Abstract

TNKase is a genetically engineered variant of the alteplase molecule. Three different mutations result in an increase of the plasma half-life, of the resistance to plasminogen-activator inhibitor 1 and of the thrombolytic potency against platelet-rich thrombi. Among available agents in clinical practice, TNKase is the most fibrin-specific molecule and can be delivered as a single bolus intravenous injection. Several large-scale clinical trials have enrolled more than 27,000 patients with acute myocardial infarction, making the use of this drug truly evidence-based. TNKase is equivalent to front-loaded alteplase in terms of mortality and is the only bolus thrombolytic drug for which this equivalence has been formally demonstrated. TNKase appears more potent than alteplase when symptoms duration lasts more than 4 hours. Also, TNKase significantly reduces the rate of major bleeds and the need for blood transfusions. The efficacy of TNKase may be further improved by enoxaparin substitution for unfractionated heparin, provided that enoxaparin dose adjustment is made for patients more than 75 years old. Hitherto, the small available randomized studies and international clinical registries suggest that pre-hospital TNKase is as effective as primary angioplasty, thus laying the foundations for a new fibrinolytic, TNKase-based strategy as the backbone of reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction.

Keywords: tenecteplase, TNKase, myocardial infarction, alteplase

Thrombolytic therapy versus primary angioplasty

Acute myocardial infarction presenting with ST-segment elevation (STEMI) is usually precipitated by plaque disruption with coronary thrombosis. The quick recanalization by either thrombolysis (TBL) or primary angioplasty (P-PCI) is the most important way to improve the short- and long-term prognosis. Current American and European guidelines “prefer” P-PCI, usually believed to achieve better coronary recanalization rates, prevent re-infarction and, ultimately, improve survival.1 However, many conceptual and practical items dispute this presumed superiority of P-PCI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reasons for preferring thrombolysis (TBL) to primary angioplasty (P-PCI)

| TBL is immediately available everywhere |

| The time-delay to perform P-PCI exceeds 90 minutes in a large fraction of patients |

| P-PCI does not reduce mortality consistently, particularly vs pre-hospital TBL |

| TBL can be improved by new adjunctive treatments (clopidogrel and enoxaparin) |

The claim that P-PCI leads to a mortality reduction has never been shown in any single trial and is only suggested by an overview of 23 small trials, with only 2 trials enrolling more than 1000 patients.2 Furthermore, this small advantage is no longer significant when the comparison is made with the accelerated infusion of alteplase.3 Too many times have we observed the failure of such positive small meta-analyses, such as those evaluating the effects of nitrates or magnesium in acute myocardial infarction, or the efficacy of angiotensin-II blockers to prevent atrial fibrillation, or the efficacy of aspirin to prevent eclampsia.

The frequently quoted mortality reduction observed in patients treated with P-PCI in registries is largely biased both by the incapacity of statistical methods, such as the propensity score, to take into account important, intangible confounders, and by the entry in the P-PCI cohort of only those patients actually being treated and not those patients intended to treat.4

Currently, only 25% of American hospitals provide primary angioplasty and the majority of patients must be transferred to receive the mechanical intervention.5 As a consequence, only approximately 4% of transferred patients receive P-PCI within 90 minutes from first medical contact.6 Attempts to improve this situation so far have required “huge” efforts, with a negligible mortality yield.7 An increase in the number of catheterization laboratories has been proposed to cope with these shortcomings. However, such a proliferation dilutes the number of patients treated in each catheteriztion laboratory, endangering quality,8 not to say the costs of increasing population-based coronary angiograms in patients without myocardial infarction. Further difficulties arise during weekends and at night,5 again jeopardizing quality.

Pre-hospital thrombolytic therapy

On the other hand, TBL can be delivered everywhere and particularly when used in the pre-hospital setting is extremely competitive with P-PCI, as demonstrated by the CAPTIM study.9 In the recent, important MINAP registry the pre-hospital use of TBL (nearly always TNKase) ranked among the strongest independent predictors of in-hospital survival in the United Kingdom.10

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines encourage the recording of the 12-lead electrocardiogram “on-scene” and performing pre-hospital TBL within 30 minutes.1 Indeed, the STEMI picture is dominated by time, with the small incremental benefit of P-PCI rapidly vanishing after 90 minutes after first medical contact, particularly among young patients with large myocardial infarction, for whom the equivalence of TBL and P-PCI may already be achieved by a delay of only 45 minutes.11 Since time is so important, it is believed that most benefit may be achieved by treating as many patients as possible in the first 3 hours from the onset of symptoms, regardless of whether TBL or P-PCI is used.12 It is now estimated that an efficient network can offer pre-hospital TBL in the first 3 hours in approximately 50% to 60% of STEMI patients.13

TBL can be further improved by reducing the re-infarction rate by adjunctive use of clopidogrel14 and enoxaparin15 as soon as possible, ideally pre-hospital.

Pharmacologic properties of TNKase in acute myocardial infarction

TNKase consists of the alteplase molecule (with the exception of three point mutations) and has a molecular weight of 65,000 kD. Thr103 substitution by Asn and the mutation of the sequence Lys296 – His-Arg-Arg to Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala prolong the half-life and increase the resistance to plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). Additional substitution of Asn117 by Gln results in an 8-fold decrease in clearance and in a 200-fold increase in resistance to PAI-1.

Compared with other molecules used in clinical practice, TNKase has the highest degree of fibrin specificity and binding. Fibrin specificity, in turn, implies a reduced propensity for causing major non-cerebral bleeds, because lytic activity is restricted to plasmin on the fibrin surface, thus avoiding the breakdown of fibrinogen, factor V, factor VIII and α2-antiplasmin.16 The TNKase conformational change reduces its elimination and prolongs its plasma half-life (α-half-life 11–20 minutes, β-half-life 41–138 minutes). Nitrates do not appear to affect TNKase levels, as opposed to what happens with alteplase levels.17 Moreover, the inhibition by PAI-1 is reduced 80 times compared with alteplase.

The above properties are interesting in the treatment of patients with STEMI, allowing single bolus infusion and preventing drug inactivation at the site of platelet-rich coronary thrombosis. In addition, TNKase has more intense anti-platelet properties both in vitro and in vivo compared with those of alteplase.18 In experimental models the thrombolytic potency of TNKase is 3-fold higher than that of alteplase.19

Clinical use of TNKase in acute myocardial infarction

The first experience of dose-testing TNKase in STEMI began in the TIMI-10A trial, showing a dose-dependent increase in TIMI-3 flow rates in the 5 to 50 mg dose range (p = 0.032).20

In the dose-escalating pilot TIMI 10B patency trial, involving 886 patients 18 to 80 years old, bolus TNKase injection achieved coronary TIMI grade-3 flow rates of 55%, 63% and 66% at 90 minutes after 30, 40 and 50 mg bolus injection.21 The TIMI-3 flow rate was similar to that observed in the control group, receiving front-loaded alteplase.

The safety of TNKase in STEMI was investigated in ASSENT-1;22 3235 patients received either 30 or 40 or 50 mg TNKase as a bolus injection. The total stroke rate at 30 days was 1.5% and the intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) rate was 0.8%, without significant differences between groups. Serious bleeding, requiring blood transfusion, occurred in 1.4% of patients in the TNKase group and in 7% of those treated with front-loaded alteplase. Importantly, TIMI-10B and ASSENT-1 showed the importance of reducing the heparin dose in conjunction with TNKase, to minimize the risk of ICH.23

Survival data with TNKase have been tested in comparison with those achieved using front-loaded alteplase in the large, multicenter, confirmation ASSENT-2 trial. A total of 16,949 patients with STEMI in the first 6 hours from the onset of symptoms received either weight-adjusted TNKase over 5 to 10 seconds (less than 60 kg: 30 mg; 60–69.9 kg: 35 mg; 70–79.9 kg: 40 mg; 80–89.9 kg: 45 mg; and more than 90 kg: 50 mg) or front-loaded alteplase, along with aspirin and reduced-dose unfractionated heparin.24 This was an equivalence trial and all-cause mortality at 30 days was the primary end-point. There was no difference between TNKase and alteplase in mortality (6.18% vs 6.15%) and stroke rate, including ICH (0.93% vs 0.94%, respectively). Moreover, in the TNKase group there was a decreased rate in non-cerebral bleeds (26.43% vs 28.95%, p = 0.0003), in major bleeds (4.68% vs 5.94%, p = 0.0002) and in the need for blood transfusion (4.25% vs 5.49%, p = 0.0002) (Table 2). There was also a tendency for ICH to be decreased by TNKase among the high-risk population of females of more than 75 years old who weighed <67 kg (1.14% vs 3.02%).25 The general ASSENT-2 trial results were confirmed in all major subgroups, including those related to age, gender, infarct location, Killip class and diabetes status. Interestingly, mortality was significantly lower in the TNKase group when treatment was given more than 4 hours after the onset of symptoms (7.0% vs 9.2%, p = 0.018), a finding that could be attributed to the drug’s fibrin specificity leading to better dissolution of older coronary clots and confirms from a clinical standpoint the improved pharmacologic profile of this molecule.

Table 2.

Clinical studies with TNKase in STEMI

| Trial (year) | Patients | Comparison | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASSENT-2 (1999) | 16,949 | TNKase vs rt-PA | TNKase and rt-PA equivalent, ↓ major bleeding with TNKase |

| ASSENT-3 (2001) | 6,095 | ENOX vs ABX vs UFHa | ENOX and ABX better than UFH |

| ENTIRE-TIMI 23 (2002) | 483 | ENOX vs ABX vs UFHa | ENOX and ABX better than UFH, ↑ bleeding with ABX |

| ASSENT-3-PLUS (2003) | 1,639 | ENOX vs UFHa, pre-hospital delivery | ↓ reinfarction with ENOX, ↑ stroke/intracranial bleed |

| CAPITAL-AMI (2005) | 170 | F-PCIc vs TNKasea | ↓ residual ischemia with F-PCI |

| ASSENT-4 (2006) | 1,667 | F-PCIc vs P-PCIb | ↑ death/ischemia/bleeding in the F-PCI group |

| WEST (2006) | 304 | TNKase vs F-PCIc vs P-PCI | TNKase and F-PCI comparable to P-PCI |

| GRACIA-2 (2007) | 212 | TNKased vs P-PCI | ↑ reperfusion with TNKased Similar ventricular damage |

All patients in the trial received TNKase.

P-PCI: Primary angioplasty.

F-PCI: Primary angioplasty, facilitated by TNKase.

TNKase followed by routine angioplasty within 3–12 hours (“pharmaco-invasive” approach).

Among other in-hospital outcomes, TNKase also reduced the rate of congestive heart failure (ie, Killip class >1: 6.1% vs 7.0%, p = 0.025).

Thus, the ASSENT-2 trial indicates that single-bolus TNKase is equivalent to the more complex accelerated alteplase infusion, in terms of mortality and mortality/stroke combination, with the further advantage of a decrease in major bleeding rate. These positive results were persisting after 1 year.26

TNKase and the adjunctive use of antithrombotic therapy and of mechanical intervention

The possibility of further improving the effects of TNKase by means of new adjunctive treatments has been explored in ASSENT-3 and ENTIRE-TIMI 23 studies.27,28 In ASSENT-3 a total of 6095 patients with STEMI in the first 6 hours from the onset of symptoms were treated with either full-dose TNKase plus unfractionated heparin (UFH), full-dose TNKase plus enoxaparin (ENOX), or half-dose TNKase plus UFH and the GPIIB-IIIA inhibitor abciximab (ABX). Compared with UFH, the primary end-point (30-day mortality plus in-hospital reinfarction and in-hospital refractory ischemia) was reduced by ENOX (11.4% vs 15.4%, p = 0.0002) and by the combination of UFH plus ABX (11.1%, p = 0.0001). When in-hospital ICH or major bleeds were added to the primary end-point (so called efficacy plus safety end-point), again, a significant reduction was observed both in the ENOX group (13.7% vs 17.0%, p = 0.0037) and in the UFH plus ABX group (14.2%, p = 0.01416). ABX increased the rate of thrombocytopenia compared to both ENOX and UFH (3.2% vs 1.2% and 1.3% respectively, p = 0.0001) and it also increased the cost of treatment.29

Similar results were observed in the smaller ENTIRE-TIMI 23 trial.28 This trial had a design very similar to that of ASSENT-3, although there was a further group receiving ENOX in combination with ABX and half-dose TNKase. Overall, the adjunctive use of ENOX with TNKase, compared with UFH, reduced the combined incidence of death/myocardial infarction at 30 days (4.4% vs 15.9%, p = 0.005). ABX did not further decrease the end-point; rather, ABX increased the risk of major bleeding (5.2% vs 2.4% compared with UFH alone and 8.5% vs 1.9% compared with ENOX alone). Major bleeding was also increased when half-dose TNKase was combined with eptifibatide, a small-molecule GP IIB-IIIA inhibitor in the INTEGRITI study.30 In conjunction with the GUSTO-V data,31 ASSENT-3, ENTIRE-TIMI-23 and INTEGRITI indicate that GPIIB-IIIA agents should not be associated with thrombolytic drugs.

In conclusion, ASSENT-3 and ENTIRE-TIMI 23 showed that a much simpler thrombolytic regimen is feasible, permitting bolus administration of both TNKase and of adjunctive low-molecular-weight heparin.

This new regimen was tested in the pre-hospital phase of STEMI treatment in the ASSENT-3-PLUS study.32 In this trial, after electrocardiographic confirmation was obtained in the field, 1639 patients were treated with TNKase and randomly allocated to ENOX or UFH adjunctive treatment. Of interest, 53% of patients could be treated in the first 2 hours, a much higher proportion compared with that observed in previous studies. In the pre-hospital setting ENOX tended to reduce the composite of 30-day mortality or in-hospital reinfarction or in-hospital refractory ischemia (14.2% vs 17.4%, p = 0.08), but there was no difference in the efficacy plus safety end-point, also including the rate of ICH or major bleeding (18.3% vs 20.3%, p = NS). ENOX reduced the reinfarction rate (3.5% vs 5.8%, p = 0.028), but increased the rate of total stroke (2.9% vs 1.3%, p = 0.026) and of ICH (2.20% vs 0.97%, p = 0.047). The increase in ICH occurred in the group of patients more than 75 years old. A pre-specified pooled analysis of data from ASSENT-3 and ASSENT-3-PLUS trials largely confirmed the utility of using ENOX instead of UFH in conjunction with TNKase, reducing the primary efficacy end-point (composite of death, reinfarction and refractory ischemia) from 16.0% to 12.2%, p < 0.001 and the primary efficacy plus safety (ICH or major bleeding) end-point from 18.0% to 15.0%, p = 0.003.33 Among the 1049 patients who required urgent revascularization the ENOX beneficial effect was even larger (15.4% vs 10.1%, p = 0.013). The excess in stroke rates observed with ENOX (1.3% vs 0.9%), although not significant, was mainly due to an excess in ICH among women of more than 75 years old in ASSENT-3-PLUS.

Following these observations, the intravenous bolus of ENOX was omitted and the maintenance dose was reduced by 25% in patients of more than 75 years old in the large definitive confirmation EXTRACT-TIMI 25 trial.15

The role of the routine, immediate use of coronary angioplasty (so called “facilitated” angioplasty, F-PCI) after treatment with TNKase was first explored in CAPITAL-AMI.34 This was a small study randomizing 170 high-risk STEMI patients treated with TNKase toward immediate revascularization by PCI or to conservative management. The primary end-point was the composite of death, rein-farction, recurrent unstable ischemia, or stroke at 6 months. The median time from the onset of symptoms to TNKase administration was 120 minutes and the median time from symptoms to balloon inflation 204 minutes. Overall, the primary end-point was reduced by immediate PCI from 24.4% to 11.6% (p = 0.04), a result driven mainly by the reduction in the rate of recurrent unstable ischemia (p = 0.03). There were no differences in death, reinfarction, stroke or major bleeding.

These encouraging results stimulated the planning of the larger ASSENT-4 PCI trial,35 a trial designed to investigate whether TNKase facilitation would improve the prognosis of patients for whom a time-delay of 1 to 3 hours before P-PCI was anticipated. The trial design was open-label and the primary end-point was the composite of death or congestive heart failure or shock within 90 days. Only 1667 of the originally planned 4000 patients were enrolled, because the trial was prematurely interrupted by the data and safety monitoring board for an excess of in-hospital mortality in the group where P-PCI was facilitated by TNKase (6% vs 3%, p = 0.0105). The median time from TNKase injection to first balloon inflation was 104 minutes. A TIMI-3 flow was achieved before P-PCI in 43% of TNKase-treated patients and in 15% of patients in the control group (p < 0.0001). The primary end-point at 90 days was increased in the facilitated group (19% vs 13%, p = 0.0045), along with the stroke rate (1.8% vs 0%, p < 0.0001). These disappointing results have been attributed, in retrospect, to an alleged pro-thrombotic effect of TBL and, more convincingly, to the risk of creating an intra-plaque hemorrhage by inflating the balloon in the first 2 hours after TBL (ie, in a lytic state). In retrospect, the risk of death at 90 days was reduced by TNKase facilitation when patients were randomized in ambulance (relative risk 0.74, 95% CI 0.24–2.30) and mostly increased when patients were recruited in P-PCI capable hospitals (relative risk 1.62, 95% CI 0.94–2.81). These observation raise important methodological issues about ASSENT-4 PCI, since 45% patients were actually enrolled in P-PCI capable hospital, a design not exactly germane as to define what is the best strategy for the treatment of patients at the earliest point of care, particularly in the pre-hospital setting. This holds true particularly when considering that the trial was open-label.

More pertinent to investigating the role of TNKase facilitation is the WEST study,36 a randomized, open-label, feasibility study of 304 STEMI patients enrolled in the community (40% enrolled pre-hospital). All patients received aspirin and ENOX and were randomized to either TNKase, or to TNKase followed by PCI within 24 hours (including rescue PCI for reperfusion failure) or to P-PCI. The time from the onset of symptoms to randomization was 113, 130 and 176 minutes respectively. There were no differences between the three groups in the primary composite of death or reinfarction, refractory ischemia, congestive heart failure, cardiogenic shock or major ventricular arrhythmia (25% vs 24% vs 23%, p = NS). In the group receiving plain TNKase there was a higher rate of the death/reinfarction combination (13.0% vs 6.7% vs 4.0%, p = 0.021), but not of death (4.0% vs 1.0% vs 1.0%, p = NS).

Thus, the WEST trial confirms the data from CAPTIM:9 when delivered very rapidly, possibly in the pre-hospital phase, TNKase is very competitive with P-PCI and may offer a very simple and effective treatment, particularly if subsequent PCI is offered to those patients with recurrent ischemia or deemed at high clinical risk.

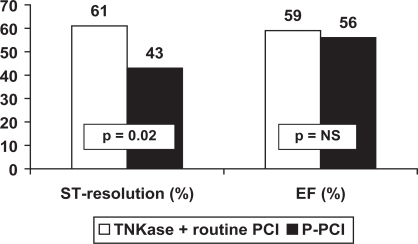

TNKase followed by early routine PCI (within 3–12 hours, so called “pharmaco-invasive” approach) has been compared with P-PCI in 212 patients enrolled in the GRACIA-2 study.37 This is a non-inferiority trial designed to evaluate whether a lytic strategy represents a reasonable option for STEMI patients, irrespective of geographic or logistic barriers, when compared with P-PCI. The primary end-points were epicardial and myocardial reperfusion and the extent of left ventricular damage (as assessed by infarct size and left ventricular function). Complete ST-segment resolution at the electrocardiogram was observed more frequently in the TNKase group (61% vs 43%, p = 0.01), implying an improved myocardial perfusion (as measured by the TIMI myocardial perfusion grade at 60 minutes).38 Infarct size and left ventricular ejection fraction were similar in the two groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ST-segment complete resolution after PCI and left ventricular ejection fraction in GRACIA-2.

P-PCI = Primary angioplasty.

It may be concluded that the results of the WEST study are confirmed by GRACIA-2, suggesting the comparable efficacy of TNKase (with rescue/routine PCI) and P-PCI.

Most relevant to pathophysiogy and clinical practice, is the finding of GRACIA-2 (in combination with ASSENT-4 PCI) that routine PCI after TNKase should be postponed at least 3 to 12 hours to achieve the benefit.

Conclusions

TNKase treatment of patients with STEMI is truly evidence-based.

More than 27,000 patients have been enrolled in several trials, by different investigators across the world, and addressing all major issues: strategy of reperfusion, comparison with other thrombolytic agents, choice of the best adjunctive anti-thrombotic treatment, and optimal patient management after drug injection.

For all the above considerations the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recognizes TNKase as a Class 1A recommendation in the treatment of STEMI patients within 12 hours from the onset of symptoms.39

There are indeed several reasons for choosing TNKase (Table 3): the easy way it may be used in ambulance (this use is also a Class IA ACCP recommendation), the high thrombolytic potency with a decreased risk of inducing major bleeds, and the really competitive results that may be expected for that majority of patients presenting in the first 3 hours, compared with P-PCI.

Table 3.

Reasons for using TNKase in STEMI patients

| TNKase is the most fibrin-specific thrombolytic agent available |

| TNKase may be injected by single intravenous bolus in 5–10 seconds |

| TNKase is as effective as accelerated rt-PA, but with less major bleeding |

| Pre-hospital TNKase (with rescue/routine PCI) seems as effective as primary angioplasty |

Indeed, TNKase is now embraced in many pre-hospital thrombolytic reperfusion protocols, such as the Vienna STEMI Registry,40 The Mayo Clinic STEMI Protocol,41 and The French FAST-MI registry.42

Therefore, a modern, TNKase-based “fibrinolytic strategy” is now offered to the health care system, which may overcome the huge logistic problems connected with the utopian, universal P-PCI implementation.

Pre-hospital TNKase is a real opportunity to offer timely reperfusion to as many patients as possible in an easy way, an opportunity that the health care system cannot miss.

Table 4 summarizes how TNKase is used in clinical practice.

Table 4.

How to use TNKase in STEMI patients

| Bolus intravenous injection of TNKase over 5–10 seconds |

|---|

| TNKase dose according to body weight (BW) |

| 30 mg if BW <60.0 kg |

| 35 mg if BW between 60.0 and 69.9 kg |

| 40 mg if BW between 70.0 and 79.9 kg |

| 45 mg if BW between 80.0 and 89.9 kg |

| 50 mg if BW ≥90.0 kg |

| Adjunctive anti-platelet therapy |

| Aspirin: 160–325 mg, followed by 75–162 mg per day, indefinitely |

| Clopidogrel: 75 mg per day (for at least 28 days if no stenting, 1 month |

| if using a bare metal stent, 1 year if using a drug eluting stent) |

| Initial clopidogrel dose: 300 mg if age ≤75 or if a stent is implanted |

| Adjunctive unfractionated heparin |

| Intravenous bolus: 60 U per kg (maximum 4000 U) |

| Intravenous infusion: 12 U per kg per hour (maximum 1000 U per hour) |

| Target activated partial thromboplastin time: 1.5–2.0 control |

| Treatment duration: minimum 48 hours |

| Adjunctive enoxaparin (only if serum creatinine <2.5 mg/dL in men, <2.0 in women): |

| Less than 75 years old: Intravenous bolus of 30 mg |

| Less than 75 years old: Subcutaneous injection of 1 mg/kg every 12 hours |

| At least 75 years old: No intravenous bolus |

| At least 75 years old: Subcutaneous injection of 0.75 mg/kg every 12 hours |

| If the creatinine clearance is <30 mL/min: subcutaneous injection every 24 hours |

| Treatment duration: for the duration of index hospitalization, up to 8 days |

| For patients undergoing PCI after TNKase |

| If on unfractionated heparin: additional boluses as needed |

| If on enoxaparin: no further anticoagulant if <8 hours from the subcutaneous injection |

| If on enoxaparin: additional intravenous bolus of 0.3 mg/kg if 8–12 hours |

| after the subcutaneous injection |

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. Focused Update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: Developed in Collaboration With the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Endorsed by the American Academy of Family Physicians: 2007 Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, Writing on Behalf of the 2004 Writing Committee. Circulation. 2007;2008;117:296–329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melandri G. Primary angioplasty or thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction? Lancet. 2003;361:966. 967–968. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12747-X. author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMaria AN. Lies, damned lies, and statistics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1430–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boden WE, Eagle K, Granger CB. Reperfusion Strategies in Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Comprehensive Review of Contemporary Management Options. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:917–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nallamothu BK, Bates ER, Herrin J, Wang Y, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM. Times to treatment in transfer patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI)-3/4 analysis. Circulation. 2005;111:761–767. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155258.44268.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jollis JG, Roettig ML, Aluko AO, et al. the Reperfusion of Acute Myocardial Infarction in North Carolina Emergency Departments (RACE) Investigators Implementation of a Statewide System for Coronary Reperfusion for ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2007;298:2371–2380. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.joc70124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vakili BA, Kaplan R, Brown DL. Volume-outcome relation for physicians and hospitals performing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction in New York state. Circulation. 2001;104:2171–2176. doi: 10.1161/hc3901.096668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnefoy E, Lapostolle F, Leizorovicz A, et al. Primary angioplasty versus prehospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction: a randomised study. Lancet. 2002;360:825–829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09963-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gale CP, Manda SOM, Batin PD, Weston CF, Birkhead JS, Hall AS. Predictors of in-hospital mortality for patients admitted with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a real-world study using the Myocardial Infarction National Audit Project (MINAP) database. Heart. 2008;94:1407–1412. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.127068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinto DS, Kirtane AJ, Nallamothu BK, et al. Hospital delays in reperfusion for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: implications when selecting a reperfusion strategy. Circulation. 2006;114:2019–2025. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates ER, Nallamothu BK. Commentary: the role of percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:567–573. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manari A, Ortolani P, Guastaroba P, et al. Clinical impact of an inter-hospital transfer strategy in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty: the Emilia-Romagna ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction network. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1834–1842. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. the CLARITY-TIMI 28 Investigators Addition of Clopidogrel to Aspirin and Fibrinolytic Therapy for Myocardial Infarction with ST-Segment Elevation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1179–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Antman EM, Morrow DA, McCabe CH, et al. the ExTRACT-TIMI 25 Investigators Enoxaparin versus Unfractionated Heparin with Fibrinolysis for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1477–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsikouris JP, Tsikouris AP. A review of available fibrin-specific thrombolytic agents used in acute myocardial infarction. Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21:207–217. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.2.207.34103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modi NB, Eppler S, Breed J, Cannon CP, Braunwald E, Love TW. Pharmacokinetics of a slower clearing tissue plasminogen activator variant, TNK-tPA, in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:134–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serebruany V, Malinin A, Callahan K, et al. Effect of tenecteplase versus alteplase on platelets during the first 3 hours of treatment for acute myocardial infarction: The Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Agent (ASSENT-2) platelet substudy. Am Heart J. 2003;145:636–642. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collen D, Stassen JM, Yasuda T, et al. Comparative thrombolytic properties of tissue-type plasminogen activator and of a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-resistant glycosylation variant, in a combined arterial and venous thrombosis model in the dog. Thromb Haemost. 1994;72:98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cannon CP, McCabe CH, Gibson CM, et al. TNK-tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. Results of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 10A dose-ranging trial. Circulation. 1997;95:351–356. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cannon CP, Gibson CM, McCabe CH, et al. TNK-tissue plasminogen activator compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: results of the TIMI 10B trial. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 10B Investigators. Circulation. 1998;98:2805–2814. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van de Werf F, Cannon CP, Luyten A, Houbracken K, McCabe CH, Berioli S, et al. Safety assessment of single-bolus administration of TNK tissue-plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-1 trial. The ASSENT-1 Investigators. Am Heart J. 1999;137:786–91. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70400-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giugliano RP, McCabe CH, Antman EM, Cannon CP, Van de Werf F, Wilcox RG, et al. Lower-dose heparin with fibrinolysis is associated with lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage. Am Heart J. 2001;141:742–750. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Single-bolus tenecteplase compared with front-loaded alteplase in acute myocardial infarction: the ASSENT-2 double-blind randomised trial. Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Investigators. Lancet. 1999;354:716–722. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van de Werf F, Barron HV, Armstrong PW, et al. Incidence and predictors of bleeding events after fibrinolytic therapy with fibrin-specific agents: a comparison of TNK-tPA and rt-PA. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:2253–2261. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinnaeve PA, Alexander JB, Belmans AC, et al. One-year follow-up of the ASSENT-2 trial: A double-blind, randomized comparison of single-bolus tenecteplase and front-loaded alteplase in 16,949 patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2003;146:27–32. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 Investigators Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with enoxaparin, abciximab, or unfractionated heparin: the ASSENT-3 randomised trial in acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2001;358:605–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05775-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antman EM, Louwerenburg HW, Baars HF, et al. the ENTIRE-TIMI 23 Investigators Enoxaparin as Adjunctive Antithrombin Therapy for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Results of the ENTIRE-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 23 Trial. Circulation. 2002;105:1642–1649. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013402.34759.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaul P, Armstrong PW, Cowper PA, et al. Economic analysis of the Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT-3) study: costs of reperfusion strategies in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2005;149:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giugliano RP, Roe MT, Harrington RA, et al. Combination reperfusion therapy with eptifibatide and reduced-dose tenecteplase for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Results of the integrilin and tenecteplase in acute myocardial infarction (INTEGRITI) Phase II Angiographic urial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1251–1260. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topol EJ. Reperfusion therapy for acute myocardial infarction with fibrinolytic therapy or combination reduced fibrinolytic therapy and platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition: the GUSTO V randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;357:1905–1914. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)05059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallentin L, Goldstein P, Armstrong PW, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in the prehospital setting: the Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 PLUS randomized trial in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:135–142. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081659.72985.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong PW, Chang WC, Wallentin L, et al. Efficacy and safety of unfractionated heparin versus enoxaparin: a pooled analysis of ASSENT-3 and -3 PLUS data. CMAJ. 2006;174:1421–1426. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le May MR, Wells GA, Labinaz M, et al. Combined angioplasty and pharmacological intervention versus thrombolysis alone in acute myocardial infarction (CAPITAL AMI study) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Treatment Strategy with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ASSENT-4 PCI) investigators Primary versus tenecteplase-facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (ASSENT-4 PCI): randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Armstrong PW, WEST Steering Committee A comparison of pharmacologic therapy with/without timely coronary intervention vs primary percutaneous intervention early after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the WEST (Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1530–1538. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Aviles F, Alonso JJ, Pena G, et al. Primary angioplasty vs early routine post-fibrinolysis angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: the GRACIA-2 non-inferiority, randomized, controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:949–960. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gibson CM, Karha J, Giugliano RP, et al. Association of the timing of ST-segment resolution with TIMI myocardial perfusion grade in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2004;147:847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goodman SG, Menon V, Cannon CP, Steg G, Ohman EM, Harrington RA. Acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. (8th Edition) 2008;133:708S–775S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalla K, Christ G, Karnik R, et al. Implementation of guidelines improves the standard of care: the Viennese registry on reperfusion strategies in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (Vienna STEMI registry) Circulation. 2006;113:2398–2405. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.586198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ting HH, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, et al. Regional systems of care to optimize timeliness of reperfusion therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Mayo Clinic STEMI Protocol. Circulation. 2007;116:729–736. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Danchin N, Coste P, Ferrieres J, et al. Comparison of thrombolysis followed by broad use of percutaneous coronary intervention with primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment-elevation acute myocardial infarction: data from the french registry on acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (FAST-MI) Circulation. 2008;118:268–276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.762765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]