Abstract

Fragment screens for new ligands have had wide success, notwithstanding their constraint to libraries of 1,000–10,000 molecules. Larger libraries would be addressable were molecular docking reliable for fragment screens, but this has not been widely accepted. To investigate docking's ability to prioritize fragments, a library of >137,000 such molecules were docked against the structure of β-lactamase. Forty-eight fragments highly ranked by docking were acquired and tested; 23 had Ki values ranging from 0.7 to 9.2 mM. X-ray crystal structures of the enzyme-bound complexes were determined for 8 of the fragments. For 4, the correspondence between the predicted and experimental structures was high (RMSD between 1.2 and 1.4 Å), whereas for another 2, the fidelity was lower but retained most key interactions (RMSD 2.4–2.6 Å). Two of the 8 fragments adopted very different poses in the active site owing to enzyme conformational changes. The 48% hit rate of the fragment docking compares very favorably with “lead-like” docking and high-throughput screening against the same enzyme. To understand this, we investigated the occurrence of the fragment scaffolds among larger, lead-like molecules. Approximately 1% of commercially available fragments contain these inhibitors whereas only 10−7% of lead-like molecules do. This suggests that many more chemotypes and combinations of chemotypes are present among fragments than are available among lead-like molecules, contributing to the higher hit rates. The ability of docking to prioritize these fragments suggests that the technique can be used to exploit the better chemotype coverage that exists at the fragment level.

Keywords: crystallography, drug design, hit rates, chemical space

Fragment-based screening has recently emerged as an important technique in early drug discovery (1–6). Typically constrained to libraries between 1,000 and 10,000 small molecules, it has nevertheless had hit rates of 5% or higher against many targets. Several of these have resisted ligand discovery by high-throughput screening (HTS), which exploits libraries containing 2–3 orders of magnitude more molecules than those typical for fragments. The high fragment hit rates have been attributed to 2 factors. First, fragments can complement subsites in the pocket without making the structural compromises necessary for larger, multifunctional molecules (7). Second, even a small fragment library typically explores many more chemotypes than is possible for libraries of larger molecules. The possible combinations of chemotypes rises exponentially with the size of the molecule (7), apparently increasing by a log order or more for every atom added in a reasonable size range (8, 9). Thus, one might well be more likely to find a good fragment from among a library of 1 thousand molecules than a good “drug-like” molecule from among a library of 1 million.

Still, the small size of fragment libraries leaves many accessible molecules untested. Even the most high-throughput fragment screen can now only address libraries of 10,000–20,000 compounds, whereas >250,000 fragments are commercially available (10). Although one might cover the 106 commercially available, rule-of-five-compliant (11) compounds with a well-designed library that is one-tenth that size, the collapse in chemical space with molecular size means that leaving out 90–99% of available fragments will leave out approximately the same ratio of chemotypes. Thus, it would be interesting to interrogate much larger compound libraries than are currently feasible for the biophysical assays on which fragment screens now rely.

One method to do so is molecular docking. Docking screens compound libraries for molecules that physically complement protein-binding sites. The technique has been used to discover new ligands in the “lead-like” (typically ≤350 Da) or drug-like ranges (typically ≤500 Da) (12, 13); some of these new ligands have been determined in complex with their targets by crystallography in geometries consistent with the docking predictions (14–17). Docking has also been used to prioritize molecules for fragment-based screens for several targets (5, 18–20). Despite these successes, doubt remains about applying docking to fragments because of possible promiscuous binding modes, the lack of handles to fit fragments into the pocket, and biases in docking scoring functions (21). This skepticism has been buttressed by the lack of structures directly comparing docking fragment predictions with subsequent crystallographic results.

We thus wanted to explore docking as a tool to prioritize fragments using AmpC β-lactamase as a model system. AmpC is well suited to addressing these questions because binding may be measured in a quantitative biochemical assay and biophysically by surface plasmon resonance (SPR), and high-resolution crystal structures can be readily obtained (22). Also, it is a protein that has been targeted by HTS and by docking (17) using the same library, and by docking alone (16). This allows us to compare the docking fragment hit rates with those from HTS and lead-like docking.

Here, we dock a library of 137,639 fragments against the crystal structure of AmpC β-lactamase and investigate the following questions. Can docking reliably prioritize fragments that inhibit in biochemical and biophysical assays? How do the hit rates compare with those from HTS, docking screens of lead-like molecules, or simply sampling fragments at random? What is the role of chemical space coverage in these different hit rates? How diverse are the fragments compared with the inhibitors discovered from the drug-like libraries? Are the docking predictions right for the right reasons—do experimental structures of the fragment inhibitors correspond to the docked poses?

Results

Docking Prioritization of Fragments.

A total of 137,639 compounds from the ZINC database were docked against a crystal structure of AmpC. Two libraries were used for the docking calculations: the first developed by using the definition of fragments proposed by Carr and Rees (23) (47,997 compounds) and a second that removed restrictions on hydrogen bond acceptors and donors (89,642 new compounds plus 27,925 compounds overlapping with the original database). The total elapsed time for the calculation ranged from 5 h (47,997 compounds) to 32 h (117,567 compounds) on a cluster using between 4 (47,997 compounds) and 9 cpus (117,567 compounds). From among the 500 top-scoring molecules from each screen, 48 were purchased and tested in both enzyme and SPR assays (Methods).

Dose–response curves were fit to inhibition numbers to obtain IC50 and Ki values [Table 1, supporting information (SI) Figs.S1A and S2]. Varying substrate and inhibitor concentrations allowed us to construct a Dixon Plot of 2 of the compounds, which confirmed competitive inhibition (Fig. S1B). Of the 48 compounds tested, 23 had Ki values of <10 mM, ranging from 700 μM to 9.2 mM, with ligand efficiencies ranging from 0.16 to 0.47 (Table 1). Three inhibitors, compounds 6, 12, and 13, had ligand efficiencies of 0.29, 0.29, and 0.47 kcal/mol per atom. Dock rankings of the inhibitors ranged from 1 to 373 of 137,639 docked. This gives a 48% hit rate, defined as (number of actives/number of compounds experimentally tested) × 100. SPR experiments were conducted for 4 compounds, and for these biochemical Ki and biophysical Kd values correlated well (Table 1, Fig. S3).

Table 1.

Twenty-three fragment inhibitors identified biochemically and biophysically

| Fragment structure | No. | Rank* | Ki, mM | HAC† | Molecular mass, Da | LE‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 270§ | 2.0 | 17 | 236 | 0.21 | |

| 2 | 139§ | 1.0 | 17 | 236 | 0.24 | |

| 3 | 274§ | 3.0 | 14 | 193 | 0.24 | |

| 4 | 89§ | 2.0 | 18 | 248 | 0.20 | |

| 5 | 210§ | 6.7 | 18 | 246 | 0.16 | |

| 6 | 52§ | 1.8 | 13 | 200 | 0.29 | |

| 7 | 76§ | 3.5 | 17 | 234 | 0.20 | |

| 8 | 47§ | 2.6 | 16 | 220 | 0.20 | |

| 9 | 18§ | 0.7 | 18 | 244 | 0.24 | |

| 10 | 159§ | 2.2 | 17 | 232 | 0.21 | |

| 11 | 193§ | 6.0 | 13 | 219 | 0.23 | |

| 12 | 149§ | 1.0 | 14 | 188 | 0.29 | |

| 13 | 1¶ | 2.7 | 8 | 138 | 0.47 | |

| 14 | 15¶ | 1.7/3.9‖ | 16 | 239 | 0.25 | |

| 15 | 373¶ | 7.0 | 15 | 227 | 0.20 | |

| 16 | 22¶ | 7.1 | 16 | 215 | 0.18 | |

| 17 | 34¶ | 3.2 | 15 | 238 | 0.23 | |

| 18 | 27¶ | 7.7/21.0‖ | 16 | 217 | 0.18 | |

| 19 | 87¶ | 2.0/6.8‖ | 14 | 227 | 0.26 | |

| 20 | 159¶ | 4.5 | 15 | 226 | 0.21 | |

| 21 | 162¶ | 7.5 | 12 | 185 | 0.24 | |

| 22 | 48¶ | 4.9/18.0‖ | 12 | 185 | 0.26 | |

| 23 | 39¶ | 9.2 | 16 | 237 | 0.17 |

*Docking rank.

† Heavy atom count —defined as the number of nonhydrogen atoms.

‡(kcal/mol) per atom.

§Ranking based on docking of 117,567 compounds.

‖ Ki values calculated from SPR assays.

¶Ranking based on docking of 47,997 compounds.

To ensure that the high hit rate observed was not an artifact of screening at a high concentration, we tested a set of fragments chosen at random from the library. Of 20 random fragments tested, 1 inhibited detectably with a Ki of 3.1 mM. As it happened, this 1 random hit also scored well by docking (rank = 2,223, docking score = −60.3 kcal/mol), ranking among the top 5% of all molecules docked.

Similarity analysis was performed to measure the diversity of the 23 fragment hits relative to each other and relative to that of 21 known lead-like inhibitors of AmpC (Fig. S4) (16, 17). By using FCFP_4 fingerprints (SciTegic Inc. and Accelrys Inc.) generated with Pipeline Pilot, the average pairwise Tanimoto coefficient within the fragment set was 0.22, and the lowest and highest Tanimoto coefficients were 0.13 and 0.26. Conversely, similarity coefficients within the lead-like sulfonamides and pthalimides previously discovered for AmpC (16, 17) fell between 0.21 and 0.55, with an average value of 0.43. Comparing the similarity between the 2 sets (i.e., fragments vs. lead-like), the minimum Tanimoto coefficient was 0.16, the maximum was 0.23, and the mean value was 0.19. Thus, the known lead-like inhibitors are internally less diverse than the fragments, and the fragments are structurally distinct from the known inhibitors.

Comparing the Docking Predicted Pose to the Crystal Structure.

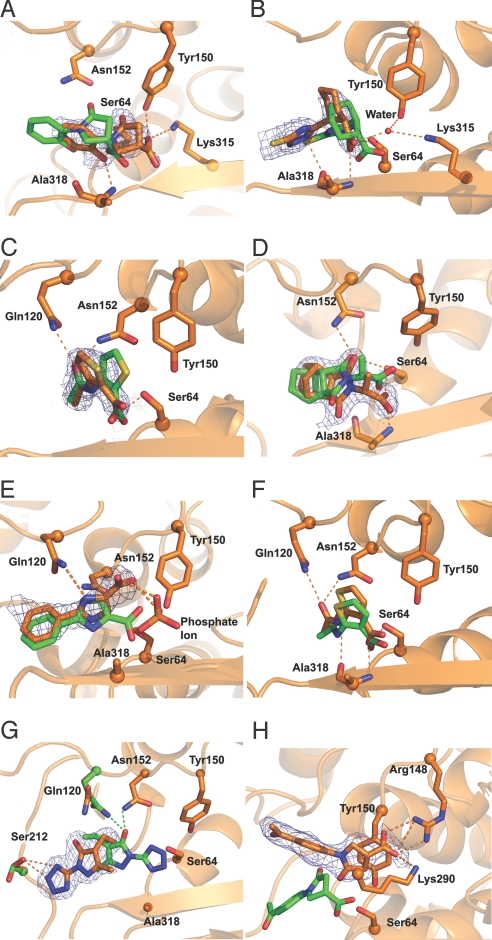

Of the 23 active fragments, 8 crystal structures were determined with resolutions from 1.5 Å to 2.5 Å (Table S1). The location of the inhibitors was unambiguous in the final 2Fo-Fc electron density map (Fig. 1 A–E, G, and H). Fragment 22 (Fig. 1F) was previously crystallized (24). To evaluate accuracy, the structure predicted by docking, directly from the initial calculation and without further refinement, was overlaid by using protein backbone and ligand atoms onto the crystallographic conformation. RMSD values were then calculated by using ligand atoms only. For fragments 21, 12, 1, and 22, the docking predictions corresponded closely to the X-ray results, with RMSD values of 1.2, 1.6, 1.4, and 1.3 Å, respectively (Fig. 1 C–F). For compounds 8 and 20, the RMSD values were 2.5 and 2.6 Å, making the correspondence substantially worse. Even here, both crystal structures retain most of the contacts with the catalytic residues predicted in the docking pose (Fig. 1 A and B). For fragment 8, the crystallographic orientation differs mainly by a translational shift. We note that this fragment had 2 configurations in the electron density, both modeled at 50% occupancy; here, we consider only that one closest to the docking prediction. For compound 20, the “warhead” carboxylate group interacts with both the catalytic serine and the oxyanion hole, as predicted in the docked pose (Fig. 1B). The only substantial change is in the position of the triazole group, which results from favorable van der Waals interactions between the cyclohexyl ring and the protein.

Fig. 1.

Overlay of docked pose (green) and crystallographic pose (orange) for 8 of the fragment inhibitors prioritized by docking. The compounds shown are: 8 (A), 20 (B), 21 (C), 1 (D), 12 (E), 22 (F), 3 (G), and 5 (H). The final 2Fo-Fc maps contoured at 1σ are shown for A–E, G, and H. Compound 22, although discovered as part of the docking screen described here, was reported previously and no density is shown for it (24).

In all these AmpC-fragment crystal structures, with 2 exceptions noted below, we typically observe hydrogen bonds between the ligand and the following residues: the catalytic Ser-64, one or both of the oxyanion hole nitrogens from Ala-318 and Ser-64, and hydrogen bonds mediated by Gln-120 and Asn-152. The ligands also consistently form van der Waals contacts with Tyr-150 (Fig. 1 A–H). These interactions are normally conserved in the docking pose. In the case of compound 12, the warhead carboxylate group is swung away from the catalytic serine, inconsistent with the prediction. However, this may be a crystallographic artifact caused by the high concentration of phosphate (1.7 M) present in the crystallizing buffer, leading to interference by a phosphate ion that binds in the active site (Fig. 1E).

Whereas most of the docked poses corresponded to the crystallographic structures, the complexes with compounds 5 and 3 disagreed with the docking predictions. This failure results from changes in the protein conformation in the holo forms. In complex with 3, Gln-120 swings away from the binding pocket and instead of hydrogen bonding with the fragment hydroxyl, it interacts with a water molecule (Fig. 1G). Additionally, Ser-212 rotates into the pocket, stabilizing the crystal pose through a hydrogen bond with the tetrazole nitrogen of compound 3 (Fig. 1G).

Much greater protein flexibility is observed in the crystal structure of the AmpC/5 complex. Here, the helix formed by residues 275–295 unwinds to accommodate the ligand. This reveals a cryptic binding pocket hidden in the apo structure against which we docked. This new site is stabilized by a salt bridge between the ligand carboxylate and Arg-148, π–π stacking interactions with Tyr-150, and by hydrogen bonds with Lys-290, which swings in toward the pocket (Fig. 1H and Fig. S5). Compound 5 seems to well complement this cryptic site: in the crystallographic geometry, the DOCK score is −80.1 kcal/mol, which would have put it as the top-ranking compound from the entire fragment screen. Admittedly, this score does not account for the protein reorganization necessary to form this site. Still, this site has been observed previously with 2 different fragment inhibitors of AmpC (24) and may merit further evaluation.

Chemical Space Analysis.

Many of the 23 fragment inhibitors represent chemotypes not previously seen among larger inhibitors of AmpC. We wondered whether these had been simply missed from the previous HTS and docking screens or whether they were genuinely absent among larger molecules. To investigate this, a substructure search was conducted against 2 libraries: that of the 10 million commercially available compounds in ZINC (10) and that of the 70,563 compounds from the Molecular Libraries-Small Molecule Repository (MLSMR) used in the previous HTS against AmpC (17). We looked for lead-like molecules (defined as heavy atom count, HAC, ≤25) that contained any of the 23 fragments and maintained their key warhead groups (e.g., we did not allow key carboxylates to be derivitized to esters) (Fig. 2A). This found 675 larger lead-like molecules from ZINC and 14 from the MLSMR, from which several of the lead-like inhibitors had been originally found. We then asked how many lead-like molecules containing these fragments might be possible. For a pool of side chains with which to elaborate the 23 fragment inhibitors, we drew from the precalculated generated database (GDB) of molecules, a theoretical library that contains all possible “stable” compounds up to 11 heavy atoms composed of C, O, N, and F, as well as hydrogens (8). We split the GDB into 11 sets by HAC (i = 1–11), such that each set contains mi potential decorations, taking into consideration that a given GDB molecule can be attached to our fragment at multiple points (Fig. 2B). We calculated all of the ways to add these side chains to the fragments through up to k attachment points without exceeding 25 HAC. These criteria are filled by each unique combination of q1, q2, q3,….q11 values that simultaneously satisfies the following 2 equations:

|

and

|

Fig. 2.

Illustration of fragment substructures and their expansions with side chains. (A) The fragment (red, Left) is a substructure of the larger lead-like compound (Right). (B) The number of attachment points on the fragment scaffold (A1 to A7) and on the example side chain (A1) was determined by generating smiles strings of each and identifying the number of hydrogen atoms. Each decoration was allowed only 1 attachment point at a time (excluding ring closing within the fragment). The possible number of lead-like expansions (≤25 HAC) that could be formed by combining each decoration to attachment points on the 23 fragment scaffolds was calculated analytically by using Eq. 3. (C) Structures of the different kinds of symmetry elements seen in the fragments. In each case, the symmetrical attachment points (e.g., A1 and A2, C1, C2, and C3) were collapsed into a single attachment point (e.g., A1 and A2 count as only 1 attachment point). These provided a lower limit for the possible number of compounds that contain the fragments as substructures. The upper limit is calculated by assuming each attachment point is unique (no symmetry).

These equations must be simultaneously satisfied to determine which sets of decorations can be added to the fragment and still remain <25 HAC. fHAC is the HAC of the fragment scaffold, qi are the number of times the HAC set of size i is attached, and n is the total number of attachment points on the scaffold.

We then determined the number of molecules containing the fragment for each of these unique combinations of qi (Eq. 3):

|

Where n is the total number of attachment points on the scaffold, mi is the number of decorations in the pool of size i, and qi is the number of times the HAC set of size i is attached.

We applied this 2-step procedure to each of the 23 fragments and summed the results to calculate the total number of possible expansions of all of the inhibitors.

To make this calculation feasible we set several boundary conditions. First, we restricted the size of the lead-like molecule grown from our initial fragment hits to 25 atoms. Thus, for a fragment of 15 HAC, the maximum number of new heavy atoms to add was 10. The second restriction in the calculation was that the identified attachment points on the scaffold were unique and did not contain any symmetry elements (Fig. 2B). Thus, addition of side chains onto the different attachment points did not produce duplicate compounds. Because many of the fragments inhibiting AmpC have symmetrical attachment points, a lower and upper limit was calculated. The lower limit was obtained by grouping symmetrical attachment points together and counting them only once (Fig. 2C). The upper limit was calculated by assuming each attachment point is unique (no symmetry). A third constraint was that neither ring systems involving the core fragment itself nor multiple valence bonds between the fragment and the side chain were considered.

Within these constraints, between 4.7 × 1010 and 4.3 × 1011 molecules were calculated containing the 23 fragments. Thus, comparing the 675 lead-like molecules that are available with the ≈1011 that are possible leaves only 1/108 of possibilites explored at the lead-like level. Meanwhile, the same calculation for fragments (assuming a limit of 17 HAC) finds 104 molecules that could contain our actives as substructures, 93 of which are commercially available, giving 1/102 coverage, 106-fold better, at least for these particular molecules, than at the lead-like level.

Discussion

Returning to our initial questions, 3 principal observations emerge from this study. Judged by hit rate, the chemical diversity of the hits, and the fidelity of the docking predictions to the subsequent crystallographic results, molecular docking can prioritize new fragment inhibitors for β-lactamase. The most important contribution to this high hit rate is the better coverage of chemotypes at the fragment level of molecular complexity than at the lead-like or drug-like levels. Most of the chemotypes explored are underrepresented by a factor of no less than 106-fold among available lead-like molecules compared with their coverage at a fragment level.

A motivation for this study was to access fragments that are commercially available but too numerous to be screened empirically. Whereas docking has been used successfully to prioritize fragments (5, 18, 19), its reliability has been questioned (21). The 48% hit rate for AmpC supports the feasibility of prioritization from this large library. Because AmpC has been targeted by multiple approaches, this fragment hit rate may be quantitatively compared with others. In an HTS campaign of >70,000 drug-like molecules against AmpC, the only inhibitors discovered were covalent-acting β-lactams—no reversible, competitive inhibitors were found—making the hit rate effectively 0% (17). For a docking screen of the same library, using the same docking program as deployed here (DOCK3.5.54), essentially 1 new chemotype was found, making for a docking hit rate of 7%. In another docking screen of drug-like molecules against AmpC, 1 midmicromolar inhibitor was discovered of 54 tested, a hit rate of 2%. Thus, the fragment hit rate is high for this target compared with both computational and experimental screening of libraries of larger molecules. The role of docking in enriching these inhibitors is supported by the dearth of inhibitors from a random sample of 20 fragments.

Perhaps the most compelling support for the docking prioritization, however, comes from the high fidelity of the docking poses to the subsequent X-ray crystallographic results. Of the 8 structures determined, 4 had good pose fidelity, with RMSDs ranging from 1.2 to 1.6 Å. Another 2, with RMSD values of 2.5 and 2.6 Å, were further displaced but nevertheless contacted many of the predicted residues. Previous studies have discussed the difficulty of docking fragments because of problems with empirically based scoring functions that have been optimized by using larger compounds (21). For all its weaknesses, the crude physics-based scoring function used here (DOCK3.5.54) can prioritize actives from a database of 137,639 compounds and can often do so for the right reasons.

Several caveats merit consideration. Whereas many of the docking predictions corresponded closely to the subsequent X-ray structures—arguably at a better rate than one might expect from docking more classical compounds—there were 2 cases where the binding poses were wrong. In these structures, protein conformational changes occurred, something that could not have been anticipated by the rigid protein docking conducted here. Predicting protein accommodations in docking remains an active area of research (25). Despite the high (48%) hit rate, most of the active fragments have modest ligand efficiencies. This may reflect the challenging nature of the AmpC binding site, which is large and fairly open. On the other hand, by docking against the catalytic site of AmpC, we may have unintentionally favored anionic inhibitors that could complement the enzyme's oxyanion hole. This favored compounds that were charged and thus unusually soluble (typically up to 10 mM). Lower hit rates in other studies may reflect limitations in solubility of less polar fragments. Finally, our quantification of chemical space coverage can only be taken as a lower bound owing to the restrictions placed on the chemotypes we added to the fragments.

Notwithstanding these approximations, chemotype representation at different molecular mass had an enormous effect. A clue to this is the greater diversity of the fragments compared with all previously known noncovalent inhibitors of AmpC; among the fragments are found chemotypes never seen before for this target. Such absences of evidence are rarely convincing in themselves, but here, they can be attributed to systematic absences of the fragment cores among the larger, lead-like molecules. Only 675 lead-like molecules of the 1 million commercially available in ZINC contain any of the 23 fragment inhibitors as substructures, and most of these contained compounds 6 and 22. Meanwhile, no less than 1010 to 1011 such lead-like superset molecules are possible. Returning to Eq. 1, one can show that there are 104 possible other fragments, calculated as molecules up to 17 HAC, that contain the cores of these 23 inhibitors, of which 93 are commercially available. The coverage of this area of chemical space is orders of magnitude better at the fragment level than at even the lead-like level; the 23 fragments are present in 93 of 104 or 1% of commercially available fragments, but only 675 of 1011, or 10−6% of commercially available lead-like molecules. This will be true for most molecules, the only partial exceptions being those for which there is bias in the library, such as aminergic GPCR ligands (26, 27). Said another way, the chances of discovering interesting chemotypes for biological targets is many orders of magnitude higher when targeting molecules in the fragment weight range than even at slightly higher size ranges. These points have been made by others, and have been modeled by Hann and colleagues (7). The contribution of this work is to reduce general principles and models to specific quantification for a particular series of chemotypes actually found to inhibit an enzyme, and to show how structure-based docking can prioritize molecules from among a large set of available fragments that would be inaccessible by empirical approaches alone.

Materials and Methods

Docking.

Fragment-like molecules from the ZINC database (10) were docked into an apo AmpC structure (PDB ID code 1KE4) (28) by using DOCK3.5.54. Two screens of the ZINC fragments were conducted: once when the library contained 50,000 fragments and again after it had expanded to 137,000 fragments. For the first screen, compounds were filtered for the following properties: 150 ≤ molecular mass ≤250Da, −2 ≤ ClogP ≤3, number of rotatable bonds ≤3, number of H-bond donors ≤2, and acceptors ≤ 4. In the second screen, the restrictions on rotatable bonds and hydrogen bonding were removed. To prepare the protein-binding site, all water and ion molecules were removed except for Wat403 (in the first screen), and Wat466 and Wat565 (in the second) (SI Text).

For the docking calculations themselves, a sphere set was constructed based on 13 ligand-bound X-ray structures (17); these spheres determine how ligand orientations in the active site are calculated. Ligand–protein fit was calculated based van der Waals and electrostatic complementarity between enzyme and ligand, corrected for ligand desolvation (see SI Text). After docking, the 500 top-ranking poses were visually inspected. In addition to simple rank, which for 137,000 compounds must be the primary criterion, compounds were prioritized for contacts to key catalytic residues (e.g., Ser-64 and the oxyanion hole), chemotype novelty, and commercial availability. This is our common practice in prosecuting docking screens, and these criteria are consistent with previous studies. Forty-eight high-scoring docking compounds were purchased and tested experimentally, as were 20 fragments selected at random (SI Text).

Absorbance and SPR Assays.

For information on absorbance and SPR assays, see SI Text.

Ligand Similarity and Substructure Search.

For information on ligand similarity and substructure search, See SI Text.

Crystallography.

All AmpC/fragment structures were based on cocrystalization and structures determined by molecular replacement (see SI Text).

Theoretical Number of Lead-Like Compounds.

Eq. 1 was used to determine how many lead-like compounds should theoretically contain the 23 active fragments as substructures. The GDB was used as a source of side chains to add to fragment scaffolds (8). Multiple boundary conditions were set to make the calculation feasible (see Results).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Yu Chen, Jerome Hert, Pascal Wassam, and Peter Kolb for discussions and assistance with chemoinformatics and Michael Mysinger, Sarah Boyce, and Yu Chen for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM59957 and GM63813.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (RCSB ID codes 3GVB, 3GV9, 3GRJ, 3GR2, 3GTC, 3GQZ, 3GSG).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0813029106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Allen KN, et al . An experimental approach to mapping the binding surfaces of crystalline proteins. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:2605–2611. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringe D, Mattos C. Analysis of the binding surfaces of proteins. Med Res Rev. 1999;19:321–331. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199907)19:4<321::aid-med5>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mattos C, Ringe D. Locating and characterizing binding sites on proteins. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt0596-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdonk ML, Hartshorn MJ. Structure-guided fragment screening for lead discovery. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev. 2004;7:404–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubbard RE, Davis B, Chen I, Drysdale MJ. The SeeDs approach: Integrating fragments into drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1568–1581. doi: 10.2174/156802607782341109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verlinde CL, Rudenko G, Hol WG. In search of new lead compounds for trypanosomiasis drug design: A protein structure-based linked-fragment approach. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 1992;6:131–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00129424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hann MM, Leach AR, Harper G. Molecular complexity and its impact on the probability of finding leads for drug discovery. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41:856–864. doi: 10.1021/ci000403i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink T, Reymond JL. Virtual exploration of the chemical universe. J Chem Inf Model. 2007;47:342–353. doi: 10.1021/ci600423u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wester MJ, et al. Scaffold topologies. 2. Analysis of chemical databases. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:1311–1324. doi: 10.1021/ci700342h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. ZINC—A free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model. 2005;45:177–182. doi: 10.1021/ci049714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oprea TI, Davis AM, Teague SJ, Leeson PD. Is there a difference between leads and drugs? A historical perspective. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41:1308–1315. doi: 10.1021/ci010366a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellenberger E, et al. Identification of nonpeptide CCR5 receptor agonists by structure-based virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2007;50:1294–1303. doi: 10.1021/jm061389p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenk R, et al. Virtual screening for submicromolar leads of tRNA-guanine transglycosylase based on a new unexpected binding mode detected by crystal structure analysis. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1133–1143. doi: 10.1021/jm0209937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenfeld RJ, et al. Automated docking of ligands to an artificial active site: Augmenting crystallographic analysis with computer modeling. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2003;17:525–536. doi: 10.1023/b:jcam.0000004604.87558.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers RA, Morandi F, Shoichet BK. Structure-based discovery of a novel, noncovalent inhibitor of AmpC beta-lactamase. Structure (London) 2002;10:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00799-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babaoglu K, et al. Comprehensive mechanistic analysis of hits from high-throughput and docking screens against beta-lactamase. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2502–2511. doi: 10.1021/jm701500e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warner SL, et al. Identification of a lead small-molecule inhibitor of the Aurora kinases by using a structure-assisted, fragment-based approach. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1764–1773. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang D, et al. Discovery of cell-permeable non-peptide inhibitors of beta-secretase by high-throughput docking and continuum electrostatics calculations. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5108–5111. doi: 10.1021/jm050499d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyatt PG, et al. et al. Identification of N-(4-piperidinyl)-4-(2,6-dichlorobenzoylamino)-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide (AT7519), a novel cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor using fragment-based X-ray crystallography and structure based drug design. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4986–4999. doi: 10.1021/jm800382h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubbard RE, Chen I, Davis B. Informatics and modeling challenges in fragment-based drug discovery. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. 2007;10:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Minasov G, Roth TA, Prati F, Shoichet BK. The deacylation mechanism of AmpC beta-lactamase at ultrahigh resolution. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2970–2976. doi: 10.1021/ja056806m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carr RA, Congreve M, Murray CW, Rees DC. Fragment-based lead discovery: Leads by design. Drug Discovery Today. 2005;10:987–992. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babaoglu K, Shoichet BK. Deconstructing fragment-based inhibitor discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:720–723. doi: 10.1038/nchembio831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kramer B, Rarey M, Lengauer T. Evaluation of the FLEXX incremental construction algorithm for protein-ligand docking. Proteins. 1999;37:228–241. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19991101)37:2<228::aid-prot8>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowrie JF, Delisle RK, Hobbs DW, Diller DJ. The different strategies for designing GPCR and kinase targeted libraries. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2004;7:495–510. doi: 10.2174/1386207043328625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds CH, et al. Diversity and coverage of structural sublibraries selected using the SAGE and SCA algorithms. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41:1470–1477. doi: 10.1021/ci010041u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers RA, Shoichet BK. Structure-based approach for binding site identification on AmpC beta-lactamase. J Med Chem. 2002;45:3222–3234. doi: 10.1021/jm020002p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.