Abstract

Purpose

Eriodictyol, a flavonoid found in citrus fruits, is among the most potent compounds reported to protect human RPE cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death. In the present study, we determined whether eriodictyol-induced phase II protein expression further enhances the resistance of human ARPE-19 cells to oxidative stress.

Methods

We analyzed the ability of eriodictyol to activate Nrf2 and induce the phase II proteins, heme-oxygenase (HO-1), NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO-1), and the cellular antioxidant glutathione, (GSH). We performed cytoprotection assays in ARPE-19 cells that were overexpressing HO-1 or NQO-1. We compared cell survival after short-term and long-term eriodictyol treatment and tested the mechanism of protection using a dominant negative Nrf2 and an shRNA specific for HO-1.

Results

We demonstrate that eriodictyol induces the nuclear translocation of Nrf2, enhances the expression of HO-1 and NQO-1, and increases the levels of intracellular glutathione. We show that ARPE-19 cells that overexpress HO-1 or NQO-1 are more resistant to oxidative stress-induced cell death than control cells. We demonstrate that eriodictyol induces long-term protection that is significantly greater than its short-term protection, and this effect is correlated temporally with both the activation of Nrf2 and the induction of phase II enzymes. We demonstrate that this effect can be blocked with the use of a dominant negative to Nrf2 and an shRNA specific to HO-1.

Conclusions

These findings indicate the greatest benefit from eriodictyol may be its ability to regulate gene expression and enhance multiple cellular defenses to oxidative injury.

Introduction

Vitamins, antioxidants, carotenoids and zinc are considered to be valuable dietary supplements for preventing vision loss in patients with age-related macular degeneration. The AREDS study (Age-Related Eye Disease Study) showed that antioxidants and mineral supplements can preserve vision in patients with macular degeneration 1. Clinical practice guidelines now emphasize the importance of maintaining a high dietary intake of fruits, vegetables, antioxidants and vitamins, in an attempt to block the progression of macular degeneration.

Flavonoids are structurally heterogeneous, polyphenolic compounds which are regularly consumed in the human diet and are present at high concentrations in fruits, vegetables and other plant-derived foods, such as teas and other beverages 2. Many of the health benefits associated with the Mediterranean diet have been attributed to flavonoids, including protection from cardiovascular disease and cancer3. Evolutionary studies suggest that flavonoids have evolved to protect plant tissues from chronic exposure to ultraviolet light and epidemiologic studies have identified flavonoids in many foods that are associated with a reduction in the risk of advanced macular degeneration4–6. Flavonoids accumulate in the mammalian eye7–9 and there are anecdotal cases of improved visual function following the consumption of bilberry fruits that contain high concentrations of anthocyanins (for review, see10). As a result, there is considerable interest in understanding the potential role and benefit of flavonoids in ocular health and disease prevention.

Flavonoids can provide both short and long-term protection against oxidative stress through a variety of mechanisms. Flavonoids are potent antioxidants, neutralizing toxic reactive oxygen species by donating hydrogen ions11. Yet, potentially even more importantly, flavonoids can modulate multiple cell signaling pathways and induce the expression of phase II proteins 12, which protect against oxidative stress by catalyzing a wide variety of reactions that neutralize reactive oxygen species, toxic electrophiles and carcinogens. Phase II proteins are regulated by the transcription factor, NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which binds to the antioxidant-response element (ARE), a cis-acting enhancer sequence in the promoter of phase II proteins, resulting in the activation of gene transcription13. Numerous in scope, phase II proteins are regulated as a group in a coordinated manner through the Nrf2/ARE pathway and include enzymes such as γ-glutamylcysteine ligase and glutathione synthetase, that regulate the key steps in glutathione biosynthesis; heme-oxygenase-1, that catalyzes the breakdown of heme proteins into iron, the vasodilator carbon monoxide and biliverdin (which is further reduced to the antioxidant bilirubin); NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO-1), a reducing agent that plays a role in antioxidant defenses with the cofactor NADH or NADPH; and thioredoxin, a key cellular antioxidant; and others 14–16. The phase II proteins HO-1 and NQO-1 are expressed in both the retina and RPE and are upregulated in response to UV light and inflammation 17, 18. Because of the coordinated expression of phase II enzymes, both HO-1 and NQO-1 are useful markers of retinal and RPE phase II protein expression 14.

From a biological perspective, there are key advantages for a cell to induce phase II proteins to fight oxidative stress. In contrast to direct antioxidants which are consumed immediately after their interaction with a reactive oxygen species, the induction of phase II proteins allows the cell to mount a more prolonged and sustained defense to oxidative injury that will function long after the direct antioxidants are consumed. Phase II proteins are induced by a variety of compounds that use phase II enzymes for detoxification and degradation, including pro-oxidant xenobiotics, chemically reactive carcinogens, chemopreventive agents (such as sulforaphane and oltipraz), antioxidants and specific bioflavonoids 14, 19, 20.

In a recent study, we showed that specific dietary flavonoids could protect both human primary and ARPE-19 cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death, when added either simultaneously or within one hour prior to oxidant exposure 21. These experiments analyzed the effects of short-term treatment with flavonoids on the resistance of ARPE-19 cells to oxidative stress. Following this study, the question arose as to whether flavonoid-induced phase II protein expression could provide a significant additional benefit to RPE cells by allowing them to resist higher levels of oxidative stress than they could resist with short-term treatment. Thus, as a follow-up to our initial study, we pre-treated RPE cells with flavonoids for several hours in order to induce phase II protein expression and we compared the outcome of this treatment to that seen following the addition of the flavonoid at the time of the oxidant exposure. We focused on the flavonoid eriodictyol because we had previously shown that it had the highest potency of all flavonoids that we tested in our oxidative stress assay, and it strongly induced the activation of Nrf2 and heme-oxygenase21. The goal of the current study was to address the following questions: 1) Does eriodictyol lead to a time dependent and dose dependent increase in the expression of Nrf2 and the phase II proteins, heme-oxygenase (HO-1) and NADP(H):quinone oxidoreductase (NQO-1)?, 2) Does the expression of these enzymes protect ARPE-19 cells from oxidative stress and does the knockdown of one of theses proteins abate this protection?, 3) Is there a correlation between eriodictyol-induced phase II protein expression and eriodictyol-induced long-term protection of ARPE-19 cells?, 4) Is the long-term protection greater than the short-term protection induced as a result of the direct antioxidant properties of eriodictyol?, and 5) Is the long-term protection mediated through the Nrf2/ARE pathway and can it be blocked by a dominant negative to Nrf2? The answers to these questions show that the induction of phase II protein expression by eriodictyol significantly enhances the resistance of RPE cells to oxidative injury and provides a mechanism whereby flavonoids can augment their activity as direct antioxidants and induce more sustained resistance to oxidative damage over the long-term.

Methods

Reagents

Eriodictyol, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), dimethylsulfoxide and anti-β actin monoclonal antibody (AC-15) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc (Saint Louis, MO, U.S.A.). Anti-Nrf2 (H-300) rabbit polyclonal antibody was purchased form Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA) and anti-NQO-1 mouse monoclonal and anti-HO-1 rabbit polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Assay Designs, Inc. (Ann Arbor, MI). Horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibodies were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). All antibodies were used at the dilutions recommended by the manufacturer.

Plasmid Constructs

The dominant-negative mutant of Nrf2, Nrf2M, was generated by Dr. Jawed Alam (Alton Ochsner Medical Foundation, New Orleans, LA) 22 and was supplied to us by Dr. Andy Y Shih (University of California-San Diego). Nrf2M, lacking the N-terminal transcriptional activation domain, was generated by deleting amino acid residues 1–392. It sequesters Nrf2 dimerization protein(s), competes for Nrf2 DNA binding domains, and blocks the induction of HO-122. The human wild-type NQO-1 expression plasmid (pcDNA-hNQO-1) was a kind gift from Dr. David Ross (School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, CO). The empty control plasmid pcDNA3.1(−) (CMV3) was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. The human heme oxygenase 1 expression plasmid (HMOX-1), shRNA HO-1 plasmid and their control plasmids were purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD).

Cell Culture

Human adult retinal pigment epithelial (ARPE-19) cells were a gift from Dr. Larry Hjelmeland (University of California, Davis, CA) and were grown in DMEM/F12 medium (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, Utah), 15 mM N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2.5 mM L-glutamine, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate and 20 mM sodium bicarbonate. As previously reported, the ARPE-19 cells used in these experiments grow with differentiated morphology, express cellular markers of differentiation, including RPE65, and behave similar to primary human RPE cultures 21. The cells were dissociated from the culture dishes using versene (0.53 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA] in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution) followed by 0.25% trypsin/EDTA.

Cytotoxicity assay

ARPE-19 were seeded onto 96-well plates at 20,000 cells/well, grown for 24 hours, replenished with fresh culture media containing 10% dialyzed FBS (Hyclone, Logan, Utah) and preincubated with eriodictyol for 1–24 hours before the addition of the chemical oxidants. t-BOOH was added at concentrations which had been found to kill >80–90% of the cultured cells in dose-response assays. In a previous study, where we have shown that the concentrations of t-BOOH which are necessary to kill ARPE-19 cells are density dependent but not differentiation dependent, further details of this assay can be found21. After an overnight incubation, cell viability was determined by a modified version of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay 23. The MTT assay was performed by removing the cell culture medium and replacing it with 100 μl of fresh culture medium containing 0.5 μg/μl MTT. After 4 hours of incubation at 37°C, cells were solubilized overnight with 100 μl of a solution containing 50% dimethylformamide and 20% SDS (pH 4.7). The absorbance at 560 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Spectromax 190, Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). To assure that the spectrophotometric readings correlated with cell viability, all cells were examined by microscopy prior to the addition of the MTT. Each experiment was performed at least three times and multiple controls were included. For each concentration, six wells were analyzed. Of these six wells, the cells in two of these wells were treated with eriodictyol alone in order to screen for any potential toxicity. The cells in the remaining four wells were treated with eriodictyol and t-BOOH. Background absorbance values consisted of blank wells (with no cells) into which media, MTT dye and solubilization buffer were added. The background readings were subtracted from the average absorbance readings of the treated wells to obtain an adjusted absorbance reading that represented cell viability. This reading was divided by the adjusted absorbance reading of untreated cells in control wells to obtain a % survival value. The cell survival data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 4 software (San Diego, CA).

Cell transfections

ARPE-19 cells were transfected in 96-well plates, one day prior to transfection. Plasmid DNA was diluted with Opti-MEM serum-free medium (without antibiotics) and the transfection complex was formed at room temperature for 20 minutes prior to incubation with the cells. Transfections were performed with either Lipofectamine 2000, Lipofectamine ltx (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) or Fugene HD (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to manufacturer’s instructions. ARPE-19 cells were exposed to the transfection complex of either HMOX-1 or pcDNA-hNQO-1 for 16–24 hours. Cells transfected with lipofectamine 2000 and HMOX-1 were allowed to recover for 24–36 hours before treatment with t-BOOH. Cells transfected with Fugene HD and pcDNA-hNQO-1 were treated with t-BOOH after 8 hours, which was adequate time for recovery. Lipofectamine ltx was used for the transfection of cells with dominant negative Nrf2 and with shRNA HO-1. For these experiments the cells were exposed to the transfection complex for 24 hours, prior to treatment with 50 μM eriodictyol for 16 hours and then exposed to t-BOOH for 24 hours before determining cell viability as described above.

Eriodictyol treatment and phase II protein expression

To evaluate the effect of eriodictyol on the activation of the transcription factor, Nrf2, and the expression of the phase II proteins, HO-1 and NQO-1, ARPE-19 cells were plated onto 60 mm2 plates in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, 20 mM sodium bicarbonate and treated the following day with eriodictyol at a concentration of 0–100 μM for 2–24 hours. To ensure that all cells for the various time points were in fact in culture for the same amount of time, the addition of eriodictyol was performed in the following manner. At time 0 all the cells were transferred to 10% DFCS in DMEM/F12 and eriodictyol was added to the wells of the 24 hour time points. Eight hours before the end of the 24 hour period, the eriodictyol was added to the 8 hour plate, and this was repeated for the 6 and 4 hour plate, such that all plates reached their end point at the same time, and thus, were harvested at the end of the 24 hour time period. For Nrf2, cells were washed twice in ice-cold Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and scraped into nuclear fractionation buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM (dithiothreitol) DTT, 1mM PMSF). After a 15 minute incubation at 4°C, 10% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) was added to achieve a final concentration of 0.625%. The cells were vortexed for 10 seconds, centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 seconds to pellet nuclei, resuspended in nuclear fractionation buffer containing NP-40 and sonicated gently to break up nuclei. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA protein assay and nuclear extracts were analyzed by Western blotting. For HO-1 and NQO-1, cells were rinsed twice in ice-cold TBS, scraped into cell lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 1 mM PMSF), incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. Protein levels were determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Western blots were performed using fifteen μg of total protein as previously described 21.

GSH analysis

ARPE-19 cells were plated into 6-well dishes at 7.5 × 105 cells/well, replenished the following day with fresh DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum, 20 mM sodium bicarbonate, and treated with eriodictyol in a dose and time dependent manner. As described above, the time course experiments were perform such that cells from all time points were incubated for the same amount of time thus avoiding any differences in levels of GSH as a consequence of culture time. The following day the cells were trypsinized, pelleted, washed twice with ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. The cell suspension was sonicated and centrifuged at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to two microfuge tubes; one for protein determination using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and the other for the GSH assay. The sample was deproteinated immediately following the collection of the supernatant and the GSH assay were performed using the NWLSS Glutathione Assay (Northwest Life Science Specialties, LLC, Vancouver, WA) as described in the instruction booklet using the Tietze modified method.

Results

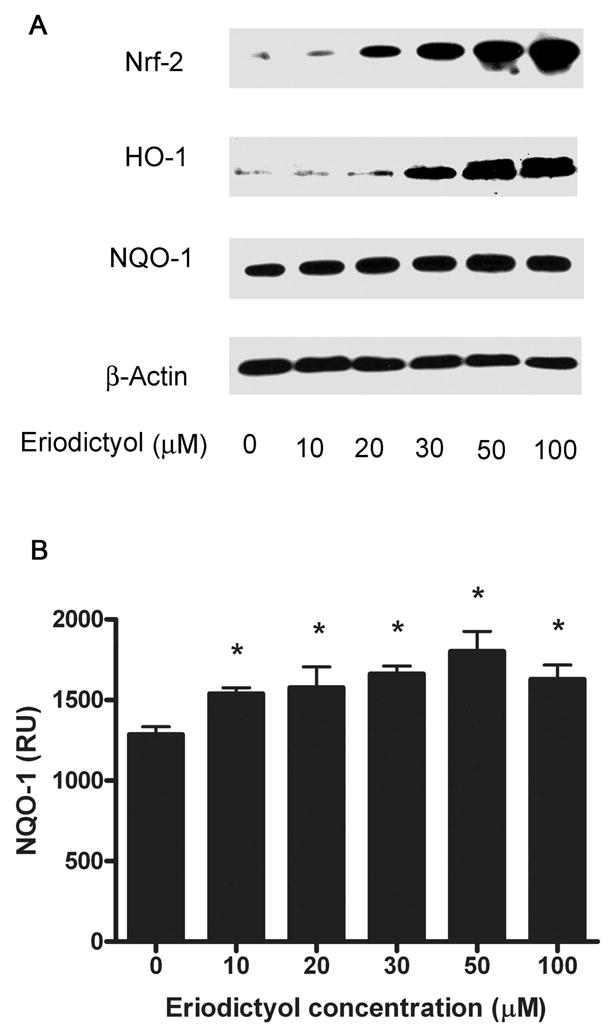

Eriodictyol activates Nrf2 and the expression of the phase II proteins, HO-1 and NQO-1

In order to examine the effect of eriodictyol on phase II protein expression, we performed a dose response study in ARPE19 cells. We found that eriodictyol induces the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A). The activation of Nrf2 correlates with an increase in the expression of HO-1 (Figure 1A) and a modest, although significant, increase in the expression of NQO-1 (Figure 1A and B). In the absence of eriodictyol, ARPE-19 cells do not express HO-1, whereas there is some constitutive expression of NQO-1. Given the results of this study, we used 50 μM eriodictyol for our further experiments.

Figure 1. Eriodictyol activates the expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO-1 in a dose-response manner.

ARPE-19 cells were pretreated with eriodictyol (0–100 μM) for 2 hours to induce Nrf2 expression or overnight to induce HO-1 and NQO-1 expression. (A) Immunoblot analysis of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO-1 and β-actin expression. 15 ug protein/per lane was loaded onto gels. The blots were incubated for 16 hrs. with Nrf2 (1:500), HO-1 (1:500), NQO-1 (1:5000.) and β-actin (1:4000.) in blotto (TBS containing 2% NFM). Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared to analyze the expression of Nrf2, and HO-1, NQO-1 and β-actin, respectively. (B). Densitometry and statistical analysis of NQO-1 expression in the eriodictyol dose response. The signals for NQO-1 expression in APRE-19 cells following pretreatment with eriodictyol (0–100 μM) were quantified using the Quantity One 4.2.1 quantification software (Bio-Rad) and statistical analysis was performed. The results are mean ± SE of three different experiments. *p < 0.05.

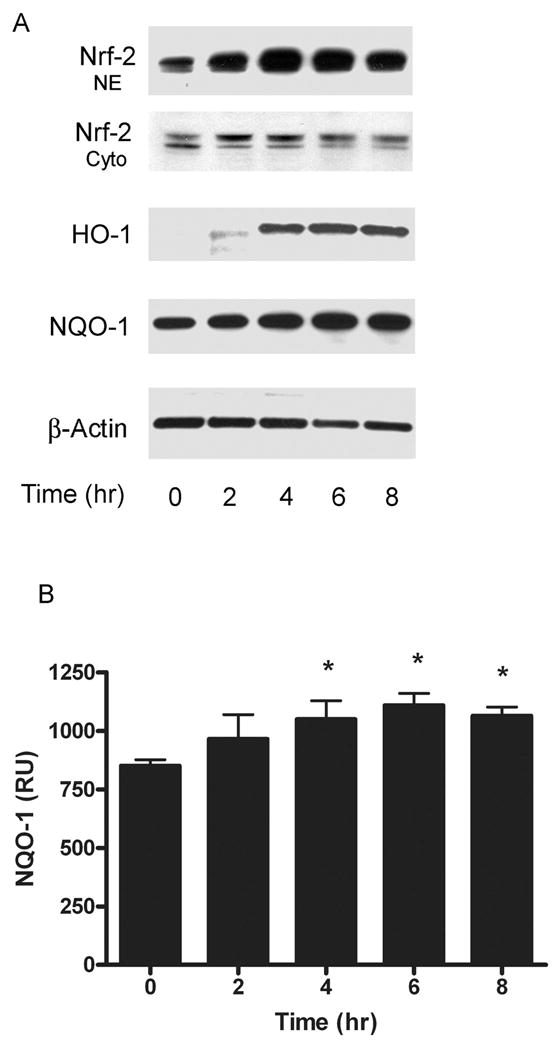

To determine the temporal sequence of phase II protein expression, we analyzed the activation of Nrf2 during the first eight hours after treatment with 50 μM eriodictyol. We found that the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 occurs within two hours, reaches a maximum by 4 hours and is still elevated 8 hrs after treatment (Figure 2A, NE). While the nuclear level of Nrf2 is significantly increased in response to eriodictyol, the cytosolic level remains relatively unaffected (Figure 2A, Cyto).

Figure 2. Time course of eriodictyol–induced expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO-1.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of Nrf2, HO-1, NQO-1 and β-actin expression ARPE-19 cells were pretreated with 50 μM eriodictyol for 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 hours, after which nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared to analyze the subcellular distribution of Nrf2, and cytoplasmic extracts were to prepared to analyze the time course of HO-1, NQO-1 and β-actin expression. (B) Densitometry and statistical analysis of the NQO-1 expression in the eriodictyol time course. The signals for NQO-1 expression in APRE-19 cells following pretreatment with eriodictyol (0–8 hours) were quantified using the Quantity One 4.2.1 quantification software (Bio-Rad) and statistical analysis was performed. The results are mean ± SE of three different experiments. *p < 0.05.

If the expression of phase II enzymes were induced by Nrf2 activation, we reasoned that we should observe a temporal correlation between the upregulation of HO-1, NQO-1 and the activation of Nrf2. As shown in Figure 2A, the expression of HO-1 begins within 2 hours after the activation of Nrf2 and reaches a maximum by 6–8 hours. A modest, but significant, time-dependent increase in NQO-1 expression is also observed (Figure 2A, NQO-1 and 2B). As expected, the upregulation of HO-1 and NQO-1 correlates with the induction of Nrf2.

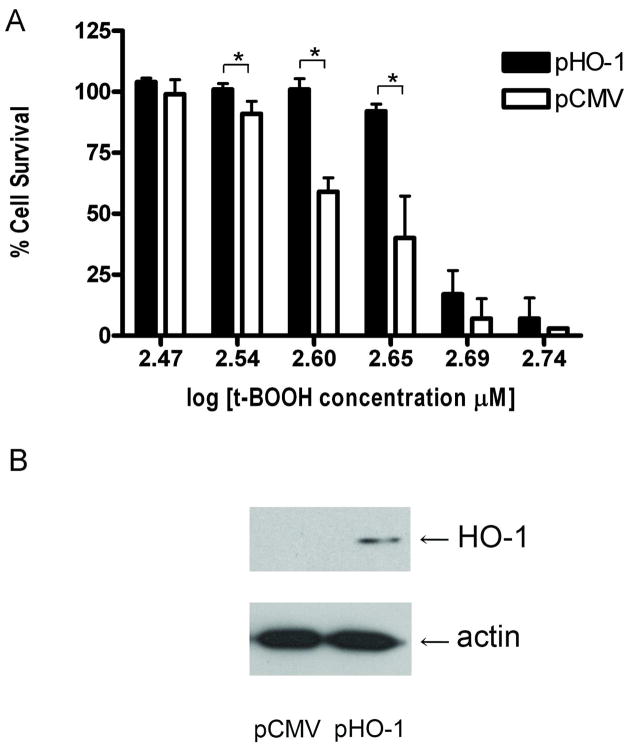

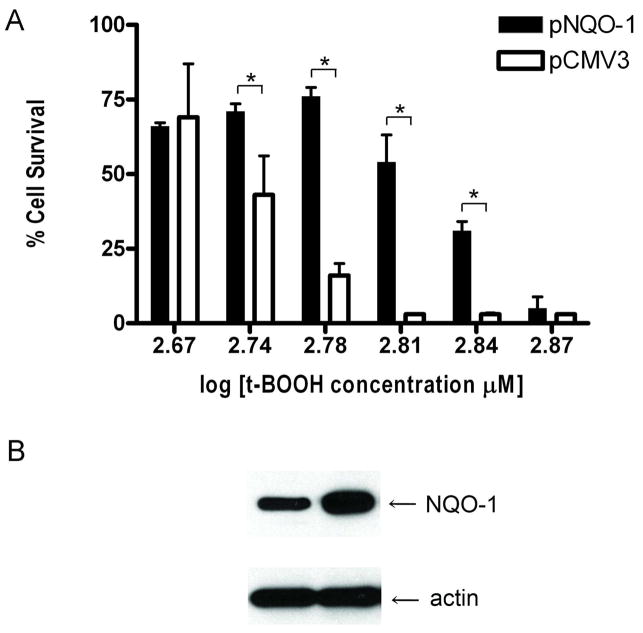

Overexpression of HO-1 and NQO-1 protects cells from oxidative stress

If phase II proteins increase cellular defenses to oxidative stress, we reasoned that RPE cells that overexpress phase II proteins would have a greater resistance to the oxidative injury. To examine this question, we transfected ARPE-19 cells with HO-1 and NQO-1 expression constructs. We found that ARPE-19 cells that overexpress the phase II proteins HO-1 or NQO-1 are more resistant to oxidative stress-induced cell death than cells transfected with the control plasmid. Overexpression of HO-1 results in >90% cell survival at concentrations of t-BOOH that kill up to 60% of the control cells (Figure 3A). Similarly, overexpression of NQO-1, results in ~75% cell survival at concentrations of t-BOOH that kill over 75% of control cells (Figure 4A). Western blots showing the overexpression of HO-1 and NQO-1 from these constructs are shown in Figures 3B and 4B, respectively.

Figure 3. Overexpression of heme oxygenase 1 protects cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death.

ARPE-19 cells were transiently transfected with either the human wild-type HO-1 expression plasmid,HMOX-1,(pHO-1) or control plasmid, pCMV6 (pCMV). (A) Cell survival of HO-1-overexpressing ARPE-19 cells. The day after transfection, the cells were exposed to t-BOOH for 24 hours and cell viability was determined by a modified version of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The results are mean ± SE of triplicates (*p < 0.05) and are a representative experiment from a set of five independent studies. (B) Immunoblot detection of HO-1 expression plasmid. Twenty-four hours following transfection, ARPE-19 cells were harvested and cell lysates were prepared for determining HO-1 and β-actin expression by immunoblotting.

Figure 4. Overexpression of NQO-1 protects cells from oxidative stress-induced cell death.

ARPE-19 cells were transiently transfected with the human wild-type NQO-1 expression plasmid pcDNA-hNQO-1 (NQO-1) or empty control plasmid pcDNA3 (CMV3). (A) Cell survival of NQO-1-overexpressing ARPE-19 cells. The day after transfection, the cells were exposed to t-BOOH for 24 hours and cell viability was determined by a modified version of the MTT assay. The results are mean ± SE of triplicates (*p < 0.05) and are a representative experiment from a set of five independent studies. (B) Immunoblot detection of NQO-1 expression plasmid. Twenty-four hours following transfection, ARPE-19 cells were harvested and cell lysates were prepared for determining NQO-1 and β-actin expression by immunoblotting.

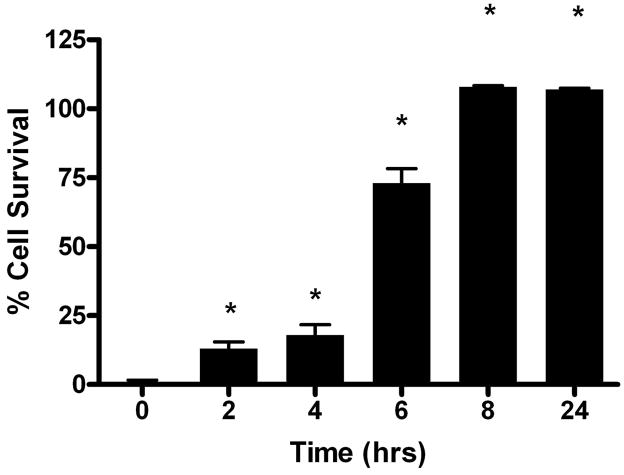

Eriodictyol enhances longterm resistance to oxidative stress-induced cell death

Since eriodictyol induces the expression of HO-1 and NQO-1, and these proteins enhance cellular resistance to oxidative stress, we reasoned that we should be able to demonstrate a correlation between HO-1 and NQO-1 expression and enhanced cell survival in oxidative stress-induced cell death assays.

We treated ARPE-19 cells with eriodictyol for times that were sufficient to induce phase II protein expression and looked at the effect on cell survival. We used progressively higher levels of t-BOOH in dose response studies until we found a concentration that surpassed the ability of eriodictyol to protect the cells in short-term protection studies. With this concentration of t-BOOH as our starting point, we exposed ARPE-19 cells to eriodictyol for times that were sufficient to induce phase II proteins and determined what effect this treatment had on cell survival. We found that pretreating ARPE19 cells with eriodictyol led to a significant increase in cell survival (Figure 5) - a response that was consistent with the time frame of phase II protein expression (Figure 2). The cell survival approached 100% with pretreatment times of 8 hours or more.

Figure 5. Long-term protection from eriodictyol in oxidative stress-induced cell death assays.

ARPE-19 cells were pretreated with and without 50 μM eriodictyol for various times (0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 24 hours) to initiate phase II protein expression before t-BOOH was added to the cells. All cells were maintained in culture for the same time period. The following day, cell viability was determined by a modified version of the MTT assay21. Figure 5 shows a representative experiment from a set of four independent studies of the time course of cell survival with eriodictyol pretreatment. The results are mean ± SD (*p < 0.05). Controls, consisting of cells exposed to no eriodictyol, had a cell survival of 0%.

To further validate the idea that the long-term protection by eriodictyol is not due to the direct antioxidant activity of eriodictyol, we performed mass spectrometry using LC-MS to determine the stability of eriodictyol in tissue culture media after an overnight incubation. We found that >90% of eriodictyol is lost from the culture media after an overnight incubation (results not shown); supporting the idea that the long-term protective effect of eriodictyol is a secondary phenomenon.

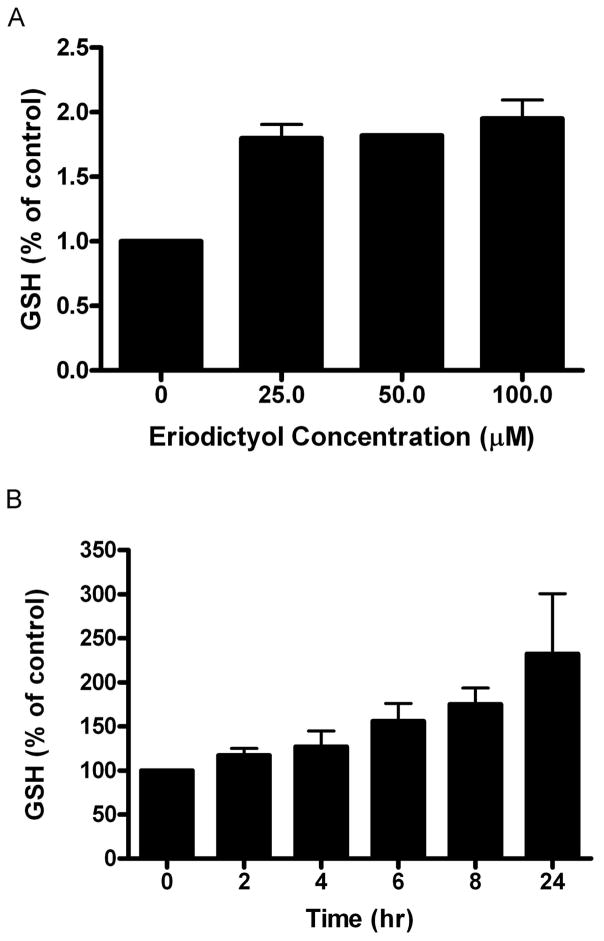

Eriodictyol induces glutathione synthesis

The binding of Nrf2 to the ARE leads to a coordinated induction of multiple phase II proteins, including both subunits of glutamine cysteine ligase, the rate-limiting enzyme for glutathione biosynthesis. We reasoned that treatment with eriodictyol should lead to an increase in glutathione synthesis in ARPE19 cells. To test this hypothesis, we measured glutathione levels in ARPE-19 cells after an extended incubation with eriodictyol. We found that the amount of total glutathione increases by almost 100% compared to untreated cells (Figure 6A). The increase in total glutathione levels (Figure 6B) correlates temporally with the time course of long-term protection from eriodictyol (Figure 5). However, the increased protection that was demonstrated in the dose response study with eriodictyol cannot be attributed to glutathione since the responses of total glutathione to 25, 50 and 100 μM eriodictyol were almost identical (Fig. 6A). Thus, our data support possible roles for both glutathione-dependent and independent pathways in the mechanisms underlying eriodictyol-induced protection.

Figure 6. Eriodictyol increases total GSH levels.

(A) Total GSH levels following eriodictyol treatment; dose response. ARPE-19 cells in 6-well dishes were treated with 25, 50 and 100 μM eriodictyol for 24 hours. The following day the cells were harvested and deproteinated cell lysates were assayed for total GSH as described in the Methods section. The results are an average of seven independent experiments (± SE). (B) Total GSH levels following eriodictyol treatment; time course study. ARPE-19 cells in 6-well dishes were treated with 50 μM eriodictyol for 0–24 hours. At the end of the last time point all cells were harvested and the deproteinated cell lysates were assayed for total GSH as described in the Methods section. The results are mean ± SE of three independent experiments. Untreated cells were designated as 100% control.

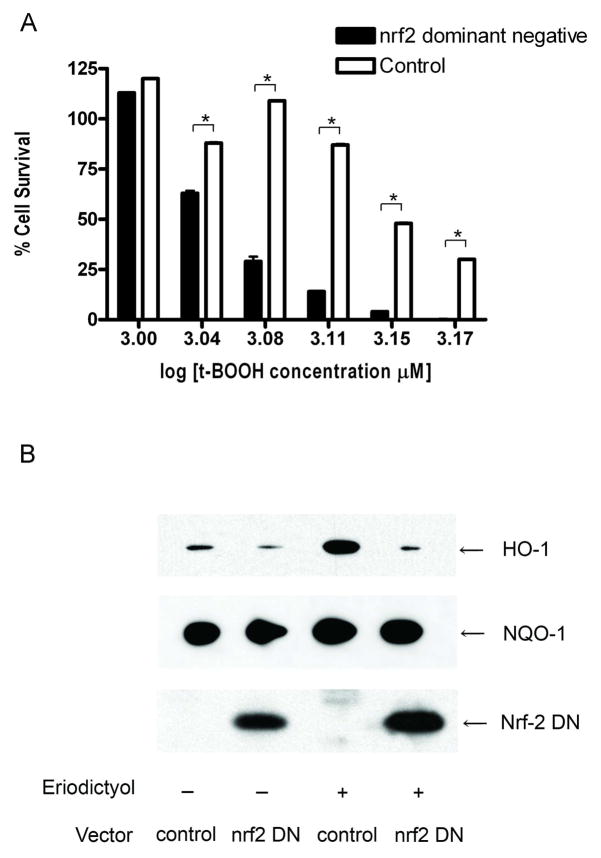

A dominant negative Nrf2 reduces the long-term cytoprotective effect of eriodictyol in ARPE-19 cells

To provide additional support for the hypothesis that the mechanism of cytoprotection that is observed with long-term eriodictyol treatment is a consequence of the activation of Nrf2, we transfected cells with a dominant negative to Nrf2, to determine if it could reduce the cytoprotective effect that is observed following long-term eriodictyol treatment. The RPE cells were transfected with either Nrf2M or the empty vector pEF for 24 hours, and then treated with eriodictyol for another 24 hours. We found that transfection with Nrf2M significantly reduced the survival of eriodictyol-treated cells, as compared to the survival of control cells transfected with pEF and treated with eriodictyol (Figure 7A). Western blot analyses show that HO-1 expression is strongly downregulated in response to the Nrf2 dominant negative (Figure 7B). However, the expression of NQO-1 was less sensitive to Nrf2M expression and was unaffected by the expression of the dominant negative Nrf2 expression vector. These results, together with those showing that Nrf2 upregulation precedes the increase in HO-1 expression but correlates to a lesser extent with NQO-1 expression, suggest that the Nrf2-initiated protective effect is mediated more by upregulation of HO-1 expression than NQO-1 expression. On the other hand, we cannot rule out a possible role of Nrf2 on NQO-1 posttranslational modifications that favor the protective mechanism.

Figure 7. Dominant negative Nrf2 blocks the cytoprotection induced by eriodictyol.

ARPE-19 cells were transiently transfected with pEF-Nrf2M expressing dominant-negative Nrf2 or the empty vector, pEF. The following day the cells were treated with 50 μM eriodictyol for 24 hours. (A) Cell survival of Nrf2M-overexpressing ARPE-19 cells. Twenty-four hours after eriodictyol treatment, the cells were exposed to t-BOOH overnight. Cell viability was determined the following day by a modified version of the MTT assay. Similar findings were obtained in five independent experiments. The results are mean ± SE of triplicate (*p < 0.05) and are representative of three independent experiments. At the t-BOOH concentrations used for these studies all cells untreated with eriodictyol had a cell survival of 0%. (B) Immunoblot analysis of HO-1, NQO-1 and Nrf-2M expression in ARPE-19 cells. Twenty-four hours after eriodictyol treatment, the cells were harvested and both nuclear extracts were prepared to examine the expression of dominant negative Nrf2 and cell lysates were prepared to examine the expression of HO-1, NQO-1 and β-actin.

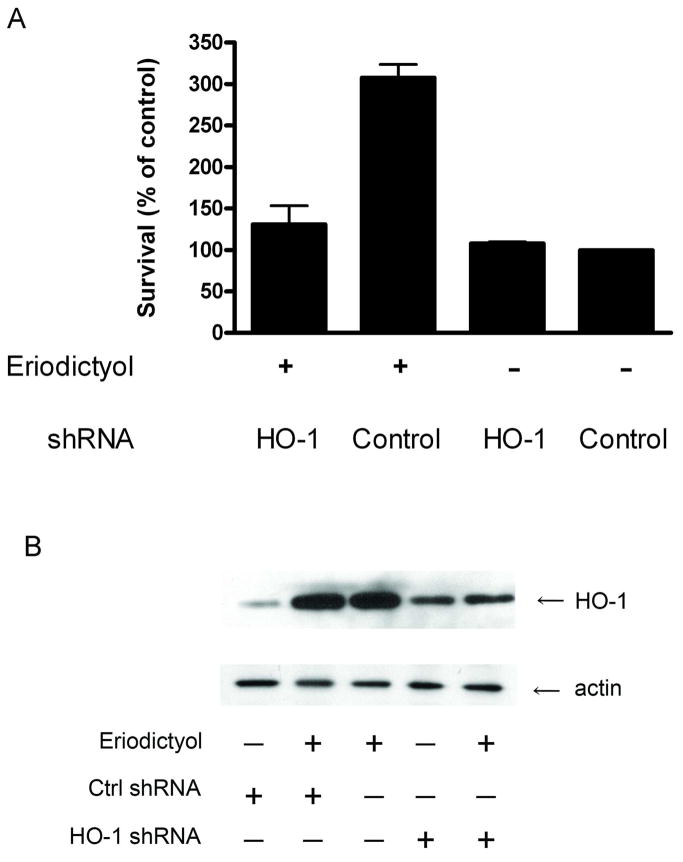

To further analyze the role of HO-1 in the mechanism of eriodictyol-induced cytoprotection, we took a shRNA-targeting approach. In Figure 8A, we show that the downregulation of HO-1 expression significantly reduces the protection effect of eriodictyol on oxidative-mediated damage. A Western blot demonstrating the downregulation of HO-1 in response to eriodictyol is shown in Figure 8B. Overall, these results strongly suggest that HO-1 plays a central role in the mechanism underlying eriodictyol-mediated protection against oxidant-mediated damage in ARPE-19 cells.

Figure 8. Knockdown of heme-oxygenase 1 using a shRNA targeting approach blocks the cytoprotection induced by eriodictyol.

ARPE-19 cells were transiently transfected with a shRNA HO-1 expression plasmid or the scrambled control vector, shRNA control. (A) Cell survival of HO-1 and control shRNA-expressing ARPE-19 cells. The day after transfection, the cells were treated with 50 μM eriodictyol for 24 hours and then exposed to t-BOOH overnight. Cell viability was determined the following day by a modified version of the MTT assay. The results are mean ± SE and are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Immunoblot analysis of HO-1 and actin expression in ARPE-19 cells transfected with HO-1 shRNA and control shRNA. The day after transfection, the cells were treated with 50 μM eriodictyol for 24 hours and lysates were prepared to examine the expression of HO-1 and β-actin.

Discussion

Enhancing the cellular defenses that protect the retina and RPE against oxidative stress has been shown to be a valuable approach to reducing the progression of macular degeneration in patients with moderate to late stages of the condition 1. In previous studies, we showed that short-term exposure to flavonoids protects RPE cells, retinal ganglion cells and other CNS neurons from oxidative stress-induced death 21, 24, 25. In this paper, we focused on the ability of the flavonoid, eriodictyol, to modulate the activation of Nrf2 and the expression of phase II proteins, which are recognized as one of the most important properties of flavonoids, which likely surpass their benefit as direct antioxidants12. To examine the impact of Nrf2 activation and phase II protein expression on RPE cell survival in the setting of oxidative stress, we exposed RPE cells to eriodictyol for times that were sufficient to induce phase II protein expression, and we examined the long-term survival of ARPE-19 cells over this time frame. We used two prototypical phase II proteins, heme-oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H: quinone reductase (NQO-1) as general markers for phase II protein expression, because they are can be easily detected with specific antibodies and are induced in a coordinated manner with other phase II proteins. We also analyzed GSH levels since the two subunits of glutamate cysteine ligase, the rate limiting enzyme in GSH synthesis, are also phase II proteins. We observed that eriodictyol induces the expression of these phase II proteins in a manner that correlates temporally with increased cell survival in the setting of oxidative stress. One of the major findings in this paper was that long-term treatment with eriodictyol increases the resistance of RPE cells to levels of oxidative stress that are much higher than the cells can resist with short-term (1 – 4 hr) exposure, which is a result of the antioxidant activity of eriodictyol. These results emphasize the benefit of inducing phase II enzymes to combat oxidative stress, as compared to using direct antioxidants that are rapidly consumed and/or have a limited lifespan. In support of this conclusion, we found that simply overexpressing heme-oxygenase-1 and NAD(P)H: quinone reductase increases the resistance of RPE cells to oxidative stress-induced cell death.

In examining the mechanism of action of eriodictyol, we found that Nrf2 plays a central role in the protection of RPE cells from oxidative injury. There is a temporal correlation between the long-term survival of ARPE-19 cells and the time course of eriodictyol treatment, Nrf2 activation, HO-1 and NQO1 expression, and glutathione induction. It is reasonable to consider that the effect of phase II enzymes are additive and the effect of a single one cannot account for the full degree of protection that was achieved. For example, maximal total glutathione levels were observed at concentrations of eriodictyol which were less than what was necessary for maximal protection against oxidative damage, suggesting that glutathione alone is not sufficient to exert complete protection and that other enzymes are involved.

Here we show that expression of a dominant negative Nrf2, which competes with eriodictyol-induced Nrf2 for binding to the ARE, reduces the long-term protection of eriodictyol-treated RPE cells, as would be expected if the mechanism was dependent on Nrf2 activation. Using a similar dominant negative Nrf2 construct, other investigators have demonstrated the importance of Nrf2 expression in the protection of primary cultures of CNS neurons and glia from oxidative stress-induced cell death due to glutamate toxicity 26. A central role for Nrf2 in the regulation of phase II protein expression and protection from oxidative toxicity has also been demonstrated in Nrf2 transcription factor-deficient mice, where a deficiency of phase II proteins leads to increased rates of toxicity and neoplasia27. The evidence linking Nrf2 activation and phase II protein expression with the protection of RPE cells raises the possibility that these proteins might enhance the ability of the RPE and retina to withstand long-term exposure to oxidative stress in situ. Other studies have shown that RPE cells are protected from a variety of oxidative insults in vitro by increasing intracellular glutathione levels or by inducing the phase II proteins glutamate cysteine ligase and glutathione synthetase 28–32. Heme-oxygenase-1, which is present in the macula and peripheral RPE cells of human eyes, is enhanced in the setting of oxidative stress following intense light exposure and is increased in the retinas of patients with neovascular membranes from ARMD 33, 34. HO-1 mRNA levels show a decline in aged eyes but, correlations do not support causality, and it is not known whether these changes in expression have any relevance to the development of age-related diseases 17. The expression of NQO-1, which is present throughout the retina and RPE of normal donor eyes 18, correlates with the survival of RPE cells following oxidative injury in vitro 30, yet the significance of these findings are also not known.

Limited clinical insight into the importance of phase II protein expression can be obtained from epidemiologic studies of diabetic patients with Gilbert’s syndrome, who have elevated levels of circulating bilirubin, a powerful and versatile antioxidant and an end product of heme-oxygenase-1 bioactivity. These patients have a significantly lower adjusted odds ratio for diabetic retinopathy (0.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.2–0.45; p<.001) and other vascular diseases, and lower levels of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers 35. They also have a significantly lower prevalence of ischemic cardiovascular disease, hypertension and cancer (reviewed in 36).

Our results are consistent with reports that the activation of Nrf2 and downstream phase II proteins is associated with neuroprotection in models of retinal degeneration 37, 38. In the tubby (tub/tub) mutant mouse, photoreceptor degeneration is blocked following the activation of Nrf2 and the expression of the phase II protein thioredoxin by the oral agent sulforaphane 37. In a rodent model of light toxicity, neuroprotection is induced by light adaptation through the activation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway and the expression of thioredoxin 38.

The results presented here raise the question of whether the consumption of eriodictyol and/or other bioflavonoids which induce Nrf2 activation and phase II protein expression may, in part, be responsible for some of the ocular benefits associated with specific dietary products identified in epidemiologic studies of macular degeneration 4–6. According to the USDA database, eriodictyol is present in a variety of citrus juices, including lemon juice, orange juice and lime juice. (http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/Flav/flav.html) 2. In a large scale prospective study of diet and macular degeneration, Cho et al. identified fruit consumption as inversely related to the development of advanced neovascular ARMD. Surprisingly, the fruit having the strongest inverse association with neovascular ARMD was the orange. It is interesting to speculate whether eriodictyol was responsible for this effect, especially because eriodictyol is present in oranges and the authors could not attribute this finding to Vitamin C or any other common antioxidants that are present in oranges 5.

Recently, Milbury et al. have demonstrated that anthocyanidins found in bilberry fruit modulate heme oxygenase-1 expression and block increased intracellular ROS levels in response to H2O2 in ARPE19 cells 39. Combined with our study, these findings support the possibility that eriodictyol and/or other flavonoids that induce the activation of Nrf2 and the expression of phase II enzymes may be capable of protecting RPE cells from oxidative injuries and might be beneficial for the treatment of retinal disorders associated with oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Scripps Mericos Fonseca Research Fund at Scripps Memorial Hospital for their ongoing support. We also acknowledge Dr. David Ross (University of Colorado Health Sciences Center) for his gift of the human wild-type NQO-1 expression plasmid (pcDNA-hNQO-1).

Supported by the joint Mericos/Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) Neurobiology & Vision Science Research Program and the NEI Core Grant for Vision Research P30EY012598. TSRI manuscript #19427

Contributor Information

Jennifer Johnson, Department of Molecular and Experimental Medicine, The Scripps Research Institute 10550, N. Torrey Pines Rd., La Jolla, CA 92037, Phone (858) 784-7713, Fax (858) 784-7675, Email: ahanneke@scripps.edu.

Pamela Maher, The Salk Institute, 10010 N. Torrey Pines Rd., La Jolla, CA 92037.

Anne Hanneken, Department of Molecular and Experimental Medicine, The Scripps Research Institute 10550, N. Torrey Pines Rd., La Jolla, CA 92037, Phone (858) 784-7713, Fax (858) 784-7675, Email: ahanneke@scripps.edu.

References

- 1.Age-related Eye Disease Study Research Group (AREDS) A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report No. 11. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1417–36. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods. USDA and the Epidemiology Group, Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging, Frances Stern Nutrition Center, Tufts University School of Nutrition Science & Policy, and Tufts New England Medical Center, Boston, MA; the Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition, General Mills, Minneapolis, MN; and Unilever Bestfoods, North America, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 2003. (Accessed 10/18/04, 2004, at http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/Flav/flav.html.)

- 3.Middleton E, Kandaswami C, Theoharides TC. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: Implications for inflammation, heart disease and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52(4):673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Group EDC-CS. Antioxidant status and neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:104–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090010108035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho E, Seddon JM, Rosner B, Willett WC, Hankinson SE. Prospective study of intake of fruits, vegetables, vitamins, and carotenoids and risk of age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(6):883–92. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obisesan TO, Hirsch R, Kosoko Om, Carlson L, Parrott M. Moderate wine consumption is associated with decreased odds of developing age-related macular degeneration in NHANES-1. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pautler EL, Maga JA, Tengerdy C. A pharmacologically potent natural product in the bovine retina. Exp Eye Res. 1986;42(3):285–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(86)90062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalt W, Blumberg JB, McDonald JE, et al. Identification of anthocyanins in the liver, eye, and brain of blueberry-fed pigs. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(3):705–12. doi: 10.1021/jf071998l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsumoto H, Nakamura Y, Iida H, Ito K, Ohguro H. Comparative assessment of distribution of blackcurrant anthocyanins in rabbit and rat ocular tissues. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(2):348–56. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canter PH, Ernst E. Anthocyanosides of Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry) for night vision--a systematic review of placebo-controlled trials. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(1):38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free radicals in biology and medicine. 3. London: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee-Hilz YY, Boerboom AM, Westphal AH, Berkel WJ, Aarts JM, Rietjens IM. Pro-oxidant activity of flavonoids induces EpRE-mediated gene expression. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19(11):1499–505. doi: 10.1021/tx060157q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB. Regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression mediated by the antioxidant response element. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:233–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talalay P. Chemoprotection against cancer by induction of Phase 2 enzymes. Biofactors. 2000;12:1–4. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520120102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AM. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: from basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86(2):583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross D, Kepa JK, Winski SL, Beall HD, Anwar A, Siegel D. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1): chemoprotection, bioactivation, gene regulation and genetic polymorphisms. Chem Biol Interact. 2000;129(1–2):77–97. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamura N, Ogawa T, Boylan S, Morse LS, Handa JT, Hjelmeland LM. Topographic and age-dependent expression of heme oxygenase-1 and catalase in the human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(5):1562–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schelonka LP, Siegel D, Wilson MW, Meininger A, Ross D. Immunohistochemical localization of NQO1 in epithelial dysplasia and neoplasia and in donor eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(7):1617–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prochaska HJ, De Long MJ, Talalay P. On the mechanisms of induction of cancer-protective enzymes: a unifying proposal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82(23):8232–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prestera T, Holtzclaw WD, Zhang Y, Talalay P. Chemical and molecular regulation of enzymes that detoxify carcinogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:2965–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanneken A, Lin FF, Johnson J, Maher P. Flavonoids protect human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative-stress-induced death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(7):3164–77. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alam J, Stewart D, Touchard C, Boinapally S, Choi AM, Cook JL. Nrf2, a Cap’n’Collar transcription factor, regulates induction of the heme oxygenase-1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(37):26071–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagara Y, Ishige K, Tsai C, Maher P. Tyrpostins protect neuronal cells from oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36204–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maher P, Hanneken A. Flavonoids protect RGC-5 cells from oxidative stress induced death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4796–803. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishige K, Schubert D, Sagara Y. Flavonoids protect neuronal cells from oxidative stress by three distinct mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:433–46. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00498-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shih AY, Johnson DA, Wong G, et al. Coordinate regulation of glutathione biosynthesis and release by Nrf2-expressing glia potently protects neurons from oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2003;23(8):3394–406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03394.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos-Gomez M, Kwak MK, Dolan PM, et al. Sensitivity to carcinogenesis is increased and chemoprotective efficacy of enzyme inducers is lost in nrf2 transcription factor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(6):3410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051618798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sternberg P, Jr, Davidson PC, Jones DP, Hagen TM, Reed RL, Drews-Botsch C. Protection of retinal pigment epithelium from oxidative injury by glutathione and precursors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34(13):3661–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson KC, Carlson J, Newman ML, Sternberg P, Jr, Jones DP, Kavanagh TJ, Diza D, Cai J, Wu M. Effect of dietary inducer dimethylfumarate on glutathione in cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1927–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao X, Albena T, Dinkova-Kostova, Talalay P. Powerful and prolonged protection of human retinal pigment epithelial cells, keratinocytes, and mouse leukemia cells against oxidative damage: The indirect antioxidant effects of sulforaphane. PNAS. 2001;98(26):15221–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261572998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao X, Talalay P. Induction of phase 2 genes by sulforaphane protects retinal pigment epithelial cells against photooxidative damage. PNAS. 2004;101(28):10446–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403886101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson KD, Armstrong JS, Moriarty S, Cai J, Wu M-WH, Sternberg P, Jr, Jones DP. Protection of retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative damage by oltipraz, a cancer chemopreventive agent Invest Ophthalmol. Vis Sci. 2002;43:3550–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutty RK, Kutty G, Wiggert B, Chader GJ, Darrow RM, Organisciak DT. Induction of heme oxygenase 1 in the retina by intense visible light: suppression by the antioxidant dimethylthiourea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(4):1177–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.4.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank RN, Amin RH, Puklin JE. Antioxidant enzymes in the macular retinal pigment epithelium of eyes with neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127(6):694–709. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inoguchi T, Sasaki S, Kobayashi K, Takayanagi R, Yamada T. Relationship between Gilbert syndrome and prevalence of vascular complications in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2007;298(12):1398–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1398-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCarty MF. “Iatrogenic Gilbert syndrome”--a strategy for reducing vascular and cancer risk by increasing plasma unconjugated bilirubin. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(5):974–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong L, Tanito M, Huang Z, et al. Delay of photoreceptor degeneration in tubby mouse by sulforaphane. J Neurochem. 2007;101(4):1041–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanito M, Agbaga MP, Anderson RE. Upregulation of thioredoxin system via Nrf2-antioxidant responsive element pathway in adaptive-retinal neuroprotection in vivo and in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42(12):1838–50. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milbury PE, Graf B, Curran-Celentano JM, Blumberg JB. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) anthocyanins modulate heme oxygenase-1 and glutathione S-transferase-pi expression in ARPE-19 cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(5):2343–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]