Abstract

Exposure to elevated levels of manganese has been shown to cause neuronal damage in the midbrain and the development of Parkinsonian symptoms. Activation of microglia and release of neurotoxic factors in particular free radicals are known to contribute to neurodegeneration. We have recently reported that manganese chloride (MnCl2) stimulates microglia to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). The aim of this study is to determine the role of microglia in the MnCl2-induced degeneration of dopaminergic (DA) neurons that are particularly vulnerable to oxidative insult. MnCl2 (10–300 μM; 7 days) was markedly more effective in damaging DA neurons in the rat mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures than the neuron-enriched (microglia-depleted) cultures. In addition, the microglia-enhanced MnCl2 toxicity was found to be preferential to DA neurons. The microglial enhancement of DA neurotoxicity was further supported by the observation that replenishment of microglia to the neuron-enriched cultures significantly increased the susceptibility of DA neurons to the MnCl2-induced damage. Analysis of the temporal relationship between microglial activation and DA neurodegeneration revealed that MnCl2-stimulated microglial activation preceded DA neurodegeneration. Mechanistically, MnCl2 (10–300 μM) stimulated a concentration- and time-dependent robust production of ROS and moderate production of nitric oxide but no detectable release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta. Application of free radical scavengers including superoxide dismutase/catalase, glutathione, N-acetyl cysteine and an inhibitor of nitric oxide biosynthesis significantly protected DA neurons against the MnCl2-induced degeneration. These results demonstrate that microglial activation and the production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen free radicals promote the MnCl2-induced DA neurodegeneration.

Keywords: manganese, neurotoxicity, dopamine neuron, microglia, reactive oxygen species, nitric oxide, cytokines, midbrain

Introduction

Manganese is an essential trace metal that plays important roles in various biological processes. However, exposure to excessive levels of manganese, in particular in certain occupational settings such as mining and welding is known to cause neuronal damage in the midbrain and result in the development of Parkinsonian movement abnormalities (Aschner et al., 2007; Cersosimo and Koller, 2006). In addition, a number of epidemiological studies have implicated that elevated environmental or chronic occupational exposure to manganese may contribute to the development of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (PD), a degenerative movement disorder resulting from a progressive degeneration of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic (DA) pathway (Finkelstein and Jerrett, 2007; Gorell et al., 1997; Gorell et al., 1999; Racette et al., 2001; Racette et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2003).

Research in the last two decades has provided increasing evidence suggesting that neurodegeneration especially DA neurodegeneration induced by various environmental and experimental toxicants involves the active participation of glial cells in the brain (Liu and Hong, 2003; McGeer and McGeer, 2008; Przedborski, 2007). Microglia and astroglia are the primary brain glial cells of which astroglia play a key role in providing neurotrophic support and maintaining the homeostasis that are crucial to the survival and function of neurons (Aloisi, 1999). Microglia, on the other hand, are the resident immune cells in the brain and play a vital role in immune surveillance and injury repair (Kreutzberg, 1996). However, upon exposure to toxicants, both microglia and astroglia can either be directly activated by agents such as bacterial endotoxin or become activated in response to neuronal injuries inflicted by the toxicants that include neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine and pesticide rotenone (Liu, 2006). Activated glial cells produce a variety of proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors that include cytokines, free radicals and lipid mediators that work in concert to induce and/or exacerbate neurodegeneration (Liu et al., 2003). Compared to astroglia, microglia respond to toxicant-induced insults via a faster activation kinetic and produce a wider array of neurotoxic factors suggesting a more prominent role for microglia in glial activation-mediated neurodegeneration (Liu et al., 2003).

DA neurons, especially the nigrostriatal DA neurons associated with PD pathogenesis, are particularly vulnerable to damage induced by various free radicals due to their innate characteristics that include reduced anti-oxidant capacity, high content of oxidation-prone dopamine, potential mitochondrial defect, as well as their residing in an environment enriched in lipid and iron (Greenamyre et al., 1999; Jenner and Olanow, 1998). Furthermore, the midbrain region seems to have a particularly higher abundance of microglia than other regions of the brain (Kim et al., 2000; Lawson et al., 1990). Microglia are the primary source of extracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) including superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) including nitric oxide (NO) (Babior, 2004; Brown, 2007). Superoxide can combine with NO to form the highly deleterious peroxynitrite intermediate (Beckman and Crow, 1993). Hydrogen peroxide, on the other hand, can interact with free iron through the Fenton reaction to form the more deadly hydroxyl free radical. We have recently reported that treatment of rat primary microglia with MnCl2 leads to the increased production and release of oxygen free radicals (Zhang et al., 2007). This MnCl2-induced microglial ROS production may contribute to manganese neurotoxicity.

Considerable knowledge has been gained on the role of astroglia in manganese-induced neurotoxicity. Astroglia serve as the major homeostatic regulator and storage site for manganese in the brain (Aschner et al., 1999). Accumulation of manganese in astroglia, however, may interfere with their normal functions leading to an increased release of factors such as glutamate that may elicit excitatory neurotoxicity (Erikson and Aschner, 2003; Hazell, 2002). In addition, manganese has been shown to augment astroglial expression of the inducible NO synthase (iNOS) that is responsible for NO production and the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 that mediates the production of proinflammatory prostaglandins (Liao et al., 2007; Moreno et al., 2008).

The involvement of microglia in the manganese-induced neurotoxicity however remains poorly understood. In this study, using a variety of primary neuron-glia cultures, we aimed to characterize the contribution of microglia to manganese-induced neurodegeneration, in particular DA neuroegeneration and the involvement of potential factors, especially free radicals, in the neurodegenerative process.

Materials and methods

Animals

Timed-pregnant Fisher F344 rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. The rats were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility and kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. All animal-handling procedures were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All efforts were made to reduce distress and minimize suffering.

Primary rat ventral mesencephalic neuron-glia culture

Mixed neuron-glia cultures were prepared from gestation day 14 Fisher F344 rat embryos as previously described (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2000). Briefly, ventral mesencephalic tissues were harvested. Following a mild mechanical trituration, dispersed cells were seeded at 5 × 105/well to poly-D-lysine coated 24-well plates. Cultures were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in minimal essential medium (MEM, Invitrogen) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen) 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS, Invitrogen), 1 g/l glucose, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM nonessential amino acids, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Maintenance Media). Seven-day-old cultures were ready for treatment using MEM containing 2% FBS, 2% HS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Treatment Media). Immunochemical analysis indicated that cultures at the time of treatment contained approximately 50% astrocytes, 10% microglia and 40% neurons of which 2–3% were DA neurons.

Primary rat ventral mesencephalic neuron-enriched culture

Neuron-enriched cultures were prepared as previously described (Gao et al., 2002). Briefly, cytosine β-D-arabinocide (10 μM) was added 2 days after seeding to the primary mixed neuron-glia cultures prepared as described above to suppress glial proliferation. Seven-day-old cultures were ready for treatment using the same Treatment Media as that for the primary mixed neuron-glia culture. Cultures at the time of treatment were composed of approximately 8% astrocytes, 0.2% microglia and 90% neurons of which 1–2% were DA neurons.

Primary mixed glia culture

Mixed glia cultures were prepared from the brains of 1-day-old Fisher F344 rat pups as described (Liu et al., 2001). Briefly, whole brain tissues were harvested, triturated and seeded at 1 × 105/well to poly-D-lysine coated 96-well culture plates (for assays) or 2 × 107/flask to poly-D-lysine coated 150-cm2 culture flasks (for harvesting microglia). Cultures were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/nutrient mixture F12 (DMEM/F12, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM nonessential amino acids, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Culture media were changed 4 days after the initial seeding and cultures reached confluence in 12–14 days at which point the cultures contained approximately 15% microglia and 85% astrocytes.

Primary microglia culture

Primary microglia were prepared from the confluent mixed glia cultures grown in the 150-cm2 culture flasks as described (Liu et al., 2001). Briefly, the culture flasks were shaken for 2 hr at 150 rpm on an orbital shaker. Culture supernatants that contained the detached microglia were collected. Following centrifugation, microglia were resuspended in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were seeded at 5 × 104/well to poly-D-lysine coated 96-well culture plates and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Microglia cultures were used the following day for treatment. Immunocytochemical analysis indicated that the microglia were >98% pure (Liu et al., 2001).

Primary reconstituted microglia-neuron culture

To create the reconstituted microglia-neuron co-culture, primary rat microglia were added to the rat primary neuron-enriched cultures (Gao et al., 2002). Microglia were prepared as described above and were resuspended in the neuron-glia culture Maintenance Media and added to the neuron-enriched cultures the day before treatment.

Treatment with manganese chloride (MnCl2)

For each treatment, a fresh 1 M stock solution of MnCl2 (Fisher) was prepared using deionized and distilled water and sterilely filtered through a 0.2 μm syringe filter (Zhang et al., 2007). The 1 M stock solution was diluted with sterile de-ionized and distilled water to generate a series of secondary stock solutions that were 500 fold the desired final concentrations. An aliquot of the 500X secondary stock solution was then added to the Treatment Media to achieve the desired final concentration of MnCl2 for treatment. For controls, 2 μl of de-ionized and distilled water (vehicle) was added to each ml of Treatment Media (0.2% final concentration). Cells were treated with vehicle or MnCl2-containing Treatment Media at 0.1 ml and 1 ml/well for cells grown in 96 and 24-well culture plates respectively.

Immunocytochemistry

Following treatment, cultures were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% formaldehyde (20 min). After the inactivation of endogenous peroxidases (1% hydrogen peroxide, 10 min), cultures were blocked with appropriate normal serum-containing solutions followed by incubation (4°C, overnight) with primary antibodies against cell type-specific markers. The bound primary antibodies were visualized by incubation with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories), the Vectastain Elite ABC reagents (Vector Laboratories) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma) following our previously described protocols (Liu et al., 2000). Neuronal cell bodies and neurites were stained with a monoclonal ant-microtubule-associated protein-2 antibody (MAP-2, 1:500, Chemicon). Neuronal nuclei were stained with a monoclonal antibody against the neuron-specific nuclear protein (Neu-N, 1:1000, Chemicon). DA neurons were detected with a monoclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (TH, 1:500, Vector Laboratories). Microglia were detected with a monoclonal anti-complement type-3 receptor antibody (OX-42, 1:250, BD Pharmingen). Astrocytes were recognized with a monoclonal antibody against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1:500, Chemicon). Images were analyzed under an Olympus CKX41 inverted microscope and recorded with a Q-Imaging 3.3 MP CCD microscope camera using the Q-Capture Suite software (Quantitative Imaging).

Quantification of degeneration of dopaminergic neurons

The number of TH-immunoreactive (TH-ir) cells was visually counted under microscope as previously described (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2000). Each well of a 24-well culture plate was divided into four equal quadrants and the number of TH-ir neurons in two opposite quadrants was counted. TH-ir neurons in three sister wells for each treatment condition in each 24-well plate were counted. In addition, the overall neurite length for individual TH-ir neurons was determined as described (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2000). Fifty TH-ir neurons/well were randomly selected and images recorded. The total length of TH-ir neuritess for each of the selected TH-ir neurons was then determined. Cell counting and TH-ir neurite measurement were performed by three individuals blind to the treatment conditions.

Quantification of Neu-N-ir neurons and OX-42-ir microglia

The number of Neu-N-ir neurons or OX-42-ir microglia in 5 evenly distributed counting circles (1.13 mm2) in each well of the multi-well culture plates was counted under microscope. One of the counting circles was located at the center of the well and each of the remaining 4 counting circles in the center of each quadrant. Cells were counted by three individuals blind to the treatment conditions.

High affinity [3H]DA uptake

The capacity of the neuron-glia cultures to uptake DA, a functional parameter for dopaminergic neurons in the culture, was determined as previously described (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2000). Briefly, after treatment, the cultures in 24-well culture plates were rinsed twice with warm Krebs-Ringer buffer (KRB) made up of 16 mM sodium phosphate, 119 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.3 mM EDTA and 5.6 mM glucose (pH 7.4). The cultures were then incubated for 20 min at 37°C with 25 nM [3H]DA (30 Ci/mmol, NEN) mixed with unlabelled DA (1 μM final concentration). Afterwards, cultures were washed three times with ice-cold KRB, solublized with 1N NaOH and mixed with liquid scintillation fluid (Fisher) before the determination of radioactivity with a liquid scintillation counter (Packard). Non-specific binding was determined by the inclusion of mazindol (10 μM final concentration), a specific inhibitor of high affinity DA uptake. The difference in radioactivity observed in the absence and presence of mazindol of sister wells of the same treatment condition was considered high affinity DA uptake capacity.

Measurement of nitrite, TNFα and IL-1β

The production of nitric oxide (NO) was determined by measuring the accumulated level of its stable metabolite, nitrite, in the supernatant with the Griess reagent as previously described (Liu et al., 2000). The colorimetric nitrite assay had a detection limit of approximately 0.5 μM. The amounts of TNFα and IL-1β released into the supernatants were determined with respective rat enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits from R&D Systems with detection limits of 5 pg/ml following the manufacturer’s suggested protocols (Liu et al., 2000).

Analysis of ROS production

The production of ROS was determined with a fluorescent probe, 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA, Molecular Probes) as previously described (Gao et al., 2003; Mao et al., 2007). Briefly, cultures in 96-well culture plates were treated (100 μl/well, 4 wells/condition) with vehicle (water, 0.2% final concentration) or MnCl2 in phenol red-free DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 1% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. At desired time points, cultures were rinsed three times with phenol red-free Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS, Invitrogen) and then incubated for 1 hr at 37°C and 5% CO2 with 5 μM CM-H2-DCFDA in phenol red-free HBSS. Afterwards, fluorescence intensity was determined at 485 nm for excitation and 530 nm for emission using a Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments).

N27 cell viability assay

The immortalized rat N27 dopaminergic neuronal cell line, established from embryonic rat mesencephalon possesses the key characteristics of dopamine neurons (Clarkson et al., 1998). N27 cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% air in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. For cell viability assay, N27 cells were seeded at 5 × 104/well in 24-well culture plates and grown for 2 days to near confluence. Cells were then treated in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2% FBS (500 μl/well). Cell viability was determined using the formazan-forming MTT ((3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide)) reagent (Sigma) as previously described (Liu et al., 2001). Briefly, 50 μl of MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well. Following an incubation for 45 min at 37°C and 5% CO2, culture supernatants were completely removed and the cells were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (250 μl/well). The solublized formazan-containing solution (125 μl/well) was transferred to 96-well culture plates and absorbance at 550 nm was determined using a Synergy HT microplate reader.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical significance, data were analyzed with ANOVA followed by Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis using the StatView program (SAS Institute). A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Facilitation by glia of the MnCl2-induced degeneration of DA neurons in primary mesencephalic cultures

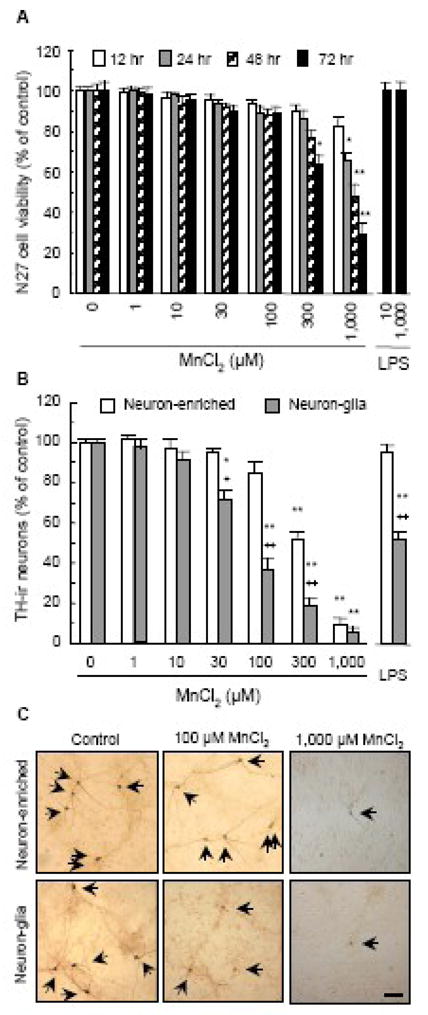

Direct effect of MnCl2 on neurons was first determined using a homogeneous population of the rat N27 DA neuronal cells. N27 cells were treated with vehicle (0.2% water) or 1–1000 μM MnCl2 for 12–72 hours. Viability of the N27 cells was then determined. As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment of N27 cells with 1–100 μM MnCl2 for 12–72 hours did not have any significant effect on their viability. In cells treated with 300 μM MnCl2, significant reduction in cell viability was observed only at the 72-hour time point, but not at the 12–48 hour time points (Fig. 1A). In cells treated with 1000 μM MnCl2, cell viability started to be significantly reduced 24 hours following treatment and continued to decrease in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Treatment of cells for 72 hours with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an inducer of glial activation-mediated DA neurodegeneration (Dutta et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2002), however, did not have any effect on the viability of N27 neuronal cells (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

The presence of glia promotes manganese DA neurotoxicity. A. Effect of MnCl2 on the viability of rat N27 DA neuronal cells. Cells were treated for indicated timed periods with vehicle control (0.2% water) or indicated concentrations of MnCl2. For comparison, N27 cells were treated for 72 hours with 10 and 1000 ng/ml LPS. Cell viability was determined as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control. Results are mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the timed-matched vehicle control (0). B. Comparison of the effect of MnCl2 on the loss of TH-ir neurons in primary neuron-glia and neuron-enriched cultures. Rat mesencephalic neuron-glia or neuron-enriched (and microglia-depleted) cultures were treated for 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water), indicated concentrations of MnCl2, or LPS (10 ng/ml). Following immunostaining with an anti-TH antibody, the number of TH-ir neurons in the cultures was quantified as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control. Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the vehicle control (0). +, p < 0.05; ++, p < 0.005 compared to the matching neuron-enriched cultures treated with the same concentration of MnCl2 as that for the neuron-glia cultures. C. Immunocytochemical analysis of the MnCl2-induced degeneration of TH-ir neurons in neuron-glia and neuron-enriched cultures. Following treatment for 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water), 100 μM MnCl2 or 1000 μM MnCl2, DA neuronal cell bodies and neurites were immunostained with an anti-TH antibody as described in the Materials and methods. Arrowheads: TH-ir neurons. Images presented are representative of four experiments. Scale bar: 100 μm.

To determine the contribution of glia to the MnCl2-induced DA neurotoxicity, rat primary mixed neuron-glia and neuron-enriched (i.e., microglia-depleted) cultures were treated for 7 days with 1–1000 μM MnCl2. Following immunostaining with an anti-TH antibody, the effect of MnCl2 treatment on the numbers of TH-ir neurons in the cultures was determined. As shown in Fig. 1B, treatment of the neuron-enriched cultures with up to 100 μM MnCl2 did not result in a significant loss of TH-ir neurons. In sharp contrast, treatment of the mixed neuron-glia cultures with concentrations of MnCl2 as low 30 μM led to a significant loss of TH-ir neurons (Fig. 1B). At 30–300 μM, MnCl2 was markedly more effective in inducing the loss of TH-ir neuron in neuron-glia cultures than in neuron-enriched cultures (Fig. 1B). At 1000 μM, MnCl2 was almost equally effective in damaging TH-ir neuron in both the neuron-glia and neuron-enriched cultures, causing a loss of approximately 90% of TH-ir neurons in the cultures (Fig. 1B). LPS (10 ng/ml), as a control, did not cause any significant loss of TH-ir in the neuron-enriched cultures (Fig. 1B), reminiscent to that observed in the N27 neuronal cells (Fig. 1A). However, LPS treatment caused a significant loss of TH-ir neurons in the neuron-glia cultures, consistent with previously reported findings (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002).

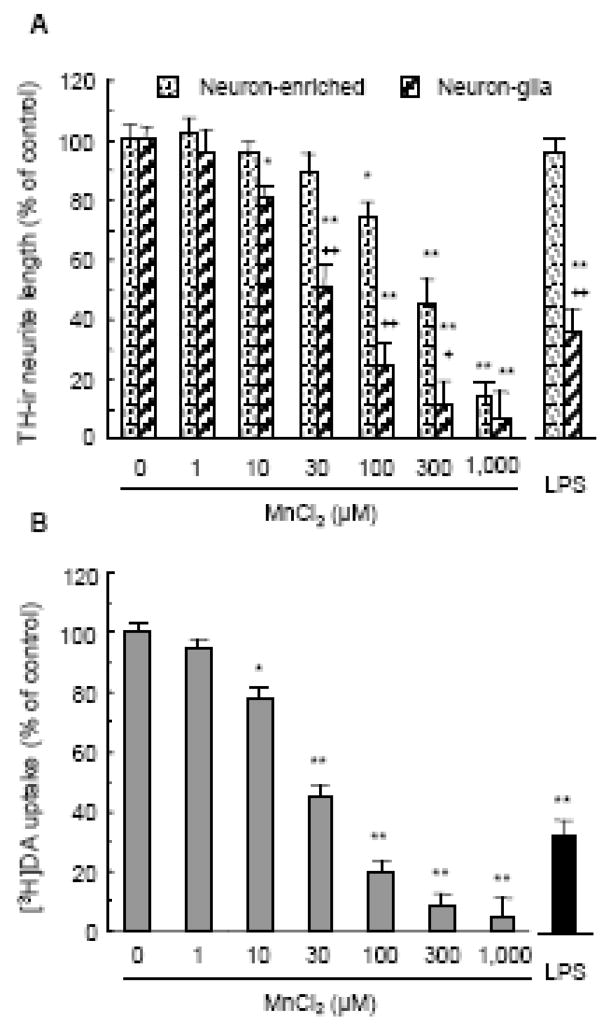

In addition to causing the destruction of TH-ir neuronal cell bodies, MnCl2-induced DA neurotoxicity resulted in the degeneration of TH-ir neurites in the survived TH-ir neurons and the impairment of their DA uptake capacity. Compared to the elaborate neuritic network of those in the control cultures, the neurites of the TH-ir neurons in the MnCl2-treated cultures were markedly shorter in length and fewer in number which was particularly evident in the MnCl2-treated neuron-glia cultures (Fig. 1C). Similar to the MnCl2-induced concentration-dependent loss of TH-ir neurons (Fig. 1B), reduction in TH-ir neurite length was more pronounced in the neuron-glia cultures than that in the neuron-enriched cultures with significant differences observed for 30–300 μM MnCl2 and 1000 μM equally effective in both cultures (Fig. 2A). More Important, in neuron-glia cultures, the structural integrity (as measured by TH-ir neurite length) and function (as measured by DA uptake capacity) of DA neurons in the cultures seemed to begin to be affected by treatment (7 days) with 1 μM MnCl2 and became significantly compromised by treatment with concentrations of MnCl2 as low as 10 μM (Fig. 2), although the loss of TH-ir neurons caused by the same concentration of MnCl2 was not statistically significant (Fig. 1B). LPS (10 ng/ml; 7 days), as a control, was ineffective in the neuron-enriched cultures but caused a 60–70% decrease in TH-ir neurite length and DA uptake capacity (Fig. 2), an observation consistent with previous reports (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002).

Fig. 2.

Manganese-induced structural and functional degeneration of DA neurons. A. Effect on TH-ir neurite length. Neuron-glia and neuron-enriched cultures were treated for 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water), indicated concentrations of MnCl2, or LPS (10 ng/ml). Following immunostaining with an anti-TH antibody, the neurite length of the TH-ir neurons in the cultures was quantified as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control (0). B. Effect on DA uptake capacity. Neuron-glia cultures were treated as described above and the high affinity [3H]DA uptake capacity was determined as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control (0). Results are mean ± SEM of three (B) or four (A) separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the vehicle control. +, p < 0.05; ++, p < 0.005 compared to the matching neuron-enriched cultures treated with the same concentration of MnCl2 as that for the neuron-glia cultures.

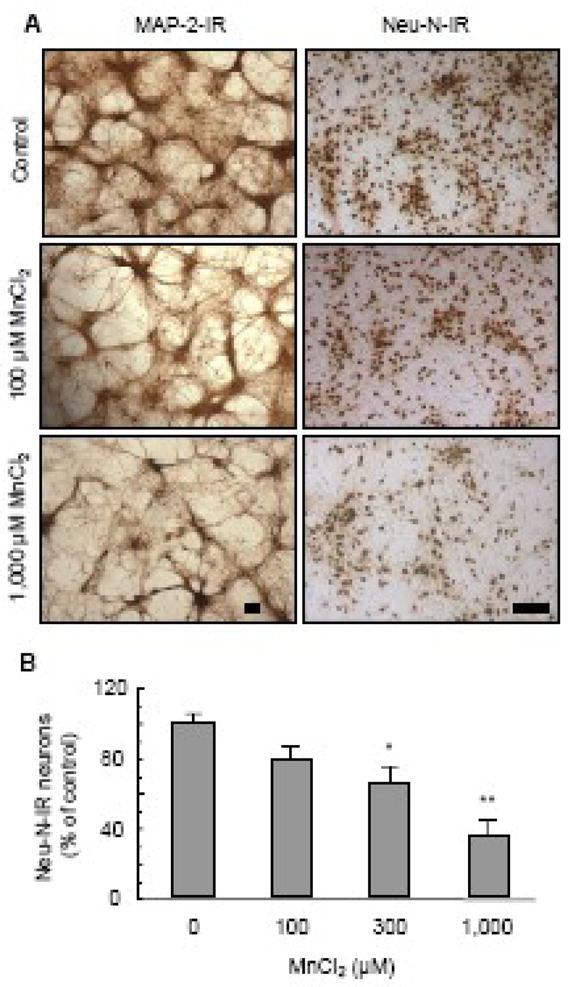

MnCl2-induced preferential degeneration of DA neurons in primary neuron-glia cultures

To determine whether MnCl2 was equally effective in damaging DA and non-DA neurons in the neuron-glia cultures, cultures were treated for 7 days with vehicle (0.2% water), 100, 300 or 1000 μM MnCl2. Cultures were then immunostained with antibodies against Neu-N for neuronal nuclei and MAP-2 for neuronal cell bodies and neurites of all types of neurons (Fig. 3A). Quantification of the Neu-N-ir neurons indicated that treatment with 100 μM MnCl2 resulted in a modest yet statistically insignificant reduction (20%) in the number of Neu-N-ir neurons (Fig. 3B), compared to a 64% loss of TH-ir neurons (Fig. 1B). While treatment with 1000 μM MnCl2 led to a nearly complete loss (95%) of TH-ir neurons (Fig. 1B), compared to only a 65% loss of Neu-N-ir neurons (Fig. 3B). Similarly, MnCl2 treatment was less effective in inducing the degeneration of the neuritic network of MAP-2-ir neurons (Fig. 3A) than that of the TH-ir neurons (Figs. 1C & 2).

Fig. 3.

Preference of manganese-induced neurodegeneration. Neuron-glia cultures were treated for 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water) or indicated concentrations of MnCl2. Neurons were immunostained with an anti-MAP-2 and anti-Neu-N antibody hat recognizes neuronal cell bodies and neurites and neuronal nuclei of all neurons respectively. A. Immunocyctochemical analysis of MAP-2-ir and Neu-N-ir neurons. Images presented are representative of four experiments. Scale bar: 100 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of the effect of MnCl2 on Neu-N-ir neurons. Following immunostaining, the number of Neu-N-ir neurons in the cultures was quantified as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control. Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the vehicle control (0).

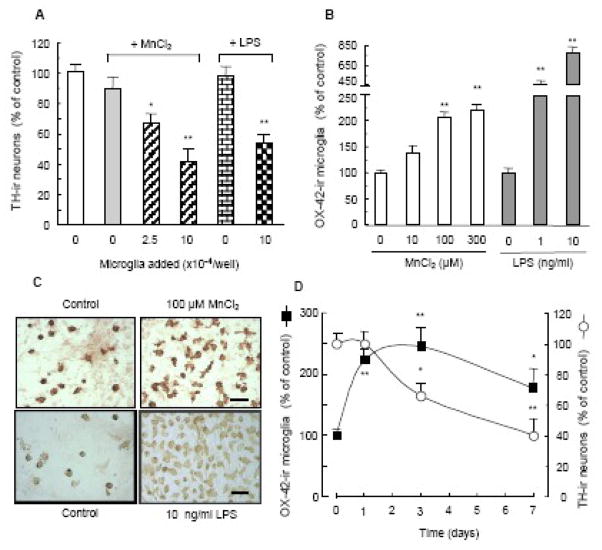

Microglial activation promotes the MnCl2-induced DA degeneration

To determine the contribution of microglia to the MnCl2-induced preferential DA neurodegeneration in the neuron-glia cultures, we first determined DA neurotoxicity of MnCl2 in a reconstituted neuron-microglia culture system. As shown in Fig. 4A, addition of microglia back to the neuron-enriched (microglia-depleted) cultures rendered MnCl2 (100 μM, 7 days) effective in causing a significant loss of TH-ir neurons. The microglia replenishment-enabled MnCl2 DA neurotoxicity was dependent on the number of microglia added to the neuron-enriched cultures (Fig. 4A). The magnitude of MnCl2 (100 μM; 7 days)-induced loss of TH-ir neurons in the neuron-enriched cultures replenished with 1×105 microglia/well (Fig. 4A) was comparable to that observed in the neuron-glia culture under the same treatment condition (Fig. 1B). As a control, LPS was totally in effective in damaging DA neurons in the neuron-enriched cultures but became very efficient following microglia replenishment (Fig. 4A). These results suggested that microglia were the key contributor to the observed glia-enhanced MnCl2 DA neurotoxicity (Figs. 1 & 2).

Fig. 4.

Contribution of microglia to manganese-induced DA neurodegeneration. A. Effect of microglia replenishment to neuron-enriched cultures on the MnCl2-induced DA neurodegeneration. Neuron-enriched cultures were reconstituted with indicated numbers of microglia and then treated for 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water), 100 μM MnCl2, or LPS (10 ng/ml). Following immunostaining, the number of TH-ir neurons in the cultures was quantified as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control. Results are mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the control (0, open bar). B. Effect of MnCl2 on microglia abundance in neuron-glia cultures. Cultures were treated with vehicle control (0.2% water) or indicated concentrations of MnCl2 or LPS. One day later, cultures were immunostained for microglia with the OX-42 antibody. Microglia in the cultures were quantified as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control. Results are mean ± SEM of three (for LPS) or four (for MnCl2) separate experiments performed in triplicate. p < 0.005 compared to the control (0). C. Representative immunocytochemical analysis of OX-42-ir microglia from B. Scale bar: 50 μm. D. Time courses for MnCl2-induced microglial activation and DA neurodegeneration in neuron-glia cultures. Cultures were treated for 1, 3 or 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water) or 100 μM MnCl2. Following immunostaining, the numbers of OX-42-ir microglia and TH-ir neurons in the cultures were quantified as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the control. Results are mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the control (0).

Next, we determined whether MnCl2 treatment was capable of inducing microglial activation in the neuron-glia cultures. Cultures were treated with 10–300 μM MnCl2, the range of MnCl2 concentrations that induced glia-enhanced DA neurodegeneration (Figs. 1 & 2). Afterwards, microglia in the cultures were identified by immunostaining with the OX-42 antibody that detected the expression of complement type-3 receptor and the number of OX-42-ir microglia was counted. As shown in Fig. 4B, a concentration-dependent increase in the number of OX-42-ir microglia was observed in cultures treated for 1 day with MnCl2. Compared to the vehicle-treated control cultures, the number of OX-42-ir microglia in cultures treated with 100 μM and 300 μM MnCl2 increased by 105% and 120% over the control respectively (Fig. 4B). In addition to the increase in numbers, the OX-42-ir microglia in the MnCl2 (100 μM)-treated neuron-glia cultures were markedly larger in size than that in the vehicle-treated control cultures and transformed from mostly round to rod-like and multi-polar in morphology, characteristic of activated microglia in vitro (Fig. 4C) (Liu et al., 2000). Compared to the one-fold increase in the MnCl2-treated neuron-glia cultures, a 3.6 and 6.8 fold increase in OX-42-ir microglia was observed in cultures treated respectively with 1 and 10 ng/ml LPS, a potent activator of immune cells (Fig. 4B). In addition, the LPS-activated OX-42-ir microglia exhibited the characteristic morphology of fully activated microglia in vitro (Fig. 4C) (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2002).

We then determined the temporal relationship between the MnCl2-induced microglial activation and DA neurodegeneration. Neuron-glia cultures were treated with vehicle (0.2% water) or 100 μM MnCl2 for 1, 3 and 7 days and the cultures were immunostained for OX-42-ir microglia and TH-ir neurons. At day 1 and 3, the number of OX-42-ir microglia in the MnCl2-treated neuron-glia cultures was 220% and 246% of that of the control culture respectively (Fig. 4D). By day 7, the number of OX-42-ir microglia in the MnCl2-treated cultures subsided but remained significantly elevated over that of the control culture (Fig. 4D). In the meantime, 1 day following treatment with 100 μM MnCl2, loss of TH-ir neurons was not evident compared to the control cultures (Fig. 4D). However, by day 3, the number of TH-ir neurons in the MnCl2-treated cultures decreased to 66% of the control and by day 7 to 40% of the control (Fig. 4D).

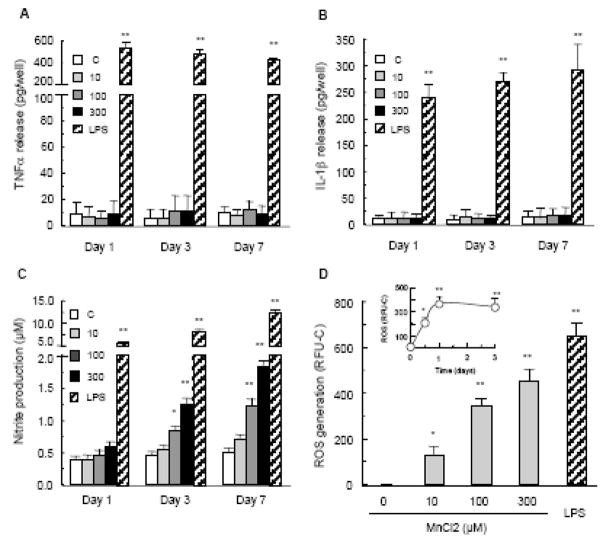

Effect of MnCl2 on the generation of proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors

Free radicals including ROS and RNS and proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα and IL-1β are important mediators of activated glia, especially microglia-mediated DA neurodegeneration (Liu, 2006). As shown in Fig. 5, compared to the vehicle-treated control cultures, no significant release of either TNFα or IL-1β was detected in the supernatants of the neuron-glia cultures treated with 10–300 μM for 1, 3 or 7 days. In contrast, robust production of both TNFα and IL-1β was detected in cultures treated with 10 ng/ml LPS (Figs. 5A & 5B), consistent with our previous reports (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2000).

Fig. 5.

Involvement of cytokines and free radicals in manganese-induced DA neurotoxicity. Effect of MnCl2 on the production of TNFα (A) and IL-1β (B). Neuron-glia cultures were treated with vehicle control (0.2% water) or indicated concentrations of MnCl2 or LPS (10 ng/ml). At the indicated time points, culture supernatants were harvested and the levels of TNFα and IL-1β were determined as described in the Materials and methods. Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in triplicate. **, p < 0.005 compared to the time-matched vehicle control (C). C. Effect of MnCl2 on NO production. Neuron-glia cultures were treated with vehicle control (0.2% water) or indicated concentrations of MnCl2 or LPS (10 ng/ml). At the indicated time points, culture supernatants were harvested and levels of nitrite (an indicator of NO production) were determined as described in the Materials and methods. Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the time-matched vehicle control (C). D. Effect of MnCl2 on ROS production. Primary mixed glia cultures were treated for 1 day with vehicle control (0.2% water), indicated concentrations of MnCl2, or 10 ng/ml LPS. ROS generation was determined as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as relative fluorescent units minus the control (RFU-C). Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the control (0). Inset: time course for MnCl2-induced ROS production. Primary mixed glia cultures were treated for 0.5, 1, or 3 days with vehicle control (0.2% water) or 100 μM MnCl2 and ROS production was measured and expressed as RFU-C. Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in quadruplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the control (0)

The accumulation of nitrite in the culture supernatants was an indicator of the production of NO by iNOS of glial cells in the cultures (Liu et al., 2002). As shown in Fig. 5C, treatment with MnCl2 (10–300 μM) resulted in a concentration- and time-dependent accumulation of nitrite in the neuron-glia cultures. At day 1, MnCl2-induced increase in NO production was modest yet statistically insignificant compared to the vehicle control. By day 3, NO production induced by treatment with 100 and 300 μM MnCl2 was significantly greater than the vehicle-treated control cultures. The MnCl2 (100–300 μM)-induced NO production further elevated by day 7 and remained significantly greater than the control cultures (Fig. 5C). LPS (10 ng/ml), on the other hand, induced a robust production of NO at day 1 and the LPS-induced NO production remained highly elevated at day 7 (Fig. 5C).

The effect of MnCl2 on the production of ROS was first determined in the mixed glia cultures. Treatment with 100 μM MnCl2 induced a rapid increase in glial ROS generation and significant ROS generation was observed as early as 12 hours following MnCl2 treatment (Fig. 5D). MnCl2-induced glial ROS generation reached the maximum at day 1 and remained at a plateau by day 3 (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, the MnCl2-induced glial ROS generation was dependent on the concentration of MnCl2 and significant ROS generation was observed in glial cultures treated for 1 day with concentrations of MnCl2 as low as 10 μM (Fig. 5D). Compared to the MnCl2 used, LPS at 10 ng/ml was the most potent stimulator of ROS generation in mixed glia cultures (Fig. 5D).

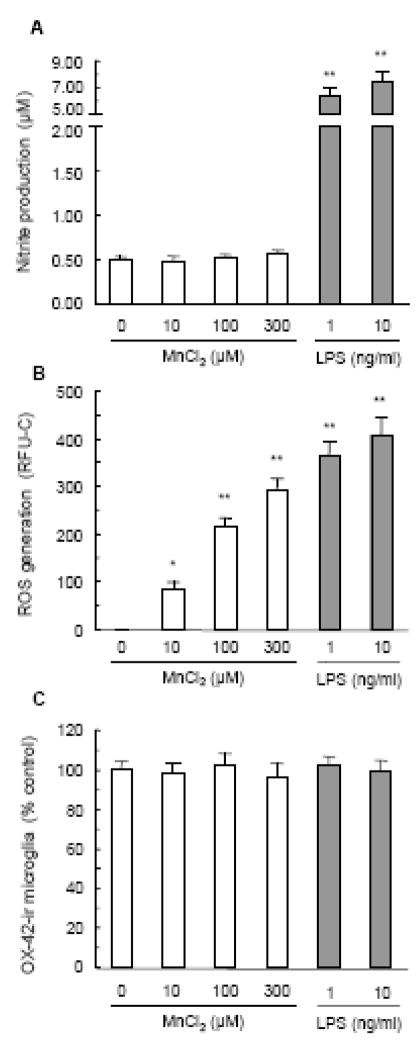

Next, we determined the effect of MnCl2 on NO production, ROS production and proliferation of microglia using primary rat microglia-enriched cultures. Microglia, as immune cells in the brain readily respond to various stimuli and produce a variety of proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors such as free radicals and cytokines (Liu et al., 2003; McGeer and McGeer, 2008). Treatment of microglia cultures for 1 day with 10–300 MnCl2 however, did not result in significant production of NO as measured by the accumulation of nitrite (Fig. 6A). No significant nitrite production was observed in cultures treated for longer periods of time (up to 72 hours) (data nor shown). LPS, as expected, potently stimulated NO production and 1 ng/ml of LPS was as effective as 10 ng/ml LPS in stimulating microglial NO production (Fig. 6A) (Liu et al., 2002). Contrary to the lack of effect on stimulating microglial NO production, MnCl2 was very effective in stimulating ROS production in microglia and the magnitude of increases in ROS production in MnCl2-stimulated microglia (Fig. 6B) were comparable to that in mixed glia (Fig. 6C). Again, LPS at 1 ng/ml was as potent of 10 ng/ml in stimulating microglial ROS production (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, treatment for 24 hr with either MnCl2 (10–300 μM) or LPS (1–10 ng/ml) did not have any significant effect on the number of microglia in the cultures (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Effect of manganese on microglial NO production, ROS generation and proliferation. Primary microglia were treated for 1 day with vehicle control (0.2% water) or indicated concentrations of MnCl2 or LPS. Culture supernatants were harvested for the determination of nitrite levels (A). Microglial ROS production was measured as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as RFU-C (B). Results in A and B are mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed in triplicate. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.005 compared to the vehicle control (0). C. Effect on microglial abundance. Microglia were treated as described above and immunostained with the OX-42 antibody. The number of OX-42-ir microglia was counted as described in the Materials and methods and expressed as a percentage of the vehicle control. Results are mean ± SEM of three separate experiments performed in triplicate.

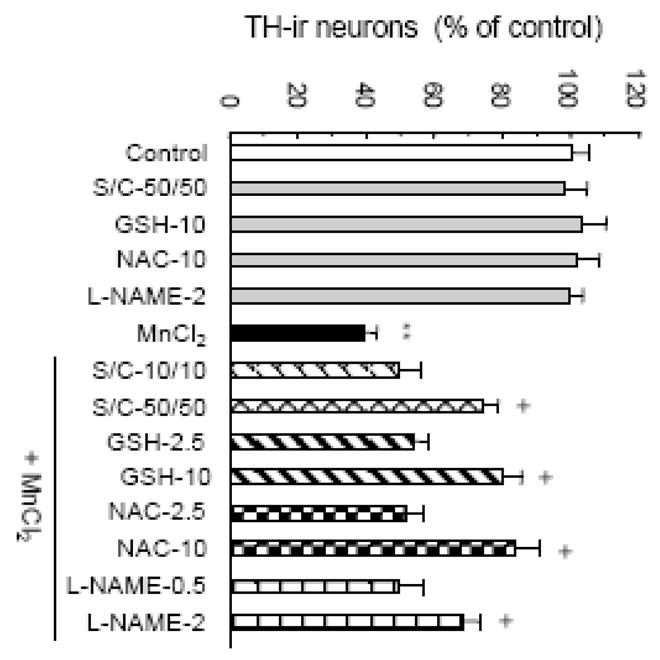

Involvement of free radical generation in the MnCl2-induced DA neurodegeneration

To investigate the relationship between MnCl2-induced glial free radical generation and DA neurodegeneration, we determined the effect of ROS scavengers and inhibition of NO biosynthesis on the MnCl2-induced DA neurodegeneration in neuron-glia cultures. Cultures were treated with superoxide dismutase (SOD)/catalase, glutathione methyl ester (GSH), the GSH biosynthesis precursor N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), or the NOS inhibitor L-NG-nitro-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) prior to treatment for 7 days with 100 μM MnCl2. As shown in Fig. 7, addition of SOD/catalase, GSH, NAC or L-NAME significantly reduced the MnCl2-induced loss of TH-ir neurons in the cultures while treatment with the scavengers/inhibitor alone did not have any significant effect on the number of TH-ir neurons in the cultures.

Fig. 7.

Effect of ROS scavenging and NOS inhibition on the manganese-induced DA neurodegeneration. Neuron-glia cultures were treated for 7 days with vehicle control (0.2% water) or 100 μM MnCl2. Thirty minutes prior to, 1 and 3 days after MnCl2 treatment, indicated concentrations of SOD/catalase (S/C, units/ml), GSH (mM) or NAC (mM) were added. L-NAME (mM) was added 30 minutes prior to the MnCl2 treatment. As controls, cultures were treated with the scavengers and L-NAME alone. Cultures were immunostained and TH-ir neurons were quantified as described in the Materials and methods. Results are mean ± SEM of four separate experiments performed in triplicate. **, p < 0.005 compared to the control. +, p < 0.05 compared to the MnCl2-treated cultures.

Discussions

In this study, we have demonstrated that microglia actively participate in the manganese-induced DA neurodegenerative process by facilitating a preferential degeneration of DA neurons in the primary rat mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures. Analysis of the MnCl2-induced DA neurodegeneration in the neuron-enriched (i.e., microglia poor) and mixed neuron-glia (microglia abundant) cultures indicates that the ability for glial, especially microglial cells to facilitate DA neurodegeneration is dependent upon the concentrations of MnCl2. At 1000 μM, MnCl2 was directly toxic to DA neurons as evidenced by its equal toxicity to DA neurons in both the neuron-enriched and neuron-glia cultures (Figs. 1 & 2). At 10 or 30 μM, MnCl2 required the presence of glia, especially microglia to exert its toxicity to DA neurons in the primary cultures (Figs. 1 & 2). In pure populations of immortalized neuronal cells that were totally devoid of any glial cells, MnCl2 was even less toxic than in neuron-enriched cultures that had a residual presence of microglia (0.2%) as demonstrated by this (Fig. 1A) and other studies (Kitazawa et al., 2005; Latchoumycandane et al., 2005). Between microglia and astroglia, microglia appear to be the predominant contributor to the glia-enhanced manganese DA neurotoxicity. First, the vulnerability of DA neurons to the MnCl2-induced toxicity (10–300 μM; 7 days) was directly correlated with the abundance of microglia in the neuron-glia cultures (10% microglia) and neuron-enriched cultures (0.2% microglia) (Figs. 1 & 2). Second, reconstitution of microglia with the neuron-enriched cultures restored the sensitivity of DA neurons in the culture to MnCl2- induced damage (Fig. 4A). In contrast, co-cultures of astroglia and neurons remained as insensitive as neuronal cultures to MnCl2 toxicity (50 μM; 5 days) (Spranger et al., 1998). Third, MnCl2 induced a concentration-dependent increase in the number of immunoreactive microglia in the neuron-glia cultures (Figs. 4C & 4D) and this MnCl2-induced increase in the abundance of immunoreactive microglia preceded the MnCl2-induced loss of DA neurons (Fig. 4D).

Microglia are the resident immune cells in the brain and readily become activated in response to infection, injury and the presence of a variety of foreign substances including environmental toxicants (Kreutzberg, 1996; Liu and Hong, 2003). Activation of microglia involves upregulation of cell surface receptors, morphological transformation and the expansion of microglial population through proliferation. In this study, treatment of the mixed neuron-glia cultures with MnCl2 resulted in a time and concentration-dependent increase in the number of microglia that were immunochemically positive for the expression of complement-3 receptor although this MnCl2-stimulated increase in the number of OX-42-ir microglia was modest in intensity compared to that induced by LPS, a known potent activator of immune cells (Figs. 4B & 4C). Nevertheless, the effect of MnCl2 on increasing the abundance of OX-42-ir microglia in neuron-glia cultures was reminiscent of that observed for the pesticide rotenone where microglia was found to enhance the rotenone-induced DA neurotoxicity (Gao et al., 2002; Sherer et al., 2003). Interestingly, this MnCl2-induced increase in the abundance of OX-42-ir microglia was not observed in the microglia-enriched cultures (Fig. 6C). This absence of an effect in the microglia-enriched cultures was not unique to MnCl2 because LPS (1 and 10 ng/ml) did not have any effect on the number of microglia in the cultures either (Fig. 6C). In fact, treatment of microglia-enriched cultures with higher concentrations of LPS than that used in this study has been shown to suppress microglial proliferation and LPS-induced over-activation may even result in microglial apoptosis presumably to restrict potential bystander neuronal damage (Brown et al., 1998; Ganter et al., 1992; Liu et al., 2001). In the MnCl2 and LPS-treated neuron-glia cultures, the increased number of OX-42-ir microglia observed in this study may be partly due to the increased expression of surface receptors in activated microglia. Microglia in the control neuron-glia cultures may have a low surface expression of OX-42-ir receptors due to the suppression by neurons (Carnevale et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2000). Activation causes an upregulation of surface receptors and hence enhanced visualization of microglia following immunostaining. The increase in OX-42-ir microglia may also be due in part to the reactive response of microglia to neuronal injury. Direct injury such as mechanical damage to neurons has been shown to induce reactive microglial activation in animals (Raivich et al., 1999). Therefore, it is possible that in the neuron-glia cultures, microglia would respond to the MnCl2-induced neuronal damage by upregulation of surface markers and increase in abundance. The inability of either MnCl2 or LPS to stimulate the proliferation of isolated microglia remains to be fully understood. Interestingly, Kloss and associates tested a panel of soluble factors including various cytokines for their ability to stimulate the proliferation of microglia grown on astroglia monolayers and found that only macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-3 were mitogenic to microglia and most other cytokines suppressed microglial proliferation (Kloss et al., 1997). While LPS-stimulated microglia were known to produce IL-3, astroglia seemed to be the predominant source of GM-CSF following LPS stimulation (Ganter et al., 1992; Lee et al., 1994).

Activated microglia and astroglia exert their deleterious effect on neurons through the production and release of various pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic cytokines and free radicals (Liu, 2006). In this study, no significant release of cytokines TNFα and IL-1β was detected in cultures treated with 10–300 μM MnCl2, the range of MnCl2 concentrations that exhibited glial activation-promoted DA neurodegeneration (Figs. 5A & 5B). This finding is consistent with findings reported by others. For example, in the mouse N9 microglial cells, no release of TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6 was detected in cells treated for up to 48 hours with concentrations of MnCl2 lower than 500 μM (Filipov et al., 2005). In rat primary mixed cultures that contained approximately 15% microglia, MnCl2 (24 hour treatment) again failed to induce TNFα production (Chen et al., 2006). Compared to the poor response in TNFα and IL-1β production, significant accumulation of nitrite was detected in the neuron-glia cultures following treatment with MnCl2 (Fig. 5C). As early as 24 hours following treatment with 10–300 μM MnCl2, an upward trend in NO production was detectable and 3 days later, significant nitrite accumulation was observed in cultures treated with ≥ 100 μM MnCl2. Astroglia may be a more prominent contributor than microglia to the MnCl2-stimulated nitrite production. No statistically significant elevations in the accumulation of nitrite were detected in primary rat microglia treated for up to 72 hours with up to 300 μM MnCl2 (Fig. 6C, this study) or the mouse N9 microglial cells treated for up to 48 hours with up to 500 μM MnCl2 (Chang and Liu, 1999; Filipov et al., 2005). On the other hand, increase in iNOS message and/or protein was observed in N9 or the mouse BV2 microglial cells treated for 6–18 hours with 500 μM or possibly as low as 100–250 μM MnCl2 (Bae et al., 2006; Filipov et al., 2005). It might be possible that the limited sensitivity (~0.5 μM) of the Griess reagent-based nitrite assay employed in some of those studies and the potential interference by culture media have prevented the detection of more subtle increases in NO released from MnCl2-activated microglia that are involvled in the facilitation of DA neurotoxicity (Green et al., 1982). In contrast, significant upregulation of iNOS gene and production of NO were detected in primary mouse astroglia (96% pure) treated for 8 hours with 10 μM MnCl2 and C6 glioma cells treated for 24 hours with 100 μM MnCl2 (Barhoumi et al., 2004; Moreno et al., 2008). While the MnCl2-induced glial iNOS induction and NO production clearly contributes to the glia-enhancement of DA neurotoxicity as demonstrated by the protective effect of NOS inhibitor L-NAME in this study (Fig. 7), the precise roles of microglia and astroglia and the detailed mechanisms of action warrant further investigation.

Of the various proinflammatory and neurotoxic factors produced by activated glia, ROS may be particularly deleterious to DA neurons because of their known vulnerability to oxidative damage (Greenamyre et al., 1999; Jenner and Olanow, 1998). ROS appears to be among the earliest neurotoxic factors produced by manganese-activated glia. In this study, significant ROS production was detected as early as 12 hours following MnCl2 treatment (Fig. 5D). Compared to astroglia, microglia were the predominant source of ROS generation (Babior, 2004; Liu et al., 2003). In both the microglia-enriched and mixed glia cultures that contained at least 15% microglia, robust ROS production was detected following treatment with 10 μM MnCl2 (Fig. 5D, this study). In comparison, astroglia appeared to be less responsive to the MnCl2-stimulated ROS production (Barhoumi et al., 2004; Liao et al., 2007). Furthermore, microglia were far more efficient than astroglia in releasing hydrogen peroxide following MnCl2 treatment (Zhang et al., 2007). Hydrogen peroxide may interact, through the Fenton reaction, with iron that is particularly enriched in the nigra to form the highly damaging hydroxyl radical (Gerlach et al., 2003). Superoxide anion, on the other hand, can react with NO to form the highly reactive perxynitrite free radical (Beckman and Crow, 1993). Therefore, ROS produced by activated microglia and to a lesser extent astroglia may work together with RNS produced from astroglia as well as microglia to facilitate the MnCl2-induced degeneration of DA neurons in the cultures. Hence, neutralization of the reactivity of ROS and inhibition of the biosynthesis of RNS protected DA neurons against MnCl2-induced damage (Fig. 7). The contribution of ROS and RNS from microglia and astroglia do not exclude the involvement of additional microglial and astroglial factors yet to be identified as well as that of the direct toxic effect inflicted by MnCl2, especially at the higher end of the concentration spectrum. This might help explain the slightly, yet statistically insignificant higher degree of protection afforded by GSH and NAC compared to that by SOD/catalase because GSH and NAC that can easily enter both glia and neurons to neutralize the reactivity of free radicals in affording neuroprotection.

It is worth noting that the concentration dependence of MnCl2 for activating microglia in the microglia-enriched cultures was not identical to that for causing DA neurodegeneration in the neuron-glia cultures. For example, while 10 μM MnCl2 caused a robust generation of ROS (Fig. 6B, this study) and H2O2 release in the microglia-enriched cultures (Zhang et al., 2007), the same concentration of MnCl2 produced a significant reduction in TH-ir neurite and DA uptake capacity (Fig. 2) but not degeneration of TH-ir neuronal cell bodies in the neuron-glia cultures (Fig. 1B). Several factors might have contributed to the differential concentration dependence for MnCl2 between microglia and neuron-glia cultures. First, microglia typically represent ~10% of the total number of cells in the mesencephalic neuron-glia cultures (Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2000). Third, although the precise kinetics of uptake and storage of MnCl2 for microglia, astroglia and various types of neurons remain to be fully understood, astroglia are known to be highly efficient in uptaking and accumulating divalent manganese(Aschner et al., 1992; Aschner et al., 1999). Therefore, in the mixed neuron-glia cultures, astroglia and definitely various neurons as well would reduce the availability of MnCl2 to microglia that co-inhabit the same mixed cultures. Such a “diversion” of MnCl2 would be very minimal in the microglia-enriched cultures (>98% pure) and nonexistent in the microglial cell line cultures. Second, perhaps more important, the reactivity of microglia at least in cultures are known to be markedly subdued by the presence of neurons potentially through cell-cell contact mediated by adhesion molecules or soluble factors such as certain neurotransmitters (Carnevale et al., 2007; Chang et al., 2000). For example, the concentration of LPS (10 ng/ml) required to induce a maximal release of TNFα from microglia in the rat neuron-glia cultures was approximately one order of magnitude higher than that (1 ng/ml) in the rat microglia-enriched cultures whereas 10 ng/ml LPS was clearly more effective than 1 ng/ml LPS in causing DA neurodegeneration in the neuron-glia cultures (Chang et al., 2001; Gao et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2001). In this study, 10 ng/ml LPS was more effective than 1 ng/ml in inducing the increase in the number of OX-42-ir microglia in the neuron-glia cultures (Figs. 4B & 4C, this study). However, 10 ng/ml LPS was not more effective than 1 ng/ml in inducing NO release and ROS production in microglia cultures (Figs. 6B & 6C). Therefore, neuronal suppression of microglial reactivity would have greatly dampened the response of microglia to MnCl2-stimulated surface receptor expression, production of ROS and release of H2O2. The combination of the aforementioned factors might most probably have collectively helped shift the concentration dependence curve for MnCl2-induced microglial activation between “pure” microglia cultures and mixed neuron-glia cultures.

Studies of postmortem brains of humans, non-human primates and rodents have indicated that manganese-induced neuronal damages are more prominent in the globus pallidus and less severe in caudate, putamen (striatum) and other structures of the basal ganglia (Aschner et al., 2007; Perl and Olanow, 2007). Alterations in striatal DA neurochemistry including decreased DA transporter function and/or striatal DA levels have been reported whereas the integrity of the DA neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta, however, is thought to be spared in the manganese-induced Parkinsonism (Aschner et al., 2007; Perl and Olanow, 2007). In PD, degeneration of the striatal DA-releasing fibers and the DA neuronal cell bodies in the substantia nigra pars compacta is one of the major pathological hallmarks. Clinical symptoms of manganese-induced Parkinsonism and classic PD are somewhat overlapping in posture instability, slowed movement and rigidity. However, manganese-induced Parkinsonism seems to differ from classic PD in the presentation of a kinetic tremor, a more symmetric presentation of clinical symptoms, and a limited response to levo-DOPA treatment (Cersosimo and Koller, 2006; Pal et al., 1999). In the current in vitro study, DA neurons (TH-ir) in the neuron-glia cultures prepared from the mesencephalic tissues, perhaps due to their innate vulnerability to damage by free radicals, were more susceptible than neurons in general (Neu-N-ir or MAP-2-ir) to the MnCl2-induced damage. Several points need to be considered in extrapolating these findings to gain further insights into the manganese neurotoxicity in humans and the potential relevance to the pathogenesis of PD. First, divalent manganese is perhaps one of the several potentially neurotoxic forms of manganese. A number of studies that compared the potency of divalent and trivalent manganese indicated that trivalent manganese was more potent than divalent manganese in inducing free radical generation in brain mitochondrial preparations and neuronal cells but were differentially effective in damaging PC12 cells and causing neurochemical changes in animals (Ali et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2001; Reaney et al., 2006; Reaney and Smith, 2005). A recent study reported that mice that were inhalationally exposed for 5 months to a mixture of divalent and trivalent manganese developed movement abnormalities and loss of nigral DA neurons (Ordonez-Librado et al., 2008). Secondly, manganese in tissues can undergo biotransformation and can exist as bi-, tri- and tetravalent manganese with the divalent state being the predominant form (Aschner et al., 2005). Therefore, the exact contribution of various forms of manganese to neurodegeneration may require further investigation. Thirdly, elevated environmental exposure to manganese may be one of the risk factors to the development of PD (Calne and Langston, 1983; Hatcher et al., 2008). In this context, manganese may work with other toxicants and/or intrinsic factors to induce a cooperative, progressive and preferential DA neurotoxicity.

In summary, results from this study suggest that activation of microglia and the generation of free radicals facilitate the dopaminergic neurotoxicity of manganese. These findings shed new light on the understanding of manganese neurotoxicity. Furthermore, these findings may have particular relevance to the role of chronic overexposure to environmentally relevant levels of manganese in the pathogenesis of PD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (ES013265) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali SF, Duhart HM, Newport GD, Lipe GW, Slikker W. Manganese-induced reactive oxygen species: Comparison between Mn+2 and Mn+3. Neurodegeneration. 1995;4:329–334. doi: 10.1016/1055-8330(95)90023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F. The role of microglia and astrocytes in CNS immune surveillance and immunopathology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;468:123–133. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4685-6_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Erikson KM, Dorman DC. Manganese Dosimetry: Species Differences and Implications for Neurotoxicity. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2005;35:1 – 32. doi: 10.1080/10408440590905920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Gannon M, Kimelberg HK. Manganese uptake and efflux in cultured rat astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1992;58:730–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Guilarte TsR, Schneider JS, Zheng W. Manganese: Recent advances in understanding its transport and neurotoxicity. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;221:131–147. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschner M, Vrana KE, Zheng W. Manganese uptake and distribution in the central nervous system (CNS) Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babior BM. NADPH oxidase. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae JH, Jang BC, Suh SI, Ha E, Baik HH, Kim SS, Lee MY, Shin DH. Manganese induces inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression via activation of both MAP kinase and PI3K/Akt pathways in BV2 microglial cells. Neurosci Lett. 2006;398:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhoumi R, Faske J, Liu X, Tjalkens RB. Manganese potentiates lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of NOS2 in C6 glioma cells through mitochondrial-dependent activation of nuclear factor kappaB. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;122:167–179. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Crow JP. Pathological implications of nitric oxide, superoxide and peroxynitrite formation. Biochem Soc Trans. 1993;21:330–334. doi: 10.1042/bst0210330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Besinger A, Herms JW, Kretzschmar HA. Microglial expression of the prion protein. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1425–1429. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC. Mechanisms of inflammatory neurodegeneration: iNOS and NADPH oxidase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1119–1121. doi: 10.1042/BST0351119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calne DB, Langston JW. Aetiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1983;2:1457–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90802-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale D, De Simone R, Minghetti L. Microglia-neuron interaction in inflammatory and degenerative diseases: role of cholinergic and noradrenergic systems. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6:388–397. doi: 10.2174/187152707783399193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cersosimo MG, Koller WC. The diagnosis of manganese-induced parkinsonism. NeuroToxicology. 2006;27:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JY, Liu LZ. Manganese potentiates nitric oxide production by microglia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;68:22–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RC, Chen W, Hudson P, Wilson B, Han DS, Hong JS. Neurons reduce glial responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and prevent injury of microglial cells from over-activation by LPS. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1042–1049. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang RC, Hudson P, Wilson B, Liu B, Abel H, Hemperly J, Hong JS. Immune modulatory effects of neural cell adhesion molecules on lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production by cultured glia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;81:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Ou YC, Lin SY, Liao SL, Chen SY, Chen JH. Manganese modulates pro-inflammatory gene expression in activated glia. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Tsao GC, Zhao Q, Zheng W. Differential Cytotoxicity of Mn(II) and Mn(III): Special Reference to Mitochondrial [Fe-S] Containing Enzymes. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2001;175:160–168. doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson ED, Rosa FG, Edwards-Prasad J, Weiland DA, Witta SE, Freed CR, Prasad KN. Improvement of neurological deficits in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats after transplantation with allogeneic simian virus 40 large tumor antigen gene-induced immortalized dopamine cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1265–1270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta G, Zhang P, Liu B. The lipopolysaccharide Parkinson’s disease animal model: mechanistic studies and drug discovery. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:453–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00616.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson KM, Aschner M. Manganese neurotoxicity and glutamate-GABA interaction. Neurochem Int. 2003;43:475–480. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipov NM, Seegal RF, Lawrence DA. Manganese potentiates in vitro production of proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide by microglia through a nuclear factor kappa B-dependent mechanism. Toxicol Sci. 2005;84:139–148. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein MM, Jerrett M. A study of the relationships between Parkinson’s disease and markers of traffic-derived and environmental manganese air pollution in two Canadian cities. Environ Res. 2007;104:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganter S, Northoff H, Mannel D, Gebicke-Harter PJ. Growth control of cultured microglia. J Neurosci Res. 1992;33:218–230. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Hong JS, Zhang W, Liu B. Distinct role for microglia in rotenone-induced degeneration of dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:782–790. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00782.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Hong JS, Zhang W, Liu B. Synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity of the pesticide rotenone and inflammogen lipopolysaccharide: relevance to the etiology of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1228–1236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01228.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Jiang J, Wilson B, Zhang W, Hong JS, Liu B. Microglial activation-mediated delayed and progressive degeneration of rat nigral dopaminergic neurons: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2002;81:1285–1297. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach M, Double KL, Ben-Shachar D, Zecca L, Youdim MB, Riederer P. Neuromelanin and its interaction with iron as a potential risk factor for dopaminergic neurodegeneration underlying Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox Res. 2003;5:35–44. doi: 10.1007/BF03033371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Kortsha GX, Brown GG, Richardson RJ. Occupational exposures to metals as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1997;48:650–658. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Kortsha GX, Brown GG, Richardson RJ. Occupational exposure to manganese, copper, lead, iron, mercury and zinc and the risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N]nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem. 1982;126:131–138. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(82)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenamyre JT, MacKenzie G, Peng TI, Stephans SE. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem Soc Symp. 1999;66:85–97. doi: 10.1042/bss0660085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher JM, Pennell KD, Miller GW. Parkinson’s disease and pesticides: a toxicological perspective. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazell AS. Astrocytes and manganese neurotoxicity. Neurochem Int. 2002;41:271–277. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P, Olanow CW. Understanding cell death in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:S72–84. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WG, Mohney RP, Wilson B, Jeohn GH, Liu B, Hong JS. Regional difference in susceptibility to lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity in the rat brain: role of microglia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6309–6316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06309.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa M, Anantharam V, Yang Y, Hirata Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Activation of protein kinase C[delta] by proteolytic cleavage contributes to manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic cells: protective role of Bcl-2. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2005;69:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloss CU, Kreutzberg GW, Raivich G. Proliferation of ramified microglia on an astrocyte monolayer: characterization of stimulatory and inhibitory cytokines. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:312–318. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchoumycandane C, Anantharam V, Kitazawa M, Yang Y, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Protein kinase Cdelta is a key downstream mediator of manganese-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neuronal cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:46–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39:151–170. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Liu W, Brosnan CF, Dickson DW. GM-CSF promotes proliferation of human fetal and adult microglia in primary cultures. Glia. 1994;12:309–318. doi: 10.1002/glia.440120407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SL, Ou YC, Chen SY, Chiang AN, Chen CJ. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 expression by manganese in cultured astrocytes. Neurochemistry International. 2007;50:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. Modulation of microglial pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic activity for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Aaps J. 2006;8:E606–621. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Du L, Hong JS. Naloxone protects rat dopaminergic neurons against inflammatory damage through inhibition of microglia activation and superoxide generation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:607–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Du L, Kong LY, Hudson PM, Wilson BC, Chang RC, Abel HH, Hong JS. Reduction by naloxone of lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity in mouse cortical neuron-glia co-cultures. Neuroscience. 2000;97:749–756. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Gao HM, Hong JS. Parkinson’s disease and exposure to infectious agents and pesticides and the occurrence of brain injuries: role of neuroinflammation. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1065–1073. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Gao HM, Wang JY, Jeohn GH, Cooper CL, Hong JS. Role of nitric oxide in inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;962:318–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Hong JS. Role of microglia in inflammation-mediated neurodegenerative diseases: mechanisms and strategies for therapeutic intervention. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Wang K, Gao HM, Mandavilli B, Wang JY, Hong JS. Molecular consequences of activated microglia in the brain: overactivation induces apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2001;77:182–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H, Fang X, Floyd KM, Polcz JE, Zhang P, Liu B. Induction of microglial reactive oxygen species production by the organochlorinated pesticide dieldrin. Brain Research. 2007;1186:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Glial reactions in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:474–483. doi: 10.1002/mds.21751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JA, Sullivan KA, Carbone DL, Hanneman WH, Tjalkens RB. Manganese potentiates nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent expression of nitric oxide synthase 2 in astrocytes by activating soluble guanylate cyclase and extracellular responsive kinase signaling pathways. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2028–2038. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez-Librado JL, Gutierrez-Valdez AL, Colin-Barenque L, Anaya-Martinez V, Diaz-Bech P, Avila-Costa MR. Inhalation of divalent and trivalent manganese mixture induces a Parkinson’s disease model: immunocytochemical and behavioral evidences. Neuroscience. 2008;155:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal PK, Samii A, Calne DB. Manganese neurotoxicity: a review of clinical features, imaging and pathology. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl DP, Olanow CW. The neuropathology of manganese-induced Parkinsonism. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:675–682. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31812503cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przedborski S. Neuroinflammation and Parkinson’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2007;83:535–551. doi: 10.1016/S0072-9752(07)83026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racette BA, McGee-Minnich L, Moerlein SM, Mink JW, Videen TO, Perlmutter JS. Welding-related parkinsonism: clinical features, treatment, and pathophysiology. Neurology. 2001;56:8–13. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racette BA, Tabbal SD, Jennings D, Good L, Perlmutter JS, Evanoff B. Prevalence of parkinsonism and relationship to exposure in a large sample of Alabama welders. Neurology. 2005;64:230–235. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149511.19487.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raivich G, Bohatschek M, Kloss CU, Werner A, Jones LL, Kreutzberg GW. Neuroglial activation repertoire in the injured brain: graded response, molecular mechanisms and cues to physiological function. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;30:77–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaney SH, Bench G, Smith DR. Brain accumulation and toxicity of Mn(II) and Mn(III) exposures. Toxicol Sci. 2006;93:114–124. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reaney SH, Smith DR. Manganese oxidation state mediates toxicity in PC12 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;205:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer TB, Betarbet R, Kim JH, Greenamyre JT. Selective microglial activation in the rat rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2003;341:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spranger M, Schwab S, Desiderato S, Bonmann E, Krieger D, Fandrey J. Manganese augments nitric oxide synthesis in murine astrocytes: a new pathogenetic mechanism in manganism? Exp Neurol. 1998;149:277–283. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EK, Tan C, Fook-Chong SM, Lum SY, Chai A, Chung H, Shen H, Zhao Y, Teoh ML, Yih Y, Pavanni R, Chandran VR, Wong MC. Dose-dependent protective effect of coffee, tea, and smoking in Parkinson’s disease: a study in ethnic Chinese. J Neurol Sci. 2003;216:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Hatter A, Liu B. Manganese chloride stimulates rat microglia to release hydrogen peroxide. Toxicology Letters. 2007;173:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]