Abstract

Modeling and analysis of genetic networks have become increasingly important in the investigation of cellular processes. The genetic networks involved in cellular stress response can have a critical effect on the productivity of recombinant proteins. In this work, it was found that the temperature-inducible expression system for the production of soluble recombinant streptokinase in Escherichia coli resulted in a lower productivity compared to the chemically-induced system. To investigate the effect of the induced cellular response due to temperature up-shift a model-based approach is adopted. The role played by the major molecular chaperone teams DnaK–DnaJ–GrpE and GroEL–GroES on the productivity of recombinant streptokinase was experimentally determined. Based on these investigations, a detailed mechanistic mathematical model was developed for the cellular response during the temperature-induced recombinant streptokinase production. The model simulations were found to have a good qualitative agreement with the experimental results. The mechanistic mathematical model was validated with the experiments conducted on a σ32 mutant strain. Detailed analysis of the parameter sensitivities of the model indicated that the level of free DnaK chaperone in the cell has the major effect on the productivity of recombinant streptokinase during temperature induction. Analysis of the model simulations also shows that down regulation or selective redirection of the heat shock proteins could be a better way of manipulating the cellular stress response than overexpression or deletion. In other words, manipulating the system properties resulting from the interaction of the components is better than manipulating the individual components. Although our results are specific to a recombinant protein (streptokinase) and the expression system (E. coli), we believe that such a systems-biological approach has several advantages over conventional experimental approaches and could be in principle extended to bigger genetic networks as well as other recombinant proteins and expression systems.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11693-009-9021-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: DnaK chaperone, Temperature induction, Soluble recombinant streptokinase, Mathematical modeling, Cellular stress response, Escherichia coli

Introduction

Escherichia coli has been used as an expression host for the production of a wide range of recombinant proteins (Baneyx 1999; Baneyx and Mujacic 2004). Several expression systems have been developed for the high-level expression of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli (Makrides 1996). Among the various expression systems used, the temperature-inducible expression system has been beneficial due to the ease of induction and higher induction strength (Seeger et al. 1995; Gupta et al. 1999). However, the use of temperature up-shift as an induction mechanism influences several cellular processes, including the up-regulation of the heat shock proteins such as molecular chaperones and proteases (Hoffmann et al. 2002; Weber et al. 2002).

The role of induction mechanism on recombinant protein production has been investigated for certain recombinant proteins in the literature. For an aggregation prone recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor, the temperature-induced expression was found to result in increased productivity and higher yield (Seeger et al. 1995). In the case of soluble Chloramphenicol Acetyl Transferase (CAT) the productivity of the temperature-inducible system was lower compared to chemically-induced system (Harcum and Haddadin 2006). Further, the global transcriptome response of recombinant E. coli producing soluble recombinant CAT was analyzed during chemical induction, temperature induction and dual induction conditions (chemical and temperature induction). The transcriptome response of the classical heat shock genes was found to be similar in the wild-type and dual stressed cultures, even though many other genes were found to be differentially expressed in these cultures. This indicates that modeling the dynamics of the heat shock proteins and their mechanism of interaction with the recombinant protein could give useful insights.

The role played by the various heat shock proteins in assisting solubilization, folding and degradation of recombinant proteins in E. coli has been extensively reviewed by Hoffmann and Rinas (2004). Co-expression of molecular chaperones in general is employed to improve the solubility and activity of recombinant proteins, which are either difficult to express or insoluble (Georgiou and Valax 1996; Venkatesh et al. 2004). However, the role played by these chaperones in enhancing the solubility and activity depends on the nature and properties of the recombinant protein. For example, the co-expression of DnaK chaperone team was found to result in reduced activity for a soluble recombinant protein glutamate racemase expressed in E. coli (Kohda et al. 2002). But, the same chaperone team was found to enhance the solubility of several aggregation prone recombinant proteins in E. coli (Georgiou and Valax 1996).

In the present work, the chemical and temperature inducible expression systems for the production of recombinant streptokinase were compared. A detailed mechanistic model for the bacterial heat shock response was developed and the dynamics of the chaperones and proteases were simulated for the mild heat shock condition, which had been used earlier for recombinant streptokinase production (Yazdani and Mukherjee 2002; Ramalingam et al. 2007). A mechanistic model for the interaction of the heat-shock proteins with the predominantly soluble recombinant streptokinase was proposed from the experimental investigations. This was coupled with the heat-shock response model to obtain the complete model for temperature-induced recombinant streptokinase production. Model equations were simulated to examine the effect of the heat-shock response on the recombinant protein production. A hypothetical condition predicted by the model simulations was validated by experiments using an E. coli-mutant for the heat-shock-specific sigma factor (σ32).

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and plasmid

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen) was used as a host for all the fermentation experiments. E. coli CAG597 (New England Biolabs), which has an rpoHam allele encoding an amber mutant for σ32, was used for the model validation. Plasmid pRSETB-STK (An ampicillin resistant plasmid) containing the streptokinase gene under a T7 promoter was used for the intracellular expression of recombinant streptokinase (Balagurunathan and Jayaraman 2008). Plasmid pGP1-2 (a kanamycin resistant plasmid) containing the T7 RNA polymerase gene under the control of heat inducible λPL promoter (Tabor and Richardson 1985) was used along with pRSETB-STK for temperature-inducible expression of recombinant streptokinase. Plasmid pKJE-6, (Nishihara et al. 1998) a Chloramphenicol resistant plasmid, was used for the co-expression of chaperones. This plasmid contains DnaK chaperone team (DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE) under arabinose promoter and GroEL chaperone team (GroEL/GroES) under tetracycline promoter.

Media and culture conditions

The medium for shake flask and bioreactor experiments consisted of K2HPO4, 5 g/l; KH2PO4, 3 g/l; NaCl, 0.5 g/l; NH4Cl, 1 g/l; yeast extract, 5 g/l; glucose, 5 g/l; MgSO4, 0.5 g/l; and trace metal solution, 1 ml/l (trace metal solution composition: FeSO4, 100 mg/l; Al2(SO4)3 · 7H2O, 10 mg/l; CuSO4 · H2O, 2 mg/l; H3BO3, 1 mg/l; MnCl3 · 4H2O, 20 mg/l; NiCl2 · 6H2O, 1 mg/l; Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 50 mg/l; ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 5 mg/l) (Yazdani and Mukherjee 2002). Batch bioreactor cultivations were carried out in a 3.7 liter fermentor (KLF 2000, Bioengineering AG, Switzerland) equipped with pH, temperature, antifoam and dissolved oxygen controllers. Dissolved oxygen was maintained at 30% saturation and pH at 7.0 for all bioreactor experiments.

Induction conditions

The cultures were induced at the mid-exponential phase around 0.6 OD (600 nm) in the shake flask experiments and around 3 OD (600 nm) in the batch bioreactor experiments. IPTG (0.25 mM) was used for chemical induction and temperature shift from 30°C to 37°C/42°C was used for temperature-induction. L- Arabinose (0.1% to 0.4% w/w) was used for the induction of DnaK chaperone team and Tetracycline (2–10 ng/ml) was used for the induction of GroEL chaperone team.

Cell fractionation

Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000g for 10 min. The cell pellet obtained was re-suspended in phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.2) and brought to an optical density of around 5 and sonicated on ice, for 2 min. The sonicated sample was centrifuged at 10,000g for 15 min and the supernatant was recovered as soluble fraction. The pellet obtained from the previous step was washed twice with phosphate buffer and then resuspended in 1% SDS to obtain the insoluble fraction.

Assay for streptokinase activity

Quantitative assay for streptokinase was done by incubating the samples with human plasminogen (Sigma, P5661) at 37°C for 5 min and then measuring the amount of plasmin formed by using a chromogenic substrate, Chromozym-PL (Sigma, T6140), as described by Yazdani and Mukherjee (2002).

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, immunoblotting and quantification

Gel electrophoresis was carried out according to Laemmli (1970) using SDS-Polyacrylamide gels stained with Commassie Brilliant Blue. Densitometric analysis (Quantity One software, Biorad) was used for quantification of proteins in SDS-PAGE Gels. A known concentration of a standard protein, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), is mixed with samples prior to mixing with sample buffer. The samples were then boiled for 10 min at 95°C and then subjected to SDS-PAGE. The stained gels were captured and densitometric analysis was performed using the known protein as the internal standard. Immunoblotting was performed according to standard procedures using a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for the streptokinase (a gift from Dr. Behnaz Parhami-Seren (Parhami-Seren et al. 2002), University of Vermont, Burlington) and a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for DnaK(Calbiochem) as primary antibodies and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG as secondary antibody (Calbiochem). Densitometric analysis of the blot was performed using the Quantity One software (Biorad).

Unit conversion

The volumetric activity of streptokinase is expressed in Units per ml of culture volume and specific activity in Units per mg of streptokinase. The data for quantity of streptokinase produced is expressed in micrograms per ml of culture volume. The model simulations are represented in M (Molar units). For the comparison of experimental data and model simulations (Fig. 7), the quantity of streptokinase produced per unit culture volume (μg/ml) was converted to molar concentration within the cell. The conversion was based on the biomass concentration (dry cell weight), volume of single cell and the assumption that protein content of a single cell is 0.154 pg (Neidhardt 1987). The total protein content was assumed to be 50% of the dry cell weight.

Fig. 7.

Simulations results for chaperone coexpression. a and b Comparison of the model simulations and experimental data for streptokinase levels during DnaK chaperone coexpression. Control—When streptokinase alone is induced. c and d Comparison of the model simulations and experimental data for streptokinase levels during GroEL chaperone coexpression. Control—When streptokinase alone is induced. e and f Comparison of the model simulations and experimental data for streptokinase levels during the simultaneous coexpression of both the chaperone teams. Control—When streptokinase alone is induced

Computational methods

Model assumptions

The model built uses first-order mass action kinetics. It was assumed that all mRNAs are degraded at the same rate and all the cellular proteins are degraded at the same rate. The growth/dilution rate is assumed to be constant. Transcription, translation, folding and misfolding were assumed to follow first-order dynamics and the aggregation step for the recombinant protein was assumed to follow second-order kinetics. Binding rates between proteins or between proteins and specific DNA promoters were assumed to be faster compared with rates of synthesis of mRNAs and proteins and the complexes were assumed to be in equilibrium. Therefore, the binding equations are represented as algebraic equations. Since σ70 and RNAP are expressed constitutively in the cell, their total concentrations are assumed to be constant. The total protein content of the cell is also assumed to be constant.

Model structure

Transcription, translation and protein folding are represented as differential equations and mass balance/binding are represented by algebraic equations. This results in a system of differential algebraic equations (DAEs). The components of the model and the complete set of model equations are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Components of the model developed for the cellular response to temperature induced recombinant streptokinase production

| Components | Description |

|---|---|

| σ32 | Alternative transcription factor |

| σ70 | Vegetative transcription factor |

| D | Non-specific DNA binding site |

| DnaK | DnaK chaperone team |

| FtsH | Heat-shock protease (s) responsible for chaperone mediated proteolysis |

| GroEL | GroEL chaperone team |

| HslVU | Heat-shock protease (s) responsible for direct proteolysis |

| pcn | Recombinant gene promoter |

| Pfolded | Total folded proteins in the cell |

| Pg | Housekeeping gene promoter |

| Ph | Heat-shock gene promoter |

| Punfolded | Total Unfolded proteins in the cell |

| RecP | Total Recombinant protein |

| RecPA | Aggregated recombinant protein |

| RecPfolded | Folded recombinant protein |

| RecPI | Recombinant protein initial translational product |

| RecPunfolded | Unfolded/Misfolded recombinant protein |

| RNAP | RNA polymerase in the cell |

| T Protein | Total protein in the cell |

| Subscript ‘f’ | Free concentration of the species |

| Subscript ‘t’ | Total concentration of the species |

| Complexes | Description |

| σ32:DnaK | Complex between σ32 and DnaK |

| σ32:DnaK:FtsH | Complex between DnaK bound σ32 and FtsH |

| σ32:GroEL | Complex between σ32 and GroEL |

| σ32:HslVU | Complex between σ32 and HslVU |

| Punfolded:DnaK | Complex between unfolded proteins in the cell and DnaK |

| Punfolded:GroEL | Complex between unfolded proteins in the cell and GroEL |

| RecPA:DnaK | Complex between DnaK and aggregated recombinant protein |

| RecPI:DnaK | Complex between DnaK and recombinant protein initial translation product |

| RecPI:DnaK:FtsH | Complex between DnaK bound recombinant protein initial translation product and FtsH |

| RecPI:RecPI | Aggregation of recombinant protein initial translation product |

| RecPunfolded:DnaK | Complex between DnaK and unfolded recombinant protein |

| RecPunfolded:DnaK:FtsH | Complex between DnaK bound unfolded recombinant protein and FtsH |

| RecPunfolded:GroEL | Complex between GroEL and unfolded recombinant protein |

| RecPunfolded:HslVU | Complex between HslVU and unfolded recombinant protein |

| RNAP:D | Complex between RNA polymerase and non-specific DNA binding sites |

| RNAP:σ32 | Complex between RNA polymerase and σ32 |

| RNAP:σ70 | Complex between RNA polymerase and σ70 |

| RNAP:σ32:D | Complex between σ32 bound RNA Polymerase and non-specific DNA binding sites |

| RNAP:σ32:ph | Complex between σ32 bound RNA polymerase and heat-shock gene promoters |

| RNAP:σ70:D | Complex between σ70 bound RNA Polymerase and non-specific DNA binding sites |

| RNAP:σ70:pg | Complex between σ70 bound RNA polymerase and housekeeping gene promoters |

| RNAP:σ70:pcn | Complex between σ70 bound RNA polymerase and recombinant gene promoter |

Table 2.

List of model equations

| S. No | Equation and description |

|---|---|

| 1 |

This equation describes the rate of change of σ32 mRNA in the cell |

| 2 |

This equation describes the rate of change of Total σ32 in the cell |

| 3 |

The mass balance equation for σ32 |

| 4 |

Rate of change of mRNA of DnaK chaperone team in the cell |

| 5 |

Rate of change of Total DnaK in the cell |

| 6 |

Mass balance equation for DnaK Chaperone team |

| 7 |

Rate of change of mRNA of GroEL chaperone team in the cell |

| 8 |

Rate of change of Total GroEL in the cell |

| 9 |

Mass balance equation for GroEL chaperone team |

| 10 |

Rate of change of mRNA of FtsH in the cell |

| 11 |

Rate of change of total FtsH in the cell |

| 12 |

Mass Balance equation for FtsH Protease |

| 13 |

Rate of change of mRNA of HslVU in the cell |

| 14 |

Rate of change of Total HslVU in the cell |

| 15 |

Mass Balance equation for HslVU protease |

| 16 |

Rate of change of mRNA of total proteins in the cell |

| 17 |

Rate of change of the total folded proteins in the cell |

| 18 |

Rate of change of total unfolded proteins in the cell |

| 19 |

Rate of change of the mRNA of the recombinant protein in the cell. |

| 20 |

Rate of change of the total initial translation product in the cell |

| 21 |

Mass Balance equation for the Initial translation product of recombinant protein. |

| 22 |

Rate of change of the folded recombinant protein in the cell |

| 23 |

Rate of change of the total unfolded recombinant protein in the cell |

| 24 |

Mass balance equation for the total unfolded recombinant protein in the cell |

| 25 |

Rate of change of the total aggregated recombinant protein in the cell |

| 26 |

Mass Balance equation for the aggregated recombinant protein in the cell |

| 27 |

Mass Balance equation for total unfolded protein in the cell |

| 28 |

Mass balance equation for total RNA Polymerase in the cell |

| 29 |

Mass balance equation for total σ70 in the cell |

| 30 |

Binding equation for σ70 and RNA polymerase |

| 31 |

Binding equation for σ32 and RNA polymerase |

| 32 |

Binding equation for σ70:RNA Polymerase with house keeping gene promoters |

| 33 |

Binding equation for σ32:RNA polymerase with heat-shock gene promoters |

| 34 |

Binding equation for RNA polymerase and non-specific DNA binding sites |

| 35 |

Binding equation for σ70:RNA polymerase and non-specific DNA binding sites |

| 36 |

Binding equation for σ32:RNA polymerase and non-specific DNA binding sites |

| 37 |

Binding equation for σ32 and DnaK |

| 38 |

Binding equation for σ32 and GroEL |

| 39 |

Binding equation for σ32 and HslVU |

| 40 |

Binding equation for σ32:DnaK and FtsH |

| 41 |

Binding equation for unfolded proteins and DnaK |

| 42 |

Binding equation for unfolded proteins and GroEL |

| 43 |

Binding equation for recombinant protein initial translational product and DnaK |

| 44 |

Binding equation for RecPI:DnaK and FtsH |

| 45 |

Binding equation for unfolded recombinant protein and DnaK |

| 46 |

Binding equation for unfolded recombinant protein and GroEL |

| 47 |

Binding equation for RecPunfolded:DnaK and FtsH |

| 48 |

Aggregation rate of the recombinant protein initial translation product |

| 49 |

Binding equation for aggregated recombinant protein and DnaK |

| 50 |

Binding equation for unfolded recombinant protein and HslVU |

| 51 |

Binding equation for σ70:RNAP to recombinant gene promoters |

Selection of model parameters

The model parameters include transcription and translation rate constants, binding rate constants, degradation rate constants and protein folding and misfolding rate constants. The binding, degradation and protein folding rate constants are selected from different sources in the literature. The parameters specific for recombinant streptokinase were selected based on available literature on streptokinase folding and aggregation or suitably assumed. The transcription rate constants were tuned to represent the steady state concentration of proteins in the unstressed cell. The complete list of parameter values and the sources of these parameters are presented in Table 3. The values of the parameters used to simulate the various experimental conditions and the initial conditions used for the simulations are listed in Tables 4 and 5 respectively.

Table 3.

List of parameters used in the model

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | Association constant between RNAP and σ70 | 4e9 M−1 | Maeda et al. 2000 |

| K2 | Association constant between RNAP and σ32 | 1e9 M−1 | Maeda et al. 2000 |

| K3 | Association constant between RNAP:σ70 and pg | 1e8 M−1 | Assumed based on Roe et al. 1985 |

| K4 | Association constant between RNAP:σ32 and ph | 3e8 M−1 | Assumed based on Roe et al. 1985 |

| K5 | Association constant between RNAP and pcn | 3e9 M−1 | Modified from Ujvari and Martin 1996 |

| K6 | Association constant between RNAP and non-specific DNA binding site D | 1e6 M−1 | Grigorova et al. 2006 |

| K7 | Association constant between RNAP:σ70 and D | 1e5 M−1 | Grigorova et al. 2006 |

| K8 | Association constant between RNAP:σ32 and D | 1e5 M−1 | Grigorova et al. 2006 |

| K9 | Association constant between σ32 and DnaK | 3e5 M−1 | Chattopadhyay and Roy 2002 |

| K10 | Association constant between σ32 and GroEL | 1e6 M−1 | Guisbert et al. 2004 |

| K11 | Association constant between σ32 and HslVU | 1e8 M−1 | Gamer et al. 1996 |

| K12 | Association constant between σ32:DnaK and FtsH | 1e8 M−1 | Gamer et al. 1996 |

| K13 | Association constant between Unfolded proteins and DnaK | 2e6 M−1 | Siegenthaler and Christen 2006 |

| K14 | Association constant between Unfolded proteins and GroEL | 1e6 M−1 | Lin et al. 1995 |

| K15 | Association constant between Recombinant protein Initial translation product and DnaK | 1e6 M−1 | Assumed based on Koller et al. 2002 |

| K16 | Association constant between DnaK:Recombinant protein Initial translation product and FtsH | 1e7 M−1 | Kurata et al. 2006 |

| K17 | Association constant between Misfolded Recombinant protein and DnaK | 1e6 M−1 | Assumed based on Koller et al. 2002 |

| K18 | Association constant between Misfolded Recombinant protein and GroEL | 1e6 M−1 | Lin et al. 1995 |

| K19 | Association constant between DnaK:Misfolded Recombinant protein with FtsH | 1e6 M−1 | Assumed based on Koller et al. 2002 |

| K20 | Association between Misfolded Recombinant protein to form aggregates | 1e6 M−1 | Assumed |

| K21 | Association constant between Aggregated Recombinant protein and DnaK | 1e6 M−1 | Assumed based on Koller et al. 2002 |

| K22 | Association constant between Misfolded Recombinant protein and HslVU | 1e7 M−1 | Assumed based on Koller et al. 2002 |

| Kx1 | Degradation rate constant of FtsH bound protein molecules | 5 min−1 | Kurata et al. 2006 |

| Kx2 | Degradation rate constant of HslVU bound protein molecules | 5 min−1 | Assumed based on Kurata et al. 2006 |

| Kx3 | Inactivation rate of GroEL bound Sigma32 | 5 min−1 | Assumed based on Guisbert et al. 2004 |

| Kx4 | Folding rate constant for total cellular proteins | 1.5e4 min-1 | Kurata et al. 2006 |

| Kx5 | Misfolding rate constant of cellular proteins | 75, 150, 225 min−1 | Adjustable (Temp- dependent) |

| Kx6 | Intrinsic folding rate of the recombinant protein | 90 min−1 | Gromiha et al. 2006 |

| Kx7 | Aggregation rate of the misfolded recombinant protein | 0.5 min−1 | Assumed based on Azuaga et al. 2002 |

| Kx8 | Disaggregation rate of recombinant protein aggregates by DnaK | 0.2 min-1 | Assumed |

| Kx9 | Misfolding rate of the recombinant Protein initial translation product | 0.2 min−1 | Assumed |

| Kx10 | Assisted folding rate of the misfolded recombinant protein | 6 min−1 | Assumed |

| Km1 | Transcription rate of σ32 | 0.001 min−1 | Tunable |

| Km2 | Transcription rate of DnaK | 30 min−1 | Tunable |

| Km3 | Transcription rate of GroEL | 45 min−1 | Tunable |

| Km4 | Transcription rate of FtsH | 1 min-1 | Tunable |

| Km5 | Transcription rate of HslVU | 2 min−1 | Tunable |

| Km6 | Transcription rate of Total Protein | 5.7e-6 M/min−1 | Tunable |

| Km7 | Transcription rate of recombinant protein | Adjustable (60 min−1) | Tunable |

| KTL | Translation rate | 20 min−1 | Kurata et al. 2006 |

| Kmd | mRNA degradation rate | 0.5 min−1 | Kurata et al. 2006 |

| Kpd | Protein degradation rate | 0.03 min-1 | Kurata et al. 2006 |

| µ | Specific growth rate (Dilution rate of intracellular components) | 0.0116 min−1 | Calculated |

| η | Efficiency of translation of σ32 mRNA | 1, 5, 10 | Adjustable (Temp dependent) |

| RNAPt | Total RNA Polymerase in the cell | 5.105e-6 M | Maeda et al. 2000 |

|

Total σ70 in the cell | 1.778e-6 M | Maeda et al. 2000 |

|

Total housekeeping gene promoters in the cell | 1.016e-5 M | Kurata et al. 2006 |

|

Total heat-shock gene promoters in the cell | 7.62e-8 M | Kurata et al. 2006 |

|

Total recombinant gene promoters in the cell (Plasmid copy number) | 3.321e-8 M | Calculated |

|

Total non-specific binding sites in the cell | 1.18e-2 M | Grigorova et al. 2006 |

Table 4.

Values of parameters used for simulating different experimental conditions

| S. No | Condition | Parameter Values |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chemical induction | η = 1; Kx5 = 75 min−1; Km7 = 60 min−1 |

| 2 | Temperature induction (30–37ºC) | η = 5; Kx5 = 150 min−1; Km7 = 60 min−1 |

| 3 | DnaK co-expression | η = 1; Kx5 = 75 min−1; Km2 = 60 min−1; Km7 = 60 min−1 |

| 4 | GroEL co-expression | η = 1; Kx5 = 75 min−1; Km3 = 90 min−1; Km7 = 60 min−1 |

| 5 | DnaK and GroEL co-expression | η = 1; Kx5 = 75 min−1; Km2 = 60 min−1; Km3 = 90 min−1; Km7 = 60 min−1 |

| 6 | Temperature induction in a σ32 conditional mutant strain (30–37ºC) | η = 0.5; Kx5 = 150 min−1; Km7 = 60 min−1 |

Table 5.

Initial conditions used for the simulation of the model

| S. No | Variable | Initial Value (M) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | mRNA of σ32 [mRNA(σ32)] | 1.162e-9 |

| 2 | Total σ32 [ ] ] |

4.483e-8 |

| 3 | Free σ32 [ ] ] |

3.32e-9 |

| 4 | mRNA of DnaK [mRNA (DnaK)] | 2.49e-9 |

| 5 | Total DnaK [DnaKt] | 1.65e-5 |

| 6 | Free DnaK [DnaKf] | 2.142e-7 |

| 7 | mRNA of GroEL [mRNA(GroEL)] | 2.49e-9 |

| 8 | Total GroEL [GroELt] | 1.65e-5 |

| 9 | Free GroEL [GroELf] | 2.142e-7 |

| 10 | mRNA of FtsH [mRNA(FtsH)] | 4.98e-8 |

| 11 | Total FtsH [FtsHt] | 3.305e-6 |

| 12 | Free FtsH [FtsHf] | 3.274e-6 |

| 13 | mRNA of HslVU [mRNA(HslVU)] | 1.6603e-9 |

| 14 | Total HslVU [HslVUt] | 9.912e-7 |

| 15 | Free HslVU [HslVUf] | 9.895e-7 |

| 16 | mRNA of Total protein in the cell [mRNA(TProtein)] | 7.62e-6 |

| 17 | Total folded protein in the cell [Pfoldedt] | 5.03e-3 |

| 18 | Total unfolded protein in the cell [Punfoldedt] | 5.01e-5 |

| 19 | Free unfolded protein in the cell [Punfoldedf] | 2.486e-5 |

| 20 | Free RNA polymerases in the cell [RNAPf] | 1e-6 |

| 21 | Free σ70 in the cell [ ] ] |

3.54e-9 |

| 22 | mRNA of recombinant protein [mRNA(RecP)] | 0 |

| 23 | Total recombinant protein initial translation product [RecPIt] | 0 |

| 24 | Free recombinant protein initial translation product [RecPIf] | 0 |

| 25 | Total Folded recombinant protein [RecPFoldedt] | 0 |

| 26 | Total misfolded recombinant protein [RecPunfoldedt] | 0 |

| 27 | Free misfolded recombinant protein [RecPunfoldedf] | 0 |

| 28 | Total aggregated recombinant protein [RecPAt] | 0 |

| 29 | Free aggregated recombinant protein [RecPAf] | 0 |

Results

Comparison of chemical and temperature induction

Initial experiments on chemical and temperature inducible expression systems were carried out to identify appropriate expression conditions to compare the two induction mechanisms. The productivity of chemically induced system was found to be independent of inducer concentration (between 0.1 mM and 2 mM IPTG) and most of the recombinant protein was found in soluble fraction (Balagurunathan and Jayaraman 2008). The temperature-induction system was found to result in lower productivities when a higher temperature shift (30–42°C) was used for induction as compared to a mild increase in temperature (30–37°C). The solubility of the protein was also significantly affected at higher temperatures (data not shown). Due to the higher productivity and solubility obtained during mild increase in temperature (30–37°C), this condition was used for the temperature induction experiments.

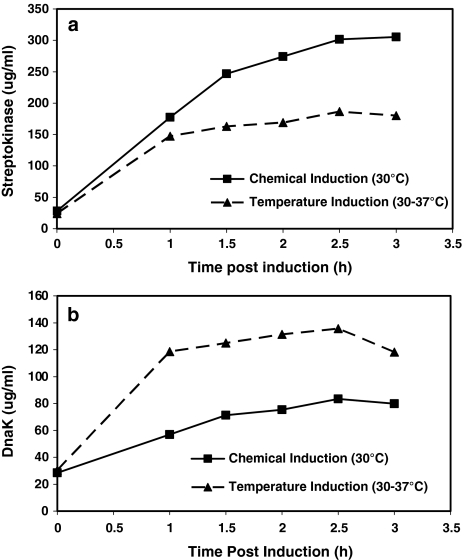

The recombinant strains used for temperature induction and chemical induction were grown at 30°C under identical conditions in a batch bioreactor to analyze the effect of induction mechanism on recombinant streptokinase production. At the mid-exponential phase (~3 OD) either the cultivation temperature was shifted to 37°C or 0.25 mM IPTG was added. The quantity of recombinant streptokinase produced during these conditions is shown in Fig. 1a. It could be observed that, the quantity of recombinant streptokinase produced in the temperature-inducible expression system was two-fold lower compared to the chemically-induced system. Further, the level of major heat shock chaperone DnaK was found to be elevated during the temperature induction as compared to the chemical induction (Fig. 1b). This indicates that the induction of the heat shock response during the temperature up-shift could have a major role on recombinant streptokinase production. The role of the major heat shock proteins on the production of recombinant streptokinase was further investigated by chaperone co-expression experiments.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of chemical and temperature induction. Comparison of the level of streptokinase (a) and DnaK (b) in the temperature-inducible and chemical inducible expression systems during batch bioreactor cultivation. IPTG concentration −0.25 mM, Temperature shift –30 to 37°C

Effect of co-expression of molecular chaperones on recombinant streptokinase production

Two major chaperone teams required for the maintenance of protein quality in the cytoplasm are HSP70 (DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE) and HSP60 (GroEL/ES). The effect of these chaperones on recombinant streptokinase production was analyzed by chaperone co-expression experiments. The effect of co-expression of DnaK chaperone team (DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE) and GroEL chaperone team (GroEL and GroES) on streptokinase production is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of chaperone coexpression. DnaK Chaperone Coexpression: Recombinant streptokinase, DnaK and GroEL levels observed during DnaK chaperone co-expression are shown in (a), (b), and (c). Streptokinase was induced with 0.25 mM IPTG and DnaK chaperone team was induced either with 0.1% or 0.2% Arabinose. Control cultivation—Streptokinase alone was induced GroEL Chaperone Coexpression: Recombinant streptokinase, DnaK and GroEL levels observed during GroEL chaperone co-expression are shown in (d), (e), and (f). Streptokinase was induced with 0.25 mM IPTG and GroEL chaperone team was induced either with 2 ng/ml or 5 ng/ml of Tetracycline. Control cultivation—Streptokinase alone was induced Coexpression of both chaperones: Profiles of Recombinant streptokinase, DnaK and GroEL obtained during simultaneous coexpression of both the chaperone teams are shown in (g), (h), and (i). Streptokinase was induced with 0.25 mM IPTG and DnaK chaperone team was induced 0.1% Arabinose and GroEL chaperone team was induced with 2 ng/ml Tetracycline. Control cultivation—Streptokinase alone was induced

The following observations were made based on these experiments

The DnaK and GroEL levels were found to increase significantly upon respective induction when compared to the control experiment (Fig. 2b, f).

The co-expression of one chaperone team was not found to affect the level of the other chaperone team (Fig. 2c, e).

The streptokinase levels were found to be lower when the DnaK chaperone team was co-expressed (Fig. 2a).

Streptokinase levels obtained during GroEL co-expression experiments were similar to that obtained in the control experiments (Fig. 2d).

During the co-expression of both the chaperone teams, the streptokinase levels were found to be two fold lower (Fig. 2g).

The over expression of recombinant streptokinase alone does not lead to any significant increase in the DnaK or GroEL levels indicating that the induction of the recombinant protein alone does not trigger any heat shock like response.

The growth of the cell was not affected by the expression either of the chaperone teams or by the expression of streptokinase (data not shown).

To investigate the role of these chaperones further, the effect of varying induction of one chaperone team at a constant induction for other chaperone team on recombinant streptokinase production was studied. It was observed that the amount of streptokinase produced was lower when higher levels of DnaK were present, irrespective of the levels of GroEL chaperone. (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figures).

Effect of chaperone co-expression on the volumetric and specific activity of recombinant streptokinase

The volumetric activity of recombinant streptokinase was two fold lower when DnaK chaperone team was co-expressed and two fold higher when GroEL chaperone team was co-expressed. The volumetric activity was similar to control experiments when both the chaperone teams were co-expressed (Fig. 3a). The specific activity of recombinant streptokinase was similar to its value in the control experiments when DnaK chaperone team was co-expressed but increased by nearly 2 to 3 fold when GroEL chaperone team was co-expressed (Fig. 3b). The specific activity of streptokinase increased two fold when both the chaperone teams were co-expressed. The analyses of the changes in the activity of recombinant streptokinase during the various chaperone coexpression experiments indicate that the presence of GroEL chaperone team was found to enhance the specific activity of recombinant streptokinase. However, the GroEL chaperone team was not found to enhance the amount of the recombinant protein produced.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of the activity and solubility of recombinant streptokinase during chaperone coexpression. Volumetric activity and Specific activity of recombinant streptokinase (shake flask cultivation) in a sample collected 5 h after the simultaneous induction of streptokinase and the concerned chaperone(s) is shown in (a) and (b). The total amount of recombinant streptokinase observed in the insoluble fraction in one representative sample during chaperone coexpression experiments is shown in (c)

Analysis of insoluble fraction and degradation pattern of recombinant streptokinase during chaperone co-expression

During the chaperone coexpression experiments, the quantity of streptokinase observed in the insoluble fraction was only 5–6% of the total streptokinase produced. However, there was a variation in the quantity of streptokinase observed in the insoluble fraction during the chaperone coexpression experiments (Fig. 3c). Co-expression of DnaK chaperone team led to a reduction in the amount of streptokinase observed in the insoluble fraction, while co-expression of GroEL chaperone team lead to a slight increase in the insoluble fraction of streptokinase, when compared with the control cultivation. The degradation pattern of recombinant streptokinase was analyzed by Western blot (Fig. 2, Supplementary Figures). The pattern of degradation was found to be similar during DnaK chaperone coexpression and GroEL chaperone co-expression indicating that the lower productivity observed during DnaK chaperone coexpression may not be due to specific cleavage of the protein and may be due to complete proteolysis.

Mechanism of interaction of the heat-shock proteins and recombinant streptokinase

Four major heat shock proteins (namely the DnaK chaperone team, the GroEL chaperone team, FtsH protease and HslVU protease) are considered in the modified bacterial heat shock response model (Supplementary Material, Figure SI.1). The mechanism of interaction of these heat-shock proteins with recombinant streptokinase is proposed based on the chaperone co-expression experiments. Analyses of the chaperone co-expression experiments indicate the following:

The co-expression of DnaK chaperone team leads to lower accumulation of soluble recombinant streptokinase, irrespective of the levels of the GroEL chaperone team.

The streptokinase productivity was not found to decrease with the increase in the DnaK concentrations during DnaK co-expression experiments.

The complete degradation of recombinant protein was not observed even at high concentrations of DnaK chaperone team in the cell. So, reduction in the productivity is not due to proteolytic processing of properly folded recombinant streptokinase.

These observations indicate that the major interaction of the DnaK chaperone team may be with nascent polypeptide chain, as the initial translation product emanates from the ribosome. Literature reports have also indicated that DnaK binds to nascent polypeptides emanating from the ribosome and transfer it to the GroEL chaperone team (Hartl and Hayer-Hartl 2002; Sharma et al. 2008). In the present case, the outcome of such an interaction of DnaK chaperone team with the initial translation product of recombinant streptokinase is negative. This step is modeled as chaperone-assisted degradation of initial translation product. The protease FtsH is involved in the DnaK chaperone-assisted degradation. The remaining fraction of the initial translation product (which does not interact with DnaK chaperone team or that which gets dissociated from DnaK chaperone team) gets folded, misfolded or aggregated to produce active folded recombinant protein, misfolded recombinant protein or aggregated recombinant protein, respectively. The misfolded recombinant protein is assumed to be refolded by the GroEL chaperone team to form folded recombinant protein. This assumption is based on the observation that the specific activity of recombinant streptokinase is enhanced during the co-expression of the GroEL chaperone team. The disaggregation of the aggregated recombinant protein through the DnaK chaperone team is also included. The other steps included are the chaperone-assisted degradation of misfolded recombinant proteins by the protease FtsH and chaperone-independent degradation of the misfolded recombinant proteins by the protease HslVU. The schematic of the complete mechanism proposed for the interaction of the recombinant protein with the heat-shock proteins is shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of the mechanism proposed for the interaction of recombinant streptokinase with the major heat-shock proteins in the cell. The major events of recombinant protein synthesis, folding, misfolding and aggregation are represented by solid lines and the chaperone mediated events are represented by dotted lines

Modified model of bacterial heat shock response

To obtain a complete model for the temperature inducible recombinant streptokinase production, the dynamics of the heat shock response has to be coupled with the mechanism of interaction of heat shock proteins and recombinant streptokinase. A detailed mechanistic mathematical model was developed for bacterial heat shock response (Supplementary Material). This model was used to characterize the heat shock response and to simulate the dynamics of the heat shock proteins under various temperature shift conditions. The model proposed in the current work is based on the model proposed by Kurata et al. (2006). They have considered only one of the major chaperones (DnaK) and a protease (FtsH) belonging to the σ32 stress network in their model. The model proposed in this work included the GroEL chaperone team and the ATP-dependent protease HslVU which play a major role in regulating the level of σ32 and in handling the misfolding proteins in the cell (Guisbert et al. 2004, Kanemori et al. 1997). The mechanism of the bacterial heat shock response, the details of the improvements made to the literature model and parameter estimation along with the results of the model simulations are presented in Supplementary Material. The change in the level of heat shock proteins during temperature up-shifts is depicted well by the model simulations (Supplementary Material, Figures SI.2 and SI.3). The model developed for the bacterial heat shock response is coupled to mechanism proposed for the interaction of major heat shock proteins and streptokinase. The schematic of the complete model proposed is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the mechanistic model proposed for temperature-induced recombinant streptokinase over expression in Escherichia coli

Model simulation results

The details of the model structure and the assumptions made in the model are explained in the Materials and methods Section. The list of model components, model equations, parameter values and initial conditions are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 5 respectively.

Comparison of chemical and temperature induction

The model equations were simulated for chemical and temperature induced recombinant streptokinase production. The value of the parameters used for simulating these experimental conditions is shown in Table 5. The simulations predicted a two-fold lower accumulation in temperature-induced system as compared to chemically-induced system. These simulations (Fig. 6a) were found to match qualitatively with the experimental data obtained during chemical and temperature-induced recombinant streptokinase production (Fig. 1c). The relative increase in the level of DnaK chaperone team during temperature induction in the model simulations is shown in Fig. 6b. The model proposed here for the temperature-induced recombinant protein expression is a single cell model and the experimental data is from the recombinant E. coli culture. Hence, only a qualitative comparison can be made between the model simulations and the experimental data.

Fig. 6.

Simulations for chemical and temperature induction. Comparison of the model simulations for streptokinase (a) and DnaK (b) levels during chemical-induction and temperature-induction

Model simulations for the chaperone co-expression

The chaperone co-expression experimental conditions were simulated using the model. The co-expression of DnaK chaperone team and/or GroEL chaperone team was simulated by increasing the transcription rate of the particular chaperone team along with the transcription rate for the recombinant protein. This was then compared with the simulation results when the transcription rate of the recombinant protein alone was increased. It was observed that the model simulations (Fig. 7a, c) were able to qualitatively predict the variation in streptokinase levels observed during the DnaK and GroEL chaperone co-expression experiments (Fig. 7b, d). The results of the model simulations for co-expression of both the chaperone teams (Fig. 7e) were also found to match qualitatively with the experimental results (Fig. 7f). The model simulations were performed for different transcription rates of recombinant protein and chaperones DnaK and GroEL. The qualitative results of the model simulations were found to be similar over a range of the transcription rates (Data not shown). As mentioned earlier, the model simulations were carried out on a single cell basis and thus the experimental data cannot be quantitatively compared with the simulations. However, the simulations were compared with the estimated (refer to Materials and methods) molar concentrations of streptokinase in a single cell from the experimental data.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity of the model simulations to parametric variation was analyzed by varying the model parameters one at a time with the remaining model parameters kept at the initial value. Thirty-three model parameters estimated from different sources in the literature were selected for parameter sensitivity analysis. Parameters like the transcription rates which are tuned to match the steady state level of the proteins in the cell, were not included for sensitivity analysis. Certain other model parameters like efficiency of translation of σ32 (η), and the misfolding rate of the cellular proteins (Kx5) were also excluded in the sensitivity analysis, as these parameters were varied to simulate the different experimental conditions. The change in the parameter values up to ±20% of its original value does not significantly affect the qualitative predictions of the model simulations. The fact that the qualitative model simulations were not affected by small variations in model parameters indicates that the observed simulations results are the reflection of the underlying mechanism and not an artifact of the parameters values. Sensitivity index and normalized sensitivity index for the major state variables are calculated and the parameters which has the maximum effect on these variables were identified (Data not shown). The detailed analysis of these variables would enable us to reduce the model equations and improve the quantitative predictability of the model. However, these aspects have not been addressed in this paper.

Parameter sensitivity analysis, however, was used in this work to identify the critical steps in the mechanism proposed and to identify ways to tackle these critical steps. Substantial variation in the model simulations for chemical-induction and temperature-induction was observed when the model parameters were varied two fold as shown in Fig. 8 (The time profile is shown in Fig. 3, Supplementary Figures). The parameters for which the level of total folded recombinant protein was similar between chemical and temperature-induction experiments were identified. A two-fold increase in the parameters K6, K11, Kmd and Kx2 and a two-fold decrease in the parameters K2, K4, Kx4 and Kpd lead to similar profiles for the total folded recombinant protein during chemical and temperature induction. The detailed analysis of the model variables was performed during the two-fold increase or decrease of these model parameters. Among these eight parameters, the increase in the parameters K11, Kx2 and the decrease in K2 and K4 directly affect the level of σ32. Increase in the parameters K6 and the decrease in the parameter Kx4 indirectly affect the level of σ32 and heat shock proteins by either decreasing the free RNA polymerase in the cell or by increasing the unfolded protein levels in the cell. The model parameters, Kpd (protein degradation rate) and Kmd (mRNA degradation rate), when decreased or increased lead to significantly different levels of all the proteins considered in the model and the accumulation levels of certain proteins were beyond the physiological levels. This emphasizes that the average mRNA and protein degradation rates in the cell may not vary significantly within the cell. However, the degradation rates of the individual mRNA’s and proteins may vary based on the nature and function of the protein.

Fig. 8.

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis. The total folded recombinant protein obtained during chemical induction and temperature induction for two fold increase and two fold decrease in the model parameter values are shown in (a) and (b), respectively

The level of σ32, total DnaK and free DnaK for the two fold increase and decrease of the selected model parameters is shown in Fig. 9 (The complete set of figures are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, Supplementary Figures). The total DnaK chaperone and σ32 levels in the cell for the altered parameter values during temperature-induction were found to be slightly lower than that observed without any change in model parameters. Further, these levels were higher than that observed during the chemical-induction simulations. However, the level of free DnaK chaperone in the cell was found to be significantly affected by the change in these model parameters. Thus, the factors that affect the level of free DnaK chaperone play a crucial role on the productivity of the soluble recombinant streptokinase. This indicates that these model parameters lead to a selective redirection of the DnaK activity and thus resulted in improved productivity even during temperature induced expression.

Fig. 9.

Effect of the variation in selected model parameters on σ32, total DnaK and free DnaK levels in the cell during temperature-induced and chemically induced recombinant streptokinase production

Model validation

To validate the proposed model a σ32 conditional mutant strain was selected for the analysis. This strain (CAG597) produces σ32 at 30°C, but when the temperature is increased to 37 or 42°C the strain becomes a σ32 mutant. This feature of the strain enable us to simulate a condition were there is enough DnaK in the cell but the requirement for DnaK chaperone increases upon temperature up-shift without the increase in the synthesis of DnaK. A situation which leads to a reduction in the free DnaK levels in the cell. The model was simulated for the σ32-conditional-mutant strain. The result of the model simulation for the total folded recombinant protein levels during temperature induction is shown in Fig. 10a. It was observed in the simulations for the σ32-mutant strain that the quantity of total recombinant protein (streptokinase) produced was two-fold higher compared to the quantity of the protein observed in the normal strain. Experiments were then carried out in the σ32 mutant strain to estimate the level of streptokinase produced. It was observed that the experimental results compared well with the model simulations in terms of the increase in the accumulation of soluble streptokinase for the mutant strain (Fig. 10d).

Fig. 10.

Model Validation—Simulations and experimental data of mutant strain. a, b, and c Comparison of the model simulations for the levels of streptokinase, total DnaK and free DnaK in the cell, respectively, during temperature induction in the normal strain BL21 (DE3) and σ32 mutant strain CAG597. d Comparison of the experimental data (shake flask cultivation) for the level of streptokinase produced during temperature induction in the normal strain BL21 (DE3) and σ32 mutant strain CAG597. Western Blot analysis of the DnaK levels in the normal strain BL21 (DE3) and the σ32 mutant strain CAG597 (e) after the shift in cultivation temperature from 30–37°C for temperature induced recombinant streptokinase production. Lane 1–5 corresponds to samples taken 0, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min after the temperature shift. f Densitometric analysis of Western Blot. The band intensities were normalized with zeroth hour sample

The DnaK levels in the σ32 mutant strain after the temperature shift was analyzed by Western Blot. The change in DnaK levels after the shifting the cultivation temperatures from 30 to 37°C in the BL21 (DE3) strain and CAG597 (the σ32-mutant strain) is shown in Fig. 10e. The densitometric analysis of the Western blot showing the DnaK levels normalized to the zeroth hour sample is shown in Fig. 10f. As expected, the down-regulation of σ32 lead to a small reduction in the DnaK levels in the σ32-mutant strain. This was also observed in the model simulations (Fig. 10b). Further, the model simulations also showed a decreased free DnaK levels in the mutant strain (Fig. 10c). Therefore, it could be concluded that the decrease in free DnaK levels in the σ32-mutant strain would have led to an increase in streptokinase production. However, in the σ32-mutant strain, extensive aggregation and proteolytic processing of the recombinant streptokinase was observed (Data not shown).

The alternative transcription factor σ32 plays a vital role in the cell and it is essential for the viability of the cells at higher temperatures. Further, mutating σ32 may affect the cells in several ways and mutating this protein is not a feasible solution for the temperature-inducible production of soluble recombinant proteins, as a lot of proteins transcribed by σ32 also help in protein folding and enhancement of biological activity. Anti-sense mediated down-regulation of σ32 activity was found to enhance the biological activity of Organophosphorus Hydrolase expressed in E. coli (Srivastava et al. 2000). However, the yield of the protein was reduced to 60% of that obtained without the down-regulation of σ32. These observations emphasize that selective redirection of the chaperone activity is a better strategy to enhance the productivity of recombinant proteins.

Discussion

Temperature induction has been used for the production of several recombinant proteins in E. coli. The dynamics of the cellular response during temperature-induced recombinant protein over expression has been referred as a dual stress on the host cell (Harcum and Haddadin 2006). However, the dual stress situation arises mainly due to the nature and properties of the recombinant protein. The aggregation prone recombinant protein like basic human fibroblast growth factor, when induced using a temperature up-shift mechanism, was found to result in a continuous heat shock response (Hoffmann and Rinas 2000). The DnaK level was found to be higher during temperature-induced recombinant protein over-expression compared to the condition where temperature up-shift was done for the non-recombinant strain. This is because of the competition of both the misfolded cellular proteins and the aggregating recombinant protein for DnaK chaperone team. Thus, the DnaK chaperone is not free to down-regulate the heat-shock response by binding to and assisting the degradation of σ32. Further, certain aggregation prone recombinant proteins when expressed in E. coli were observed to induce a heat shock-like response without any temperature up-shift (Kanemori et al. 1994).

In the case of soluble recombinant proteins like recombinant streptokinase the major stress on the cell is due to temperature up shift and not due to the misfolding of the recombinant protein. The up-regulation of the heat shock proteins or the induction of the heat-shock like response was not observed when recombinant streptokinase alone was over-expressed by chemical induction. However, when temperature up-shift was used as an induction mechanism, the up-regulated heat shock chaperones were found to influence the productivity of the soluble recombinant streptokinase.

There are several reports in literature citing the effect of chaperones on recombinant protein expression, solubilization and folding in E. coli based expression systems. Although there have been many experimental investigations on the effects of chaperone co-expression on aggregating recombinant proteins (Caspers et al. 1994; Mogk et al. 1999; Nishihara et al. 2000), there are very few such studies on soluble recombinant proteins (Kohda et al. 2002). Our experimental investigations, involving co-expression of major chaperone teams, found that the role played by the molecular chaperones was different for a soluble recombinant protein as compared to the literature reports on aggregation-prone recombinant proteins (which often form inclusion bodies). Kohda et al. (2002) observed that coexpression of DnaK chaperone team lead to a significantly reduced level of the active recombinant protein (glutamate racemase) and attributed this to the accumulation of partially folded intermediates due to the absence of large quantities of GroEL chaperone team. However, in the present case, the DnaK chaperone team seems to impair productivity of streptokinase even in the presence of GroEL chaperone team and this indicates that the unavailability of GroEL chaperone team suggested by Kohda et al. could not be the reason for the reduced productivity. Enhancement in the biological activity of recombinant proteins during the co-expression of folding accessories has been extensively reported (Georgiou and Valax 1996). The enhancement in the activity of the recombinant protein is generally brought about by increasing the solubility of the recombinant protein (Caspers et al. 1994; Baneyx and Palumbo 2003). However, the enhancement in the activity of highly soluble recombinant protein often results from better folding of the recombinant protein. Further, such a state of the protein cannot be generally quantified unless the recombinant protein possesses an enzymatic activity, as in the case of recombinant streptokinase or glutamate racemase (Kohda et al. 2002).

Further, based on isolated experimental investigations of individual chaperones, it is very difficult to predict the combined effect of all the major chaperones on a particular recombinant protein, given that the outcome depends on the recombinant protein characteristics as well as the dynamics of the stress response network. In this context, it would be more appropriate to formulate mathematical models which can simulate the network dynamics well and give insights on key parameters affecting the productivity as well as the quality of the recombinant protein. However, given the large number of heat-shock and other host cell proteins which interact with the recombinant protein, modeling and simulation can become a complex and even intractable task. Therefore, it may be essential to isolate the important components of a network and its interactions with a recombinant protein in order to simplify the model and its corresponding simulations.

This work makes a modest beginning in this direction by formulating a deterministic model-based approach for investigating the effect of heat shock response on a soluble recombinant protein, induced by a temperature up-shift. A mechanistic network model is proposed for the interaction of the major heat shock proteins and the soluble recombinant streptokinase. The framework presented is generally applicable for the chaperone-mediated folding, aggregation, dis-aggregation and proteolysis of recombinant proteins. This model was coupled to a modified model of heat-shock response, in order to simulate the chaperone effects on temperature-induced recombinant protein production. The model simulations were found to have strong qualitative agreement with the experimental results. The sensitivity analysis for the model parameters, together with the model simulations for the σ32 mutant strain have indicated that down-regulation of σ32 (and hence DnaK) levels in the cell could result in enhanced productivity of recombinant streptokinase during temperature-induced expression. Further, the sensitivity analysis has also shown that selective down-regulation of the DnaK chaperone level or activity could lead to enhancement in the productivity.

Thus, our theoretical investigations have shown that it is the amount of free DnaK chaperone (and not the total DnaK level per se) that has the most significant effect on the productivity of the soluble recombinant streptokinase. Such insights may be difficult to capture by purely experimental investigations of chaperone co-expression, thus making it difficult to design rational strategies for enhancing cellular productivity. Therefore, a model-based approach may be more justified in certain circumstances, where protein characteristics and its interaction with host cell proteins are quantitatively understood. Careful examination of these model parameters could allow design of expression vectors or experimental strategies which are capable of operating at multiple values for these model parameters and would be very useful in enhancing the productivity of recombinant proteins.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. A. Gopalakrishna (Department of Biotechnology, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, India) for providing the pGKJE6 plasmid. We are also grateful to Dr. Behnaz Parhami-Seren (University of Vermont, Burlington) for providing us with monoclonal antibody for streptokinase.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11693-009-9021-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Balaji Balagurunathan, Email: balaji.chem@gmail.com.

Guhan Jayaraman, Phone: +91-44-22574108, FAX: +91-44-22574102, Email: guhanj@iitm.ac.in.

References

- Azuaga AI, Dobson CM, Mateo PL, Conejero-Lara F (2002) Unfolding and aggregation during the thermal denaturation of streptokinase. Eur J Biochem 269:4121–4133. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03107.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- Balagurunathan B, Jayaraman G (2008) Enhancement of stability of recombinant streptokinase by intra-cellular expression and single step purification by hydrophobic interaction chromatography. Biochem Eng J 39(1):84–90. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2007.08.021 [DOI]

- Baneyx F (1999) Recombinant protein Expression in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol 10:411–421. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(99)00003-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baneyx F, Mujacic M (2004) Recombinant protein folding and misfolding in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol 22(11):1399–1408. doi:10.1038/nbt1029 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baneyx F, Palumbo JL (2003) Improving heterologous protein folding via molecular chaperone and foldase co-expression. Methods Mol Biol 205:171–197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Caspers P, Stieger M, Burn P (1994) Overproduction of bacterial chaperones improves the solubility of recombinant protein tyrosine kinases in Escherichia coli. Cell Mol Biol 40:635–644 [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay R, Roy S (2002) DnaK-Sigma32 interaction is temperature dependent—implication for the mechanism of heat-shock response. J Biol Chem 277(37):33641–33647. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203197200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gamer J, Multhaup G, Tomoyasu T, McCarty JS, Rudiger S, Schonfeld HJ, Schirra C, Bujard H, Bukau B (1996) A cycle of binding and release of the DnaK, DnaJ and GrpE chaperones regulates the activity of the Escherichia coli heat-shock transcription factor σ32. EMBO J 15(3):607–617 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Georgiou G, Valax P (1996) Expression of correctly folded proteins in Escherichia coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol 7:190–197. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(96)80012-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grigorova IL, Phleger NJ, Mutalik VK, Gross CA (2006) Insights into transcriptional regulation and sigma competition from an equilibrium model of RNA polymerase binding to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(14):5332–5533. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600828103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gromiha MM, Thangakani AM, Selvaraj S (2006) FOLD-RATE: prediction of protein folding rates from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W70–W74. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guisbert E, Herman C, Lu CZ, Gross CA (2004) A chaperone network controls the heat-shock response in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev 18:2812–2821. doi:10.1101/gad.1219204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gupta JC, Jaisani M, Pandey G, Mukherjee KJ (1999) Enhancing recombinant protein yields in Escherichia coli using the T7 system under the control of the heat inducible λPL promoter. J Biotechnol 68:125–134. doi:10.1016/S0168-1656(98)00193-X [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harcum SW, Haddadin FT (2006) Global transcriptome response of recombinant Escherichia coli to heat-shock and dual heat-shock recombinant protein production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 33:801–814. doi:10.1007/s10295-006-0122-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hartl UF, Hayer-Hartl M (2002) Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295:1852–1858. doi:10.1126/science.1068408 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann F, Rinas U (2000) Kinetics of heat-shock response and inclusion body formation during temperature induced production of basic-fibroblast growth factor in high-cell-density cultures of recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Prog 16:1000–1007. doi:10.1021/bp0000959 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann F, Rinas U (2004) Roles of heat-shock chaperones in the production of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 89:143–161 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann F, Weber J, Rinas U (2002) Metabolic adaptation of Escherichia coli during temperature-induced recombinant protein production: 1. Readjustment of metabolic enzyme synthesis. Biotechnol Bioeng 80:313–319. doi:10.1002/bit.10379 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kanemori M, Mori H, Yura Y (1994) Induction of heat-shock proteins by abnormal proteins results from stabilization and not increased synthesis of σ32 in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 176(18):5648–5653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kanemori M, Nishihara K, Yanagi H, Yura T (1997) Synergistic role of HslVU and other ATP-dependent proteases in controlling the in vivo turnover of σ32 and abnormal proteins in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 179(23):7219–7225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kohda J, Endo Y, Okumura N, Kurokawa Y, Nishihara K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Fukuda H, Kondo A (2002) Improvement of productivity of active form of glutamate racemase in Escherichia coli by coexpression of folding accessory proteins. Biochem Eng J 10:39–45. doi:10.1016/S1369-703X(01)00154-1 [DOI]

- Koller MF, Baici A, Humber M, Christen P (2002) Detection of a very rapid first phase in complex formation of DnaK and peptide substrate. FEBS Lett 520:25–29. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02752-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kurata H, El-Samad H, Iwasaki R, Ohtake H, Doyle JC, Grigorova I, Gross CA, Khammash M (2006) Module based analysis of robustness tradeoffs in the heat-shock response system. PLOS Comput Biol 2(7):663–675. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685. doi:10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lin Z, Schwartz F, Eisenstein E (1995) The hydrophobic nature of GroEL—substrate binding. J Biol Chem 270:1011–1014. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.3.1011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maeda H, Fujita N, Ishihama A (2000) Competition between seven Escherichia coli sigma subunits. Nucleic Acids Res 28(18):3497–3503. doi:10.1093/nar/28.18.3497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Makrides SC (1996) Strategies for achieving high-level expression of genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev 60:512–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mogk A, Tomoyasu T, Goloubinoff P, Rudiger S, Roder D, Langen H, Bukau B (1999) Identification of thermo labile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J 18:6934–6949. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.24.6934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Neidhardt FC (1987) Chemical composition of Escherichia coli. In: Neidhardt FC, Ingraham JL, Low KB, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger HE (eds) Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington, DC, pp 3–6

- Nishihara K, Kanemori M, Kitagawa M, Yanagi H, Yura T (1998) Chaperone coexpression plasmids: differential and synergistic roles of DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE and GroEL-GroES in assisting folding of an allergen of Japanese cedar pollen, Cryj2, in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 64:1694–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nishihara K, Kanemori M, Yanagi H, Yura T (2000) Over-expression of trigger factor prevents aggregation of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:884–889. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.3.884-889.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parhami-Seren B, Krudysz J, Tsantili P (2002) Affinity panning of peptide libraries using anti-streptokinase monoclonal antibodies: selection of an inhibitor of plasminogen active site. J Immunol Methods 267:185–198. doi:10.1016/S0022-1759(02)00183-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam S, Gautam P, Mukherjee KJ, Jayaraman G (2007) Effects of post-induction feed strategies on secretory production of recombinant streptokinase in Escherichia coli. Biochem Eng J 33:33–41. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2006.09.019 [DOI]

- Roe JH, Burgess RR, Record MT (1985) Temperature dependence of the rate constants of the Escherichia coli RNA Polymerase-Lambda PR promoter Interaction: assignment of the kinetics steps corresponding to Protein conformational change and DNA opening. J Mol Biol 184:441–453. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(85)90293-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Seeger A, Schneppe B, McCarthy JEG, Deckwer W-D, Rinas U (1995) Comparison of temperature and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalacto-pyranoside induced synthesis of basic fibroblast growth factor in high cell density cultures of recombinant Escherichia coli. Enzyme Microb Technol 17:947–953. doi:10.1016/0141-0229(94)00123-9 [DOI]

- Sharma S, Chakraborthy K, Muller BK, Astola N, Tang YC, Lamb DC, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartyl FU (2008) Monitoring protein conformation along the pathway of chaperone-assisted folding. Cell 133:141–153. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Siegenthaler RK, Christen P (2006) Tuning of DnaK chaperone action by non-native protein sensor DnaJ and thermo sensor GrpE. J Biol Chem 281(45):34448–34456. doi:10.1074/jbc.M606382200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Srivastava R, Cha HJ, Peterson MS, Bentley WE (2000) Antisense down-regulation of σ32 as a transient metabolic controller in Escherichia coli: effects on yield of active Organophosphorus Hydrolase. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:4366–4371. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.10.4366-4371.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tabor S, Richardson CC (1985) A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:1074–1078. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ujvari A, Martin CT (1996) Thermodynamic and kinetic measurements of promoter binding by T7 RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 35:14574–14582. doi:10.1021/bi961165g [DOI] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh B, Arifuzzaman M, Mori H, Taguchi T, Ohmiya Y (2004) GroEL chaperone binding to Beetle luciferases and the Implications for refolding when co-expressed. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68(10):2096–2103. doi:10.1271/bbb.68.2096 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weber J, Hoffmann F, Rinas U (2002) Metabolic adaptation of Escherichia coli during temperature-induced recombinant protein production: 2. redirection of metabolic fluxes. Biotechnol Bioeng 80:320–330. doi:10.1002/bit.10380 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yazdani SS, Mukherjee KJ (2002) Continuous-culture studies on the stability and expression of recombinant streptokinase in Escherichia coli. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 24:341–346. doi:10.1007/s004490100221 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.