Abstract

Activation of ventral tegmental area (VTA)-dopaminergic (DA) neurons by ethanol has been implicated in the rewarding and reinforcing actions of ethanol. GABAergic transmission is thought to play an important role in regulating the activity of DA neurons. We have reported previously that ethanol enhances GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons in a brain slice preparation. Because intraterminal Ca2+ levels regulate neurotransmitter release, we investigated the roles of Ca2+-dependent mechanisms in ethanol-induced enhancement of GABA release. Acute ethanol enhanced miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current (mIPSC) frequency in the presence of the nonspecific voltage-gated Ca2+ channel inhibitor, cadmium chloride, even though basal mIPSC frequency was reduced by cadmium. Conversely, the inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate receptor inhibitor, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane, and the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase pump inhibitor, cyclopiazonic acid, eliminated the ethanol enhancement of mIPSC frequency. Recent studies suggest that the G protein-coupled receptor, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 2C, may modulate GABA release in the VTA. Thus, we also investigated the role of 5-HT2C receptors in ethanol enhancement of GABAergic transmission. Application of 5-HT and the 5-HT2C receptor agonist, Ro-60-0175 [(αS)-6-chloro-5-fluoro-α-methyl-1H-indole-1-ethanamine fumarate], alone enhanced mIPSC frequency of which the latter was abolished by the 5-HT2C receptor antagonist, SB200646 [N-(1-methyl-5-indoyl)-N-(3-pyridyl)urea hydrochloride], and substantially diminished by cyclopiazonic acid. Furthermore, SB200646 abolished the ethanol-induced increase in mIPSC frequency and had no effect on basal mIPSC frequency. These observations suggest that an increase in Ca2+ release from intracellular stores via 5-HT2C receptor activation is involved in the ethanol-induced enhancement of GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons.

The mesolimbic system bidirectionally encodes information related to positively and negatively reinforcing stimuli and, with conditioning, will adapt its output to such stimuli in a manner that encodes the error in reward prediction (Schultz et al., 1997). This capability is primarily processed via ventral tegmental area dopaminergic (VTA-DA) neurons, which originate in the midbrain nucleus A10 and project to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, and other corticolimbic structures (Albanese and Minciacchi, 1983; Oades and Halliday, 1987). Natural positive reinforcers activate VTA-DA neurons to release DA onto these structures, of which the medium spiny neurons of the NAc constitute the primary VTA-DA target. Most drugs of abuse pharmacologically activate VTA-DA neurons via a variety of mechanisms, culminating in aberrant release of DA onto these targets, and such pathological activation of the mesolimbic pathway is considered a primary step in the development and expression of drug dependence and addiction. Thus, acute exposure to ethanol increases dopamine levels in the NAc (Weiss et al., 1993). Furthermore, chronic exposure to ethanol has been reported to down-regulate VTA-DA release, and this state of dopaminergic hypofunction is thought to contribute to alcohol craving in dependent individuals (Rossetti et al., 1992). Although the mechanisms by which ethanol activates VTA-DA neurons to enhance DA output to the NAc are not entirely clear, evidence suggests a direct excitatory effect of ethanol on DA neurons in the VTA, either though inhibition of delayed-rectifying K+ channels or modulation of the h-current that underlies the basal pacemaker function of VTA neurons (Gessa et al., 1985; Brodie et al., 1999; Okamoto et al., 2006; Koyama et al., 2007).

Dopamine output from the VTA is regulated by both local GABAergic interneurons and GABA containing afferents from the NAc and ventral pallidum (Walaas and Fonnum, 1980; Grace and Onn, 1989; Johnson and North, 1992a). It is remarkable that our understanding of the effects of ethanol on GABAergic transmission in the mesolimbic DA system is not well defined and is currently in dispute. We have reported that pharmacologically relevant concentrations of ethanol enhance action potential dependent and independent GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons (Theile et al., 2008). On the other hand, Ye and colleagues (Xiao and Ye, 2008) recently demonstrated that ethanol decreases action potential-dependent GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons in a manner reversed by the μ-opioid receptor agonist, DAMGO. This discrepancy is particularly important because one of the few currently Food and Drug Administration-approved agents for alcohol craving, the μ-opiate antagonist, naltrexone, is thought to directly modulate VTA-GABAergic neuron activity and thus indirectly affect VTA-DA neuron firing (Franklin, 1995). Naltrexone has been demonstrated to block the ethanol-induced increase in NAc dopamine levels in animal models (Gonzales and Weiss, 1998). Thus, in this report, we have focused our work to uncover VTA-GABAergic regulatory mechanisms that may indirectly modulate ethanol effects on VTA-DA output.

One candidate regulatory pathway to the VTA consists of serotoninergic afferents from the midbrain raphe nuclei that innervate both DA and non-DA (GABAergic) neurons of the VTA (Hervé et al., 1987). Electrophysiological evidence indicates that serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] reuptake blockade inhibits VTA-DA firing, suggesting that a predominant action of 5-HT in the VTA is inhibitory and may involve activation of GABAergic neurons (Di Mascio et al., 1998). This contention is supported by the observations that: 1) 5-HT2C receptor (5-HT2CR) activation also inhibits VTA-DA neuron firing (Di Matteo et al., 2000), 2) 5-HT2CR mRNA is expressed in GABAergic neurons (Eberle-Wang et al., 1997), and 3) 5-HT2CRs are localized to both synaptic terminals and cell soma of VTA-GABA neurons, although these receptors have also been reported to occur on DA neurons as well (Bubar and Cunningham, 2007). Because 5-HT2CRs facilitate phospholipase C-mediated inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) accumulation and release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Conn et al., 1986), activation of this pathway on GABAergic soma or terminals could very well result in enhancement of GABA release. Activation or inhibition of 5-HT2CRs decreases or increases, respectively, ethanol self-administration by rats (Tomkins et al., 2002). In addition, enhancement of GABA release by ethanol onto cerebellar Purkinje neurons is dependent upon mobilization of Ca2+ from intracellular stores (Kelm et al., 2007). Lastly, no prior reports exist that directly assess whether 5-HT2CR activation regulates GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons. Therefore, another major impetus for this study is to identify the role of 5-HT2CRs and subsequent intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in ethanol facilitation of GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons.

Materials and Methods

Slice Preparation. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996) and were approved by the University of Texas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Slices used in this study were prepared from male Sprague-Dawley rats (postnatal days 21–33). Rats were anesthetized with halothane, decapitated, and the brain was rapidly removed and placed in an ice-cold choline-based, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing 110 mM choline Cl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM KCl, 25 mM dextrose, 7 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 11.6 mM sodium ascorbate, and 3.1 mM sodium pyruvate, bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 (all chemicals obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Horizontal midbrain slices (210 μm) were prepared using a vibrating slicer (VT1000S; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The slices were then maintained at 32°C before electrophysiological recordings for a minimum of 60 min in aCSF containing: 120 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3.3 mM KCl, 1.23 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM dextrose, 2.4 mM MgSO4, and 1.8 mM CaCl2, bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2.

Electrophysiological Recordings of VTA-DA Neurons. Individual slices were transferred to a recording chamber and perfused with oxygenated aCSF (30–32°C) at a flow rate of ∼2 ml/min. Recording aCSF was as described above except it contained 0.9 mM MgSO4 and 2 mM CaCl2. Cells were visualized using IR-DIC optics on an Olympus BX-50WI microscope (Leeds Instruments, Inc., Irving, TX). The VTA was identified as being medial to the medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract and rostral to the oculomotor nerve and the medial lemniscus. The majority of recordings were conducted in the lateral VTA, just medial to the medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were used for all experiments; putative DA neurons were identified by the presence of a large hyperpolarization-activated cationic current (>200 pA) that was measured immediately after break-in by application of a 1.5-s hyperpolarizing step from -60 to -110 mV (Johnson and North, 1992b). Recording electrodes were made from thin-walled borosilicate glass (TW 150F-4; WPI, Sarasota, FL; 1.5–2.5 MΩ) and contained 135 mM KCl, 12 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM Mg-ATP, and 0.3 mM Tris-GTP, pH 7.3, with KOH (all chemicals obtained from Sigma-Aldrich). Data were collected by an Axon Instruments model 200B amplifier filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 10 to 20 kHz with a Digidata interface using pClamp version 9.2 and 10.2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

GABAergic mIPSCs were pharmacologically isolated with kynurenic acid (1 mM) to inhibit α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid- and N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-mediated currents. Tetrodotoxin (TTX; 0.5 μM) and eticlopride (250 nM) were included to block Na+ currents and D2 receptor-mediated currents, respectively. Under these conditions, mIPSCs were inward at a holding potential of -60 mV, and in an initial set of experiments, their identity as GABAeric events was verified by testing for block with picrotoxin or bicuculline (data not shown). After break-in and a stable 10-min baseline (control) recording, drugs were bath-applied through the aCSF perfusion line, and a continuous 10- to 15-min recording epoch was used to detect changes in mIPSC frequency and amplitude. A 4-min drug wash-on preceded the start of data collection in each treatment condition, and a 12-min washout period followed drug application. The last half (6 min) of the washout period was used in our data analysis. The number of neurons used per each treatment condition is represented as n, with only one neuron used per slice. Eticlopride hydrochloride, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB), cyclopiazonic acid [(6aR,11aS,11bR)-rel-10-acetyl-2,6,6a,7, 11a,11b-hexahydro-7,7-dimethyl-9H-pyrrolo[1′,2′:2,3]isoindolo-[4,5,6-cd]indol-9-one], bicuculline methiodide, and Ro-60-0175 fumarate were obtained from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). Kynurenic acid, SB200646, nicardipine hydrochloride [1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl)methyl-2-[methyl(phenylmethyl)amino]-3,5-pyridinedicarboxylic acid ethyl ester hydrochloride], cadmium chloride, serotonin hydrochloride, and picrotoxin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. TTX was obtained from Alamone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel).

Data Analysis. For mIPSC recordings, quantal events (90–120 sweeps each condition, 5 s/sweep) were detected using the template mIPSC detection protocol contained within pClampfit (pClamp version 9.2; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Access resistance ranged from 6 to 20 MΩ and was monitored throughout the experiment. Experiments where access resistance changed (>20% at any time during the experiment) were excluded from this study. To minimize detecting small noise deflections as mIPSCs (false positives), events < 10 pA were discarded. Treatment and washout groups were normalized to the baseline (control) frequency or amplitude and represented as a percentage of the control. Averaged values for all data sets are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. and were compared statistically using paired Student's t test, unpaired Student's t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Bonferroni post hoc test where mentioned. The events encompassed in the histogram insets (Fig. 1) were compared using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (K-S) test. Significant differences were considered as p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

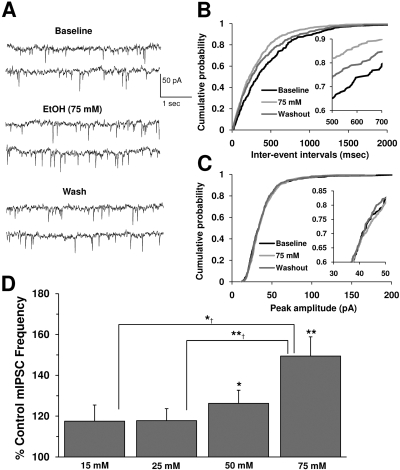

Fig. 1.

Ethanol potentiates mIPSC frequency but not amplitude. A, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 75 mM ethanol, and after a washout. B, cumulative probability histogram of mIPSC interevent intervals for epochs from a representative neuron. Inset, leftward shift in IEI distribution in the presence of ethanol is significant with respect to baseline (K-S test, p < 0.05). C, cumulative probability histogram of mIPSC event amplitudes from the same neuron shown in B. Inset, there is no shift in amplitude distribution in the presence of ethanol with respect to baseline (K-S test, p > 0.05). D, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency at 15, 25, 50, and 75 mM ethanol (n = 7 for 15 mM; n = 8 for 25 mM; n = 10 for 50 mM; n = 7 for 75 mM; *, p < 0.05 different from control; **, p < 0.01 different from control; *†, p < 0.05 different from 15 mM; **†, p < 0.01 different from 25 mM by one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc test).

Results

Ethanol Enhances mIPSC Frequency. Acute ethanol exposure enhanced GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons recorded in an in vitro slice preparation (Theile et al., 2008). For studies on the ethanol concentration dependence of GABA mIPSCs, a total of 32 VTA-DA neurons were exposed to 15, 25, 50, or 75 mM ethanol. All concentrations displayed an increase in mIPSC frequency (Fig. 1D), whereas no consistent change in mIPSC amplitude was apparent at any ethanol concentration (data not shown). The enhancement in frequency by both 50 and 75 mM were significant compared with control (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post hoc). There was an apparent increase in mIPSC frequency at 15 mM similar to that seen with 25 mM; however, the change was not significant. In response to 25 mM ethanol (legal intoxication is 17.4 mM), the frequency of mIPSCs increased by approximately 20%; mIPSC frequency increased by approximately 30 and 50% after exposure to 50 and 75 mM ethanol, respectively. To more thoroughly define the actions of ethanol on GABA mIPSC frequency and amplitude, we studied the cumulative event distributions for sample neurons at all concentrations tested (only 75 mM ethanol shown; Fig. 1, B and C). Application of ethanol induced a leftward shift in the cumulative distributions of mIPSC frequency (measured as interevent interval), which were statistically significant at all concentrations tested (K-S test, p < 0.05). The shifts in mIPSC frequency distributions were not skewed across different frequency ranges and thus were independent of mIPSC frequency itself. The insets for Fig. 1, B and C, present expanded sections of the event distributions and are centered around the 70th to 90th percentile level for more detailed comparison between treatments and groups. In all cases, shifts in mIPSC frequency are apparent and are evenly distributed across frequencies, whereas no changes in amplitude distributions are apparent. Finally, mIPSC frequency washout data reflects a notable shift back toward the control (pre-ethanol) population distribution.

To ensure that changes in postsynaptic or extrasynaptic GABA receptor function were not overlooked, we also measured the effects of ethanol on the decay time constant, τ, of the mIPSCs and the baseline holding current as a measure of tonic extrasynaptic GABA receptor function (data not shown). At the highest concentration tested (75 mM), ethanol did not affect decay kinetics, or τ, of the mIPSC. Under control conditions, mIPSC decay was 6.8 ± 0.6 ms, whereas in the presence of ethanol, it was 6.7 ± 0.5 ms (n = 7, p = 0.66). In addition, we found no significant effect of ethanol (75 mM) to enhance or induce tonic steady-state or “holding” currents recorded from VTA-DA neurons at -60 mV. For instance, a sham perfusion buffer exchange resulted in a positive shift in the average holding current of 24 ± 10 pA (n = 7), whereas ethanol treatment increased the average holding current by a similar degree [10 ± 10 pA (n = 7)].

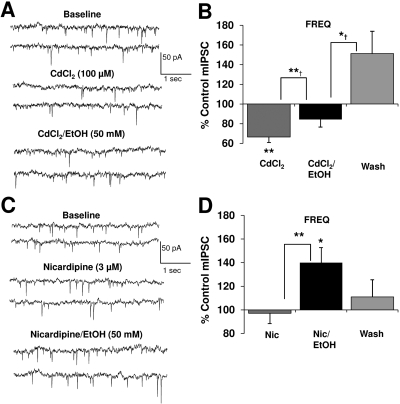

Extracellular Ca2+ Influx Is Not Required for the Ethanol-Induced Increase in GABA Release. To determine whether Ca2+ influx from extracellular sites may contribute to ethanol-induced enhancement of GABA release, we examined the effects of the nonselective voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCC) inhibitor, cadmium chloride (CdCl2; 100 μM) on ethanol potentiation of mIPSC frequency (Fig. 2, A and B). In the presence of CdCl2 alone, mIPSC frequency markedly decreased, indicating that influx of Ca2+ may significantly contribute to basal quantal GABA release even when action potentials were blocked with TTX. There was also a slight decrease in mIPSC amplitude (91.6 ± 2.2% of control; data not shown) in the presence of CdCl2 that remained in the presence of ethanol. Nevertheless, subsequent application of ethanol (50 mM) in the continued presence of CdCl2 significantly increased mIPSC frequency and therefore reversed the apparent CdCl2 inhibition by approximately 27%. After removal of both ethanol and CdCl2 from the perfusate, mIPSC frequency reversed to levels substantially greater than the pre-CdCl2 baseline, indicating that prolonged inhibition of extracellular Ca2+ availability may induce a complex rebound phenomenon that appears to markedly affect GABA release.

Fig. 2.

Blockade of VGCCs does not inhibit ethanol-induced potentiation of mIPSC frequency. A, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 100 μM CdCl2, and 50 mM ethanol with 100 μM CdCl2. B, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in A and a wash. Event frequency under control conditions was 1.7 ± 0.3 Hz (n = 10; **, p < 0.01 by a Student's t test different from control; *†, p < 0.05 by a Student's t test different from CdCl2/ethanol; **†, p < 0.01 by a paired Student's t test different from CdCl2 alone). C, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 3 μM nicardipine, and 50 mM ethanol with 3 μM nicardipine. D, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in C and a wash. Event frequency under control conditions was 2.0 ± 0.4 Hz (n = 6; *, p < 0.05 by a Student's t test different from control; **, p < 0.01 by a paired Student's t test different from nicardipine alone).

Of the different types of VGCCs, interactions with the L-type VGCC subtype and ethanol have been noted frequently (Mullikin-Kilpatrick and Treistman, 1995; Hendricson et al., 2003). GABA release onto the cholinergic neurons of Meynert's nucleus has been shown to be dependent upon L-type channels (Rhee et al., 1999). Therefore, we also assessed the effects of the L-type VGCC antagonist, nicardipine (3 μM), on ethanol potentiation of mIPSC frequency (Fig. 2, C and D). Application of this VGCC antagonist resulted in no change in either baseline mIPSC frequency (Fig. 2D) or amplitude (data not shown). As observed with CdCl2, in the continued presence of nicardipine, subsequent application of ethanol (50 mM) enhanced mIPSC frequency by 40 ± 13% and slightly increased mISPC amplitude by approximately 8% (control, 32.1 ± 2.2 pA, n = 6, p < 0.05). Taken together, these results suggest that extracellular Ca2+ influx, presumably via N- and/or P/Q-type VGCCs, contribute to basal GABA release, whereas L-types do not. Nevertheless, under no condition was ethanol enhancement of GABA release abolished by blocking extracellular Ca2+ entry.

Intracellular Ca2+ Stores Are Required for Ethanol-Induced Enhancement of GABA Release. Ca2+ release from presynaptic IP3- and ryanodine-sensitive internal stores is necessary for ethanol potentiation of GABA release onto Purkinje neurons in the cerebellum (Kelm et al., 2007). Thus, we investigated the role of IP3-sensitive intracellular Ca2+ in ethanol enhancement of mIPSC frequency through the use of two antagonists. First, we assessed the actions of the IP3 receptor (IP3R) antagonist, 2-APB. Second, we studied an inhibitor of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) pump, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), which depletes intracellular Ca2+ stores (Seidler et al., 1989). As also noted by Kelm et al. (2007) in their studies on Purkinje neurons, application of 2-APB alone (Fig. 3, A and B) had no significant effect on mIPSC frequency or amplitude. However, subsequent addition of ethanol in the presence of 2-APB did not result in any further change in frequency or amplitude compared with 2-APB alone. Likewise, application of the SERCA pump inhibitor, CPA (10 μM), at a concentration shown to be effective in depleting intracellular Ca2+ stores in DA neurons (Morikawa et al., 2000), completely blocked the enhancement of mIPSC frequency induced by subsequent addition of ethanol (50 mM) (Fig. 3, C and D). CPA alone did not change mIPSC frequency or amplitude compared with baseline. These results suggest that IP3R-mediated release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores is required for ethanol enhancement of GABA release onto DA neurons.

Fig. 3.

Blockade of intracellular Ca2+ release abolishes ethanol-induced potentiation of mIPSC frequency. A, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 28 μM 2-APB, and 50 mM ethanol with 28 μM 2-APB. B, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in A and a wash. Event frequency under control conditions was 2.1 ± 0.6 Hz (n = 6). C, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 10 μM CPA, and 50 mM ethanol with 10 μM CPA. D, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in C and a wash. Event frequency under control conditions was 1.3 ± 0.3 Hz (n = 9).

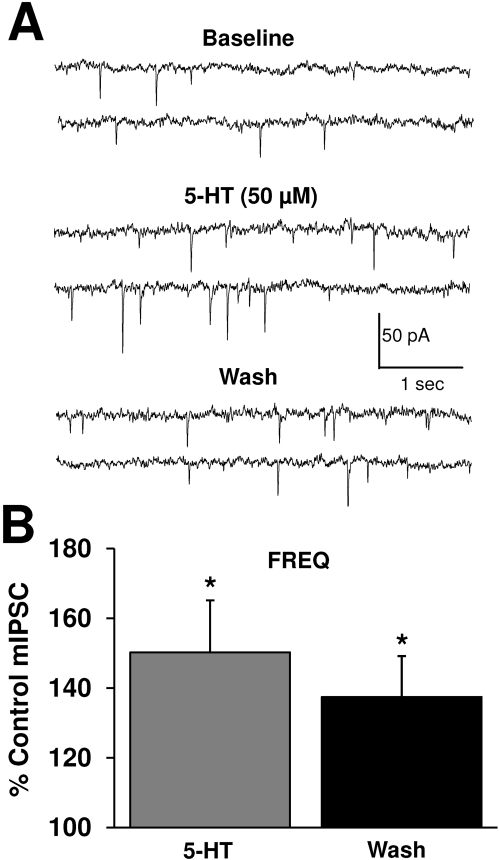

The 5-HT2CR Agonist, Ro-60-0175, and 5-HT Increase GABA Release. Recent studies have linked 5-HT2CR activation with modulation of VTA-GABA and DA transmission (Di Giovanni et al., 2000; Di Matteo et al., 2000; Bankson and Yamamoto, 2004). Therefore, the role of 5-HT2CRs in the ethanol enhancement of mIPSC frequency was first investigated by assessing whether activation of 5-HT2CRs modulates baseline GABA release. Application of the selective 5-HT2CR agonist, Ro-60-0175 (200 nM), significantly enhanced mIPSC frequency (Fig. 4, A and B) over a time course that developed relatively slowly (Fig. 4, B and C) and continued to increase throughout the 12 min after removal of the drug. This pattern of prolonged drug action was similar to the prolonged actions of ethanol described previously. Finally, no change in mIPSC amplitude was observed (data not shown) in the presence of Ro-60-0175, thereby suggesting that 5HT2CR activation solely enhances GABA release. We verified the selectively of the actions of the 5-HT2C agonist by pretreating slices with the 5-HT2B/2C antagonist, SB200646 (4 μM), and under these conditions, the Ro-60-0175-induced increase in mIPSC frequency was completely abolished (Fig. 4, D and E; note the different scales used in Fig. 4, B versus E). In addition, application of 5-HT (50 μM) produced a significant enhancement in mIPSC frequency (Fig. 5), with no subsequent effect on amplitude (data not shown). Similar to the effects of Ro-60-0175, the enhancement by 5-HT did not fully wash out and actually increased beyond wash in three of seven neurons.

Fig. 4.

5-HT2CR activation increases GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons. A, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 200 nM Ro-60-0175 (after 10 min), and with 200 nM Ro-60-0175 (after 20 min). B, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in A and a wash. Event frequency under control conditions was 1.3 ± 0.2 Hz (n = 8; **, p < 0.01 by Student's t test different from control; **†, p < 0.01 by Student's t test different from Ro-60-0175 (Ro-60) at 10 min). C, time course for a sample representative neuron under conditions shown in A. The dotted lines represent the average frequency under each condition for that neuron. D, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron in the continued presence of 4 μM SB200646, with subsequent application of 200 nM Ro-60-0175. E, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in D and a wash to SB200646. Event frequency under pre-Ro-60-0175 conditions was 1.9 ± 0.7 Hz (n = 5).

Fig. 5.

5-HT increases GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons. A, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 50 μM 5-HT, and after a washout. B, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in A. Event frequency under control conditions was 1.2 ± 0.1 Hz (n = 7; *, p < 0.05 by a Student's t test different from control).

Ethanol Enhancement of GABA Release Is Dependent upon 5-HT2CR-Stimulated Release of Ca2+ From Intracellular Stores. To further validate that mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ is required for the 5-HT2C agonist activity, we studied the effect of CPA (10 μM) on Ro-60-0175 enhancement of mIPSC frequency. Addition of the 5-HT2C agonist after bath application of the SERCA pump inhibitor almost completely abolished the agonist-induced enhancement of mIPSC frequency (Fig. 6, A and B; 17 versus 56% increase as seen in Fig. 4B). Because ethanol appears to enhance GABA release through an IP3 cascade that may also be activated by 5-HT2CRs, then pharmacological blockade of the 5-HT2CR may significantly reduce or abolish ethanol potentiation of mIPSC frequency. Therefore, we pretreated slices with SB200646 for 5 to 10 min before application of ethanol (50 mM). SB200646 (4 μM) completely prevented the increase in mIPSC frequency normally observed after ethanol application (Fig. 6, C and D). There was no effect on mIPSC amplitude (data not shown). These data suggest that in the VTA, 5-HT2CR activation is necessary for the ethanol-induced increase in GABA release.

Fig. 6.

Ethanol enhancement of GABA release is dependent upon 5-HT2CR-stimulated release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. A, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron in the continued presence of 10 μM CPA, with subsequent application of 200 nM Ro-60-0175. B, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in A. Event frequency under pre-Ro-60-0175 conditions was 1.3 ± 0.2 Hz (n = 6; *, p < 0.05 by a Student's t test different from control). C, mIPSCs recorded from a VTA-DA neuron under control conditions, in the presence of 4 μM SB200646, and 50 mM ethanol with 4 μM SB200646. D, bar graph representing the percentage change ± S.E.M. above control mIPSC frequency for the conditions shown in C and a wash. Event frequency under control conditions was 2.7 ± 0.4 Hz (n = 10).

Discussion

In our initial report that characterized ethanol enhancement of VTA-GABA release, we primarily used recordings of spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs), which demonstrated that ethanol significantly enhanced sIPSC frequency in a concentration-dependent manner (Theile et al., 2008). Here, we have further investigated a variety of potential mechanisms for the ethanol enhancement through analysis of action potential-independent mIPSCs. Ethanol (15, 25, 50, and 75 mM) clearly increased mIPSC frequency but had no discernible effect on the amplitude, decay of mIPSCs, or any tonic GABA current. Baseline mIPSC frequency was reduced in the presence of CdCl2; however, neither CdCl2 nor the L-type VGCC antagonist, nicardipine, prevented ethanol enhancement of GABA release. Blockade of IP3Rs with 2-APB and depletion of intracellular stores with CPA both completely abolished the ethanol-induced increase in mIPSC frequency. Finally, addition of both 5-HT and the 5-HT2CR agonist, Ro-60-0175, increased mIPSC frequency over a similar time course as that seen with ethanol. Blockade with the 5-HT2CR antagonist, SB200646, abolished ethanol enhancement of mISPC frequency and that after application of the selective 5-HT2CR agonist. Thus, our primary conclusion is that the ethanol-induced enhancement in GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons is mediated via 5-HT2CR activation, which under normal conditions would subsequently release Ca2+ from IP3-sensitive stores.

Although our prior report was the first to assess ethanol modulation of GABA release in VTA (Theile et al., 2008), Ye and colleagues recently reported that ethanol (10–40 mM) may have differential effects on VTA action potential-dependent GABA release. Thus, although under control conditions, ethanol appeared to decrease GABA release, an increase in sIPSC frequency was observed in the presence of saturating concentrations of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) agonist DAMGO (Xiao and Ye, 2008). The authors contend that application of DAMGO silences VTA interneurons via activation of somatic and dendritic MORs, thereby unmasking the stimulatory effect of ethanol on other GABAergic inputs. To us, the most parsimonious explanation for these somewhat disparate findings is that, under control conditions, our VTA slice preparation must possess a higher level of endogenous opioid tone and thus mimic the conditions demonstrated by Xiao et al. (2008). On the other hand, Bergevin et al. (2002) have reported the presence of MORs on GABAergic terminals in the VTA. This observation complicates the hypothesis presented by Xiao et al. (2008). Nevertheless, it is also important to note that ethanol has been reported to potentiate GABA release in a majority of brain regions studied; therefore, our observations in the VTA are consistent with the broad literature (for review, see Siggins et al., 2005; Weiner and Valenzuela, 2006).

Activation of VGCCs increases intraterminal Ca2+ levels to initiate neurotransmitter release. Therefore, we examined the role that VGCCs may serve in ethanol modulation of GABA release in the VTA. Typically, VGCCs, such as N- and P/Q-type channels, are primarily involved in action potential-dependent neurotransmitter release (Wheeler et al., 1994). Although these experiments were conducted in the presence of TTX to block action potentials, L- and P/Q-type VGCCs have been shown to support GABA release onto Meynert neurons independent of action potentials (Rhee et al., 1999). Although application of the nonspecific VGCC inhibitor, CdCl2, alone resulted in a decrease in the baseline mIPSC frequency similar to that observed by another group (Bergevin et al., 2002), it did not prevent the stimulatory effect of ethanol. However, the magnitude of ethanol enhancement was slightly reduced compared with the results shown in Fig. 1, and this observation may be attributable to a partial depletion of the store as a result of extended blockade of extracellular Ca2+ influx. Application of nicardipine, an L-type channel inhibitor, had no effect on baseline mIPSC frequency and similarly did not block the ethanol-induced enhancement in mIPSC frequency. These results suggest that although certain VGCCs contribute partly to basal VTA-GABA release, they are not important in the mechanism of ethanol enhancement of GABA release.

Because influx of Ca2+ through VGCCs does not appear to underlie ethanol stimulation of GABA release, we next investigated the dependence of ethanol enhancement on intracellular Ca2+ stores. Ethanol enhancement of intracellular Ca2+ levels is well documented in the literature. Early work showed that pharmacologically relevant concentrations of ethanol facilitated Ca2+ release from IP3-sensitive stores in brain microsomes (Daniell and Harris, 1989). In addition, release of Ca2+ from presynaptic cytosolic pools can facilitate GABA release in a variety of brain regions (Savić and Sciancalepore, 1998; Rhee et al., 1999; Kelm et al., 2007). Application of the IP3R antagonist, 2-APB, prevented the ethanol enhancement of mIPSC frequency. These findings are comparable with recent observations in the cerebellum (Kelm et al., 2007). High concentrations of 2-APB have been suggested to lack selectivity, yet such issues arise at concentrations higher than 80 μM (Missiaen et al., 2001). Therefore, we used a considerably lower concentration and did not observe any nonspecific effects, as demonstrated by the lack of change in mIPSC frequency in the presence of 2-APB alone. We further tested the dependence of intracellular Ca2+ stores by depleting these stores using the SERCA pump inhibitor, CPA. Application of CPA likewise had no effect on baseline mIPSC frequency, and subsequent application of ethanol failed to elicit the reliable increase in mIPSC frequency. Together with the 2-APB results, we conclude that IP3-mediated Ca2+ release is necessary for ethanol-induced enhancement in GABA release.

DA output from the VTA is modulated by 5-HT-containing neurons originating from the midbrain raphe nuclei, which innervate both DA and non-DA neurons (Hervé et al., 1987). 5-HT2CR activation leads to phosphatidylinositol turnover and subsequent Ca2+ release via IP3R activation (Conn et al., 1986). Modulation of midbrain DA neuron activity via 5-HT2CRs is believed to occur indirectly through changes in GABAergic transmission (Di Giovanni et al., 2000). Here, we demonstrated a 5-HT2CR-dependent increase in GABA release because application of 5-HT or the selective 5-HT2CR agonist, Ro-60-0175, resulted in a prolonged enhancement in mIPSC frequency, of which the latter effect was abolished in the presence of the 5-HT2C-selective antagonist, SB200646. This enhancement also was reduced substantially by the SERCA pump inhibitor, CPA, suggesting that this component is Ca2+ mediated. Most importantly, we observed that blockade with SB200646 abolished the ethanol-mediated enhancement in GABA release. These results are consistent with previous studies. Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (Ecstasy) increases GABA release in the VTA through a 5-HT2CR-dependent mechanism (Bankson and Yamamoto, 2004). In the substantia nigra, local and systemic administration of Ro-60-0175 was observed to stimulate GABA release (Invernizzi et al., 2007). Thus, although we cannot rule out other metabotropic receptors that may also activate GABA release in an ethanol-responsive manner as we report here, it does appear that the 5-HT2CR is a prime candidate for the physiological regulation of GABA release in the VTA and a target of ethanol modulation as well.

Multiple labs have demonstrated that ethanol produces an acute enhancement of VTA-DA neuron excitability. Here and in a previous report (Theile et al., 2008), we observe a seemingly contradictory enhancement in inhibitory drive onto VTA-DA neurons. Thus, ethanol possesses an apparent biphasic action to directly enhance both DA neuron excitability and inhibitory drive onto DA neurons. This concept may have implications for the development of novel therapies for treating alcohol craving. For instance, the MOR antagonist, naltrexone, is one of the few approved agents for craving. One prominent action of MOR activation is a reduction in GABA release onto VTA-DA neurons, thus enhancing their excitability (Johnson and North, 1992a; Bergevin et al., 2002). Therefore, we hypothesize that a derangement in VTA-GABA function, at least in part, may underlie ethanol dependence and craving. As a consequence, one possible therapeutic mechanism of MOR antagonism may be to normalize GABA release and thus amplify the ethanol-induced increase in GABA release to diminish or temper the direct reinforcing action of ethanol on VTA-DA neurons. Because we show herein that activation of 5-HT2CRs enhances GABA release and is critical in ethanol modulation of GABAergic inhibition onto VTA-DA neurons, novel pharmacotherapies for alcohol craving might focus on this mechanism for directly enhancing inhibitory drive onto these neurons.

Here, we demonstrate that ethanol enhances VTA-GABA release in a manner that is dependent on activation of 5-HT2CRs, which activate the IP3 receptor cascade and, subsequently, Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. We consider that the most logical site of ethanol action is upstream of the 5-HT2CR. Ethanol increases 5-HT release in the NAc (Yoshimoto et al., 1992) and prevents 5-HT reuptake in the hippocampus (Daws et al., 2006). Therefore, it is conceivable that ethanol may also stimulate 5-HT release in the VTA, which subsequently results in the activation of 5-HT2CRs. This is certainly a possibility given that application of 5-HT enhances GABA release in our preparation. Nevertheless, given the results presented here, 5-HT2C/IP3R activation represents a primary candidate for the mechanism by which ethanol enhances GABA release in the VTA; taken together, this novel action of ethanol may present new avenues for development of agents to treat alcohol craving.

This work was supported in part by the F. M. Jones and H. L. Bruce Endowed Graduate Fellowship; the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [Grant 1F31AA017020]; and the National Institutes of Health [Grants RO1AA14874, RO1AA1516].

Parts of this work were previously presented at the following conferences: Theile JW, Morikawa H, Gonzales RA, and Morrisett RA (2008) Role of extracellular and intracellular calcium in ethanol enhancement of GABAergic transmission onto VTA-dopamine neurons. Joint Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism and the International Society for Biomedical Research on Alcoholism; 2008 Jun 27-Jul 2, 2008. Washington, D.C.; and Theile JW, Morikawa H, Gonzales RA, and Morrisett RA (2008) Role of 5-HT2C receptors and calcium in ethanol enhancement of GABAergic transmission onto VTA-dopamine neurons. Society for Neuroscience; 2008 Nov 15-19; Washington, D.C.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.108.147793.

ABBREVIATIONS: VTA, ventral tegmental area; DA, dopaminergic; NAc, nucleus accumbens; DAMGO, [d-Ala2, N-Me-Phe4, Gly5-ol]-en-kephalin; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT2CR, 5-HT2C receptor; IP3, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate; aCSF, artificial cerebrospinal fluid; mIPSC, miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current; TTX, tetrodotoxin; 2-APB, 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane; Ro-60-0175, (αS)-6-chloro-5-fluoro-α-methyl-1H-indole-1-ethanamine fumarate; SB200646, N-(1-methyl-5-indoyl)-N-(3-pyridyl)urea hydrochloride; ANOVA, analysis of variance; K-S, Kolmogorov-Smirnov; VGCC, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel; IP3R, IP3 receptor; SERCA, sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase; CPA, cyclopiazonic acid; sIPSC, spontaneous IPSC; MOR, μ-opioid receptor.

References

- Albanese A and Minciacchi D (1983) Organization of the ascending projections from the ventral tegmental area: a multiple fluorescent retrograde tracer study in the rat. J Comp Neurol 216 406-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankson MG and Yamamoto BK (2004) Serotonin-GABA interactions modulate MDMA-induced mesolimbic dopamine release. J Neurochem 91 852-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergevin A, Girardot D, Bourque MJ, and Trudeau LE (2002) Presynaptic mu-opioid receptors regulate a late step of the secretory process in rat ventral tegmental area GABAergic neurons. Neuropharmacology 42 1065-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Pesold C, and Appel SB (1999) Ethanol directly excites dopaminergic ventral tegmental area reward neurons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23 1848-1852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubar MJ and Cunningham KA (2007) Distribution of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience 146 286-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Sanders-Bush E, Hoffman BJ, and Hartig PR (1986) A unique serotonin receptor in choroid plexus is linked to phosphatidylinositol turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83 4086-4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniell LC and Harris RA (1989) Ethanol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate release calcium from separate stores of brain microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 250 875-881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daws LC, Montañez S, Munn JL, Owens WA, Baganz NL, Boyce-Rustay JM, Millstein RA, Wiedholz LM, Murphy DL, and Holmes A (2006) Ethanol inhibits clearance of brain serotonin by a serotonin transporter-independent mechanism. J Neurosci 26 6431-6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G, Di Matteo V, Di Mascio M, and Esposito E (2000) Preferential modulation of mesolimbic vs. nigrostriatal dopaminergic function by serotonin(2C/2B) receptor agonists: a combined in vivo electrophysiological and microdialysis study. Synapse 35 53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Mascio M, Di Giovanni G, Di Matteo V, Prisco S, and Esposito E (1998) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors reduce the spontaneous activity of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res Bull 46 547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo V, Di Giovanni G, Di Mascio M, and Esposito E (2000) Biochemical and electrophysiological evidence that RO 60-0175 inhibits mesolimbic dopaminergic function through serotonin(2C) receptors. Brain Res 865 85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle-Wang K, Mikeladze Z, Uryu K, and Chesselet MF (1997) Pattern of expression of the serotonin2C receptor messenger RNA in the basal ganglia of adult rats. J Comp Neurol 384 233-247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JE (1995) Addiction medicine. J Am Med Assoc 273 1656-1657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessa GL, Muntoni F, Collu M, Vargiu L, and Mereu G (1985) Low doses of ethanol activate dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res 348 201-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales RA and Weiss F (1998) Suppression of ethanol-reinforced behavior by naltrexone is associated with attenuation of the ethanol-induced increase in dialysate dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci 18 10663-10671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace AA and Onn SP (1989) Morphology and electrophysiological properties of immunocytochemically identified rat dopamine neurons recorded in vitro. J Neurosci 9 3463-3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricson AW, Thomas MP, Lippmann MJ, and Morrisett RA (2003) Suppression of L-type voltage-gated calcium channel-dependent synaptic plasticity by ethanol: analysis of miniature synaptic currents and dendritic calcium transients. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 307 550-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervé D, Pickel VM, Joh TH, and Beaudet A (1987) Serotonin axon terminals in the ventral tegmental area of the rat: fine structure and synaptic input to dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res 435 71-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (1996) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 7th ed, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, Washington, DC.

- Invernizzi RW, Pierucci M, Calcagno E, Di Giovanni G, Di Matteo V, Benigno A, and Esposito E (2007) Selective activation of 5-HT(2C) receptors stimulates GABAergic function in the rat substantia nigra pars reticulata: a combined in vivo electrophysiological and neurochemical study. Neuroscience 144 1523-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW and North RA (1992a) Opioids excite dopamine neurons by hyperpolarization of local interneurons. J Neurosci 12 483-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SW and North RA (1992b) Two types of neurone in the rat ventral tegmental area and their synaptic inputs. J Physiol 450 455-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelm MK, Criswell HE, and Breese GR (2007) Calcium release from presynaptic internal stores is required for ethanol to increase spontaneous gamma-aminobutyric acid release onto cerebellum Purkinje neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323 356-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama S, Brodie MS, and Appel SB (2007) Ethanol inhibition of m-current and ethanol-induced direct excitation of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol 97 1977-1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, Callewaert G, De Smedt H, and Parys JB (2001) 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate affects the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, the intracellular Ca2+ pump and the non-specific Ca2+ leak from the non-mitochondrial Ca2+ stores in permeabilized A7r5 cells. Cell Calcium 29 111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa H, Imani F, Khodakhah K, and Williams JT (2000) Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-evoked responses in midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 20 RC103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullikin-Kilpatrick D and Treistman SN (1995) Inhibition of dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca++ channels by ethanol in undifferentiated and nerve growth factor-treated PC12 cells: interaction with the inactivated state. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 272 489-497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oades RD and Halliday GM (1987) Ventral tegmental (A10) system: neurobiology: I. Anatomy and connectivity. Brain Res 434 117-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Harnett MT, and Morikawa H (2006) Hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) is an ethanol target in midbrain dopamine neurons of mice. J Neurophysiol 95 619-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee JS, Ishibashi H, and Akaike N (1999) Calcium channels in the GABAergic presynaptic nerve terminals projecting to Meynert neurons of the rat. J Neurochem 72 800-807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetti ZL, Hmaidan Y, and Gessa GL (1992) Marked inhibition of mesolimbic dopamine release: a common feature of ethanol, morphine, cocaine and amphetamine abstinence in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 221 227-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savić N and Sciancalepore M (1998) Intracellular calcium stores modulate miniature GABA-mediated synaptic currents in neonatal rat hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosci 10 3379-3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Dayan P, and Montague PR (1997) A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 275 1593-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler NW, Jona I, Vegh M, and Martonosi A (1989) Cyclopiazonic acid is a specific inhibitor of the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 264 17816-17823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siggins GR, Roberto M, and Nie Z (2005) The tipsy terminal: presynaptic effects of ethanol. Pharmacol Ther 107 80-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theile JW, Morikawa H, Gonzales RA, and Morrisett RA (2008) Ethanol enhances GABAergic transmission onto dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area of the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32 1040-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins DM, Joharchi N, Tampakeras M, Martin JR, Wichmann J, and Higgins GA (2002) An investigation of the role of 5-HT(2C) receptors in modifying ethanol self-administration behaviour. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 71 735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walaas I and Fonnum F (1980) Biochemical evidence for gamma-aminobutyrate containing fibres from the nucleus accumbens to the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area in the rat. Neuroscience 5 63-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JL and Valenzuela CF (2006) Ethanol modulation of GABAergic transmission: The view from the slice. Pharmacol Ther 111 533-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F, Lorang MT, Bloom FE, and Koob GF (1993) Oral alcohol self-administration stimulates dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens: genetic and motivational determinants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 267 250-258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, and Tsien RW (1994) Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science 264 107-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C and Ye JH (2008) Ethanol dually modulates GABAergic synaptic transmission onto dopaminergic neurons in ventral tegmental area: role of mu-opioid receptors. Neuroscience 153 240-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto K, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, and Li TK (1992) Alcohol stimulates the release of dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens. Alcohol 9 17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]