Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the use of a new transcutaneous bilirubinometer (JM‐103 Minolta Airshields) for detection of hyperbilirubinaemia in term or near‐term healthy Chinese newborns.

Methods

Transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) was used to screen for severe hyperbilirubinaemia in newborn infants. Blood was taken for total serum bilirubin (TSB) measurement if the initial TcB level was higher than the 40th centile in Bhutani's nomogram. Paired TcB and TSB results were then reviewed over 6 months. The correlation as well as the mean difference between the two methods were calculated. The clinical application of TcB with Bhutani's nomogram in the prediction of severe hyperbilirubinaemia in low‐risk, medium‐risk and high‐risk thresholds for phototherapy was also analysed.

Results

997 paired TcB and TSB measurements were evaluated in term or near‐term newborns. TcB was significantly correlated with TSB, with a correlation coefficient of 0.83 (p<0.001). Their mean difference was 21.7 μmol/l (SD 21.2, p<0.001), with the 95% limits of agreement between −19.9 and 63.3 μmol/l. In both low‐risk and medium‐risk thresholds for phototherapy, using the 75th centile of Bhutani's nomogram as threshold, TcB could identify all cases and had a sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100% each, a specificity of 56% and positive predictive value of 23%. For high‐risk cases, using the 75th centile as cut‐off, the sensitivity and negative predictive value were reduced to 86.7% and 97.0%, respectively.

Conclusion

An accurate point‐of‐care bilirubin analyser facilitates bilirubin screening and avoids unnecessary blood tests. Although using the transcutaneous bilirubinometer JM‐103 might result in a significant difference between TcB and TSB measured in Chinese newborns, combining the use of TcB and the 75th centile in Bhutani's nomogram as the cut‐off level can identify all cases of significant hyperbilirubinaemia.

Neonatal jaundice is one of the most common diseases during the early neonatal period. In the US, 15.5% of Caucasian newborns develop jaundice with peak total serum bilirubin (TSB) concentration >204 μmol/l (12 mg/dl).1 Neonatal jaundice is more prevalent in the Asian population. A study in Hong Kong showed that 23.9% of Chinese newborns had a peak TSB >204 μmol/l.2 The clinical pattern of the “physiological jaundice” in Chinese infants is also different. Physiological jaundice in Chinese infants is more intense (higher maximum TSB) than the “classic physiologic jaundice”, with the peak level 1 day later and lasting much longer.3 However, despite the delayed onset of neonatal jaundice in Chinese newborns, early discharge of newborns has become more common in Hong Kong. This makes detection and prevention of severe hyperbilirubinaemia more difficult. Visual assessment for jaundice severity can be unreliable, transcutaneous bilirubinometry, a screening tool first introduced in Japan4,5 can help in detection. Routine use of jaundice meters has been shown to reduce the cost and need for TSB measurements,6,7 and decrease the readmission rate for hyperbilirubinaemia.8,9

In 2004, the American Academy of Pediatrics10 recommended pre‐discharge measurement of the bilirubin level using TSB or transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) or assessment of clinical risk factors. The best‐documented method for assessing the risk of developing subsequent hyperbilirubinaemia was to measure the TSB or TcB levels and plot the results on a nomogram.11 Phototherapy would be implemented according to the TSB level and risk levels (low, medium and high) at specific hours of life.10

The JM‐102 transcutaneous bilirubinometer (Minolta AirShields, Chuo‐Ku, Osaka, Japan) has always been used in our postnatal nursery for screening of neonatal jaundice. TSB is checked if the TcB index over the sternum is high. One of the disadvantages of the JM‐102 is that it provides only a TcB index instead of the serum bilirubin level. The TSB level is derived from the TcB index on the basis of data obtained from individual hospital laboratories. It performs best when measurements are made at the sternum. Each institution has to develop its own correlation curve of TcB to TSB.12 Moreover, the reading with the JM‐102 has been shown to be markedly affected by skin pigmentation, and age and weight of the newborn.13

A new device, the JM‐103 (Minolta Airshields), was introduced in 2003. It measures the spectral reflectance of bilirubin by determining the difference between optical densities for light in the blue (450 nm) and green (550 nm) wavelengths—a dual optical path system. The measurement of bilirubin accumulated primarily in the deeper subcutaneous tissue should decrease the influence of other pigments in the skin, such as melanin and haemoglobin. The device gives a direct TcB measurement in terms of μmol/l or mg/dl, which allows direct interpretation. Yasuda et al14 found an excellent correlation (r = 0.94) between the JM‐103 and TSB. This new jaundice meter had also been evaluated by Maisels et al15 in 849 term or near‐term newborns (gestation >35 weeks), with racial distribution of white (59.2%), black (29.8%), Asian‐American (4.5%), Middle Eastern (1.6%), Indian–Pakistani (1.6%) and Hispanic (1.1%) groups. The authors showed that there was an overall significant correlation between TcB and TSB (r = 0.915). The difference between TSB and TcB was <34.2 μmol/l in 98% of the measurements. However, there was a limitation in their study. Only 4.5% of his study population had an Asian background, a well‐known risk factor for neonatal jaundice. Therefore, further evaluation in the use of this new jaundice‐testing device for our predominantly Chinese newborns is necessary.

Methods

Since 2005, the JM‐103 transcutaneous bilirubinometer has been used at the postnatal nursery in Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Hong Kong SAR, China. TcB measurements were taken with the JM‐103 transcutaneous bilirubinometer (Minolta Airshields) once over the mid‐sternum area for all healthy term or near‐term newborns with a gestational age of >35 weeks every morning in our postnatal nursery. Sick newborns who required admission to our special care baby or neonatal intensive care unit were excluded from the study. A single JM‐103 transcutaneous bilirubinometer was used for all TcB measurements. The first of three measurements with the JM‐103 provided results similar to their average; therefore, one TcB reading should suffice.15 As rapid bilirubin kinetics and distribution during phototherapy reduce correlation, infants who had received phototherapy were also excluded.16

Paired TSB measurements were checked within 30 min if the initial TcB level was above the 40th centile level in the Bhutani nomogram.11 TSB was not measured if the TcB was less than the 40th centile. TSB assay was carried out in our main laboratory using the UNISTAT reflectance bilirubinometer (Reichert‐Jung, Buffalo, NY, USA), a photometric analyser for determining total bilirubin concentration in newborn infants. The result correlates well (96–99%) with the high‐performance liquid chromatography gold standard, and the performance of the bilirubinometer is regularly monitored by the quality assurance programme under the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Neonatal Bilirubin Program.16a Target values of the programme were set using the Doumas Total Bilirubin Reference Method calibrated using the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Standard Reference Materials 916a bilirubin calibrator.17

This is a retrospective study of the TcB meter (JM‐103) used in term or near‐term healthy Chinese newborns born between April and September 2005. During 2005, 3869 infants were born in our hospital; 460 infants developed severe hyperbilirubinaemia that required phototherapy, with a pretest probability of 11.9%. The study was approved by the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Hong Kong.

Statistical analysis

SPSS V.11.5 was used for statistical analysis. The correlation between TcB values and TSB measurements was determined by Pearson's linear regression analysis. As the correlation coefficient between TSB and TcB alone can be misleading, the magnitude of the error distribution (mean difference (d) between TSB and TcB) as well as the 95% limits of agreement (d+1.96 SD, d–1.96 SD) were determined using the Bland and Altman method18 and the paired Student's t test. In accordance with the assumption of independence in the Bland and Altman plot, only the first paired sample of each baby was used for analysis.

Along with the use of Bhutani's nomogram, the clinical values of TcB (JM‐103) for prediction of severe hyperbilirubinaemia above the low‐risk, medium‐risk and high‐risk thresholds for phototherapy according to the American Academy of Pediatrics10 were determined. The likelihood ratios of TcB levels in different hour‐specific risk zones of Bhutani's nomogram (40th to 75th, 75th to 95th and >95th centiles) above the different thresholds for phototherapy were then calculated.

Results

During the study period, a total of 4689 TcB measurements were taken from 1889 term or near‐term infants. Of these, 1798 (95.2%) infants were Chinese; 1621 TcB measurements were greater than the 40th centile, so paired TSB measurements were taken in 997 newborns (median gestation age 39 weeks, range 35–42 weeks). As discussed in the previous section, only the first paired measurement results—that is, 997 paired measurements—were analysed. Most of them (97%) were taken within the first 3 days of life. The median age of paired TcB and TSB measurements was 32.9 h of life (range 12.1–139.6 h). Figure 1 shows the distribution with respect to age in day(s) of life.

Figure 1 Distribution of paired transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) and total serum bilirubin (TSB) measurement with respect to age of neonates.

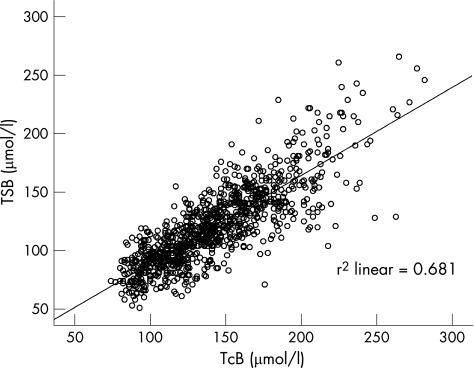

The TSB concentrations ranged from 51 to 266 μmol/l. Three neonates had TSB >250 μmol/l. Pearson's correlation coefficient between TcB and TSB was 0.83 (p<0.001; fig 2). The mean difference (d) between TcB and TSB levels was 21.7 μmol/l (SD 21.2, p<0.001). The 95% limits of agreement (d+1.96 SD, d−1.96 SD) were −19.9 and 63.3 μmol/l. The difference between TcB and TSB (ie, TcB–TSB) and the 95% limits of agreement was plotted against the mean of TcB and TSB (fig 3). The range of difference increased in patients with TSB level >200 μmol/l.

Figure 2 Transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) versus total serum bilirubin (TSB) scatter diagram.

Figure 3 (TcB+TSB)/2 versus (TcB–TSB) scatter diagram. TcB, transcutaneous bilirubin; TSB, total serum bilirubin.

If the low‐risk threshold for severe hyperbilirubinaemia was used for analysis, the sensitivity and NPV of the 40th centile track were both 100%. If the 75th centile track was used for prediction, the sensitivity and NPV were also 100%, whereas the specificity and PPV were 55.7% and 23.4%, respectively. The 95th centile track also achieved a sensitivity and NPV of 100% each, with a better specificity and PPV of 90.4% and 58.5%, respectively (table 1).

Table 2 Statistical analysis for phototherapy with medium‐risk threshold .

| TcB category | Phototherapy (medium risk) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % | NPV, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| >40% | 8 | 989 | 100 | 0 | NA | NA |

| ⩽40% | 0 | 0 | (67.6 to 100) | (0 to 0.39) | ||

| >75% | 8 | 434 | 100 | 56.1 | 23.5 | 100 |

| ⩽75% | 0 | 555 | (67.6 to 100) | (53.0 to 59.2) | ||

| >95% | 6 | 92 | 75.0 | 90.7 | 52.1 | 96.4 |

| ⩽95% | 2 | 897 | (40.9 to 92.9) | (88.7 to 92.4) | ||

NA, not available; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TcB, transcutaneous bilirubin.

If the medium‐risk threshold was used for prediction, the sensitivity and negative predictive value (NPV) of using the 40th and 75th centile tracks for prediction were both 100%. On the other hand, the sensitivity and NPV for the 95th centile track were reduced to 75% and 96.4%, whereas the specificity and PPV were 90.7% and 52.1%, respectively (table 2).

Table 3 Statistical analysis for phototherapy with high‐risk threshold.

| TcB category | Phototherapy (higher risk) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % | NPV, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| >40% | 60 | 937 | 100 | 0 | NA | NA |

| ⩽40% | 0 | 0 | (94.0 to 100) | (0 to 0.41) | ||

| >75% | 52 | 390 | 86.7 | 58.4 | 22.0 | 97.0 |

| ⩽75% | 8 | 547 | (75.8 to 93.1) | (55.2 to 61.5) | ||

| >95% | 27 | 70 | 45.0 | 92.7 | 45.1 | 92.6 |

| ⩽95% | 33 | 867 | (33.1 to 57.5) | (90.7 to 94.0) | ||

NA, not available; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TcB, transcutaneous bilirubin.

Lastly, applying the 40th centile as cut‐off for high risk of hyperbilirubinaemia, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and NPV were the same as those for the medium‐risk and low‐risk thresholds (table 3). The sensitivity and NPV for the 75th centile track were 86.7% and 97.0%, whereas the specificity and PPV were 58.4% and 22.0%, respectively. If the 95th centile track was used for prediction, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were 45.0%, 92.7%, 45.1% and 92.6%, respectively.

Table 1 Statistical analysis for phototherapy with low‐risk threshold.

| TcB category | Phototherapy (low risk) | Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | Specificity, % (95% CI) | PPV, % | NPV, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||

| >40% | 1 | 996 | 100 | 0 | NA | NA |

| ⩽40% | 0 | 0 | (20.7 to 100) | (0 to 0.38) | ||

| >75% | 1 | 441 | 100 | 55.7 | 23.4 | 100 |

| ⩽75% | 0 | 555 | (20.7 to 100) | (52.6 to 58.8) | ||

| >95% | 1 | 96 | 100 | 90.4 | 58.5 | 100 |

| ⩽95% | 0 | 900 | (20.7 to 100) | (88.4 to 92.0) | ||

NA, not available; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; TcB, transcutaneous bilirubin.

Table 4 shows the likelihood ratios of different risks of phototherapy (high to low) for TcBs in different risk zones of Bhutani's nomogram.

Table 4 Likelihood ratios of the different risk thresholds of phototherapy.

| Hour‐specific TcB centile zone | Likelihood ratio of different risks of phototherapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High risk | Medium risk | Low risk | |

| >95th | 23.0 | 6.86 | 5.34 |

| 76th–95th | 0.69 | 1.11 | 0 |

| 40th–75th | 0.13 | 0 | 0 |

TcB, transcutaneous bilirubin.

Discussion

We have shown a significant correlation between TcB (JM‐103) and TSB measurements in our local Chinese newborns. The correlation coefficient (r = 0.83) is comparable with that reported in the study by Maisels et al,15 which is mainly of white or black races (r = 0.915). However, after calculation of the actual difference between TcB and TSB, the JM‐103 bilirubinometer overestimated TSB by a mean of 21.7 μmol/l in our Chinese newborns, which was significant (p<0.001). The magnitude of this overestimation was also larger than that in the study by Maisels et al. On the other hand, a recent study of TcB in newborns of predominantly white race showed an underestimation of TSB.19 This may due to the difference in race and skin pigmentation. Further studies on the influence of skin pigmentation, especially in the Chinese, are required. Although the difference between TcB and TSB in this study was larger than in the previous one, the tendency to overestimate TSB provides a safety margin for confirmation and further monitoring.

Combining the use of TcB and Bhutani's nomogram gave more satisfactory results. All cases of severe hyperbilirubinaemia were identified by using either the 40th or 75th centile as cut‐off level, applying the low‐risk or medium‐risk threshold for phototherapy. The sensitivity and NPV for the 75th centile were both 100%, but the specificity was only about 56% and PPV 23%. However, if the 95th centile was chosen, the specificity could be improved to 90.7% and PPV to 52.1%, but the sensitivity decreased to 75.0% and NPV to 96.4%.

Using TcB and Bhutani's nomogram together for prediction was also relatively safe for high‐risk cases. Applying the 75th centile gave a lower sensitivity of 86.7% and an NPV of 97.0% as compared with low‐risk or medium‐risk cases. But their specificities and PPVs were similar to those in low‐risk and medium‐risk newborns.

Compared with another study in a Hispanic population in 2004, the use of the 75th centile had a sensitivity of 71% and a specificity of 85%.20 Our study showed a much better sensitivity—which means prediction of all cases—when the 75th centile was used as a cut‐off for Chinese newborns.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the TSB was measured by the photometric method in our local laboratory rather than the gold standard high‐performance liquid chromatography. It has already been shown that the results of different methods of bilirubin measurement vary greatly.21 Regular quality control of TSB measurements is carried out in our laboratory.17 Moreover, non‐chemical photometric devices have been shown to correlate well with TSB measured by the diazo methods.19 Using the photometric method for the sole comparison with TcB should also eliminate the systematic error resulting from different reference standards.

Another limitation in our study was that most of the paired TcB and TSB levels were taken within the first 3 days of life, as most of the normal newborns in our hospital were discharged by day 3. Higher physiological TSB levels would be expected in the later part of the first week of life, especially in our Chinese newborns.3 None of our paired‐sample TSB was >300 μmol/l. As illustrated in fig 3, the difference between the two measurements was larger for TSB (>200 μmol/l). Therefore, more caution should be taken and more studies are needed to investigate the accuracy of measurement of bilirubin in babies with more severe jaundice.

TcB levels can easily be measured using the JM‐103 bilirubinometer. Maisels et al15 showed that the average (SD) time needed to obtain a measurement was only 5.7 (2.3) s. Sequential TcB monitoring over time should reduce the effect of random error from a single measurement and provide an indication of the rate of bilirubin increase. Plotting the TcB on a nomogram will soon show whether the jaundice is following an expected physiological course or is rising and crossing centiles, necessitating closer follow‐up. TcB is not identical to serum bilirubin, and although TcB provides an estimate of the TSB level, it should not be considered in isolation; critical decisions should not be made on the basis of a single measurement. Confirmation with TSB, along with the consideration of risk factors, is important for decision making.5

Recently, increasing numbers of mothers from Mainland China are delivering in Hong Kong. Most of them have had no antenatal assessment in obstetric units, and they request early discharge within 24–48 h after delivery. Early discharge of newborns may result in jaundice not being detected, especially in Chinese newborns who have delayed onset of jaundice and higher peak levels. The measurement of TcB and TSB within 24 h of discharge and a systematic follow‐up programme according to Bhutani's nomogram would help identify these high‐risk infants for prevention or detection of severe hyperbilirubinaemia. The use of this non‐invasive bilirubinometer also would allow more frequent monitoring of increasing bilirubin levels in, especially infants with higher risk of developing jaundice or in clinics without immediate assessment of blood TSB levels.

What is already known about the topic

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommended measuring the total serum bilirubin (TSB) or transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) levels and plotting the results on a nomogram for assessing the risk of developing subsequent hyperbilirubinaemia.

TcB measured with a new transcutaneous bilirubinometer (JM‐103) significantly correlated with TSB in a newborn population of mainly white and black races.

What this paper adds

Transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) values measured by the JM‐103 were significantly different with TSB values in Chinese newborns.

Combining the use of TcB and the 75th centile in Bhutani's nomogram as cut‐off level could help identify all cases of severe hyperbilirubinaemia.

Conclusion

The availability of an accurate point‐of‐care bilirubin analyser would facilitate system‐based bilirubin screening and avoid unnecessary blood tests.22 Although there is apparently a significant difference between TcB and TSB derived by bilirubinometer JM‐103, combining the use of Bhutan's nomogram and this bilirubinometer has been shown to be useful in the evaluation of neonatal jaundice. Applying the 75th centile as a cut‐off level can help identify all cases of severe hyperbilirubinaemia. It is important to note that TcB is only a screening tool; confirmation with TSB should always be considered, especially for newborns with higher risk.10

Abbreviations

NPV - negative predictive value

PPV - positive predictive value

TcB - transcutaneous bilirubin

TSB - total serum bilirubin

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Maisels M J, Gifford K. Neonatal jaundice in full‐term infants. Role of breast‐feeding and other causes. Am J Dis Child 1983137561–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fok T F, Lau S P, Hui C W. Neonatal jaundice—its prevalence in Chinese infants and associating factors. Aust Paediatr J 198622215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung C Y. Neonatal jaundice in Chinese. Hong Kong J Pediatr 19929233–250. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamanouchi I, Yamauchi Y, Igarashi I. Transcutaneous bilirubinometry: preliminary studies of noninvasive transcutaneous bilirubin meter in the Okayama National Hospital. Pediatrics 198065195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai J, Parry D M, Krahn J. Transcutaneous bilirubinometry: its role in the assessment of neonatal jaundice. Clin Chem 1997301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maisels M J, Kring E. Trancutaneous bilirubinometry decreases the need for serum bilirubin measurements and saves money. Pediatrics 199799599–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briscoe L, Clark S, Yoxall C. Can transcutaneous bilirubinometry reduce the need for blood tests in jaundice full term babies? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 200286F190–F192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson J R, Okorodudu A O, Mohammad A A.et al Association of transcutaneous bilirubin testing in hospital with decreased readmission rate for hyperbilirubinemia. Clin Chem 200551540–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevenson D K, Wong R J, Vreman H J. Reduction in hospital readmission rates for hyperbilirubinemia is associated with use of transcutaneous bilirubin measurements. Clin Chem 200551481–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Hyperibilirubinemia Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 2004114297–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhutani V K, Johnson L, Sivieri E M. Predictive ability of predischarge hour‐specific serum bilirubin for subsequent significant hyperbilirubinemia in healthy term and new‐term newborns. Pediatrics 19991036–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ip S, Chung M, Kulig J.et al An evidence‐based review of important issues concerning neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Pediatrics 2004114e130–e152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson A, Kazmierczak S, Vos P.et al Improved transcutaneous bilirubinometry: comparison of SpectRx Bilicheck and Minolta jaundice meter JM‐102 for estimating total serum in a normal newborn population. J Perinatol 20022212–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yasuda S, Itoh S, Isobe K.et al New transcutaneous jaundice device with two optical paths. J Perinat Med 20033181–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maisels M J, Ostrea E M, Jr, Touch S.et al Evaluation of a new transcutaneous bilirubinometer. Pediatrics 20041131628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamauchi Y, Yamanouchi I. Transcutaneous bilirubinometry: bilirubin kinetics of the skin and serum during and after phototherapy. Biol Neonate 198956263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.RCPA‐AACB Chemical Pathology Quality Assurance Programs Information Handbook Profession based quality assurance programs for you & your laboratory. Version 2, revised October 2001. Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, South Australia 5042, Australia

- 17.Doumas B T, Kwok‐Cheung P P, Perry B W.et al Candidate reference method for determination of total bilirubin in serum: development and validation. Clin Chem 1985311779–1789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bland J M, Altman D G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986307–310. [PubMed]

- 19.Grohmann K, Roser M, Rolinski B.et al Bilirubin measurement for neonates: comparison of 9 frequently used methods. Pediatrics 20061171174–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engle W D, Jackson G L, Sendelbach D M.et al Evaluation of transcutaneous bilirubin (TcB) in term and near‐term neonates following hospital discharge [abstract]. Pedriatr Res 200455460A [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vreman H J, Verter J, Oh W.et al Interlaboratory variability of bilirubin measurements. Clin Chem 199642869–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhutani V K, Johnson L H, Gourley G.et al Measuring bilirubin through the skin? Pediatrics 2003111919–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]