Introduction

Maintaining a good quality of life (QOL) is as important as survival to most patients living with chronic, progressive illness.1 Individuals with heart failure have markedly impaired QOL compared to with other chronic diseases as well as healthy population.2-5 Quality of life reflects the multidimensional impact of a clinical condition and its treatment on patients’ daily lives.6-8 Patients with heart failure experience various physical and emotional symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, edema, sleeping difficulties, depression, and chest pain.9, 10 These symptoms limit patients’ daily physical and social activities and result in poor QOL.11-16 Poor QOL is related to high hospitalization and mortality rates.17, 18 Therefore, QOL in patients with heart failure should be assessed appropriately to determine its impact on patients’ daily lives.

Quality of life is subjective and does not merely reflect objective clinical, or physiological status.2, 8, 19-21 It reflects patients’ subjective perceptions about the impact of a clinical condition on their lives.22-24 People with similar conditions commonly have different perceptions of their QOL, and outcomes vary based on patients’ subjective views.25, 26 In a study comparing physicians’ prediction about patients’ health perception and patients own health perception, 51% of the cases differed, and patients’ health perceptions had an important impact on use of health care.25 Few investigators have examined QOL from patients’ perspectives. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the perceptions of patients with heart failure about QOL.

Methods

Sample and Setting

A convenience sample of 20 patients with heart failure who lived in a Midwestern city participated in this qualitative study. Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of confirmed heart failure, New York Heart Association functional classes (NYHA) II to IV, and ability to speak English. Exclusion criterion was severe psychiatric or cognitive problems. The diagnosis of heart failure was confirmed by medical record reviews. The approval of the appropriate Institutional Review Board was obtained. Written, informed consent for participation in this study for audio-recording were obtained from all patients after explanation of the purpose and procedure of the study.

Data Collection and Analysis

The primary investigator interviewed all patients individually. Semi-structured interviews were guided by a set of questions to standardize the content of interviews. Questions included issues related to the impact of heart failure on daily life, definition and self-evaluation of quality of life, and factors affecting patients’ quality of life. Questions for the semi-structured interviews were developed by the primary investigators, and two experts in heart failure reviewed and revised the questions. All interviews were conducted in a private room in the General Clinical Research Center of a university affiliated hospital in 2005 and 2006. All interviews were audio-taped. All interviews were transcribed verbatim by either the primary investigator or a transcription specialist. The transcribed interviews and audio-tapes were carefully compared by two investigators, the primary investigator and one of the other investigators, for accuracy.

The transcribed interviews were analyzed by the primary investigator using content analysis. The transcribed interviews were read repeatedly for overall impressions, to determine prominent themes and patterns, and to enhance credibility and reduce personal biases. The data were coded and named based on shared concepts. The transcribed interviews and the coding scheme were reviewed by two of the other investigators separately for the first three interviews to enhance confirmability and to minimize personal biases. Each disagreement was discussed until a consensus was reached. After the investigators’ agreement on the coding scheme, analysis of the remainder of the interviews was continued by the primary investigator. The transcribed interviews and the coding of the interviews were also reviewed by two of the other investigators to enhance trustworthiness. The codes were grouped into larger categories based on the content, and reduced to major themes through ongoing discussion by the investigators. Demographic characteristics (age, education level, ethnicity, gender, marital status, and living arrangement) were collected using a demographic questionnaire. Functional status (NYHA class) was assessed by patient interview.

Results

Characteristics of Sample

The demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Mean age of the sample was 58 years old, and 70% were men. The majority (90%) were Caucasian. Only sixty percent of the patients were married, but most (75%) lived with someone. The majority of patients had co-morbidities that included hypertension (80%), atrial fibrillation (45%), diabetes (30%), or kidney disease (20%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample (N = 20)

| Characteristics | Mean (± SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58 (± 10) |

| Education (years) | 15 (± 3) |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian) | 18 (90) |

| Male | 14 (70) |

| Marital status (married) | 12 (60) |

| Living arrangement (live with someone) | 15 (75) |

| New York Heart Association functional class | |

| NYHA II | 6 (30) |

| NYHA III | 8 (40) |

| NYHA IV | 6 (30) |

| Heart failure etiology (ischemic) | 11 (55) |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction | 34 (± 12) |

| Co-morbidities/Treatment | |

| Hypertension (yes) | 16 (80) |

| Arterial fibrillation (yes) | 9 (45) |

| Diabetes (yes) | 6 (30) |

| Kidney disease (yes) | 4 (20) |

| Treatment | |

| Implantable cardiovascular defibrillator (yes) | 9 (45) |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery (yes) | 5 (25) |

Patients’ Definition of Quality of Life

Patients’ definitions of QOL included three components: 1) ability to perform physical and social activities, 2) maintaining happiness, and 3) engaging in fulfilling relationships. The most common definition of QOL was the ability to perform physical and social activities. One patient defined QOL as the ability to engage in recreational activities. “…but it [QOL] means if I got a phone call and they said, would you like to go to Alabama fishing?, or would you like to go somewhere?, we’re taking a trip and …..Have the energy to do that” Another patient defined QOL as ability to perform both routine and social activities.

Quality of life probably means how well you can do what has to be done like bathing and dressing and feeding, what needs to be done like house cleaning and grocery shopping, and what you want to do like visiting friends or going shopping, something like that. So, it’s how…quality of life is how well you can do those things.

Some patients focused more on psychological factors, particularly happiness and satisfaction. “Quality of life means, are you happy most of the time? Are you satisfied with what’s going in your life?”

Some patients provided a more comprehensive definition of QOL.

The ability to be at peace and joy, and doing the things you want to do with the people you want to do it with. Quality of life, the better quality of life you have, the better you can do the things that you want to do and enjoy activities with your family.

There were examples of QOL defined as fulfilling relationships. “[QOL is] living with…through pain and having a chance to be with the people you love and being loved. I guess, that’s important.” “That’s [QOL is] having family around you that support you, feeling good…”

Patients’ Perceptions About Factors Affecting Quality of Life

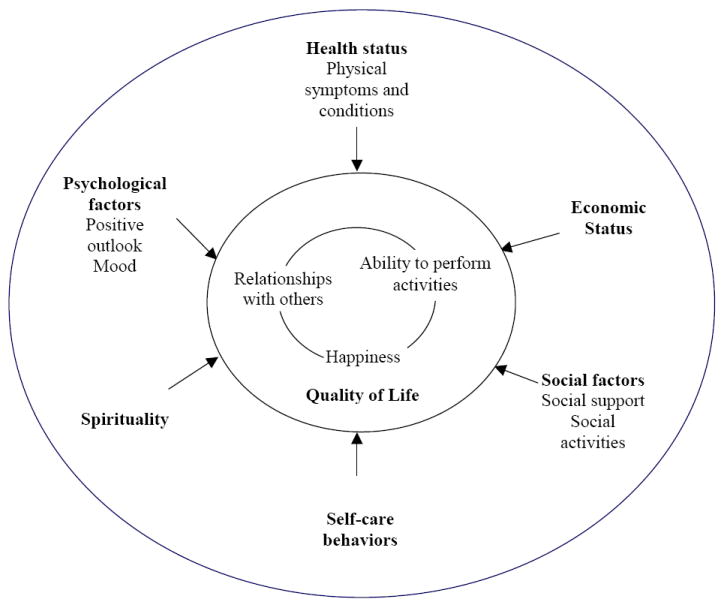

Patients believed that their health status, psychological factors, economic status, social factors, spirituality, and health-related behaviors affected their QOL. Health status included physical symptoms and physical condition. Economic status primarily included the impact of heart failure on finances. Social factors included social support and social activities. Spirituality was related to faith in God and praying. Health-related behaviors were primarily self-care activities.

Health status

Physical symptoms

Patients perceived that physical symptoms such as shortness of breath and chest pain had a negative impact on their QOL. “…the quality of life, you know, to not have shortness of breath, not have chest pain, to not have all of the things that would affect your daily living.” Another patient also reported that physical symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, and nausea impaired his QOL.

Like being out of breath affects my quality of life because that limits how much energy I have to do anything and also have…I don’t know how much directly related to my heart failure or not, but I have constant battle with nausea.

Physical condition

Several patients reported that their physical condition had an impact on their QOL. “I think to be in otherwise good physical condition, ideal weight, and good nutrition [had an impact on QOL].” “I might feel better if I could lose just a few pounds…I don’t know just…maybe rest and relaxation.” Some patients reported that their clinical condition such as their heart function had an impact on their QOL. “Well, one of the obstacles [to improve QOL] could be my heart.”

Psychological factors

Mood

Good mood had a positive impact on patients’ perception of their QOL. “And maintain good…I think even more than the body, you have to have a good mind and spirit to deal with the changes that your body…” Bad mood had a negative impact on patents’ perception about their QOL. “I guess just the barriers [to improve QOL] would be stressful situations, whether it be with family or home or community of whatever.”

Positive outlook

Many patients perceived that maintaining a positive perspective or attitude helped them maintain a good QOL.

I don’t blame my problems, or misfortunes, or good fortunes on anybody else. I just set goals, and work to attain them. You get a wall and instead of turning around or going back, you go through it or over it.

Patients said that they tried to do what they could do. “I don’t let it [heart failure] bother me. I just go out and do what I can do. When I get tired, I rest.” Some patients tried to maintain a positive attitude. “Try to remain positive and do the best you can.” Some patients maintained a positive attitude by considering the possibility of worse cases or comparing their situation with others’.

…the way I feel is that it could always be worse. I could be brain dead, or in a vegetative state or I could’ve lost some…I think I’m pretty good shape compared to some people. Some people are perfectly healthy and don’t know and don’t appreciate it.

Economic status

Several patients mentioned good or bad financial situations as affecting their QOL. “If Social Security suddenly went bankrupt or my pension stopped or, you know, my house burned down, that would affect my quality of life.” Some patients had difficulty buying their medications, and this difficulty negatively affected their QOL.

I’m…had to learn when I don’t have the money to buy a [medicine]…my kids tell me, you know, but it’s so hard. I’m getting better, you know, something happen before my check comes back in, I’ll ask them. They’re helping me, especially for my heart medicine.

Social factors

Social support

Patients perceived that personal and material support from their significant others had an impact on their QOL. “The most helpful thing to me is having someone to do the house cleaning because that takes physical load off of house cleaning, but gives me an environment that is more pleasant so live in.” Some patients mentioned that having a supportive environment in which their needs were met would improve their QOL.

It will be nice to have some accountability or group encouragement to watch diet to enthusiastically promote a healthy diet because you are expecting you have to cut out …something out instead of enjoy other things…it will be nice that grocery stores have low sodium food section or something because you have to look for every jar of sauce or every jar of pasta, compare every label to figure out which one is best…or even if there were a place you could order low sodium grocery online, that will be nice.

Social activities

Participation in social activities such as doing things with family or friends or working was also identified as a way to improve QOL. “To be around your friends, have the opportunity to go out…and having things to do.” Getting a job is also related to patients’ QOL. “Just mainly get a job.”

Spirituality

Faith or praying positively was identified as important to QOL by several patients. “Praying, this is the most important thing [to improve QOL].” “[Important thing to improve QOL is] let’s say…faith.”

Health-related behaviors

The majority of the patients mentioned performance of self-care related behaviors such as taking medications, following a low sodium diet, doing regular activity, weight control, and symptom management as ways to maintain a good QOL. “Well, the only thing I can do is keep taking my medication, and try the diet, and see if the diet will give me more strength.” “Take the medication, exercise, try to avoid the salt, and eat some, eat some better food, watch the weight, and if I have symptoms, then I should call the doctor.”

Evaluation of Health-Related Quality of Life

The majority of patients’ evaluated their QOL as very good or good, despite limitations in their daily lives. “I know I’ve had a lot of medical problems, but I really think my quality of life has been very good.” The reasons for the positive evaluation included the consideration of possible worse situations, ability to do some desired activities, and emotional happiness. “You can go to hospital, or some place and find people in worse condition, so as long as I am able to take care of myself…that’s good quality of life.” One patient evaluated her QOL based on what she could do compared with worse cases.

And here’s people in a lot worse shape than I’m in…so…as long as I am able to walk around and pick up the phone and call my kids or get in a car and drive down the road, then quality of life is…not too bad.

One patient thought about the possibility of death. “Even though I can’t do something that I can do before, I think it’s [QOL is] good. I should’ been dead so many times…and I am not…Thank God that I’m alive.” One patient evaluated his QOL based on his emotional happiness. “It’s [QOL is] very good. I’m quite happy.”

A few patients, however, evaluated their QOL negatively because of limitations in daily activities and in comparison to their previous condition. “Poor…I’ve gone from being a very active person to being a person that I can do as much as my body allows me…now I’m just a couch potato.” One patient wanted to improve his QOL to do what he wants to do.

I’m going to go fishing. If that’s where I pass away at, that’s where I was set up go. I worked 44 years, so I could go fishing…Scale of 1 to10, [my quality of life is] about a 4…and I want it to be about a 9 because I’ve got a lot of work to do to get my evaluation from 4 up to 9. So I’ve got a long way to go yet.

Discussion

Patients’ perceptions demonstrated the subjective, multi-dimensional nature of QOL. Their definitions of QOL reflected patients’ active pursuit of happiness and relationships with others, as well as the impact of heart failure on their daily activities. Patients reported that a variety of factors affected their QOL. Some of these factors, such as physical symptoms are well known to impair QOL, while other factors, such as positive outlook, economic status, social, and spiritual factors and self-care behaviors have not been considered as extensively in the literature as factors affecting QOL. Patients reported that their QOL was both negatively and positively affected by these factors. Often, patients’ positive self-evaluation of QOL contradicted their own definition of QOL and the factors affecting QOL.

Most definitions of QOL or health-related QOL used in heart failure research imply the subjective nature of QOL.5, 17, 22-24 Alla et al. defined QOL as “a multidimensional concept, based on the patient’s own perception of his health which integrates not only the functional or physical dimensions of the disease, but also psychological and social dimensions (p. 337).”17 The definition of health-related QOL used by Scott et al. also demonstrates the subjective nature: “the overall effect and outcome of an illness and its treatment on an individual’s physical, psychologic, and social well-being as perceived by that individual (p. 84).”22 However, few investigators have asked patients about their own definitions of QOL. The definitions of QOL provided by patients in this study were similar to those used in prior research, but the components of patients’ definitions reflected their active pursuit of a good QOL despite the negative impact of their condition.

Three components of patients’ definitions of QOL emerged: having the ability to perform physical and social activities, feeling happy in daily life, and having fulfilling relationships with their family and significant others. Definitions of QOL in prior studies also demonstrated the multidimensional nature of QOL.3, 7, 8 On one hand, patients’ physical ability as a component of QOL was related to their roles such as wife, parents, husband, and a member of society. On the other hand, their physical ability as a component of their QOL was related to activities they pursued to gain happiness. In prior studies,8, 27, 28 physical ability related to daily life was also a significant component of QOL. This physical ability in patients with heart failure is closely related to the impact of their clinical condition because the majority of patients with heart failure have symptoms such as dyspnea and fatigue,9, 29, 30 that limit their ability to perform daily activities.15

Other key components of patients’ definitions were psychological status (happiness or enjoyment of life) and social status (relationships with significant others). Several prior definitions of QOL have included psychosocial status or well-being as an important component.3, 6, 17, 22, 24, 27 Patients’ definitions, however, implied a more active meaning. In patients with heart failure, QOL does not mean the absence of emotional distress or psychological well-being; rather it is the ability to pursue happiness or enjoy spending time with significant others. This key component of the definition of QOL, in part, explains why many patients with heart failure evaluated their QOL positively despite considerable limitations in their daily lives. This key component implies that the QOL of patients with heart failure can be improved by changing patients’ psychological perceptions and providing opportunities for meaningful social interaction with friends, family and significant others as well as improving symptom status. Thus, inclusion of these key components in definitions of QOL may better reflect patients’ subjective, overall view of QOL in heart failure. However, instruments that are commonly used in heart failure to assess QOL do not reflect these positive aspects of QOL.31, 32 Further studies are needed to develop items reflecting these positive aspects of QOL and to compare existing instruments and newly developed instruments.

The majority of the patients reported that they had physical symptoms and limitations in daily activities due to heart failure, and symptoms and limitations were important factors affecting their QOL. Over 80% of patients with heart failure have physical symptoms such as dyspnea, fatigue, edema, sleeping difficulties, and chest pain,9, 29, 30 and symptom burden adversely affects QOL.6, 10, 19, 33 Worsening symptoms are the main antecedents of rehospitalization.34-36 Patients’ poor psychosocial status such as bad mood and difficulties in financial status negatively affected their QOL. Many patients had emotional distress and felt a burden to their family because of their physical symptoms, which limited their physical and social activities. Thirty to forty percent of patients with heart failure have emotional distress such as depression,37, 38 which is also related to physical symptoms and functional status in patients with heart failure.39 In addition, previous studies have shown that depression is negatively related to QOL.8, 40, 41 Therefore, clinicians and researchers should assess patients’ physical and emotional symptoms and their impact on patients’ daily lives. Several instruments can be used to assess heart failure symptoms. The Dyspnea-Fatigue Index is a simple instrument with 4 items measuring dyspnea and fatigue and their impact on patients’ daily activities.42 The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Heart Failure also can be used to assess the frequency and severity of various heart failure symptoms and their impact on patients’ daily lives.10 The Beck Depression Inventory II or the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 can be used to assess depressive symptoms.43-45 Clinicians should provide interventions based on symptom assessment to improve symptom status and QOL. Home-based disease management programs or multidisciplinary education and consultation programs may improve physical and emotional symptoms, functional status, and QOL. 46, 47 48

Patients in the current study reported that heart failure negatively influenced their financial status due to loss of their jobs or increase in medical expenses, and that their financial difficulties negatively affected their QOL. This finding is consistent with the result of a prior study of patients with left ventricular dysfunction.49 Low income was also related to high hospitalization rates in patients with heart failure.50 Thus, further studies are needed to develop and provide effective support for those who have financial difficulties.

Other factors such as positive psychosocial and spiritual well-being and engagemetn in self-care behaviors positively affected patients’ QOL. Many patients mentioned the positive impact of having a positive perspective or outlook, spirituality, self-care behaviors, social support and activities on their QOL. Despite worsening heart failure symptoms, patients tried to keep positive attitudes because they believed that it helped maintain their QOL. However, the impact of positive mood and outlook on QOL and other clinical outcomes has not been examined in heart failure. Patients reported that their faith in God and praying also positively affected their QOL. Even though the mortality rate of patients with heart failure is high,51 patients’ spiritual needs and the impact of spirituality on their QOL has not been examined extensively in heart failure. Among cancer patients, spirituality is associated with QOL.52-57 In one study of patients with heart failure,58 spirituality explained 24% of the variance in global QOL. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine spirituality and its impact on QOL in patients with heart failure.

Patients also observed that self-care behaviors might improve their QOL. Adherence to treatment regimens is associated with QOL in patients with heart failure and those who received heart transplantation.59, 60 Self-care behaviors may impact QOL when they affect symptom status. 10, 16, 61. Further studies are needed to determine the magnitude of the separate and combined impact of each self-care behavior such as eating low sodium and low fat diet, taking medication as prescribed, and symptom management on symptom status and in turn QOL.

Patients perceived that social support such as role replacement and providing information and suitable environments for self-care were important for good QOL. Many patients with heart failure are elderly, live alone and without a spouse,11, 62, 63 have impaired cognitive function,64 and multiple comorbidities.65 Furthermore, they have to follow complicated treatment regimens related to diet, medication, exercise, and symptom management.66 The need to adherence to treatment regimens can produce dramatic changes in lifestyle.67 Nonadherence can result in worsening of heart failure symptoms, which is an important factor affecting QOL.59, 68 Therefore, self-care should be improved in patients with heart failure. For appropriate self-care, patients need social support. The impact on social support on self-care and QOL in heart failure has not been fully examined. In one study,69 baseline social support did not predict 12-month QOL, but the change in social support predicted the change in QOL among patients with heart failure. Therefore, further studies are needed to examine the impact of social supports on self-care and QOL.

Patients’ self-evaluation of their QOL was at times contrary to their own definitions of QOL. For example, having the ability to perform physical and social activities was an important component of patients’ definitions of QOL, and almost all patients reported that they experienced limitations in physical and social activities since developing heart failure. However, about half of the patients reported that their QOL was good. This contradiction reflected the important role of positive outlook and changing personal expectation on these patients’ self-evaluations of their QOL. Patients often evaluated their QOL positively based on how bad things could be instead of how things actually were due to HF; and what they were able to do as opposed to what they were unable to do due to HF. This finding raises the issue of how to appropriately assess QOL in patients with heart failure. Should QOL be based on the objective criteria related to their symptoms, access to support, and functional status, or should it be based on the patients’ subjective valuation of their QOL, or some combination of both.

The Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire is the most commonly used disease-specific instrument to measure QOL in heart failure, while the Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 is the most commonly used generic QOL instrument. Neither instrument reflects the impact of positive psychological aspect of QOL or includes measurement of factors that improve QOL.31, 32 However, patients subjective evaluation of QOL included both factors that enhanced QOL, as well as factors that had a negative impact on QOL. Therefore, clinicians and researchers should examine which measurements are better suited for assessing QOL among patients with heart failure patients: measures assessing only the negative impact of clinical condition and treatment on patients’ daily lives versus measures reflecting positive and negative aspects of QOL and assessing the impact of positive and negative factors on QOL. A clarification of this measurement issue in patients with heart failure could provide more accurate reflections of patients’ actual QOL and improve the knowledge of how QOL is related to other clinical outcomes such as rehospitalization and mortality rates.

Conclusion

Quality of life is a multidimensional, subjective concept that is affected by a variety of factors. Patients’ definition of QOL not only reflected heart failure symptoms and limitations in their daily life due to the symptoms, but also their active pursuit of happiness and relationships with others. Patients’ QOL was affected not only by negative physical, psychological, social, and economic status, but also by positive physical, psychological, and social status, and behaviors. Patents’ self-evaluation of QOL reflected their adopted perception to their changed clinical condition and their positive outlook.

Figure 1.

Quality of life and its correlates in patients with heart failure

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study from an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship to Seongkum Heo and NIH, NINR R01 NR009280 to Terry Lennie.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lewis EF, Johnson PA, Johnson W, Collins C, Griffin L, Stevenson LW. Preferences for quality of life or survival expressed by patients with heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001 Sep;20(9):1016–1024. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, Haunstetter A, Zugck C, Herzog W, Haass M. Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: Comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart. 2002 Mar;87(3):235–241. doi: 10.1136/heart.87.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Jaarsveld CH, Sanderman R, Miedema I, Ranchor AV, Kempen GI. Changes in health-related quality of life in older patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure: A prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Aug;49(8):1052–1058. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dixon T, Lim LL, Oldridge NB. The MacNew heart disease health-related quality of life instrument: Reference data for users. Qual Life Res. 2002 Mar;11(2):173–183. doi: 10.1023/a:1015005109731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riedinger MS, Dracup KA, Brecht ML. Quality of life in women with heart failure, normative groups, and patients with other chronic conditions. Am J Crit Care. 2002 May;11(3):211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C, Pifarre R, Kirklin JK, Bourge RC, Costanzo MR. Predictors of quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure awaiting transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995 Jan-Feb;14(1 Pt 1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westlake C, Dracup K, Creaser J, Livingston N, Heywood JT, Huiskes BL, Fonarow G, Hamilton M. Correlates of health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2002 Mar-Apr;31(2):85–93. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2002.122839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dracup K, Walden JA, Stevenson LW, Brecht ML. Quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1992 Mar-Apr;11(2 Pt 1):273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nordgren L, Sorensen S. Symptoms experienced in the last six months of life in patients with end-stage heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003 Sep;2(3):213–217. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambroski CH, Moser DK, Bhat G, Ziegler C. Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005 Sep;4(3):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaccarino V, Kasl SV, Abramson J, Krumholz HM. Depressive symptoms and risk of functional decline and death in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001 Jul;38(1):199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson JR, Hanamanthu S, Chomsky DB, Davis SF. Relationship between exertional symptoms and functional capacity in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999 Jun;33(7):1943–1947. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riedinger MS, Dracup KA, Brecht ML. Predictors of quality of life in women with heart failure. SOLVD Investigators. Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000 Jun;19(6):598–608. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(00)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayou R, Blackwood R, Bryant B, Garnham J. Cardiac failure: Symptoms and functional status. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35(45):399–407. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90035-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd KJ, Murray SA, Kendall M, Worth A, Frederick Benton T, Clausen H. Living with advanced heart failure: a prospective, community based study of patients and their carers. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004 Aug;6(5):585–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rector TS, Anand IS, Cohn JN. Relationships between clinical assessments and patients’ perceptions of the effects of heart failure on their quality of life. J Card Fail. 2006 Mar;12(2):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alla F, Briancon S, Guillemin F, Juilliere Y, Mertes PM, Villemot JP, Zannad F. Self-rating of quality of life provides additional prognostic information in heart failure. Insights into the EPICAL study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2002 Jun;4(3):337–343. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(02)00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konstam V, Salem D, Pouleur H, Kostis J, Gorkin L, Shumaker S, Mottard I, Woods P, Konstam MA, Yusuf S. Baseline quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization in 5,025 patients with congestive heart failure. SOLVD Investigations. Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction Investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Oct 15;78(8):890–895. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorkin L, Norvell NK, Rosen RC, Charles E, Shumaker SA, McIntyre KM, Capone RJ, Kostis J, Niaura R, Woods P, et al. Assessment of quality of life as observed from the baseline data of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trial quality-of-life substudy. Am J Cardiol. 1993 May 1;71(12):1069–1073. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90575-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riegel B, Moser DK, Glaser D, Carlson B, Deaton C, Armola R, Sethares K, Shively M, Evangelista L, Albert N. The Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire: Sensitivity to differences and responsiveness to intervention intensity in a clinical population. Nurs Res. 2002 Jul-Aug;51(4):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark DO, Tu W, Weiner M, Murray MD. Correlates of health-related quality of life among lower-income, urban adults with congestive heart failure. Heart Lung. 2003 Nov-Dec;32(6):391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott LD. Caregiving and care receiving among a technologically dependent heart failure population. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2000 Dec;23(2):82–97. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majani G, Pierobon A, Giardini A, Callegari S, Opasich C, Cobelli F, Tavazzi L. Relationship between psychological profile and cardiological variables in chronic heart failure. The role of patient subjectivity. Eur Heart J. 1999 Nov;20(21):1579–1586. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sneed NV, Paul S, Michel Y, Vanbakel A, Hendrix G. Evaluation of 3 quality of life measurement tools in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001 Sep-Oct;30(5):332–340. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.118303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connelly JE, Philbrick JT, Smith GR, Jr, Kaiser DL, Wymer A. Health perceptions of primary care patients and the influence on health care utilization. Med Care. 1989 Mar;27(3 Suppl):S99–109. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigioni F, Carigi S, Grandi S, Potena L, Coccolo F, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Magnani G, Tossani E, Musuraca AC, Magelli C, Branzi A. Distance between patients’ subjective perceptions and objectively evaluated disease severity in chronic heart failure. Psychother Psychosom. 2003 May-Jun;72(3):166–170. doi: 10.1159/000069734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riegel B, Moser DK, Carlson B, Deaton C, Armola R, Sethares K, Shively M, Evangelista L, Albert N. Gender differences in quality of life are minimal in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2003 Feb;9(1):42–48. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2003.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosworth HB, Steinhauser KE, Orr M, Lindquist JH, Grambow SC, Oddone EZ. Congestive heart failure patients’ perceptions of quality of life: the integration of physical and psychosocial factors. Aging Ment Health. 2004 Jan;8(1):83–91. doi: 10.1080/13607860310001613374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lainscak M, Keber I. Patient’s view of heart failure: From the understanding to the quality of life. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003 Dec;2(4):275–281. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schiff GD, Fung S, Speroff T, McNutt RA. Decompensated heart failure: Symptoms, patterns of onset, and contributing factors. Am J Med. 2003 Jun 1;114(8):625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rector TS, Cohn JN. Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire: Reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pimobendan. Pimobendan Multicenter Research Group. Am Heart J. 1992 Oct;124(4):1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90986-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992 Jun;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Chung ML. Gender differences in the effects of physical and emotional symptoms on health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111(4):E-59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parshall MB, Welsh JD, Brockopp DY, Heiser RM, Schooler MP, Cassidy KB. Dyspnea duration, distress, and intensity in emergency department visits for heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001 Jan-Feb;30(1):47–56. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.112492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman MM. Older adults’ symptoms and their duration before hospitalization for heart failure. Heart Lung. 1997 May-Jun;26(3):169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekman I, Cleland JG, Swedberg K, Charlesworth A, Metra M, Poole-Wilson PA. Symptoms in patients with heart failure are prognostic predictors: insights from COMET. J Card Fail. 2005 May;11(4):288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, Blazing MA, Davenport C, Califf RM, Krishnan RR, O’Connor CM. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Aug 13-27;161(15):1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Westlake C, Dracup K, Fonarow G, Hamilton M. Depression in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2005 Feb;11(1):30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman MM, Griffin JA. Relationship of physical symptoms and physical functioning to depression in patients with heart failure. Heart Lung. 2001 Mar-Apr;30(2):98–104. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.114180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carels RA. The association between disease severity, functional status, depression and daily quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Qual Life Res. 2004 Feb;13(1):63–72. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000015301.58054.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lane D, Carroll D, Ring C, Beevers DG, Lip GY. Effects of depression and anxiety on mortality and quality-of-life 4 months after myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 2000 Oct;49(4):229–238. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feinstein AR, Fisher MB, Pigeon JG. Changes in dyspnea-fatigue ratings as indicators of quality of life in the treatment of congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1989 Jul 1;64(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90652-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McManus D, Pipkin SS, Whooley MA. Screening for depression in patients with coronary heart disease (data from the Heart and Soul Study) Am J Cardiol. 2005 Oct 15;96(8):1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996 Dec;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Todero CM, LaFramboise LM, Zimmerman LM. Symptom status and quality-of-life outcomes of home-based disease management program for heart failure patients. Outcomes Manag. 2002 Oct-Dec;6(4):161–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.West JA, Miller NH, Parker KM, Senneca D, Ghandour G, Clark M, Greenwald G, Heller RS, Fowler MB, DeBusk RF. A comprehensive management system for heart failure improves clinical outcomes and reduces medical resource utilization. Am J Cardiol. 1997 Jan 1;79(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00676-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holst DP, Kaye D, Richardson M, Krum H, Prior D, Aggarwal A, Wolfe R, Bergin P. Improved outcomes from a comprehensive management system for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001 Oct;3(5):619–625. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosen RC, Contrada RJ, Gorkin L, Kostis JB. Determinants of perceived health in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: a structural modeling analysis. Psychosom Med. 1997 Mar-Apr;59(2):193–200. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Philbin EF, Dec GW, Jenkins PL, DiSalvo TG. Socioeconomic status as an independent risk factor for hospital readmission for heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2001 Jun 15;87(12):1367–1371. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Hole DJ, Capewell S, McMurray JJ. More ‘malignant’ than cancer? Five-year survival following a first admission for heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001 Jun;3(3):315–322. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(00)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romero C, Friedman LC, Kalidas M, Elledge R, Chang J, Liscum KR. Self-forgiveness, spirituality, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. J Behav Med. 2006 Feb;29(1):29–36. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med Winter. 2002;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cotton SP, Levine EG, Fitzpatrick CM, Dold KH, Targ E. Exploring the relationships among spiritual well-being, quality of life, and psychological adjustment in women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 1999 Sep-Oct;8(5):429–438. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<429::aid-pon420>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wan GJ, Counte MA, Cella DF, Hernandez L, McGuire DB, Deasay S, Shiomoto G, Hahn EA. The impact of socio-cultural and clinical factors on health-related quality of life reports among Hispanic and African-American cancer patients. J Outcome Meas. 1999;3(3):200–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Canada AL, Parker PA, de Moor JS, Basen-Engquist K, Ramondetta LM, Cohen L. Active coping mediates the association between religion/spirituality and quality of life in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006 Apr;101(1):102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laubmeier KK, Zakowski SG, Bair JP. The role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment to cancer: a test of the transactional model of stress and coping. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11(1):48–55. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beery TA, Baas LS, Fowler C, Allen G. Spirituality in persons with heart failure. J Holist Nurs. 2002 Mar;20(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/089801010202000102. quiz 26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Abu-Saad HH, Dracup K, Stappers J, van Ree J. Quality of life in older patients with systolic and diastolic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 1999 Jun;1(2):151–160. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(99)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C. Predictors of quality of life in patients at one year after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999 Mar;18(3):202–210. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(98)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Happ MB, Naylor MD, Roe-Prior P. Factors contributing to rehospitalization of elderly patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1997 Jul;11(4):75–84. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krumholz HM, Butler J, Miller J, Vaccarino V, Williams CS, Mendes de Leon CF, Seeman TE, Kasl SV, Berkman LF. Prognostic importance of emotional support for elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Circulation. 1998 Mar 17;97(10):958–964. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.10.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J, Thompson DR. Correlates of psychological distress in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. J Psychosom Res. 2004 Dec;57(6):573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.04.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Riegel B, Bennett JA, Davis A, Carlson B, Montague J, Robin H, Glaser D. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: issues of measurement and etiology. Am J Crit Care. 2002 Nov;11(6):520–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rich MW. Management of heart failure in the elderly. Heart Fail Rev. 2002 Jan;7(1):89–97. doi: 10.1023/a:1013706023974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Executive summary: HFSA 2006 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Card Fail. 2006 Feb;12(1):10–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dracup K, Baker DW, Dunbar SB, Dacey RA, Brooks NH, Johnson JC, Oken C, Massie BM. Management of heart failure. II. Counseling, education, and lifestyle modifications. JAMA. 1994 Nov 9;272(18):1442–1446. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520180066037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bennett SJ, Huster GA, Baker SL, Milgrom LB, Kirchgassner A, Birt J, Pressler ML. Characterization of the precipitants of hospitalization for heart failure decompensation. Am J Crit Care. 1998 May;7(3):168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bennett SJ, Perkins SM, Lane KA, Deer M, Brater DC, Murray MD. Social support and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure patients. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(8):671–682. doi: 10.1023/a:1013815825500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]