Abstract

Summary: The analysis of gene regulatory networks (GRNs) is a central goal of bioinformatics highly accelerated by the advent of new experimental techniques, such as RNA interference. A battery of reverse engineering methods has been developed in recent years to reconstruct the underlying GRNs from these and other experimental data. However, the performance of the individual methods is poorly understood and validation of algorithmic performances is still missing to a large extent. To enable such systematic validation, we have developed the web application GeNGe (GEne Network GEnerator), a controlled framework for the automatic generation of GRNs. The theoretical model for a GRN is a non-linear differential equation system. Networks can be user-defined or constructed in a modular way with the option to introduce global and local network perturbations. Resulting data can be used, e.g. as benchmark data for evaluating GRN reconstruction methods or for predicting effects of perturbations as theoretical counterparts of biological experiments.

Availability: Available online at http://genge.molgen.mpg.de

Contact: hache@molgen.mpg.de

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Inferring gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from experimental data is a challenging task becoming increasingly important with routine practical use of corresponding experimental techniques, such as RNA interference combined with microarray or next generation sequencing. Various computational algorithms for reconstructing GRNs from experimental data have been developed in the last decades (see Supplementary Material for an overview). Besides the algorithmic developments, the actual assessment of methods performances remains a challenge, primarily due to the lack of experimental benchmark data. However, such systematic validation is crucial, since it shows strengths and weaknesses of the methods and their suitability for the specific problem domain (time series or perturbation experiments, noisiness of data, etc.).

Availability of experimental data, with a few exceptions, such as the network described by Davidson et al. (2002), is still the major bottleneck for GRN reconstruction. Hence, generating simulated data derived from theoretical considerations is still the method of choice for constructing benchmark datasets and for conducting performance studies on individual methods. These theoretical models should reflect features and complexity of real regulatory processes. They allow performance analysis under well-defined conditions using appropriate network characteristics, network complexity, noise levels, missing data or other hidden information. This knowledge can aid further algorithmic developments and guide improvements of experimental as well as analytical methods.

There are some tools that provide such forward GRN modeling approaches, such as SynTReN (den Bulcke et al., 2006), RENCO (Roy et al., 2008) or SynBioSS (Hill et al., 2008). However, despite of their usefulness they lack some features such as automatic generation of different network types, manipulation of network structure, simulation of global and local perturbation and visualization of simulation results in a single framework, specialized for GRNs (Supplementary Material).

To meet the above mentioned requirements, we have developed the GRN generator GeNGe (GEne Network GEnerator), a web application to model GRNs of different types. The GRNs are used to set up a deterministic ordinary differential equation (ODE) system. The gene regulatory model system is composed of instances of mRNAs and proteins acting as transcription factors (TFs) and their corresponding target genes. Non-linear kinetics based on the logic described by Schilstra and Nehaniv (2008) are used to describe the influence of sets of independently or jointly binding TFs on the expression of a gene. Various dynamics can be modeled, such as oscillation and bistability (Supplementary Material). Global perturbations (network noise) or local perturbations of a single or multiple network nodes can be simulated and the resulting time series are visualized in order to display the perturbation effects. All results can be downloaded and used for validation of reverse engineering methods or studies of the network dynamics.

Moreover, GeNGe offers features for the topological characterization of GRNs. Network parameters are computed, such as in- and out-degree distributions, average path lengths and clustering coefficients. Furthermore, by varying parameters of the kinetic laws or by choosing different kinetics, in silico analyses can be performed, e.g. on the effects of knock-downs (partial knock-downs) of a single gene or groups of genes. The results can be used to define critical network nodes and suitable candidates for perturbation experiments and thus guide future experimental work.

2 FUNCTIONALITY

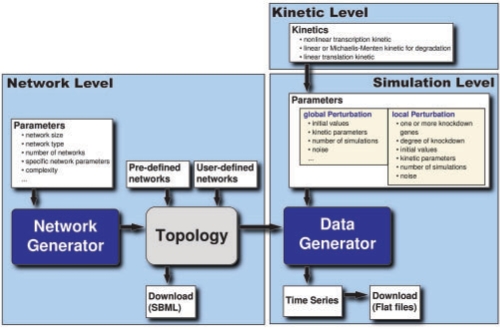

The workflow of GeNGe is divided into three levels (Fig. 1). In the first level, the network level, networks are added to a network repository that will be used for further analyses and simulations. GeNGe provides several pre-defined GRNs, such as a part of the developmental network in sea urchin described by Davidson et al. (2002), artificial networks and network motifs. Furthermore, the upload of user-defined networks, in form of tables or adjacency matrices, is supported. Various artificial networks can be generated such as random networks, scale free networks and networks composed of small regulatory network motifs (Barabási and Oltvai, 2004; Bollobás et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2002). Network parameters can be adjusted by the user to generate networks with specific topological characteristics. Furthermore, it is possible to change any network by adding or deleting nodes and edges as well as associated regulation strengths. TFs are assumed to bind independently on the DNA. Nevertheless, sets of jointly binding TFs can be specified. The networks can be visualized and diverse topological measures are calculated, e.g. in- and out-degree distributions, average path lengths and clustering coefficients.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the simulation process. It is divided into three levels, the network level, to generate a network topology; the kinetic level, to select kinetic laws of the dynamic model; and the simulation level, to set the parameter values and simulate time series with local or global perturbation.

In the next level, the kinetic level, kinetics of the model are specified. Degradation of mRNA and protein can be modeled by a linear or a Michaelis–Menten kinetic. The translation is described by a linear kinetic law. For the transcription dynamic, different non-linear kinetic laws can be selected. In the third level, the simulation level, parameters of individual kinetic laws can be specified or set randomly. Based on the network topology, the kinetics and the parameters, an ODE system of the network is set up and exported to PyBioS simulation engine via a web-services based API (Wierling et al., 2007). Besides unperturbed time series analysis, global perturbations (such as Gaussian noise) as well as single or multiple local network perturbations (e.g. knock-downs) can be introduced and the resulting steady states of the system are computed. The procedures can be repeated with different settings and used in an iterative way.

All resulting time series can be visualized. For knock-down experiments, the ratio of each network node of the knock-down and control simulations is calculated and visualized in the network graph. All results, including the networks in the format of Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML), time series and simulation parameters can be downloaded for further analyses. More details about the network and data generator is given in the Supplementary Material.

3 EXAMPLE

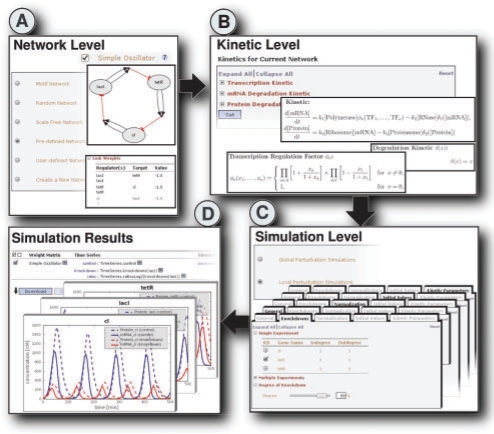

An Example workflow in GeNGe is shown in Figure 2 which is adapted from the synthetic repressilator by Elowitz and Leibler (2000). The pre-defined network ‘Simple Oscillator’ is added to the network repository. A local perturbation of gene lacI is introduced with a knock-down degree of 80%. The control and knock-down time series are calculated. The oscillations of the mRNAs and proteins are still observable with this rate of knock-down, however, there are changes in frequency and amplitude. A breakdown of the oscillations is observable at 97% rate of knock-down (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Example workflow in GeNGe. (A) Pre-defined network ‘Simple Oscillator’ is selected. (B) A kinetic schema for transcription and degradation is specified. (C) Local perturbations (knock-down) of gene lacI of degree 80% is selected. (D) Simulated time courses of the mRNA and proteins for control (blue) and knockdown (red) can be visualized or downloaded.

Whereas the effect of local perturbations is straightforward in small networks, in larger networks the impact of such perturbations on the steady state of the system is less obvious and thus simulations can guide experimental work in selecting the most promising candidates. An example given in the Supplementery Material shows that knock-downs of genes encoding highly connected TFs with many targets have not always a large impact on the global system state. In contrast, TFs with critical positions within the network can have a large downstream effect even if they have only a few direct targets.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Maria Schilstra for valuable comments on the kinetics.

Funding: Max Planck Society and the EU under its sixth Framework Programme [grants EMBRACE (LSHG-CT-2004-512092), AnEUploidy (LSHG-CT-2005-037627), the seventh Framework Programme project APO-SYS (HEALTH-F4-2007-200767)]; German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the NGFN Plus research initiative (Mutanom project (01GS08105)).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Barabási A-L, Oltvai ZN. Network biology: understanding the cell's functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollobás B, et al. SODA'03: Proceedings of the fourteenth annual ACM-SIAM symposium on Discrete algorithms. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics; 2003. Directed scale-free graphs; pp. 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH, et al. A genomic regulatory network for development. Science. 2002;295:1669–1678. doi: 10.1126/science.1069883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bulcke TV, et al. Syntren: a generator of synthetic gene expression data for design and analysis of structure learning algorithms. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowitz MB, Leibler S. A synthetic oscillatory network of transcriptional regulators. Nature. 2000;403:335–338. doi: 10.1038/35002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill AD, et al. Synbioss: the synthetic biology modeling suite. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2551–2553. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, et al. Transcriptional regulatory networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;298:799–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1075090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, et al. A system for generating transcription regulatory networks with combinatorial control of transcription. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1318–1320. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilstra MJ, Nehaniv CL. Bio-logic: gene expression and the laws of combinatorial logic. Art. Life. 2008;14:121–133. doi: 10.1162/artl.2008.14.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierling C, et al. Resources, standards and tools for systems biology. Brief. Funct. Genomic Proteomic. 2007;6:240–251. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.