Abstract

Two procedures commonly used to study choice are concurrent reinforcement and probability learning. Under concurrent-reinforcement procedures, once a reinforcer is scheduled, it remains available indefinitely until collected. Therefore reinforcement becomes increasingly likely with passage of time or responses on other operanda. Under probability learning, reinforcer probabilities are constant and independent of passage of time or responses. Therefore a particular reinforcer is gained or not, on the basis of a single response, and potential reinforcers are not retained, as when betting at a roulette wheel. In the “real” world, continued availability of reinforcers often lies between these two extremes, with potential reinforcers being lost owing to competition, maturation, decay, and random scatter. The authors parametrically manipulated the likelihood of continued reinforcer availability, defined as hold, and examined the effects on pigeons’ choices. Choices varied as power functions of obtained reinforcers under all values of hold. Stochastic models provided generally good descriptions of choice emissions with deviations from stochasticity systematically related to hold. Thus, a single set of principles accounted for choices across hold values that represent a wide range of real-world conditions.

Keywords: matching, stochastic response, limited hold, reinforcement probability, pigeons

Probability learning and concurrent reinforcement are procedures commonly used to study choice. They share many similarities. For example, subjects choose repeatedly between two options to obtain reinforcers: Human participants press buttons or push computer keys for points or money; monkeys look left or right for orange juice or raisins; rats run down alleys or press levers for food pellets; and pigeons peck keys for grain. Choice distributions under both procedures are influenced by reinforcer distributions and by other attributes of the reinforcers, for example, qualities, amounts, and delays. However, aspects of the procedures differ, and there is controversy concerning results, especially whether results from the two procedures are consistent.

Under probability-learning procedures, reinforcer availability depends on a random number generator that is activated (or fired) each time a choice occurs. Thus each choice is reinforced with some probability, and the probabilities are independent of previous events. For example, a left (L) choice might be reinforced with 0.4 probability and a right (R) one with 0.1 probability. In some studies the resulting response distributions are described as probability matching: Ratios of responses (L/R) equal ratios of reinforcement probabilities, or 4 to 1 in the example given (Myers, Lohmeier, & Well, 1994; Vulkan, 2000). Such matching is inefficient: probability matching leads to 34% of responses being reinforced in the example, whereas choosing L exclusively achieves 40% reinforcement, the maximum possible. Thus, unsurprisingly, recent studies indicate that probability matching is limited: It tends to occur early in training and when subjects are not strongly motivated. For example, Shanks, Tunney, and McCarthy (2002) showed that extended training, large monetary rewards, and feedback that indicates level of proficiency all tend to move choice distributions by humans toward exclusive preference for the best alternative. More generally, when subjects are motivated to obtain rewards quickly or to gain as many as possible, rats, pigeons, and people tend to choose the highest valued alternative a large proportion of the time, sometimes exclusively (see Fantino & Esfandiari, 2002; Herrnstein & Loveland, 1975; Shah, Bradshaw, & Szabadi, 1989; Shanks et al., 2002; Vulkan, 2000).

Concurrent-reinforcement procedures, developed and popularized by Richard Herrnstein and his colleagues, differ in that availability of reinforcers depends on the passage of time, most commonly under variable-interval (VI) schedules (see Herrnstein, 1997). For example, L choices might be reinforced an average of once per minute and R an average of once every 3 min. The original report by Herrnstein (1970) indicated that choice proportions matched proportions of obtained reinforcers, and the phenomenon came to be referred to as reinforcement matching. In the example just given, assuming that three times as many reinforcers were received on the left as on the right, the same left-to-right ratio of responses would be emitted to achieve a “matching” relationship. Note that matching in the concurrent-reinforcement case is between choices and experienced or obtained reinforcers, whereas in the probability-learning case, the term is used with respect to programmed probabilities of reinforcement. Because programmed and obtained are not always equivalent—obtained reinforcers partly depend on choice distributions—matching according to one definition may be inconsistent with matching according to the other. Furthermore, many studies using the concurrent procedure report “undermatching” (Baum, 1979), that is, response proportions are closer to 0.50 than are predicted by Herrnstein’s matching formulation, adding to the uncertainty as to how best to integrate results from the two procedures.

Research in the two areas is often directed at similar questions: How do consequences influence choice? What theories account for the distribution of responses? How do drugs, injury to the central nervous system (CNS), and psychopathologies affect choice? And what CNS systems underlie choice? Some attempts have been made to relate the two (Fantino, 1998; Herrnstein, 1970; Herrnstein & Loveland, 1975; Mackintosh, 1974), but researchers in these areas generally make little contact with one another. The main goal of the present research is to assess whether progress toward integration can be obtained by placing the two procedures along a single continuum, the hold continuum. Hold refers to the duration or probability that a reinforcer will remain available after it is initially scheduled. It indicates the lastability, persistence, or retention of a commodity or opportunity.

Probability learning and concurrent reinforcement lie at opposite ends of the hold continuum. Under concurrent-reinforcement procedures, a reinforcer remains available from the time it has “set up” until it is collected. An example from the “real” world would be mail delivered to a mailbox: The mail remains in the box until retrieved, no matter how long the interval between delivery and receipt. Another example is withdrawing money from a savings account: Once the money is deposited, it remains accessible until withdrawn. Pumping water from a slowly filling well or getting dinnerware from the cupboard are also good metaphors. These are goods or goals that are available until the requisite response, no matter the delay between when the goods are initially deposited and when the response is made.

In contrast, under probability-learning procedures, the reinforcer is available (or not), contingent on a single response: A possible reinforcer is not held beyond the one response. An example is throwing a desperation pass in a football game toward a crowd of receivers and opponents. Other examples of the temporary (or “one-shot”) availability of probability-learning reinforcers include taking a picture of the rare bird that flies by and placing a bet at a roulette table.

Many real-world instances lie between these extremes: Potential rewards are often available for a period of time, or series of responses, but with a limit. When the phone rings, answering will be effective, but only for the period of the ring. Ripe apples hang from the tree, but not forever. Availability of a $100 bill that happens to lie on the sidewalk is temporary, since it may be found by someone else or blown away by the wind. These last examples represent common occurrences in nature, where potential rewards such as fruit, prey, or mates are available only temporarily, and natural processes of scatter, decay, or competition limit access. The continued availability of a reinforcer is determined by many factors.

Three of the four experiments described in this article explore the role of systematic variations in hold probabilities on choice distributions. We are not the first to superimpose hold contingencies on operant reinforcement schedules, for example, as in limited hold procedures (see Boelens, 1984; Buskist & Morgan, 1987; Morse, 1966). As far as we know, however, we are the first to apply hold equally for all choices and to test whether choice distributions—under conditions spanning the range from probability learning to concurrent reinforcement—can be explained by differences in hold (see Killeen & Shumway, 1971, for related research).

Our initial experiment combined probability-learning and concurrent- reinforcement procedures in order to test a procedure for the experiments that followed. Pigeons chose repeatedly among three keys, with concurrently operating random ratio (RR) schedules programming the reinforcers on each of the keys. Unlike most concurrent ratio procedures, the random-number generators were activated for all keys whenever any key was chosen. Thus, if a subject responded five times to the right-hand key, all keys—left, middle, and right (L, M, and R)— had five opportunities for a reinforcer to become available. Once available, a potential reinforcer remained so until collected. The schedule is referred to as a dependent concurrent random ratio, or Concdep3RR (following MacDonall, 1988) and is similar to concurrent VIs: Reinforcers on one operandum partly depend on time (in the VI case) or responses (in the RR case) devoted to other operanda. It is essentially analogous to R. Herrnstein’s (1970) concurrent schedule but with reinforcers programmed probabilistically at each response instead of in time (see Lau & Glimcher, 2005; MacDonall, 1988). The Concdep3RR differs importantly from the more common concurrent VI, however, in that response rates and pauses do not influence reinforcer availability, and as is shown here, this facilitates analyses.

Experiment 1

Method

Subjects

Six Racing Homer pigeons (275 g to 350 g) had prior experience pecking keys for food rewards in the apparatus used in this study. The birds were maintained at 85% of their free-feeding weight and housed individually under a 16:8 hr light/dark cycle, with water continuously available in their home cage. The birds received food during the experimental procedure only if their weight fell below the 85% level.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of five identical Ger-brands operant-conditioning chambers, 28 × 30 × 29.5 cm. Three back-lit response keys were spaced along the wall on the left-hand side of the door, 21.5 cm above the floor. The chambers were housed within sound-insulating enclosures. The keys—referred to as L (left), M (middle), and R (right)—had diameters of 2 cm and were spaced 7 cm from one another. A food hopper was located in a 5.5 × 4.5 cm opening below the middle key, 7.5 cm above the floor. A houselight was mounted on top of the chamber. Apple eMac computers controlled events in the chamber, with programs written in TrueBasic.

Procedure

Each of the three keys was associated with a separate random number generator that controlled reinforcement availability (or reinforcer set-up) for that key. Responses to any of the keys activated (or “fired”) all three random generators. Thus, a response might be reinforced or lead to set up of reinforcers on all keys simultaneously, or on no keys, or on some keys. Once set up, a reinforcer remained available until collected (as under concurrent VI conditions), and no additional reinforcers could set up on that operandum (reinforcers did not “stack”). As was indicated previously, the schedule is abbreviated as Concdep3RR, with dep referring to reinforcer set-up events depending on responses to any key. The contingency, functionally identical to the two-operandum procedure described by Lau and Glimcher (2005), did not use a change-over delay (COD), that is, did not withhold reinforcers for switching among the keys. A session terminated after 3 hr or 210 rewards, whichever came first. Generally, all reinforcers were collected in sessions that averaged approximately 90 min.

Each response produced a 2-s interresponse interval (IRI), during which the houselight and key lights were dark. A reinforced choice produced 3 s of access to Purina Nutriblend pellets, identical to the normal feed given in the pigeons’ home cages, followed by the 2-s IRI. Responses during the IRI reset it, but such responses were rare. Key lights and the houselightwere darkened during reinforcer delivery, with a light above the hopper illuminating the available food. At other times, the house light and key lights were illuminated (white lights), and the hopper light was off.

The pigeons experienced six phases, each consisting of five sessions (with the exception of the first phase, which consisted of four sessions, this because of experimental error). Each phase provided a different set of reinforcement probabilities on the three keys, with the sum of the probabilities equal to 0.2 in all cases (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Probabilities of Reinforcer Set-Up for the Three Keys in Each Phase of Experiment 1

| Phase | Key L | Key M | Key R |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0667 | 0.0667 | 0.0667 |

| 2 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| 3 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.11 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 5 | 0.1 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| 6 | 0 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

Results

The solid lines connecting the solid points in Figure 1 show proportions of responses on L, M, and R keys for each pigeon (S1 through S6) during each session. Proportions were calculated by dividing total number of responses to a key during a session by the sum of responses on all three keys. The unconnected open points show the associated proportions of obtained reinforcers, calculated similarly. The numbers above the curve in the S1 graph indicate the programmed reinforcer probabilities, these being the same for all of the pigeons.

Figure 1.

Proportions of responses (solid circles and connecting lines) on left (L), middle (M), and right (R) keys for each of 6 pigeons (S1 through S6) during each session of Experiment 1. Also depicted are proportions of obtained reinforcers (open circles) and programmed reinforcer set-up probability (gray lines). These programmed probabilities, which were the same for all pigeons, are also written on the S1 graph for each phase.

Three aspects of these results are noteworthy. First, the pigeons responded similarly to one another: Intersubject consistency was high. This consistency is representative of most of the results throughout our four experiments, and to conserve space, we present averages of the 6 birds in many cases, or group all pigeons’ performances on a single graph in others.

Second, response proportions paralleled obtained reinforcers, a result shown more directly in Figure 2. Ongoing discussion in the literature focuses on how best to summarize choice–reinforcer relationships when more than two alternatives are available (Aparicio & Cabrera, 2001; Davison, Krageloh, Fraser, & Breier, 2007). A solution that minimizes theoretical assumptions focuses on ratios of response pairs and associated reinforcer pairs (e.g., L/M, M/R, and R/L). These ratios are shown in three graphs in Figure 2, response pairs as a function of reinforcer pairs on logarithmic coordinates. The graphs are based on responses and obtained reinforcers during the fifth (final) session of each phase. (We generally use fifth-session data for all detailed analyses.) Each point represents one pigeon during one phase. The good fits of the data to the least squares lines (high r2 values) and the absence of bias (represented by the y intercepts being close to 0.0) permit us to combine data from the three pairs onto a single graph, as provided in the lower right-hand quadrant. The exponents of the logarithmic functions were all approximately 1.0, indicating a direct 1:1 matching relationship. In other words, proportions of responses equaled proportions of reinforcers.

Figure 2.

Log of response ratios (left/middle, middle/right, and right/left) as a function of log obtained reinforcer ratios, these shown in the upper left, upper right, and lower left quadrants, respectively. Each point represents a pigeon’s performance during the last session of each phase. The lower right quadrant combines the data from the other three quadrants. The lines are the least-squares, best fitting functions.

A third conclusion can be drawn from the gray horizontal lines in Figure 1 that represent proportions of programmed reinforcers. The important observation is that choice proportions approximated programmed, as well as obtained, reinforcer proportions, indicating that the observed relationships were not caused by responses “driving” those distributions.

How might these data be explained? “Matching occurs naturally” has been offered as one explanation for choices under concurrent schedules, implying that animals and people have evolved to allocate choices in proportion to received reinforcers (Gallistel et al., 2007; Gallistel, Mark, King, & Latham, 2001). Our data are consistent with this interpretation, because they show rapid and consistent matching, but other possibilities are not excluded.

One alternative is that matching is the by-product of “lower-level” relationships in which choices are governed by the momentarily best option. In other words, matching at the molar level, as is depicted in Figure 2, may occur because subjects choose (or attempt to choose) the response option with the momentarily highest reinforcement probability (Shimp, 1966; Silberberg, Hamilton, Ziriax, & Casey, 1978). To examine this possibility, we calculated—for every response in a session—the probabilities that each of the three possible choices, L, M, and R, would be reinforced (for similar calculations in the concurrent VI case, see Williams, 1988; Staddon, Hinson, & Kram, 1981). Under the Concdep3RR contingencies, the probability that a particular response (an instance) will be reinforced on key k, denoted as Ik, is determined by two factors: the programmed probability of reinforcement on key k (here denoted as Rk) and the number of responses since k was last chosen (here denoted as n to indicate “responses since last selection of k”). The formula is

| (1) |

Because the exponent n indicates “since last selection of key k,” repetitions yield an n value of 1, the lowest value possible. The derivation of this equation is provided in Appendix A.

One can readily calculate Ik for each operandum at each response in a session and thereby determine, response by response, the “best choices,” that is, those that would maximize overall reinforcers per response. The result was a different sequence for each of the six phases of the experiment: LMRLMR … in Phase 1; RRLRMRLRRLRMRL … in Phase 2; MLML … in Phase 3; MM … in Phase 4; LMLRLMLR … in Phase 5; and MMMLMMML … in Phase 6. In other words, given that reinforcers were programmed probabilistically, and thus that the pigeons could not anticipate with certainty when or where a reinforcer was available, the sequences just described are the best that the pigeon could do to maximize reinforcers per response.

Instead of detecting this sort of highly structured patterned responses, we found evidence for an alternative response-allocation strategy, suggested by Nevin (1969, 1979) and others (Heyman, 1979): namely, that the birds were matched by stochastic responses. An example of stochastic matching is this: In an environment in which 60% of reinforcers were obtained from one key, 30% from another, and 10% from the third, respond as if governed by a biased three-sided object that had a 0.60 probability of landing on side A, 0.30 probability on side B, and 0.10 on side C. We evaluate stochasticity of responses in a number of ways and report the results of two tests, these representing the others. The data show that responses were generally consistent with those in a stochastic model, but we also identify deviations from stochasticity. (The term stochastic is used here to imply a Bernoulli-type process in which events are independent.)

The first test involved predicting proportions of each of the nine possible dyads (LL, LM, LR, etc.) from proportions of L, M, and R responses. If responses were generated stochastically, then the proportions of each of the dyads could be predicted from the first-order L, M, and R proportions. For example, if the proportion of L, M, and R responses in a session were .6, .3, and .1, respectively, then the proportions predicted from a stochastic model for L followed by M would be (0.6 × 0.3) or .09; of two Ls in a row would be .36; and so on. Note that the first-order proportions do not necessitate the dyad proportions. If responses were not stochastic in nature, then the same first-order proportions could be generated by 60 Ls in a row, followed by 30 Ms, followed by 10 Rs, and the emitted dyads would differ appreciably from those just described. Similarly, the deterministic “optimal response sequences” described here also would fail to produce stochastic-like dyads.

Because of the large number of data points (9 dyads × 6 conditions × 6 pigeons), we used an information statistic to summarize the distributions of dyads and compared the pigeons’ values to those predicted by the stochastic model. If responses were emitted stochastically, then the information contained in the dyad distribution would be the following:

| (2) |

Here, Prop(ki) and Prop(kj) refer to the proportions (across a session) on L, M, and R keys. In essence, the calculation provides the predicted information values in the dyads from the first-order L, M, and R proportions, taken two at a time.

The analogous information value calculated from the pigeons’ actual data was as follows:

| (3) |

Here, Prop(kikj) represents the proportions of the actually emitted nine possible dyads. We used each pigeon’s terminal sessions’ first-order proportions (proportions of L, M, and R) to predict that pigeon’s dyad proportions and then compared the pigeon’s dyad distribution—in terms of information value—to the predicted distribution.

The upper left graph in Figure 3 plots the information values obtained from the pigeons’ data (y axis) as a function of the values predicted from a stochastic model (x axis). The best-fitting line of these points has a slope very close to 1.0, indicating that the pigeons’ data closely followed the information expected from a stochastic model. That is, the pigeons’ behaviors were consistent with stochastic generation.

Figure 3.

Information contained in the distribution of response dyads (LL, LM, LR, ML …) as a function of the information value predicted if responses were stochastic. Data are from the last session in each phase of each of the experiments.

No single test suffices to indicate stochasticity (Knuth, 1969; Nickerson, 2002). Whereas the information statistic evaluates overall distributions of dyads, the “mean run length” statistic, which we present next, evaluates lengths of response strings, or “runs,” on a single key (e.g., RRRR, without interruption from responses to keys L or M). The average length of runs can be predicted on the basis of first-order proportions of L, M, and R, assuming that the generating process was stochastic. The question then becomes whether the pigeons’ mean run lengths were similar to those predicted by the stochastic model.

To calculate mean run length on operandum k, we divide the number of responses to k by the number of response strings composed exclusively of ks, or

| (4) |

As an example, consider the following sequence: LLLMLR-RLLMLLLL. This sequence has 10 individual responses to L and four strings composed of Ls: LLL, L, LL, and LLLL, in that order. Thus, the MRL for L is 2.5 (or 10/4).

If responses were stochastic in nature, then the actual mean run lengths should be related to the first-order L, M, and R response proportions according to Equation 5:

| (5) |

Here Prop(k) indicates the proportion of responses on key k across the entire session.

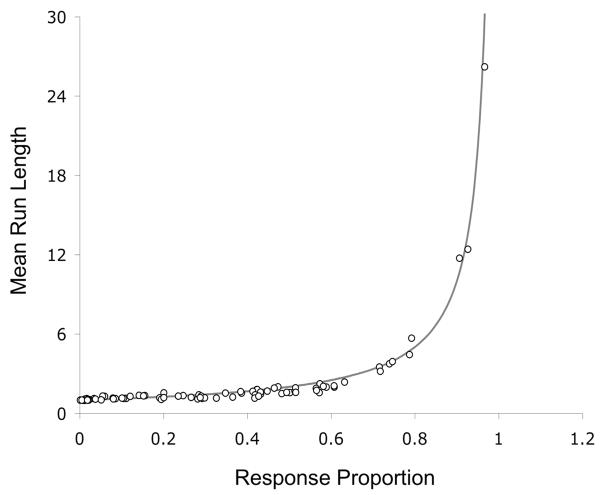

Figure 4 shows the pigeons’ mean run lengths as a function of their first-order response proportions, with each point representing an individual bird’s responses on each of the three keys in the final session of each phase of the experiment. The drawn function is that expected from a stochastic model (Equation 5). The pigeons’ mean run lengths approximated the stochastic model, although the data points appeared to fall below the stochastic line in the middle range, indicating a possible deviation from stochasticity.

Figure 4.

Mean run lengths on each key during the last session of each phase of Experiment 1 as a function of the proportion of responses to that key. Data from all of the pigeons are shown. The drawn line is the expected function if responses were stochastic.

Additional analysis indicated a tendency in some phases for the pigeons to switch among the keys more than that predicted by a stochastic model. Expected switch rates were calculated by taking the proportions of responses on each key (e.g., L = 0.6, M = 0.3, and R = 0.1) and squaring them to predict the proportion of each “repeat pair” (LL = 0.36, MM = 0.09, and RR = 0.01). The sum of these probabilities (0.46) should (assuming statistical independence) represent the proportion of response repetitions; and (1-repetitions) equals switches (0.54).

Table 2 provides average proportions of switches (switches/switches + repeats; left column), the switch proportions predicted from the stochastic model (center column), and the ratio of these two values (right column). The pigeons switched significantly more than was expected in Phases 2 and 3, paired t tests (5) = 4.96 and 4.54, p < .01, in both cases. Although these data are only suggestive of a bias in switch rates, they are presented here because they led to similar evaluations in the later experiments, and these showed that the pigeons’ switch versus repeat responses systematically deviated from otherwise stochastic emissions.

Table 2.

Ratio of Actual Versus Expected Proportion of Switches Per Phase in Experiment 1

| Phase | Actual switch proportion | Expected switch proportion | Actual:Expected ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.703 | 0.660 | 1.066 |

| 2 | 0.622 | 0.538 | 1.155 |

| 3 | 0.647 | 0.516 | 1.257 |

| 4 | 0.080 | 0.082 | 0.994 |

| 5 | 0.648 | 0.612 | 1.060 |

| 6 | 0.381 | 0.379 | 1.000 |

Shown are arithmetic means of the 6 birds’ performances.

Discussion

Under a dependent concurrent RR schedule, proportions of responses by pigeons matched (or equaled) proportions of obtained reinforcers. Matching occurred rapidly and was consistent across 6 pigeons. Many aspects of the procedure differed from commonly used concurrent schedules: (a) Reinforcers were scheduled probabilistically, with availability dependent on all responses (i.e., every response increased the probability of reinforcement on all keys). (b) Three choice alternatives were provided, rather than the more common two. (c) Responses were “discrete,” with a 2-s IRI pause between each response (and after reinforcement). And (d) overall frequencies of reinforcement were high in comparison with those in many experiments in this field of study, with about one reinforcer for every five to six responses.

Each of these may have contributed to rapid, orderly, and consistent changes in responses. A few other experiments have used similar procedures, although with only two choice alternatives (Lau & Glimcher, 2005; MacDonall, 1988; Meisch & Spiga, 1998), and choices in those cases were also related in orderly fashion to reinforcers but were generally less sensitive to changes in reinforcer ratios (exponents of the power function < 1.0).

Response proportions matched both obtained and programmed reinforcers. The latter relationship is of interest because (assuming stochastic generation) matching to programmed reinforcers maximizes overall reinforcers per response under the present conditions. We independently verified, by modeling the contingencies with different response-allocation strategies and proportions, that if a subject responds stochastically, matching is the most effective choice distribution. Thus, as a somewhat oversimplified general statement, the birds stochastically matched and, by so doing, maximized reinforcements.

Two statistics supported the hypothesis that the pigeons’ responses were stochastic-like in nature, one a measure of information and the other a measure of run lengths. However, deviation from stochasticity was also identified: In two phases the pigeons switched from one key to the others more frequently than was predicted by a stochastic model. Such switching could be due to the close physical proximity of the keys, absence of CODs, a species-specific (or “natural”) tendency for pigeons to switch among choice alternatives, or some other “general tendency.” Another possibility is that switching was differentially reinforced (Plowright & Shettleworth, 1990). These hypotheses are explored in Experiments 2 through 4. The primary goal of Experiment 1 was met, namely to assess whether the Concdep3RR procedure provides data of sufficient order to test effects of hold.

Experiment 2

As is indicated in the previous section, in some situations, a potential reinforcer remains available until collected, whereas in other situations, the potential reinforcer is temporary, lasting for an instant or one response. Many cases lie between these extremes. Experiment 2 studied choices by pigeons under contingencies similar to those in Experiment 1 but in which we systematically varied the probability that a reinforcer, once set up, would remain available. The hold (h) parameter specified that probability, the schedule is referred to as Concdep3RRh, with h a variable between 0.0 and 1.0. When h = 0.0, if a response did not gain a just-made-available reinforcer (because the response was to another key), that potential reinforcer was removed (the probability of retention was zero). When h = 1.0, a reinforcer remained available from the time it set up until received, no matter how long the interim. As has been indicated, these extremes represent two large bodies of literature encompassing research on probability learning and concurrent reinforcement. The contribution of this experiment is to explore hold probabilities that lie between these extremes.

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

Subjects and apparatus were the same as in Experiment 1.

Procedure

Probabilities of reinforcement set-up were constant across 10 phases: L = 0.10, M = 0.06, and R = 0.04. The procedure differed from Experiment 1 only in that we systematically varied hold. Each key had two random number generators associated with it, one for reinforcer set-up, as was described previously, and another for hold. If a reinforcer was available on a particular key, it would remain only if the output of the hold random number generator was less than h. Thus, for example, if h = 0.8, then a previously available reinforcer had an 80% chance of remaining available; this test applied following responses to any of the keys. As h decreased in value, it became increasingly unlikely that a reinforcer would remain available for an extended period. We studied how h affected choices. Appendix B provides an outline of these combined contingencies.

Because the probabilities of reinforcer set-up and hold both influenced what the pigeons actually experienced, we first describe the way in which these two variables interacted. The probability that a given response would be reinforced (Ik) was a joint function of the following: (a) the probability of reinforcer set-up on a key (Rk); (b) the probability that a previously set-up reinforcer would remain available (h); and (c) the number of responses having elapsed since the key in question was last chosen (n).

Equation 6 shows how these three variables determined the probability of reinforcement for each response. (See Appendix A for the derivation of the equation.)

| (6) |

Figure 5 iterates Equation 6 to show response-by-response probabilities of reinforcement along the y axis, given a 0.2 probability of reinforcer set-up (Rk) and some number of responses since the key was last chosen (n) along the x axis. Each curve represents a different hold probability, ranging from 1.0 to 0.0. Consider first the 1.0 curve. The probability that a response to key k would be reinforced increases from its initial 0.2 for the first response after a choice of key k and approaches 1.0 as the number of intervening responses (away from key k) increases. Consider next the 0.0 curve: a flat line at the bottom of the graph. The probability of reinforcement is constant (0.2 in this case), no matter how many responses intervene. At intermediate values of h, reinforcement probabilities increase over successive responses away from the key, but the asymptotic ceilings of these probabilities decrease with decreasing hold values. Thus, despite equal initial probabilities of set-up, lower hold values result necessarily in fewer reinforcers per response.

Figure 5.

The probability that a given response to key k would be reinforced as a function of the number of responses to other keys (i.e., responses since the last selection of key k, or n). The functions drawn are for different values of the hold parameter, shown to the right of the graph.

As in Experiment 1, each phase consisted of five sessions. During the first phase, the value for h was 1.0, or “hold until collected,” exactly as in Experiment 1. The value of h then decreased by 0.2 with each five-session phase (values of 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and finally 0.2). After a 1-month hiatus, Phases 6 through 10 reversed the order of these values (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and finally 1.0).

Results

We first describe effects of h on choice distributions. Figure 6 shows average proportions of responses on L, M, and R keys during each session (solid circles connected by the solid line) together with the proportions of obtained reinforcers (open circles). On top of each graph is the value of h in five-session blocks. As h varied, obtained reinforcers and emitted responses changed in similar ways. The gray lines represent the distribution of responses that would maximize overall rates of reinforcement given stochastic emission.

Figure 6.

Proportions of responses (solid circles and connecting lines) on left, middle, and right keys averaged across the 6 pigeons during each session of Experiment 2. Also depicted are proportions of obtained reinforcers (open circles) and response proportions that would maximize reinforcement (gray lines). The hold values, which were the same for each of the keys, are shown on top of each graph.

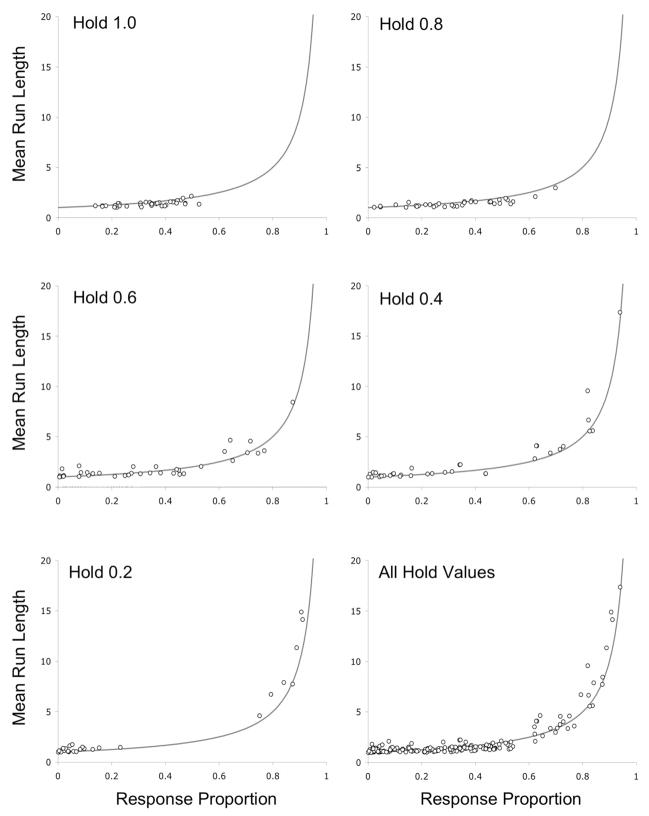

Figure 7 demonstrates that responses and obtained reinforcer proportions were indeed closely related. Shown there are the best-fitting power functions for each hold value. The data are from the fifth and final session of each phase, with the two replications of each h value both shown on the graph. The individual points are from individual pigeons, that is, all birds are grouped in these graphs. The exponent values were all less than 1.0, as often reported under concurrent schedules of reinforcement, and did not differ significantly from one another; repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) yielded F(4) = .228, ns. Thus, power functions describe choices under all values of h, with the exponents of the functions all somewhat less than 1.0.

Figure 7.

Log ratios of response pairs (L/M, M/R, and R/L) as a function of the associated log ratios of obtained reinforcers for all pigeons in Experiment 2. Each point represents a pigeon’s performance during the last session of a phase, with the different hold values (phases) presented separately in five graphs, and the combination shown in the bottom right graph. The lines are the least-squares, best fitting functions.

These orderly relationships were obtained despite the fact that as h decreased, obtained reinforcers became increasingly asymmetric across the three keys, and overall reinforcers per response fell. Average reinforcers per response (with standard errors in parentheses) for the 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and 0.2 hold conditions were .172 (.001), .136 (.002), .115 (.002), .102 (.002), and .097 (.001), respectively. Experiment 4 controlled for the differences in reinforcement rate and distribution.

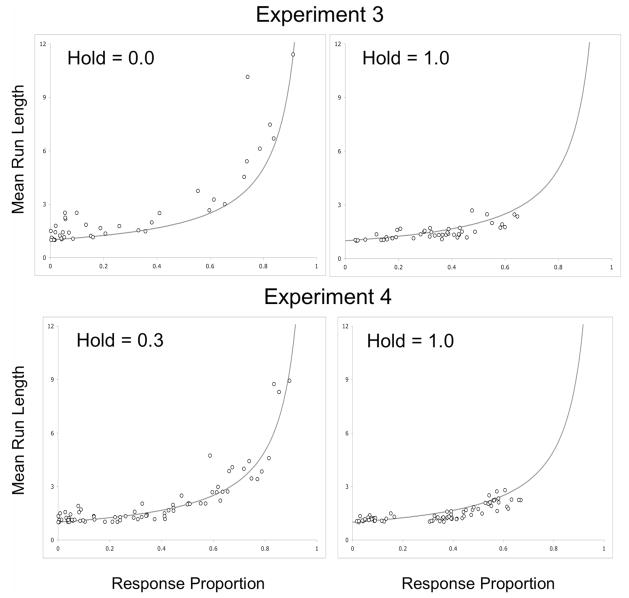

Responses were generally stochastic-like under all values of h. The upper right-hand graph in Figure 3 provides a summary of the dyad information statistic, grouping all birds and all hold values on a single graph. The birds’ dyads closely approximated those predicted from the stochastic model. The mean run-length analyses also indicated stochastic-like responding (see Figure 8), but, as in Experiment 1, deviations were observed, with points tending to fall below the line at high values of h and above the line at low values.

Figure 8.

Mean run lengths in Experiment 2 as functions of the proportions of L, M, and R responses. The separate graphs show performances under the different hold conditions. Data from all pigeons are combined on each graph. The drawn lines are the expected functions if responses were stochastic.

The deviation from stochasticity was related to switch rates. Figure 9 shows the ratio of pigeons’ switch proportions to those expected from the stochastic model, similar to that in Table 2. Ascending and descending legs of the experiment are averaged across the 6 pigeons. Switching was more frequent than stochastic prediction when hold values were high (1.0 and 0.8), equal to the stochastic prediction at an intermediate value of hold (0.6), and less frequent when hold was low (0.4 and 0.2), with these differences shown to be highly significant according to a repeated-measures ANOVA, F(4) = 9.89, p = .0001. In other words, in conditions similar to concurrent-reinforcement procedures, switching was more frequent than that predicted by a stochastic model, and as conditions approached that of probability-learning procedures, switching became less frequent than that predicted by the model. Different switch rates were therefore not caused by natural tendencies, absence of COD, layout of the operant chamber, or any other constant factor. They were controlled by reinforcement contingencies involving hold.

Figure 9.

Ratio of the average pigeon switch proportions to expected switch proportions expected from a stochastic process as a function of hold values. Error bars represent standard errors.

Discussion

The main conclusion from this experiment is that the same power-function relationships that describe performance under concurrent-reinforcement procedures, in which reinforcers remain available until received, also describe performances when reinforcers are temporarily available. In this experiment, exponents of the power functions were less than 1.0, indicating some insensitivity to changes in reinforcement probabilities. We cannot explain the difference between the 1:1 matching observed in Experiment 1 and the undermatching in the present results, but one possibility was that in this case, the programmed reinforcement probabilities were relatively similar across the three keys— .04, .06, and .10—and that their associations with R, M, and L keys were constant throughout the experiment.

Responses once again approximated a stochastic model, this being shown by both information and mean run-lengths statistics. Also, as in two phases of Experiment 1, switching rates differed from prediction by the model: Higher-than-expected switching occurred when h values were high and lower-than-expected when h values were low. The systematic change in switch frequencies is consistent with the hypothesis that the pigeons were sensitive to the effects of switch frequencies on reinforcements. When h was high, switch responses were more likely to be reinforced than were repetitions. This follows from iterating Equation 6 and can be seen in Figure 5: The probability of being reinforced on a given key is lowest immediately after having responded to that key and increases with time away. Thus, except when reinforcer probabilities are highly skewed, switching to a key—after some number of responses away—is more likely to be reinforced than is repetition. When h values were low, quite the opposite was true: repetitions were most likely to be reinforced. This follows from the relative flatness of the cumulative probability-of-reinforcement functions resulting in the subjects being rewarded for persisting on the best available key.

Stated informally, if reinforcers were unlikely to follow repetitions, the pigeons switched frequently; if repetitions on the best available key were likely to be reinforced, switches were infrequent. It is therefore likely that reinforcement for switching versus repetition influenced the birds’ choices in a way that interacted with the general stochastic-matching tendency. This interpretation combines a version of maximizing, one that involves sensitivity to differences in reinforcements for switching versus repetition, with stochastic generation. Machado (1992) suggested a related theory that is discussed in the General Discussion.

Experiment 3

The lowest h value in Experiment 2 was 0.2, whereas h = 0.0 in probability- learning experiments. Experiment 3 directly compared a hold value of 0.0 (representing probability learning) with a value of 1.0 (representing concurrent reinforcement). We predicted, on the basis of Experiments 1 and 2, that although distributions and overall frequencies of reinforcement would differ, power-function relationships would describe choices under both conditions. We also predicted that responses would generally be stochastic but that switch rates would differ from stochastic predictions and would differ in opposite directions under the two conditions.

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

The apparatus and subjects were the same as in Experiment 2 except that one pigeon (Subject 6) was removed because of equipment limitations.

Procedure

Six 5-session phases used the same Concdep3RRh as in Experiment 2 with some phases representing probability learning (h = 0.0) and others representing concurrent reinforcement (h = 1.0). The same reinforcement set-up probabilities were used as in Experiment 2 (L = 0.10, M = 0.06, and R = 0.04), but in this case we systematically varied which key was associated with which value. Details of the procedure are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Probability of Reinforcer Set-Up and Hold for the Three Keys Per Phase in Experiment 3

| Phase | Type | Hold | Key L | Key M | Key R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Concurrent | 1.0 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| 2 | Probability | 0.0 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| 3 | Probability | 0.0 | .04 | .10 | .06 |

| 4 | Concurrent | 1.0 | .04 | .10 | .06 |

| 5 | Concurrent | 1.0 | .06 | .04 | .10 |

| 6 | Probability | 0.0 | .06 | .04 | .10 |

Results and Discussion

Figure 10 shows proportions during each session, of emitted responses (connected solid points), obtained reinforcers (open points), and reinforcement-maximizing response distributions assuming stochastic generation (gray lines). The gray background indicates sessions under the h = 0.0 condition, and the white background indicates sessions under h = 1.0. Data are averages across the 5 pigeons. As in the previous experiments, response proportions varied with obtained reinforcers. However, under h = 0.0, responses were far from the maximizing proportions. This was especially clear during the last phase of the experiment, during which exclusive choices of the R key would have maximized reinforcers, but averages across the 5 birds were distributed more equally across the three keys. In this particular phase, the average was influenced by 3 birds that responded extensively to keys that did not provide the highest probability of reinforcement (i.e., not R). As has been observed by Vulkan (2000), it is possible for organisms to become “trapped,” responding to a nonoptimal key because doing so exclusively provides no information about the other keys. Figure 11 shows individual performances in Phase 5 (hold = 1.0) and Phase 6 (hold = 0.0). Despite relatively uniform responses in Phase 5, Phase 6 shows marked individual differences.

Figure 10.

Proportions of responses (solid circles and connecting lines) on left, middle, and right keys averaged across the 5 pigeons during each session of Experiment 3. Also depicted are proportions of obtained reinforcers (open circles) and response proportions that would maximize reinforcement (gray horizontal lines). The background white areas indicate hold values of 1.0 and the background gray areas indicate hold = 0.0.

Figure 11.

Proportions of responses on left, middle, and right keys for individual subjects in Phase 5 (hold = 1.0) and Phase 6 (hold = 0.0) of Experiment 3. Each symbol represents 1 subject across the three graphs.

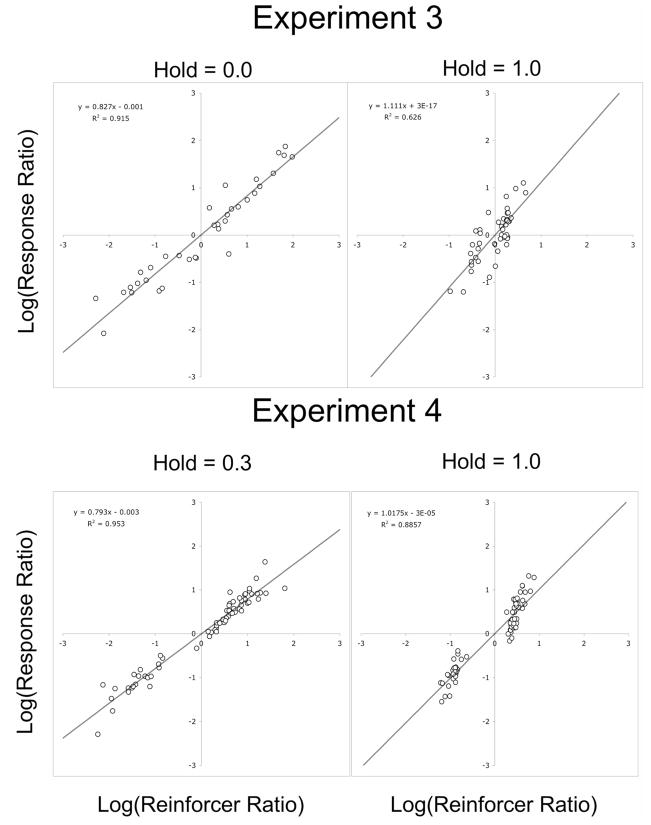

The top two graphs in Figure 12 show that power functions again described the relationships between choices and reinforcers in both conditions, with exponents equal to 0.83 under h = 0.0 and and exponents equal to 1.11 under the h = 1.0 condition, a difference that did not reach statistical significance according to a paired t test, t(4) = 0.468, ns. As in Experiment 2, reinforcement frequencies were higher under h = 1.0 (.169 reinforcers per response, SE = .005) than under h = 0.0 (.085 reinforcers per response, SE = .005).

Figure 12.

Log ratios of response pairs (L/M, M/R, and R/L) as a function of the associated log ratios of obtained reinforcers for all pigeons in Experiments 3 and 4. Each point represents a pigeon’s performance during the last session of a phase. The lines are the least-squares, best fitting functions.

Choices in both cases approximated the stochastic model, as is shown by the mean run lengths in the top two graphs of Figure 13; but as predicted by Experiment 2, most of the data points fell on or below the model curve in the h = 1.0 condition, whereas the opposite was true in the h = 0.0 phase, with most of the data points falling on or above the model. The dyad statistic (not shown here, to conserve space) was the same as in the previous experiments: Pigeons generally approximated the stochastic model. Also as was predicted, switch proportions were significantly higher under h = 1.0 than under h = 0.0, t(4) = 10.32, p = .0005, as is shown by the left-hand graph in Figure 14.

Figure 13.

Mean run lengths in Experiments 3 and 4 as functions of the proportions of responses. The drawn lines are the expected function if responses were stochastic.

Figure 14.

Ratios of pigeon switch proportions to expected switch proportions from a stochastic process as a function of hold values in Experiments 3 and 4. Averages across the 5 pigeons are shown. Error bars represent standard errors.

We conclude that schedules representing two commonly used procedures, concurrent reinforcement and probability learning, generated similar choice-to-reinforcer relationships: Stochastic responses are related to reinforcements by power functions. As in Experiment 2, switch proportions were higher under concurrent-reinforcement conditions than was predicted by the stochastic model and lower under probability-learning conditions. Thus, in general the results confirmed predictions from the previous experiment.

Experiment 4

In each of three experiments, choices were well described by power-function relationships to reinforcers and were generally consistent with stochastic generation. However, the pigeons switched at higher rates than predicted by the stochastic model when hold values were high, thus replicating a common finding in the concurrent-reinforcement literature, and switched at lower-than-expected rates (they repeated more than expected) when hold values were low, in the range of probability-learning studies. In addition, the exponents of the functions relating choice proportions to reinforcers may also have been influenced by h. The question in this experiment is whether these effects were due to, or confounded by, differences in obtained rates of reinforcement. In Experiments 2 and 3, reinforcement was more frequent under high hold conditions than under low hold conditions. To answer this, we equalized (to the extent possible) the overall reinforcements per response as well as the distributions of reinforcers across the three keys and compared two conditions, one with a hold value of 1.0 and the other with a hold value of 0.3. (It was not possible to equate reinforcement frequencies with hold values much lower than 0.3.)

Method

Subjects and Apparatus

Apparatus and subjects were the same as in Experiment 3.

Procedure

Experiment 4 used a Concdep3RRh contingency identical to that in the previous experiments, with the following exceptions. Ten 5-session phases were presented with alternating phases of h = 0.3 and h = 1.0. The 0.3 condition was presented first, with the probabilities of reinforcement being L = 0.1, M = 0.06, and R = 0.04, as in Experiments 2 and 3. We used the results of that phase, plus the previous experiments, to equate reinforcement frequencies under the h = 1.0 condition. Because many set-up reinforcers were never received under h = 0.3, the programmed reinforcement probabilities had to be considerably lower during the h = 1.0 phase, and the cross-key ratios also had to differ, resulting in set-up values of L = 0.066, M = 0.026, and R = 0.008. Subsequent phases alternated back and forth between the two conditions, with all parameters unchanged. In overview, this experiment attempted to equate reinforcement under 1.0 and 0.3 hold conditions in order to evaluate effects of hold contingencies on choices when the distributions of obtained reinforcements were approximately equal.

Results and Discussion

Overall average reinforcements per response during the fifth (terminal) sessions were 0.097 in the 0.3-hold condition and 0.096 under 1.0 hold. Thus, we successfully controlled for reinforcement frequencies. The main results were similar to those in the previous experiments. First, choices were related to reinforcers by power functions, this shown by the bottom graphs in Figure 12. As in Experiment 3, exponents of the power functions were lower in the 0.3 hold condition (0.79) than in the 1.0 hold condition (1.02), and in this case the differences were statistically significant, t(4) = 4.991, p = .0075. As in Experiments 1, 2, and 3, mean run lengths were again approximated by the stochastic model (bottom graphs in Figure 13) with the 1.0-hold data tending to fall below the stochastic function, and the 0.3-hold data more closely approximating that function. The dyad information statistic showed effects similar to those in the previous experiments. Proportions of switches, when compared to those expected from a stochastic model, were again significantly higher in the 1.0-hold condition than in the 0.3-hold condition, t(4) = 3.88, p = .0178, this shown by the right-hand graph in Figure 14. Thus, the main results obtained in Experiments 1, 2, and 3 were replicated when reinforcer frequencies were equated.

General Discussion

Concurrent reinforcement and probability-learning procedures, both commonly used by behavioral psychologists to study choice, lie at opposite ends of a hold continuum. Hold is defined in terms of the likelihood that a reinforcer, once scheduled, will remain available. Under concurrent-reinforcement procedures, continued availability is certain: The reinforcer is available until collected. An important consequence is that reinforcement probability increases with successive responses to “other” operanda (or passage of time when reinforcer set-up is governed by interval schedules). Under probability-learning procedures, the probability of a reinforcer is constant, and neither “other” responses nor passage of time influences that probability.1 In quantitative terms, the probability that a particular reinforcer will remain available, given a response to another alternative, is 1.0 under concurrent contingencies and 0.0 under probability learning. Many examples of concurrent and probabilistic contingencies can be identified in outside-of-lab, natural environments, but many more examples lie between the two, that is, where 0.0 < hold < 1.00. In nature, most potential reinforcers are available only temporarily because of spoilage, decay, maturation, competition, and so forth. We studied how choices are affected by hold and here report four main findings.

First, across all values of hold, response proportions varied as power functions of the reinforcer proportions actually experienced by the pigeons (obtained proportions). Power-function relationships (sometimes confusingly referred to as generalized matching) are commonly reported in the concurrent-reinforcement literature, and the excellent fits of the data to that function throughout the current experiments support the generality of that characterization (Baum, 1979).

The second finding is less secure, but it appears that the exponents of the power function (represented by the slopes of the function on log–log coordinates) were influenced by hold. Clear relationships between hold values and exponents were not observed in Experiments 2 and 3, but rates and distributions of reinforcers may have been confounding influences. In Experiment 4, with reinforcer rates and distributions equated, exponents were significantly higher under high hold conditions than under low hold conditions (exponent values of 1.02 vs. 0.79). Furthermore, across all of the experiments, the average exponent values under high hold (h = 1.0) were 0.99, 0.85, 1.11, and 1.01 in Experiments 1 through 4, respectively, for an average of 0.99. Thus, under a Herrnstein-type concurrent contingency, sensitivity was high, and choice proportions matched reinforcers. When hold values were at their lowest levels (0.2 in Experiment 2, 0.0 in Experiment 3, and 0.3 in Experiment 4), exponent values were .86, .83, and .79, respectively, for an average of 0.83, and sensitivity was correspondingly lower. Thus exponents (and therefore sensitivity to changes in reinforcement) appear to be lower under probability-learning conditions than under concurrent-reinforcement conditions.

One possible explanation is that withdrawal of potential reinforcers under low hold conditions increased uncertainty. Two considerations support this claim. First, under concurrent conditions, with emission of “other” responses, the probability of reinforcement approaches 1.0, and this is not the case under low hold conditions. Second, distributions of experienced reinforcers are relatively constant under concurrent, but not probability-learning, procedures. In the concurrent case, if reinforcers are programmed in 3:2:1 ratios, for example, then the ratio of obtained reinforcers is likely to approximate 3:2:1 over an entire session, over each half of the session, each quarter session, and so on, with variability of obtained reinforcers increasing slowly as the window size gets smaller. The probability-learning case differs in that reinforcer distributions depend, to a much larger extent, on emitted responses. Thus, although programmed in a 3:2:1 ratio, short-term swings in proportions of obtained reinforcers can cause subjects to become “trapped” by a cycle of skewed responses and reinforcers. The dependence on response distributions, in the probability-learning case, makes it less likely that reinforcer distributions will be consistent across subjects and within sessions. That these variations may lead to a “flatter” distribution of responses (lower exponents) is indicated by Gharib, Gade, and Roberts (2004), who showed that response variability in rats’ bar presses increased with reinforcer uncertainty.

The third noteworthy result is that, in all cases, stochastic models provided good—but incomplete—descriptions of the pigeons’ performances. We analyzed response sequences in a number of ways and described two: the information contained in successive dyads and average run lengths. In both, the pigeons’ data approximated a stochastic model (see Lee, Conroy, McGreevy, & Barraclough, 2004; Nevin, 1969, 1979). Thus choice proportions varied as power functions of reinforcement proportions, and this relationship was achieved through stochastic-like emission of choice responses.

The stochastic description was incomplete, however, because small but consistent deviations from the model were observed, this providing the fourth main finding. As hold values approached 1.0 (the concurrent-reinforcement end of the hold continuum), switching among keys was more frequent than that predicted by the stochastic model, whereas as hold approached 0.0 (the probability-learning end), repeating was overly frequent. Again, Experiment 4 shows that these results were not due to differences in reinforcement rates; rather, the hold values themselves were responsible.

An important series of experiments by Machado (1992) may help to explain this combination of results. In one experiment, Machado reinforced pigeons for emitting frequency-dependent sequences of responses across two keys. When the unit was defined in terms of two consecutive responses, the pigeons would be reinforced with high probability for emitting the least frequent of the four possible dyads: LL, LR, RL, and RR. As can readily be shown, repetition of LLRRLLRR … will maximize reinforcements, and indeed, some birds learned to do just that. Response sequences of those birds were repetitive and predictable. However, when the unit was defined in terms of three consecutive responses, the repeated sequence necessary to maximize reinforcement was too complex for the birds to learn, and the birds in those conditions responded in stochastic-like fashion (see also Manabe, Staddon, & Cleaveland, 1997). In some of Machado’s studies, the birds’ responses were well described as a Markov process; in others, as a Bernoulli process. The distinction is not important for present purposes, since probabilistic responses were engendered in both cases. In essence, when the birds could discriminate and learn simply to repeat, they did so. If such learning was not possible and the environment was uncertain, then the birds reverted to responding in probabilistic fashion.

Our data are consistent with Machado’s theory if we hypothesize that the birds discriminate differential reinforcement for switching versus repetition (MacDonall, 1999, provided evidence for this) and that they otherwise respond stochastically with a power-function relationship to reinforcers. Under high hold, including the commonly studied concurrent VI case, switches are more likely to be reinforced than are repetitions. This can be understood informally by considering the case in which a response had just been emitted to key L. Whether or not it was reinforced, that response increased the probability of reinforcement on a different key, and the more responses to one key, the higher the probability of reinforcement for switching to another. Low hold conditions, including those in most probability-learning experiments, differ. It is easy to demonstrate that repeatedly responding on the alternative associated with the higher (or highest) probability of reinforcement (and thus never switching) will garner the most reinforcers. High switch rates (in relation to those of the stochastic model) are functional under high hold conditions, and low switch rates are functional under low hold conditions. The pigeons in our experiments appeared to have been sensitive to these differences, that is, to differential reinforcement for switching versus repetition. This sensitivity then skewed the otherwise stochastic process of response generation.

But the birds were not sensitive to momentarily maximum probabilities of individual reinforcers. That is, they did not learn to repeat (or even approximate) the single sequence that would be reinforced most frequently, presumably because they could not discriminate relatively high overall rates of reinforcement for one sequence in comparison with others. It therefore appears that when reinforcers are uncertain, as is the case under most concurrent-reinforcement and probability-learning situations, responding is stochastically distributed according to power-function relationships. However, when an organism can discriminate higher versus lower likelihood of reinforcement contingent upon particular responses or response strategies (as in reinforcement for switching vs. repetition), then responses favor the best possibility for reinforcement.

Note that this analysis implies that the variables controlling switch versus repetition differ from those controlling overall (or molar) choice distributions. Under the present three-key procedure, these two aspects of behavior—switching and overall choice distribution—could, to a large extent, vary independently of one another. Using simulations, we found that switch versus repetition proportions could change over a large range without appreciably affecting distributions of choices, these being controlled, in our simulations, by relative frequencies of reinforcement. Multiple operanda effects may differ from the two-operandum procedures most commonly used in concurrent-reinforcement studies in which high switch rates generally lead to flat choice distributions, that is, to undermatching. More generally, as response options increase, switch rates (nonrepetitions) have less and less of an effect on choice distributions.

We therefore conclude that the procedures used to study choice do matter: Procedures influence behaviors. Nevertheless, we also conclude that across a wide array of procedures spanning the range of hold values from probability learning to concurrent reinforcement, a single set of principles will account for the behaviors. Hold influenced frequencies and distributions of obtained reinforcers. In benign environments, in which reinforcers await collection indefinitely, reinforcers are often experienced as frequently as they are available. Under less favorable conditions, under which previously available reinforcers can be lost (perhaps because of competition, spoilage, or random scatter), reinforcers are experienced less frequently, and distributions are skewed. These differences in experienced reinforcers are partly determined by hold, which in turn directly affects choice. In addition, hold influenced the consistency of reinforcer distributions. Under concurrent procedures (h = 1.0), the flow of reinforcers was relatively constant, and 1:1 matching—choices to reinforcers—was observed. Under probability-learning conditions, reinforcer distributions were more variable, and choices were distributed more equally across alternatives. However, in both cases, choices were related to reinforcers by power functions. Hold values also influenced whether switches or repetitions were differentially reinforced. Under hold = 1.0, switches were more likely to be reinforced than were repetitions, whereas under hold = 0.0, repetitions were differentially favored.

Four explanatory principles, applicable across all values of hold, therefore account for our results:

When reinforcer availability is uncertain, choices are emitted stochastically.

Choice distributions vary as a power function of obtained reinforcer distributions.

When reinforcer distributions are relatively consistent (unchanged by responses or passage of time), the exponent of the function approaches 1.0 (1:1 matching).

When differential availability of reinforcers can be discriminated (e.g., because of differential reinforcement of switching vs. repetition), choices are directed preferentially to the most likely reinforced alternative.

A final point concerns the procedures used. We combined aspects of concurrent-reinforcement and probability-learning procedures under a Concdep3RR schedule (three-key dependent random ratios). The schedule was response driven rather than time driven (similar to probability-learning schedules), but instead of reinforcers being momentarily available, they were retained for some period depending on the value of hold. In a study of baseline performance, the hold parameter was 1.0, creating an analog to concurrent VI schedules: Reinforcers, once available, were retained until collected. When we systematically varied probabilities of reinforcer set-up in that experiment, the results were orderly and rapidly obtained: Pigeons consistently matched proportions of responses to proportions of obtained reinforcers. We recommend this procedure for future analyses of the effects on choice of other variables, such as reward qualities and magnitude, motivation, and drugs, and for human applications.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Research Grant MH068259 from the National Institutes of Health. We thank Jacob Rothstein for his able assistance with data analyses and discussion; Jerry Shurman, professor of mathematics at Reed College, for providing Equations 1 and 6 and their derivations; Peter Killeen for his helpful suggestions; and Gene Olson for assistance with animal care.

Appendix A

Derivation of Equations 1 and 6

Deriving Equation 1

The probability of receiving reinforcement depends on the probability of reinforcer availability for each response. Equation 1 calculates the function fn, where

Think of reinforcer set-up as an iterative process, with n−1 the number of responses intervening between a response and its prior occurrence. An immediate reiteration is assigned a lag of n = 1. Values for n greater than 1 indicate how many responses ago k was last selected. In sequence LRRX, for example, for X = R, n = 1; for X = L, n = 3.

The initial conditions for this equation are simple: Immediately after a response to key k, the probability of reinforcer set-up (Rk) is the only factor determining reinforcer availability. We define Rk as

As the given of the contingency, prior to response 1, a reinforcer (if available) will have been collected, and the key will now be empty. Consequently, at response 1 the probability of a reinforcer being available is simply the probability of a reinforcer setting up:

At response n + 1, if a reinforcer was available (fn), then it remains available and will remain so until obtained. If a reinforcer was not available (1 − fn), then a new reinforcer has a chance to set up (Rk). The sum of the probabilities of these two exclusive events gives the probability of a reinforcer being available for response n + 1:

The construction of this equation is clarified in the top half of Figure A1. Prior to response n + 1, there are two possibilities: that a reinforcer was available at response n (indicated with a 1) or was not available (indicated with a 0). The probability of each of these—fn and (1 − fn), respectively—is indicated on the incoming arrow. The probability of each end state can be determined by calculating the product of the probabilities leading to that state, and the overall probability that a reinforcer is available at response n + 1 can be determined by taking the sum of all end states resulting in reinforcement.

Figure A1.

Chart showing the probability of reinforcement at response n+1. Each circle represents a state of the contingency: Those marked 1 indicate that reinforcement is available, and those marked 0 indicate not available. For each state of the contingency, the downward leading arrows indicate the probability of the contingency moving to another state (the outgoing arrows always sum to 1.0). For details, see the text.

The above equation can be rewritten as

This reveals that the process is a first-order linear recurrence of the following form:

First-order linear recurrences can be reduced to

Replacing x with 1 − rk and canceling like terms gives Equation 1 in the text:

Deriving Equation 6

Equation 6 is more complicated to derive than Equation 1 because it introduces a new variable that makes the equation more general. The initial conditions are much the same:

However, Equation 6 introduces the hold variable h. We define h as

Thus, in our procedure, determining whether a reinforcer is available for response n + 1 requires not only knowing whether a reinforcer is available, but also knowing if a previously available reinforcer has disappeared and, if so, whether it has set up again. If no reinforcer is available, which happens with probability 1 − fn, then Rk determines whether a new reinforcer sets up, as before. If, on the other hand, a reinforcer is available (fn), then there are two possibilities: with probability h the reinforcer remains available, and with probability 1 − h it is lost, with the reinforcer having another chance of setting up, which happens with probability Rk:

This process is drawn in the bottom half of Figure A1. Once again, response n+1 begins with two possible starting states: reinforcer available or reinforcer not available. Two end states produce no reinforcement: one in which a reinforcer was not available to begin with and fails to set up, and another in which an existing reinforcer disappears and does not set up again. The other three possible end states (indicated by the circles marked 1) produce reinforcement. Again, the probability of each end state can be determined by calculating the product of the probabilities along the path leading to it, and the overall value for fn+1 is the sum of all end-state probabilities resulting in reinforcement.

This iterative equation constitutes a first-order linear recurrence:

We can simplify this further because

Thus

The resulting general equation is

This, in turn expands out to Equation 6:

Setting h to a value of 1.0 reduces Equation 6 to Equation 1. Thus, Equation 6 is the general form of both equations across our experiments.

Appendix B: Procedural Diagram for Experiment 2

Figure B1 outlines a possible series of events in Experiment 2 to demonstrate the way the Concdep3RRh contingency functions. In this outline, a solid circle represents a key that, if chosen, would provide reinforcement. In other words, solid circles show which responses could be reinforced. At the top of the example, a reinforcer awaits collection on Key R, but not on Keys L or M. The following chain of events unfolds:

Figure B1.

Flow chart of reinforcement contingencies in Experiments 2, 3, and 4.

The hold test is applied to Key R, and the reinforcer remains. This test is not applied to Keys L and M, because they do not have reinforcers available.

The reinforcement set-up test is applied to Keys L and M. A reward sets up on Key L but not on Key M. Key R continues to have a reinforcer.

The subject responds to Key M and is not reinforced.

The hold test is applied to Keys L and R. The reinforcer on Key R remains, but the reinforcer on Key L disappears.

The reinforcement set-up test is applied to Keys L and M, and reinforcement sets up on both.

The subject responds to Key L, and receives reinforcement, removing it from the key.

A number of observations can be made about this example. Note that hold is tested before reinforcer set-up. This is important for two reasons. First, a reinforcer is always available for at least one response before disappearing, even when hold is set to 0.0. Second, it is possible for a reinforcer to disappear and be immediately replaced, as happens on Key L before the second response.

For a reward to remain available for an extended period, it must either repeatedly pass the hold test (as Key R does in this example) or be replaced immediately after it disappears (as Key L does). Because subjects have no way of knowing whether a reinforcer has been available for a long period or has just reappeared after being removed, it can be said that procedures with low hold values have a greater degree of uncertainty, even when the probabilities of reinforcer set-up are quite high.

Footnotes

An exception to this generalization occurs when correction procedures are used in probability-learning experiments: Available reinforcers must be collected for the experiment to continue, and this prevents subjects from getting trapped on any one of the alternatives. Such correction procedures sometimes result in probability matching (matching responses to programmed reinforcers; see Lehr & Pavlik, 1970), but since hold = 1.0 in these cases, owing to the fact that every trial ends with a reinforcer, they could just as well be described in terms of Herrnstein’s matching relationship between choices and obtained reinforcers.

References

- Aparicio CF, Cabrera F. Choice with multiple alternatives: The barrier choice paradigm. Mexican Journal of Behavior Analysis. 2001;27:97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Baum WM. Matching, undermatching, and overmatching in studies of choice. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1979;32:269–281. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1979.32-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelens H. Melioration and maximization of reinforcement minus costs of behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1984;42:113–126. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskist W, Morgan D. Competitive fixed-interval performance in humans. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1987;47:145–158. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1987.47-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison M, Krageloh CU, Fraser M, Breier BH. Maternal nutrition and four-alternative choice. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;87:51–62. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.12-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantino E. Behavior analysis and decision making. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1998;69:355–364. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1998.69-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantino E, Esfandiari A. Probability matching: Encouraging optimal responding in humans. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2002;56:58–63. doi: 10.1037/h0087385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, King AP, Gottlieb D, Balci F, Papachristos EB, Szalecki M, Carbone KS. Is matching innate? Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2007;87:161–199. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2007.92-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, Mark TA, King AP, Latham PE. The rat approximates an ideal detector of changes in rates of reward: Implications for the law of effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2001;27:354–372. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.27.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharib A, Gade C, Roberts S. Control of variation by reward probability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2004;30:271–282. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.30.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. On the law of effect. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1970;13:243–266. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1970.13-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ, Loveland D. Maximizing and matching on concurrent ratio schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1975;24:107–116. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1975.24-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ. In: The matching law. Rachlin H, Laibson DI, editors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman GM. A Markov model description of changeover probabilities on concurrent variable-interval schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1979;31:41–51. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1979.31-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen P, Shumway G. Concurrent random interval schedules of reinforcement. Psychonomic Science. 1971;25:155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth DE. The art of computer programming. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lau B, Glimcher PW. Dynamic response-by-response models of matching behavior in rhesus monkeys. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2005;84:555–579. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.110-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Conroy ML, McGreevy BP, Barraclough DJ. Reinforcement learning and decision making in monkeys during a competitive game. Cognitive Brain Research. 2004;22:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr R, Pavlik WB. Within-subjects procedural variations in two-choice probability learning. Psychological Reports. 1970;26:651–657. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonall J. Concurrent variable-ratio schedules: Implications for the generalized matching law. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1988;50:55–64. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonall J. A local model of concurrent performance. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1999;71:57–74. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1999.71-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado A. Behavioral variability and frequency-dependent selection. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1992;58:2341–2263. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1992.58-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh NJ. The psychology of animal learning. New York: Academic Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Manabe K, Staddon JER, Cleaveland JM. Control of vocal repertoire by reward in Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1997;111:50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Meisch RA, Spiga R. Matching under non-independent variable-ratio schedules of drug reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1998;70:23–34. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1998.70-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse WH. Intermittent reinforcement. In: Honig WK, editor. Operant behavior: Areas of research and application. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1966. pp. 52–108. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JL, Lohmeier JH, Well AD. Modeling probabilistic categorization data: Exemplar memory and connectionist nets. Psychological Science. 1994;5:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nevin J. Interval reinforcement of choice behavior in discrete trials. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1969;12:875–885. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]