Abstract

The Alu family is a highly successful group of non-LTR retrotransposons ubiquitously found in primate genomes. Similar to the L1 retrotransposon family, Alu elements integrate primarily through an endonuclease-dependent mechanism termed target site-primed reverse transcription (TPRT). Recent studies have suggested that, in addition to TPRT, L1 elements occasionally utilize an alternative endonuclease-independent pathway for genomic integration. To determine whether an analogous mechanism exists for Alu elements, we have analyzed three publicly available primate genomes (human, chimpanzee and rhesus macaque) for endonuclease-independent recently integrated or lineage specific Alu insertions. We recovered twenty-three examples of such insertions and show that these insertions are recognizably different from classical TPRT-mediated Alu element integration. We suggest a role for this process in DNA double-strand break repair and present evidence to suggest its association with intra-chromosomal translocations, in-vitro RNA recombination (IVRR), and synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA).

Keywords: Alu elements, endonuclease-independent insertion, double-strand break repair

Introduction

Alu elements are ubiquitous members of the Short Interspersed Element (SINE) family of mobile DNA elements, with copy numbers reaching ~ 1.2 million in the human genome and ~ 1 million in the rhesus macaque genome [1; 2]. Full length Alu elements are ~300bp long, are comprised of two monomers joined by a 32bp poly-A region and possess a variable length poly-A tail [1]. Alu elements lack any protein-coding capacity and are therefore non-autonomous retrotransposons, that use the enzymatic machinery of another retrotransposon family, the L1 elements, for integration into the host genome [3]. Although the vast majority of genomic Alu integrations occur into non-coding sequence and have no phenotypic effect, occasionally new integrants disrupt gene expression and function, and have been implicated in a multitude of human diseases, including cancer, neurofibromatosis and hemophilia [1; 4; 5; 6].

The majority of genomic Alu integration occurs through a process termed target site-primed reverse transcription (TPRT). During TPRT, the L1 endonuclease (EN) makes an initial single-strand nick at a specific site in the host genome (generally approaching the motif 5′-T2A4-3′) and the Alu mRNA anneals to the nick site using its 3′ poly-A tail. Next, the L1 reverse transcriptase initiates reverse transcription using the Alu mRNA as a template. The second strand of DNA is nicked downstream of the initial cleavage site creating staggered breaks, which are later filled in by small (7–20bp) direct repeats on either side of the element, termed target site duplications (TSDs) [7; 8]. In the final two steps, the order of which is not yet clear, the integration of the newly synthesized Alu cDNA and synthesis of the second strand occur; the normal completion of TPRT results in creating unique structural hallmarks, i.e. intact TSDs and variable length poly-A tails [9; 10]. Previous studies have established that the Alu family of retrotransposons acts as a “parasite’s parasite” and hijacks L1 machinery during classical TPRT-mediated genomic integration [11].

Mobile DNA capture has been attributed to novel chimeric genes, genetic rearrangements and deletions within and around genes [12; 13; 14; 15; 16; 17]. Recently, two analyses have documented an alternative model of mobile DNA capture, an endonuclease-independent L1 insertion mechanism [18; 19] at DNA double-strand break repair sites. This pathway, initially observed in DNA repair-deficient rodent cell lines [19], has subsequently been shown to also occur in the human genome [18]. As Alu mobilization utilizes L1 machinery in trans [7; 20; 21; 22; 23; 24; 25], the possibility exists that the non-classical endonuclease-independent insertion mechanism seen in the L1 family may also occur with Alu elements [26]. To explore this hypothesis, we scanned the three primate genomes that were publicly available at the time of analysis (human, chimpanzee, and rhesus macaque). Through a combination of computational data mining and wet bench techniques, we recovered 23 Alu elements that have exploited this alternative pathway of integration, which we term non-classical Alu insertions (NCAI). In each case, we verified the pre-insertion state of the locus by sequencing the orthologous position in an outgroup primate genome, and confirmed that the loci lack the characteristic hallmarks of TPRT-mediated insertions. We suggest that this mechanism may play a fortuitous role in genomic DSB repair. Overall, our results support the hypothesis that endonuclease-independent mobilization of non-LTR retrotransposons in primate genomes may have implications for the maintenance of genomic integrity.

Results and Discussion

Genomic distribution of non-classical Alu insertions (NCAI)

Using a combination of computational data mining and wet-bench verification, we have analyzed three primate genomes (human, chimpanzee, and rhesus macaque) for evidence of an alternative, endonuclease-independent mode of Alu integration. We excluded all endonuclease-dependent TPRT-mediated insertions through a rigorous manual inspection of putative NCAI loci following a triple alignment of the three genomes and report a total of twenty-three atypical insertions using the hg18, panTro2 and rheMac2 assemblies. Of the Hominin-specific loci we recovered, four were specific to humans, four to chimpanzees, and one locus was shared between humans and chimpanzees; the other 8 loci were shared among all four Hominin genomes assayed in our PCR analyses (i.e., human, chimpanzee, gorilla, and orangutan). Along with the truncated Alu elements, we found approximately 7.36kb of non-Alu sequence inserted at experimentally confirmed NCAI loci.

Sequence architecture of NCAI loci and alignment to the ancestral full-length sequence

Alu elements at NCAI loci ranged in size from 34bp to 276bp in contrast to full-length Alu elements which are ~300bp in length. We minimized the chance of erroneously selecting loci with post-insertion 3′ truncations of preexisting TPRT-mediated Alu elements that mimic the typical structure of EN-independent insertions by rigorously comparing the orthologous flanking sequence in all three genomes. In theory, post-insertion random genomic deletions which remove the 3′ segments of full-length Alu elements could mimic NCAI events. However, to pass our screening procedure, such random deletions would have had to arise in three separate primate genomes at exactly the same location [27]. The extremely low probability of this occurrence makes it unlikely that such loci are included in this study.

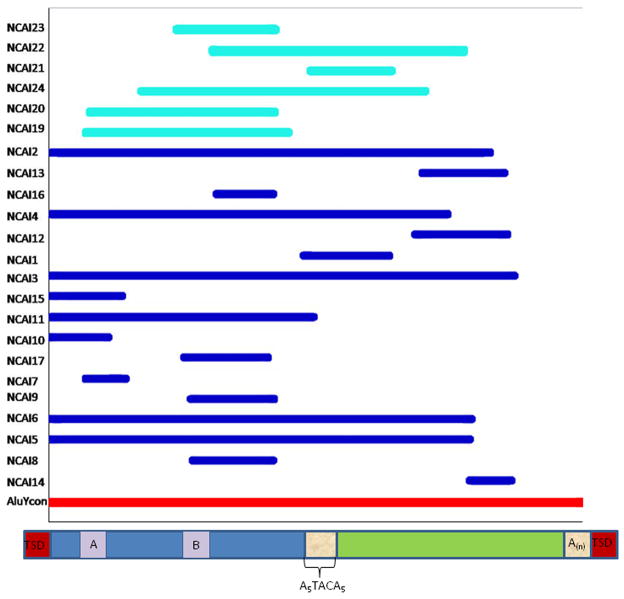

A multiple alignment of the Alu elements at NCAI loci reveals a tendency to cluster towards the 5′ end of the consensus sequences of the respective full-length elements (Figure 1). Indeed, only three insertions (NCAI 12, 13, & 14) align towards the 3′ end of the consensus sequence. Eight of the Hominin NCAI loci were 5′ intact and could not be traced back to a pre-existing Alu element when a triple alignment was performed. All other Hominin-specific NCAI loci showed 20bp or more of 5′ truncation. Ten Hominin-specific and five rhesus-specific NCAI loci had intact middle A-rich regions within the Alu element with four Hominin-specific and 3 rhesus-specific NCAI loci terminating in the middle A rich region. One locus was retained based on the results from the computational output and sequencing of the out-groups. NCAI 17 is 761bp long; it contains a 51bp Alu fragment and is rich in simple repeats. Due to the simple repeats, PCR amplification and sequencing were not possible.

Figure 1. NCAI fragments juxtaposed with a full-length Alu element consensus sequence from the RepeatMasker website.

Hominin-specific loci are in dark blue and rhesus macaque-specific loci are in light blue. The consensus sequence is in red. A visualization of an Alu element is placed below the red consensus line.

Based on the diversity of local sequence architecture features found adjacent to the NCAI loci we have recovered, we suggest that there is no one preferred model for endonuclease-independent Alu insertions and that this pathway is essentially an opportunistic mechanism for Alu integration. Over half of the 23 NCAI loci had non-Alu sequence inserted with them. One possibility is that these non-Alu sequences at NCAI loci represent “filler DNA”, small segments of which are often found at the junctions of genetic rearrangements [28; 29] (Figure 2). Previous studies have extensively documented the capture of mobile DNA at double-strand break sites in eukaryotic cells [19; 30; 31]. In the case of non-LTR retrotransposons in primate genomes, recent evidence supports the hypothesis that the L1 family may possess an endonuclease-independent mechanism that fills such genomic lesions both in cell culture analyses and in the publicly available human genome [18; 19]. In view of the fact that the same enzymatic machinery is shared between the L1 and Alu families and that both are currently mobilizing in the human genome, we suggest that our results represent evidence for a similar endonuclease-independent insertion pathway operating for Alu elements to integrate into primate genomes. In this context, it is possible that similar to L1 elements, mature Alu mRNA molecules too can act as genomic Band-Aids® by opportunistically bridging DSBs in primate genomes [32]. Given that gene density and Alu density are strongly correlated across primate genomes, it is tempting to speculate that unrepaired DSBs in gene-rich regions of the genome, which would otherwise most likely be lethal, could be preferentially repaired by such Alu mRNA from actively transcribed elements located nearby.

Figure 2. Analysis of NCAI events.

(A) Gel chromatograph of PCR products from a phylogenetic analysis of a chimpanzee-specific NCAI locus (NCAI 6). The DNA template used is indicated at the top of each lane (H, human; C, chimpanzee; G, gorilla; O, orangutan; Rh, rhesus macaque; and Gr, African green monkey). (B) Schematic diagram of an example NCAI locus (NCAI 6) showing Alu insertion (green box) associated with 7bp deletion of target DNA (red box). Matching flanking sequence are shown as light blue boxes with pink sequence indicating exact sequence match at the ends of the indels. The yellow box indicates a small segment of non-Alu ‘filler’ DNA at the 3′ end of this NCAI insertion.

Since RM cannot detect insertions under 30bp in length, and half the loci we recovered were between 34 and 50bp, it is likely that this study represents a conservative estimate of NCAI activity, as any loci below 30bp would remain undetected. The list was also narrowed by discarding all elements >2% diverged, rejecting those loci which had ambiguous sequence or putative TSDs >3bp, and those in which the pre-insertion sequence could not be authenticated. There could potentially be more NCAI loci that have the hallmarks of endonuclease-independent insertion, but which have found homology with the 5′ or 3′ regions, thereby making it difficult to locate them computationally. These loci would appear as full-length elements using our search criteria, and would remain undetected.

Structural features of NCAI loci suggest a role in DNA double-strand break repair

In terms of their local sequence architecture, NCAI loci possess a distinct set of features that differentiate them from the larger set of “classical” TPRT-mediated insertions, which supports our hypothesis that two separate mechanisms operate for Alu integration. Below, we discuss some of these features:

Twenty of the twenty-three NCAI loci included target site deletions (i.e. deletions of the pre-insertion sequence) of varying size ranging from 1bp to ~7kb and adding up to approximately 16kb of deleted sequence; this feature is thus common to both non-classical LINE and Alu insertions [18]. Among the deleted sequences, the largest deletion event was a little over 6kb and associated with a Hominin-specific NCAI event. Three loci (NCAI 7, NCAI19, and NCAI20) were kept in the analysis even though they lacked target site deletions, because close inspection of the flanking sequence in the pre-insertion loci from the other 2 genomes and the NCAI revealed perfect matches. This suggests that these Alu insertions occurred with little to no loss of genomic material.

Very few, if any, TPRT-mediated Alu insertions include non-Alu DNA between the TSDs at either end [33]; in contrast, ~56% of NCAI loci (13 out of 23) in our study included non-Alu sequence along with the Alu fragment. The random segments of DNA range in size from 2bp to ~2kb. One possible explanation for this observation could be that the Alu mRNA may invade and attach to random DNA being used as templates to fix a DSB during NHEJ [34] (Figure 2). Two loci had 5′ non-Alu inserted sequence, 4 loci had 3′ non-Alu inserted sequence, and seven loci had non-Alu inserted sequence on both sides of the truncated Alu fragment. NCAI 7 appears to have created an intra-chromosomal duplication present within chromosome 16, suggesting a segmental duplication occurred nearby. The majority of the non-Alu sequence inserted along with the NCAI loci seems to be in the form of simple repeats and microsatellites, including three inter-chromosomal translocation events (NCAI 8, NCAI 9, & NCAI 12).

At least two loci were characterized by the presence of AT-rich repeats at either end. As both NCAI and NCLI thus show occasional integration of AT-rich repeats, it is possible that, like NCLI, the NCAI process could play a role in creating new microsatellites and simple repeats [18; 35]. NCAI 17 contained a 51bp Alu fragment and ~600bp in AT-rich repeats. The insertion of these simple repeats along with the Alu element fragment created a GC-poor region (~17%) in a relatively GC-rich sequence neighborhood (~46%), thus creating an unstable environment that could act as a recombination hotspot [36]. NCAI 15 contained a 2.06kb insertion consisting of an Alu fragment, ~230bp in AT-rich repeats, and over 1kb of L1 element sequence.

Examination of the non-Alu sequence at NCAI loci yields interesting clues regarding possible insertion mechanisms. During the integration process at NCAI loci, other cellular RNAs appear to have been transcribed along with the Alu fragment inserted at two loci (NCAI 9 and NCAI 17) (Figure 2). There were also instances of capture of another retrotransposon RNA at a locus (NCAI 14, NCAI 11, NCAI 15, NCAI 9 and NCAI 13). L1 mRNA was captured most often, followed by other Alu mRNAs [24]. BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) [37] searches showed the extra nucleotides found at the 3′ end of NCAI 9 were also found with almost a nearly perfect match at another location on the same chromosome, suggesting an intra-chromosomal translocation or in vivo RNA recombination. Enzymes associated with IVRR cause stopping or pausing of the DNA polymerase along the donor strand, which could lead to a truncated Alu if enzymatic activity was terminated [38]. Synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA), an alternative model of DSB repair, could account for NCAI 14 wherein the invading strand initiates synthesis [39]. Of the 10 loci with extra sequence, at least three did not have a significant BLAST match when looking specifically at the non-Alu inserted sequence (NCAI 8 & NCAI 14) [30] and did not find statistically significant matches in other cases.

NCAI microhomology and endonuclease cleavage site analyses

Multiple lines of evidence suggest the involvement of small stretches of complementary base pairing at the sites of mobile DNA capture at double strand break sites [40]. To examine whether a similar pattern was present at NCAI loci, we compared 6 bp stretches at both ends of the inserts with corresponding lengths in the pre-insertion flanking sequence following the procedure described in Sen et al, 2007 (Figure 3A). We excluded all loci where the 5′ or 3′ end of a locus included non-Alu inserted sequence along with the Alu fragment. Alu sequence was present at the 5′ end of the NCAI locus in eleven cases and at the 3′ end in thirteen cases. Our results indicate an increased level of microhomology at the 3′ insertion junctions; however, at the 5′ end we did not find a statistically significant increase in complementary bases [41](Figure 3B). This suggests that, though the NCAI mechanism supports opportunistic integration, microhomology at the attachment end of the fragment leads to higher rates of insertion as evidenced by higher levels of microhomology at positions 1 and 2 on the 3′ end (10/13 and 9/13 loci analyzed, respectively).

Figure 3. NCAI Microhomology.

(A) Complementarity at the 5′ and 3′ ends of NCAI loci. (B) Number of matches at each position (r) and the corresponding P-values that indicate the likelihood of obtaining the observed numbers of matches by chance alone. Bases are highlighted grey if they are complementary to the corresponding nucleotide on the Alu RNA.

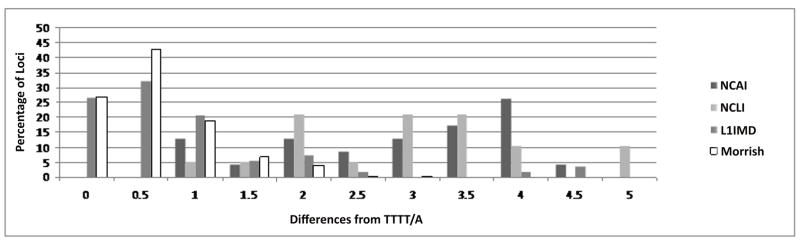

Along with microhomology, all loci were inspected for the presence of deviation from the preferred L1 endonuclease cleavage site (5′TTTT/A). Analysis of the L1 EN cleavage sites is important in this regard because Alu elements use L1 machinery to insert into primate genomes and hence, characteristic TPRT-mediated insertion sites for Alu elements are similar to those for L1. Using a previously described point value system that accounts for the differential frequencies of transitions and transversions [42], NCAI loci were compared to a previous analysis of endonuclease-independent L1 insertions [18] and then to two recent analyses of TPRT-mediated L1 insertions (Figure 4) [19; 42]. Comparison against the former suggests a similar trend towards more differences from the endonuclease cleavage site and comparison to TPRT-mediated insertions further strengthens this argument (Figure 4). This provides further support to our hypothesis that Alu elements at NCAI loci are integrating without the activity of the L1 endonuclease. While atypical motifs for L1 EN cleavage sites do exist, a careful examination of NCAI loci revealed no insertions at such non-preferred TPRT cleavage sites, providing further evidence of EN-independent insertion [18; 19; 43; 44].

Figure 4. Divergence from the L1 endonuclease cleavage site.

The results indicate a large percentage of loci with a greater number of differences from the classical L1 endonuclease cleavage site seen in Target-primed Reverse Transcription. Atypical motifs of TPRT endonuclease cleavage sites exist, but a careful examination as compared to the cleavage sites found in NCAI, showed that no insertions at atypical TPRT cleavage sites, providing supplementary evidence of endonuclease-independent insertion.

Retrotransposition using a non-traditional route in primate genomes

In this analysis we have provided the first known evidence for the existence of an alternative Alu integration mechanism that appears to be independent of the L1 endonuclease activity. While TPRT-mediated insertions are much more abundant and without question form the preferred method of Alu mobilization, the structural features of loci discussed in this study leave little doubt that it has not been utilized in these cases. While previous research has shown that an endonuclease-independent pathway exists for L1 retrotransposition, both in cell culture and in the reference human genome [18; 19], in our opinion the discovery of a similar mechanism for Alu elements is significant for a number of reasons.

In contrast to TPRT-mediated insertions, which are prone to causing genomic instability, the unique structural features of the NCAI mechanism discussed above lend credence to the hypothesis that they are associated with genomic DSB repair, and hence to the maintenance of genomic stability. The ubiquity of the Alu family in primate genomes implies that over evolutionary timescales, this endonuclease-independent pathway may have had an appreciable contribution to genome stability, and the relatively small numbers of insertions we have recovered in the three genomes probably represent a small fraction of the total number, for reasons we have discussed in the Materials and Methods section.

The human genome contains ~1.2 million, the chimpanzee ~1.1 million, and the Rhesus genome has ~1 million Alu elements [45]. Using the Tables utility from UCSC’s BLAT website [46], and filtering for Alu elements showing divergence of 2% or less from the consensus sequence, we found 572 young inserts in the human genome, 160 in the chimpanzee genome, and 1075 in the Rhesus macaque genome. Based on the lineage-specific NCAI events recovered during the analysis of the human, chimpanzee, and Rhesus macaque genomes, including 4 human-specific, 4 chimpanzee-specific, and 6 Rhesus macaque-specific insertions, our data suggest a rate of insertion among young Alu elements by this endonuclease-independent pathway in each genome to be ~0.7%, 2.5%, and ~0.56%, respectively. This suggests that anywhere from as many as 27,500 to as few as 5,581 NCAI events occurred within any of the three primate lineages that were analyzed. Overall, there appears to have been a relatively homogeneous rate of NCAI throughout this portion of the primate lineage which includes humans, African apes and old world monkeys. We believe the insertion rate in the chimpanzee genome may be inflated as a result of the calculations of percent divergence being based on the human Alu element consensus sequences [26]. These rates are much lower than those for TPRT-mediated insertions which encompass the vast majority of Alu insertions in primates [47].

DSB repair occurs using many pathways and a multitude of RNAs are recruited; we suggest Alu elements are preferentially caught at these breaks due to the large amount of free floating retrotransposon RNA [18]. While the relative paucity of NCAI loci as compared to NCLI may be due to the greater length of the L1 mRNA providing a better chance of joining the separated ends of DSBs, in our opinion the fact that both of the most active non-LTR retrotransposon families in recent primate genome evolution (i.e Alu and L1) are capable of participating in DSB repair is significant. In the sequence context of a recently created and unrepaired genomic DSB, the relative disadvantage of the shorter Alu mRNA as a repair tool compared to the longer L1 mRNA could potentially be offset by the fact that in contrast to L1 elements, the Alu family is concentrated in gene-dense areas, damage in which would likely be less tolerated hence giving NCAI a chance to be the genomic “first line of defense”. Indeed, it is possible to envision a scenario wherein the NCAI and NCLI mechanisms operate at two slightly different levels, with NCAI having access only to recent DSBs without much separation between the ends, while NCLI could act as a repair mechanism for breaks where the 300bp Alu mRNA is unable to bridge the gap. Interestingly, this hypothesis is supported by the mean sizes of the deleted genomic sequences at NCAI and NCLI loci (712 bp vs. 1723 bp), which would provide an approximation of the mechanical separation between the two halves of the DSB at the breakpoint.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have demonstrated an alternative Alu element integration method in primate genomes that may be utilized as a genomic damage repair pathway. By detailed inspection of the pre-insertion and post-insertion features of the sequence architecture, we have shown that this mechanism is distinct from the usual TPRT-mediated mode of integration and that TPRT and NCAI may have different consequences for primate genomes. On a global basis, TPRT-mediated Alu and L1 insertions are associated with disruption of gene function and are prone to post-insertion ectopic recombination. On the contrary, the endonuclease-independent NCAI we detected here, and the NCLI loci reported previously, and similar insertions in previous cell-culture analyses, show definite signs of being variants of DNA repair. In view of this evidence, it is now evident that both the L1 and Alu families contribute occasionally to the maintenance of genome stability, which provides additional insight into a hitherto neglected aspect of the biology of non-LTR retrotransposons, the most dynamic components of primate genomes.

Materials and Methods

Computational screening and manual verification of putative NCAI loci

Classical TPRT-mediated Alu insertions are characterized by the presence of TSDs, L1 EN-cleavage sites falling within a limited spectrum of previously identified “preferred” motifs [19] and poly-A tails of varying length; the criteria used in the study identified Alu insertions that were truncated 3′ (lacking the poly-A tail), lacked TSDs, and did not have the structural hallmarks of an EN-cleavage site (typical or atypical) [9]. By looking for structural features similar to those described in Morrish et al (2002) and Sen et al (2007), the likelihood of finding false positives was reduced. To identify putative NCAI loci, we modified the method outlined in Sen et al (2007) for detecting similar insertions of L1 elements. Briefly, we downloaded whole-chromosome annotation files tabulating all mobile elements on each chromosome (available at http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/downloads.html#human) for the human (hg18) and chimpanzee (panTro2) genomes, and then using in-house Perl scripts, filtered out all non-Alu sequence, leaving only Alu elements [48]. Next, to scan for truncated Alu elements missing the poly-A tail that is used during classical TPRT-mediated integration, we wrote a set of programs to locate those elements which had 3′ truncations to positions numbering 276 or less, according to the 312bp AluY consensus sequence used by the RepeatMasker (RM) software package at its default settings [49]. We chose this 3′ truncation limit to account for fluctuations in the poly-A tail length and maximize the number of putative loci while minimizing false hits. While the limit of 3′ truncation that we specified is arbitrary in terms of nucleotide position, we believe it is effective for the purpose of this analysis, as a manual inspection of putative loci attained by incrementally increasing the cutoff position from 276 towards the 3′ end of an intact element leads to an increase in false positives without returning any new loci fitting the criteria described above.

For the rhesus macaque genome (rheMac2), our strategy was slightly different due to the unavailability of whole-genome repeat annotations and the difference in Alu subfamily structure from the human and chimpanzee genomes. To locate putative NCAI loci in this genome, we first created a custom Alu element library and ran RM with varying 3′ truncation cutoff points to account for the different sizes of Alu subfamilies in the rhesus genome, which vary between 255 and 267bp, not including the middle A-rich region or the poly-A tail [50; 51].

Manual inspection of computationally detected loci involved extracting the putative truncated Alu along with 5000bp of flanking sequence on both sides of each locus. Next, for any one primate genome (i.e., human, chimpanzee, or rhesus), we used this sequence to query the other two genomes using the BLAT software suite (http://www.genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/) and created a triple alignment at the locus to analyze the local pre-insertion and post-insertion sequence architecture. In particular, we scanned for the presence of TSDs of any length and for any target site deletions present in the pre-insertion sequence but removed during the Alu insertion. By including the 5000bp to either side of the locus, we were able to investigate the Alu element within the context of its flanking sequence and ascertain whether the element was truly young and truncated. To avoid including TPRT-mediated Alu elements partially masked by poly(N) stretches in the rhesus macaque genome, we only included Alu elements that were both 5′ (15–25bp) and 3′ (35–50bp) truncated and excluded all Alu elements flanked by unknown sequence. As we were only interested in relatively recent integrations for which we would be able to reconstruct the pre-insertion architecture from the other two primates, we discarded all elements >2% diverged from their respective consensus sequences according to the RM algorithm.

Loci matching all of the following five criteria were selected for experimental validation: 3′ truncation as specified above, absence of TSDs, absence of a poly-A tail, absence of typical or atypical EN cleavage site, and verifiable pre-insertion sequence structure in two other genomes. If the pre-insertion site in the orthologous genome contained any extraneous sequence between the starting points of the upstream and downstream matching flanking regions in the post-insertion genome, we cross-checked these against the putative NCAI to confirm that they were different (Table 1). Some putative chimpanzee and rhesus loci posed a problem as they were comprised of truncated Alu elements followed or preceded by a string of non-specific sequence (Ns). Wherever possible, we resequenced these loci to read through the poly-N stretches, and for the rhesus macaque loci we included African green monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops) DNA to accurately ascertain the pre-insertion sequence. To further confirm that loci fitting all the criteria described above were indeed atypical Alu insertions and not artifacts arising from sequence assembly errors, we PCR-amplified and resequenced all loci from a panel of primate genomes (Figure 2).

Table 1.

NCAI loci and insertion site characteristics

| Locus |

Coordinates |

Alu bp_ins |

Non-Alu bp_ins |

bp_del |

Lineage |

Intragenic |

Non Alu seq |

subfamily |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCAI1 | chr11:130163514-130173562 | 45 | 6 | 7 | H | - | - | Sc |

| NCAI2 | chr22:41749851-41760112a | 258 | 0 | 21 | H | - | - | Ya5 |

| NCAI3 | chr6:68781896-68792171 | 272 | 0 | 15 | H | - | - | Ya5 |

| NCAI4 | chr14:88215334-88225566 | 233 | 0 | 2613 | H | - | - | Ya5 |

| NCAI5 | chr4:123138133-123148385 | 246 | 0 | 28 | C | - | - | Y |

| NCAI6 | chr5:26686575-26696822 | 247 | 0 | 5 | C | - | - | Y |

| NCAI7 | chr16:13891929-13901955 | 25 | 186 | 0 | C | - | 5′ | Y |

| NCAI8 | chr3:79858862-79868909 | 48 | 341 | 33 | C | - | 3′ | Yg |

| NCAI9 | chr13:77357997-77368046 | 50 | 199 | 2 | HC | MYC BP2 | 5′/3′ | Yb8 |

| NCAI10 | chr2:131354400-131364436 | 35 | 3 | 258 | HCG | - | - | Y |

| NCAI11 | chr3:167550099-167560252 | 155 | 2075 | 2913 | HCG | - | 5′/3′ | Yb9 |

| NCAI12 | chr13:25754437-25764491 | 55 | 67 | 47 | HCG | - | 5′/3′ | Sg/x |

| NCAI13 | chr16:70114181-70124229 | 49 | 134 | 136 | HCG | - | 5′/3′ | Sg/x |

| NCAI14 | chr2a:106680448-106690481 | 34 | 661 | 2436 | HCG | - | 3′ | Yc3 |

| NCAI15 | chr5:64216227-64226270 | 43 | 2021 | 6670 | HCG | - | 5′ | Y |

| NCAI16 | chr16:63330452-63340488 | 34 | 0 | 966 | HCG | - | - | Yc |

| NCAI17 | chr19:51178572-51188621 | 50 | 639 | 18 | HCG | OPA3 | 5′/3′ | Sp |

| NCAI19 | chr2:151660217-151670318 | 113 | 7 | 0 | Rh | PPP2R3A | 3′ | YRa |

| NCAI20 | chr3:42636756-42636861 | 107 | 53 | 0 | Rh | - | 5′/3′ | YRd |

| NCAI21 | chr4:103197391-103197423 | 41 | 7 | 49 | Rh | - | - | YRa |

| NCAI22 | chr12:81864628-81874777 | 148 | 2 | 51 | Rh | - | - | YRb |

| NCAI23 | chrX:65517270-65527328 | 58 | 17 | 1 | Rh | - | 3′ | YRd |

| NCAI24 | chr2:42702265-42712434 | 167 | 0 | 113 | Rh | - | - | YR |

| Total (bp) | 2513 | 6418 | 16382 | |||||

| a. Callinan et al paper 2005 | ||||||||

The letter in the column for ‘Lineage’ indicates the genome(s) to which the NCAI event is specific. In some cases the NCAI events were found in the Human, Chimpanzee, and Gorilla genomes, but were absent in the Rhesus macaque genome.

This locus was previously discussed in Callinan et al 2005.

PCR amplification and verification through resequencing

Primers surrounding each putative NCAI locus were designed using the Primer3 utility (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi). PCR was performed in 25 μl reactions using 15–25ng genomic DNA, 0.28μM primer, 200μM dNTPs in 50mM KCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 10mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), and 2.5 units Taq DNA polymerase. Thermocycler programs were as follows: 95°C for 2 min (1 cycle), [95°C for 30sec, optimal annealing temperature for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min] (35 cycles), 72°C for 10 min (1 cycle). PCR products were visualized on 1–2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. For PCR fragments larger than 1.5kb, ExTaq™ (Takara) was used according to the manufacturer’s specified protocol. All loci were amplified from the following genomes: Homo sapiens (HeLa; cell line ATCC CCL-2), Pan troglodytes (common chimpanzee; cell line from Coriell Cell Repositories AG06939B), Gorilla gorilla (Western lowland gorilla; cell line Coriell Cell Repositories AG05251), Pongo pygmaeus (orangutan; cell line GM04272A), Macaca mulatta (Rhesus macaque; cell line NG07109), and Chlorocebus aethiops (African green monkey; cell line ATCC CCL70). Primer sequences and annealing temperatures are available from the Publications section of the Batzer laboratory website (http://batzerlab.lsu.edu) under supplemental data.

Most loci were sequenced directly from the PCR amplicons after cleanup using Wizard® gel purification kits (Promega Corporation) or ExoSAP-IT® (USB Corporation). Samples that could not be sequenced directly from PCR products were cloned into vectors using the TOPO TA (fragments <1kb) and TOPO XL (fragments >1kb) cloning kits (Invitrogen). All sequencing was done using an ABI3130XL automated DNA sequencer. The resulting sequence files were analyzed using BioEdit and the SeqMan and EditSeq utilities from the DNAStar package® V.5. GC content in the flanking regions was calculated using GEECEE (available at: http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/MobylePortal/portal.py?form=geecee). New DNA sequences generated during the course of this analysis have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers EU263070-EU263102.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members of the Batzer laboratory for their support and feedback. They would especially like to thank J.A. Walker, K. Han and M. Konkel for suggestions and advice. They are grateful to T.J. Meyer and J. Huang for their useful comments during the preparation of the manuscript. D.S. expresses her gratitude to T.P. Achee for his support and patience. This research was supported by National Science Foundation grant BCS-0218338 (M.A.B.); National Institutes of Health RO1 GM59290 (M.A.B.), and the State of Louisiana Board of Regents Support Fund (M.A.B.).

Abbreviations

- NCAI

non-classical Alu insertion

- CS

chimpanzee-specific

- HS

human-specific

- RS

rhesus-specific

- DSBs

double-strand breaks

- TPRT

target primed reverse transcription

- SDSA

synthesis dependent strand annealing

- IVRR

in vitro RNA recombination

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- NHEJ

non-homologous end-joining

- EN

endonuclease

- RT

reverse transcriptase

- SINE

short interspersed element

- OWM

old world monkey

- RM

RepeatMasker

- TSD

target site duplication

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:370–9. doi: 10.1038/nrg798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han K, Konkel MK, Xing J, Wang H, Lee J, Meyer TJ, Huang CT, Sandifer E, Hebert K, Barnes EW, Hubley R, Miller W, Smit AF, Ullmer B, Batzer MA. Mobile DNA in Old World monkeys: a glimpse through the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:238–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1139462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathias SL, Scott AF, Kazazian HH, Jr, Boeke JD, Gabriel A. Reverse transcriptase encoded by a human transposable element. Science. 1991;254:1808–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1722352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callinan P, Batzer MA. Retrotransposable Elements and Human Disease. Genome Dynamics. 2006;1:104–115. doi: 10.1159/000092503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hulme A, Kulpa E, Perez DA, JLG, Moran JV. The Impact of LINE-1 Retro transposition on the Human Genome. Genomic Disorders. 2006:35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deininger PL, Batzer MA. Alu repeats and human disease. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:183–93. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Q, Moran JV, Kazazian HH, Jr, Boeke JD. Human L1 retrotransposon encodes a conserved endonuclease required for retrotransposition. Cell. 1996;87:905–16. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81997-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudin CM, Thompson CB. Transcriptional activation of short interspersed elements by DNA-damaging agents. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;30:64–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luan DD, Korman MH, Jakubczak JL, Eickbush TH. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell. 1993;72:595–605. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert N, Lutz S, Morrish TA, Moran JV. Multiple fates of L1 retrotransposition intermediates in cultured human cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7780–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7780-7795.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid CW. Alu: a parasite’s parasite? Nat Genet. 2003;35:15–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0903-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordaux R, Udit S, Batzer MA, Feschotte C. Birth of a chimeric primate gene by capture of the transposase gene from a mobile element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8101–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen JM, Chuzhanova N, Stenson PD, Ferec C, Cooper DN. Meta-analysis of gross insertions causing human genetic disease: novel mutational mechanisms and the role of replication slippage. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:207–21. doi: 10.1002/humu.20133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Britten RJ, Rowen L, Williams J, Cameron RA. Majority of divergence between closely related DNA samples is due to indels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4661–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0330964100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmid CW. Does SINE evolution preclude Alu function? Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4541–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.20.4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kass DH, Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Gene conversion as a secondary mechanism of short interspersed element (SINE) evolution. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:19–25. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran JV, Holmes SE, Naas TP, DeBerardinis RJ, Boeke JD, Kazazian HH., Jr High frequency retrotransposition in cultured mammalian cells. Cell. 1996;87:917–27. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81998-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sen SK, Huang CT, Han K, Batzer MA. Endonuclease-independent insertion provides an alternative pathway for L1 retrotransposition in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3741–51. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morrish TA, Gilbert N, Myers JS, Vincent BJ, Stamato TD, Taccioli GE, Batzer MA, Moran JV. DNA repair mediated by endonuclease-independent LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nat Genet. 2002;31:159–65. doi: 10.1038/ng898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakaki Y, Hattori M, Fujita A, Yoshioka K, Kuhara S, Takenaka O. The LINE-1 family of primates may encode a reverse transcriptase-like protein. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 1986;51(Pt 1):465–9. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1986.051.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skowronski J, Fanning TG, Singer MF. Unit-length line-1 transcripts in human teratocarcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1385–97. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH., Jr Biology of mammalian L1 retrotransposons. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:501–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei W, Gilbert N, Ooi SL, Lawler JF, Ostertag EM, Kazazian HH, Boeke JD, Moran JV. Human L1 retrotransposition: cis preference versus trans complementation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1429–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1429-1439.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dewannieux M, Esnault C, Heidmann T. LINE-mediated retrotransposition of marked Alu sequences. Nat Genet. 2003;35:41–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Perez JL, Doucet AJ, Bucheton A, Moran JV, Gilbert N. Distinct mechanisms for trans-mediated mobilization of cellular RNAs by the LINE-1 reverse transcriptase. Genome Res. 2007;17:602–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.5870107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hedges DJ, Callinan PA, Cordaux R, Xing J, Barnes E, Batzer MA. Differential alu mobilization and polymorphism among the human and chimpanzee lineages. Genome Res. 2004;14:1068–75. doi: 10.1101/gr.2530404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mager DL, Henthorn PS, Smithies O. A Chinese G gamma + (A gamma delta beta)zero thalassemia deletion: comparison to other deletions in the human beta-globin gene cluster and sequence analysis of the breakpoints. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:6559–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.18.6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth DB, Chang XB, Wilson JH. Comparison of filler DNA at immune, nonimmune, and oncogenic rearrangements suggests multiple mechanisms of formation. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3049–57. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Audrezet MP, Chen JM, Raguenes O, Chuzhanova N, Giteau K, Le Marechal C, Quere I, Cooper DN, Ferec C. Genomic rearrangements in the CFTR gene: extensive allelic heterogeneity and diverse mutational mechanisms. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:343–57. doi: 10.1002/humu.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin Y, Waldman AS. Promiscuous patching of broken chromosomes in mammalian cells with extrachromosomal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:3975–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.19.3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichiyanagi K, Nakajima R, Kajikawa M, Okada N. Novel retrotransposon analysis reveals multiple mobility pathways dictated by hosts. Genome Res. 2007;17:33–41. doi: 10.1101/gr.5542607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen MR, Brosius J, Deininger PL. BC1 RNA, the transcript from a master gene for ID element amplification, is able to prime its own reverse transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1641–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.8.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pickeral OK, Makalowski W, Boguski MS, Boeke JD. Frequent human genomic DNA transduction driven by LINE-1 retrotransposition. Genome Res. 2000;10:411–5. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paques F, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:349–404. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ovchinnikov I, Troxel AB, Swergold GD. Genomic Characterization of Recent Human LINE-1 Insertions: Evidence Supporting Random Insertion. Genome Res. 2001;11:2050–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.194701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirkin SM. DNA structures, repeat expansions and human hereditary disorders. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2006;16:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagy PD, Simon AE. New insights into the mechanisms of RNA recombination. Virology. 1997;235:1–9. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedges DJ, Deininger PL. Inviting instability: Transposable elements, double-strand breaks, and the maintenance of genome integrity. Mutat Res. 2007;616:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfeiffer P, Thode S, Hancke J, Vielmetter W. Mechanisms of overlap formation in nonhomologous DNA end joining. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:888–95. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zingler N, Willhoeft U, Brose HP, Schoder V, Jahns T, Hanschmann KM, Morrish TA, Lower J, Schumann GG. Analysis of 5′ junctions of human LINE-1 and Alu retrotransposons suggests an alternative model for 5′-end attachment requiring microhomology-mediated end-joining. Genome Res. 2005;15:780–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.3421505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han K, Sen SK, Wang J, Callinan PA, Lee J, Cordaux R, Liang P, Batzer MA. Genomic rearrangements by LINE-1 insertion-mediated deletion in the human and chimpanzee lineages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:4040–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Callinan PA, Wang J, Herke SW, Garber RK, Liang P, Batzer MA. Alu Retrotransposition-mediated Deletion. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:791–800. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cost GJ, Boeke JD. Targeting of human retrotransposon integration is directed by the specificity of the L1 endonuclease for regions of unusual DNA structure. Biochemistry. 1998;37:18081–93. doi: 10.1021/bi981858s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.RMGSAC. Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:222–34. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kent WJ. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–64. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szak ST, Pickeral OK, Makalowski W, Boguski MS, Landsman D, Boeke JD. Molecular archeology of L1 insertions in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0052. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-10-research0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.TCSAC. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.A. Smit, Hubley, R & Green, P., RepeatMasker Open-3.0. (1996–2004).

- 50.Han K, Lee J, Meyer TJ, Wang J, Sen SK, Srikanta D, Liang P, Batzer MA. Alu recombination-mediated structural deletions in the chimpanzee genome. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1939–49. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.R.M.G.S.a.A.C. (RMGSAC) Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science. 2007;316:222–234. doi: 10.1126/science.1139247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.