Abstract

Mutations in the gene encoding adenosine deaminase (ADA), a purine salvage enzyme, lead to immunodeficiency in humans. Although ADA deficiency has been analyzed in cell culture and murine models, information is lacking concerning its impact on the development of human thymocytes. We have used chimeric human/mouse fetal thymic organ culture (hu/moFTOC) to study ADA-deficient human thymocyte development in an “in vivo-like” environment where toxic metabolites accumulate in situ. Inhibition of ADA during human thymocyte development resulted in a severe reduction in cellular expansion as well as impaired differentiation, largely affecting mature thymocyte populations. Thymocyte differentiation was not blocked at a discrete stage; rather, the paucity of mature thymocytes was due to the induction of apoptosis as evidenced by activation of caspases and was accompanied by the accumulation of intracellular deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP). Inhibition of adenosine kinase and deoxycytidine kinase prevented the accumulation of dATP and restored thymocyte differentiation and proliferation. Our work reveals that multiple deoxynucleoside kinases are involved in the phosphorylation of deoxyadenosine when ADA is absent, and suggests an alternate therapeutic strategy for treatment of ADA-deficient patients.

Keywords: human, immunodeficiency diseases, apoptosis, thymus

Introduction

Mutations in the gene encoding adenosine deaminase (ADA), a purine metabolic enzyme that catalyzes the deamination of both adenosine and deoxyadenosine (dAdo), cause severe combined immunodeficiency in humans (1). ADA-deficient humans have a pronounced deficiency of T cells with variable numbers of B and NK cells, and die early in life of infections unless treated with enzyme replacement therapy, bone marrow transplantation, or gene therapy (reviewed in 2,3). The paucity of lymphoid cells in thymuses from ADA-deficient infants suggests a profound defect in thymocyte development (4). With the demonstration of elevated dATP in the red blood cells of ADA-deficient patients (5,6), the ADA substrate deoxyadenosine (dAdo) became the prime candidate for causing lymphoid toxicity. However, little is known about the specific stage or stages of lymphocyte development that might be sensitive to a lack of ADA or of specific mechanism(s) responsible for the lack of thymocyte differentiation and/or proliferation in ADA-deficiency because of the difficulty in obtaining thymus samples from these rare patients and the lack of convenient culture systems for studying human thymocyte development.

The successive stages of human thymocyte maturation can be categorized as double negative (DN), double positive (DP) or single positive (SP) according to the presence or absence of the CD4 and CD8 coreceptors. Immature human DN thymocytes are classified based on expression of CD34, CD38 and CD1a (reviewed in 7). The transition from the DN to DP stage occurs via a CD4 immature single positive (CD4 ISP) stage (8), accompanied by TCR gene rearrangements and the first developmental checkpoint, β-selection. β-selection involves the pairing of the TCRβ protein with the pre-Tα protein to produce a membrane-localized pre-TCR that signals survival, expansion, and allelic exclusion. β-selection occurs over a range of phenotypic stages from CD34+CD1a+ cells to DP cells (9,10). Successful β-selection leads to the expression of the αβTCR, followed by positive and negative selection, and development into mature CD4 and CD8 SP T cells (7,11). Thymuses from ADA-deficient patients have not been analyzed for their proportions of these normal human thymocyte subsets, nor has human thymocyte development been studied in vitro under ADA-deficient conditions.

Mouse models for ADA deficiency have, however, yielded important clues to the pathogenesis of the immunodeficiency. In an in vitro model for murine thymocyte development, fetal thymic organ culture (FTOC) (12-14), inhibition of ADA led to a marked reduction in lymphocyte development secondary to the accumulation of intracellular dATP and mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Few thymocytes survived past the point of β-selection, most likely because the majority of thymocytes fail to pass this developmental checkpoint and die by apoptosis providing a source of ADA substrates. Thymocyte differentiation and proliferation could be rescued by the adenosine kinase (AK) inhibitor, 5′-amino-5′-deoxyadenosine (5′A5′dAdo) (15), since the main route of dAdo phosphorylation in murine cells is via AK (16,17).

It is well known that the pathway of dAdo phosphorylation in human thymocytes differs from that in the mouse (17,18), making it essential that models of human thymocyte development be utilized to understand the pathogenesis of ADA deficiency. Despite many early studies, there is still contention regarding which deoxynucleoside kinase is primarily responsible for dAdo phosphorylation in human thymocytes. Deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) is usually thought to be the major cytoplasmic enzyme responsible for phosphorylation of deoxycytidine, deoxyguanosine, and deoxyadenosine (19). Human adenosine kinase (AK) primarily utilizes Ado as a substrate, but can also phosphorylate dAdo when it is present in high enough concentration (20,21). Differential roles for these enzymes depend upon experimental context. In cell extracts, dCK was the primary dAdo phosphorylating enzyme (22), while in intact human T and B lymphoblastoid cells, AK activity was more important (21,23). The relative roles of each of these nucleoside kinases in human ADA-deficient thymocyte development have yet to be investigated.

Here we report the use of human/mouse chimeric fetal thymic organ culture (hu/moFTOC) to study the consequences of ADA deficiency upon human thymocyte development. In this model system, human CD34+ thymic precursor cells reconstitute murine thymocyte-depleted fetal thymic lobes and develop normally through positive selection (24,25). We show that cell expansion and differentiation are severely impaired when ADA is inhibited. We also demonstrate the importance of both dCK and AK in the accumulation of dATP and induction of apoptosis in developing thymocytes, evidenced by the normalization of dATP levels and rescue of ADA-deficient thymocyte development in the presence of multiple deoxynucleoside kinase inhibitors. Our studies lend further support to the idea that dATP accumulation is the primary cause of toxicity to developing human thymocytes under conditions of ADA deficiency, and underscore differences between murine and human development. Our findings also suggest that treatment of ADA-deficient patients with a combination of nucleoside kinase inhibitors may be an alternative therapeutic strategy to prevent metabolic toxicity to developing thymocytes.

Materials and Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, Maine) were bred in our animal facility under specific pathogen-free conditions and in compliance with the OMRF Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee specifications.

Drugs and reagents

The specific ADA inhibitor, 2′-deoxycoformycin (dCF) (26) was obtained from SuperGen (Dublin, CA). 5′A5′dAdo, dAdo, dCyd and all other chemical reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Antibodies, thymocyte cell preparation and immunofluorescent staining

Antibodies used were: FITC anti-CD1a, APC anti-CD34, PE anti-γδTCR, FITC anti-CD8, and PE anti-αβTCR (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); PE and PE-Texas Red anti-CD8α, PE-Cy5, PE-Cy5.5 and APC anti-CD4, PE anti-CD34, FITC and PE anti-αβTCR, FITC and APC anti-CD3, FITC anti-γδTCR, and PE anti-Bcl-2 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); PE anti-CD8β (Serotec, Raleigh, NC); and PE anti-TCRCβ (Ancell, Bayport, MN). Matched isotype control antibodies were purchased from all the above sources.

Human neonatal thymus was obtained from children (ages 1 d - 4 yrs) undergoing cardiac surgery at Children’s Hospital in Oklahoma City, OK under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. Thymocyte cell suspensions were made by forcing the thymic tissue pieces through a nylon filter. Human CD34+ thymocytes were enriched with anti-CD34 magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech; Lake Success, NY), and sorted if needed to obtain ≥ 95% purity for use in hu/moFTOC. Staining for intracellular TCRβ (TCRβic) expression was performed by fixing cells with 1% formaldehyde and permeabilizing with 0.5% saponin (10). Data were collected using an LSR II or FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA). FITC Annexin-V (Caltag), was used following the manufacturer’s instructions after surface staining with anti-CD4 and -CD8 antibodies. Propidium iodide staining for cell cycle assessment was performed as described (10) and analyzed using the Dean-Jett-Fox cell cycle analysis algorithm in FlowJo analysis software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Chimeric human/mouse fetal thymic organ culture

Hu/moFTOCs were performed as previously described (27). Briefly, fetal thymic lobes from timed pregnant C57BL/6 mice at d15 of gestation (plug day = d0) were placed in FTOC for 4-6 days with 1.35 mM 2′-deoxyguanosine to deplete endogenous murine thymocytes. The lobes were then washed in complete medium to remove deoxyguanosine and placed in Terasaki wells with 25 μl of Yssel’s medium (28) supplemented with 5% FCS/2% human serum (Yssel’s complete medium) containing 1-2×104 human thymocyte precursors. After 2 days of hanging drop culture, the lobes were transferred to a standard FTOC format in Yssel’s complete medium, and cultured ± 5 μM dCF. 5′A5′dAdo was used at 5 μM, and dCyd was used at 50 μM with culture medium replenished daily. Cultures were incubated for 1-3 wk, then harvested by forcing the thymic lobes through a 70 μM nylon mesh. Thymocytes were counted in trypan blue to assess viability, stained with antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry or processed for dATP analysis. Suspension cultures for dATP accumulation were performed in Yssel’s complete medium with 5 μM dCF and the indicated concentration of dAdo. Cultures were incubated 20 h at 37°C, then cells were counted and processed for dATP analysis by HPLC.

TCR gene rearrangement analysis

Thymocyte genomic DNA from either control or dCF-treated hu/moFTOCs was prepared using the Puregene Kit (Gentra Systems; Minneapolis, MN). TCR gene nomenclature is that of the IMGT (International ImMunoGeneTics database; http://imgt.cines.fr). Vβ20.1 rearrangements to either Jβ1.1-1.6 or Jβ2.1-2.3 were amplified from 200 ng of genomic DNA using JumpStart Taq DNA Polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich) (10). A portion of the RAG2 gene was amplified to normalize for input DNA in the PCR reactions. Primers used were: RAG2-Forward: 5′-TGTGAATTGCACAGTCTTGCCAGG; RAG2-Reverse: 5′-GGGTTTGTTGAGCTCAGTTGAATAG; Jβ20.1-Forward: 5′-GATCGAGTGCCGTTCCCTGGACTT; Jβ1.6-Reverse: 5′-ACCCTGACCTCCGTTCTTACACTC; Jβ2.3-Reverse: 5′-GGTGCCTGGGCCAAAATACTGCGTA.

HPLC Analysis of dATP from thymocytes and S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase activity assays

Single cell suspensions were prepared at 4°C from 30-60 lobes of hu/moFTOC treated with dCF ± deoxynucleoside kinase inhibitors for 8-14 days. Aliquots were removed for cell counts and immunophenotyping; then the remainder of the cells immediately pelleted and resuspended in 0.5ml of ice-cold 60% MeOH. The cells were extracted at -80°C for ≥ 18 hr, then analyzed for dATP content by HPLC as previously described (29). For S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) hydrolase activity measurements, thymocytes were washed with cold PBS and resuspended in 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 plus protease inhibitors. Cell extracts were prepared by 3 rounds of freeze-thaw lysis, followed by clarification by centrifugation. SAH hydrolase enzyme activity was determined by measuring the formation of SAH from homocysteine and radiolabeled adenosine as described previously (29).

Results

Inhibition of human thymocyte development under ADA-deficient conditions in hu/moFTOC

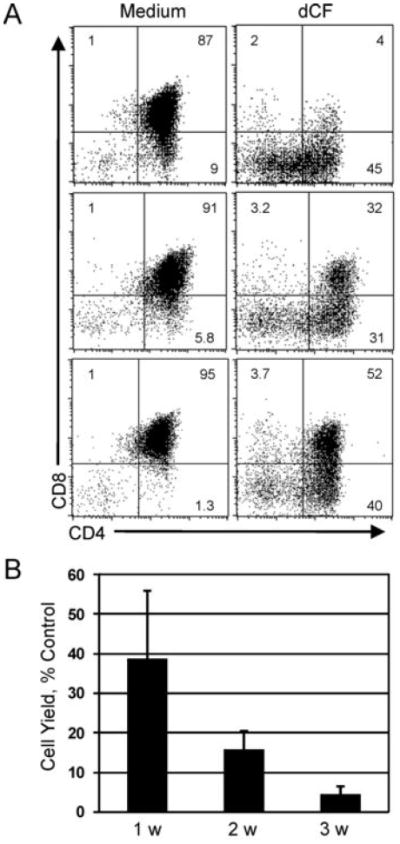

To assess the impact of ADA deficiency on developing human thymocytes, hu/moFTOCs were seeded with CD34+DN thymocytes and allowed to develop for various time periods up to 3 wk in the presence and absence of the specific, tight-binding ADA inhibitor, dCF. DP thymocyte development was efficient in control cultures (Figure 1A, Medium), but was dramatically impaired by the addition of dCF (Figure 1A, dCF). A broad range of developmental inhibition was observed (from <5% - >50% DP thymocytes) as illustrated by data from three independent experiments. The decreased percentage of DP thymocytes was always accompanied by increased percentages of CD4 ISP and DN thymocytes, indicating an inhibition of differentiation or a lack of survival and/or expansion of more mature thymocytes (or a combination of these). While cell yields progressively increased in control conditions, lack of ADA activity caused a cumulative decrease in cell yields, which were typically inhibited by ≥95% relative to controls at 3 wks (Figure 1B). It should be noted that while the percentages of DP thymocytes varied from culture to culture, the absolute numbers of DP thymocytes were consistently decreased by ≥ 90% in dCF-treated hu/moFTOCs. Similar results were obtained when starting the cultures with the earliest thymocyte progenitors, CD34+CD1a- cells, or with more mature populations such as CD4 ISPs or EDPs, though the kinetics of DP formation differed with the maturity of the starting population (data not shown). Similar results were also obtained when dCF was included in the hanging drop cultures.

Figure 1.

Human thymocyte yield and differentiation are severely impaired in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC. A. CD34+DN cells from human thymus were cultured in hu/moFTOC in Yssel’s complete medium ± 5 μM dCF for 3 wk, then harvested, stained with antibodies to CD4 and CD8. Three individual experiments are shown. B. Cell yield from dCF-treated cultures expressed as a percentage of control cultures harvested at wk 1, 2 and 3 of culture (mean ± SD, n ≥ 6). Live cells/lobe were determined by trypan blue staining and counting.

Later stages of thymocyte development are most severely impacted by ADA deficiency

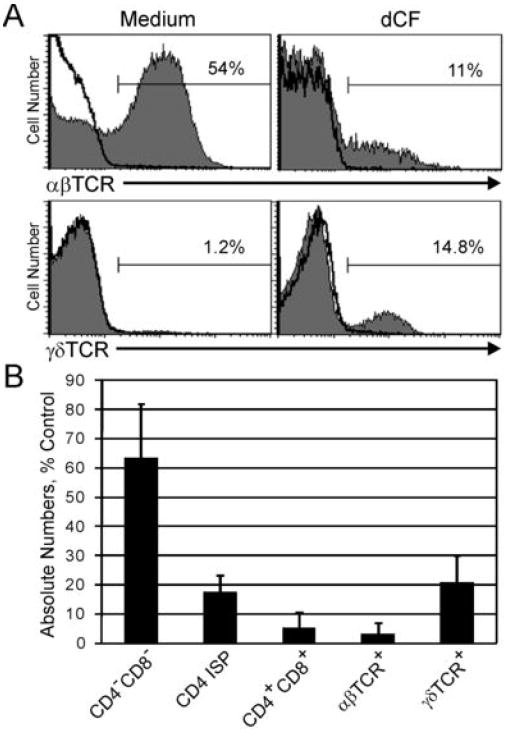

Percentages of αβ+ thymocytes were always severely reduced in ADA-inhibited cultures, while percentages of γδ+ thymocytes were increased after 3 wks culture (Figure 2A). An examination of the absolute numbers of thymocyte subpopulations revealed that both αβ+ and γδ+ thymocytes were decreased (Figure 2B). The increased percentages of γδ+ thymocytes likely reflects their development in an environment with very little overall cell expansion. Figure 2B also shows that the earliest stage of thymocyte development (DN) is least impacted by ADA deficiency.

Figure 2.

Mature thymocytes are most affected in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC. A. Cells from hu/moFTOC ± 5 μM dCF were harvested at 3 wk, stained with antibodies to αβTCR and γδTCR, and analyzed by flow cytometry (shaded histograms). Isotype control antibody staining is indicated by the black line histograms. B. Absolute numbers of human thymocyte subpopulations in dCF-treated hu/moFTOC at 3 wk expressed as a percentage of control cultures (mean ± SD, n ≥ 3).

Human thymocyte differentiation is not blocked at a discrete stage in the absence of ADA

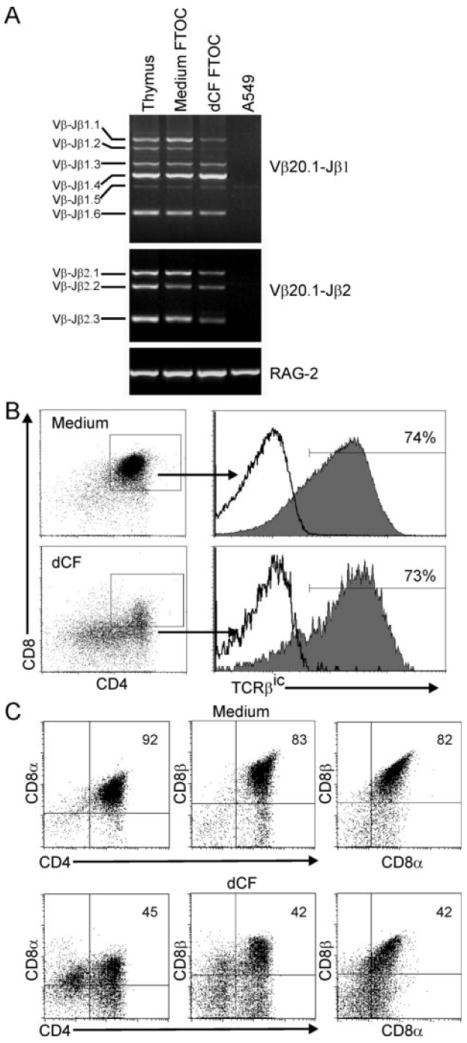

Because the yield of more mature populations of thymocytes was so severely compromised under ADA-deficient conditions, we investigated whether this might be the result of a block at a particular differentiation step. Key early steps in the differentiation of αβ lineage T cells involve the processes of TCRβ recombination and β-selection. We first examined whether TCRβ gene rearrangements might be inhibited in thymocytes developing in ADA-deficient conditions. Vβ20.1, known as Vβ2 in previous nomenclature, was chosen for this analysis because it is a commonly used Vβ gene segment in the human T cell repertoire (30). Figure 3A shows that complete V→DJ TCRβ gene rearrangements to both D-J gene clusters, as analyzed by PCR, were readily detectable in both control and dCF-treated hu/moFTOCs and were comparable in amounts to the rearrangements detected in total human thymocyte DNA. Therefore, the absence of ADA activity did not lead to an inability to rearrange TCRβ genes.

Figure 3.

Human thymocyte development in the absence of ADA is not blocked at a particular stage. A. Cells from hu/moFTOC ± 5 μM dCF were harvested at 3 wk and genomic DNA prepared. TCR gene rearrangements from human Vβ20.1 to either the Jβ1 or the Jβ2 region were analyzed by PCR and agarose gel electrophoresis. Genomic DNA from total human thymocytes (Thymus) or human fibroblast cells (A549) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. B and C. Cells from cultures were harvested as in A, stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8α, CD8β (C) and analyzed using flow cytometry. Following the surface stains, the cells were stained for TCRβic (B) as described in Materials and Methods. The dot plots shown are gated on all live cells, and the histograms for TCRβic expression are shown gated on the DP cells from each condition. Isotype control staining is indicated by the black line histograms.

Next, we assessed the expression of both intracellular TCRβ and CD8β in ADA-inhibited hu/moFTOC as a way to gauge the efficiency of the β-selection process and later differentiation events. Staining thymocytes for TCRβic expression is one way to evaluate whether an in frame TCRβ gene rearrangement has occurred. DP cells from control and dCF-treated cultures both showed similar high levels of TCRβic expression (Figure 3B), indicating that this requirement for β-selection was met in ADA-deficient cultures. Secondary to β-selection, early double positive (EDP) CD8α-expressing thymocytes up-regulate CD8β expression (31). To determine if this transition occurred normally in ADA-inhibited hu/moFTOC, DP cells were stained for the expression of cell surface CD8α and CD8β. Even though percentages of DP cells were greatly inhibited relative to controls, approximately the same percentages of cells that were CD4+CD8α+ were also CD8αβ+, indicating that development of EDP to true DP cells was not blocked in dCF-treated cultures (Figure 3C). These results demonstrate that the differentiation of cells in ADA-inhibited dCF was not blocked at a discrete stage of development, as assessed starting from the CD34+ thymocyte stage. Therefore, the selective loss of more mature thymocyte populations during ADA-inhibited development is likely due to increased cell death and/or lack of cell expansion.

ADA inhibition results in induction of apoptosis, inhibition of cellular proliferation and accumulation of intracellular dATP

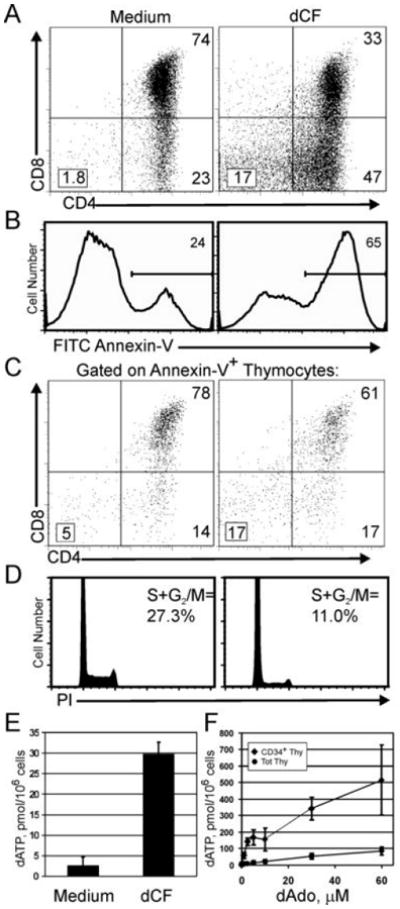

ADA-deficient patients have elevated levels of the ADA substrates dAdo and Ado in the plasma, and dATP in RBCs (32). dATP can induce mitochondrial cytochrome C release (33) and is a part of the apoptosome (34,35). Therefore, we examined the induction of apoptosis in thymocytes from ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC by Annexin-V staining. The CD4/CD8 phenotype at 11 days showed the typical reduction in DP percentages (Figure 4A), and Annexin-V staining showed that ADA-inhibited cultures had nearly 3 fold higher percentages of apoptotic cells compared to medium controls (Figure 4B). Caspase activation assessed with a fluorogenic caspase substrate which can bind to all activated caspases (FAM-VAD-fmk) showed 4-fold elevated percentages of activated caspases in ADA-inhibited cells (data not shown). In both dCF-treated and control cultures, DP cells were the primary population undergoing apoptosis (Figure 4C), although higher fractions of less mature cells (DNs and CD4 ISPs) were also seen in the dCF-treated cultures.

Figure 4.

Induction of apoptosis, inhibition of cell proliferation and accumulation of dATP in cells from ADA-inhibited hu/moFTOC. A-D: Hu/moFTOCs were incubated for 11 days ± 5 μM dCF; then cells were harvested and stained. One representative experiment out of 3 is shown. A. Surface staining with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 of total thymocytes. B. Annexin-V staining on total thymocytes from A. C.CD4/CD8 phenotype of Annexin-V+ cells in A. D. Cell cycle analysis of thymocytes from 11d culture stained with propidium iodide as described in Materials and Methods. E. Cells from 11d hu/moFTOCs were processed for dATP analysis as described in Materials and Methods. dATP is expressed in pmol/million cells (mean ± SD, n=4). F. Total and CD34+ thymocytes were incubated with 5 μM dCF ± dAdo for 20 h in suspension culture; then cells were harvested and analyzed for dATP as in E (mean ± SD, n=4).

Because cell yields were so dramatically inhibited in the absence of ADA activity, we next analyzed the proliferative capacity of the developing thymocytes. Propidium iodide staining at 11d of culture showed that nearly two thirds fewer cells were in cycle in dCF-treated cultures compared to medium controls (Figure 4D). Ki-67 staining supported this result, as fewer cells were in cycle in all phenotypic compartments in ADA-inhibited cultures (data not shown).

We next asked whether the induction of apoptosis in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC might be caused by the accumulation of dATP as was found in ADA-deficient murine FTOCs (12). HPLC analyses revealed that dATP accumulated to high levels (>15 fold over control) in 11 d cultures of ADA-inhibited hu/moFTOC (p = < 0.00001; Figure 4E). dATP could be detected as early as 8 d of culture, peaked at days 10-12, and declined thereafter to about 2-fold over control at 3 weeks of culture (data not shown).

Hu/moFTOCs were initiated with immature CD34+ DN thymocytes whose deoxynucleoside metabolism is known to change with differentiation (36). Because DN cells were least affected by ADA inhibition (Figure 2B), we compared the ability of these cells to accumulate dATP to that of total thymocytes (~80% DP cells). CD34+ thymocytes and total thymocytes were incubated in suspension cultures with dCF and varying concentrations of dAdo for 20 h, followed by harvest of the cells for dATP analysis. On average, CD34+ thymocytes accumulated ten times as much dATP/cell as total thymocytes, even at relatively low dAdo concentrations (<10 μM) (Figure 4F). Therefore, the relative survival advantage of immature thymocytes cannot be explained by an inability to accumulate dATP. In fact, these high levels of dATP did not induce any more caspase activation or apoptosis than was observed in cultures of total thymocytes at comparable concentrations of dAdo (data not shown).

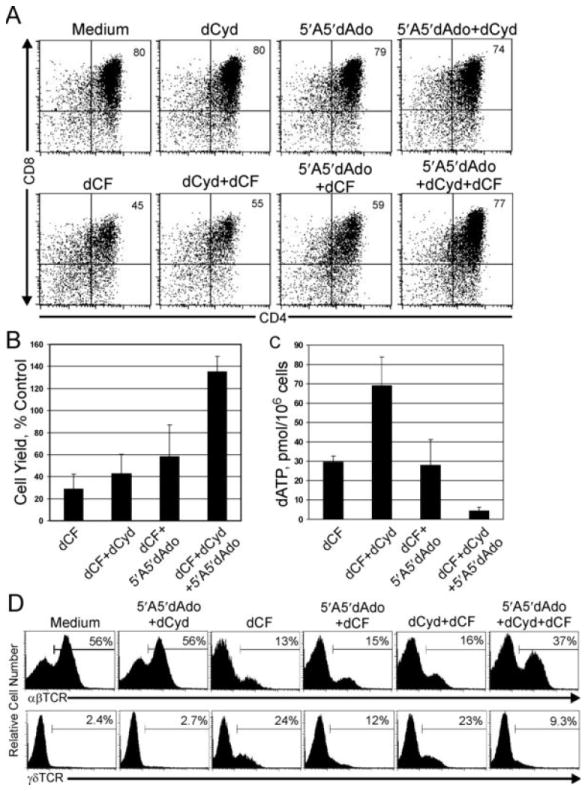

Rescue of human thymocyte development in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC by inhibition of deoxynucleoside kinases

The intracellular dATP in ADA-deficient thymocytes is derived from the ADA substrate dAdo by the action of cellular deoxynucleoside kinases. To attempt to prevent the accumulation of dATP and rescue thymocyte development in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC, we inhibited the activity of dCK and AK, either separately or in combination (Figure 5). AK activity can be efficiently inhibited by a structural analog of dAdo, 5′A5′dAdo which has nanomolar affinity for AK 15, while micromolar concentrations of dCyd competitively inhibit the phosphorylation of dAdo by dCK and promote feedback inhibition of dCK by the phosphorylated product, dCTP (37). We first assessed the impact on development at an early stage (10-12 d) when robust development and expansion of DP thymocytes occur in control cultures. The addition of the inhibitors alone, either singly or in combination, did not significantly perturb the expansion and development of thymocytes in hu/moFTOC (Figure 5A, and data not shown). The addition of either dCyd or 5′A5′dAdo to the dCF-treated cultures did not significantly restore the development of DP thymocytes (Figure 5A). Although the cell yields increase slightly with the addition of either dCyd or 5′A5′dAdo during dCF treatment (Figure 5B), these increases were not statistically significant. However, when both dCyd and 5′A5′dAdo were used, a complete rescue of DP thymocyte development and cell expansion was observed (Figure 5A, 5B). Cells from dCF-and dCF+5′A5′dAdo-treated cultures had similar amounts of accumulated dATP, at levels ~15 fold over control cultures (Figure 5C). Interestingly, cells from dCF+dCyd-treated cultures produced significantly higher levels of accumulated dATP, consistently ~2.5 fold higher than cells from cultures treated with dCF alone (p=0.003). However, there was no further decrease in cell yield (Figure 5B) or increase in apoptosis (data not shown). This is consistent with the dATP concentration having peaked over a “threshold” value needed to induce the effects observed with inhibition of ADA, above which there is little further effect. The use of both kinase inhibitors (dCyd+5′A5′dAdo) in dCF-treated cultures corrected both the phenotype and cell yields of the cultures, as well as normalized dATP levels to nearly those of the control.

Figure 5.

Rescue of ADA-deficient phenotype and dATP accumulation in hu/moFTOC by inhibition of deoxynucleoside kinases. A. Human CD34+ cells were cultured in hu/moFTOC in medium alone, 5 μM 5′A5′dAdo, 50 μM dCyd, or 50 μM dCyd + 5 μM 5′A5′dAdo ± 5 μM dCF for 10 d, then harvested, counted, and stained with antibodies to CD4 and CD8. B. Cell yield from experiments as in A, expressed as a percentage of each control condition (mean ± SD, n=4). C. Analysis of dATP accumulation for experiments as in A. dATP values are expressed as pmol/million cells (mean ± SD, n=4). D. Hu/moFTOCs incubated with the indicated combinations of 5 μM dCF, 5 μM 5′A5′dAdo and 50 μM dCyd were harvested after 3 wk, stained with antibodies to either αβTCR or γδTCR and analyzed by flow cytometry.

We next asked whether dCyd+5′A5′dAdo could also rescue longer (3 wk) ADA-inhibited cultures. Figure 5D shows an assessment of αβTCR and γδTCR thymocyte development by flow cytometry. Low percentages of αβ+ thymocytes and higher percentages of γδ+ thymocytes were observed in dCF-treated and dCF+dCyd-treated cultures, indicating little correction in long-term development. While there was no increase in the percentage of αβ+ thymocytes in dCF+5′A5′dAdo-treated cultures, the percentage of γδ+ thymocytes was reduced by ~50% relative to cultures treated with dCF alone. The addition of both kinase inhibitors to the dCF-treated cultures restored the development of TCR+ thymocytes to proportions similar to those in control cultures, indicating that inhibition of both deoxynucleoside kinases in long-term hu/moFTOCs could effectively restore the development of αβ and γδ thymocytes. Although the cell yields were not completely rescued (~40% of controls at 3 wks), the absolute numbers of both DP and αβ+ thymocytes showed substantial (50-fold) improvements. In summary, our data suggest that both dCK and AK play a role in the phosphorylation of the ADA substrate dAdo, leading to dATP accumulation in hu/moFTOC. Further, our data show that inhibition of both dCK and AK normalized dATP levels in hu/moFTOC and overcame the effect of ADA deficiency, allowing mature T cell development.

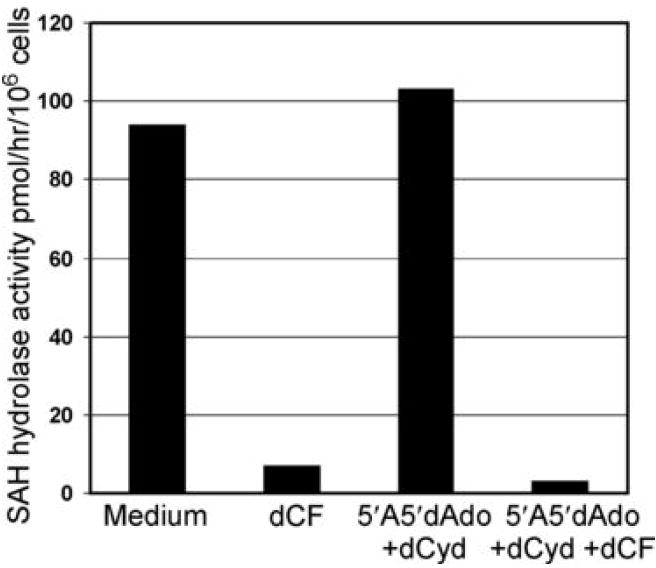

Rescue of ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC by deoxynucleoside kinase inhibition does not prevent inhibition of SAH hydrolase

SAH hydrolase is a high affinity adenosine binding protein which catalyzes the reversible reaction, Ado + L-homocysteine ⇔ SAH. In the absence of ADA, two factors contribute to dysregulation of SAH metabolism. First, the equilibrium constant of this reaction favors SAH formation, and increased Ado levels potentiate the accumulation of SAH, a product and potent inhibitor of numerous S-adenosyl methionine-dependent methyl transferase reactions. This inhibition of transmethylation reactions likely accounts for nucleotide-independent adenosine toxicity to lymphoblasts (38) and has been considered as a potential contributing mechanism to the immunodeficiency seen in ADA-deficient patients. Second, SAH hydrolase activity is inhibited by dAdo, in an active-site directed, “suicide-like” process (39). To assess the role of SAH hydrolase inhibition in the development of human thymocytes in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC, we measured SAH hydrolase activity in cells from ADA-inhibited and rescued cultures (Figure 6). SAH hydrolase activity was inhibited under ADA-deficient conditions as expected and remained inhibited in cultures that had been rescued with kinase inhibitors. It is therefore unlikely that inhibition of SAH hydrolase plays a significant role in the toxicity to developing thymocytes in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC.

Figure 6.

SAH hydrolase activity is inhibited in rescued ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC. SAH hydrolase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods in cell extracts of thymocytes harvested from hu/moFTOC cultured for 12 d. Results are expressed as pmol/hr/106 cells. The data shown are representative of two separate experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we provide the first description of the impact of ADA-deficiency upon human thymocyte development using an “in vivo-like” model for ADA deficiency, dCF-treated hu/moFTOC. Relatively little has been known about how human thymocytes develop in an ADA-deficient environment. Studies on patient RBCs or measurements of metabolites from patient fluids constituted the bulk of information known about purine metabolism in ADA-deficient patients. Hu/moFTOC appropriately recapitulates the metabolic and developmental environment of an ADA-deficient thymus, since toxic metabolites are generated in situ, rather than being provided exogenously, as in previous models (40). Here we show that ADA-inhibited human thymocyte development causes a cumulative loss of mature thymocytes, accompanied by induction of apoptosis, accumulation of intracellular dATP and inhibition of proliferation, but not a block in differentiation. Importantly, we show that normal thymocyte development, including the generation of TCR+ cells, is restored when the activities of AK and dCK are inhibited during culture.

The effects of ADA inhibition in hu/moFTOC were cumulative, with the loss of mature thymocytes more pronounced with longer cultures (Figures 1B, 2B and data not shown). Differentiation was not blocked at a discrete developmental stage, evidenced by detection of complete TCR rearrangements and expression of DP differentiation markers (TCRβic and CD8β; Figure 3). It is unknown whether the earliest multipotent thymic progenitors or stem cells are affected by ADA deficiency. Cultures initiated with pure sorted CD34+CD1a- thymocytes (the earliest thymocyte progenitors) readily generated CD4 ISPs in the presence of dCF and gave results that were indistinguishable from those initiated with CD34+ DN cells (primarily CD1a+, data not shown). Although these data do not address this issue directly, we think it is unlikely that stem cell differentiation is impaired by ADA deficiency since enzyme replacement therapy provides an effective treatment for ADA-deficient patients. It may be that reduced cell division (Fig. 4D) is the more significant factor in the lack of thymocyte development in ADA-deficient thymus. Histological studies of ADA-deficient thymic tissue from fetuses revealed a small thymic tissue rudiment devoid of lymphoid cells or normal thymic architecture (4). Lack of thymocyte expansion would lead to a thymus devoid of lymphocytes, without which a normal thymic architecture fails to develop.

Though the absolute numbers of DP thymocytes were always inhibited by >90% relative to controls, the proportions of DP thymocytes in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC varied from culture to culture (Figure 1A). While some of this is likely due to human sample heterogeneity, the majority could be explained by the non-synchronous occurrence of β-selection in human thymocyte development. Thymocytes that fail β-selection provide the first major source of ADA substrate to other thymocytes through degradation of apoptotic cell DNA. Cells that fail β-selection at an early stage (i.e. at the CD34+CD1a+ or CD4 ISP stage) generate substrate (dAdo) that can be taken up by adjacent cells and converted to dATP, inducing additional apoptosis before significant numbers of thymocytes reach the DP stage. Cultures where β-selection occurs earlier would yield low percentages of DP thymocytes (Figure 1A, top panel). However, thymocytes with a delayed β-selection process, occurring mainly in the DP stage, would not generate toxic levels of ADA substrates until many DP thymocytes had already been produced leading to higher percentages of surviving DP thymocytes (Figure 1A, bottom panel). Our studies of TCRβic expression in isolated ex vivo thymocytes suggest that the point of β-selection varies substantially from thymus to thymus (10) and provide an explanation for the variable proportions of surviving DP thymocytes in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC.

Cells from ADA-inhibited cultures had high levels of induced apoptosis accompanied by accumulation of intracellular dATP (Figure 4). A consistent finding was that immature thymocytes were relatively resistant to ADA inhibition (Figure 2B). Our initial hypothesis was that they had less ability to accumulate dATP. However, data in Figure 4F show that CD34+ thymocytes accumulate approximately 10-fold higher levels of dATP/cell than total thymocytes (which are about 80% DP thymocytes), likely a consequence of their relatively high deoxynucleoside kinase activities, coupled with low activity of enzymes (nucleotidases) that can carry out the reverse reaction (36,41). Furthermore, CD34+ thymocytes do not undergo dATP-induced apoptosis in suspension cultures to a greater degree than more mature cells (42), perhaps because their greater size decreases the actual intracellular concentration of dATP. On average, CD34+ thymocytes are 8.7 μm in diameter, while DP thymocytes are 6.0 μm (data not shown). However, the diameters of the nuclei of CD34+ and DP thymocytes are similar, so the cytoplasmic volume of CD34+ cells is actually more than three times that of DP thymocytes. It may also be that immature cells are inherently more resistant to apoptotic signals as suggested by the fact that immature T cell leukemias are very difficult to treat (43). We propose that as thymocytes mature, the marked decrease in cell size from the CD34+ to the DP stage increases the intracellular dATP concentration enough to induce cytochrome C release from mitochondria, triggering apoptosis in the vast majority of cells. This idea is consistent with the finding that dATP was greatly reduced in cells from 3 wk dCF-treated hu/moFTOC compared with earlier time points. We postulate that the only surviving cells in longer cultures were rare cells that failed to accumulate dATP or to undergo apoptosis as a part of normal development. In the rescued cultures (Figure 5), the elimination of both kinase activities lowered dATP enough to allow survival when the cells transitioned to the DP stage.

Our observation of hyper-elevated dATP in ADA-deficient hu/moFTOC treated with dCyd (Figure 5C) provides a plausible explanation for why dCyd therapy provided no clinical benefit in ADA-deficient patients (44). Treatment of ADA-inhibited thymocytes with dCyd in the presence of exogenous dAdo in suspension cultures prevented the accumulation of dATP (41,42), and was no doubt the rationale for the use of dCyd therapy in several ADA-deficient patients. However, our data suggest that AK also plays an important role in dAdo phosphorylation in our model. Therefore, analogous to the differences in enzymes that phosphorylate dAdo in cell extracts compared to intact cells, differences clearly exist in the phosphorylation of dAdo by thymocytes in suspension vs. in organ culture, a more “in vivo-like” environment. Because RBCs from ADA-deficient patients accumulate high levels of dATP even though erythrocytes have virtually no detectable dCK activity (2), there is in vivo precedence for the involvement of AK in the formation of dATP during ADA deficiency. The fact that AK is responsible for dATP accumulation in vivo leads us to hypothesize that the hyper-elevation in dATP in hu/moFTOC treated with dCF + dCyd could be due to a shift to AK as the major dAdo phosphorylating enzyme when dCK is inhibited, consistent with previous studies in kinase deficient human T lymphoblastoid cell lines (21). Alternatively, the addition of dCyd may be stimulating the formation of excess dTTP, which will in turn increase deoxynucleoside diphosphate reduction by ribonucleotide reductase (41,45), and allow more dADP and dATP accumulation. Clearly, some facets of these enzymes’ regulation are not well understood, and will need to be further studied to provide an explanation for the increased dATP accumulation when ADA and dCK are both inhibited.

Because both Ado and dAdo are elevated in ADA-deficient patients, it has been difficult to discern the relative contribution of Ado and dAdo in the toxicity to developing lymphocytes. Although the primary focus in more recent years has been on the effects of aberrant dAdo metabolism, some studies have suggested a possible role for Ado in ADA deficiency through the action of Ado receptors and blocking of NF-κB activity (46,47). Studies with murine FTOCs convincingly ruled out a major role for Ado in inhibition of thymocyte development under ADA-deficient conditions (13). Our own studies also do not support a role for Ado in the inhibition of human thymocyte development in dCF-treated hu/moFTOC, as adenosine receptor antagonists failed to protect from the consequences of ADA deficiency and adenosine receptor agonists had no appreciable effect on thymocyte development (data not shown). Furthermore, rescue of dCF-treated hu/mo FTOC with a combination of dCyd and an AK inhibitor should increase intracellular Ado concentrations. Thus, while it is possible that Ado signaling through AdoR could play a role in immunomodulation of the few surviving T and B cells in the periphery of ADA-deficient patients (48), it is less likely that Ado has a major impact on development of T cells in the thymus.

It is also highly unlikely that SAH hydrolase inhibition, as occurs in the RBCs of ADA-deficient patients (39), has a large impact on thymocyte development during ADA deficiency. SAH hydrolase remained inhibited under ADA-inhibited conditions where dATP accumulation was prevented and development was rescued by the use of deoxynucleoside kinase inhibitors (Figure 6). Furthermore, when murine thymocyte development was assessed in FTOC under conditions of inhibited methylation, thymocyte development was perturbed not by apoptosis, but by inhibition of transcription of molecules needed for development, such as the TCR and CD4/CD8 (49). Inhibition of SAH hydrolase during ADA deficiency is therefore likely to be a consequence, but not a major cause of the pathology induced by aberrant dAdo metabolism during thymocyte development.

Treatments for ADA deficiency usually entail a bone marrow transplant (BMT), or if a suitable donor is not available, enzyme replacement therapy using pegylated-bovine ADA enzyme (PEG-ADA). While the best chance for a cure is provided by BMT, this is often not a feasible option. Although initially efficacious, treatment of ADA-deficient patients with PEG-ADA results in low long-term lymphocyte restoration, with chronic deterioration of T cell responses (50). Further, a recent report has revealed that a high proportion of BMT-treated ADA-deficient patients are now experiencing progressive neurological abnormalities, indicating that hematopoietic reconstitution is insufficient to completely correct the systemic metabolic abnormalities associated with lack of ADA enzyme activity in all other organ systems (51). Although it is unknown whether the mechanism(s) of neurotoxicity is similar to that of the dATP-induced apoptosis occurring in lymphocytes, autopsy material from an ADA-deficient patient clearly showed accumulation of dATP in non-lymphoid tissues such as brain (52).

Our studies provide rationale for consideration of an additional therapeutic alternative for ADA-deficient patients: treatment with deoxynucleoside kinase inhibitors. Deoxycytidine tested in ADA deficient patients was systemically nontoxic (44). Adenosine kinase inhibitors are currently being developed for treatments of various neurological manifestations such as stroke, as AK is the main enzymatic activity responsible for the regulation of extracellular adenosine levels (53) and adenosine is known to be neuroprotective. Interestingly, the AK inhibitor used in our study, 5′A5′dAdo, lacks in vivo efficacy due to its deamination by ADA (15); clearly, this would be not be an issue in ADA-deficient patients. Thus, treatment with deoxynucleoside kinase inhibitors could be a useful adjunct to PEG-ADA therapy and/or BMT and might ameliorate the neurotoxicity associated with lack of ADA activity in the central nervous system.

Acknowledgments

L.F.T. holds the Putnam City Schools Distinguished Chair in Cancer Research. The authors thank Drs. Paul Kincade and Justin Van De Wiele for critical review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- Ado

adenosine

- ADA

adenosine deaminase

- dAdo

2′-deoxyadenosine

- 5′A5′dAdo

5′-amino-5′-deoxyadenosine

- dCF

2′-deoxycoformycin

- dCyd

2′-deoxycytidine

- DN

double negative

- DP

double positive

- EDP

early double positive

- ISP

immature single positive

- PEG-ADA

pegylated bovine adenosine deaminase

- SAH

S-adenosylhomocysteine

- TCRβic

intracellular TCRβ

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants F32 HD008709 (M.L.J.), HD36044 (L.F.T.), and AI43572 (M.R.B.) and was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant C06 RR14570-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Parts of this work were presented in the Purine and Pyrimidine Society Meeting, July 2007 in Chicago, ILL.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an author-produced version of a manuscript accepted for publication in The Journal of Immunology (The JI). The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. (AAI), publisher of The JI, holds the copyright to this manuscript. This manuscript has not yet been copyedited or subjected to editorial proofreading by The JI; hence it may differ from the final version published in The JI (online and in print). AAI (The JI) is not liable for errors or omissions in this author-produced version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the United States National Institutes of Health or any other third party. The final, citable version of record can be found at www.jimmunol.org.

References

- 1.Giblett ER, Anderson JE, Cohen F, Pollara B, Meuwissen HJ. Adenosine-deaminase deficiency in two patients with severely impaired cellular immunity. Lancet. 1972;2:1067–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)92345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershfield MS, Mitchell BS. Immunodeficiency diseases caused by adenosine deaminase deficiency and purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency. In: Scriver CR, Sly WS, Childs B, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill, Inc.; New York: 2001. p. 2585. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackburn MR, Kellems RE. Adenosine deaminase deficiency: metabolic basis of immune deficiency and pulmonary inflammation. Adv Immunol. 2005;86:1–41. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linch DC, Levinsky RJ, Rodeck CH, Maclennan KA, Simmonds HA. Prenatal diagnosis of three cases of severe combined immunodeficiency: severe T cell deficiency during the first half of gestation in fetuses with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Clin Exp Immunol. 1984;56:223–232. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donofrio J, Coleman MS, Hutton JJ. Overproduction of adenine deoxynucleosides and deoxynucleotides in adenosine deaminase deficiency with severe combined immunodeficiency disease. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:884–887. doi: 10.1172/JCI109201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen A, Hirschhorn R, Horowitz SD, Rubinstein A, Polmar SH, Hong R, Martin DW., Jr Deoxyadenosine triphosphate as a potentially toxic metabolite in adenosine deaminase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:472–476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.1.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spits H. Development of αβ T cells in the human thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:760–772. doi: 10.1038/nri913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galy A, Verma S, Barcena A, Spits H. Precursors of CD3+CD4+CD8+ cells in the human thymus are defined by expression of CD34. Delineation of early events in human thymic development. J Exp Med. 1993;178:391–401. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dik WA, Pike-Overzet K, Weerkamp F, de Ridder D, de Haas EFE, Baert MRM, van der Spek P, Koster EEL, Reinders MJT, van Dongen JJM, Langerak AW, Staal FJT. New insights on human T cell development by quantitative T cell receptor gene rearrangement studies and gene expression profiling. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1715–1723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joachims ML, Chain JL, Hooker SW, Knott-Craig CJ, Thompson LF. Human alpha beta and gamma delta thymocyte development: TCR gene rearrangements, intracellular TCR beta expression, and gamma delta developmental potential--differences between men and mice. J Immunol. 2006;176:1543–1552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer A, Bosselut R. CD4/CD8 coreceptors in thymocyte development, selection, and lineage commitment: analysis of the CD4/CD8 lineage decision. Adv Immunol. 2004;83:91–131. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)83003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson LF, Van De Wiele CJ, Laurent AB, Hooker SW, Vaughn JG, Jiang H, Khare K, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Hershfield MS, Resta R. Metabolites from apoptotic thymocytes inhibit thymopoiesis in adenosine deaminase-deficient fetal thymic organ cultures. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1149–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI9944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van De Wiele CJ, Vaughn JG, Blackburn MR, Ledent C, Jacobson M, Jiang H, Thompson LF. Adenosine kinase inhibition promotes survival of fetal adenosine deaminase-deficient thymocytes by blocking dATP accumulation. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:395–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI15683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van De Wiele CJ, Joachims ML, Fesler AM, Vaughn JG, Blackburn MR, McGee ST, Thompson LF. Further differentiation of murine double-positive thymocytes is inhibited in adenosine deaminase-deficient murine fetal thymic organ culture. J Immunol. 2006;176:5925–5933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ugarkar BG, DaRe JM, Kopcho JJ, Browne CE, III, Schanzer JM, Wiesner JB, Erion MD. Adenosine kinase inhibitors. 1. Synthesis, enzyme inhibition, and antiseizure activity of 5-iodotubercidin analogues. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2883–2893. doi: 10.1021/jm000024g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullman B, Gudas LJ, Cohen A, Martin DW., Jr Deoxyadenosine metabolism and cytotoxicity in cultured mouse T lymphoma cells: a model for immunodeficiency disease. Cell. 1978;14:365–375. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carson DA, Kaye J, Wasson DB. Differences in deoxyadenosine metabolism in human and mouse lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1980;124:8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder FF, Lukey T. Purine ribonucleoside and deoxyribonucleoside metabolism in thymocytes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;122B:259–264. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8559-2_42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arner ES, Eriksson S. Mammalian deoxyribonucleoside kinases. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;67:155–186. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurley MC, Lin B, Fox IH. Regulation of deoxyadenosine and nucleoside analog phosphorylation by human placental adenosine kinase. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1986;195(Pt B):141–149. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-1248-2_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershfield MS, Fetter JE, Small WC, Bagnara AS, Williams SR, Ullman B, Martin DW, Jr, Wasson DB, Carson DA. Effects of mutational loss of adenosine kinase and deoxycytidine kinase on deoxyATP accumulation and deoxyadenosine toxicity in cultured CEM human T-lymphoblastoid cells. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:6380–6386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hershfield MS, Kredich NM. Resistance of an adenosine kinase-deficient human lymphoblastoid cell line to effects of deoxyadenosine on growth, S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inactivation, and dATP accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4292–4296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullman B, Levinson BB, Hershfield MS, Martin DW., Jr A biochemical genetic study of the role of specific nucleoside kinases in deoxyadenosine phosphorylation by cultured human cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:848–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plum J, De Smedt M, Verhasselt B, Kerre T, Vanhecke D, Vandekerckhove B, Leclercq G. Human T lymphopoiesis: in vitro and in vivo study models. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:724–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spits H, Res P, Jaleco AC. Techniques for studying development of human natural killer cells and T cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;121:25–38. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-044-6:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agarwal RP, Spector T, Jr, Parks RE. Tight-binding inhibitors-IV. Inhibition of adenosine deaminases by various inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1977;26:359–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(77)90192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Res P, Blom B, Hori T, Weijer K, Spits H. Downregulation of CD1 marks acquisition of functional maturation of human thymocytes and defines a control point in late stages of human T cell development. J Exp Med. 1997;185:141–151. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yssel H, De Vries JE, Koken M, Van Blitterswijk W, Spits H. Serum-free medium for generation and propagation of functional human cytotoxic and helper T cell clones. J Immunol Methods. 1984;72:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakamiya M, Blackburn MR, Jurecic R, McArthur MJ, Geske RS, Cartwright J, Jr, Mitani K, Vaishnav S, Belmont JW, Kellems RE, Finegold MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr, Bradley A, Caskey CT. Disruption of the adenosine deaminase gene causes hepatocellular impairment and perinatal lethality in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3673–3677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den BR, Boor PP, van Lochem EG, Hop WC, Langerak AW, Wolvers-Tettero IL, Hooijkaas H, van Dongen JJ. Flow cytometric analysis of the Vbeta repertoire in healthy controls. Cytometry. 2000;40:336–345. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20000801)40:4<336::aid-cyto9>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hori T, Cupp J, Wrighton N, Lee F, Spits H. Identification of a novel human thymocyte subset with a phenotype of CD3- CD4+ CD8α+β-. Possible progeny of the CD3- CD4- CD8- subset. J Immunol. 1991;146:4078–4084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coleman MS, Donofrio J, Hutton JJ, Hahn L. Identification and quantitation of adenine deoxynucleotides in erythrocytes of a patient with adenosine deaminase deficiency and severe combined immunodeficiency. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:1619–1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang JC, Cortopassi GA. dATP causes specific release of cytochrome C from mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1998;250:454–457. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnermi ES, Wang X. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou H, Li Y, Liu X, Wang X. An APAF-1 cytochrome c multimeric complex is a functional apoptosome that activates procaspase-9. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11549–11556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma DDF, Sylwestrowicz TA, Granger S, Massaia M, Franks R, Janossy G, Hoffbrand AV. Distribution of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and purine degradative and synthetic enzymes in subpopulations of human thymocytes. J Immunol. 1982;129:1430–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bohman C, Eriksson S. Deoxycytidine kinase from human leukemic spleen: preparation and characteristics of homogeneous enzyme. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4258–4265. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kredich NM, Hershfield MS. S-adenosylhomocysteine toxicity in normal and adenosine kinase deficient lymphoblasts of human origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:2450–2454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.5.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hershfield MS, Kredich NM, Ownby DR, Buckley R. In vivo inactivation of erythrocyte S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase by 2’-deoxyadenosine in adenosine deaminase-deficient patients. J Clin Invest. 1979;63:807–811. doi: 10.1172/JCI109367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thompson LF, Blackburn MR. At last-Experimental models for adenosine deaminase deficiency. The Immunologist. 1998;6:72–75. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen A, Barankiewicz J, Lederman HM, Gelfand EW. Purine and pyrimidine metabolism in human T lymphocytes:Regulation of deoxyribonucleotide metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12334–12340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joachims ML, Marble P, Knott-Craig C, Pastuszko P, Blackburn MR, Thompson LF. Inhibition of Deoxynucleoside Kinases in Human Thymocytes Prevents dATP Accumulation and Induction of Apoptosis. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27:816–820. doi: 10.1080/15257770802146270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Uckun FM, Gaynon PS, Sensel MG, Nachman J, Trigg ME, Steinherz PG, Hutchinson R, Bostrom BC, Sather HN, Reaman GH. Clinical features and treatment outcome of childhood T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia according to the apparent maturational stage of T-lineage leukemic blasts: a Children’s Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2214–2221. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cowan MJ, Wara DW, Ammann AJ. Deoxycytidine therapy in two patients with adenosine deaminase deficiency and severe immunodeficiency disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1985;37:30–36. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(85)90132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox RM, Tripp EH, Tattersall MH. Mechanism of deoxycytidine rescue of thymidine toxicity in human T-leukemic lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1718–1721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hershfield MS. New insights into adenosine-receptor-mediated immunosuppression and the role of adenosine in causing the immunodeficiency associated with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:25–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minguet S, Huber M, Rosenkranz L, Schamel WW, Reth M, Brummer T. Adenosine and cAMP are potent inhibitors of the NF-kappa B pathway downstream of immunoreceptors. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:31–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Apasov SG, Blackburn MR, Kellems RE, Smith PT, Sitkovsky MV. Adenosine deaminase deficiency increases thymic apoptosis and causes defective T cell receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:131–141. doi: 10.1172/JCI10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benveniste P, Zhu W, Cohen A. Interference with thymocyte differentiation by an inhibitor of S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. J Immunol. 1995;155:536–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan B, Wara D, Bastian J, Hershfield MS, Bohnsack J, Azen CG, Parkman R, Weinberg K, Kohn DB. Long-term efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for adenosine deaminase (ADA)-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) Clin Immunol. 2005;117:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Honig M, Albert MH, Schulz A, Sparber-Sauer M, Schutz C, Belohradsky B, Gungor T, Rojewski MT, Bode H, Pannicke U, Lippold D, Schwarz K, Debatin KM, Hershfield MS, Friedrich W. Patients with adenosine deaminase deficiency surviving after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation are at high risk of CNS complications. Blood. 2007;109:3595–3602. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-034678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coleman MS, Danton MJ, Philips A. Adenosine deaminase and immune dysfunction. Biochemical correlates defined by molecular analysis throughout a disease course. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;451:54–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb27096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boison D. Adenosine kinase, epilepsy and stroke: mechanisms and therapies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]