Abstract

An association between enrichment and depletion of microRNA (miRNA) binding sites, 3′ UTR length, and mRNA expression has been demonstrated in various developing tissues and tissues from different mature organs; but functional, context-dependent miRNA regulations have yet to be elucidated. Towards that goal, we examined miRNA–mRNA interactions by measuring miRNA and mRNA in the same tissue during development and also in malignant conditions. We identified significant miRNA-mediated biological process categories in developing mouse cerebellum and lung using non-targeted mRNA expression as the negative control. Although miRNAs in general suppress target mRNA messages, many predicted miRNA targets demonstrate a significantly higher level of co-expression than non-target genes in developing cerebellum. This phenomenon is tissue specific since it is not observed in developing lungs. Comparison of mouse cerebellar development and medulloblastoma demonstrates a shared miRNA–mRNA co-expression program for brain-specific neurologic processes such as synaptic transmission and exocytosis, in which miRNA target expression increases with the accumulation of multiple miRNAs in developing cerebellum and decreases with the loss of these miRNAs in brain tumors. These findings demonstrate the context-dependence of miRNA–mRNA co-expression.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are short (∼22 nt), single-stranded non-coding RNAs that regulate mRNA gene expression at multiple levels [1]–[6]. The importance of these micro-regulators is evidenced by the increasing number of miRNAs that have been identified; up to 1/3 of human genes are estimated to be miRNA targets. Detailed studies of the expression of both individual miRNAs [7]–[14] and large sets of miRNAs [2], [15]–[16] indicate that, in general, miRNAs suppress mRNA messages. In studies of the expression of large miRNA sets, enrichment or depletion of miRNA binding sites and 3′ UTR length have been evaluated with respect to gene expression in various tissues and during development. Farh et al. reported miRNA-induced repression of mRNA in myoblast differentiation and tissue-specific signatures based on comparisons of conserved and non-conserved sites [2]. Stark et al. reported depletion of miRNA binding sites on genes involved in basic cellular processes [16]. For several miRNAs, co-expressed genes avoid miRNA binding sites while target genes and miRNAs are preferentially expressed in neighboring tissues during Drosophila embryonic development. Both Stark et al. and Sood et al. reported a bias of a longer 3′ UTR length and more miRNA binding sites in genes involved in neurogenesis and in genes highly expressed in neuronal tissues [15]–[16].

Although there are tissue-specific signatures of miRNA repression or miRNA–mRNA mutual-exclusiveness for several highly expressed miRNAs, the pattern of miRNA target gene expression is complicated, especially in the central nervous system (CNS) [2], [15]–[16]. We examined miRNA–mRNA interactions by studying large numbers of miRNAs and the expression of their predicted mRNA targets during the same developmental stages in mouse cerebellum as studied in previous reports for the following reasons. First, we wished to capture more than the dependencies/effects of highly expressed miRNAs. Second, the results of biochemical studies indicate that miRNA repression of mRNA is dependent on the specific cellular conditions [17], hence both tissue-specific and temporal-specific studies are needed to define each condition. Third, the extensive transcriptional program of development is well suited for identifying dynamic miRNA/mRNA interactions in vivo.

To understand the functional roles of miRNAs during development, we assigned their respective target genes to ontological groups based on Gene Ontology (GO), as described in Sood et al.[15]. For consistency, in this manuscript we used the term “target” for any predicted mRNA gene of some known miRNA, accordingly “non-target” is used for the complement of predicted targets. For each miRNA, we identified the statistically significant GO terms among the miRNA's computationally predicted mRNA “target set” that were differentiated from the non-target genes that had positive-correlated developmental profile to the target set. This comparison with non-target genes was performed because the use of non-target genes as a negative control might allow for better recognition of miRNA-mediated features and minimizes the influence of cell type. We defined a developmentally coherent target [coherent target] of a miRNA as a predicted target whose expression negatively correlated with the miRNA. The assumption here is that miRNAs primarily act as suppressors of mRNA during development. Accordingly, a developmentally non-coherent target [non-coherent target] was defined as one whose gene expression was not altered in response to the suppressive function of the miRNA in developing cerebellum. This notion of a non-coherent target is unrelated to Stark's notion of a depletion of miRNA binding sites on mRNA that are co-expressed in a given tissue with an miRNA. Non-coherent targets may co-express with miRNAs despite their 3′UTRs being enriched for the binding sites of those miRNAs.

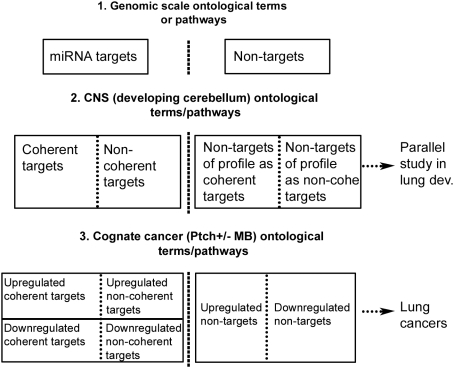

The conservation of mechanisms across development and tumorigenesis and the significant roles of miRNA in both development and tumorigenesis [10], [11], [18]–[22] also motivated our investigation of miRNA–mRNA interactions in both tumors and their cognate developing tissue. Therefore, we intersected the coherent and non-coherent target gene sets observed during cerebellar development with the up- or down-regulated gene sets observed in Ptch+/− medulloblastoma (MB) and compared the logarithmic fold change of expression in tumor with that of the up- or down-regulated non-target genes. As a tissue-specificity control, functional gene sets in murine lung development and lung cancers were studied in parallel. The design of this tissue-specific and temporal-specific functional study of miRNA–mRNA target interaction across development and tumorigenesis is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Design flow of the functional tissue-specific study of miRNA–mRNA interactions in development and malignancy.

Results

The number of miRNA non-coherent targets is equivalent to that of miRNA coherent targets in developing cerebellum and lung tissue

We focused on postnatal days 7 (P7) and P60 for cerebellar development, because the highest level of granule neuron precursor proliferation and migration occurs during P7 and the development of mouse Ptch+/− MB is most closely associated with stage P7 [20], whereas P60 is an adult stage during which miRNA levels are assumed to be stable. Using customized RAKE miRNA microchips [23], we profiled wild-type mouse miRNA expression in developing cerebellum at postnatal stages P7 and P60 (Table 1 and Figure S1). In parallel, we studied the miRNA expression in developing lung at stages P1 and P14, as described in Williams et al. [24]. We have previously reported on total RNA expression in developing mouse cerebellum for P1, P3, P5, P7, P10, P15, P21, P30, P50, and P60 based on the Affymetrix Mu11K arrays [25]. A complete time series of mRNA expression, (also Mu11K arrays), of perfused whole wild-type mouse lung for embryonic days 12, 14, 16, and 18, and postnatal days P1, P4, P7, P10, P14, and P21, covering the five main stages of mouse lung development [26] was also available [27].

Table 1. miRNA expression data of developing mouse cerebellum.

| miRNA Name | pval (Day 7B vs Day 60C) ranked data | Data P7 | Data P60 | Log2 FC | Num of coherent gns (Seri. A) using TargetScanS | Num of Non-coherent gns (Seri. A) using TargetScanS | Num of coherent gns (Seri. A) using PITA | Num of Non-coherent gns (Seri. A) using PITA | Num of coherent gns (Seri. A) using picTar | Num of Non-coherent gns (Seri. A) using picTar |

| mmu-let-7a | 0.89827 | 65423 | 65481 | 0.0012784 | 110 | 99 | 97 | 87 | 109 | 95 |

| mmu-mir-124a | 0.0021645 | 22091 | 65482 | 1.5676397 | 274 | 249 | 201 | 165 | 163 | 127 |

| mmu-mir-125a | 0.064935 | 8299 | 56964 | 2.779041 | 87 | 85 | 141 | 132 | 88 | 78 |

| mmu-mir-103-1,2 | 0.39394 | 4940 | 15020 | 1.6043019 | 68 | 84 | 77 | 80 | 113 | 154 |

| mmu-mir-9 | 0.004329 | 1354 | 3855 | 1.5095031 | 162 | 177 | 153 | 125 | 139 | 157 |

| mmu-mir-23b | 0.0021645 | 1262 | 5891 | 2.2228006 | 123 | 126 | 161 | 131 | 78 | 82 |

| mmu-mir-206 | 0.0021645 | 1083 | 3019 | 1.4790375 | 121 | 116 | 93 | 90 | 111 | 104 |

| mmu-mir-15 | 0.0021645 | 680 | 1402 | 1.0438797 | 122 | 151 | 164 | 191 | 120 | 152 |

| mmu-mir-30b | 0.0021645 | 590 | 21826 | 5.209189 | 191 | 162 | 188 | 164 | 122 | 100 |

| mmu-mir-99b | 0.015152 | 450 | 5933 | 3.7207649 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| mmu-mir-221 | 0.0021645 | 426 | 3083 | 2.8554096 | 60 | 43 | 61 | 69 | 50 | 49 |

| mmu-mir-187 | 0.39394 | 399 | 1002 | 1.3284219 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 3 |

| mmu-mir-138 | 0.0021645 | 372 | 854 | 1.1989334 | 58 | 60 | 71 | 66 | 56 | 50 |

| mmu-mir-194 | 0.0021645 | 309 | 4231 | 3.7753199 | 55 | 48 | 52 | 54 | 37 | 41 |

| mmu-mir-133 | 0.0021645 | 287 | 1585 | 2.4653602 | 72 | 69 | 67 | 62 | 66 | 68 |

| mmu-mir-21 | 0.0021645 | 275 | 1555 | 2.4994111 | 34 | 29 | 59 | 47 | 37 | 26 |

| mmu-mir-204 | 0.0021645 | 266 | 4643 | 4.1255591 | 70 | 63 | 86 | 91 | 71 | 63 |

| mmu-mir-34a | 0.0021645 | 155 | 1873 | 3.5950108 | 86 | 75 | 86 | 85 | 81 | 77 |

| mmu-mir-152 | 0.0021645 | 102 | 313 | 1.6175935 | 74 | 102 | 109 | 117 | 65 | 92 |

| mmu-mir-218-1,2 | 0.0021645 | 93 | 2281 | 4.6162919 | 79 | 111 | 111 | 113 | 77 | 100 |

| mmu-mir-182 | 0.0021645 | 86 | 424 | 2.3016557 | 114 | 115 | 119 | 99 | 130 | 134 |

| mmu-mir-146 | 0.0021645 | 85 | 238 | 1.4854268 | 29 | 22 | 39 | 32 | 23 | 22 |

| mmu-mir-7 | 0.0021645 | 38 | 214 | 2.4935395 | 54 | 54 | 57 | 55 | 53 | 55 |

| mmu-mir-101 | 0.0021645 | 34 | 70 | 1.0418202 | 53 | 55 | 89 | 90 | 94 | 104 |

| mmu-mir-139 | 0.0021645 | 33 | 51 | 0.6280312 | 58 | 54 | 78 | 104 | 54 | 49 |

| mmu-mir-223 | 0.0021645 | 32 | 98 | 1.6147098 | 45 | 34 | 42 | 51 | 35 | 33 |

| mmu-mir-137 | 0.0021645 | 24 | 34 | 0.5025003 | 85 | 80 | 105 | 121 | 72 | 67 |

| mmu-mir-96 | 0.0021645 | 23 | 50 | 1.1202942 | 64 | 55 | 87 | 70 | 133 | 138 |

| mmu-mir-128 | 0.0021645 | 7840 | 53416 | 2.7683464 | 98 | 96 | 140 | 126 | 114 | 120 |

| mmu-mir-26a | 0.0021645 | 4037 | 65474 | 4.0195666 | 134 | 89 | 113 | 81 | 101 | 69 |

| mmu-mir-22 | 0.0021645 | 1411 | 11129 | 2.9795341 | 60 | 68 | 74 | 72 | 64 | 65 |

| mmu-mir-145 | 0.0021645 | 730 | 2578 | 1.8202839 | 93 | 65 | 87 | 86 | 51 | 41 |

| mmu-mir-143 | 0.0021645 | 217 | 1033 | 2.2510733 | 51 | 40 | 65 | 38 | 45 | 38 |

| mmu-mir-27b | 0.0021645 | 125 | 907 | 2.8591745 | 103 | 100 | 152 | 157 | 136 | 144 |

| mmu-mir-192 | 0.0021645 | 86 | 579 | 2.7511548 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 27 | 21 | 17 |

| mmu-mir-140 | 0.0021645 | 39 | 41 | 0.0721498 | 38 | 33 | 61 | 57 | 42 | 42 |

| mmu-mir-216 | 0.0021645 | 1135 | 24 | −5.5635141 | 27 | 23 | 68 | 68 | 23 | 20 |

| mmu-mir-375 | 0.1 | 36 | 8 | −2.169925 | 42 | 45 | 7 | 10 | 24 | 27 |

| mmu-mir-144 | 0.93723 | 24 | 9 | −1.4150375 | 21 | 21 | 112 | 122 | 98 | 108 |

| mmu-mir-181a | 0.0021645 | 32848 | 27769 | −0.2423303 | 125 | 130 | 137 | 168 | 86 | 93 |

| mmu-mir-93 | 0.0021645 | 15075 | 1561 | −3.2716156 | 72 | 71 | 159 | 151 | 136 | 129 |

| mmu-mir-130 | 0.0021645 | 12033 | 3819 | −1.6557295 | 99 | 73 | 135 | 103 | 120 | 87 |

| mmu-mir-92-1,2 | 0.0021645 | 11935 | 364 | −5.0351163 | 128 | 102 | 97 | 86 | 92 | 62 |

| mmu-mir-106 | 0.0021645 | 3563 | 234 | −3.928512 | 156 | 120 | 159 | 146 | 135 | 107 |

| mmu-mir-217 | 0.0021645 | 450 | 18 | −4.6438562 | 28 | 44 | 69 | 74 | 31 | 37 |

| mmu-mir-122a | 0.0021645 | 270 | 49 | −2.4621058 | 33 | 27 | 26 | 30 | 30 | 25 |

| mmu-mir-155 | 0.0021645 | 214 | 54 | −1.9865795 | 37 | 59 | 56 | 64 | 33 | 47 |

| mmu-mir-184 | 0.041126 | 88 | 64 | −0.4594316 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| mmu-mir-199a-1 | 0.17965 | 86 | 7 | −3.6189098 | 56 | 54 | 128 | 143 | 36 | 51 |

| mmu-mir-19a | 0.0021645 | 56 | 10 | −2.4854268 | 125 | 124 | 154 | 142 | 131 | 120 |

| mmu-mir-33 | 0.39394 | 45 | 23 | −0.9682911 | 52 | 34 | 57 | 55 | 43 | 33 |

| mmu-mir-142-s | 0.13203 | 44 | 8 | −2.4594316 | 40 | 37 | 41 | 58 | 40 | 33 |

| mmu-mir-219 | 0.24026 | 40 | 23 | −0.7983661 | 43 | 45 | 36 | 31 | 34 | 38 |

| mmu-mir-153 | 0.17965 | 29 | 19 | −0.6100535 | 75 | 81 | 68 | 89 | 72 | 74 |

pval — the Wilcoxon ranksum test result comparing P7 and P60 ranked sorted miRNA expression;

Log2FC — the logarithmic fold change between P60 and P7 miRNA expression.

TargetScanS [28] computational prediction of targets for 54 conserved miRNAs in developing cerebellum and 59 miRNAs in developing lung was performed. For each miRNA, we identified the coherent target and non-coherent target sets using the P7 and P60 data points in developing cerebellum and likewise we did the test using the P1 and P14 data points in developing lung. Positive correlation between miRNA and mRNA target is considered non-coherent and accordingly negative correlation is considered coherent. In both developing cerebellum and lung, the number of non-coherent targets was equivalent to that of coherent targets for each miRNA, regardless of its level of expression (Table 1 and Table S1). The mean number of coherent targets per miRNA was 76 in developing cerebellum and 66 in developing lung, and the number of non-coherent targets was 72 and 69, respectively.

We performed the same procedure using PITA[29] and picTar[30] target predictions and found similar phenomenon in each case, (the right two columns of Table 1 and Table S1). Likewise, in the following findings we conducted the tests with PITA and picTar predictions as well in addition to TargetScans in order to exclude algorithm-specific artifact. Results of the comparisons are demonstrated in each place where such a purpose is addressed.

miRNAs can be classified according to the coherence and non-coherence of their target sets in developing cerebellum

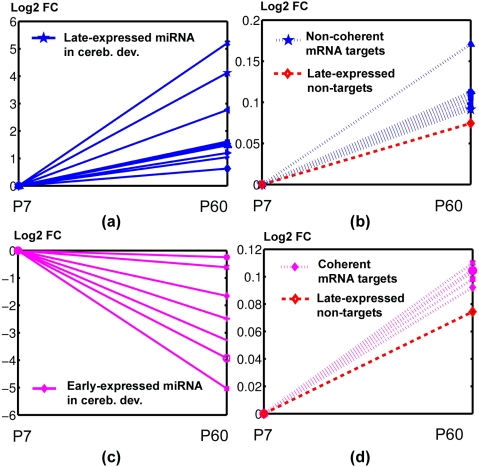

We next examined whether miRNAs can be classified according to the coherence and non-coherence of their targets during development given that we found non-coherent targets to be as common as coherent ones. Using non-target genes as a negative control, we compared the changes in mRNA expression of coherent targets or non-coherent targets for each miRNA with those of changes in the expression of non-target genes that had a positively correlated developmental profile to the target set in test. We then computed the statistic of the tests to identify which miRNAs are significant when their coherent targets are compared with the non-target control set and which are significant when tested for their non-coherent targets. In conjunction with the two types of miRNAs (developmentally early expressed/early-expressed miRNAs and developmentally late expressed/late-expressed miRNAs), there shall be four types of test in all. The tests revealed two significant (Wilcoxon ranksum test p<0.05) miRNA expression patterns during development as demonstrated in Figure 2. The average logarithmic relative expression of miRNA targets at day P60 compared to that of P7 was plotted against that of the corresponding background non-target genes. We use “LNCoh” to denote late-expressed miRNAs significant for their non-coherent targets (Figure 2A shows for the miRNAs, Figure 2B for the corresponding mRNA non-coherent targets), and “ECoh” to denote early-expressed miRNAs significant for their coherent targets (Figure 2C for the miRs, Figure 2D for the corresponding mRNA coherent targets).

Figure 2. Significant opposite effects of the miRNAs on the coherent and non-coherent target genes in developing cerebellum.

(A) Late expressed miRNAs in Table 2. (B) Non-coherent mRNA targets of late expressed miRNAs. (C) Early expressed miRNAs in Table 2. (D) Coherent mRNA targets of early expressed miRNAs. Dashed line represents average of the non-target genes that expressed late in developing cerebellum.

The graphs in Figure 2 illustrate the opposite effects of the miRNAs on the coherent and non-coherent genes. In the developing cerebellum, 12 of the 36 late-expressed miRNAs were LNCoh and 7 of the 18 early-expressed miRNAs were ECoh (Table 2). Using the prediction by PITA and picTar, we identified a similar set of significant miRNAs. In the case of using PITA prediction, 22 of 36 late-expressed miRNAs were LNCoh-type while 10 of the 18 early-expressed miRNAs wer ECoh-type (Table S2). With picTar prediction, 13 of the late miRNAs were LNCoh-type and 9 of the 18 early miRNAs were ECoh-type (Table S3). Both non-coherent targets for early expressed miRNAs and coherent targets for late expressed miRNAs are not statistically significant compared with the corresponding non-target background gene set. It is noteworthy that as the miRNA expression decreases, the upregulation of coherent targets of the ECoh-type miRNAs is significantly greater than that of the non-target genes and, more surprisingly, the non-coherent targets of the LNCoh-type miRNAs escape even further from miRNA suppression than non-target genes.

Table 2. Significant miRNAs in mouse cerebellum development.

| Significant miRNAs in cerebellum dev. for their non-coherent targets | ||||||

| miRNA Name | Dev Status | Num and % of non-coherent genes | Log2 (P60/P7) of the miR | Ave. Log FC offset | P-val (a) | P-val (b) |

| hsa-mir-15 | Late | 151/55.31% | 1.044 | 0.029 | 0.0001 | 7.03E-05 |

| mmu-mir-124a | Late | 249/47.61% | 1.568 | 0.018 | 0.0017 | 0.0010 |

| mmu-mir-152 | Late | 102/57.95% | 1.618 | 0.031 | 0.0020 | 0.0005 |

| hsa-mir-9 | Late | 177/52.21 | 1.510 | 0.022 | 0.0020 | 0.0002 |

| mmu-mir-30b | Late | 162/45.89% | 5.209 | 0.019 | 0.0028 | 0.0099 |

| hsa-mir-103-1,2 | Late | 84/55.26% | 1.604 | 0.031 | 0.0030 | 0.0002 |

| hsa-mir-139 | Late | 54/48.21% | 0.628 | 0.039 | 0.0045 | 0.0004 |

| mmu-mir-146 | Late | 22/43.14% | 1.485 | 0.096 | 0.0063 | 0.0465 |

| mmu-mir-206 | Late | 116/48.95% | 1.479 | 0.035 | 0.0121 | 0.0015 |

| mmu-mir-138 | Late | 60/50.85% | 1.199 | 0.036 | 0.0174 | 0.0108 |

| mmu-mir-128 | Late | 96/49.48% | 2.768 | 0.024 | 0.0218 | 0.0161 |

| mmu-mir-204 | Late | 63/47.37% | 4.126 | 0.017 | 0.0296 | 0.0211 |

Ave. LogFC Val offset — average offset of the logarithmic fold change (P60/P7 in dev.) calculated for the involved miRNA non-coherent/coherent targets from that of non-miRNA target genes;

P-val (a) —the p-vals calculated for the involved miRNA using the logFC of non-coherent targets/coherent targets vs. non-miRNA-target gene background;

P-val (b) (the p-vals calculated from duplicate dev data).

Interestingly, both miR-124 (a highly brain-specific miRNA) and miR-9 (a highly functional miRNA in brain development) are expressed late in development and are significant when their non-coherent targets are compared with the non-target control gene set. In comparison, there are far fewer significant miRNAs either for the non-coherence or for the coherence of their targets in the developing lung, where there is no apparent bias towards a particular category (Table S4). These results suggest that many late-expressed miRNAs mediate target non-coherence in a tissue-specific and functional manner.

Non-coherent target sets of late-expressed miRNAs correspond significantly with processes involving cell-communication among which synaptic transmission and others co-express multiple miRNAs at a significantly higher level than do non-targets

Based on the finding that late miRNAs are characterized by the non-coherence of their targets, we examined the ontological correlates of the target sets. Among the non-coherent targets of the late-expressed miRNAs, GO terms such as cell-communication, signal transducer activity, cell differentiation, and morphogenesis were enriched with the non-target background as control. Table 3 summarizes the enriched GO terms of miRNA coherent/non-coherent targets in developing cerebellum. We further investigated whether the non-coherent targets associated with these terms were still significantly enriched against the non-targets associated with the same terms that positively correlate with the non-coherent targets and found cell-communication and cell differentiation were again significant (Table S5). The test statistic is the logarithmic fold-change of the expression in developing cerebellum as in previous tests. This finding is important in that although the miRNA binding sites for mRNA genes of these GO terms are enriched on a genome scale [16], these functional processes are non-coherent to miRNA suppression.

Table 3. The enriched Gene Ontological terms composed of miRNA non-coherent/coherent targets in cerebellum development.

| Gene Ontological terms | p-val | LogFC Val offset | miRNAs | ||||||||||||

| Non-coherent terms | sort by multiplicity of miRs | ‘transmission of nerve impulse’ | 0.0046 | 0.1596 | mir-128 | mir-137 | mir-218 | mir-27b | mir-143 | mir-133 | mir-206 | mir-152 | let-7a | mir-9 | mir-138 |

| ‘synaptic transmission’ | 0.0046 | 0.1596 | mir-128 | mir-137 | mir-218 | mir-27b | mir-143 | mir-133 | mir-206 | mir-152 | let-7a | mir-9 | mir-138 | ||

| ‘transport’ | 0.0028 | 0.0852 | mir-103 | mir-128 | mir-218 | mir-23b | mir-101 | mir-21 | mir-15 | mir-138 | |||||

| ‘localization’ | 0.0017 | 0.0749 | mir-103 | mir-128 | mir-139 | mir-218 | mir-23b | mir-21 | mir-15 | mir-138 | |||||

| ‘transporter activity’ | 0.0014 | 0.0941 | mir-103 | mir-128 | mir-218 | mir-221 | mir-23b | mir-30b | mir-15 | mir-138 | |||||

| sort by p-vals | ‘cell communication’ | 3.79E-05 | 0.0759 | mir-138 | |||||||||||

| ‘nucleus’ | 0.0001 | 0.0337 | mir-9 | ||||||||||||

| ‘membrane-bound organelle’ | 0.0002 | 0.0325 | mir-9 | ||||||||||||

| ‘cellular process’ | 0.0001 | 0.0337 | mir-15 | ||||||||||||

| ‘intracellular membrane-bound organelle’ | 0.0002 | 0.0324 | mir-9 | ||||||||||||

| sort by offset from non-targets | ‘synapse’ | 0.0047 | 0.3267 | mir-146 | mir-34a | mir-206 | |||||||||

| ‘metal ion-binding site:Calcium 2’ | 0.0048 | 0.2882 | mir-128 | mir-34a | mir-152 | let-7a | |||||||||

| ‘lipid binding’ | 0.0033 | 0.2982 | mir-34a | ||||||||||||

| ‘metal ion-binding site:Calcium 1’ | 0.0048 | 0.2882 | mir-128 | mir-34a | mir-152 | let-7a | |||||||||

| ‘metal ion-binding site:Calcium 1 (via carbonyl oxygen)’ | 0.0052 | 0.2882 | mir-128 | mir-34a | |||||||||||

| Coherent terms | sort by multiplicity of miRs | ‘physiological process’ | 0.0047 | 0.0280 | mir-153 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-93 | mir-142s | mir-92 | mir-106 | ||||

| ‘DNA metabolism’ | 0.0261 | -0.0633 | mir-194 | mir-23b | mir-145 | mir-21 | let-7a | mir-138 | |||||||

| ‘cellular physiological process’ | 0.0033 | 0.0304 | mir-153 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-93 | mir-92 | mir-106 | |||||||

| ‘cellular process’ | 0.0019 | 0.0297 | mir-153 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-93 | mir-92 | mir-106 | |||||||

| ‘metabolism’ | 0.0049 | 0.0242 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-93 | mir-142s | mir-106 | ||||||||

| sort by p-vals | ‘cell’ | 0.0008 | 0.0318 | mir-153 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-106 | ||||||||

| ‘extracellular matrix structural constituent’ | 0.0012 | -0.1722 | let-7a | ||||||||||||

| ‘cellular process’ | 0.0019 | 0.0297 | mir-153 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-93 | mir-92 | mir-106 | |||||||

| ‘HSA04512:ECM-RECEPTOR INTERACTION’ | 0.0024 | -0.1612 | let-7a | ||||||||||||

| ‘binding’ | 0.0032 | 0.0297 | mir-181a | mir-19a | mir-93 | mir-106 | |||||||||

| sort by offset from non-targets | ‘nuclear membrane’ | 0.0225 | -0.2573 | mir-23b | |||||||||||

| ‘HSA04110:CELL CYCLE’ | 0.0212 | -0.2572 | mir-124a | ||||||||||||

| ‘HSA01430:CELL COMMUNICATION’ | 0.0135 | -0.2084 | let-7a | mir-124a | |||||||||||

| ‘coiled coil’ | 0.0125 | -0.1946 | mir-101 | ||||||||||||

| ‘trimer’ | 0.0154 | -0.1917 | let-7a | ||||||||||||

p-val — median of the p-vals calculated for the involved miRNAs using the logFC of non-coherent targets/coherent targets vs. non-miRNA-target gene background;

LogFC Val offset — median of the offset of the logarithmic fold change (P60/P7 in dev.) calculated for the involved miRNAs non-coherent/coherent targets from that of non-miRNA target genes;

# of miRNAs — number of associated miRNA incidences in Dev. (common for two duplicates) with the GO terms.

To determine the extent to which the non-coherent targets for each miRNA in terms of GO terms differ from the non-target genes in developing cerebellum, we investigated the average logarithmic fold-change of mRNA expression from P7 to P60 and compared the result with the value of the corresponding non-target genes that had a positive-correlated developmental profile to the target set. Many enriched GO terms were co-expressed with the late-expressed miRNAs at significantly higher levels than that of non-target genes, with an average fold-change difference of 55%.

We sorted the above obtained GO terms based on their non-coherent targets' offset from non-target background genes in terms of logarithmic fold-change from P7 to P60, their statistical significance in the enrichment test, and their multiplicity of miRNAs, respectively (Table 3). Among the non-coherent ontological gene sets, the terms Metal ion-binding site:Calcium and Synaptic transmission ranked at the top if the three ranks were weighted equally. Having the most number of putative binding miRNAs, Synaptic transmission exhibited a 140% greater fold-change from P7 to P60 compared with the average non-target late-expressed genes (p<0.009). A total of 11 miRNAs, let-7, miR-9, miR-206, miR-138, miR-133, miR-152, miR-137, miR-128, miR-143, miR-27b and miR-218 were co-expressed by 18 synaptic transmission target genes (Table S6).

In order to understand the robustness of the non-coherence of the afore identified pathways in the dynamics of cerebellum development, we computed the differential expression of target genes in the intermediate time points (P10, P15, P21, P30) relative to P7 respectively, versus the miRNA differential expression at P60 relative to P7. A similar list of pathways were found to be significant in developing cerebellum at these 4 stages (Table S7). Moreover, the statistical significances at later stages P21 and P30 are higher than at early stages P10 and P15, which demonstrate progressive nature of developmental non-coherence of mRNA target of late miRNAs.

Synaptic transmission is the essential process of transferring signals between neurons in the CNS [31]. Functioning mainly in chemical synapses, the 18 synaptic transmission genes cover the different stages of both presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotransmission at the synapse. For example, SYT1 and SNAP-25 are presynaptic proteins involved in neurotransmitter release, whereas GABARAPL1 is a postsynaptic receptor. Some synaptic transmission genes, such as RIT2, are exclusively expressed in neurons. We examined whether there is a hierarchical relationship among the enriched GO terms and their relation, if any, to synaptic transmission. We identified two pedigree sub-trees of GO terms that were closely related in the context of the synapse: a cell communication-rooted tree branching to synaptic transmission and a localization-rooted tree branching to exocytosis, which is the process that releases neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft.

We further investigated whether the non-coherent target set of synaptic transmission was significant using the non-target synaptic transmission genes as controls because on average, late-expressed synaptic transmission non-target genes have a higher fold-change from P7 to P60 than do other non-target genes. Again, the non-coherent synaptic transmission genes were significant in this case for each miRNA involved (p<0.05). Moreover, the processes in the two sub-trees of GO terms (mentioned above) are generally among the most significant. Comparison of the non-coherent exocytosis targets with the non-target exocytosis genes revealed a similar phenomenon. This finding suggests the enriched non-coherent GO processes are not isolated events, but rather functionally consistent phenomena mediated by miRNA.

We performed the same statistical test and analysis for the enrichment of non-coherent GO processes using the targets predicted by PITA and picTar. Comparing the results (Table S8, S9) with the findings using TargetScanS prediction, we found that Synaptic transmission again ranked at the top and the related GO processes are included in the list of significant terms. The coherent ontological gene sets are also tested (Table S8, S9) and we found discrepancy in results using different predictors. In particular, the most enriched coherent terms from TargetScanS include basic processes such as Physiological process, cellular process, DNA metabolism and chromatin assembly/disassembly that are not largely represented in PITA and picTar target predictions and thus are not identified as significant ones using the other two predictors.

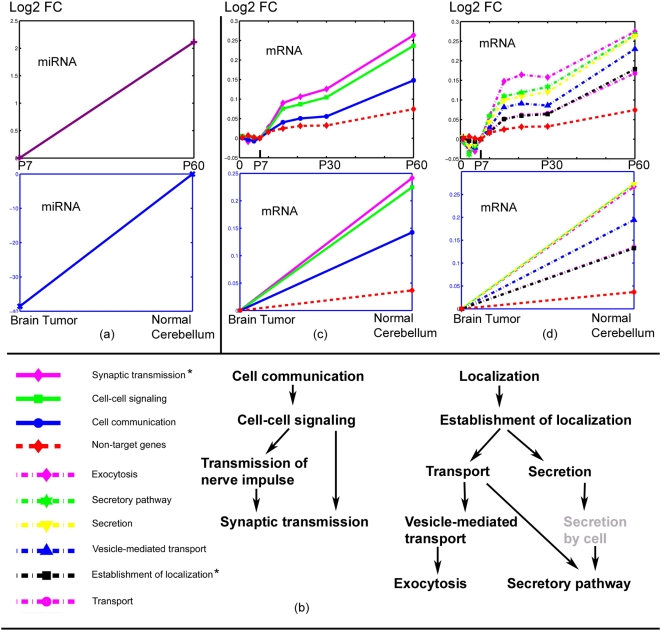

A common miRNA–mRNA co-expression program of non-coherent target sets of GO processes is shared between developing cerebellum and medulloblastoma (MB): example of two sub-trees of GO terms

The functional enrichment of groups of non-coherent ontological target sets reveals a positive output of targets toward the corresponding miRNAs in developing cerebellum. We examined whether mRNA targets avoid miRNA suppression in malignant brain tumors. We identified the intersecting sets of coherent/non-coherent targets in developing cerebellum and the up/down targets in mouse Ptch+/− MB and tested them against the up/down non-target background genes for enriched GO terms (Table S10). All significant non-coherent ontological target sets for late miRNAs were downregulated and all significant coherent ontological target sets for late miRNAs were upregulated in MB.

As in developing cerebellum, the groups of non-coherent GO processes for late-expressed miRNAs, including synaptic transmission, were significantly different from non-target downregulated mRNA in MB (Table 4). Again, the GO processes were composed of two sub-trees (Figure 3B), as in development, for shared miRNAs, such as miR-9, miR-206, miR-138, miR-133, miR-152, and miR-128. Given that Ptch+/− MB is most closely associated with stage P7 [20] in developing cerebellum, we compared the adult normal samples to the Ptch+/− MB and plotted the average logarithmic fold-change of mRNA expression of adult normal tissue over Ptch+/− MB. Figure 3C shows the cell communication-rooted sub-tree branching to the synaptic transmission logarithmic fold-change in both developing tissue and tumor, and Figure 3D shows the fold-change profiles of the localization-rooted sub-tree branching to exocytosis. In both figures, the corresponding non-target genes were used as controls. Interestingly, not only the two sub-trees of GO terms were shared, the magnitudes and orders of the terms in MB and developing cerebellum were similar. As before, we tested the non-coherent synaptic transmission target sets against non-target down-regulated synaptic transmission genes in MB and found the non-coherent miRNA targets were still significant, as were the other GO terms in the two shared sub-trees. The two sub-trees of GO processes are also shared between developing cerebellum and Ptch+/− MB when picTar and PITA predictions are used (Table S11, S12). For synaptic transmission, miR-128, miR-27b, miR-133, miR-206, miR-152 and miR-9 are shared between development and tumor using picTar prediction; miR-128, miR-140, miR-27b, miR-22, miR-133, miR-223 and miR-152 are shared using PITA prediction.

Table 4. The statistic significance and other quantifications of the shared miRNA non-coherent GO terms shared between brain tumor and cerebellum development.

| GO terms | p-val in Dev. | LogFC Val offset in Dev. | # of miRs in Dev. | p-val in MB | LogFC Val offset in MB | # of miRs in MB | # of common genes | significant miRNAs shared btw Ptch+/− MB and development | ||||||

| ‘transmission of nerve impulse’ | 0.0046 | 0.1596 | 11 | 0.0043 | −0.1944 | 8 | 18 | mir-128 | mir-218 | mir-133 | mir-206 | mir-152 | mir-9 | mir-138 |

| ‘synaptic transmission’ | 0.0046 | 0.1596 | 11 | 0.0043 | −0.1944 | 8 | 18 | mir-128 | mir-218 | mir-133 | mir-206 | mir-152 | mir-9 | mir-138 |

| ‘cell communication’ | 0.0000 | 0.0759 | 1 | 0.0029 | −0.0945 | 4 | 19 | mir-138 | ||||||

| ‘transport’ | 0.0028 | 0.0852 | 8 | 0.0008 | −0.1051 | 5 | 21 | mir-128 | mir-218 | mir-138 | ||||

| ‘cell–cell signaling’ | 0.0039 | 0.1265 | 6 | 0.0015 | −0.1964 | 4 | 8 | mir-128 | mir-133 | |||||

| ‘localization’ | 0.0017 | 0.0749 | 8 | 0.0004 | −0.1046 | 4 | 30 | mir-128 | mir-218 | |||||

| ‘establishment of localization’ | 0.0017 | 0.0749 | 8 | 0.0004 | −0.1046 | 4 | 30 | mir-128 | mir-218 | |||||

| ‘secretion’ | 0.0080 | 0.1748 | 3 | 0.0081 | −0.1637 | 2 | 6 | mir-103 | mir-128 | |||||

| ‘exocytosis’ | 0.0018 | 0.2142 | 1 | 0.0010 | −0.2354 | 1 | 4 | mir-128 | ||||||

| ‘vesicle-mediated transport’ | 0.0054 | 0.1456 | 2 | 0.0091 | −0.1637 | 2 | 7 | mir-103 | mir-128 | |||||

| ‘secretory pathway’ | 0.0095 | 0.1825 | 2 | 0.0010 | −0.2354 | 1 | 4 | mir-128 | ||||||

p-val — median of the p-vals calculated for the involved miRNAs using the logFC of non-coherent targets targets vs. non-miRNA-target gene background;

LogFC Val offset — offset of the median of the logarithmic fold change (P60/P7 in dev.) calculated for the involved miRNAs non-coherent targets from that of non-miRNA target genes;

# of miRNAs — number of associated miRNA incidences (common for two duplicates) with the GO terms;

# of common genes — number of common miRNA non-coherent targets shared by developing cerebellum tissue and MB tumor for the associated term.

Figure 3. Common miRNA–mRNA co-expression pattern.

Shared non-coherent ontological gene sets between brain development and tumors (A) average miRNA profiles in developing cerebellum and tumor, (B) legend and the two sub-tree hierarchy of the synaptic transmission-related processes. (C,D) developmental mRNA profiles of the brain-specific neurologic terms that significantly avoid miRNA suppression. * Synaptic transmission and Transmission of nerve impulse share the same set of mRNA target genes; Establishment of localization and Localization share the same set of mRNA target genes.

We then examined the miRNA expression in brain cancers. We obtained CNS cancer cell line miRNAs from the NCI-60 database [32], which were histologically glioblastoma. Glioblastoma is a primary CNS tumor that sometimes occurs in the cerebellum. Compared with normal P60 cerebellum, almost all the late miRNAs in developing cerebellum were downregulated in these CNS tumor cell lines (Figure 3A). All except one of the involved miRNAs for the shared two sub-trees of GO terms were downregulated, and the expression of that one was not changed (Table S13).

In addition, we tested the human MB cell line and found similar sharing of significant non-coherent ontological target sets, including synaptic transmission and exocytosis, between MB and developing cerebellum (Table S10). Tests in developing lung and lung cancers performed in parallel revealed that no significant non-coherent ontological gene sets were shared between them.

Together, these findings indicate that there is common program of process-specific miRNA–mRNA co-expression between developing cerebellum and CNS tumors. In particular, the brain-specific neurologic process synaptic transmission, and two closely related processes, vesicle-mediated transport and exocytosis, significantly avoid regulation by the gain of function of multiple miRNAs in developing cerebellum as well as by the same miRNA's loss of function in brain tumors.

miRNA–mRNA co-expression in brain development and malignancy are tissue-specific

In addition to the fact that fewer miRNAs were found significant for their target's coherence or non-coherence in developing lung than in developing cerebellum (Table S4), there were also very few common significant GO terms in each of the types defined as either early or late and coherent or non-coherent (Table S14).

Between developing cerebellum and lung, only two generic GO terms are common including cellular physiological process and binding (Table S14), while overall there were 164 significant non-coherent ontological gene sets in the cerebellum. Both these two categories are significantly non-coherent to miR-15. Although synaptic transmission target set was also significantly non-coherent in developing lung, it involved only miR-140 and miR-200b, which were different miRNAs from those in developing cerebellum. In developing lung, no group of GO terms was significantly associated with synaptic transmission, in contrast to developing cerebellum. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and MAPK signaling pathway are among the identified lung development-specific non-coherent ontological target sets for miR-140, which is significant in lung development for its target non-coherence (Table S4).

Far fewer significant miRNAs were found in developing lung than in developing cerebellum with picTar and PITA predictions (Table S15). There is one significant miRNA for its non-coherent targets (miR-146) and one for coherent targets (miR-204) in the case of picTar while there are no significant miRNAs when PITA is used. Comparing the enrichment of GO processes between developing lung and cerebellum, we found Metal ion transport and MAPKKK cascade are commonly significantly non-coherent to miR-15 and that Phosphorylation is commonly significantly coherent to miR-181 using picTar prediction (Table S16). There are no significant commonly enriched GO processes found when PITA prediction is used.

Unlike the shared program described between developing cerebellum and MB, only three terms such as activator, DNA binding, and DNA metabolism, were shared between small cell lung cancer upregulated genes and coherent targets in developing lung, involving miR-30, miR-200a, and miR-9, respectively. We did not find any shared processes between small cell lung cancer upregulated genes and coherent targets in developing lung using picTar or PITA prediction.

Discussion

This study focused on co-expressed miRNA-target pairs in temporally-specific and tissue-specific mammalian CNS development and malignancy. Many of the late-expressed miRNAs in developing cerebellum were characterized by their target non-coherence. Further identification of the shared CNS-specific network of enriched co-expressed GO terms surrounding synaptic transmission between cerebellar development and brain tumors confirmed the tissue and process specific mRNA co-expression with multiple miRNAs.

It is difficult to explain these findings based only on the mutual exclusion of miRNAs and targets. Although cell-type variety may facilitate the mutual exclusion, here the miRNA targets were compared with non-target genes that had a positively-correlated developmental profile to the target set using the same assay with the same averaging of cell-types, thus minimizing the effects of cell-type. In addition, the limited number of cell types in the cerebellum and the prevalence of some of the significant miRNAs in the CNS [33] make it more difficult to apply the mutual exclusion model. Furthermore, the identified synaptic transmission process is hard to explain as specific to a particular neuron.

Transcription factors and miRNA interactions might contribute to the phenomenon of miRNA–mRNA co-expression. Feedback loops between these two types of transcription regulators have been extensively reported [1], [12], [34]–[37]. A recent computational model by Shalgi et al. suggests that in a significant fraction of such interactions transcription factors regulate the miRNA or are regulated by miRNA and these forms of feed-forward loops are often observed in developmental processes. Consistent with the abundant sites in neuronal tissues of highly expressed genes [15], Tsang et al. reported co-expression of miRNA-target pairs in neuronal tissue computed by a score based on the number of conserved binding sites [38]. Among the two promoter-miRNA-target interaction models described by Tsang et al.[38], a circuit named Type I, which is equivalent to the special case of a feed-forward loop described by Shalgi et al.[36], recurs in different tissues and might explain the co-expression. Among the brain-enriched miRNAs, however, only miR-7 and miR-103 are consistently reported to be involved in the Type I circuit. For brain tissues, miR-9 and miR-128b are Type I, although miR-128b is not found in the motor neuron data [38]. As miR-9 is reported to have a matched binding motif with neuronal repressor NRSF/REST [39], NRSF might be a promoter that acts in the Type I circuit. Interestingly, recent findings of the in vivo binding partners of NRSF show synaptic transmission and other closely related GO terms among the most significant [40]. When compared with the 18 synaptic transmission genes evaluated in this study, however, only 5 genes (GAD1, CACNA1E, NPTX1, DLG4, and GAD2) are among those on the NRSF list. Exocytosis genes are not among the list of NRSF binding partners. In addition, the fact that NRSF is not significantly differentiated in brain tumors suggests that NRSF might not form a Type I circuit with miR-9 in brain tumors.

Small dsRNAs can induce transcription activation [41]–[42], which provides another perspective of the mRNA co-expression with miRNA–miRNA-mediated activation. Three genes, E-cadherin, P21, and VEGF, are induced by dsRNAs in the 5′ promoter region in human cancer cell lines [42]. In cerebellar development, VEGF is co-expressed with late-expressed miR-125, whereas E-cadherin and P21 are either not significantly changed or are co-expressed with late miR-9 and miR-22, respectively, in another series (personal communication with J.M. Lee). In addition, data from the RIKEN Brain Science Institute show that E-cadherin is late-expressed in murine cerebellar development. Interestingly, enrichment of miRNA core motifs are reported in the 5′ UTR compared with non-target motifs, and particularly the enrichment of reverse complementary miRNA core motifs in the 5′ UTR appears more frequently in the co-expressed genes of miR-124 than that in 3′ UTR [43], which raises a question as to whether the miRNAs are likely to induce expression from the 5′UTR. A survey of the 5′ UTR patterns of the synaptic transmission genes for 7-nt miRNA motifs shows that the significant miRNAs shared between cerebellar development and MB match various synaptic transmission genes. MiR-15 has the greatest degree of multiplicity of 5′ UTR matches with synaptic transmission for reverse complementary seed sequences among the significant late miRs. In Xenopus embryonic development, miR-15 regulates Nodal signaling and acts at the crossroads of Nodal signaling and WNT signaling [44]. Intriguingly, miR-15 is found most significant for its targets non-coherence, especially for signal transduction related functions in mouse development (Table S17) while target gene acvr2 is coherent to miR-15 consistent with that in [44].

Recently miRNA-target interactions have been approached in terms of translational repression of the target proteins. Substantial amount of miRNA inhibitions of translation are identified [45]–[46]. Taking into account of this alternative mechanism of miRNA regulation, the miRNA–mRNA co-expression might represent a negative feedback response at the level of translational repression. For example, Baek et al[45] has shown there is a significant cohort of genes were depressed during the protein synthesis with little or no change of mRNA expression although the depression is relatively modest compared with many other targets.

In this manuscript, we attempted to categorize the co-expressed miRNA-target pairs with regard to their functions and temporal-tissue specificity. Although the exact mechanism for the tissue and process specific miRNA–mRNA co-expression observed in the CNS remains to be clarified, our findings point to biologic processes that are likely part of the mechanism of interest. Knowledge of the significant miRNAs and processes shared between cerebellar development and MBs may facilitate target selection for brain tumor therapy.

Materials and Methods

miRNA in situ chip data analysis

miRNAs profiled at P7 and P60 of postnatal mouse cerebellum were hybridized on customized RAKE microarray chips with approximately 1700 probes. Significant differences between probes for the same miRNA from P7 to P60 were determined using a Wilcoxon rank sum test and the logarithmic fold-changes in expression were calculated. Fold-changes in relative expression of miRNAs during lung development were obtained from Williams et al.[24].

Prediction, mRNA data sets, coherent, and non-coherent target sets

TargetScanS [28], PITA[29] and picTar[30] target predictions are obtained from the respectively internet sites. There were 54 conserved miRNAs commonly present in the cerebellar development miRNA data set and there were 59 conserved miRNAs commonly present in the lung development miRNA data set. Mouse development mRNA data sets and MB mRNA microarray data are as described in Kho et al.[20]. Homologous genes were identified between mouse microarray chip probes and the human genome, resulting in 6790 homologous genes in the mouse cerebellar development data series and 6356 homologous genes in the mouse lung development data series. Coherent and non-coherent target sets in each tissue during development were calculated as described previously.

Significance test of miRNAs

Significance of the change in expression during development for both the coherent target set and the non-coherent target set of each miRNA were assessed using a Wilcoxon rank sum test against the corresponding non-target control set of genes. For example, the logarithmic fold-change of expression from P7 to P60 of the non-coherent target set of a late-expressed miRNA was tested against the late-expressed non-target genes, whereas the coherent target set of an early-expressed miRNA was tested against the early-expressed non-target genes.

GO (Gene Ontology), other functional terms, and significant GO terms

Gene sets from GO, BBID (Biological Biochemical Image Database), Biocarta, and Kegg pathways were obtained from DAVID Bioinformatics Resource (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov). Each functional set was intersected with the coherent target set and non-coherent target set of each miRNA and significant coherent ontological target sets or non-coherent ontological target sets were identified via a Wilcoxon rank sum test using Matlab (MathWorks; http://www.mathworks.com) against the corresponding non-target genes that had a positive-correlated developmental profile to the target set. In order to correct for multiple testing, we conducted Holms-Bonferroni adjustment according to the smallest p-value for each GO term from the Wilcoxon rank sum test (Table S18). In all three cases with TargetScans, picTar and PITA target predictions, synaptic transmission and related processes appear in the corrected top GO term list.

Robustness of GO analysis

We tested the enrichment of the non-coherent ontological terms for late miRNAs using sigPathway R package in the background of non-target late genes in developing cerebellum. The ontological terms are the above gene sets that intersect with gene sets of developmentally non-coherent late miRNA targets. sigPathway is an independent GO pathway analysis package [47]. Synaptic transmission and other related ontological get sets again are found significantly non-coherent to late miRNAs in developing cerebellum. The same test of the ontological enrichment of non-coherent miRNA targets in mouse Ptch+/− MB samples and human MB cell lines using sigPathway show a similar list of top pathways (Table S19).

5′UTR miR core motif match

The 5′ UTR sequences were obtained from the database developed by Mignone et al.[48]. miRNA core motifs (7nt) were searched for in the 5′ UTR of the genes involved in synaptic transmission, exocytosis, and chromosome categories (Table S20, S21, S22).

Validation in cerebellar development duplicate data set

All the significant target sets of miRNAs and GO terms were tested/cross-tested in the two duplicate developmental cerebellum mRNA expression series. There are in all 367 inconsistent genes among 6790 genes in terms of correlation of the expressions and 135 inconsistent among 2633 target genes. There are no inconsistent synaptic transmission genes. The correlations of the gene expressions are included in Table S6. The genes predicted by PITA and picTar for the GO processes in Table S6 are listed in Table S23 and Table S24 respectively.

Supporting Information

Heat-map image of the logarithmic expression of miRNAs in developing cerebellum P7 and P60.

(1.17 MB TIF)

miRNA expression data of developing murine lung.

(0.07 MB PDF)

Significant miRNAs in developing cerebellum using PITA prediction.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Significant miRNAs in developing cerebellum using picTar prediction.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Significant miRNAs developing lung.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Enriched non-coherent GO terms for late expressed miRNAs in developing cerebellum compared with non-targets of the same term.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Enriched processes of non-coherent genes of miRNA targets common in cerebellum development and Medulloblastoma.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Non-coherent gene ontological terms in developing cerebellum at days P10, P15, P21, and P30.

(0.06 MB XLS)

Significant GO terms in developing cerebellum comparing targets with non-target control set (PITA target prediction is used).

(0.01 MB PDF)

Significant GO terms in developing cerebellum comparing targets with non-target control set (picTar target prediction is used).

(0.01 MB PDF)

Summary of the enriched GO terms of late-expressed miRNA coherent/non-coherent targets in murine Ptch+/− MB and human MB cell line.

(0.03 MB PDF)

The statistic significance and other qualifications of the shared miRNA non-coherent GO terms between brain tumor and development (picTar target prediction is used).

(0.01 MB PDF)

The statistic significance and other qualifications of the shared miRNA non-coherent GO terms between brain tumor and development (PITA target prediction is used).

(0.02 MB XLS)

miRNA expressions in cerebellum development and rank change in NCI CNS tumors;

(0.02 MB XLS)

Common Enriched GO terms in developing Cerebellum and Lung.

(0.02 MB XLS)

Significant miRNAs for their targets' coherence or non-coherence in developing murine lung (picTar prediction is used).

(0.01 MB XLS)

Common Enriched GO terms in developing Cerebellum and Lung (picTar prediction is used).

(0.02 MB XLS)

Ranksum test of non-coherent targets of miR-15 against non targets in the same GO category.

(0.44 MB XLS)

Holm correction for non-coherent Go terms in developing cerebellum (including results from three predictions: TargetScanS, PITA and picTar).

(0.03 MB XLS)

List of Top Pathways of non-coherent targets of late miRNAs in developing murine cerebellum, Ptch+/− MB and human MB cell line using sigPathway R package.

(0.04 MB XLS)

5′ UTR of Synaptic Transmission Genes that match miRNAs.

(0.15 MB XLS)

5′ UTR of Exocytosis Genes that match miRNAs.

(0.06 MB XLS)

5′ UTR of Chromosome Genes that match miRNAs.

(0.15 MB XLS)

Enriched processes of non-coherent genes of miRNA targets common in cerebellum development and Medulloblastoma (PITA prediction is used).

(0.05 MB XLS)

Enriched processes of non-coherent genes of miRNA targets common in cerebellum development and Medulloblastoma (picTar prediction is used).

(0.03 MB XLS)

Acknowledgments

H.L. and I.S.K. thank Dr. Alvin Kho for his comments to the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Bill Bosl and Mr. Manway Liu for their comments and editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: HL is supported by NIH grant PO1NS047572-01A. ISK is supported in part by NIH National Center for Biomedical Computing grant 5U54LM008748-02. And the work is also partly supported by NIH grant R01 MH085143-01 and P50 NS040828-08. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bartel DP, Chen CZ. Micromanagers of gene expression: the potentially widespread influence of metazoan microRNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:396–400. doi: 10.1038/nrg1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, et al. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science. 2005;310:1817–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamore PD, Haley B. Ribo-gnome: the big world of small RNAs. Science. 2005;309:1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abrahante JE, Daul AL, Li M, Volk ML, Tennessen JM, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans hunchback-like gene lin-57/hbl-1 controls developmental time and is regulated by microRNAs. Dev Cell. 2003;4:625–637. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagga S, Bracht J, Hunter S, Massirer K, Holtz J, et al. Regulation by let-7 and lin-4 miRNAs results in target mRNA degradation. Cell. 2005;122:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, et al. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, et al. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sood P, Krek A, Zavolan M, Macino G, Rajewsky N. Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2746–2751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Animal MicroRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3′UTR evolution. Cell. 2005;123:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doench JG, Sharp PA. Specificity of microRNA target selection in translational repression. Genes Dev. 2004;18:504–511. doi: 10.1101/gad.1184404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez-Garcia I, Miska EA. MicroRNA functions in animal development and human disease. Development. 2005;132:4653–4662. doi: 10.1242/dev.02073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD, Hyslop T, Noch E, et al. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kho AT, Zhao Q, Cai Z, Butte AJ, Kim JY, et al. Conserved mechanisms across development and tumorigenesis revealed by a mouse development perspective of human cancers. Genes Dev. 2004;18:629–640. doi: 10.1101/gad.1182504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson JM, Newman M, Parker JS, Morin-Kensicki EM, Wright T, et al. Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes Dev. 2006 doi: 10.1101/gad.1444406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson PT, Baldwin DA, Scearce LM, Oberholtzer JC, Tobias JW, et al. Microarray-based, high-throughput gene expression profiling of microRNAs. Nat Methods. 2004;1:155–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams AE, Moschos SA, Perry MM, Barnes PJ, Lindsay MA. Maternally imprinted microRNAs are differentially expressed during mouse and human lung development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:572–580. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao Q, Kho A, Kenney AM, Yuk Di DI, Kohane I, et al. Identification of genes expressed with temporal-spatial restriction to developing cerebellar neuron precursors by a functional genomic approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5704–5709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082092399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardoso WV. Lung morphogenesis revisited: old facts, current ideas. Dev Dyn. 2000;219:121–130. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::aid-dvdy1053>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariani TJ, Reed JJ, Shapiro SD. Expression profiling of the developing mouse lung: insights into the establishment of the extracellular matrix. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:541–548. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.5.2001-00080c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1278–1284. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purves Dale, A GJ, Fitzpatrick David, Katz LawrenceC, Lamantia Anthony-Samuel, McNamara JamesO., editors. NeuroScience. Sinauer Associates, INC. Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blower PE, Verducci JS, Lin S, Zhou J, Chung JH, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles for the NCI-60 cancer cell panel. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1483–1491. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hohjoh H, Fukushima T. Expression profile analysis of microRNA (miRNA) in mouse central nervous system using a new miRNA detection system that examines hybridization signals at every step of washing. Gene. 2007;391:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fazi F, Rosa A, Fatica A, Gelmetti V, De Marchis ML, et al. A minicircuitry comprised of microRNA-223 and transcription factors NFI-A and C/EBPalpha regulates human granulopoiesis. Cell. 2005;123:819–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, et al. Human MicroRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shalgi R, Lieber D, Oren M, Pilpel Y. Global and Local Architecture of the Mammalian microRNA-Transcription Factor Regulatory Network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030131. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, Golub TR, Mootha V, et al. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3′ UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature. 2005;434:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsang J, Zhu J, van Oudenaarden A. MicroRNA-mediated feedback and feedforward loops are recurrent network motifs in mammals. Mol Cell. 2007;26:753–767. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mortazavi A, Leeper Thompson EC, Garcia ST, Myers RM, Wold B. Comparative genomics modeling of the NRSF/REST repressor network: from single conserved sites to genome-wide repertoire. Genome Res. 2006;16:1208–1221. doi: 10.1101/gr.4997306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson DS, Mortazavi A, Myers RM, Wold B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janowski BA, Younger ST, Hardy DB, Ram R, Huffman KE, et al. Activating gene expression in mammalian cells with promoter-targeted duplex RNAs. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:166–173. doi: 10.1038/nchembio860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li LC, Okino ST, Zhao H, Pookot D, Place RF, et al. Small dsRNAs induce transcriptional activation in human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17337–17342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607015103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwama H, Masaki T, Kuriyama S. Abundance of microRNA target motifs in the 3′-UTRs of 20527 human genes. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1805–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martello G, Zacchigna L, Inui M, Montagner M, Adorno M, et al. MicroRNA control of Nodal signalling. Nature. 2007;449:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature06100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, et al. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, et al. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian L, Greenberg SA, Kong SW, Altschuler J, Kohane IS, et al. Discovering statistically significant pathways in expression profiling studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13544–13549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506577102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mignone F, Grillo G, Licciulli F, Iacono M, Liuni S, et al. UTRdb and UTRsite: a collection of sequences and regulatory motifs of the untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D141–146. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Heat-map image of the logarithmic expression of miRNAs in developing cerebellum P7 and P60.

(1.17 MB TIF)

miRNA expression data of developing murine lung.

(0.07 MB PDF)

Significant miRNAs in developing cerebellum using PITA prediction.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Significant miRNAs in developing cerebellum using picTar prediction.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Significant miRNAs developing lung.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Enriched non-coherent GO terms for late expressed miRNAs in developing cerebellum compared with non-targets of the same term.

(0.01 MB PDF)

Enriched processes of non-coherent genes of miRNA targets common in cerebellum development and Medulloblastoma.

(0.02 MB PDF)

Non-coherent gene ontological terms in developing cerebellum at days P10, P15, P21, and P30.

(0.06 MB XLS)

Significant GO terms in developing cerebellum comparing targets with non-target control set (PITA target prediction is used).

(0.01 MB PDF)

Significant GO terms in developing cerebellum comparing targets with non-target control set (picTar target prediction is used).

(0.01 MB PDF)

Summary of the enriched GO terms of late-expressed miRNA coherent/non-coherent targets in murine Ptch+/− MB and human MB cell line.

(0.03 MB PDF)

The statistic significance and other qualifications of the shared miRNA non-coherent GO terms between brain tumor and development (picTar target prediction is used).

(0.01 MB PDF)

The statistic significance and other qualifications of the shared miRNA non-coherent GO terms between brain tumor and development (PITA target prediction is used).

(0.02 MB XLS)

miRNA expressions in cerebellum development and rank change in NCI CNS tumors;

(0.02 MB XLS)

Common Enriched GO terms in developing Cerebellum and Lung.

(0.02 MB XLS)

Significant miRNAs for their targets' coherence or non-coherence in developing murine lung (picTar prediction is used).

(0.01 MB XLS)

Common Enriched GO terms in developing Cerebellum and Lung (picTar prediction is used).

(0.02 MB XLS)

Ranksum test of non-coherent targets of miR-15 against non targets in the same GO category.

(0.44 MB XLS)

Holm correction for non-coherent Go terms in developing cerebellum (including results from three predictions: TargetScanS, PITA and picTar).

(0.03 MB XLS)

List of Top Pathways of non-coherent targets of late miRNAs in developing murine cerebellum, Ptch+/− MB and human MB cell line using sigPathway R package.

(0.04 MB XLS)

5′ UTR of Synaptic Transmission Genes that match miRNAs.

(0.15 MB XLS)

5′ UTR of Exocytosis Genes that match miRNAs.

(0.06 MB XLS)

5′ UTR of Chromosome Genes that match miRNAs.

(0.15 MB XLS)

Enriched processes of non-coherent genes of miRNA targets common in cerebellum development and Medulloblastoma (PITA prediction is used).

(0.05 MB XLS)

Enriched processes of non-coherent genes of miRNA targets common in cerebellum development and Medulloblastoma (picTar prediction is used).

(0.03 MB XLS)