The sequencing of β amyloid protein (Aβ) in 1984 led to the formulation of the “amyloid hypothesis” of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Glenner and Wong, 1984). The hypothesis proposed that accumulation of Aβ is responsible for AD-related pathology, including Aβ deposits, neurofibrillary tangles, and eventual neuronal cell death (Tanzi and Bertram, 2005). Within a few years, four groups cloned the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene from which Aβ is processed (Goldgaber et al., 1987; Kang et al., 1987; Robakis et al., 1987; Tanzi et al., 1987). Linkage analysis mapped the gene to chromosome 21, and mutations in APP were found that led to the inappropriate processing of APP into the Aβ1–42 peptide (Goate et al., 1991; Mullan et al., 1992) (for review, see Tanzi and Bertram, 2005). However, these mutations are responsible for only a small fraction of the early-onset familial AD, and the search began for other genes that might also influence the processing of Aβ. Several novel mutations were identified in the presenilins (Levy-Lahad et al., 1995; Rogaev et al., 1995; Sherrington et al., 1995), and apolipoprotein E4 was identified as a major risk factor for the most frequent form of AD (Strittmatter et al., 1993; Mahley et al., 2006).

Two models have emerged to explain the etiology of AD. The first model, mentioned above, proposes that fibrillary Aβ deposits are responsible for the eventual neuronal degeneration (Selkoe, 1991; Hardy and Higgins, 1992). A second more recent model suggests that soluble Aβ oligomers disrupt glutamatergic synaptic function, which in turn leads to the characteristic cognitive deficits (Lambert et al., 1998; Hsia et al., 1999; Klein et al., 2001; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002; Klein, 2002; Kamenetz et al., 2003; Walsh and Selkoe, 2004).

One difficulty with the original amyloid hypothesis is the fact that the temporal patterns of amyloid deposits do not correlate well with the cognitive deficits in affected patients (Katzman et al., 1988). In fact, the best correlations with cognitive deficits are the loss of synaptic structure and function (Terry et al., 1991). Synaptic plasticity [e.g., long-term potentiation (LTP)] is impaired before Aβ deposits are detected in mouse models of AD (Hsia et al., 1999; Larson et al., 1999). In addition, soluble Aβ oligomers selectively block LTP (Walsh et al., 2002) and acutely disrupt cognitive function after infusion into the CNS (Cleary et al., 2005; Lesne et al., 2006). They also bind with a punctate pattern to excitatory pyramidal neurons but not to GABAergic neurons (Lacor et al., 2004, 2007) and lead to synaptic loss (Hsieh et al., 2006; Shankar et al., 2007). Together, these results suggest that impairment in synaptic function is an early event in the pathogenesis of AD. Uncovering the mechanisms whereby Aβ oligomers induce synaptic deficits is still at an early stage, and currently there is no consensus on the precise molecular pathways involved. A number of intracellular signaling pathways have been implicated in Aβ-induced synaptic dysfunction, and different sources or assembly states of Aβ oligomers may have different effects on synaptic function. Moreover, the relative involvements of intracellular and extracellular Aβ oligomers remain to be defined.

Striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase and glutamate receptor trafficking

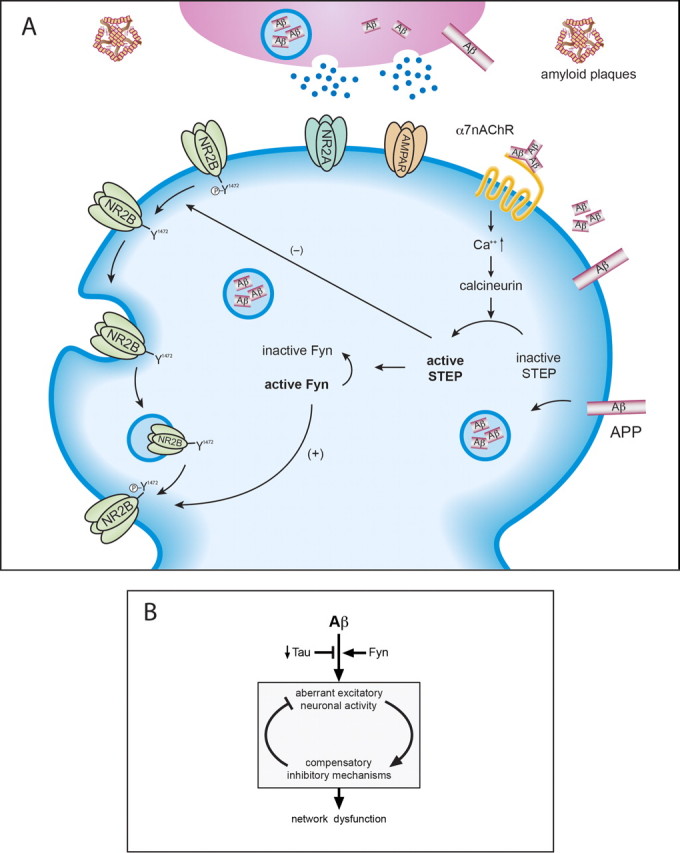

The role of Aβ in synaptic dysfunction was the subject of a mini-symposium at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. The first presentation by Deepa Venkitaramani discussed the role of striatal-enriched tyrosine phosphatase (STEP) in regulating glutamate receptor trafficking. STEP normally opposes the development of synaptic plasticity through its ability to dephosphorylate regulatory tyrosine residues on key signaling molecules (Lombroso et al., 1991, 1993) (Fig. 1). Thus, the dephosphorylation by STEP of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and Fyn leads to their inactivation, whereas dephosphorylation of the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor at Tyr1472 results in endocytosis of the receptor complex (Nguyen et al., 2002; Paul et al., 2003; Snyder et al., 2005). Aβ was recently shown to activate STEP, which in turn dephosphorylates NR2B (Snyder et al., 2005). Moreover, STEP also inactivates Fyn, a tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates NR2B at Tyr1472. Phosphorylation at that site promotes exocytosis of the NMDA receptor complex (Hallett et al., 2006). Thus, STEP decreases the surface expression of NMDA receptors through two mechanisms (Snyder et al., 2005; Braithwaite et al., 2006). These studies were done with synthetic or oligomeric Aβ secreted by cultured cells, and, currently, experiments are underway to determine whether purified higher-molecular-weight oligomers have varying synaptic effects (see below). Aβ was also shown to lead to the endocytosis of AMPA receptors (Almeida et al., 2005; Hsieh et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

A, Activation of STEP leads to NMDA receptor endocytosis. Aβ binding to the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor results in Ca2+ influx, calcineurin activation, and the dephosphorylation and activation of STEP. A trimer is shown binding to the receptor, although it is not clear which of the higher molecular weight oligomers is involved. STEP in turn dephosphorylates a regulatory tyrosine (Y1472) on the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor, as well as dephosphorylates and inactivates Fyn, the tyrosine kinase that phosphorylates NR2B-Y1472. STEP thus uses two distinct pathways to promote NMDA receptor internalization. B summarizes findings that suggest that a net increase in aberrant activity triggers compensatory inhibitory mechanisms to limit overexcitation but diminish the capacity for synaptic plasticity and lead to network dysfunction. This model proposes that Fyn kinase exacerbates, whereas tau reduction ameliorates, Aβ-induced aberrant neuronal activity. α7nAChR, α7-Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; AMPAR, AMPA receptor.

These results have led to the hypothesis that reducing STEP levels may increase glutamate receptors at surface membrane. Data were presented from STEP knock-out (KO) mice in support of this hypothesis, because basal phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2 and their downstream substrates are upregulated in the KO mice. Moreover, these mice have increased surface expression of glutamate receptors (both AMPA and NMDA). The results raise the intriguing possibility that reducing STEP levels may help alleviate some of the cognitive deficits caused by the synaptic actions of Aβ.

β Amyloid and Fyn in neuronal network dysfunction

Jeannie Chin then discussed the role of Fyn kinase and related pathways in sensitizing neurons to Aβ (Fig. 1B). Transgenic mice expressing moderate levels of human APP/Aβ (hAPP–J9) exhibit a relatively subtle AD-like phenotype. In contrast, overexpression of Fyn and Aβ in FYN/hAPP–J9 double-transgenic mice results in severe neuronal and cognitive impairments similar to those otherwise seen only in hAPP mice with much higher levels of Aβ production (hAPP–J20 mice) (Palop et al., 2003; Chin et al., 2004, 2005; Palop et al., 2005). In addition, ablation of Fyn prevents several aspects of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity (Lambert et al., 1998; Chin et al., 2004). These findings indicate that Aβ and Fyn may act synergistically in vivo.

Fyn increases NMDA receptor-mediated currents, modulates release of calcium from intracellular stores, and enhances synaptic transmission (Kojima et al., 1998; Lu et al., 1999; Cui et al., 2004; Salter and Kalia, 2004) and hence may cooperate with Aβ to sensitize neurons to overexcitation. Consistent with this hypothesis, recent studies from Lennart Mucke's laboratory demonstrated that both hAPP–J20 single transgenic mice and FYN/hAPP–J9 double transgenic mice exhibit spontaneous nonconvulsive seizure activity in cortical and hippocampal networks and increased seizure severity after inhibition of GABAA receptors (Palop et al., 2007). This increased seizure susceptibility is associated with prominent sprouting of inhibitory circuit elements and depletion of calcium- and activity-dependent proteins in the dentate gyrus (Palop et al., 2007). These cellular alterations may serve as compensatory inhibitory mechanisms against excitotoxicity (Vezzani et al., 1999; Palop et al., 2007). Notably, levels of active Fyn in the dentate gyrus are lower in hAPP–J20 mice than in controls. Moreover, levels of STEP, the phosphatase that inactivates Fyn, are strikingly increased, suggesting that suppression of Fyn activity may be a protective response in this brain region. Together, these studies suggest that Aβ and Fyn synergize to induce aberrant increases in neuronal activity, triggering inhibitory mechanisms that limit network overexcitation but that may also diminish the capacity for synaptic plasticity.

It is important to note that hAPP–J20 mice also have reduced levels of AMPA receptor subunits and LTP impairments in the dentate gyrus (Palop et al., 2007). Thus, aberrant increases in overall network activity coexist with impairments in glutamatergic transmission. The relationship between these two phenomena remains to be defined, but there are several possibilities that could help explain their coexistence. For example, depression of glutamatergic transmission could serve as a compensatory response or scaling mechanism triggered by overexcitation, or brain regions that control neuronal excitability on a global scale could be particularly susceptible to this Aβ-induced depression.

β Amyloid and Down syndrome

William Netzer next discussed the role of Aβ in Down syndrome (DS). DS is the most common, genetic form of mental retardation (Epstein, 1990) and is typically associated with AD pathology by the fourth decade (Schupf and Sergievsky, 2002). DS results from trisomy of chromosome 21, which involves triplication of >100 genes, including APP and other genes known to affect APP (Deutsch et al., 2003; Antonarakis et al., 2004). APP levels are elevated fourfold to fivefold compared with controls (Beyreuther et al., 1993). APP triplication predicts a 1.5-fold increase in APP levels and therefore does not explain the magnitude of this elevation. Additional factors may include triplication of the transcription factor ETS2, whereas other triplicated genes in DS, such as S100β and superoxide dismutase, have been implicated in amyloid deposition and metabolism, as has increased BACE1 (β-site APP-cleaving enzyme) maturation and activity (Griffin et al., 1998; Wolvetang et al., 2003; Lott et al., 2006).

Several mouse models of DS have been established. Of these, the Ts65Dn mouse is considered the gold standard because it displays many phenotypic aspects of human DS (Davisson et al., 1993). Ts65Dn is the result of a partial trisomy of mouse chromosome 16, containing all the genes within the human DS “critical region.” The mice display pronounced behavioral and cognitive deficits and disruption of hippocampal LTP (Escorihuela et al., 1995; Holtzman et al., 1996; Siarey et al., 1997; Kleschevnikov et al., 2004).

The Ts65Dn mouse also develops a cholinergic pathology at or slightly before 6 months of age (Holtzman et al., 1991; Hunter et al., 2003). However, because the behavioral and electrophysiological deficits in these mice are present at 2–4 months, the group addressed the possibility that elevated Aβ levels contribute to the human DS phenotype at all ages, and these were detected in Ts65Dn brains compared with littermate controls. Behavioral deficits (Morris water maze) were consistent with previous reports (Escorihuela et al., 1995), and preliminary data suggest that some of these deficits can be rescued by lowering Aβ levels.

Intraneuronal β amyloid in synaptic dysfunction

Gunnar Gouras then presented how intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ peptides contributes to functional alterations at synapses. Numerous laboratories have reported the intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ in transgenic mouse models of AD as well as human AD and DS (Gouras et al., 2005; LaFerla et al., 2007). Intraneuronal Aβ accumulation correlates with the onset of synaptic and behavioral abnormalities in transgenic models of AD (Oddo et al., 2003; Echeverria et al., 2004; Billings et al., 2005; Knobloch et al., 2007). Marked intraneuronal accumulation of Aβ was associated with early ultrastructural pathology, especially within distal processes and synaptic compartments (Takahashi et al., 2004).

Cultured neurons derived from AD transgenic mice provide a cellular model to study the cellular mechanism(s) whereby intraneuronal Aβ accumulation leads to synaptic abnormalities. Transgenic APP mutant compared with wild-type neurons develop progressive AD-like alterations in presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins, including early reductions in postsynaptic density-95 and glutamate receptors at synapses. These synaptic alterations can be prevented by reduction of Aβ by treatment with γ-secretase inhibitor or Aβ antibody (Almeida et al., 2005; Snyder et al., 2005; Tampellini et al., 2007). Evidence supports a dynamic relationship between the extracellular and intracellular pools of Aβ that remains poorly defined and may be critical in Aβ-induced synaptic dysfunction (Glabe, 2001; Oddo et al., 2006).

Role of β amyloid *56 in memory impairment

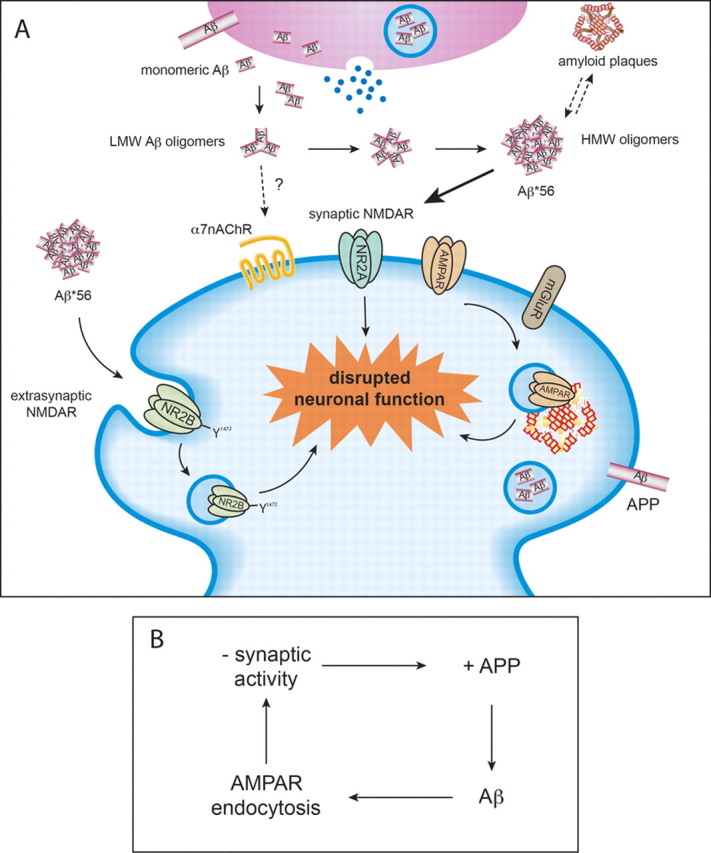

Sylvain Lesne next discussed the function of the soluble 56 kDa amyloid-β oligomer (Aβ*56) in the aging brain of Tg2576 mice (Fig. 2A). Although the effects of synthetic soluble Aβ oligomers and Aβ oligomers secreted by cultured cells include impairment of neuronal survival (Lambert et al., 1998; Kayed et al., 2003), inhibition of LTP (Walsh et al., 2002), disruption of behavior (Cleary et al., 2005), and endocytosis of NMDA receptors (Snyder et al., 2005), those of endogenous soluble Aβ assemblies have only recently been studied (Lesne et al., 2006). Data were presented showing correlations between Aβ*56 and spatial memory impairment at an age when there are no amyloid plaques, neuronal loss, or synaptic loss. The disruptive effects of Aβ*56 on cognitive function in healthy rats were also shown.

Figure 2.

A, Potential mechanism of action of Aβ*56 at neuronal surface. Monomeric forms of Aβ assemble into progressively larger oligomers, and these are detected in both intracellular endosomes and the extracellular space. One of the larger oligomers (Aβ*56) has been shown to disrupt learning in healthy rats. It is thought to disrupt synaptic NMDA and AMPA receptor trafficking. B, Recent work suggests that Aβ may act as part of a negative feedback signaling pathway. Enhanced synaptic activity leads to increased APP processing to Aβ, which leads to synaptic AMPA receptor endocytosis and reduced synaptic activity. LMW, Low molecular weight; HMW, high molecular weight; α7nAChR, α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; AMPAR, AMPA receptor; NMDAR, NMDA receptor; mGluR, metabotropic glutamate receptor.

Because glutamate receptors are critical elements in synaptic plasticity and memory, studies are underway to explore the possibility that Aβ*56 impairs memory by interacting directly with glutamate receptors. Preliminary data suggest that Aβ*56 coimmunoprecipitates with NR1 and NR2A subunits but not with AMPA receptor GluR1, GluR2 subunits, or the α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. These results raise the possibility that Aβ*56 could physically interact with NMDA receptors at plasma membranes to alter neuronal function well before neuronal death occurs and might interfere with memory function in the preclinical phases of AD.

The levels of Aβ-derived diffusible ligands (ADDLs) are significantly higher in the spinal fluid and brain tissue of Alzheimer's disease patients compared with control subjects (Gong et al., 2003; Georganopoulou et al., 2005). Studies of ADDLs in the prodromal phase of AD, also known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), have not been reported. In Tg2576 mice, ADDLs increase throughout life, in contrast to Aβ*56, whose levels remain stable. Therefore, Aβ*56 and ADDLs may represent different Aβ species. Experiments have begun to test the hypothesis that Aβ*56 levels increase before the diagnosis of AD by measuring Aβ*56 levels in brain tissue from the Religious Orders Study of individuals with MCI, as well as noncognitively impaired subjects and persons with probable AD. Initial results are encouraging, showing comparable elevations of Aβ*56 in MCI and probable AD compared with lower levels in unimpaired subjects.

β amyloid and neuronal activity

Roberto Malinow reviewed studies that have focused on two questions: (1) does neuronal activity modulate the formation of Aβ, and (2) does Aβ in turn modulate neuronal activity? His laboratory has shown that neuronal activity increases the formation of Aβ and that increased Aβ leads to depression of excitatory synaptic transmission (Kamenetz et al., 2003) (Fig. 2B). These two findings have led to the hypothesis that Aβ may normally serve as a negative feedback signal that maintains neuronal activity within a normal dynamic range: too much neuronal activity leads to formation of more Aβ, which depresses excitatory synapses and reduces neuronal activity. Recent in vivo studies on wild-type animals (Cirrito et al., 2005) and in vitro studies on wild-type (Ting et al., 2007) and knock-out (Priller et al., 2006) animals support this view.

More recently, the laboratory examined the mechanisms by which Aβ depresses excitatory synapses (Hsieh et al., 2006). Several parallels exist between long-term depression (LTD) and Aβ-induced synaptic changes. Aβ overexpression decreases spine density, partially occludes metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent LTD, decreases synaptic AMPA receptor number, and requires second-messenger pathways implicated in LTD for its depressive effects. Expression of an AMPA receptor mutant that prevents its LTD-driven endocytosis blocks the morphological and synaptic depression induced by Aβ. Furthermore, Aβ can drive phosphorylation of AMPA receptor at a site important for AMPA receptor endocytosis during LTD, and mimicking this AMPA receptor phosphorylation produces the morphological and synaptic depression induced by Aβ. Together, the results show that Aβ generates structural and synaptic abnormalities via endocytosis of AMPA receptors. Additional questions to be examined include whether the release of presynaptic or postsynaptic Aβ is responsible for the observed synaptic depression, whether there is a difference between acute and chronic exposure to elevated Aβ levels, and whether different Aβ oligomeric forms lead to different synaptic effects.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH52711, MH01527, NS33249, NS045677, NS041787, and AG022074.

References

- Almeida CG, Tampellini D, Takahashi RH, Greengard P, Lin MT, Snyder EM, Gouras GK. Beta-amyloid accumulation in APP mutant neurons reduces PSD-95 and GluR1 in synapses. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonarakis SE, Lyle R, Dermitzakis ET, Reymond A, Deutsch S. Chromosome 21 and down syndrome: from genomics to pathophysiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;10:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nrg1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyreuther K, Pollwein P, Multhaup G, Mönning U, König G, Dyrks T, Schubert W, Masters CL. Regulation and expression of the Alzheimers beta/A4 amyloid protein precursor in health, disease and Down's syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1993;695:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SP, Paul S, Nairn AC, Lombroso PJ. Synaptic plasticity: one STEP at a time. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:452–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Palop JJ, Yu G-Q, Kojima N, Masliah E, Mucke L. Fyn kinase modulates synaptotoxicity, but not aberrant sprouting, in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4692–4697. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0277-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin J, Palop JJ, Puoliväli J, Massaro C, Bien-Ly N, Gerstein H, Scearce-Levie K, Masliah E, Mucke L. Fyn kinase induces synaptic and cognitive impairments in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9694–9703. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2980-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirrito JR, Yamada KA, Finn MB, Sloviter RS, Bales KR, May PC, Schoepp DD, Paul SM, Mennerick S, Holtzman DM. Synaptic activity regulates interstitial fluid amyloid-beta levels in vivo. Neuron. 2005;48:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe K. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J, Matkovich SJ, deSouza N, Li S, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. Regulation of the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by phosphorylation at tyrosine 353. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16311–16316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davisson MT, Schmidt C, Reeves RH, Irving NG, Akeson EC, Harris BS, Bronson RT. Segmental trisomy as a mouse model for Down syndrome. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1993;384:117–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch SI, Rosse RB, Mastropaolo J, Chilton M. Progressive worsening of adaptive functions in Down syndrome may be mediated by the complexing of soluble Abeta peptides with the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: therapeutic implications. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2003;26:277–283. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria V, Ducatenzeiler A, Alhonen L, Janne J, Grant SM, Wandosell F, Muro A, Baralle F, Li H, Duff K, Szyf M, Cuello AC. Rat transgenic models with a phenotype of intracellular Abeta accumulation in hippocampus and cortex. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:209–219. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein CJ. The consequences of chromosome imbalance. Am J Med Genet Suppl. 1990;7:31–37. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320370706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escorihuela RM, Fernández-Teruel A, Vallina IF, Baamonde C, Lumbreras MA, Dierssen M, Tobeña A, Florez J. A behavioral assessment of Ts65Dn mice: a putative Down syndrome model. Neurosci Lett. 1995;199:143–146. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georganopoulou DG, Chang L, Nam JM, Thaxton CS, Mufson EJ, Klein WL, Mirkin CA. Nanoparticle-based detection in cerebral spinal fluid of a soluble pathogenic biomarker for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2273–2276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409336102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabe C. Intracellular mechanisms of amyloid accumulation and pathogenesis in Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17:137–145. doi: 10.1385/JMN:17:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease and Down's syndrome: sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goate A, Chartier-Harlin M-C, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, Giuffra L, Haynes A, Irving N, James L, Mant R, Newton P, Rooke K, Roques P, Talbot C, Pericak-Vance M, Roses A, Williamson R, Rossor M, Owen M, Hardy J. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1991;349:704–706. doi: 10.1038/349704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldgaber D, Lerman MI, McBride OW, Saffiotti U, Gajdusek DC. Characterization and chromosomal localization of a cDNA encoding brain amyloid of Alzheimer's disease. Science. 1987;235:877–880. doi: 10.1126/science.3810169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Chang L, Viola KL, Lacor PN, Lambert MP, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Alzheimer's disease-affected brain: presence of oligomeric A beta ligands (ADDLs) suggests a molecular basis for reversible memory loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10417–10422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras GK, Almeida CG, Takahashi RH. Intraneuronal Abeta accumulation and origin of plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, Sheng JG, McKenzie JE, Royston MC, Gentleman SM, Brumback RA, Cork LC, Del Bigio MR, Roberts GW, Mrak RE. Life-long overexpression of S100beta in Down's syndrome: implications for Alzheimer pathogenesis. Neurobiol Aging. 1998;19:401–405. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(98)00074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett PJ, Spoelgen R, Standaert DG, Dunah AW. Dopamine D1 activation potentiates striatal NMDA receptors by tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent subunit trafficking. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4690–4700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0792-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JA, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–356. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Li YW, Gage FH, DeArmond SJ, Epstein CJ, McKinley MP, Mobley WC. Modeling cholinergic abnormalities in Down syndrome and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1991;373:189–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman DM, Santucci D, Kilbridge J, Chua-Couzens J, Fontana DJ, Daniels SE, Johnson RM, Chen K, Sun Y, Carlson E, Alleva E, Epstein CJ, Mobley WC. Developmental abnormalities and age-related neurodegeneration in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13333–13338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsia AY, Masliah E, McConlogue L, Yu GQ, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA, Mucke L. Plaque-independent disruption of neural circuits in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3228–3233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Boehm J, Sato C, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron. 2006;52:831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter CL, Bimonte HA, Granholm AC. Behavioral comparison of 4 and 6 month-old Ts65Dn mice: age-related impairments in working and reference memory. Behav Brain Res. 2003;138:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Müller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Terry R, DeTeresa R, Brown T, Davies P, Fuld P, Renbing X, Peck A. Clinical, pathological, and neurochemical changes in dementia: a subgroup with preserved mental status and numerous neocortical plaques. Ann Neurol. 1988;23:138–144. doi: 10.1002/ana.410230206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease: globular oligomers (ADDLs) as new vaccine and drug targets. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:345–352. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein WL, Krafft GA, Finch CE. Targeting small Abeta oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer's disease conundrum? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleschevnikov AM, Belichenko PV, Villar AJ, Epstein CJ, Malenka RC, Mobley WC. Hippocampal long-term potentiation suppressed by increased inhibition in the Ts65Dn mouse, a genetic model of Down syndrome. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8153–8160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1766-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch M, Konietzko U, Krebs DC, Nitsch RM. Intracellular Abeta and cognitive deficits precede beta-amyloid deposition in transgenic arcAbeta mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1297–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima N, Ishibashi H, Obata K, Kandel ER. Higher seizure susceptibility and enhanced tyrosine phosphorylation on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit 2B in fyn transgenic mice. Learn Mem. 1998;5:429–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, Lambert MP, Velasco PT, Bigio EH, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer's-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10191–10200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3432-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Furlow PW, Clemente AS, Velasco PT, Wood M, Viola KL, Klein WL. Abeta oligomer-induced aberrations in synapse composition, shape, and density provide a molecular basis for loss of connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27:796–807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3501-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:499–509. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson J, Lynch G, Games D, Seubert P. Alterations in synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices from young and aged PDAPP mice. Brain Res. 1999;840:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01698-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesne S, Koh MT, Kotilinek L, Kayed R, Glabe CG, Yang A, Gallagher M, Ashe KH. A specific amyloid-β protein assembly in the brain impairs memory. Nature. 2006;440:352–357. doi: 10.1038/nature04533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Lahad E, Wasco W, Poorkaj P, Romano DM, Oshima J, Pettingell WH, Yu C, Jondro PD, Schmidt SD, Wang K, Crowley AC, Fu Y, Guenette SY, Galas D, Nemens E, Wijsman EM, Bird TD, Schellenberg GD, Tanzi RE. Candidate gene for the chromosome 1 familial Alzheimer's disease locus. Science. 1995;269:973–977. doi: 10.1126/science.7638622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombroso PJ, Murdoch G, Lerner M. Molecular characterization of a protein tyrosine phosphatase enriched in striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7242–7246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombroso PJ, Naegele JR, Sharma E, Lerner M. A protein tyrosine phosphatase expressed within dopaminoceptive neurons of the basal ganglia and related structures. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3064–3074. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-07-03064.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lott IT, Head E, Doran E, Busciglio J. Beta-amyloid, oxidative stress and down syndrome. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:521–528. doi: 10.2174/156720506779025305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YF, Kojima N, Tomizawa K, Moriwaki A, Matsushita M, Obata K, Matsui H. Enhanced synaptic transmission and reduced threshold for LTP induction in fyn-transgenic mice. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:75–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E4: A causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5644–5651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullan M, Crawford F, Axelman K, Houlden H, Lilius L, Winblad B, Lannfelt L. A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer's disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of beta-amyloid. Nat Genet. 1992;1:345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TH, Liu J, Lombroso PJ. Striatal enriched phosphatase 61 dephosphorylates Fyn at phosphotyrosine 420. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24274–24279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111683200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Smith IF, Green KN, LaFerla FM. A dynamic relationship between intracellular and extracellular pools of Abeta. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:184–194. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Jones B, Kekonius L, Chin J, Yu G-Q, Raber J, Masliah E, Mucke L. Neuronal depletion of calcium-dependent proteins in the dentate gyrus is tightly linked to Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9572–9577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Bien-Ly N, Massaro C, Yeung BZ, Yu G-Q, Mucke L. Vulnerability of dentate granule cells to disruption of Arc expression in human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9686–9693. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2829-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palop JJ, Chin J, Roberson ED, Wang J, Thwin MT, Bien-Ly N, Yoo J, Ho KO, Yu G-Q, Kreitzer A, Finkbeiner S, Noebels JL, Mucke L. Aberrant excitatory neuronal activity and compensatory remodeling of inhibitory hippocampal circuits in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2007;55:697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Nairn AC, Wang P, Lombroso PJ. NMDA-mediated activation of the tyrosine phosphatase STEP regulates the duration of ERK signaling. 2003;6:34–42. doi: 10.1038/nn989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priller C, Bauer T, Mitteregger G, Krebs B, Kretzschmar HA, Herms J. Synapse formation and function is modulated by the amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci. 2006;26:7212–7221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1450-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robakis N, Ramakrishna N, Wolfe G, Wisniewski H. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding the cerebrovascular and the neuritic plaque amyloid peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4190–4194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaev EI, Sherrington R, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Liang Y, Chi H, Lin C, Holman K, Tsuda K, Mar L, Sorbi S, Nacmias B, Piacentini S, Amaducci L, Chumakov I, Cohen D, Lannfelt L, Fraser PE, Rommens JM, St George-Hyslop PH. Familial Alzheimer's disease in kindreds with missense mutations in a gene on chromosome 1 related to the Alzheimer's disease type 3 gene. Nature. 1995;376:775–778. doi: 10.1038/376775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter MW, Kalia LV. Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1038/nrn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupf N, Sergievsky GH. Genetic and host factors for dementia in Down's syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:405–410. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Sabatini BL. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–2875. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington R, Rogaev E, Liang Y, Rogaeva Y, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, Tsuda T, Mar L, Foncin JF, Bruni AC, Montesi MP, Sorbi S, Rainero I, Pinessi L, Nee L, Chumakov I, et al. Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1995;375:754–760. doi: 10.1038/375754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siarey RJ, Stoll J, Rapoport SI, Galdzicki Z. Altered long-term potentiation in the young and old Ts65Dn mouse, a model for Down syndrome. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1549–1554. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EM, Nong Y, Almeida CG, Paul S, Moran T, Choi EY, Nairn AC, Salter MW, Lombroso PJ, Gouras GK, Greengard P. Regulation of NMDA receptor trafficking by amyloid-beta. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1051–1058. doi: 10.1038/nn1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter W, Saunders A, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen G, Roses A. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1977–1981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi RH, Almeida CG, Kearney PF, Yu F, Lin MT, Milner TA, Gouras GK. Oligomerization of Alzheimer's β-amyloid within processes and synapses of cultured neurons and brain. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3592–3599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5167-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tampellini D, Magrané J, Takahashi RH, Li F, Lin MT, Almeida CG, Gouras GK. Internalized antibodies to the Abeta domain of APP reduce neuronal Abeta and protect against synaptic alterations. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18895–18906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi RE, Bertram L. Twenty years of the Alzheimer's disease amyloid hypothesis: a genetic perspective. Cell. 2005;120:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi R, Gusella JF, Watkins PC, Bruns GA, St George-Hyslop P, Van Keuren ML, Patterson D, Pagan S, Kurnit DM, Neve RL. Amyloid beta protein gene: cDNA, mRNA distribution, and genetic linkage near the Alzheimer locus. Science. 1987;235:880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.2949367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry RD, Masliah E, Salmon DP, Butters N, DeTeresa R, Hill R, Hansen LA, Katzman R. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer's disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:572–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.410300410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting JT, Kelley BG, Lambert TJ, Cook DG, Sullivan JM. Amyloid precursor protein overexpression depresses excitatory transmission through both presynaptic and postsynaptic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:353–358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608807104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A, Sperk G, Colmers WF. Neuropeptide Y: Emerging evidence for a functional role in seizure modulation. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. Deciphering the molecular basis of memory failure in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2004;44:181–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolvetang EW, Bradfield OM, Tymms M, Zavarsek S, Hatzistavrou T, Kola I, Hertzog PJ. The chromosome 21 transcription factor ETS2 transactivates the beta-APP promoter: implications for Down syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1628:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(03)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]