Abstract

Members of the tristetraprolin family of CCCH tandem zinc finger proteins bind to AU-rich elements in certain cellular mRNAs, leading to their deadenylation and destabilization. Studies in knock-out mice demonstrated roles for three of the family members, tristetraprolin, ZFP36L1, and ZFP36L2, in inflammation, chorioallantoic fusion, and early embryonic development, respectively. However, little is known about a recently discovered placenta-specific tristetraprolin family member, ZFP36L3. Tristetraprolin, ZFP36L1, and ZFP36L2 have been shown to shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, using typical hydrophobic amino acid-rich nuclear export sequences, and nuclear localization sequences located within the tandem zinc finger domain. In contrast, we previously showed that green fluorescent protein-labeled ZFP36L3, expressed in HEK 293 cells, remained cytosolic, even in the presence of the nuclear export blocker leptomycin B. We show here that the conserved tandem zinc finger domain contains an active nuclear localization signal. However, the sequence corresponding to the nuclear export signal in the other family members was nonfunctional, and thus did not contribute to the cytosolic localization. The unique C-terminal repeat domain could override the activity of the nuclear localization sequence, preventing the import of ZFP36L3 into the nucleus. Immunostaining of mouse placenta demonstrated that ZFP36L3 was located only in the cytoplasm of trophoblast cells. Thus, in contrast to the other mammalian members of this protein family, ZFP36L3 is a “full-time” cytosolic protein, rather than a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein. The significance of this difference in subcellular localization to the physiology of placental trophoblast cells, where ZFP36L3 is selectively expressed, remains to be determined.

The mammalian members of the tristetraprolin (TTP)2 family of CCCH tandem zinc finger (TZF) proteins include TTP (also known as ZFP36) (1–6), ZFP36L1 (7–11), ZFP36L2 (8, 12, 13), and ZFP36L3 (14). All TTP family members share high percentages of amino acid sequence identity within their TZF domains. This domain contains two independently folding protein motifs, each of which contains three cysteines and one histidine that coordinate a zinc ion. The TZF domain is responsible for high affinity binding to AU-rich elements (ARE), generally found in the 3′-untranslated region of target mRNAs. The binding of the proteins, in turn, promotes deadenylation and destabilization of the targeted mRNAs (15–17) in a still unclear process that appears to involve decapping and nucleolytic decay. Similarities among TTP, ZFP36L1 (L1), and ZFP36L2 (L2) in their RNA binding and destabilizing properties suggest functional overlap among the family members, although the differences in transcriptional regulation and cell-and tissue-specific expression suggest different target mRNAs. Interactions between the CCCH TZF proteins and their mRNA targets may provide an important regulatory control on gene expression at the post-transcriptional level.

ZFP36L3 (L3) was recently discovered as the fourth mammalian member of the TTP family (14). It exhibits a high percentage of sequence similarity to the other three family members within the TZF domain and within the extreme C terminus (14). The TZF domain in this protein also exhibits the distinguishing characteristics of the TTP family as follows: identical intra-finger spacing of the cysteine and histidine residues and exact inter-finger spacing, as well as the presence of the conserved “lead-in” sequences to the zinc fingers. Initial analyses showed that L3 could mimic the RNA binding and destabilizing activities of TTP, L1, and L2. For example, L3 was found to bind a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-based RNA probe in a cell-free system and to promote decay of an ARE-containing RNA target in intact cell transfection experiments (14). Thus, this new family member presumably retains the general biological functions of TTP, L1, and L2, i.e. the ability to down-regulate certain ARE-containing mRNAs; however, this concept remains to be proven in a physiological setting.

A significant biochemical distinction between L3 and its relatives concerns its subcellular localization. L3, which is cytoplasmic at steady state when expressed as a GFP fusion protein in transfected HEK 293 cells, does not appear to shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm (14), whereas the other family members exhibit shuttling activity (18, 19). Like other nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins, TTP, L1, and L2 contain both apparent nuclear localization sequences (NLS), which mediate nuclear import, and functional nuclear export sequences (NES), which facilitate nuclear export (reviewed in Refs. 20–22).

NLSs include motifs rich in basic residues that bind to nuclear import receptors, such as the importins, for transport into the nucleus. The NLSs of TTP, L1, and L2 have been mapped to the inter-finger region of the TZF domain; the import of these proteins into the nucleus requires the TZF domain (18, 19), and two arginines within the inter-finger spacer have been proposed to be critical for this translocation (19). Mouse L3 shows 76% amino acid sequence identity in its TZF domain compared with mouse TTP, and it also retains the conserved arginine residues (14). Therefore, like the other family members, L3 may contain a functional NLS that is able to drive transport of the protein into the nucleus.

The NESs of TTP, L1, and L2 are characterized by hydrophobic regions that bind CRM1, a nuclear membrane export protein that directs transport of proteins from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. The NESs of L1 and L2 are located within their identical C termini and contain a leucine-rich cluster, whereas the NES of TTP is located at its extreme N terminus (18). A potential NES of L3 is also located at the extreme C terminus and, although superficially similar to those of the other family members, contains a significant difference in sequence; the fourth hydrophobic residue characteristic of the NESs of L1 and L2 is, instead, an aspartate residue in L3. This difference may lead to failure of the L3 NES to bind the export receptor CRM1; the NES of L3 could therefore be nonfunctional, because of the lack of a conserved hydrophobic residue that is essential for export.

If L3 contains a functional NLS and a nonfunctional NES, the protein would be expected to be nuclear. However, L3 has been shown to be cytosolic, at least as a GFP-labeled fusion protein in transfection experiments (14). Therefore, an additional factor must contribute to its localization. The molecular weight of L3 is much larger than those of the other family members, with a predicted Mr of 72,345 for the mouse protein. This increase in size is largely because of the existence of a unique repeat domain within the C-terminal half of the protein. This domain contains 10 repeats of the sequence AAMAPGAALAPAAALTPA, or close variants, and is predicted to fold into seven hydrophobic α-helices (14). In theory, this domain could be responsible for targeting L3 to a membrane and therefore could affect the subcellular localization of L3.

In this study we examined the possible cytosolic restriction of L3 by manipulating these predicted localization domains. We addressed the following hypotheses: 1) the TZF domain contains a functional NLS, and the aforementioned arginines are critical for NLS activity; 2) the putative C-terminal NES is nonfunctional; and 3) the unique repeat domain is a cytoplasmic localization domain. We also examined the cellular and subcellular localization of the endogenous L3 protein in the placenta.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

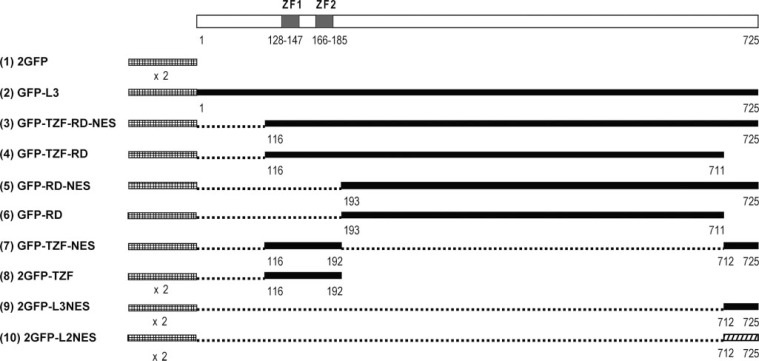

Plasmids—The plasmid pZfp36l3-ORF (14), which contains the open reading frame of mouse Zfp36l3 (GenBank™ accession number AY661338.1), was used as a PCR template for each N-terminal GFP fusion construct. See (Fig. 1) for a schematic illustration of the full-length and deletion L3 plasmid constructs used in this study.

FIGURE 1.

L3 constructs used to characterize the functions and examine the relative contributions of the NLS, NES, and repeat domain. The indicated regions of L3 were cloned into the pcDNA-DEST53 expression vector to generate proteins fused downstream of and in-frame with N-terminal GFPs. Plasmids GFP-L3 (2) and 2GFP-TZF (8) were subjected to site-directed mutagenesis to change critical arginines within the inter-finger domain of the L3 TZF. Plasmids 2GFP (1), 2GFP-TZF (8), 2GFP-L3NES (9), and 2GFP-L2NES (10) were designed to express fusion proteins containing two tandem GFPs that should be too large to diffuse across the nuclear membrane. Each deleted region is shown by a dotted line. GFP, L3, and L2 sequences are represented by cross-hatched, black filled, and diagonal lines, respectively.

Plasmid GFP-L3 was created by PCR amplifying bases 150–2327 of GenBank™ accession number AY661338.1, corresponding to amino acids 1–725 of GenPept accession number AAV74249.1, using the forward primer 5′-ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggctctATGGCCAACAACAATCTG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-ggggaccactttgtacaagaaagctgggtcTCATTTTTCAGAGTCTG-3′, in which the lowercase letters represent recombination sequences for cloning into the Gateway system (Invitrogen). The resulting amplification product was recombined into the pDONR221 entry vector (Invitrogen) and then subsequently recombined into the pcDNA-DEST53 expression vector (Invitrogen). The sequence was confirmed by dRhodamine dye terminator cycle sequencing (Applied Biosystems).

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the plasmid GFP-L3 according to the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene). Arginines 153 and 157 from GenPept accession number AAV74249.1 were mutated to alanines both singly and together using the following primer sets: 5′-GGCTACCGCGAACTGGCTACCCTGTCAAGG-3′ and 5′-CCTTGACAGGGTAGCCAGTTCGCGGTAGCC-3′ for mutation of Arg-153; 5′-CGT-ACCCTGTCAGCGCACCCCAAGTACAAGACG-3′ and 5′-CGTCTTGTACTTGGGGTGCGCTGACAGGGTTACG-3′ for mutation of Arg-157; and 5′-CCGCGAACTGGCTACCCTGTCAGCGCACCCCAAGTACAAGACG-3′ and 5′-CGTCTTGTACTTGGGGTGCGCTGACAGGGTAGCCAGTTCGCGG-3′ for mutation of both simultaneously. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

Plasmids for L3 deletion mutants were constructed by a similar method to that described above for plasmid GFP-L3. The appropriate regions of the L3 cDNA were amplified by PCR, followed by recombination into the entry vector pDONR221, and then into the expression vector pcDNA-DEST53. The sequences were confirmed by dRhodamine dye terminator cycle sequencing.

Plasmid GFP-TZF-RD-NES expresses an N-terminal GFP fused to amino acids 116–725 of GenPept accession number AAV74249.1, corresponding to nucleotides 495–2327 of Gen-Bank™ accession number AY661338.1. Plasmid GFP-TZF-RD expresses GFP fused to amino acids 116–711, corresponding to nucleotides 495–2282. Plasmid GFP-RD-NES expresses GFP fused to amino acids 193–725, corresponding to nucleotides 495–2327. Plasmid GFP-RD expresses GFP fused to amino acids 193–711, corresponding to nucleotides 726–2282. Plasmid 2GFP-TZF expresses two tandem GFP domains fused to amino acids 116–192, corresponding to nucleotides 495–725; site-directed mutagenesis of Arg-153 and Arg-157 was performed on this plasmid as was described for plasmid GFP-L3. Plasmid 2GFP-L3NES expresses two tandem GFP domains fused to amino acids 712–725, corresponding to nucleotides 2283–2327.

A mutant plasmid was also constructed that expresses an N-terminal GFP-GFP fused to the NES of L2. The C-terminal portion of L2, which contains the NES, corresponding to amino acids 471–484 of accession number NP_001001806.1 and nucleotides 1664–1708 of accession number NM_001001806.2, was used in plasmid 2GFP-L2NES. This plasmid expresses only the C-terminal 14 amino acids of L2 downstream of two tandem GFP domains.

Two plasmids containing the simian virus 40 (SV40) large T-antigen NLS were created for comparison of this extensively studied, strong NLS to the putative NLS located in L3 TZF domain. Plasmid 2GFP-SV40NLS expresses two tandem GFP domains fused to the NLS of SV40, corresponding to the nucleotide sequence GATCCAAAAAAGAAGAGAAAGGTA. Plasmid GFP-SV40NLS-RD expresses GFP fused to the NLS of SV40 followed by the repeat domain of L3 (amino acids 193–711 of GenPept accession number AAV74249.1, corresponding to nucleotides 726–2282 of GenBank™ accession number AY661338.1).

pEGFP-N1 (Clontech) and plasmid 2GFP, which express one or two tandem GFP domains, respectively, were used in control experiments. GFP-TIS11D (18) expresses a C-terminal GFP fused to mouse L2 and was utilized as a positive control in nuclear export assays.

All plasmids that express two tandem GFP domains alone or fused to an L3 domain were designed to increase the size of the protein and therefore prevent passive diffusion across the nuclear membrane. All plasmids that express only one GFP domain fused to the L3 repeat domain should also be larger than the nuclear pore and should not undergo passive diffusion into or out of the nucleus.

Cell Culture and Transfections—HEK 293 cells (referred to here as 293 cells) were maintained in minimal essential medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 2 mm glutamine. Transient transfections were performed 24 h after plating with FuGENE 6 transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with a reagent: DNA ratio of 3:1.

Fluorescence Microscopy—1 × 105 cells were plated in 35-mm glass bottom plates (MatTek Corp.) and transfected with 1 μg of DNA for each of the GFP fusion constructs. Live 293 cells expressing GFP fusion proteins were observed, and images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. The patterns of fluorescence shown in the figures are representative of all cells expressing a given fusion protein.

Leptomycin B Treatment—In nucleocytoplasmic shuttling assays, 293 cells were plated and transfected as described above. Leptomycin B (LMB) (Sigma) was added to the medium at a final concentration of 10 ng/ml in 0.18% (final concentration; v/v) methanol 16–20 h after DNA transfection. As a control treatment, an equal volume of the solvent, methanol, was added. Subcellular localization of GFP-labeled proteins was observed 4–5 h later using fluorescence microscopy of live cells.

Analysis of RNA Binding—To prepare protein for RNA binding analysis, 0.7 × 106 293 cells were plated on 100-mm plates and transfected with 1 μg of DNA from the appropriate GFP constructs. After 16–20 h, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed three times with 10 ml of ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, calcium- and magnesium-free (pH 7.4). A volume of 250 μl of ice-cold, freshly made homogenization buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 1× complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)) was added to the cells, which were then scraped and collected. The cells were subsequently incubated on ice for 20 min to complete cell lysis. Centrifugation at 110 × g for 20 min at 4 °C was then performed to remove cell nuclei and debris. Finally, glycerol was added to 15% (v/v).

To check for recombinant protein expression, 50 or 100 μg of protein from this cell lysate was boiled in loading buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 7.5% acrylamide gel, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analysis was performed with either an anti-GFP-HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a dilution of 1:3000 or an anti-GFP antibody (BD Biosciences) at a dilution of 1:2000 followed by a protein-A horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a dilution of 1:4000. Proteins were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Pierce).

RNA gel shift assays were performed as described previously (16, 17). Briefly, 15 μg of total protein from the cell lysate was incubated with a 32P-labeled TNF ARE RNA probe, and the reactions were analyzed on either a 4 or 8% (w/v) nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel followed by autoradiography.

Northern Blotting and Immunoblotting for Endogenous L3—Placentas were collected from pregnant female Crl:CD1(CR) mice3 (Charles River Laboratories) at embryonic days (E) 9.5, E10.5, E12.5, and E14.5. Half of the tissues were placed in RNA-later and were used for total cellular RNA isolation with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To check for L3 transcript expression, 20 μg of RNA from each sample was fractionated on a 1.2% formaldehyde-agarose gel, transferred to a Nytran SuPer Charge membrane, and hybridized with random-primed, α-32P-labeled probes. The probe used for detecting L3 transcripts consisted of nucleotides 150–585 of GenBank™ accession number AY661338.1. The blot was also hybridized with a full-length glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase cDNA probe to monitor gel loading. Hybridization was visualized using autoradiography.

The remaining half of the tissues were rapidly frozen. They were then pulverized in liquid nitrogen; extracts were made in the aforementioned homogenization buffer using a Tissumizer (Tekmar), and the samples were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min. Total protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay. To check for endogenous L3 expression, 100 μg of total protein from each extract was subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 10% acrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analysis was performed with a rabbit antiserum directed against the 16 N-terminal amino acids of mouse L3 (Covance) at a dilution of 1:2000 followed by a protein-A HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a dilution of 1:4000. Proteins were visualized with ECL. The blot was then stripped and reprobed with an anti-actin antibody (Chemicon) at a dilution of 1:10,000 followed by goat anti-mouse HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a dilution of 1:10,000. Immunoreactive proteins were again visualized with ECL.

Immunofluorescence of Placental Sections—Slides of placental sections from B6(Cg)-TyrC-2J/J mice2 (Jackson Laboratory) at E14.5 were stained with either preimmune serum or an anti-L3 antibody each diluted to 1:1000 with 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.9% NaCl, 1% normal goat serum, as described (14, 23). They were then washed two times for 10 min each with 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100 in Tris-buffered saline, incubated with an Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) diluted to 1:300 in Tris-buffered saline, 25% normal goat serum for 30 min, and washed again repeatedly for 5 min. Sections were blotted and mounted with VectaShield mounting medium for fluorescence with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Laboratories). Slides were viewed, and images were obtained with an Olympus inverted microscope and a Zeiss 510 LSM510 confocal microscope.

RESULTS

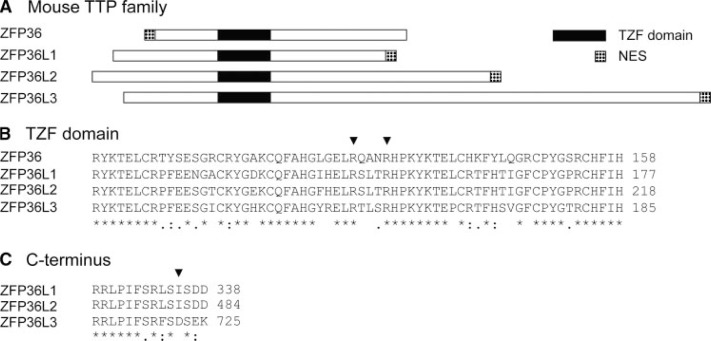

Identification of a Functional Nuclear Localization Sequence (NLS) within the TZF Domain of L3—Because NLSs appear to exist within the TZF domains of TTP, L1, and L2, and because TTP family members from a given animal species exhibit great sequence similarity within their TZF domains (Fig. 2, A and B), we investigated whether there was a functional NLS within the TZF domain of L3. A construct was made that expressed the L3 TZF domain alone fused to an N-terminal GFP-GFP tag. Site-directed mutagenesis was then utilized to alter the aforementioned conserved arginines within the inter-finger spacer of the TZF domain to alanines. The three mutants that were produced contained R153A alone, R157A alone, or both together. These four constructs were individually transiently transfected into 293 cells and analyzed with confocal microscopy to determine the subcellular localization of the fusion proteins. RNA gel shift experiments were also performed to assess the ability of these mutant TZF proteins to bind to a TNF ARE RNA probe.

FIGURE 2.

A, location of NLSs and NESs in mouse TTP family members. TZF domains, which contain the NLSs of TTP, L1, L2, and possibly L3, are shown in black. The N-terminal NES of TTP, C-terminal NESs of L1 and L2, and putative C-terminal NES of L3 are shown as dotted boxes. B, sequence alignment of TZF domains of TTP, L1, L2, and L3. The conserved inter-finger arginines are noted with arrowheads. C, sequence alignment of C termini of L1, L2, and L3. The fourth hydrophobic residue of the L1 and L2 NES, an aspartic acid in L3, is noted with an arrowhead.

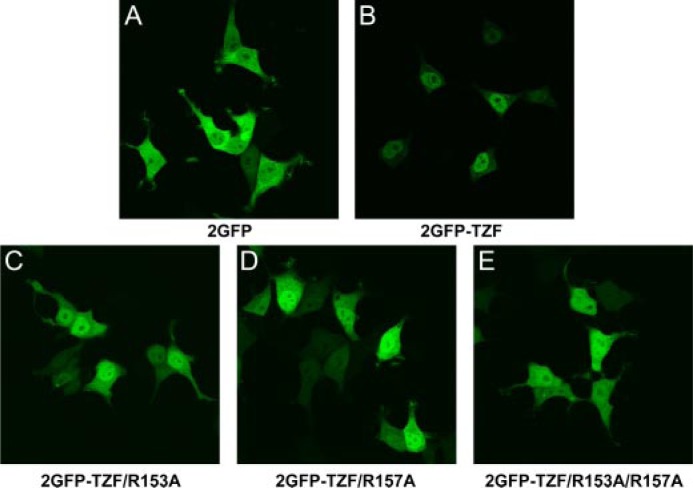

The TZF domain alone promoted nuclear localization of 2GFP-TZF in live cell fluorescence microscopy experiments in transfected 293 cells. Although 2GFP alone was distributed throughout the cell (Fig. 3A), the 2GFP-TZF peptide was observed almost exclusively within the nucleus (Fig. 3B). Mutation of each of the two arginines within the TZF domain to alanine, singly and together, resulted in some, but not complete, loss of nuclear localization (Fig. 3, C–E).

FIGURE 3.

Confocal images of the subcellular distributions of 2GFP-L3 TZF fusion proteins expressed in 293 cells. 2GFP alone (A) localizes throughout both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Note the predominantly nuclear localization of the fusion protein containing the native TZF domain (B) as compared with the increase in cytoplasmic localization of the fusion proteins containing TZF domains altered by mutation of the conserved inter-finger arginines, singly and together (C–E).

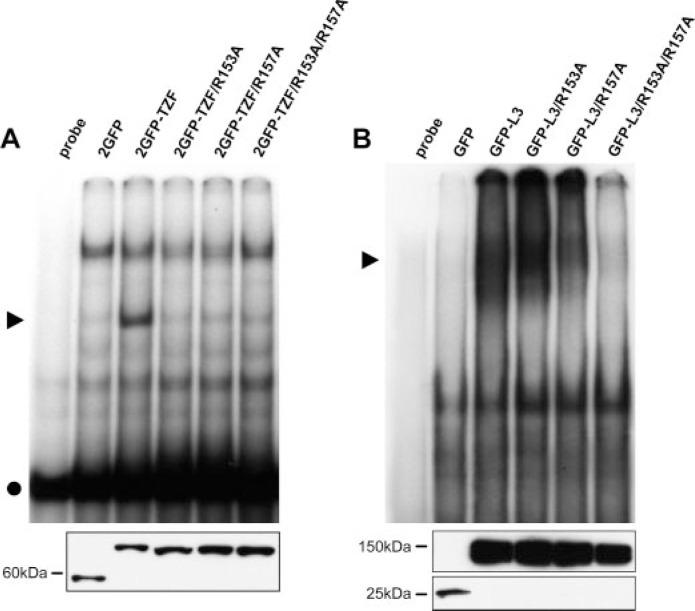

Gel shift analysis revealed that binding of these fusion proteins to an ARE probe was also completely disrupted by mutation of either of these arginines, or both together, whereas the intact 2GFP-TZF domain caused a typical gel shift with the ARE probe (Fig. 4A). Because of the possibility of abnormal folding of the mutant TZF proteins, RNA binding studies were also performed with full-length L3 fusion proteins containing the inter-finger arginine mutations (Fig. 4B). In the context of the intact protein, the single mutants appeared to shift the ARE RNA probe to some extent, whereas the double mutant showed no RNA binding ability. Equivalent levels of wild-type and mutant proteins are shown in the lower panel of Fig. 4.

FIGURE 4.

Gel shift analysis of L3 TZF (A) and full-length L3 (B) fusion proteins from extracts of transfected 293 cells incubated with a TNF ARE RNA probe. ▶ denotes the protein-RNA complex. ● denotes free probe. Note that although free probe can be seen on the 8% gel in A, it has run off the 4% gel in B. Western blots with an antibody directed at GFP to demonstrate fusion protein expression in each of the cell extracts used in each gel shift are shown below.

These data demonstrate that the Arg-153 and Arg-157 mutations not only inhibited the nuclear uptake of the L3 TZF domain, as well as the intact L3 protein, but at least the double mutant completely disrupted the fundamental structure of the TZF domain in such as way as to prevent RNA binding. The failure of nuclear uptake of these TZF domain mutants might thus be due to alterations in the structure of the TZF domain rather than disruption of a specific nuclear import sequence. To our knowledge, mutants have not yet been identified in any family member in which nuclear uptake is inhibited but normal affinity RNA binding is present.

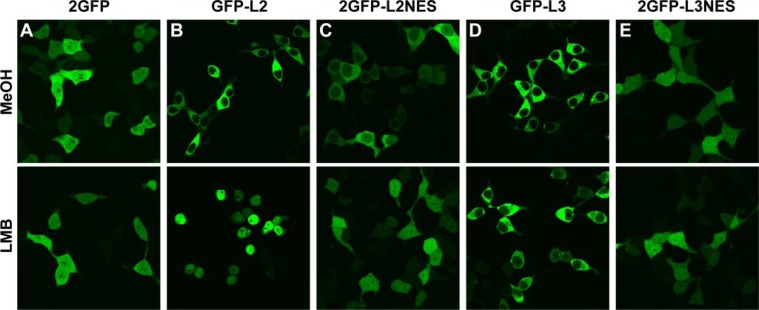

Evaluation of a Potential Nuclear Export Sequence (NES) within the C Terminus of L3—L1 and L2 contain functional nuclear export sequences (NES) within their extreme C termini, whereas TTP contains a functional NES at its extreme N terminus (18, 19) (Fig. 2A). The C terminus of mouse L3 exhibits high sequence similarity with those of L1 and L2, apart from a nonconserved substitution of an acidic residue for a presumed critical hydrophobic residue (Fig. 2C); this same substitution is present in the rat L3 sequence (14). To determine whether the putative NES of L3 is competent to mediate nuclear export, plasmids were prepared that expressed GFP fusion proteins containing full-length L2 or L3 and 2GFP fusion proteins containing only the NES from L3 or L2; note that the functional NES sequence for mouse L2 is identical to that for L1. These fusion proteins were expressed in 293 cells, which were then subjected to either control treatment or treatment with LMB to inhibit the nuclear export receptor CRM1. Upon addition to cells, LMB causes proteins with functional NESs, such as TTP, L1, and L2, to accumulate within the nucleus (18, 19). Confocal images were obtained 4–5 h after treatment.

Under these conditions, 2GFP alone was found throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus after addition of either the methanol control or LMB (Fig. 5A). As expected, GFP-L2 and 2GFP-L2NES, which contain functional NESs, accumulated in the nucleus after LMB treatment (Fig. 5, B and C). However, no differences were observed between control and LMB treatments when GFP-L3 and 2GFP-L3NES were expressed (Fig. 5, D and E). Furthermore, the subcellular distributions of 2GFP-L2NES and 2GFP-L3NES differed. Whereas 2GFP-L2NES was more abundant in the cytoplasm than in the nucleus, presumably because of its nuclear export activity (Fig. 5C), 2GFP-L3NES was distributed evenly throughout the cell (Fig. 5E), essentially identical to 2GFP alone. Taken together, these data indicate that the extreme C terminus of L3 has no detectable NES activity.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of LMB on the subcellular localization of full-length and nuclear export sequences of L2 and L3. 293 cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids, incubated for an additional 16–20 h, and then treated with either control conditions or 10 ng/ml LMB. Confocal images were captured at 4–5 h after treatment with LMB. Note the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of GFP alone that was unaffected by LMB treatment (A), compared with the nuclear accumulation of GFP-L2 (B), and 2GFP-L2NES (C) after LMB treatment, as opposed to the unchanged localization of GFP-L3 (D) and 2GFP-L3NES (E).

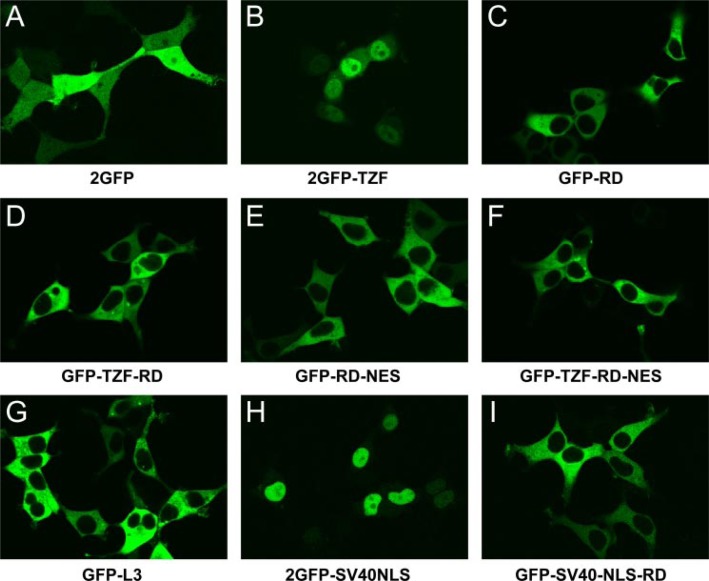

Effect of the Repeat Domain on the Subcellular Localization of L3—Although the TZF of L3 exhibited functional nuclear import activity, and the C terminus lacks nuclear export activity, this protein is unexpectedly cytoplasmic rather than nuclear (14). We postulated that the unique C-terminal repeat domain caused L3 to be localized to the cytoplasm. Plasmids were constructed that expressed GFP fusions containing the L3 repeat domain alone, as well as the L3 repeat domain linked to other portions of the protein. Two additional plasmids were prepared that contained the SV40 NLS to test the ability of the L3 repeat domain to potentially counteract the function of a well known, strong NLS. These fusions were expressed in 293 cells and were analyzed with fluorescence microscopy.

In control experiments, 2GFP alone was distributed throughout the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 6A), and 2GFP-TZF was predominantly nuclear (Fig. 6B). However, when the L3 C-terminal repeat domain was added to GFP, the fusion protein was detected only in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, with the addition of the N terminus, the TZF, and/or the rest of the C terminus to the repeat domain, the protein remained cytoplasmic (Fig. 6, D–G). Importantly, this cytoplasmic localization was seen with fusion proteins containing the active nuclear localization activity found within the TZF. Moreover, the L3 repeat domain promoted cytoplasmic localization of GFP in the presence of the strong NLS of SV40 (Fig. 6I); as expected, the 2GFP fusion protein containing the NLS of SV40 alone was exclusively nuclear (Fig. 6H). These data demonstrate that the repeat domain is a cytoplasmic localization domain and can override the nuclear localization activity of either the L3 or SV40 NLS.

FIGURE 6.

Confocal images of the subcellular distribution of full-length L3 and deletion mutants. 293 cells were transiently transfected to express GFP fusion proteins. Note the cytosolic localization of all fusion proteins containing the repeat domain (C–G and I), as compared with the 2GFP control (A) as well as 2GFP-TZF (B) and 2GFP-SV40NLS (H).

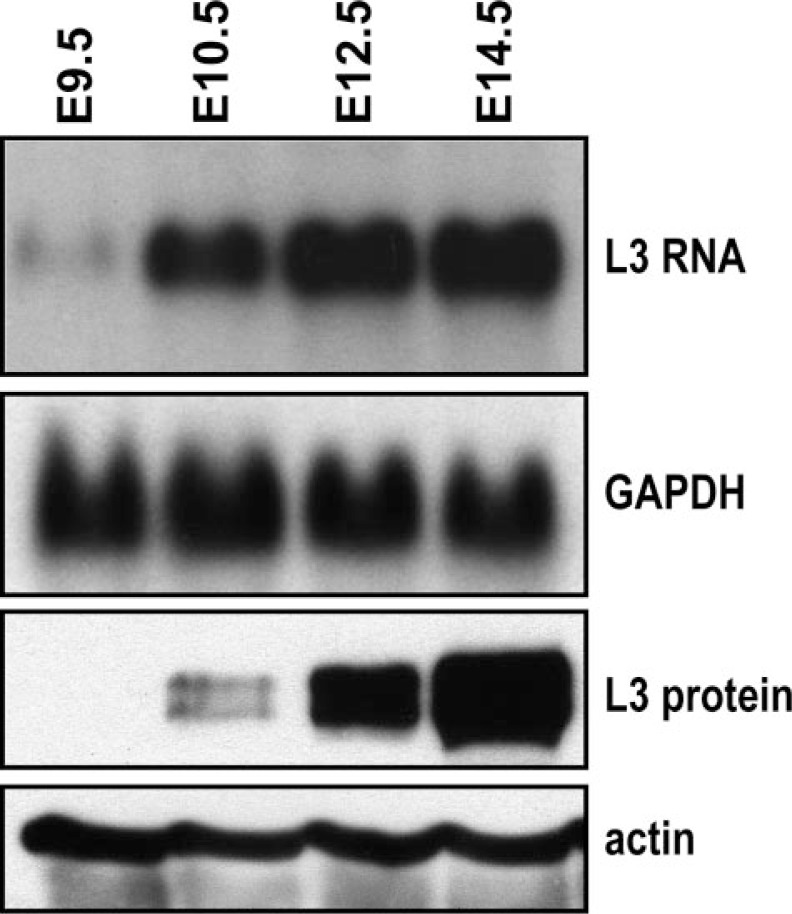

Subcellular Localization of Endogenous L3 in Mouse Placenta—L3 expression in mouse tissue has been previously examined solely at the RNA level. L3 transcripts were found exclusively in the placenta and yolk sac,4 where they were detected as early as E8.5 and peaked at E13.5 to E14.5 (14). Highest levels of mRNA expression were found in the labyrinthine layer of the placenta, with lower levels in the spongiotrophoblast and giant cell layers, and minimal expression was seen in the allantois and maternal decidua (14). In this study, we extended these results by investigating the developmental time course of RNA and protein expression, using Northern and Western blotting. Western blotting of placental extracts was performed with an antibody directed at an N-terminal peptide of L3.

L3 RNA transcripts were first detected at E9.5 and peaked at E12.5 to E14.5 (Fig. 7). L3 protein was first detected at E10.5, and then increased greatly by E14.5 (Fig. 7). The protein was expressed as two discrete bands of Mr ∼100 and 90 that were of approximately equal intensity under these conditions. Further work is underway to determine the biochemical difference between the two species, but it does not seem to be due to alternative translational initiation, premature truncation, or proteolysis, because a separate antibody directed at an extreme C-terminal peptide yielded similar Western blotting results.5

FIGURE 7.

Developmental expression of L3 mRNA and protein in mouse placenta. Placental RNA (20 μg each) and protein extracts (100 μg each) from the indicated embryonic days were subjected to Northern and Western blotting analysis, respectively, to detect L3 mRNA and protein expression. The levels of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA and actin protein are also shown as loading controls.

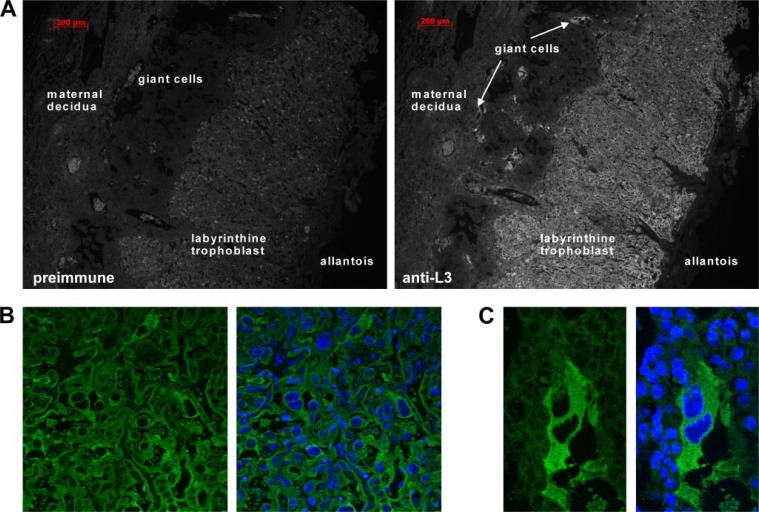

Because of the apparently high level of protein expression at E14.5 determined by Western blotting, placenta sections from that embryonic day were used for immunofluorescence studies in which the cellular and subcellular localization of the L3 protein was determined. In corroboration with previous RNA studies (14), the L3 protein was most highly expressed in the labyrinthine trophoblast layer, the primary site of materno-fetal exchange (Fig. 8, A and B), as well as in the trophoblast giant cells, which function in implantation and hormone production (Fig. 8, A and C). In confirmation of the cell transfection experiments, confocal microscopy with a nuclear counterstain confirmed that the protein was exclusively expressed in the cytoplasm of these cells, and its staining did not overlap with nuclear staining (Fig. 8, B and C).

FIGURE 8.

Cellular and subcellular localization of endogenous L3. Mouse placenta sections from E14.5 were incubated with either preimmune serum (A, left panel) or an anti-L3 antibody (A, right panel; B and C) followed by a fluorescent secondary antibody. Nuclei were also stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (shown in B, right panel, and C, right panel). L3 expression was readily detectable in the cells of the trophoblast layers, including the trophoblast giant cells. At the subcellular level, L3 was expressed exclusively in the cytoplasm of the labyrinthine trophoblast cells (B) and giant cells (C); this expression did not overlap with nuclear staining.

DISCUSSION

Through examination and modification of predicted subcellular localization domains, we have identified the basis for the apparent cytosolic restriction of the L3 protein. First, we demonstrated that, like the other mammalian members of the TTP family, L3 contains a functional NLS within its TZF domain. We provided evidence that the arginines within the inter-finger spacer that have been proposed to be critical to the NLS activity of TTP, L1, and L2 also affect the NLS activity of the L3 TZF domain. Although these arginines were demonstrated to be important for the import of the TZF domain of L3 into the nucleus, the same mutations in these conserved basic residues that prevented nuclear import had a variable effect on RNA binding, depending on whether the mutations were in the context of the TZF domain alone or in the intact protein. The double arginine mutant clearly exhibited loss of RNA binding activity, suggesting that major structural alterations in the TZF domain occurred as a result of these mutations. Typically, a monopartite or bipartite NLS contains clusters of basic amino acids, allowing for binding to a carrier protein, such as a member of the importin superfamily, and subsequent import to the nucleus; overall, this import is influenced by the Ran-GTP/GDP cycle (reviewed in Refs. 20–22). The NLS must be exposed on the surface of the protein in order for contact with binding partners, and masked NLSs can be revealed by a variety of mechanisms (24). Further studies are required to determine the specific residues that contribute to the NLS function of the TZF domain of all the TTP family members, including L3, and whether or not this function can be separated from the RNA binding activity of the same domain.

We have also demonstrated that the NES-like sequence that is present at the extreme C terminus of L3 is nonfunctional, presumably because of the presence of an acidic amino acid in the mouse and rat L3 sequence in place of a branched chain amino acid in the sequences of the other family members (14). This nonfunctional NES would therefore be unable to aid in nuclear export via CRM1. The NES is typically a short, leucine-rich sequence with defined spacing, and conserved hydrophobic residues constituting the NES have been shown to be required for export activity (25). This sequence was first identified in the viral protein HIV-Rev (26), a viral RNA exporter, and has now been found in many shuttling proteins, including TTP, L1, and L2 (18, 19). The nuclear export receptor CRM1, which is part of the nuclear pore complex, interacts directly with the NES to mediate the transport of NES-containing proteins; the Ran-GTP/GDP cycle also affects export from the nucleus (reviewed in Refs. 20–22. LMB has been shown to specifically inhibit NES-dependent nuclear export by binding to CRM1 (27, 28). We utilized LMB to block export via CRM1 to study the ability of the NES-like sequence of L3 to drive transport out of the nucleus. This sequence, when compared with the C-terminal NES of L2, did not behave like a functional NES. Although the NES of TTP is located at its N terminus, there is no evidence for a leucine-rich or hydrophobic-rich region characteristic of an NES in this region of L3. No other likely NESs were found in the rest of the L3 sequence, suggesting that it does not contain a functional NES.

Finally, we found that the unusual C-terminal repeat domain, which is unique to L3 within the TTP family, can override the nuclear uptake activity of the L3 TZF domain, causing the protein to be restricted to the cytoplasm. This makes L3 the only family member that apparently does not shuttle between nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. This cytoplasmic localization was seen not only in cell transfection studies but also in studies of the subcellular localization of the endogenous protein in placental trophoblast cells. The shuttling of TTP, L1, and L2 could be a means of regulating their mRNA binding and destabilizing activities. It has been shown that TTP translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm upon addition of mitogens (29). Furthermore, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways have been implicated in regulating the subcellular localization and stability of the TTP protein (30). In the case of TTP, an initial stimulus could be responsible for creating a signal cascade that leads to shuttling of the protein and, ultimately, could affect the ability of the protein to perform its function.

The mechanism by which the repeat domain confers cytoplasmic localization on the L3 protein is unknown. It is possible that the repeat domain simply prevents nuclear import because of its sheer size or that it targets L3 to a membrane, organelle, or other protein partners. Additional research is necessary to determine the function of the repeat domain and its contribution to the activities of L3. However, because placental immunofluorescence staining confirms its cytosolic localization in vivo, its similarities to and differences from the other family members in terms of activity must take into account this unique localization.

In addition to its unique subcellular localization and C-terminal repeat domain, L3 differs from the other TTP family members in several other respects. First, we have demonstrated that the L3 gene is intronless (14), whereas all other members have a single intron. Second, our data indicate that the expression of L3 is restricted to rodents (14). Both rat and mouse mRNA sequences are present in GenBank™ at the respective accession numbers XM_228661.2 and AY661338.1. By Northern analysis, we have identified mRNA bands of similar size that hybridize to the mouse cDNA probe in placenta samples from golden hamster and gerbil,5 but not from other mammals tested, including guinea pig. Finally, the tissue distribution of L3 is unique compared with the other family members, with expression detected only in the placenta and yolk sac of mice (14). In addition to determining its function in the physiology of these tissues, it will be interesting to uncover the evolutionary events that occurred to allow this gene to develop and remain in rodents, but apparently not in other mammals. It will also be appealing from a practical perspective to determine whether one or more of the other TTP family members has subsumed the role of L3 in yolk sac and placental physiology in other mammalian species.

By analogy to other family members, as well as its activity as revealed in cell transfection experiments (14), L3 is predicted to act as a regulator of mRNA destabilization in the placenta. We predict that L3 will be found to perform the general functions of a TTP family member in the specific location of placental trophoblast cells. Attempts to determine its physiological targets, as well as its importance in placental development or physiology, are currently underway. The generation of a knock-out mouse will be particularly important in this regard, because mice deficient in TTP, L1, and L2 exhibit defects in completely distinct physiological processes as follows: inflammation (31), chorioallantoic fusion (32) and early embryonic proliferation (33), respectively.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jeff Reece for assistance with confocal microscopy and Debbie Stumpo, Wi Lai, Martyn Darby, and Jane Tuttle for reagents and advice. We also thank John Couse and Bill Schrader for critical review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was authored, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health staff. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIEHS. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: TTP, tristetraprolin; TZF, tandem zinc finger; ARE, AU-rich element; L1, ZFP36L1; L2, ZFP36L2; L3, ZFP36L3; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; NES, nuclear export sequence; SV40, simian virus 40; 293 cells, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; LMB, leptomycin B; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; ECL, enhanced chemiluminescence; E, embryonic day; GFP, green fluorescent protein; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; NES, nuclear export sequence.

All mouse experiments were conducted according to the United States Public Health Service policy on the humane care and use of laboratory animals. All animal procedures used in this study were approved by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

D. J. Stumpo and P. J. Blackshear, unpublished data.

E. D. Frederick and P. J. Blackshear, unpublished data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Varnum BC, Lim RW, Sukhatme VP, Herschman HR. Oncogene. 1989;4:119–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai WS, Stumpo DJ, Blackshear PJ. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16556–16563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DuBois RN, McLane MW, Ryder K, Lau LF, Nathans D. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:19185–19191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Q, Herschman HR. Oncogene. 1991;6:1277–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor GA, Lai WS, Oakey RJ, Seldin MF, Shows TB, Eddy RL, Jr, Blackshear PJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:3454. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.12.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heximer SP, Forsdyke DR. DNA Cell Biol. 1993;12:73–88. doi: 10.1089/dna.1993.12.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomperts M, Pascall JC, Brown KD. Oncogene. 1990;5:1081–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varnum BC, Ma QF, Chi TH, Fletcher B, Herschman HR. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1754–1758. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bustin SA, Nie XF, Barnard RC, Kumar V, Pascall JC, Brown KD, Leigh IM, Williams NS, McKay IA. DNA Cell Biol. 1994;13:449–459. doi: 10.1089/dna.1994.13.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maclean KN, See CG, McKay IA, Bustin SA. Genomics. 1995;30:89–90. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ning ZQ, Norton JD, Li J, Murphy JJ. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2356–2363. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nie XF, Maclean KN, Kumar V, McKay IA, Bustin SA. Gene (Amst) 1995;152:285–286. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00696-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maclean KN, McKay IA, Bustin SA. Br J Biomed Sci. 1998;55:184–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackshear PJ, Phillips RS, Ghosh S, Ramos SB, Richfield EK, Lai WS. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:297–307. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23144–23154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai WS, Carballo E, Strum JR, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Blackshear PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4311–4323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai WS, Carballo E, Thorn JM, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17827–17837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips RS, Ramos SB, Blackshear PJ. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11606–11613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murata T, Yoshino Y, Morita N, Kaneda N. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:1242–1247. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pemberton LF, Paschal BM. Traffic. 2005;6:187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoneda Y. Genes Cells. 2000;5:777–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nigg EA. Nature. 1997;386:779–787. doi: 10.1038/386779a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao H, Tuttle JS, Blackshear PJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21489–21499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boulikas T. Crit Rev Eukaryotic Gene Expression. 1993;3:193–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogerd HP, Fridell RA, Benson RE, Hua J, Cullen BR. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4207–4214. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer U, Huber J, Boelens WC, Mattaj IW, Luhrmann R. Cell. 1995;82:475–483. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudo N, Wolff B, Sekimoto T, Schreiner EP, Yoneda Y, Yanagida M, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:540–547. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo N, Matsumori N, Taoka H, Fujiwara D, Schreiner EP, Wolff B, Yoshida M, Horinouchi S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9112–9117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor GA, Thompson MJ, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:140–146. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.2.8825554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brook M, Tchen CR, Santalucia T, McIlrath J, Arthur JS, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2408–2418. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2408-2418.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor GA, Carballo E, Lee DM, Lai WS, Thompson MJ, Patel DD, Schenkman DI, Gilkeson GS, Broxmeyer HE, Haynes BF, Blackshear PJ. Immunity. 1996;4:445–454. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stumpo DJ, Byrd NA, Phillips RS, Ghosh S, Maronpot RR, Castranio T, Meyers EN, Mishina Y, Blackshear PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6445–6455. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6445-6455.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos SB, Stumpo DJ, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Bock CB, Ribeiro-Neto F, Blackshear PJ. Development (Camb) 2004;131:4883–4893. doi: 10.1242/dev.01336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]