1. Abstract

Bipolar disorder (BD) is associated with high rates of suicide attempt and completion. Substance use disorders (SUD) have been identified as potent risk factors for suicidal behavior in BD. However, little is known concerning differences between BD subtypes with regard to SUD as a risk factor for suicidal behavior. We studied previous suicidal behavior in adults with a major depressive episode in context of BD type I (BD-I; N=96) or BD type II (BD-II; N=42), with and without history of SUD. Logistic regressions assessed the association between SUD and suicide attempt history by BD type, and exploratory analyses examined the effects of other clinical characteristics on these relationships. SUD were associated with suicide attempt in BD-I but not BD-II, an effect not attributable to sample size differences. The higher suicide attempt rate associated with alcoholism in BD-I was mostly explained by higher aggression scores, and earlier age of BD onset increased the likelihood that alcohol use disorder would be associated with suicide attempt(s). The higher suicide attempt rate associated with other drug use disorders in BD-I was collectively explained by higher impulsivity, hostility, and aggression scores. The presence of both alcohol and drug use disorders increased odds of a history of suicide attempt in a multiplicative fashion: 97% of BD-I who had both comorbid drug and alcohol use disorders had made a suicide attempt. A critical next question is how to target SUD and aggressive traits for prevention of suicidal behavior in BD-I.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, suicide, risk factors, substance abuse, alcohol

1. Introduction

Frequency of attempted suicide in Bipolar Disorder (BD) is among the highest of any mental disorders, both in the community (Chen & Dilsaver, 1996; Kessler et al., 1999; Szadoczky et al., 2000), and in clinical samples (Balazs et al., 2003; Bottlender et al., 2000; Cassano et al., 1992; Coryell et al., 1987; Endicott et al., 1985; Kupfer et al., 1988; Lester, 1993; Roy, 1993; Serretti et al., 2002). Between 25% and 60% of bipolar patients will attempt suicide during the course of the illness (Chen & Dilsaver, 1996; Goodwin & Jamison, 1990), and BD lifetime suicide completion rates are estimated at 14% to 20% (Axelsson & Lagerkvist-Briggs, 1992; Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Guze & Robins, 1970).

A history of substance use disorders has been linked to suicide attempt risk in BD (Comtois et al., 2004; Dalton et al., 2003; Feinman & Dunner, 1996; Lopez et al., 2001; Potash et al., 2000; Tondo et al., 1999; Weiss et al., 2005). However, little is known about differences between BD-I and BD-II with regard to this suicide attempt risk factor. We therefore examined differences between BD-I and BD-II in associations between substance use disorders and history of suicide attempt. A secondary goal was to evaluate clinical factors modifying identified risk characteristics.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Subjects (N=138) with a BD were recruited from community referrals or advertisements and enrolled in studies at two sites: the New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York (N=120), and the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh (N=18). All subjects gave written informed consent for participation after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained, as approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards. The primary inclusion criterion was a current major depressive episode in context of BD-I (N=96) or BD-II (N=42). We assessed for history of any SUD but did not distinguish between present or past SUD at time of presentation for purposes of this analysis.

2.2 Assessments

A psychiatric history, physical examination, and routine laboratory screening were performed. Diagnoses were made by trained master’s level psychologists or psychiatric nurses using the Structured Clinical Interview I (SCID-I) for DSM IV Axis I disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; First et al., 1997).

The sample was extensively characterized with regard to demographic and clinical characteristics. Axis II conditions were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview II (SCID-II) for Axis II disorders. (American Psychiatric Association, 1987; First et al., 1995) Current depression severity was measured by the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (Hamilton, 1967) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1961). Severity of suicidal ideation was rated for all subjects using the Scale for Suicidal Ideation (SSI) (Beck et al., 1979). The Reasons for Living Inventory was used to assess possible protective factors (Linehan et al., 1983). Lifetime aggression, impulsivity, and hostility were assessed with a modified form of the Brown-Goodwin Aggression History Scale (B-G) (Brown et al., 1979), the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) (Barratt, 1965), and the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (B-D) (Buss & Durkee, 1957), respectively. History of suicide attempts was assessed with the Columbia Suicide History Scale (Oquendo et al., 2003). Overall level of functioning was rated using the Global Assessment Scale. (Endicott et al., 1976) Some of the subjects included in this study have been included in previous analyses (Grunebaum et al., 2006b; Harkavy-Friedman et al., 2006; Oquendo et al., 2004; Oquendo et al., 2000; Sher et al., 2006; Zalsman et al., 2006).

2.3 Statistical Methods

The two BD subtypes were compared in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics, using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for dichotomous variables, α = 0.05.

To study whether associations between SUD and suicide attempt history differed between BD-I and BD-II groups, we performed separate logistic regression analyses with history of alcohol use disorder or drug use disorder as independent variables, diagnosis as cofactor, and attempter status as response variable; and we tested for interactions. As a check for effects of sample bias, the analyses were repeated, including as cofactor the characteristics with different distributions between BD-I and BD-II samples.

Within the diagnostic subgroup in which SUD were associated with history of suicide attempt, we performed additional analyses to ascertain whether the association could be explained in part by other demographic and clinical variables (listed in Table 1). In separate analyses, we compared subjects within one diagnostic group, with and without alcohol or drug use disorders, with regard to each variable, using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U-tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for dichotomous variables. Each SUD-associated factor and its significantly associated variables were then entered into separate logistic regression models, with prior suicide attempter status as outcome variable, and testing for interactions. Continuous covariates were centered.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Bipolar I and Bipolar II Patients

| Demographic Characteristics | Bipolar I Patients (N=96) | Bipolar II Patients (N=42) | Analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | t | df | p | |||||

| Age (years) | 95 | 37.2 (11.2) | 42 | 37.61 (10.3) | −0.19 | 135 | 0.853 | ||||

| Body-mass index | 92 | 27.7 (7.2) | 41 | 26.1 (5.1) | 1.57 | 105.3a | 0.120 | ||||

| Education (years) | 90 | 14.9 (2.7) | 42 | 15.1 (2.5) | −0.59 | 130 | 0.588 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Median | Q. Range | Mean (SD) | Median | Q. Range | z | p | ||||

| Income level (US$1000/yr)b | 84 | 17.4 (17.5) | 14 | 21 | 40 | 25.6(27.7) | 17 | 50 | −0.98 | 0.329 | |

| N | N with characteristic (%) | N | N with characteristic (%) | X2 | df | p | |||||

| Male sex | 96 | 27 (28.1) | 42 | 16 (38.1) | 1.35 | 1 | 0.245 | ||||

| White race | 96 | 56 (58.3) | 41 | 33 (80.5) | 6.20 | 1 | 0.013 | ||||

| Married | 94 | 28 (29.8) | 42 | 14 (33.3) | 0.17 | 1 | 0.679 | ||||

| Clinical Characteristics | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | t | df | p | ||||

| Barratt Impulsivity Scale | 85 | 64.3 (19.5) | 40 | 60.2 (18.5) | 0.85 | 123 | 0.395 | ||||

| Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory | 84 | 41.9 (13.0) | 39 | 39.9 (14.1) | 0.76 | 121 | 0.448 | ||||

| Brown-Goodwin Aggression Scale | 87 | 21.6 (6.9) | 39 | 20.5 (6.6) | 0.90 | 124 | 0.368 | ||||

| Hamilton Depression Scale (17-item) | 90 | 17.4 (6.9) | 42 | 15.5 (8.4) | 1.41 | 130 | 0.162 | ||||

| Beck Depression Inventory | 50 | 25.4 (11.0) | 32 | 25.8 (13.5) | −0.17 | 80 | 0.865 | ||||

| Beck Hopelessness Scale | 85 | 10.8 (5.8) | 41 | 11.8 (5.6) | −0.86 | 124 | 0.390 | ||||

| Age at first episode (any type) | 89 | 17.7 (9.1) | 41 | 19.9 (11.3) | −1.15 | 128 | 0.251 | ||||

| Reasons for Living Inventory | 71 | 153.1 (50.3) | 35 | 151.1 (40.5) | 0.21 | 104 | 0.837 | ||||

| Global Assessment Scale | 86 | 46.8(13.4) | 39 | 52.1 (13.5) | −2.02 | 123 | 0.045 | ||||

| N | Mean (SD) | Median | Q. Range | N | Mean (SD) | Median | Q. Range | z | P | ||

| No of major depressive episodesc | 74 | 9.1 (6.8) | 6.0 | 9 | 33 | 7.1 (6.3) | 5.0 | 9 | −1.65 | 0.098 | |

| Scale of Suicidal Ideation | 74 | 9.9 (10.2) | 5.5 | 20 | 36 | 9.6 (9.80) | 8.0 | 17 | −0.09 | 0.930 | |

| N | N with characteristic (%) | N | N with characteristic (%) | X2 | df | P | |||||

| Cigarette smoker | 90 | 46 (51.1) | 41 | 17 (41.5) | 1.05 | 1 | 0.305 | ||||

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 82 | 36 (43.9) | 39 | 13 (33.3) | 1.23 | 1 | 0.268 | ||||

| History of physical/sexual abused | 88 | 54 (61.4) | 40 | 18 (45.0) | 2.99 | 1 | 0.084 | ||||

| Comorbid anxiety disorder | 96 | 50 (52.1) | 42 | 18 (42.9) | 1.00 | 1 | 0.319 | ||||

These clinical variables were also tested as modulators of substance use disorders on suicide attempt risk in subjects with Bipolar I.

This comparison did not pass Levene’s Test for Equal Variances and so was analyzed under the assumption of non-equal variances, which alters the degrees of freedom (df) term.

For variables with very skewed distributions, the Mann-Whitney test was used;

to reduce inaccuracy, the top category includes 20 or more depressive episodes;

by self-report. Q. Range = Interquartile Range.

3. Results

3.1 Overall comparisons between diagnostic groups

With regard to demographic and clinical characteristics, BD-I differed from BD-II only in a lower percentage of white subjects and a lower GAS score; a trend was seen toward a higher rate of reported physical/sexual abuse in BD-I (see Table 1). Samples at the two sites were not different with regard to diagnosis or attempter status distributions (data not shown).

3.2 Differences between BD-I and BD-II with regard to the association between SUD and suicide attempt history

As expected, both SUD and suicide attempts were frequent in this population (see Table 2). Rates of drug or alcohol use disorder did not differ between BD-I and BD-II samples; nor did numbers of subjects who had attempted suicide. However, logistic regression analyses revealed that in BD-I but not BD-II, a history of either drug or alcohol use disorders was associated with suicide attempt (see Table 3). This result remained significant when race, GAS scores, and reported history of physical/sexual abuse (factors that were or tended to be differently distributed between BD-I and BD-II in our sample), were included in the logistic regression model (data not shown). The lack of association between SUD and suicide attempt in BD-II did not appear to be a function of low statistical power due to small BD-II sample size. This is expressed by low odds ratios for drug or alcohol use and suicide attempt history within BD-II (alcohol use: χ2=0.238, df=1, p=0.626, OR=0.714, 95% CI =0.185 to 2.762; drug use: χ2=0.626, df=1, p=0.429, OR=0.579, 95% CI =0.150 to 2.241). Within BD-I, history of suicide attempt was higher among subjects with SUD compared to those without, whereas within BD-II, the attempt rate was lower in subjects with SUD compared to those without. This difference between the proportion of suicide attempters among those with SUD is significant in BD-I vs BD-II (see Table 2 of summary statistics, No.(%) of Suicide Attempters/SUD Subjects).

Table 2.

Summary of Relationships Between Suicide Attempts, Bipolar Diagnosis, and Substance Use Disorders

| Bipolar I | Bipolar II | χ2 | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.(%) of Suicide Attempters / Total Subjects: | |||||

| 75/96 (78%) | 30/42 (71%) | 0.72 | 1 | 0.396 | |

|

| |||||

| No.(%) with Substance Use Disorder / Total Subjects: | |||||

| + drug use disorder | 42/96 (44%) | 17/42 (41%) | 0.13 | 1 | 0.721 |

| + alcohol use disorder | 47/96 (49%) | 22/42 (52%) | 0.14 | 1 | 0.711 |

| + both drug & alcohol use disorders | 30/96 (31%) | 15/42 (36%) | 0.27 | 1 | 0.607 |

|

| |||||

| No.(%) with Substance Use Disorder / Suicide Attempters: | |||||

| + drug use disorder | 39/75 (52%) | 11/30 (37%) | 2.02 | 1 | 0.155 |

| + alcohol use disorder | 42/75 (56%) | 15/30 (50%) | 0.31 | 1 | 0.666 |

| + both drug & alcohol use disorders | 29/75 (39%) | 9/30 (30%) | 0.70 | 1 | 0.502 |

|

| |||||

| No.(%) of Suicide Attempters / Substance Use Disorder Subjects: | |||||

| + drug use disorder | 39/42 (93%) | 11/17 (65%) | 7.42 | 1 | 0.006 |

| − drug use disorder | 36/54 (67%) | 19/25 (76%) | 0.70 | 1 | 0.402 |

| + alcohol use disorder | 42/47 (89%) | 15/22 (68%) | 4.68 | 1 | 0.031 |

| − alcohol use disorder | 33/49 (67%) | 15/20 (75%) | 0.39 | 1 | 0.531 |

| + both drug & alcohol use disorders | 29/30 (97%) | 9/15 (60%) | 10.24 | 1 | 0.001 |

| − neither drug nor alcohol use | 23/37 (62%) | 15/20 (75%) | 0.96 | 1 | 0.389 |

Significant results are indicated in bold (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Effects of Drug or Alcohol Use Disorders and Bipolar Diagnosis on Likelihood of Suicide Attempt

| Drug Use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p | OR | 95% CI | |

| Bipolar I vs. II | 0.70 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.22 to 1.86 |

| Drug use disorder | 0.69 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 0.15 to 2.24 |

| Bipolar I * drug use disorder | 6.36 | 1 | 0.01 | 11.23 | 1.72 to 73.51 |

|

| |||||

| Alcohol Use | |||||

| χ2 | df | p | OR | 95% CI | |

|

| |||||

| Bipolar I vs. II | 0.39 | 1 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.21 to 2.23 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 0.24 | 1 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.19 to 2.76 |

| Bipolar I * alcohol use disorder | 3.82 | 1 | 0.05 | 5.70 | 1.00 to 32.65 |

3.3 Features of the association between SUD and suicide attempt within BD-I

There was considerable overlap between alcohol and drug use disorders among subjects with BD-I: 31% of subjects had a history of both types of disorders. In separate logistic regression analyses, suicide attempt status was associated with both alcohol use disorder (χ2= 6.23, df=1, p=0.013, OR=4.07, 95% CI = 1.35 to 12.27) and drug use disorder ( χ2= 7.92, df=1, p=0.005, OR=6.5, 95% CI = 1.77 to 23.9). When the contributions of each type of disorder to suicide attempt were examined in a combined model, a larger portion of the odds was explained by drug use disorder (χ2=4.96, df=1, p=0.026, OR=4.70, 95% CI = 1.20 to 18.32) than by alcohol use disorder (χ2 = 2.42, df=1, p=0.120, OR=2.54, 95% CI = 0.78 to 8.23). This model is additive because the interaction term between the two factors was not significant, and thus the predicted combined OR in the situation of both risk factors (drug and alcohol use disorders) is calculated by multiplying the odds ratios (2.54 × 4.70 = 11.9). When a history of both types of SUD was included as the independent variable in logistic regression analysis, the observed OR was 12.6 (χ2 = 11.1, df=1, p=0.001, OR=2.54, 95% CI = 1.61 to 99.07). Among BD-I subjects who had a history of both alcohol and drug use disorders (N=29), 97% had made at least one suicide attempt.

3.4 Exploratory analyses of the effects of other variables on the association between substance use disorders and past suicide attempt in BD-I

As described in detail in Statistical Methods, in order to understand differences between bipolar subtypes in effects of SUD on suicide attempt, we performed analyses within each bipolar subtype, to identify SUD-associated factors. Logistic regression models were then performed with SUD-associated factors as independent variables and prior suicide attempter status as outcome variable, and testing for interactions. The purpose of these analyses was to test whether other factors may have influenced the relationship between SUD and suicide attempt. We note that these analyses are exploratory in nature and serve primarily to suggest future avenues for prospective research.

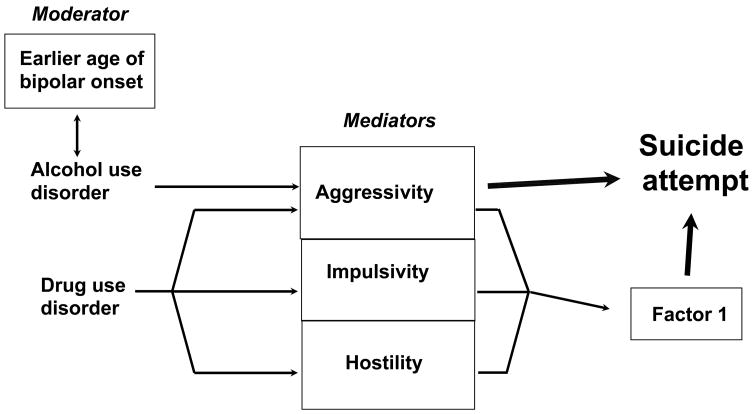

Variables found to be associated with drug use in BD-I were traits of aggressivity, impulsivity and hostility, age of onset of bipolar illness, severity of depression on HDRS, number of major depressive episodes, smoking, and family history of suicidal behavior. Among these variables, we found that the odds ratio for prior suicide attempt in drug use disorder (OR=6.50, 95% CI = 1.76 to 23.93, p=0.005) was significantly affected by only three variables: aggression (reduced OR to 2.78, 95% CI = 0.63 to 12.27, p=0.177); impulsivity (reduced OR to 3.20, 95% CI 0.78 to 13.12, p=0.106); and hostility (reduced OR to 3.67, 95% CI = 0.84 to 16.12, p=0.0858); and there were no interactions. Reduction of the odds ratio indicates that these variables explain a significant portion of the relationship between drug use disorder and prior suicide attempt, and thus might be considered mediators. Given that these variables were highly correlated (aggression-impulsivity, Pearson’s r = 0.461, p<0.001; aggression-hostility, Pearson’s r = 0.593, p<0.001; impulsivity-hostility, Pearson’s r = 0.560, p<0.001), a principal component analysis was conducted, and 3 factors emerged. The first factor, Factor 1, explained 71% of the variance; when Factor 1 was entered into a final logistic regression model together with drug use, the odds ratio for drug use was somewhat reduced (drug use OR=3.84, 95% CI = 0.93 to 15.89, p=0.06). Factor 1 corresponds to the aggression/impulsivity factor previously identified by us, in a larger sample that included subjects with Major Depressive Disorder and BD (N=308), as increasing risk of future suicide attempts. (Oquendo et al., 2004)

Variables associated with alcohol use disorders in BD-I were aggression, earlier age of onset of bipolar illness, smoking, and physical/sexual abuse. Considering these variables, we found that aggression explained a significant portion of the relationship between alcohol use disorders and previous suicide attempt, as the odds ratio for the alcohol use disorder/suicide attempt relationship (OR=4.07, 95% CI = 1.35 to 12.27, p=0.013) lost significance when adjusted for aggression (alcohol use OR=2.26, 95% CI = 0.69 to 7.39, p=0.179), without interactions. Age of bipolar illness onset as an additive factor only slightly modified the odds ratio (reduction of alcohol use OR to 3.21, p=0.068, 95% CI = 0.92 to 11.20), but exhibited a significant interaction with alcohol use disorder (χ2=4.68, df=1, p=0.031, OR=0.81, 95% CI= 0.644 to 1.02), and thus might be a moderator of the relationship between alcohol use disorder and suicide attempts. That is, an earlier bipolar disorder onset—whether depression or mania—further increased the chance that a subject with alcohol use disorder would also have made a suicide attempt(s), but the same was not true for subjects without the alcohol use disorder. To ascertain that the effect of age of onset was not merely a surrogate for how long the subject had been ill, we repeated the analysis with length of illness instead of age of onset as the additive variable; no significant effect was seen on the OR for the alcohol use disorder/suicide attempt relationship nor was any interaction with alcohol use disorder found (data not shown).

3.5 Exploratory analyses of the effects of aggression, suicide attempts, substance use disorders and past suicide attempt in BD-II

In order to better understand the lack of effect of SUD in BD-II, we also performed exploratory analyses concerning the relationships between aggression, suicide attempts, and SUD within that subgroup. We found that although higher aggression was associated with suicidal behavior (t=2.67, df=40, p=0.011) and substance use disorder was associated with higher aggression (alcohol: t=3.48, df=38, p=0.001; drugs: t=2.48, df=38, p=0.018), substance use disorder was not associated with suicidal behavior (alcohol: χ2=0.34, df=1, p=0.558; drugs: χ2=0.76, df=1, p=0.383).

4. Discussion

4.1 Suicide attempt risk and substance use disorders among Bipolar subtypes

The relative risk of suicide attempt and completion between subtypes of BD is unclear. Several studies suggest that Bipolar Disorder Type II (BD-II) has higher potential for suicide attempts (Allilaire et al., 2001; Bulik et al., 1990; Dunner et al., 1976; Goldring & Fieve, 1984; Serretti et al., 2002; Stallone et al., 1980) than other mood disorders. However, others have found no differences between Bipolar Disorder Type I (BD-I) and BD-II in suicide attempt (Coryell et al., 1989; Endicott et al., 1985; Leverich et al., 2003; Slama et al., 2004; Vieta et al., 1997) rates. A couple of reports found more suicide attempts in BD-I than BD-II (Cassano et al., 1992; Coryell et al., 1987). SUD have been found to occur at similar rates in BD-I and BD-II (Tondo et al., 1999; Weiss et al., 2005). In this study, rates of suicide attempts as well as substance use disorders were similar in both BD conditions (see Table 1).

Despite these similarities, SUD emerged as BD-I-specific correlates for suicide attempt. (Tondo et al., 1999; Weiss et al., 2005). The overwhelming majority of our subjects with BD-I with drug (93%), alcohol (89%), or combined substance (97%) use disorders made attempts. If confirmed in larger, prospective studies, this magnitude of effect provides clinically useful knowledge to guide decision making, such as whether to hospitalize a possibly suicidal patient. Obviously these findings merely explain a portion of the risk, as only slightly greater than half the BD I suicide attempters had a drug (52%) or alcohol (56%) use problem, and BD I subjects in this study without substance use disorders also had high rates of suicide attempt (67%).

As evidenced by the parameter estimates, the absence of an effect of substance use disorders on suicide attempt status in BD-II was not due to lack of statistical power resulting from sample size differences. Thus, we reasoned that some additional, BD-I-specific factors appear to be involved in effects of substance use disorders on suicide attempt risk.

4.2 Aggressive-impulsive traits as possible mediators of the association between substance use disorders and suicide attempts in BD-I

We have previously reported on analyses with different objectives that share some subjects with the current study, our findings that bipolar suicide attempters exhibited pronounced aggression (Oquendo et al., 2004; Oquendo et al., 2000), impulsivity (Oquendo et al., 2004), and hostility (Galfalvy et al., 2006); that aggression was associated with past (Zalsman et al., 2006) and subsequent (Sher et al., 2006) suicide attempts; and that SUD in BD have been associated with both impulsive-aggressive traits and number of suicide attempts (Grunebaum et al., 2006a). Other groups have likewise found that aggression was associated with suicidal threats (Papolos et al., 2005) in BD, and that trait impulsivity increased additively in BD comorbid with substance abuse (Swann et al., 2004). In the present analysis, these same traits partly explained the association of prior suicide attempt to SUD, specifically in BD-I. The lack of interactions between SUD and aggressive-impulsive traits suggests that these traits may be partial mediators of the SUD effects on suicide attempt risk (see Figure 1). We thus speculate that the combination of SUD and BD-I symptoms may foster aggression, impulsivity, and hostility that increase the chances of acting on suicidal thoughts. Based on our retrospective data, however, it is not possible to know the temporal relationships between depression, mania, drug use, and suicide attempt. Thus, prospective studies would be needed to determine whether these traits are mediators of SUD effects on suicide attempt. Another difficulty in understanding the precise role of aggression, hostility, and impulsivity in suicide attempts among BD patients is that ‘trait’ and ‘state’ attributes are not always easily separable, as many individuals may spend the majority of their lives at least partially symptomatic (Judd et al., 2002).

Figure 1. Putative Mediators and Moderators of the Impact of Substance Use Disorders on Suicide Attempt in Bipolar I Disorder.

Hypothetical schematic model of relationships between clinical characteristics found to be relevant to history of suicide attempt in Bipolar I Disorder. Factor 1, resulting from a principal component analysis, explains 69% of the variance among the highly correlated variables impulsivity, hostility, and aggressivity.

In BD-II, although SUD was associated with higher aggression, and aggression with suicidal behavior, SUD was not associated with suicidal behavior. Therefore in this diagnostic group, aggression was associated with suicide attempt risk independently of SUD. Our data do not provide a direct explanation for the surprising difference in the association between SUD and suicide attempt between BD-I and BD-II. However, since the cardinal clinical factor distinguishing between the two conditions is the severity of the manic phase, one hypothesis is that excessive use of drugs or alcohol may lead to dysphoric manic or mixed states. Among subjects with BD-I onset prior to development of SUD, the percentage of time with SUD has been associated with the amount of time in mixed episode. (Strakowski et al., 2005) There is previous evidence linking dysphoric mania (Goldberg et al., 1999) and/or mixed states (Balazs et al., 2006; Goldberg & McElroy, 2007) both with substance disorders and with suicidal ideation and violent behaviors. However, our data do not include specific information on mixed or dysphoric manic states, nor on temporal relationship between BD-I or SUD onset.

4.3 Other possible explanations for the association of substance use disorders and suicide attempts in BD-I

Another hypothesis would posit BD-I as a more severe illness overall than BD-II, with more profound effects on a person’s ability to function successfully in school, social, and work environments, although it is unclear how that would lead to an association between SUD and suicide attempt. Psychosocial functioning is a complex outcome measure that has been found to be significantly impaired in both BD-I and BD-II, more intensively studied in the former condition (reviewed in (Huxley & Baldessarini, 2007)). In the 15-year longitudinal National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Depression Study, subjects with BD-I were found to have more functional disability than those with BD-II (Judd et al., 2008). For each level of depression severity, however, BD-I and BII had an equal level of impairment. (Judd et al., 2005) Perhaps related to our hypothesis, manic symptom severity was associated with functional impairment, but in BD-II subjects, hypomanic symptom severity was associated with no impairment or even functional improvement (in the case of subsyndromal hypomania). (Judd et al., 2005) In our sample, we found the global functioning (GAS) to be lower in BD-I group, with, however, no differences between diagnostic groups in other measures of illness severity and/or functioning, including depression severity as measured by HDRS scores, education, income levels, and rates of substance use disorders.

Other mechanisms for the relationship of substance use disorders to suicidality in BD have been proposed. For instance, genetic factors could account for the association: BD, alcoholism, and attempted suicide cluster in some families identified through a BD-I proband (Potash et al., 2000). The increased suicide risk could also arise from additional neurobiological factor(s) that have associations with both substance use disorders and bipolar disorder. For example, abnormal serotonin function has been linked to suicide risk (Mann, 1998), lifetime severity of aggressivity (Placidi et al., 2001), and bipolar disorder (Cannon et al., 2006). In preclinical studies, alcohol consumption has also been linked to abnormal serotonin function (reviewed in (Pettinati et al., 2003)). In a meta-analysis of 17 published studies (3,489 alcoholic and 2,325 non-alcoholic subjects) (Feinn et al., 2005), an association was found between frequency of the short (S) allele of the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) and alcohol dependence; this association was stronger among individuals with alcohol dependence complicated by a co-morbid psychiatric condition. However, at this time it is not known whether there are differences between BD-I and BD-II in the association of altered serotonin function with alcohol dependence.

4.4 Early age of onset as a possible moderator for the association of alcohol use disorders and suicide attempts in BD-I

Our observation in BD-I that earlier age of onset was a correlate of suicide attempt in those with alcohol use disorders agrees with prior findings (Dalton et al., 2003; Feinman & Dunner, 1996; Goodwin & Jamison, 1990; Winokur et al., 1995). Individual reports are confirmed by a meta-analysis of 36 studies (including cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional types), which found that among the main risk factors for attempted suicide were alcohol and/or drug abuse and earlier onset of BD (Hawton et al., 2005). One report suggests that early onset of BD-I and alcoholism may share a common genetic etiology (Lin et al., 2006). Early onset of BD also is related to a more severe course of illness (Birmaher et al., 2006) and may be triggered by physical/sexual abuse (Leverich et al., 2003), which in this analysis showed a trend toward a higher rate in BD-I. The present findings show that the effects of earlier onset of BD illness on the association between alcohol use disorder and suicide attempt history were not mainly due to longer duration of illness. Detrimental sequelae of early BD-I onset could include stunted progress in social, academic, or employment spheres, which, speculatively, in context of the increased impulsivity and risk-taking behaviors and/or abnormal mood might combine to influence an adolescent toward injudicious use of alcohol. This hypothesis is consistent with one study of the relationships between BD age of onset and alcohol use disorders that found early onset of BD predicted synchronicity between bipolar symptom changes and drinking. (Fleck et al., 2006) However, it not possible from this dataset to state whether earlier onset of BD triggered onset of SUD or vice-versa.

4.5 Limitations

One limitation of this study is the retrospective design, including the outcome measure of prior suicide attempt, with no information as to chronologic relationship between substance use, mood episode, and suicide attempts. Additionally, as most subjects were in a current Major Depressive Episode, we may have selected against people who spend more time in a hypomanic or manic state, although our bias is consistent with population morbidity patterns of greater time spent in a depressed state, in both BD-I (Judd et al., 2002) and BD-II (Judd et al., 2003). Finally, this is a referred sample, in which the rates of suicide attempters are high; the findings may not generalize to community samples of BD-I and II.

5. Conclusions

Alcohol and other drug use disorders appear to be particularly salient factors for increasing suicide risk in BD-I, along with aggressive/impulsive traits. Future studies in BD-I should target temporal relationships between illness phase, aggressive behavior, substance use and suicide attempts. Successful clinical management of substance use disorders in BD-I may be critical to reduce the risk of suicidal behavior in this population.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allilaire JF, Hantouche EG, Sechter D, Bourgeois ML, Azorin JM, Lancrenon S, Chatenet-Duchene L, Akiskal HS. [Frequency and clinical aspects of bipolar II disorder in a French multicenter study: EPIDEP] Encephale. 2001;27:149–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed., revised (DSMIII-R) Washington, D.C.: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. (DSMIV) Washington, D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson R, Lagerkvist-Briggs M. Factors predicting suicide in psychotic patients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1992;241:259–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02195974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs J, Benazzi F, Rihmer Z, Rihmer A, Akiskal KK, Akiskal HS. The close link between suicide attempts and mixed (bipolar) depression: implications for suicide prevention. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazs J, Lecrubier Y, Csiszer N, Kosztak J, Bitter I. Prevalence and comorbidity of affective disorders in persons making suicide attempts in Hungary: importance of the first depressive episodes and of bipolar II diagnoses. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;76:113–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt ES. Factor Analysis of Some Psychometric Measures of Impulsiveness and Anxiety. Psychological Reports. 1965;16:547–54. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1965.16.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A. Assessment of suicidal intention: the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:343–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottlender R, Jager M, Strauss A, Moller HJ. Suicidality in bipolar compared to unipolar depressed inpatients. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2000;250:257–61. doi: 10.1007/s004060070016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GL, Goodwin FK, Ballenger JC, Goyer PF, Major LF. Aggression in humans correlates with cerebrospinal fluid amine metabolites. Psychiatry Research. 1979;1:131–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(79)90053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Carpenter LL, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. Features associated with suicide attempts in recurrent major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1990;18:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(90)90114-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss AH, Durkee A. An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1957;21:343–9. doi: 10.1037/h0046900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon DM, Ichise M, Fromm SJ, Nugent AC, Rollis D, Gandhi SK, Klaver JM, Charney DS, Manji HK, Drevets WC. Serotonin transporter binding in bipolar disorder assessed using [11C]DASB and positron emission tomography. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;60:207–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassano GB, Akiskal HS, Savino M, Musetti L, Perugi G. Proposed subtypes of bipolar II and related disorders: with hypomanic episodes (or cyclothymia) and with hyperthymic temperament. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1992;26:127–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Dilsaver SC. Lifetime rates of suicide attempts among subjects with bipolar and unipolar disorders relative to subjects with other Axis I disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 1996;39:896–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, Russo JE, Roy-Byrne P, Ries RK. Clinicians’ assessments of bipolar disorder and substance abuse as predictors of suicidal behavior in acutely hospitalized psychiatric inpatients. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56:757–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Andreasen NC, Endicott J, Keller M. The significance of past mania or hypomania in the course and outcome of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:309–15. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Keller M, Endicott J, Andreasen N, Clayton P, Hirschfeld R. Bipolar II illness: course and outcome over a five-year period. Psychological Medicine. 1989;19:129–41. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700011090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton EJ, Cate-Carter TD, Mundo E, Parikh SV, Kennedy JL. Suicide risk in bipolar patients: the role of co-morbid substance use disorders. Bipolar Disorders. 2003;5:58–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunner DL, Gershon ES, Goodwin FKa. Heritable factors in the severity of affective illness. Biological Psychiatry. 1976;11:31–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Andreasen N, Clayton P, Keller M, Coryell W. Bipolar II. Combine or keep separate? Journal of Affective Disorders. 1985;8:17–28. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinman JA, Dunner DL. The effect of alcohol and substance abuse on the course of bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;37:43–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinn R, Nellissery M, Kranzler HR. Meta-analysis of the association of a functional serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism with alcohol dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;133:79–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Williams J, Spitzer R, Gibbon M. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders (SCID-II, Version 2.0) Part I: Description Journal of Personality Disorders. 1995;9:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck DE, Arndt S, DelBello MP, Strakowski SM. Concurrent tracking of alcohol use and bipolar disorder symptoms. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:338–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galfalvy H, Oquendo MA, Carballo JJ, Sher L, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, Mann JJ. Clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression in bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:586–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Garno JL, Portera L, Leon AC, Kocsis JH, Whiteside JE. Correlates of suicidal ideation in dysphoric mania. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;56:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, McElroy SL. Bipolar mixed episodes: characteristics and comorbidities. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68:e25. doi: 10.4088/jcp.1007e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring N, Fieve RR. Attempted suicide in manic-depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1984;38:373–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1984.38.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin FK, Jamison K. Manic-depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Nichols CM, Caldeira NA, Sher L, Dervic K, Burke AK, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. Aggression and substance abuse in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2006a;8:496–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Ramsay SR, Galfalvy HC, Ellis SP, Burke AK, Sher L, Printz DJ, Kahn DA, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. Correlates of suicide attempt history in bipolar disorder: a stress-diathesis perspective. Bipolar Disorders. 2006b;8:551–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guze SB, Robins E. Suicide and primary affective disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1970;117:437–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.117.539.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1967;6:278–96. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkavy-Friedman JM, Keilp JG, Grunebaum MF, Sher L, Printz D, Burke AK, Mann JJ, Oquendo M. Are BPI and BPII suicide attempters distinct neuropsychologically? Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;94:255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Harriss L. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:693–704. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley N, Baldessarini RJ. Disability and its treatment in bipolar disorder patients. Bipolar Disorders. 2007;9:183–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Coryell W, Endicott J, Maser JD, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Keller MB. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:261–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Leon AC, Solomon DA, Coryell W, Maser JD, Keller MB. Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders: a prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:1322–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, Maser JD, Coryell W, Endicott J, Akiskal HS. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2008;108:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–26. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer DJ, Carpenter LL, Frank E. Is bipolar II a unique disorder? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1988;29:228–36. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(88)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester D. Suicidal behavior in bipolar and unipolar affective disorders: a meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;27:117–21. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90084-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Denicoff KD, Obrocea G, Nolen WA, Kupka R, Walden J, Grunze H, Perez S, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM. Factors associated with suicide attempts in 648 patients with bipolar disorder in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:506–15. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PI, McInnis MG, Potash JB, Willour V, MacKinnon DF, DePaulo JR, Zandi PP. Clinical correlates and familial aggregation of age at onset in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:240–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Nielsen SL, Chiles JA. Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the reasons for living inventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:276–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez P, Mosquera F, de Leon J, Gutierrez M, Ezcurra J, Ramirez F, Gonzalez-Pinto A. Suicide attempts in bipolar patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62:963–6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:25–30. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Galfalvy H, Russo S, Ellis SP, Grunebaum MF, Burke A, Mann JJ. Prospective study of clinical predictors of suicidal acts after a major depressive episode in patients with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1433–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ. Risk factors for suicidal behavior: utility and limitations of research instruments. In: First MB, editor. Standardized Evaluation in Clinical Practice. Washington, D.C.: APPI Press; 2003. pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oquendo MA, Waternaux C, Brodsky B, Parsons B, Haas GL, Malone KM, Mann JJ. Suicidal behavior in bipolar mood disorder: clinical characteristics of attempters and nonattempters. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2000;59:107–17. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papolos D, Hennen J, Cockerham MS. Factors associated with parent-reported suicide threats by children and adolescents with community-diagnosed bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;86:267–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettinati HM, Kranzler HR, Madaras J. The status of serotonin-selective pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 2003;16:247–62. doi: 10.1007/0-306-47939-7_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placidi GP, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Huang YY, Ellis SP, Mann JJ. Aggressivity, suicide attempts, and depression: relationship to cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:783–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash JB, Kane HS, Chiu YF, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, McInnis MG, McMahon FJ, DePaulo JR., Jr Attempted suicide and alcoholism in bipolar disorder: clinical and familial relationships. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:2048–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. Features associated with suicide attempts in depression: a partial replication. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1993;27:35–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serretti A, Mandelli L, Lattuada E, Cusin C, Smeraldi E. Clinical and demographic features of mood disorder subtypes. Psychiatry Research. 2002;112:195–210. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(02)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Carballo JJ, Grunebaum MF, Burke AK, Zalsman G, Huang YY, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. A prospective study of the association of cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels with lethality of suicide attempts in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:543–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slama F, Bellivier F, Henry C, Rousseva A, Etain B, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. Bipolar patients with suicidal behavior: toward the identification of a clinical subgroup. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1035–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallone F, Dunner DL, Ahearn J, Fieve RR. Statistical predictions of suicide in depressives. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1980;21:381–7. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(80)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Anthenelli RM, Keck PE, Jr, Arnold LM, Amicone J. Effects of co-occurring alcohol abuse on the course of bipolar disorder following a first hospitalization for mania. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:851–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Dougherty DM, Pazzaglia PJ, Pham M, Moeller FG. Impulsivity: a link between bipolar disorder and substance abuse. Bipolar Disorders. 2004;6:204–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szadoczky E, Vitrai J, Rihmer Z, Furedi J. Suicide attempts in the Hungarian adult population. Their relation with DIS/DSM-III-R affective and anxiety disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:343–7. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)90501-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, Minnai GP, Salis P, Scamonatti L, Masia M, Ghiani C, Mannu P. Suicide attempts in major affective disorder patients with comorbid substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60 Suppl 2:63–9. discussion 75–6, 113–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Benabarre A, Colom F, Gasto C, Nieto E, Otero A, Vallejo J. Suicidal behavior in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1997;185:407–9. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199706000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RD, Ostacher MJ, Otto MW, Calabrese JR, Fossey M, Wisniewski SR, Bowden CL, Nierenberg AA, Pollack MH, Salloum IM, Simon NM, Thase ME, Sachs GS. Does recovery from substance use disorder matter in patients with bipolar disorder? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:730–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0609. quiz 808–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Keller MB, Endicott J, Mueller T. Alcoholism in manic-depressive (bipolar) illness: familial illness, course of illness, and the primary-secondary distinction. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:365–72. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalsman G, Braun M, Arendt M, Grunebaum MF, Sher L, Burke AK, Brent DA, Chaudhury SR, Mann JJ, Oquendo MA. A comparison of the medical lethality of suicide attempts in bipolar and major depressive disorders. Bipolar Disorders. 2006;8:558–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]