Abstract

The lack of valid and reliable instruments designed to measure the experiences of older persons with advanced dementia and those of their health care proxies has limited palliative care research for this condition. This study evaluated the reliability and validity of 3 End-of-Life in Dementia (EOLD) scales that measure the following outcomes: (1) satisfaction with the terminal care (SWC-EOLD), (2) symptom management (SM-EOLD), and (3) comfort during the last 7 days of life (CAD-EOLD). Data were derived from interviews with the health care proxies (SWC-EOLD) and primary care nurses (SM-EOLD, CAD-EOLD) for 189 nursing home residents with advanced dementia living in 15 Boston-area facilities. The scales demonstrated satisfactory to good reliability: SM-EOLD (α = 0.68), SWC-EOLD (α = 0.83), and CAD-EOLD (α = 0.82). The convergent validity of these scales, as measured against other established instruments assessing similar constructs, was good (correlation coefficients ranged from 0.50 to 0.81). The results of this study demonstrate that the 3 EOLD scales demonstrate “internal consistency” reliability and demonstrate convergent validity, and further establish their utility in palliative care dementia research.

Keywords: dementia, nursing homes, palliative care, end-of-life, health care proxy

Research efforts conducted over the last decade have highlighted the need to improve the quality of care at the end of life.1 Much of this effort focused on either patients dying with cancer or in the acute care setting. However, the experiences of an increasing number of persons dying with advanced dementia and that of their health care proxies (HCPs) have not been well studied. The lack of valid and reliable instruments designed to measure these end-of-life experiences has been one factor limiting advanced dementia and palliative care research.

Earlier work has helped to identify what is most important to patients and their families near the patients’ end of life.2–5 Based on this work, several national organizations, such as the American Geriatrics Society and the Institute of Medicine, have endorsed broad domains defining the quality of the end-of-life experience. 6 Palliative care research requires the ability to measure these domains. However, instrument development has been challenging, particularly in research efforts focusing on advanced dementia where direct patient reporting is often impossible. Consequently, many prior investigations describing outcomes in advanced dementia were hindered by the fact that they lacked reliable and validated measures.2,7–10

To address this issue, 3 End-of-Life in Dementia (EOLD) scales that evaluate the experiences of severely cognitively impaired persons have been developed: (1) satisfaction with care (SWC-EOLD), (2) symptom management (SM-EOLD), and (3) comfort around dying (CAD-EOLD).11 These scales were originally derived using cross-sectional data obtained retrospectively from surveying 156 bereaved family members of decedents with Alzheimer disease. Evaluation of the scales in the original data set revealed very good internal reliability. Reliability testing and validation of the EOLD scales using other data sources have not been replicated.

The purpose of this study is to replicate evidence for the reliability, and to evaluate the validity of the 3 EOLD scales in a second cohort to further establish the utility of these measures in advanced dementia research. To accomplish this objective, data were obtained from an ongoing prospective study of nursing home (NH) residents with advanced dementia and their families: Choices, Attitudes, and Strategies for Care of Advanced Dementia at the End of Life (CASCADE). The CASCADE study incorporated the EOLD scales in its data collection protocol to assess 3 primary outcomes: (1) family satisfaction with the terminal care provided by the NH, (2) managing physical and emotional symptoms, and (3) comfort assessment during the dying process.

METHODS

Study Population

Subjects in the CASCADE study consist of dyads: NH residents with advanced dementia and their HCPs. The residents lived in 15 Boston-area facilities between February 2003 and November 2005. Eligibility criteria for residents included: age >65 years, a Cognitive Performance Score12 of 5 or 6 (range 0 to 6, scores of 5 and 6 identify residents who are comatose or severely impaired in their daily decision-making) on their most recent Minimum Data Set13 assessment, cognitive impairment due to dementia, Global Deterioration Scale7 score of 7, a length of stay ≥ 30 days, and the availability of an HCP who was willing to participate and could communicate in English. Residents were excluded from this study if they resided in a subacute or short-term rehabilitative unit, had cognitive impairment due to a major stroke, traumatic brain injury, tumor, or chronic psychiatric condition, or if they were comatose.

Data Collection

Resident data were collected by chart review and nursing interview at baseline, and at quarterly intervals thereafter for up to 18 months. If the resident died during the follow-up period, a death assessment was completed within 14 days. HCP data were collected by telephone interviews at baseline, and at quarterly intervals thereafter for up to 18 months. HCPs were interviewed 2 and 7 months postdeath if the resident died. Trained research assistants gathered all information from chart reviews, nursing interviews, and HCP interviews.

Descriptive Variables

Demographic information for both residents and HCPs was obtained at baseline and include age, sex, race, the relationship of the HCP to the resident (offspring, spouse, sibling, niece or nephew, sibling, grandson/granddaughter, legal guardian, or other), and education level of the HCP. White was chosen as the ethnic reference group because that category represented greater than 90% of the total. Functional ability was assessed by the Bedford Alzheimer Nursing Scale—Severity Subscale (BANS-S), a 7-item scale ranging from 7 (no impairment) to 28 (most severe impairment). The BANS-S scale includes interaction ability (speech, eye contact), functional deficits (dressing, eating, ambulation), and occurrence of pathologic symptoms (sleep-wake cycle disturbance, muscle rigidity/contractures). The scale’s coefficient α was reported as 0.80.14

EOLD Scales

To assess HCP satisfaction with the care provided to the resident, the SWC-EOLD scale was administered to the HCP at baseline, at every quarterly interview, and at the 2-month postdeath interview. The SWC-EOLD assesses satisfaction with care during the prior 90 days. The SWC-EOLD has 10 items, each measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 4 as follows: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree. The questionnaire items address decision-making, communication with health care professionals, understanding the resident’s condition, and the resident’s medical and nursing care. The total SWC-EOLD score represents a summation of all 10 items (range, 10 to 40), with higher scores indicating more satisfaction. Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient for the SWC-EOLD in the development cohort was 0.90.11

At baseline and each quarterly assessment, resident comfort was assessed by interviewing a nurse with primary care responsibility for the resident using the SM-EOLD. The scale quantifies the frequency a resident experiences the following 9 symptoms and signs during the previous 90 days: pain, shortness of breath, depression, fear, anxiety, agitation, calm, skin breakdown, and resistance to care. Frequency is quantified on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 5 as follows: daily, several days a week, once a week, 2 or 3 days a month, once a month, never. The SM-EOLD score is constructed by summing the value of each item, and ranges from 0 to 45 with higher scores indicating better symptom control. The α reliability coefficient for the SM-EOLD in the development cohort was 0.78.11

If the resident died, the CAD-EOLD Scale was completed within 14 days after death by interviewing a nurse with primary care responsibility for the resident. The CAD-EOLD items assessed the following 14 symptoms and conditions during the last 7 days of life: discomfort, pain, restlessness, shortness of breath, choking, gurgling, difficulty in swallowing, fear, anxiety, crying, moaning, serenity, peace, and calm. These signs were assessed on a scale ranging from 1 to 3 as follows: not at all, somewhat, and a lot. The last 3 items were reverse-coded because they are considered good conditions. The CAD-EOLD score is constructed by summing the value of each item, and the total score ranges from 14 to 42 with higher scores indicating better symptom control. The α reliability coefficient for the CAD-EOLD in the development cohort was 0.85.11

Validity Testing

Other related measures were selected from the CASCADE data set for the purpose of evaluating the convergent validity of the EOLD scales. The SWC-EOLD was compared to the Decision Satisfaction Inventory (DSI).15 The DSI is a valid 15-item questionnaire that measures satisfaction with medical decision-making (converted to a percent with 100% indicating complete satisfaction). The DSI was administered at the follow-up interviews to those HCPs who had made a decision regarding the residents’ care during the interval between assessments.

The Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia (QUALID)16 scale was used as a comparison scale for the SM-EOLD scale at the baseline assessment. The QUALID is a valid and reliable instrument for rating quality of life in late-stage dementia, and was completed by the residents’ nurse in a face-to-face interview. The QUALID is an 11-item scale that focuses on observable physical and emotional signs of distress in the resident. A 5-point scale captures the frequency of each item, and total score ranges from 11 to 55, with lower scores indicating higher quality of life.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated and used to describe the general characteristics of the resident, HCP and EOLD scales. Cronbach coefficient α and lower 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and used to estimate the reliability of the scales.17 It has been suggested that 0.7 and above are acceptable reliability coefficient values,18 though it is understood that acceptable levels may vary by particular discipline and research topic. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients and 95% CIs, estimating the association between an individual scale item and the sum of the remaining items that constitute the scale, were also calculated. These correlations provide an estimate of the contribution of each individual item to the scale. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients and 95% CIs were used to estimate the strength of the association between EOLD scales with comparison scales, which in turn were used to evaluate convergent validity. SAS was used in all analyses,19,20 except that Stata/SE 8.2 for Windows21 was used to produce histograms, and to calculate the lower limit of the 95% CI for the Cronbach coefficient α’s. An α of <0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study Sample Description

At the time of this report, data from 189 resident/HCP dyads recruited into the CASCADE study were available for analysis. Three-month follow-up assessments were completed for 142 of these dyads, and 68 of the residents had died.

The mean age of residents at baseline was 84.8 ± 7.9 (standard deviation, SD) years, 84.1% were female, and 89.5% were white. The residents’ mean BANS-S score was 20.6 ± 2.7 (SD). The average age of the HCP was 59.7 ± 12.0 (SD) years, 61.4% were female and 90.5% were white. The relationship of the HCPs with the residents was predominately offspring (69.3%) or spouses (12.2%), and 94.5% had at least a high school education (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia and Their Health Care Proxies (n = 189)

| Mean (SD) or % | |

|---|---|

| Residents | |

| Age (baseline) | 84.8 (7.9) |

| BANS | 20.6 (2.7) |

| White | 89.5 |

| Female | 84.1 |

| Health care proxies | |

| Age | 59.7 (12.0) |

| Relationship | |

| Offspring | 69.3 |

| Spouse | 12.2 |

| Niece or nephew | 7.9 |

| Sibling | 5.3 |

| Grandson/granddaughter | 1.0 |

| Legal guardian | 1.0 |

| Other | 3.3 |

| White | 90.5 |

| Female | 61.4 |

| Education ≥ high school | 94.5 |

SD indicates standard deviation.

EOLD Scales

Total EOLD scores were only calculated if subjects responded to all items in the individual scales. Therefore, missing data account for discrepancies between the number of subjects with EOLD scores and the total numbers of subjects available for the assessment (ie, 168 HCPs responded to all items in the SWC-EOLD scale at baseline although 189 HCPs were interviewed).

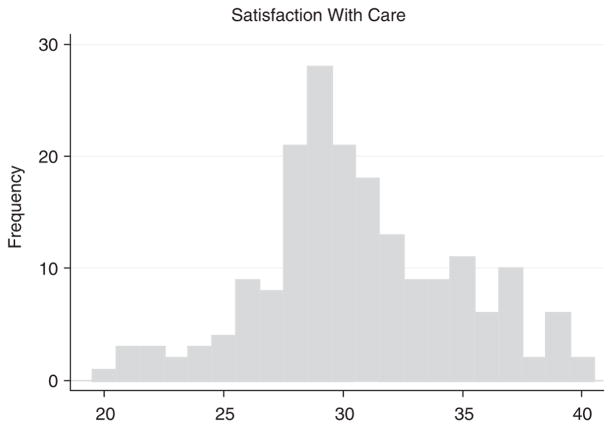

Table 2 presents the items included in the SWC-EOLD scale obtained from 168 HCPs at baseline. Cronbach’s coefficient α for the SWC-EOLD scale was 0.83 (lower CI = 0.79). The Pearson correlation between an individual item and the sum of the remaining items that constitute the scale ranged from 0.34 to 0.60. The mean SWC-EOLD score was 30.9 ± 4.1. Figure 1 presents a histogram of SWC-EOLD from the baseline HCP interviews, demonstrating an approximate normal distribution.

TABLE 2.

Items Included in the SWC-EOLD, and the Pearson and Spearman Correlations Between Each Individual Item, and the Sum of the Remaining Items that Constitute the SWC-EOLD Scale

| Item | Pearson Correlation (95% CI) With SWC-EOLD | Spearman Correlation (95% CI) With SWC-EOLD |

|---|---|---|

| I felt fully involved in all decision making | 0.54 (0.42, 0.64) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.65) |

| I would probably have made different decisions if I had had more information | 0.54 (0.42, 0.63) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.64) |

| All measures were taken to keep my care recipient comfortable | 0.51 (0.38, 0.61) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.65) |

| The health care team was sensitive to my needs and feelings | 0.51 (0.39, 0.61) | 0.49 (0.36, 0.59) |

| I did not really understand my care recipient’s condition | 0.34 (0.20, 0.46) | 0.37 (0.23, 0.49) |

| I always know which doctor or nurse was in charge of my care recipient’s care | 0.45 (0.32, 0.56) | 0.43 (0.29, 0.54) |

| I feel that my care recipient got all necessary nursing assistance | 0.58 (0.47, 0.67) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.67) |

| I feel that all medication issues were clearly explained to me | 0.53 (0.41, 0.63) | 0.52 (0.40, 0.62) |

| My care recipient received all treatments or interventions that he or she could have benefited from | 0.60 (0.50, 0.69) | 0.61 (0.50, 0.69) |

| I feel that my care recipient needed better medical care at the end of his or her life | 0.55 (0.44, 0.65) | 0.56 (0.45, 0.66) |

Cronbach coefficient α for the SWC-EOLD scale was 0.83 (lower limit 95% CI = 0.79) (N = 168).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of SWC-EOLD scores (n = 168).

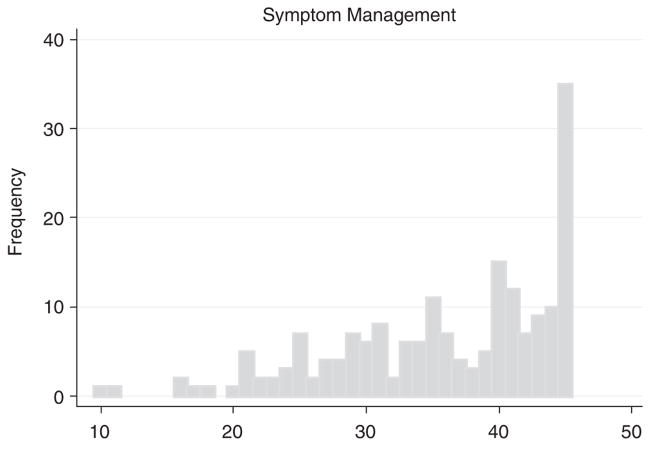

Table 3 presents the items included in the SM-EOLD scale obtained from 176 of the residents’ nurses at baseline. The coefficient α for the SM-EOLD scale was 0.68 (lower CI = 0.62). The Pearson correlation between an individual item and the sum of the remaining items that constitute the scale ranged from 0.01 to 0.69. Skin breakdown and shortness of breath had relatively lower correlations. The mean SM-EOLD score was 36.4 ± 7.8. Figure 2 presents a histogram of SM-EOLD from the baseline nurse interviews, demonstrating a skewed distribution toward higher scores (better symptom management).

TABLE 3.

Items Included in the Symptom Management at End-of-Life With Dementia Scale (SM-EOLD), and the Pearson and Spearman Correlations Between an Individual Item, and the Sum of the Remaining Items that Constitute the SM-EOLD Scale

| Item | Pearson Correlation (95% CI) With SM-EOLD | Spearman Correlation (95% CI) With SM-EOLD |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | 0.27 (0.13, 0.40) | 0.27 (0.12, 0.40) |

| Shortness of breath | 0.12 (− 0.02, 0.27) | 0.16 (0.01, 0.30) |

| Skin breakdown | 0.01 (− 0.13, 0.16) | −0.004 (− 0.15, 0.14) |

| Calm | 0.32 (0.18, 0.45) | 0.42 (0.29, 0.54) |

| Depression | 0.27 (0.13, 0.40) | 0.25 (0.11, 0.39) |

| Fear | 0.44 (0.32, 0.55) | 0.43 (0.30, 0.54) |

| Anxiety | 0.61 (0.51, 0.70) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.66) |

| Agitation | 0.69 (0.61, 0.76) | 0.69 (0.60, 0.76) |

| Resistiveness to care | 0.45 (0.33, 0.56) | 0.44 (0.32, 0.55) |

Cronbach coefficient α for the SM-EOLD scale was 0.68 (lower limit of 95% CI = 0.62) (N = 176).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of SM-EOLD scores (n = 176).

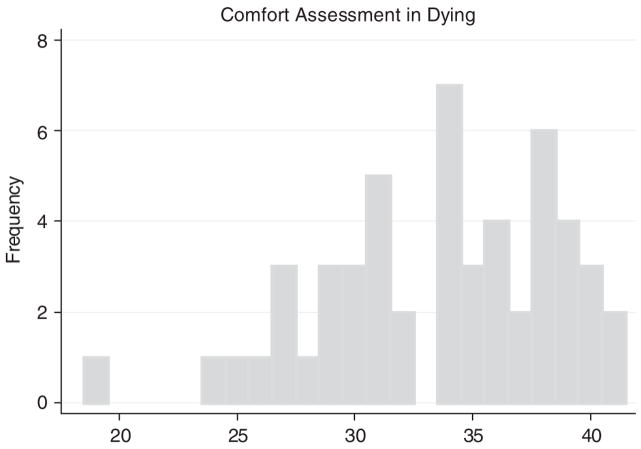

Table 4 presents the items included in the CAD-EOLD scale obtained from the 68 nurse interviews at the death assessments. The coefficient α for the CAD-EOLD scale was 0.82 (lower CI = 0.75). The Pearson correlation between an individual item and the sum of the remaining items that constitute the scale ranged from −0.01 to 0.61. The crying item was strongly skewed (ie, 95% reported no crying) resulting in a slightly negative item correlation with the total score. This correlation was not significant and can be considered zero for all practical purposes. The mean CAD-EOLD score was 33.6 ± 5.0. Figure 3 presents a histogram of CAD-EOLD. The distribution was slightly skewed toward higher scores (greater comfort).

TABLE 4.

Items Included in the CAD-EOLD, and the Pearson and Spearman Correlations Between an Individual Item, and the Sum of the Remaining Items that Constitute the CAD-EOLD Scale

| Item | Pearson Correlation (95% CI) With CAD-EOLD | Spearman Correlation (95% CI) With CAD-EOLD |

|---|---|---|

| Discomfort | 0.61 (0.40, 0.75) | 0.63 (0.43, 0.77) |

| Pain | 0.53 (0.30, 0.70) | 0.55 (0.32, 0.71) |

| Restlessness | 0.48 (0.24, 0.66) | 0.46 (0.21, 0.65) |

| Shortness of breath | 0.50 (0.26, 0.68) | 0.49 (0.25, 0.67) |

| Choking | 0.43 (0.17, 0.63) | 0.34 (0.07, 0.56) |

| Gurgling | 0.34 (0.07, 0.56) | 0.41 (0.15, 0.61) |

| Difficulty swallowing | 0.24 (− 0.03, 0.48) | 0.26 (−0.01, 0.49) |

| Fear | 0.57 (0.35, 0.73) | 0.52 (0.28, 0.69) |

| Anxiety | 0.52 (0.29, 0.70) | 0.51 (0.27, 0.69) |

| Crying | −0.01 (− 0.29, 0.26)* | −0.04 (− .31, 0.23)* |

| Moaning | 0.59 (0.38, 0.74) | 0.59 (0.37, 0.74) |

| Serenity | 0.40 (0.14, 0.60) | 0.40 (0.14, 0.60) |

| Peace | 0.44 (0.18, 0.63) | 0.45 (0.20, 0.64) |

| Calm | 0.56 (0.33, 0.72) | 0.56 (0.33, 0.72) |

95% of residents had reported no crying.

Cronbach coefficient α for the CAD-EOLD scale was 0.82 (lower limit of 95% CI = 0.75) (N = 52).

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of CAD-EOLD scores (n = 52).

Convergent Validity

Table 5 presents the correlations between the EOLD scales and scales measuring similar constructs. Between the baseline and the 3-month follow-up interview, 25 HCPs had participated in decision-making for the resident with dementia, and responded to the DSI. The Pearson correlation coefficient estimating the relationship between the SWC-EOLD scale and the DSI scale collected at the 3-month interview was 0.81 (95% CI = 0.60, 0.91) (P = 0.0001); Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.68, (95% CI = 0.37, 0.84) (P = 0.0002).

TABLE 5.

Convergent Validity

| SWC vs. DSI | SM vs. QUALID | CAD vs. QUALID | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent | HCP | Nurse | Nurse |

| Time | 3 mo | Baseline | Resident death |

| N | 25 | 174 | 50 |

| Pearson correlation (95%CI) (P) | 0.81 (0.60, 0.91) (P = 0.0001) | −0.64 (− 0.72,− 0.54) (P = 0.0001) | −0.50 (− 0.68,− 0.26) (P = 0.0002) |

| Spearman correlation (95% CI) (P) | 0.68 (0.37, 0.84) (P = 0.0002) | −0.63 (− 0.71,− 0.52) (P = 0.0001) | −0.50 (− 0.68,− 0.25) (P = 0.0002) |

Association between 3 End-of-Life in Dementia Scales with other measures obtained in the CASCADE study.

The Pearson correlation coefficient estimating the relationship between the SM-EOLD scale and the QUALID scale at the baseline resident assessment (N = 174) was −0.64 (95% CI = −0.72, −0.54) (P = 0.0001); Spearman correlation coefficient was −0.63, (95% CI = −0.71, −0.52) (P = 0.0001).

The Pearson correlation coefficient estimating the relationship between the CAD-EOLD scale and the QUALID scale at the resident death assessment (N = 50) was −0.50, (95% CI = −0.68, −0.26) (P = 0.0002); Spearman correlation coefficient was −0.50, (95% CI = −0.68, −0.25) (P = 0.0002).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study extend the development of the EOLD scales by demonstrating the “internal consistency” reliability of the measures in a second cohort, and showing for the first time, convergent validity with other instruments measuring similar constructs. These findings further establish the psychometric integrity of the EOLD scales and support their usefulness as outcome measures in advanced dementia research.

There are important similarities and differences between subjects analyzed in the CASCADE study and the original development cohort. The baseline sample sizes were comparable (CASCADE, N = 189 vs. original, N = 154). In both studies, most of the patients with advanced dementia were white; however, the CASCADE patient cohort was older (mean age, 84.8 vs. 81.2 y), and had a greater proportion of females (84% vs. 45%). All CASCADE patients resided in NHs, whereas subjects in the original study lived in either the community or an institution. Nonetheless, the functional disability of the 2 study cohorts was almost identical as measured by the mean BANS-S score (20.7 vs. 20.4). With respect to the dyad relationship, the HCPs in CASCADE were mostly offspring (69%), whereas family caregivers in the original study were predominately spouses (64%), and only 34% were offspring. Family caregivers in the original study were also more often female (75%) compared to the HCPs in CASCADE (61%).

There are also some notable differences between the data collection methods used in the 2 studies. In the original study, all measures were ascertained by a mail-in survey administered to caregivers (ie, family members) up to 1 year after the patient with dementia had died. In contrast, in the CASCADE study, the SWC-EOLD was administered to the HCPs in a telephone interview although the resident was still alive to ascertain satisfaction with care during the prior 90 days. Similarly, the SM-EOLD was obtained from a face-to-face nursing interview while the resident was alive to measure symptoms in the prior 90 days. In both studies the CAD-EOLD was obtained after death. However, in the CASCADE study it was collected from a nursing interview rather than the caregiver.

Despite the differences in subjects and data collection methods, the 3 EOLD scales demonstrated very good reliability in the CASCADE study sample, and these reliability estimates were similar to the estimates reported in the original study. This finding is important as it further establishes the generalizabilty of the psychometric properties of these scales in advanced dementia, particularly in the NH setting where approximately 70% of patients with advanced dementia die.22

As expected, the α coefficients were slightly lower in this validation cohort compared to the original developmental cohort for the SWC-EOLD (0.83 vs. 0.90), SM-EOLD (0.68 vs. 0.78), and the CAD-EOLD (0.82 vs. 0.85). Satisfaction with care, as measured by the average SWC-EOLD scores, was very similar in 2 studies (30.9 vs. 30.5). However, the mean SM-EOLD score in the CASCADE sample was much greater than in the original cohort (36.4 vs. 21.3), indicating more comfort. The mean CAD-EOLD score (33.6 vs. 31.4) was also slightly higher in CASCADE. Moreover, the distributions of the SM-EOLD and CAD-EOLD scales were skewed toward higher scores in CASCADE, whereas these scales approached a normal distribution in the original study. The reason for these differences is not clear. It is possible that persons dying with advanced dementia in the CASCADE study experienced greater comfort compared to those in the original study. Alternatively, it is possible that differences in how these measures were collected in the 2 studies influenced the reporting of symptoms and signs in this population.

This study has several limitations worthy of discussion. The CASCADE study consists of residents who are predominately white, as was true of the original study. It is not clear whether the reliability and validity of the scales generalize to people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds. Second, the analyses presented in this study are cross-sectional, as was true of the original study. The next step in establishing the psychometric properties of these scales, particularly the SWC-EOLD and SM-EOLD, would be to examine the response patterns over time. The repeated, longitudinal measures currently being collected in the on-going CASCADE study will provide an opportunity to conduct these analyses.

Measuring the quality of health care, particularly at the end-of-life, is a difficult, but critical step toward improving care. The findings of this study demonstrated that SWC-EOLD, SM-EOLD, and the CAD-EOLD scales are valid and reliable tools that measure key palliative care outcomes in advanced dementia. In particular, this study extends the usefulness of these scales to research conducted in the NH setting, and while the patients are actually receiving end-of-life care, rather than after they have died.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH-NIA R01 AG024091 and P50 AG05134 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Grant (S.L.M.).

The investigators wish to thank the CASCADE study data collection and management team (Ruth Carroll, Cherie Swift, Sara VanValkenburg, Shirley Morris, Ellen Gornstein, Nina Shikhanov, and Margaret Bryan), Michele Shaffer, PhD for statistical advice, all the sta. at the participant nursing homes, and the residents and families who have generously given their time to this study.

References

- 1.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT) JAMA. 1995;274:1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanson LC, Danis M, Garrett J. What is wrong with end-of-life care? Opinions of bereaved family members. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1339–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenger NS, Rosenfeld K. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:677–685. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-8_part_2-200110161-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynn J. Measuring quality of care at the end of life: a statement of principles. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:526–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, et al. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB. Dying with advanced dementia in the nursing home. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:321–326. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamberg JL, Person CJ, Kiely DK, et al. Decisions to hospitalize nursing home residents dying with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1396–1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayser-Jones J. The experience of dying: an ethnographic nursing home study. Gerontologist. 2002;42(Spec3):11–19. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Blasi ZV. Scales for evaluation of End-of- Life Care in Dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:194–200. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, et al. MDS Cognitive Performance Scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M174–M182. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.4.m174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris JN, Murphy K, Nonemaker S. Long Term Care Resident Instrument User’s Manual Version 2.0. Baltimore, MD: Health Care Financing Administration; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, Kowall NW. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49:M223–M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry MJ, Walker-Corkery E, Chang Y, et al. Measurement of overall and disease-specific health status: does the order of questionnaires make a difference? J Health Serv Res Policy. 1996;1:20–27. doi: 10.1177/135581969600100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiner MF, Martin-Cook K, Svetlik DA, et al. The quality of life in late-stage dementia (QUALID) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2000;1:114–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychmetric Theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS. SAS/STAT User’s Guide, Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.SAS. SAS Language Reference: Dictionary Version 8. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.STATA. STATA/SE. 8.2. Texas: College Station; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, et al. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]