Abstract

The utility and effectiveness of routine health information systems (RHIS) in improving health system performance in developing countries has been questioned. This paper argues that the health system needs internal mechanisms to develop performance targets, track progress, and create and manage knowledge for continuous improvement. Based on documented RHIS weaknesses, we have developed the Performance of Routine Information System Management (PRISM) framework, an innovative approach to design, strengthen and evaluate RHIS. The PRISM framework offers a paradigm shift by putting emphasis on RHIS performance and incorporating the organizational, technical and behavioural determinants of performance. By describing causal pathways of these determinants, the PRISM framework encourages and guides the development of interventions for strengthening or reforming RHIS. Furthermore, it conceptualizes and proposes a methodology for measuring the impact of RHIS on health system performance. Ultimately, the PRISM framework, in spite of its challenges and competing paradigms, proposes a new agenda for building and sustaining information systems, for the promotion of an information culture, and for encouraging accountability in health systems.

Keywords: Routine health information system, health management information system, health system performance, culture of information, knowledge management, learning organization

KEY MESSAGES.

The PRISM framework, an innovative approach to design, strengthen and evaluate routine health information systems (RHIS), emphasizes RHIS performance and incorporates organizational, technical and behavioural determinants of performance.

Four PRISM tools are used to measure RHIS performance, processes and determinants and their relationships described under the PRISM framework.

The application of the PRISM framework and its tools in various countries has shown that they produce consistent and valid results.

Introduction

In recent times of resource constraints, good governance, transparency and accountability have become the mantra of development, and consequently more attention is given to strengthening evidence-based decision-making and information systems. Also, the emphasis on tracking Millennium Development Goals (van Etten et al. 2005) and the practice of performance-based release of funding requested by international funding agencies, such as the Global Alliance on Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria (GFTAM), require increasing amounts of quality information. This trend is reinforced in the health sector by emerging infectious diseases and environmental disasters, which need timely information for action.

Recently the Health Metrics Network (HMN) was established as an international network to increase the availability and use of timely and accurate health information from a variety of data sources (HMN Secretariat 2006). Debates abound at different forums regarding which data source is preferable for developing and tracking health system targets, documenting best practices or effectiveness of interventions, and identifying gaps in performance. It is argued (personal communications to authors at various meetings) that household and facility surveys yield better quality information than self-reported routine health information systems (RHIS) or health management information systems (HMIS)1 because of more objectivity and less bias. Others perceive RHIS to be costly, producing low quality and mostly irrelevant information (Mutemwa 2006), thereby contributing less to decision-making processes. The missing point in the debate is that each method of data collection serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and weaknesses. Further, there is no evidence that a third party survey assures better accountability or improvement in health system performance. Performance remains an organizational issue and needs to be dealt with as such. The RHIS allows organizational members to track their progress routinely in meeting organizational objectives, including patient management objectives, for which data cannot be collected otherwise (Lippeveld et al. 2000). Health system managers have no substitute for routine information in terms of monitoring progress towards achieving service coverage objectives and managing associated support services (e.g. logistics, human resources, finance) for their local target populations. Thus, the focus of debate should shift from abandoning RHIS over other sources of data to showing how to improve RHIS.

This paper describes the strengths and weaknesses of existing RHIS and presents an innovative approach to overcome the shortcomings of past RHIS design efforts by proposing the Performance of Routine Information System Management (PRISM) framework for designing, strengthening and evaluating RHIS. We first propose a clear definition of RHIS performance, which was lacking in earlier RHIS design efforts. We then discuss the influence on RHIS performance of three categories of determinants—technical, organizational and behavioural—as well as the relationship between RHIS performance and health system performance. The next sections briefly present the PRISM tools as well as examples of their application in multiple countries. Lastly, the paper discusses various competing paradigms, their pros and cons, as well as PRISM framework limitations and contributions to state of the art RHIS development and improved health system performance.

Background

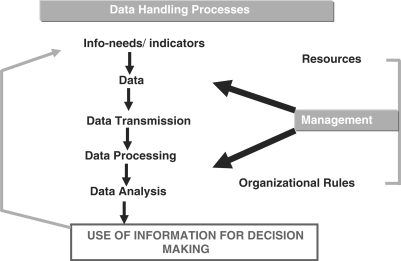

In the 1990s, Lippeveld et al. (2000) and others promoted the development of routine health information systems in developing countries, emphasizing management of the health system. The core components of the information system (Figure 1) were described as the development of indicators based on management information needs, data collection, transmission, and processing and analysis, which all lead to information use. The authors assumed that if senior management provided the resources (finances, training material, reporting forms, computer equipment, etc.) and developed organizational rules (RHIS policies, data collection procedures, etc.) then the information system would be used and sustained. During that same period, international donors such as UNICEF and USAID heavily influenced health information system development. Despite paying attention to management information needs, the information systems were modelled upon the epidemiological surveillance system, focusing on a single disease (e.g. diarrhoeal disease, or acute respiratory disease) or on a group of diseases (e.g. the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI). This led to the creation of a series of vertical information systems and a cadre outside of the health management system to manage information systems. It also caused a dichotomy between information system professionals (data people) and health systems managers (action people) who could not understand each other's role and responsibilities, and the need to work together (Lind and Lind 2005).

Figure 1.

Health information system (HIS) components diagram

By the late 1990s and early 21st century, increasing evidence showed that routine information systems were not producing the intended results. Studies showed that data quality was poor in Mozambique and Kenya (Mavimbe et al. 2005; Odhiambo-Otieno 2005a), while use of information for planning and decision-making was found to be weak in Brazil and South Korea (Chae et al. 1994; da Silva and Laprega 2005). Many factors contributed to under-performing information systems, such as difficulty in calculating indicators because of poor choices for denominators in DR Congo (Mapatano and Piripiri 2005) and inadequacies in computerization, data flow, human and capital resources, and low management support in Kenya (Odhiambo-Otieno 2005a). Nsubuga et al. (2002) in Tanzania found weaknesses in the areas of standardized case definitions, quality of reporting, analysis, supervision and feedback. Rotich et al. (2003) and Kamadjeu et al. (2005) noted that user involvement, the choice of a standardized terminology, a pre-existing culture of data collection and leadership remain crucial issues for RHIS financial and technical sustainability.

Another problem in strengthening information systems was the scarcity of structured evaluations for best practices in information systems (Mitchell and Sullivan 2001; Tomasi et al. 2004). Our literature search in Medline between 1990 and 2006 found very few papers on information systems evaluation in developing countries. Odhiambo-Otieno (2005a) suggests that lack of evaluation of district-level RHIS has been partly due to the lack of defined criteria for evaluating information systems.

PRISM framework

Information system development until recently relied mainly on technical approaches (Churchman 1971; Gibbs 1994), from assessing information needs to developing data analysis and presentation tools, and using information and communication technology (ICT), with little recognition of the effects of contextual issues. Information systems were defined as a set of related elements (van Gigch 1991) without any consensus on defining and measuring the systems’ performance. Attention was given neither to how people react to and use information systems for problem solving or self-regulating their performance (behavioural factors), nor to organizational processes for creating an enabling environment for using and sustaining RHIS. When attention was given to these factors (Clegg et al. 1997; Malmsjo and Ovelius 2003), there was no attempt to put them in a coherent framework to understand their effects on RHIS processes and performance.

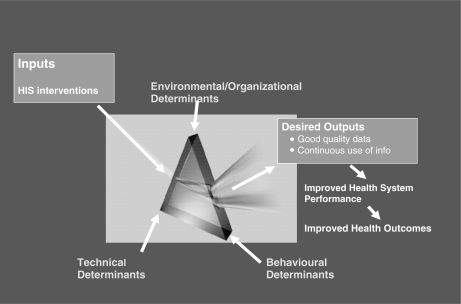

In response to this need, and based on empirical work by Hozumi et al. (2002), Lafond and Field (2003) presented a draft Prism framework at an international workshop on district HIS in South Africa (RHINO 2003). In the absence of an ‘operational’ definition of RHIS performance in the literature, RHIS performance was defined as ‘improved data quality and continuous use of information’. It was stated that RHIS performance is affected by three categories of determinants: technical, behavioural and environmental/organizational (Figure 2). The RHIS performance occurs within an environment/organizational setting. Organizational members need motivation, knowledge and skills (behavioural factors) to perform RHIS tasks, and specialized technical know-how/technology (technical) is required for timely analysis and reporting.

Figure 2.

Prism framework

While the draft Prism framework provided a new direction in analysing RHIS performance, further work was needed to delineate the boundaries of the technical, behavioural and organizational determinants, and to specify the relationship among the three categories to measure their relative impact on RHIS performance. There was also a need to clarify the role of RHIS processes (Figure 1) on RHIS performance.

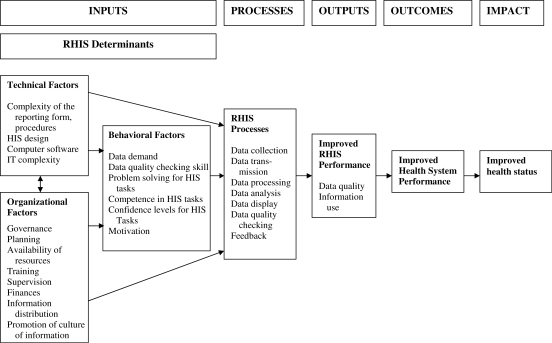

We responded to this need by shifting from Prism to the PRISM (Performance of Routine Information Systems Management) framework, focusing on RHIS performance management. A routine health information system is composed of inputs, processes and outputs or performance, which in turn affect health system performance and consequently lead to better health outcomes (Figure 3). A RHIS pays more attention to the internal determinants. Therefore, the environmental/organizational category is renamed as organizational factors, while environmental factors are considered to be constraints under which every RHIS works and has little control over.

Figure 3.

PRISM (Performance of Routine Information System Management) framework

The PRISM framework brings a paradigm shift in RHIS design and evaluation by considering RHIS to be a system with a defined performance (Deming 1993), and by describing the organizational, technical and behavioural determinants and processes that influence its performance. The framework implies continuous improvement of RHIS performance by analysing the role of each of these determinants and by identifying appropriate interventions to address determinants that negatively influence RHIS performance. Through broader analysis of organizational information needs, it also hinders fragmentation of the existing RHIS and promotes a more integrated approach to information system development.

The PRISM framework states that RHIS performance is affected by RHIS processes, which in turn are affected by technical, behavioural and organizational determinants (Figure 3). It shows that behavioural determinants have a direct influence on RHIS processes and performance. Technical and organizational determinants can affect RHIS processes and performance directly or indirectly through behavioural determinants. For example, the complexity of data collection forms (technical) could affect performance directly or indirectly by lowering motivation. Thus, the PRISM framework delineates the direct and indirect relationships of the determinants on RHIS performance and measures their relative importance. The PRISM framework also opens opportunities for assessing the relationships among RHIS performance, health system performance, and health status.

RHIS performance

As originally proposed, RHIS performance is defined as improved data quality and continuous use of information. Data quality is further described in four dimensions: relevance, completeness, timeliness and accuracy (Lippeveld et al. 2000). Relevance is assessed by comparing data collected against management information needs. Completeness is measured not only as filling in all data elements in the facility report form, but also as the proportion of facilities reporting in an administrative area (e.g. province or district). Timeliness is assessed as submission of the reports by an accepted deadline. Accuracy is measured by comparing data between facility records and reports, and between facility reports and administrative area databases, respectively.

Use of information depends upon the decision power of the people and the importance given to other considerations despite the availability of information (Grindle and Thomas 1991; Sauerborn 2000). However, without assessing use of information, it is difficult to know whether a RHIS is meeting its intended objectives, improving evidence-based decision-making, and consequently leading to better health system performance. Therefore, efforts were made to operationalize use of information for measurement (HISP 2005; MEASURE Evaluation 2005). The PRISM framework defines use of information employing criteria such as use of information for identifying problems, for considering or making decisions among alternatives, and for advocacy. Based on this definition, a RHIS performance diagnostic tool was developed for measuring RHIS performance.

By defining and measuring RHIS performance, the PRISM framework draws attention to setting and achieving targets, which act as motivators (Locke et al. 1986) to self-regulate and continuously improve performance (McLaughlin and Kaluzny 1994). The framework identifies the location of responsibility for actions leading to better accountability. However, performance is considered a system's characteristic (Berwick 1996), thus it needs to be seen in conjunction with system processes and the determinants affecting them.

RHIS processes

Processes are the backbone of performance (Donabedian 1986). RHIS processes described under Figure 1 (Lippeveld et al. 2000) are accepted norms. However, in the PRISM framework, use of information is considered an output rather than a process (Figure 3). Also, data quality indicators such as completeness and timeliness are used for assessing processes of data collection and transmission, which create confusion between data quality as an output and RHIS processes. The PRISM framework clarifies this confusion by adding specific indicators for measuring RHIS processes, such as existence of procedures for data collection and transmission and consequences for not following these procedures.

The PRISM framework draws attention to neglected RHIS processes, such as checking data quality, displaying of information and giving feedback, and makes them part of the accepted norms. Measurement is key for tracking improvements (Berwick 1996). Assuring measurement quality is not possible without establishing a formal process for checking data quality. Similarly, how well data are displayed reflects whether the data have been transformed into information (van Lohuizen and Kochen 1986), and shows its relevance for management, monitoring or planning purposes. Feedback is an important process for identifying problems for resolution, for regulating and improving performance at individual and system levels, and for identifying opportunities for learning (Knight 1995; Rothwell et al. 1995). However, feedback remains a weak process of RHIS in many developing countries (Hozumi et al. 2002; Nsubuga et al. 2002; JICA HMIS Study Team 2004; Aqil et al. 2005a; Boone and Aqil 2008; Gnassou et al. 2008). Facility staff receive feedback from self-assessing their performance using their own records and reports, and from the district management. The same process could be repeated at district or higher administrative levels.

RHIS determinants

The PRISM framework moves beyond the relationship between RHIS processes and performance, and adds a new layer of individual and contextual determinants. These determinants are captured under three categories: behavioural, organizational and technical. To keep the PRISM framework parsimonious, we included those determinants that are empirically tested and amenable to change.

Behavioural determinants

RHIS users’ demand, confidence, motivation and competence to perform RHIS tasks affect RHIS processes and performance directly (Figure 3). How an individual feels about the utility or outcomes of a task (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Hackman and Oldham 1980), or his confidence in performing that task (Bandura 1977), as well as the complexity of the task (Buckland and Florian 1991), all affect the likelihood of that task being performed. Limited knowledge of the usefulness of RHIS data is found to be a major factor in low data quality and information use (Rotich et al. 2003; Kamadjeu et al. 2005; Odhiambo-Otieno 2005b). Motivating RHIS users remains a challenge despite training on data collection and data analysis. Negative attitudes such as ‘data collection is a useless activity or waste of care provider time’ hinder the performance of RHIS tasks (RHINO 2003). The PRISM framework postulates that if people understand the utility of RHIS tasks, feel confident and competent in performing the task, and perceive that the task's complexity is challenging but not overwhelming, then they will complete the task diligently. RHIS implies solving problems using information. However, problem-solving skill development (D’Zurrila 1986) was not a large part of RHIS capacity building in the past. We bring attention to this neglected area.

The blind spot (Luft 1969) shows that people are unaware of a gap between their perceived and actual competence in performing a task. It is possible to use this gap for learning to change and meet expected behaviours (Perloff 1993). The PRISM framework postulates that organizational and technical determinants also affect behavioural determinants (Figure 3).

Organizational determinants

RHIS users work in an organizational context, which influences them through organizational rules, values and practices (Figure 3). This organizational context is the health services system and can be managed by the public or the private sector. Organizational factors such as inadequacies in human and financial resources, low management support, lack of supervision and leadership affecting RHIS performance are described in the information system literature (Nsubuga et al. 2002; Rotich et al. 2003; Kamadjeu et al. 2005; Odhiambo-Otieno 2005b). The PRISM framework considers organizational determinants crucial for affecting performance and defines this category as all those factors that are related to organizational structure, resources, procedures, support services, and culture to develop, manage and improve RHIS processes and performance. The organizational factors affect RHIS performance directly or indirectly through behavioural factors (Figure 3).

Information systems promote evidence-based decision-making, manage knowledge and create transparency and good governance without changing the organizational hierarchy. Lippeveld et al. (1992) suggests that information systems need to follow the existing communications channels of organizational hierarchy. In socio-technical systems (Trist and Bamforth 1951), the emphasis is on measuring organizational processes of human and technology interaction that lead to quality services and products. Similarly, Berwick (1996) stated ‘Every system is designed to achieve exactly the results it achieves’, indicating that performance is a system characteristic. Thus, the PRISM framework emphasizes that all components of the system and its actors, leaders and workers, are responsible for improving RHIS performance. The leadership role is seen as a role model and facilitates work processes (Deming 1993; McLaughlin and Kaluzny 1994).

The regulation of organizational processes works better by means of collective values than by means of formal structure (Kahler and Rohde 1996). In other words, people do not always act on what they are told to do but act on sharing what is important and valued in an organization. Shared values related to information systems are alluded to as a pre-existing culture of data collection (Kamadjeu et al. 2005) or ‘culture of information’ (RHINO 2001; Hotchkiss et al. 2006) without specifying how these values originate and sustain themselves. Studies in organizational culture (Mead 1994; Triandis 1994) help us understand how values are generated, sustained and amenable to change. Shein (1991) notes that organizational culture is a body of solutions to problems that have worked consistently. They are taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems. Berry and Poortinga (1992) also showed the positive influence of values on organizational members’ behaviour. Therefore, understanding collective values related to RHIS processes and tasks could open up opportunities for promoting values conducive to RHIS tasks and lead to better performance.

The efficacy of organizational culture in improving performance is well established (Glaser et al. 1987; Conner and Clawson 2004; Cooke and Lafferty 2004; Taylor 2005). Similarly, we postulate that promoting a culture of information will improve RHIS performance. However, despite the use of the term ‘culture of information’ (RHINO 2001; Hotchkiss et al. 2006), there is no operational definition or measurement for a culture of information. The PRISM framework proposes an operational definition (Hozumi et al. 2002): ‘the capacity and control to promote values and beliefs among members of an organization by collecting, analyzing and using information to accomplish the organization's goals and mission’. To measure the culture of information, values related to organizational processes that emphasize data quality, use of RHIS information, evidence-based decision-making, problem solving, feedback from staff and community, a sense of responsibility, and empowerment and accountability were chosen, based on the proximity principle (Ajzen 2005). Demonstrating the existence of gaps in promoting a culture of information can be used to motivate senior management to renew their commitment to develop strategies for promoting an information culture and strengthening its linkage with RHIS performance (Figure 3).

RHIS management (Worthley and DiSalvio 1989; Odhiambo-Otieno 2005b) is crucial for RHIS performance (Figure 3). It is measured through availability of the RHIS vision statement and the establishment and maintenance of RHIS support services such as planning, training, supervision, human resources, logistics and finance. By identifying levels of support services, it is possible to develop priorities for actions.

Technical determinants

We defined technical determinants as all the factors that are related to the specialized know-how and technology to develop, manage and improve RHIS processes and performance. These factors refer to development of indicators; designing data collection forms and preparing procedural manuals; types of information technology; and software development for data processing and analysis (Figure 3). These factors also are described by others as potentially affecting RHIS performance (Nsubuga et al. 2002; Rotich et al. 2003; Mapatano and Piripiri 2005; Odhiambo-Otieno 2005b). Information technology will remain the engine for information system development as computers operate and communicate faster. Thus, it is necessary that RHIS users have good knowledge and information technology skills to effectively use and sustain it. However, in low technology settings, well-designed, paper-based RHIS can still achieve acceptable levels of performance.

If indicators are irrelevant, data collection forms are complex to fill, and if computer software is not user-friendly, it will affect the confidence level and motivation of RHIS implementers. When software does not process data properly and in a timely manner, and resulting analyses do not provide meaningful conclusions for decision-making, it will affect the use of information. Therefore, technical determinants (Figure 3) might affect performance directly or through behavioural factors.

RHIS and health system performance

Measuring the impact of RHIS on health system performance is an unexplored, but crucial frontier in terms of attracting more investment and countering criticism of RHIS's ability to improve health system performance. The difficulty with measurement arises from the lack of an operational definition for health system performance that could be used for testing RHIS's impact on health systems. We resolved this by defining health system performance restrictively and only keeping those health systems functions that are monitored through RHIS, such as health service delivery and resource management (financial, physical and human resources).

RHIS focuses mostly on the service delivery and resource management functions of the health system, and consequently affects those functions. Based on the proximity (Ajzen 2005) of RHIS and health system performance, we propose an operational definition of health system performance as ‘maintaining or improving service coverage and making necessary adjustments or improvements in financial and human resources in relation to services provided.’ We understand that this definition has limitations but it captures the major functions, which are common to various frameworks (Harrel and Baker 1994; Handler et al. 2001; HMN Secretariat 2006; Institute of Medicine 2006) for measuring health system performance and are incorporated into RHIS. Thus, the PRISM framework makes it possible to test the hypothesized relationship that an increased level of RHIS data quality and/or information use is associated with improved service coverage and associated resources.

PRISM tools

In order to measure RHIS performance, processes and determinants and their relationships described under the PRISM framework, four tools have been developed and standardized in Pakistan (Hozumi et al. 2002; JICA HMIS Study Team 2004), Uganda (Aqil 2004; Aqil et al. 2008) and further refined in China (Aqil et al. 2007a,b): (1) the RHIS performance diagnostic tool; (2) the RHIS overview tool; (3) the RHIS management assessment tool; and (4) the organizational and behavioural assessment tool. They use various means such as interviews, observations and pencil paper tests to collect data.

RHIS performance diagnostic tool

This tool determines the overall level of RHIS performance, looking separately at quality of data and use of information. The tool specifically measures: (a) RHIS performance; (b) status of RHIS processes; (c) the promotion of a culture of information; (d) supervision quality; and (e) technical determinants (Table 1). The tool collects data based on records observation, which is considered the gold standard and therefore confirms its validity.

Table 1.

Summary of information collected via the PRISM tools by unit of analysis

| Type of tool | Content | District or higher level | Facility- level |

|---|---|---|---|

| RHIS performance diagnostic tool | A. RHIS performance | ||

| • Data quality – completeness, timeliness, and accuracy | ✓ | ✓ | |

| • Information use – Report produced, discussion, decision, referral for action at higher level, advocacy | ✓ | ✓ | |

| B. Processes | |||

| – Collection, transmission, processing/analysis, display, data quality check, and feedback | ✓ | ✓ | |

| C. Promotion of culture of information | |||

| – Action plan, role modelling, newsletter, advocacy | ✓ | ✓ | |

| D. Supervision quality | |||

| – Frequency, discussion, checking quality, assist use for decision-making | ✓ | ||

| E. Technical determinants | |||

| – Complexity of forms, information technology, integration | ✓ | ||

| RHIS overview, office/facility | A. RHIS overview | ||

| checklist | • Mapping – list information systems, their overlap and distinctions | ✓ | |

| • Data collection and transmission – various forms and their user-friendliness | ✓ | ||

| • Information flow chart – communication pattern | ✓ | ||

| B. Office/facility checklist | |||

| – Availability of equipment, utilities, register/forms, data | ✓ | ✓ | |

| – Availability of human resources, % trained, types of training | ✓ | ✓ | |

| RHIS organizational and | A. Behavioural | ||

| behavioural assessment tool | – Self-efficacy (confidence) for RHIS tasks | ✓ | ✓ |

| (OBAT) | – RHIS tasks competence | ||

| – Motivation | |||

| – Knowledge of RHIS rationale, methods of checking data accuracy | ✓ | ✓ | |

| – Problem-solving skills | |||

| B. Promotion of a culture of information | |||

| – Emphasis on data quality | |||

| – Use of RHIS information | |||

| – Evidence-based decision-making | |||

| – Problem solving, feedback | |||

| – Sense of responsibility | |||

| – Empowerment/accountability | |||

| C. Reward | |||

| RHIS management assessment tool | RHIS management functions | ||

| (MAT) | – Governance, planning, training, supervision, quality, finance | ✓ | ✓ |

The tool provides opportunities to compare RHIS performance with status of RHIS processes and other determinants, as well as to identify strengths and gaps for appropriate actions/interventions.

RHIS overview tool

The mapping section of the RHIS overview provides information on all existing routine information systems, their interaction and overlaps. Thus, it identifies redundancies, workload, fragmentation and level of integration, which create demand for integrated information systems development. The review also provides information on the complexity and user-friendliness of the registers and forms. Lastly, an information flow chart provides information about horizontal and vertical transmission and decision-making nodal points (Table 1).

The office/facility checklist assesses resource availability at the facility and higher levels. The details of collected information are provided in Table 1. The tool collects data based on records observation and interviews. A comparison of resources availability (human, equipment, logistics) with RHIS performance provides information as to whether resources are appropriate and creating their intended effects. The level of integration of various information systems is highlighted.

RHIS management assessment tool (MAT)

This tool is designed to rapidly take stock of RHIS management practices. Since RHIS resource availability is assessed under the RHIS overview tool, it is not included under this tool. The practices measured relate to different functions such as: (a) governance; (b) planning; (c) training; (d) supervision; (e) use of performance improvement tools; and (f) finances (Table 1). The RHIS management assessment tool is part of the organizational determinants (Figure 3). The tool collects data based on records observations.

Besides providing information on the level of RHIS management functions, it indirectly shows senior management's commitment to an efficient and effective RHIS. It is unlikely that poor RHIS management practices will lead to better RHIS performance.

RHIS organizational and behavioural assessment tool (OBAT)

This tool identifies organizational and behavioural factors that affect RHIS performance (Figure 3, Table 1). It measures the level and role of behavioural factors such as motivation, confidence levels, demand for data, task competence and problem-solving skills, while organizational variables include promotion of a culture of information and rewards. The tool is self-administered and uses a paper and pencil test.

OBAT compares RHIS knowledge, skills and motivation with actual performance, and identifies the strengths and weaknesses of these behavioural factors. Similarly, it is possible to determine to what extent organizational factors influence performance directly or indirectly through behavioural factors (Figure 3).

Information obtained through the PRISM tools provides a comprehensive picture of the given RHIS, creating opportunities for intervention. However, if tools are used for monitoring or evaluation, other appropriate conclusions can be drawn. The PRISM tools and operations manual are available on the MEASURE Evaluation website. A computerized application for the tools is under development to facilitate data entry and analysis.

PRISM applications

The application of the PRISM framework and its tools in various countries has shown that they produce consistent and valid results. The diagnostic tools for measuring data quality and information use are based on the gold standard for records observation, which authenticate the results. In the PRISM tools validation study in Uganda (Aqil et al. 2008), the Chronbach alpha for the RHIS task confidence scale was 0.86 and 0.95 in 2004 and 2007, respectively, and the culture of information scale values were 0.87 and 0.85 for 2004 and 2007, respectively, which all show high reliability as well as the ability to maintain reliability over time. Similar results were obtained in the Yunnan and Guangxi provinces of China (Aqil et al. 2007a,b).

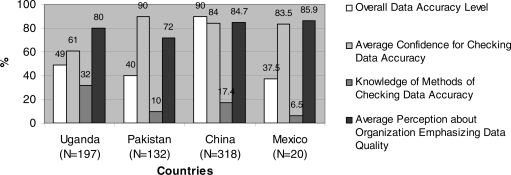

The PRISM framework states that in an efficient RHIS, different components should be working together harmoniously. For example, to achieve high quality data, it is assumed that staff should have a high level of confidence to conduct data accuracy checks, knowledge of different methods by which to check data accuracy, and support from an organizational culture that emphasizes high quality data. If there is a gap in any of these components, data quality would suffer. The application of PRISM tools in various countries confirmed this assumption. A comparative analysis of the means of these variables (Figure 4) describes whether various components of the information system are in line with each other in four countries. Figure 4 shows that the data accuracy was 49% in Uganda (Aqil et al. 2008), while the average perceived confidence level of the respondents to check data accuracy was 61%. This gives some idea why data accuracy is low. When data accuracy is compared with knowledge of methods of checking data (32% of respondents able to describe one or more methods of checking accuracy), the low accuracy level is further explained. In addition, a wider gap is found based on whether an organization is perceived to emphasize the need for high quality data or not. These gaps not only explain why data accuracy is low, but also indicate that respondents (organizational members) are unaware of these gaps in the existing information systems, creating an opportunity for interventions regarding better self-assessment, sense of responsibility, ownership and accountability.

Figure 4.

Comparisons among different variables related to data quality by countries

Despite diversity in geography and cultures, the results (Figure 4) were similar for Pakistan (JICA HMIS Study Team 2004) and Mexico (MEASURE Evaluation 2006), though not for China (Aqil et al. 2007a,b), indicating that the tools can accurately differentiate among situations in different countries. Three points need to be noted. First, China has a system of checking data accuracy at the provincial and national levels. The majority of the facilities have computers and data are directly entered into an online database, which is then checked at a higher level using historical trends. This explains why, despite low staff knowledge of methods of checking data accuracy, the data accuracy is high. However, there was recognition that this weakness is not good for catching mistakes and managing the system locally and thus needs to be rectified.

Second, in Mexico the study used lot quality assurance sampling, which is based on a small sample size. The results were comparable, indicating that it is not necessary to have large sample sizes to show gaps among different components of the system.

Third, comparative analyses among RHIS performance indicators and various components of the information system show existing strengths and gaps, provide a comprehensive picture of the information systems, and indicate opportunities for improvements. For example, the Uganda study (Aqil et al. 2008) showed that there is low information use (24%), which was consistent with the limited observed skills level to interpret (41%) and use information (44%). Otherwise, the study participants, managers and facility staff, showed a high subjective confidence level for these skills (56% and 58% for data interpretation and information use, respectively), as well as strong perceptions that the health department promotes the use of information (78%). These gaps between existing perceptions and observed skills and performance in interpreting data and information use opened a dialogue about what needs to be done to bridge these ‘perception’ gaps, and about distributing responsibilities rather than blaming each other. It consequently led to the development of interventions such as skills training, supportive supervision and feedback processes, and sharing success stories through existing communication channels to promote the use of information.

In Uganda, Pakistan, Haiti, Paraguay and Côte d’Ivoire (Aqil 2004; JICA HMIS Study Team 2006; Aqil et al. 2007a,b; Torres 2007; Boone and Aqil 2008; Gnassou et al. 2008), the PRISM assessment showed a limited availability of skilled human resources and of data collection forms, which are a constant cause of low performing RHIS. Thus, these studies do show that the PRISM framework identifies gaps in different components of the RHIS, which affects its ability to enhance performance.

The PRISM framework and tools have been used in Pakistan, Uganda, South Africa, Mexico, Honduras, Paraguay, Haiti and Côte d’Ivoire for assessing, reforming and strengthening RHIS (Hozumi et al. 2002; Aqil 2004; MEASURE Evaluation 2006; Torres 2007; Boone and Aqil 2008; Gnassou et al. 2008). In Uganda, a checklist was developed to assess the level of data quality and use of information (Aqil 2005), which was later adapted in Pakistan during the reform of its HMIS (JICA HMIS Study Team 2006). The pilot test evaluation of the new ‘District Health Information System’ (DHIS) in Pakistan showed that data quality and information use improved from 40% and 10% to 75% and 55%, respectively. Mexico's government created a website for interested districts, provinces and semi-government health institutions to conduct their organizational and behavioural skills assessment using OBAT (Ascencio and Block 2006). In China, as part of the intervention, a training manual was developed to improve skills in checking data quality, data analysis and interpretation, feedback, advocacy and use of information (Aqil and Lippeveld 2007). A monitoring checklist is used to assess progress towards targets. RHIS training courses based on the PRISM framework were developed and modified (Hozumi and Shield 2003; Aqil et al. 2005b) and training courses were conducted at Pretoria University in South Africa in 2005 and at the Institute of Public Health (INSP) in Mexico in 2006. The PRISM framework is taught at universities (Stoops 2005; Weiss 2006), while the Health Metrics Network (HMN Secretariat 2006) has subsumed the PRISM framework into its information systems framework.

Discussion

There is little doubt that, in developing countries, RHIS are failing to support the health system and to create transparency and accountability. The PRISM framework is an attempt to ameliorate this situation. However, there are other competing models of information systems development (ISD). Hirschheim and Klein (1989), based on various philosophical, epistemological and ontological assumptions, categorized ISD into four paradigms: functional, social relativist, radical structuralist and neohumanist.

The functional paradigm is based on a technical process, involving a dialogue between information system developers and managers to identify the information needs of health systems. The developer consequently designs the system in consultation with the managers who implement it. Social relativism emphasizes users or organizational members’ involvement as understanding that is created through social interaction. Thus, the developer's role is to facilitate a decision as to what type of information system makes sense to everyone in the organization for better understanding of the organizational objectives, and to promote shared values and expected behaviours around those objectives.

The radical structuralist paradigm is based on dialectics and assumes that the organization is divided into management and labour. The information system is developed to support management control; consequently the developer's role is partisan. Neohumanism is largely hypothetical and a reaction to the shortcomings of the other three paradigms. It assumes that humans seek knowledge for mutual understanding and emancipation and the existence of various interest groups. Thus, the developer's role is to create consensus among different stakeholders for the betterment of everyone.

The Hirschheim and Klein (1989) paradigm classification demystifies the underlying philosophical assumptions and the ISD developer's role, and describes the advantages and disadvantages of using a particular paradigm and its associated expectations.

Lind and Lind's dialectical approach for developing information systems focuses on the resolution of tensions between information users and the technology savvy developer, and improving collaboration and learning between them (Lind and Lind 2005). This is an important consideration, which reflects some practical issues of computer competence and associated decision-making in developing countries. However, to avoid falling into the ‘technical’ pit, the approach invokes a human activity system without elaborating what that is and how it affects the developer-user dialectical relationship, or vice versa. There is no discussion about how this interaction affects system performance. These weaknesses of approach limit broad application for information system design and maintenance.

The flexible standard strategy is another paradigm proposed for developing information systems in developing countries (Braa et al. 2007). It reinforces the idea of flexibility in information systems by introducing flexible standards and a flexible database to accommodate district or lower level information needs and support decentralization. These flexible standards could be in the areas of selected indicators or software technology. However, the strategy becomes confusing when it tries to explain its theoretical base. It assumes that the information system is a complex adaptive system without specifying macroscopic properties of the system or the emergence and criteria of meeting self-organization and adaptation (Holland 1998). The health information systems are subsystems and subservient to health systems in any country and do not have lives of their own. In addition, the authors’ claim of creating an attractor (standard) for the emergence of a new and better order is antithetical to a self-organizing system, which creates attractor(s) due to its internal dynamics.

The PRISM framework, grounded in empirical evidence, is robust in explaining the dynamics of the information system and its linkages with information system performance and health systems. Its application in diverse countries has proven its utility and effectiveness. However, the PRISM framework faces three major challenges.

First, the PRISM framework emphasizes an attitude of taking responsibility and avoiding blame. The framework promotes the idea that everyone is responsible for achieving RHIS objectives and performance, thus reducing the division of data collectors and data users. It promotes performance self-regulation by designing tools for measuring RHIS performance and determinants of performance. This shift in attitudes and practices poses a challenge to the RHIS status quo and in turn becomes a potential challenge for continued use of the PRISM framework.

Secondly, the PRISM framework application requires additional skills in performance improvement tools, communication and advocacy.

Lastly, the PRISM tools are very comprehensive and time consuming, which constrains their use. Yet, there is a misconception that all PRISM tools should be applied all the time to get an accurate snapshot of RHIS. Therefore, we promote using only those tools that are appropriate for a specific purpose. For example, mapping is only needed when the objective is to study the interaction and overlap of existing information systems or to strengthen integration of information for multiple services. Similarly, diagnostic tools could be applied not only for creating a baseline for RHIS performance but also for monitoring and evaluating it over a period of time. However, for studying the determinants of RHIS performance, OBAT, MAT and facility/office checklists are useful.

The PRISM framework, despite its challenges, asks information system practitioners to test their ‘perspectives’, to be open to exploring and incorporating information system best practices, and to contribute to developing a state of the art RHIS, thus improving overall health system performance.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Sian Curtis, Timothy Williams, and Karen Hardee for their comments on the draft manuscript and to Andrea Dickson for editing it.

This paper was made possible by the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement GPO–A–00–03–00003–00 (MEASURE Evaluation). The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID or the United States Government.

Endnotes

1 Routine Health Information Systems (RHIS) and Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) are considered synonyms both referring to any data collection conducted regularly with an interval of less than 1 year in health facilities and their extension in the community. For purposes of simplicity, the paper uses the term RHIS throughout.

References

- Ajzen I. Laws of human behavior: symmetry, compatibility, and attitude-behavior correspondence. In: Beauducel A, Biehl B, Bosniak M, et al., editors. Multivariate Research Strategies. Aachen: Shaker Verlag; 2005. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A. UPHOLD Project. Kampala: John Snow, Inc. (JSI); 2004. HMIS and EMIS situation analysis, Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A. 2005. A manual for strengthening HMIS: data quality and information use. Uganda Ministry of Health, Information Resource Centre; USAID, UPHOLD Project, AIM Project. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A, Orabaton N, Azim T, et al. Determinants of performance of routine health information system (RHIS): evidence from Uganda and Pakistan.. American Public Health Association conference; 10–14 December 2005; Philadelphia. 2005a. abstract #109550. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A, Hozumi D, Lippeveld T. PRISM tools. 2005b doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp010. MEASURE Evaluation, JSI. Available online at: http://www.measure.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Aqil A, Lippeveld T. 2007. Training manual on continuous improvement of HMIS performance: quality and information use; focus on HIV/AIDS services. MEASURE Evaluation, Guangxi and Yunnan CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A, Lippeveld T, Yokoyama R. Yunnan Baseline HMIS Report. 2007a. MEASURE Evaluation, CDC Yunnan, USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A, Lippeveld T, Yokoyama R. 2007b. Guangxi Baseline HMIS Report. MEASURE Evaluation, CDC Guangxi, USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Aqil A, Hotchkiss D, Lippeveld T, Mukooyo E, Asiimwe S. 2008. Do the PRISM framework tools produce consistent and valid results? A Uganda study. Working Paper. National Information Resource Center, Ministry of Health, Uganda; MEASURE Evaluation, 14 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ascencio RA, Block AM. 2006. Assessment of the National Health Information System of Mexico. Health System Information Center, National Institute of Public Health; General Bureau of Health Information, Secretariat of Health. Cooperative Agreement GPO-A-00–03–00003–00; U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); MEASURE Evaluation Project; Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Poortinga T. Cross-cultural psychology. New York: Cambridge Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. British Medical Journal. 1996;312:619–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone D, Aqil A. 2008. Haiti HSIS Evaluation Report. MEASURE Evaluation, Haiti Ministry of Health, USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Braa J, Hanseth O, Heywood A, Mohammad W, Shaw V. Developing health information systems in developing countries: the flexible standards strategy. MIS Quarterly. 2007;31:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland MK, Florian D. Expertise, task complexity and the role of intelligent information system. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 1991;42:635–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chae YM, Kim SI, Lee BH, Choi SH, Kim IS. Implementing health management information systems: measuring success in Korea's health centers. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 1994;9:341–8. doi: 10.1002/hpm.4740090406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchman CW. Design of inquiring systems: basic concepts of systems and organizations. New York: Basic Books; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg C, Axtell C, Damadarant L, et al. Information technology: a study of performance and the role of human and organizational factors. Ergonomics. 1997;40:851–71. [Google Scholar]

- Conner LM, Clawson GJ. Creating a learning culture: strategy, technology, and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke RA, Lafferty JC. Organizational Cultural inventory (OCI). Plymouth, MI: Human Synergistics/Center for Applied Research, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Corso LC, Wisner PJ. Using the essential services as a foundation for performance measurement and assessment of local public health systems. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2000;6:1–18. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200006050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurrila TJ. Problem-solving theory: a social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva AS, Laprega MR. Critical evaluation of the primary care information system (SIAB) and its implementation in Ribeiero Preto, Sau Paulo, Brazil. Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2005;21:1821–8. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000600031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deming WE. The new economics for industry, government, education. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. Criteria and standards of quality assessment and monitoring. Quality Review Bulletin. 1986;14:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitudes, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs WW. Software chronic crisis. Scientific American. 1994;271:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser SR, Zamanou S, Hacker K. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Associations, Montreal. 1987. Measuring and interpreting organizational culture. [Google Scholar]

- Gnassou L, Aqil A, Moussa T, Kofi D, Paul JKD. 2008. HMIS Evaluation Report. HIS Department, Ministry of Health, Cote d’Ivoire; MEASURE Evaluation, USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Grindle MS, Thomas JW. Public choices and policy change: the political economy of reform in developing countries. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Handler A, Issel M, Turnock B. Conceptual framework to measure performance of public health system. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1235–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell JA, Baker EL. The essential services of public health. Leadership Public Health. 1994;3:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Health Information System Program (HISP) TALI tool. 2005 Online at: http://www.HISP.org.

- Hirschheim R, Klein HK. Four paradigms of information systems development. Communication of the ACM. 1989;32:1199–216. [Google Scholar]

- HMN Secretariat. HMN framework and standards for country health information systems. 1st. Geneva: Health Metrics Network/World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holland JH. Emergence: From chaos to order. Redwood City, CA: Addison-Wesley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hotchkiss DR, Eisele TP, Djibuti M, Silvestre EA, Rukhadze N. Health system barriers to strengthening vaccine-preventable disease surveillance and response in the context of decentralization: evidence from Georgia. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi D, Shield K. 2003. Manual for use of information for district managers. MEASURE Evaluation, USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi D, Aqil A, Lippeveld T. 2002. Pakistan situation analysis. MEASURE Evaluation Project, USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM) Performance measurement: accelerating improvement. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- JICA HMIS Study Team. 2004. Assessment of health information systems in the health sector in Pakistan. Scientific System Consultants (Japan), Pakistan Ministry of Health, JICA. [Google Scholar]

- JICA HMIS Study Team. The study of improvement of management information systems in the health sector in Pakistan. 2006. National Action Plan. Scientific System Consultants (Japan), Pakistan Ministry of Health, JICA. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler H, Rohde M. Changing to stay itself. SIGOIS Bulletin. 1996;17:62–64. cited in Lemken B et al. 2000. Sustained knowledge management by organizational culture. Proceedings of the 33rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kamadjeu RM, Tapang EM, Moluh RN. Designing and implementing an electronic health record system in primary care practice in sub-Saharan Africa: a case study from Cameroon. Informatics in Primary Care. 2005;13:179–86. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v13i3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight S. NLP at work. Neuro linguistic programming: the difference that makes a difference in business. 2nd. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lafond A, Field R. 2003. The Prism: Introducing an analytical framework for understanding performance of routine health information system in developing (draft). RHINO 2nd International Workshop, South Africa, MEASURE Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Lind A, Lind B. Practice of information system development and use: a dialectical approach. System Research & Behavioral Science. 2005;22:453. [Google Scholar]

- Lippeveld T, Limprecht N, Gul Z. 1992. Assessment study of the Pakistan Health Management Information System. Government of Pakistan and USAID. [Google Scholar]

- Lippeveld T, Sauerborn R, Bodart C. Design and implementation of health information systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Locke EA, Shaw VN, Sarri LM, Latham GP. Goal setting and task performance: 1969–1980. In: Landy F, editor. Readings in industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago, Ill: Dorsey Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Luft J. Of human interaction. Palo Alto, CA: National Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Malmsjo A, Ovelius E. Factors that induce change in information systems. System Research and Behavioral Science. 2003;20:243–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mapatano MA, Piripiri L. Some common errors in health information system report (DR Congo) Santé Publique. 2005;17:551–8. doi: 10.3917/spub.054.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavimbe JC, Braa J, Bjune G. Assessing immunization data quality from routine reports in Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2005;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin CP, Kaluzny AD. Continuous quality improvement in health care: theory, implementation and applications. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mead R. International management: cross-cultural dimensions. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- MEASURE Evaluation. 2005/2006. Improving RHIS performance and information use for health system management. Training courses. Pretoria University, South Africa, 2005; Institute of Public health, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MEASURE Evaluation. 2006. A conference organized by MEASURE Evaluation, USAID, Pan American Health Organization, 27–28 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell E, Sullivan FA. A descriptive feast but an evaluative famine: systematic review of published articles on primary care computing during 1980–97. British Medical Journal. 2001;322:279–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukooyo E, Orobaton N, Lubaale Y, Nsabagasni X, Aqil A. Culture of information and health services, Uganda.. Global Health Council, 32nd Annual Conference; June 2005; Washington DC. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mutemwa RI. HMIS and decision-making in Zambia: re-thinking information solutions for district health management in decentralized health systems. Health Policy and Planning. 2006;21:40–52. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czj003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Information Resource Centre (NHIRC) Kampala: Ministry of Health, Uganda; 2005. HMIS Procedure Manual 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nsubuga P, Eseko N, Tadesse W, et al. Structure and performance of infectious disease surveillance and response, United Republic of Tanzania, 1998. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2002;80:196–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo-Otieno GW. Evaluation of existing district health management information systems a case study of the district health systems in Kenya. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2005a;74:733–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo-Otieno GW. Evaluation criteria for district health management information systems: lessons from the Ministry of Health, Kenya. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2005b;74:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff RM. The dynamics of persuasion. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- RHINO. 2001. The RHINO workshop on issues and innovation in routine health information in developing countries. 12–16 March 2001, MEASURE Evaluation, Potomac, USA. [Google Scholar]

- RHINO. 2003. Enhancing quality and use of routine health information at district level. Second international workshop, September–October, Eastern Cape, South Africa. MEASURE Evaluation. [Google Scholar]

- Rotich JK, Hannan TJ, Smith FE, et al. Installing and implementing a computer-based patient record system in sub-Saharan Africa: the Mosoriot Medical Record System. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2003;10:295–303. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell WJ, Sullivan R, Mclean GN. Practicing Organization Development: A guide for consultants. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sauerborn R. Using information to make decision. In: Lippeveld T, Sauerborn R, Bodart C, editors. Design and implementation of health information systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shein EH. What is culture. In: Frost PJ, Moore LF, Louis MR, et al., editors. Reframing organizational culture. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stoops N. Certificate in Health Information Systems. University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and HISP, South Africa; 2005. Using information for local management. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C. Walking the talk: building a culture for success. London: Random House; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi E, Facchini LA, Santos Mia MF. Health information technology in primary health care in developing countries: a literature review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:867–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres N. 2007. Applying PRISM Tools: Performance of the health care system management in Paraguay, Final Report. Contract Nr. GPO-A-00–03–00003–00, Paraguay. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Culture and social behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trist EL, Bamforth KW. Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting. Human Relations. 1951;4:3–38. [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten E, Baltussen R, Bijmakers L, Niessen L. Advancing the Mexico agenda for the health systems research- from clinical efficacy to population health. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2006;8:1145–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gigch JP. System design, modeling and metamodeling. New York: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lohuizen CW, Kochen M. Introduction: mapping knowledge in policy making. Knowledge. 1986;8:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B. Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD; 2006. Evaluation frameworks for health information systems. [Google Scholar]

- Worthley JA, DiSalvo PS. Managing computers in health care: a guide for professionals. 2nd. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]