Abstract

A SNP in the gene encoding lactase (LCT) (C/T-13910) is associated with the ability to digest milk as adults (lactase persistence) in Europeans, but the genetic basis of lactase persistence in Africans was previously unknown. We conducted a genotype-phenotype association study in 470 Tanzanians, Kenyans and Sudanese and identified three SNPs (G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907) that are associated with lactase persistence and that have derived alleles that significantly enhance transcription from the LCT promoter in vitro. These SNPs originated on different haplotype backgrounds from the European C/T-13910 SNP and from each other. Genotyping across a 3-Mb region demonstrated haplotype homozygosity extending >2.0 Mb on chromosomes carrying C-14010, consistent with a selective sweep over the past ~7,000 years. These data provide a marked example of convergent evolution due to strong selective pressure resulting from shared cultural traits—animal domestication and adult milk consumption.

In most humans, the ability to digest lactose, the main carbohydrate present in milk, declines rapidly after weaning because of decreasing levels of the enzyme lactase-phlorizin hydrolase (LPH). LPH is predominantly expressed in the small intestine, where it hydrolyzes lactose into glucose and galactose, sugars that are easily absorbed into the bloodstream1. However, some individuals, particularly descendants from populations that have traditionally practiced cattle domestication, maintain the ability to digest milk and other dairy products into adulthood. These individuals have the ‘lactase persistence’ trait. The frequency of lactase persistence is high in northern European populations (>90% in Swedes and Danes), decreases in frequency across southern Europe and the Middle East (~50% in Spanish, French and pastoralist Arab populations) and is low in non-pastoralist Asian and African populations (~1% in Chinese, ~5%-20% in West African agriculturalists)1-3. Notably, lactase persistence is common in pastoralist populations from Africa (~90% in Tutsi, ~50% in Fulani)1,3.

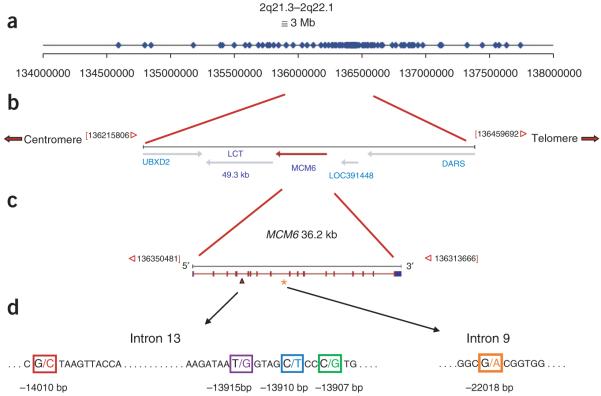

Lactase persistence is inherited as a dominant mendelian trait in Europeans1,2,4. Adult expression of the gene encoding LPH (LCT), located on 2q21, is thought to be regulated by cis-acting elements5 (Fig. 1). A linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype analysis of Finnish pedigrees identified two single SNPs associated with the lactase persistence trait: C/T-13910 and G/A-22018, located ~14 kb and ~22 kb upstream of LCT, respectively, within introns 9 and 13 of the adjacent minichromosome maintenance 6 (MCM6) gene4 (Fig. 1). The T-13910 and A-22018 alleles were 100% and 97% associated with lactase persistence, respectively, in the Finnish study4, and the T-13910 allele is ~86%-98% associated with lactase persistence in other European populations6-8. Although these alleles could simply be in LD with an unknown regulatory mutation6, several additional lines of evidence, including mRNA transcription studies in intestinal biopsy samples9 and reporter gene assays driven by the LCT promoter in vitro10-12, suggest that the C/T-13910 SNP regulates LCT transcription in Europeans.

Figure 1.

Map of the LCT and MCM6 gene region and location of genotyped SNPs. (a) Distribution of 123 SNPs included in genotype analysis. (b) Map of the LCT and MCM6 gene region. (c) Map of the MCM6 gene. (d) Location of lactase persistence–associated SNPs within introns 9 and 13 of the MCM6 gene in African and European populations.

It is hypothesized that natural selection has had a major role in determining the frequencies of lactase persistence in different human populations since the development of cattle domestication in the Middle East and North Africa ~7,500-9,000 years ago2,3,6,13-18. A region of extensive LD spanning >1 Mb has been observed on European chromosomes with the T-13910 allele, consistent with recent positive selection6,14,16-18. Based on the breakdown of LD on chromosomes with the T-13910 allele, it is estimated14 that this allele arose within the past ~2,000-20,000 years within Europeans, probably in response to strong selection for the ability to digest milk as adults.

Although the T-13910 variant is likely to be the causal variant for the lactase persistence trait in Europeans, analyses of this SNP in culturally and geographically diverse African populations indicated that it is present (and at low frequency (<14%)) in only a few West African pastoralist populations, such as the Fulani (or Fulbe) and Hausa from Cameroon15,19,20. It is absent in all other African populations tested, including East African pastoralist populations with a high prevalence of the lactase persistence trait19. Thus, the lactase persistence trait has evolved independently in most African populations owing to distinct genetic events15,19,20.

Here, we examine genotype-phenotype associations in 470 East Africans, and we identify three previously undescribed variants associated with the lactase persistence trait, each of which arose independently from the European T-13910 allele and resulted in enhanced transcriptional activity in LCT promoter-driven reporter gene assays. We demonstrate that the most common variant in Kenyans and Tanzanians spread rapidly to high frequency in East Africa over the past ~7,000 years owing to the strong selective force of adult milk consumption, and we show that chromosomes with these variants have one of the strongest genetic signatures of natural selection yet reported in humans.

RESULTS

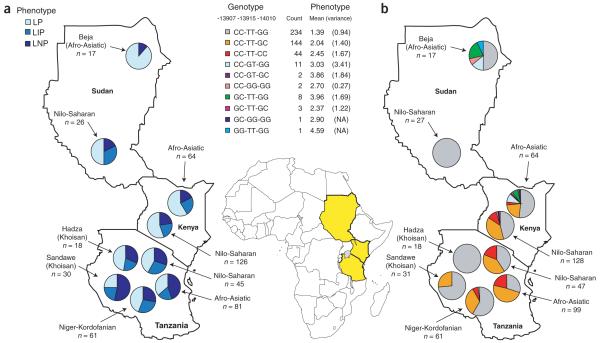

Frequency of lactase persistence in East African populations

We classified individuals as having lactase persistence, lactase intermediate persistence (LIP) or lactase non-persistence (LNP) by examining the maximum rise in blood glucose levels after administration of 50 g of lactose using a lactose tolerance test (LTT)21 in 470 individuals from 43 ethnic groups originating from Tanzania, Kenya and Sudan. These populations speak languages belonging to the four major language families present in Africa (Afro-Asiatic, Nilo-Saharan, Niger-Kordofanian and Khoisan) and practice a wide range of subsistence patterns (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1 online). Because genetic substructure can result in false genotype-phenotype associations22, we analyzed data from samples separated by geographic region and language family, with the exception of the Sandawe and Hadza (both click-speaking Khoisan), whom we analyzed independently (Fig. 2). We made these groupings to minimize population structure, based on a global analysis of ~1,200 unlinked nuclear markers (S.A.T. and F.A.R., unpublished data). The frequency of lactase persistence was highest in the Afro-Asiatic–speaking Beja pastoralist population from Sudan (88%) and lowest in the Khoisian-speaking Sandawe hunter-gatherer population from Tanzania (26%) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

Map of phenotype and genotype proportions for each population group considered in this study. (a) Pie charts representing the proportion of each phenotype by geographic region. LP indicates lactase persistence, LIP indicates lactase intermediate persistence and LNP indicates lactase non-persistence. Phenotypes were binned using an LTT test according to the rise in blood glucose after digestion of 50 g lactose: lactase persistence, >1.7 mM; LIP, between 1.1 mM and 1.7 mM; LNP, <1.1 mM. (b) Proportion of compound genotypes for G/C-13907, T/G-13915 and C/G-14010 in each region. The pie charts are in the approximate geographic location of the sampled individuals.

SNPs associated with lactase persistence in Africans

To identify SNPs associated with regulation of the lactase persistence trait, we sequenced 3,314 bp of intron 13 and 1,761 bp of intron 9 of MCM6 (Fig. 1c,d) in 40 LNP individuals and 69 lactase-persistent individuals at the extremes of the phenotype distribution (Supplementary Fig. 1 online). A newly discovered SNP, G/C-14010, showed a significant association with the lactase persistence trait in Kenyans (n = 53; χ2 = 14.4, d.f. = 2 and P = 0.0007) and Tanzanians (n = 31; χ2 = 10.9, d.f. = 2 and P = 0.0043) (Fig. 1d). A second newly and discovered SNP, T/G-13915, was significantly associated with lactase persistence in Kenyans (n = 53, d.f. = 1, χ2 = 4.70, P = 0.0302) and a third newly discovered SNP, C/G-13907, was marginally significantly associated with lactase persistence in the Beja population from northern Sudan (n = 11, d.f. = 1, χ2 = 2.93, P = 0.0869) (Fig. 1d). Sequencing of these regions in a panel of great apes indicated that the C-14010, G-13915 and G-13907 alleles are derived.

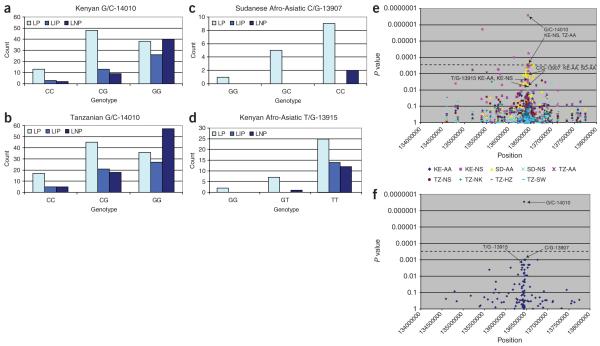

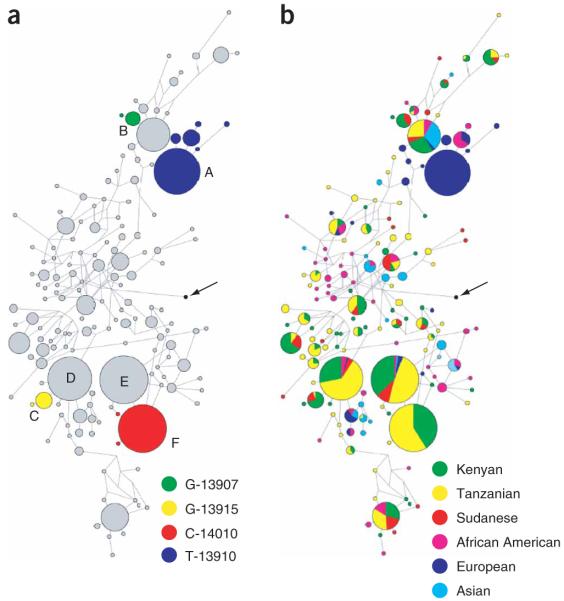

In order to determine regional haplotype structure and further characterize the frequency and degree of association of these alleles, we genotyped 123 SNPs (including G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907) across a 3-Mb region flanking the MCM6 and LCT genes in the full set of 470 individuals with reliable phenotype data and in 24 additional individuals (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 2 online). We determined the genotype-phenotype distribution and χ2 tests of association for our three candidate SNPs (Fig. 3a-d) with data partitioned according to classification of lactase persistence, LIP or LNP in major geographic regions. Additionally, we used a linear-regression approach23,24 (which accounts for the continuous phenotype distribution) to test for an association between all 123 SNPs and a rise in blood glucose after digestion of lactose. G/C-14010 is the most significantly associated SNP in the Kenyan Nilo-Saharan and Tanzanian Afro-Asiatic populations (r2 = 0.19 and 0.16, and P = 2.67 × 10−7 and 2.79 × 10−4, respectively; Fig. 3e) as well as in overall populations combined in the meta-analysis (P = 2.9 × 10−7; Fig. 3f). Although C/G-13907 and T/G-13915 are associated with the phenotype, this association was not statistically significant after Bonferroni correction in either the individual populations or in the meta-analysis (Fig. 3e,f). The C-14010, G-13915 and G-13907 alleles in Africans exist on haplotype backgrounds that are divergent from each other and from the European T-13910 haplotype background (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Genotype-phenotype association for G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907. (a-d) Number of individuals in various genotype and phenotype classes in major geographic regions and/or populations in which they are most prevalent. We observed a significant association for G/C-14010 in Kenya (n = 190, d.f. = 4, χ2 = 21.77, P = 0.0002) and in Tanzania (n = 231, d.f. = 4, χ2 = 21.90, P = 0.0002) We did not observe a significant association for C/G-13907 in the Afro-Asiatic Sudanese (n = 17, d.f. = 2, χ2 = 2.54, P = 0.2808) or for T/G-13915 in Afro-Asiatic Kenyans (n = 61, d.f. = 4, χ2 = 6.14, P = 0.1889). A large proportion of individuals who are homozygous for the ancestral G-14010, T-13915 and C-13907 alleles are classified as lactase persistent, indicating that there are additional unidentified variants associated with lactase persistence in these populations. (e) Linear regression-based test of association for each polymorphic SNP genotyped in this study in each of the subpopulations. Dashed line denotes significance after a conservative Bonferroni correction for the total number of SNPs tested. G/C-14010 is the most significant of all 123 genotyped SNPs in the Kenyan Nilo-Saharan (KE-NS) and Tanzanian Afro-Asiatic (TZ-AA) samples. C/G-13907 shows the strongest (though not significant) association of all other genotyped SNPs in the Kenyan Afro-Asiatic (KE-AA) samples. (f) Meta-analysis of the combined P values for each SNP over all subpopulations. G/C-14010 is highly significant, even after Bonferroni correction (P = 2.9 × 10−7). C/G-13907 and T/G-13915 are not significant after Bonferroni correction (P = 0.001 and P = 0.002, respectively). SD-AA, Sudanese Afro-Asiatic; SD-NS, Sudanese Nilo-Saharan; TZ-NS, Tanzanian Nilo-Saharan; TZ-NK, Tanzanian Niger-Kordofanian; TZ-HZ, Tanzanian Hadza; TZ-SW, Tanzanian Sandawe.

Figure 4.

Haplotype networks consisting of 55 SNPs spanning a 98-kb region encompassing LCT and MCM6. (a) Distribution of the lactase persistence–associated haplotypes. Haplotypes with a T allele at -13910 are indicated in blue, those with a G allele at -13907 in green, those with a C allele at -14010 in red and those with a G allele at -13915 in yellow. The arrow points to the inferred ancestral-state haplotype. (b) Network analysis of LCT and MCM6 haplotypes indicating frequencies in the current data set and in Europeans, Asians and African Americans previously genotyped in ref. 14.

Based on analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the phenotypes for each of the six classes of observed compound G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907 genotypes, ~20% of the total phenotypic variation is accounted for by the genotypes in the pooled sample, suggesting that there are environmental and/or measurement factors, and possibly unidentified genetic factors, influencing the LTT phenotype in this data set.

Frequency of G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907 in Africans

Genotype frequencies for G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907 are shown in Figure 2b, whereas Supplementary Table 1 gives allele frequencies for these SNPs as well as the European lactase persistence–associated SNPs C/T-13910 and G/A-22018. The T-13910 allele is absent in all of the African populations tested, and we observed the A-22018 allele in a single heterozygous Akie individual from Tanzania. The C-14010 allele is common in Nilo-Saharan populations from Tanzania (39%) and Kenya (32%) and in Afro-Asiatic populations from Tanzania (46%) but is at lower frequency in the Sandawe (13%) and Afro-Asiatic Kenyan (18%) populations and is absent in the Nilo-Saharan Sudanese and Hadza populations (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 1). The C-13907 and G-13915 alleles are at ≥5% frequency only in the Afro-Asiatic Beja populations (21% and 12%, respectively) and in the Afro-Asiatic Kenyan populations (5% and 9%, respectively).

C-14010, G-13915 and G-13907 affect expression in vitro

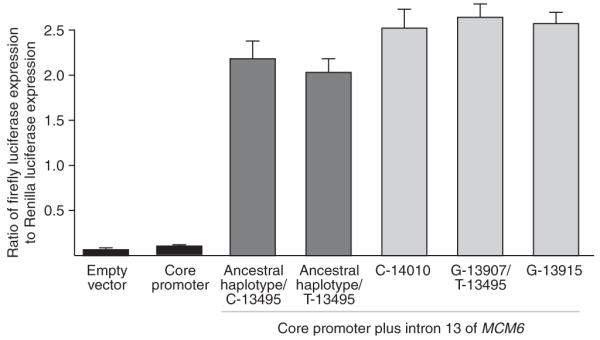

In order to test whether the C-14010, G-13915 and G-13907 variants affect expression from the LCT core promoter, we transfected the human intestinal cell line Caco-2 with luciferase expression vectors driven by the basal 3-kb promoter alone or by the promoter fused to one of five haplotypes of the 2-kb MCM6 intron 13 region: one haplotype with ancestral alleles at the three candidate SNPs (G-14010, T-13915, C-13907), two haplotypes that differed only at the derived C-14010 or G-13915 alleles, one haplotype that differed at the derived G-13907 allele as well as at a linked T-13495 allele and one haplotype that has the ancestral lactase persistence–associated alleles, with a T at position -13945 (to control for the effect of this variant). Differences in luciferase expression between the basal 3-kb LCT core promoter and the promoter plus any of the five MCM6 intron sequence constructs were highly significant (paired t test, P < 0.001), resulting in more than a twenty-fold increase in expression over the core promoter alone (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay of LCT promoter and MCM6 introns. As a control, cells were transfected with the promoterless pGL3-basic vector (‘empty vector’). Basal levels of expression were assessed using a pGL3-basic vector with 3 kb of the 5′ flanking region of LCT (‘core promoter’). Five different haplotypes of the MCM6 intron 13 were inserted upstream of the core promoter that differed at the following sites: (i) a haplotype that is ancestral for the three lactase persistence–associated SNPs, with a C at position -13495; (ii) a haplotype that is ancestral for the three lactase persistence–associated SNPs, with a T at position -13495; (iii) a haplotype that differs from (i) only at C -14010; (iv) a haplotype that differs from (i) at G-13907 and T-13495 and from (ii) only at G-13907; and (v) a haplotype that differs from (i) only at G-13915. Expression levels are reported as the ratio of firefly to Renilla luciferase; error bars represent a 95% c.i. The differences between the core promoter alone and all five MCM6 intronic constructs, as well as between the three derived versus two ancestral haplotypes, were significant (P < 0.0008, paired t tests). There was no significant difference in expression between the empty vector and the core promoter, between the two ancestral haplotypes (with and without the T-13495 allele) or between the three derived haplotypes. The construct with ancestral lactase persistence–associated alleles that differed at T-13495 served as an internal control for the expression differences for the G-13907 and T-13495 alleles, indicating that only the G-13907 allele results in increased gene expression.

Notably, we also observed differences in expression between the five MCM6 intron 13 haplotypes that were functionally tested using the dual-luciferase reporter assay (Fig. 5). The C-14010–, G-13915– and G-13907–derived haplotypes consistently drove higher expression (from ~18%-30%) than the haplotypes with the ancestral alleles. There was no statistically significant difference in expression between the constructs with the C-14010, G-13907/T-13495 and G-13915 alleles.

Evidence for positive selection of the C-14010 allele

If a mutation provides a large enough benefit to its carriers (in this case, the ability to digest milk as adults), resulting in more viable offspring, it is expected to rise rapidly to high frequency in the population, together with linked variants (that is, genetic hitchhiking)25. Under neutrality, one expects common mutations to be older and to have lower levels of LD with flanking markers. In contrast, one of the genetic signatures of an incomplete selective sweep is a region of extensive LD (termed extended haplotype homozygosity or EHH) and low variation on high-frequency chromosomes carrying the derived beneficial mutation relative to chromosomes with the ancestral allele17,26. Over time, this pattern will degrade owing to recombination and newly occurring mutations. Thus, by measuring the frequency of the haplotype and extent of LD in the region, it is possible to estimate the age and strength of a beneficial mutation.

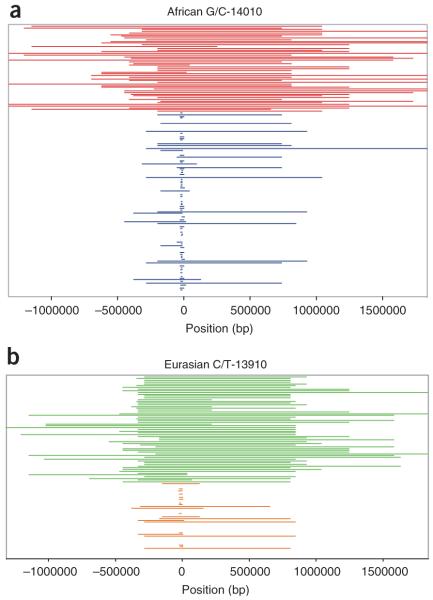

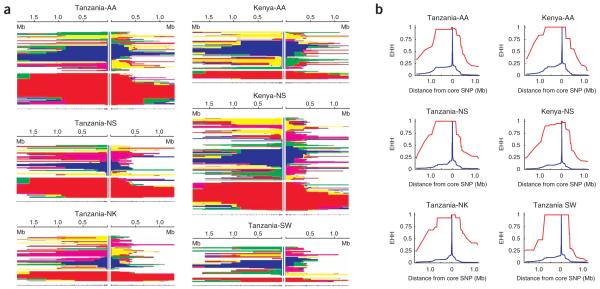

In order to visually assess the evidence for selection on chromosomes with the C-14010 allele, we constructed plots depicting EHH for ancestral (G) and derived (C) alleles using both unphased data (Fig. 6), as well as phase-inferred data (Fig. 7). For the unphased data, we plotted continuous homozygosity at each of the 123 genotyped SNPs for individuals homozygous for the ancestral (G/G-14010) and derived (C/C-14010) alleles (Fig. 6a). For comparison, we plotted EHH for the 101 SNPs genotyped in Eurasians14 for individuals homozygous for the ancestral (C/C-13910) and derived (T/T-13910) lactase persistence–associated alleles (Fig. 6b). The average homozygous tract length in C/C-14010 homozygotes (n = 51) was 1.8 Mb (with a maximum of 3.15 Mb), compared with 1,800 bp in G/G-14010 homozygotes (n = 228). In Eurasians, the average homozygous tract length in T/T-13910 homozygotes (n = 61) was 1.4 Mb (with a maximum of 2.1 Mb), compared with 1,900 bp in C/C-13910 homozygotes (n = 38). We observed a similar result in the individual African populations using phase-inferred data, with EHH extending as far as 2.18-2.90 Mb (1.6-2.2 cM) (Table 1 and Fig. 7). Chromosomes with the G-13907 and G-13915 alleles show EHH spanning ~1.4 Mb (0.56 cM) and 1.1 Mb (0.37 cM), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2 online).

Figure 6.

Comparison of tracts of homozygous genotypes flanking the lactase persistence–associated SNPs. (a) Kenyan and Tanzanian C-14010 lactase-persistent (red) and non-persistent G-14010 (blue) homozygosity tracts. (b) European and Asian T-13910 lactase-persistent (green) and C-13910 non-persistent (orange) homozygosity tracts, based on the data from ref. 14. Positions are relative to the start codon of LCT. Note that some tracks are too short to be visible as plotted.

Figure 7.

Plots of the extent and decay of haplotype homozygosity in the region surrounding the C-14010 allele. (a) Decay of haplotypes for the C-14010 allele in African subpopulations. Horizontal lines are haplotypes; SNP positions are marked below the haplotype plot. These plots are divided into two parts: the upper portion shows haplotypes with the ancestral G allele at site -14010 (blue), and the lower portion shows haplotypes with the derived C allele at -14010 (red). For a given SNP, adjacent haplotypes with the same color carry identical genotypes everywhere between that SNP and the central (selected) site. The left- and right-hand sides are sorted separately. Haplotypes are no longer plotted beyond the points at which they become unique. Note the large extent of haplotype homozygosity surrounding the C-14010 allele (red) extending as far as 2.9 Mb in individual populations, which is consistent with the action of positive selection rapidly increasing the frequency of chromosomes with the C-14010 allele. (b) Decay of extended haplotype homozygosity for the C-14010 allele in African subpopulations over physical distance. In each case, the decay of haplotype homozygosity for the ancestral allele (blue) occurs much more quickly than for the derived allele (red). This is the expectation for strong positive selection acting on haplotypes containing this derived allele. AA: Afro-Asiatic language family; NK: Niger-Kordofanian; NS: Nilo-Saharan; SW: Sandawe.

Table 1. EHH statistics and estimates of age of the C-14010 allele and selection coefficients.

| Dominant model |

Additive model |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Sample size (n) | Frequency (C-14010) | iHS | P (simulated) | P (empirical) | Span (cM) | Span (Mb) | s (95% c.i.) | Age (years) (95% c.i.) | s (95% c.i.) | Age (years) (95% c.i.) |

| Kenya-Afro-Asiatic | 64 | 0.180 | −0.79 | 0.204 | 0.043 | 2.17 | 2.73 | 0.070 (0.022-0.142) |

2,966 (1,215-6,827) |

0.095 (0.033-0.146) |

3,764 (1,970-8,036) |

| Kenya-Nilo-Saharan | 128 | 0.316 | −2.80 | 0.002 | 0.00013 | 1.64 | 2.27 | 0.035 (0.008-0.080) |

6,925 (2,232-18,496) |

0.067 (0.020-0.137) |

6,167 (2,478-14,785) |

| Tanzania-Afro-Asiatic | 99 | 0.449 | −2.78 | <0.001 | 0.0012 | 2.02 | 2.53 | 0.053 (0.018-0.130) |

5,956 (1,575-13,054) |

0.072 (0.024-0.138) |

6,591 (2,819-16,072) |

| Tanzania-Nilo-Saharan | 47 | 0.394 | −2.85 | <0.001 | 0.00059 | 2.07 | 2.78 | 0.070 (0.023-0.143) |

3,757 (1,344-9,087) |

0.097 (0.040-0.145) |

4,358 (2,609-9,476) |

| Tanzania-Niger- Kordofanian |

61 | 0.230 | −2.61 | <0.003 | 0.00032 | 2.22 | 2.90 | 0.077 (0.026-0.142) |

2,778 (1,219-6,049) |

0.097 (0.036-0.148) |

4,075 (2,304-9,533) |

| Tanzania-Sandawe | 18 | 0.129 | −1.19 | 0.112 | 0.024 | 1.60 | 2.18 | 0.043 (0.005-0.132) |

5,717 (1,296-17,971) |

0.060 (0.007-0.135) |

6,899 (2,050-23,291) |

| European | 48 | 0.76 | −3.86 | <0.001 | N/A | 1.58 | 2.15 | 0.039 (0.012-0.107) |

9,323 (2,231-19,228) |

0.069 (0.025-0.132) |

7,998 (3,466-18,191) |

The European data are from ref. 14. iHS: standardized integrated haplotype score (iHS) for C-14010; P simulated: P value for the iHS score from simulations; P empirical: empirical P value for the iHS score using the observed iHS scores at the specified derived allele frequency for the HapMap Yoruba sample; cM and Mb span: assuming the position where the probability of haplotype identity is 0.25; s: selection intensity (estimated from simulation), assuming an effective population size of 10,000.

The high frequency of the C-14010 allele and the very long stretch of homozygosity (>2 Mb) for haplotypes containing the C-14010 allele are consistent with the action of positive selection elevating this allele and the surrounding linked variation to high frequency. To test the neutrality of this SNP, we used a modification of the EHH test26, the integrated haplotype score (iHS)17 (sample sizes for G-13915 and G-13907 alleles were too small for sufficient power with the iHS test). For most populations, the iHS score was statistically more extreme relative to iHS scores for data simulated both under a neutral model with constant population size (P < 0.002) and under an assortment of demographic population expansion and contraction models (Supplementary Table 3 online). All populations had statistically more extreme scores relative to the empirical distribution of iHS scores observed in the Yoruban HapMap data, for alleles at matching frequency (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Furthermore, as predicted, the direction of the score was consistent with the action of positive selection on the lactase persistence–associated haplotype.

Age of variants and estimates of selection coefficients

We estimated the age of the C-14010 allele using coalescent simulations under a model incorporating selection and recombination27. The simulations assumed either an additive (h = 0.5) or dominant (h = 1) model for fitness (Supplementary Methods online) and were designed to match several aspects of the data, including SNP ascertainment and density, allele frequency, sample size, recombination profile and phase uncertainty17. We estimated selection intensity and ages by matching simulated data to the observed cM span and the observed frequency of the derived allele in each population. We estimated these values (Table 1) and found extremely recent (within the last ~3,000-7,000 years; confidence interval (c.i.) 1,200-23,200 years ago) and strong (s = 0.04-0.097, c.i. 0.01-0.15) positive selection in many African populations.

DISCUSSION

Role of G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907 in LCT expression

Although we cannot rule out the possibility that G/C-14010 is in LD with another causative SNP, our data suggest that G/C-14010 regulates LCT gene expression. First, this SNP shows significant statistical association with the LTT phenotype in Kenyan and Tanzanian populations (Fig. 3). Although most individuals with a C-14010 allele have moderate to high increases in blood glucose (mean of 2.04 and 2.45 mM in heterozygotes and homozygotes, respectively; Fig. 2b), many individuals who are homozygous for the ancestral G-14010 allele are also LIP or lactase persistent (Fig. 3), probably because of genetic heterogeneity of this trait, as discussed further below. Additionally, there is likely to be phenotype measurement error due to working in field conditions and to the relative insensitivity of the LTT test (see Methods). Also, individuals with the C-14010 allele may be classified as LNP if they have had damage to intestinal cells caused by infectious disease21.

Second, we observe extensive LD on chromosomes with the C-14010 allele, with haplotype homozygosity extending >2 Mb (Figs. 6 and 7). Of the 123 SNPs genotyped, high LD (D’ > 0.9, LOD score ≥ 2) extends farthest for SNP G/C-14010 (Supplementary Fig. 3 online) and is inconsistent with demographic models that incorporate even extreme bottlenecks. In fact, this region of haplotype identity, spanning 2.18-2.9 Mb (1.6-2.2 cM), is more extensive than any span of identity derived from HapMap data from global populations16,17. These results suggest that chromosomes with the C-14010 allele have rapidly risen to high frequency in East African populations owing to strong positive selection, consistent with a functional role of this variant. Last, analyses of transcriptional regulation of the LCT promoter in vitro indicate that otherwise identical constructs with a C-14010 allele consistently produce ~18% more luciferase than constructs with the G-14010 allele (Fig. 5), an increase in transcription similar to that observed for the T-13910 allele in Europeans10,11 (Supplementary Discussion online).

We have also identified two additional variants, G-13907 and G-13915, at ≥5% frequency only in the Afro-Asiatic–speaking Beja from Sudan and in Afro-Asiatic–speaking Kenyans, that are on haplotype backgrounds that increase gene expression by ~18%-30% compared with the ancestral haplotypes (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Discussion). Although SNPs T/G-13915 and C/G-13907 are associated with a mean rise in blood glucose of 3.18 and 3.99 mM in heterozygotes, respectively (Fig. 2b), these associations are not significant in the subpopulations or in the meta-analysis (Fig. 3), possibly because of small sample size and loss of power for these SNPs. Additionally, chromosomes with the G-13907 and G-13915 alleles show EHH spanning ~1.4 Mb and ~1.1 Mb, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although these results suggest that G-13915 and G-13907 are probable candidate LCT regulatory mutations, larger sample sizes from populations containing these alleles are required to test for an association with the lactase persistence trait and to rule out the possibility that they are simply in LD with a different causal SNP. Identification of transcription factors that bind to the sites of the C-14010, T-13915 and G-13907 variants would also be informative for clarifying the possible role of these variants in regulating LCT expression.

Adaptive significance and the origins of pastoralism

Archeological evidence suggests that cattle domestication originated in southern Egypt as early as ~9,000 years ago but no later than ~7,700 years ago and in the Middle East ~7,000-8,000 years ago28, consistent with the age estimate of ~8,000-9,000 years (95% c.i. ~2,200-19,200 years) for the T-13910 allele in Europeans. The more recent age estimate of the C-14010 allele in African populations, ~2,700-6,800 years (95% c.i. ~1,200-23,000 years), is consistent with archeological data indicating that pastoralism did not spread south of the Sahara and into northern Kenya until ~4,500 years ago and into southern Kenya and northern Tanzania ~3,300 years ago28,29. The ability to digest milk as adults is likely to be adaptive owing to the increased nutritional benefits from milk (carbohydrates as well as fat, protein and calcium) and also because milk is an important source of water in arid regions2,28,30,31. Considering the symptoms of lactose intolerance, which includes water loss from diarrhea, individuals who had the lactase persistence–associated alleles and could tolerate milk could have had a very strong selective advantage2. This is supported by our high estimates for the selection coefficient (s = 0.035-0.097). Because the selective force, adult milk consumption, is associated with the cultural development of cattle domestication, the recent and rapid spread of the lactase persistence–associated alleles, together with the practice of pastoralism in East Africa, is an excellent example of ongoing adaptation in humans32 and coevolution of genes and culture3.

We observe the oldest age estimates of the C-14010 allele, ~6,000-7,000 years (95% c.i. ~2,000-16,000 years), in the Kenyan Nilo-Saharan and Tanzanian Afro-Asiatic populations (Table 1). We also observe an old age estimate in the Tanzanian Sandawe, but its low frequency suggests it was introduced via recent gene flow (Supplementary Discussion). However, we cannot distinguish with certainty whether this allele first arose in the Cushitic-speaking Afro-Asiatic populations, who are thought to have migrated into Kenya and Tanzania from Ethiopia ~5,000 years ago33 and practice a mixture of agriculture and pastoralism, or in the Nilotic-speaking Nilo-Saharan populations, who are thought to have migrated into Kenya and Tanzania from southern Sudan within the past ~3,000 years33 and are strict pastoralists28. These results are consistent with both linguistic34 and genetic data (F.A.R. and S.A.T., unpublished data) indicating cultural exchange and genetic admixture between these groups. The absence of C-14010 in the southern Sudanese Nilo-Saharan–speaking populations suggests that this allele either originated in or was introduced to the Kenyan Nilo-Saharan populations after their migration from southern Sudan. Regardless of the population origins of the C-14010 allele, it spread rapidly throughout the region along with the cultural practice of pastoralism, consistent with a demic diffusion model of genetic and cultural expansion35.

Implications for identifying disease-associated variants

It has been hypothesized that genetic variants associated with both mendelian diseases (such as sickle cell anemia and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency) and common complex diseases (such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and asthma) may be at high frequency in modern populations because they were adaptive in ancient environments16,17,36-38. Thus, identification of loci that are targets of natural selection could be informative for identifying disease-risk alleles. The rapid increase in frequency of geographically restricted lactase persistence–associated alleles is an example of local adaptation that would have been missed by studying other African populations, such as the Yoruba, which do not show a signature of selection at LCT in the HapMap data set16,17. Because of the possibility that disease-associated alleles may also be geographically restricted owing to recent, local adaptation, these results suggest the importance of resequencing analyses in multiple populations, even from within a single geographic region such as Africa.

Our study also indicates how challenging it may be to identify alleles that are targets of selection. Networks of the 98-kb region encompassing the LCT and MCM6 genes (Fig. 4) indicate several haplotypes that are at high frequency in global populations and that have ancestral alleles at the lactase persistence–associated SNPs (that is, haplotypes D and E) (Fig. 4). Based on a single-factor ANOVA test, neither of these haplotypes is significantly associated with the lactase persistence phenotype (P = 0.20 and P = 0.058, respectively). The only difference between lactase persistence–associated haplotype F and the ancestral haplotype E is the single G→C substitution at position 14010. The presence of these globally common haplotypes that are identical over at least 98 kb raises the possibility that there have been additional selective sweeps in the LCT-MCM6 gene region, possibly unrelated to LCT gene expression and confounding the haplotype-based inference of selection at LCT (Supplementary Discussion).

Convergent evolution of LP-associated variants

These data suggest that at least two, and probably four or more, distinct causal variants associated with lactase persistence (T-13910 in Europeans and C-14010, G-13907 and G-13915 in Africans) have evolved independently in European and African populations owing to convergent evolution in response to a strong selective force, adult milk consumption. These variants arose on highly divergent haplotype backgrounds that are geographically restricted (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Discussion), but they do not account for all of the phenotypic variation, particularly in the Nilo-Saharan Sudanese and Hadza (Fig. 2). Therefore, it is likely that there are additional lactase persistence–associated variants in Africans.

Notably, the Hadza population of Tanzania, who speak a click language and subsist by hunting and gathering, have the lactase persistence phenotype at ~50% frequency (Fig. 2a), suggesting that either the Hadza descend from a pastoralist population or that the lactase persistence trait may be adaptive for something other than milk digestion (Supplementary Discussion). These results, which should be confirmed in a larger sample, add to the mystery of the origins of the Hadza and their relationship to other click-speaking populations in Africa.

In conclusion, multiple independent variants have allowed various human populations to quickly modify LCT expression and have been strongly adaptive in adult milk-consuming populations, emphasizing the importance of regulatory mutations in recent human evolution39. Further resequencing and genotype-phenotype analyses in Africa, particularly in populations that lack the C-14010 allele, will be necessary for identifying additional lactase persistence–associated variants. Once these variants are identified, genotype analyses in a broader set of African populations will be informative for reconstructing an even more complete history of adaptation to pastoralism in Africa.

METHODS

DNA samples

Tanzanian DNA samples were collected from individuals residing in the Arusha and Dodoma provinces of Tanzania. Kenyan samples were collected in the Rift Valley, Nyanza and Eastern provinces of Kenya. Sudanese samples were collected in the Khartoum and Kasala provinces of the Sudan. Institutional Review Board approval for this project was obtained from the University of Maryland at College Park. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and research permits from the Tanzanian Commission for Science and Technology, Tanzanian National Institute for Medical Research, the Kenya Medical Research Institute and the University of Khartoum were obtained prior to sample collection. Samples were grouped according to self-identified ethnolinguistic ancestry from unrelated individuals. Ethnic groups, number of individuals sampled, language classification and subsistence classification are given in Supplementary Table 1. White cells were isolated in the field from whole blood using a modified salting-out procedure40, and DNA was extracted in the laboratory using a Purgene DNA extraction kit (Gentra).

Phenotype test

The LTT measures elevation in blood glucose levels after consumption of 50 g of lactose (equivalent to ~1-2 l of cow’s milk)21. Blood was obtained via a finger prick and baseline glucose levels were measured by an Accucheck Advantage glucose monitor and Accucheck Comfort Strips (Roche). Blood glucose levels were obtained 20, 40 and 60 min after consumption of 50 g of lactose (Quintron) dissolved in 250 ml water. Based on manufacturer recommendation, glucose values were adjusted based on previously determined error associated with use of the Comfort Strip Curves according to the following regression equation: y = 0.985x – 7.5, where x is the measured glucose value. We determined the maximum rise in glucose level compared with baseline values. We used the following definitions to classify individuals: an individual with a rise of >1.7 mM was classified as ‘lactase persistent’; one with a rise of <1.1 mM was classified as ‘lactase non-persistent’ and one with a rise of 1.1-1.7 mM was considered ambiguous and classified as ‘lactase intermediate persistent’21. There is likely to be some error in phenotype classification owing to administration of the test under field conditions. The LTT test is less reliable than determining lactase enzyme activity directly by intestinal biopsy2,21, with a false negative rate (that is, lactase-persistent individuals being misclassified as LNP) as high as 23%-30% (ref. 21). Although more accurate indirect tests exist (such as determination of urinary galactose after inclusion of ethanol with the lactose load or a hydrogen breath test21), these were not feasible in remote locations in Africa. In addition, we were not able to ensure that participants had fasted for at least 8 h prior to administration of the test, as recommended in clinical settings2, although most participants indicated that they had not eaten for at least several hours prior to testing (Supplementary Methods).

Sequence analysis

A 3,314-bp region encompassing intron 13 of MCM6 and a 1,761-bp region encompassing intron 9 were amplified by PCR (Fig. 1c,d) in 110 individuals (69 lactase-persistent and 40 LNP): 16 lactase-persistent and 10 LNP from Sudan, 36 lactase-persistent and 17 LNP from Kenya and 17 lactase-persistent and 14 LNP from Tanzania (primers and PCR conditions are given in Supplementary Methods). PCR products were prepared for sequencing with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I (US Biochemicals). All nucleotide sequence data were obtained using the ABI Big Dye v3.1 terminator kit and 3730xl automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence files were aligned and SNPs identified using Sequencher software (v. 4.0.5; GeneCodes).

SNP genotyping

We selected 146 SNPs for genotyping from ref. 14, dbSNP and the resequencing of introns 9 and 13 of MCM6 in the individuals listed above. All SNPs were genotyped in 494 samples. Following ref. 14, the SNPs were chosen to represent a large area on chromosome 2 but with increased density in the LCT and MCM6 gene regions (Fig. 1a). SNPs were also included that had previously been shown to be associated with lactase persistence in Europeans (C/T-13910 and G/A-22018) or that seemed to be associated with lactase persistence based on the initial resequencing screen described above. SNP assays were designed with SpectroDESIGNER software (Sequenom). SNP typing was performed with the Homogeneous Mass Extend assay (Sequenom) as described elsewhere41. Genotyping was carried out at a multiplex level of up to ten SNPs per well, and data quality was assessed by duplicate DNAs (n = 7 in triplicate). SNPs with more than one discrepant call or those showing self-priming in the negative control (water) were removed. Finally, we removed SNPs with call rates below 70% and flagged markers that departed from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P < 0.001). A total of 123 SNPs (of which seven were monomorphic) passed quality control and were included in the final analysis; these included 79 SNPs from ref. 14, 34 SNPs from dbSNP and ten SNPs from resequencing (five from intron 9 and five from intron 13) (Supplementary Table 2).

Genotype-phenotype association tests

We determined genotype-phenotype association for data binned into lactase-persistent, LNP and LIP classifications using a χ2 test. The degrees of freedom for the χ2 test are calculated as (number of phenotypes − 1) × (number of genotypes − 1). In cases where there were low expected cell counts (<5), cells were pooled to satisfy Cochran’s guidelines42. Because the phenotype (rise in blood glucose) is a continuous trait, we also used a least-squares linear regression approach to test for significant genotype-phenotype associations24. This method avoids the loss of information that may arise from binning the phenotype into discrete categories. For each SNP, different homozygotes were assigned to values of 0 or 1, and heterozygotes were assigned an intermediate genotype value of 0.5 (assuming an additive model). Next, a linear regression was fit to the x-axis genotype values and y-axis phenotypes (rise in glucose). The resulting r2 and P values were recorded as measures of the degree of association. Because of the large amount of multiple testing (123 SNPs), a significant association was determined after applying a conservative Bonferroni P-value correction.

Combined population meta-analysis

In order to both gain statistical power and avoid the issues of population stratification, we conducted a meta-analysis on the results of the association tests in the individual geographic-linguistic populations. This was done by combining the P values for each SNP over k populations in an unweighted Z transform test according to the following equation43:

where Zi is the Z score of the standard normal curve corresponding to the P value from an individual population phenotype-genotype regression, and Zmeta is the Z score for the combined meta-analysis. This method tests for a skew in the overall distribution of P values (from tests in individual populations) regardless of the significance of any individual test and allows us to regain some of the power that was lost by dividing the data into smaller groups.

ANOVA

A single-factor ANOVA was used to test for a significant difference in phenotypes between the two common haplotypes (D and E) in the LCT-MCM6 region (Fig. 4a) and all other haplotypes, after individuals carrying a C-14010 and/or a G-13907 and/or a G-13915 allele (or unknown genotypes at any of these three markers) had been removed. An ANOVA was also used to quantify the overall variation in phenotype measures explained by G/C-14010, T/G-13915 and C/G-13907; each of the ten compound genotypes found in the data set was treated as a category.

Homozygosity plots

To visualize the extent of homozygosity on chromosomes with the lactase persistence–associated alleles, individuals that were homozygous for the ancestral and derived alleles at G/C-14010 and C/T-13910 SNPs were selected and the extent of continuous homozygosity at each assayed SNP, in each direction, was plotted. Note that this is the actual measured homozygosity and thus is independent of haplotype phase estimation but sensitive to inbreeding.

Haplotype phase estimation

fastPHASE44 was used, with population label information, in order to estimate phased haplotype backgrounds.

Calculation of iHS scores

We calculated iHS scores as in ref. 17 for each subpopulation for all SNPs in the region. In calculating the scores, we used an interpolated recombination map estimated from the HapMap project Yoruba data set16. iHS scores were standardized using estimates of the mean and s.d. obtained via coalescent simulation under a variety of demographic models. These simulations were tailored to match the frequency spectrum, SNP density and recombination profile of the observed data. Alternative demographic models included either exponential growth or a bottleneck (which varied in onset, severity, duration and population size recovery after the bottleneck). We simulated 1,000 repetitions of each demographic model and calculated the distribution of iHS scores for sites matching the frequency (within 2.5%) as well as position of C-14010. Supplementary Table 3 contains a description of the demographic models (and results) and also gives empirical P-values that count the number of simulated iHS scores for each model that exceeded (that is, were more negative than) the observed iHS statistic. In addition, iHS scores were standardized empirically by comparison with the Yoruba HapMap data for alleles at the same frequency as C-14010.

Estimating selection intensity and sweep ages

We applied a rejectionsampling approach using the cM span surrounding the selected site to estimate selection intensity and ages of the candidate lactase persistence–associated mutations for each population45 (Supplementary Methods). Point estimates for the selection intensity and ages are presented, assuming an additive or fully dominant fitness effect. Although our model assumes constant population size, previous studies have demonstrated that for an allele that rapidly increases in frequency, population demographic history has only a modest effect on allele age estimates38,46.

Because of the way that SNPs were ascertained, the allele frequency spectrum departs from the expectation for DNA sequence data. To model the effect of ascertainment bias of SNPs selected for genotyping, we followed the approach in ref. 17 (Supplementary Methods). In addition, the observed data vary in SNP density, showing a dense central core region flanked by regions with lower SNP density (on average). To match this feature of the data, a secondary rejection step was applied such that the average SNP density for central and flanking regions (both left and right) matched the observed density. With respect to recombination, for each simulation we chose to exactly match the recombination map estimated from the data using the Li and Stephens algorithm47. For all populations, we calculated cM spans assuming the estimated population genetic map for the Yoruba HapMap data set16 and calculated those distances assuming the rates estimated from the deCODE genetic map48 across 40 Mb flanking this region on chromosome 2.

Network analyses

Haplotype networks were generated using the median-joining algorithm of Network 4.1.1.1 (ref. 49) for SNPs within the LCT and MCM6 gene regions from rs1042712 to rs309125, spanning 98 kb. The root was inferred assuming the chimpanzee allelic state at each SNP is ancestral.

Vector construction, transfection and expression assay

The LCT ‘core’ promoter, starting 3,083 bp upstream of LCT at position −3 of the transcription start site, was amplified by PCR using high-fidelity Phusion polymerase (Finnzyme). PCR products were then cloned and ligated into a pGL3-basic luciferase reporter (Promega). Constructs including intron 13 of MCM6 were assembled by cloning 2,035 bp, beginning at position −14354 relative to LCT, 5′ of the ‘core’ promoter. Caco-2 cells were then transfected with these constructs. We lysed cells 48 h after transfection and measured luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and a Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Turner BioSystems). Transfections of cells were performed six times for control and ‘core’ promoters and 12 times for vectors with the intron from MCM6. The expression data were analyzed using paired t tests (Supplementary Methods).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Panchapakesan, E. King, S. Morrow and T. Severson for technical assistance. We thank E. Sibley and L.C. Olds for sharing advice and materials and T. Bersaglieri and J. Hirschhorn for sharing data. We thank S.J. Deo, P. Lufungulo, W. Ntandu, A. Mabulla, J.L. Mountain, J. Hanby, D. Bygott, A. Tibwitta, D. Kariuki, L. Alando, E. Aluvala, F. Mohammed, A. Teia and A.A. Mohamed for their assistance with sample collection. We thank A. Clark for critical review of the manuscript and for helpful suggestions and we thank L. Peltonen, N. Enattah and C. Ehret for discussion. We thank the African participants who generously donated DNA and phenotype information so that we might learn more about their population history and the genetic basis of lactase persistence in Africa. This study was funded by L.S.B. Leakey and Wenner Gren Foundation grants, US National Science Foundation (NSF) grants BSC-0196183 and BSC-0552486, US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01GM076637 and David and Lucile Packard and Burroughs Wellcome Foundation Career Awards to S.A.T. K.P. and H.M.M. were funded by NSF grant IGERT-9987590 to S.A.T. F.A.R. was supported by US National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant F32HG03801. B.F.V. and J.K.P. were supported by NIH grant HG002772-1. The Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy of Duke University supported the work of C.C.B., J.S.S. and G.A.W. The Wellcome Trust supported the work of J.G., S.B. and P.D.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.A.T. conceived and supervised the study. S.A.T., K.P., H.M.M., A.R., J.B.H., M.O., M.I., S.A.O., G.L. and T.B.N. were involved in DNA collection and phenotype testing. A.R. performed the resequencing and initial identification of association of candidate SNPs with the phenotype. S.A.T. and F.A.R. selected the SNPs to be genotyped and samples to test for gene expression. P.D., J.G. and S.B. performed the SNP design and genotyping. F.A.R. processed and phased the raw data and performed the genotype-phenotype association analyses, plots of haplotype homozygosity from unphased data, dominance estimates and pairwise plot of LD. B.F.V. performed, and J.K.P. co-supervised, the iHS test to detect positive selection and plots of haplotype homozygosity from phased data as well as rejection-sampling analyses to estimate age of alleles and selection parameters. H.M.M. constructed the haplotype networks. C.C.B., J.S.S. and G.A.W. built the expression constructs, carried out transcription assays and analyzed the results of expression assays. The paper was written primarily by S.A.T., with contributions from F.A.R., B.F.V., J.K.P., C.C.B., G.A.W. and P.D. The supplementary information was written by S.A.T. and F.A.R. with contributions from B.F.V., J.K.P., C.C.B., G.A.W. and P.D.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Published online at http://www.nature.com/naturegenetics/

Reprints and permissions information is available online at Published online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Genetics website.

References

- 1.Swallow DM. Genetics of lactase persistence and lactose intolerance. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2003;37:197–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollox E, Swallow DM. In: The Genetic Basis of Common Diseases. King RA, Rotter JI, Motulsky AG, editors. Oxford Univ. Press; Oxford: 2002. pp. 250–265. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durham WH. Coevolution: Genes, Culture, and Human Diversity. Stanford University Press; Stanford, California: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Enattah NS, et al. Identification of a variant associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:233–237. doi: 10.1038/ng826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, et al. The lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is controlled by a cis-acting element. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995;4:657–662. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulter M, et al. The causal element for the lactase persistence/non-persistence polymorphism is located in a 1 Mb region of linkage disequilibrium in Europeans. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2003;67:298–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogenauer C, et al. Evaluation of a new DNA test compared with the lactose hydrogen breath test for the diagnosis of lactase non-persistence. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005;17:371–376. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200503000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridefelt P, Hakansson LD. Lactose intolerance: lactose tolerance test versus genotyping. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005;40:822–826. doi: 10.1080/00365520510015764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuokkanen M, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the lactase-phlorizin hydrolase gene by polymorphisms associated with adult-type hypolactasia. Gut. 2003;52:647–652. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olds LC, Sibley E. Lactase persistence DNA variant enhances lactase promoter activity in vitro: functional role as a cis regulatory element. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:2333–2340. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Troelsen JT, Olsen J, Moller J, Sjostrom H. An upstream polymorphism associated with lactase persistence has increased enhancer activity. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1686–1694. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewinsky RH, et al. T-13910 DNA variant associated with lactase persistence interacts with Oct-1 and stimulates lactase promoter activity in vitro. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:3945–3953. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollox EJ, et al. Lactase haplotype diversity in the Old World. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:160–172. doi: 10.1086/316924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bersaglieri T, et al. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:1111–1120. doi: 10.1086/421051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myles S, et al. Genetic evidence in support of a shared Eurasian-North African dairying origin. Hum. Genet. 2005;117:34–42. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The International HapMap Consortium A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320. doi: 10.1038/nature04226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voight BF, Kudaravalli S, Wen X, Pritchard JK. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e72. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nielsen R, et al. A scan for positively selected genes in the genomes of humans and chimpanzees. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulcare CA, et al. The T allele of a single-nucleotide polymorphism 13.9 kb upstream of the lactase gene (LCT) (C-13.9kbT) does not predict or cause the lactase-persistence phenotype in Africans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:1102–1110. doi: 10.1086/421050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coelho M, et al. Microsatellite variation and evolution of human lactase persistence. Hum. Genet. 2005;117:329–339. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1322-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arola H. Diagnosis of hypolactasia and lactose malabsorption. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1994;202:26–35. doi: 10.3109/00365529409091742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Rosenberg NA, Donnelly P. Association mapping in structured populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;67:170–181. doi: 10.1086/302959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed FA, Reeves RG, Aquadro CF. Evidence of susceptibility and resistance to cryptic X-linked meiotic drive in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution Int. J. Org. Evolution. 2005;59:1280–1291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung VG, et al. Mapping determinants of human gene expression by regional and genome-wide association. Nature. 2005;437:1365–1369. doi: 10.1038/nature04244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maynard-Smith J, Haigh J. The hitch-hiking effect of a favourable gene. Genet. Res. 1974;23:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabeti PC, et al. Detecting recent positive selection in the human genome from haplotype structure. Nature. 2002;419:832–837. doi: 10.1038/nature01140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spencer CC, Coop G. SelSim: a program to simulate population genetic data with natural selection and recombination. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3673–3675. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gifford-Gonzalez D. In: African Archeology. Stahl AB, editor. Blackwell; London: 2005. pp. 187–224. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrose S. Chronology of the Later Stone Age and food production in East Africa. J. Arch. Sci. 1998;25:377–391. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simoons FJ. The geographic hypothesis and lactose malabsorption. A weighing of the evidence. Am. J. Dig. Dis. 1978;23:963–980. doi: 10.1007/BF01263095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook GC. Did persistence of intestinal lactase into adult life originate in the Arabian peninsula? Man. 1978;13:418–427. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed FA, Aquadro CF. Mutation, selection and the future of human evolution. Trends Genet. 2006;22:479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman J. The Peopling of Africa. Yale Univ. Press; New Haven and London: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ehret C. Memoire 8: Nairobi. In: Mack J, Robertshaw P, editors. Culture History in the Southern Sudan. British Institute in Eastern Africa; Nairobi, Kenya: 1983. pp. 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavalli-Sforza LL, Piazza A, Menozzi P. History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton Univ. Press; Princeton, New Jersey: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tishkoff SA, Verrelli BC. Patterns of human genetic diversity: implications for human evolutionary history and disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2003;4:293–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Rienzo A, Hudson RR. An evolutionary framework for common diseases: the ancestral-susceptibility model. Trends Genet. 2005;21:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tishkoff SA, et al. Haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium at human G6PD: recent origin of alleles that confer malarial resistance. Science. 2001;293:455–462. doi: 10.1126/science.1061573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wray GA, et al. The evolution of transcriptional regulation in eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:1377–1419. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whittaker P, Bumpstead S, Downes K, Ghori J, Deloukas P. In: Cell Biology: a Laboratory Handbook. Celis J, editor. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cochran WG. Some methods for strengthening the common chi-square test. Biometrics. 1954;10:417–451. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stouffer SA, Suchman EA, DeVinney LC, Star SA, Williams RM. The American Soldier: Adjustment During Army Life. Vol. 1. Princeton Univ. Press; Princeton, New Jersey: 1949. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scheet P, Stephens M. A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;78:629–644. doi: 10.1086/502802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pritchard JK, Seielstad MT, Perez-Lezaun A, Feldman MW. Population growth of human Y chromosomes: a study of Y chromosome microsatellites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1791–1798. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiuf C. Recombination in human mitochondrial DNA? Genetics. 2001;159:749–756. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.2.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li N, Stephens M. Modeling linkage disequilibrium and identifying recombination hotspots using single-nucleotide polymorphism data. Genetics. 2003;165:2213–2233. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong A, et al. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ng917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bandelt H, Forster P, Rohl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.