Abstract

Background

Airways obstruction in premature infants is often assessed by plethysmography, which requires sedation. The interrupter (Rint) technique does not require sedation, but has rarely been examined in children under 2 years of age.

Objective

To compare Rint results with plethysmographic measurements of airway resistance (Raw) in prematurely born, young children.

Design

Prospective study.

Setting

Infant and Paediatric Lung Function Laboratories.

Patients

Thirty children with a median gestational age of 25–29 weeks and median postnatal age of 13 months.

Interventions and main outcome measures

The infants were sedated, airway resistance was measured by total body plethysmography (Raw), and Rint measurements were made using a MicroRint device. Further Raw and Rint measurements were made after salbutamol administration if the children remained asleep.

Results

Baseline measurements of Raw and Rint were obtained from 30 and 26 respectively of the children. Mean baseline Rint values were higher than mean baseline Raw results (3.45 v 2.84 kPa/l/s, p = 0.006). Limits of agreement for the mean difference between Rint and Raw were −1.52 to 2.74 kPa/l/s. Ten infants received salbutamol, after which the mean Rint result was 3.6 kPa/l/s and mean Raw was 3.1 kPa/l/s (limits of agreement −0.28 to 1.44 kPa/l/s).

Conclusion

The poor agreement between Rint and Raw results suggests that Rint measurements cannot substitute for plethysmographic measurements in sedated prematurely born infants.

Keywords: airways resistance, interrupter technique, premature, plethysmography

Prematurely born infants often have a troublesome wheeze at follow up, particularly in the first two years after birth. It is therefore important to assess the degree of airways obstruction, and plethysmographic measurement of airways resistance is usually performed.1,2 Many other interventions are carried out in the neonatal period with the aim of improving pulmonary outcome, and plethysmographic measurements have been used to provide an objective assessment of their effect.3 Unfortunately very young children must be sedated for plethysmographic measurements, and this limits their acceptability to parents, resulting in loss to follow up.3 It is therefore important to find a way of measuring airways obstruction in premature infants that does not require sedation and yields reliable information. A possibility is the interrupter technique (Rint), which has been used to assess airways obstruction in older children.4,5,6,7 Many studies have concentrated on its possible research and clinical role in preschool children.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 There are, however, limited data from children less than 2 years of age. In this age group, after the first few months after birth, comparison of Rint results with standard techniques requires assessment in a sedated population. Results using the Rint technique have been compared with measurements of single‐breath lung mechanics and results of the forced partial expiratory flow volume technique in sedated infants, all less than 18 months of age.20 Satisfactory Rint measurements could only be made in 25 of the 37 infants, but significant correlations were shown between the Rint results and both single‐breath resistance measurements and maximum flow at functional residual capacity (correlations of 0.7 and 0.63 respectively).20 Although Rint measurements have been compared with plethysmographic airway measurements in school age children,4 there are no similar comparisons in very young children.21 The aim of this study therefore was to compare Rint measurements with airway resistance measured by total body plethysmography (Raw) in very prematurely born children less than 2 years of age.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Children who were attending for pulmonary function follow up at 1 year corrected age as part of the United Kingdom oscillation study (UKOS; prophylactic high frequency oscillatory ventilation versus conventional ventilation in very preterm infants)22 were recruited into this study. The study was approved by the King's College Hospital Ethics Committee, and parents gave informed written consent for their child to take part. All of the infants entered into the UKOS were born at less than 29 weeks gestation. Measurements were attempted on 30 children with a median gestational age of 25.9 weeks (range 23–28.9) and a median corrected postnatal age of 13 months (range 11–14).

Study design

The children were seen in the Infant and Paediatric Respiratory Lung Function Laboratories. A history was taken and the children were examined. No child was measured within two weeks of a respiratory infection. If no respiratory abnormalities indicating acute infection were found on examination, the children were sedated with chloral hydrate syrup (80 mg/kg). Those not asleep within 30 minutes received an additional 40 mg/kg chloral hydrate. Once asleep, measurements of Raw and then Rint were made. Children who remained sedated after the baseline measurements were given salbutamol (200 μg) using a spacer device and face mask (Volumatic; Allen & Hanbury, London, UK). Further Raw then Rint measurements were made. Rint measurements were always made after Raw measurements, as the Raw data collection was essential for a larger study.3

Methods

The child was placed in a 90 litre total body plethysmograph (Department of Medical Engineering, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK), and a Rendell‐Baker face mask was lowered on to the face. A rim of silicone putty was used to obtain an airtight seal around the nose and mouth. The rim of the facemask supported the cheeks during the measurements. Details of the plethysmograph and calibration techniques are given elsewhere.23 The plethysmograph was sealed, and functional residual capacity (FRCpleth) measured from a minimum of three end inspiratory occlusions. Raw was then determined from a minimum of five technically acceptable breaths. The median number of breaths per child analysed before and after bronchodilator administration was 9.5 and 10 respectively. The FRCpleth and Raw results were calculated using software developed for the laboratory. Raw results were obtained from a best fit regression line drawn through the first 50% of the inspiratory flow/plethysmograph pressure trace.23 Only breaths in which the loop was closed or nearly closed at points of zero flow were used for the analysis.23 The plethysmograph was then opened, and Rint measured with the Rint device (MicroRint; Micromedical Ltd, Rochester, Kent, UK). The Rint device was set to trigger at peak inspiratory flow. The Rint values were calculated automatically by the device. The pressure plateau was regressed back to the time of occlusion from pressure measurements 30 and 70 milliseconds after the occlusion. The flow used was that immediately before the occlusion. If there was an obvious leak or the pressure trace after the immediate oscillations was not linear,18 the occlusion was deemed unsatisfactory and discarded. The Rint device makes 10 occlusions in succession for each test. Only the results from children in whom at least five satisfactory occlusions were made were included in the analysis. If there were fewer than five satisfactory occlusions from the first set of measurements, then a further set of occlusions was repeated. The median number of occlusions per child analysed before and after bronchodilator administration was 7.5 and 9.0 respectively.

Analysis

For each child, the mean (SD) Raw and Rint values were calculated from the respective repeated measures, and the within infant coefficient of variation thus derived (100% × (SD/mean)). Raw and Rint data were both approximately normally distributed, but Rint data had a very slight skew, which was not corrected by transformation, and so analyses based on normal distribution were used. Coefficients of variation were calculated for Raw and Rint to assess within individual reliability. The within child difference between the Rint and Raw values was tested for significance using the t test. The agreement between the Raw and Rint measurements was estimated using the Bland‐Altman limits of agreement method.24 The limits of agreement were calculated using mean difference ± t × SD, where t is the 5% point of the t distribution. These provide an estimate of the minimum and maximum likely difference between the two measurements and thus provide quantitative information on the extent of the agreement. Pearson's correlation coefficients were also calculated to allow comparison with data from a study that evaluated the interrupter technique in comparison with plethysmographic assessment of airway resistance in children.4

Results

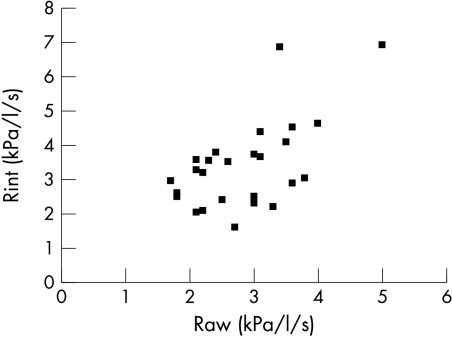

Satisfactory Raw and Rint baseline measurements were obtained in 26 of 30 children (table 1, fig 1). Technically acceptable loops for Raw measurements were obtained in all 30 children. Four children had fewer than five satisfactory Rint results, because they woke up during the measurements. The Rint values tended to be higher than the Raw values (mean (SD) Rint 3.45 (1.29) kPa/l/s; mean (SD) Raw 2.84 (0.80) kPa/l/s; p = 0.006). The mean coefficients of variation were 12.4% for Rint and 12.6% for Raw baseline results. After the baseline measurements, ten children remained asleep and were studied again after bronchodilator administration. This subgroup had mean baseline Rint and Raw results of 3.75 (1.46) and 3.17 (0.95) kPa/l/s respectively. After salbutamol administration, the respective mean Rint and Raw results were 3.63 (1.30) and 3.05 (1.14) kPa/l/s. The change in neither Raw nor Rint after bronchodilator administration was significant.

Table 1 Comparison of the characteristics and Rint and Raw results of the study population, the infants with satisfactory Rint results, and the infants measured after salbutamol administration.

| Study population | Infants with satisfactory Rint results | Infants measured after salbutamol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 30 | 26 | 10 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 25.9 (1.6) | 26.0 (1.6) | 25.5 (1.3) |

| Birth weight (g) | 814 (205) | 836 (212) | 768 (152) |

| At the time of testing | |||

| Corrected age (months) | 12.8 (1.1) | 12.8 (1.1) | 13.0 (0.8) |

| Weight (kg) | 8.9 (1.3) | 9.0 (1.2) | 9.0 (1.2) |

| Length (cm) | 74.5 (3.2) | 74.9 (2.9) | 74.9 (3.7) |

| Before bronchodilator | |||

| FRCpleth (ml/kg) | 26.1 (5.9) | 26.1 (5.9) | 23.9 (4.1) |

| Raw (kPa/l/s) | 3.01 (1.01) | 2.84 (0.80) | 3.17 (0.95) |

| Rint (kPa/l/s) | – | 3.45 (1.29) | 3.75 (1.46) |

| After bronchodilator | |||

| Raw (kPa/l/s) | – | – | 3.05 (1.14) |

| Rint (kPa/l/s) | – | – | 3.63 (1.30) |

Values are mean (SD).

Raw, airways resistance measured by plethysmography; Rint, interrupter resistance; FRCpleth, functional residual capacity measured by plethysmography.

Figure 1 Plot of interrupter resistance (Rint) and airways resistance (Raw) values from the 26 infants in whom both Rint and Raw values were successfully obtained before bronchodilator administration.

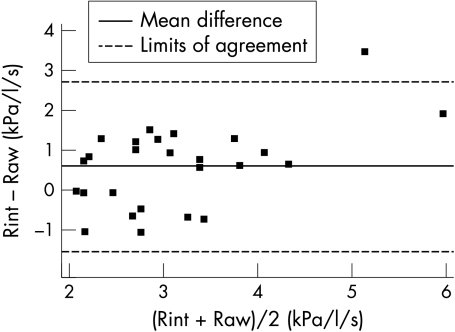

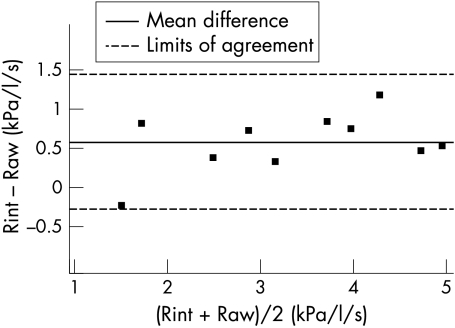

The mean difference between Rint and Raw (Rint − Raw) results in children with satisfactory baseline measurements was 0.61 (1.03) giving limits of agreement of –1.52 to 2.74 kPa/l/s (fig 2). For those children who received salbutamol, the mean difference between the Rint and Raw results after salbutamol administration was slightly smaller with less variability between subjects (0.58 (0.38)) giving narrower limits of agreement of –0.28 to 1.44 kPa/l/s (fig 3). The correlation coefficients of Raw and Rint results were 0.60 in the 26 children with paired measurements before bronchodilator administration and 0.96 in the 10 children who had paired measurements after bronchodilator administration.

Figure 2 Bland and Altman plot showing the mean difference and limits of agreement of the Rint and Raw results before bronchodilator administration (n = 26). Limits of agreement are 0.61 ± 2.06 × 1.03, where 2.06 is the two sided 5% point for the t distribution with 25 degrees of freedom.

Figure 3 Bland and Altman plot showing the mean difference and limits of agreement of the Rint and Raw results after bronchodilator administration (n = 10). Limits of agreement are 0.58 ± 2.26 × 0.38, where 2.26 is the two sided 5% point for the t distribution with 9 degrees of freedom.

Discussion

We here show poor agreement between Rint and Raw results in sedated very prematurely born, young children. Very premature children were chosen as the study population, because they are often symptomatic at follow up and require respiratory function assessment. In addition, we expected them to have a wide range of resistance values and could therefore make an extensive comparison of Rint and Raw results (fig 1). The correlation coefficient after bronchodilator administration was similar to that reported when Rint results were compared with Raw results obtained by plethysmography (r = 0.91). Such high correlations can be expected, as the techniques assess related aspects of lung function, and correlations therefore do not show the level of agreement. A more appropriate method for determining if the results of two techniques are in agreement is Bland and Altman analysis.24 Using this analysis, we showed poor agreement between the two techniques.

It was possible to obtain at least five satisfactory Rint baseline results in 26 of the 30 children. Those for whom five acceptable Rint results were not obtained all woke from their sedation during the measurement sequence. In all the children who remained asleep, five acceptable Rint results were obtained, confirming that the Rint technique is easy to use in sedated patients.20

The baseline Rint values were on average 0.61 kPa/l/s higher than the Raw results, as has been found in school aged children.4 An explanation for this difference is that Rint measurements are claimed to include a component from the chest wall and possibly a lung tissue component.4 A further explanation for the difference is that the former were made at peak inspiratory flow, whereas the latter were calculated from the best fit up to 50% of peak flow. At peak inspiratory flow, flow is more likely to be turbulent than laminar, resulting in higher resistance values. We deliberately chose to make inspiratory interruptions as we wished to compare the results of the Rint technique with plethysmographic measurements. Inspiratory rather than expiratory airways resistance has usually been assessed by plethysmography when being used to determine the respiratory function of very young children.

We report the first comparison of the reproducibility of these two techniques in children younger than 2 years of age. The reproducibility of the techniques was not calculated by obtaining mean values before and after replacing the facemask or before and after the child had been taken out of the plethysmograph, because the extra time required would have precluded the study of the children before and after salbutamol administration. The reproducibility of the measurements was determined by calculating a coefficient of variation for each measurement (a minimum of five on each occasion). The two techniques were found to have similar reproducibility. However, measurements during expiration may be more sensitive in detecting pathological airway patency.

For logistical reasons, we did not randomise the order of measurement technique, and it is possible that the sleep stage of the infants varied during the course of each study, affecting the reproducibility of the techniques. However, we do not feel that variation in the sleep state of the children influenced the Rint and Raw results. Although it had been suggested that sleep state affects lung volume25 and hence may affect Rint and Raw, subsequent studies showed that sleep stage had no affect on lung volume.26,27 It is of interest that the results of the two techniques used in our study differed less when the measurements were made after rather than before bronchodilator administration—that is, in the infants who remained asleep longer. Nevertheless, the Rint and Raw results differed significantly even in those infants who were measured after bronchodilator administration and were asleep the longest.

What is already known on this topic

Prematurely born young children often have a troublesome wheeze at follow up

The interrupter technique (Rint) assesses airway obstruction and is potentially attractive as it can be performed without sedation, but no comparisons have been made with the standard method of assessing airway obstruction in premature infants (plethysmography)

What this study adds

Poor limits of agreement of the results of the two techniques were shown in sedated prematurely born young children

This suggests that Rint measurements using the microRint technique cannot substitute for plethysmographic measurements of airway resistance in such children

In conclusion, these results show that the Rint technique is easy to use in sedated infants. There was, however, poor agreement between Rint and Raw results in sedated very premature infants. Rint results are influenced by the method of measuring pressures from the recording. The device we used determines the pressure by back regression from 70 to 30 milliseconds; there are, however, other ways of determining the pressure.18,19 It is therefore important to emphasise that our results pertain to a particular method of measuring Rint and the plethysmographic technique we used to assess airways obstruction. Our results show that Rint measured by the MicroRint method cannot substitute for plethysmographic measurements of airway resistance.

Acknowledgements

MRT and UKOS were supported by the Medical Research Council.

Abbreviations

Raw - airways resistance measured by total body plethysmography

Rint - interrupter resistance

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Yuksel B, Greenough A, Naik S.et al Perinatal lung function and invasive procedures. Thorax 199752181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuksel B, Greenough A. Airway resistance and lung volume before and after bronchodilator therapy in symptomatic preterm infants. Respir Med 199488281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas M, Rafferty G, Limb E.et al Pulmonary function at follow up of very preterm infants from the UK oscillation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200469868–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter E R, Stecenko A A, Pollock B H.et al Evaluation of the interrupter technique for the use of assessing airway obstruction in children. Pediatr Pulmonol 199417211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan E Y, Bridge P D, Dundas I.et al Repeatability of airway resistance measurements made using the interrupter technique. Thorax 200358344–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delacourt C, Lorino H, Fuhrman C.et al Comparison of the forced oscillation technique and the interrupter technique for assessing airway obstruction and its reversibility in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001164965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oswald‐Mammosser M, Lierena C, Speich J P.et al Measurements of respiratory system resistance by the interrupter technique in healthy and asthmatic children. Pediatr Pulmonol 19972478–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klug B, Bisgaard H. Measurement of lung function in awake 2–4 year old asthmatic children during methacholine challenge and acute asthma: a comparison of the impulse oscillation technique, the interrupter technique and transcutaneous measurement of oxygen versus whole‐body plethysmography. Pediatr Pulmonol 199621290–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klug B, Nielsen K G, Bisgaard H. Observer variability of lung function measurements in 2–6 year old children. Eur Respir J 200016472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beydon N, Amsallem F, Bellet M.et al Pulmonary function tests in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20021661099–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beydon N, Amsallem F, Bellet M.et al French Pediatric Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique Group. Pre/postbronchodilator interrupter resistance values in healthy young children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20021651388–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bisgaard H, Klug B. Lung function measurements in awake young children. Eur Respir J 199582067–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Child F, Clayton S, Davies S.et al How should airways resistance be measured in young children: mask or mouthpiece. Eur Respir J 2001171244–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lombardi E, Sly P D, Concutelli G.et al Reference values of interrupter respiratory resistance in healthy preschool white children. Thorax 200156691–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenzie S A, Bridge P D, Healy M J. Airway resistance and atopy in preschool children with wheeze and cough. Eur Respir J 200015833–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merkus P J, Mijnsbergen J Y, Hop W C.et al Interrupter resistance in preschool children: measurement characteristics and reference values. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20011631350–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen K G, Bisgaard H. The effect of inhaled budesonide on symptoms, lung function and cold air and methacholine responsiveness in 2 to 5 year old asthmatic children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 20001621500–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phagoo S B, Wilson N M, Silverman M. Evaluation of the interrupter technique for measuring change in airway resistance in 5 year old asthmatic children. Pediatr Pulmonol 199520387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall G L, Wildhaber J H, Cernelc M.et al Evaluation of the interrupter technique in healthy unsedated infants. Eur Respir J 200118982–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chavasse R J, Bastian‐Lee Y, Seddon P. Comparison of resistance measured by the interrupter technique and by passive mechanics in sedated infants. Eur Respir J 200118(2)330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klug B, Bisgaard H. Specific airway resistance interrupter resistance and respiratory impedance in healthy children aged 2–7 years. Pediatr Pulmonol 199825322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson A H, Peacock J L, Greenough A.et al United Kingdom Oscillation Study Group. High‐frequency oscillatory ventilation for the prevention of chronic lung disease of prematurity. N Engl J Med 2002347633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas M, Greenough A, Blowes R.et al Airway resistance estimation by best fit analysis in very premature infants. Physiol Meas 200223279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bland J M, Altman D G. Statistical methods for assessing the agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986i307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson‐Smart D J, Read J C. Reduced lung volume during behavioural active sleep in the newborn. J Appl Physiol 1979461081–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stokes G M, Milner A D, Newball E A.et al Do lung volumes change with sleep state in the neonate? Eur J Pediatr 1989148360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beardsmore C S, MacFadyen U M, Moosavi S S.et al Measurement of lung volumes during active and quiet sleep in infants. Pediatr Pulmonol 1989771–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]