 Although there are limited studies evaluating risk factors for FI, evidence suggests that obesity may be one of the strongest modifiable independent risk factors for FI in women.4,9-11 In population-based observational studies, FI is reported to be approximately 50% more prevalent in obese compared with normal-weight women.4,9-11 Other potential risk factors for FI in women include: age, parity, mode of delivery, impairments in activities of daily living, and comorbid diseases.4-6,9,12

Although there are minimal data on the effect of weight loss on FI, clinical trials and observational studies suggest that weight loss may be an effective treatment for urinary incontinence (UI) and may prevent incident UI in women.13-17 Women who undergo bariatric surgery or nonsurgical weight loss have had improvements in UI and FI frequency and severity.13,17,18 There are few data to support improved outcomes with dietary changes for FI. Dietary modifications are often included as an early treatment strategy for FI, but minimal data exist to guide the recommendations on types of dietary changes.19 Increasing soluble fiber intake has been shown to improve FI.20 Overweight and obese women are reported to consume less dietary fiber than normal-weight, age- and height-matched women.21 However, more data are needed on the effect of increasing dietary fiber on FI. Therefore, we estimated the prevalence of FI and identified independent risk factors associated with FI, specifically focusing on dietary intake, at baseline in a cohort of overweight and obese women with UI participating in a weight-loss trial.

Materials and Methods

Design

The Program to Reduce Incontinence by Diet and Exercise (PRIDE) was a multicenter, randomized, clinical trial to evaluate the effects of weight reduction as a treatment for UI in overweight and obese women. The 2 clinical sites were Brown University, Providence, RI, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL. Data were collected, managed, and analyzed at the University of California at San Francisco, CA. In brief, the weight-loss program lasted 6 months (lifestyle and behavioral change) and included a control group (instructional handouts with brief sessions of diet and exercise). Women were recruited through newspaper and television advertisements, flyers, and clinics at both participating sites. Participants were given a total of $100 for completion of the study. This study is a pre-planned secondary analysis of the women who were randomized at baseline (n = 338). Two participants were excluded from this analysis because their dietary data were outside of possible ranges for analysis.

Women at least 30 years of age with a BMI of 25-50 kg/m2 who reported 10 or more UI episodes on a 7-day voiding diary at baseline were eligible for the study. Selected exclusion criteria included urinary tract infection, 4 or more urinary tract infections in the preceding year, incontinence of neurologic or functional origin, prior incontinence or urethral surgery, significant medical conditions of the genitourinary tract, pregnancy, and medical conditions such as type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes requiring medical therapy, uncontrolled hypertension, and history of coronary heart disease. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each site and written consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

Measures

FI was defined as monthly or more frequent loss of mucus, liquid, or solid stool. The question used to ascertain FI was “during the past 3 months, how often did you experience any of the following unexpected or accidental bowel leakage, even a small amount?” The levels of response for gas, mucus, liquid bowel movement, or solid bowel movement were: “never,” “less than monthly,” “monthly (once or more each month),” “weekly (≥ 1 each week),” or “daily (≥ 1 each day).” Although this is similar to the validated FI Severity Index, this scale uses different categories of frequency of stool loss.22

The Block Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) is a 110-item self-administered questionnaire validated for the estimation of usual and customary intake of nutrients and food groups in women.23 It takes 30-40 minutes to complete. Women recorded how many times per day, week, or month they consumed specific food items and the approximate serving size with pictures provided to enhance accuracy of quantification on serving size. Verbal instruction was provided by registered dietitians on completion of the FFQ. Completed FFQs were sent to Berkley Nutrition Services (Berkley, CA) for data scanning and analysis.24 A complete nutrient analysis including macronutrients and micronutrients was provided. Additional categories were determined for total fat, dietary cholesterol, protein, carbohydrates, and dietary fiber based on the distribution of the values for each specific nutrient. Specifically, fiber intake was defined as: low (≤ 10 g/day), moderate (11-25 g/day), or high (> 25 g/day). To better characterize sources of dietary fiber, fiber from vegetables and fruit, beans, and grains were analyzed separately.

Possible predictor variables for FI were identified a priori for this secondary analysis. Demographic characteristics and medical, behavioral, and incontinence histories were ascertained using self-reported questionnaires. BMI was calculated with measured weight in kilograms and height in meters squared (kg/m2). Participants reported hypertension, stroke, diabetes, and frequency of taking supplemental fiber for bowel movements. Obstetric and gynecologic variables included self-reported parity and prior hysterectomy and surgery.

UI episodes were self-reported on a 7-day voiding diary with each incontinent episode classified by clinical type (urge, stress, other).25,26 Incontinence type was then classified during analysis as stress only; stress predominant (stress episodes comprised at least 2/3 of total); urge only; urge predominant (urge episodes comprised at least 2/3 of total); or mixed (if at least 2 types were reported but no type comprised at least 2/3 of the total). A modified Sandvik Severity Index was used to describe urine leakage as: “slight,” “moderate,” “severe,” or “very severe.”27 The American Urologic Association (AUA) symptom index score has 7 questions related to lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and has been validated for use in women.28 Scores range from 0-35, where higher scores represent more symptoms. Categories are defined as mild (score 0-7), moderate (score, 8-19), or severe (score, 20-35). UI-specific quality-of-life and burden were assessed with the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI).29 Higher scores on the IIQ and the UDI represent greater impact and symptom burden, respectively. Health-related quality-of-life was measured using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36.30 The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to measure self-reported depressive symptoms. It is a 21-item questionnaire that is scored from 0-63, with higher scores reflecting greater depressive symptoms.31

Data analysis

We compared overweight/obese women with UI to overweight/obese women with UI and monthly FI with regard to selected factors using means or frequency distributions. To determine significant differences between the 2 groups, we used analysis of variance for normally distributed continuous variables, ranked analysis of variance for nonnormally distributed continuous variables, and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate bivariate associations of those factors with any FI. A significance level of < 0.1 was used to select potential factors to include in the initial multivariable logistic regression model in which monthly FI was the dependent variable. The initial multivariable analysis included: age; race; BMI (1-U scale); AUA symptom index (10-U scale); BDI (10-U scale); total fat, cholesterol, and protein; and low fiber intake (< 10 g/day). Age was retained in the final multivariable model because of the possible impact of age as a confounder for FI. All analyses were performed using software (SAS Version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

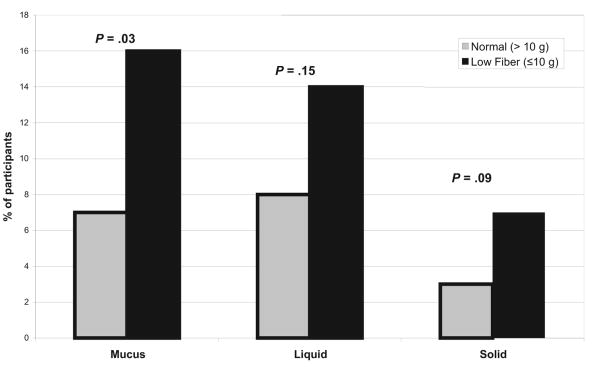

Overweight and obese women with UI participating in the PRIDE study (n = 336) had a mean age (± SD) of 53 ± 10 years, weighed 95 ± 16 kg, and 19% were African American. The prevalence of monthly or greater FI was 16%. Liquid stool incontinence was the most common type of incontinence reported by the women (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Prevalence of fecal incontinence by type and fiber intake.

Women with FI (n = 55) were more likely to have lower weight (P = .01), more severe UI (P = .01), increased AUA symptom score (more LUTS; P < .001), greater impact on the mental component of the Short Form 36 score (worse functioning; P = .001), and higher BDI score (more depressive symptoms; P = .009) (Table 1). There were no differences between groups in mean BMI, medical conditions (diabetes and hypertension), obstetric or gynecologic history, or scores on UI-specific impact measures (UDI and IIQ). In addition, no differences were seen by type of UI (stress, urge, or mixed) among women with or without FI.

TABLE 1. Sociodemographic and medical characteristics by fecal incontinence status.

| Report Detailed and/or summarized report | No FI | FI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| All participants | 281 | 84 | 55 | 16 | |

| Age, y, mean (±SD) | 53 | ± 10 | 54 | ± 10 | .680 |

| White race | 218 | 78 | 44 | 80 | .690 |

| Education > high school | 245 | 87 | 46 | 84 | .479 |

| BMI, kg/m,2 mean (± SD) | 37 | ± 6 | 35 | ± 5 | .109 |

| Weight, kg, mean (± SD) | 98 | ± 17 | 92 | ± 16 | .014 |

| Hypertension | 107 | 38 | 17 | 31 | .314 |

| Stroke | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | .268 |

| Diabetes | 8 | 3 | 2 | 4 | .753 |

| Flatus incontinence (monthly) | 107 | 38 | 41 | 75 | < .001 |

| Supplemental fiber for BM (daily) | 11 | 4 | 5 | 9 | .186 |

| Parous | 258 | 92 | 47 | 85 | .256 |

| No. of total live births, mean (± SD) | 2 | ± 1 | 2 | ± 1 | .387 |

| Postmenopausal | 144 | 51 | 32 | 58 | .292 |

| Hysterectomy | 77 | 27 | 20 | 36 | .376 |

| Sandvik severity (modified) | .012 | ||||

| Moderate | 35 | 14 | 2 | 4 | |

| Severe | 144 | 56 | 24 | 47 | |

| Very severe | 76 | 76 | 25 | 49 | |

| AUA symptom index | .001 | ||||

| Mild (0-7) | 97 | 97 | 11 | 20 | |

| Moderate (8-19) | 172 | 61 | 35 | 64 | |

| Severe (20-35) | 12 | 4 | 9 | 16 | |

| Incontinence Impact Questionnaire score, mean (± SD) | 105 | ± 69 | 126 | ± 79 | .088 |

| Urodynamic Distress Inventory score, mean (± SD) | 164 | ± 54 | 174 | ± 43 | .186 |

| SF-36 mental component score, mean (± SD) | 51 | ± 9 | 45 | ± 12 | .001 |

| SF-36 physical component score, mean (± SD) | 49 | ± 8 | 47 | ± 9 | .308 |

| Beck Depression Inventory score, mean (± SD) | 7 | ± 5 | 10 | ± 8 | .009 |

AUA, American Urologic Association; BM, bowel movement; BMI, body mass index; FI, fecal incontinence; SF, Short Form.

Data presented as N (%) unless otherwise noted.

Statistical analysis included χ2 analysis for categorical variables, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and ranked ANOVA for difference in means.

Dietary intake from FFQ was compared between the women with and without FI (Table 2). When fiber intake was categorized as high (≥ 25 g/day), moderate (10-25 g/day), and low (≤ 10 g/day), low dietary fiber intake was the only dietary factor that was significantly different (P = .01) among the women with FI. Categorization of dietary intake of cholesterol, protein, or fat did not result in any significant differences among women with FI. No significant differences (P > .05) were seen in specific dietary types of fiber, such as vegetable/fruit fiber, fiber from beans, or fiber from grains. A higher proportion of women had a low level of fiber intake (≤ 10 g/day) for each specific type of FI: mucus (P = .03), liquid (P = .15), and solid (P = .09) stool incontinence (Figure 1).

TABLE 2. Dietary intake of women with and without fecal incontinence.

| Characteristic Report Detailed and/or summarized report | No FI | FI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| All participants, n | 281 | 84 | 55 | 16 | |

| Calories, Kcal/day, mean (± SD) | 2086 | 923 | 2057 | 1128 | .323 |

| Total fat, g/day, mean (± SD) | 97 | 52 | 92 | 61 | .177 |

| Saturated fat, g/day, mean (± SD) | 27 | 14 | 26 | 16 | .216 |

| Dietary cholesterol, mg/day, mean (± SD) | 236 | 129 | 221 | 129 | .371 |

| Protein, g/day, mean (± SD) | 81 | 37 | 75 | 40 | .124 |

| Carbohydrate, g/day, mean (± SD) | 228 | 102 | 239 | 127 | .853 |

| Dietary fiber, g/day, mean (± SD) | 18 | 9 | 17 | 10 | .190 |

| Dietary fiber categories | .010 | ||||

| Low (< 10 g/day), n (%) | 42 | 15 | 16 | 29 | |

| Moderate (10-25 g/day), n (%) | 188 | 67 | 29 | 53 | |

| High (> 25 g/day), n (%) | 51 | 18 | 10 | 8 | |

FI, fecal incontinence.

Statistical analysis included χ2 analysis for categorical variables, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and ranked ANOVA for difference in means.

All variables that were associated with FI (P < .1) (Table 1) in univariate analyses were included in a multivariable model comparing women reporting monthly or greater FI with no FI (Table 3). Factors independently associated with monthly or greater FI were low fiber intake (odds ratio [OR], 2.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3-5.4), higher depression symptoms on the BDI (OR, 2.1 per 10-point increase in score; 95% CI, 1.3-3.5), and increased LUTS on the AUA symptom score (OR, 1.9 per 10-point increase in score; 95% CI, 1.1-3.3). Increasing BMI was marginally protective for FI in our population (OR, 0.9 per 1 kg/m2; 95% CI, 0.9-1.0). Age, parity, and prior hysterectomy were not independent predictors for FI in this study. No associations with other dietary variables were seen among the women with and without FI.

TABLE 3. Factors associated with fecal incontinence.

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age/5 y | 1.1 | 0.9-1.2 | .44 |

| BMI/1 kg/m2 | 0.9 | 0.9-1.0 | .01 |

| AUA symptom index | 1.9 | 1.1-3.3 | .03 |

| Beck Depression Inventory score/10 U | 2.1 | 1.3-3.5 | .003 |

| Low fiber (≤ 10 g/day) | 2.6 | 1.3-5.4 | .008 |

AUA, American Urologic Association; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Comment

The prevalence of FI in overweight and obese women (16%) in this study is higher than that seen in population-based epidemiologic studies (4-7%),1,2,4,6,9 but similar to studies including women with combined UI and FI (9-16%)32,33 and among morbidly obese women undergoing bariatric surgery (17%).34

Overweight and obese women with FI were more likely to have a lower dietary intake of fiber than women without FI. This study shows an independent association between dietary intake recorded on a FFQ with FI. In a case-control study among 39 adults with FI and age- and sex-matched continent control subjects, no differences in dietary intake of fiber recorded on an 8-day food diary were observed.20 This finding may be a result of reporting differences on a food diary vs the use of a FFQ. However, others have found that nutrition estimates from FFQ and short-term dietary recall are similar.35

Intake of dietary fiber is modifiable, suggesting that a dietary program of higher fiber intake may be a treatment option for FI. Because dietary fiber may improve FI by increasing stool weight and improving stool consistency, recommending dietary fiber intake may improve FI.36

We observed several risk factors for FI in our cohort of overweight and obese women that are similar to those found in studies that included both normal-weight and obese women,4,9 including depressive symptoms, increased urinary tract symptoms, and incontinence symptoms. FI and depressive symptoms have been linked in other studies, but more information is needed to determine a causal relationship.5,9 Among women in a clinical intervention trial for stress UI, the co-occurrence of FI was associated with increased UI symptoms.33 We found that increased scores on the AUA symptom index were associated with FI; however, we did not find an association between UI symptom burden on the IIQ or the UDI and FI in multivariable analysis. In contrast to population-based studies on FI, we did not find an independent association of age, parity, or other comorbid conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and stroke with FI, although these chronic conditions were rare in our study population.4,5,9

Although we found that BMI was weakly protective for FI, population-based studies have observed that BMI is an independent risk factor for FI.15,34 Our different findings may be because all women in our study were overweight or obese, with no normal-weight control group. Because obesity is a preventable and modifiable condition, the prospect of improved FI may help motivate women to undertake difficult lifestyle and dietary changes. FI is a multifactorial condition that may result from anatomic factors related to the pelvic floor and anal sphincters, sensory factors in the perception of defecation, and functional factors related to stool consistency. Conditions that cause increased abdominal pressure (obesity), increased intestinal motility or loose stool (diabetes and dietary intake), and sphincter or pelvic floor weakness from an anatomic defect or nerve damage (obstetric injury and diabetes) may all contribute to FI, as do other pelvic floor disorders.37 When looking further at subgroup analysis (data not shown), no significant differences were found for low fiber intake (≤ 10 g/day) and BMI categories (overweight 25 to < 30, obese 30 to < 40, and morbidly obese ≥ 40). Further data are needed among women with FI who have varying degrees of obesity.

Our study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study is cross-sectional and thus cannot determine causal associations. Second, fiber intake on the FFQ was defined by self-report, which may have underestimated and overestimated intake and introduced recall basis for the frequency of specific types of food for women with FI. Third, we defined FI to include incontinence of mucus stool, which inflates our observed FI prevalence. However, scales that measure severity of FI usually include incontinence of mucus as part of the total score.22 No data were collected on the presence of irritable bowel syndrome, which may also play a role on the existence and impact of FI in these women. Also, overweight and obese women with more severe UI, a risk factor for FI, may have been more motivated to participate in a weight-loss study because of a larger symptom burden, thus introducing a participation bias. Finally, the participants in the study were generally healthy, community-dwelling volunteers enrolled in a randomized clinical trial, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

In summary, FI affected more than 15% of overweight and obese women with UI in the PRIDE trial. Thus, FI is more common than most medical conditions. Because rates of dual incontinence are high in this population, women with UI should be asked about symptoms of FI. Because dietary fiber intake is a modifiable risk factor for FI, women should also be asked about dietary fiber intake and may be encouraged to increase fiber to the recommended daily allowance (20-25 g/day). Future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of dietary modification on FI in overweight and obese women.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grant numbers U01 DK067860, U01 DK067861, and U01 DK067862 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Funding was also provided by the Office of Research on Women's Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This research was presented at the 29th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Urogynecologic Society, Chicago, IL, Sept. 4-6, 2008.

References

- 1.Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, et al. Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA. 1995;274:559–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanishi N, Tatara K, Shinsho F, et al. Mortality in relation to urinary and fecal incontinence in elderly people living at home. Age Ageing. 1999;28:301–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. US householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders: prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varma M, Brown J, Creasman J, et al. Fecal incontinence in females older than aged 40 years: who is at risk? Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:841–51. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quander CR, Morris MC, Melson J, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with fecal incontinence in a large community study of older individuals. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:905–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.30511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melville JL, Fan MY, Newton K, et al. Fecal incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2071–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erekson EA, Sung VW, Myers DL. Effect of body mass index on the risk of anal incontinence and defecatory dysfunction in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:596e1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altman D, Falconer C, Rossner S, et al. The risk of anal incontinence in obese women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1283. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waetjen LE, Liao S, Johnson WO, et al. Factors associated with prevalent and incident urinary incontinence in a cohort of midlife women: a longitudinal analysis of data. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:309–18. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subak LL, Whitcomb E, Shen H, et al. Weight loss: a novel and effective treatment for urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2005;174:190–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162056.30326.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, et al. Are smoking and other lifestyle factors associated with female urinary incontinence? The Norwegian EPINCONT study. BJOG. 2003;110:247–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melville JL, Katon W, Delaney K, et al. Urinary incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:537–42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townsend MK, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, et al. BMI, waist circumference, and incident urinary incontinence in older women. Obesity. 2008;16:881–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown JS, Wing R, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Lifestyle intervention is associated with lower prevalence of urinary incontinence: the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:385–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgio KL, Richter HE, Clements RH, et al. Changes in urinary and fecal incontinence symptoms with weight loss surgery in morbidly obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1034–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000285483.22898.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madoff RD, Parker SC, Varma MG, et al. Fecal incontinence in adults. Lancet. 2004;364:621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bliss DZ, Jung HJ, Savik K, et al. Supplementation with dietary fiber improves fecal incontinence. Nurs Res. 2001;50:203–13. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis JN, Hodges VA, Gillham MB. Normal-weight adults consume more fiber and fruit than their age- and height-matched overweight/obese counterparts. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:833. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Patient and surgeon ranking of the severity of symptoms associated with fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence severity index. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1525–32. doi: 10.1007/BF02236199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boucher B, Cotterchio M, Kreiger N, et al. Validity and reliability of the Block98 food-frequency questionnaire in a sample of Canadian women. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:84–93. doi: 10.1079/phn2005763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Block G, Sinha R, Gridley G. Collection of dietary-supplement data and implications for analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:232–9S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.1.232S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardization of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardization subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61:37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wyman JF, Choi SC, Harkins SW, et al. The urinary diary in evaluation of incontinent women: a test-retest analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:812–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandvik H, Seim A, Vanvik A, et al. A severity index for epidemiological surveys of female urinary incontinence: comparison with 48-hour pad-weighing tests. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:137–45. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:2<137::aid-nau4>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scarpero HM, Fiske J, Xue X, et al. American Urological Association symptom index for lower urinary tract symptoms in women: correlation with degree of bother and impact on quality of life. Urology. 2003;61:1118. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shumaker S, Wyman J, Uebersax J. Health related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the incontinence impact questionnaire and the urogenital distress inventory. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:291–306. doi: 10.1007/BF00451721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware J, Snow KK, Kosinski M. SF-36 health survey; manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. Beck Depression Inventory. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawrence JM, Lukacz ES, Nager CW, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling women. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:678–85. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181660c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markland AD, Kraus SR, Richter HE, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of fecal incontinence in women undergoing stress incontinence surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:662e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richter HE, Burgio KL, Clements RH, et al. Urinary and anal incontinence in morbidly obese women considering weight loss surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1272–7. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187299.75024.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, et al. Measurement characteristics of the women's health initiative food frequency questionnaire. Ann Epidemiol. 1999;9:178. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitehead WE, Wald A, Norton NJ. Treatment options for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:131–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02234835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greer WJ, Richter HE, Bartolucci AA, Burgio KL. Obesity and pelvic floor disorders: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:341–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817cfdde. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]