Abstract

Purpose

Congenital cataracts are one of the most treatable causes of visual impairment and blindness during infancy. Approximately 50% of all congenital cataract cases may have a genetic cause. Once there is an intimate relationship between crystallin genes and lens transparency, they are excellent candidate genes for inherited cataract. The purpose of this study was to investigate mutations in αA-crystallin (CRYAA), γC-crystallin (CRYGC), and γD-crystallin (CRYGD) in Brazilian families with nuclear and lamellar autosomal dominant congenital cataract.

Methods

Eleven Brazilian families were referred to the Santa Casa de São Paulo Ophthalmology Department. The coding regions and intron/exon boundaries of CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and directly sequenced. Mutation screening was performed in the control group by restriction digestion.

Results

Two mutations were observed in different families (Family 4 and Family 10), one is a new mutation (Y56X) in CRYGD and the other a previously reported mutation (R12C) in CRYAA that is correlated with a different phenotype. Genetic analysis revealed previously described polymorphisms in CRYAA (D2D) and CRYGD (Y17Y and R95R). A new polymorphism in CRYGC (S119S) was identified only in Family 1. The mutations as well as the new polymorphism were not observed in the control group.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report a novel nonsense mutation (Y56X) in CRYGD and a previously reported missense mutation (R12C) in CRYAA associated with nuclear cataract in Brazilian families. Both tyrosine in amino acid 56 in CRYGD and arginine in amino acid 12 in CRYAA have been highly conserved throughout evolution in different species. A new polymorphism (S119S) in CRYGC was also observed in one family. The analysis of nine families excluded possible mutations in the crystallin genes, suggesting that other genes could be involved with congenital cataract.

Introduction

Congenital cataract is the leading cause of reversible blindness in childhood. Its occurrence, depending on the regional socioeconomic development, is 1−6 cases per 10,000 live births in industrialized countries [1,2] and 5−15 per 10,000 in the poorest areas of the world [3,4]. Congenital cataract is visible at birth or during the first decade of life [5]. About 20,000−40,000 new cases of bilateral congenital cataract are diagnosed each year [3,6]. In Brazil, congenital cataract accounts for 12.8% of cases of blindness in childhood [7] due to different causes including metabolic disorders (galactosemia) [8], infections during embryogenesis [1], gene defects, and chromosomal abnormalities [9,10]. Cataract may be an isolated anomaly or part of a multisystem syndrome such as Down syndrome, Wilson’s disease, and myotonic dystrophy [11]. Inherited cataracts correspond to 8%−25% of congenital cataracts [12]. Although X-linked and autosomal recessive transmission has been observed, the most frequent mode of inheritance is autosomal dominant with a high degree of penetrance [13,14]. Inherited cataracts are clinically highly heterogeneous and show considerable interfamilial and intrafamilial variability [15].

Congenital cataracts are also genetically heterogeneous [14]. It is known that different mutations in the same gene can cause similar cataract patterns while the highly variable morphologies of cataracts within some families suggest that the same mutation in a single gene can lead to different phenotypes [15,16]. To date, more than 25 loci and genes on different chromosomes have been associated with congenital cataract [17]. Mutations in distinct genes that encode the main cytoplasmic proteins of human lens have been associated with cataracts of various morphologies [18] including genes encoding crystallins (CRYA, CRYB, and CRYG) [19], lens specific connexins (Cx43, Cx46, and Cx50) [20,21], aquaporin (MIP) [22], cytoskeletal structural proteins (beaded filament structural protein 2 [BFSP2]) [23], paired-like homeodomain 3 (PITX3) [24], avian musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (MAF) [25], and heat shock transcription factor 4 gene (HSF4) [26]. Crystallin proteins (α-, β-, and γ-crystallins) represent more than 90% of lens soluble proteins in humans, encompassing almost 35% of its mass and accounting for its optical transparency and high refractive index [6,13].

Mutations in the crystallin genes represent a large proportion of the mutations identified to date. These genes may be divided into two distinct evolutionary groups comprising α-crystallins, which are members of the small heat shock family of molecular chaperones [27], and β/γ-crystallins, which share a common two domain structure composed of Greek-key motifs and belong to the family of epidermis specific differentiation proteins [28].

Lamellar and nuclear congenital cataracts are the most common types of hereditary congenital cataract [29,30]. Several genes have been associated with the presence of these two types of cataracts (CRYAA, CRYBA3/A1, CRYGC, CRYGD, CRYGS, connexin 46 [GJA3], and connexin 50 [GJA8]) [13,18,31]. In this study, CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD were considered as candidates for congenital cataract on the basis of both their high levels of expression in the lens and their known function in maintaining lens transparency. Eleven Brazilian families with autosomal dominant nuclear or lamellar congenital cataracts were screened for mutations in CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD.

Methods

The study protocols adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committees of the Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medicine (São Paulo, Brazil).

Patients and control group

Families with a positive history of autosomal dominant bilateral nuclear or lamellar cataract were investigated at Santa Casa de São Paulo Ophthalmology Department. Both affected and unaffected individuals underwent detailed ophthalmic examination including Snellen visual acuity and corrected visual acuity in addition to slit-lamp and fundus examination with dilated pupil, intraocular pressure measurement by applanation tonometry, and corneal diameter. Detailed ocular, medical, and family histories were obtained from each available family member. Probands with a history suggestive of an intrauterine infection such as rubella, unilateral cataract, and other ocular or systemic disorders were excluded from the study. There was no evidence of systemic abnormalities associated with congenital cataract in the probands. After informed consent was obtained from all participating individuals, 5–10 ml of venous blood was collected for genomic DNA extraction and subsequent molecular genetic analysis. Possible mutations and new polymorphisms were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion in the control group, which was comprised by 50 ophthalmologically normal, unrelated Brazilian individuals from Santa Casa de São Paulo Ophthalmology Department with the same ethnic background and from the same geographic region of the affected group.

Polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify all the exons and intron/exon boundaries of the candidate genes (CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD). Conditions are described as follows: a 25 μl reaction volume included approximately 100 ng of genomic DNA, 20 pmol of each primer, 1X enzyme buffer (10X buffer=20mM Tris-HCl [pH 8,4] 50 mM KCl, 0,01% gelatin), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM nucleotides (dATP, dCTP, dTTP, dGTP), 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen™ Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and sterile deionized water. Samples were amplified on the MasterCycler EP Gradient S thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) according to the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, X °C for 1 min, 72 °C for 1 min, and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Oligonucleotide primer pairs, PCR product sizes, and annealing temperatures are described in Table 1. Only the proband of each family has been screened for mutations in the candidate genes.

Table 1. Oligonucleotides used as primers for PCR amplification of the CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD, product sizes, and annealing temperatures.

| Gene | Exon | Strand | Sequence (5′→3′) | Product Size (bp) | T (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CRYAA |

1 |

Sense |

CACGCCTTTCCAGAGAAATC |

466 |

59 |

| |

|

Antisense |

CTCTGCAAGGGGATGAAGTG |

||

| |

2 |

Sense |

CTTGGTGTGTGGGAGAAGAGG |

377 |

57 |

| |

|

Antisense |

TCCCTCTCCCAGGGTTGAAG |

||

| |

3 |

Sense |

CCCCCTTCTGCAGTCAGT |

989 |

66 |

| |

|

Antisense |

GCTTGAGCTCAGGAGAAGGA |

||

|

CRYGC |

1–2 |

Sense |

ACCAGAGAACAAGGACACAATC |

674 |

62 |

| |

|

Antisense |

TGGCTTATTCAGGTCTCTGATG |

||

| |

3 |

Sense |

ATTCCATGCCACAACCTACC |

590 |

62 |

| |

|

Antisense |

CCAACGTCTGAGGCTTGTTC |

||

|

CRYGD |

1–2 |

Sense |

CCCTTTTGTGCGGTTCTTG |

596 |

58 |

| |

|

Antisense |

TTTGTCCACTCTCAGTTATTGTGAC |

||

| |

3 |

Sense |

TGTGCTCGGTAATGAGGAG |

700 |

62 |

| Antisense | AGGCCAGAGAATCAAATGAG |

PCR products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gels containing 0.05% ethidium bromide, purified, and submitted to direct sequencing on the ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequencing reactions were performed under the following conditions: 25 cycles of 96 °C for 10 s, 56 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 4 min, using Big Dye Terminator Ready Reaction v3.1 (ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit; Applied Biosystems). Sequencing results were analyzed through submission to similarity search using the “search algorithm” BLAST. Any sequence variation suggestive of a mutation was later confirmed in parents and available relatives to determine the segregation with the disease.

Restriction digestion

Genetic variations were evaluated in the control group by the presence/absence of cleavage sites for the restriction enzymes HhaI for CRYAA, MslI for CRYGC, and RsaI for CRYGD (New England BioLabs, Ipswith, MA). Digestions were conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. The resulting restriction fragments were separated in 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and analyzed under ultraviolet (UV) light.

Computational methods

Besides the analysis of the control group, computational algorithms were used to predict which variants were deleterious and which were neutral. Three methods were used to determine if a specific amino acid substitution within a protein sequence might lead to altered protein function and possibly contribute to the disease. Automated methods available on the Internet were used: Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant amino acid substitutions (SIFT), Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen), and Grantham score difference (Align-GVGD).

SIFT uses an evolutionary approach and is based on the assumption that important amino acids tend to be conserved across species. SIFT assigns a substitution probability from 0 to 1 for each possible amino acid change. Substitution with probabilities less than 0.05 are considered intolerant (i.e., functionally significant) whereas those greater than or equal to 0.05 are inferred as tolerated substitutions. PolyPhen takes into account not only the evolutionary conservation of the amino acid subjected to the mutation but also the physico-chemical characteristics of the wild type and mutated amino acid residue and the consequence of the amino acid change for the structural properties of the protein. Align-GVGD is based on chemical differences between each amino acid pair, polarity, and molecular volume. The matrix of scores varies from a minimum of 15 to a maximum of 215. Deleterious mutations tend to have scores greater than 100 and tolerated variations scores less than 60 [32,33].

Results

Eleven families with autosomal dominant childhood cataracts were identified, seven families presenting with the nuclear phenotype and the remaining families with the lamellar phenotype (Table 2). A total of 34 affected members and 44 unaffected members were evaluated in this study.

Table 2. Cataract phenotypes, mutations, and polymorphisms identified in this study.

| Family ID | Cataract phenotype |

Mutation |

Polymorphism |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRYAA | CRYGC | CRYGD | CRYAA | CRYGC | CRYGD | ||

| Family 1 |

Nuclear+Microcornea |

|

|

|

D2D |

S119S |

Y17Y, R95R |

| Family 2 |

Lamellar |

|

|

|

D2D |

|

R95R |

| Family 3 |

Nuclear |

|

|

|

D2D |

|

Y17Y, R95R |

| Family 4 |

Nuclear |

R12C |

|

|

D2D |

|

R95R |

| Family 5 |

Lamellar |

|

|

|

D2D |

|

R95R |

| Family 6 |

Lamellar |

|

|

|

|

|

Y17Y, R95R |

| Family 7 |

Nuclear |

|

|

|

D2D |

|

Y17Y, R95R |

| Family 8 |

Nuclear+Microcornea |

|

|

|

D2D |

|

Y17Y, R95R |

| Family 9 |

Nuclear |

|

|

|

D2D |

|

|

| Family 10 |

Nuclear |

|

|

Y56X |

D2D |

|

Y17Y, R95R |

| Family 11 | Lamellar | D2D | Y17Y | ||||

The degree of opacification of lamellar cataracts showed some variability among families. Families 6 and 11 presented with lamellar cataracts significantly less dense than those in Families 2 and 5.

Mutations were observed in two families (18.2%). In nine families, no mutation in CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD was detected. The cataract phenotypes in families without mutations were bilateral nuclear cataract since birth in affected members from Families 1, 3, 7, 8, and 9 and bilateral lamellar in affected members from Families 2, 5, 6, and 11.

The proband of Family 8 who is of consanguineous origin presented with nuclear cataract and microcornea like the affected father and mother. The father had retinal detachment in both eyes after cataract surgery and the mother postoperative glaucoma. In Family 1, all affected members also had nuclear opacity and microcornea. This family comprised of 8 affected and 24 unaffected members spanning four generations. The visual acuity of the proband was 20/40 in both eyes after cataract surgery. Nystagmus was present in some families and absent in others, depending primarily on the degree of visual impairment during the first months of life.

Mutations in CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD associated with human cataract

In 2 of the 11 probands (from Families 4 and 10), unique mutations in one of the three genes were identified cosegregating in a heterozygous condition with the disease in the each family. In both families, the congenital bilateral nuclear cataract was present in all affected individuals.

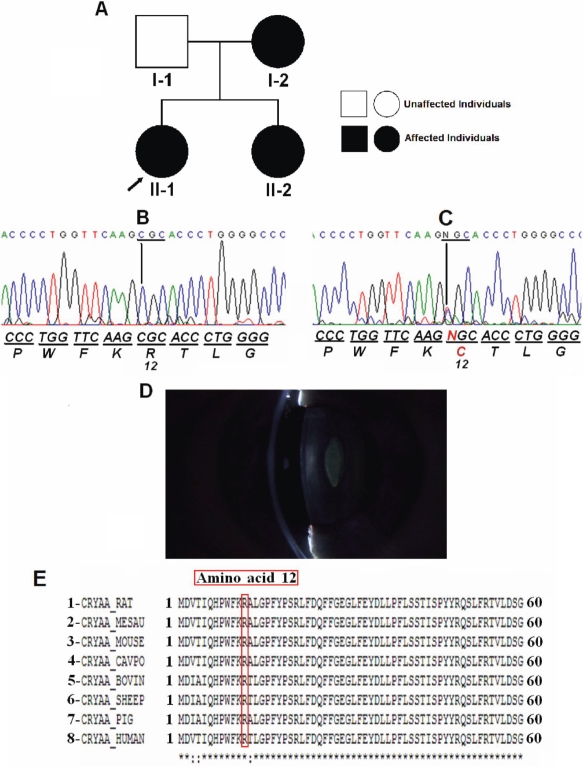

Family 4 comprised of two generations with three affected members and one unaffected member (Figure 1). Visual acuity of the affected eyes ranged from 20/80 to counting fingers after cataract surgery. In all cases, there was amblyopia. The congenital bilateral nuclear cataract in this family is associated with a mutation in CRYAA, a point mutation in exon 1 (CGC>TGC), which leads to the replacement of an arginine at position 12 for a cysteine (R12C). This mutation was observed in all affected members (I-2, II-1, and II-2) and was not observed in the unaffected member (I-1). There was no evidence of other ocular or systemic abnormalities. This substitution resulted in the loss of a HhaI restriction site. Wild type control PCR products were digested into fragments of 286 bp, 96 bp, and 84 bp while the presence of the R12C mutation resulted in an undigested fragment of 382 bp as well as a common 84 bp fragment. Restriction digestion of 50 normal controls did not detect the mutation.

Figure 1.

Mutation analysis of CRYAA in Family 4. A: Pedigree of Family 4 shows the proband, which is indicated by the arrow. B: Direct sequencing of the PCR product encompasses exon 1 of CRYAA (5′→3′) of an unaffected individual (I-1). C: Direct sequencing of the PCR product encompassing exon 1 of CRYAA of an affected individual (II-1) shows a heterozygous C→T transition that replaced arginine by cysteine at amino acid 12 (R12C). The mutated sequence is shown in red. D: The slit-lamp photograph of individual I-2 shows a nuclear cataract. E: Alignment of residues 1–60 of human (8) αA-crystallin protein with rat (1), hamster (2), mouse (3), guinea pig (4), cow (5), sheep (6), pig (7) is shown. The R12 residue is marked in red.

Computational program analysis of the R12C mutation revealed the following results: in the PolyPhen the score was 2.664, which means with high confidence that this variant is predicted to be “probably damaging.” Align-GVGD showed a score of 179.53 when “deleterious” mutations tend to have scores greater than 100. Finally, the SIFT method revealed a score of 0.00 to position R12. Positions with a probability less than 0.05 are predicted to be intolerant.

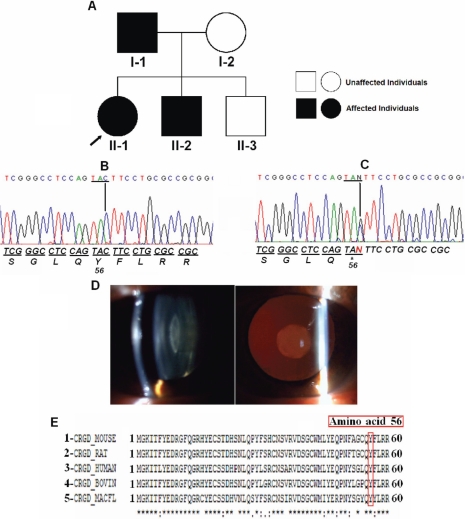

The proband of Family 10 was diagnosed with congenital nuclear cataract. DNA sequencing analysis of CRYGD showed a novel heterozygous nonsense mutation (TAC>TAG) within the second exon (Figure 2). Cataract was most likely caused by this point mutation that leads to the replacement of a tyrosine by a premature stop codon at position 56 (Y56X).This mutation was observed in the proband (II-1), her affected father (I-1), and affected brother (II-2). The unaffected mother and the unaffected other brother did not show this mutation. On clinical examination, the affected members achieved a visual acuity of 20/40 in both eyes (I-1, II-2) as well as 20/50 and counting fingers in the right eye and left eye, respectively, of the proband. No other ocular findings were observed. This transition resulted in the loss of an RsaI restriction site, generating fragments of 396 bp, 108 bp, and 92 bp for the wild type allele and fragments of 488 bp, 396 bp, 108 bp, and 92 bp for the mutant allele. The analysis of 50 normal controls did not detect the substitution.

Figure 2.

Mutation analysis of CRYGD in Family 10. A: Pedigree of Family 10 shows the proband, which is indicated by the arrow. B: Direct sequencing of the PCR product encompasses exon 2 of CRYGD of an unaffected individual (I-2). C: Direct sequencing of the PCR product encompassing exon 2 of CRYGD shows a heterozygous TAC>TAG transition that replaced a tyrosine by a premature stop codon at amino acid 56 (Y56X) in individual II-1. D: The photograph of the anterior eye with lens image of individual II-1 shows nuclear cataract. E: Multiple alignment of amino acid sequence of γD-crystallin protein with different species is shown: mouse (1), rat (2), human (3), cow (4), and kangaroo (5). The Y56 residue is marked in red.

Polymorphisms in CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD

A variety of sequence variations referred as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was observed in the probands for CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD. None of these sequence changes in the coding regions led to amino acid alterations. Three known polymorphisms [34-36] were observed in the sequencing analysis, D2D (rs872331) polymorphism (GAC>GAT) in CRYAA (exon 1), which was observed in 10 probands; Y17Y (rs2242074) polymorphism (TAT>TAC) in CRYGD (exon 2), which was observed in seven probands; and R95R (rs2305430) polymorphism (AGA>AGG) in CRYGD (exon 3), which was observed in nine probands. A new polymorphism in the third exon of CRYGC (S119S) was observed in Family 1. This alteration (AGC>AGT) resulted in the gain of a novel MslI restriction site, producing fragments of 387 bp and 203 bp while the wild type allele showed a fragment of 590 bp. Fourteen members of the family (seven affected members and seven unaffected members) were analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion. This polymorphism was observed in the heterozygous state in five affected members, and it was not detected in the unaffected individuals. Digestion analysis of 50 healthy unrelated individuals also did not detect the substitution.

Discussion

The transparency and high refractive index of the lens are achieved by the precise architecture of the fiber cells and the homeostasis of the lens proteins in terms of their concentration, stability, and supramolecular organization [6]. Pras et al. [37] estimated that approximately 30 loci are involved in autosomal dominant human congenital cataract. Different crystallin genes have been recognized as the main candidates for certain hereditary forms of lens opacity in humans [12].

In this study, we identified a mutation in the first exon of CRYAA (R12C) in Family 4. The affected family members presented with nuclear cataract and had no other ocular defects. Since this mutation segregates with the disease within this family and could not be detected in 50 controls, we consider this allele as the probable causative molecular lesion for the observed clinical findings. The abnormal protein produced for this heterozygous mutation may precipitate in the lens and therefore induce the precipitation of other proteins [37]. During the course of this study, the same R12C substitution was independently associated with congenital central, zonular cataract with microcornea in a Danish family [21]. The difference between the phenotype reported in this Danish family and that observed in our Brazilian family may be related to the effect of an unknown modifier gene or to sequence variation within the regulatory region that could affect the expression of CRYAA. Previous studies have already reported phenotypic heterogeneity of the disease with the same mutation in CRYAA [38].

The αA-crystallins belong to the small heat shock protein family and function as chaperones. They all share a common structure of an NH2-terminal less-conserved region, a conserved α-crystallin domain, and a short COOH-terminal. Molecular chaperones facilitate the correct folding of proteins in vivo and are of extreme importance in keeping these proteins properly folded and in a functional state [39].

The R12C mutation is located in the NH2-terminal portion, and the alignment of the primary sequence for small heat shock proteins from plants, bacteria, and mammals, including human CRYAA, demonstrate that the arginine residue is highly conserved at this position. The conserved αA-crystallin domain region may be involved in aggregation and disaggregation of larger protein complexes whereas the NH2-terminal and the COOH-terminal regions might play a role in oligomerization [40]. Astonishingly, all dominant mutations reported in CRYAA have the basic amino acid arginine involved. Thus, this residue probably has a very important role in maintaining the structural integrity of the lens [41].

We evaluated the likely effect of amino acid substitution (R12C) on αA-crystallin protein function using PolyPhen, SIFT, and Align-GVGD computational programs. Chan and colleagues [32] demonstrated that the isolated predictive value of these programs can be increased by their combination. These programs predict the possible deleterious effect of an amino acid variant on the structure and function of a protein based on sequence homology and structural information. Significantly, all three different algorithms considered the R12C mutation as possibly damaging to the αA-crystallin protein.

Molecular analysis of CRYGD of the affected members of Family 10 showed a novel heterozygous nonsense mutation in exon 2 (TAC>TAG). This mutation resulted in the substitution of the tyrosine residue 56 by a premature stop codon (Y56X), resulting in a truncated protein missing 118 amino acids.

An increasing number of mutations in CRYGD have been described in association with human congenital cataract [41]. Hansen et al. [21] related that the mechanisms through which protein abnormalities cause loss of lens transparency are still speculative. These truncated protein products may act by a dominant negative mechanism, giving rise to the cataract phenotypes in this family. The γ-crystallin proteins are a superfamily of proteins that have a Greek Key (GK) motif unit base [28]. They contain two domains, an NH2-terminal domain and a COOH-terminal domain as the core. Each domain contains two GK motifs. Each GK motif is composed of four antiparallel β-strands. The two domains are connected by a distinct connecting peptide [19]. Based on the crystal structure of human γD-crystallin, the Y56X substitution resulted in a complete absence of the COOH-terminal domain, leading to a major change in structural conformation of the protein. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that γD-crystallins have shown a strong tendency to maintain conservation throughout evolution in different species. The computational programs used in this study are not able to predict the impact of nonsense mutations on protein function. They only apply to missense mutations.

A new polymorphism in the third exon of CRYGC (S119S) was observed in Family 1. It was present in five of the seven affected individuals and absent in all unaffected individuals as well as in the control group. We might consider that it represents a rare polymorphism or that it may be exclusive of this sample of Brazilian patients. Another hypothesis is that this polymorphism could be a marker of an unidentified gene located in this region and that its absence in two of the affected individuals would be due to recombination events. This fact would make this four-generation family a target to the analysis of microsatellite markers surrounding the location of the polymorphism.

In conclusion, we report a novel nonsense mutation (Y56X) in CRYGD and a previously reported missense mutation (R12C) in CRYAA associated with nuclear cataract in Brazilian families. Additionally, we also observed a new polymorphism (S119S) in CRYGC. The analysis of the remaining nine families reported here excluded possible mutations in CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD, suggesting that other genes/loci could be involved with congenital nuclear/lamellar cataract.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the participating families. This study was supported by CAPES and FAP-SCSP (Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medicine, São Paulo, Brazil).

References

- 1.Rahi JS, Sripathi S, Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in India: causes in 1318 blind school students in nine states. Eye. 1995;9:545–50. doi: 10.1038/eye.1995.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020 - The right to sight. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:227–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apple DJ, Ram J, Foster A, Peng Q. Elimination of cataract blindness: a global perspective entering the new millennium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:S1–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis PJ, Berry V, Bhattacharya SS, Moore AT. The genetics of childhood cataract. J Med Genet. 2000;37:481–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.7.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marner E, Rosenberg T, Eiberg H. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Morphology and genetic mapping. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1989;67:151–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1989.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graw J. Cataract mutations and lens development. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18:235–67. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haddad MAO, Lobato FJC, Sampaio MW, Kara-José N. Pediatric and adolescent population with visual impairment: study of 385 cases. Clinics. 2006;61:239–46. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322006000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merin S, Crawford JS. The etiology of congenital cataract. A survey of 386 cases. Can J Ophthalmol. 1971;6:178–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckstein M, Vijayalakshmi P, Killerdar M, Gilbert C, Foster A. Aetiology of childhood cataract in south India. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:628–32. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.7.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zetterstrom C, Lundvall A, Kugelberg M. Cataracts in children. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:824–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He W, Li S. Congenital cataracts: gene mapping. Hum Genet. 2000;106:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s004390051002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Messina-Baas OM, Gonzalez-Huerta LM, Cuevas-Covarrubias SA. Two affected siblings with nuclear cataract associated with a novel missense mutation in the CRYGD gene. Mol Vis. 2006;12:995–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beby F, Morle L, Michon L, Bozon M, Edery P, Burillon C, Denis P. The genetics of hereditary cataract. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2003;26:400–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott MH, Hejtmancik JF, Wozencraft LA, Reuter LM, Parks MM, Kaiser-Kupfer MI. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Interocular phenotypic variability. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:866–71. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill D, Klose R, Munier FL, McFadden M, Priston M, Billingsley G, Ducrey N, Schorderet DF, Heon E. Genetic heterogeneity of the Coppock-like cataract: a mutation in CRYBB2 on chromosome 22q11.2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heon E, Priston M, Schorderet DF, Billingsley GD, Girard PO, Lubsen N, Munier FL. The gamma-crystallins and human cataract: a puzzle made clearer. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1261–7. doi: 10.1086/302619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guleria K, Sperling K, Singh D, Varon R, Singh JR, Vanita V. A novel mutation in the connexin 46 (GJA3) gene associated with autosomal dominant congenital cataract in an Indian family. Mol Vis. 2007;13:1657–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hejtmancik JF, Smaoui N. Molecular genetics of cataract. Dev Ophthalmol. 2003;37:67–82. doi: 10.1159/000072039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhat SP. Crystallins, genes and cataract. Prog Drug Res. 2003;60:205–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-8012-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodenough DA. The crystalline lens. A system networked by gap junctional intercellular communication. Semin Cell Biol. 1992;3:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4682(10)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen L, Yao W, Eiberg H, Kjaer KW, Baggesen K, Hejtmancik JF, Rosenberg T. Genetic heterogeneity in microcornea-cataract: five novel mutations in CRYAA, CRYGD, and GJA8. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3937–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry V, Francis P, Kaushal S, Moore A, Bhattacharya S. Missense mutations in MIP underlie autosomal dominant “polymorphic” and lamellar cataracts linked to 12q. Nat Genet. 2000;25:15–7. doi: 10.1038/75538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakobs PM, Hess JF, FitzGerald PG, Kramer P, Weleber RG, Litt M. Autosomal-dominant congenital cataract associated with deletion mutation in the human beaded filament protein gene BFSP2. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1432–6. doi: 10.1086/302872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semina EV, Ferrell RE, Mintz-Hittner HA, Bitoun P, Alward WL, Reiter RS, Funkhauser C, Daack-Hirsch S, Murray JC. A novel homeobox gene PITX3 is mutated in families with autosomal-dominant cataract and ASMD. Nat Genet. 1998;19:167–70. doi: 10.1038/527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanita V, Singh D, Robinson PN, Sperling K, Singh JR. A novel mutation in the DNA-binding domain of MAF at 16q23–1 associated with autosomal dominant “cerulean cataract” in an Indian family. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:558–66. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forshew T, Johnson CA, Khaliq S, Pasha S, Willis C, Abbasi R, Tee L, Smith U, Trembath RC, Mehdi SQ, Moore AT, Maher ER. Locus heterogeneity in autosomal recessive congenital cataracts: linkage to 9q and germline HSF4 mutations. Hum Genet. 2005;117:452–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Augusteyn RC. Alpha-crystallin: a review of its structure and function. Clin Exp Optom. 2004;87:356–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2004.tb03095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blundell T, Lindley P, Miller L, Moss D, Slingsby C, Tickle I, Turnell B, Wistow G. The molecular structure and stability of the eye lens: x-ray analysis of gamma-crystallin II. Nature. 1981;289:771–7. doi: 10.1038/289771a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amaya L, Taylor D, Russell-Eggitt I, Nischal KK, Lengyel D. The morphology and natural history of childhood cataracts. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:125–44. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00462-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forster JE, Abadi RV, Muldoon M, Lloyd IC. Grading infantile cataracts. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2006;26:372–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2006.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy MA, Francis PJ, Berry V, Bhattacharya SS, Moore AT. Molecular genetic basis of inherited cataract and associated phenotypes. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:300–15. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan PA, Duraisamy S, Miller PJ, Newell JA, McBride C, Bond JP, Raevaara T, Ollila S, Nyström M, Grimm AJ, Christodoulou J, Oetting WS, Greenblatt MS. Interpreting missense variants: comparing computational methods in human disease genes CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH2, MECP2, and tyrosinase (TYR). Hum Mutat. 2007;28:683–93. doi: 10.1002/humu.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Min JL, Meulenbelt I, Kloppenburg M, Van Duijn CM, Slagboom PE. Mutation analysis of candidate genes within the 2q33.3 linkage area for familial early-onset generalized osteoarthritis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:791–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hattori M, Fujiyama A, Taylor TD, Watanabe H, Yada T, Park HS. The DNA sequence of human chromosome 21. Nature. 2000;405:311–9. doi: 10.1038/35012518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hillier LW, Graves TA, Fulton RS, Fulton LA, Pepin KH, Minx P. Generation and annotation of the DNA sequences of human chromosomes 2 and 4. Nature. 2005;434:724–31. doi: 10.1038/nature03466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santhiya ST, Manisastry SM, Rawlley D, Malathi R, Anishetty S, Gopinath PM, Vijayalakshmi P, Namperumalsamy P, Adamski J, Graw J. Mutation analysis of the congenital cataracts in Indian families: identification of SNPs and a new causative allele in CRYBB2 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3599–607. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pras E, Frydman M, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Bakhan T, Raz J, Assia EI, Goldman B, Pras E. A nonsense mutation (W9X) in CRYAA causes autosomal recessive cataract in an inbred Jewish Persian family. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3511–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devi RR, Yao W, Vijayalakshmi P, Sergeev YV, Sundaresan P, Hejtmancik JF. Crystallin gene mutations in Indian families with inherited pediatric cataract. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1157–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar LV, Ramakrishna T, Rao CM. Structural and functional consequences of the mutation of a conserved arginine residue in alphaA and alphaB crystallins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24137–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamler R, Kappé G, Boelens W, Slingsby C. Wrapping the alpha-crystallin domain fold in a chaperone assembly. J Mol Biol. 2005;353:68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santhiya ST, Soker T, Klopp N, Illig T, Prakash MV, Selvaraj B, Gopinath PM, Graw J. Identification of a novel, putative cataract – causing allele in CRYAA (G98R) in an Indian family. Mol Vis. 2006;12:768–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]