Abstract

Introduction:

This study examined whether the appeal of actors (i.e., their likeability and attractiveness) used in antismoking public service announcements (PSAs) interacts with adolescents’ risk of future smoking to predict adolescents’ smoking resistance self-efficacy and whether the antismoking messages in the PSAs further moderate this relationship.

Methods:

We used a 2 (future smoking risk: low, high) × 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 3 (PSA antismoking message: tobacco industry manipulation, short-term smoking effects, long-term smoking effects) study design. A diverse sample of 110 adolescents (aged 11–17 years), with varying levels of experience with smoking, rated their smoking resistance self-efficacy after viewing each of the PSAs in each design cell.

Results:

Overall, PSAs that used long-term smoking effects messages were associated with the strongest smoking resistance self-efficacy, followed in turn by PSAs that used short-term smoking effects messages and by tobacco industry manipulation messages. We found a significant interaction of actor appeal and PSA antismoking message. The use of more appealing actors was associated with stronger smoking resistance self-efficacy only in long-term smoking effects PSAs. The use of less appealing actors was associated with stronger smoking resistance self-efficacy for tobacco industry manipulation PSAs and short-term smoking effects PSAs. Future smoking risk did not moderate any of these findings.

Discussion:

Antismoking PSAs that emphasize long-term smoking effects are most strongly associated with increased smoking resistance self-efficacy. The effect of these PSAs can be strengthened by using actors whom adolescents perceive to be appealing.

Introduction

Televised antismoking public service announcements (PSAs) are a key component of any successful smoking prevention campaign directed at adolescents (Farrelly, Davis, Duke, & Messeri, 2009; Niederdeppe, Farrelly, & Haviland, 2004; Thrasher et al., 2003; for reviews, see National Cancer Institute, 2008; Wakefield, Flay, Nichter, & Giovino, 2003). For example, one of the more effective nationally released multimedia campaigns directed at adolescents has been the “Truth” campaign, funded by the American Legacy Foundation (2002). This multimedia campaign, which includes an extensive televised PSA component, uses rebellious-appearing actors who reject smoking and promote the idea that tobacco companies engage in deceptive advertising practices to “hook” young people (see American Legacy Foundation, 2002). In a nationally representative sample of 12- to 17-year-olds, awareness of the Truth campaign increased from 9.5% to 47.6% after nearly a year of the campaign (American Legacy Foundation, 2002). Television was, by far, the most commonly reported source of the antismoking message (91%), and increased exposure to the campaign has been associated with less favorable smoking attitudes and intentions in adolescents (Farrelly et al., 2009). An analysis of those advertising features and themes of the Truth campaign that generated the strongest levels of receptivity among teens in this national sample (i.e., that the advertisement was convincing, was attention grabbing, stimulated peer communication, and gave good reasons to not smoke) were those that emphasized tobacco industry manipulation and health effects of smoking (American Legacy Foundation, 2002).

Other studies have yielded different conclusions about the most effective components of antismoking PSAs more genes, however. Some studies have indicated that the characteristics perceived by adolescents to be most effective in antismoking media campaigns include tailoring the antismoking advertisements to appeal to an adolescent market, using adolescent spokespeople to deliver antismoking messages, designing easily comprehended messages, and focusing on antismoking themes of the dangers of secondhand smoke, negative role model images of smokers, and the tobacco industry's deceptive portrayal of a lethal product (Goldman & Glantz, 1998; Pechmann & Reibling, 2000). Pechmann, Zhao, Goldberg, and Reibling (2003) found that normative information about the social undesirability of smoking was most effective in reducing intentions to smoke among adolescents. In contrast, other studies found that antismoking advertisements that emphasize normative information are lower in perceived effectiveness compared with advertisements that emphasize the long-term consequences of smoking (Biener, 2002; Biener, Ji, Gilpin, & Albers, 2004). Moreover, other studies found that a focus on short-term social and health consequences was more appealing to youth than a focus on long-term consequences (Beaudoin, 2002). Some studies suggested that PSAs that focus on tobacco industry manipulation are ineffective with adolescents (Pechmann & Reibling, 2006; Sutfin, Szykman, & Moore, 2008). Finally, some studies found that the short- and long-term detrimental effects of smoking and the suggestion of romantic rejection if one smokes were not effective antismoking advertising ingredients (Goldman & Glantz, 1998).

Overall, these data suggest that televised antismoking PSAs can be effective at reaching adolescents and can effectively reduce adolescent smoking. Information also is available—albeit highly conflicting information—about what features of antismoking PSAs are most effective with adolescents. Almost no information is available, however, about whether tailoring antismoking PSAs to particular segments of the population is effective (e.g., population subgroups that differ on some demographic or smoking history characteristic; see Farrelly et al., 2002; Wakefield et al., 2003). The research conducted to date suggests that message factors are more important than audience factors in predicting responsivity to antismoking PSAs, but much more work needs to be conducted in this domain of inquiry (National Cancer Institute, 2008). Indeed, the dollars allocated to tobacco control efforts are shrinking dramatically and are only a fraction of what is spent by the tobacco industry on advertising and marketing (American Legacy Foundation, 2002). As a result, it is important to know which PSA ingredients contribute most strongly to adolescent smoking prevention, how they operate, and for whom they are most effective. Such information is needed to give public health officials empirically driven guidance as to which PSAs they should choose and PSA developers empirically based data with which to design future antismoking PSAs. At this point, no clear consensus exists on these critical issues.

To provide guidance on these issues, we examined which features of antismoking PSAs contribute most strongly to adolescents’ smoking resistance self-efficacy. In particular, we analyzed the appeal of actors used in antismoking PSAs. Actor appeal was defined as an actor's likeability and attractiveness. These two constructs contribute to peripheral route processing of persuasive communications when audience processing motivation (i.e., level of personal investment with the issue at hand) is low (elaboration likelihood model of persuasion; see Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Petty & Wegener, 1999). Persuasion that occurs via the peripheral route results from the operation of cues in the persuasion context, such as the attractiveness and likeability of the sources associated with the persuasive message. Peripheral cues drive persuasion regardless of the quality (i.e., strength) of the arguments presented in the message. In other words, regardless of the quality of the persuasive argument presented, persons who are lower in processing motivation are most influenced by the attractiveness and likeability of the source that is communicating those persuasive arguments. A more attractive source will lead to stronger levels of persuasion than a less attractive source, regardless of the quality of the persuasive communication, when someone is low in processing motivation.

In this context, it is reasonable to suggest that adolescent nonsmokers differ in their level of personal investment with smoking (i.e., level of processing motivation) and, as such, will respond differently to PSAs that differ in their level of actor appeal. Specifically, adolescent nonsmokers who have low future smoking intentions may not be personally invested in antismoking PSAs because smoking is not personally relevant to them. Adolescent nonsmokers who have low future smoking intentions are hypothesized to be the most influenced by the peripheral cues in antismoking PSAs. Antismoking PSAs that use more appealing (i.e., more attractive and likeable) actors will be associated with stronger smoking resistance self-efficacy than PSAs that use less appealing actors. In contrast, adolescent nonsmokers who have higher smoking intentions may be more personally invested in smoking and, as such, more motivated to process antismoking PSAs (i.e., smoking is more relevant to them because they intend to smoke in the future). These individuals are hypothesized to be less influenced by the peripheral cues in antismoking PSAs. Level of actor appeal will not be associated with smoking resistance self-efficacy for adolescent nonsmokers with higher future smoking intentions.

The interaction between actor appeal and future smoking intentions may be manifested differently depending on the antismoking message being emphasized by the PSA. For example, tobacco industry manipulation PSAs may be more effective than PSAs that use other antismoking messages when they use more attractive and likeable actors, especially for adolescents with a low risk for future smoking. An exploratory aim of this research, then, was to examine whether the actor appeal and future smoking intentions interaction is manifested differently in PSAs that use different antismoking messages (i.e., a three-way interaction). Smoking resistance self-efficacy is a consistently significant predictor of adolescent smoking (see Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Pierce, 2001; Sussman, Dent, Flay, Hansen, & Johnson, 1987). As a consequence, it is a reasonable dependent measure to use in laboratory-based studies of adolescent smoking.

Methods

Procedures

This study used a laboratory-based paradigm with a 2 (future smoking risk: low, high) × 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 3 (PSA antismoking message: tobacco industry manipulation, short-term smoking effects, long-term smoking effects) mixed-model design. Future smoking risk was a between-subjects factor; actor appeal and PSA antismoking message were within-subjects factors. All participants attended three group sessions, with about 1 week between sessions. Sessions were held in rooms arranged like a classroom, with participants facing a projection screen. Session 1 tasks included informed consent procedures and completion of baseline questionnaires. Session 2 tasks consisted of participants rating the actor images drawn from each of the PSAs. Session 3 tasks included participants viewing each PSA in its entirety and rating their smoking resistance self-efficacy after exposure to each PSA (the PSAs were shown to participants in randomly determined orders). At the end of Session 3, participants were debriefed, compensated with up to US$60 worth of gift certificates to a local shopping mall, and provided with written smoking prevention materials (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2000).

Participants

The present study was approved by the Human Subjects Protection Committee at the RAND Corporation. Adolescents were recruited using print media advertising and also were recruited from a local community center in Pittsburgh, PA. The study was marketed as a general television advertising study; none of this advertising material mentioned cigarettes, smoking, or antismoking advertising. The study parameters and requirements were explained to potential participants during brief phone screenings. Inclusion criteria were as follows: being 11–17 years of age, having no physical or psychiatric problem that would interfere with completing the study (based on parent report), and providing written parental consent and written adolescent assent to participate. A total of 194 adolescents were screened for the study; 157 were eligible or chose to participate and were scheduled. A total of 121 adolescents attended the first session (55% female; 38% White, 53% Black, 2% Asian, 2% Native American, and 5% multiethnic). Their mean age was 14.1 years (SD = 1.8). A total of 22 (18%) of this sample reported smoking at least a puff of a cigarette in the past; none of the participants were current smokers. Due to missing data across the three sessions, 110 participants comprised the final sample available for analysis in this study.

Stimulus preparation

The PSAs.

The PSAs were drawn from the no cost catalogue maintained by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's Media Campaign Resource Center. The PSAs were originally produced in the following states: Arizona, California, Florida, Massachusetts, Mississippi, and Nebraska. A total of 21 PSAs, each 30–31 seconds in length, were examined in this study. Three judges were trained on the different themes that are prevalent in antismoking PSAs, based on criteria and definitions supplied by Goldman and Glantz (1998): tobacco industry manipulation, secondhand smoke, addiction, cessation, youth access, short-term effects, long-term effects, and romantic rejection. The judges then independently viewed and sorted each of the PSAs into one of these categories. The interrater reliability was .814. The PSAs were sorted reliably, then, into the following categories: 11 PSAs featured antismoking messages that emphasized tobacco industry manipulation, 4 PSAs featured antismoking messages that emphasized short-term smoking effects, and 6 PSAs featured antismoking messages that emphasized long-term smoking effects. The PSAs used actors who were diverse in terms of age, gender, race, and ethnicity. All the PSAs had a negatively valenced emotional tone or contained disturbing imagery.

Actor image extraction.

Photographs of the actors used in each of the 21 PSAs were extracted digitally. This process yielded a total of 26 actor images or 1.2 actor images per PSA. Participants rated each actor image on their level of attractiveness (1 = not at all attractive; 10 = very attractive) and likeability (1 = not at all likeable; 10 = very likeable). The attractiveness and likeability items were highly correlated within each actor image (all r values > .65, p values < .0001). They were summed to form a single item for each actor image, termed actor appeal. An actor appeal grand mean (M) was calculated for all the actor images across all participants who attended session 2 (grand M = 7.5, SD = 2.8). PSAs that had actor-appeal ratings that fell below this grand mean value were classified as low–actor-appeal PSAs (11 PSAs), and PSAs that had actor-appeal ratings that were above this grand mean were classified as high–actor-appeal PSAs (10 PSAs).

Final PSA stimuli.

Low– and high–actor-appeal PSAs were sorted into groups by the antismoking message used by the PSAs. The following final PSA stimuli were used: (a) tobacco industry manipulation PSAs, low actor appeal (five PSAs) and high actor appeal (six PSAs); (b) short-term smoking effects and low actor appeal (two PSAs), high actor appeal (two PSAs); and (c) long-term smoking effects, low actor appeal (four PSAs) and high actor appeal (two PSAs). Actor-appeal ratings for all high–actor-appeal PSAs were significantly greater than actor-appeal ratings for all low–actor-appeal PSAs, regardless of antismoking message (all p values < .0001).

Measure of future smoking risk

Smoking intentions at baseline were assessed using a three-item scale adapted from items used by Choi et al. (2001) and shown to predict smoking initiation: “Do you think you will try a cigarette anytime soon?” “Do you think you will smoke a cigarette anytime in the next year?” and “If one of your best friends offered you a cigarette, would you smoke it?” Responses were made on a scale from 1 (definitely not) to 10 (definitely yes) and summed to produce a baseline smoking intention scale score (possible range of 3–30). Higher scores indicated stronger intentions to smoke. Participants who scored 3 (i.e., responded “definitely not” to all three items) were coded as “low risk” (n = 81), and participants who scored greater than 3 were coded as “high risk” (n = 29; see Choi et al., 2001).

Dependent measure

Participants’ smoking resistance self-efficacy was assessed after exposure to each PSA with the following statement: “This PSA gives me the confidence to resist smoking if a friend offers me a cigarette” (1 = definitely no; 10 = definitely yes). This item was drawn from the smoking resistance self-efficacy items developed and used by Ellickson and colleagues (Ellickson & Hays, 1992; Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein, 2002). Responses for each PSA were averaged within each of the six within-subjects design cells to produce a total smoking resistance self-efficacy score for each cell. Higher scores reflected stronger smoking resistance self-efficacy.

Finally, participants were asked, after responding to the self-efficacy measure for each PSA, whether they recalled having seen that PSA at some point in the past. The majority of participants reported having never seen any of the PSAs (range across PSAs = 55%–72%).

Data analyses

A 2 (future smoking risk: low, high) × 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 3 (PSA antismoking message: tobacco industry manipulation, short-term smoking effects, long-term smoking effects) mixed-model general linear model (SPSS version 16.0) was used to analyze smoking resistance self-efficacy ratings. Gender, age, race, ethnicity, previous smoking experience, and recall of seeing the PSAs in the past were considered in the GLM analysis but were not significant factors. These factors were not evaluated further.

Results

The three-way interaction between future smoking risk, actor appeal, and antismoking message was not significant, F(2, 107) = .213, p = .809. Future smoking risk did not interact with actor appeal, F(1, 108) = .019, p = .891, nor did it interact with antismoking message, F(1, 107) = .480, p = .620. The main effects of future smoking risk were significant, F(1, 108) = 4.39, p = .038, partial η2 = .039, indicating that participants who had lower future smoking risk overall said they had higher levels of smoking resistance self-efficacy in response to the antismoking PSAs (M = 8.0 vs. 7.3). In addition, the results revealed a main effect of antismoking message, F(2, 107) = 37.65, p < .0001, partial η2 = .413. PSAs that emphasized long-term smoking effects were associated with the strongest smoking resistance self-efficacy scores, followed by PSAs that emphasized short-term smoking effects and, last, by PSAs that emphasized tobacco industry manipulation (all p values < .05). The main effects for actor appeal, F(1, 108) = .407, p = .525, were not significant.

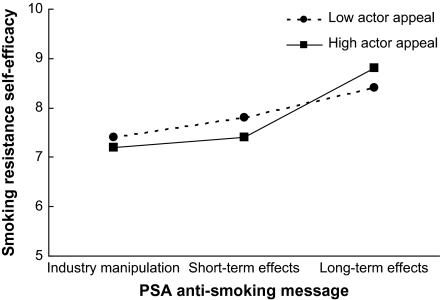

We found a significant two-way interaction between actor appeal and antismoking message, F(2, 107) = 7.608, p = .001, partial η2 = .125. Figure 1 illustrates these results by plotting mean smoking resistance self-efficacy as a function of condition. To determine the source of this significant interaction, we analyzed separately each of the three different 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 2 (PSA antismoking message) segments. The 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 2 (PSA antismoking message: tobacco industry manipulation, short-term smoking effects) analysis revealed only a significant main effect for actor appeal, F(1, 107) = 9.13, p = .003, partial η2 = .079, and a marginally significant effect for PSA antismoking message, F(1, 107) = 2.84, p < .09, partial η2 = .026; there was no significant interaction effect, F(1, 107) = 1.18, p = .280, partial η2 = .011. However, the 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 2 (PSA antismoking message: short-term smoking effects, long-term smoking effects) analysis revealed a significant interaction effect, F(1, 107) = 15.03, p < .0001, partial η2 = .123. We also found a significant interaction for the 2 (actor appeal: low, high) × 2 (PSA antismoking message: tobacco industry manipulation, long-term smoking effects) analysis, F(1, 107) = 9.51, p = .0003, partial η2 = .082.

Figure 1.

Smoking resistance self-efficacy scores as a function of actor appeal and PSA antismoking message.

Specific comparisons in these interactions revealed the following findings. PSAs that emphasized short-term smoking effects (p < .0001) and tobacco industry manipulation (p = .001) were associated with significantly stronger levels of smoking resistance self-efficacy when they used less, versus more, appealing actors. In contrast, PSAs that emphasized long-term smoking effects were associated with significantly stronger levels of smoking resistance self-efficacy when they used more, versus less, appealing actors (p = .001).

Discussion

The present study examined whether the appeal of actors (i.e., their likeability and attractiveness) used in antismoking PSAs interacted with adolescents’ risk of future smoking to predict adolescents’ smoking resistance self-efficacy and whether the antismoking messages in the PSAs further moderated this relationship. No consensus exists as to the most effective antismoking messages that should be used in antismoking PSAs (National Cancer Institute, 2008), and the way in which actor characteristics moderate the effectiveness of PSAs with different antismoking messages has not been studied. Moreover, it is not clear what antismoking PSAs are most effective with which populations of adolescents (National Cancer Institute, 2008). Information about how features of antismoking PSAs operate together to affect adolescent smoking behavior can be used by consumers and designers of antismoking PSAs to ensure that the most effective PSAs are being tailored to the most appropriate population of adolescents.

We found that antismoking PSAs that emphasized the long-term effects of smoking were associated with the strongest smoking resistance self-efficacy in adolescents, compared with PSAs that emphasized short-term smoking effects and tobacco industry manipulation. These results are consistent with findings from other studies that PSAs that emphasize the short- and long-term consequences of smoking are most effective (e.g., Biener, 2002; Biener et al., 2004; cf., Goldman & Glantz, 1998) and that PSAs that emphasize tobacco industry manipulation are least effective (Pechmann & Reibling, 2006) in affecting adolescent smoking. More important, however, the results of the present study go beyond findings from previous research by showing that the efficacy of PSAs that emphasize the long-term effects of smoking can be enhanced by using actors who are perceived by adolescents to be more appealing (i.e., more attractive and likeable). In contrast, using less-attractive actors in PSAs that emphasize messages about the short-term effects of smoking and tobacco industry manipulation was associated with stronger smoking resistance self-efficacy.

Adolescents’ risk of future smoking did not significantly moderate any findings in this study. To the extent that risk of future smoking is an index of personal relevance and, hence, processing motivation (see Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), these findings do not support the elaboration likelihood model. These nonsupportive results could be due to methodological reasons. For example, future smoking intentions may not be a valid index of processing motivation; alternatively, there may not have been sufficient variance in future smoking intentions to support its role in this interaction. Future research should attempt to disentangle these complex processing effects (e.g., Rhodes, Roskos-Ewoldsen, Edison, & Bradford, 2008).

The present findings were not moderated further by participant age, race, ethnicity, gender, or experience with smoking. These findings, combined with the lack of moderation found for future smoking risk, are consistent with a small but emerging body of literature that has, thus far, failed to find an effect of targeting PSAs to different population groups (e.g., Farrelly et al., 2002; Wakefield et al., 2003). Additionally, these findings are consistent with recent conclusions that message factors may be more important than audience factors in antismoking PSAs and media (National Cancer Institute, 2008). Targeting antismoking PSAs to different population segments may not be warranted, although additional research is warranted in this domain.

Limitations of the present study need to be taken into account in the interpretation of its results. First, the study used essentially a correlational design. As such, causal interpretations need to be made with caution. Future research should use more fully controlled experimental and prospective designs. Second, the study did not include a control group (e.g., a group that was not exposed to antismoking PSAs). Thus, we cannot say for certain that the observed differences in self-efficacy were due to PSA exposure specifically. Third, although smoking resistance self-efficacy is a key predictor of smoking outcomes among adolescents (e.g., Choi et al., 2001), we did not measure actual smoking behavioral outcomes. Fourth, the PSAs that we used as stimuli were by necessity limited, and the findings may not generalize to other PSAs. It is unclear how actor-appeal functions in PSAs that emphasize other antismoking messages (e.g., secondhand smoke). Finally, our sample was a reactively recruited, convenience sample. While diverse in its representation of Black youth and reflective of the racial diversity in Pittsburgh, PA, it was limited in its representation of adolescents of other ethnic groups and of adolescents with more intensive smoking histories. Caution should be used in generalizing the results to other adolescent populations.

In conclusion, the results of the present study imply that antismoking PSAs should use messages that emphasize the long-term effects of smoking and that attractive and likeable actors (as perceived by adolescents) should appear in those PSAs. We recommend that public health officials who are charged with securing antismoking PSAs as part of a larger smoking prevention campaign choose PSAs with these features. We also recommend that construction of new antismoking PSAs attend to such actor and message factors in order to make the most efficient use of limited funds.

Funding

National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21 DA019920); the National Institutes of Health National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (2P60MD00207-07 to CSF; S. Thomas, PI).

Declaration of Interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Carroll, Preethi Sama, and Michelle Horner for their invaluable assistance in executing the procedures of this research and the staff at the Center for Healthy Hearts and Souls for their cooperation in executing this research.

References

- American Legacy Foundation. Getting to the truth: assessing youths' reactions to the truth and “Think, Don't Smoke” tobacco countermarketing campaigns. 2002 Retreived March 23, 2009, from http://americanlegacy.org/PDFPublications/F1-9.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin C. Exploring antismoking ads: Appeals, themes, and consequences. Journal of Health Communication. 2002;7:123–137. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L. Anti-tobacco advertisements by Massachusetts and Philip Morris: What teenagers think. Tobacco Control. 2002;11(Suppl. 2) doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_2.ii43. ii43–ii46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Ji M, Gilpin E, Albers A. The impact of emotional tone, message, and broadcast parameters in youth anti-smoking advertisements. Journal of Health Communication. 2004;9:259–274. doi: 10.1080/10810730490447084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W, Gilpin E, Farkas A, Pierce J. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96:313–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96231315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson P, Hays R. On becoming involved with drugs: Modeling adolescent drug use over time. Health Psychology. 1992;11:377–385. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.6.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Davis KD, Duke J, Messeri P. Sustaining “truth”: Changes in youth tobacco attitudes and smoking intentions after 3 years of a national antismoking campaign. Health Education Research. 2009;24:42–8. doi: 10.1093/her/cym087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Healton C, Davis KC, Messeri P, Hersey JC, Haviland ML. Getting to the truth: Evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:901–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman L, Glantz S. Evaluation of anti-smoking advertising campaigns. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:772–777. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. 2008. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. NIH Publication No. 07–6242 Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Mind over matter: The brain's response to nicotine. 2000. NIH Publication No. 00-4248. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Haviland ML. Confirming “truth”: More evidence of a successful tobacco countermarketing campaign in Florida. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:255–257. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann C, Reibling ET. Anti-smoking advertising campaigns targeting youth: Case studies from USA and Canada. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:18–31. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_2.ii18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann C, Reibling ET. Antismoking advertisements for youths: An independent evaluation of health, counter-industry, and industry approaches. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:906–913. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann C, Zhao G, Goldberg ME, Reibling ET. What to convey in antismoking ads for adolescents? The use of protection motivation theory to identify effective message themes. Journal of Marketing. 2003;67:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo J. Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Wegener DT. The elaboration likelihood model: Current status and controversies. In: Chaikin S, Trope Y, editors. Dual process theories in social psychology. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes N, Roskos-Ewoldsen DR, Edison A, Bradford M. Attitude and norm accessibility affect processing of anti-smoking messages. Health Psychology. 2008;27(3 Suppl.):S224–S232. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3(suppl.).s224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Dent CW, Flay BR, Hansen WB, Johnson CA. Psychosocial predictors of cigarette smoking onset by White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents in Southern California. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports. 1987;36(Suppl. 4):11S–16S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin EL, Szykman LR, Moore MC. Adolescents’ responses to anti-tobacco advertising: Exploring the role of adolescents’ smoking status and advertising theme. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13:480–500. doi: 10.1080/10810730802198961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher JF, Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Ribisl KM, Haviland ML. The impact of anti-tobacco industry prevention messages in tobacco producing regions: Evidence from the US truth campaign. Tobacco Control. 2003;13:283–288. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Ellickson P, Klein D. Smoking cessation during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4:321–332. doi: 10.1080/14622200210142698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M, Flay B, Nichter M, Giovino G. Effects of anti-smoking advertising on youth smoking: A review. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:229–247. doi: 10.1080/10810730305686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.