Abstract

Topiramate (TPM) is one of the novel antiepileptic drugs and exhibits a wide range of mechanisms of action. Efficacy of TPM has been demonstrated in partial-onset seizures and primary generalized seizures in adults and children, as both monotherapy and adjunctive therapy. More recently, TPM has been proposed as an add-on treatment for patients with lithium-resistant bipolar disorder, especially those displaying rapid-cycling and mixed states. This paper reviews the multiple mechanisms of action and the tolerability profile of TPM in the light of its therapeutic potential in affective disorders. Studies of TPM in bipolar disorder are evaluated, and the efficacy and tolerability issues as a mood stabilizing agent are discussed.

Keywords: topiramate, antiepileptic drugs, epilepsy, mood stabilizer, bipolar disorder

Introduction

Topiramate (TPM) is a sulfamate derivative of fructose, structurally unrelated to existing anticonvulsants (Perucca 1997; Privitera 1997; Glauser 1999; Reife et al 2000; Shank et al 2000). It was marketed for the add-on treatment of patients with drug-resistance partial epilepsy (Shank et al 1994) and, through the following years, it has shown a broad spectrum of efficacy, which extends to refractory partial and secondary generalized seizures (Faught et al 1996; Privitera et al 1996), primary generalized tonic/clonic seizures (Biton et al 1999) and tonic/atonic seizures associated with the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (Sachdeo et al 1999; Mikaeloff et al 2003). Preliminary data suggest that, in addition to its use in epilepsy, TPM may have therapeutic effects in some neuropsychiatric conditions, such as bipolar and schizoaffective disorders, bulimia, neuropathic pain syndromes, migraine and cluster headache prophylaxis, and essential tremor (Kamin 2002; Spina and Perugi 2004; D’Amico et al 2006). The variety of proposed clinical applications of TPM is consistent with the multiple mechanisms of action. These mechanisms will be shortly reviewed in the present paper, together with the psychotropic effects of TPM therapy in both epileptic and non-epileptic patients.

Mechanisms of action of topiramate

Preclinical studies designed to elucidate the mechanisms of action of TPM have revealed a broad spectrum of pharmacological properties (Shank et al 2000; White 2002).

Blockade of voltage-dependent sodium channels

TPM reduces the frequency of activation of voltage-sensitive sodium channels in a state- or use- dependent manner. In electrophysiological studies of cultured hippocampal neurons, TPM, at micromolar concentrations, has been found to reduce the duration of spontaneous epileptiform bursts of neuronal firing and the frequency of action potentials elicited by a depolarizing of electrical currents (Coulter et al 1993; De Lorenzo et al 2000). TPM produces a voltage-sensitive, use-dependent, and time-dependent suppression of sustained repetitive firing (SRF) in cultured mouse spinal cord and neocortical cells (McLean et al 2000). However, the activity of TPM on sodium channels differs from that of other antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), in which a rapid limitation or complete block of SRF occurs. Based on these findings, it has been concluded that although TPM appears to exert some of its anticonvulsant effects by blocking voltage-sensitive, use-dependent sodium channels, it does so by a mechanism that seems to differ from that of classic sodium channel blocking AEDs such as phenytoin (PHT), carbamazepine (CBZ), and lamotrigine (LTG). As such, it has been suggested that sodium channel blockade may not be the primary mechanism by which TPM exerts its anticonvulsant activity (McLean et al 2000).

Potentiation of γ-aminobutyric acid-mediated transmission

TPM enhances the effects of the inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated neurotransmission through an inter-action with the GABAA receptors, resulting in increased brain GABA level. At 10–100 μM concentrations, TPM has been found to enhance GABA-stimulated chloride influx in cultured cerebellar granule cells, and to increase the frequency of GABA-mediated activation of GABAA receptors in cultures of cerebellar and cortical neurons, exhibiting a concentration-dependent dynamic (Brown et al 1993; White et al 1995; White et al 1997). These effects do not involve an action on the benzodiazepine-binding site on the GABAA receptor and some studies indicate that TPM does not interact with GABA binding sites or benzodiazepine binding sites on GABAA. The anticonvulsant action of TPM may be related to an effect at some unidentified binding sites of GABAA receptors that are not modulated by the benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil (Shank et al 1994; White et al 2000).

Antagonism of non N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamate receptor

TPM is known to inhibit neuronal excitatory pathways through a selective action at the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) and kainate subtypes of glutamate receptors. Some studies have shown that TPM (10–100 μM) blocks kainate-evoked inward currents in cultured hippocampal neurons, possibly by exerting an antagonistic effect at AMPA receptor sites, which would represent a novel site of action for an anticonvulsant (Coulter et al 1995; Rosenfeld 1997). In contrast, TPM at concentrations up to 200 μM, had virtually no effect on the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) on the NMDA subtype of glutamate receptors (Coulter et al 1995). Because blocking of kainate-evoked currents is a known mechanism of decreasing neuronal excitability, this property of TPM may contribute to its anticonvulsant activity (Severt et al 1995). Subsequent studies demonstrated that TPM exerts a biphasic effect on kainate-evoked currents (Gibbs et al 2000), as revealed by an initial inhibition of the kainate-evoked currents, followed by a delayed additional inhibitory effect. The delayed effect was observed after the constant application of TPM for more than 10 minutes, and the kainate-induced currents did not fully return to the initial level during a 2- to 4-hour TPM washout period. It has been postulated that the delayed effect may be associated with an alteration of the phosphorylation state of kainate-activated channels.

Negative modulatory effect on L-type calcium channels

TPM reduces the amplitude of high voltage-activated calcium currents on some calcium channels subtypes, thus reducing neurotransmitter release and inhibiting calcium-dependent second-messenger systems (Zhang et al 1998). This activity has been demonstrated mainly at L-type high-voltage-activated calcium channels, in rat dentate gyrus granule cells (Zhang et al 2000). TPM produces a biphasic concentration-response curve, in which a greater reduction in L-type calcium currents was seen at 10 μmol/L than at 50 μmol/L, suggesting a mode of action different from other calcium channel blockers. These studies provide further evidence of the diverse mechanisms by which TPM appears to modulate neuronal excitability and suggest that an inhibitory effect on L-type calcium channels is another potential anticonvulsant mechanism.

Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes

TPM has been demonstrated to be a weak inhibitor of type II and type IV carbonic anhydrase (CA), thus modulating pH-dependent activation of voltage- and receptor-gated ion channels (Langtry et al 1997). TPM, like the minor anticonvulsant and CA inhibitor acetazolamide, contains a sulfamate moiety that is likely to be responsible for its CA-inhibiting properties. However, when compared with acetazolamide, TPM is approximately 10–100 times less potent as an inhibitor of these isoenzymes (Shank et al 1994; Dodgson et al 2000). Carbonic anhydrase inhibiting properties are considered not to be relevant to anticonvulsant activity; they are thought to be of greater relevance in determining some of the adverse effects, such as increased risk of nephrolithiasis and metabolic acidosis, as observed with acetazolamide (Wasserstein et al 1995). However, long-term safety data indicate that a very small percentage (approximately 1%–2%) of patients receiving TPM report the occurrence of renal stones (Shorvon 1996).

Effects on the phosphorylation state of membrane proteins

A proposed unifying mechanism that can possibly account for the wide range of pharmacological effects exerted by TPM on membrane receptor/channel complexes is the action on the phosphorylation state of membrane proteins (Shank et al 2000). Emerging evidence suggests that TPM may bind to phosphorylation sites within AMPA, kainate, GABAA, and voltage-activated sodium channels. TPM binds to such sites on the receptor proteins only in the dephosphorylated state, exerting a possible bifold effect. Therefore, TPM can modulate ion conductance through the channel, by an immediate allosteric action and it could exert a delayed effect by shifting the channels toward the dephosphorylated state (Van Kammen and Shank 2002).

Psychotropic profile of topiramate in patients with epilepsy

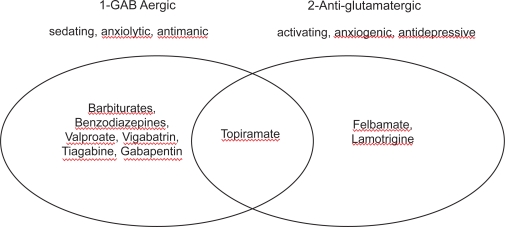

In early trials, using relatively high doses and also rapid dose titration schedules, TPM caused depressive problems in 15%–19% of treated patients, and psychosis in 3% (Shorvon 1996; Kellet et al 1999). Psychiatric disorders are not uncommon in patients with refractory epilepsy receiving conventional drugs and a cause-effect relationship cannot be easily established. It has been suggested that depression secondary to TPM treatment could be a function of high starting dose and rapid titration schedule, especially in patients with a psychiatric history (Crawford 1998; Mula et al 2003a). Moreover, depression has been described in normal volunteers and non-epileptic patients prescribed TPM (Martin et al 1999; Klufas et al 2001). TPM is characterized by a strong GABAergic activity, and the causal relationship between GABAergic properties and depressogenic effects of anticonvulsants is well known. However, there is no good and simple explanation for this relationship, although GABA certainly plays a role in the pathogenesis of depression. The classical AED which is depressogenic – phenobarbitone – is also a GABA-agonist. Among the new AEDs, VGA and TGB, whose central mechanism is characterized by a GABAergic effect, have been associated with depression in several clinical trials (Leppik 1995; Thomas et al 1996). Ketter and colleagues (Ketter et al 1999) have tried to explain these peculiar psychiatric effects of AEDs by distinguishing two main classes of anticonvulsants. The first class comprises drugs such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, VPA, vigabatrin, tiagabine, and gabapentin, which are primarily GABAergic and demonstrate sedation, fatigue, cognitive slowing, and weight gain, but also possible anxiolytic and antimanic effects. The second class, which includes the antiglutamatergic drugs felbamate and LTG, demonstrates activation, weight loss, as well as antidepressant and anxiogenic effects. In this composite picture, TPM holds an intermediate position because of its multiple modes of action (Figure 1). It has been postulated that patients who are primarily sedated may profit from the group of anti-glutamatergic drugs and that patients who are primarily activated benefit from drugs which have GABAergic properties (Schmitz 2002).

Figure 1.

Main categories of psychotropic profiles of anticonvulsants. Modified from Ketter et al (1999).

However, GABAergic neurotransmission is not enough to explain the association between TPM and depression. Other GABAergic AEDs, such as TGB, seem to be less depressogenic than TPM (Leppik 1995), and a recent study has demonstrated that hippocampal sclerosis is the main risk factor for the onset of depressive symptoms during therapy with TPM in patients with epilepsy, despite the same titration schedule (Mula et al 2003b). In other words, it is not relevant how rapidly we are potentiating the GABAergic transmission, but rather the potentiation of an aberrant network such as in patients with hippocampal atrophy. Interestingly, abnormalities in the hippocampi, especially smaller volumes, have been described also in patients with a primary affective disorder such as major depression (Bremner et al 2000; Frodl et al 2002).

In a recent survey of 431 patients with epilepsy treated with TPM, psychiatric adverse events occurred in 24% patients and an affective disorder developed in 10.7% patients (Mula et al 2003a). The prognosis of depression was good, with a small percentage of patients requiring admission to hospital and psychotropic prescription, and 87% of them recovered completely after drug discontinuation or dose reduction. In the same study the prevalence of psychosis was 3.7% (including postictal psychosis, schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy, and other psychotic states), with 93.8% of psychotic patients having complete remission after drug discontinuation. Aggressive behavior with or without irritability was observed in 5.6% of the patients, while other behavioral abnormalities, such as agitated behavior, anger/hostility, or anxiety, developed in 3.9% of patients.

In a population of 75 children with epilepsy taking TPM, 14.6% reported personality changes, mainly decreased functioning at school, aggressive and violent behavior, irritability, restlessness, and agitation, with a close temporal relation between the initiation of TPM and onset of the abnormalities, and a complete recovery when the drug was discontinued or dosage reduced (Gerber et al 2000). Finally, a few cases of manic episodes in patients on TPM without a previous psychiatric history have been reported in the literature (Schlatter et al 2001; Jochum et al 2002).

Rationale for the use of topiramate in affective disorders

The role of antiepileptic drugs in affective disorders

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a condition with complex symptomatology that requires lifetime therapy in the majority of patients and presents many challenges to clinicians. The pharmacological treatment of BD has evolved over the last few decades. Lithium and its augmentation strategies with antidepressants and antipsychotics has long been the therapeutic standard for the treatment of bipolar illness. Nevertheless, lithium therapy is associated with a 20%–40% rate of treatment failures (Dubovsky and Buzan 1997; Soares and Gershon 2000). Evidence for inadequate prophylactic response to lithium treatment in rapid cycling patients is fairly substantial (Post et al 1996). A poor response to lithium is also found in other bipolar subtypes, namely patients with dysphoric mania, mixed states, and comorbid medical illness or substance abuse (Calabrese et al 1996; Silverstone et al 1996; Swann et al 1997; Post et al 1998a). An increasingly common alternative or adjunctive therapy to lithium has been the use of second-generation mood-stabilizing anticonvulsant agents (Post et al 1998b). Several controlled studies have shown that valproic acid (VPA), which potentiates neuroinhibition by GABA, and CBZ, a sodium channel blocker, are effective treatments for acute and dysphoric mania (Post et al 1998b; Bowden et al 1994; Dunn et al 1998; Bowden et al 2000); besides, their effects on animal models of amygdala-kindled seizures are speculated to contribute to their mode of action in BD (Post and Uhde 1983; Stoll and Severus 1996). The kindling or sensitization model of epilepsy, in which repeated subconvulsive stimuli eventually produce full-blown seizures, may be one plausible model for BD, given a similar progression of affective illness in some patients from minor to major episodes and from triggered to spontaneous episodes (Post et al 1998b). Patients initially experience mood-related episodes in response to life events, but eventually the neurological and biochemical pathways responsible for these episodes are sufficiently reinforced to allow the autonomous initiation of further episodes (Post and Weiss 2004).

The preclinical data from AEDs suggest that there may be some general shared biological mechanisms between epilepsy and BD. For instance, the balance between inhibitory and excitatory amino acids (Petty 1995; Roettger and Amara 1999), and altered function of cellular cation pumps (ie, sodium and calcium channels) have been implicated (El Mallakh and Jaziri 1990) in both epilepsy and BD. The similarities shared by epilepsy and BD supported several clinical trials of newer AEDs in affective disorders. Among the newer anticonvulsant agents, LTG has been proven to be effective in bipolar depression (Calabrese et al 1999; Ernst and Goldberg 2003) and has recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the maintenance therapy of BD (Bowden et al 2003; Yatham 2004).

TPM exerts either direct or indirect effects on various receptor- and voltage-gated ion channels. In addition to epilepsy, the molecular targets of TPM have been associated with the underlying pathologic features of numerous disorders of the central nervous system (CNS), suggesting a role for TPM as a putative mood stabilizer. Encouragement about the potential for use of TPM in treating BD comes from several sources, briefly summarized as follows.

TPM has shown potent anticonvulsant effects in the amygdala-kindled rat (Wauquier and Zhou 1996). A first putative mechanism involves the sodium channel-blocking activity of TPM; this inhibitory effect on neuronal excitability is also shared by VPA, CBZ, and LTG. Augmentation of inhibitory neuronal responses to GABA seems to be another particularly significant action of TPM. A study has reported an increase in brain GABA after administration of TPM (3 mg/kg) to 6 healthy individuals (Kuzniecky et al 1998). Compared with baseline levels, brain GABA concentrations measured using in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, increased by 72% and 64% at 3 and 6 hours after TPM administration. Investigators have suggested that GABAergic neurons may play a role in mood disorders, including both major depression and BD. Preliminary evidence for this proposition came from a study in which progabide, a GABA agonist, was found to have a marked antidepressant effect (Bartholini 1985). Patients with BD have been found to have decreased plasma levels of GABA during both depressive and manic episodes (Petty 1995). Therefore low plasma GABA has been suggested to be a trait marker for bipolar illness (Petty et al 1993). Glutamate is the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain and, similar to LTG, TPM also negatively modulates glutamate transmission, although it exerts its antagonist activity at the AMPA/kainate type glutamate receptor rather than at the NMDA type receptor. A further mechanism that may be pertinent in the use of TPM for bipolar illness is that TPM is a calcium channel inhibitor, particularly active on L-type channels. Although reports of calcium channel antagonists such as verapamil and nimodipine are mixed regarding clinical efficacy in mania, Post et al (1998a) suggested calcium channel antagonism as a possible mechanism for mood stabilization.

The underlying pathophysiology of BD is not well understood, and it is likely that anticonvulsants exert their antimanic or mood stabilizing properties through a variety of mechanisms (Manji and Lenox 2000; Ketter et al 2003). Table 1 compares the mechanisms of action and psychotropic spectrum of TPM with the older and newer AEDs used for the treatment of affective disorders. As TPM combines the pharmacological properties of these anticonvulsants, and possesses additional mechanisms of action, it is a particularly promising candidate for the therapy of affective disorders.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of action and psychotropic spectrum of selected old and new anticonvulsants used in affective disorders

| Mechanisms of action | Psychotropic efficacy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blockade of voltage dependent sodium channels | Antagonism of glutamatergic receptors (receptor type) | Potentiation of GABA transmission | Blockade of calcium channels (channel type) | Mania | Depression | |

| CBZ | + | (+) (NMDA) | (+) | − | + | + |

| VPA | + | (+) (NMDA) | + | + (T) | ++ | + |

| LTG | + | (+) (NMDA) | − | + (L,N,P) | (+) | ++ |

| TPM | + | + (AMPA/k) | + | + (L) | + | (+) |

Abbreviations: AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid; CBZ, carbamazepine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; k, kainate; LTG, lamotrigine; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; TPM, topiramate; VPA, valproic acid.

Do we need another mood stabilizer?

A substantial proportion of patients with BD are not adequately responsive to clinical trials with lithium, CBZ and VPA, either alone, in combination, or with additional augmentation of antidepressants and antipsychotics (O’Connell et al 1991; Goldberg et al 1995; Gitlin et al 1995; Keck and McElroy 1996; Denicoff et al 1997). Therefore, TPM may represent an answer to the great need for the development of new and more effective treatments (Post and Speer 2002). It has been recognized that atypical forms of BD, such as rapid cycling and mixed states, are less responsive to lithium and, notably, they often show a better response to sodium channel-blocking agents, such as CBZ and oxcarbazepine, as compared to standard lithium therapy (Grinze and Walden 2002). Although improved response rates have resulted from CBZ therapy, many patients will nevertheless be nonresponsive or experience breakthrough episodes on maintenance therapy. In this respect, the peculiar mechanism by which TPM inhibits voltage-sensitive sodium channels could provide a rather interesting therapeutic option for treatment-resistant rapid cyclers.

Moreover, currently available agents utilized in both the acute management and the prophylaxis of BD are associated with a number of concerns, including diminished efficacy and the incidence of adverse events in significant subsets of individuals. These factors result in poor patient adherence with the pharmacological regimens and are often associated with serious consequences. One of the most troublesome side-effects of lithium and many mood stabilizers is weight gain, which has also been consistently observed in patients treated with the atypical antipsychotics, including clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone (Allison et al 1999; Ganguli 1999; Osser et al 1999; Wirshing et al 1999).

Quite interestingly, TPM therapy is associated with weight loss in overweight individuals, as shown by controlled trials in seizure disorder (Norton et al 1997; Rosenfeld et al 1997). A few preliminary studies have reported decreased appetite or weight loss in patients treated with TPM for BD (Gordon and Price 1995; Nemeroff 2003; Woods et al 2004).

A chart-review study of hospitalized patients with either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, BD, or other psychiatric diagnoses included 36 patients treated with a mean TPM dose of 260 mg/day (range 100–400) for a mean duration of 131 days (Chengappa et al 2002). Sixty-five percent of TPM-treated patients experienced weight loss. Mean weight loss with TPM was 1.2±6.3 kg (decrease in body weight 0.7%±7.2%), and mean reduction in body mass index (BMI) was 0.5±2.4 kg/m2; both were statistically significant compared with weight gain observed in the patients receiving either lithium or VPA. A more recent study by Vieta et al (2004) addressed the long-term efficacy and impact on body weight of the combination of olanzapine and TPM in 26 bipolar spectrum patients. In addition to experiencing improved mood stability, the 13 patients who completed the 1-year follow-up showed a weight change of −0.5±1.1 kg. Therefore, olanzapine plus TPM cotherapy appeared to carry some benefit for controlling weight gain in bipolar patients.

Taken together, these data indicate that BD patients receiving TPM experience body weight loss and a reduction in BMI. Although the mechanism responsible for TPM-induced weight loss is not well understood, the reduction in body weight seem to be a function of the baseline weight, the dosage and the duration of TPM treatment. This advantage of TPM possibly decreases the medical risks associated with obesity. Moreover, the tendency to decrease appetite may facilitate better long-term compliance in BD patients who have experienced weight gain on other psychotropic medications, including lithium, anticonvulsants, or atypical antipsychotics (Birt 2003).

Topiramate as add-on therapy for bipolar disorder

Based on this multi-faceted rationale, several open trials were undertaken in order to evaluate the overall efficacy and safety of TPM in the management of BD. Table 2 lists the studies reviewed in this paper.

Table 2.

Published clinical trials of topiramate in affective disorders

| Reference | Study design | Patients (n) Diagnosis | Mean dose (range) | Trial duration | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marcotte (1998) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 58

BD I and II, other psychiatric disorders |

200 mg/day (25–400) | 16 weeks | 62% marked or moderate improvement based on a CGI equivalent scale (modified Likert scale) |

| Chengappa et al (1999) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 20

BD I (18), schizoaffective disorder (2) |

210 mg/day (100–300) | 5 weeks | 60% much or very much improved based on ≥50% reduction in YMRS and CGI-BP scores |

| McElroy et al (2000) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 56

BD I and II |

245 mg/day (50–1200) | 30 weeks | 63% initially manic and 27% initially depressed much or very much improved based on CGI-BP, YMRS, and IDS scores |

| Eads and Kramer (2000) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 17

BD I (4), schizoaffective disorder (7), schizophrenia (6) |

826 mg/day (50–1600) | 32 weeks | 47% significantly improved based on GAF score |

| Vieta et al (2001) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 21

BD I and II, manic (9), hypomanic (3) and depressed (6) phases |

158 mg/day | 6 weeks | 28% showed decrease ≥50% in YMRS or HAM-D scores and decrease by >2 points in CGI-BP score |

| Vieta et al (2002) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 34

BD I (28), BD II (3), BD NOS (2), and schizoaffective disorder (1) |

200 mg/day (100–400) | 24 weeks | 59% initially manic and 55% initially depressed showed significant reduction in YMRS, HAM-D, and CGI-BP scores |

| Likouras et al (2004) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in refractory BD | 56

BD I |

290 mg/day (200–400) | 52 weeks | Frequency of manic and depressive episodes significantly decreased from 1.31 (±0.13) to 0.52 (±0.07) |

| Kusumakar et al (1999) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in rapid-cycling BD | 27

Rapid-cycling women (BP I=9; BP II=18) |

105 mg/day (100–150) | 16 weeks | 56% significantly improved based on HAM-D and YMRS scores |

| Grunze et al (2001) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in acute mania | 11

BD I – acute mania |

170 mg/day (25–200) | 10 days on, 5 days off, 10 days on | 64% and 73% showed YMRS ≥50% improvement in 1st and 2nd trial, respectively |

| Bozikas et al (2002) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in acute mania | 14

Acute mania |

310 mg/day (150–700) | 4 weeks | 61.5% showed a significant response (≥50% reduction in BRMS score) |

| Bahk et al (2005) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in acute mania | 33

Bipolar mania |

220 mg/day | 6 weeks | Overall significant decrease in YMRS (by 67.9%) and CGI (by 56.6%) scores |

| Hussain and Chaudhry (1999) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in bipolar depression | 45

BD I (27) and II (18) – major depressive episode |

275 mg/day (100–400) | 24 weeks | 42% showed complete remission (HAM-D scores between 3 and 7) and 27% showed partial remission (HAM-D scores between 8 and 12) |

| McIntyre et al (2002) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in bipolar depression | 18

BD I and II – depressed phase |

176 mg/day (50–300) | 8 weeks | 56% showed ≥50% reduction from baseline in HAM-D score |

| Guille and Sachs (2002) | Open-label study of add-on TPM in BD with psychiatric comorbidity | 14

BD I and II, with comorbid conditions |

100 mg/day (25–300) | 1–64 weeks (22 mean) | 64% showed increased level of functioning (4- to 15-point improvement in GAF score) |

| Calabrese et al (2001) | Open-label study of TPM as monotherapy in acute mania | 10

BD I – acute mania |

313 mg/day (50–612) | 2–28 days (16 mean) | 30% showed ≥50% decrease in YMRS score; 20% showed 25%–49% decrease in YMRS score |

Abbreviations: BD, bipolar disorder; BRMS, Bech and Rafaelsen Mania Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; CGI-BP, Clinical Global Impression-Bipolar version; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IDS, Inventory for Depressive Symptoms; TPM, topiramate; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Treatment-refractory bipolar disorder

In a retrospective chart review of 58 consecutive patients with psychiatric disorders refractory to previous treatments including newer anticonvulsants, Marcotte (1998) studied the efficacy and tolerability of TPM as adjunctive therapy. Most patients had a diagnosis of rapid-cycling BD characterized by manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes. TPM was added to existing therapy at an initial dose of 25 mg/day and titrated by 50-mg increments every 7 days until improvement occurred or a total dosage of 400 mg daily was reached. The mean dose was 200 mg/day, with a mean duration of 16 weeks of TPM treatment. Clinical Global Impression (CGI)-equivalent scores showed marked or moderate improvement in 36 (62%) of 58 total patients, and among patients with rapid-cycling BD, 39 (89%) showed marked or moderate improvement. Adverse events were minor and predominantly related to the gastrointestinal tract (nausea, frequent bowel movements) and CNS (paraesthesias, somnolence, fatigue, impaired concentration).

A second open-label, 5-week study by Chengappa et al (1999) evaluated the effects of TPM as adjunctive treatment in the manic and mixed phases of 20 patients with bipolar spectrum disorder, refractory to previous mood-stabilizing therapies. TPM was initiated at a dosage of 25 mg/day and increased to a target dose of 100–300 mg/day by increments of 25–50 mg/day. Patients were evaluated weekly using the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), and the Clinical Global Impression-Bipolar version (CGI-BP). Twelve (60%) patients were rated as responders to treatment (≥50% reduction in YMRS and CGI-BP rating of much or very much improved) and 3 (15%) patients were minimally improved. Treatment with TPM appeared well tolerated. Side-effects in this study, nearly all related to the CNS or gastrointestinal tract, were transient and resolved spontaneously. All patients showed a progressive decline in weight during the 5 weeks of TPM therapy, with a mean decrease of 4.7 kg.

Similar findings were obtained by McElroy et al (2000) in another open-label, prospective, add-on evaluation of TPM in 56 bipolar outpatients who had an inadequate response to, or were unable to tolerate, at least one standard mood stabilizer. TPM therapy was started at a dose of 25–50 mg/day and increased by 25–50 mg/day every 3–14 days to a maximum dosage of 1200 mg/day. Two patients discontinued TPM in the first week because of dizziness and hallucinations. The mean treatment duration for all 54 patients was 214.2 days, and the mean TPM dosage was 244.7 mg/day. Patient response was measured every 2 weeks for the first 10 weeks and monthly thereafter using the CGI-BP, YMRS, and the Inventory for Depressive Symptoms (IDS). CGI-BP scores at 10 weeks showed that 19 (63%) of 30 initially manic patients were much or very much improved in their manic symptoms; these patients also displayed significant decreases in YMRS and IDS. Overall, patients with mania at baseline showed significant response to TPM, but depressed and euthymic patients showed no significant changes. TPM was generally well tolerated, with mild and transient CNS and gastrointestinal-related adverse effects, including reduced appetite, cognitive impairment, fatigue, and sedation. Statistically significant decreases in both weight and BMI were also observed.

Eads and Kramer (2000) have also reported a significant improvement in mood and global functioning with TPM in 17 patients with treatment-refractory mood disorders. TPM was added to existing treatment and titrated to a mean dose of 826 mg/day (range 50–1600 mg/day). Eight patients discontinued TPM due to CNS side-effects, such as sedation, confusion, dizziness, fatigue, and impaired concentration. All the remaining 9 patients responded to the drug, and 8 of them showed an 8- to 20-point improvement of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score.

The effectiveness of TPM as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant BD has also been reported by Vieta et al (2001) in a prospective, multicenter, open-label study on 21 BD I and II patients in a manic (n=9), hypomanic (n=3) or depressed (n=6) phase. All subjects were started on adjunctive therapy with TPM 25 mg/day, with 25- to 50-mg increments every 3–7 days to a mean dose of 158 mg/day. After 6 weeks of therapy, 6 of the 15 patients who completed the study were rated as responsive to TPM (≥50% reduction in the YMRS or HAM-D and a decrease of 2 points on the CGI-BP). Overall, TPM was well tolerated, with adverse effects mostly related to the gastrointestinal tract and CNS. The authors concluded that TPM may be useful as a safe and effective therapy in the treatment of patients with refractory BD.

The same authors (Vieta et al 2002) published the results of a further study of TPM as add-on, long-term therapy for treatment-resistant bipolar disorder. Thirty-four DSM-IV bipolar-spectrum patients received increasing doses of TPM (mean dose at endpoint: 202 mg/day) as add-on treatment for their manic (n=17), depressive (n=11), hypomanic (n=3), or mixed (n=3) symptoms. Twenty-five patients completed the 6-month follow-up. The intention-to-treat analysis showed a significant reduction in YMRS, HAM-D, and CGI-BP scores (p<0.0001) in 59% of manic patients and 55% of depressed patients, suggesting that TPM may be useful in the long-term treatment of bipolar spectrum disorders. Overall, the drug was well tolerated, and 10 patients experienced moderate weight loss during the follow-up period.

In a recent open-label study by Lykouras et al (2004), 56 patients receiving outpatient treatment for bipolar I disorder who had been on mood stabilizers, and had relapsed at least once in the past 12 months, were treated with TPM in an add-on design for one year. Patients were assessed biweekly for the first 3 months and every month thereafter. Fifty patients completed the study and reported a significant reduction of new manic and depressive episodes compared to the past 12 months. The mean TPM dosage was 290 mg/day, and the most common adverse effects were reduced appetite, fatigue and somnolence. This exploratory study suggests that the addition of TPM could be a feasible option for the maintenance therapy of patients with treatment-refractory bipolar I disorder, thus encouraging further investigations, especially with controlled trials, for its long-term effect.

Rapid-cycling bipolar disorder

Kusumakar et al (Kusumakar et al 1999) completed an open-label study of TPM as adjunctive therapy for rapid-cycling BD. Twenty-seven female patients suffering from rapid-cycling BD type I (n=9) and type II (n=18) were given TPM at 25 mg/day, with weekly increments of 25 mg/day up to an average maximum dosage of 105.2 mg/day. All patients were refractory to two or more previous mood stabilizers, including lithium and VPA, for at least 12 months, and had experienced significant weight gain (≥20%) from previous treatments. After 16 weeks of therapy, 15 patients exhibited clinically significant improvement in mood and achieved euthymia. Mood assessment (severity and cycle length) was performed by the rating scales HAM-D and YMRS, and outcome measures included sleep and weight loss. Nine patients (33%) reported a weight loss of at least 5%, while 5 patients experienced a reduction of 1%–4%. Main reasons for discontinuation of treatment (4 subjects) were adverse effects, namely drowsiness, ataxia, confusion, and re-emergence of psychosis, all of which occurred on or before week 3.

Acute mania

Grunze et al (2001) assessed the antimanic efficacy of TPM as adjunctive treatment for 11 acutely manic patients in an on-off-on study design. TPM was given openly after stable serum levels of mood stabilizers and/or antipsychotics had been achieved, at a starting dose of 25 mg/day, and titrated within 1 week to a final dose of 25–200 mg/day, depending on clinical efficacy and tolerability. After 10 days of therapy, TPM was discontinued, while concomitant medications remained unchanged. On day 16, TPM was reintroduced and titrated to former dosages for another 10 days. By day 10, 7 of 11 patients showed a good antimanic response with ≥50% reduction in YMRS score. During the “off” period, 7 patients worsened again. At the end of the study, after the reintroduction of TPM, all patients improved again within a week, with 8 patients displaying 50% or greater YMRS score reduction. Two patients reported sedation and another patient showed psychotic features following a rapid increase in the dose of TPM; otherwise TPM was generally well tolerated, without measurable effects on the plasma levels of concomitant medications.

A clinical trial by Bozikas et al (2002) evaluated 4 weeks of treatment with TPM in 14 patients admitted to the hospital with acute mania. Nine patients received TPM as mono-therapy; 5 patients received concomitant therapies including zuclopenthixol acetate, VPA, CBZ, and risperidone; benzodiazepines were used as needed to manage all patients. The mean TPM dose in the study was 310 mg/day (range 150–700). Patients were assessed every week for 4 weeks with the Bech and Rafaelsen Mania Scale (BRMS). Mean BRMS scores declined from 26.2 to 11.6 in the fourth week (p<0.001); a significant decline (p<0.001) was observed after the first week. Response rate (≥50% reduction of BRMS) was 61.5% (8 out of 13 patients). All patients tolerated well TPM. Reduced appetite and weight loss was observed in 4 obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2) patients; however, 2 patients presented weight gain.

A recent study by Bahk et al (2005) compared the effectiveness and tolerability of TPM and VPA in combination with risperidone for the treatment of 74 patients who met the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar mania. The recommended starting doses were 20 mg/day for TPM (with 25–50 mg/day increases every 2–5 days to a mean daily dose of 220.6 mg) and 750 mg/day for VPA (with 250–500 mg/day increases every 2–5 days to a mean daily dose of 908.3 mg). From the baseline to the endpoint (week 6), the YMRS and CGI scores were reduced by 67.9% and 56.6% in the TPM plus risperidone group and by 63.7% and 58.2% in the VPA plus risperidone group. Weight and BMI increased significantly by 3.6% and 3.3% from the baseline to the endpoint in the VPA plus risperidone group, while they decreased by 0.5% and 0.4%, respectively, with no significant difference in the TPM plus risperidone group. No serious adverse events were reported in either group. The authors concluded that TPM may represent a promising alternative to a weight-gain liable mood stabilizer, such as VPA, for the treatment of acute mania.

Van Kammen and Shank (2002) conducted a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-week study of TPM in hospitalized patients with a DSM-IV based diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. All patients entering the study had a YMRS score of 20 or greater. They were randomized to receive either TPM 512 mg/day (n=33), TPM 256 mg/day (n=33) or placebo (n=31). TPM was titrated to target dose in 10 days, and the efficacy of treatment against acute mania and mixed episodes was measured by changes in the YMRS as well as secondary measures, including the GAF scale. Both the interim analysis and the efficacy analysis after the exclusion of the patients who were taking antidepressant prior to study entry showed a significant reduction in YMRS scores (p=0.027 and p=0.049, respectively) for patients taking TPM 512 mg/day when compared with patients taking placebo. This difference was not maintained in the intention-to-treat analyses due to a higher than expected placebo response. The authors suggest several reasons for the increased placebo response in mania: manic episodes end spontaneously and are time limited; hypomania is likely to respond to environmental interventions such as hospitalisation; manic symptoms improve when antidepressant treatment is discontinued; pseudo-manic patients (eg, patients with perimenstrual dysphoric disorder) are included. The authors concluded that TPM may have a dose-dependent response in manic patients with bipolar I disorder.

Bipolar depression

An open-label trial by Hussain and Chaudhry (1999) suggests that TPM may also be useful in the treatment of depressive episodes in bipolar patients. Forty-five patients with bipolar I disorder (n=27) and bipolar II disorder (n=18) suffering from a major depressive episode and refractory to previous mood-stabilizing therapy were given add-on TPM at a starting dose of 25 mg/day, then titrated to a mean dose of 275 mg/day. Of the 31 patients who completed the trial, 19 were rated as full responders (final HAM-D score between 3 and 7), and 12 patients as partial responders (final HAM-D-17 score between 8 and 12). Responses to TPM were observed within the first 4 weeks of therapy. TPM was generally well tolerated, and the main adverse effects leading to withdrawal were dizziness and nausea.

McIntyre et al (2002) compared the efficacy and tolerability of TPM and sustained-release bupropion added to mood stabilizers in a randomized, single-blind study of 36 outpatients with bipolar I or II depression (baseline HAM-D-17 scores ≥16). Each 18-patient treatment group received escalating doses of either TPM (to a mean dose of 176 mg/day) or bupropion (250 mg/day) for 8 weeks. A significant and comparable reduction in depressive symptoms (≥50% reduction in HAM-D-17 score between baseline and endpoint) was observed during treatment with the two drugs. Medications were generally well tolerated, though 6 TPM and 4 bupropion patients discontinued due to side-effects. No cases of induction of mania were observed. Weight loss was noted in both groups (mean weight loss was 5.8 kg for TPM and 1.3 kg for bupropion).

Bipolar disorder with psychiatric comorbidity

Guille and Sachs (2002) assessed the efficacy and tolerability of TPM in 14 patients with treatment-refractory bipolar disorder as well as comorbid psychiatric conditions, including bulimia, anorexia nervosa, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and Tourette’s syndrome. TPM was initiated at a dose of either 25 or 50 mg and data were collected for a mean duration of 22.4±22.0 weeks; the mean dose at endpoint was 100mg/day. Eleven patients remained on treatment for longer than 2 weeks. TPM was discontinued in 5 patients due to side-effects (rash, paraesthesias, cognitive impairment, and sedation) and in 2 patients due to lack of efficacy after less than 2 weeks. Nine patients (64%) experienced an increased level of functioning (4- to 15-point improvement in GAF score) and 4 experienced a decrease in symptom severity of bipolar illness (by ≥1 CGI point) during treatment with adjunctive TPM. Eight patients (73%) experienced a significant improvement in their comorbid conditions as measured by the CGI-I (Clinical Global Impression of Improvement). Patients with a BMI≥28 (n=4) experienced a mean weight loss of 29.7 lb while on TPM. These findings suggest that TPM represents a promising agent for the treatment of bipolar disorder associated with comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as eating disorders and obesity.

Topiramate monotherapy for bipolar disorder

Acute mania

Open-label TPM was given as monotherapy for acute mania in a small pilot study by Calabrese et al (2001) of 10 patients with bipolar disorder type I who were unresponsive to lithium and/or VPA. After a 3-day washout period, TPM was initiated at 50 mg/day and titrated upward as tolerated by 50 mg every 3 days (mean dosage 313 mg/day) for up to 28 days. Three patients had a ≥50% reduction in mania scores (as assessed by YMRS); another 2 patients had scores that improved by 25%–49%. Moreover, 5 patients had increased level of functioning and global impression scores (as assessed by CGI-I). Response occurred between 200 and 400 mg/day. Treatment was generally well tolerated, with paraesthesias as the most common side-effect. Three of 4 patients completing 28 days of treatment reported a significant weight loss.

What is the role of topiramate in bipolar disorder?

The results of preliminary studies show promise for TPM as an addition to the agents currently available to treat patients with bipolar illness. Clinical data from uncontrolled open-label studies and patient-reviews involving several hundred subjects suggest that TPM is effective in the treatment of various presentations of BD, especially in acutely manic and rapid cycling patients (Chengappa et al 2001; Maidment 2002; Suppes 2002). In the majority of these studies, over 50% of patients who were previous non-responders to or intolerant of lithium or other mood stabilizing therapy showed an improvement following treatment with TPM, according to standard assessment scale scores.

Open-label experience indicates better antimanic than antidepressant efficacy (Yatham et al 2002; Evins 2003), since the data for TPM in bipolar depression have shown mixed results. Moreover, induction of depression has been described as a possible consequence of anticonvulsant therapy with TPM among some patients with epilepsy (Ketter et al 1999; Mula et al 2003a). However, the scarcity of published randomized trials limits definitive conclusions about the acute antidepressant properties of TPM. Similarly, the role of TPM in the preventive treatment of BD is not known due to lack of data. Although most studies described here had a relatively short duration, overall efficacy and tolerability results support further study on its use for maintenance treatment of BD, as an adjunctive agent or possibly as monotherapy. Combination therapy of AEDs with lithium and other mood stabilizers appears to be more effective than monotherapy with these agents in many bipolar patients (Pies 2002). TPM is more likely to be prescribed in combination with another mood stabilizer for the management of BD. Although combination therapy may increase the risk of toxicity and drug interactions, particularly with psychotropic agents (Freeman and Stoll 1998), the generally benign side-effect profile of TPM and early clinical findings are good indications that this drug may be used safely in combination with other mood stabilizers in BD. In particular, the observed anorexic or weight loss effect of TPM is noteworthy, since it promotes better long-term compliance in patients who have experienced weight gain on other psychotropic agents, including lithium, anticonvulsants, or atypical antipsychotics. A clinical scenario where this agent may be arguably helpful is among obese bipolar subjects where efficacy combined with weight loss is required. Other clinically relevant target populations among bipolar patients may include rapid-cycling subjects, and subjects whose mood instability is complicated by TPM-responsive comorbid conditions, such as migraine, neuropathic pain, bulimia, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Clinical studies of TPM in psychiatric populations report a similar tolerability profile to that observed in epilepsy. The most common adverse events are CNS-related and include somnolence, fatigue, dizziness, headache, paraesthesias, ataxia, diplopia, and nystagmus. Cognitive impairment has been associated with TPM therapy: impaired attention and concentration, memory problems, confusion, abnormal thinking, word-finding difficulties, dysnomia/anomia, as well as psychomotor slowing, have all been reported in both mood disorders and epilepsy (Chengappa et al 2001; Tatum et al 2001; Maidment 2002; Suppes 2002; Mula et al 2003c). Notably, most side-effects are transient and tend to resolve spontaneously or with dosage reduction. Moreover, in subjects with epilepsy, CNS adverse effects may often be prevented or minimized by a slower titration rate (25 mg every week), lower doses of TPM, and fewer adjunctive therapies, although some of them seem to occur in a subgroup of patients with a specific biologic vulnerability (Rosenfeld et al 1992; Shorvon 1996; Mula et al 2003b).

At this time, the majority of the available data on TPM in affective disorders are limited by open and naturalistic studies which have several methodological shortcomings. These studies were non-randomized and open-label in design, involving heterogeneous patient populations (such as bipolar I and II, schizoaffective, rapid-cycling course), with incomplete information on current or past treatment for the illness. In most cases, TPM was used as adjunctive therapy in patients inadequately responsive to or intolerant of standard mood stabilizers, potentially introducing outcome bias. Finally, in the absence of head-to-head controlled monotherapy comparisons, it is difficult to compare and contrast efficacy benefits versus side-effect risks for TPM and the long-standing bipolar treatment agents. Therefore, further studies of TPM are warranted, with double-blind placebo-controlled designs to provide more definite data on the efficacy and safety of this agent as a mood stabilizer for subjects suffering from bipolar disorder.

Conclusions

TPM has a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, facilitating a balance between inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmission and overall decreasing neuronal excitability. AEDs such as CBZ and VPA have already shown efficacy as mood stabilizers, and the newer anticonvulsant LTG has recently been approved for the maintenance treatment of BD type II. However, TPM has several pharmacological advantages, including low protein binding, minimal hepatic metabolism and mainly unchanged renal excretion, a long half-life that permits twice daily dosing, few drug interactions in combination therapy, and no requirement for blood level monitoring. Preliminary open-label clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of TPM, both as an add-on treatment and as monotherapy, in various episodes or subtypes of BD, including acute mania, depression, rapid-cycling disorder, mixed mania, and BD refractory to usual medications. Results of these early trials are promising, particularly in patients who are acutely manic or rapid cyclers, and those who failed to respond to standard mood stabilizing pharmacological regimens. In addition to its efficacy, TPM offers a favorable side-effect profile, which includes decreased appetite and weight loss in some patients. This effect, especially positive for subjects who have gained weight on lithium, other AEDs, or atypical antipsychotics, may ultimately contribute enhancing compliance to the mood stabilizing treatment. On the whole, TPM is well tolerated by both epileptic and bipolar patients, the most commonly reported adverse events being minor CNS-related effects, including cognitive slowing, which tend to resolve over time with dosage reduction.

Footnotes

Disclosures

There are no potential financial interests or conflict of interests between the authors and this paper. Dr Marco Mula and Dr Andrea Cavanna have never received personal honoraria from pharmaceutical companies. Prof Francesco Monaco has previously received speaker fees from Janssen-Cilag.

References

- Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1686–96. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk WM, Shin YC, Woo JM, et al. Topiramate and divalproex in combination with risperidone for acute mania: a randomized open-label study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholini G. GABA receptor agonists: pharmacological spectrum and therapeutic actions. Med Res Rev. 1985;5:55–75. doi: 10.1002/med.2610050103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birt J. Management of weight gain associated with antipsychotics. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2003;15:49–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1023280610379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biton V, Montouris GD, Ritter F. A study of topiramate in primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Neurology. 1999;52:1330–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, et al. Efficacy of divalproex vs. lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;271:918–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Divalproex Maintenance Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:481–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.5.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Sachs G, et al. A placebo-controlled 18-month trial of lamotrigine and lithium maintenance treatment in recently manic or hypomanic patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:392–400. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozikas VP, Petrikis P, Kourtis A, et al. Treatment of acute mania with topiramate in hospitalized patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1203–6. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00323-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremner JD, Narayan M, Anderson ER, et al. Hippocampal volume reduction in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:115–18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.157.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Wolf HH, Swinyard EA, et al. The novel anticonvulsant topiramate enhances GABA-mediated chloride flux. Epilepsia. 1993;34:122–3. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Faterni SH, Kujawa M, et al. Predictors of response to mood stabilizers. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16(Suppl 1):24–31. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199604001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs G, et al. A double blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:79–88. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, et al. A pilot study of topiramate as monotherapy in the treatment of acute mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:340–2. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa KNR, Rathore D, Levine J, et al. Topiramate as add-on treatment for patients with bipolar mania. Bipolar Disord. 1999;1:42–53. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.1999.10111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa KN, Gershon S, Levine J. The evolving role of topiramate among other mood stabilizers in the management of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:215–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa KN, Chalasani L, Brar JS, et al. Changes in body weight and body mass index among psychiatric patients receiving lithium, valproate, or topiramate: an open-label, nonrandomized chart review. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1576–84. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter DA, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Selective effects of topiramate on sustained repetitive firing and spontaneous bursting in cultured hippocampal neurons. Epilepsia. 1993;34(Suppl 2):123. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb06048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter DA, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Topiramate effects on excitatory amino acid-mediated responses in cultured hippocampal neurons: selective blockade of kainite currents. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 3):40. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford P. An audit of topiramate use in a general neurology clinic. Seizure. 1998;7:207–11. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(98)80037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico D, Grazzi L, Bussone G. Topiramate in the prevention of migraine: a review of its efficacy, tolerability, and acceptibility. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2006;2:261–7. doi: 10.2147/nedt.2006.2.3.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ, Sombati S, Coulter DA. Effects of topiramate on sustained repetitive firing and spontaneous recurrent seizure discharges in cultured hippocampal neurons. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):40–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb06048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denicoff KD, Smith-Jackson EE, Disney ER, et al. Comparative prophylactic efficacy of lithium, carbamazepine, and the combination in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:470–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson SJ, Shank RP, Maryanoff BE. Topiramate as an inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):35–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb06047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubovsky SL, Buzan RD. Novel alternatives and supplements to lithium and anticonvulsants for bipolar affective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:224–42. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RT, Frye MS, Kimbrell TA, et al. The efficacy and use of anticonvulsants in mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:215–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eads L, Kramer T. Effects of topiramate on global functioning in treatment-refractory mood disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000;3(Suppl 1):340. [Google Scholar]

- El Mallakh RS, Jaziri WA. Calcium channel blockers in affective illness: role of sodium-calcium exchange. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:203–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antidepressant properties of anticonvulsant drugs for bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:182–92. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200304000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evins AE. Efficacy of newer anticonvulsant medications in bipolar spectrum mood disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 8):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faught E, Wilder BJ, Ramsay RE, et al. Topiramate placebo-controlled dose-ranging trial in refractory partial epilepsy using 200-, 400-, 600-mg dosages. Neurology. 1996;46:1684–90. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MP, Stoll AL. Mood stabilizer combinations: a review of safety and efficacy. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:12–21. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodl T, Meisenzahl EM, Zetzsche T, et al. Hippocampal changes in patients with a first episode of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1112–18. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli R. Weight gain associated with antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber PE, Hamiwka L, Connolly MB, et al. Factors associated with behavioural and cognitive abnormalities in children receiving topiramate. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:200–3. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(99)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs JW, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RI, et al. Cellular actions of topiramate: blockade of kainate-evoked inward currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):10–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb02164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, et al. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1635–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser TA. Topiramate. Epilepsia. 1999;40(Suppl 5):71–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JF, Harrow M, Grossman LS. Course and outcome in bipolar affective disorder: a longitudinal follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:379–84. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A, Price LH. Mood stabilization and weight loss with topiramate. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(Suppl 6):968–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.968a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunze HC, Normann C, Langosch J, et al. Antimanic efficacy of topiramate in 11 patients in an open trial with an on-off-on design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:464–8. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunze H, Walden J. Relevance of new and newly rediscovered anticonvulsants for atypical forms of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2002;72(Suppl 1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guille C, Sachs G. Clinical outcome of adjunctive topiramate treatment in a sample of refractory bipolar patients with comorbid conditions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002;26:1035–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(01)00278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain MZ, Chaudhry Z. Treatment of bipolar depression with topiramate. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9(Suppl 5):222. [Google Scholar]

- Jochum T, Bär KJ, Sauer H. Topiramate induced manic episode. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:202–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.2.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamin M. Topiramate: clinical efficacy and use in nonepileptic disorders. In: Levy RH, Mattson RH, Meldrum BS, et al., editors. Anti-epileptic drugs. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 753–9. [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL. Outcome in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199604001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellett MW, Smith DF, Stockton PA, et al. Topiramate in clinical practice: first year’s postlicensing experience in a specialist epilepsy clinic. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:759–63. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.6.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter TA, Post RM, Theodore WH. Positive and negative psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in patients with seizure disorders. Neurology. 1999;53(Suppl 2):53–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter TA, Wang PW, Becker OV, et al. The diverse role of anticonvulsants in bipolar disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2003;15:95–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1024636309185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klufas A, Thompson D. Topiramate-induced depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1736. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumakar V, Yatham L, Kutcher S, et al. Preliminary, open-label study of topiramate in rapid-cycling bipolar women. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9:357. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzniecky R, Hetherington H, Ho S, et al. Topiramate increases cerebral GABA in healthy humans. Neurology. 1998;51:627–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langtry HD, Gillis JC, Davis R. Topiramate: a review of its pharma-codynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy in the management of epilepsy. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 5):752–73. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199754050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppik I. Tiagabine: the safety landscape. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 6):10–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb06009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykouras L, Hatzimanolis J. Adjunctive topiramate in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders: an open-label study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20:843–7. doi: 10.1185/030079904125003665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment ID. The use of topiramate in mood stabilization. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1277–81. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manji HK, Lenox RH. The nature of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 13):42–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte D. Use of topiramate, a new anti-epileptic as a mood stabilizer. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:245–51. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Kuzniecky R, Ho S, et al. Cognitive effects of topiramate, gabapentin and lamotrigine in healthy young adults. Neurology. 1999;52:321–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Suppes T, Keck PE, et al. Open-label adjunctive topiramate in the treatment of bipolar disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:1025–33. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00316-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre RS, Mancini DA, McCann SM, et al. Topiramate versus bupropion SR when added to mood stabilizer therapy for the depressive phase of bipolar disorder: a preliminary single-blind study. Bipolar Disord. 2002;4:207–13. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean MJ, Bukhari AA, Wamil AW. Effects of topiramate on sodium-dependent action-potential firing by mouse spinal cord neurons in cell culture. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):21–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaeloff Y, de Saint-Martin A, Mancini J, et al. Topiramate: efficacy and tolerability in children according to epilepsy syndromes. Epilepsy Res. 2003;53:225–32. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(03)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mula M, Trimble MR, Lhatoo SD, et al. Topiramate and psychiatric adverse events in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003a;44:659–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.05402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mula M, Trimble MR, Sander WAS. The role of hippocampal sclerosis in topiramate-related depression and cognitive deficits in people with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003b;44:1573–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.19103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mula M, Trimble MR, Thompson P, et al. Topiramate and wordfinding difficulties in patients with epilepsy. Neurology. 2003c;60:1104–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000056637.37509.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff CB. Safety of available agents used to treat bipolar disorder: focus on weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:532–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton J, Potter D, Edwards K. Sustained weight loss patterns with topiramate. Epilepsia. 1997;38(Suppl 3):60. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RA, Mayo JA, Flatow L, et al. Outcome of bipolar disorder on long-term treatment with lithium. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:123–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osser DN, Najarian DM, Dufresne RL. Olanzapine increases weight and serum triglyceride levels. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:767–70. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perucca E. A pharmacological and clinical review on topiramate, a new antiepileptic drug. Pharmacol Res. 1997;35:241–56. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1997.0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty F, Kramer GL, Fulton M, et al. Low plasma GABA is a trait-like marker for bipolar illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:125–32. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty F. GABA and mood disorders: a brief review and hypothesis. J Affect Disord. 1995;34:275–81. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(95)00025-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pies R. Combining lithium and anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2002;14:223–32. doi: 10.1023/a:1021969001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Uhde TW. Treatment of mood disorders with antiepileptic medications: clinical and theoretical implications. Epilepsia. 1983;24(Suppl 1):97–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Ketter TA, Denicoff K, et al. The place of anticonvulsant therapy in bipolar illness. Psychopharmacology Berl. 1996;128:115–29. doi: 10.1007/s002130050117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Denicoff KD, Frye MA, et al. A history of the use of anticonvulsants as mood stabilizers in the last two decades of the 20th century. Neuropsychobiology. 1998a;38(Suppl 3):152–66. doi: 10.1159/000026532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, et al. Beyond lithium in the treatment of bipolar illness. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998b;19:206–19. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Speer AM. A brief history of anticonvulsant use in affective disorders. In: Trimble MR, Schmitz B, editors. Seizures, affective disorders and anticonvulsant drugs. Guilford: Clarius Press; 2002. pp. 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Weiss SR. Convergences in course of illness and treatments of the epilepsies and recurrent affective disorders. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2004;35:14–24. doi: 10.1177/155005940403500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privitera M, Fincham R, Penry J, et al. Topiramate placebo-controlled dose-ranging trial in refractory partial epilepsy using 600-, 800-, and 1,000-mg daily dosages. Neurology. 1996;46:1678–83. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.6.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privitera MD. Topiramate: a new antiepileptic drug. Ann Pharmacother. 1997;31:1164–73. doi: 10.1177/106002809703101010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reife R, Pledger G, Wu S-C. Topiramate as add-on therapy: pooled analysis of randomised controlled trials in adults. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):66–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb02175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roettger VR, Amara SG. GABA and glutamate transporters: therapeutic and etiologic implications for epilepsy. Adv Neurol. 1999;79:551–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld WE, Holmes GB, Hunt TL, et al. Topiramate: effective dosaging enhances potential for success. Epilepsia. 1992;33(Suppl 3):118. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld WE. Topiramate: a review of preclinical, pharmacokinetic, and clinical data. Clin Ther. 1997;19:1294–308. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(97)80006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld WE, Schaefer PA, Pace K. Weight loss patterns with topiramate therapy. Epilepsia. 1997;38(Suppl 3):58. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeo RC, Glauser TA, Ritter RC, et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of topiramate in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1882–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlatter FJ, Soutullo CA, Cervera-Enguix S. First break of mania associated with topiramate treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:464–5. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200108000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz B. Depressive disorders in epilepsy. In: Trimble MR, Schmitz B, editors. Seizures, affective disorders and anticonvulsant drugs. Guilford: Clarius Press; 2002. pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Severt L, Coulter DA, Sombati S, et al. Topiramate selectively blocks kainite currents in cultured hippocampal neurons. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 4):38. [Google Scholar]

- Shank RP, Gardocki JF, Vaught JL, et al. Topiramate: preclinical evaluation of a structurally novel anticonvulsant. Epilepsia. 1994;35:450–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shank RP, Gardocki JF, Streeter AJ, et al. An overview of preclinical aspects of topiramate: pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, and mechanism of action. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorvon SD. Safety of topiramate: adverse events and relationships to dosing. Epilepsia. 1996;37(Suppl 2):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb06029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone T, Romans S. Long term treatment of bipolar disorders. Drugs. 1996;51:367–82. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares JC, Gershon S. The psychopharmacologic specificity of the lithium ion: origins and trajectory. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina E, Perugi G. Antiepileptic drugs: indications other than epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2004;6:57–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll AL, Severus WE. Mood stabilizers: shared mechanisms of action at postsynaptic signal-transduction and kindling processes. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1996;4:77–89. doi: 10.3109/10673229609030527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppes T. Review of the use of topiramate for treatment of bipolar disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:599–609. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, et al. Depression during mania: treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130041008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatum WO, French JA, Morris GL, et al. Postmarketing experience with topiramate and cognition. Epilepsia. 2001;32:1134–1140. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.41700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L, Trimble M, Schmitz B, et al. Vigabatrin and behaviour disorders: retrospective survey. Epilepsy Res. 1996;25:21–7. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(96)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kammen DP, Shank RP. New anticonvulsants in affective disorder: topiramate. In: Trimble MR, Schmitz B, editors. Seizures, affective disorders and anticonvulsant drugs. Guilford: Clarius Press; 2002. pp. 143–66. [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Gilabert A, Rodriguez A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of topiramate in treatment-resistant bipolar disorder. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2001;29:148–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Torrent C, Garcia-Ribas G, et al. Use of topiramate in treatment-resistant bipolar spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:431–5. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200208000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Sanchez-Moreno J, Goikolea JM, et al. Effects on weight and outcome of long-term olanzapine-topiramate combination treatment in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:374–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130556.01373.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein AG, Rak I, Reife RA. Nephrolithiasis during treatment with topiramate. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 3):153. [Google Scholar]

- Wauquier A, Zhou S. Topiramate: a potent anticonvulsant in the amygdala-kindled rat. Epilepsy Res. 1996;24:73–7. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HS, Brown SD, Skeen GA, et al. The investigational anticonvulsant topiramate potentiates GABA-evoked currents in mouse cortical neurons. Epilepsia. 1995;36:34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HS, Brown SD, Woodhead JH, et al. Topiramate enhances GABA-mediated chloride flux and GABA-evoked chloride currents in murine brain neurons and increases seizure threshold. Epilepsy Res. 1997;28:167–79. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(97)00045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HS, Brown SD, Woodhead JH, et al. Topiramate modulates GABA-evoked currents in murine cortical neurons by a nonbenzodiazepine mechanism. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HS. Topiramate: mechanisms of action. In: Levy RH, Mattson RH, Meldrum BS, et al., editors. Antiepileptic drugs. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 719–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Kysar L, et al. Novel antipsychotics: comparison of weight gain liabilities. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:358–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods TM, Eichner SF, Franks AS. Weight gain mitigation with topiramate in mood disorders. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:887–91. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham LN, Kusumakar V, Calabrese JR, et al. Third generation anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder: a review of efficacy and summary of clinical recommendations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:275–83. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham LN. Newer anticonvulsants in the treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 10):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Velumian AA, Jones OT, et al. Topiramate reduces high-voltage activated Ca2+ currents in CA1 pyramidal neurons in vitro. Epilepsia. 1998;39(Suppl 6):44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Velumian AA, Jones OT, et al. Modulation of high-voltage activated calcium channels in dentate granule cells by topiramate. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 1):52–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]