Abstract

Musashi1 (Msi1) is a highly conserved RNA-binding protein with pivotal functions in stem cell maintenance, nervous system development, and tumorigenesis. Despite its importance, only three direct mRNA targets have been characterized so far: m-numb, CDKN1A, and c-mos. Msi1 has been shown to affect their translation by binding to short elements located in the 3′-untranslated region. To better understand Msi1 functions, we initially performed an RIP-Chip analysis in HEK293T cells; this method consists of isolation of specific RNA-protein complexes followed by identification of the RNA component via microarrays. A group of 64 mRNAs was found to be enriched in the Msi1-associated population compared with controls. These genes belong to two main functional categories pertinent to tumorigenesis: 1) cell cycle, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, and apoptosis and 2) protein modification (including ubiquitination and ubiquitin cycle). To corroborate our findings, we examined the impact of Msi1 expression on both mRNA (transcriptomic) and protein (proteomic) expression levels. Genes whose mRNA levels were affected by Msi1 expression have a Gene Ontology distribution similar to RIP-Chip results, reinforcing Msi1 participation in cancer-related processes. The proteomics study revealed that Msi1 can have either positive or negative effects on gene expression of its direct targets. In summary, our results indicate that Msi1 affects a network of genes and could function as a master regulator during development and tumor formation.

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs)4 play a central role in the modulation of post-transcriptional events that involve splicing, transport, localization, stability, and translation of mRNAs. RBPs can be classified as either general or specific. Specific RBPs interact with a small subset of mRNAs and can have a restrictive pattern of expression, e.g. being expressed only in certain tissues or during specific developmental stages (reviewed in Refs. 1, 2). Some subsets of functionally related mRNAs may be co-regulated by specific RBPs, thereby setting the basis for the “RNA-operon” model (3, 4). One group of specific RBPs comprises “oncofetal” proteins, which play an important role during embryonic development. In adults, their expression is limited to stem and progenitor cells and in some instances are detected in tumor tissues. The coding region determinant-binding protein falls into this category. Transgenic mice overexpressing coding region determinant-binding protein in mammary glands developed tumors in 95% of the cases, suggesting that coding region determinant-binding protein is a proto-oncogene (5). Another RBP with a similar pattern of expression and phenotype is Musashi1 (Msi1), which is the focus of our study.

Musashi (Msi) is conserved across species (6) and may have a critical function in stem cell maintenance and self-renewal capability (6–10). In mammals, Msi1 is mainly expressed in stem and progenitor cells from different tissues (11–13), and a decrease occurs as cells commit to lineage differentiation (11, 14). Overexpression of Msi1 in oligodendrocyte (15) and mammary (16) precursors induces cell proliferation, arrests differentiation, and prevents apoptosis.

High levels of Msi1 have been found in different malignancies and, in certain cases, a correlation between Msi1 expression and a cancer cell's proliferative activity has been proposed. Further, small interference RNA-mediated Msi1 knockdown affects cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation and prevents cells from growing as xenographs (9, 17).

The preferential binding motif of Msi1 (G/A)UnAGU (n = 1–3) has been determined by SELEX (Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential enrichment) (18). Three direct Msi1 mRNA targets containing this motif in their 3′-UTRs have been identified so far: m-numb (18) and CDKN1A (19) in mammals and c-mos in Xenopus laevis (20). Binding of Msi1 to this regulatory element has been shown to modulate mRNA translation either blocking it in the cases of the mammalian targets m-numb and CDKN1A, or enhancing it in the case of X. laevis target c-mos (18–20). In mammalian cells, Msi1 represses m-numb 5′-cap-dependent translation by competing with eIF4G for PABP binding (21); the mechanism by which Msi1 activates c-mos translation in X. laevis has yet to be determined.

Based on what is known for other specific RBPs, we hypothesize that the three known Msi1 targets represent a small fraction of the RNAs regulated by this protein. To further elucidate the role of Msi1 in stem cell biology and tumor growth, a high throughput study to identify Msi1-associated RNAs is required. In this regard, RIP-Chip (Ribonomics) is the best approach available. In this method, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes containing the protein of interest are isolated via precipitation or immunoprecipitation (IP), and the associated RNAs are isolated and identified by microarray analysis (22, 23). This technology has been successfully used to identify RNA targets of numerous RBPs in different organisms (reviewed in Refs. 2, 24, 25).

Here, RIP-Chip was used to investigate Msi1. The analysis of 64 Msi1 preferentially associated mRNAs showed that Msi1 is likely to be involved in regulation of cell cycle, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and post-translational modification. Transcriptomic analysis supports these findings.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids—Msi1 and GFP open reading frames were PCR-amplified and cloned into the pShrek vector (23) downstream of the biotin acceptor peptide (BAP) coding sequence. pCMV3.1 (Invitrogen) expressing birA gene was previously generated (23). The 3′-UTRs of the genes BTG3, CD164, RCN2, and UBE2E3 were PCR-amplified and cloned into pGL3 (Promega, Madison, WI) in forward and reverse orientations in the XbaI site. Another plasmid was produced from the BTG3 3′-UTR clone by deleting a putative Msi1 binding site (GTAGT) located in position 1000–1004 (NM_006806).

Tissue Culture and Transient Transfection—HEK293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals Inc., Lawrenceville, GA), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Herndon, VA). HEK293T cells were transfected using Gene Jammer (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, the cells were plated in 150-mm plates coated with 0.001% polylysine, grown in media supplemented with 1 mm biotin (Research Organics, Cleveland, OH) to 50–60% confluence and co-transfected with 7 μg of BirA and 14 μg of the BAP-tagged protein-encoding plasmids.

Cell Lysate Preparation and Isolation of RNP Complexes—A detailed explanation of the procedures to harvest the cells, prepare the extract, and conduct the precipitation of RNA-protein complexes is described in a previous study (23). The obtained RNA samples were evaluated on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) as per the manufacturer's protocol.

Western Blot Analysis and Precipitation Western—50 μg of protein extract was run on 10% Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (Upstate, Temecula, CA) as described before (23). For precipitation Western blots, we performed the isolation of RNP complexes, SDS-PAGE, and Western blots as described above with minor modifications. After washing with NT2 buffer, beads were re-suspended in 1 volume of 2× SDS-loading buffer, heated for 10 min at 95 °C, and 20 μl of sample was analyzed.

Sample Preparation for Microarray Analysis (Transcriptomics)—293T cells were transfected either with the BAP-GFP or the BAP-Msi1 constructs as described before. 48 h post-transfection, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and harvested. For RNA preparation, cells were treated with TRIzol as recommended by Invitrogen (protocol for total RNA isolation) and re-purified with the RNeasy kit from Qiagen.

Microarray Analysis—200 ng of each RNA sample was labeled with Cy3/Cy5 dye using Agilent Low RNA Input Linear Amplification kit as per the manufacturer's protocols. To avoid dye-specific bias effects we used the dye-swap design in both RIP-Chip and gene expression experiments. After amplification, 750 ng each of Cy3- and Cy5-labeled RNA were combined and hybridized to an Agilent Human 1A oligonucleotide gene expression array. A two-color microarray-based gene expression analysis protocol (Agilent) was used. Microarrays were scanned using the Agilent Microarray Scanner G2565AA and extracted using Agilent feature Extraction Software version 9.1.

Microarray Data Analysis (RIP-Chip)—Analyses of microarray data were done using the packages in Bioconductor such as marray, arrayQuality, limma, and arrayMagic. First, array quality was assessed by constructing a MA plot and RG (red/green) density plot and other quality diagnostic plots. The arrays were then background corrected using “Edwards” method. Within array normalization was achieved using “loess” normalization and a “quantile” normalization method was used for between array normalization. To detect genes that are enriched in the Msi1 population, the LIMMA model was used (26). Both 3-fold enrichment in Msi1 array signal compared with controls and a spot intensity equal or higher than the average microarray spot intensity were established as thresholds for target identification. Adjusted false discovery rate p values were calculated for all the selected genes based on the LIMMA model and the null hypothesis of equal expression.

Microarray Data Analysis (Gene Expression)—A similar analysis was done for the gene expression microarrays. First, the quality of the arrays was evaluated through several diagnostic plots and hierarchical clustering. Then, background was corrected using the “normexp + offset” method (27). For within and between arrays normalizations “loess” and “Aquantile” methods were applied, respectively. Differential expression was assessed through linear models and Bayes' methods by using the LIMMA model (26). We established a threshold of 2-fold enrichment or reduction in Msi1 expression compared with control, with an adjusted FDR p values below 0.05.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR—Primers for qRT-PCR (supplemental File S1) were designed using Primer3 (28) and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Samples were analyzed using an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system and Power SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, 20 ng of RNA was reverse transcribed in a one-step qRT-PCR reaction using the MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems) and a gene-specific primer. All reactions were performed in quadruplicate. Following amplification, the ABI 7500 real-time software was used to determine the relative concentration of each mRNA using the ΔΔCt method. In the validation of RIP-Chip data, Mrsp5, a gene displaying a consistent 1:1 intensity ratio in the microarrays (BAP-Msi1 versus BAP-PABP1) was used as endogenous control for normalization.

RNA Decay Assay of Msi1-associated mRNAs—HEK293T cells were transfected as before with either BAP-Msi1 or BAP-GFP. After growth for 24 h, RNA polymerase II activity was inhibited using α-amanitin (Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. At different time points, RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX) and resuspended in nuclease-free water (Ambion). qRT-PCR reactions were performed as above. The gene expression data were normalized to 18 S rRNA expression and analyzed by the ΔΔCt methodology.

Analysis of Secondary Structure of the 3′-UTR of Msi1-associated mRNAs—We applied EDscan (29) to determine well ordered folding sequences, by calculating Zscre scores along the sequence by moving windows of sizes 40, 60, 80, and 100 nucleotides by steps of 5 nucleotides. Zscre = (Ediff - Ediff(w))/stdw, where Ediff(w) and stdw are the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of the Ediff scores computed by sliding a fixed-length window in steps of 5 nucleotides from the 5′ to the 3′ end of a sequence. Ediff = Ef - E, where E is the lowest free energy of the locally folded segment, and Ef is the lowest free energy of the structure that is computed under the condition that all base pairs formed in the minimum structure are prohibited. We looked for significant EDscan scores in the vicinity of Msi1 binding sites and determined the structures in the identified sites.

Gene Ontology and Pathway Analysis—The biological function (Gene Ontology) of the Msi1 preferentially associated mRNAs identified by microarray analysis was determined by using DAVID (Data base for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery) (30) and by the Pathway Studio 6.0 software (Ariadne Genomics, Inc., Rockville, MD), an automated text-mining tool based on published literature from various sources. Pathway Studio software was also used to interpret, build, and visualize biological networks.

MS-based Proteomics Analysis—Transfection of HEK293T cells with either the BAP-GFP or BAP-Msi1 was performed as described above. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. Cell extracts were prepared in two steps. Cells were lysed in a Dounce homogenizer with 1 volume of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and protease inhibitor, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min; the supernatant was recovered as the “cytoplasmic” fraction. Another volume of buffer was added to the pellet. Cells were sonicated and treated as above to collect the “pellet” fraction. Both fractions were analyzed as follows. Protein extracts were prepared for tandem mass spectrometry analysis using a standard protocol, which involves denaturation (45 min at 55 °C with 50% trifluoroethanol), cysteine oxidation (30 min at room temperature with 55 mm iodoacetamide), tryptic digest (with ∼1:50 to 1:100 w/w trypsin at 37C for 4.5 h), and sample clean-up using C18 tips (ThermoFinnigan, San Jose, CA), and Microcon-10 filters. Samples were injected 3–4 times into an LCQ-Orbitrap (ThermoFinnigan) mass spectrometer and analyzed in a 0 to 90% acetonitrile gradient over 5 h via reversed-phase chromatography on a Thermo BioBasic-18 column (100- × 0.10-mm inner diameter). Each of the runs was analyzed independently with Bioworks (ThermoFinnigan), searching a database of non-redundant human sequences obtained from ENSEMBL (31). The results were combined for analysis by PeptideProphet (32) and ProteinProphet (33), and then post-processed in the APEX pipeline (34, 35) to estimate absolute and differential protein expression based on spectral counts of the proteins of interest. We accepted proteins as confidently identified if their ProteinProphet probability was above a cutoff corresponding to <5% global FDR.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

RIP-Chip Analysis of Msi1 and Identification of Preferentially Associated mRNAs—We expect Msi1 to regulate a few hundred mRNAs (reviewed in Refs. 1, 4, 25) considering its involvement in complex processes such as stem cell maintenance and neuronal differentiation. As stated previously, only three Msi1 mRNA targets have been characterized in vertebrates. We decided to conduct a RIP-Chip analysis to identify novel Msi1 targets and to gain a better insight on the biological processes regulated by this protein. We chose to use HEK293T cells as a model system for several reasons. First, our approach was originally developed in this cell system and achieved excellent reproducibility for a variety of RBPs (23). Second, because high levels of Msi1 have been observed in different tumor samples and derived cell lines, we decided to use a cell line that allows exceptional levels of transfection and transgene expression. Third, CDKN1A, one of Msi1's described targets, was identified using this cell line and, recently, Kawahara et al. (21) used HEK293T as the model system to elucidate the mechanism by which Msi1 regulates translation in mammalian cells.

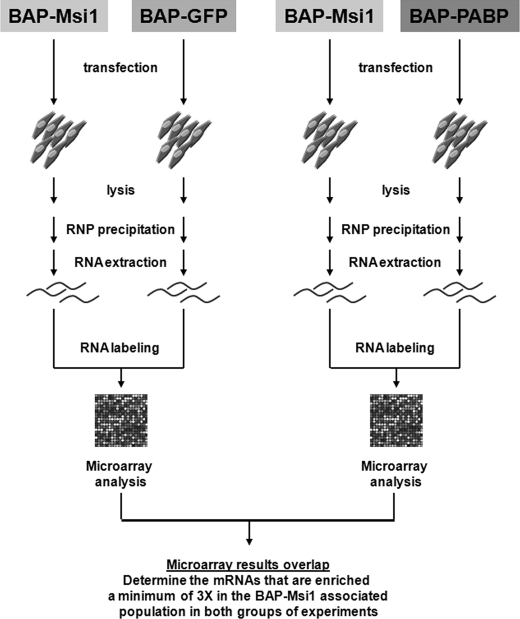

There are currently no standards regarding the way a RIP-Chip analysis should be conducted. Previous studies have been performed using either a tag strategy or antibodies against endogenous RBPs. There is also great variation in terms of controls and cut-off limits to define preferentially associated mRNAs (reviewed in Refs. 2, 4, 25). To increase confidence in our results, we conducted two parallel experiments with two different controls. In both cases, Msi1-associated mRNAs were expected to be enriched in the experimental samples compared with controls. Our two controls were green fluorescent protein (GFP) and Poly(A)-binding protein I (PABP1). Because GFP is not an RNA-binding protein and is not expressed in mammalian cells, we assume that the RNAs pulled down represent the background signal. In contrast, PABP1 is a protein that plays a key role in mRNA translation via its binding to their poly(A) tails. Previous data indicate that the “PABP1 profile” is very similar to the “transcriptomic profile” (36). Here we propose to use PABP1 IPs as a control for all polyadenylated mRNAs present in RNPs. This strategy is similar to the use of RNA polymerase II IPs in ChIP-Chip experiments to identify all genes in a sample with poised RNA polymerase (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic outline of the RIP-Chip analysis to identify Msi1 associated mRNAs. 293T cells were transfected transiently with BAP-tagged constructs. BAP-tagged proteins were biotinylated in vivo by the co-transfected E. coli BirA enzyme. RNPs were recovered via precipitation with streptavidin-Sepharose beads. Finally, RNAs were purified and analyzed on microarrays. We used a dual approach to identify Msi1 preferentially associated mRNAs. Two different controls (BAP-GFP and BAP-PABP1) were used in two independent sets of experiments. The results of the two sets of experiments were compared leading to the identification of 64 Msi1-associated mRNAs.

We conducted RIP-Chip experiments using a tag strategy. The biotin acceptor peptide (BAP) attached to the protein of interest was biotinylated in vivo by the Escherichia coli BirA enzyme, and then streptavidin-Sepharose beads were used to pull down and isolate RNP complexes (23). Two groups of experiments were carried out. In both cases, the “experimental sample” represents the transfection with the BAP-Msi1 construct. One control sample was derived from cells transfected with the BAP-GFP construct, whereas the second control was derived from cells transfected with the BAP-PABP1 construct. In all cases, a plasmid expressing the birA gene was co-transfected to assure biotinylation of the BAP tags (Fig. 1).

Because high protein recovery dictates the success of a RIP-Chip analysis, we first performed a precipitation Western blot to determine the levels of tagged protein recovery via streptavidin-Sepharose bead precipitation. Experiments were carried out with the BAP-Msi1 and BAP-GFP constructs; BAP-PABP1 was described and characterized previously (23). Recovery of both BAP-GFP and BAP-Msi1 from cell extract was highly successful (supplemental File S2). Subsequently, we measured RNA recovery using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer to verify that the tagged proteins behaved as expected. Starting from 1 ml of cell lysate (∼20 mg of total protein), the amount of RNA we typically recovered after precipitation with streptavidin-Sepharose beads was ∼15 μg for BAP-PABP1, ∼4 μg for BAP-Msi1, and 500 ng for BAP-GFP, in agreement with the properties of the three proteins used in our analysis.

RNAs were then amplified and labeled as described under “Experimental Procedures” to probe human 22K Agilent arrays. Each set of experiments included four microarrays, two technical replicates of BAP-Msi1 versus control (BAP-GFP or BAP-PABP1) for each dye orientation. We used default statistical parameters to define mRNAs that are preferentially associated with BAP-Msi1. We conservatively established a 3-fold minimum average of enrichment, adjusted FDR p value < 0.00001, and spot (gene) intensity equal or above the average array signal as cut-off values. We compared the results from the two sets of experiments and identified 64 mRNAs that met threshold in both experiments (Table 1 and supplemental File S3). Noteworthy, 62 out of the 64 mRNAs contained at least one consensus binding site for Msi1 in the 3′-UTR.

TABLE 1.

Functional classification of Msi1-associated mRNAs

|

Symbol

|

Gene description

|

Biological

processa

|

Enrichmentbover

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAP-GFP | BAP-PABP1 | |||

| AASDHPPT | Aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase-phosphopantetheinyl transferase | Other | 3.20 | 3.25 |

| ACTR2 | ARP2 actin-related protein 2 homolog (yeast) | CC, APOP | 3.16 | 3.82 |

| AMD1 | Adenosylmethionine decarboxylase 1 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 4.03 | 3.09 |

| ANKRD46 | Ankyrin repeat domain 46 | Unknown | 3.15 | 3.37 |

| ARL6IP1 | ADP-ribosylation factor-like 6 interacting protein 1 | CC, DIFF, APOP | 5.07 | 8.20 |

| ARL6IP5 | ADP-ribosylation-like factor 6 interacting protein 5 | PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.52 | 3.10 |

| ATP6AP2 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal accessory protein 2 | Other | 3.03 | 3.49 |

| ATP6V1G1 | ATPase, H+ transporting, lysosomal 13 kDa, V1 subunit G1 | Other | 4.98 | 4.12 |

| BTG3 | BTG family, member 3 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.25 | 5.96 |

| C20orf30 | Chromosome 20 open reading frame 30 | Unknown | 5.64 | 5.15 |

| C4orf46 | Chromosome 4 open reading frame 46 | Unknown | 3.40 | 3.35 |

| C5orf15 | Chromosome 5 open reading frame 15 | Unknown | 3.33 | 4.38 |

| CCNG2 | Cyclin G2 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.32 | 3.06 |

| CD164 | CD164 molecule, sialomucin | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 4.22 | 3.97 |

| CDKN2A | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.15 | 3.11 |

| CKAP2L | Cytoskeleton-associated protein 2-like | Unknown | 4.26 | 3.24 |

| DEPDC1 | DEP domain containing 1 | CC | 3.48 | 3.41 |

| DHRS2 | Dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 2 | CC, PRO | 4.27 | 7.39 |

| ELOVL5 | ELOVL family member 5, elongation of long chain fatty acids | Other | 3.16 | 3.16 |

| ERH | Enhancer of rudimentary homolog (Drosophila) | CC | 3.59 | 3.23 |

| FAM76B | Family with sequence similarity 76, member B | Unknown | 3.02 | 3.74 |

| FBXO28 | F-box protein 28 | PM | 4.21 | 4.64 |

| GPR137B | G protein-coupled receptor 137B | Other | 3.63 | 4.40 |

| GRPEL2 | GrpE-like 2, mitochondrial (E. coli) | Other | 3.23 | 3.61 |

| H1F0 | H1 histone family, member 0 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.18 | 3.11 |

| HERPUD1 | Homocysteine-inducible, endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible, ubiquitin-like domain member 1 | PRO, DIFF, APOP, PM | 3.13 | 7.46 |

| HIGD1A | HIG1 domain family, member 1A | APOP | 3.60 | 3.47 |

| HIST2H4B | Histone cluster 2, H4b | Other | 3.23 | 3.15 |

| HSBP1 | Heat shock factor-binding protein 1 | Other | 3.84 | 3.59 |

| HSD17B6 | Hydroxysteroid (17-β)-dehydrogenase 6 homolog (mouse) | CC, PRO, APOP | 3.45 | 4.68 |

| KIAA0101 | Hypothetical protein LOC9768 | CC, PRO, APOP | 6.96 | 3.40 |

| LBR | Lamin B receptor | CC, PRO, DIFF | 3.22 | 6.11 |

| OSAP | Ovary-specific acidic protein | Other | 3.17 | 3.09 |

| OSTM1 | Osteopetrosis-associated transmembrane protein 1 | Other | 3.02 | 6.28 |

| PIGF | Phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis, class F | PRO, DIFF, PM | 4.40 | 3.37 |

| PKNOX1 | PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 1 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.41 | 3.86 |

| PMAIP1 | Phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.72 | 3.51 |

| PSPH | Phosphoserine phosphatase | Other | 3.55 | 3.13 |

| PTBP2 | Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 2 | CC, PRO, DIFF | 3.47 | 3.61 |

| PTP4A1 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 | CC, PRO, DIFF, PM | 3.15 | 5.04 |

| RAB11A | RAB11A, member RAS oncogene family | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.35 | 5.15 |

| RABGGTB | Rab geranylgeranyltransferase, β subunit | PM | 3.09 | 4.06 |

| RCN2 | Reticulocalbin 2, EF-hand calcium binding domain | DIFF | 4.35 | 6.23 |

| RNF11 | Ring finger protein 11 | PM | 3.09 | 5.30 |

| RNF138 | Ring finger protein 138 | PM | 3.20 | 3.97 |

| RNF146 | Ring finger protein 146 | Other | 3.05 | 3.58 |

| SCML1 | Sex comb on midleg-like 1 (Drosophila) | Other | 3.67 | 4.02 |

| SGPP1 | Sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphatase 1 | DIFF, APOP | 3.05 | 4.46 |

| SLC16A1 | Solute carrier family 16, member 1 (monocarboxylic acid transporter 1) | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.13 | 4.26 |

| SNX10 | Sorting nexin 10 | Other | 3.26 | 4.72 |

| SPCS2 | Signal peptidase complex subunit 2 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | PM | 4.08 | 5.37 |

| SRP14 | Signal recognition particle 14 kDa (homologous Alu RNA-binding protein) | Other | 4.36 | 3.14 |

| STMN1 | Stathmin 1/oncoprotein 18 | CC, PRO, DIFF, APOP | 3.76 | 4.18 |

| TCEA1 | Transcription elongation factor A (SII), 1 | PRO, DIFF | 3.13 | 4.31 |

| TIGD2 | Tigger transposable element derived 2 | Other | 3.14 | 3.02 |

| TMCO1 | Transmembrane and coiled-coil domains 1 | Unknown | 6.26 | 4.55 |

| TMEM165 | Transmembrane protein 165 | Unknown | 3.57 | 3.27 |

| TMEM188 | Transmembrane protein 188 | Unknown | 3.38 | 3.16 |

| TMEM209 | Transmembrane protein 209 | Unknown | 3.36 | 3.50 |

| TOMM20 | Translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 20 homolog (yeast) | DIFF | 3.07 | 3.87 |

| TSNAX | Translin-associated factor X | CC, PRO, DIFF | 3.63 | 3.19 |

| TSPAN3 | Tetraspanin 3 | PRO | 3.00 | 5.81 |

| UBE2E3 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2E 3 (UBC4/5 homolog, yeast) | PRO, APOP, PM | 5.68 | 3.78 |

| WTAP | Wilms tumor 1-associated protein | CC, PRO, APOP | 3.48 | 3.52 |

Biological process abbreviations: APOP, apoptosis; CC, cell cycle; DIFF, differentiation; PM, protein modification; and PRO, proliferation

Microarray enrichment in BAP-Msi1 over BAP-GFP and BAP-PABP1 samples

To validate the results from the microarray analysis, we selected a group of 20 genes enriched in the BAP-Msi1-associated mRNA population; NUMB, a previously identified Msi1 target (absent in the microarray) was also included as a control. qRT-PCR confirmed an enrichment of 21 tested RNA species in the BAP-Msi1-associated population compared with BAP-PABP1 control (supplemental File S4).

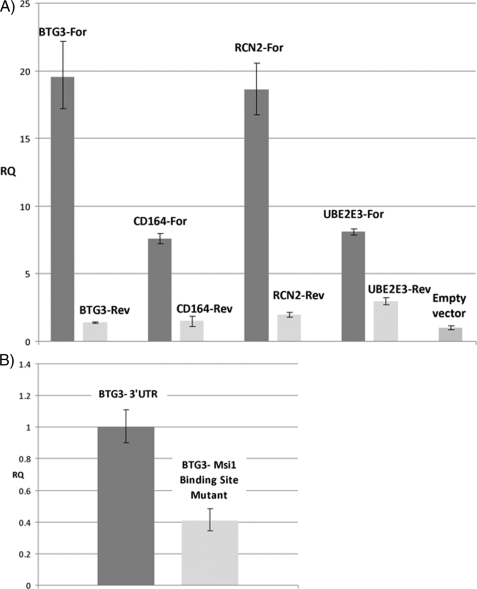

The Msi1 Binding Site—Binding of Msi1 to its target mRNAs is very likely to occur in the 3′-UTR. To prove that, we prepared forward and reverse Msi1-associated mRNAs 3′-UTR (BTG3, RCN2, CD164, and UBE2E3) constructs in pGL3 and co-transfected these into HEK293T along with BAP-Msi1 and BirA and the appropriate empty vector controls. 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested, and the mRNAs associated with BAP-Msi1 were recovered with streptavidin beads as described before. The amount of mRNA associated with BAP-Msi1 was determined for each construct by qRT-PCR using a common primer set to amplify expressed vector sequences. We used the gene TCEA1, determined to be highly associated with Msi1, as a normalization control. As can be seen in Fig. 2A a large enrichment in mRNA recovery was observed in relation to the “reverse” control as well as against the empty vector (pGL3). In a follow-up experiment, we deleted a putative Msi1 binding site from the clone expressing the 3′-UTR of BTG3 in forward orientation. The resulting and the original clone were used in a transfection/precipitation experiment as above. Deletion of the putative Msi1 binding site had an impact on BAP-Msi1-mediated pull down (Fig. 2B). However, other binding sites might exist in the 3′-UTR of BTG3, because the effect observed was weaker than the one seen for the 3′ UTR in reverse orientation.

FIGURE 2.

BAP-Msi1 targets 3′-UTR of identified mRNAs. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing the 3′-UTR of identified BAP-Msi1-associated mRNAs in the forward (for) and reverse (rev) orientation. mRNAs associated with BAP-Msi1 were recovered by precipitation with streptavidin-Sepharose beads. In each case, the amount of mRNA expressed by the clone included in the BAP-Msi1-associated population was evaluated by qRT-PCR and are relative to empty vector (pGL3). B, in a similar strategy, we evaluated how the mRNA recovery of the BTG3 3′-UTR (for) clone is affected if a putative Msi1 binding site is deleted. It was observed that deleting this sequence decreases mRNA recovery relative to the wild type. All comparisons are statistically significant with a p value < 0.01.

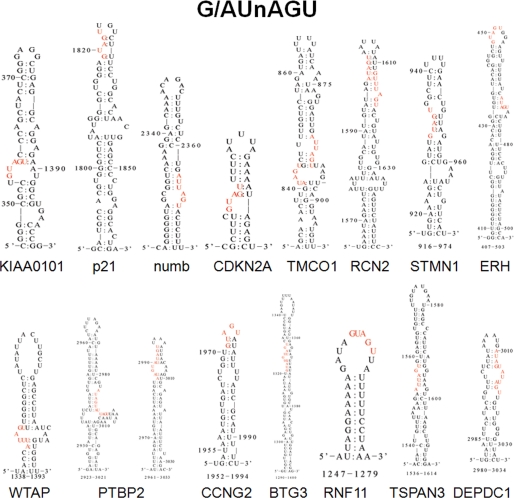

The Msi1 preferential binding motif was determined by SELEX analysis to be (G/A)UnAGU, where n = 1–3 (18). We searched a dataset of 20,840 validated 3′-UTR sequences of human transcripts (37) and identified ∼8,000 transcripts containing at least one putative Msi1 binding site. It is unlikely that Msi1 regulates all these mRNAs. It is probable that the sequence by itself is not enough to allow Msi1 binding but requires secondary structure elements. To determine if there is a tendency of Msi1 binding sites to be associated with any particular structure, we applied EDscan (29) to predict the secondary structure of associated mRNAs identified by RIP-Chip. We observed that Msi1 consensus sequence tends to be located in a hairpin structure (Fig. 3). Although these data are indicative, a more detailed characterization of the dependence of Msi1 binding and secondary structure is necessary.

FIGURE 3.

Msi1 consensus binding site is preferentially located in hairpin like structures. We applied EDscan (29) to determine well ordered folding sequences (secondary structure) of the mRNAs that were determined to be preferentially associated with Msi1. In particular, we checked if the putative Msi1 binding sites (48) present in the 3′-UTR preferentially form a specific type of structure. We observed that several of the putative Msi1 binding sites mapped to a hairpin type of structure as the examples illustrated in this figure.

Considering the involvement of Msi1 in stem cell biology, neural differentiation, and tumor growth, the use of methods to alter its expression levels or function could have therapeutic value. The use of small competitor molecules that mimic Msi1 binding sites could be a possible alternative. To design such competitors, a precise characterization of the sequences and structures implicated in Msi1 binding and function is essential (1).

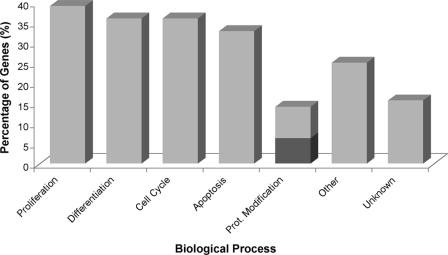

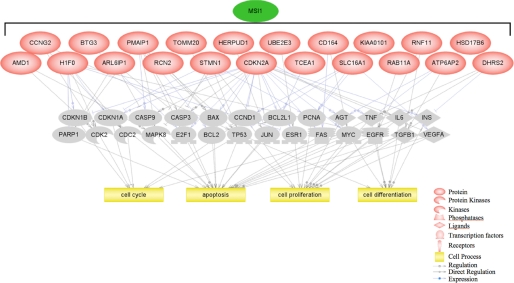

Biological Function of Identified Msi1-associated RNAs—We utilized Gene Ontology and literature mining to investigate the nature of the Msi1-associated mRNAs identified by RIP-Chip, in particular DAVID (30) and Pathway Studio 6.0 software (Ariadne Genomics, Inc.) were used for this purpose. We used the Fisher exact test with p value ≤ 0.05 and set a gene frequency (gene count assigned to an annotation term) of ≥2% as the threshold to select over-represented Gene Ontology biological processes. We found enrichment in the biological processes cell cycle (p = 0.016; 12.5% gene frequency) and mitochondrion organization and biogenesis (p = 0.031; 4.7% gene frequency) along with enrichment in the p53 signaling pathway (p = 0.015; 4.7% gene frequency). In-depth literature mining with Pathway Studio revealed that a high percentage of the Msi1-associated genes are involved in cell proliferation (39%), cell differentiation (36%), cell cycle (36%), apoptosis (33%), and protein modification (14%) (Table 1 and Fig. 4); all being biological processes that regulate crucial cellular functions and whose de-regulation is commonly observed in cancer. We then used the Pathway Studio to find common targets of the proteins encoded by Msi1-associated mRNAs. The pathway shown in Fig. 5 was built by searching for interactions among the proteins encoded by Msi1-associated mRNAs and potential downstream targets with a proven participation (above 500 citations in literature) in cell cycle, apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation. For that purpose, we used the algorithms “expression” and “regulation” to filter the relations.

FIGURE 4.

Biological processes classification of Msi1-associated mRNAs. Msi1-associated mRNAs were annotated to the Gene Ontology term “Biological Processes” using the web-based tool DAVID (30) and Pathway Studio software (Ariadne Genomics, Inc.). We found that ∼60% of our mRNAs (38 genes) were related to the following five biological processes: cell proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle, apoptosis, and protein modification (including protein ubiquitination and ubiquitin cycle; marked in dark gray). The remaining Msi1-associated mRNAs (∼40% of the genes) were either related to different (25%; 16 genes) or unknown (16%; 10 genes) biological processes. Note that the same gene may be assigned to more than one process, and thus the sum of the annotations will be above 100%.

FIGURE 5.

Pathway Studio diagrams (I). Pathway Studio software was used to find “expression” and “regulation” relations among the proteins encoded by the Msi1-associated mRNAs, downstream potential common targets (highlighted in gray) and biological processes. A schematic representation of the connectivity found is shown.

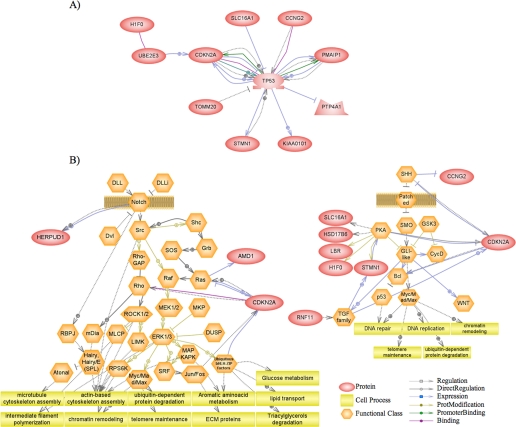

In a second analysis, we “added neighbors” as a way to identify genes that are linked to several of the proteins encoded by the Msi1-associated mRNAs. In other words, we wanted to identify a common node. TP53 (tumor suppressor p53) was determined to be the node with highest degree of connectivity (Fig. 6A). Based on the high number of references, we deduced a strong interaction between TP53 and the tumor suppressor CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A). This gene generates at least three alternatively spliced variants, encoding distinct proteins, two of which carry out CDK4 kinase functions and ARF, which is structurally unrelated to the others. The ARF protein can physically interact in binary or ternary complexes with TP53 and MDM2, and its overexpression results in TP53 stabilization and p53-dependent transcription activation (38–40). ARF is not activated directly by DNA damage, but rather by abnormal hyperproliferative signals, including oncoproteins (Myc, Ras, and v-abl) (41) and E2F-1 (42). Another identified gene with strong links to p53 is PMAIP1 (phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1). PMAIP1 was identified as a p53 transcriptional target implicated mainly in the response to UV and DNA damage (43, 44). An association between Msi1 and p53 pathway is consistent with previous finding, because Msi1 represses Numb and p21WAF translation; Numb enhances p53 stability (45), and the cell cycle regulator p21WAF is a key transcriptional target of p53. Indeed, our study presents evidence indicating that Msi1 and p53 activities are likely related.

FIGURE 6.

Pathway Studio diagrams (II). Pathway Studio software was used to (A) “add neighbors” to the proteins encoded by the Msi1-associated mRNAs. From all the entities identified, TP53 showed the highest connectivity. B, using Notch and Hedgehog pathway maps, included in Pathway Studio, we searched for interactions between their components and Msi1 direct targets. For this purpose, we used the “find direct interactions between selected entities and a group” algorithm.

Numb, one of the Msi1-identified targets, affects two important pathways: Notch and Sonic Hedgehog (SHH). Our recent findings (9) reinforced the connection between Msi1 and these pathways. We used Pathway Studio to further identify connections with these pathways applying the “find direct interactions between selected entities and a group” algorithm (Fig. 6B). Among the most important identified interactions was HERPUD1 (homocysteine-inducible, endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible, ubiquitin-like domain member 1), a Notch effector that acts as a transcriptional repressor (46). We found other potential links in the SHH pathway, especially to the transforming growth factor family and protein kinase A members. Moreover, cyclin G2 (CCNG2) is shown as a direct target of SHH, repressing its transcription.

Deregulation of the ubiquitin machinery components is common in cancer, thereby linking aberrant post-translational modification and cancer development (reviewed in Ref. 47). In our RIP-Chip analysis we found that 14% of the Msi1-associated mRNAs (nine genes) were involved in protein modification (Table 1 and Fig. 3) and ∼50% of them (FBXO28, RNF11, RNF138, and UBE2E3) were related to ubiquitin networks. Our results posit a possible connection between Msi1, ubiquitination, and the modulation of essential cellular processes.

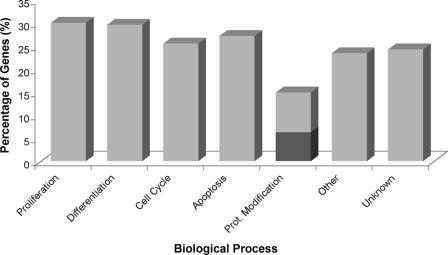

Analysis of Msi1 Downstream Effects—To corroborate our findings, we carried out several additional assays. First, a gene expression analysis was done to determine the indirect impact of Msi1 on the transcriptome. This particular study is important for a better visualization of the network of genes regulated by Msi1 and discerning of Msi1 mediated effects in tumor formation. We compared the RNA profile of BAP-GFP- and BAP-Msi1-transfected cells using Agilent 44K gene expression microarrays. We ran two sets of four microarrays (two biological replicates) of BAP-Msi1 versus control, hybridized in replicates for each dye orientation. 243 genes (absolute -fold change ≥2 and adjusted p value <0.05) were determined to be differentially expressed between BAP-Msi1 and BAP-GFP (supplemental File S5). We expected to see an agreement between RIP-Chip and transcriptomic results in terms of gene ontology distribution, because most of the changes observed in the transcriptomic profile should be driven by the action of genes identified in the RIP-Chip analysis. The results represented in Fig. 7 and supplemental File S5 confirm this expectation by showing a strong link between Msi1 and cell cycle/proliferation/differentiation and apoptosis. Moreover, resembling the RIP-Chip results, we also determined a strong connection with p53 (supplemental File S6A). We also discerned a link between a subset of genes that respond to Msi1 overexpression and Notch and SHH pathways (supplemental File S6B) in agreement with our recent findings (9).

FIGURE 7.

Functional classification of genes that respond to Msi1 expression. Genes were annotated to the Gene Ontology term “Biological Processes” using the web-based tool DAVID (30) and Pathway Studio software (Ariadne Genomics, Inc.). We found that 52% (127 genes) were related to the following 5 biological processes: cell proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle, apoptosis, and protein modification (including protein ubiquitination and ubiquitin cycle; marked in dark gray). The remaining Msi1-associated mRNAs (around 48% of the genes) were either related to different (23%; 57 genes) or unknown (24%; 59 genes) biological processes. Note that the same gene may be assigned to more than one process, and thus the sum of the annotations will be above 100%.

Msi1 Affects Translation and mRNA Stability—To establish a connection between Msi1 binding and function (impact on protein production), we transfected HEK293T cells with either BAP-GFP or BAP-Msi1 and characterized their protein expression using a mass spectrometry-based method called APEX (34). About 2500 proteins were detected; among them were 19 proteins from the list of Msi1 preferentially associated mRNAs obtained by RIP-Chip. Of these 19 proteins, 8 showed >2-fold expression changes in BAP-Msi1- versus BAP-GFP-transfected cell extracts (supplemental File S7). The complete data set for all identified ∼2,500 proteins is available from the authors. The most significant expression changes (p value<0.01) occurred in STMN1, a protein involved in tubulin destabilization and TMCO1, which is an uncharacterized membrane protein. Interestingly, changes in protein expression occurred in both directions suggesting that Msi1 can function either as repressor or activator of translation. This result does not come unexpectedly, because repression of translation was previously observed in the case of numb and p21 (18, 19), whereas activation was observed in the case of c-mos (20). Here we provide for the first time evidence that Msi1 can promote and repress protein expression in the same cell system. We suggest that characteristics of the mRNA and position of Msi1 binding sites might influence the type of effect (positive or negative) that is observed.

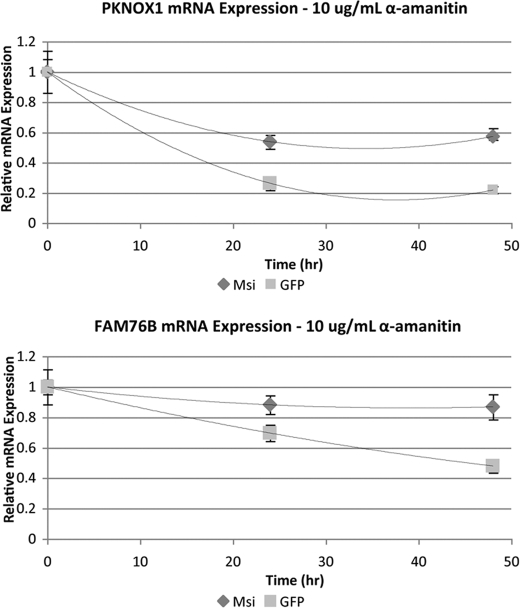

When comparing the RIP-Chip and the gene expression data, we observed that 12 genes identified in the RIP-Chip experiment also have significant mRNA expression changes (supplemental File S5). These differences in mRNA levels may be a direct consequence of Msi1 action. As with many RBPs that influence gene expression, Msi1 could act both at the levels of translation and decay. For all 12 mRNA species, expression levels were higher in the BAP-Msi1-transfected cells than in the control, suggesting that Msi1 prevents mRNA degradation. We selected PKNOX1 and FAM76B genes to test this hypothesis. We transfected HEK293T cells with either BAP-GFP or BAP-Msi1; 24 h post-transfection, we blocked transcription by treating the cells with α-amanitin and measured mRNA levels over a period of 48 h. In both cases, we observed that Msi1 contributed to a slower decay of the mRNAs (Fig. 8). This is a novel function for Msi1; it remains now to be determined mechanistically how Msi1 operates. One possibility is that Msi1 competes with micro RNAs and affects their interaction with mRNAs by blocking or modifying the structure of their binding site.

FIGURE 8.

PKNOX1 and FAM76B mRNA stability measured over 48 h following transfection with BAP-Msi or BAP-GFP. HEK293T cells were transfected with 1 μg of BAP-Msi (♦) or BAP-GFP (▪). After 24 h, RNA polymerase II activity was inhibited with α-amanitin (10 μg/ml), and the decay of the transcript was assessed at time 0, 24 h, and 48 h. Total RNA was extracted and the levels of mRNA were assessed by qRT-PCR. In the presence of Msi1, the mRNA for both PKNOX1 and FAM76B decayed at a slower rate than in the presence of the control transfection, GFP. After 48 h we observed a significant difference (p value<0.01) in the mRNA levels, suggesting that Msi1 stabilizes the transcript. Each data point represents the means from triplicate samples normalized to 18 S rRNA, relative to time 0.

In sum, our observations are consistent with the “RNA-operon” model, because a high number (∼60%) of the Msi1-associated targets appeared to be related to a small number of functional groups; a similar pattern is observed for downstream targets. In addition, a strong connection was found between Msi1-associated mRNAs and cell cycle, proliferation, cell differentiation, apoptosis, and protein modification as well as with members of p53, Notch, and SHH pathways; thereby supporting the hypothesis that Msi1 functions as a master regulator in stem cell biology and tumor growth.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program, NCI, Center for Cancer Research. This work was also supported by the San Antonio Area Foundation (Grant PGID122760), the San Antonio Cancer Institute, the American Cancer Society (Grant PGID 124139), and the Tengg Foundation (Grant PGID 127793).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Files S1–S7.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: RBP, RNA-binding protein; Msi1, Musashi1; UTR, untranslated region; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; PABP, Poly(A)-binding protein; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; IP, immunoprecipitation; GFP, green fluorescent protein; BAP, biotin acceptor peptide; CMV, cytomegalovirus; SELEX, systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment; SHH, Sonic Hedgehog.

References

- 1.McKee, A. E., and Silver, P. A. (2007) Cell Res. 17 581-590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanchez-Diaz, P., and Penalva, L. O. (2006) RNA Biol. 3 101-109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keene, J. D., and Tenenbaum, S. A. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 1161-1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keene, J. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Genet. 8 533-543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tessier, C. R., Doyle, G. A., Clark, B. A., Pitot, H. C., and Ross, J. (2004) Cancer Res. 64 209-214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakakibara, S., Nakamura, Y., Yoshida, T., Shibata, S., Koike, M., Takano, H., Ueda, S., Uchiyama, Y., Noda, T., and Okano, H. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 15194-15199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higuchi, S., Hayashi, T., Tarui, H., Nishimura, O., Nishimura, K., Shibata, N., Sakamoto, H., and Agata, K. (2008) Mech. Dev. 125 631-645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaneko, Y., Sakakibara, S., Imai, T., Suzuki, A., Nakamura, Y., Sawamoto, K., Ogawa, Y., Toyama, Y., Miyata, T., and Okano, H. (2000) Dev. Neurosci. 22 139-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Diaz, P. C., Burton, T. L., Burns, S. C., Hung, J. Y., and Penalva, L. O. (2008) BMC Cancer 8 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siddall, N. A., McLaughlin, E. A., Marriner, N. L., and Hime, G. R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 8402-8407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakakibara, S., and Okano, H. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17 8300-8312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potten, C. S., Booth, C., Tudor, G. L., Booth, D., Brady, G., Hurley, P., Ashton, G., Clarke, R., Sakakibara, S., and Okano, H. (2003) Differentiation 71 28-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke, R. B. (2005) Cell Prolif. 38 375-386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakakibara, S., Imai, T., Hamaguchi, K., Okabe, M., Aruga, J., Nakajima, K., Yasutomi, D., Nagata, T., Kurihara, Y., Uesugi, S., Miyata, T., Ogawa, M., Mikoshiba, K., and Okano, H. (1996) Dev. Biol. 176 230-242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobson, N. R., Zhou, Y. X., Flint, N. C., and Armstrong, R. C. (2008) Glia 56 318-330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang, X. Y., Yin, Y., Yuan, H., Sakamaki, T., Okano, H., and Glazer, R. I. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 3589-3599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sureban, S. M., May, R., George, R. J., Dieckgraefe, B. K., McLeod, H. L., Ramalingam, S., Bishnupuri, K. S., Natarajan, G., Anant, S., and Houchen, C. W. (2008) Gastroenterology 134 1448-1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imai, T., Tokunaga, A., Yoshida, T., Hashimoto, M., Mikoshiba, K., Weinmaster, G., Nakafuku, M., and Okano, H. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 3888-3900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Battelli, C., Nikopoulos, G. N., Mitchell, J. G., and Verdi, J. M. (2006) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 31 85-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlesworth, A., Wilczynska, A., Thampi, P., Cox, L. L., and MacNicol, A. M. (2006) EMBO J. 25 2792-2801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawahara, H., Imai, T., Imataka, H., Tsujimoto, M., Matsumoto, K., and Okano, H. (2008) J. Cell Biol. 181 639-653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenenbaum, S. A., Carson, C. C., Lager, P. J., and Keene, J. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 14085-14090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penalva, L. O., and Keene, J. D. (2004) BioTechniques 37 604, 606, 608–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keene, J. D., and Lager, P. J. (2005) Chromosome Res. 13 327-337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halbeisen, R. E., Galgano, A., Scherrer, T., and Gerber, A. P. (2008) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65 798-813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth, G. K. (2004) Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3 Article 3 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ritchie, M. E., Silver, J., Oshlack, A., Holmes, M., Diyagama, D., Holloway, A., and Smyth, G. K. (2007) Bioinformatics 23 2700-2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozen, S., and Skaletsky, H. (2000) Methods Mol. Biol. 132 365-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le, S. Y., Chen, J. H., Konings, D., and Maizel, J. V., Jr. (2003) Bioinformatics 19 354-361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dennis, G., Jr., Sherman, B. T., Hosack, D. A., Yang, J., Gao, W., Lane, H. C., and Lempicki, R. A. (2003) Genome Biol. 4 P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flicek, P., Aken, B. L., Beal, K., Ballester, B., Caccamo, M., Chen, Y., Clarke, L., Coates, G., Cunningham, F., Cutts, T., Down, T., Dyer, S. C., Eyre, T., Fitzgerald, S., Fernandez-Banet, J., Graf, S., Haider, S., Hammond, M., Holland, R., Howe, K. L., Howe, K., Johnson, N., Jenkinson, A., Kahari, A., Keefe, D., Kokocinski, F., Kulesha, E., Lawson, D., Longden, I., Megy, K., Meidl, P., Overduin, B., Parker, A., Pritchard, B., Prlic, A., Rice, S., Rios, D., Schuster, M., Sealy, I., Slater, G., Smedley, D., Spudich, G., Trevanion, S., Vilella, A. J., Vogel, J., White, S., Wood, M., Birney, E., Cox, T., Curwen, V., Durbin, R., Fernandez-Suarez, X. M., Herrero, J., Hubbard, T. J., Kasprzyk, A., Proctor, G., Smith, J., Ureta-Vidal, A., and Searle, S. (2008) Nucleic Acids Res. 36 D707-D714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller, A., Nesvizhskii, A. I., Kolker, E., and Aebersold, R. (2002) Anal. Chem. 74 5383-5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesvizhskii, A. I., Keller, A., Kolker, E., and Aebersold, R. (2003) Anal. Chem. 75 4646-4658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu, P., Vogel, C., Wang, R., Yao, X., and Marcotte, E. M. (2007) Nat. Biotechnol. 25 117-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogel, C., and Marcotte, E. M. (2008) Nat. Protoc. 3 1444-1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penalva, L. O., Burdick, M. D., Lin, S. M., Sutterluety, H., and Keene, J. D. (2004) Mol. Cancer 3 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon, K., Ko, D., Doderer, M., Livi, C. B., and Penalva, L. O. (2008) RNA Biol. 5 255-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamijo, T., Weber, J. D., Zambetti, G., Zindy, F., Roussel, M. F., and Sherr, C. J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 8292-8297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pomerantz, J., Schreiber-Agus, N., Liegeois, N. J., Silverman, A., Alland, L., Chin, L., Potes, J., Chen, K., Orlow, I., Lee, H. W., Cordon-Cardo, C., and DePinho, R. A. (1998) Cell 92 713-723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang, Y., Xiong, Y., and Yarbrough, W. G. (1998) Cell 92 725-734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zindy, F., Eischen, C. M., Randle, D. H., Kamijo, T., Cleveland, J. L., Sherr, C. J., and Roussel, M. F. (1998) Genes Dev. 12 2424-2433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bates, S., Phillips, A. C., Clark, P. A., Stott, F., Peters, G., Ludwig, R. L., and Vousden, K. H. (1998) Nature 395 124-125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oda, E., Ohki, R., Murasawa, H., Nemoto, J., Shibue, T., Yamashita, T., Tokino, T., Taniguchi, T., and Tanaka, N. (2000) Science 288 1053-1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shibue, T., Takeda, K., Oda, E., Tanaka, H., Murasawa, H., Takaoka, A., Morishita, Y., Akira, S., Taniguchi, T., and Tanaka, N. (2003) Genes Dev. 17 2233-2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colaluca, I. N., Tosoni, D., Nuciforo, P., Senic-Matuglia, F., Galimberti, V., Viale, G., Pece, S., and Di Fiore, P. P. (2008) Nature 451 76-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iso, T., Kedes, L., and Hamamori, Y. (2003) J. Cell. Physiol. 194 237-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crosetto, N., Bienko, M., and Dikic, I. (2006) Mol. Cancer Res. 4 899-904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J., and Clarke, M. F. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 3983-3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.