Abstract

Objective To identify modifiable factors that influence relatives’ decision to allow organ donation.

Design Systematic review.

Data sources Medline, Embase, and CINAHL, without language restriction, searched to April 2008.

Review methods Three authors independently assessed the eligibility of the identified studies. We excluded studies that examined only factors affecting consent that could not be altered, such as donor ethnicity. We extracted quantitative results to an electronic database. For data synthesis, we summarised the results of studies comparing similar themes.

Results We included 20 observational studies and audits. There were no randomised controlled trials. The main factors associated with reduced rates of refusal were the provision of adequate information on the process of organ donation and its benefits; high quality of care of potential organ donors; ensuring relatives had a clear understanding of brain stem death; separating the request for organ donation from notification that the patient had died; making the request in a private setting; and using trained and experienced individuals to make the request.

Conclusions Limited evidence suggests that there are modifiable factors in the process of requests for organ donation, in particular the skills of the individual making the request and the timing of this conversation, that might have a significant impact on rates of consent. Targeting these factors might have a greater and more immediate effect on the number of organs for donation than legislative or other long term strategies.

Introduction

Solid organ transplantation is an integral part of modern health care. It is, however, a victim of its own success as demand for organs now far exceeds supply. In the past decade the number of patients waiting for solid organs has increased by 70%,w1 while the number of organ donors has not significantly increased. Every day in the United Kingdom about one patient on a transplant waiting list dies.1

The greatest identified impediment to organ donation from patients after brain stem death on an intensive care unit in the UK is refusal of consent by the relatives of the donor.2 3 4 w2 A recent audit of all deaths in 341 intensive care units in the UK over a 33 month period showed that 41% of the relatives of potential organ donors refused to consent to donation.1

Although the Human Tissue Act 2004,5 which came into force in 2006, prioritises the wishes and consent of the potential donor over the relatives, it is almost inconceivable that organs would be retrieved from a brain stem dead patient against the wishes of his or her family. Thus requests to relatives for organ donation are likely to remain an important step in organ procurement.

Interviews with the relatives of brain stem dead patients have shown that about a third of those who refused donation would not make the same decision again,w3 whereas few consenting relatives regretted their decision, suggesting that many decisions to refuse to allow donation are not based on deeply held religious or other views, and that there might be factors in the way the request for donation is made that could change the decision. Identifying these factors, and making this information available to intensive care clinicians and transplant professionals, might have a greater and more immediate effect than any legislation. We reviewed published peer reviewed studies to identify any modifiable factors in the request for organ donation that might increase consent rates.

Methods

Searching—On 8 May 2008 we searched Medline (from 1950), Embase (from 1980), and CINAHL (from 1982) using the OVID database search programme (http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/spb/ovidweb.cgi). We used the search terms “organ” or “tissue” and “don*” or “consent” in the title or abstract and limited the search to humans without language restrictions. These terms were finalised after trial searches undertaken to maximise the number of citations found and to ensure that we detected all relevant citations known to us before searching. We deliberately kept the search terms broad to avoid losing potentially important papers. We hand searched reference lists of included studies to identify other potentially relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria—We included studies that reported factors associated with the consent outcome of a request for organ donation to the relatives of a beating heart potential organ donor (a patient meeting the criteria for brain stem death). We included studies looking at both child and adult organ donors, regardless of the original publication language. We included all studies containing data, whether from observational or interventional studies. We excluded studies if they examined factors affecting consent that we deemed unmodifiable (for example, religious, cultural, geographical, and ethnic influences) or if they looked at other reasons for the disparity between potential and actual donors (for example, incomplete neurological assessment of patients and medical unsuitability of some consented donors). We also excluded narrative pieces without data to support observations.

Validity assessment and data abstraction—Three authors (ALS, LCR, VSB) screened the obtained titles and abstracts for eligibility. We excluded papers first on title, then abstract, and finally on full text. When studies seemed to meet eligibility criteria (or when information was insufficient to exclude them), we obtained the full text articles. We extracted any quantitative results to an electronic database.

Data synthesis—As the identified papers did not contain data suitable for meta-analysis, we reviewed them to identify all the modifiable factors associated with agreement or refusal of consent. Common themes emerged so we report the results in narrative form under thematic headings.

Results

Trial flow

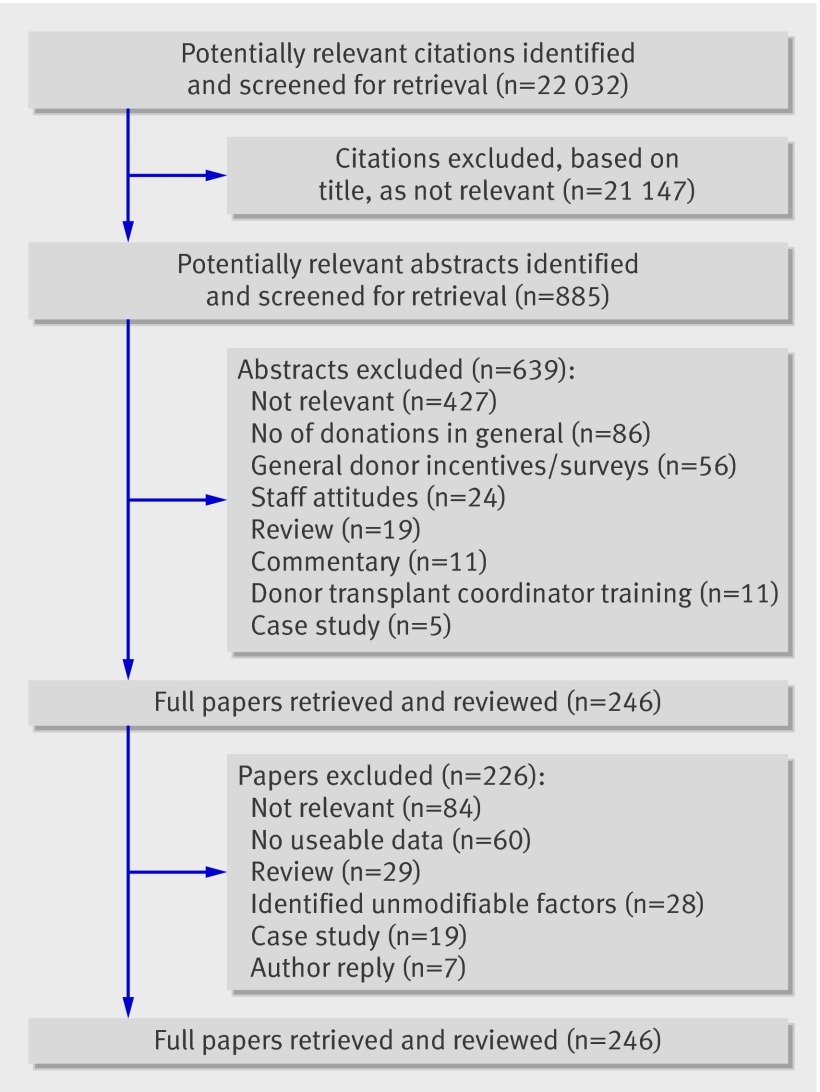

Database searching produced a list of 22 032 publications. Of these, we excluded 21 147 using information in the title alone and 639 using information in the abstract. We reviewed 246 full papers (figure). No further papers were identified from the reference lists of these papers. After we excluded 226 papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria, we included 20 studies in the review.w1-w20

Review flow chart

Study characteristics

The studies identified were of two types. In observational studies the proportion of successful requests for organ donation was determined when the factor was present and compared with the proportion when it was not. In “before and after” audits the factor was modified and the effect on subsequent organ donation noted. We did not identify any randomised controlled trials. One study included data from a previous publication.w12 w13 Two studies reported data collected from the same hospitals over the same period with near identical record numbers, though no mention was made of duplicate publication.w1 w20

Data synthesis

We identified modifiable factors that apparently influence relatives’ decisions to allow organ donation in six broad categories: information discussed during the request; perceived quality of care of the donor; understanding of brain stem death; specific timing of the request; setting in which the request is made; and approach and expertise of the individual making the request. Many of the papers report multiple factors and thus appear under several headings. We present all the modifiable factors identified in studies with a P value of ≤0.05 for differences in the observed proportion of relatives giving consent to organ donation with the factor present or absent. We also present modifiable factors for which no statistical results were reported but which the authors considered relevant.

Information discussed during request

Five studies retrospectively collected data via chart reviews and interviews with staff and families in an attempt to establish whether information provided during the request process was associated with the family’s decision to donate or not donate organs for transplantation (table 1).w1 w3 w5 w18 w20 Siminoff et al studied 420 donor eligible patients.w1 w20 Factors correlating with consent to organ donation were delivery of information on the costs of donation; the impact of donation on funeral arrangements; and assurances that the family had a choice about which organs to donate. When healthcare professionals mentioned that donation had the potential to help others, families were also more likely to donate, but telling families that they were required to ask about donation had a negative impact on consent rates.w1 The other papers showed a significantly higher rate of consent when families thought they had been given enough information to make an informed decision about organ donation,w3 w5 w18 w20 in particular understanding that a regular funeral service is still possible after organ donation.w3

Table 1.

Studies showing association between information discussed during request for organ donation and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor was present or not, unless stated otherwise

| Study | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| Siminoff et al,w1 2001, US | 420 | Retrospective data collection via chart reviews, and telephone interviews with healthcare practitioners or organ procurement organisation (OPO) staff, and face to face interviews with family for all donor eligible deaths | Cost of donation; impact of donation on funeral arrangements; assurances that family had choice about which organs to donate | NA | NA | <0.002 (across groups) |

| Mean No of discussions regarding organ donation | 2.4 | 2 | ||||

| Told family that they were required to ask about donation | 44 | 62* | ||||

| Told family of potential to help others | 72 | 39* | ||||

| DeJong et al,w3 1998, US | 164 | Structured telephone interview with immediate next of kin 4-6 months after death of relative | Family thought that they were given enough information to make informed decision about organ donation | 95 | 67 | <0.01 |

| Family aware of needs based organ allocation | 44 | 24 | <0.02 | |||

| Family aware of benefits of donation | 93 | 68 | <0.01 | |||

| Family aware donation is cost neutral | 83 | 50 | <0.01 | |||

| Family understood that regular funeral service was possible after organ donation | 92 | 73 | <0.001 | |||

| Rosel et al,w5 1999, Spain | 71 | Postal survey sent to all families who had been approached for organ donation at single hospital within 12 month period | Family aware of needs based organ allocation | NA | NA | <0.01 |

| Rodrigue et al,w4 2003, US | 1014 | Structured telephone interview with next of kin | Families thought enough information given | 89 | 56 | <0.001 |

| Families thought information presented clearly | 89 | 73 | <0.001 | |||

| Siminoff et al,w20 2002, US | 420 | Retrospective data collection via chart reviews, telephone, and face to face interviews | Families thought enough information discussed | 65 | 41 | 0.001 |

NA=not available (data not given); OPO=organ procurement organisation.

*Calculated from published data.

Perceived quality of care of donor

Perceived quality of care during the hospital stay had a significant impact on consent rates in the three papers that examined this (table 2).w1 w3 w4 All three papers showed that a negative perception of care results in a decreased rate of consent.

Table 2.

Studies showing association between perceived quality of care of potential organ donor and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor was present or not

| Study | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| Siminoff et al,w1 2001, USA | 420 | Retrospective data collection via chart reviews and telephone interviews with healthcare practitioners or OPO staff, and face to face interviews with family for all donor eligible deaths | Families believed that one or more healthcare professional involved in relatives’ care was not caring or concerned | 43 | 59* | 0.04 |

| DeJong et al,w3 1998, US | 164 | Structured telephone interview with immediate next of kin 4-6 months after death of relative | Perceptions of overall quality of care delivered in hospital (scale devised; score >5) | 82 | 48 | <0.01 |

| Thought relative had received best possible care before death | 92 | 70 | <0.001 | |||

| Rodrigue et al,w4 2006, US | 285 | Retrospective structured telephone interview with next of kin of donor eligible dead individuals | Overall satisfaction with care received higher for next of kin who consented to donation | 45 | 39 | <0.001 |

OPO=organ procurement organisation.

*Calculated from published data.

Understanding of brain stem death

In five papers there was a significant association between understanding and consent to organ donation,w1 w3-w6 with a sixth paper showing a non-significant increase in consent in families who understand brain stem death but a significant difference in consent rates in families accepting the concept of brain stem death (table 3).w19 In 71 families surveyed, 48 (68%) who did consent had a significantly better understanding of the concept of brain stem death than 23 (32%) who did not consent.w5 Similarly, in a review of 285 families, 71% that had complete knowledge of brain stem death agreed to donation compared with only 29% of those with incomplete or inaccurate knowledge of brain stem death.w4 When families were asked if they agreed that people cannot recover when they are brain dead, 80% of donor family respondents correctly agreed with this statement, while only 48% of the non-donor family group did so.w3 In a study by Jenkins et al a protocol that used a nuclear medicine brain flow scan to confirm brain stem death increased consent from 44% to 71%, perhaps because of its objective nature.w6

Table 3.

Studies showing association between relatives’ understanding of brain stem death and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor was present or not

| Study | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| Siminoff et al,w1 2001, US | 420 | Retrospective data collection via chart reviews, and telephone interviews with healthcare practitioners or OPO staff, and face to face interviews with family for all donor eligible deaths | Family believed patient had died when brain stem death was confirmed | 63 | 48* | 0.001 |

| DeJong et al,w3 1998, US | 164 | Structured telephone interview with immediate next of kin 4-6 months after death of relative | Family understood that people cannot recover when they are brain stem dead | 80 | 48 | <0.001 |

| Family understood someone is brain stem dead even though heart is still beating | 80 | 60 | <0.02 | |||

| Rodrigue et al,w4 2006, US | 285 | Retrospective structured telephone interview with next of kin of donor eligible deceased individuals | Adequate knowledge of brain stem death | 71 | 27* | <0.001 |

| Explanation of brain stem death given | 74 | 43* | <0.001 | |||

| Rosel et al,w5 1999, Spain | 71 | Postal survey sent to all families who had been approached for organ donation at single hospital within 12 month period | Understanding of brain stem death | NA | NA | <0.01 |

| Jenkins et al,w6 1998, US | NA | Before and after study after implementation of rapid brain death protocol | After rapid brain stem death protocol with nuclear medicine scan to confirm brain death consent rate increased | 71 | 44 | <0.01 |

| Frutos et al,w19 1998-2003, Spain | 268 | Family interview with families of possible donors accepted for transplant | Acceptance of brain stem death | 67 | 51 | 0.044 |

OPO=organ procurement organisation; NA=not available (data not given).

*Calculated from published data.

Timing of the request

A series of nine reports all suggested that there is an improved rate of consent when there is temporal separation (“decoupling”) between notification and acceptance of brain stem death and request for donation (table 4).w1 w2 w3 w4 w7-w9 w14 w18

Table 4.

Studies showing association between timing of request for organ donation and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor present or not

| Study | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| Siminoff et al,w1 2001, US | 420 | Retrospective data collection via chart reviews, and telephone interviews with healthcare practitioners or OPO staff, and face to face interviews with family for all donor eligible deaths | Organ donation mentioned while brain death tests conducted | 65 | 56* | 0.04 |

| DeJong et al,w3 1998, US | 164 | Structured telephone interview with immediate next of kin 4-6 months after death of relative | Subject of organ donation brought up after family given enough time to understand that relative was brain stem dead | 83 | 56 | <0.001 |

| Rodrigue et al,w4 2006, US | 285 | Retrospective structured telephone interview with next of kin of donor eligible deceased individuals | Relatives thought timing of request appropriate | 68 | 18* | <0.001 |

| Relatives thought they were given enough time to discuss donation | 60 | 27* | <0.001 | |||

| Niles et al,w9 1996, US | 127 | Retrospective study with data collection questionnaire | Organ donation requested before death | 62 | — | — |

| Organ donation requested after death | 57 | — | 0.07* | |||

| Organ donation requested at same time as family told of patient’s death | 25 | — | — | |||

| Gortmaker et al,w2 1998, US | 707 | Data collected prospectively for medically suitable potential donors referred to three organ procurement organisations | Request decoupled (not at same time as death notification) | 72 | 53 | <0.001 |

| von Pohle et al,w7 1996, US | 68 | Retrospective chart review | Request decoupled (not at same time as death notification) | 86 | 25 | <0.05 |

| Garrison et al,w8 1991, US | 155 | Retrospective review | Request decoupled (not at same time as death notification) | 65 | 18 | <0.05 |

| Evanisko et al,w14 1998, US | 1061 | Staff questionnaire | More respondents from hospitals with high donation rates (40.6%) than respondents from hospitals with low donation rates (30.0%) knew that appropriate time to bring up topic of organ donation was after brain death had been determined (decoupled); P=0.04 | — | — | — |

| Rodrigue et al,w18 2003, US | 1014 | Structured telephone interview with next of kin | Relatives felt pressured to donate | 2 | 6 | <0.001 |

| Relatives had enough time to decide | 86 | 58 | <0.001 | |||

OPO=organ procurement organisation.

*Calculated from published data.

The most important factor seems to be that the request for donation does not occur at the same time as the notification of death or testing for brain stem death. Niles and Mattice studied the timing in the approach process and determined that the consent rate was similar regardless of whether families were approached either before (62%) or after (57%) death but much lower when donation was mentioned at the time of the death notification (25%).w9 Siminoff et al showed a slightly different result, suggesting that requests coinciding with testing for brain stem death reduced consent rates.w1 In a retrospective study in which 285 next of kin were interviewed, 68% consented to donation if they thought the timing of the discussion about donation was appropriate whereas only 18% consented if they considered the timing to be poor.w4 Overall, there was no clear consensus on the optimum timing of a request other than avoiding linking the request with notification of death or the tests for brain stem death.

Giving families enough time to make a decision was also important.w1 w3 w4 w18 Many families (60%) who though that they had ample time for discussion consented to donation, while only 27% of those who thought they had insufficient time for discussion did so.w4 Two studies found that families who felt harassed or pressured to make a decision were less likely to donate.w1 w18 In another study that retrospectively interviewed the immediate next of kin of 164 medically suitable potential organ donors, 83% of donor and 56% of non-donor family respondents said that they were given enough time to understand that their relative was dead before medical staff brought up organ donation.w3

Setting in which the request is made

Evidence that a private location for discussion about organ donation improves consent rates is clearly documented.w2 w3 In two studies consent rates for requests made in settings that provided little privacy (requests made by telephone, in the patient’s room, at the nursing station, or in the hallway) were 45% and 30% compared with consent rates of 56% and 52% in more private settings (table 5).w2 w3 One study showed no significant benefit of a private setting for organ donation requests.w20

Table 5.

Studies showing association between setting in which request for organ donation was made and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor was present or not

| Author | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| Gortmaker et al,w2 1998, US | 707 | Data collected prospectively for medically suitable potential donors referred to three OPOs | Place of request private | 67 | 45 | <0.001 |

| DeJong et al,w3 1998, US | 164 | Structured telephone interview with immediate next of kin 4-6 months after death of relative | Setting provided little privacy (hallway/waiting room) | 30 | 52 | <0.02 |

OPO=organ procurement organisation.

Approach and expertise of the person making the request

The most studied factor influencing consent is the approach and expertise of the person making the request. Fourteen studies investigated this (tables 6 and 7). w1 w2 w3 w4 w5 w7 w10-w17 Differences in consent rates seem to be associated with which professionals are involved with the request process.w1 w2 w4 w7 w10 w11 In a study of 707 requests for organ donation, a combined approach by hospital staff and coordinators from an organ procurement organisation (OPO) resulted in a consent rate of 72%. Hospital staff alone had a consent rate 53%, while coordinators alone had a consent rate 62%.w2 Similarly, a retrospective study in Texas of 185 medically suitable organ donors over one year showed that the consent rate was 67% when the OPO coordinator approached the family alone, 9% when hospital staff approached the family alone, and 75% when the approach was made jointly.w10

Table 6.

Studies showing association between approach and expertise of person making request for organ donation and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor was present or not, unless stated otherwise

| Author | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent to organ donation | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| Siminoff et al,w1 2001, US | 420 | Retrospective data collection via chart reviews, telephone interviews with healthcare practitioners or OPO staff, and face to face interviews with family for all donor eligible deaths | Mean comfort of healthcare professionals with answering families’ questions about donation (0-10 scale) | 9.3 | 9 | <0.001 |

| Relatives felt harassed or pressurised to make decision | 34 | 59* | 0.002 | |||

| Healthcare professional other than physician broached possibility of organ donation, followed by meeting with OPO staff person | NA | NA | <0.001 | |||

| Mean time spent with OPO (mins) | 3.6 | 1 | <0.001 | |||

| Gortmaker et al,w2 1998, US | 707 | Data collected prospectively for medically suitable potential donors who had been referred to three organ procurement organisations | Hospital staff and OPO coordinators involved in request | 72 | — | <0.001 (across groups) |

| Request by OPO staff alone | 62 | — | ||||

| Request by hospital staff alone | 53 | — | ||||

| DeJong et al,w3 1998, US | 164 | Structured telephone interview with immediate next of kin 4-6 months after death of relative | Hospital staff first mentioned donation | 52 | 29 | 0.03 (across groups) |

| OPO coordinator first mentioned donation | 13 | 16 | ||||

| Person formally asking for donation first mentioned donation | NA | NA | NS | |||

| Rodrigue et al,w4 2006, US | 285 | Retrospective structured telephone interview with next of kin of donor eligible dead individuals | OPO staff first mentioned request | 72 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Perceived requestor very compassionate | 67 | 25* | <0.001 | |||

| Rosel et al,w5 1999, Spain | 71 | Postal survey sent to all families who had been approached for organ donation at single hospital within 12 month period | Manners of requesting doctor | NA | NA | <0.01 |

| von Pohle et al,w7 1996, US | 81 | Retrospective chart review | Request by OPO staff | 89 | — | <0.05 (across groups) |

| Request by physician | 4 | — | ||||

| Klieger et al,w10 1994, US | 185 | Retrospective review | Request by OPO staff alone | 67 | — | <0.001 (across groups) |

| Request by hospital staff alone | 9 | — | ||||

| Hospital staff and OPO involved in request | 75 | — | ||||

| Evanisko et al,w14 1998, US | 1061 | Staff questionnaire | Staff training (how to request organ donation, explaining brain death, counselling grieving family). In hospitals with high rates of organ donation, 52.9% of staff had received training; in hospitals with low rates of organ donation, 23.5% of staff had received training | Before change | After change | <0.01 |

OPO=organ procurement organisation; NA=not available, data not given; non-significant difference, actual P value not reported..

*Calculated from published data.

Table 7.

Before and after audit studies of practice change showing association between approach and expertise of person making request for organ donation and consent rate for organ donation. Numbers are percentages of relatives consenting to organ donation when factor was present or not

| Author | No studied | Type of study | Factors associated with consent to organ donation | % consenting | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With factor | Without factor | |||||

| von Pohle et al,w7 1996, US | 61 before, 35 after | Retrospective chart review | Rate of donation increased with addition of institutionally dedicated organ procurement organisation representative and routine use of decoupling | 38 | 59 | <0.05 |

| Helms et al,w11 2004, US | 164 before, 137 after | Prospective collection of data compared with data before installation of neurointensivist led team | Consent rate increased after policy change in unit (uncoupling and removal of treating physician from donation requests; request made by procurement officer) | 23 | 37 | 0.01 |

| Consent rates for donations in NCCU after policy change, were significantly higher than in other intensive care units in same hospital (36.5% v 22. 4%, P=0.003) | 37 | 22 | 0.003 | |||

| Shafer et al,w12 1998, US | 313 before, 112 after | Retrospective study before and after implementation of in-house coordinator in hospital with level 1 trauma centre | Implementation of in-house coordinators: consent rate increased | 45 | 74 | <0.001* |

| Shafer et al,w13 2003, US | 770 before, 2284 after Includes data from refw12 | Retrospective evaluation of in-house coordinator programme in 2 hospitals with trauma centres | Placement of in-house coordinators within trauma centres: consent rate averaged 67%, representing 37% increase above period before in-house coordinators | 49 | 67 | <0.001* |

| Trauma centres with in-house coordinators had 28% greater consent rate and 48% greater conversion rate of potential donors to actual donors than other 85 level 1 trauma centres | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Riker et al,w16 1995, US | 155 before, 49 after | Non-randomised, controlled, before and after intervention trial | Evaluated consent rate after two 1 hour educational sessions with emergency physicians v control group of consulting physicians. After intervention emergency physician consent rate increased from 0% to 32% (P<0.001) but control group consent rate increased from 2.6% to 6.6% | 0 | 32 | NC |

| Linyear et al,w15 1999, US | 42 before, 47 after | Retrospective medical record review; observational study after implementation of family support and communication protocol | Protocol: private setting; decoupling; request by OPO with family communication coordinator/hospital staff | 49 | 72 | NA |

| Consent rate 67% for May and June v 31% for July to December (new residents) | 67 (experienced residents) | 31 (new residents) | NA | |||

| Salim et al,w17 2007, US | 287 before, 208 after | Retrospective analysis of patients referred to regional OPO for possible organ donation comparing family consent rates before and after implementation of in-house coordinator programme | In house coordinator associated with higher consent rate | 35 | 52 | <0.01 |

NCCU=neurosciences critical care unit; NA=not available, data not given; NC=not calculable; OPO=organ procurement organisation.

*Calculated from published data.

Families have reported that conversations with OPO staff were crucial to their donation decision. Talking to a member of OPO staff before being asked to make a decision and spending more time with a member of OPO staff were both strongly associated with donation.w1

Shafer et al conducted a four year retrospective study in a large 500 bed public trauma hospital.w12 An independent organ procurement organisation hired two in house coordinators, one white and one black, to work exclusively in the hospital, closely managing and coordinating the consent process. After implementation of the programme and the use of race specific requestors, there was a 64% increase in the consent rate and an overall increase of 94% in the number of organ donors. There were significant increases in consent across all racial and ethnic groups, with the largest increases noted in minority populations. A comparison of level 1 trauma centres in the US with and without in house coordinators showed that conversion of potential organ donors to actual donors was 48% greater in centres with in house coordinators.w13 Similarly, a retrospective analysis of 495 patients referred to the regional organ procurement organisation for possible organ donation recorded a rise in the consent rate from 35% to 52% with the implementation of an in house coordinator.w17

There is a correlation between staff training in effective procedures for requesting organ donation and donation rates.w14-w16 In hospitals with high rates of organ donation, 53% of the staff had received training compared with 24% of staff in hospitals with low rates of organ donation.w14 Interestingly, the consent rate seems to differ with time of year, relating to medical skill. In the US new medical residents enter their respective programmes in July. One study found that the consent rate for May to June was 67% compared with 31% for July to December of the same year.w15 Finally, it seems that courtesy increases organ donation rates.w5

Discussion

The main modifiable factors significantly associated with whether relatives deny or allow organ donation were information discussed during the request, perceived quality of care of the donor, understanding of brain stem death, specific timing of the request, setting in which the request is made, and the approach and skill of the individual making the request. Ensuring that adequate time is available both to make the request and to allow families to consider the request also seems important. Many of these findings are unsurprising. For example, it is standard practice when “breaking bad news” to families and individuals in a medical setting to pace the sequence of information provided and deliver the news in a private and quiet location.6 The idea of decoupling pronouncement of death and requests for organ donation is at least 20 years old. A study conducted by Kentucky Organ Donor Affiliates in 1989-90 reported that consent rates increased from 18% to 60% if there was a separation of time between the pronouncement of death and the approach for organ donation.w8

Limitations and strengths

Our review will identify only those factors that have been studied and reported and only those at the level of individual requests. Factors modifiable at a population level, such as the fraction of the population participating in an organ donor register, and some factors modifiable at a hospital level, such as local donation champions, did not appear in the identified studies. Many of the studies identified were retrospective reviews of medical records. There was a large reliance on hospital or OPO staff as data collectors, who might not be unbiased observers. Most of the studies were based on small numbers, and there were no randomised controlled studies from which to draw data. Several of the studies were based on structured interviews with donor and non-donor families, with little detail on whether the sample interviewed are representative of the whole. These interviews were based on family recollections and thus are accurate only to the extent that their memories of these events are accurate, introducing recall bias. Finally, as the studies are observational, factors correlated with consent to organ donation might not be causative.

The current literature comes almost exclusively from the US. The donation rates seen in many of these studies are higher than those in the UK7 so there is some reason to believe that similar strategies might have an even larger effect in the UK, where similar organ procurement structures exist.

The two factors that had the largest effect on consent rates were the person making the request and the timing of this conversation. These studies show that the requestor might have a significantly positive or negative effect on the outcome of the request process. Consent rates were higher when the request was made by the organ procurement coordinator (donor transplant coordinator in the UK) in conjunction with hospital staff members. This is often termed “collaborative requesting.” Clearly, it is not possible to place a dedicated donor transplant coordinator in every hospital that has the potential to produce organ donors because their donor pool might be quite small and this would not be cost effective. It might be possible, however, to consider this in hospitals with larger numbers of potential organ donors, such as regional neuroscience centres. UK Transplant, which provides support to transplant services in the UK, has adopted this strategy.

There is a need for large rigorously conducted intervention studies to test the factors that might be modified to increase organ donation. One such study examining methods to increase donation rates in the UK is under way: the randomised controlled ACRE (assessment of collaborative requesting) study looking at the effect of “collaborative requesting” on organ donation rates in the UK (ISRCT1169903) is the first such study in the world. It is hoped that findings from this might help in the future to increase donation rates and ultimately save lives.

The assumption underlying the ACRE study, and all the studies reported in this review, is that organ donation is of sufficient benefit to society generally, and to organ recipients specifically, to justify the study and modification of organ donation requests to maximise consent. The point at which fine tuning request procedures might be considered coercion requires further discussion and clarification.

What is already known on this topic

There is a severe shortage of organs for transplantation

The largest impediment to organ procurement is relatives’ refusal

What this study adds

The timing of the request and the person making the request have a significant impact on consent rates

Modifying the consent request process might be the fastest way to increase organ donation rates

These changes could be implemented without undue delay in the UK

Contributors: ALS screened the identified papers, extracted data, and cowrote this report. LCR conducted the initial electronic search, screened the identified papers, checked the completeness of the search, and extracted data. VSB conceived the idea, checked the initial electronic search, screened the identified papers, and managed the project. JDY checked the extracted data, cowrote this report, and is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the University of Oxford and the Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS Trust.

Competing interests: JDY is chief investigator on the ACRE (assessment of collaborative requesting) study.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b991

References

- 1.Department of Health. On the state of public health: annual report of the chief medical officer 2006. London: DH, 2007.

- 2.Barber K, Falvey S, Hamilton C, Collett D, Rudge C. Potential for organ donation in the United Kingdom: audit of intensive care records. BMJ 2006;332:1124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehy E, Conrad SL, Brigham LE, Luskin R, Weber P, Eakin M, et al. Estimating the number of potential organ donors in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;349:667-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gortmaker SL, Beasley CL, Brigham LE, Franz HG, Garrison RN, Lucas BA, et al. Organ donor potential and performance: size and nature of the organ donor shortfall. Crit Care Med 1996;24:432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Human Tissue Act 2004. London: Stationery Office, 2004.

- 6.Ptacek J, Eberhardt T. Breaking bad news: a review of the literature. JAMA 1996;276:496-502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UK Transplant. Transplant activity in the UK, annual reports 2001-06. London: UK Transplant, 2001-6.