Abstract

NO is an important regulatory molecule in eukaryotes. Much of its effect is ascribed to the action of NO as a signalling molecule. However, NO can also directly modify proteins thus affecting their activities. Although the signalling functions of NO are relatively well recognized in plants, very little is known about its potential influence on the structural integrity of plant cells. In this study, the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, and the recycling of wall polysaccharides in plants via the endocytic pathway in the presence of NO or NO-modulating substances were analysed. The actin cytoskeleton and endocytosis in maize (Zea mays) root apices were visualized with fluorescence immunocytochemistry. The organization of the actin cytoskeleton is modulated via NO levels and the extent of such modulation is cell-type specific. In endodermis cells, actin cables change their orientation from longitudinal to oblique and cellular cross-wall domains become actin-depleted/depolymerized. The reaction is reversible and depends on the type of NO donor. Actin-dependent vesicle trafficking is also affected. This was demonstrated through the analysis of recycled wall material transported to newly-formed cell plates and BFA compartments. Therefore, it is concluded that, in plant cells, NO affects the functioning of the actin cytoskeleton and actin-dependent processes. Mechanisms for the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton are cell-type specific, and such rearrangements might selectively impinge on the functioning of various cellular domains. Thus, the dynamic actin cytoskeleton could be considered as a downstream effector of NO signalling in cells of root apices.

Keywords: Actin, cell wall–cytoskeleton interactions, endocytosis, maize, nitric oxide, Zea mays

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a multifunctional ancient signalling molecule active in all organisms, from bacteria to higher plants and mammals (Stamler et al., 1992). Although the history of research on NO signalling in plants is spread over only a few years, the number of processes and physiological responses found to be regulated and mediated by NO is breathtaking (reviewed by Wojtaszek, 2000; Lamattina et al., 2003; Neill et al., 2003; Wendehenne et al., 2004; Arasimowicz and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2007). NO is involved, for example, in defence reactions (reviewed by Hong et al., 2008), tropisms (Hu et al., 2005), flowering (He et al., 2004), regulation of stomatal aperture (reviewed by Neill et al., 2008a), xylem formation (Gabaldón et al., 2005), and stress response and adaptation (Valderrama et al., 2007).

In general, cellular responses can be evoked by two different, but non-exclusive, NO-dependent mechanisms. NO can interfere with the functioning of signal transduction pathways or can modify proteins structurally via the direct addition of the NO molecule itself or NO-derived molecules (Kone, 2006; Sawa et al., 2007) to amino acids or protein cofactors. Similarly to the situation in animals (Wendehenne et al., 2001), the NO signal transduction pathway is mediated by the activation of cGMP synthesis, changes in cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations, and activation of various protein kinases (Neill et al., 2003; Arasimowicz and Floryszak-Wieczorek, 2007). These secondary messengers are active, for example, in the guard cells of stomata showing complex cross-talks with ABA and H2O2 signalling pathways (reviewed by Neill et al., 2008a); in roots during adventitious (Pagnussat et al., 2003, 2004; Lanteri et al., 2006) and lateral (Correa-Aragunde et al., 2006) root formation where they cross-talk with the auxin signalling pathway; and in tip-growth of rhizoids of fern Ceratopteris richardii (Salmi et al., 2007) as well as of plant root hairs and pollen tubes (Prado et al., 2004; Lombardo et al., 2006). Recent data suggest that phospholipids, particularly phosphatidic acid, might also be an important component of the NO signalling pathways (Laxalt et al., 2007; DiStéfano et al., 2008; Lanteri et al., 2008).

The most common structural modifications of proteins by NO are S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues (Hess et al., 2005), and nitration of aromatic amino acids, usually tyrosines (Monteiro, 2002). It is now thought that NO is part of a universal redox-based signalling mechanism and such alterations could be regarded as important post-translational modifications (Stamler et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2006b). Not much is known about them in plants. Pioneering proteomic identifications of S-nitrosylated proteins have already been undertaken, providing some interesting clues for NO action in plant growth and development (Lindermayr et al., 2005), and in defence responses (Romero-Puertas et al., 2008).

Cytoskeletal proteins seem to be good candidates for NO-dependent regulatory mechanisms. NO-related structural modifications, affecting protein–protein interactions, could be very important here. Indeed, in animal cells, tubulin (Tedeschi et al., 2005), tubulin-associated proteins (Stroissnigg et al., 2007) and actin (Banan et al., 2001; Ke et al., 2001; Aslan et al., 2003) have been shown to be potential targets for NO. Similarly, some actin-dependent processes, like vesicle trafficking (Matsushita et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006a; Kang-Decker et al., 2007), have been shown to be affected by NO. As for the plant cytoskeleton, only a few effects, based on proteomic data (Lindermayr et al., 2005), have been suggested. In this study, it was decided to take a closer look at the relationship between NO and the functioning of the actin cytoskeleton in plants. It is reported that the organization of the actin cytoskeleton is modulated via NO levels in maize (Zea mays) root apices, and that the extent of such modulation is cell-type and developmental stage-specific. Some of the consequences of the NO-dependent actin rearrangements were also investigated further, focusing on endocytosis. It is demonstrated that in maize root apices actin-dependent endocytosis is also modulated by exogenous NO.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Maize (Zea mays L. cv. Careca S230) caryopses were imbibed under running tap water for 16 h and germinated in moistened rolls of filter paper for 2 d at 25 °C in the dark.

Chemicals and stock solutions

All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise stated. Five mM sodium acetate buffer pH 5.8 (NaOAc) was used as a control as well as a solvent for all treatments. SNAP (Molecular Probes) and its inactive analogue SAP, GSNO, spermine NONOate, SIN-1, cPTIO, L-NMMA, and 8-Br-cGMP were dissolved in 5 mM NaOAc just before application to obtain 5 mM stocks. For Brefeldin A and for NaNO2, 35 mM and 100 mM stock solutions were used. ODQ was reconstituted in DMSO as a 10 mM stock solution. For the analyses of the effects evoked by reactive oxygen species, the glucose/glucose oxidase (191 U mg−1; Fluka) system was used with stock solutions of 50 mM glucose in water, and 0.25 U μl−1 glucose oxidase in 5 mM NaOAc.

Experimental layout

All experiments were carried out using the layout described by Wojtaszek et al. (2005). Briefly, apical root segments, 4–6 mm, were excised from straight, 40–70 mm long, primary roots and fully submerged in deionized water. They were kept at room temperature (RT) on a rotary shaker until the start of the experiment. Following aspiration of water, root apices (15–20 per treatment) were transferred to 35 mm Petri dishes containing 5 mM NaOAc. After the addition of respective chemicals, root apices were infiltrated under vacuum for 90 s (time-point zero). They were then placed again on a rotary shaker set at 70 rpm and incubated for the time indicated in dim light at RT. Four root segments per treatment were removed at time-points 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. For the experiment showing time-lapse influence of SNAP on actin cytoskeleton, SNAP was re-added at time-points 2 h and 4 h. Root segments were incubated for additional 2 h and processed as above.

For the experiments utilizing BFA, where the relative timing of addition of BFA and SNAP was important, application of the NO donor was considered as time-point zero. Experimental variants were designed where BFA was added at various time points in relation to time-point zero: an hour before, at the same time, or an hour after SNAP application. Samples were collected and processed as above.

Immunocytochemistry

Excised root segments were processed for immunofluorescence microscopy according to Wojtaszek et al. (2005). Following dehydration in a graded ethanol series diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), root segments were embedded in low-melting-point Steedman's wax (Baluška et al. 1992). For immunolabelling, 10 μm sections were incubated for 1 h at RT with anti-maize-pollen-actin polyclonal antibody (Baluška et al., 2001a) or anti-RG II-B-RG II polyclonal antibody (Matoh et al., 1998) diluted 1:100 with PBS containing 0.1% (w/v) BSA. Following rinsing with PBS (10 min), sections were incubated for 1 h at RT with goat anti-rabbit IgG, (Fab’)2 fragments conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate, diluted 1:100 with PBS containing 0.1% BSA. A further wash with PBS (10 min) preceded a 10 min staining with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; 100 μM in PBS). Following rinsing in PBS (10 min), sections were treated for 10 min with 0.01% (w/v) toluidine blue in PBS. Mounting was done using anti-fading reagent based on p-phenylenediamine (Baluška et al., 1992). Sections were examined with a Zeiss Axiovert 405M inverted microscope equipped with epifluorescence and standard FITC excitation and barrier filters (BP 450–490, LP 520). Images were acquired using a Zeiss AxioCam HRc camera operating under AxioVision 3.1 software, and further processed using Adobe PhotoShop. Enhancement of images was performed with Iterative Deconvolution tool for ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Measurements and statistical analysis

Images were analysed with ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). For statistical analysis, measurements for each experimental variant were performed in duplicate on 50 randomly selected cortex cells from the root transition zone. The areas of cells and BFA compartments were free-hand traced and measured, and number of compartments per cell was counted. All vesicular structures visible after labelling with anti-(RG II-B-RG II) antibodies under fluorescence microscope were considered as BFA compartments. Finally, for each cell, the percentage of cell area covered by BFA compartments was estimated. The statistical analyses were performed with STATISTICA ver. 7.1 software (StatSoft). Due to non-normality within treatments and to variance inequality among treatments, data were analysed by the non-parametric tests on ranks. Pairwise and multiple comparisons among experimental variants were consequently executed to test whether treatments varied from each other by one-way analysis of variance according to Kruskal–Wallis. Comparison between control cells (BFA-treated) and test cells (SNAP-treated) was performed using Mann-Whitney U test. A probability of P ≤0.01 was considered as representing a significant difference in this study. All data given are means ±SE.

Results

The importance of NO donor identity

To analyse the changes in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton, several donors were tested. These compounds differ in their mode of action and type of molecules released. S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine (SNAP) release the NO radical (•NO) spontaneously in aqueous solutions at a pH of about 7. Although GSNO is more stable than SNAP, it is the latter which is much more effective in releasing NO, both in vitro and in vivo (Floryszak-Wieczorek et al., 2006). As an additional control, S-acetyl-DL-penicillamine (SAP), not carrying a nitrosyl group, was used as an inactive analogue of SNAP. Spermine NONOate is another relatively stable NO donor, but it differs from the former in that it dissociates in aqueous solutions to release two NO molecules. Two other systems have been tested to check the putative involvement of other reactive species. During the course of decomposition, morpholine sydnonimine (SIN-1) first releases superoxide (ıNO2ı) and then NO. Thus, in addition, a typical ROS-generating system, glucose oxidase+glucose (GO+Glc), was also used. Sodium nitroprusside, commonly applied as an NO donor, was not tested as it appears to be a rather ineffective NO-donor (Murgia et al., 2004; Lindermayr et al., 2005; Floryszak-Wieczorek et al., 2006), and, more importantly, it generates nitrosonium cations (Wojtaszek, 2000), which might lead to effects opposite to that evoked by donors releasing NO radicals (Murgia et al., 2004).

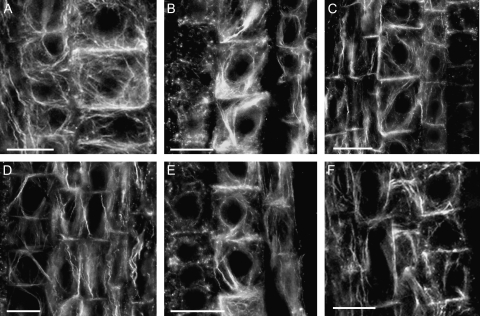

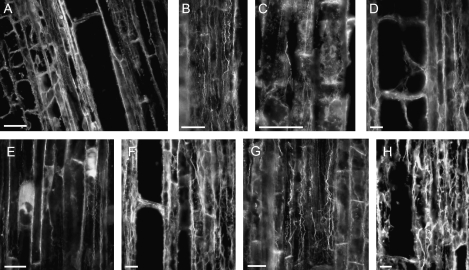

The transition zone at the maize root apex seems to be the most sensitive to the application of donors. Comparative analysis revealed, however, that the effects evoked by various compounds were rather complex and variable. Cells differentiating into the endodermal layer demonstrated the most profound changes in the organization of actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 1). Typically, thicker actin cables were found around centrally maintained nuclei. When the cells were starting to elongate, these actin bundles were stretched parallel to the axis of elongation. Special functional domains highly enriched in actin were also clearly visible near cross walls (see also Wojtaszek et al., 2007). This organization of F-actin was not affected by an inactive molecule—SAP (compare Fig. 1A with Figs 2A, 3E or 4A). From among the NO donors, the application of SNAP evoked the most profound actin reorganization. Previous in vitro data indicated that the maximal NO release from SNAP occurs at about 2 h and reaches 30 μM (Floryszak-Wieczorek et al., 2006). Here, in maize root apices 2 h after SNAP addition, the orientation of major actin cables changed to oblique in relation to the apical–basal root axis and the domains of actin enrichment became precisely focused at opposite cell corners. Interestingly, when compared with the control, endodermal cells became strongly depleted in actin at the cross-walls (Fig. 1B). F-actin reorganization leading to oblique orientation of actin cables was also induced by other NO-releasing substances, like spermine NONOate (Fig. 1C) or GSNO (Fig. 1D). It should be noted, however, that depletion of actin at the cross-walls was, in both cases, much weaker than that for SNAP (compare, for example, Fig. 1B and C). In that respect, these two compounds were similar to SIN-1 and the ROS-generating system, which also did not change actin organization at the cross-walls. Even more importantly, SIN-1 as well as the GO+Glc system did not induce changes in the orientation of actin cables (Fig. 1E and F, respectively). Because of its effects on actin organization, SNAP was selected as a NO donor for further experiments.

Fig. 1.

Different NO donors evoke reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in cells of the transition zone of maize root apices to variable extents. (A–F) Fluorescence micrographs of protoendodermal cell files of maize root apices treated for 2 h with 200 μM SAP (A), an inactive analogue of SNAP; compounds releasing NO only: 200 μM SNAP (B), 200 μM spermine NONOate (C), 500 μM GSNO (D); compound releasing both NO and ıNO2ı: 200 μM SIN-1 (E), or a ROS-generating system, 200 μM glucose+0.5 U ml−1 glucose oxidase (F). Note the differences in the net orientation of actin cables and in the extent of actin labelling at the cross-wall domains. Bars=20 μm.

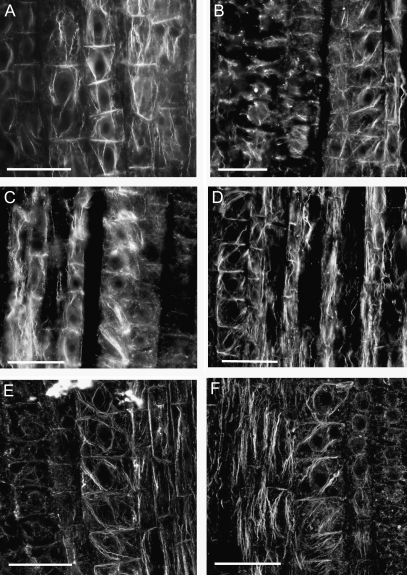

Fig. 2.

NO-induced changes in the organization of actin cytoskeleton are reversible. Upon NO action, the normal, net longitudinal orientation of actin cables (A) changes to oblique (B, C), while cross-walls became depleted of actin (C). Organization of actin cytoskeleton returns to normal when the NO donor is completely used up (D). Maize root apices were treated with 200 μM SNAP, and samples were collected for immunocytochemical analyses at 0 min (A), 30 min (B), 2 h (C), and 5 h (D) after the addition of the NO donor. Re-addition of the NO donor after 2 h (E) and 4 h (F) followed by 2 h incubation resulted in prolonged reorganization of actin filaments. Bars=40 μm.

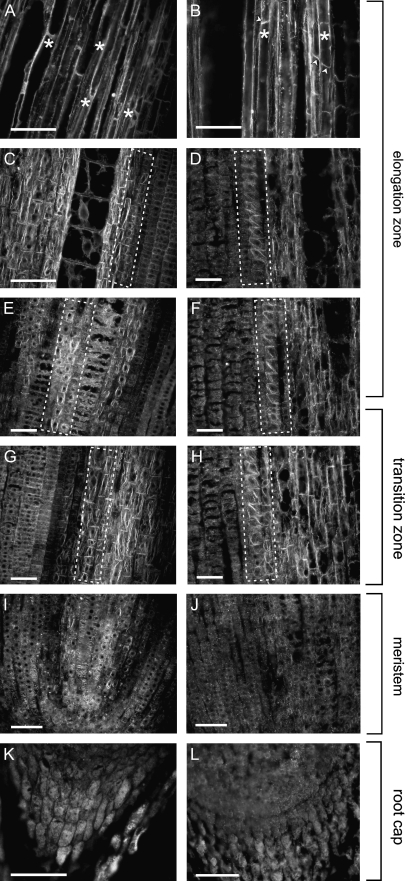

Fig. 3.

Rearrangements of actin microfilaments in response to the presence of NO are cell type- and developmental stage-specific. An overview of the variability in the structural actin organization in cells of various root growth zones is presented. Root apices were treated with 200 μM solutions of either the NO donor SNAP (right column) or its inactive analogue SAP (left column). Micrographs are taken from samples collected after 2 h of incubation. In all images roots are oriented with the root cap facing the bottom of the figure. Endodermal cells are indicated by dashed line (C–H), parenchymatous cells with differential actin distribution with asterisks (A, B) and cross-walls enriched in actin with arrowheads (B). Bars=40 μm (A–H) or 100 μm (I–L).

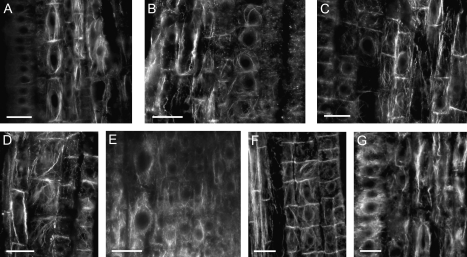

Fig. 4.

Organization of the actin cytoskeleton in cells of the transition zone of maize root apices treated with various NO modulators. All images are for samples taken after 2 h of treatment with: control solution (A), 250 μM SNAP (B), 200 μM cPTIO (C), 50 μM ODQ (D), 100 μM 8Br-cGMP (E), 250 μM SNAP in the presence of 50 μM ODQ (F), or 1 mM NaNO2 (G). Bars=20 μm.

Reversibility and cell-type specificity of NO action

To be treated as a signalling molecule, NO should act transiently, and evoke responses which are cell-type specific. These two points have been addressed through the time-course analysis (Fig. 2) of cellular responses at various growth zones of maize roots (Fig. 3).

Three time-points have been chosen for microscopic observations of maize root apex cells. It was assumed that, at 30 min, the actin organization would only be slightly changed. The most obvious modifications should be seen at 2 h, while after 5 h, when most of NO donor is decomposed (t1/2=3 h for SNAP in vitro; Floryszak-Wieczorek et al., 2006), changes in the organization of the cytoskeleton should become less visible and more similar to the initial, typical alignment. As a further control, an inactive SNAP analogue was used to exclude potential changes evoked by the technical layout of the experiments, for example additional mechanical stimuli resulting from the shaking of root samples. As described above, in SAP-treated roots actin organization in early endodermal cells remained normal (Fig. 1A) and comparable with controls (Fig. 2A) while SNAP treatment induced the reorientation of actin cables and the disappearance of actin labelling at the cross-walls (Fig. 2B, C). In SNAP-treated cells, actin labelling revealed characteristic time- and cellular-domain-dependent patterns. Reorientation of actin cables from parallel to oblique was a relatively quick and stable response to NO application as it was visible in samples taken at all time-points. However, the strength of labelling, reflecting most probably the thickness of cables and the frequency of their appearance in particular areas of the cell, changed in a time-dependent manner. It was the strongest at 2 h, and much weaker both at 30 min and 5 h (Fig. 2B–D). F-actin enrichment at the cross-walls was opposite. Depletion of F-actin in those domains progressed from 30 min, being strongest at 2 h, with subsequent regeneration and establishment of actin labelling after 5 h (Fig. 2B–D). This ‘cycle’ of actin organization can be disturbed by further addition of the NO donor. Re-addition of the NO donor after 2 h (Fig. 2E) and 4 h (Fig. 2F) followed by 2 h incubation supported the strong oblique orientation of actin cables.

F-actin organization was compared in different root growth zones and in different cell types within those zones. Based on the above data, analyses were done on root samples collected 2 h after SNAP application. No changes in F-actin could be found in cells of the maize root cap (Figs 3K, L) and meristematic zone (Figs 3I, J). As described earlier (see Fig. 1), cells of the maize root transition zone reacted most strongly to the presence of exogenous NO, and the observed changes in actin organization were basically limited to the axial cell files which would develop into the endodermal layer (Fig. 3C–H). Moving basally along the maize root, visible changes in the organization of F-actin were noted in the vacuolated cells of the root elongation zone. The presence of NO evoked the redistribution of F-actin in parenchymatous cells. The concentration and pattern of labelling of F-actin situated along the longitudinal walls were not changed, while those of actin near the cross-walls were significantly enhanced (compare Fig. 3A and B).

NO modulation and action

As plants function in ‘an open system’ with respect to NO (Yamasaki, 2005), at least several possible mechanisms of NO generation, both enzymatic and non-enzymatic (Wojtaszek, 2000; Bethke et al., 2004), have been identified. Similarly, two major modes of NO action are usually recognized: (i) directly as a radical molecule alone or after transformation into other reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, and (ii) through specific modification of proteins. Observations that the organization of actin cytoskeleton might be NO-dependent raise questions about the origin of NO and the mechanisms of F-actin reorganization. These were addressed in a set of experiments utilizing compounds known to interfere with either NO metabolism or NO signalling pathways. 2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide (cPTIO) reacts stoichiometrically with NO and acts as an effective NO scavenger, interfering with all possible modes of NO action. NG-methyl-l-arginine (L-NMMA) is a potent inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in mammalian systems, while sodium nitrite could be treated as a potential NO source in plants (Bethke et al., 2004). On the other hand, 1-H-(1,2,4)-oxadiazolo-[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), an inhibitor of NO-sensitive guanylate cyclase, and 8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Br-cGMP), a more stable analogue of cGMP, and the product of this cyclase, both affect the functioning of NO-dependent signalling pathway(s).

Modulation of NO content in roots resulted in cell type- and developmental stage-specific actin reorganization in maize root apices (Table 1; Figs 4, 5). In the presence of SNAP, protoendodermal cells of the transition zone reorient F-actin cables and their cross-wall domains become depleted of actin (Figs 1B, 2C, 4B). Carboxy-PTIO reversed this reaction completely as the alignment of actin cables as well as the actin enrichment of cross-wall domains remained normal (Table 1; Fig. 4C). Interestingly, differences in the mechanisms of NO-dependent actin reorganization could be seen after the application of ODQ when the labelling at the cross-walls indicated the presence of F-actin while at the same time the orientation of actin cables became oblique (Fig. 4D). Parallel application of both SNAP and ODQ, or treatment with 8-Br-cGMP produced actin organization resembling the one found in untreated root apices (Table 1; Fig. 4E, F). In the elongation zone, the presence of exogenous NO evoked the enrichment of cross-wall domains with actin and the formation of long actin cables in maize roots (Table 1; Fig. 5B). Scavenging of NO with cPTIO induced the appearance of diffused actin labelling (Fig. 5C). Individual application of two compounds, affecting in opposite ways the guanylate cyclase-dependent signalling pathway, induced the formation of different actin arrangements. ODQ, which inhibits the pathway, evoked the appearance of actin ‘clouds’ suggesting complete F-actin depolymerization. Interestingly, in maize, these clouds were always polarly localized at the basal side of elongated root cells near their cross-walls (Fig. 5E). This might indicate that actin ‘clouds’ originated from F-actin present at the cross-wall domains. This suggestion is supported by the observation that actin ‘clouds’ were not visible in maize root apices treated with the mixture of SNAP and ODQ (Fig. 5G). On the other hand, application of 8-Br-cGMP led to the formation of actin cables, very sharp in appearance, and the focused actin-enriched domains at the cross-walls (Fig. 5F).

Table 1.

Cells of maize root apices react to the presence of NO modulators in a cell type- and developmental stage-specific manner

| Compound used | Root zone |

Comments | |

| Transition | Elongation | ||

| 250 μM SNAP | +++ | + | Strong reorientation of actin cables in protoendodermal cells; formation of long actin cables in elongated cells, and cross-wall domains enriched with actin |

| 1 mM NaNO2 | + | + | Slight disorganization of actin in both zones with prevalence of longitudinal actin cables, but in the elongation zone not so long as in cells treated with SNAP or 8-Br-cGMP |

| 200 μM cPTIO | − | +++ | Complete reversal of SNAP action in transition zone; diffused organization of actin in elongated cells, and loss of actin labelling at the cross-walls |

| 100 μM L-NMMA | + | ++ | Formation of very short actin bundles in transition zone cortex cells; long, undulated actin cables, accompanied by a distinct network of shorter microfilaments, in elongated cells; the latter transform into diffused actin after prolonged treatment |

| 50 μM ODQ | + | +++ | Actin reorganizes its orientation in protoendodermal cells, but actin-enriched domains at the cross-walls are still visible; induction of actin depolymerization in elongation zone (appearance of ‘clouds’ of depolymerized actin in the basal part of elongated cells) |

| 100 μM 8-Br-cGMP | − | ++ | Normal actin organization in cells of transition zone; effects in elongation zone similar to those evoked by SNAP |

| 250 μM SNAP+50 μM ODQ | − | + | Normal organization of actin in protoendodermal cells; slight enrichment in actin at cross-walls domains in elongated cells |

Roots were incubated with respective compounds, and sampled for immunocytochemistry at various time points. Data on changes in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton in cells of two root zones are for samples collected after 2 h of treatment, when the maximal reaction to SNAP as the NO donor is normally observed. The observed effects varied from strong (+++) to weak (+). Cases where the organization of actin remains unaffected are indicated by (−). Exemplary images illustrating the observed changes are assembled in Figs 4 and 5.

Fig. 5.

Organization of the actin cytoskeleton in cells of the elongation zone of maize root apices treated with various NO modulators. All images are for samples taken after 2 h of treatment with: control solution (A), 250 μM SNAP (B), 200 μM cPTIO (C), 1 mM NaNO2 (D), 50 μM ODQ (E), 100 μM 8Br-cGMP (F), 250 μM SNAP in the presence of 50 μM ODQ (G) or 100 μM L-NNMA (H). Bars=20 μm.

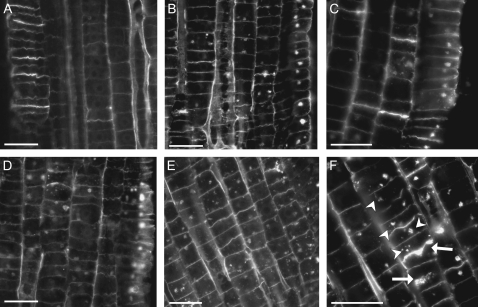

NO, actin cytoskeleton, and vesicle trafficking

Cross-wall domains function as sites of intercellular communication as well as domains of intensive endocytosis and vesicle recycling (Baluška et al., 2005). Modulation of F-actin enrichment at those domains by NO suggested that the process of membrane trafficking might also be impaired. This was tested in a series of experiments utilizing Brefeldin A, an inhibitor of vesicular secretion and recycling. As a probe, anti-boron-cross-linked-rhamnogalacturonan-II (RG II-B-RG II) polyclonal antibodies, which were previously demonstrated to enable the observation of endocytic recycling of wall polysaccharides (Baluška et al., 2002), were used. In a normal situation, these polysaccharides can be used for the formation of the cell plate during cytokinesis (Dhonukshe et al., 2006), while in BFA-treated cells they are trapped and accumulated within so-called BFA compartments.

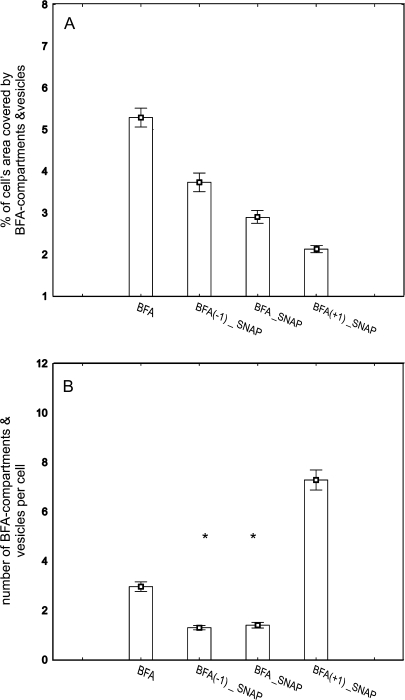

Maize root apices were treated with BFA and SNAP, and experimental variants differed by the relative timing of their application. The most pronounced reactions to treatments were found in cortex cells of the transition zone (Fig. 6). Two parameters, namely cell area covered with BFA compartments, and the number of BFA compartments per cell were analysed for statistically significant differences with one-way analysis of variance-on-ranks according to Kruskal–Wallis, followed by pairwise comparisons with the Mann–Whitney U-test. BFA alone induced the formation of big BFA compartments, usually 2 per cell. Slight labelling of newly formed cell plates was also observed (Fig. 6B). Relatively large BFA compartments were seen in root samples subjected to BFA+SNAP treatment as well as in treatments where BFA was applied 1 h before addition of SNAP (Fig. 6C and D, respectively). Interestingly, in the latter case, the labelling of cell plates was basically not discernible. On the other hand, when BFA was added 1 h after SNAP application, relatively high numbers of much smaller vesicular structures were observed, and a strong labelling of the newly formed cell plates was clearly visible (Fig. 6E, F). Statistical image analysis indicated (P ≤0.01) that the percentage of cell area covered by BFA compartments decreased after the addition of the NO donor, and the level of this decrease is dependent on the relative timing of BFA and SNAP application (Fig. 7A). The largest change was observed in roots treated with SNAP 1 h before the addition of BFA. The presence of NO also affected the number per cell of vesicular structures formed. The effect was dependent on the relative timing of the application of the two compounds. As with the percentage of cell area covered by vesicular structures, in the case of their number the application of SNAP 1 h before the addition of BFA produced the strongest effects, visible as a large number of relatively small compartments (Figs 6E, F, 7B). In summary, the presence of NO modulated the organization of actin cytoskeleton in such a way that some actin-dependent processes, like endocytic vesicle formation and the generation of BFA-induced membraneous compartments, progressed in different ways. In addition, observations of the newly formed cell plates indicated that actin-dependent directional transport of vesicles and the release of wall polysaccharides might also be affected.

Fig. 6.

The presence of NO affects membrane trafficking and recycling of cell wall polysaccharides in the transition zone of maize root apices. Vesicle trafficking was analysed through the application of Brefeldin A, while turnover of wall material was detected with polyclonal antibodies specific for boron-rhamnogalacturonan II complexes. Addition of the NO donor was considered as time point zero. All the images are for SNAP (A) and BFA-treated samples collected after 2 h of treatment. Roots were treated with either 100 μM BFA alone (B) or both BFA and 250 μM SNAP added at the same time (C), with BFA added 1 h before SNAP (D) or BFA added 1 h after SNAP (E, F). Newly formed cell plates are indicated by arrows while BFA compartments by arrowheads (F). Bars=40 μm.

Fig. 7.

The presence of NO affects endocytosis, and endocytic vesicle formation and trafficking in cortex cells in the transition zone of maize root apices. The treatment of root apices was identical to that described in Fig. 5. Roots were subjected to BFA+SNAP treatments differing in the relative timing of the application of the compounds: BFA was applied 1 h before SNAP (BFA(−1)_SNAP), simultaneously with SNAP (BFA_SNAP) or 1 h after SNAP (BFA(+1)_SNAP). Following treatments, roots were sampled 2 h after the application of SNAP, processed for immunochemistry, and the images collected were analysed statistically with the Kruskal–Wallis test and the Mann–Whitney U-test for the number and total size of BFA compartments formed. Roots treated with BFA alone were considered as a control in the Mann–Whitney U-test. Experimental variants that do not show the statistically significant difference according to the Kruskal–Wallis test are indicated by asterisks. (A) Total size of BFA compartments expressed as a percentage of the cell area. (B) The number of BFA compartments per cell. Each bar represents the mean of the measurement series, error bars represent the SE.

Discussion

Our data reveal for the first time that the presence of NO affects the organization of the actin cytoskeleton and endocytosis in plants. They support the notion that dynamic F-actin acts as a downstream effector of NO signalling affecting on endocytosis and vesicle recycling.

Before we embarked on our study, there were only very few hints in the plant literature, based, for example on proteomic data (Lindermayr et al., 2005), that the actin cytoskeleton could be the target of NO signalling or NO-driven protein modifications. Surprisingly, information on the role of NO in vesicle trafficking was even more limited (and for animal models) with some indications that modification of dynamins (Wang et al., 2006a; Kang-Decker et al., 2007) and annexins (Kuncewicz et al., 2003; Lindermayr et al., 2005) might be important. Previous observations also suggested that the tip growth of both pollen tubes and root hairs is actin-dependent (Baluška et al., 2000) and regulated by NO (Prado et al., 2004; Lombardo et al., 2006).

In the present study, the focus was on root apices for several reasons. Firstly, it is quite well established that both root formation and root growth are dependent on NO (Stöhr and Ullrich, 2002). Secondly, abundant data have been accumulated on root cell development in connection to the cytoskeleton and vesicle trafficking (Baluška et al., 2001b). Thirdly, plants function in ‘an open system’ with respect to NO (Yamasaki, 2005). Thus, plant roots have to cope with probably the most diverse array of NO origins, including the apoplast (Bethke et al., 2004), and adjust their own enzymatic and chemical sources of NO (Gupta et al., 2005) to enable proper NO signalling events. This is also shown in this paper. Comparative analysis of actin reorganization evoked by various NO sources, particularly SNAP and NaNO2 indicates that these two NO sources affect the functioning of protein targets in a different way (Table 1; compare, for example, Figs 1B with 4G). On the other hand, relatively weak effects evoked by the application of L-NMMA (Table 1; Fig. 5H) might also suggest that the multiplicity of NO origins provides much required redundancy and stability of NO signalling required for normal root functioning.

The experimental increase of NO levels in cells of maize roots has dramatic but reversible impacts on the actin cytoskeleton assembly and organization. This NO-induced F-actin reorganization shows cell type-, cell development-, and subcellular domain-specificities. The most prominent changes were observed in endodermal cells of the transition zone where axial transcellular cables shifted into oblique positions and F-actin was depleted from the non-growing end-poles (cross-walls) that have been shown to secrete auxin via endosomal vesicle trafficking (Baluška et al., 2005; Schlicht et al., 2006; Mancuso et al., 2007). By contrast, no changes to labelling of F-actin were observed under the longitudinal side-walls, in root cap cells, and in meristematic cells. There are several potential explanations for such cell-type specificity of NO action, two of which seem to be the most plausible. To function as a universal signal, NO has to be transported in the plant either as a signal itself or as a precursor/transporting molecule (Capone et al., 2004; Valderrama et al., 2007). In axial organs, the endodermis might function as a cellular mediator providing a connection between the vascular system and the cortex. Importantly, in this respect, NO has also been implicated in xylem formation (Gabaldón et al., 2005). Such a role of the endodermis might be partly related to the control of nitrate/nitrite uptake by roots and the use of these nitrogen sources for enzymatic NO generation. This, in turn, would create ‘NO hot-spots’ (Neill et al., 2008b) of compartmentalized protein modification (Iwakiri et al., 2006) which can be sensed either by actin itself or by actin-associated proteins. It has already been suggested for yeast (Farah and Amberg, 2007) and animal cells (Aslan et al., 2003) that the actin cytoskeleton could function as a sensor of oxidative or nitrosative stress.

Another possible role of endodermal cells is related to the biochemistry of the source–sink relation of sucrose transport. Carbon skeletons need to be transported to the growing root. It has recently been shown that at least some transported sucrose is taken up by sink cells via endocytosis (Etxeberria et al., 2005). Thus, modulation of actin organization in the endodermis by NO might constitute a mechanism for the regulation of radial nutrient trafficking in roots. It should be remembered, however, that the actin cytoskeleton controls endocytosis and exocytosis, as well as vesicle trafficking. Based on data from studies on animal cells, it is known that NO effectively regulates several proteins critical for the assembly and dynamicity of both tubulin and actin-based cytoskeletons, as well as the vesicle trafficking machinery through post-translational protein modification (Matsushita et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2006a; Kang-Decker et al., 2007). NO might therefore directly affect actin or some actin-binding proteins. Alternatively, NO might primarily affect molecules of the vesicle trafficking apparatus and alterations to the actin cytoskeleton would therefore be only secondary effects. Unfortunately, our data do not allow us to make any final conclusions in this respect. The most realistic scenario is that both vesicle trafficking and actin cytoskeleton molecules are modified by NO in root cells.

For proper functioning, the actin cytoskeleton needs to be anchored somehow in the surrounding walls (Baluška et al., 2003). Our previous observations indicate that this anchorage is sensitive to mechanical disturbance and is differentiated depending on the wall domains surrounding individual protoplasts (Wojtaszek et al., 2007). Here, it is suggested that the endodermis might also function as a sensor of the mechanical environment which acts through NO signalling mechanisms. Several possibilities exist. It is known for animal cells that the polymerization state of the cytoskeleton can regulate the activity of the NO-generating enzymes (Witteck et al., 2003) or that NO can regulate cellular activities through cytoskeleton disruption (Ingram et al., 2000; Banan et al., 2001; Krepinsky et al., 2003). It has also been demonstrated that, in Arabidopsis, mechanical stress elicits NO formation (Garces et al., 2001). It thus seems reasonable to suggest that the endodermis, also due to its specialized wall domains, might function as one of the mechanical integrators of growing roots.

It seems that quite interesting divergence of NO functions could be observed in plants. NO is deeply involved in the initiation, formation, and development of root systems (Stöhr and Ullrich, 2002) and, in that respect, it is engaged in intensive cross-talks with auxin signalling pathways (Pagnussat et al., 2003, 2004; Lanteri et al., 2006). On the other hand, it looks like NO signalling is not essential for shoot formation and growth, although it is important for the shoot apex during its transition into sexual plant organs (He et al., 2004). Increased NO production is induced by environmental stimuli, but NO is also produced constitutively. It thus may integrate both external and internal cues into the floral decision. The crucial question is, what is the signal transduction pathway via which NO controls such fundamental events as root formation and growth, as well as the onset of flowering.

Previous studies revealed that during adventitious root formation NO acts downstream of auxin signalling (Pagnussat et al., 2003, 2004; Lanteri et al., 2006). Moreover, NO is also downstream of nitrate-mediated effects on root formation and growth (Gouvea et al., 1997; Zhao et al., 2007) and Rhizobium nodule formation (Pii et al., 2007). As initiation of lateral root primordia, which is mediated by nitrate supply, is linked to auxin transport from the shoot to the root (Guo et al., 2003), and also exogenous auxin induces NO formation in root cells (Kolbert et al., 2008), NO emerges as an integrator of several signalling cascades interlinking exogenous and endogenous cues that converge on auxin signalling to control diverse aspects of root biology. However, in the roots NO itself could act in different ways, either as a signalling or a modifying molecule.

Our study allowed us to discover that the actin cytoskeleton acts as a downstream effector of NO signal transduction in root cells. This finding may have important consequences for situations such as actin-dependent vesicle trafficking during papilla formation in plant cells under pathogen attack, in which NO signalling alters cell polarity or have impacts on cell growth and morphogenesis. On the other hand, changes in the vesicle trafficking and the formation of BFA-compartments, demonstrated in this paper, suggest that there should be more downstream effectors of NO action, acting either in parallel or in series with actin or actin-related proteins. It is thus worth noting that such a putative link has been revealed recently, implicating NO in the control of phospholipid signalling, both during adventitious root formation (DiStéfano et al., 2008; Lanteri et al., 2008) and in plant defence responses (Laxalt et al., 2007). NO was shown to evoke the accumulation of phosphatidic acid (PA) via activation of either phospholipase D or the phospholipase C and diacylglycerol kinase pathways. Interestingly, in that respect, phospholipase Dζ2 has been shown to regulate vesicle trafficking (Li and Xue, 2007) and polar auxin transport (Mancuso et al., 2007), while PA was indicated as a putative regulator of actin binding protein in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2006). As annexin, another PA-binding protein, has been identified through proteomic studies of animal (Kuncewicz et al., 2003) and plant (Lindermayr et al., 2005) systems as a potential target for S-nitrosylation, these data suggest the existence of a tightly regulated intertwined signalling network between auxin, nitric oxide, phospholipids, and the actin cytoskeleton controlling various aspects of the functioning of root cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Ministry of Science and Higher Education grants PBZ-KBN-110/P04/2004 and Research Network ‘Mobilitas.pl’ to PW, and an Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellowship to PW. Part of the research was done thanks to a DAAD Research Scholarship to AK. We express our gratitude to Chris Staiger (Purdue University, USA) and Toru Matoh (Kyoto University, Japan) for providing us with antibodies against maize pollen actin, and RGII-B complexes, respectively. We are grateful to Marek Kasprowicz (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland) for the help with statistical analysis. We thank the members of our laboratories, particularly Andrej Hlavacka and Markus Schlicht, for helping hand and valuable discussions. FB acknowledges support from the Grant Agency APW, Bratislava, Slovakia (the contract no. APVV-0432-06).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 8-Br-cGMP

8-bromoguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- BFA

Brefeldin A

- cPTIO

2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5,-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxyl-3-oxide

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- L-NMMA

NG-methyl-L-arginine

- ODQ

1-H-(1,2,4)-oxadiazolo-[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one

- RGII

rhamnogalacturonan II

- RT

room temperature

- SAP

S-acetyl-DL-penicillamine

- SIN-1

morpholine sydnonimine

- SNAP

S-nitroso-N-acetyl-DL-penicillamine

- WMC

cell wall–plasma membrane–cytoskeleton

References

- Arasimowicz M, Floryszak-Wieczorek J. Nitric oxide as a bioactive signalling molecule in plant stress responses. Plant Science. 2007;172:876–887. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan M, Ryan TM, Townes TM, Coward L, Kirk MC, Barnes S, Alexander CB, Rosenfeld SS, Freeman BA. Nitric oxide-dependent generation of reactive species in sickle cell disease. Actin tyrosine nitration induces defective cytoskeletal polymerization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:4194–4204. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Busti E, Dolfini S, Gavazzi G, Volkmann D. Liliputian mutant of maize lacks cell elongation and shows defects in organization of actin cytoskeleton. Developmental Biology. 2001a;236:478–491. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Hlavacka A, Šamaj J, Palme K, Robinson DG, Matoh T, McCurdy DW, Menzel D, Volkmann D. F-actin-dependent endocytosis of cell wall pectins in meristematic root cells. Insights from Brefeldin A-induced compartments. Plant Physiology. 2002;130:422–431. doi: 10.1104/pp.007526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Parker JS, Barlow PW. Specific patterns of cortical and endoplasmic microtubules associated with cell growth. Rearrangements of F-actin arrays in growing cells of intact maize root apex tissues: a major developmental switch occurs in the postmitotic transition region. European Journal of Cell Biology. 1992;72:113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Salaj J, Mathur J, Braun M, Jasper F, Šamaj J, Chua N-H, Barlow PW, Volkmann D. Root hair formation: F-actin-dependent tip growth is initiated by local assembly of profilin-supported F-actin meshworks accumulated within expansin-enriched bulges. Developmental Biology. 2000;227:618–632. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Šamaj J, Wojtaszek P, Volkmann D, Menzel D. Cytoskeleton-plasma membrane-cell wall continuum in plants. Emerging links revisited. Plant Physiology. 2003;133:482–491. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Volkmann D, Barlow PW. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. Vol. 20. 2001b. A polarity crossroad in the transition growth zone of maize root apices: cytoskeletal and developmental implications; pp. 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Baluška F, Volkmann D, Menzel D. Plant synapses: actin-based adhesion domains for cell-to-cell communication. Trends in Plant Science. 2005;10:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banan A, Fields JZ, Zhang Y, Keshavarzian A. iNOS upregulation mediates oxidant-induced disruption of F-actin and barrier of intestinal monolayers. American Journal of Physiology. 2001;280:G1234–G1246. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.6.G1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethke PC, Badger MR, Jones RL. Apoplastic synthesis of nitric oxide by plant tissues. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:332–341. doi: 10.1105/tpc.017822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone R, Tiwari BS, Levine A. Rapid transmission of oxidative and nitrosative stress signals from roots to shoots in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2004;42:425–428. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Aragunde N, Graziano M, Chevalier C, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide modulates the expression of cell cycle regulatory genes during lateral root formation in tomato. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:581–588. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Baluška F, Schlicht M, Hlavacka A, Šamaj J, Friml J, Gadella TWJ. Endocytosis of cell surface material mediates cell plate formation during plant cytokinesis. Developmental Cell. 2006;10:137–150. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStéfano A, García-Mata C, Lamattina L, Laxalt AM. Nitric oxide-induced phosphatidic acid accumulation: a role for phospholipases C and D in stomatal closure. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2008;31:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria E, Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Pozueta-Romero J. Sucrose-inducible endocytosis as a mechanism for nutrient uptake in heterotrophic plant cells. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2005;46:474–481. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah ME, Amberg DC. Conserved actin cysteine residues are oxidative stress sensors that can regulate cell death in yeast. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2007;18:1359–1365. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-08-0718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floryszak-Wieczorek J, Milczarek G, Arasimowicz M, Ciszewski A. Do nitric oxide donors mimic endogenous NO-related response in plants? Planta. 2006;224:1363–1372. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabaldón C, Gómez Ros LV, Pedreño MA, Ros Barceló A. Nitric oxide production by the differentiating xylem of Zinnia elegans. New Phytologist. 2005;165:121–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garces H, Durzan D, Pedroso MC. Mechanical stress elicits nitric oxide formation and DNA fragmentation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annals of Botany. 2001;87:567–574. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvea CMCP, Souza JF, Magalhaes CAN, Martins IS. NO releasing substances that induce growth elongation in maize root segments. Plant Growth Regulation. 1997;21:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- Guo F-Q, Okamoto M, Crawford NM. Identification of a plant nitric oxide synthase gene involved in hormonal signaling. Science. 2003;302:100–103. doi: 10.1126/science.1086770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta KJ, Stoimenova M, Kaiser WM. In higher plants, only root mitochondria, but not leaf mitochondria reduce nitrite to NO, in vitro and in situ. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2005;56:2601–2609. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Tang RH, Hao Y, Stevens RD, et al. Nitric oxide represses the Arabidopsis floral transition. Science. 2004;305:1968–1971. doi: 10.1126/science.1098837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess DT, Matsumoto A, Kim SO, Marshall HE, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation: purview and parameters. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6:150–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JK, Yun B-W, Kang J-G, Raja MU, Kwon E, Sorhagen K, Chu C, Wang Y, Loake GJ. Nitric oxide function and signaling in plant disease resistance. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:147–154. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Neill SJ, Tang Z, Cai W. Nitric oxide mediates gravitropic bending in soybean roots. Plant Physiology. 2005;137:663–670. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.054494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Gao L, Blanchoin L, Staiger CJ. Heterodimeric capping protein from Arabidopsis is regulated by phosphatidic acid. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17:1946–1958. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram AJ, James L, Cai L, Thai K, Ly H, Scholey JW. NO inhibits stretch-activated MAPK activity by cytoskeletal disruption. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:40301–40306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakiri Y, Satoh A, Chatterjee S, Toomre DK, Chalouni CM, Fulton D, Groszmann RJ, Shah VH, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthase generates nitric oxide locally to regulate compartmentalized protein S-nitrosylation and protein trafficking. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:19777–19782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605907103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang-Decker N, Cao S, Chatterjee S, Yao J, Egan LJ, Semela D, Mukhopadhyay D, Shah V. Nitric oxide promotes endothelial cell survival signaling through S-nitrosylation and activation of dynamin-2. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:492–501. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke XC, Terashima M, Nariai Y, Nakashima Y, Nabika T, Tanigawa Y. Nitric oxide regulates actin reorganization through cGMP and Ca2+/calmodulin in RAW 264.7 cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2001;1539:101–113. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbert Zs, Bartha B, Erdei L. Exogenous auxin-induced NO synthesis is nitrate reductase-associated in Arabidopsis thaliana root primordia. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2008;165:967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kone BC. S-nitrosylation: targets, controls and outcomes. Current Genomics. 2006;7:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Krepinsky JC, Ingram AJ, Tang D, Wu D, Liu L, Scholey JW. Nitric oxide inhibits stretch-induced MAPK activation in mesengial cells through RhoA inactivation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2003;14:2790–2800. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000094085.04161.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuncewicz T, Sheta EA, Goldknopf IL, Kone BC. Proteomic analysis of S-nitrosylated proteins in mesangial cells. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2003;2:156–163. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300003-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamattina L, Garcia-Mata C, Graziano M, Pagnussat G. Nitric oxide: the versatility of an extensive signal molecule. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2003;54:109–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri ML, Laxalt AM, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide triggers phosphatidic acid accumulation via phospholipase D during auxin-induced adventitious root formation in cucumber. Plant Physiology. 2008;147:188–198. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.111815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri ML, Pagnussat GC, Lamattina L. Calcium and calcium-dependent protein kinases are involved in nitric oxide- and auxin-induced adventitious root formation in cucumber. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:1341–1351. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxalt AM, Raho N, ten Have A, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide is critical for inducing phosphatidic acid accumulation in xylanase-elicited tomato cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:21160–21168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Xue H-W. Arabidopsis PLDζ2 regulates vesicle trafficking and is required for auxin response. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:281–295. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindermayr C, Saalbach G, Durner J. Proteomic identification of S-nitrosylated proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2005;137:921–930. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MC, Graziano M, Polacco JC, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide functions as a positive regulator of root hair development. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2006;1:28–33. doi: 10.4161/psb.1.1.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso S, Marras AM, Mugnai S, Schlicht M, Žársky V, Li G, Song L, Xue H-W, Baluška F. Phospholipase Dζ2 drives vesicular secretion of auxin for its polar cell-cell transport in the transition zone of the root apex. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2007;2:240–244. doi: 10.4161/psb.2.4.4566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoh T, Takasaki M, Takabe K, Kobayashi M. Immunocytochemistry of rhamnogalactouronan II in cell walls of higher plants. Plant and Cell Physiology. 1998;39:483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K, Morrell CN, Cambien B, et al. Nitric oxide regulates exocytosis by S-nitrosylation of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor. Cell. 2003;115:139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00803-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro HP. Signal transduction by protein tyrosine nitration: competition or cooperation with tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent signaling events? Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2002;33:765–773. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia I, de Pinto MC, Delledonne M, Soave C, De Gara L. Comparative effects of various nitric oxide donors on ferritin regulation, programmed cell death, and cell redox state in plant cells. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2004;161:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill S, Barros R, Bright J, Desikan R, Hancock J, Harrison J, Morris P, Ribeiro D, Wilson I. Nitric oxide, stomatal closure, and abiotic stress. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008a;59:165–176. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill S, Bright J, Desikan R, Hancock J, Harrison J, Wilson I. Nitric oxide evolution and perception. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008b;59:25–35. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Desikan R, Hancock JT. Nitric oxide signalling in plants. New Phytologist. 2003;159:11–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnussat GC, Lanteri ML, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide and cyclic GMP are messengers in the indole acetic acid-induced adventitious rooting process. Plant Physiology. 2003;132:1241–1248. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnussat GC, Lanteri ML, Lombardo MC, Lamattina L. Nitric oxide mediates the indole acetic acid induction activation of a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade involved in adventitious root development. Plant Physiology. 2004;135:279–286. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.038554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pii Y, Crimi M, Cremonese G, Spena A, Pandolfini T. Auxin and nitric oxide control indeterminate nodule formation. BMC Plant Biology. 2007;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado AM, Porterfield DM, Feijó JA. Nitric oxide is involved in growth regulation and re-orientation of pollen tubes. Development. 2004;131:2707–2714. doi: 10.1242/dev.01153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Puertas MC, Campostrini N, Matté A, Righetti PG, Perazzolli M, Zolla L, Roepstorff P, Delledonne M. Proteomic analysis of S-nitrosylated proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana undergoing hypersensitive response. Proteomics. 2008;8:1459–1469. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmi ML, Morris KE, Roux SJ, Porterfield DM. Nitric oxide and cGMP signaling in calcium-dependent development of cell polarity in Ceratopteris richardii. Plant Physiology. 2007;144:94–104. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.096131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa T, Zaki MH, Okamoto T, et al. Protein S-guanylation by the biological signal 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. Nature Chemical Biology. 2007;3:727–735. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicht M, Strnad M, Scanlon MJ, Mancuso S, Hochholdinger F, Palme K, Volkmann D, Menzel D, Baluška F. Auxin immunolocalization implicates vesicular neurotransmitter-like mode of polar auxin transport in root apices. Plant Signaling and Behavior. 2006;1:122–133. doi: 10.4161/psb.1.3.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Lamas S, Fang FC. Nitrosylation: the prototypic redox-based signaling mechanizm. Cell. 2001;106:675–683. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamler JS, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J. Biochemistry of nitric oxide and its redox-activated forms. Science. 1992;258:1898–1902. doi: 10.1126/science.1281928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöhr C, Ullrich WR. Generation and possible roles of NO in plant roots and their apoplastic space. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:2293–2303. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erf110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroissnigg H, Trančikova A, Descovich L, Fuhrmann J, Kutschera W, Kostan J, Meixner A, Nothias F, Propst F. S-nitrosylation of microtubule-associated protein 1B mediates nitric-oxide-induced axon retraction. Nature Cell Biology. 2007;9:1035–1045. doi: 10.1038/ncb1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi G, Cappelletti G, Negri A, Pagliato L, Maggioni MG, Maci R, Ronchi S. Characterization of nitroproteome in neuron-like PC12 cells differentiated with nerve growth factor: Identification of two nitration sites in α-tubulin. Proteomics. 2005;5:2422–2432. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valderrama R, Corpas FJ, Carreras A, Fernández-Ocaña A, Chaki M, Luque L, Gómez-Rodríguez MV, Colmenero-Varea P, del Rio LA, Barroso JB. Nitrosative stress in plants. FEBS Letters. 2007;581:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Moniri NH, Ozawa K, Stamler JS, Daaka Y. Nitric oxide regulates endocytosis by S-nitrosylation of dynamin. Proceedings of the National Acadademy of Sciences, USA. 2006a;103:1295–1300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yun B-W, Kwon EJ, Hong JK, Yoon J, Loake GJ. S-nitrosylation: an emerging redox-based post-translational modification in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006b;57:1777–1784. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendehenne D, Durner J, Klessig DF. Nitric oxide: a new player in plant signalling and defence responses. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2004;7:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendehenne D, Pugin A, Klessig DF, Durner J. Nitric oxide: comparative synthesis and signalling in animal and plant cells. Trends in Plant Science. 2001;6:177–183. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)01893-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witteck A, Yao Y, Fechir M, Förstermann U, Kleinert H. Rho protein-mediated changes in the structure of the actin cytoskeleton regulate human inducible NO synthase gene expression. Experimental Cell Research. 2003;287:106–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek P. Nitric oxide in plants. To NO or not to NO. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek P, Anielska-Mazur A, Gabryś H, Baluška F, Volkmann D. Rapid relocation of myosin VIII between cell periphery and plastid surfaces are root-specific and provide the evidence for actomyosin involvement in osmosensing. Functional Plant Biology. 2005;32:721–736. doi: 10.1071/FP05004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtaszek P, Baluška F, Kasprowicz A, Luczak M, Volkmann D. Domain-specific mechanosensory transmission of osmotic and enzymatic cell wall disturbances to the actin cytoskeleton. Protoplasma. 2007;230:217–230. doi: 10.1007/s00709-006-0235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki H. The NO world for plants: achieving balance in an open system. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2005;28:78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D-Y, Tian Q-Y, Li L-H, Zhang W-H. Nitric oxide is involved in nitrate-induced inhibition of root elongation in Zea mays. Annals of Botany. 2007;100:497–503. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]