Abstract

Delta opioid receptor agonists are under development for a variety of clinical applications, and some findings in rats raise the possibility that agents with this mechanism have abuse liability. The present study assessed the effects of the non-peptidic delta opioid agonist SNC80 in an assay of intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in rats. ICSS was examined at multiple stimulation frequencies to permit generation of frequency-response rate curves and evaluation of curve shifts produced by experimental manipulations. Drug-induced leftward shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves are often interpreted as evidence of abuse liability. However, SNC80 (1.0-10 mg/kg s.c.; 10-56 mg/kg i.p.) failed to alter ICSS frequency-rate curves at doses up to those that produced convulsions in the present study or other effects (e.g. antidepressant effects) in previous studies. For comparison, the monoamine releaser d-amphetamine (0.1-1.0 mg/kg, i.p.) and the kappa agonist U69,593 (0.1-0.56 mg/kg, i.p.) produced dose-dependent leftward and rightward shifts, respectively, in ICSS frequency-rate curves, confirming the sensitivity of the procedure to drug effects. ICSS frequency-rate curves were also shifted by two non-pharmacological manipulations (reductions in stimulus intensity and increases in response requirement). Thus, SNC80 failed to facilitate or attenuate ICSS-maintained responding under conditions in which other pharmacological and non-pharmacological manipulations were effective. These results suggest that non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists have negligible abuse-related effects in rats.

Keywords: delta opioid receptor agonists; SNC80; amphetamine; U69,593; intracranial self-stimulation

1. Introduction

Opioids are thought to act at three major types of opioid receptors, the mu, kappa and delta opioid receptors (Gutstein and Akil, 2005). Effects mediated by delta opioid receptors were initially characterized using peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists such as DPDPE (Hruby and Mosberg, 2004). More recently, non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists have been developed that have high delta receptor efficacy and selectivity and improved bioavailability relative to peptidic compounds (Bishop and McNutt, 2004). For example, the piperazinyl benzamide SNC80 has approximately 500-fold selectivity for delta over mu receptors (Calderon et al., 1994; Bilsky et al., 1995) and previous findings suggest that SNC-induced effects following systemic administration in rodents and non-human primates are mediated by delta opioid receptors (Knapp et al., 1996; Negus et al., 1998; Brandt et al., 2001). Recent preclinical studies have shown that non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists like SNC80 may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of depression (Jutkiewicz and Woods, 2004), pain (Brandt et al., 2001; Ossipov et al., 2004), anxiety (Perrine et al., 2006), cardiac disorders (Gross et al., 2004), and Parkinson's disease (Hille et al., 2001). In view of the development of delta opioid receptor agonists for potential clinical applications, it is important to determine if these agents might have undesirable effects such as abuse-liability.

Research on the abuse-related effects of delta opioid receptor agonists has revealed inconsistent findings. For example, SNC80 and the structurally related delta opioid receptor agonist BW373U86 did not maintain drug self-administration in rhesus monkeys under conditions in which the CNS stimulant cocaine and the mu opioid agonist alfentanil did maintain self-administration (Negus et al., 1994, 1995, 1998). However, both SNC80 and BW373U86 produced conditioned place preferences in rats (Longoni et al., 1998; Morales et al., 2001). Similarly, central (intracerebroventricular, intra ventral tegmental, or intraaccumbal) administration of peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists in rats has been found to maintain self-administration (Devine and Wise, 1994; Goeders et al., 1984), produce place preferences (Shippenberg et al., 1987), and facilitate responding for electrical brain stimulation (Duvauchelle et al., 1996; Duvauchelle et al., 1997). The reasons for these discrepancies are not known, but may involve species differences in the expression, distribution and function of delta receptors (Mansour et al., 1988; Berger et al., 2006), procedural differences in the way experiments have been conducted, and/or pharmacological differences in effects produced by peptidic and non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists.

To further assess the abuse-related effects of non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists, the current study evaluated the effects of systemically administered SNC80 in an assay of intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in rats (Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007). Specifically, rats were implanted with electrodes in the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) of the lateral hypothalamus and trained to respond under a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule for electrical stimulation of constant current intensity but variable frequency. Stimulation of the MFB is thought to activate neural substrates of the limbic system that are also activated by natural rewards such as food, water and sexual behavior, as well as by many drugs of abuse (Wise and Bozarth, 1982; Wise and Rompre, 1989). Moreover, drugs of abuse that produce euphoric states in humans have been shown to facilitate ICSS of the MFB in animals, suggestive of rewarding-like effects (Wise, 1996, 1998). Consequently, ICSS procedures have been widely used to assess the abuse-related effects of drugs (see Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007). Systematic manipulation of the stimulation frequency in the present study permitted generation of ‘frequency-response rate’ curves (similar to pharmacological dose-effect curves) and evaluation of the ability of experimental manipulations to shift these frequency-rate curves (Miliaressis et al., 1986; Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007). An advantage of this “curve-shift” approach in ICSS methodology is that it can be used to dissociate abuse-related effects on sensitivity to stimulation from motor effects on the ability of subjects to respond (Miliaressis et al., 1986). Specifically, lateral shifts in frequency-rate curves are commonly interpreted as evidence for changes in sensitivity to stimulation, whereas vertical shifts are interpreted as evidence for motor effects. In the present study, we hypothesized that if SNC80 has reward-related effects, then it would facilitate ICSS as indicated by leftward shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves.

The effects of SNC80 on ICSS frequency-rate curves were compared with the effects of the monoamine releaser amphetamine and the kappa opioid agonist U69,593. These two drugs have been reported previously to produce leftward and rightward shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves, respectively (Esposito et al, 1980; Schaefer et al., 1988; Todtenkopf et al., 2004; Tomasiewicz et al., 2008). They were evaluated here as controls to confirm the sensitivity of the procedure to drug effects. The effects of two non-pharmacological manipulations were also examined. Reductions in stimulus intensity were evaluated to model selective changes in sensitivity to ICSS in the absence of a change in motor ability. Conversely, increases in fixed-ratio response requirements were tested to model selective changes in motoric ability to meet the response requirement without a change in sensitivity. We predicted that intensity reductions would produce primarily rightward shifts in frequency-rate curves, whereas increases in response requirements would produce primarily downward shifts.

Finally, SNC80 produces convulsant effects in rats (Broom et al., 2002; Jutkiewicz et al., 2006), and since convulsions might contribute to any SNC80-induced changes in ICSS behavior, we evaluated the convulsant effects of SNC80 for comparison with effects on ICSS.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Subjects

Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) weighing 325-375 g at the time of stereotaxic surgery were individually housed with free access to food and water except during testing. Rats were maintained on a 12h light/dark cycle, with lights on from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Animal maintenance and research were in compliance with NIH guidelines on care and use of animal subjects in research, and were approved by the McLean Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. ICSS studies

2.2.1. ICSS electrode implantation

Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (80 mg/kg: 12 mg/kg, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and given subcutaneous (s.c.) atropine sulfate (0.25 mg/kg) to reduce bronchial secretions. Electrodes (monopolar, stainless steel; 0.25 mm in diameter; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were implanted in the left medial forebrain bundle at the level of the lateral hypothalamus (2.8 mm posterior to bregma, 1.7 mm lateral from midsaggital suture, and 7.8 mm below dura; Paxinos and Watson, 1986). The electrodes were coated with polyamide insulation except at the flattened tip. Skull screws (one of which served as the ground) and the electrode were secured to the skull with dental acrylic. The animals were allowed to recover for at least 7 days prior to commencing ICSS training.

2.2.2. ICSS apparatus

Experiments were conducted in modular test chambers made of Plexiglas (20.96 × 30.48 × 24.13 cm) and situated in sound-attenuated boxes (Med Associates Inc., St Albans, VT). The chamber consisted of a stainless steel grid floor and a response lever (4.5 cm wide) extended 2.0 cm through the center of one wall, 2.5 cm off the floor. Electrodes were connected to an ICSS stimulator via a swivel connector. The current stimulator was controlled by a computer software program that also controlled all the programming parameters and data collection (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT).

2.2.3. ICSS procedure

After initial shaping of lever responding, rats were trained on a continuous reinforcement schedule (fixed-ratio 1; FR1) to respond for brain stimulation, using procedures described previously (Carlezon and Wise, 1996, Todtenkopf et al., 2004). Each lever press resulted in the delivery of a 0.5-s train of square wave cathodal pulses (0.1-ms pulse duration), and stimulation was accompanied by the illumination of a 2-W house light. Responses during the 0.5-s stimulation period did not earn additional stimulation. The stimulation intensity for each rat was adjusted gradually to the lowest value that would sustain a reliable rate of responding and this intensity was held stable through the experiment. Daily sessions consisted of up to 9 15-min components. During each component, a descending series of 15 current frequencies (141-28 Hz in 0.05 log increments) was presented, with a 60-s trial at each frequency. A frequency trial was initiated by a 10-s “priming” phase, during which animals received non-contingent stimulation, followed by a 50-s “response” phase during which responding produced electrical stimulation under an FR1 schedule. Test sessions consisted of 9 consecutive components. The first component was considered to be an acclimation component, and data from this component were discarded. Data from the second and third components were used to calculate control parameters of frequency-rate curves for that session (see Data Analysis). Drug and non-drug manipulations were introduced immediately after the third component, and effects were evaluated during components four through nine.

Rats received the following pharmacological treatments: SNC80 (1.0-10 mg/kg, s.c.), SNC80 (10-56 mg/kg, i.p.), amphetamine (0.1-1.0 mg/kg, i.p.), U69,593 (0.1-0.56 mg/kg, i.p.). SNC80 was administered s.c. to parallel the route of administration used in recent studies that described antidepressant effects of SNC80 (Jutkiewicz et al., 2005). Additional studies were conducted using an i.p. route of administration to parallel the routes of administration used for amphetamine and U69,593. The doses of amphetamine and U69,593 were administered in ascending order, and SNC80 doses were administered in random order with at least one week between drug administrations. Saline treatments were administered between each set of drug treatments to ensure that there were no residual drug effects. This type of experimental design is possible because there is substantial evidence in the literature that repeated drug treatments are not associated with alterations in drug sensitivity (tolerance, sensitization; see Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007).

Drug-induced changes in ICSS-maintained responding could result from sensory changes in sensitivity to stimulation and/or from motor changes in the ability of subjects to respond. It has been suggested that sensory and motor effects are differentially manifested as lateral and vertical shifts, respectively, in frequency-rate curves (Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007). To evaluate this proposition and to provide additional data for comparison with SNC80 effects, two non-pharmacological variables were also manipulated. First, to model effects associated with decreased sensory sensitivity, the ICSS stimulus intensity was systematically reduced from the baseline intensity to levels 18, 30 and 56% below the baseline intensity. Second, to model effects associated with decreased motor function, the response requirement was systematically increased from FR1 to FR3 and FR10.

Throughout the study, test sessions were usually conducted on Tuesdays and Fridays. Training sessions were usually conducted on Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays.

2.3. Convulsion Observational Studies

The convulsant effects of SNC80 i.p. administration were assessed under conditions similar to ICSS test experiments. A separate group of rats was administered SNC80 i.p. (10, 32, 56 mg/kg) with at least one week between each drug administration. Following SNC80 administration, rats were placed in individual Plexiglas boxes and observed for convulsant activity for 20 min. Convulsions were measured according to methods described previously (Broom et al., 2000, 2002). Briefly, the convulsions occurred as clonic movements of the head and forepaws and periodically, the entire body. The percentage of rats exhibiting convulsions and the time to onset of convulsions were recorded.

2.4. Histology

Rats that received ICSS electrodes were euthanized with pentobarbital (130 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. The fixed brains were sliced in 40-μm sections for cresyl violet staining to confirm electrode placements.

2.5. Data Analysis

For ICSS studies, the principal dependent variables were Percent Maximum Control Response Rate (% MCR) and the Effective Frequency Maintaining 50% of the Maximum Control Rate (EF50). For each nine-component session, the maximum control rate was defined as the mean of the maximal rates observed during any frequency trial of the second and third components of that session. The response rate during each frequency trial of each component was then expressed as a percentage of the maximum control rate, with %MCR calculated as (Response Rate During a Frequency Trial ÷ Maximum Control Rate) × 100. ICSS curves were then constructed for each rat during each component by plotting % MCR as a function of log frequency. The EF50 for each ICSS curve was defined as the log frequency that maintained 50% of the maximum control rate, and EF50 values were calculated by interpolation from the linear portion of each ICSS curve. Effects of drug and non-drug manipulations on ICSS curves were expressed as ΔEF50 (a measure of left or right lateral shifts in ICSS curves). The ΔEF50 was calculated as Experimental EF50 - Control EF50, with the Control EF50 defined as the mean of the EF50's obtained during the second and third components of that session, and Experimental EF50 defined as the EF50 obtained during each of the subsequent components. Negative ΔEF50s indicate left shifts in ICSS curves, whereas positive ΔEF50s indicate right shifts in ICSS curves. In addition, the Peak % MCR was determined for each component as the highest %MCR observed during any frequency trial of that component. The Peak %MCR served as a measure of upward or downward vertical shifts in the ICSS curve. ΔEF50 and Peak % MCR values were determined for each rat during each component, and these values were averaged to generate mean values and standard errors. The effects of drug and non-drug conditions were evaluated using one- or two-way ANOVA's as appropriate, and significant ANOVAs were followed by individual means comparisons using Bonferroni's post hoc test. The criterion for significance was set a prior at p<0.05.

In addition to these procedures for statistical analysis of drug effects on ICSS curves, raw data are also shown as response rates graphed as a function of log frequency for selected control and experimental conditions.

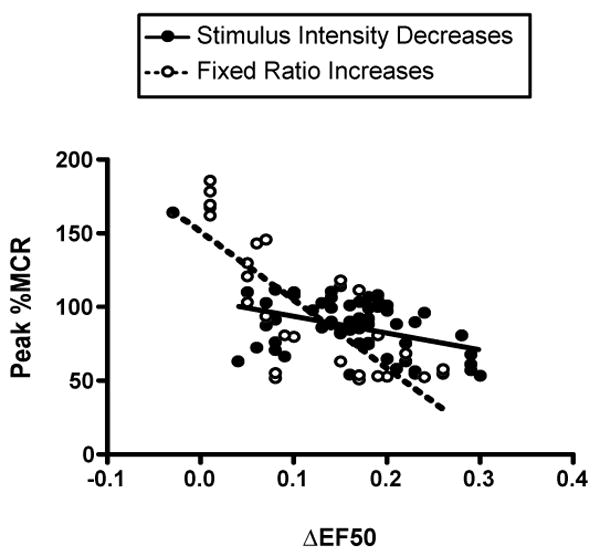

Finally, as noted above, two non-pharmacological manipulations were tested to model changes in sensory sensitivity and motor capability, and it was hypothesized that these two manipulations would produce primarily lateral and vertical shifts, respectively, in ICSS frequency-rate curves. To test this hypothesis, Peak %MCR values (a measure of vertical shifts) were plotted as a function of ΔEF50 values (a measure of lateral shifts) and submitted to linear regression analysis to test for a significant correlation (Prism 4, Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA). Data were plotted for each component in each rat tested with each manipulation. Thus, there were 72 possible points for stimulus intensity reductions (4 rats × 6 components per rat × 3 stimulus intensities) and 60 possible points for response requirement increases (5 rats × 6 components per rat × 2 FR values). Data were plotted for all components in which response rates were high enough to permit calculation of EF50 values. The hypothesis predicted that the slope of the regression line would be more shallow for stimulus intensity changes than for response requirement changes (i.e. smaller vertical shifts per unit of lateral shift in ICSS frequency-rate curves).

2.6. Drugs

D-Amphetamine sulfate and U69,593 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Amphetamine was dissolved in 0.9% saline, U69,593 ((+)-(5α,7α,8β)-N-Methyl-N-[7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxaspiro[4.5]dec-8-yl]-benzeneacetamide) was dissolved in 2% lactic acid, and both drugs were injected by the i.p route of administration. SNC80 ((+)-4-[(αR)-α-((2S,5R)-4-allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide; supplied by K. Rice, NIDDK/NIH) was dissolved to a final concentration of 50 mg/ml in 2% lactic acid, and dilutions were made with 0.9% saline to be administered either by the s.c. or i.p. route. Each drug was administered in a volume of 1 ml/kg.

3. Results

3.1. ICSS studies

3.1.1. Baseline patterns of ICSS

Under baseline conditions, there was a monotonic relationship between ICSS frequency and response rate, and illustrative ICSS frequency-rate curves are shown in the lower right panels (panel D) of Figs. 1 and 2. In general, ICSS frequencies of 2.10 to 1.80 log Hz maintained maximal response rates of approximately 100 responses per min. Response rates usually declined as the ICSS frequency was lowered from 1.75 to 1.65 log Hz, and ICSS frequencies below 1.65 log Hz usually failed to maintain responding. Across the study, the average maximal control rate ± S.E.M. was 89 ± 2.25 responses per min. The average ± S.E.M. EF50 was 1.8 ± 0.01 log Hz.

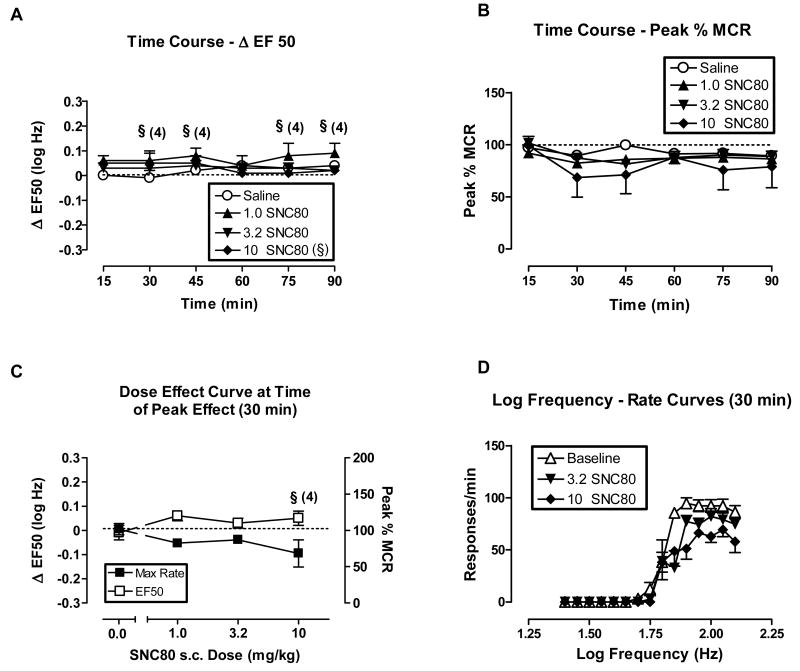

Fig. 1.

Effect of s.c. SNC80 (1.0 - 10 mg/kg) on ICSS in rats. All data points show mean data ± S.E.M. from five rats. (A) Time course of effects on ΔEF50. Abscissa: Time in min after drug injection. Ordinate: ΔEF50 in log Hz. Two-factor ANOVA for ΔEF50 indicated no significant effects of s.c. SNC80 dose [F(2,60)=1.53, P=0.26], time course [F(5,60)=1.01, P=0.18], or the interaction [F(10,60)=1.59, P=0.13]. (B) Time course of effects on Peak % MCR. Abscissa: Time in min after drug injection. Ordinate: Peak % MCR. Two-factor ANOVA for Peak % MCR indicated significant effects of time [F(5,80)=5.0, P=0.0005], but not of s.c. SNC80 dose [F(3,80)= 0.51, P=0.68] or the interaction [F(15,80)=1.28, P=0.24]. (C) Dose-effect curve at time of peak effect (30 min). Abscissa: Dose s.c. SNC80 in mg/kg (log scale). Left ordinate: ΔEF50. Right ordinate: Peak %MCR. One-factor ANOVA revealed no significant effects of SNC80 on ΔEF50 [F(3,15)= 1.06, P=0.40] or on Peak % MCR [F(3,16)=0.87, P=0.48]. (D) Selected log frequency-rate curves. Abscissa: Log frequency of electrical stimulation in Hz. Ordinate: Response rate in responses per min. Curves are shown for representative baseline data and for data collected 30 min after administration of 3.2 and 10 mg/kg SNC80. §Indicates that statistical analyses could not be performed with the 10 mg/kg s.c. SNC80 treatment group.

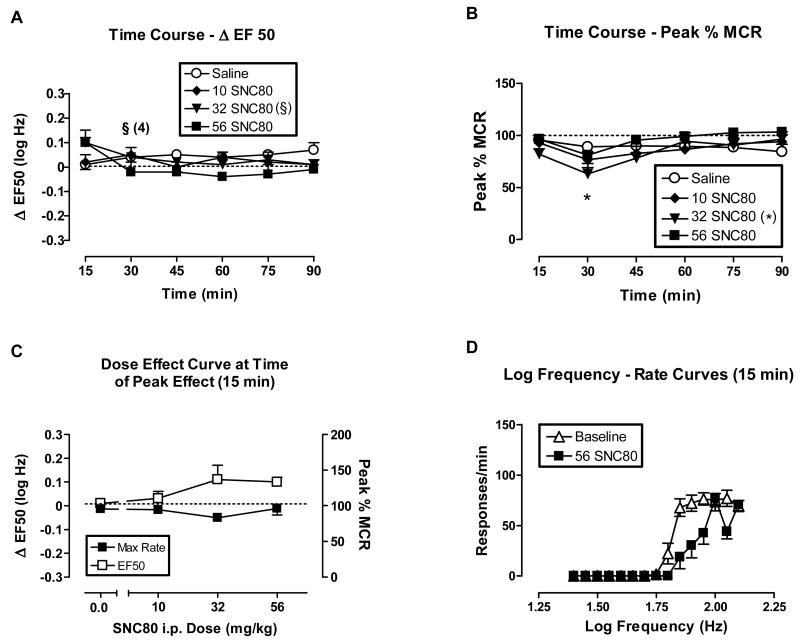

Fig. 2.

The effects of i.p. SNC80 (10-56 mg/kg) on ICSS in rats. All data points show mean data ± S.E.M. from 5 rats per group, except as indicated for 32 mg/kg SNC80. In these cases, the number indicates the number of rats in which EF50 values could be calculated. (A) Time course of effects on ΔEF50. Abscissa: Time in min after drug injection. Ordinate: ΔEF50 in log Hz. Two-factor ANOVA for ΔEF50 indicated significant effects of the interaction between i.p. SNC80 dose (10, 56 mg/kg) and time [F(10,60)=2.58, P=0.01], but no significant main effects of i.p. SNC80 dose [F(2,60)=1.48, P=0.26] or time course [F(5,60)=1.08, P=0.38]. (B) Time course of effects on Peak % MCR. Abscissa: Time in min after drug injection. Ordinate: Peak % MCR. Two-factor ANOVA for Peak % MCR indicated significant effects of time [F(5,80)=6.36, P=0.0001], but not of i.p. SNC80 dose [F(3,80)= 1.15, P=0.36] or the interaction [F(15,80)=1.41, P=0.16]. (C) Dose-effect curve at time of peak effect (15 min). Abscissa: Dose i.p. SNC80 in mg/kg (log scale). Left ordinate: ΔEF50. Right ordinate: Peak %MCR. One-factor ANOVA revealed no significant effects of i.p. SNC80 on ΔEF50 [F(3,16)= 3.1, P=0.06] or on Peak % MCR [F(3,16)=1.96, P=0.16]. (D) Selected log frequency-rate curves. Abscissa: Log frequency of electrical stimulation in Hz. Ordinate: Response rate in responses per min. Curves are shown for representative baseline data and for data collected 15 min after administration of 32 and 56 mg/kg SNC80. *P<0.05, 32 mg/kg i.p. SNC80 compared to saline, Bonferroni's post hoc. §Indicates that statistical analyses on ΔEF50 values could not be performed with the 32 mg/kg i.p. SNC80 treatment group at the 30 min time point.

3.1.2. Effects of SNC80, amphetamine and U69,593 on ICSS

Figs. 1 and 2 show the effects of SNC80 administered s.c. (1-10 mg/kg) and i.p. (10-56 mg/kg), respectively, on ICSS. In these figures, the top panels show the time course of effects on EF50 values (expressed as ΔEF50, top left panels A), and on maximal response rates (expressed as Peak %MCR, top right panels B). The lower panels show curves that relate the experimental manipulation to ΔEF50 or Peak %MCR at the time of peak effect (lower left panels C), and illustrative frequency-rate curves for selected manipulations (lower right panels D). Across the dose ranges tested, SNC80 did not significantly alter EF50 values (figures 1A and 2A). The only significant effect on response rates was a reduction in Peak %MCR 30 min after i.p. administration of 32 mg/kg SNC80, and EF50 values could not be calculated at that time point (Figs 2A and B). In addition, one of five rats did not respond at sufficiently high rates to determine an EF50 value during most of the components after s.c. administration of 10 mg/kg SNC80 (Figs. 1A and B). Visual review of SNC80 dose-effect curves and frequency-rate curves indicates a general trend for SNC80 to increase EF50 values and decrease Peak %MCR values, resulting in slight rightward and downward shifts in frequency-rate curves (Figs. 1C and D, 2C and D). Higher SNC80 doses were not tested via either route of administration due to convulsant and other untoward effects such as lesions at the injection site. Convulsant effects were not formally monitored during ICSS sessions; however, informal observation of a subset of subjects indicated that the highest doses of SNC80 did sometimes produce convulsions during ICSS sessions. The convulsant effects of i.p. SNC80 were evaluated more formally in a separate group of animals as described below. In addition to convulsant effects, the highest dose of s.c. SNC80 produced evidence of irritation and/or necrosis at the injection site, which also precluded the administration of higher s.c. doses. Lastly, it should be noted that this range of s.c. SNC80 did produce antidepressant effects in rats as described previously (Jutkiewicz et al., 2005).

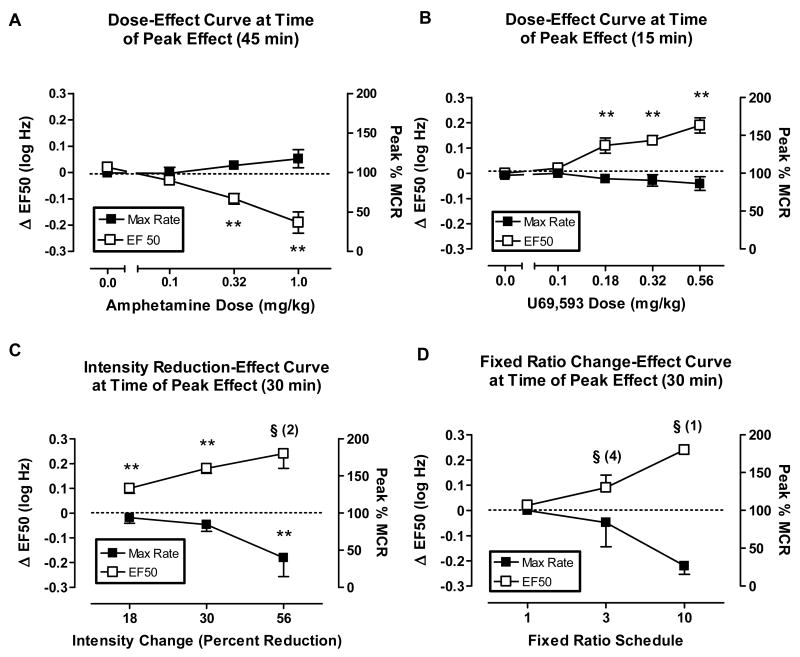

Figs. 3A and 3B show the peak effects of the monoamine releaser amphetamine and the kappa opioid agonist U69,593, respectively. In contrast to SNC80, amphetamine produced left shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves and reductions in EF50 values, whereas U69,593 produced right shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves and increases in EF50 values. For both drugs, significant changes in EF50 values were obtained in the absence of significant changes in Peak %MCR values, although there was a general trend for amphetamine to increase peak rates.

Fig. 3.

Top panels: Amphetamine (0.1-1.0 mg/kg, i.p.) and U69,593 (0.1- 0.56 mg/kg, i.p.) on ICSS at time of peak effect (45 and 30 min, respectively). All data points show mean data ± S.E.M. from 5 rats per group. (A) Abscissa: Dose amphetamine in mg/kg (log scale). One-factor ANOVA revealed significant effects of amphetamine on ΔEF50 [F(3,16)= 14.19, P<0.0001], but not on Peak % MCR [F(3,16)=1.30, P=0.31]. #P<0.05, 0.32 mg/kg amphetamine compared to saline, *P<0.05, 1.0 mg/kg amphetamine compared to saline, **P<0.05, 0.32 and 1.0 mg/kg amphetamine compared with saline; Bonferroni's post hoc. (B) Dose U69,593 in mg/kg (log scale). One-factor ANOVA revealed significant effects of U69,593 on ΔEF50 [F(4,20)= 13.37, P<0.0001] but not on Peak % MCR [F(4,20)=0.68, P=0.61]. **P<0.05, 0.18-0.56 mg/kg U69,593 compared with saline; Bonferroni's post hoc. Bottom panels: Stimulus intensity reductions (18% - 56%) and FR schedule requirement increases (FR3, FR10) on ICSS at time of peak effect (30 min). All data points show mean data ± S.E.M. from 4 rats per group. (C) Abscissa: Stimulus intensity reductions (log scale). One-factor ANOVA revealed significant effects of stimulus intensity reductions (18-30 %) at on ΔEF50 [F(2,9)= 56.19, P<0.0001] and on Peak % MCR [F(3,12)=3.74, P=0.04]. ** P<0.05, data points significantly different from baseline; Bonferroni's post hoc. (D) Abscissa: Fixed Ratio schedule (log scale). The t-test for increases in FR schedule requirements revealed no significant differences between FR1 and FR3 schedule requirement on ΔEF50 values [t=1.70, P=0.19]. One-factor ANOVA revealed no significant effects of increases in FR schedule requirements on Peak % MCR [F(2,12)=3.88, P=0.05]. §Indicates that statistical analyses could not be performed on ΔEF50 values the 56 % stimulus intensity reduction group (Panel C) and with the FR10 group (Panel D).

3.1.3. Effects of non-drug manipulations on ICSS

Figs. 3C and 3D show the effects of reducing the stimulus intensity and of increasing the response requirement, respectively. Reductions in stimulus intensity (18, 30 and 56%) produced sustained intensity-dependent rightward shifts in frequency-rate curves and increases in EF50 values (data not shown). The 18 and 30% stimulus intensity reductions significantly increased EF50 values without changes in maximal response rates (Fig. 3C), whereas reducing the stimulus intensity by 56% significantly decreased Peak %MCR.

The primary effect of response requirement increases was to decrease Peak %MCR (Fig. 3D). When the response requirement was increased to FR3, one of five rats failed to respond at sufficiently high rates to determine an EF50 value, and there was little effect on either EF50 or Peak %MCR in the remaining subjects. The FR10 response requirement produced a significant decrease in Peak %MCR for the group, and EF50 values could not be determined in four of the five rats. In the remaining subject, Peak %MCR was decreased and EF50 was increased.

To provide a more quantitative assessment of effects produced by non-pharmacological manipulations, Fig. 4 shows the relationship between lateral shifts (ΔEF50) and vertical shifts (Peak %MCR) in ICSS frequency-rate curves produced by stimulus-intensity and response-requirement manipulations. For both manipulations, there was a significant, negative correlation between ΔEF50 and Peak %MCR, indicating that rightward shifts in frequency-rate curves were correlated with decreases in maximal response rates. However, the slope of this regression was significantly more shallow for stimulus intensity manipulations than for increases in response requirement. Moreover, there was a lower attrition of data due to low response rates for stimulus intensity reductions, and virtually all of this attrition occurred due to low response rates at the greatest stimulus intensity reduction (-56%). Taken together, these findings support the proposition that stimulus intensity reductions produce primarily lateral shifts in frequency-rate curves, whereas response requirement manipulations produced primarily vertical shifts.

Fig. 4.

Correlation of vertical and lateral shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves produced by stimulus intensity reductions and response requirement increases. Abscissa: ΔEF50 (a measure of lateral shifts). Ordinate: Peak %MCR (a measure of vertical shifts). Data were plotted for each component in each rat for each manipulation in which response rates were high enough to permit calculation of an EF50 (i.e. Peak %MCR ≥50%). By this criterion, 60 of 72 possible points (83.3%) were plotted for stimulus intensity reductions, and 29 of 60 possible points (48.3%) were plotted for response requirement increases. For stimulus intensity reductions, 11 of the 12 data exclusions reflected an elimination of responding produced by the greatest stimulus intensity reduction. There was a significant negative correlation between Peak %MCR and ΔEF50 for both stimulus intensity reductions (R2=0.1624, p=0.0014, solid line) and response requirement increases (R2=0.6470, p<0.0001, dotted line). However, the regression line slope was significantly more shallow for stimulus intensity reductions than for response requirement increases [slope (95%CL) = -113.7 (-181.6 to -45.8) and -462.5 (-597.4 to -327.6), respectively).

3.1.4. Histology

Histological analyses of rat brain sections confirmed that ICSS electrode tips were inserted in the left medial forebrain bundle at the level of the lateral hypothalamus (data not shown). The electrode placements were indistinguishable from those depicted previously (Carlezon et al., 2001; Todtenkopf et al., 2004; Mague et al., 2005).

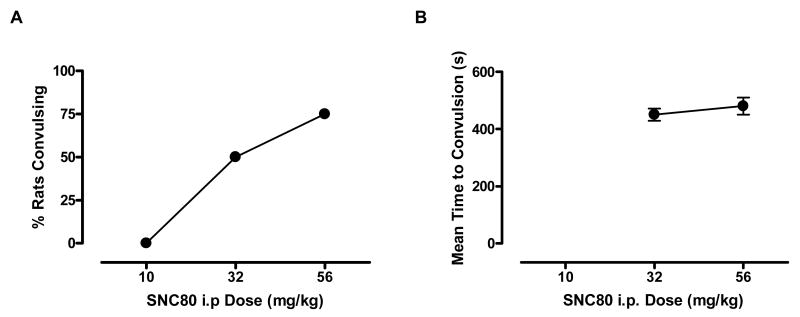

3.2. Convulsant effects of i.p. SNC80

As noted above, convulsions were informally observed in some ICSS animals after administration of the highest doses of s.c and i.p. SNC80. To provide a more formal assessment of SNC80-induced convulsions, the convulsant effects of i.p. SNC80 were evaluated in a separate group of rats. I.p. SNC80 (32 and 56 mg/kg) produced dose-dependent convulsant effects (Fig. 5A) that lasted throughout the 20 min test session (data not shown). There was no difference in the latency to convulsions with increasing doses of SNC80 i.p. [t=1.41, P=0.3], and both doses induced convulsive activity at approximately 7-9 min post-drug administration (Fig 5B). No other adverse behavioral effects were observed following SNC80 administration in these animals.

Fig. 5.

Effects of SNC80 (10-56, i.p.) on convulsions in rats in 4 rats per group. Abscissa: Dose SNC80 in mg/kg (log scale). Ordinate (Panel A): Percent rats convulsing during the 20 min test session. Ordinate (Panel B): Mean time to convulsion in sec. Error bars in the right panel show S.E.M.

4. Discussion

The present findings are the first to evaluate the effects of a non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonist on ICSS in rats. The major findings indicate that the selective and high-efficacy delta opioid receptor agonist SNC80 did not significantly shift ICSS frequency-rate curves, whereas the monoamine releaser amphetamine and the kappa agonist U69,593 produced characteristic left and right shifts, respectively, in ICSS frequency-rate curves. In the present study, ICSS was also sensitive to two non-pharmacological manipulations. Specifically, reductions in the stimulus intensity primarily produced rightward shifts in frequency-rate curves, whereas increases in response requirements primarily produced downward shifts in frequency-rate curves. Taken together, these findings suggest that SNC80 does not alter ICSS under conditions that are sensitive to other pharmacological and non-pharmacological manipulations. The failure of SNC80 to facilitate ICSS indicates that SNC80 does not produce abuse-related rewarding effects in this procedure, and this finding could be further interpreted as evidence to suggest that SNC80 has low abuse liability.

The lack of abuse-related effects by SNC80 in this ICSS procedure is consistent with earlier reports from our laboratory showing that SNC80 did not maintain self-administration in non-human primates (Negus et al., 1998; Brandt et al., 1999). Moreover, the present results are consistent with the finding that systemic administration of SNC80 and BW373U86 in rats did not increase extracellular levels of striatal dopamine, a neurochemical effect produced by many drugs of abuse (Longoni et al., 1998). Indeed, higher doses of SNC80 and BW373U86 significantly decreased dopamine levels in the dorso-lateral caudate-putamen (Longoni et al., 1998). However, the study by Longoni et al. (1998) also found that systemic administration of either SNC80 or BW373U86 produced place preferences in a place-conditioning procedure in rats, and conditioned place preferences are thought to reflect environmental context-associated reward and may be suggestive of abuse liability (Tzschentke, 2007). In addition, centrally administered peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists have been found to maintain self-administration (Devine and Wise, 1994; Goeders et al., 1984), produce place preferences (Shippenberg et al., 1987), facilitate ICSS (Duvauchelle et al., 1997), and increase extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens (Spanagel et al., 1990; Longoni et al., 1991). Overall, then there is some inconsistency in the literature regarding the putative abuse-related effects of delta opioid receptor agonists. The reasons for these discrepancies remain to be determined, but the following possibilities can be considered with existing data.

First, it is possible that the present study used insufficient doses of SNC80. However, the range of s.c.doses used in the present study has been sufficient to produce other behavioral effects in rats including increased locomotor activity (Spina et al., 1998), antinociception (Gallantine and Meert, 2005), antidepressant effects (Jutkiewicz et al., 2005) and conditioned place preferences (Longoni et al., 1998). Doses above 10 mg/kg SNC80 s.c. were not administered in the present study due to signs of irritation at the injection site, but higher doses up to 56 mg/kg i.p. were administered. SNC80 administered by an i.p. route of administration also had little effect on ICSS frequency-rate curves, but informal observation of rats during ICSS sessions indicated that at least some rats convulsed after administration of the highest SNC80 doses. This was confirmed in separate experiments showing that i.p. administration of SNC80 produced dose-dependent convulsant effects at doses of 10-56 mg/kg, and as a result, higher doses were not tested. Taken together, these findings suggest that SNC80 was tested across a pharmacologically active dose range via both the s.c. and i.p. routes of administration.

A second possibility is that the ICSS procedure used for these studies was not sufficiently sensitive to detect abuse-related effects of SNC80. Several findings argue against this possibility. Although SNC80 was inactive, the monoamine releaser amphetamine and the kappa opioid agonist U69,593 produced significant leftward- and rightward-shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves, respectively. These effects of amphetamine and U69,593 were similar to those described previously (Gallistel and Karras, 1984; Esposito et al., 1980; Bespalov et al., 1999, Todtenkopf et al., 2004; Tomasiewicz et al., 2008). Thus, the procedure was sufficiently sensitive to register both facilitation of ICSS or attenuation of ICSS produced by other drugs. The procedure was also sensitive to two non-pharmacological manipulations: reductions in stimulus intensity and increases in fixed-ratio response requirement. These results provide further evidence of the procedure's sensitivity to experimental manipulations. The results with non-pharmacological manipulations also provide general support for the proposition that lateral shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves may be produced by changes in sensitivity to the reinforcing effects of electrical stimulus, whereas vertical shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves may be produced by changes in the subjects' motoric ability to meet the response requirement (Carlezon and Chartoff, 2007). Thus, stimulus intensity reductions produced primarily rightward shifts in ICSS frequency-rate curves, although the highest stimulus intensity reduction also reduced maximal rates of responding. Conversely, increases in response requirements had the primary effect of reducing or eliminating responding in an increasing proportion of rats, and any rightward shifts in frequency-rate curves were rarely observed in the absence of vertical shifts.

Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic considerations constitute a third potential explanation for apparent discrepancies in the abuse-related effects of delta opioid receptor agonists. For example, many peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists, although selective at delta opioid receptors, also act at mu opioid receptors under some conditions (He and Lee, 1998; Fraser et al., 2000). BW373U86 also has relatively low selectivity for delta vs. mu receptors, but newer non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists like SNC80 are highly selective for delta opioid receptors (Calderon et al., 1994; Bilsky et al., 1995; Knapp et al., 1996). Route of administration might also be important as a consequence of its impact on drug distribution. Peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists do not distribute well across the blood-brain barrier and have been administered centrally in studies of abuse-related effects, whereas non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists like SNC80 do cross the blood-brain barrier and have been systemically administered in studies of abuse-related effects. Systemically administered non-peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists likely distribute more extensively throughout the CNS and activate a more heterogeneous population of delta opioid receptors than centrally administered peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists. Thus, differential neurochemical and behavioral effects produced by systemically administered non-peptic and centrally administered peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists may reflect an integration of effects mediated by different populations of delta opioid receptors.

Although pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic factors may contribute to differences in effects of non-peptidic and peptidic delta opioid receptor agonists, these factors cannot explain the finding that systemically administered SNC80 produced place preferences in rats (Longoni et al., 1998), but did not facilitate ICSS in rats (present study) or maintain self-administration in non-human primates (Negus et al., 1998). An explanation for this discrepancy awaits further research. However, one clear difference between these procedures is that place conditioning evaluates abuse-related drug effects at a time long after drug administration, when little or no drug remains in the body. Conversely, ICSS and drug self-administration procedures evaluate abuse-related drug effects shortly after drug administration at times when the drug is active. It is possible that SNC80 produces direct effects (e.g. its convulsant effects) that limit expression of its abuse-related effects while drug is present, and abuse-related effects can be revealed only after the direct effects have dissipated.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the systemically active delta opioid receptor agonist SNC80 did not alter ICSS thresholds under conditions that were sensitive to other pharmacological and non-pharmacological manipulations. These findings add to a growing body of evidence to suggest that SNC80 has relatively low abuse potential.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded exclusively from grants R01-DA11460 (SSN) and R01-DA12736 (WC) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH.

The authors would also like to thank Sam McWilliams, Katrina Schrode and David Potter for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Berger B, Rothmaier AK, Wedekind F, Zentner J, Feuerstein TJ, Jackisch R. Presynaptic opioid receptors on noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons in the human as compared to the rat neocortex. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:795–806. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bespalov A, Lebedev A, Panchenko G, Zvartau E. Effects of abused drugs on thresholds and breaking points of intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9:377–383. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(99)00008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilsky EJ, Calderon SN, Wang T, Bernstein RN, Davis P, Hruby VJ, McNutt RW, Rothman RB, Rice KC, Porreca F. SNC 80, a selective, nonpeptidic and systemically active opioid delta agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:359–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop MJ, McNutt R. Benzhydrylpiperazines as nonpeptidic delta opioid receptor ligands. In: Chang KJ, Porreca F, Woods JH, editors. The Delta Receptor. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt MR, Furness MS, Mello NK, Rice KC, Negus SS. Antinociceptive effects of delta-opioid agonists in Rhesus monkeys: effects on chemically induced thermal hypersensitivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:939–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt MR, Furness MS, Rice KC, Fischer BD, Negus SS. Studies of tolerance and dependence with the delta-opioid agonist SNC80 in rhesus monkeys responding under a schedule of food presentation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:629–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt MR, Negus SS, Mello NK, Furness MS, Zhang X, Rice KC. Discriminative stimulus effects of the nonpeptidic delta-opioid agonist SNC80 in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1157–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom DC, Guo L, Coop A, Husbands SM, Lewis JW, Woods JH, Traynor JR. BU48: a novel buprenorphine analog that exhibits delta-opioid-mediated convulsions but not delta-opioid-mediated antinociception in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:1195–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broom DC, Jutkiewicz EM, Folk JE, Traynor JR, Rice KC, Woods JH. Convulsant activity of a non-peptidic delta-opioid receptor agonist is not required for its antidepressant-like effects in Sprague-Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;1641:42–48. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1179-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon SN, Rothman RB, Porreca F, Flippen-Anderson JL, McNutt RW, Xu H, Smith LE, Bilsky EJ, Davis P, Rice KC. Probes for narcotic receptor mediated phenomena. 19. Synthesis of (+)-4-[(alpha R)-alpha-((2S,5R)-4-allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3- methoxybenzyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide (SNC 80): a highly selective, nonpeptide delta opioid receptor agonist. J Med Chem. 1994;37:2125–2128. doi: 10.1021/jm00040a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Chartoff EH. Intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) in rodents to study the neurobiology of motivation. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2987–2995. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Todtenkopf MS, McPhie DL, Pimentel P, Pliakas AM, Stellar JR, Trzcinska M. Repeated exposure to rewarding brain stimulation downregulates GluR1 expression in the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:234–241. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00232-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Wise RA. Microinjections of phencyclidine (PCP) and related drugs into nucleus accumbens shell potentiate medial forebrain bundle brain stimulation reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;128:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s002130050151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine DP, Wise RA. Self-administration of morphine, DAMGO, and DPDPE into the ventral tegmental area of rats. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1978–1984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-01978.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvauchelle CL, Fleming SM, Kornetsky C. Involvement of delta- and mu-opioid receptors in the potentiation of brain-stimulation reward. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;316:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00674-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvauchelle CL, Fleming SM, Kornetsky C. DAMGO and DPDPE facilitation of brain stimulation reward thresholds is blocked by the dopamine antagonist cis-flupenthixol. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1109–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito RU, Perry W, Kornetsky C. Effects of d-amphetamine and naloxone on brain stimulation reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1980;69:187–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00427648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser GL, Pradhan AA, Clarke PB, Wahlestedt C. Supraspinal antinociceptive response to [D-Pen(2,5)]-enkephalin (DPDPE) is pharmacologically distinct from that to other delta-agonists in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:1135–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallantine EL, Meert TF. A comparison of the antinociceptive and adverse effects of the mu-opioid agonist morphine and the delta-opioid agonist SNC80. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;97:39–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_97107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Karras D. Pimozide and amphetamine have opposing effects on the reward summation function. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;20:73–77. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Lane JD, Smith JE. Self-administration of methionine enkephalin into the nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1984;20:451–455. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(84)90284-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross GJ, Fryer RM, Patel HH, Schultz JEJ. Cardioprotection and delta opioid receptors. In: Chang KJ, Porreca F, Woods JH, editors. The Delta Receptor. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 451–466. [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein H, Akil H. Opioid analgesics. In: Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2005. pp. 547–590. [Google Scholar]

- He L, Lee NM. Delta opioid receptor enhancement of mu opioid receptor-induced antinociception in spinal cord. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:1181–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille CJ, Fox SH, Maneuf YP, Crossman AR, Brotchie JM. Antiparkinsonian action of a delta opioid agonist in rodent and primate models of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:189–198. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby V, Mosberg HI. Endogenous peptides for delta opioid receptors and analogues. In: Chang KJ, Porreca F, Woods JH, editors. The Delta Receptor. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 159–174. [Google Scholar]

- Jutkiewicz EM, Baladi MG, Folk JE, Rice KC, Woods JH. Antidepressant-like effects in delta opioid receptor agonists. In: Chang KJ, Porreca F, Woods JH, editors. The Delta Receptor. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 355–372. [Google Scholar]

- Jutkiewicz EM, Rice KC, Traynor JR, Woods JH. Separation of the convulsions and antidepressant-like effects produced by the delta-opioid agonist SNC80 in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;182:588–596. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jutkiewicz EM, Baladi MG, Folk JE, Rice KC, Woods JH. The convulsive and electroencephalographic changes produced by nonpeptidic delta-opioid agonists in rats: comparison with pentylenetetrazol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1337–1348. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.095810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp RJ, Santoro G, De Leon IA, Lee KB, Edsall SA, Waite S, Malatynska E, Varga E, Calderon SN, Rice KC, Rothman RB, Porreca F, Roeske WR, Yamamura HI. Structure-activity relationships for SNC80 and related compounds at cloned human delta and mu opioid receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1284–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longoni R, Cadoni C, Mulas A, Di Chiara G, Spina L. Dopamine-dependent behavioural stimulation by non-peptide delta opioids BW373U86 and SNC 80: 2. Place-preference and brain microdialysis studies in rats. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longoni R, Spina L, Mulas A, Carboni E, Garau L, Melchiorri P, Di Chiara G. (D-Ala2)deltorphin II: D1-dependent stereotypies and stimulation of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1565–1576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01565.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mague SD, Andersen SL, Carlezon WA., Jr Early developmental exposure to methylphenidate reduces cocaine-induced potentiation of brain stimulation reward in rats. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:120–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Khachaturian H, Lewis ME, Akil H, Watson SJ. Anatomy of CNS opioid receptors. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:308–314. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miliaressis E, Rompre PP, Laviolette P, Philippe L, Coulombe D. The curve-shift paradigm in self-stimulation. Physiol Behav. 1986;37:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90388-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales L, Perez-Garcia C, Alguacil LF. Effects of yohimbine on the antinociceptive and place conditioning effects of opioid agonists in rodents. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133:172–178. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Butelman ER, Chang KJ, DeCosta B, Winger G, Woods JH. Behavioral effects of the systemically active delta opioid agonist BW373U86 in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:1025–1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Gatch MB, Mello NK, Zhang X, Rice K. Behavioral effects of the delta-selective opioid agonist SNC80 and related compounds in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:362–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK, Portoghese PS, Lukas SE, Mendelson JH. Role of delta opioid receptors in the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:1245–1256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossipov MH, Lai J, Vanderah TW, Porecca F. The delta receptor subtypes and pain modulation. In: Chang KJ, Porreca F, Woods JH, editors. The Delta Receptor. Marcel Dekker; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 297–329. [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. second. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Perrine SA, Hoshaw BA, Unterwald EM. Delta opioid receptor ligands modulate anxiety-like behaviors in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:864–872. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer GJ, Michael RP. An analysis of the effects of amphetamine on brain self-stimulation behavior. Behav Brain Res. 1988;29:93–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(88)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Bals-Kubik R, Herz A. Motivational properties of opioids: evidence that an activation of delta-receptors mediates reinforcement processes. Brain Res. 1987;436:234–239. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. The effects of opioid peptides on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1734–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina L, Longoni R, Mulas A, Chang KJ, Di Chiara G. Dopamine-dependent behavioural stimulation by non-peptide delta opioids BW373U86 and SNC 80: 1. Locomotion, rearing and stereotypies in intact rats. Behav Pharmacol. 1998;9:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todtenkopf MS, Marcus JF, Portoghese PS, Carlezon WA., Jr Effects of kappa-opioid receptor ligands on intracranial self-stimulation in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;172:463–470. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1680-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasiewicz HC, Todtenkopf MS, Chartoff EH, Cohen BM, Carlezon WA., Jr The kappa-opioid agonist U69,593 blocks cocaine-induced enhancement of brain stimulation reward. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:982–988. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Addictive drugs and brain stimulation reward. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1996;19:319–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.19.030196.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Drug-activation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Bozarth MA. Action of drugs of abuse on brain reward systems: an update with specific attention to opiates. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1982;17:239–243. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(82)90076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA, Rompre PP. Brain dopamine and reward. Annu Rev Psychol. 1989;40:191–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]