Abstract

In different rodent models of hypertension, vascular voltage-gated L-type calcium channel (CaL) current and vascular tone is increased because of increased expression of the noncardiac form of the CaL (Cav1.2). The objective of this study was to develop a small interfering RNA (siRNA) expression system against the noncardiac form of Cav1.2 to reduce its expression in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). siRNAs expressing plasmids and appropriate controls were constructed and first screened in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells cotransfected with a rat Cav1.2 expression vector. The most effective gene silencing was achieved with a modified mir-30a-based short hairpin RNA (shRNAmir) driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter. In A7r5 cells, a vascular smooth muscle cell line, two copies of shRNAmir driven by a chimeric VSMC-specific enhancer/promoter reduced endogenous Cav1.2 expression by 61% and decreased the CaL current carried by barium by 47%. Moreover, the chimeric vascular smooth muscle-specific enhancer/promoter displayed almost no activity in non-VSMCs (PC-12 and HEK 293). Because the proposed siRNA was designed to only target the noncardiac form of Cav1.2, it did not affect the CaL expression and function in cultured cardiomyocytes, even when driven by a stronger cytomegalovirus promoter. In conclusion, vascular Cav1.2 expression and function were effectively reduced by VSMC-specific delivery of the noncardiac form of Cav1.2 siRNA without similarly affecting cardiac CaL expression and function. When coupled with a viral vector, this molecular intervention in vivo may provide a novel long-term vascular-specific gene therapy for hypertension.

One hallmark finding in chronic hypertension is an anomalous constriction of small arteries and arterioles that is mediated by Ca2+ influx through CaL (Cav1.2). Cav1.2 expression is increased in the renal, mesenteric, and skeletal muscle circulations of different rodent models of hypertension, and the increased expression corresponds to a higher density of CaL current and the development of anomalous vascular tone (Ohya et al., 1993; Lozinskaya and Cox, 1997; Pratt et al., 2002; Pesic et al., 2004). In smooth muscle-specific Cav1.2 knockout mice, depolarization-induced contraction and myogenic tone were abolished, and the mean blood pressure was reduced by ∼30 mm Hg (Moosmang et al., 2003). These studies demonstrate collectively a strong, positive correlation between blood pressure and the number of CaL in the arterial circulation in vivo. Thus, high blood pressure may be amenable to control by therapeutic interventions that down-regulate Cav1.2 expression in the vasculature.

Cav1.2 is expressed in many tissues including heart, brain, lung, uterus, the gastrointestinal system, and VSMCs (Koch et al., 1990). Several alternatively spliced isoforms have been identified. It is notable that alternative splicing of exon 1 results in two different N termini of Cav1.2 (isoforms A and B) that are conserved in many species. Isoform A (cardiac form) is specifically expressed in the heart, whereas isoform B (noncardiac form) is ubiquitously expressed in many cell types, including VSMCs (Dai et al., 2002; Pang et al., 2003; Saada et al., 2003, 2005; Tang et al., 2007). Cav1.2 isoform B is the main isoform up-regulated in the arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) compared with their normotensive controls, but the total expression level of Cav1.2 does not change in SHR hearts (Wang et al., 2006a), presumably because the expression level of isoform B (both mRNA and protein) in the heart is far less than isoform A (Dai et al., 2002; Pang et al., 2003; Saada et al., 2003, 2005; Tang et al., 2007). Thus, our goal in this study is to design an siRNA expression vector that can preferentially knock down the expression of the noncardiac form of Cav1.2 in VSMCs without affecting the cardiac Cav1.2 expression in the heart, where CaL activity is crucial for excitation-contraction coupling. Using this molecular intervention to reduce the abnormal expression of CaL in VSMCs rather than attempting to block Ca2+ influx may represent a new way to treat hypertension because it may offer even higher vascular selectivity and fewer side effects than traditional calcium channel blockers.

Materials and Methods

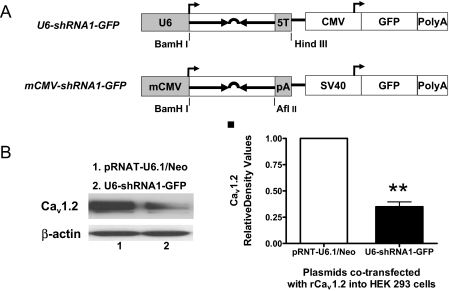

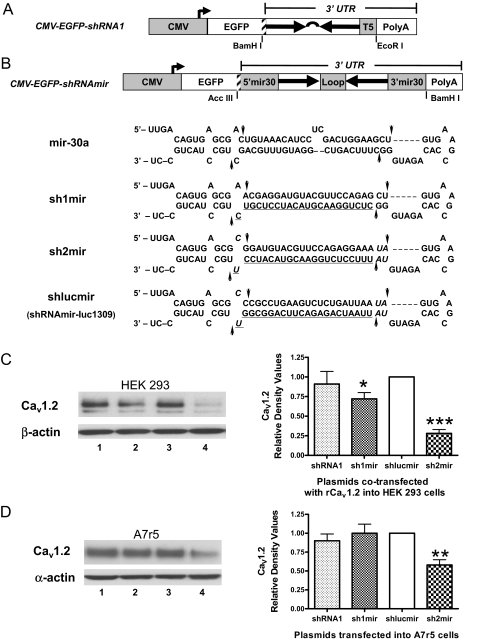

Plasmids. The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression vectors U6-shRNA1-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and modified cytomegalovirus (mCMV) promoter-shRNA1-GFP (Fig. 1A) were prepared using the commercial siRNA expression vectors pRNAT-U6.1/Neo and pRNAT-CMV3.1/Neo (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ), which contain either a human U6 promoter- or a mCMV promoter-driven siRNA expression cassette and an RNA polymerase (pol) II promoter-driven marker gene-GFP. The oligonucleotide shRNA1 has the following sequence: 5′-CTC TGG AAC GTA CAT CCT CGT TTC AAG AGA ACG AGG ATG TAC GTT CCA GAG-3′, where the antisense strand (the proposed siRNA strand) is underlined, and the stem loop sequence is in italics. The CMV-EGFP-shRNA1 (Fig. 2A) was prepared by inserting a translational stop codon and shRNA1 into pEGFP-C1's (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) multiple cloning sites (Ling and Li, 2004; Yuan et al., 2006). The microRNA (miRNA) mir-30a-based shRNA constructs (CMV-EGFP-shRNAmir, Fig. 2B) were prepared by incorporating the siRNA encoding sequences into the mir-30a backbone and then placing them at the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of pEGFP-C1. All the shRNA inserts were chemically synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA).

Fig. 1.

Expression of shRNA1 driven by a U6 or mCMV promoter. A, schematic diagrams of U6-shRNA1-GFP and mCMV-shRNA1-GFP. The annealed double-stranded oligonucleotide shRNA1 was subcloned into BamHI- and HindIII-digested pRNAT-U6.1/Neo or BamHI- and AflII-digested pRNAT-CMV3.1/Neo vector, respectively. The five thymidine stretches (5T) serve as a pol III termination signal, whereas the polyadenylation sequence (synthetic minimal polyA and polyA) terminates pol II transcription. B, Western blot and densitometry analysis of the silencing effects of U6-shRNA1-GFP in rat Cav1.2 isoform B expression vector (rCav1.2) cotransfected HEK 293 cells compared with the control vector pRNAT-U6.1/Neo (n = 3; **, p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of silencing effects of several CMV promoter-driven shRNA constructs directed against Cav1.2 isoform B. A, schematic diagram of CMV-EGFP-shRNA1. The annealed double-stranded oligonucleotide shRNA1 with a 5T termination signal was cloned into pEGFP-C1 by BamH I and EcoRI. A translational stop codon (shadowed bar at the right end of EGFP) was inserted in front of shRNA1 to enable the shRNA1 located in the 3′-UTR. B, schematic diagrams of CMV-EGFP-shRNAmir constructs. A translational stop codon (the shadowed bar at the right end of EGFP) and the shRNAmir were cloned into pEGFP-C1 by Acc III and BamH I. The structure and sequence of the original mir-30a is compared with sh1mir, sh2mir, and shlucmir. The modified nucleotides in the mir-30a context are shown in italics. The antisense target sequences (the proposed siRNA strands) are underlined. The potential Drosha (left sides) and Dicer (right sides) processing sites are marked with arrows. C and D, representative Western blot demonstrating that CMV-EGFP-sh2mir can significantly knock down both exogenous and endogenous Cav1.2 expression in HEK 293 (C) and A7r5 (D) cells. Lane 1, cells transfected with CMV-EGFP-shRNA1; lane 2, CMV-EGFP-sh1mir; lane 3, CMV-EGFP-shlucmir; lane 4, CMV-EGFP-sh2mir. CMV-EGFP-shlucmir served as a negative control because there is no luciferase expression in mammalian cells (n = 3–5; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

The Cav1.2 siRNA-targeting sequences were carefully selected among the 100% homologous region of mouse and rat Cav1.2 exon 1b sequences (GenBank accession no. L01776, nucleotides 1109–1215; M67516, nucleotides 697–803), which would only target the noncardiac isoform. Similarity search of candidate siRNA against the mRNA sequences of both mouse and rat was conducted using the BLAST program (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD). The truncated mouse SM22α promoter was amplified by polymerase chain reaction from plasmid pBluescript-SM22α (kindly provided by Dr. Joseph Miano, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY) with forward primer, 5′-AGCT ATT AAT GGA TC CTC GAG TAG TCA AGA CTA GTT CCC ACC AA-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-TCAG GCT AGC GAA GGA GAG TAG CTT CGG TGT-3′ (underlined nucleotides represent restriction sites used for subcloning). The rabbit myosin heavy-chain enhancer (GenBank accession no. X79928; nucleotides 973-1084) was chemically synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. and inserted in front of the SM22α promoter with AseI and XhoI. The shRNAmir constructs with the chimeric smooth muscle-specific enhancer/promoter (EnSM22α) were prepared by replacing the CMV promoter of CMV-EGFP-shRNAmir with AseI- and NheI-digested EnSM22α. The correct inserts of each plasmid were verified by sequencing.

Cell Culture and Transfection. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and A7r5 cells (an embryonic rat aortic VSMC line) (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). HL-1 cells (a mouse atrial cell line, kindly provided by Dr. Claycomb, Louisiana State University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA) were cultured in Claycomb medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen). PC-12 cells (a rat neuroendocrine cell line; American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5g/l glucose, 5% FBS, and 10% horse serum (Invitrogen). siRNA expression constructs were electroporated into A7r5, HL-1, and PC-12 cells with the Cell Line Nucleofector Kit V by Amaxa Nucleofector II (Amaxa Biosystems, Gaithersburg, MD) and cotransfected (1:1) with a rat Cav1.2 isoform B expression vector (kindly provided by Dr. Sandra Guggino, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) into HEK 293 cells using FuGENE 6 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). GFP expression was checked 48 to 72 h post transfection. Cell images were captured with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M digital fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Transfection efficiency was estimated from the percentage of GFP-expressing green cells using fluorescence microscopy and verified by flow cytometry (Cell Lab Quanta; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). Western blots were performed only when ≥70% of cells were transfected.

Patch Clamp of CaL Current. Three days post-transfection, HL-1 or A7r5 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in control Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) of the following composition: 145 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 5.5 mM dextrose. The cells were placed in a glass bottom dish and allowed to attach to the bottom at room temperature. The dish was placed on the stage of an inverted microscope and perfused with control HBSS. To measure CaL current, cells were externally perfused with 20 mM barium HBSS (both sodium- and potassium-free with 110 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine substitution) and internally with 150 mM cesium, 120 mM aspartate, 30 mM chlorine, 1 mM calcium, 5 mM magnesium, 11 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM GTP, 5 mM creatine phosphate, and 5 mM pyruvate. Osmolarity of all solutions was 290 to 310 mOsm, and pH of external and internal solutions was adjusted to 7.4 and 7.2, respectively. All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C).

Electrophysiological measurements were made using conventional techniques and methods described previously (Harrell and Stimers, 2002). Data obtained in response to voltage pulses were low-pass filtered by either analog or digital filters at 1 kHz and sampled at 2 kHz. Patch pipettes were made from borosilicate glass (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) pulled on a Brown-Flaming P77 puller (Sutter Instrument Company, Novato, CA) and fire polished to have a final resistance of 3 to 5 MΩ (inside tip diameter of 1–3 μm). Capacitance and series resistance compensation were used to improve the quality of the voltage clamp and reduce associated artifacts. P/4 protocols were used to cancel leak and capacitance currents when pulse protocols were applied.

Western Blots. Cultured cells were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Ipegal (octylphenyl-polyethylene glycol), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 5 μg/ml leupeptin) (all from Sigma-Aldrich) 72 h post-transfection, and the supernatant was collected after a 15-min centrifugation at 10,000g. Western blots were run using Tris-acetate gradient gels (Invitrogen), transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (G-Biosciences, Maryland Heights, MO), blocked, and probed with primary antibody for Cav1.2 (Alamone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), α/β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and IP3R1 (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY). Films were scanned, and the images were quantified with an Alpha Innotech (San Leandro, CA) 8900 imager using AlphaEase FC software, version 3.2.3.

Statistical Analysis. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences were considered significant when the p value was <0.05.

Results

Comparison of Different pol II Promoter-Driven siRNA Expression Systems. shRNA driven by pol III promoters, such as the U6 and H1 promoter, has been used widely for continuous expression of siRNA. Thus, we first designed several classic U6 promoter-driven shRNA constructs against mouse and rat Cav1.2 isoform B and tested their efficiency in HEK 293 cells cotransfected with a plasmid that expresses rat Cav1.2 isoform B. We found that U6-shRNA1-GFP had the highest efficiency (Fig. 1, A, top diagram, and B).

However, pol III promoters cannot drive tissue- or cell-specific expression. To test the feasibility of specifically targeting VSMCs, we transferred shRNA1 into a pol II promoter-driven siRNA expression vector (mCMV-shRNA1-GFP, Fig. 1A, bottom diagram). The CMV promoter of this vector was modified by removing the 5′-UTR, and the hairpin was placed immediately behind the CMV transcription start site followed by a synthetic minimal polyA (Xia et al., 2002). It is unfortunate that the silencing effect of this construct was poor (less than 30%, data not shown). In addition to the poor silencing effect, because 5′-UTRs and even the first exon/intron are often very important for promoter activity and/or tissue specificity, the modified CMV promoter may not be interchangeable with many tissue- or cell-specific pol II promoters. Thus, we explored other pol II promoter-driven siRNA expression systems.

CMV-EGFP-shRNA1 (Fig. 2A) was prepared by directly placing the shRNA1 in the 3′-UTR of EGFP cDNA (Ling and Li, 2004; Yuan et al., 2006). CMV-EGFP-sh1mir (Fig. 2B) was constructed by replacing the mir-30a stem sequence with shRNA1 directly (Boden et al., 2004), and CMV-EGFP-sh2mir was constructed by incorporating a newly designed miRNA-based shRNA2 into the mir-30a backbone, with modifications of a few nucleotides. The sh2mir structure was very similar to the reported shRNAmir-luc1309 (shlucmir, Fig. 2B), which significantly silenced firefly luciferase with either pol II or pol III promoter (Silva et al., 2005). To make direct comparisons of the silencing effects of different expression cassettes, the shRNAmirs were also cloned into pEGFP-C1 and placed in the 3′-UTR of EGFP cDNA (Fig. 2B). Cotransfection of CMV-EGFP-shlucmir with plasmids expressing firefly luciferase demonstrated that the miRNA-based shRNA expression cassette can be adapted to the pEGFP-C1–3′-UTR and significantly reduce luciferase activity more than 70% (data not shown). In Fig. 2, C and D, the effects of different constructs to suppress CaV1.2 expression were compared with the negative control, CMV-EGFP-shlucmir, in lane 3. The silencing effect of CMV-EGFP-sh2mir (lane 4) was much stronger than CMV-EGFP-shRNA1 (lane 1) and CMV-EGFP-sh1mir (lane 2) in both HEK 293 cells and A7r5 cells.

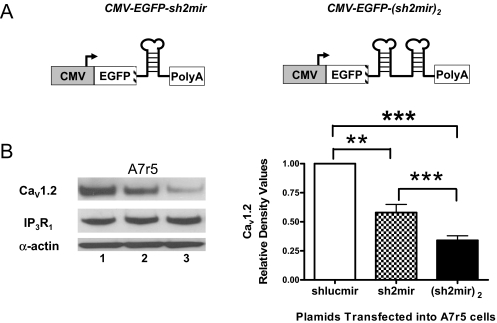

Because several natural miRNAs exist in clusters (Lagos-Quintana et al., 2001; Tanzer and Stadler, 2004), the polycistronic transcripts might be able to enhance the efficiency of target gene repression (Liu et al., 2008). Plasmid CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 was constructed with two copies of sh2mir (Fig. 3A). We found that CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 had more significant effects than CMV-EGFP-sh2mir in silencing endogenous Cav1.2 in transfected A7r5 cells (0.34 ± 0.04 versus 0.58 ± 0.07, p < 0.001; Fig. 3B). The silencing effects were gene-specific insofar as they did not affect the expression levels of IP3R1 and α-actin.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the silencing effects of single- and double-copy sh2mir constructs driven by the CMV promoter. A, schematic diagrams for CMV-EGFP-sh2mir and CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2. B, both CMV-EGFP-sh2mir (lane 2) and CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 (lane 3) significantly knocked down the endogenous Cav1.2 expression in transfected A7r5 cells. The construct with two copies of sh2mir (lane 3) was more effective than the single-copy construct (lane 2). CMV-EGFP-shlucmir (lane 1) served as a negative control. Expression of another ion channel (IP3R1) was estimated by stripping and reprobing the same blot with IP3R1 antibody (n = 3; NS, no significant difference; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

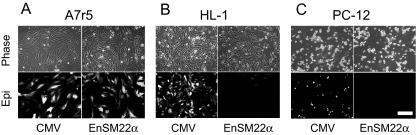

Smooth Muscle-Specific Knockdown of Cav1.2. Another critical step in developing shRNA against Cav1.2 as a potential antihypertensive therapy is to selectively target the vasculature using a smooth muscle-specific promoter. We chose the SM22α promoter because it is a widely used and well characterized vascular smooth muscle-specific promoter (Solway et al., 1995; Moessler et al., 1996; Hoggatt et al., 2002). The truncated SM22α promoter (∼500 bp) has been shown to have similar promoter activity as the full-length one and only drive reporter gene expression in vascular smooth muscle but not in the visceral smooth muscle or vein (Moessler et al., 1996; Hoggatt et al., 2002) Because the SM22α promoter is a relatively weak promoter, a smooth muscle-specific enhancer from rabbit myosin heavy chain was added in front of it to enhance potency (Ribault et al., 2001). This EnSM22α has been reported to enhance the SM22α promoter potency and smooth muscle specificity both in vitro and in vivo (Ribault et al., 2001). We compared the specificity and potency of CMV and EnSM22α promoters in driving GFP expression in VSMCs, A7r5 cells and non-VSMCs, and HL-1 and PC-12 cells. The EnSM22α promoter showed comparable activity as the CMV promoter (one of the strongest pol II promoters) in A7r5 cells (Fig. 4A) but showed very limited activity in non-VSMCs, HL-1 and PC-12 cells (Fig. 4, B and C).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of CMV and EnSM22α promoter potencies in driving the GFP expression by fluorescence microscopy. CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven constructs were transfected into A7r5 (A), HL-1(B), and PC-12 (C) cells. Top (Phase), phase contrast images of the same view fields shown below demonstrating GFP epi-fluorescence (Epi). Images were taken at 100× magnification. Scale bar, 20 μm.

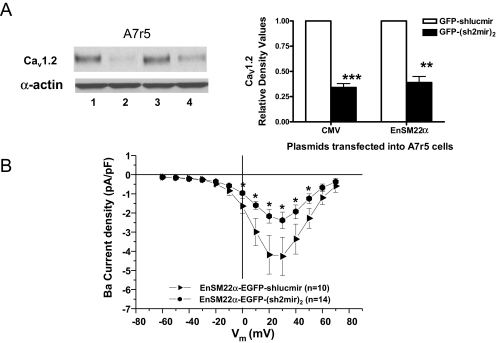

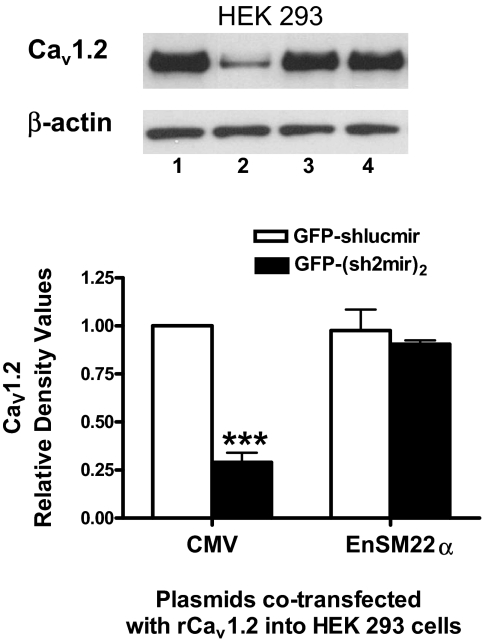

Because GFP and siRNA expression were both driven by the same promoter, we could easily track and identify siRNA-expressing green cells under a fluorescent microscope and patch them. EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 reduced Cav1.2 expression in transfected A7r5 cells by 61% as estimated by Western blots (Fig. 5A) and also decreased CaL current carried by barium by 47% at +20 mV in patch-clamped A7r5 cells (-2.17 ± 0.36 pA/pF versus -4.18 ± 1.01 pA/pF control EnSM22α-EGFP-shLucmir, p < 0.05; Fig. 5B). However, EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 was not effective in cotransfected HEK 293 cells because HEK 293 cells are not VSMCs. In contrast, the positive control CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 was effective (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the potency of CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven shRNAmir constructs in A7r5 cells. A, both CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven (sh2mir)2 constructs significantly reduced Cav1.2 expression in A7r5 cells. Lane 1, CMV-EGFP-shlucmir; lane 2, CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2; lane 3, EnSM22α-EGFP-shlucmir; lane 4, EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2. The corresponding shlucmir constructs served as negative controls (n = 4, **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). B, current-voltage relationship shows that CaL currents were significantly suppressed in EnSM22α-GFP-(sh2mir)2 transfected cells compared with the control construct EnSM22α-GFP-shlucmir (*, p < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven shRNAmir constructs potencies in HEK 293 cells. CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 (lane 2) but not EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 (lane 4), significantly knocked down exogenous Cav1.2 isoform B expression in cotransfected HEK 293 cells. The shlucmir constructs (lane 1, CMV-EGFP-shlucmir; lane 3, EnSM22α-EGFP-shlucmir) served as negative controls (n = 3; ***, p < 0.001).

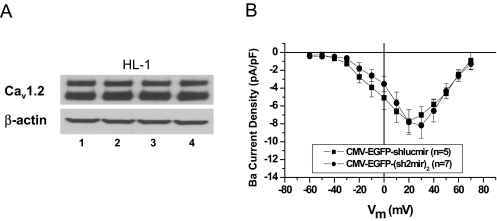

siRNA against Cav1.2 Isoform B Did Not Affect Cardiac L-Type Calcium Channel Expression and Function. Similar to human and rat hearts, Cav1.2 isoform A is the main isoform expressed in HL-1 cells (estimated by Western blot and real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, data not shown). To confirm the selective inhibition of noncardiac CaV1.2, we transfected CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven shlucmir and (sh2mir)2 constructs into the HL-1 cells (Fig. 7A) and found no decrease in overall expression of Cav1.2 protein. Because of the limited expression of GFP when driven by EnSM22α promoter (Fig. 4B), we were not able to visually identify the transfected cells to measure the Ca2+ current and confirm the EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 effect (Fig. 7A, lane 4). Instead, we compared the effect of CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 on the CaL current in HL-1 cells and found no significant decrease in the Ba2+ current compared with CMV-EGFP-shlucmir control (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of the potency of CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven shRNAmir constructs in HL-1 cells. A, Western blot showed that both CMV and EnSM22α promoter-driven (sh2mir)2 constructs failed to knock down the cardiac form of Cav1.2 expression. Lane 1, CMV-EGFP-shlucmir; lane 2, CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2; lane 3, EnSM22α-EGFP-shlucmir; lane 4, EnSM22α–EGFP-(sh2mir)2. shlucmir Constructs represent negative controls. B, current-voltage relationship shows that even the stronger CMV promoter-driven CMV-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 did not alter CaL current densities in HL-1 cells.

Discussion

Chronic hypertension is a deadly disease that predisposes nearly 72 million Americans and 1 billion individuals world-wide to ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, stroke, and end-stage renal damage. However, of those given antihypertensive drug treatment, only one third have their blood pressure normalized. Low compliance is believed to be the main reason for such a low control rate. Hypertension is a lifelong disease, but currently, all antihypertensive drugs have relatively short half-lives, and patients have to take medicine everyday or even multiple times daily. In addition, various side effects make it hard for patients to comply with their treatments (Chobanian et al., 2003; Burnier, 2006; Frishman, 2007). In this regard, a long-term gene therapy with fewer side effects may represent a significant advance in patient adherence and blood pressure control by avoiding the inconvenience associated with daily drug administration and minimizing the blood pressure fluctuations caused by short-acting drugs. The L-type calcium channel (Cav1.2) is a well known target for the control of hypertension because calcium channel blockers have been used widely as antihypertensive agents in daily clinical practice. The calcium channel blockers bind to distinct but closely related sites on the Cav1.2 channel to reduce the open-state probability of the Cav1.2 channel and thereby attenuate the voltage-gated Ca2+ influx that is required for vascular activation. One class of calcium channel blockers, namely, dihydropyridines (Triggle, 2003), are more effective in the vasculature than in heart or other tissues, in part because of the voltage dependence of their binding to the channels. Alternative splicing of Cav1.2 and different β subunit composition may also contribute to their VSMC preference. However, because of rapid onset and offset of the channel blockade, especially in the case of nifedipine, these drugs can increase sympathetic activity and cause reflex tachycardia. On the other hand, the slow-release, long-acting dihydropyridines (e.g., amlodipine) usually do not evoke such unwanted counter-regulatory responses (Triggle, 2003; Eisenberg et al., 2004). In this regard, viral vector-mediated Cav1.2 siRNA gene therapy, which selectively reduces the abnormal expression of vascular Cav1.2, may be potentially superior to blocking of Ca2+ influx by traditional dihydropyridines, provided that it exhibits a slow onset of action, long-term stability, and sustained vascular specificity.

siRNAs, which have higher catalytic efficiency and potency and are less susceptible to the influence of target mRNA secondary structure (Ogorelkova et al., 2006; Potera, 2007), have gradually replaced the traditional antisense and ribozyme methods to modulate target gene expression. As a treatment for hypertension, systemic delivery of synthetic siRNA against β1-adrenergic receptor showed promise in reducing blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy (Arnold et al., 2007). Nevertheless, therapeutic use of synthetic siRNAs is limited by their rapid degradation in target cells, resulting in relatively transient gene silencing, and by the difficulties in achieving sufficient transfer rates into multiple cell types of therapeutic interest, including VSMCs, especially for in vivo applications. Most importantly, systemic delivery of siRNAs may incur serious side effects by knocking down gene expression in nontarget tissues.

Pol III promoters direct high levels of gene expression; therefore, pol III promoter-driven shRNAs can produce highly efficacious, target-specific silencing. Coupled with viral vectors, a prolonged effect could be obtained. Wang et al. (2006b; Sun et al., 2008) showed that adeno-associated-virus delivery of U6 promoter-driven mineralocorticoid receptor shRNA prevented the progression of cold-induced hypertension for at least 3 weeks, which was the length of the study. He et al. (2008) reported that intravenous injection of adenovirus expressing shRNA against angiotensin-converting enzyme reduced blood pressure for more than 14 days and improved myocardial remodeling in SHRs. However, the pol III promoters have no tissue or cell specificity, and exceedingly high levels of siRNA expression increase the probability of off-target silencing and may elicit nonspecific cellular toxicity. Grimm et al. (2006) reported that the adeno-associated virus-mediated sustained high levels of siRNA expression (driven by U6 or H1 promoter) oversaturated the in vivo miRNA pathway and caused deadly liver damage, whereas expression of the siRNA from a liver-specific pol II promoter was safe and effective (Giering et al., 2008) because the tissue-specific pol II promoters are less active than ubiquitously expressed pol III promoters. To determine the best strategy to selectively deliver the therapeutic siRNA to the VSMCs, we screened several pol II promoter-driven siRNA expression systems and found that a modified mir-30a-based shRNA structure (sh2mir) mediated the most effective silencing (Fig. 2).

miRNAs are a recently recognized class of highly conserved, noncoding short RNA molecules (approximately 22 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. The maturation of miRNA is mediated by two RNase III endonucleases, Dicer and Drosha, and the mature miRNA functions as siRNA; the single-stranded guide RNA (siRNA strand) incorporates into the RNA-induced silencing complex and directs target gene silencing. Because miRNAs can down-regulate gene expression at the post-transcriptional level, and most miRNAs are transcribed by pol II promoters, mimicking the natural miRNA synthesis could be an efficient RNAi strategy (Silva et al., 2005; Xia et al., 2006). Our results clearly demonstrate that the modified mir-30a-based shRNA structure (sh2mir) had the strongest effect in silencing both exogenous and endogenous Cav1.2 (Fig. 2, C and D).

Our data also confirmed that the EnSM22α promoter was vascularly selective in vitro (Fig. 4). The EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2 significantly reduced Cav1.2 expression and function in vascular smooth muscle cells (A7r5 cells, Fig. 5) but not in other cell types tested (Figs. 6 and 7). Although Fig. 4B showed that there were a few GFP-expressing HL-1 cells when transfected with EnSM22α-EGFP-(sh2mir)2, the expression and function of the L-type calcium channels in HL-1 cells (cardiomyocytes) were not affected because (sh2mir)2 only targets the noncardiac form of Cav1.2 (Fig. 7). This is very important because most calcium channel blockers are contraindicated in patients with heart failure because of potential adverse inotropic effects. Even the second generation dihydropyridines have been linked with an increased risk of cardiovascular events (Eisenberg et al., 2004). Our study demonstrates the feasibility of selectively reducing vascular Cav1.2 expression and function without affecting cardiac Cav1.2 expression and function. This genetically based molecular intervention may potentially offer even higher vascular selectivity and fewer side effects than traditional dihydropyridines. However, we acknowledge that there is a long way to go from this in vitro study to a practical antihypertensive therapy. In vivo vascular selectivity, time course of gene transduction, efficiency of siRNA production, decrease in CaV1.2 expression and function in small resistance arteries, and corresponding changes in blood pressure all need to be carefully monitored and analyzed. A recent study showing in vivo application of shRNA expression cassette in zebrafish is encouraging (Su et al., 2008), and we are currently working on the in vivo application of our constructs.

In summary, we screened several siRNA expression systems for tissue-selective delivery and found that a modified mir-30a-based shRNA structure (sh2mir) mediated the most effective silencing, which was enhanced by incorporating two copies of sh2mir. Furthermore, we demonstrated the feasibility of vascularly selective down-regulation of endogenous Cav1.2 expression and function in VSMCs without affecting cardiac Cav1.2 expression and function. Coupled with viral vectors, long-term, vascular smooth muscle-specific reduction of the noncardiac form of Cav1.2 expression in vivo may potentially improve patient outcomes for hypertension treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael J. Borrelli and Laura J. Bernock for use of equipment and assistance in flow cytometry data analysis; Dr. Bosong Dai for cloning the U6 promoter-driven shRNA constructs; and Dr. Philip Palade for support, encouragement, and critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants HL63903, HL73097]; and by the American Heart Association [Grant SDG 0830060N].

S.W.R. and J.R.S. contributed equally to this work.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.108.148866.

ABBREVIATIONS: CaL, voltage-gated L-type calcium channel; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; SHR, spontaneously hypertensive rat; siRNA, small interfering RNA; GFP, green fluorescent protein; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; mCMV, modified cytomegalovirus promoter; pol, RNA polymerase; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; miRNA, microRNA; shRNAmir, mir-30a-based short hairpin RNA; UTR, untranslated region; EnSM22α, the chimeric smooth muscle-specific enhancer/promoter; HEK, human embryonic kidney; FBS, fetal bovine serum; HBSS, Hanks' balanced salt solution; IP3R1, inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate receptor type 1; rCav1.2, rat Cav1.2 isoform B expression vector.

References

- Arnold AS, Tang YL, Qian K, Shen L, Valencia V, Phillips MI, and Zhang YC (2007) Specific beta1-adrenergic receptor silencing with small interfering RNA lowers high blood pressure and improves cardiac function in myocardial ischemia. J Hypertens 25 197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden D, Pusch O, Silbermann R, Lee F, Tucker L, and Ramratnam B (2004) Enhanced gene silencing of HIV-1 specific siRNA using microRNA designed hairpins. Nucleic Acids Res 32 1154-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnier M (2006) Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens 19 1190-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, et al. (2003) Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 42 1206-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai B, Saada N, Echetebu C, Dettbarn C, and Palade P (2002) A new promoter for alpha1C subunit of human L-type cardiac calcium channel CaV1.2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 296 429-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg MJ, Brox A, and Bestawros AN (2004) Calcium channel blockers: an update. Am J Med 116 35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman WH (2007) Importance of medication adherence in cardiovascular disease and the value of once-daily treatment regimens. Cardiol Rev 15 257-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giering JC, Grimm D, Storm TA, and Kay MA (2008) Expression of shRNA from a tissue-specific pol II promoter is an effective and safe RNAi therapeutic. Mol Ther 16 1630-1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, Marion P, Salazar F, and Kay MA (2006) Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature 441 537-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell MD and Stimers JR (2002) Differential effects of linoleic Acid metabolites on cardiac sodium current. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303 347-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Bian Y, Gao F, Li M, Qiu L, Wu W, Zhou H, Liu G, and Xiao C (2009) RNA interference targeting ACE gene reduced blood pressure and improved myocardial remodeling in SHR. Clin Sci (Lond) 116 249-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggatt AM, Simon GM, and Herring BP (2002) Cell-specific regulatory modules control expression of genes in vascular and visceral smooth muscle tissues. Circ Res 91 1151-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch WJ, Ellinor PT, and Schwartz A (1990) cDNA cloning of a dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel from rat aorta: evidence for the existence of alternatively spliced forms. J Biol Chem 265 17786-17791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, and Tuschl T (2001) Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294 853-858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling X and Li F (2004) Silencing of antiapoptotic survivin gene by multiple approaches of RNA interference technology. Biotechniques 36 450-454, 456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YP, Haasnoot J, ter Brake O, Berkhout B, and Konstantinova P (2008) Inhibition of HIV-1 by multiple siRNAs expressed from a single microRNA polycistron. Nucleic Acids Res 36 2811-2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozinskaya IM and Cox RH (1997) Effects of age on Ca2+ currents in small mesenteric artery myocytes from Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 29 1329-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moessler H, Mericskay M, Li Z, Nagl S, Paulin D, and Small JV (1996) The SM 22 promoter directs tissue-specific expression in arterial but not in venous or visceral smooth muscle cells in transgenic mice. Development 122 2415-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Schulla V, Welling A, Feil R, Feil S, Wegener JW, Hofmann F, and Klugbauer N (2003) Dominant role of smooth muscle L-type calcium channel CaV1.2 for blood pressure regulation. EMBO J 22 6027-6034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogorelkova M, Zwaagstra J, Elahi SM, Dias C, Guilbaut C, Lo R, Collins C, Jaramillo M, Mullick A, O'Connor-McCourt M, et al. (2006) Adenovirus-delivered antisense RNA and shRNA exhibit different silencing efficiencies for the endogenous transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) type II receptor. Oligonucleotides 16 2-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya Y, Abe I, Fujii K, Takata Y, and Fujishima M (1993) Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in resistance arteries from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circ Res 73 1090-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang L, Koren G, Wang Z, and Nattel S (2003) Tissue-specific expression of two human CaV1.2 isoforms under the control of distinct 5′ flanking regulatory elements. FEBS Lett 546 349-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesic A, Madden JA, Pesic M, and Rusch NJ (2004) High blood pressure upregulates arterial L-type Ca2+ channels: is membrane depolarization the signal? Circ Res 94 e97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potera C (2007) Antisense–down, but not out. Nat Biotechnol 25 497-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt PF, Bonnet S, Ludwig LM, Bonnet P, and Rusch NJ (2002) Upregulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in mesenteric and skeletal arteries of SHR. Hypertension 40 214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribault S, Neuville P, Méchine-Neuville A, Augé F, Parlakian A, Gabbiani G, Paulin D, and Calenda V (2001) Chimeric smooth muscle-specific enhancer/promoters: valuable tools for adenovirus-mediated cardiovascular gene therapy. Circ Res 88 468-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada N, Dai B, Echetebu C, Sarna SK, and Palade P (2003) Smooth muscle uses another promoter to express primarily a form of human CaV1.2 L-type calcium channel different from the principal heart form. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 302 23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada NI, Carrillo ED, Dai B, Wang WZ, Dettbarn C, Sanchez J, and Palade P (2005) Expression of multiple CaV1.2 transcripts in rat tissues mediated by different promoters. Cell Calcium 37 301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva JM, Li MZ, Chang K, Ge W, Golding MC, Rickles RJ, Siolas D, Hu G, Paddison PJ, Schlabach MR, et al. (2005) Second-generation shRNA libraries covering the mouse and human genomes. Nat Genet 37 1281-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway J, Seltzer J, Samaha FF, Kim S, Alger LE, Niu Q, Morrisey EE, Ip HS, and Parmacek MS (1995) Structure and expression of a smooth muscle cell-specific gene, SM22 alpha. J Biol Chem 270 13460-13469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J, Zhu Z, Xiong F, and Wang Y (2008) Hybrid cytomegalovirus-U6 promoter-based plasmid vectors improve efficiency of RNA interference in zebrafish. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 10 511-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Bello-Roufai M, and Wang X (2008) RNAi inhibition of mineralocorticoid receptors prevents the development of cold-induced hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294 H1880-H1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZZ, Hong X, Wang J, and Soong TW (2007) Signature combinatorial splicing profiles of rat cardiac- and smooth-muscle CaV1.2 channels with distinct biophysical properties. Cell Calcium 41 417-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzer A and Stadler PF (2004) Molecular evolution of a microRNA cluster. J Mol Biol 339 327-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triggle DJ (2003) 1,4-Dihydropyridines as calcium channel ligands and privileged structures. Cell Mol Neurobiol 23 293-303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WZ, Saada N, Dai B, Pang L, and Palade P (2006a) Vascular-specific increase in exon 1B-encoded CaV1.2 channels in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Hypertens 19 823-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Skelley L, Cade R, and Sun Z (2006b) AAV delivery of mineralocorticoid receptor shRNA prevents progression of cold-induced hypertension and attenuates renal damage. Gene Ther 13 1097-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H, Mao Q, Paulson HL, and Davidson BL (2002) siRNA-mediated gene silencing in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol 20 1006-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia XG, Zhou H, and Xu Z (2006) Multiple shRNAs expressed by an inducible pol II promoter can knock down the expression of multiple target genes. Biotechniques 41 64-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Wang X, Zhang Y, Hu X, Deng X, Fei J, and Li N (2006) shRNA transcribed by RNA Pol II promoter induce RNA interference in mammalian cell. Mol Biol Rep 33 43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]