Abstract

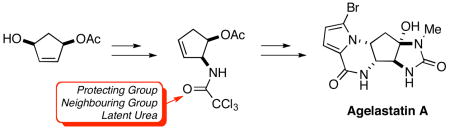

A stereoselective synthesis of agelastatin A, a potent cytotoxin and inhibitor of osteopontin (OPN)–mediated neoplastic transformations, has been accomplished in 14 steps (12 operations) with an approximate overall yield of 8%. Notable features of this route include the direct manner in which the pyrroloketopiperazine A-ring of the target is generated and the efficient employment of a trichloroacetamide, introduced through Overman rearrangement, as a protecting group, pendant nucleophile and latent urea.

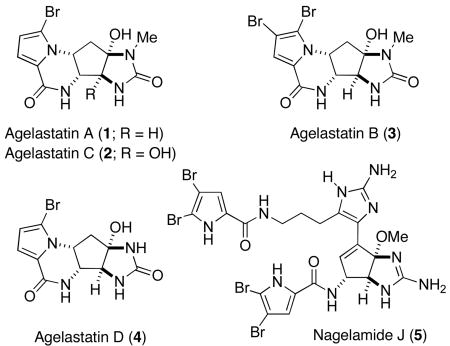

The agelastatins represent a small yet architecturally interesting subclass of the oroidin family of bromopyrrole marine alkaloids,1,2 that are also notable for their potent biological activity. Agelastatin A (1) and B (3) were isolated by Pietra and co-workers in 1993, from the axinellid sponge Agelas dendromorpha collected in the Coral Sea off New Caledonia.3 While there was initial uncertainty as to the stereochemistry of the former compound, this issue was resolved through a combination of NMR studies, molecular modeling and conformational analysis.4 In addition to confirmation of this assignment through total synthesis (vide infra), Pettit has isolated 1 from a Mexican Agela sp. and confirmed its structure using X-ray crystallographic analysis.5 Other members of this family include agelastatin C (2) and D (4), minor congeners isolated from the Australian sponge Cymbastela sp. by Molinski and co-workers.6 Although biogenetically distinct from the agelastatins, being an apparent dimer of an oroidin-like precursor,7 the Okinawan marine sponge metabolite nagelamide J (5) shares the trans-cis-1,2,3-triaminocyclopentanol motif characteristic of this family.8

Much of the attention garnered by the agelastatins, stems from the diverse range of biological activities displayed by compound 1, which include selective inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β,9 a potential target for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease10 and bipolar disorder;11 toxicity towards arthropods;6 and an ability to potently inhibit the growth of a number of human tumor cell lines.3–5,12 The potential clinical importance of 1 as an antineoplastic agent has recently been underscored by El-Tanani and Hale,13 who have demonstrated that agelastatin A is also a powerful antimetastatic agent, which operates through two distinct mechanisms: as an inhibitor of osteopontin-mediated malignant transformations14 and by arrest of the cell cycle.

The biological activity, unique structure and limited availability of the agelastatins has provoked sustained interest in their preparation.15 Weinreb was first to develop a route to racemic agelastatin A (1) and B (2), in which hetero-Diels-Alder and Sharpless/Kresze ene reactions were employed to establish the densely functionalized C-ring.16 Feldman, in an elegant demonstration of the utility of alkynyliodonium salts, subsequently completed the first enantioselective synthesis of both 1 and 2.17 Hale has likewise reported enantioselective routes to 1 from the Hough-Richardson aziridine.18 Employing sulfinimine-based methodology and ring-closing metathesis to establish the C-ring, Davis and Deng have prepared (−)-agelastatin A (1),19 while Trost and Dong have utilized the sequential Pd-mediated allylic N-alkylation of pyrroles and O-methyl hydroxamates to access its enantiomer.20 Ichikawa has employed the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangements of allyl cyanates to establish the vicinal diamine moiety present in the carbocyclic ring.21 Most recently, Yoshimitsu has utilized an aziridine ring-opening strategy to establish the trans-1,2-diamido functionality of 1.22 Herein we report the development of an efficient synthetic route to (±)-agelastatin (1) in which a trichloracetamide group, introduced via Overman rearrangement, plays a central role in that it subsequently mediates cyclofunctionalization, acts as a protecting group and serves as a latent urea for the preparation of the imidazolidinone, D-ring of the natural product.

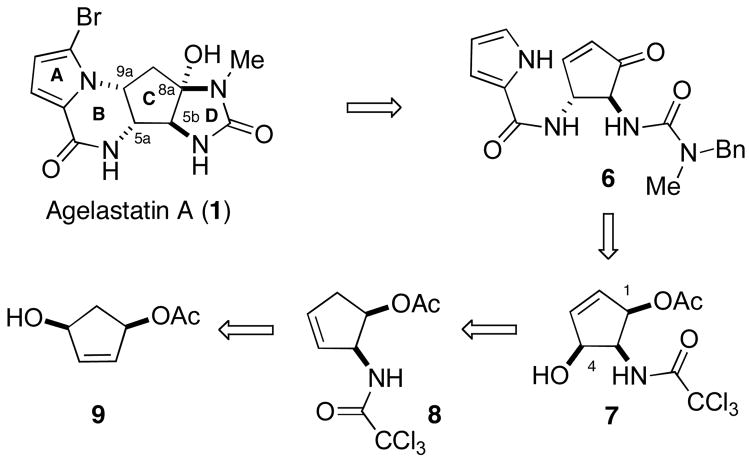

From a retrosynthetic perspective, we envisioned that agelastatin A (1) could be accessed from cyclopentenone 6, through 1,4-addition of the pyrrole unit, a biomimetic23 approach succesfully adopted by a number of other groups (Scheme 1).16–19,21 Formation of the key trans-1,2-diamido functionality present in the C-ring of the target could then be accomplished via displacement of the C-4 hydroxy group of 7 with a suitable nitrogen nucleophile. Through electrophile-promoted cyclofunctionalization24 and eliminative ring-opening, 7 could be accessed from N-allylic trichloroacetamide 8. Finally, this compound could be readily prepared from known allylic alcohol 925 by [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of the corresponding trichloroacetimidate.26 Although the use of the Overman rearrangement in this manner offered an attractive method with which to both establish the C-5b stereocenter and provide a handle for subsequent manipulation of the cyclopentane C-ring, the challenge of removing a trichloroacetyl group under forcing conditions27 was a serious potential drawback. In this regard, Isobe28 and others29 have reported that, upon heating in the presence of alkali metal carbonates, trichloroacetamides undergo detrichloromethylation to generate isocyanates, which can be intercepted with alkylamines to form ureas. In the case of substrate 7, implementation of this one-pot process would not only offer a mild method of deprotection, but simultaneously serve to generate the N-methylurea group required for formation of the D-ring of agelastatin A (1).

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis of Agelastatin A.

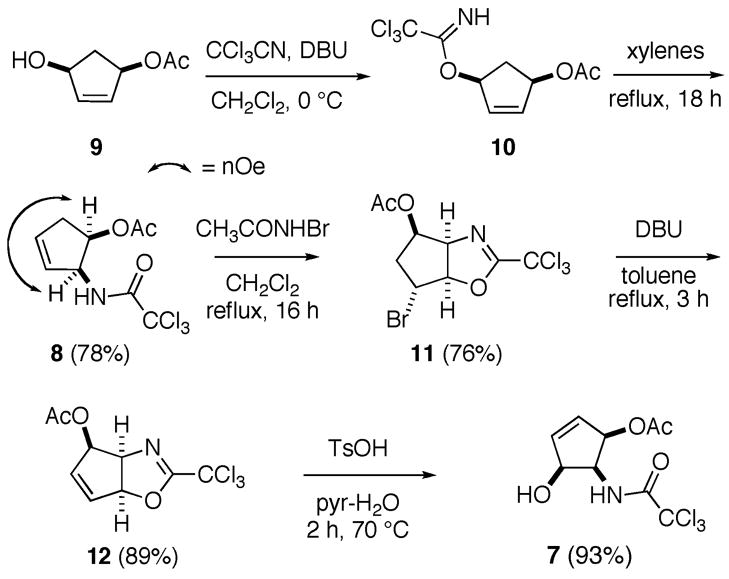

Our route to 1 commenced from cis-3-acetoxy-5-hydroxycyclopent-1-ene (9), which was readily prepared from cyclopentadiene, via peracetic acid epoxidation and subsequent Pd(0)-catalyzed syn-1,4-addition of acetic acid.25 Treatment of 9 with trichloroacetonitrile in the presence of DBU30 cleanly provided imidate 10, which upon heating in xylenes for 18 h, was then tranformed to trichloroacetamide 11 in 78% yield, over two steps (Scheme 2). As anticipated, given the high stereoselectivity associated with this type of [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement,26 product 8 was found to be a single diastereomer by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Further evidence for the relative cis stereochemistry of this product was obtained from the NOESY spectrum of 8, which revealed the correlation shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Trisubstituted Cyclopentene 7.

Despite N-allylic trichloacetamides having previously been reported to undergo 5-exo-trig cyclofunctionalization with both iodinating and brominating reagents,31 treatment of 8 with a range of conventional activators, including NBS, I2, and Br2, failed to mediate cyclization. In these cases, only products arising from alkene addition were isolated, suggesting that the electron-deficient amide group was insufficiently nucleophilic to participate in halonium ion ring-opening. Interestingly, exposure of this substrate to N-bromoacetamide (NBA)32 in refluxing CH2Cl2 did provide 10 in good yield.33 Dehydrobromination of 11, in the presence of DBU in refluxing toluene, then generated allylic acetate 12. Hydrolysis of this dihydrooxazole, with p-toluenesulfonic acid in aqueuous pyridine,34 proceeded smoothly to regenerate the trichloroacetamide group and provide all cis-substituted cyclopentene 7.

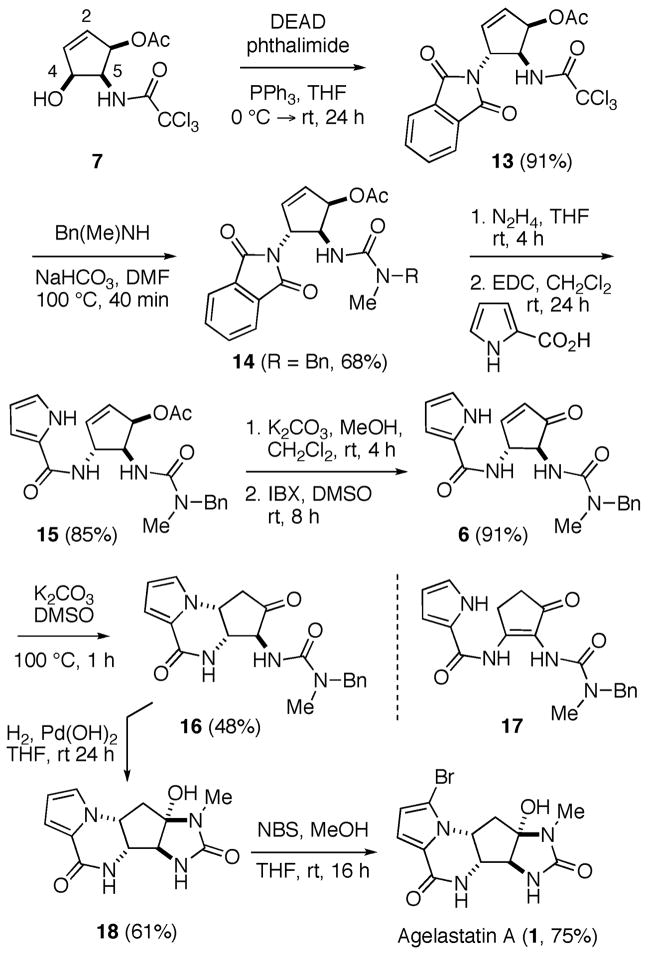

While attempts to now install the trans-1,2-diamido subunit of 1, through activation of the C-4 hydroxyl. group of 7 and inversion with azide, were twarted by competitive SN2′ displacement at the C-2 position,35 treatment of 7 wih phthalimide, under Mitsunobu conditions, provided cyclopentene 13 as a single diastereomer in high yield (Scheme 3). In this case, it appears that the greater steric bulk of the imide anion, in comparison to azide, is necessary for discriminaton of the two potential reaction sites within the alkoxyphosphonium ion derived from 7.

Scheme 3.

Total Synthesis of Agelastatin A.

Proceeding to now unmask the urea functionality latent within compound 13, a solution of this substrate in DMF was heated at 100 °C in the presence of N-methylbenzylamine and NaHCO336 to provide compound 14 (R = Bn) in good yield. Although it had not been our original intention to incorporate an N-benzyl protecting group at this stage, the corresponding N-methylurea 14 (R = H) proved to be too polar to be convieniently carried forward in the synthetic sequence.

Hydrazinolysis of the phthalimide group in 14 (R = Bn) now proceeded smoothly to provide the corresponding primary amine, which, because of its instability, was immediately coupled with 2-pyrrole carboxylic acid to provide 15. Methanolysis of the acetate ester, followed by oxidation of the resulting allylic alcohol with o-iodoxybenzoic acid,37 then generated cyclopentenone 6 in high overall yield. Exposure of this substrate to a variety of Lewis or Brønsted acidic and basic conditions now failed to effect conversion to 16 and resulted in either decomposition of the starting material or formation of tetrasubstituted enone 17. With regards to the latter outcome, Hale has observed the same type of rearrangement during his second generation route to 1 and ascribed the ease of this process to the formation of an aromatic, cyclopentadienyl anion intermediate.18b As part of a study of pyranone ring contraction, Caddick and co-workers have noted that trans-4,5-dihydroxycyclopent-2-enones undergo a similar rearrangement, whose rate is highly dependant on both the nature of the reaction solvent and the base employed.38 Through optimization of these two parameters, we found that tricycle 16 could be successfully generated by heating a solution of 6 in DMSO at 100 °C in the presence of K2CO3. Although of moderate yield, this transformation is notable for the direct manner in which it yields the pyrroloketopiperazine A-ring of the target: neither prior bromination of the pyrrole ring (so as to lower its pKa) or the incorporation of an amide N-protecting group being required under these conditions.

Hydrogenolysis of the N-benzyl group of 16, using Pearlman’s catalyst, now proceeded smoothly to yield debromoagelastatin (18). Annulation of the N,N′-disubstituted urea generated upon debenzylation with the adjoining ketone occurs spontaneously under the reaction conditions. Treatment of 18 with NBS in a mixture of MeOH and THF, as reported by Feldman,17 regioselectively provided (±)-agelastatin A (1), whose spectral data (1H- and 13C-NMR) were in complete agreement with those previously reported by Hale and co-workers.18

In summary, the total synthesis of (±)-agelastatin A (1) has been accomplished from a readily available starting material in 14 steps (12 operations) with an overall yield of ~8%. Modification of this synthetic route so as to encompass the antibiotic nagelamide J (5) is curently underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM-67176) and the University of Illinois at Chicago for financial support of this work.

References

- 1.Faulkner DJ. Nat Prod Rep. 2002;19:1. doi: 10.1039/b009029h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For recent reviews of synthetic efforts towards pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids, see: Hoffmann H, Lindel T. Synthesis. 2003:1753.Weinreb SM. Nat Prod Rep. 2007;24:931. doi: 10.1039/b700206h.Arndt HD, Riedrich M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:4785. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801793.

- 3.D’Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Debitus C, Ribes O, Pusset J, Leroy S, Pietra F. Chem Commun. 1993;1305 [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) D’Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Chiasera G, Pietra F. Helv Chim Acta. 1994;77:1895. [Google Scholar]; (b) D’Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Ripamonti M, Debitus C, Waikedre J, Pietra F. Helv Chim Acta. 1996;79:727. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettit GR, Ducki S, Herald DL, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Chapuis JC. Oncol Res. 2005;15:11. doi: 10.3727/096504005775082075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong TW, Jímenez DR, Molinski TF. J Nat Prod. 1998;61:158–161. doi: 10.1021/np9703813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Mourabit A, Potier P. Eur J Org Chem. 2001;237 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araki A, Tsuda M, Kubota T, Mikami Y, Fromont J, Kobayashi J. Org Lett. 2007;9:2369. doi: 10.1021/ol0707867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meijer L, Thunnissen AM, White AW, Garnier M, Nikolic M, Tsai LH, Walter J, Cleverley KE, Salinas PC, Wu YZ, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Kim SH, Pettit GR. Chem Biol. 2000;7:51. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang HC, O’Brien WT, Klein PS. Drug Discov Ther Strateg. 2006;3:613. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozikowski AP, Gaisina IN, Yuan H, Petukhov PA, Blond SY, Fedolak A, Caldarone B, McGonigle P. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8328. doi: 10.1021/ja068969w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale KJ, Domostoj MM, El-Tanni M, Campbell FC, Mason CK. Total Synthesis And Mechanism Of Action Studies On The Antitumor Alkaloid (−)-Agelastatin A. In: Harmata M, editor. Strategies and Tactics in Organic Synthesis. Vol. 6. Elsevier Academic Press; London: 2005. p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mason CK, McFarlane S, Johnston PG, Crowe P, Erwin PJ, Domostoj MM, Campbell FC, Manaviazar S, Hale KJ, El-Tanani M. Mol Can Thera. 2008;7:548. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber GF. Osteopontin is an extracellular structural glycoprotein implicated in playing a fundamental role in mediating tumor metastasis. Can Lett. 2008;270:181. [Google Scholar]

- 15.For a review of these efforts, see reference 2(b).

- 16.Stien D, Anderson GT, Chase CE, Koh Y, Weinreb SM. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9574. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Feldman KS, Saunders JC. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9060. doi: 10.1021/ja027121e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Feldman KS, Saunders JC, Wrobleski ML. J Org Chem. 2002;67:7096. doi: 10.1021/jo026287v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Domostoj MM, Irving E, Scheinmann F, Hale KJ. Org Lett. 2004;6:2615. doi: 10.1021/ol0490476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hale KJ, Domostoj MM, Tocher DA, Irving E, Scheinmann F. Org Lett. 2003;5:2927. doi: 10.1021/ol035036l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis FA, Deng J. Org Lett. 2005;7:621. doi: 10.1021/ol047634l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trost BM, Dong G. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6054. doi: 10.1021/ja061105q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichikawa Y, Yamaoka T, Nakano K, Kotsuki H. Org Lett. 2007;9:2989. doi: 10.1021/ol0709735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimitsu T, Ino T, Tanaka T. Org Lett. 2008;10:5457. doi: 10.1021/ol802225g. For a related approach, see: Baron E, O’Brien P, Towers TD. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:723.

- 23.Al-Mourabit A, Potier P. Eur J Org Chem. 2001;237 [Google Scholar]

- 24.For reviews, see: Knapp S. Chem Soc Rev. 1999;28:61.Robin S, Rousseau G. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:13681.Cardillo G, Orena M. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:3321.

- 25.(a) Deardorff DR, Shambayati S, Myles DC, Heerding D. J Org Chem. 1988;53:3614. [Google Scholar]; (b) Deardorff DR, Myles DC. Org Synth Coll. 1993;VIII:13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overman LE, Carpenter NE. The Allylic Trihaloacetimidate Rearrangement. In: Overman LE, editor. Organic Reactions. Vol. 66. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 2005. pp. 1–107. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conventional methods of trichloroacetamide cleavage, include: Goody RS, Walker RT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;8:289. (NaOH)Weygand F, Frauendorfer E. Chem Ber. 1970;103:2437. doi: 10.1002/cber.19701030816. (NaBH3)Nishikawa T, Urabe D, Isobe M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:4782. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460293. (DIBAL-H)Singh OV, Han H. Org Lett. 2004;6:3067. doi: 10.1021/ol048961w. (Na-Hg)

- 28.(a) Nishikawa T, Ohyabu N, Yamamoto N, Isobe M. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:4325. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nishikawa T, Urabe D, Tomita M, Tsujimoto T, Iwabuchi T, Isobe M. Org Lett. 2006;8:3263. doi: 10.1021/ol061123c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Atanasova I, Petrov Y, Mollov N. Synthesis. 1987;734 [Google Scholar]; (b) Braverman S, Cherkinsky M, Kedrova L, Reiselman A. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:3235. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ovaa H, Lastdrager B, Codee JDC, van der Marel GA, Overkleeft HS, van Boom JH. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 1. 2002;2370 [Google Scholar]

- 31.(a) Cardillo G, Orena M, Sandri S. Chem Commun. 1983:1489. [Google Scholar]; (b) Commerçon A, Ponsinet G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:3871. [Google Scholar]; (c) Galeazzi R, Martelli G, Orena M, Rinaldi S. Synthesis. 2004;2560 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeung YY, Gao X, Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9644. doi: 10.1021/ja063675w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The success of NBA in mediating the cyclization of 8 may stem from the increased basicity (relative to succinimidyl or halide ions) of the acetamide anion generated upon brominium ion formation, which, through deprotonation, would serve to increase the nucleophilicity of the trichloroacetamide group. The use of NBA also minimizes the halide ion concentration and thus formation of the dihalide addition product: Corey EJ, Loh TP, AchyuthaRao S, Daley DC, Sarshar S. J Org Chem. 1993;58:5600.

- 34.Asai M, Nishikawa T, Ohyabu N, Yamamoto N, Isobe M. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:4543. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shull BK, Sakai T, Nichols JB, Koreeda M. J Org Chem. 1997;62:8294. doi: 10.1021/jo9615155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.In our case, it was found that use of NaHCO3 generated product 14 in significantly better yields than either Cs2CO3 or K2CO3, as previously reported: Urabe D, Sugino K, Nishikawa T, Isobe M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:9405.

- 37.More JD, Finney NS. Org Lett. 2002;4:3001. doi: 10.1021/ol026427n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caddick S, Khan S, Frost LM, Smith NJ, Cheung S, Pairaudeau G. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:8953. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Experimental procedures and characterization data for all new compounds.