Abstract

Genetically identical cells in a uniform external environment can exhibit different phenotypes, which are often masked by conventional measurements that average over cell populations. Although most studies on this topic have used microorganisms, differentiated mammalian cells have rarely been explored. Here, we report that only approximately 40% of clonal human embryonic kidney 293 cells respond with an intracellular Ca2+ increase when ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channels in the endoplasmic reticulum are maximally activated by caffeine. On the other hand, the expression levels of ryanodine receptor showed a unimodal distribution. We showed that the difference in the caffeine sensitivity depends on a critical balance between Ca2+ release and Ca2+ uptake activities, which is amplified by the regenerative nature of the Ca2+ release mechanism. Furthermore, individual cells switched between the caffeine-sensitive and caffeine-insensitive states with an average transition time of approximately 65 h, suggestive of temporal fluctuation in endogenous protein expression levels associated with caffeine response. These results suggest the significance of regenerative mechanisms that amplify protein expression noise and induce cell-to-cell phenotypic variation in mammalian cells.

Keywords: Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release, cell-to-cell phenotypic variability, mathematical modelling, positive feedback

Introduction

Biochemical processes in cells inevitably fluctuate owing in part to the stochastic nature of gene expression systems, which typically involve small numbers of molecules such as DNA, mRNA and proteins (Kaern et al, 2005; Kaufmann and van Oudenaarden, 2007; Pedraza and Paulsson, 2008). In addition to such ‘intrinsic noise', the internal states of cells and the structure of the signalling pathway also contribute to the fluctuation in the concentration of molecules, collectively termed ‘extrinsic noise' (Hooshangi et al, 2005; Pedraza and van Oudenaarden, 2005; Rosenfeld et al, 2005; Shahrezaei et al, 2008). In some cases, intracellular noise in individual cells is filtered so that the system as a whole is precisely regulated, as is observed in the segmentation of a Drosophila melanogaster embryo (Houchmandzadeh et al, 2002; Gregor et al, 2007) and in circadian rhythms (Forger and Peskin, 2005; Gonze and Goldbeter, 2006). Yet in other cases, intracellular noise can be exploited to play roles such as in the amplification of signals, the divergence of cell fates and the diversification of phenotypes, as seen in the lysis/lysogeny decision circuit of the bacteriophage lambda (Arkin et al, 1998; Skupin et al, 2008). In support of this idea, several recent reports suggested that individual clonal cells in the same external environment can exhibit qualitatively different phenotypes, which may confer a selective advantage in adapting to changing external environments (Rao et al, 2002; Raser and O'Shea, 2005; Acar et al, 2008). Such phenomena question the implicit assumption behind cell-population-wide experiments that genetically identical cells are phenotypically identical (Levsky and Singer, 2003) and highlight the need for measuring individual cells.

Thus far, most studies of intracellular noise have focused on unicellular organisms such as Escherichia coli or Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Earlier studies explored the origin of intracellular noise using artificial gene circuits (Elowitz et al, 2002; Ozbudak et al, 2002; Blake et al, 2003; Raser and O'Shea, 2004), whereas recent studies showed various phenotypic diversities in naturally arising biological systems (Samadani et al, 2006; Di Talia et al, 2007; Maamar et al, 2007; Nachman et al, 2007; Schultz et al, 2007; Suel et al, 2007). In multicellular organisms, the importance of stochastic processes is widely recognised in several biological systems in development, including haematopoietic lineage differentiation and retinal colour-vision mosaic development (Laslo et al, 2006; Wernet et al, 2006; Chang et al, 2008). However, there are very few studies of differentiated cells of multicellular organisms (Ravasi et al, 2002; Feinerman et al, 2008), and the possibility and significance of such cells exhibiting different phenotypes in identical environments have rarely been discussed (Sigal et al, 2006; Cohen et al, 2008).

The calcium ion (Ca2+) is a ubiquitous intracellular messenger that regulates a diverse array of cellular functions, such as muscle contraction, secretion, fertilisation, immune responses, gene expression and synaptic plasticity (Berridge et al, 2003). The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is the major intracellular Ca2+ store, from which Ca2+ is released via two families of Ca2+ release channels: ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs). RyRs are activated by Ca2+ released by themselves (Endo, 1977)—;a mechanism known as Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR). IP3Rs are also activated by Ca2+ in the presence of IP3 (Iino, 1990; Bezprozvanny et al, 1991; Finch et al, 1991). CICR is a positive feedback mechanism that amplifies microscopic Ca2+ release and helps Ca2+ signals propagate throughout the cell. As Ca2+ response via these channels involves such a positive feedback, individual cells of the same type may show different Ca2+ responses with the amplification of intracellular noise.

Here, we report that human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells can be an excellent model system for studying the phenotypic diversity of clonal cells, owing to their interesting feature that only approximately 40% of them respond to caffeine with Ca2+ release via RyRs, whereas all of them release Ca2+ via IP3Rs in response to a purinergic agonist, ATP. Our present results suggest that Ca2+ responses to caffeine have threshold characteristics, dictated by a critical balance between the Ca2+ release and uptake activities of the Ca2+ store as well as the regenerative mechanism of CICR, which amplifies the small cell-to-cell differences of protein expression. Furthermore, we observed that with time, individual cells switch between the caffeine-sensitive and caffeine-insensitive states in a flip-flop manner. These results suggest that not only fluctuation in protein expression but also its amplification mechanisms contribute to phenotypic diversity in mammalian cells.

Results

Purinergic and caffeine responses in HEK293 cells

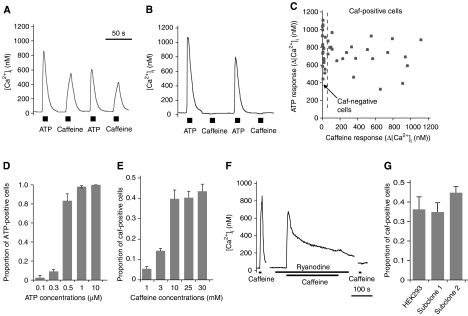

When stimulated with ATP (a purinergic agonist) at the maximal concentration (10 μM), almost all (>99%) of the HEK293 cells responded with a transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Figure 1A–D; Supplementary Figure 1B and Supplementary Movie 1), demonstrating their Ca2+ release activity via IP3Rs. On the other hand, when HEK293 cells were stimulated with 25 mM caffeine (an activator of RyRs), approximately 40% of the cells responded with Ca2+ release, whereas the rest did not (Figure 1A–C; Supplementary Figure 1C and Supplementary Movie 2). We observed no distinct spatial heterogeneity in Ca2+ response within individual cells at the present spatial and temporal resolution (Supplementary Figure 2). The proportion of cells responding to caffeine increased up to a maximum of approximately 40% as caffeine concentration was increased from 1 to 30 mM (Figure 1E). To confirm that the caffeine-induced Ca2+ release is mediated by RyRs, we applied a plant alkaloid, ryanodine, along with caffeine to deplete the intracellular Ca2+ store via RyRs (Iino et al, 1988; Oyamada et al, 1993). A measure of 30 μM ryanodine plus 25 mM caffeine application indeed abolished the caffeine response (Figure 1F). To exclude the possibility that the cells are a mixture of multiple clones, we cloned the cells by limiting dilution, which yielded subclones with a similar cell-to-cell heterogeneity (Figure 1G). Thus, it was shown that HEK293 cells contain two types of cell that are genetically identical but phenotypically different: ‘caf-positive' cells (with Ca2+ response via RyRs) and ‘caf-negative' cells (without Ca2+ response via RyRs). We found a similar cell-to-cell variability in smooth muscle cells in the portal vein of guinea pigs (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Ca2+ responses in individual HEK293 cells. Measurement of [Ca2+]i after agonist stimulation. (A, B) Time courses of [Ca2+]i in two different cells ((A) caf-positive and (B) caf-negative cells). (C) Scatter plot of amplitude of ATP response (Δ[Ca2+]i) versus amplitude of caffeine response (Δ[Ca2+]i). Each point corresponds to each cell in the same imaging field (n=49 cells). (D, E) The proportion of cells responding to ATP increased up to a maximum of approximately 100% as ATP concentration was increased from 0.1 to 10 μM; the proportion of cells responding to caffeine increased up to a maximum of approximately 40% as caffeine concentration was increased from 1 to 30 mM. Data are means±s.e.m. (n=4 imaging fields including 230–280 cells). (F) Application of ryanodine plus caffeine abolished the caffeine response. Data are representative of n=370 cells. (G) Maintenance of intercellular heterogeneity in caffeine response. Proportions of caf-positive cells in HEK293 cells and their two subclones. Data are means±s.e.m. (n=6 dishes for each). A total of 379 HEK293 cells, 330 subclone 1 cells and 367 subclone 2 cells were analysed. There were no significant differences in the proportion of caf-positive cells among the three groups (p=0.28, single-factor ANOVA).

Cell-to-cell variation does not depend on cell cycle or cell morphology

We searched for the mechanism that allows clonal cells to exhibit two different phenotypes. We first examined whether the proportion of caf-positive cells depends on the cell cycle. However, cells synchronised at either G0/G1, G1/S or G2/M phase had the same proportion of caf-positive cells (Supplementary Figure 4A). Furthermore, the proportion of caf-positive cells did not differ significantly with the temperature (room temperature versus 37°C) at which caffeine response was measured (Supplementary Figure 4B). We also analysed the dependence of the magnitude of caffeine response on the extent of cell–cell contact. However, no significant correlation was observed (Supplementary Figure 4C). Neither did we observe any significant dependence on cell morphology (size, perimeter and ellipticity) (Supplementary Figure 4D–F).

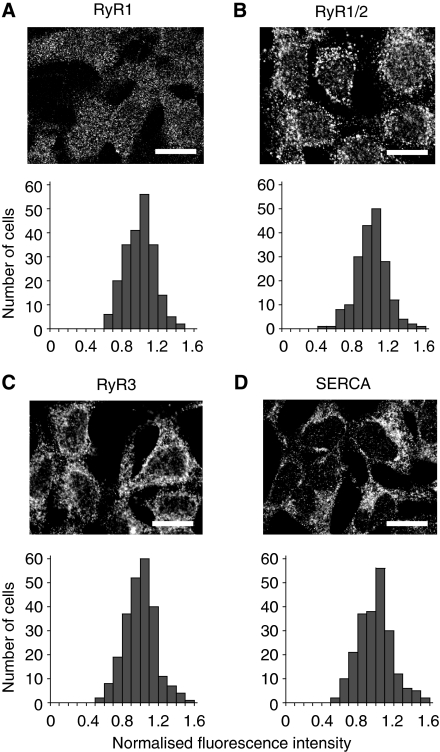

Immunocytochemistry of RyRs and SERCAs

Several recent reports indicated that, even among genetically identical cells in the same environment, the level of gene expression can quantitatively differ depending on intracellular noise (Blake et al, 2003; Raser and O'Shea, 2004). Therefore, we examined the possibility that the protein concentrations associated with Ca2+ response are different, hence leading to distinct phenotypes. We carried out immunocytochemistry using antibodies that recognise different subtypes of RyR. The major subtypes of RyR expressed in HEK293 cells are types 1 and 2 (Querfurth et al, 1998); thus, we used an antibody that recognises RyR1 as well as one that recognises both RyR1 and RyR2. The intensity of cytoplasmic immunofluorescence showed a unimodal distribution with a relatively small standard deviation (Figure 2A and B), contrary to our expectation of a bimodal distribution corresponding to two distinct phenotypes. The detection sensitivity of this immunostaining was verified with a heterologous expression of RyR1. Higher levels of RyR were observed in RyR1-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Figure 5), demonstrating that the antibody reflects the expression level of the receptor. We also used an antibody against RyR3, but again found a unimodal distribution of immunofluorescence intensity among cells (Figure 2C). Thus, the expression level of each RyR subtype seems to be almost uniform among individual cells, although small cell-to-cell variations may be present.

Figure 2.

Immunofluorescence detection of RyRs or SERCAs in HEK293 cells. (A–D) Upper panels: confocal images showing immunofluorescence localisations of RyRs and SERCAs. Scale bars=20 μm. Lower panels: intercellular histograms of fluorescence intensity in cytoplasmic region. (A) RyR1 was detected using an anti-RyR1 antibody. (B) RyR1 and RyR2 were detected. (C) RyR3 was detected. (D) All SERCA subtypes were detected. The total numbers of cells analysed in the bottom panels are as follows: 214 in (A), 190 in (B), 241 in (C) and 220 in (D).

As Ca2+ release from the Ca2+ store is antagonised by Ca2+ uptake by sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), the difference in SERCA expression level may result in the observed heterogeneous Ca2+ responses. We, therefore, analysed the expression level of SERCA by immunocytochemistry. However, the distribution of the cytoplasmic immunofluorescence intensity was again unimodal, and we were unable to find two populations of cells with different SERCA expression levels (Figure 2D). To further study possible cell-to-cell variability in the Ca2+ sequestration activity, we analysed the falling phase of Ca2+ response after stimulation with 10 μM ATP. The falling phase could be fitted by a single exponential (Supplementary Figure 6, inset), and its time constant showed a unimodal distribution (Supplementary Figure 6), suggesting that the Ca2+ sequestration system has a similar activity among cells.

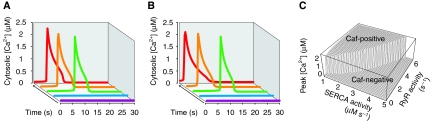

Mathematical model

Provided that there are no qualitative intercellular differences in the concentration of channels and pumps involved in the caffeine response, it must be the process of Ca2+ release that generates two distinct phenotypes in caffeine response. We investigated such a mechanism using a mathematical model of Ca2+ release via RyRs. We modified the conventional model proposed by Keizer and Levine (1996), which incorporates Ca2+ release channels and Ca2+ pumps (Supplementary information and Supplementary Figure 7A). In this model, Ca2+ responses are assumed to be spatially homogeneous, which is supported experimentally in Supplementary Figure 2. Figure 3A shows the response of the model with various numbers of RyRs and a constant number of SERCAs. RyR agonists were applied at t=0. When the number of RyRs in the ER was small, there was no response (magenta and blue traces). As we gradually increased the number of RyRs, a Ca2+ response was suddenly generated (green trace). Further increase in the number of RyRs had little effect on the peak Ca2+ response except for the decrease in lag time (orange and red traces). Although variations in the relative expression levels of RyR subtypes, which have different Ca2+ release activities, would also generate the cell-to-cell variability, we used the simplest formulation in the present model. Conversely, the number of SERCAs was varied while the number of RyRs was kept constant (Figure 3B). When the SERCA number was sufficiently large, no Ca2+ response (magenta and blue traces) was observed upon agonist application. When the SERCA number was gradually decreased, a Ca2+ response was suddenly observed (green trace). With further decrease in the number of SERCAs, there was almost no change in peak height, but the delay time decreased (orange and red traces). Thus, the Ca2+ release via RyRs activated by caffeine has threshold characteristics (Keizer and Levine, 1996; Marchant et al, 1999; Falcke, 2004) and depends on the balance between the numbers or activities of RyRs and SERCAs (Supplementary Figure 7B). We plotted the peak cytosolic Ca2+ concentration against RyR and SERCA activities in a three-dimensional graph (Figure 3C). A boundary is observed between the caf-positive region and the caf-negative region. The cells are caf-positive in the region on the rear left of the boundary line; they are caf-negative in the region on the front right of the boundary line. CICR plays an essential role in this threshold behaviour of Ca2+ response. Indeed, when RyR activity was made Ca2+-insensitive in the above model, no distinct boundary lines between the caf-positive and caf-negative regions were observed (Supplementary Figure 7C).

Figure 3.

Mathematical model of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. (A, B) Response of model when RyR activity or SERCA activity changes. (A) RyR activity was increased in a stepwise manner (0.5 (magenta), 2.5 (blue), 4.5 (green), 6.5 (orange) and 8.5 (red) in s−1) at a constant SERCA activity (3 μM s−1). (B) SERCA activity was decreased in a stepwise manner (5 (magenta), 4 (blue), 3 (green), 2 (orange) and 1 (red) in μM s−1) at a constant RyR activity (4.5 s−1). (C) The balance between the numbers or activities of RyRs and SERCAs determines Ca2+ response via RyRs with threshold characteristics.

To examine the possibility that the threshold behaviour of Ca2+ response is peculiar to the above model, we tested another mathematical model of Ca2+ release via RyRs originally proposed by Roux and Marhl (2004). We confirmed that also in this model, the Ca2+ response via RyRs activated by caffeine has threshold characteristics (Supplementary Figure 7D), and when RyR activity was made Ca2+-insensitive, no distinct boundary lines between the caf-positive and caf-negative regions were observed (Supplementary Figure 7E).

The threshold behaviour of Ca2+ response demonstrated in the above two models suggests that a relatively small difference in RyR or SERCA expression level/activity can induce two distinct phenotypes, caf positivity and caf negativity.

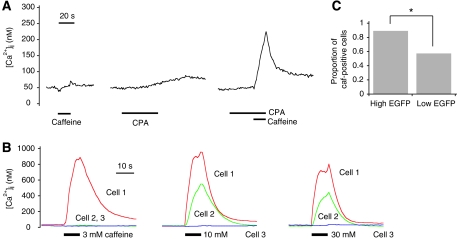

Perturbation experiments

Results of the immunocytochemistry analysis suggest that RyRs are present in caf-negative cells, and the predictions of the mathematical model suggest that caf-negative cells release no Ca2+ upon caffeine application because the balance between Ca2+ release and uptake does not favour Ca2+ release. We tested this notion by artificially shifting the balance between RyR and SERCA activities. First, we partly inhibited SERCAs using its inhibitor. When we applied 10 μM cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) to inhibit SERCA activity, there was a gradual increase in the resting [Ca2+]i (Figure 4A, middle; see also Supplementary Figure 8). When caffeine was further applied, the caf-negative cells responded with a large increase in [Ca2+]i (Figure 4A, right). Milder inhibition of SERCA by 3 μM CPA, which corresponds to the half maximal inhibitory concentration (Makabe et al, 1996), also yielded essentially the same results (Supplementary Figure 9). These results indicate that the leftward shift in Figure 3C (i.e., a decrease in SERCA activity) brought the cells from the caf-negative region to the caf-positive region. We next altered caffeine concentration to change RyR activity (Lee et al, 2002). With increasing caffeine concentration applied to the cells, an increasing number of cells exhibited Ca2+ response in a threshold manner (Figure 4B), indicating that the front-to-rear shift in Figure 3C (i.e., an increase in RyR activity) brought the cell from the caf-negative region to the caf-positive region. To confirm that the caffeine response requires a threshold concentration of caffeine, we carried out delay time analysis (Skupin et al, 2008). Delay time from the application of caffeine to reach 50% peak [Ca2+]i was measured at different caffeine concentrations. Then, inverse delay time was plotted against caffeine concentration, and the linear fit to the plots has a positive intersection with the caffeine axis (Supplementary Figure 10). The result of this analysis is consistent with the presence of threshold caffeine concentration. We also examined caffeine response in HEK293 cells cotransfected with RyR1 and EGFP. Most (approximately 89%) of the cells with a ‘high EGFP expression level' were caf-positive (Figure 4C), again indicating that the front-to-rear shift in Figure 3C brought the cells to the caf-positive region. Thus, results of these perturbation experiments confirmed that caffeine sensitivity is determined by the balance between Ca2+ release and uptake.

Figure 4.

Perturbation experiments for verifying the model. (A) Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) turned caf-negative cells caf-positive. Time courses of [Ca2+]i in the same cell are shown. Data are representative of four experiments including 251 cells. (B) With increasing caffeine concentration, an increasing number of cells showed Ca2+ response in a threshold manner. HEK293 cells loaded with fura-2 were exposed to different caffeine concentrations (3, 10 and 30 mM). Time courses of [Ca2+]i in three different cells are shown. Data are representative of n=221 cells. (C) HEK293 cells overexpressing RyR1 and EGFP were mostly caf-positive. Forty-six cells with a high EGFP expression level and 195 cells with a low EGFP expression level (see Materials and methods for their definitions) were analysed. Asterisk denotes a significant difference between the two proportions (P<0.01; one-proportion Z-test).

Time-lapse Ca2+ imaging of individual HEK293 cells

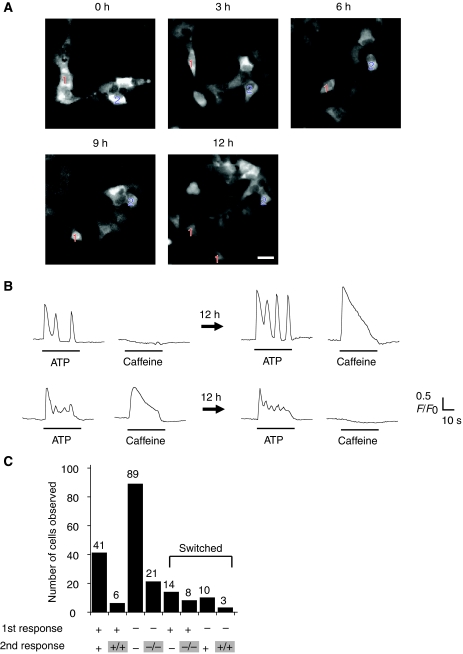

Previous studies using fluorescent reporter proteins have demonstrated that protein concentrations in individual cells fluctuate over time (Rosenfeld et al, 2005; Cai et al, 2006; Sigal et al, 2006; Yu et al, 2006; Cohen et al, 2008). In light of these findings, the results of the cloning experiment (Figure 1F) point to the possibility that individual HEK293 cells switch between the caf-positive and caf-negative states, and that they dwell in the caf-positive state approximately 40% of the time on average. If this is indeed the case, one should be able to observe the conversion between the states by the time-lapse Ca2+ imaging of individual cells. When caffeine response was examined every 10 min, no significant change was observed within 0.5 h (Supplementary Figure 11). We next examined whether a caf-positive (or a caf-negative) cell maintains its phenotype in terms of caffeine response over longer time or upon cell division. For long-term Ca2+ imaging, we used HEK293 cells retrovirally transduced with GCaMP2, a genetically encoded fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (Tallini et al, 2006). The cells were cultured on the stage of a microscope at 37°C in 5% CO2, and simultaneously observed every 10 min to monitor cell movement and division (Figure 5A). Responses of the agonists (ATP and caffeine) were examined at 12-h intervals.

Figure 5.

Time-lapse Ca2+ imaging of individual HEK293 cells. (A) Snapshots of cells were recorded every 10 min to monitor movement and cell division. Note that cell 1 divided between 9 and 12 h. Scale bars=20 μm. (B, C) The results obtained at 12-h intervals were compared. We recorded 550 cells (including 172 caf-positive cells) in 12 sets of experiments, of which we were able to monitor 192 cells for 12 h. (B) Representative plots of phenotypic switching of caffeine response. A measure of 10 μM ATP and 25 mM caffeine were used in all time-lapse experiments. Upper panel: caf-negative to caf-positive. Lower panel: caf-positive to caf-negative. (C) The pattern of the caffeine response in these 192 cells is shown. ‘+' and ‘−' are abbreviations of ‘caf-positive' and ‘caf-negative', respectively; ‘+/+' (or ‘−/−') indicates that the cell divided into two cells within 12 h, and the resulting two cells were both caf-positive (or caf-negative).

We analysed 550 cells from 12 sets of experiments, of which 172 cells (approximately 31%) were caf-positive. The proportion of caf-positive cells was slightly lower than that of fura-2-loaded cells probably due to a narrower dynamic range of GCaMP2 than that of fura-2. Of the 550 cells, 192 cells were successfully monitored for 12 h (Figure 5C). The remaining cells moved out of the imaging field or were not clearly distinguished from adjacent cells. Of the 192 cells analysed, 69 were caf-positive and 123 were caf-negative at the start of the experiment. At the end of the 12-h observation period, 22 caf-positive cells became caf-negative, and 13 caf-negative cells became caf-positive. Thus, 35 of 192 cells (approximately 18%) indeed switched between the caf-positive and caf-negative states. Within the 12-h period, 38 cells underwent cell division. The switching between the states took place with or without cell division (Figure 5C). These results provide direct evidence that an interchange between the caf-positive and caf-negative states takes place within individual cells.

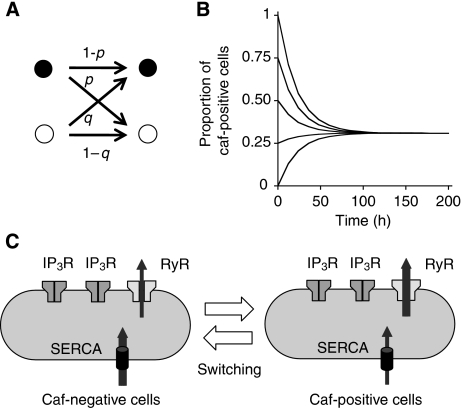

Maintenance of cell-to-cell variability by phenotype switching

We constructed a simple Markov chain model to describe the phenotype switching between the caf-positive and caf-negative states (Figure 6A). Suppose that, in a 12-h observation period or in one ‘time unit', a caf-positive cell turns caf-negative at a probability p, or remains caf-positive at a probability 1−p, whereas a caf-negative cell turns caf-positive at a probability q, or remains caf-negative at a probability 1−q. Here, p and q are constants between 0 and 1. Also, suppose that these probabilities are independent of cell division, and that both caf-positive and caf-negative cells divide equally often. Simple calculations show that after a sufficiently long time, the proportion of caf-positive cells approaches a constant value q/(p+q), regardless of the initial cell composition (Figure 6B). This is a general feature of irreducible and aperiodic Markov chains (Norris, 1997), and well fits the result of the cloning experiment (Figure 1G).

Figure 6.

Switching maintains the intercellular heterogeneity of caffeine response. (A) Description of model. Black and white cells denote caf-positive and caf-negative cells, respectively. (B) After a sufficiently long time, the proportion of caf-positive cells approaches a constant value regardless of the initial proportion (0, 25, 50, 75 or 100%). In (B), p=0.29 and q=0.13 are used. (C) Schematic showing mechanism of phenotype switching.

The above model suggests that the mean transition time from the caf-positive state to the caf-negative state is 1/p time units, and that from the caf-negative state to the caf-positive state is 1/q time units. As the steady-state proportion of caf-positive cells can be expressed by q/(p+q), which is approximately 0.31 in the time-lapse imaging experiments shown in Figure 5, and a cell's mean transition probability in one time unit can be expressed by q/(p+q) × p+p/(p+q) × q, which is approximately 0.18, we obtain p=0.29 and q=0.13. These suggest that each cell cycles between the two states, spending on average approximately 40 h in the caf-positive state and approximately 90 h in the caf-negative state.

Discussion

Mechanisms of cell-to-cell variability and phenotype switching

In the present study, we showed that clonal HEK293 cells exhibit two distinct phenotypes (Ca2+ responses) upon caffeine application and that individual cells switch their phenotypes with an average transition time of approximately 65 h. We proposed using two mathematical models of Ca2+ release via RyRs that the subtle balance between Ca2+ release and uptake activity determines whether a HEK293 cell is caf-positive or caf-negative, which we verified in perturbation experiments. This suggests that the cell-to-cell variability and the temporal switching in caffeine response may be due to relatively small temporal fluctuations in the concentration of certain molecules associated with Ca2+ response, such as RyRs and SERCAs.

A theoretical study by Maurya and Subramaniam (2007) showed that cell-to-cell variability in Ca2+ response such as different peak heights and rise times in RAW 264.7 cells can be modelled by adjusting a set of parameters. In addition to the previous work, we showed the importance of regenerative mechanisms in the phenotypic variations, and succeeded in demonstrating temporal switching of phenotype in individual cells using time-lapse Ca2+ imaging.

Theoretical models (Cai et al, 2006; Friedman et al, 2006; Raj et al, 2006; Chang et al, 2008) have suggested a connection between the temporal dynamics of protein levels in individual cells and the steady-state variations of protein levels across a population of cells. In fact, a study (Sigal et al, 2006) reported that in human lung carcinoma cells, the time required for the ‘mixing' of protein levels τm (in cell generations) and the CV (=standard deviation/mean) of protein levels in a cell population correlate well (R2=0.62) with a best fit of τm=11.3 CV−0.47. As RyR and SERCA protein levels in Figure 2 have CVs of approximately 0.2, the corresponding τms are estimated to be approximately 1.8 cell cycle times (∼1.8 × 30=∼54 h in HEK293 cells (Topham et al, 1998)), which is in good agreement with our Markov chain model in Figure 6. Thus, if the balance between Ca2+ release and uptake changes with time as a consequence of fluctuations in protein concentrations so that a cell crosses the boundary between the caf-positive and caf-negative states (such as that shown in Figure 3C; see also Supplementary Figure 12), the phenotype of the cell will switch. Although we have shown by the perturbation experiments that the changes in RyR or SERCA activity can switch the phenotype of a cell, the notion that small cell-to-cell differences of RyR and SERCA protein levels (Figure 2) are solely responsible for the observed variations in the phenotype remains to be tested experimentally.

We searched for other factors that may cause cell-to-cell variability. However, the proportion of caf-positive cells was independent of the cell cycle (Supplementary Figure 4A), and the amplitude of caffeine response was not correlated with the cell morphology (area, perimeter and ellipticity) or the extent of cell–cell contact (Supplementary Figure 4C–F). It remains to be elucidated whether the fluctuations in protein concentrations are stochastic or are regulated by some other cellular processes.

Physiological implications of cell-to-cell variability

As HEK293 cells are an experimentally transformed cell line (Graham et al, 1977), which may be genetically unstable, it is of interest to examine whether intact tissues or primary cultured cells exhibit similar cell-to-cell variability. We found that smooth muscle cells in the intact portal vein of the guinea pig contain caf-positive as well as caf-negative cells (Supplementary Figure 3).

We used caffeine sensitivity as an indicator of Ca2+ release activity via RyRs. In a physiological setting, caffeine-sensitive cells are expected to be more responsive than caffeine-insensitive cells to RyR-activating stimuli. Ca2+ release via RyRs activates numerous downstream signals. In smooth muscle cells, for example, the activation of RyRs leads to relaxation via local Ca2+ transients termed Ca2+ sparks, which hyperpolarise the membrane potential by activating large-conductance, Ca2+-sensitive K+ (BK) channels (Nelson et al, 1995). Therefore, the coexistence of caffeine-sensitive and caffeine-insensitive smooth muscle cells in the intact portal vein of the guinea pig may serve to regulate the intensity of portal vein contraction.

Novel insight on phenotypic variability

Previous studies of the phenotypic diversity of clonal cells have focused on mechanisms that give rise to a significant cell-to-cell variability (such as bistability) in gene expression (Ozbudak et al, 2004; Acar et al, 2005; Colman-Lerner et al, 2005; Kaufmann et al, 2007; Maamar et al, 2007; Suel et al, 2007), where the presence of positive feedback loops in gene regulatory networks has been suggested to be essential. Here, our study shows a novel principle in which, even when the cell-to-cell difference in gene expression is relatively small, cell signalling other than gene regulatory networks can amplify the difference, thereby providing markedly different phenotypes (Ca2+ responses). Phenotype switching between distinct states, in turn, vividly shows the existence of temporal fluctuations in endogenous molecular expression levels. Given the ubiquity of positive feedback loops in cell signalling systems (Bhalla and Iyengar, 1999; Brandman et al, 2005), it is possible that such amplification may contribute to cell-to-cell phenotypic variability in many cellular functions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HEK293 cells were cultured on collagen-coated dishes in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml). We used cells at passages 15–25. For Ca2+ imaging experiments, the cells were plated onto collagen-coated glass bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) 1 day before imaging.

Ca2+ imaging of HEK293 cells

HEK293 cells on collagen-coated glass bottom dishes were loaded at room temperature (22–25°C) with 5 μM fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in physiological salt solution (PSS) containing 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5.6 mM glucose and 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). Fluorescence images at >420 nm were acquired using an inverted microscope (IX70; Olympus, Japan) equipped with a 40 × (N.A. 0.9) or 20 × (N.A. 0.75) objective, a cooled charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and a polychromatic illumination system (T.I.L.L. Photonics, Planegg, Germany) at a rate of one frame every 1 or 2 s. The excitation wavelengths were 345 and 380 nm. Ca2+ imaging experiments were conducted at room temperature unless otherwise specified.

Time-lapse Ca2+ imaging of individual HEK293 cells

GCaMP2 was stably expressed in almost all the populations of HEK293 cells using a lentiviral vector (Lois et al, 2002) in which the promoter and the green fluorescent protein cDNA were replaced with the human cytomegalovirus promoter and the GCaMP2 cDNA (Tallini et al, 2006; a gift from Dr Nakai), respectively. Lentiviral particles were produced as described previously (Kanemaru et al, 2007). Briefly, the plasmids of the viral vector (15 μg), the vesicular somatitis virus G glycoprotein (VSV-G)-encoding vector (pVSV-G; 4 μg) and pΔ8.9 (8 μg) were cotransfected into 293FT cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After centrifugation (8000 g for 16 h at 4°C), the viral containing medium was applied to HEK293 cells in a glass bottom dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA) and cultured for approximately 3 days. One hour before imaging, the culture medium was replaced with Opti-MEM I without Phenol Red (Invitrogen) mixed with 3% fetal bovine serum. At the start of the experiment, the dish was placed inside a microscope-attached culture system (Olympus, Japan) kept at 37°C in 5% CO2. Before recording the cells' response to ATP or caffeine, the medium was first completely replaced with PSS through the inlet and outlet ducts. Then PSS containing ATP or caffeine was given for 1 min and PSS alone was given for the next 5 min, during which the cells' Ca2+ response was recorded every 2 s with GCaMP2 as the indicator. Fluorescence images at 515–550 nm were acquired. The excitation wavelength was 480 nm. After the recording, PSS was again replaced with the culture medium (Opti-MEM I without Phenol Red with 3% fetal bovine serum), and the cells were cultured for 12 h before the next recording. For 12 h, the cells were imaged every 10 min to monitor cell movement and division. Cells that moved out of or newly moved into the imaging field during the 12-h observation period were excluded from analysis.

Image analysis

Image analysis was carried out using IPLab (BD Biosciences Bioimaging, Rockville, MD). Regions of interest (ROIs) corresponding to individual cells were selected as large as possible, and the average fluorescence intensity F of each ROI minus a background intensity was calculated for each frame. For fura-2 measurement, we used the ratio F345/F380 (the value of F at an excitation wavelength of 345 nm divided by the value of F at an excitation wavelength of 380 nm) as an indicator of [Ca2+]i. For GCaMP2 measurement, the fluorescence intensity (F) was normalised by that (F0) before agonist application, and the normalised fluorescence intensity (F/F0) was used as an indicator of [Ca2+]i. A cell was determined to be ‘caf-positive' when the maximum change in the fluorescence ratio F345/F380 or F/F0 on caffeine application exceeded 10 times the background fluctuation (i.e., the standard deviation of 15 ratios before caffeine application); otherwise, it was determined to be ‘caf-negative'. An in vitro calibration of fura-2 fluorescence ratio to estimate intracellular Ca2+ concentration was performed according to the equation reported by Grynkiewicz et al (1985); its dissociation constant Kd for Ca2+ was estimated to be 239 nM.

Cloning of HEK293 cells by limiting dilution

A suspension of HEK293 cells was diluted with sufficient amount of culture medium and plated into wells of a 96-well plate. Each well was carefully examined using a microscope and only wells that contained exactly one cell were singled out. The cells in the selected wells were cultured for several weeks until they proliferated into sufficient number to be used in subsequent experiments.

Immunocytochemistry

HEK293 cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilised with 0.1% Triton X-100. After blocking with 10% bovine serum albumin in PBS, endogenous RyRs or SERCAs were detected with anti-RyR and anti-SERCA rabbit (or mouse) antibodies, respectively, and Alexa 488-conjugated (or Alexa 546-conjugated) anti-rabbit (or anti-mouse) IgG antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Their subcellular localisations were visualised with a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Fluoview; Olympus, Japan). The antibody against RyR1 is a gift from Dr Oyamada (Showa University). The antibodies against RyR1/2 (34C), RyR3 and SERCA (H-300) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO), Chemicon (Pittsburgh, PA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), respectively.

RyR overexpression

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with both rabbit RyR1-pcDNA3.1 (a gift from Dr Oyamada, Showa University) and EGFP-pcDNA3.1 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). EGFP served as a transfection marker. RyR1-overexpressing cells were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis and Ca2+ imaging. Each cell was classified as showing either ‘high EGFP expression level' or ‘low EGFP expression level' depending on whether its mean EGFP fluorescence was greater than or less than 5% that of the most fluorescent cell in the same imaging field.

Mathematical models of Ca2+ release via RyRs

We used two mathematical models of Ca2+ release via RyRs. The first one is based on ‘the open-cell model' described by Keizer and Levine (1996), with some parameters slightly modified. The second one is based on the model described by Roux and Marhl (2004), with some parameters slightly modified. Details of the model equations and the parameter values we used are described in Supplementary Information. We used Mathematica (Wolfram Research, Champaign, IL) for numerical calculations.

Pharmacological agents

ATP was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Germany. Caffeine, ryanodine, CPA were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Japan. Fura-2 AM and fluo-4 AM were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Cytochalasin D was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Norepinephrine was purchased from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd, Japan.

Supplementary Material

Ca2+ responses of HEK293 cells to 10 μM ATP.

Ca2+ responses of HEK293 cells to 25 mM caffeine.

This file contains: Supplementary Results, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References, Supplementary Tables 1-2, and Supplementary Figures S1-12

An SBML version of the modified Keizer-Levine model

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Junichi Nakai for providing a GCaMP2 construct, and Dr Hideto Oyamada for providing a rabbit RyR1 construct and an anti-RyR1 antibody. We also thank Dr Kazunori Kanemaru, Mr Yusuke Kawashima and Ms Yuri Sato for their technical assistance. This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) and in part by Global COE Program (Integrative Life Science Based on the Study of Biosignaling Mechanisms), MEXT, Japan.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Acar M, Becskei A, van Oudenaarden A (2005) Enhancement of cellular memory by reducing stochastic transitions. Nature 435: 228–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar M, Mettetal JT, van Oudenaarden A (2008) Stochastic switching as a survival strategy in fluctuating environments. Nat Genet 40: 471–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkin A, Ross J, McAdams HH (1998) Stochastic kinetic analysis of developmental pathway bifurcation in phage lambda-infected Escherichia coli cells. Genetics 149: 1633–1648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL (2003) Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 517–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE (1991) Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature 351: 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla US, Iyengar R (1999) Emergent properties of networks of biological signaling pathways. Science 283: 381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake WJ, Kaern M, Cantor CR, Collins JJ (2003) Noise in eukaryotic gene expression. Nature 422: 633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandman O, Ferrell JE Jr, Li R, Meyer T (2005) Interlinked fast and slow positive feedback loops drive reliable cell decisions. Science 310: 496–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Friedman N, Xie XS (2006) Stochastic protein expression in individual cells at the single molecule level. Nature 440: ;358–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HH, Hemberg M, Barahona M, Ingber DE, Huang S (2008) Transcriptome-wide noise controls lineage choice in mammalian progenitor cells. Nature 453: 544–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AA, Geva-Zatorsky N, Eden E, Frenkel-Morgenstern M, Issaeva I, Sigal A, Milo R, Cohen-Saidon C, Liron Y, Kam Z, Cohen L, Danon T, Perzov N, Alon U (2008) Dynamic proteomics of individual cancer cells in response to a drug. Science 322: 1511–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman-Lerner A, Gordon A, Serra E, Chin T, Resnekov O, Endy D, Pesce CG, Brent R (2005) Regulated cell-to-cell variation in a cell-fate decision system. Nature 437: 699–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Talia S, Skotheim JM, Bean JM, Siggia ED, Cross FR (2007) The effects of molecular noise and size control on variability in the budding yeast cell cycle. Nature 448: 947–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS (2002) Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science 297: 1183–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M (1977) Calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Physiol Rev 57: 71–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcke M (2004) Reading the patterns in living cells—the physics of Ca2+ signaling. Adv Phys 53: 255–440 [Google Scholar]

- Feinerman O, Veiga J, Dorfman JR, Germain RN, Altan-Bonnet G (2008) Variability and robustness in T cell activation from regulated heterogeneity in protein levels. Science 321: 1081–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch EA, Turner TJ, Goldin SM (1991) Calcium as a coagonist of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced calcium release. Science 252: 443–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forger DB, Peskin CS (2005) Stochastic simulation of the mammalian circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 321–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman N, Cai L, Xie XS (2006) Linking stochastic dynamics to population distribution: an analytical framework of gene expression. Phys Rev Lett 97: 168302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonze D, Goldbeter A (2006) Circadian rhythms and molecular noise. Chaos 16: 026110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FL, Smiley J, Russell WC, Nairn R (1977) Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol 36: 59–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor T, Tank DW, Wieschaus EF, Bialek W (2007) Probing the limits to positional information. Cell 130: 153–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY (1985) A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooshangi S, Thiberge S, Weiss R (2005) Ultrasensitivity and noise propagation in a synthetic transcriptional cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 3581–3586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houchmandzadeh B, Wieschaus E, Leibler S (2002) Establishment of developmental precision and proportions in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature 415: 798–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M (1990) Biphasic Ca2+ dependence of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release in smooth muscle cells of the guinea pig taenia caeci. J Gen Physiol 95: 1103–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M, Kobayashi T, Endo M (1988) Use of ryanodine for functional removal of the calcium store in smooth muscle cells of the guinea-pig. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 152: 417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaern M, Elston TC, Blake WJ, Collins JJ (2005) Stochasticity in gene expression: from theories to phenotypes. Nat Rev Genet 6: 451–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemaru K, Okubo Y, Hirose K, Iino M (2007) Regulation of neurite growth by spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations in astrocytes. J Neurosci 27: 8957–8966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann BB, van Oudenaarden A (2007) Stochastic gene expression: from single molecules to the proteome. Curr Opin Genet Dev 17: 107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann BB, Yang Q, Mettetal JT, van Oudenaarden A (2007) Heritable stochastic switching revealed by single-cell genealogy. PLoS Biol 5: e239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer J, Levine L (1996) Ryanodine receptor adaptation and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release-dependent Ca2+ oscillations. Biophys J 71: 3477–3487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslo P, Spooner CJ, Warmflash A, Lancki DW, Lee HJ, Sciammas R, Gantner BN, Dinner AR, Singh H (2006) Multilineage transcriptional priming and determination of alternate hematopoietic cell fates. Cell 126: 755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Meissner G, Kim DH (2002) Effects of quercetin on single Ca2+ release channel behavior of skeletal muscle. Biophys J 82: 1266–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levsky JM, Singer RH (2003) Gene expression and the myth of the average cell. Trends Cell Biol 13: 4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D (2002) Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science 295: 868–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maamar H, Raj A, Dubnau D (2007) Noise in gene expression determines cell fate in Bacillus subtilis. Science 317: 526–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makabe M, Werner O, Fink RH (1996) The contribution of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-transport ATPase to caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients of murine skinned skeletal muscle fibres. Pflugers Arch 432: 717–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant J, Callamaras N, Parker I (1999) Initiation of IP3-mediated Ca2+ waves in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J 18: 5285–5299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya MR, Subramaniam S (2007) A kinetic model for calcium dynamics in RAW 264.7 cells: 1. Mechanisms, parameters, and subpopulational variability. Biophys J 93: 709–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachman I, Regev A, Ramanathan S (2007) Dissecting timing variability in yeast meiosis. Cell 131: 544–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ (1995) Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 270: 633–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J (1997) Markov Chains. New York: Cambridge University Press pp 40–47 [Google Scholar]

- Oyamada H, Iino M, Endo M (1993) Effects of ryanodine on the properties of Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skinned skeletal muscle fibres of the frog. J Physiol 470: 335–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Kurtser I, Grossman AD, van Oudenaarden A (2002) Regulation of noise in the expression of a single gene. Nat Genet 31: 69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Lim HN, Shraiman BI, Van Oudenaarden A (2004) Multistability in the lactose utilization network of Escherichia coli. Nature 427: 737–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza JM, Paulsson J (2008) Effects of molecular memory and bursting on fluctuations in gene expression. Science 319: 339–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza JM, van Oudenaarden A (2005) Noise propagation in gene networks. Science 307: 1965–1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth HW, Haughey NJ, Greenway SC, Yacono PW, Golan DE, Geiger JD (1998) Expression of ryanodine receptors in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells. Biochem J 334 (Pt 1): 79–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Peskin CS, Tranchina D, Vargas DY, Tyagi S (2006) Stochastic mRNA synthesis in mammalian cells. PLoS Biol 4: e309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao CV, Wolf DM, Arkin AP (2002) Control, exploitation and tolerance of intracellular noise. Nature 420: 231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raser JM, O'Shea EK (2004) Control of stochasticity in eukaryotic gene expression. Science 304: 1811–1814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raser JM, O'Shea EK (2005) Noise in gene expression: origins, consequences, and control. Science 309: 2010–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravasi T, Wells C, Forest A, Underhill DM, Wainwright BJ, Aderem A, Grimmond S, Hume DA (2002) Generation of diversity in the innate immune system: macrophage heterogeneity arises from gene-autonomous transcriptional probability of individual inducible genes. J Immunol 168: 44–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld N, Young JW, Alon U, Swain PS, Elowitz MB (2005) Gene regulation at the single-cell level. Science 307: 1962–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux E, Marhl M (2004) Role of sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in Ca2+ removal in airway myocytes. Biophys J 86: 2583–2595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samadani A, Mettetal J, van Oudenaarden A (2006) Cellular asymmetry and individuality in directional sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 11549–11554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Ben Jacob E, Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG (2007) Molecular level stochastic model for competence cycles in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 17582–17587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrezaei V, Ollivier JF, Swain PS (2008) Colored extrinsic fluctuations and stochastic gene expression. Mol Syst Biol 4: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal A, Milo R, Cohen A, Geva-Zatorsky N, Klein Y, Liron Y, Rosenfeld N, Danon T, Perzov N, Alon U (2006) Variability and memory of protein levels in human cells. Nature 444: 643–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skupin A, Kettenmann H, Winkler U, Wartenberg M, Sauer H, Tovey SC, Taylor CW, Falcke M (2008) How does intracellular Ca2+ oscillate: by chance or by the clock? Biophys J 94: 2404–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suel GM, Kulkarni RP, Dworkin J, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Elowitz MB (2007) Tunability and noise dependence in differentiation dynamics. Science 315: 1716–1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallini YN, Ohkura M, Choi BR, Ji G, Imoto K, Doran R, Lee J, Plan P, Wilson J, Xin HB, Sanbe A, Gulick J, Mathai J, Robbins J, Salama G, Nakai J, Kotlikoff MI (2006) Imaging cellular signals in the heart in vivo: cardiac expression of the high-signal Ca2+ indicator GCaMP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 4753–4758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topham MK, Bunting M, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, Blackshear PJ, Prescott SM (1998) Protein kinase C regulates the nuclear localization of diacylglycerol kinase-zeta. Nature 394: 697–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernet MF, Mazzoni EO, Celik A, Duncan DM, Duncan I, Desplan C (2006) Stochastic spineless expression creates the retinal mosaic for colour vision. Nature 440: 174–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Xiao J, Ren X, Lao K, Xie XS (2006) Probing gene expression in live cells, one protein molecule at a time. Science 311: 1600–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ca2+ responses of HEK293 cells to 10 μM ATP.

Ca2+ responses of HEK293 cells to 25 mM caffeine.

This file contains: Supplementary Results, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References, Supplementary Tables 1-2, and Supplementary Figures S1-12

An SBML version of the modified Keizer-Levine model