Abstract

The epidemiology of acute pyelonephritis (APN) has changed with time. Therefore we investigated the current clinical characteristics of APN and the significance of proper surgical management for treatment of 1,026 APN patients in South Korea for the past 5 yr. The male-to-female ratio was about 1:8. The peak ages of female patients were 20s (21.3%) and over 60s (23.7%), while that of male was over 60s (38.1%). The occurrence of sepsis was 10.1%. Complicated APN patients were 35.4%. Ninety-four patients (9.2%) needed urological procedures. The duration of the flank pain and of the costovertebral angle tenderness in complicated APN patients was statistically significantly longer than that with simple APN patients (4.3 vs. 3.4 days, 4.4 vs. 4.0 days). If flank pain and costovertebral angle tenderness sustain over 4 days, proper radiologic studies should be performed immediately with the consideration of surgical procedure. Also the resistance to antibiotics was increasing. As the sensitivities to ampicillin (27.2%) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (44.7%) of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae were very low, it is necessary to take the careful choice of antibiotics into consideration.

Keywords: Urinary Tract Infections, Pyelonephritis, Urologic Surgical Procedures

INTRODUCTION

Acute pyelonephritis (APN) is a serious form of urinary tract infection (UTI). Its annual incidence is 250,000 cases in the US and the incidence of hospitalized APN is 11.7 cases per 10,000 population among females and 2.4 cases per 10,000 population among males (1). While in Korea, the incidence rate is 35.7 cases per 10,000 population (2). Clinical manifestations include severe systemic symptoms such as high fever, chilling, nausea and vomiting. Without proper treatments, the renal pelvis and its parenchyme can be damaged, possible following sepsis that may lead to death. In the cases with associated sepsis, the mortality reaches 10-20% (3, 4). In Korea, the high mortality (2.1 cases per 1,000 persons among hospitalized patients) has been reported (2).

Key consideration in the treatment of APN is to understand the current characteristics of the current community, causative bacterial spectrum, and antibiotic resistance patterns. Antibiotic resistance is on the gradual increase, and ampicillin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) that have been the first-line antibiotics could not show effective sensitivity any longer (5). And at the early phase of the treatment for APN when the isolation of causative microorganisms is not performed yet, antibiotics should be administered empirically. It is required to understand accurately the presently most frequent causative microorganisms and antibiotic resistance. In addition, as the westernized life style and eating habit are accelerating prevalence of diabetes and other chronic diseases as well as Korean society is getting more aged, the alteration of the epidemiology of APN is anticipated, with its epidemic examination at regular basis.

The cases with underlying causes are referred to as complicated APN, and its proportion is 21.1-37.8% (1-4). Although APN could be treated readily with appropriate antibiotics, hydration, and bed rest, complicated APN should be done with correcting its cause. Moreover, it has been reported that complicated APN shows high positive rate with blood culture and more sever clinical symptoms than those of simple APN (5, 6).

Therefore, we examined the current clinical characteristics and the necessity of surgical treatment in 1,026 cases of APN patients for the past 5 yr.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

On 1,026 patients who were admitted to Kyung Hee University Medical Center under the diagnosis of APN from January 2000 to December 2004, we retrospectively examined clinical symptoms, causes, causative microorganisms, antibiotic sensitivities, and curative urological procedures by reviewing their medical records.

In addition to the clinical diagnosis, patients were required to meet more than 3 of the following 5 criteria: 1) clinical symptoms of APN (chilling, nausea, vomiting, flank pain); 2) costovertebral angle tenderness; 3) leukocytosis (higher than 10,000/µL); 4) fever (higher than 38.5℃); 5) white blood cell (WBC) count ≥5 cells per high-power field on centrifuged urine sediment or more 100,000 CFU/mL microorgarnisms in urine culture (7).

Infected site (right, left, and both) was localized with clinical symptoms such as flank pain and costovertebral angle tenderness. In cases which clinical symptoms were vague, we judged the localization by radiologic findings.

The urine collecting methods for males were that lift the prepuce, wash the urethral meatus with 2% boric sponge, and collect the mid stream urine in a sterile plastic cup with a lid, and in female cases, in the lithotomy position, wash the perineum and the urethral meatus by the identical method, and collect the mid stream urine was using a nelaton catheter.

The collected urine was inoculated to blood agar broth and MacConkey broth, 0.001 mL each, cultured in a 37℃ incubator for 24 hr, and the number of bacterial colony per 1 mL urine was calculated. The blood was also inoculated to blood agar broth and MacConkey broth, cultured for 5 days, and the growth of bacteria was assessed.

The identification of bacteria and antibiotic sensitivity were assessed by the disk diffusion test described by the National Commitee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Clinical symptoms, sign, and the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms were assessed, and the duration of the fever higher than 38.5℃, the duration of the flank pain, and the duration of the costovertebral angle tenderness were assessed.

To diagnosis complicated APN, we examined the presence of following diseases: structural and functional abnormalities (urinary tract stone disease, neurogenic bladder, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), obstructive uropathy, prostate disease); urologic manipulation (cystoscopic or ureteroscopic examination, indwelling catheter, kindey transplantation); the underlying diseases which contribute to the persistence of infection or suppression of immune system (diabetes, immunosuppressive state, cystic renal disease).

As statistics, comparison of continuous variables between independent two groups was performed by t-test, comparison of the frequency was analyzed by Pearson chi-square test, and the criterion of the determination of significance was p<0.05.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Among total 1,026 cases, male was 118 cases, female were 908 cases, and the ratio of male to female was 1:7.7. The mean age was 45.5±17.8 yr, male was 49.0±19.2 yr, female was 45.0±17.5 yr, and a difference between genders was not detected (p>0.05). In males, group of over 60 was 38.1%, which was the most prevalent age group, and in females, groups of 20s and over 60s was 21.3% and 23.7%, respectively, which were most prevalent. Particularly, females in their 20s and 30s were 38.6% of the entire female patients.

Clinical presentation

In regard to the invaded sites, the right kidney was 56.3%, the left kidney was 32.9%, both kidneys was 10.7%, and a statistic difference between gender was not detected. The duration of fever, the duration of the flank pain, and the duration of the costovertebral angle tenderness was 3.1 days, 3.7 days, and 4.2 days, respectively.

Complicating factors

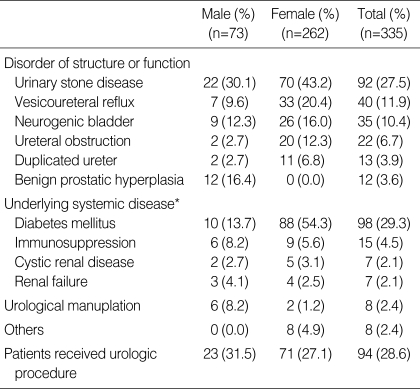

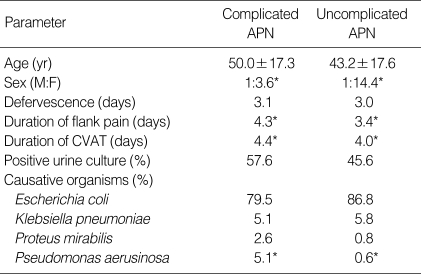

32.7% of total APN (335 cases, 73 men, 262 women) were complicated APN. Also 61.9% of total men and 28.9% of total women were complicated APN, respectively. Among the complicated APN, the cases with structural and functional abnormality were 214 patients (63.9%), the cases with underlying medical diseases were 106 patients (37.9%), and the cases caused by the urologic manipulation were 8 cases (2.4%). As a single disease, diabetes mellitus (DM) was for 98 cases (29.3%), which was most prevalent, followed by the order of urolithiasis, vesicoureteral reflux, neurogenic bladder, immunosuppressive state, duplicated ureter, ureteral stricture, and so on. Particularly, in the entire male patients, the portion of complicated APN was 61.9%, and the causality was in the order of urolithiasis, benign prostate hyperplasia, DM, and neurogenic bladder (Table 1). In complicated APN, the duration of the flank pain and the costovertebral angle tenderness was statistically significantly longer than in simple APN and the portion of male against female (F:M=1:3.6) was higher than that of simple APN (1:1.14). However, age, duration of fever, and urine culture positive rate between genders were not different, respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Underlying disease of complicated acute pyelonephritis

*, Those patients can also have other disease.

Table 2.

Comparison between the clinical features of complicated and uncomplicated APN

Comparison between complicated APN and uncomplicated APN (*p<0.05).

APN, acute pyelonephritis; CVAT, costovertebral angle tenderness.

Radiologic findings

Abdominopelvis ultrasonography was performed on 788 cases (76.8%), and among them, 428 cases (54.3%) showed normal findings, and in the cases showing abnormalities, the abnormal findings were detected in the order of nephromegaly (18.8%), hydronephrosis (12.1%), renal stone (4.2%), renal cyst (2.9%), and ureter stone (2.1%).

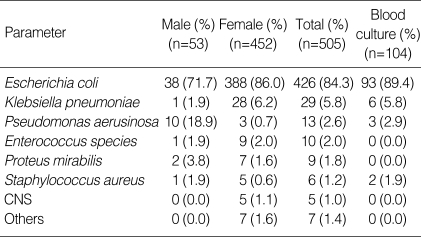

Bacterial culture and antibiotic sensitivity

The cases that bacteria were isolated by urine culture were 504 patients (49.1%) and the positive culture rate in males and females was 44.9% and 49.7%, respectively. In regard to isolated bacteria, Escherichia coli was 84.3%, which was most prevalent, followed by the order of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aerusinosa, Enterococcus species, Proteus mirabilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Coagulase negative Staphylococcus. In both males and females, E. coli was the major causative bacteria (71.7% vs. 86.0%), and the portion of Pseudomonas aerusinosa was higher in males than in females (18.9% vs. 0.7%) (Table 3). The cases that bacteria were isolated by blood culture were 104 patients, which was 10.1% of the entire patients. Similarly, E. coli was detected to be high, 89.4%, followed by the order of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aerusinosa, and Staphylococcus aureus (Table 3). But each infection has no difference against the rate of sepsis in this study. In the cases that microorganisms were isolated in the blood culture, the duration of the flank pain was significantly longer than negative cases (4.67 days vs. 3.67 days) (p<0.05). None of the duration of fever, the duration of the flank pain, the duration of the costovertebral angle tenderness according to the isolated microorganisms were statistically different (p>0.05).

Table 3.

APN, acute pyelonephritis; CVAT, costovertebral angle tenderness.

CNS, coagulase negative staphylococcus.

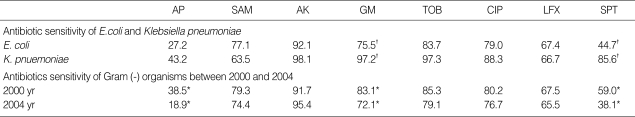

The antibiotic sensitivity test of E. coli were 27.2%, 77.1%, 92.1%, 77.1%, 83.7%, 79.0%, 67.4%, and 44.7% to ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxcin, and TMP/SMX each. On the other hand, the mean rates of sensitivity of K. pneumonia were 43.2%, 63.5%, 98.1%, 97.2%, 97.3%, 88.3%, 66.7%, and 85.6% to ampicillin, ampicillin/sulbactam, amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxcin, and TMP/SMX. In comparison with E. coli, K. pneumoniae was found to be more susceptible to TMP/SMX and gentamicin (p<0.05).

Reviewing the change of the antibiotic sensitivity of Gram negitive bacteria from 2000 to 2004 yr, all the sensitivity to ampicillin, gentamicin, and TMP/SMX were statistically significantly reduced (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibiotic sensitivity (%)

Comparison between E. coli and K. Pnuemoniase (†p<0.05). Comparison between 2000 and 2004 yr (*p<0.05).

AP, ampicillin; SAM, ampicillin/sulbactam; GM, gentamycin; AK, amikacin; TOB, tobramycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LFX, levofloxcin; SPT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Curative urological procedures for complicated APN

For the treatment of complicated APN, urological procedures were performed on 94 cases (9.2% of the entire APN patients). Among them, the most frequent procedure was urinary lithotripsy (42 cases, 44.7%) that consisted of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) (33 cases, 35.1%), ureteoscopic stone removal (7 cases, 7.4%) and ureterolithotomy (2 cases, 2.1%). And other procedures were followed in the order of percutaneous nephrostomy (23 cases, 24.5%), clean intermittent catheterization (14 cases, 14.9%), ureteroneocystostomy (10 cases, 10.6%), nephrectomy (5 cases, 5.3%) and percutaneous pus drainage (3 cases, 3.2%). Among the cases performed percutaneous nephrostomy, 3 cases were also performed other stone removal procedures. Among nephrectomy cases, 4 cases were nonfunctioning atrophic kidney, and the other was emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN).

DISCUSSION

UTI is bacterial infection that can be encountered frequently in clinics, and APN is the most severe form of UTI. Depending on reports, the ratio of male to female varies from 1:7 to 1:13.1 (8-10), and in our study, similarly, it was 1:7.7, and found to be substantially more prevalent in females. In females, the prevalent ages were shown to be the 20s and 30s (38.6% in our study), which is in agreement with other Korean reports that it was prevalent in childbearing ages (8-10). Numerous studies have been reported that in young women who are sexually active, and using a diaphragm or spermicide recurrent UTI could occurs (11). In addition, in our study, the proportion of female cases older than 60 yr is 23.7%, which is higher than previous studies reported in Korea. It is thought that the increase of the diseases such as DM and cerebral vascular disease due to the aging society and the westernization of eating habit contributed to occurrence of UTI.

In our study, the cases that bacteria had been isolated in urine culture were found to be 505 patients (49.1%), which is similar to the proportion of 53.4% reported by Sohn et al in the 1990s (8). It is considered that the reasons of low rates of the positive culture rate in such manners are that many patients have taken antibiotics without prescription and while being treated at private clinics previously, with antibiotics as well.

As for causative microorganisms, E. coli accounted for 84.3%, and in agreement with previous reports, which turned out markedly prevalent (8-10). Among isolated microorganisms, the important point to which attentions have to be paid is that only in the cases with risk factors such as neurogenic bladder, kidney transplantation, urethral stricture, Pseudomonas was cultured, and males were 80%, which was prevalent.

In our study, the antibiotic sensitivity test for ampicillin to E. coli to was 27.7%, while 77.1% for ampicillin/sulbactam, 79.0% for ciprofloxacin, 44.7% for TMP/SMX, 92.1% for amikacin, and 77.1% for gentamicin 77.1%. In other countries, it has been reported that antibiotic sensitivity for TMP/SMX was 67-83.2%, 78-98.1% for ciprofloxacin and 25-82.3% for ampicillin (12-14). In Korea, according to Min et. Al. they have reported that antibiotic sensitivity for ampicillin was 13.2%, to TMP/SMX 44.7%, to ciprofloxacin 86.5%, and to amikacin 98.3% (10). According to our study and previous studies reported in Korea, we found that the antibiotic resistance of ampicillin and TMP/SMX is higher than that of western countries.

Sepsis is a lethal sequela to APN patients, it has been reported to be associated in approximately 7.4-22.6% (8), and in our study, and it was shown to be 10.1%. In the cases awwociated with sepsis, high mortaility and seve clinical symptoms were accompanied (3, 4). In our study, similarly, in the cases that bacteria were isolated in blood culture, the duration of flank pain was significantly longer than other cases.

In mild APN, Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends an oral fluoroquinolone for empirical therapy. If the organism is known to be susceptible, oral TMP/SMX provides an alternative (15). If a patient at the time of presentation is sufficiently ill to require hospitalization (high fever, high white blood cell count, vomiting, dehydration, or evidence of sepsis) or fails to improve during an initial outpatient treatment period, intravenous fluoroquinolone, an aminoglycoside with or without ampicillin, or an extendedspectrum cephalosporin with or without an aminoglycoside are recommended (15). Concerning the duration of treatment, the regimen of intravenous injection for 7 days and subsequently oral administration for 1 week or 2 weeks are recommended (16). In addition, Talan et al. (17) recommended the regimen of oral fluoroquinolone for 7 days or TMP/SMX for 14 days. They also reported that bacteriologic cure rates were 99% for the ciprofloxacin regimen and 89% for the TMP/SMX regimen. However, as shown in our study, the efficacy of the single ampicillin or TMP/SMX as the first-line treatment is very low. In our study, ciprofloxacin showed 79.1% sensitivity against E. coli, and 88.3 % against K. pneumoniae, which tells it can be recommended as the first-line oral therapy.

In Korea the proportion of complicated APN has been reported to be approximately 21.1-37.8% (8-10), and in our study, it is shown 32.7%. And in male it was higher than in females. Finkelstein et al. (18) have reported that in complicated APN, the longer time was required for the amelioration of clinical symptoms, and such result was validated in our study. These patients are also at increased risk for morbidity such as bacteremia and sepsis, perinephric abscess, and renal deterioration. Therefore, special attention is required, which includes obtaining culture data and urinary tract imaging, assessing renal function, and providing culture-specific antimicrobial therapy. More specific medical or surgical therapy and urinary tract drainage may be required when necessary (19).

In our study population, complicated factors such as structural or functional disorders were in the order of urinary tract stone disease, vesicoureteral reflux, neurogenic bladder, ureteral obstruction, and benign prostate hyperplasia. In addition, among 335 complicated APN patients, 94 patients received the curative urologic procedures. To treat urinary tract stones, ESWL, ureteroscopic stone removal or other lithotripsy were performed in 42 cases, and in hydronephrosis due to ureteral obstruction, to preserve renal function and to diverse urinary flow, percutaneous nephrostomy was performed in 23 cases.

Most of the complicated APN patients who didn't receive surgical treatment were DM patients. And the others were the diseases that were impossible to operate (e.g., nephrocalsinosis, medullary sponge kidney, polycystic kidney), spontaneous expelled urinary stone disease, low-grade VUR, voiding dysfunction managed by medical therapy (alpha adrenergic blocking agents, anticholinergics, or cholinergic agents), and so on. But physicians should closely follow up these patients to prevent recurrent infection.

As systemic diseases, DM has been reported to act as the most important factor (8-10). In our study, DM was 29.3% of complicated APN, which was most common. Several possible interactions occur between DM and UTI. Factors that may predispose diabetics to complicated infections include autonomic neuropathy leading to poor bladder emptying and urinary stasis, microangiopathy, leukocyte dysfunction, and frequent urinary tract instrumentation (20). The prevalence of bacteriuria is twice higher than the nondiabetics and asymptomatic bacteriuria in diabetes frequently progresses to symptomatic and upper UTIs, so it should be treated. In addition, APN in DM patients is 5 times more frequent than the nondiabetics (21) and can lead to serious complications like septic shock, EPN, renal and perirenal abscess, and papillary necrosis (22). Especially, EPN is life-threatening acute necrotizing parenchymal and perirenal infection. It is required immediate nephrectomy with glycemic control measures and antibiotic administration is crucial. In inoperable cases, percutaneous drainage can be an effective treatment option. Therefore diabetics with febrile UTI should undergo urinary tract imaging. Renal ultrasound should be performed if obstruction is suspected, whereas a computed tomography (CT) scan is the imaging modality of choice to evaluate for renal abscess, EPN, and other complications of UTI.

Upper urinary tract obstruction, whether primary or secondary, due to infravesical obstruction (e.g. prostatic diseases, neurogenic bladder), can lead to highly elevated intrapelvic pressure allowing intrarenal reflux of infected urine. In these patients, instant drainage of the obstruction is mandatory as is the immediate institution of broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment. If proper therapy is delayed, the infection might progress to pyonephrosis, renal abscess or urosepsis that still has a high mortality (23). To prevent these complications, a routine ultrasound examination of the kidneys should be performed during each episode of febrile UTI.

Infection due to indwelling catheters, cystoscopy, double J-stent insertion or other urologic manipulation was detected in 8 cases. Naber et al. recommended preventive antibiotics for highly risk patients (poor systemic performance, DM and other metabolic abnormality, immunosuppressive drug, patients with artificial cardiac valvular replacement) while performing cystoscopy, ureteroscopy, percutenous nephrostomy, and ESWL (6). Recommended antibiotic agents are fluroquinolone, aminopenicillin/beta-lactamase inhibitor, and second-generationed cephalosporin. In addition, in the case with an indwelling catheter in the bladder, the possibility of bacteriuria is increased daily by 3-10%, and thus after one month, bacteriuria is detected in most cases (24). Most cases are asymptomatic, however, sepsis may be associated in less than 5%, and thus if indwelling catheters are required, to prevent the development of bacteriuria, it is required to maintain a closed system, and clinicians should make efforts to remove the catheter as early as possible (25, 26).

One third of APN is complicated APN, and over 60% of its origin is urological diseases. In addition, for its treatment, appropriate urological procedures are required. Most of all, if fever and costovertebral angle tenderness sustain over 4 days, radiologic studies will be performed immediately, and then proper surgical procedure should be performed. The portion of the cases that bacteria were isolated in urine culture were 49.1%, which is speculated due to the result of overusing antibiotics without prescription prior to admission. In addition, in APN, sepsis is associated in 10.1%, and resistance to antibiotics shows a trend on the rise, hence, clinical attentions are required. Particularly, antibiotics resistance to ampicillin and TMP/SMX is high and the sensitivity is on the decrease with the time, therefore, it is thought that the reconsideration of their selection as first-line drugs is required.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MOST). No. R13-2002-020-02001-0 (2007).

References

- 1.Bergeron MG. Treatment of pyelonephritis in adults. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:619–649. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ki M, Park T, Choi B, Foxman B. The epidemiology of acute pyelonephritis in South Korea, 1997-1999. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:985–993. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robets FJ, Geere IW, Coldman A. A three-year study of positive blood cultures, with emphasis on prognosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:34–46. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ispahani P, Pearson NJ, Greenwood D. An analysis of community and hospital-acquired bacteraemia in a large teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Q J Med. 1987;63:427–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SW, Lee JY, Park WJ, Cho YH, Yoon MS. Antibiotic sensitivity to the causative organism of acute simple urinary tract infection. Korean J Urol. 2000;41:1117–1124. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naber KG, Hofstetter AG, Bruhl P, Bichler KH, Lebert C. Guidelines for the perioperative prophylaxis in urological interventions of the urinary and male genital tract. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safrin S, Siegel D, Black D. Pyelonephritis in adult womem: inpatient versus outpatient therapy. Am J Med. 1988;85:793–798. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(88)80023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Son HS, Ahn JH, Lee TW, Ihm CG, Kim MG. Clinical study on 740 cases of acute pyelonephritis (1980-1989) Korean J Nephrol. 1990;3:380–388. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song JH, Lee JH, So JH, Choe SY, Suh DY. A clinical study on acute pyelonephritis. Korean J Med. 1983;26:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min HJ. Acute pyelonephritis; clinical study and consideration about inpatient therapy. Korean J Med. 1998;55:232–244. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolle LE, Harding GK, Preiksaitis J, Ronald AR. The association of urinary tract infection with sexual intercourse. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:579–583. doi: 10.1093/infdis/146.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlowsky JA, Jones ME, Thornsberry C, Critchley I, Kelly LJ, Sahm DF. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among urinary tract pathogens isolated from female outpatients across the US in 1999. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daza R, Gutierrez J, Piedrola G. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial strains isolated from patients with community-acquired urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:211–215. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagenlehner FM, Niemetz A, Dalhoff A, Naber KG. Spectrum and antibiotic resistance of uropathogens from hospitalized patients with urinary tract infections: 1994-2000. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:557–564. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren JW, Abrutyn E, Hebel JR, Johnson JR, Schaeffer AJ, Stamm WE. Guidelines for antimicrobial treatment of uncomplicated acute bacterial cystitis and acute pyelonephritis in women. Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:745–758. doi: 10.1086/520427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stamm WE, Hooton TM. Management of urinary tract infections in adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1328–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310283291808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talan DA, Stamm We, Hooton TM, Moran GJ, Burke T, Iravani A, Reunning-Scherer J, Church DA. Comparison of ciprofloxacin (7 days) and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (14 days) for acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis pyelonephritis in women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1583–1590. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelstein R, Kassis E, Reinhertz G, Gorenstein S, Herman P. Community-acquired urinary tract infection in adults: a hospital view point. J Hosp Infect. 1998;38:193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nickel JC. The management of acute pyelonephritis in adults. Can J Urol. 2001;8(Suppl 1):29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolnald A, Ludwig E. Urinary tract infections in adults with diabetes. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhanel GG, Harding GK, Nicolle LE. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in patients with diabetes mellitus. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:150–154. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.5.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carton JA, Maradona JA, Nuno FJ, Fernandez-Alvarez R, Perez-Gonzalez F, Asensi V. Diabetes mellitus and bacteraemia. A comparative study between diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Eur J Med. 1992;1:281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulmi FA, Felsen D, Vaughan ED. The pathophysiology of urinary tract obstruction. In: Walsh PC, Retick AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell's Urology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. pp. 411–462. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bryan C, Reynolds K. Hospital-acquired bacteremic urinary tract infection: epidemiology and outcome. J Urol. 1984;132:494–498. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49707-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warren JW. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:299–303. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren JW, Platt R, Thomas RJ, Rosner B, Kass EH. Antibiotic irrigation and catheter-associated urinary-tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:570–573. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197809142991103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]