Abstract

The aim of this study is to elucidate the clinical spectrum and frequency of non-motor symptoms during off periods (NMOS) in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients with motor fluctuation. We compared clinical characteristics between PD patients with motor symptoms only (M-off) and those with both motor and non-motor symptoms (NM-off) during off periods. The association of NMOS with parkinsonian clinical characteristics was also investigated. Sixty-seven consecutive PD patients of both M-off and NM-off groups were included in this study. We reviewed medical records, interviewed the patients, and administered a structured questionnaire. NMOS is classified into three categories: autonomic, neuropsychiatric and sensory. The frequency of NMOS and their individual manifestations were assessed. Of 67 patients with off symptoms, 20 were M-off group and 47 NM-off group. Among NMOS, diffuse pain was the most common manifestation, followed by anxiety and sweating. There were no significant differences between M-off and NM-off groups with regard to age, duration of disease and treatment, interval between onset of parkinsonian symptoms and off symptoms and off periods. Patients taking higher dosage of levodopa had fewer NMOS. NMOS is frequent in PD. Comprehensive recognition of NMOS can avoid unnecessary tests and is important for optimal treatment in PD.

Keywords: Parkinson Disease, Non-Motor Off, Motor Fluctuation

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurological condition which is characterized and diagnosed by the presence of classical motor symptoms, such as tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and gait disturbance. Patients with PD may also experience many complaints beyond motor symptoms, which are referred to as non-motor symptoms (NMS). Ever since James Parkinson first described the disease, various disturbances not associated with motor symptoms have been noted (1).

The NMS of PD is very diverse. These include neuropsychiatric symptoms, sleep disturbance, dysautonomia and sensory symptoms, and have a great impact on the quality of life for PD patients (2). These symptoms may be ascribed to extensive pathology within the brain. This pathology includes damage to the brainstem, as well as to the cerebral cortex, as shown by Braak et al. (3). These symptoms are also generally acknowledged to be poorly responsive to dopaminergic treatment (4). Although these contribute to disability and impaired quality of life, NMS are often poorly recognized and recognition of these symptoms is essential for the optimal care of patients with PD (5).

In this study, we attempted to elucidate the clinical spectrum and prevalence of non-motor symptoms during off periods (NMOS) distinct from fluctuation of NMS (NMSF), which was previously reported (6-8), occurring during not only off but on or biphasic periods. This study investigating only NMOS has several clinical implications. First, most fluctuating NMS occurs during off periods. It is plausible that, given that motor fluctuation has different clinical features; dyskinesia or cranio-cervical dystonia during on state and various parkinsonian features during off state, the clinical spectrum of NMS during off state will be different from that occurring on state. Thus, the pattern of NMOS might be different from that of NMSF. Second, therapeutically, we can speculate that NMOS is easier to manage with several strategies shortening the off period than NMS occurring during on period like motor symptoms where parkinsonian features occurring during off period are much easier to manage than dyskinesia occurring during on state. Previous reports indicated that some of NMOS improved by adding or rearranging dopaminergic regimen (6, 9), but little has been known about responsiveness of NMS occurring during 'on' state, implying the importance of early recognition of NMOS in PD.

We also compared the two groups (M-off and NM-off) and investigated the association of NMOS with regard to other parkinsonian characteristics, such as the sex, age, age of disease onset, symptom of onset (tremor vs. akinetic-rigid dominant), duration of disease and levodopa administration, dose of levodopa, interval between onset of parkinsonian symptoms and off symptoms, off periods, severity of motor symptoms, and modified Hoehn and Yahr stage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

We evaluated 67 consecutive out-patients (23 males and 44 females) from Parkinson's disease Center in Dong-A University Medical Center. They were diagnosed as clinically probable PD under the criteria of Gelb and colleagues (10). All patients had been treated with dopaminergic therapy including levodopa and showed motor fluctuation, including 'wearing-off'. Patients with clinically overt dementia or severe depression were excluded in the study. We divided the patients into two groups; the patients who had only motor symptoms (M-off group) and the patients with non-motor symptoms (NM-off group) during motor off periods. All patients in this study had provided written informed consent. The study was approved by institutional review boards of Dong-A University.

Methods

This study involved taking a careful history about PD, including the duration of symptoms and treatment, onset and character of motor complication, and medication. All the patients were prospectively investigated and interviewed during on phase. Motor performance was evaluated on symptom triad using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (20, 23, 26 of part III) and Hoehn and Yahr stage (11, 12).

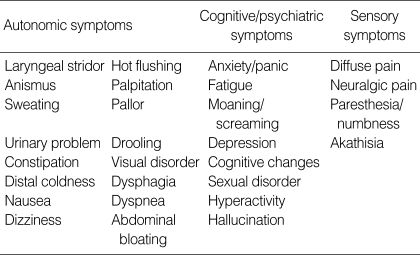

All the patients were interviewed in a standard motor state with a structured questionnaire, which were categorized as 4 sensory, 16 autonomic and 8 cognitive/psychiatric symptoms (Table 1). These symptoms were reported in the previous studies and were collected for this study (6-8). The patients answered "yes" or "no" to each question for the presence of symptoms developed or aggravated at off periods during recent 2 weeks. We also compared the clinical characteristics between M-off and NM-off groups.

Table 1.

Non-motor symptoms during off period

Statistical analysis

We used non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test and Pearson chi-square test with the help of SPSS 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) to compare the characteristics between M-off and NM-off groups. Spearman's correlation test and Pearson chi square test were used to find the correlation between NMOS and clinical characteristics. p values of less than 0.05 were accepted as significant.

RESULTS

Clinical spectrum and frequency of NMOS

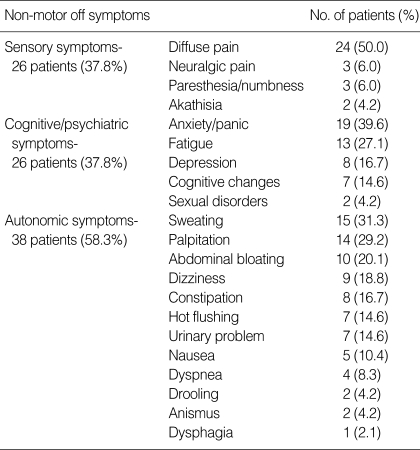

Of 67 patients with motor fluctuations, 47 patients (70.1%, 15 males and 32 females) had both motor and non-motor symptoms (NM-off group), and 20 patients (8 males and 12 females) had motor symptoms alone (M-off group) during off periods. Of the 31 symptoms investigated, diffuse pain was the most common NMS, followed by anxiety, sweating, palpitation, fatigue, abdominal bloating, and dizziness. Patients had an average of 3.5 symptoms (range 1 to 12). Autonomic symptoms were more frequent (79.2%) than sensory and cognitive/psychiatric symptoms (52.1%, each) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of non-motor off symptoms

Comparison between M-off and NM-off groups

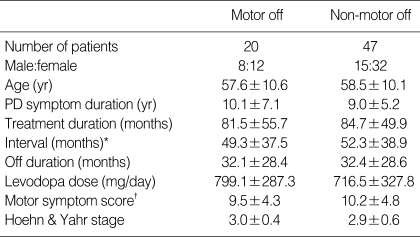

Sex, age, age of disease onset, symptom of onset, duration of disease and treatment, interval between onset of parkinsonian symptoms and off symptoms, and between dopaminergic treatment and onset of motor fluctuations were not significantly different between M-off and NM-off groups. Patients of M-off group showed more frequent off dystonia but the difference was not significant. Other characteristics such as The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores of motor symptoms, Hoehn and Yahr stage and medication (levodopa equivalent dose, dopamine agonist, MAOB/COMT inhibitor, anxiolytics and antidepressant), showed no statistical difference between the two groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Motor off group and Non-motor off group

Data are presented as mean±SD unless otherwise indicated.

*interval between onset of parkinsonian symptoms and off symptoms; †sum of scores of rigidity, tremor & bradykinesia.

PD, Parkinson's disease.

Influence of the clinical characteristics on NMOS

Female patients complained about sensory symptoms more frequently (50.0% vs. 13.0%, p=0.003). However, the duration of parkinsonian symptoms and treatment in female group were significantly shorter than those of the male group. Psychiatric symptoms were more common in the younger group (age below median 59 yr, 50.0% vs. 25.7%, p=0.040) in spite of milder motor symptoms and HY stages. We could not find any influence of age at disease onset, duration of disease and treatment, severity of motor symptoms, and Hoehn and Yahr stage on NMOS. Mean dose of levodopa showed significant influences on NMOS. Patients taking higher doses of levodopa (dose above median 750 mg/day) had significantly fewer NMOS (1.6±1.8 vs. 3.3±3.2, p=0.024), especially in autonomic (0.8±1.1 vs. 1.8±1.9, p=0.033) symptoms.

The number of autonomic symptoms that patients had at 'off' state was negatively correlated with dose of levodopa (r=-0.255, p=0.038) and positively with motor symptom score (r=0.247, p=0.047)

DISCUSSION

Management of PD has been mainly focused on the treatment of motor symptoms. Dopaminergic replacement has shown great improvement on motor dysfunctions in PD patients. In contrast to motor symptoms, NMS of PD have received relatively little attention, despite diverse presentations of these conditions and their impact on the quality of life. However, some physicians have devoted significant attention to the NMS of PD (5, 13). These efforts moved the Movement Disorder Society to modify the existing UPDRS to include independent subpart of NMS (14).

NMS are very diverse and common in PD patients (1). These symptoms can occur any time during the illness, even before presentation of motor symptoms. Like motor symptoms, NMS begin to fluctuate as the illness progresses (6). However, it is difficult to find convincing evidence that many of NMSF are exclusively related to PD. For example, anxiety, which was reported to be the most common NMSF associated with PD, may be due to many other conditions besides PD (7). As a result, the frequency of NMSF might be overestimated. Therefore, in our study, we strictly defined NMOS as NMS developed or aggravated during motor off periods and investigated the prevalence of NMOS to avoid the contamination of non-specific subjective symptoms that might occur independently of PD. We also administered a structured questionnaire about a wide range of symptoms typically experienced during the motor off period. This type of questionnaire was designed to overcome the underestimation of NMS that would result from asking a single question with an open answer ('Tell us about any symptom that are associated with the off state') (7).

The overall rate of NMOS in this study was 71.6%. Previous studies that focused on NMSF reported a wide range of prevalence, between 17% and 100%, of NMS among PD patients showing motor fluctuations. Hillen et al. reported that only 17% of patients with fluctuant PD had NMSF (8). They used a single question with an open answer and likely underestimated the prevalence of NMS. On the other hand, Witjas et al. reported that all patients had at least one type of NMSF, most of which were associated with the off state (7). This study overestimated the prevalence because they included NMS that occurred not only during the off period, but other periods as well. The estimated prevalence (71.6%) in our study may not reflect all the NMS because we excluded NMS that may occur during periods other than off state and might be slightly underestimated. However, this approach offers some implications for the management of NMS. Many NMS are subjective and vague. When these symptoms occur during off phase, we can avoid unnecessary investigation and useless treatments by recognizing these symptoms as part of PD. In addition, NMOS can be managed by rearrangement of dopaminergic regimen (9). On the other hand, when NMS that are not associated with PD occurs and is wrongly considered as symptoms of NMSF, the chance of proper management will be missed.

Unlike previous studies (7, 8, 15, 17), diffuse pain was the most frequent NMOS (50%) in our study. These discrepancies may be attributed to methodological differences. Our study counted NMS occurring during off periods and suggests that non-motor sensory symptoms are exclusive to the off period. It also suggests that sensory symptoms, unlike most of NMS which does not respond to dopaminergic therapy, are largely related to dopaminergic system. This conclusion is supported by the fact that most of sensory symptoms that occur during the off period can be relieved by dopaminergic therapy (9, 15). The next most common NMOS are anxiety and sweating (39.6 & 31.3%, respectively). This result has recapitulated by other authors (7). Akathisia, sensory dyspnea, and depressed mood were also common symptoms in other reports (15). Dysautonomic symptoms, such as palpitation, abdominal bloating, dizziness, constipation, were also prevalent (more than 15% of the patients) and these can lead to medical attention resulting in unnecessary tests and treatments.

Intriguingly, results of our study suggest that women patients had less severe motor symptoms, yet experienced more frequent NMOS. Additionally, patients with younger onset had more frequent psychiatric NMOS. Several explanations are possible. Generally, women patients are more willing to express their uncomfortable symptoms. More importantly, both women and patients with younger onset have had lower dosage of levodopa compared to men and patients with older onset due to concerns about levodopa-induced motor complications. It is not surprising that patients taking higher dosage of levodopa had less frequent NMS because, in our study excluding NMS that might occur during peak-dose or biphasic periods, higher levodopa dosages reduce the off time or severity of symptom and alleviate the NMOS associated with dopamine system.

The pathophysiology of motor fluctuation remains unclear. However, evidence definitely indicates that it relates to dopaminergic treatment (6). NMS also fluctuates as the illness progresses. These symptoms usually appear during 'off' periods, but may also occur during 'on' or biphasic periods. The fact that NMSF are usually in harmony with the motor fluctuation in PD suggests that the dopaminergic system is involved in the modulation of other neurotransmitters, such as serotonin or norepinephrine (6, 16). These neurotrasmitters might fluctuate along with dopamine and be involved in the pathophysiology of NMSF, either directly or indirectly. Gunal et al. reported that early age of disease onset, longer duration of disease and higher dose of levodopa could be risk factors for sensory fluctuation (17). It is conceivable that those risk factors, well known for motor fluctuation, could also be related to sensory fluctuation. This is because this fluctuation occurred exclusively during motor 'off' periods in their study, suggesting that sensory symptoms are linked to the dopaminergic system. However, our results fail to find any correlation between those factors and NMOS. Further studies will be needed to determine whether the risk factors of motor fluctuation can be applied similarly to NMSF and the pathophysiology of NMSF in PD.

Footnotes

This article was supported by Dong-A University Research Fund in 2005.

References

- 1.Parkinson J. An essay on the shaking palsy. 1817. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;14:223–236. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:235–245. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rub U, de Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goetz CG, Poewe W, Rascol O, Sampaio C. Evidence-based medical review update: pharmacological and surgical treatments of Parkinson's disease: 2001 to 2004. Mov Disord. 2005;20:523–539. doi: 10.1002/mds.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri KR, Yates L, Martinez-Martin P. The non-motor symptom complex of Parkinson's disease: a comprehensive assessment is essential. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5:275–283. doi: 10.1007/s11910-005-0072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley DE, Lang AE. The spectrum of levodopa-related fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1993;43:1459–1464. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.8.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witjas T, Kaphan E, Azulay JP, Blin O, Ceccaldi M, Pouget J, Poncet M, Cherif AA. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease: frequent and disabling. Neurology. 2002;59:408–413. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillen ME, Sage JI. Nonmotor fluctuations in patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1996;47:1180–1183. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quinn NP, Koller WC, Lang AE, Marsden CD. Painful Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 1986;1:1366–1369. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91674-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahn S, Elton RI, Members of the UPDRS Development Committee . In: Recent development in Parkinson's disease. Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, Golstein M, editors. vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Health Care Information; 1987. pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hely MA, Morris JG, Reid WG, Trafficante R. The Sydney Multicentre Study of Parkinson's disease: non-L-dopa-responsive problems dominate at 15 yr. Mov Disord. 2005;20:190–199. doi: 10.1002/mds.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson's Disease. The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003;18:738–750. doi: 10.1002/mds.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raudino F. Non motor off in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104:312–315. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCance-Katz EF, Marek KL, Price LH. Serotoninergic dysfunction in depression associated with Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1992;42:1813–1814. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.9.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunal DI, Nurichalichi K, Tuncer N, Bekiroglu N, Aktan S. The clinical profile of nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease patients. Can J Neurol Sci. 2002;29:61–64. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100001736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]