Abstract

We present a case of perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) in the abdominal cavity at the falciform ligament. A 30-yr-old Korean man visited to hospital for the evaluation of a growing, palpable abdominal mass. He had felt the mass growing over 6 months. There was no family or personal history of tuberous sclerosis. The resected specimen showed a mass of 8.0×7.0×5.5 cm in size. Histological examination showed sheets of spindle-to-epithelioid cells with clear-to-eosinophilic cytoplasm. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells were positive for HMB-4 (gp100) and smooth muscle actin. They were also positive for the S-100, which is a marker of neurogenic and melanocytic tumors. Patient was treated with radical resection of tumor without any adjuvant therapy. He is well and on follow-up visits without tumor recurrence.

Keywords: Angiomyolipoma, Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Neoplasms, Lymphangiomyomatosis, Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

The perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas) are a family of related mesenchymal neoplasms that include angiomyolipoma, lymphangiomyomatosis, and clear cell 'sugar' tumor of the lung (1). In 1991, investigations of HMB-45 (gp100) immunoreactivity and the presence of premelanosomes in both clear cell 'sugar' tumors (CCSTs) of the lung and the epithelioid clear cell component of angiomyolipoma (AML) of the kidney and liver were published (2-6). Bonetti et al. first proposed a cellular link among these unusual mesenchymal lesions and lymphangiomyomatosis (LAM) (7). Soon after, the same group suggested the descriptive term 'perivascular epithelioid cell' (PEC) for the distinctive cell type found in these three lesions, and hypothesized that PECs may originate from the walls of blood vessels based on the observation that these cells are frequently and intimately related to such structures (8). Most of the patients with lesions of the PEComa family are female, and some patients also show coexistence of the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) (9). Although there are strong associations between the TSC, AML, and LAM, this association is much less clear for the rare PEComas (10). Malignant PEComas are extremely rare, and they have been reported to occur in the uterus, broad ligament, prostate, small intestine, rectum, skull base, and heart (11-16). We describe a case of PEComa in the abdominal cavity at the falciform ligament.

CASE REPORT

A 30-yr-old Korean man visited to hospital for the evaluation of a growing palpable abdominal mass, which he had felt growing over 6 months. There was no family or personal history of tuberous sclerosis. Physical examination revealed a non-tender, palpable mass in the periumbilical area. The chest radiogram was normal. Colonoscopic examination revealed non-specific abnormal findings. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed an intraabdominal mass with a size of about 7.5 cm that was supposed to originate from the falciform ligament. The mass was well enhanced and showed wall calcification (Fig. 1), and laboratory data showed no abnormalities. Surgical excision was performed. The resected specimen had a weight of 199.1 g and dimensions of 8.0×7.0×5.5 cm. The resected specimen showed a uniloculated cystic mass with a solid portion. The solid portion was yellow-brown in color and revealed foci of hemorrhage and necrotic changes (Fig. 2). Histological examination showed sheets of spindle-to-epithelioid cells with clear-to-eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemically, tumor cells were positive for HMB-45 (Fig. 4) and smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Fig. 5). They were also positive for the S-100, a marker of neurogenic and melanocytic tumors, and were negative for the CD117 (c-kit), which typically shows positivity in classic gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). The tumor cells were also negative for Factor VIII, CD34, CD31, CK, and desmin. However, the tumor showed high cellularity and necrotic foci. These features suggest that the tumor had aggressive potential and a high probability of local recurrence or metastasis. The Ki-67 proliferative index was approximatively 15 percent of cells. At 6 days after surgical excision, the patient was discharged. Because the biological behavior of this tumor is still unclear, with descriptions in the literature of PEComas with metastases, we had planned follow-up investigation in the form of CT scans of the abdomen and the thorax. Until now, there was no tumor recurrence.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal computed tomography. Well enhancing mural nodule and wall calcification were noted.

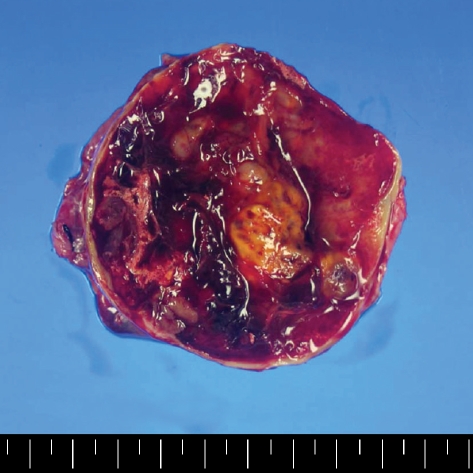

Fig. 2.

Gross finding. On section it showed a uniloculated cystic mass with solid portion. The solid portion was yellow brown color and it revealed foci of hemorrhage and necrotic change.

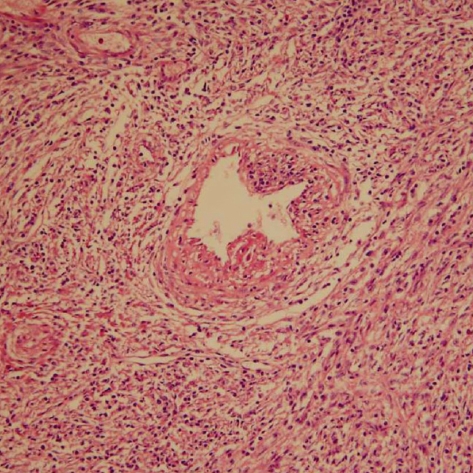

Fig. 3.

Histologic findings (H&E stain, ×100). The lesion was made of sheets of spindle-to-epithelioid cells on perivascular space. The spindle cells had clear-to-eosinophilic cytoplasm.

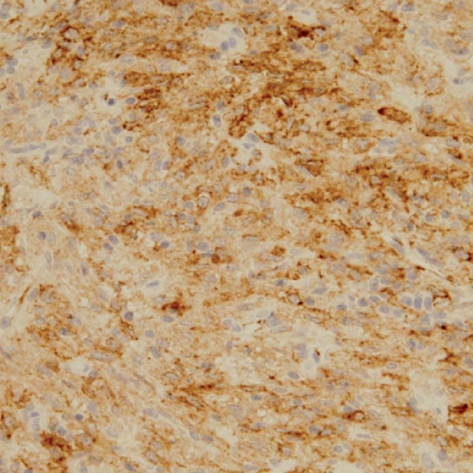

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical stain. Tumor cells were positive for HMB-45.

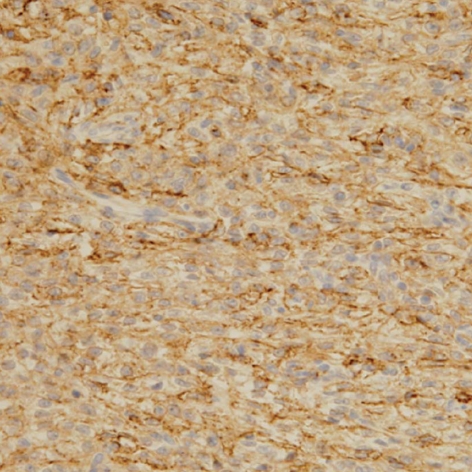

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical stain. Tumor cells were positive for SMA.

DISCUSSION

The "perivascular epithelioid cell" (PEC) was first proposed by Bonetti and colleagues in 1992 as an explanation for the presence of HMB-45 (gp100) immunoreactivity and premelanosomes in both clear cell "sugar" tumors of the lung and angiomyolipomas (8). The PECs are characterized by epithelioid cells with a clear to faintly eosinophilic cytoplasm, a perivascular location, and the unique co-expression of smooth muscle actin isoforms and melanocytic markers such as the gp100 protein recognized by HMB-45 (8). HMB-45 and Melan-A are the most sensitive melanocytic markers in PEComa. On our case, tumor cells were positive for HMB-45, SMA, and S-100. At the time of the final diagnosis, no metastatic lesions were present. There was no family or personal history of tuberous sclerosis. A significant association was noted between a tumor size of 8 cm (median size), mitotic activity greater than 1/50 HPF, and necrosis with aggressive behavior (1). Patient age (median age: 46 yr), infiltrative growth pattern, gynecologic primary site, high cellularity, high nuclear grade, atypical mitotic figures, vascular invasion, and the growth pattern of the tumor (spindled or epithelioid) were not associated with aggressive behavior (1). In our case, the tumor size was 8.0 cm. The tumor showed high cellularity and necrotic foci. These features suggested that the tumor had aggressive potential and a high probability of local recurrence or metastasis. The Ki-67 proliferative index was approximately 15 percent of cells. Although it has been suggested that PEComas do not express S-100 protein, thereby allowing them to be distinguished from melanoma and clear cell sarcoma, this was not the case. Some articles have been published on this subject. A series of seven very young patients (age range, 3-29, median, 11 yr) PEComa of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres was reported in 2000. Therapy consisted of surgical resectioning. During the mean follow-up of 18 months (range, 6 months to 5 yr) in six of seven cases, five patients remained healthy, and one was affected by metastasis of the lung (17). Since relatively few malignant PEComas have been reported, firm criteria for malignancy have yet to be established. Today, the recommended treatment is radical removal of the tumor. Reports of additional adjuvant treatment do not exist. Special attention should be paid to the lungs and liver because of potential metastasis (18). A PEComa situated elsewhere has to be excluded because the tumor described here could have been a primary tumor or a metastasis. Because PEComas can behave in an aggressive manner, careful follow-up is warranted. In addition, to perform a pathological diagnosis, recognition of the clinicopathological, histological, and immunohistochemical (HMB-45 positive) features of PEComa seems to be very important.

References

- 1.Folpe AL, Mentzel T, Lehr HA, Fisher C, Balzer BL, Weiss SW. Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms of soft tissue and gynecologic origin: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1558–1575. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173232.22117.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pea M, Bonetti F, Zamboni G, Martignoni G, Riva M, Colombari R, Mombello A, Bonzanini M, Scarpa A, Ghimenton C. Melanocyte-marker-HMB-45 is regularly expressed in angiomyolipoma of the kidney. Pathology. 1991;23:185–188. doi: 10.3109/00313029109063563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pea M, Bonetti F, Zamboni G, Martignoni G, Fiore-Donati L, Doglioni C. Clear cell tumor and angiomyolipoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:199–202. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199102000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weeks DA, Malott RL, Arnesen M, Zuppan C, Aitken D, Mierau G. Hepatic angiomyolipoma with striated granules and positivity with melanoma--specific antibody (HMB-45): a report of two cases. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1991;15:563–571. doi: 10.3109/01913129109016264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaffey MJ, Mills SE, Zarbo RJ, Weiss LM, Gown AM. Clear cell tumor of the lung. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evidence of melanogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:644–653. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gal AA, Koss MN, Hochholzer L, Chejfec G. An immunohistochemical study of benign clear cell ('sugar') tumor of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:1034–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G, Iuzzolino P. Cellular heterogeneity in lymphangiomyomatosis of the lung. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:727–728. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonetti F, Pea M, Martignoni G, Zamboni G. PEC and sugar. Am J Surg Pathol. 1992;16:307–308. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) in the genitourinary tract. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:36–41. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31802e0dc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Saleem T, Wessner LL, Scheithauer BW, Patterson K, Roach ES, Dreyer SJ, Fujikawa K, Bjornsson J, Bernstein J, Henske EP. Malignant tumors of the kidney, brain, and soft tissues in children and young adults with the tuberous sclerosis complex. Cancer. 1998;83:2208–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris GC, McCulloch TA, Perks G, Fisher C. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumour ("PEComa") of soft tissue: a unique case. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1655–1658. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200412000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink D, Marsden DE, Edwards L, Camaris C, Hacker NF. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) arising in the broad ligament. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14:1036–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.014549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehman NL. Malignant PEComa of the skull base. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1230–1232. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000128668.34934.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanai H, Matsuura H, Sonobe H, Shiozaki S, Kawabata K. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the jejunum. Pathol Res Pract. 2003;199:47–50. doi: 10.1078/0344-0338-00353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan CC, Yang AH, Chiang H. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor involving the prostate. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:E96–E98. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e96-MPECTI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evert M, Wardelmann E, Nestler G, Schulz HU, Roessner A, Rocken C. Abdominopelvic perivascular epithelioid cell sarcoma (malignant PEComa) mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumour of the rectum. Histopathology. 2005;46:115–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folpe AL, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG, Paulino AF, Taboada EM, Meehan SA, Weiss SW. Clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres: a novel member of the perivascular epithelioid clear cell family of tumors with a predilection for children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1239–1246. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birkhaeuser F, Ackermann C, Flueckiger T, Guenin MO, Kern B, Tondelli P, Peterli R. First description of a PEComa (perivascular epithelioid cell tumor) of the colon: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1734–1737. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]