Abstract

Mesenteric lymphangiomas are rare abdominal masses that are seldom associated with small bowel volvulus, and especially in adult patients. We report here on an unusual case of small bowel volvulus that was induced by a mesenteric lymphangioma in a 43-year-old man who suffered from repeated bouts of abdominal pain. At multidetector CT, we noticed whirling of the cystic mesenteric mass and the adjacent small bowel around the superior mesenteric artery. Small bowel volvulus induced by the rotation of the mesenteric lymphangioma was found on exploratory laparotomy. Lymphangioma should be considered as a rare cause of small bowel volvulus in adult patients.

Keywords: Volvulus, Small intestine, Lymphangioma, Multi-detector CT

Lymphangioma arising from the abdomen is a rare tumor, and especially in adult patients. Abdominal lymphangiomas usually manifest as a palpable abdominal mass or as abdominal distension. They are seen as multilocular cystic masses with thin septa on imaging studies (1). Small bowel volvulus is a condition in which there is torsion of the small bowel and its mesentery. Among infants and children, it is a well recognized disease that is often complicated with intestinal obstruction; however it appears to be a rare disease in adults (2). The conditions that predispose a person to volvulus include adhesive bands, an ileostomy, partial malrotation, a mesenteric or omental defect and Meckel's diverticulum (3). To the best of our knowledge, there are a few reports about small bowel volvulus induced by a mesenteric lymphangioma in adult patients, but the multidetector CT (MDCT) findings are not well known (4, 5). We report here on the MDCT finding of small bowel volvulus that was induced by a mesenteric lymphangioma in an adult.

CASE REPORT

A 43-year-old man visited the emergency room with epigastric pain. According to the patient, he had no significant medical or surgical history, except for hospitalization 20 years ago due to similar abdominal pain that resolved with conservative treatment. The patient's vital signs were stable and mild tenderness was noted on the epigastric area. The bowel gas pattern was non-specific on the initial plain radiographs. The abdominal CT scan was performed with using a 16 row detector CT (Sensation16, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at the portal phase after administering intravenous iodinated contrast agent (Ultravist 300, Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin, Germany). We obtained the axial and coronal reformatted images that were 5 mm thick. A well-demarcated lesion approximately 15×10×6 cm in size with homogeneous fluid attenuation was noted in the pelvic cavity. The lesion was located within the rectovesical pouch, and it mimicked peritoneal inclusion cysts or loculated ascites. The abdominal pain subsided with conservative therapy and the patient was discharged.

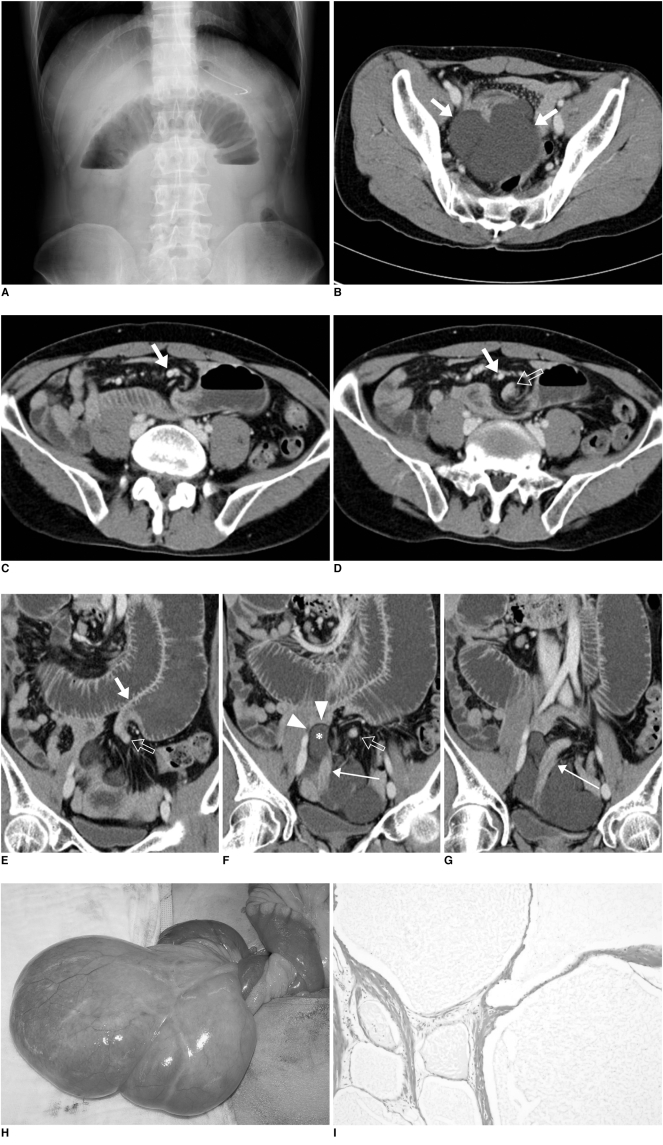

Twenty days after the first visit to our hospital, he revisited the emergency room with recurred epigastric pain. He also complained of nausea and vomiting. The blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (42.4 and 2.09 mg/dL, respectively) were slightly more increased than before (14.2 and 1.06 mg/dL, respectively), but the other laboratory results were normal. On physical examination, there was tenderness and rebound tenderness on the epigastric area, with hyperperistaltic bowel sounds. The plain radiograph suggested a markedly distended inverted U-shaped small bowel loop with an air-fluid level (Fig. 1A). A second abdominal CT scan was performed after administering an intravenous contrast agent. A fluid density mass abutting to the small bowel loops was again noted in the pelvic cavity (Fig. 1B). A thin fatty layer between the mass and the small bowel suggested that the mass probably originated from the mesentery rather than from the bowel loop. Whirling of the mesenteric vessels and small bowels around the superior mesenteric artery was disclosed on the axial and coronal reformation images (Fig. 1C-G). The superior part of the cystic mass was insinuated into the whirl. A dilated small bowel was seen tapering with a beaked appearance at the center of the whirling and this continued to the collapsed small bowel that abutted the cystic mass in the pelvic cavity. A markedly distended small bowel loop proximal to the collapsed segment was found, and this corresponded with the distended bowel loop seen on the plain radiographs. All the findings were suggestive of volvulus of the small bowel with closed loop obstruction, and we presumed that the cystic mesenteric mass was the cause of the volvulus.

Fig. 1.

43-year old man with small bowel volvulus induced by mesenteric lymphangioma.

A. Erect abdomen image at second visit to emergency room shows inverted U-shaped and markedly distended small bowel with air-fluid level in upper abdomen. Paucity of colonic gas is also noted.

B. Axial CT scan at pelvis level shows lobulated, fluid-attenuating mass (arrows). Mass closely abuts on small bowel loops. Note engorged mesenteric vessels.

C, D. Serial axial CT images at level of iliac artery bifurcation show whirling of small bowel and mesenteric vessels around superior mesenteric artery (solid arrows). Small bowel loop at left side tapers with beaked appearance and there are collapsed bowel loops within whirling (open arrow on D).

E-G. Serial, 3 mm thick, reformatted coronal images clearly demonstrate closed-loop obstruction caused by small bowel volvulus. Marked dilatation of fluid-filled small bowel loop in epigastric area is tapered with beaked appearance (solid arrow on E) and this eventually collapsed (open arrows on E and F). This collapsed bowel continued to bowel loops abutting on cystic mass in pelvic cavity (long arrows on F and G). Mesenteric aspect of mass (asterisk on F) invaginates into whirling, with intervening thin fatty layer (arrowheads on F).

H. Clinical photograph taken during laparotomy reveals large lobulate mass arising from mesentery of small bowel loops. Torsion of mass and resultant volvulus of connected mesentery and small bowel are seen.

I. Photomicroscopy (Hematoxylin & Eosin staining, ×40) of representative section shows multiple loculi with endothelial linings and thin fibrous walls. Mass was diagnosed as mesenteric lymphangioma.

Diagnostic laparotomy was performed and a large cystic mass arising from the small bowel mesentery at 60 cm distance from the Treitz ligament was found (Fig. 1H). The mass consisted of multiple well-defined locules filled with clear fluid. There was no communication between the cystic mass and the lumen of the small bowel. We observed torsion of this cystic mass that caused volvulus of the connecting mesentery and 55 cm of the small bowel, and this eventually resulted in closed loop obstruction of the small bowel. The volvulus of the small bowel and mesentery was reduced by rotating the mass. There was stricture and luminal narrowing at the twisted small bowel, so segmental resection and end-to-end anastomosis were performed. The mass was pathologically confirmed as being a lymphangioma (Fig. 1I).

DISCUSSION

Small bowel volvulus is a condition that rarely occurs among adults. There are two distinct categories of small bowel volvulus: the first is the primary type that's defined as torsion of a segment of the small bowel mesentery without evidence of any predisposing anatomical abnormalities, and the secondary type is precipitated by underlying anatomical abnormalities, including postoperative adhesion, malrotation, congenital bands, intussusception, colostomy, fistula, tumors and Meckel's diverticulum (3). Although rare, a large mesenteric mass can rotate and be accompanied by volvulus of the connected mesentery and small bowel, and eventually closed loop obstruction of the involved bowel loop occurs (4-6). In our case, small bowel volvulus and a closed loop obstruction induced by the rotation of the mesenteric lymphangioma brought the patient back to the emergency room again. At the first emergency room visit, the patient's abdominal pain was associated with incomplete small bowel volvulus and the second time his symptoms were induced by complete small bowel volvulus, which made him return to the emergency room. Ischemic damage caused by repeated episodes of torsion by the mass was probably responsible for the stricture of the involved small bowel (7).

Lymphangioma is a congenital malformation of the lymphatic vessels and this is thought to usually be a pediatric disease. Approximately 95% of lymphangiomas are found in the neck and axilla and the other 5% occur in the mediastinum and abdominal cavity, including the mesentery, retroperitoneum and bones (3). The most common symptom of mesenteric lymphangioma is a palpable abdominal mass and abdominal distension (1). Intestinal obstruction related to the mesenteric cysts can be induced by compression or traction by the mass (6, 8). The typical CT feature of mesenteric lymphangioma is a multiloculated fluid-filled mass. The attenuation of the fluid varies according to the internal contents, from that of fluid to that of fat (1). Characteristic thin walls and septa also can be seen on a CT scan (3). MDCT with thin slice multiplanar reformation is helpful to not only diagnosis the lesion, but also to assess the complications such as volvulus, as was noted in our case.

There are two theories explaining the relevance between small bowel volvulus and lymphangioma. The first is that the flaccid and mobile characteristics of a mesenteric lymphangioma cause it to rotate, and this induces small bowel volvulus. The second is that longstanding or intermittent volvulus causes lymphatic obstruction, and this forms lymphatic cysts as a result. The latter case generally forms a unilocular cystic mass without internal septa (9, 10). In our case, a multilocular mesenteric cyst was the primary pathology that secondarily caused volvulus of the small bowel.

The differential diagnosis of a cystic lesion in the pelvic cavity includes reactive ascites, duplication cysts arising from the bowel or bladder, and cystic lesions of the seminal vesicle. In our case, the lesion was present before complete small bowel volvulus and the resultant closed loop obstruction, and this had a relatively unchanged morphology during 20 days. Also, the shape of the margin between the lesion and the adjacent small bowel was convex and lobulated. These findings were suggestive of a cystic mass rather than loculated ascites. In our case, the thin fatty layer between the mass and the small bowel loops told us that the mass did not directly arise from the bowel loops. Furthermore, after the volvulus of a mass and small intestine progresses, the intrusion of a part of the mass into the whirling of the bowel and mesentery reflects the flaccid characteristics of lymphangioma. In adults, mesenteric lymphangioma should be included to the list of rare etiologies of small bowel volvulus. Radiologic evaluation, and especially with MDCT, is critical for making the correct preoperative diagnosis and treatment plan.

References

- 1.Ros PR, Olmsted WW, Moser RP, Jr, Dachman AH, Hjermstad BH, Sobin LH. Mesenteric and omental cysts: histologic classification with imaging correlation. Radiology. 1987;164:327–332. doi: 10.1148/radiology.164.2.3299483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Welch GH, Anderson JR. Volvulus of the small intenstine in adults. World J Surg. 1986;10:496–500. doi: 10.1007/BF01655319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang JC, Shin JS, Huang YT, Chao CJ, Ho SC, Wu MJ, et al. Small bowel volvulus among adults. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1906–1912. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Arfaj AA, Yaseen HA. Mesenteric cystic lymphangioma. Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1130–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT. Mesenteric cystic lymphangioma: unusual cause of intra-abdominal catastrophe in an adult. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:986–987. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2005.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mar CR, Pushpanathan C, Price D, Cramer B. Best cases from the AFIP: omental lymphangioma with small-bowel volvulus. Radiographics. 2003;23:847–851. doi: 10.1148/rg.234025123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuehne SE, Gauvin GP, Shortsleeve MJ. Small bowel stricture caused by rheumatoid vasculitis. Radiology. 1992;184:215–216. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1609082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kovalivker M, Mitovic A. Obstruction and gangrene of bowel with perforation due to a mesenteric cyst in a newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 1987;22:377–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(87)80249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traubici J, Daneman A, Wales P, Gibbs D, Fecteau A, Kim P. Mesenteric lymphatic malformation associated with smal-bowel volvulus - two cases and a reveiew of literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:362–365. doi: 10.1007/s00247-002-0658-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoon HK, Han BK. Chronic midgut volvulus with mesenteric lymphangioma: a case report. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:611. doi: 10.1007/s002470050429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]