SUMMARY

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is accompanied by dendritic spine growth and changes in the composition of the postsynaptic density (PSD). We find that activity-dependent growth of apical spines of CA1 pyramidal neurons is accompanied by destabilization of the PSD that results in transient loss and rapid replacement of PSD-95 and SHANK2. Signaling through PSD-95 is required for activity-dependent spine growth and trafficking of SHANK2. N-terminal PDZ and C-terminal guanylate kinase domains of PSD-95 are required for both processes, indicating that PSD-95 coordinates multiple signals to regulate morphological plasticity. Activity-dependent trafficking of PSD-95 is triggered by phosphorylation at serine 73, a conserved calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) consensus phosphorylation site, which negatively regulates spine growth and potentiation of synaptic currents. We propose that PSD-95 and CaMKII act at multiple steps during plasticity induction to initially trigger and later terminate spine growth by trafficking growth-promoting PSD proteins out of the active spine.

INTRODUCTION

In hippocampal pyramidal neurons, each spine contains the postsynaptic density (PSD) associated with a single excitatory synapse, and developmental changes in the number and properties of these synapses are typically associated with concomitant changes in spine number and morphology. On a population level, large spines house large PSDs that contain higher numbers of AMPA-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs) and support larger AMPAR-mediated currents (Harris and Stevens, 1989; Matsuzaki et al., 2001; Nakada et al., 2003; Nusser et al., 1998; Takumi et al., 1999). In addition, large spines are typically associated with high-release-probability presynaptic terminals that contain more active zone area (Harris and Stevens, 1989; Schikorski and Stevens, 1997; Ultanir et al., 2007). At the level of individual synapses, rapid changes in the number of synaptic AMPARs, such as following induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) or depression (LTD), are accompanied by increases or decreases, respectively, in the size of the associated spine (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2004). Moreover, for individual spines, the magnitude of spine head enlargement following LTP induction is directly correlated with the degree of potentiation of AMPAR-mediated synaptic currents (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004). How such correlations between structure and function are maintained and what molecular mechanisms underlie LTP-associated spine growth are largely unknown.

PSD-95/SAP90, a member of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) family, is highly abundant in the PSD and has been proposed to regulate many aspects of synaptic transmission (Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; El-Husseini et al., 2000a; Elias et al., 2006; Futai et al., 2007; Kim and Sheng, 2004; Schluter et al., 2006; Schnell et al., 2002; Stein et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2008). From biochemical and electrophysiological studies, it is clear that PSD-95-dependent protein complexes interact with both AMPARs and NMDA-type glutamate receptors (NMDARs) and that PSD-95 regulates NMDAR-dependent changes in AMPARs number such as those that underlie LTP and LTD. However, since the number of PSD-95 molecules in the PSD is ~10-fold larger than the number of synaptic glutamate receptors (Chen et al., 2005; Nimchinsky et al., 2004), it is likely that PSD-95 also regulates other aspects of synapse structure and function. Through its modular structure, PSD-95 is found in complexes with many proteins that affect spine structure, such as karilin-7, SPAR, SynGAP, SPIN90/WISH, and SHANK (Kim et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2006; Naisbitt et al., 1999; Pak et al., 2001; Penzes et al., 2001; Sala et al., 2001; Vazquez et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2007). PSD-95 is thus well positioned to link and coordinate multiple pathways regulating synapse structure and function, such as those that control activity-dependent spine growth and protein trafficking.

Here, we deliver LTP-inducing stimuli to individual apical dendritic spines of CA1 pyramidal neurons while monitoring spine morphology and trafficking of PSD proteins. We find that PSD-95 is necessary for the transient and sustained phases of activity-dependent spine growth. Furthermore, PSD-95 is rapidly trafficked out of dendritic spines in response to activity, in a manner that depends on calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases (CaMKs) and regulation of PSD-95 serine 73 (S73), a CAMKII phosphorylation site. Phosphorylation at this site inhibits both LTP and LTP-associated spine growth, indicating that CAMKII and PSD-95 likely act first to trigger and subsequently to terminate the growth process. In addition, PSD-95, in a guanylate kinase (GK) domain and S73-dependent manner, controls the activity-dependent trafficking of SHANK2, a growth-promoting molecule that links to the cytoskeleton. We propose that CaMKII and PSD-95 dynamically control the trafficking of PSD proteins to positively and negatively regulate the assembly of protein complexes necessary to promote and sustain structural and functional plasticity.

RESULTS

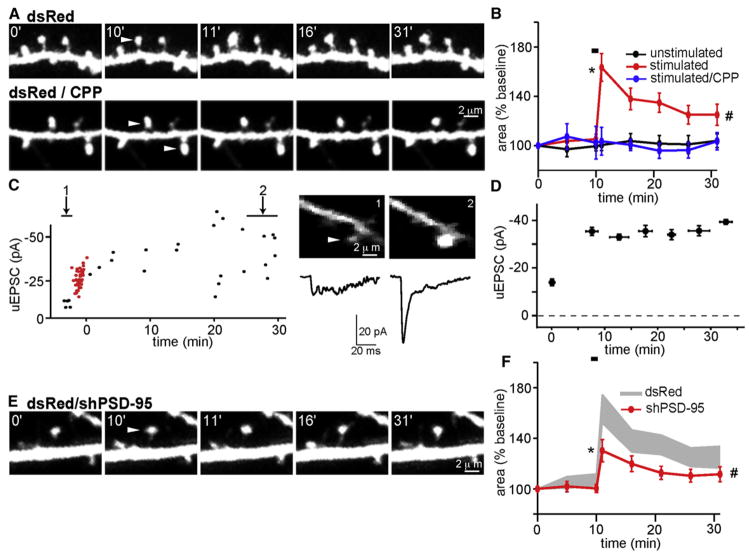

To visualize neuronal morphology, we expressed the red fluorescent protein dsRed in hippocampal neurons in rat organotypic slice cultures. Transfected CA1 pyramidal neurons were selected for analysis, and two-photon laser-scanning microscopy was used to identify spines from primary and secondary branches of apical dendrites (Figure 1). Morphological changes of individual spines were triggered by glutamate uncaging in Mg-free solution using a protocol that has been previously described to induce LTP and spine growth (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2008). Each spine was stimulated 40 times by two-photon laser uncaging (2PLU) of 4-methoxy-7-nitroindolinyl-glutamate (MNI-glutamate) at 0.667 Hz using 500 μs pulses of 720 nm light. This stimulation protocol, referred to below as the “plasticity-inducing stimulus” (PS), induces an increase in the size of the stimulated spine head (Figure 1A). Spine growth can be separated into an initial, rapid phase visible at the end of the 1 min PS and a smaller, persistent phase visible 20 min after stimulation and maintained for up to 3 hr (Figure S2 available online). Changes in spine size were quantified by measuring the apparent area (Figure 1B) and volume of the spine head as a function of time (Figure S1). For statistical analysis, we calculated the percentage enlargement immediately after (Δarearapid and Δvolrapid) and averaged 20–30 min after (Δareapersistent and Δvolpersistent) the PS.

Figure 1. PSD-95 Regulates Activity-Dependent Spine Growth.

(A) (Top) Example of a region of apical dendrite of a CA1 pyramidal neuron expressing dsRed that was imaged repetitively over 31 min. The acquisition times in minutes relative to the start of imaging are given. White arrowheads in this and all figures indicate the spines that were stimulated by 2PLU of MNI-glutamate and the time of plasticity-inducing stimulus (PS) onset. PS triggers an enlargement of the targeted spine. (Bottom) As above for neurons in the presence of 10 μM CPP, which blocks NMDARs and prevents activity-dependent spine growth.

(B) Time course of head cross-sectional area of stimulated spines (red, n = 22/4 spines/cells), unstimulated neighboring spines (black, n = 16/4 spines/cells), or spines stimulated in the presence of CPP (blue, n = 12/3 spines/cells). In all summary graphs, the black bar indicates the timing of the PS. * and # indicate statistical difference of p < 0.05 for the area of stimulated compared to unstimulated spines either 1 min (*) or averaged 20–30 min (#) after the stimulus.

(C) (Left) Example of LTP of uEPSCs evoked by PS delivered to a visualized spine of a voltage-clamped neuron filled with Alexa Fluor 594. The red points correspond to uEPSCs during the PS. (Right) Single optical slice showing the stimulated spine (top) and the uEPSC (bottom) before (1) and after (2) the PS.

(D) Time course of the changes in uEPSCs before and after the PS (n = 5/5 spines/cell).

(E) As in panel (A) for hippocampal neurons expressing dsRed and shPSD-95.

(F) Time course of spine head area of neurons expressing dsRed and shPSD-95 (red, n = 41/10 spines/cells). For comparison, data from panel (B) for dsRed-only expressing neurons are replotted (gray). In all plots of spine area, * and # indicate p < 0.05 compared to the data plotted in gray, respectively, at 1 min (*) or averaged 20–30 min (#) after PS.

Error bars depict the SEM.

In control cells, we observed statistically significant ~60% rapid (Δarearapid = 63% ± 11%; Δvolrapid = 62% ± 11%) and ~30% persistent (Δareapersistent = 28% ± 4%; Δvolpersistent = 29% ± 5%) increases in spine size, similar to what has been described previously (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). Nearby un-stimulated spines do not, on average, experience significant morphological changes (Δarearapid = 1% ± 4%, Δareapersistent = 2% ± 4%; Δvolrapid = −3% ± 3%, Δvolpersistent = −1% ± 2%; p < 0.05 for each versus stimulated spines), and spine growth in the stimulated spine is blocked by the NMDAR antagonist CPP (Δarearapid = 4% ± 6%; Δareapersistent = −2% ± 4%; Δvolrapid = 1% ± 3%; Δvolpersistent = 0% ± 3%; p < 0.05 for each versus control conditions) (Figures 1A, 1B, and S1) (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2008). For brevity, only changes in spine head area are reported in the text.

To confirm that PS induced LTP at the stimulated spine, we measured uncaging-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (uEPSCs) in whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings in Mg-free extracellular solution. Cells were loaded with the red fluorophore Alexa Fluor 594 through the pipette. Analysis of selected spines began within ~2 min, and PS was delivered within 5–10 min of rupture of the patch (Figure 1C). Stimulated spines displayed a persistent increase in uEPSC amplitude (−13.2 ± 2.8 and −34.8 ± 2.9 pA before and 20–30 min after PS, respectively; p < 0.05) (Figures 1C and 1D) (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004).

PSD-95 regulates synaptic AMPAR content and certain forms of synaptic plasticity (Beique and Andrade, 2003; Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; El-Husseini et al., 2000b; Migaud et al., 1998; Schnell et al., 2002; Stein et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2008). To investigate whether PSD-95 also regulates structural plasticity, neurons in which endogenous PSD-95 was knocked down by expressing a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against PSD-95 (shPSD-95) were examined (Schluter et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008). We found that knockdown of PSD-95 impaired early and late phases of spine growth (Δarearapid = 30% ± 9%, Δareapersistent = 16% ± 3%; p < 0.05 for each versus control stimulated spines) (Figures 1E and 1F), as suggested by analysis of chemically induced LTP (Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004). These effects were rescued by introduction of PSD-95 carrying silent mutations in the region targeted by shPSD-95, confirming that the effects were due to knockdown of PSD-95 (Figure S2). Since knockdown of PSD-95 has minimal effects on NMDAR-mediated EPSCs (Schluter et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008), these results suggest that PSD-95 acts downstream of NMDAR opening to promote activity-dependent spine growth.

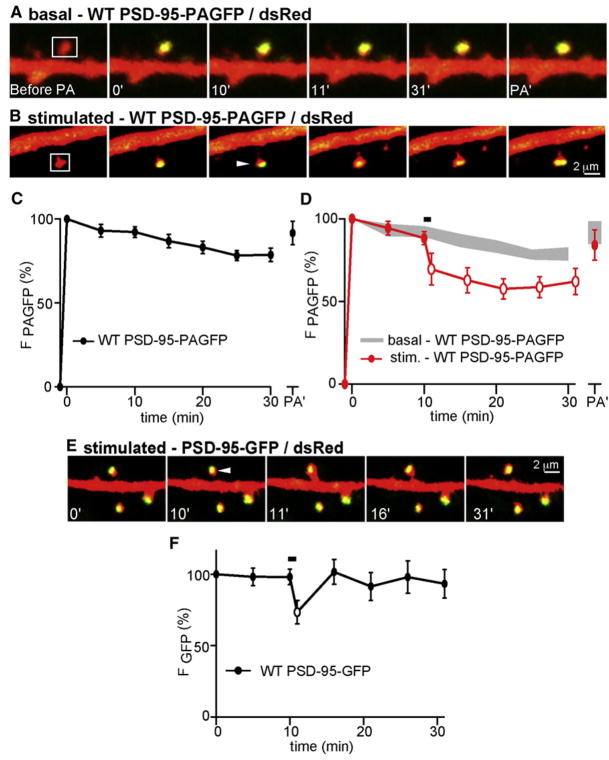

Transient Loss of PSD-95 during Activity-Dependent Spine Growth

Several forms of synaptic plasticity involve the insertion or removal of proteins from the PSD (Gray et al., 2006; Inoue et al., 2007; Kim and Sheng, 2004; Okabe et al., 1999; Sharma et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006; Tsuriel et al., 2006). Although PSD-95 can influence the levels of synaptic proteins such as AMPARs, whether its own trafficking is regulated by activity is unknown. To monitor the dynamics of PSD-95 during activity-dependent synaptic growth, we tagged PSD-95 with photoactivatable GFP (PAGFP) (Gray et al., 2006; Patterson and Lippincott-Schwartz, 2002; Xu et al., 2008) (Figure 2). In neurons expressing this construct and dsRed, minimal green fluorescence was detectable before photoactivation, consistent with the properties of PAGFP in its basal state (Figure 2A). Brief illumination at 730 nm photoactivated PAGFP and increased green fluorescence (Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2005; Gray et al., 2006). Since photoactivation of PAGFP reflects a covalent modification of the fluorophore, green fluorescence after photoactivation directly reports the distribution of tagged PSD-95 proteins that had been exposed to the photoactivating pulse. Green fluorescence within the spine head was expressed as a percentage of the fluorescence increase induced by the photoactivating pulse (FPAGFP) and reported as a function of time. Under our conditions, all of the PAGFP in the spine head is activated by the photoactivating pulse, and no significant photobleaching occurs during imaging (Figure S3).

Figure 2. PSD-95 Transiently Leaves the Spine Head during Activity-Dependent Growth.

(A) Images of spines from neurons expressing dsRed (red) and PSD-95-PAGFP (green). PSD-95-PAGFP in spines in the indicated areas (white boxes) was photoactivated at minute 0. Fluorescence intensity was monitored at the indicated times in minutes. At the end of the imaging period, the spines were exposed to a second photoactivating pulse (PA′).

(B) As in panel (A), with delivery of PS to the spine (arrowhead) at minute 10.

(C) Time course of PSD-95-PAGFP fluorescence in unstimulated spines following photoactivation (n = 45/9 spines/cells).

(D) Time course of PSD-95-PAGFP fluorescence in spines after photoactivation and stimulation with PS at minute 10 (red, n = 23/7 spines/cells). For comparison, the data from unstimulated spines are replotted (gray). Open symbols indicate statistical difference of p < 0.05 compared to the same time points for unstimulated spines.

(E) Images of a spine expressing dsRed (red) and WT PSD-95-GFP (green) that was stimulated by PS at 10 min.

(F) Time course of WT PSD-95-GFP fluorescence for spines stimulated with PS at 10 min (black, n = 11/3 spines/cells). The open symbol indicates statistical difference (p < 0.05) between the fluorescence at 11 min compared to 10 min.

Error bars depict the SEM.

The majority of the PSD-95 in the spine in the first image acquired after the photoactivating pulse remained in the head 30 min later, such that green fluorescence decreased ~15% during this time (Gray et al., 2006) (Figure 2A). Exchange of PAGFP-tagged proteins between this stable structure and an extra-spine pool of PSD-95-PAGFP was tested by delivery of a second photoactivating pulse after 30 min of imaging. This pulse produced an increase in green fluorescence that returned fluorescence to the levels seen after the first activation pulse (Figures 2A and 2C), indicating incorporation of unactivated PSD-95-PAGFP into the spine during the imaging period. Thus, a population of PSD-95 molecules is incorporated into a stable structure within the spine and is replaced at a basal rate of ~0.5%/min. To determine whether the rate of exchange of PSD-95 is regulated by activity, we examined the trafficking of PSD-95-PAGFP in spines stimulated with PS. Since PSD-95 overexpression increases spine size and occludes LTP (Ehrlich et al., 2007; Stein et al., 2003), we specifically selected spines from neurons expressing PSD-95 whose size was not different from neurons expressing dsRed alone (in microns, dsRed apparent spine width = 0.70 ± 0.02, length = 1.11 ± 0.05; WT PSD-95 width = 0.75 ± 0.03, length = 1.24 ± 0.07) (Figure S3A), corresponding to spine heads of ~0.1 fl in volume (Holtmaat et al., 2005; Sabatini and Svoboda, 2000). This class of spines in PSD-95-expressing cells exhibited normal activity-dependent spine growth (Δarearapid = 77% ± 15%, Δareapersistent = 27% ± 4%). Large spines of PSD-95-expressing neurons also demonstrated PS-induced spine growth (Figure S4), but will not be considered further here.

To image protein dynamics during spine growth, we used an 810 nm laser to photoactivate PSD-95-PAGFP without triggering spine growth (Figure S5). After 10 min of baseline imaging, the spine was stimulated with PS (Figure 2B). During spine growth (Δarearapid = 74% ± 20%, Δareapersistent = 20% ± 3%), the majority of activated PSD-95-PAGFP remained in a fixed location in the spine head, indicating that growth does not induce large-scale disassembly of the PSD. However, stimulated spines did undergo a rapid and persistent loss of ~30% of PSD-95-PAGFP fluorescence (Figures 2B and 2D). Delivery of a second photoactivating pulse restored green fluorescence to the level seen after the first photoactivating pulse, indicating that the stimulus-evoked loss of PAGFP fluorescence was due to replacement of photoactivated PSD-95-PAGFP by unactivated molecules not present in the spine at the start of the imaging session. Similar analysis in spines of neurons expressing dsRed and PSD-95-GFP revealed that induction of activity-dependent spine growth (Δarearapid = 75% ± 15%, Δareapersistent = 38% ± 8%) triggers a transient loss of PSD-95-GFP from the active spine but that baseline levels are restored within 5 min (Figures 2E and 2F). Thus, our results demonstrate that activity-dependent spine growth causes ~30% of the normally stable population of PSD-95 to translocate out of the spine and be rapidly replaced by PSD-95 molecules originally located outside of the spine.

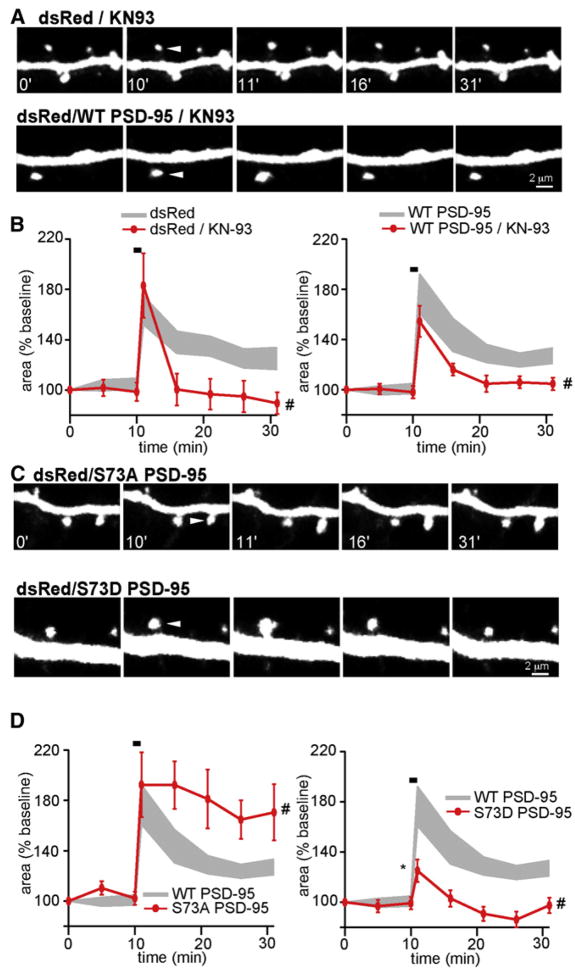

Regulation of PSD-95 Serine 73 Controls Activity-Dependent Spine Growth

Activity of CaMKs is required for the persistent phase of LTP-associated spine growth as demonstrated by its sensitivity to the CaMK inhibitor KN-62 (Matsuzaki et al., 2004). Similarly, we found that an inhibitor of CaMKs, KN-93, does not prevent the initial growth of spines of control (Δarearapid = 83% ± 26%) or WT PSD-95-expressing neurons (Δarearapid = 50% ± 15%) but prevents persistent growth in both (Δareapersistent = −3% ± 6% and 9% ± 5%, respectively) (Figures 3A and 3B). To examine whether direct regulation of PSD-95 by CaMKs controls activity-dependent spine growth and PSD-95 trafficking, we examined the effects of PSD-95 bearing mutations at serine 73 (S73). PSD-95 S73 is a CaMKII consensus phosphorylation site that a recent study demonstrated is directly phosphorylated by CaMKII and regulates the association of PSD-95 with NMDARs in hippocampal neurons (Gardoni et al., 2006). We generated constructs in which S73 was replaced by a nonphosphorylatable alanine (S73A PSD-95) or a phosphomimetic aspartate (S73D PSD-95) and examined their effects on activity-dependent spine growth.

Figure 3. CaMKII-Dependent Phosphorylation of PSD-95 Negatively Regulates Activity-Dependent Spine Growth.

(A) Images of stimulated dendritic spines from neurons pretreated with 10 μM of KN-93 and expressing dsRed alone (top) or dsRed and WT PSD-95 (bottom).

(B) Time course of head area (red) of stimulated spines from neurons expressing dsRed alone (left, n = 10/3 spines/cells) or dsRed and WT PSD-95 (right, n = 17/5 spines/cells) in the presence of KN-93. The gray area shows the data for spines in the absence of KN-93.

(C) Images of stimulated spines from neurons expressing dsRed and either S73A (top) or S73D (bottom) PSD-95.

(D)Time courses of head area (red) of stimulated spines from neurons expressing S73A (left, n = 20/7 spines/cells) or S73D (right, n = 21/7 spines/cells) PSD-95. For comparison, data from neurons expressing WT PSD-95 are replotted (gray).

Error bars depict the SEM.

Spines of neurons expressing S73A PSD-95 displayed normal initial growth that was indistinguishable from WT PSD-95 neurons (Δarearapid = 92% ± 26%) whereas the persistent phase was significantly enhanced (Δareapersistent = 72% ± 7%) (Figures 3C and 3D). Conversely, spines of neurons expressing S73D PSD-95 had significantly reduced rapid and persistent growth (Δarearapid = 15% ± 9%; Δareapersistent = −9% ± 4%). These results suggest that, although CaMK activity is necessary to induce persistent spine growth, phosphorylation specifically of PSD-95 at the CaMKII consensus site limits rather than enhances the extent of activity-dependent spine remodeling.

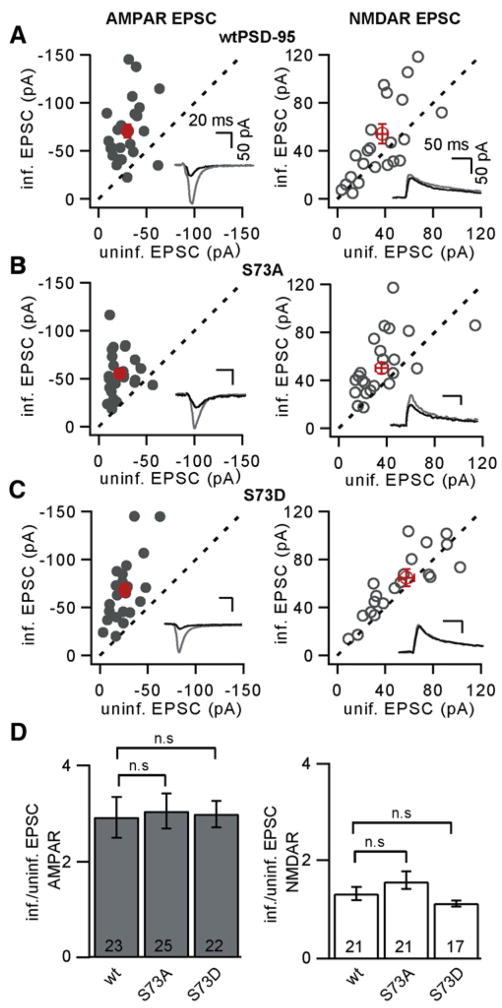

S73 PSD-95 Point Mutants Affect Basal Transmission to Similar Degree as WT PSD-95

Previous studies have shown that overexpression of PSD-95 increases and knockdown of PSD-95 by RNAi decreases AMPAR EPSCs in hippocampal neurons (Ehrlich et al., 2007; Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Schluter et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008). We investigated whether CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of PSD-95 at S73 is necessary for the effects of PSD-95 on basal synaptic expression of ionotropic glutamate receptors. In order to eliminate possible masking of the effects of S73 mutants on basal synaptic strength by endogenous WT PSD-95, we used a molecular replacement strategy for the analysis of basal synaptic transmission (Figure 4). In this approach, a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) directed against PSD-95 (shPSD-95) is used to knock down the expression of endogenous PSD-95, which is replaced by exogenous PSD-95 that is insensitive to shPSD-95 (Schluter et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008).

Figure 4. Regulation of PSD-95 Serine 73 Is Not Necessary for the Effects of PSD-95 on Synaptically Evoked AMPAR Currents.

(A) Amplitudes of AMPAR (left) and NMDAR (right) EPSCs of neurons transduced with a lentivirus encoding shPSD95 and WT PSD-95-GFP plotted against those recorded simultaneously in uninfected neighboring neurons. Each symbol represents the results of a single experiment, with the exception of red symbols, which show the mean ± SEM across experiments. The insets show example average traces from infected (gray) and uninfected (black) neurons from a single experiment.

(B and C) As in (A) for neurons transduced with shPSD95 S73A PSD-95 or shPSD95 S73D PSD-95, respectively.

(D) Summary of AMPAR and NMDAR EPSC amplitudes in neurons expressing shPSD95 PSD-95-GFP, shPSD95 S73A PSD-95-GFP, or shPSD95 S73D PSD-95-GFP expressed as a ratio to those in neighboring uninfected neurons (n.s. indicates p > 0.05).

Error bars depict the SEM.

Consistent with previous studies, expression of WT PSD-95 in combination with knockdown of endogenous PSD-95 increases AMPAR EPSCs compared to control neurons and has minimal effects on NMDAR EPSCs (Figure 4A) (Schluter et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008). Expression of S73A or S73D PSD-95 (Figures 4B–4D) also increased AMPAR EPSCs and had minimal effects on NMDAR EPSCs, such that their effects were indistinguishable from those of WT PSD-95 (Table S1). Thus, the phosphorylation state of PSD-95 by CaMKII at S73 does not affect basal AMPAR and NMDAR delivery into the synapse. Moreover, since both mutants of PSD-95 S73 have the same effects as WT PSD-95 on synaptic currents, the effects of these mutants on activity-dependent spine growth do not result from perturbations of basal synaptic glutamate receptor expression.

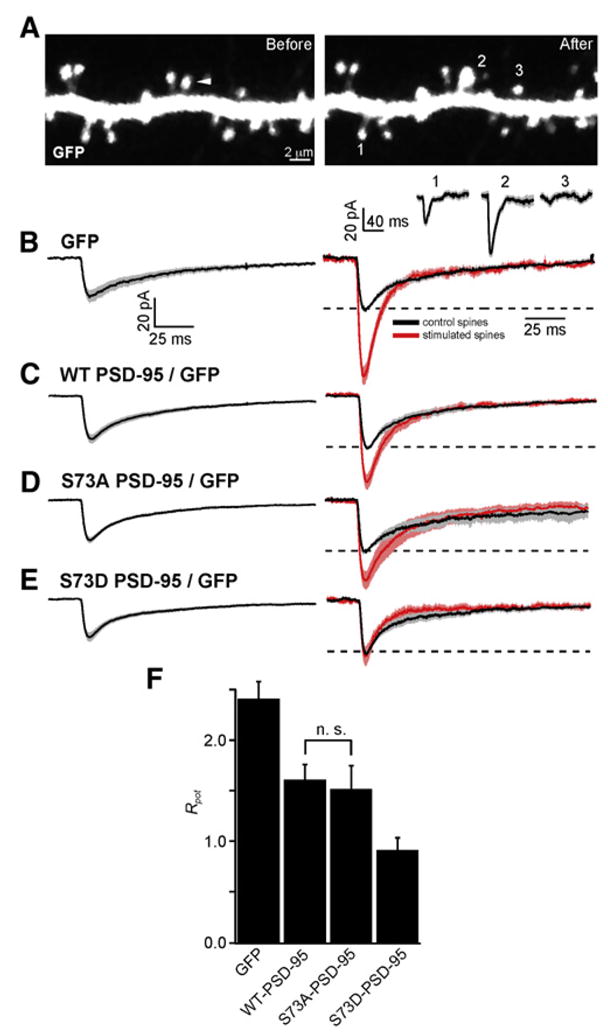

Expression of S73D PSD-95 Prevents LTP Expression

To examine whether modulation of PSD-95 S73 regulates activity-dependent potentiation of synaptic currents, we established a protocol in which the induction and initial expression of LTP could proceed under the same conditions used to monitor activity-dependent spine growth (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Apical spines of GFP-transfected CA1 pyramidal neurons were stimulated with PS as above (Figure 5). Twenty minutes later, a whole-cell voltage-clamp recording was obtained from the neuron, and the amplitude of the uEPSC at the spine that had received the PS was measured (uEPSCPS). In addition, the amplitudes of uEPSCs from multiple neighboring unstimulated spines were measured (uEPSCcontrol) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. LTP Requires Regulation of PSD-95 at Serine 73.

(A) Representative images before (left) and 1 min after (right) delivery of PS. The white arrowhead indicates the spine that was stimulated. Below the right panel are shown uEPSCs recorded ~20 min after PS from control spines (1 and 3) and from the stimulated spine (2). The line and shaded regions show the mean and mean ± SEM uEPSC for each spine.

(B) (Left) uEPSCcontrol measured in neurons expressing GFP (n = 65/15 spines/cells). (Right) Normalized uEPSCs measured from control (black) and stimulated (red, n = 15/15 spines/cells) spines from GFP-expressing neurons. The dashed line depicts the normalized amplitude of one of the control uEPSC.

(C–E) As in panel (B) for neurons expressing GFP and either WT PSD-95 ([C], control n = 69/11, stimulated n = 11/11 spines/cells), S73A PSD-95 ([D], control n = 58/11, stimulated n = 11/11 spines/cells), or S73D PSD-95 ([E], control n = 58/12, stimulated n = 12/12 spines/cells).

(F) Ratio of potentiation (Rpot) of the uEPSC at the stimulated spine compared to unstimulated neighboring spines in neurons expressing GFP alone or GFP and either WT PSD-95, S73A PSD-95, or S73D PSD-95. All differences across conditions with the exception of WT PSD-95 versus S73A PSD-95 are significant.

Error bars depict the SEM.

In GFP-expressing neurons, uEPSCcontrol (−25.0 ± 3.7 pA) (Figure 5B) was significantly smaller than uEPSCPS (−51.3 ± 12.7 pA), consistent with expression of LTP in the PS-stimulated spine. To quantify the degree of potentiation of the PS-stimulated spine in each cell, we defined a potentiation ratio, Rpot, as the uEPSCPS amplitude divided by the mean uEPSCcontrol amplitude measured in the cell. In GFP-expressing neurons, Rpot = 2.41 (confidence interval 2.24–2.59), indicating on average a greater than 2-fold increase in the uEPSC in the PS-stimulated spine. Similar analysis in normal-sized spines of WT PSD-95-expressing neurons revealed that the amplitude of uEPSCcontrol (−28.3 ± 2.8 pA) was indistinguishable from that of GFP-expressing neurons (Figure 5C). Furthermore, WT PSD-95-expressing neurons demonstrated LTP as evidenced by the significantly increased uEPSCPS (−51.2 ± 14.4 pA) compared to uEPSCcontrol with Rpot = 1.61 (1.46–1.77). Thus, moderate-sized spines of neurons overexpressing PSD-95 are capable of supporting LTP, albeit of a smaller amplitude than similar spines of control neurons.

Similar analysis revealed that uEPSCcontrol in neurons expressing S73A (−26.1 ± 1.8 pA) and S73D (−24.6 ± 2.9 pA) PSD-95 were indistinguishable from those in GFP control neurons and WT PSD-95-expressing neurons, consistent with S73 not regulating basal synaptic transmission (Figures 5D and 5E). However, whereas uEPSCPS (−39.6 ± 6.8 pA) was significantly larger than uEPSCcontrol in S73A PSD-95-expressing neurons, it was indistinguishable from uEPSCcontrol in S73D PSD-95-expressing neurons (−24.5 ± 6.0 pA), indicating that expression of S73D PSD-95 prevents LTP. Similarly, Rpot = 1.52 (1.29–1.79) in S73A and 0.91 (0.79–1.05) in S73D PSD-95-expressing neurons, confirming the block of LTP by S73D PSD-95. With the exception of the WT PSD-95 versus S73A PSD-95 comparison, all pairwise differences in Rpot across conditions are significant by ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple pairwise comparisons (Figure 5F). Thus, our analyses of basal synaptic transmission by electrical stimulation and of basal synaptic strength and LTP by glutamate uncaging indicate that the regulation of PSD-95 S73 does not control basal expression of synaptic glutamate receptors but that the presence of a phosphomimetic residue at S73 prevents the expression of LTP.

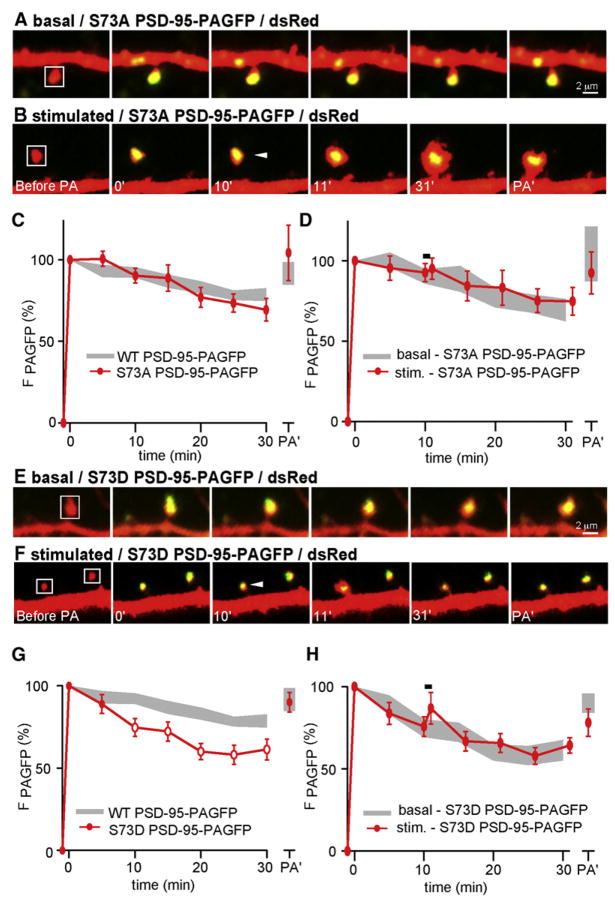

S73 Regulates Basal and Activity-Dependent Trafficking of PSD-95

We hypothesized that phosphorylation at PSD-95 S73 may destabilize a growth and plasticity promoting complex in the active spine. The expression of a phosphomimetic residue may prevent the stable formation of such a complex and thus prevent both LTP and LTP-associated spine growth. To examine this hypothesis, we examined the CAMKII and activity dependence of PSD-95 trafficking. We found that KN-93 has no effect on basal PSD-95 stability in the spine but, in addition to preventing PS-induced persistent spine growth (Figure 3), inhibits activity-dependent trafficking of PSD-95 (Figure S6). Since transient spine growth proceeds normally in the presence of KN-93, this indicates that PSD-95 trafficking is neither triggered by nor necessary for transient spine growth.

To more specifically examine the role of regulation at S73 in PSD-95 trafficking, we tagged S73A PSD-95 and S73D PSD-95 with PAGFP and examined their exchange out of spines in basal conditions and in response to PS (Figure 6). S73A PSD-95-PAGFP displayed normal stability in the basal state that was not different from that of WT PSD-95-PAGFP. However, PS failed to trigger the translocation of S73A PSD-95-PAGFP out of the spine despite robust growth (Δarearapid = 93% ± 31%, Δareapersistent = 64% ± 14%) (Figures 6A–6D). In contrast, in S73D PSD-95-PAGFP-expressing cells, which showed no activity-dependent spine growth (Δarearapid = 16% ± 9%, Δareapersistent = −8% ± 4%), the stability of S73D PSD-95-PAGFP was reduced compared to WT PSD-95-PAGFP in basal conditions and was not further destabilized by the PS (Figures 6E–6H). Thus, phosphorylation of S73, which inhibits persistent spine growth, is necessary for and enhances activity-dependent trafficking of PSD-95. Nevertheless, CAMK activity is also necessary to stabilize spine growth, as this process is inhibited by KN-93 in S73A PSD-95-PAGFP-expressing neurons (Figure S7).

Figure 6. Regulation at S73 Controls Basal and Activity-Dependent Trafficking of PSD-95.

(A) Images of spines from neurons expressing dsRed and S73A PSD-95-PAGFP. PAGFP in a spine was photoactivated (white box, 0 min), and subsequent changes in fluorescence intensity were monitored. The same spine was subjected to a second photoactivation pulse (PA′) at the end of the imaging period.

(B) As in panel (A) except that the spine received a PS between minutes 10 and 11 (white arrow).

(C) Average time course of S73A PSD-95-PAGFP fluorescence in spines after photoactivation (red, n = 35/14 spines/cells). For comparison, the time course of fluorescence in spines of WT PSD-95 transfected neurons is replotted in gray. (D) As in panel (C) for spines stimulated with PS at minute 10 (red, n = 14/5 spines/cells). The gray region shows the behavior of S73A PSD-95-PAGFP in unstimulated spines replotted from panel (C).

(E and F) As in panels (A) and (B) for neurons expressing S73D PSD-95-PAGFP in basal conditions or receiving PS at minute 10, respectively.

(G) As in panel (C) for neurons expressing S73D PSD-95-PAGFP (red, n = 35/9 spines/cells). Open markers indicate p < 0.05 compared to the time course of WT PSD-95-PAGFP fluorescence (gray).

(H) As in panel (D) for neurons expressing S73D PSD-95-PAGFP (red, n = 23/8 spines/cells). The gray region depicts the behavior of S73D PSD-95-PAGFP in unstimulated spines from panel (G).

Error bars depict the SEM.

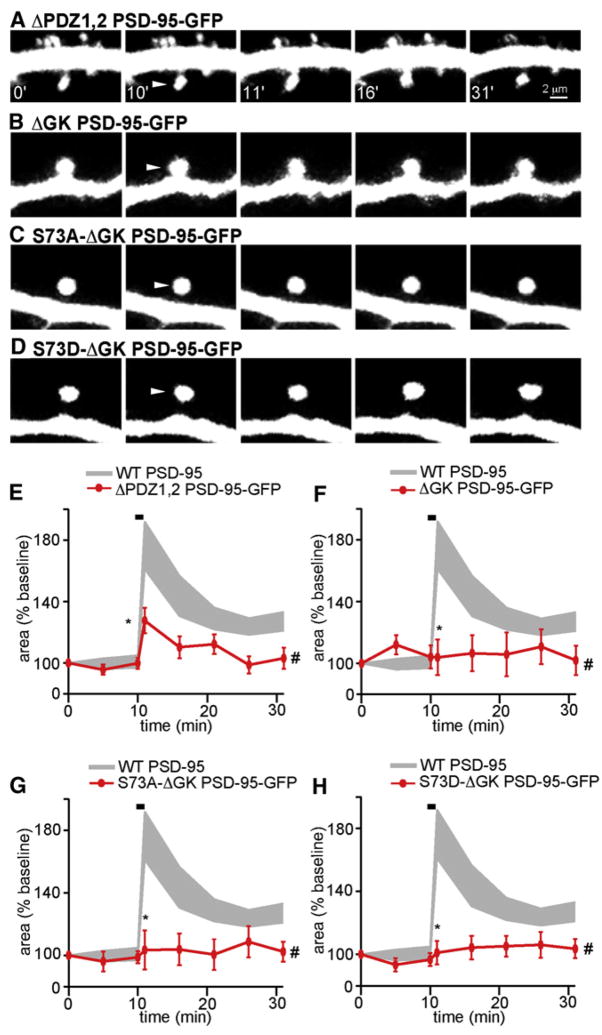

Multiple Domains of PSD-95 Are Necessary for Activity-Dependent Spine Growth

PSD-95 is a multifunctional molecule that interacts with cytoskeletal regulators through both its N-terminal PDZ domains and C-terminal SH3 and GK domains (Kim and Sheng, 2004). Previous studies have shown that, in contrast to expression of WT PSD-95, expression of PSD-95 lacking the first two PDZ domains (ΔPDZ1, 2 PSD-95) does not enhance AMPAR-mediated EPSCs (Schnell et al., 2002). Conversely, expression of PSD-95 lacking the third PDZ, SH, and GK domains enhances AMPAR-mediated EPSCs as efficiently as WT PSD-95 when expressed in the presence of endogenous PSD-95 (Schnell et al., 2002) but not when expressed in its absence (Xu et al., 2008). We find that expression of a mutant lacking the first two PDZ domains (ΔPDZ1, 2) reduces the early phase of activity-dependent spine growth and eliminates the late phase (Δarearapid = 28% ± 9%, Δareapersistent = 7% ± 4%) (Figures 7A and 7B), whereas a mutant lacking the GK domain (ΔGK) completely blocks both phases (Δarearapid = 4% ± 12%, Δareapersistent = 7% ± 7%) (Figures 7B and 7F). Furthermore, deletion of the GK domain abolishes growth irrespective of the state of S73 (S73A-ΔGK: Δarearapid = 3% ± 12%, Δareapersistent = 3% ± 7%; S73D-ΔGK: Δarearapid = 1% ± 8%, Δareapersistent = 4% ± 4%) (Figures 7C, 7D, 7G, and 7H). Thus, the first two PDZ domains and the GK domain are necessary for transient and persistent activity-dependent spine growth, and ΔGK PSD-95 suppresses the growth-promoting phenotype of S73A mutants.

Figure 7. N- and C-Terminal Interactions of PSD-95 Are Necessary for Activity-Dependent Spine Growth.

(A) Representative images of spines from neurons expressing dsRed and ΔPDZ1, 2 PSD-95-GFP. The indicated spines were stimulated with PS between minutes 10 and 11.

(B–D) As in panel (A) for neurons expressing dsRed and ΔGK PSD-95-GFP (B), S73A-ΔGK PSD-95-GFP (C), or S73D-ΔGK PSD-95-GFP (D).

(E) Average time course of head area of stimulated spines from neurons expressing dsRed and ΔPDZ1, 2 PSD-95-GFP (red, n = 38/11 spines/cells). Data from stimulated spines overexpressing WT PSD-95 are shown in gray.

(F–H) As in panel (E) for neurons expressing dsRed and either ΔGK PSD-95-GFP ([F], n = 10/3 spines/cells), S73A-ΔGK PSD-95-GFP ([G], n = 17/5 spines/cells), or S73D-ΔGK PSD-95-GFP ([H], n = 13/4 spines/cells).

Error bars depict the SEM.

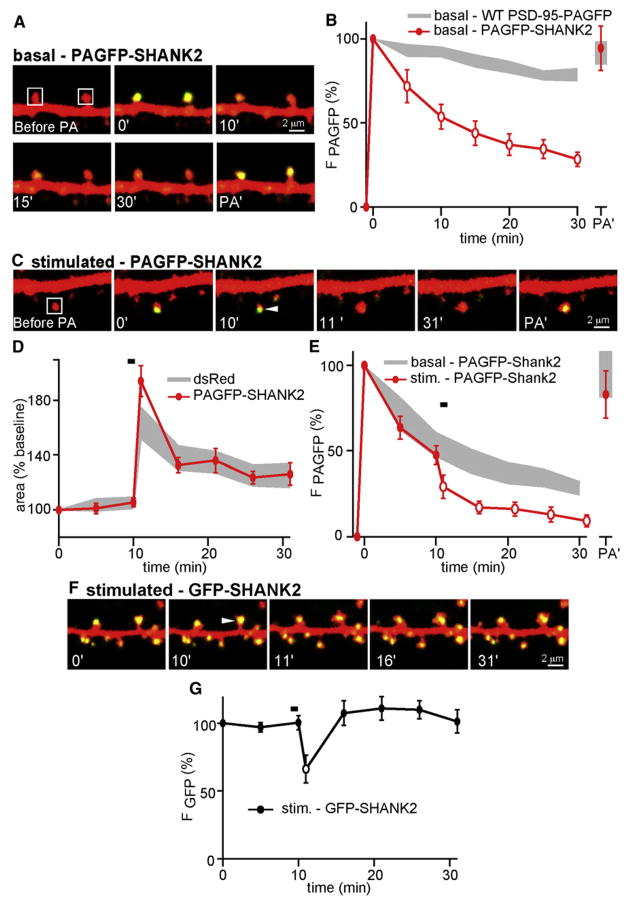

SHANK2 Rapidly Translocates from the Spines during Activity-Dependent Spine Growth

The GK domain of PSD-95 interacts with GKAP/SAPAP, which in turn binds members of the SHANK/ProSAP protein family (Boeckers, 2006; Boeckers et al., 1999; Naisbitt et al., 1999; Sheng and Kim, 2000). SHANK proteins are major constituents of the PSD and are postulated to promote morphological maturation and enlargement of spines (Sala et al., 2001). We examined whether a conserved member of the SHANK family, SHANK2, is regulated during activity-dependent spine growth (Figure 8). Because of the effects of SHANK overexpression on spine morphology, we again focused on spines whose morphology was similar to those from neurons expressing dsRed alone (in microns, dsRed spine width = 0.70 ± 0.02, length = 1.11 ± 0.05; SHANK2 width = 0.77 ± 0.03, length = 1.28 ± 0.07) (Figure S8).

Figure 8. Activity-Dependent Spine Growth Triggers Rapid and Transient Translocation of SHANK2 out of the Spine Head.

(A) Images from neurons expressing dsRed and PAGFP-SHANK2. Selected spines were photoactivated (white box, 0 min), and fluorescence was monitored over time as in Figure 4.

(B) Time course of PAGFP-SHANK2 fluorescence in spine heads after photoactivation (red, n = 19/3 spines/cells). The data corresponding to WT PSD-95-PAGFP are replotted (gray) for comparison, and statistically significant (p < 0.05) differences are indicated by open symbols.

(C) Images of spines from neurons expressing dsRed and PAGFP-SHANK2. A single spines was photoactivated (white box, 0 min) and stimulated with PS (arrowhead, 10 min).

(D) Time course of stimulated spine areas from neurons expressing dsRed and PAGFP-SHANK2 (red, n = 13/4 spines/cells). The gray area corresponds to activity-dependent spine growth measured in dsRed-expressing cells.

(E) Time course of PAGFP-SHANK2 fluorescence in spine heads after photoactivation and PS (red, n = 8/3 spines/cells). The gray area shows the PAGFP-SHANK2 fluorescence of unstimulated spines. Open red circles indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between stimulated and unstimulated spines.

(F) Time-lapse images of spines expressing dsRed and GFP-SHANK2. A single spine received PS (arrowhead, 10 min).

(G) Time course of GFP-SHANK2 fluorescence in spines after PS (black, n = 9/3 spines/cells). The black open circle indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) between the data at the 10 and 11 min time points.

Error bars depict the SEM.

In basal conditions, PAGFP-SHANK2 is less stable in the spine than PSD-95, such that a significant fraction of the green fluorescence is lost within 30 min of photoactivation (Figures 8A and 8B). In PAGFP-SHANK2-expressing spines, PS triggers normal growth (Δarearapid = 94% ± 11%, Δareapersistent = 28% ± 4%) and further destabilizes SHANK2, inducing a significant decrease in PAGFP-SHANK2 fluorescence compared to nonstimulated neighbors (Figures 8C–8E, S8B, and S8C). At the end of 30 min, a second photoactivation pulse recovered the initial levels of fluorescence, confirming that SHANK2-PAGFP was replenished with protein from a dendritic source. Similarly, in stimulated spines from neurons expressing GFP-SHANK2, total SHANK2 levels drop immediately but transiently after PS in a similar manner to PSD-95 (Figures 8F and 8G).

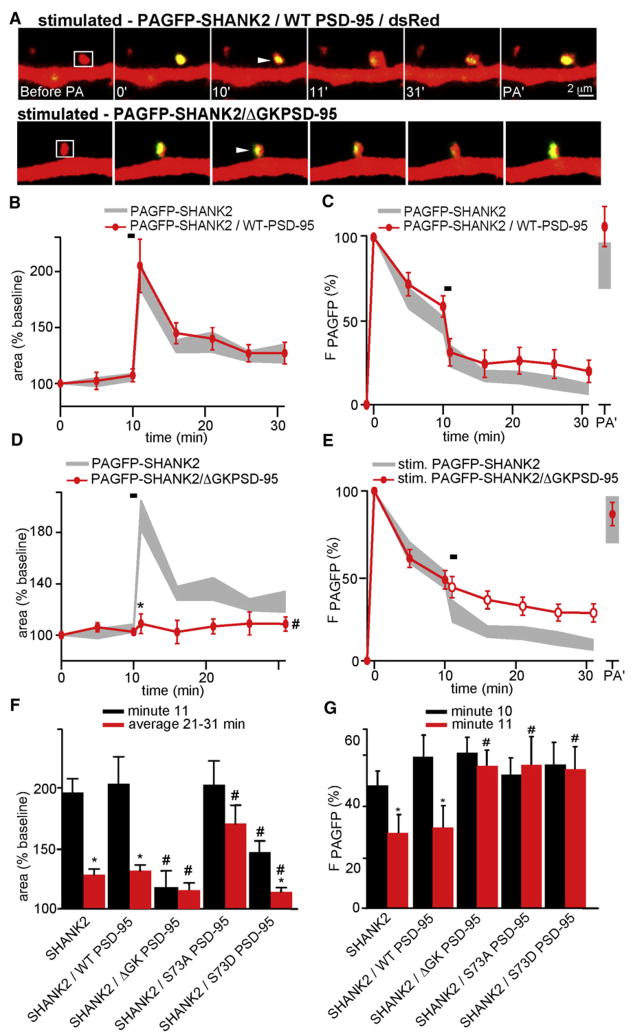

To determine whether the basal and activity-dependent trafficking of SHANK2 are regulated by PSD-95 in a GK- and S73-dependent manner, we examined the stability of PAGFP-SHANK2 in the spines of neurons expressing mutants of PSD-95 (Figure 9). In basal conditions, the stability of PAGFP-SHANK2 was unaffected by expression of WT PSD-95, S73A PSD-95, S73D PSD-95, or ΔGK PSD-95 (Figure S9). Thus, the basal stability of SHANK2 is not determined by interactions with PSD-95. In neurons coexpressing PAGFP-SHANK2 and WT PSD-95, PS-induced spine growth (Δarearapid = 94% ± 25%, Δareapersistent = 20% ± 4%) and translocation of SHANK2 was preserved and indistinguishable from that in neurons expressing PAGFP-SHANK2 alone (Figures 9A–9C).

Figure 9. The GK Domain and S73 of PSD-95 Regulate Activity-Dependent Trafficking of SHANK2.

(A) Images from neurons expressing dsRed, PAGFP-SHANK2, and either WT PSD-95 (top) or ΔGK PSD-95 (bottom). Spines were photoactivated (white box, 0 min) and stimulated with PS (arrowhead, 10 min).

(B) Time course of head area of stimulated spines from neurons expressing dsRed, WT PSD-95, and PAGFP-SHANK2 (red, n = 15/5 spines/cells). The gray area corresponds to data for spines expressing dsRed and PAGFP-SHANK2.

(C) Time course of PAGFP fluorescence from spines expressing dsRed, WT PSD-95, and PAGFP-SHANK2 that received PS (red, n = 15/5 spines/cells). The gray area corresponds to data for spines expressing dsRed and PAGFP-SHANK2 and stimulated by PS.

(D) As in panel (B) for spines of neurons expressing dsRed, ΔGK PSD-95, and PAGFP-SHANK2 (red, n = 20/5 spines/cells).

(E) As in panel (C) for spines of neurons expressing dsRed, ΔGK PSD-95, and PAGFP-SHANK2 and stimulated with PS (red, n = 20/5 spines/cells). Open circles indicate p < 0.05 compared to data for spines expressing dsRed and PAGFP-SHANK2 (gray).

(F) Summary graph of relative areas at minute 11 (black) or averaged between minutes 21 and 31 (red) of spines from neurons of the indicated genotypes. * indicates p < 0.05 for comparisons within each genotype (black versus red bars). # indicates p < 0.05 for the comparison across genotypes to the data from WT PSD-95 and PAGFP-SHANK2 expressing neurons.

(G) Summary graph of PAGFP fluorescence at minutes 10 (black) and 11 (red) for spines of neurons of the indicated genotype and that received PS between these time points. * and # as in (F).

Error bars depict the SEM.

As was true of ΔGK PSD-95 expression alone, coexpression of ΔGK PSD-95 and PAGFP-SHANK2 prevented activity-dependent spine growth (Δarearapid = 11% ± 8%, Δareapersistent = 4% ± 6%) (Figures 9A, 9D, and 9F). Expression of ΔGK PSD-95 also prevented the destabilization of SHANK2 by PS (Figures 9E and S10). Furthermore, expression of PAGFP-SHANK2 and S73A or S73D PSD-95 preserves the growth-enhancing (Δarearapid = 91%± 24%, Δareapersistent = 83% ± 14%) or depressing (Δarearapid = 61% ± 30%, Δareapersistent = 12% ± 7%) phenotypes, respectively, of each PSD-95 mutant while preventing activity-dependent translocation of SHANK2 out of the spine (Figures 9F, 9G, and S11). Thus, the GK domain and regulation of S73 control not only trafficking of PSD-95 and activity-dependent spine growth but also trafficking of other associated PSD proteins, such as SHANK2.

DISCUSSION

Here, we examine the mechanisms of activity-dependent spine growth in CA1 pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. We find that activity-dependent spine growth is positively and negatively regulated by PSD-95 and CaMKII. Whereas pharmacological blockade of CaMKs permits transient PS-induced spine growth but eliminates its persistent phase (Matsuzaki et al., 2004), loss of PSD-95 inhibits both phases of spine growth. However, we also find that CaMKII and PSD-95 signal to terminate activity-dependent spine growth. Phosphorylation of PSD-95 at a CaMKII consensus site, S73, destabilizes PSD-95 in the PSD, triggering activity-dependent trafficking of PSD-95 and SHANK2 out of the active spine and termination of spine growth. Furthermore, although the regulation of S73 does not control the basal synaptic expression of AMPARs and NMDARs, phosphorylation at this residue inhibits LTP. Thus, the activity-dependent trafficking of PSD proteins provokes a rapid reorganization of the signaling pathways necessary to promote and sustain plasticity (Figure 10).

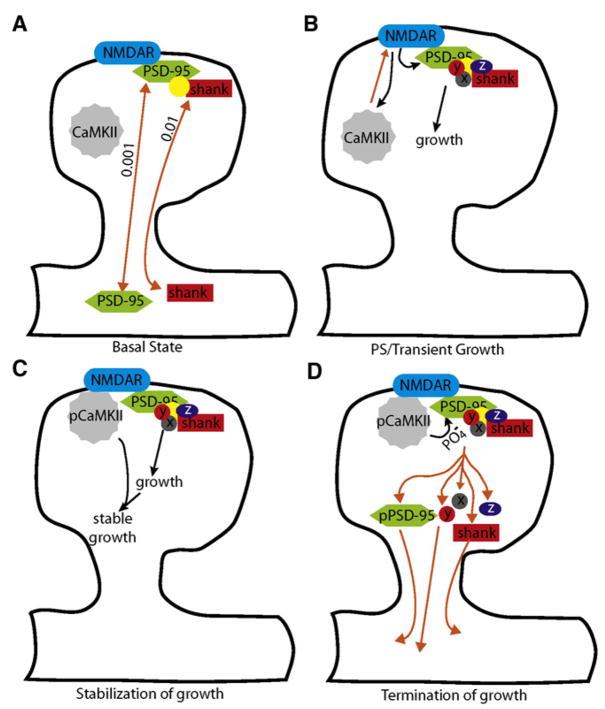

Figure 10. Model of Regulation of Activity-Dependent Structural Plasticity by CaMKII-Dependent Phosphorylation of PSD-95 at S73.

(A) In the basal state, PSD-95 molecules are stably incorporated in the PSD such that the rate of exchange of proteins across the spine neck is ~0.001/s. In contrast, SHANK molecules are exchanged at a higher rate of ~0.01/s. The basal rate of exchange of SHANK is independent of interactions with PSD-95 via GKAP (yellow circle) since overexpression of ΔGK PSD-95 or expression of destabilized PSD-95 mutants (S73D) does not alter the exchange rate of SHANK. Orange arrows represent protein movement, whereas black arrows (subsequent panels) schematize activation of signaling cascades.

(B) During plasticity-inducing stimulation, NMDAR opening causes the translocation of CaMKII to the PSD and stimulates the formation of a growth-promoting complex. This complex likely contains GKAP and SHANK as well as other proteins (symbolized by X, Y, and Z) that promote actin reorganization. The action of the growth-promoting complex requires PSD-95 since its knockdown or mutation of its N or C termini impairs spine growth.

(C) CaMKII and possibly other CaMKs stabilize activity-dependent growth and are necessary for the sustained phase of spine growth. The action of CaMKII is shown downstream of PSD-95 since mutants of PSD-95 eliminate all phases of spine growth, whereas blockade of CaMKs only prevents sustained growth.

(D) CaMKII phosphorylates PSD-95 at S73 and terminates spine growth by inducing the translocation of PSD-95 and SHANK out of the active spine, which we propose reflects the disassembly of the growth-promoting complex. It is possible that a PSD-95- and SHANK-containing complex is trafficked out of the active spine as a whole. The role of CaMKII in terminating growth and disassembling the complex are supported by the finding that the nonphosphorylatable mutant of PSD-95 (S73A) enhances growth and prevents the activity-dependent translocation of PSD-95 and SHANK. Furthermore, expression of a mutant that mimics phosphorylation (S73D) impairs growth and LTP. This mutant also basally destabilizes PSD-95, which we propose prevents the formation of a stable growth-promoting complex. The loss of PSD-95 and SHANK from the PSD is transient, and these proteins are rapidly replaced.

Molecular Mechanisms of Plasticity

The activities of many CaMKs are necessary for many forms of synaptic plasticity (Fink et al., 2003; Okamoto et al., 2007; Otmakhov et al., 2004; Saneyoshi et al., 2008; Schubert et al., 2006; Shen and Meyer, 1999; Shen et al., 2000; Xie et al., 2007; Yoshimura et al., 2000, 2002). In agreement with previous studies, we found that the sustained phase of spine growth that accompanies LTP requires activation of CaMKs (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004). Furthermore, we found that knockdown of PSD-95 significantly reduces spine growth, consistent with studies showing that acute knockdown of PSD-95 by shRNAs reduces AMPAR transmission, arrests the normal maturation of dendritic spines, and reduces spine size after chemical LTP (Ehrlich et al., 2007; Elias et al., 2006; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Schluter et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2008). Thus, activation of CaMKs, likely including CaMKII, and PSD-95 are necessary for the induction of synaptic plasticity downstream of NMDAR activation.

A conserved CaMKII phosphorylation site is found in the first PDZ domain of PSD-95 and its Drosophila homolog Dlg (Gardoni et al., 2006; Jaffe et al., 2004; Koh et al., 1999). In Drosophila, Dlg mutants that prevent or mimic phosphorylation at this site (S48) provoke structural abnormalities at the neuromuscular junction. In mammals, S73 is the major site of phosphorylation within the PDZ1 domain of PSD-95, and its phosphorylation regulates the association of PSD-95 with NMDARs (Gardoni et al., 2006). We found that replacement of S73 with unphosphorylatable alanine (S73A PSD-95) does not change the initial phase of the activity-dependent spine growth but dramatically increases the sustained phase. Conversely, replacement with the phosphomimetic residue aspartate (S73D PSD-95) impairs both phases of spine growth and blocks LTP. Thus, phosphorylation of PSD-95 at S73 by CaMKII likely limits structural and functional plasticity associated with LTP.

The enhancement (S73A) or repression (S73D) of activity-dependent spine growth by S73 mutants may arise from stabilization or destabilization, respectively, of a growth-promoting complex. Consistent with this hypothesis, the stability of S73D PSD-95 in the spine is reduced compared to that of S73A PSD-95 and WT PSD-95. Furthermore, the stability of neither mutant was affected by PS, suggesting that the S73A inhibited whereas S73D occluded activity-dependent trafficking of PSD-95 out of the spine. Previous studies have indicated that phosphorylation of PSD-95 at other sites also affects its synaptic localization and clustering. For example, Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of PSD-95 regulates clustering of NMDARs/PSD-95 (Morabito et al., 2004), whereas phosphorylation by Rac1-JNK1 enhances its synaptic localization and affects LTD (Futai et al., 2007).

PSD-95 is a multifunctional protein that interacts with many cytoskeletal regulatory elements that may allow it to participate in an activity-dependent growth-promoting complex. The first PDZ domain of PSD-95 contains the CaMKII phosphorylation site and, along with the second PDZ domain, interacts with NMDARs and the spine morphogen karilin-7 (Kornau et al., 1995; Penzes et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2007). We find that a mutant of PSD-95 that lacks the first two PDZ domains (ΔPDZ1/2 PSD-95) impairs activity-dependent spine growth, consistent with disruption of synaptic localization and activation of kalirin-7 downstream of NMDAR opening (Schnell et al., 2002; Xie et al., 2007). The C terminus of PSD-95 contains a nonfunctional guanylate kinase (GK) domain that indirectly recruits SHANK to the PSD (Naisbitt et al., 1999). We find that deletion of the GK domain of PSD-95 completely prevents both transient and sustained spine growth, suggesting that it links PSD-95 to a signaling cascade necessary for activity-dependent spine growth. In addition, neither S73A-ΔGK PSD-95 nor S73D-ΔGK PSD-95 supports activity-dependent spine growth, indicating that GK-dependent signaling is downstream of the CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of PSD-95. In contrast, previous studies have found that expression of ΔGK PSD-95 has effects on AMPARs and NMDAR EPSCs that are indistinguishable from those of expression of WT PSD-95 (Schnell et al., 2002). In combination with our findings, these results reaffirm that the effects of PSD-95 on AMPARs can be separated from those on spine morphology. In addition, we recently reported that the roles of PSD-95 in LTD and in the regulation of basal synaptic AMPAR number can also be dissociated (Xu et al., 2008). Thus, PSD-95, likely through its multiple protein-protein interaction motifs and due to its high copy number in the PSD, regulates many distinct and separable aspects of synapse structure, function, and plasticity.

Our data support the hypothesis that PSD-95, GKAP, and SHANK act as a transient signaling complex that promotes activity-dependent spine growth and is actively translocated out of the spine to terminate growth (Figure 10). SHANK interacts with many proteins that regulate the actin cytoskeleton, such as PAK, βPIX, α-fodrin, Abp1, and cortactin (Bockers et al., 2001; Naisbitt et al., 1999; Park et al., 2003; Qualmann et al., 2004), and is thought to build a signaling and structural platform that transmits signals from NMDARs to the cytoskeleton (Baron et al., 2006; Boeckers, 2006; Schubert and Dotti, 2007). PSD-95 likely acts upstream of SHANK2 as expression of ΔGK PSD-95 not only inhibited spine growth but also prevented the PS-induced translocation of SHANK2 out of the active spine. However, the GK domain of PSD-95 also forms a complex with SPAR, a RapGAP that causes enlargement of spine heads by reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton (Pak et al., 2001). Thus, it is possible that interruption of the interaction with SPAR contributes to the impairments caused by ΔGK PSD-95. PSD-95 S73 also controls the activity-dependent trafficking of SHANK2, as mutation of this site renders the stability of SHANK2 activity independent. Since CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of PSD-95 disrupts its interaction with NMDARs (Gardoni et al., 2006), we speculate that the removal of a fraction of PSD-95 from the spine terminates the growth- and plasticity-promoting signaling cascades that are activated downstream of NMDAR opening.

The mechanisms of transient spine growth are unclear, and the amplitude of this phase isvariable across studies (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Matsuzaki et al., 2004; Tanaka et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008). The transient phase of spine growth is prevented by expression of mutants of PSD-95, suggesting that a PSD-95-dependent signal is necessary for its expression. However, a component of transient growth may also result from ionic fluxes during the strong stimulation of NMDARs used to induce plasticity.

Conclusion

We have examined the pathways that mediate activity-dependent spine growth and trafficking of PSD proteins. We find that spine growth elicited by LTP induction requires signaling through PSD-95 and provokes the transient removal of PSD-95 and SHANK2 from active spines. Furthermore, we find that the multiple functions of PSD-95 in the regulation of basal synaptic transmission, induction of functional plasticity, and morphological plasticity are molecularly dissociable. Its participation in many distinct signaling pathways, including those studied here that are independent of glutamate receptor regulation, may explain why the number of PSD-95 molecules present in the PSD is far greater than the number of glutamate receptors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal Handling

Animal handling and euthanasia were carried out using Harvard Medical School approved protocols and in accordance with federal guidelines.

Hippocampal Slice Cultures and Transfection

Studies were carried out in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures prepared from postnatal day 5–7 Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (Stoppini et al., 1991; Tavazoie et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008). Slices were biolistically transfected at 2 days in vitro (DIV 2) and imaged at 7–10 DIV. Bullets were prepared using 12.5 mg of 1.6 μm gold particles and either 80 μg of plasmid DNAs for double transfection (40 μg of each) or 75 μg for triple transfection (25 μg of each). For EPSC recordings, hippocampal slice cultures were prepared as previously described (Schluter et al., 2006). For lentiviral transduction, concentrated viral solutions were injected into the CA1 pyramidal cell layer using a Picospritzer II (General Valve). Recordings were done 5–8 days after infection. Details of construction of DNA plasmids and of evaluation of their expression levels are given in the Supplemental Methods.

Imaging, Pharmacological Treatments, and Uncaging

All experiments were performed at room temperature. The experiments examining PSD-95-PAGFP and PAGFP-SHANK2 were performed in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, in mM: 125 NACl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaHPO4, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 20 D-glucose) gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. For spine stimulation with 2PLU of MNI-glutamate, ACSF contained 0 MgCl2, 4 mM CaCl2, 2.5 mM MNI-glutamate (Tocris), and 1 μM TTX. When indicated, hippocampal slices were preincubated with 10 μM CPP for 30 min, 10 μM KN-92 for 1 hr, 10 μM KN-93 for 1 hr, and the drugs were left in the bath during the imaging session. Transfected CA1 pyramidal neurons were identified based on their red fluorescence and morphology. Spines of primary or second branches of apical dendrite were imaged using a custom two-photon microscope (Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2005). For imaging ~35 mW of 920 nm light entered the back aperture of the objective (LUMFL 60 × 1.10 NA objective, Olympus) whereas for uncaging ~75 mW of 720 nm light was used. For each dendritic segment, a 3D image was collected at slice spacing of 1 μm and pixel spacing of 0.19 μm every 5 min. The LTP-induction stimulus consisted of 40 500 μs laser pulses delivered in 1 min to a spot ~1 μm away from the targeted spine head. Image stacks were acquired immediately after uncaging and then every 5 min over 30 min.

For photoactivation, a region of interest centered on the spine was selected (see Figure 1). The photoactivating light (730 nm) was delivered to this area in the slice containing the maximal intensity values of spine head fluorescence and in the slice above and below. Because of delays in moving the objective and completely imaging the dendritic image, the first image stack was collected ~1 min after the photoactivation pulses. Because of the rapid mobility of freely diffusing PAGFP and the low dependence of diffusion coefficients on molecular weight, all unanchored PAGFP-tagged proteins are expected to be cleared from the spine head in this 1 min interval (Bloodgood and Sabatini, 2005; Swaminathan et al., 1997). Therefore, fluorescence in the first image stack after photoactivation arises from diffusionally restricted, PAGFP-tagged proteins within the spine head. For experiments combining 2PLU of MNI-glutamate and photoactivation, photoactivation was performed with 810 nm light, which does not induce spine growth and is thus suitable to photoactivate PAGFP in the presence of MNI-glutamate (Figure S8).

Measurement of AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs

A single slice was removed from the insert and placed in a recording chamber constantly perfused with ACSF containing (in mM) 119 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 4 MgSO4, 4 CaCl2, and continually bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Picrotoxin (50 μM) was included to isolate EPSCs, and chloroadenosine (1–2 μM) was added to reduce polysynaptic activity. AMPAR and NMDAR EPSCs were recorded in simultaneous whole-cell recordings from an infected and closely adjacent uninfected cell as described previously (Xu et al., 2008). Comparisons between infected and uninfected cell responses were done using paired t tests (Table S1). Statistical analyses among different constructs and conditions were done by ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple pairwise comparisons.

Measurment of LTP

Whole-cell recordings were obtained from CA1 pyramidal neurons using glass electrodes (4.5–5.5 MΩ) filled with internal solution containing (in mM) 135 KMeSO3, 10 HEPES, 4 MgCl2, 4 Na2ATP, 0.4 NaGTP, and 10 Na2 Creatine PO4, 0.05 Alexa Fluor 594, pH to 7.3 with KOH. Voltage-clamp recordings (−70 mV) were made using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz. Series resistance (20–40 MΩ) was not compensated. High-resistance pipettes and high-series-resistance recordings were used to prevent rapid wash-out of LTP from the recorded neuron. Stimuli consisted of a 0.5 ms laser pulse directed ~1 μm from the spine head. For each spine, a “best spot” was determined by uncaging in three to four positions around the periphery of the spine head and identifying the location that elicited the largest uEPSC (Busetto et al., 2008). Baseline data consisted of approximately five stimuli (15 s inter-stimulus interval) delivered to the “best spot.” LTP was induced by delivering 40 stimuli (1.75 s interstimulus interval) to the same uncaging location. As the spine head typically exhibited significant growth following induction, the uncaging location was shifted to the new optimal location (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007). uEPSC amplitude was measured as the average amplitude in a 6 ms window starting 3 ms after the end of the uncaging pulse. Comparisons between the average pre- and postinduction uEPSCs were made using a paired Student’s t test.

For the measurements of the effects of mutations of PSD-95 S73 on LTP, hippocampal organotypic slices were biolistically transfected with GFP alone or with GFP and either WT PSD-95, S73A PSD-95, or S73D PSD-95. A spine from a primary or secondary dendritic branch was stimulated with PS. 15–20 min after PS, a whole-cell voltage-clamp recording was obtained, and measurements of uEPSCs at the PS-stimulated spine and its neighbors were performed using 1 ms uncaging pulses. uEPSCPS and uEPSCcontrol in each genotype were compared using a Student’s t test. Rpot was calculated for each cell as uEPSCPS/<uEPSCcontrol>. As appropriate when averaging calculated ratios of two randomly distributed variables, the geometric mean was used to obtain the average Rpot for each genotype. Comparisons across genotypes were made using ANOVA of log(Rpot) with Tukey correction for multiple pairwise comparisons. To calculate the average uEPSCcontrol traces shown in the left column of Figures 5B–5E, all uEPSCs measured for control spines of each genotype were averaged together. To calculate the normalized uEPSCcontrol and uEPSCPS traces shown in the right column of Figures 5B–5E, the average uEPSCcontrol amplitude was calculated for each cell, and uEPSCcontrol and uEPSCPS traces for that cell were divided by this value. These normalized traces were average together for each genotype to produce an average uEPSCcontrol with peak amplitude set to 1 and an average uEPSCPS whose amplitude reflects Rpot.

Fluorescence Analysis

Fluorescence intensities were analyzed using custom software written in Matlab (Mathworks). For each spine and time point, the user marked the major axis along the length of the spine and a minor axis intersecting the major axis at the point of maximal dsRed intensity in the spine head. The area in which the fluorescence intensity of dsRed remained above 30% of its maximal value was defined as the spine head mask, and the number of pixels within it defined the spine head area. The distances to 30% of maximal fluorescence along the minor and major axis were used to define, respectively, the apparent head width and spine length. Relative changes in spine volume were estimated from changes in the peak dsRed fluorescence intensity in the spine head, which is monotonically related to spine head volume (Holtmaat et al., 2005; Sabatini and Svoboda, 2000). For analysis of GFP or PAGFP signals, total green fluorescence within the spine head mask was calculated at each time point and expressed relative to, respectively, the baseline fluorescence or increase above baseline fluorescence triggered by the photoactivating pulse. This proportional value is referred to as FPAGFP or FGFP. The time of acquisition of the first image after the photoactivating pulse is referred to as t = 0 min and by definition FPAGFP(0) = 100%. Bleed-through of dsRed fluorescence in the green channel was estimated as the fraction of the red total fluorescence intensity present in the spine head before photoactivation for PAGFP experiments and as the one present in the dendritic shaft for GFP experiments. Each cross-talk term was subtracted from the green fluorescence intensity.

Spine volume was calculated as the volume of the excitation point-spread function (0.33 fl our microscope) multiplied by the ratio of the peak spine fluorescence to the peak fluorescence in a thick portion of the apical dendrite that completely engulfed the PSF (Holtmaat et al., 2005; Sabatini and Svoboda, 2000). In prestimulus spines of dsRed-expressing neurons, the average spine volume was 0.13 ± 0.06 fl (range 0.09–0.18 fl), within the normal distribution of spine volumes in hippocampal pyramidal neurons measured by serial section electron microscopy (Harris and Stevens, 1989).

In all summary graphs, the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) is shown. In some figures, a shaded region is used to replot data from earlier figures and depicts the area between the mean ± SEM of this data. In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Sabatini lab, Christoph Bernoulli, Brett Carter, Yariv Levy, and Claudio Acuna-Goycolea for helpful discussions; X. Cai, A. Ghosh, and O. Schluter for technical support; and B. Glick, H. Hirling, T. Meyer, R.A. Nicoll, S. Okabe, G. Patterson, and M. Sheng for gifts of reagents. This work was funded by (to B.L.S.) grants from the Dana and McKnight Foundations and NINDS (NS052707); (to P.S.) a fellowship from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PA00A-113192/1); (to W.X.) an NRSA from NIMH (MH080310); and (to R.C.M.) a grant from NIMH (MH063394).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA The Supplemental Data include Supplemental Materials and Methods and a table and can be found with this article online at http://www.neuron.org/supplemental/S0896-6273(08)00887-8.

References

- Baron MK, Boeckers TM, Vaida B, Faham S, Gingery M, Sawaya MR, Salyer D, Gundelfinger ED, Bowie JU. An architectural framework that may lie at the core of the postsynaptic density. Science. 2006;311:531–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1118995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beique JC, Andrade R. PSD-95 regulates synaptic transmission and plasticity in rat cerebral cortex. J Physiol. 2003;546:859–867. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloodgood BL, Sabatini BL. Neuronal activity regulates diffusion across the neck of dendritic spines. Science. 2005;310:866–869. doi: 10.1126/science.1114816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockers TM, Mameza MG, Kreutz MR, Bockmann J, Weise C, Buck F, Richter D, Gundelfinger ED, Kreienkamp HJ. Synaptic scaffolding proteins in rat brain. Ankyrin repeats of the multidomain Shank protein family interact with the cytoskeletal protein alpha-fodrin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40104–40112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckers TM. The postsynaptic density. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:409–422. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0274-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckers TM, Kreutz MR, Winter C, Zuschratter W, Smalla KH, Sanmarti-Vila L, Wex H, Langnaese K, Bockmann J, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED. Proline-rich synapse-associated protein-1/cortactin binding protein 1 (ProSAP1/CortBP1) is a PDZ-domain protein highly enriched in the postsynaptic density. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6506–6518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06506.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busetto G, Higley MJ, Sabatini BL. Developmental presence and disappearance of postsynaptically silent synapses on dendritic spines of rat layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2008;586:1519–1527. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.149336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Vinade L, Leapman RD, Petersen JD, Nakagawa T, Phillips TM, Sheng M, Reese TS. Mass of the postsynaptic density and enumeration of three key molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11551–11556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505359102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Malinow R. Postsynaptic density 95 controls AMPA receptor incorporation during long-term potentiation and experience-driven synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:916–927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4733-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich I, Klein M, Rumpel S, Malinow R. PSD-95 is required for activity-driven synapse stabilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini AE, Craven SE, Chetkovich DM, Firestein BL, Schnell E, Aoki C, Bredt DS. Dual palmitoylation of PSD-95 mediates its vesiculotubular sorting, postsynaptic targeting, and ion channel clustering. J Cell Biol. 2000a;148:159–172. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Husseini AE, Schnell E, Chetkovich DM, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. PSD-95 involvement in maturation of excitatory synapses. Science. 2000b;290:1364–1368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias GM, Funke L, Stein V, Grant SG, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Synapse-specific and developmentally regulated targeting of AMPA receptors by a family of MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Neuron. 2006;52:307–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink CC, Bayer KU, Myers JW, Ferrell JE, Jr, Schulman H, Meyer T. Selective regulation of neurite extension and synapse formation by the beta but not the alpha isoform of CaMKII. Neuron. 2003;39:283–297. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futai K, Kim MJ, Hashikawa T, Scheiffele P, Sheng M, Hayashi Y. Retrograde modulation of presynaptic release probability through signaling mediated by PSD-95-neuroligin. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:186–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardoni F, Polli F, Cattabeni F, Di Luca M. Calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation modulates PSD-95 binding to NMDA receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:2694–2704. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NW, Weimer RM, Bureau I, Svoboda K. Rapid redistribution of synaptic PSD-95 in the neocortex in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Stevens JK. Dendritic spines of CA 1 pyramidal cells in the rat hippocampus: serial electron microscopy with reference to their biophysical characteristics. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2982–2997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-08-02982.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Svoboda K. Locally dynamic synaptic learning rules in pyramidal neuron dendrites. Nature. 2007;450:1195–1200. doi: 10.1038/nature06416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, Svoboda K. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y, Udo H, Inokuchi K, Sugiyama H. Homer1a regulates the activity-induced remodeling of synaptic structures in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;150:841–852. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe H, Vinade L, Dosemeci A. Identification of novel phosphorylation sites on postsynaptic density proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:771–781. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Naisbitt S, Hsueh YP, Rao A, Rothschild A, Craig AM, Sheng M. GKAP, a novel synaptic protein that interacts with the guanylate kinase-like domain of the PSD-95/SAP90 family of channel clustering molecules. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:669–678. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh YH, Popova E, Thomas U, Griffith LC, Budnik V. Regulation of DLG localization at synapses by CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation. Cell. 1999;98:353–363. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81964-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornau HC, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH. Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science. 1995;269:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.7569905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee K, Hwang S, Kim SH, Song WK, Park ZY, Chang S. SPIN90/WISH interacts with PSD-95 and regulates dendritic spinogenesis via an N-WASP-independent mechanism. EMBO J. 2006;25:4983–4995. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Ellis-Davies GC, Nemoto T, Miyashita Y, Iino M, Kasai H. Dendritic spine geometry is critical for AMPA receptor expression in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/nn736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaud M, Charlesworth P, Dempster M, Webster LC, Watabe AM, Makhinson M, He Y, Ramsay MF, Morris RG, Morrison JH, et al. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature. 1998;396:433–439. doi: 10.1038/24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito MA, Sheng M, Tsai LH. Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 phosphorylates the N-terminal domain of the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95 in neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:865–876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4582-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naisbitt S, Kim E, Tu JC, Xiao B, Sala C, Valtschanoff J, Weinberg RJ, Worley PF, Sheng M. Shank, a novel family of postsynaptic density proteins that binds to the NMDA receptor/PSD-95/GKAP complex and cortactin. Neuron. 1999;23:569–582. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada C, Ritchie K, Oba Y, Nakamura M, Hotta Y, Iino R, Kasai RS, Yamaguchi K, Fujiwara T, Kusumi A. Accumulation of anchored proteins forms membrane diffusion barriers during neuronal polarization. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:626–632. doi: 10.1038/ncb1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Futai K, Lashuel HA, Lo I, Okamoto K, Walz T, Hayashi Y, Sheng M. Quaternary structure, protein dynamics, and synaptic function of SAP97 controlled by L27 domain interactions. Neuron. 2004;44:453–467. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimchinsky EA, Yasuda R, Oertner TG, Svoboda K. The number of glutamate receptors opened by synaptic stimulation in single hippocampal spines. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2054–2064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5066-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Lujan R, Laube G, Roberts JD, Molnar E, Somogyi P. Cell type and pathway dependence of synaptic AMPA receptor number and variability in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1998;21:545–559. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe S, Kim HD, Miwa A, Kuriu T, Okado H. Continual remodeling of postsynaptic density and its regulation by synaptic activity. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:804–811. doi: 10.1038/12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Narayanan R, Lee SH, Murata K, Hayashi Y. The role of CaMKII as an F-actin-bundling protein crucial for maintenance of dendritic spine structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6418–6423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701656104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmakhov N, Tao-Cheng JH, Carpenter S, Asrican B, Dosemeci A, Reese TS, Lisman J. Persistent accumulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dendritic spines after induction of NMDA receptor-dependent chemical long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9324–9331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2350-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak DT, Yang S, Rudolph-Correia S, Kim E, Sheng M. Regulation of dendritic spine morphology by SPAR, a PSD-95-associated RapGAP. Neuron. 2001;31:289–303. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Na M, Choi J, Kim S, Lee JR, Yoon J, Park D, Sheng M, Kim E. The Shank family of postsynaptic density proteins interacts with and promotes synaptic accumulation of the beta PIX guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rac1 and Cdc42. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19220–19229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301052200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GH, Lippincott-Schwartz J. A photoactivatable GFP for selective photolabeling of proteins and cells. Science. 2002;297:1873–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.1074952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penzes P, Johnson RC, Sattler R, Zhang X, Huganir RL, Kambampati V, Mains RE, Eipper BA. The neuronal Rho-GEF Kalirin-7 interacts with PDZ domain-containing proteins and regulates dendritic morphogenesis. Neuron. 2001;29:229–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann B, Boeckers TM, Jeromin M, Gundelfinger ED, Kessels MM. Linkage of the actin cytoskeleton to the postsynaptic density via direct interactions of Abp1 with the ProSAP/Shank family. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2481–2495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5479-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Analysis of calcium channels in single spines using optical fluctuation analysis. Nature. 2000;408:589–593. doi: 10.1038/35046076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala C, Piech V, Wilson NR, Passafaro M, Liu G, Sheng M. Regulation of dendritic spine morphology and synaptic function by Shank and Homer. Neuron. 2001;31:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saneyoshi T, Wayman G, Fortin D, Davare M, Hoshi N, Nozaki N, Natsume T, Soderling TR. Activity-dependent synaptogenesis: regulation by a CaM-kinase kinase/CaM-kinase I/betaPIX signaling complex. Neuron. 2008;57:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikorski T, Stevens CF. Quantitative ultrastructural analysis of hippocampal excitatory synapses. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5858–5867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05858.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter OM, Xu W, Malenka RC. Alternative N-terminal domains of PSD-95 and SAP97 govern activity-dependent regulation of synaptic AMPA receptor function. Neuron. 2006;51:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell E, Sizemore M, Karimzadegan S, Chen L, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Direct interactions between PSD-95 and stargazin control synaptic AMPA receptor number. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13902–13907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172511199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert V, Dotti CG. Transmitting on actin: synaptic control of dendritic architecture. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:205–212. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert V, Da Silva JS, Dotti CG. Localized recruitment and activation of RhoA underlies dendritic spine morphology in a glutamate receptor-dependent manner. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:453–467. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Fong DK, Craig AM. Postsynaptic protein mobility in dendritic spines: long-term regulation by synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:702–712. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K, Meyer T. Dynamic control of CaMKII translocation and localization in hippocampal neurons by NMDA receptor stimulation. Science. 1999;284:162–166. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K, Teruel MN, Connor JH, Shenolikar S, Meyer T. Molecular memory by reversible translocation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:881–886. doi: 10.1038/78783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng M, Kim E. The Shank family of scaffold proteins. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1851–1856. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.11.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, Gibson ES, Dell’Acqua ML. cAMP-dependent protein kinase postsynaptic localization regulated by NMDA receptor activation through translocation of an A-kinase anchoring protein scaffold protein. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2391–2402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3092-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein V, House DR, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic density-95 mimics and occludes hippocampal long-term potentiation and enhances long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5503–5506. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05503.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppini L, Buchs PA, Muller D. A simple method for organotypic cultures of nervous tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90128-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan R, Hoang CP, Verkman AS. Photobleaching recovery and anisotropy decay of green fluorescent protein GFP-S65T in solution and cells: cytoplasmic viscosity probed by green fluorescent protein translational and rotational diffusion. Biophys J. 1997;72:1900–1907. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78835-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takumi Y, Ramirez-Leon V, Laake P, Rinvik E, Ottersen OP. Different modes of expression of AMPA and NMDA receptors in hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:618–624. doi: 10.1038/10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka JI, Horiike Y, Matsuzaki M, Miyazaki T, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Protein synthesis and neurotrophin-dependent structural plasticity of single dendritic spines. Science. 2008;319:1683–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.1152864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie SF, Alvarez VA, Ridenour DA, Kwiatkowski DJ, Sabatini BL. Regulation of neuronal morphology and function by the tumor suppressors Tsc1 and Tsc2. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1727–1734. doi: 10.1038/nn1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuriel S, Geva R, Zamorano P, Dresbach T, Boeckers T, Gundelfinger ED, Garner CC, Ziv NE. Local sharing as a predominant determinant of synaptic matrix molecular dynamics. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultanir SK, Kim JE, Hall BJ, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Ghosh A. Regulation of spine morphology and spine density by NMDA receptor signaling in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19553–19558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]