Abstract

The transcriptional factor FoxO1 plays an important role in metabolic homeostasis. Herein we identify a novel transrepressional function that converts FoxO1 from an activator of transcription to a promoter-specific repressor of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) target genes that regulate adipocyte biology. FoxO1 transrepresses PPARγ via direct protein-protein interactions; it is recruited to PPAR response elements (PPRE) on PPARγ target genes by PPARγ bound to PPRE and interferes with promoter DNA occupancy of the receptor. The FoxO1 transrepressional function, which is independent and dissectible from the transactivational effects, does not require a functional FoxO1 DNA binding domain, but dose require an evolutionally conserved 31 amino acids LXXLL-containing domain. Insulin induces FoxO1 phosphorylation and nuclear exportation, which prevents FoxO1-PPARγ interactions and rescues transrepression. Adipocytes from insulin resistant mice show reduced phosphorylation and increased nuclear accumulation of FoxO1, which is coupled to lowered expression of endogenous PPARγ target genes. Thus the innate FoxO1 transrepression function enables insulin to augment PPARγ activity, which in turn leads to insulin sensitization, and this feed-forward cycle represents positive reinforcing connections between insulin and PPARγ signaling.

The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)2 plays a significant role in mediating insulin sensitivity (1). It is the molecular target for thiazolidinedione (TZD) anti-diabetic agents that improve insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and lipid homeostasis in vivo (2, 3). PPARγ heterodimerizes with the retinoid X receptor and binds to PPAR response elements (PPREs) in promoters of target genes. TZDs enhance insulin sensitivity by regulating PPARγ-mediated gene expression. PPARγ is enriched in adipose tissue, where it serves as an essential regulator of adipocyte differentiation and probably also maintenance of the mature adipocyte phenotype (4, 5). Data from tissue-specific knockout mice shows that PPARγ is necessary for the normal biological function of adipose tissue and adipocytes (6). PPARγ plays an essential role in mediating the effect of TZDs on insulin sensitivity (6).

FoxO1, also known as FKHR, together with two other homologs, FKHRL1 and AFX, belong to the FoxO subfamily of the forkhead transcription factor family, which includes a large array of transcription factors characterized by the presence of a conserved 110-amino acid winged helix DNA-binding domain (DBD) (7). FoxO subfamily members play important roles in a wide range of cellular processes, such as DNA repair, cell cycle control, stress resistance, apoptosis, and metabolism (8–10). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling, which is activated by insulin and certain cytokines and growth factors, phosphorylates each of the FoxO proteins at three different Ser/Thr residues (10). The phosphorylated FoxO proteins are exported from the nucleus and become sequestered in the cytoplasm, where they interact with 14-3-3 proteins.

FoxO1 is the most abundant FoxO isoform in insulin-responsive tissues such as liver, adipose, and muscle cells, and is negatively regulated by insulin stimulation. Impaired insulin signaling to FoxO1 provides an important component of the mechanism for the metabolic abnormalities of type 2 diabetes.

Besides PPARγ, FoxO1 also functions in the process of adipocyte differentiation, acting as an inhibitor of adipogenesis at an early phase of the differentiation program (11). FoxO1 haplo-insufficient mice are partially protected from high fat diet-induced insulin resistance and diabetes (11). FoxO1 was also reported to directly bind to and repress the PPARγ2 promoter (12) as well as PPARγ function (13). These findings suggest the possibility of cross-talk between the two transcription factors in fat tissue, but the mechanisms remain unknown.

In the present study, we identified FoxO1 as an insulin-regulatable PPARγ transrepressor in mature adipocytes. We performed in depth molecular studies and evaluated the physiologic relevance of the cross-talk between insulin and PPARγ signaling that is integrated by FoxO1 transrepression of PPARγ in adipose tissue.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials—Maintenance of HEK293, HIRc-B, and 3T3-L1 cells and differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells were performed as described (14, 15). Adipocytes were studied at 10–14 days post-differentiation.

Rosiglitazone was obtained from Pfizer, Inc. (La Jolla, CA). The following items were obtained commercially: insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-FKHR (H128) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), HA probe (153, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) monoclonal antibody and anti-PPARγ antibodies (Geneka/Active Motif, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and Cell Signaling Technology), Anti-phospho-FoxO1 (Ser-256) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-lamin A/C (346) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

The firefly luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3-AOX (AOX-Luc), reporters of mouse Gpd1 promoter containing either a wild-type or mutated PPRE, as well as expression vectors for human PPARγ2 (pcDNA-hPPARγ2), mouse PPARα (pCMV-PPARα), PPARβ/δ (pCMV-PPARβ/δ), and expression vectors for FLAG-mFoxO1 and FLAG-mFoxO1-CA (T24A, S253A, and S316A) chimeras were described previously (16–19). Expression vectors for FoxO1 LXXAA mutant were donated by Dr. Jun Nakae (20), and those for FoxO1-H215R mutants were donated by Dr. Kun-Liang Guan. FoxO1 serial deletions were made by PCR.

pG5-Luc, pBIND, and pACT expression vectors were obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). A full-length cDNA encoding wild-type human PPARγ2 was inserted in-frame into the pBIND vector to generate a pBIND-gal4-hPPARγ2 chimera. Expression vectors for pACT-vp16-mFoxO1 chimera were constructed previously (18).

Adenoviruses encoding wild-type, constitutively active (CA) mutant, and transactivationally dominant active (Δ256) FoxO1 were donated by Dr. Domenico Accili. Virus transductions were performed by incubation of d10 3T3-L1 adipocytes at a multiplicity of infection of 50 plaque-forming units/cell for 16 h.

Animals—C57BL/6J male mice that have been put on 60% high fat diet for 16 weeks as well as the control mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. In addition, the animal experiments were performed humanely under protocols approved by the University of California, San Diego.

Relative Luciferase Reporter Assay, Mammalian Two-hybrid Assay and Modified Mammalian One-hybrid Assays—These experiments were performed as previously described (18, 21, 22).

Coimmunoprecipitation—Coimmunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (18, 21). HIRC-B cells were seeded in 100-mm plates (1 × 106 cells/plate). After incubation for 24 h, the cells were co-transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA-FLAG-mFoxO1 and 10 μg of pcDNA-hPPARγ2 expression plasmids. Cells were starved overnight for 24 h after transfection and subsequently exposed to rosiglitazone or DMSO control in combination with insulin or phosphate-buffered saline control for 8 h. Soluble fractions of cell lysate were immunoprecipitated with either anti-PPARγ (E-8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or mouse IgG control, and immunoblotted with anti-FoxO1 antibody (H128, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Nuclear fractions of white adipose tissue fat cells were isolated using a nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit (Biovision, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were isolated stepwise, and the lack of inter-fraction cross-contamination was confirmed by measurement of Lamin A/C (nuclear fraction) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (cytoplasmic fraction).

RNA Interference—The small interference RNA against mouse FoxO1 (sequence available at supplemental Table S1), and scrambled control were purchased from Dharmacon Research Inc. (Lafayette, CO). On day 7 post-differentiation, 3T3-L1 adipocytes were electroporated with small interference RNA using the Gene Pulser XCell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Electroporated cells were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C prior to assays.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assays—ChIP assays were performed essentially as previously described (17, 23). Cells were treated with rosiglitazone or DMSO control in combination with insulin or phosphate-buffered saline for 4 h prior to cross-linking for 10 min with 1% formaldehyde. A mixture of PPARγ antibodies (E-8, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; #39338, Active Motif; and #2492, Cell Signaling) was used in combination for ChIP PPARγ. For FoxO1, FKHR (H128, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), HA-probe antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) were applied. DNA copies in immunoprecipitation samples were quantified by real-time PCR and normalized to input DNA control samples. Primer information is available at supplemental Table S1.

Real-time PCR—Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy columns (Qiagen). First strand cDNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The samples were run in 20-μl reactions using an MJ Research PTC-200 96 well thermocycler coupled with the Chromo 4 Four-Color Real-Time System (GMI, Inc., Ramsey, MN). Gene expression levels were calculated after normalization to the standard housekeeping gene RPS3 using the ΔΔCT method as described previously (24, 25), and expressed as relative mRNA levels compared with control. Primer information is available in supplemental Table S1.

Free Fatty Acid Measurements—Release of free fatty acid into the cell culture medium was quantified using an in vitro enzymatic colorimetric method assay kit, HR Series NEFA-HR (Wako Chemicals, Inc., Richmond, VA).

Statistical Analysis—Data were expressed as means ± S.D. and evaluated by Student's two-tailed t test or ANOVA, followed by post hoc comparisons with Fisher's protected least significant difference test. A p value cutoff of 0.05 was used to determine significance.

RESULTS

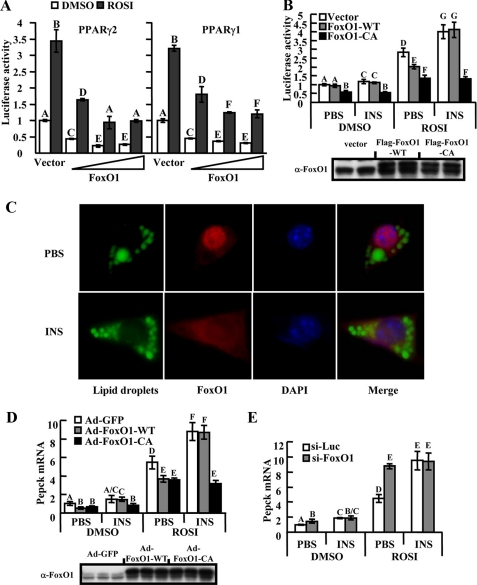

FoxO1 Represses PPARγ Transactivation—We evaluated the effects of FoxO1 on PPARγ2 (adipocyte dominant variant) transactivation by using relative luciferase reporter activity assays in HEK293 cells. Cells were co-transfected with pcDNA-hPPARγ2 and a luciferase-based PPARγ transactivation activity reporter (AOX-luc) together with increasing doses of a FoxO1 expression vector. As shown in Fig. 1A, FoxO1 inhibited agonist (rosiglitazone)- induced transcription from the AOX promoter in a dose-dependent manner. Transactivation of PPARγ1, the predominant isoform in tissues like muscle, macrophages, and liver, was also suppressed by FoxO1 (Fig. 1A, right panel).

FIGURE 1.

FoxO1 represses ligand-induced PPARγ transactivation. A, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with AOX-Luc, PPARγ2(left) or PPARγ1(right) and increasing amounts (0–150 ng/ml) of FoxO1. Cells were then treated with 1 μm rosiglitazone (ROSI) or solvent (DMSO) for 24 h prior to luciferase assay. B, HIRc-B cells were co-transfected with AOX-Luc, PPARγ2, and an equimolar amount of FoxO1-WT, FoxO1-CA, or control vector. Cells were then starved overnight and subsequently exposed to 1 μm ROSI, 100 ng/ml insulin (INS) or both together for 24 h before luciferase assay. Equal FoxO1 protein loading was confirmed (lower panel). C, immunofluorescent analysis of Ad-FoxO1-WT-transduced 3T3-L1 fat cells. Lipid droplets have been labeled with BODIPY 493/503 (green). FoxO1 was stained by anti-HA probe (red), and DNA was stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). Notice the nuclear localization of FoxO1 in starved cells and FoxO1 nuclear export following insulin stimulation. D, D10 3T3-L1 adipocytes infected with adenovirus (Ad-FoxO1-WT, Ad-FoxO1-CA, or Ad-GFP) were starved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 8 h followed by exposure to 1 μm ROSI, 100 ng/ml INS, or both prior to overnight incubation. Pepck mRNA levels were assayed by real-time PCR. Equal protein loading of FoxO1 was confirmed (lower panel). E, 3T3-L1 adipocytes were electroporated with control (siLuc) or anti-FoxO1 (siFoxO1) small interference RNA. 44 h later, cells were starved for 4 h and then treated as indicated for overnight incubation before Pepck mRNA assay. Data of triplicate results from at least three independent experiments are presented as the average ± S.D. (A, B, D, and E), and letters above the bars show statistical groups (ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Insulin Treatment Inhibits FoxO1 Suppression of PPARγ Transactivation—FoxO1 protein is a direct target of Akt kinase and insulin-dependent Akt activation leads to phosphorylation of FoxO1 with resultant nuclear exportation and cytoplasmic sequestration. This is the basis for the negative regulation of FoxO1 function by insulin. Therefore, insulin treatment should attenuate the inhibitory effects of FoxO1 on PPARγ transcription. To initially test this idea, we used pcDNA-hPPARγ2-transduced HIRc-B cells (Rat-1 fibroblasts overexpressing human insulin receptors), which is an established cell model for studies of insulin signaling (15), and these cells display robust insulin-induced phosphorylation of both endogenous and exogenous FoxO1 (supplemental Fig. S1a). As shown in Fig. 1B, rosiglitazone-induced PPARγ2 transactivation was suppressed by wild-type FoxO1 (FoxO1-WT), and more so by the constitutively active FoxO1 (FoxO1-CA, non-phosphorylatable mutant with all three Akt target residues replaced by alanine; specifically, T24A, S253A, and S316A). Importantly, insulin treatment enhanced rosiglitazone-induced PPARγ2 transactivation and completely abolished the suppressive effect of transduced FoxO1-WT. Strikingly, the suppressive effects of FoxO1-CA were not affected by insulin treatment. Control experiments excluded the possibility that FoxO1 inhibits AOX-Luc reporter activity independent of PPARγ (supplemental Fig. S1b). In addition, the suppressive effects of FoxO1 were specific to PPARγ, because FoxO1 did not inhibit transcriptional activity of either PPARα or PPARβ/δ (supplemental Fig. S1, c and d). Taken together, these data show that FoxO1 inhibits PPARγ-mediated transactivation events and that this negative regulatory effect is blocked by insulin treatment.

Insulin-FoxO1 Regulates Expression of Endogenous PPARγ Target Genes in Mature Adipocytes—To explore the physiological relevance of the effects of FoxO1 and insulin on the PPARγ transcriptional activity observed in the promoter assays, expression of endogenous PPARγ target genes was studied in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Firstly we demonstrated that insulin induces nuclear export of FoxO1 in mature adipocytes, as has been observed in hepatocytes. Thus, Fig. 1C shows that, in the basal state, FoxO1 immunostaining is largely conferred to the nucleus, whereas after insulin treatment, the great majority of FoxO1 relocalizes to the cytoplasm. Mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes, which express both endogenous PPARγ and FoxO1, were then infected with adenoviral vectors encoding either FoxO1-WT (Ad-FoxO1-WT) or FoxO1-CA (Ad-FoxO1-CA) and then treated with insulin, rosiglitazone, or both. Pepck is a well established PPARγ target gene in these cells, and Fig. 1D shows that rosiglitazone alone leads to a 5.4-fold increase in Pepck mRNA expression. Comparable to the AOX-luc promoter assay results, FoxO1-WT and FoxO1-CA inhibited rosiglitazone-induced Pepck mRNA expression. Furthermore, the suppressive effects of FoxO1-WT, but not FoxO1-CA, were abolished when cells were pre-treated with insulin. Comparable protein expression levels of the FoxO1 variants were confirmed by Western blotting. A comparable pattern of mRNA expression profiles was observed for other endogenous adipocyte PPARγ target genes, such as GyK, Gpd1, and Cap (see Fig. 5 and data not shown), whereas, FoxO1 was without effect on the non-PPARγ target gene Hsp47 (supplemental Fig. S1e).

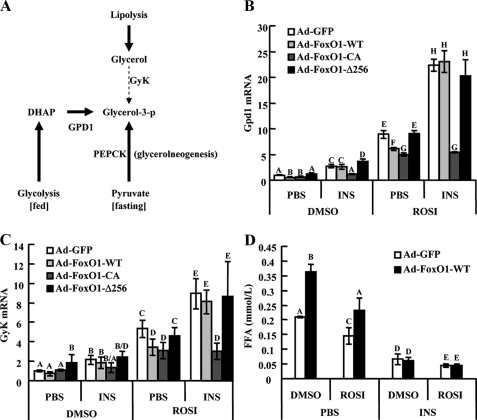

FIGURE 5.

FoxO1 transrepression integrates effects of insulin and PPARγ in adipocytes. A, summary of pathways leading to glycerol 3-phosphate production in mature adipocytes. B and C, D10 3T3-L1 adipocytes infected with Ad-FoxO1-WT, Ad-FoxO1-CA, Ad-FoxO1-Δ256, or Ad-GFP were starved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin for 8 h and further exposed to 1 μm rosiglitazone or DMSO control in combination with 100 ng/ml insulin or phosphate-buffered saline overnight. Expression of Gpd1 (B) and GyK (C) mRNA was assayed by real-time PCR. D, adipocytes were transduced with Ad-GFP or Ad-FoxO1-WT, then subjected to sequential starvation and 16 h treatment with ROSI or DMSO, in the presence or absence of insulin; isoproterenol was then applied to stimulate lipolysis, and free fatty acid release to the culture medium was measured. ROSI, rosiglitazone; INS, insulin. Data are presented as the average ± S.D. Letters above the bars show statistical groups (ANOVA, p < 0.05).

In Fig. 1D, insulin treatment of the Ad-GFP-transduced adipocytes led to an elevation of Pepck mRNA, especially in the presence of rosiglitazone. This is consistent with an effect of insulin mediated through endogenous FoxO1. To further explore this idea, we depleted the adipocytes of endogenous FoxO1 by RNA interference (supplemental Fig. S2a). In these cells, the effect of rosiglitazone to increase Pepck mRNA expression was enhanced, and insulin treatment was then without further stimulatory effect (Fig. 1E). To complement these experiments, we also achieved FoxO1 knockdown by expressing an anti-FoxO1 short hairpin RNA with a lentiviral vector and obtained similar results (supplemental Fig. S2, b–d). Thus, knockdown of endogenous FoxO1 mimics the insulin effect, indicating that insulin enhances PPARγ-mediated Pepck gene expression by negatively regulating endogenous FoxO1.

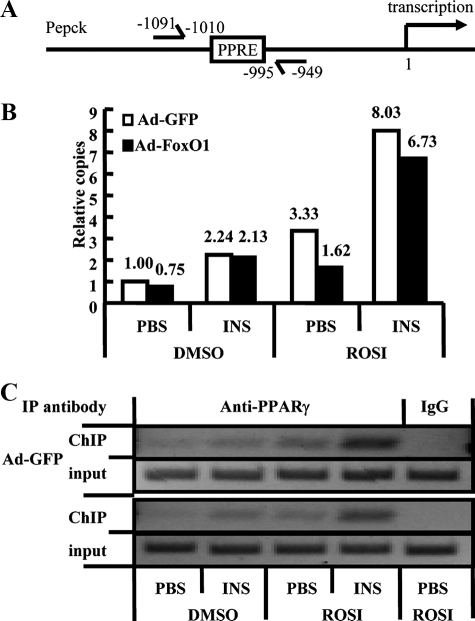

Insulin-FoxO1 Signaling Regulates PPARγ Occupancy of Pepck Promoter—To test whether FoxO1 inhibits PPARγ transactivation by interfering with the ability of PPARγ to interact with target gene promoter regions, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays to assess PPARγ occupancy of the Pepck promoter in the context of insulin-FoxO1 signaling.

3T3-L1 adipocytes were infected with Ad-FoxO1-WT or Ad-GFP and subsequently treated with insulin, rosiglitazone, or both together. Chromatin/transcription factor complexes were precipitated with a mixture of three anti-PPARγ antibodies, and real-time PCR was performed to quantify the relative number of immunoprecipitated Pepck promoter DNA copies, as previously described (17, 23). As shown in Fig. 2, a substantial amount of Pepck promoter segments were precipitated by anti-PPARγ antibodies in Ad-GFP DMSO control cells, and rosiglitazone alone induced significant (>3-fold) enrichment. Insulin treatment led to a further increase in Pepck promoter in both DMSO- and rosiglitazone-treated cells. In the absence of insulin, overexpression of FoxO1 significantly reduced promoter copy number in both DMSO- and rosiglitazone-treated cells, whereas insulin treatment greatly attenuated this suppressive effect. Thus, consistent with the mRNA profiles, the ChIP assays revealed that FoxO1 interferes with both basal and ligand-enhanced recruitment of PPARγ to the Pepck promoter and that insulin abolished FoxO1 inhibition.

FIGURE 2.

Insulin-FoxO1 signaling regulates PPARγ occupancy of Pepck promoter. A, schematic diagram of the mouse Pepck gene promoter region. The position of the PPRE and transcription start site is indicated. A pair of arrows indicates the PCR-amplified region. Adipocytes were infected with either Ad-GFP or Ad-FoxO1-WT and treated as indicated. Duplicate plates of cells were pooled for each condition. Soluble chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-PPARγ antibodies or normal IgG as control. Enrichment of PPRE-containing DNA sequences in the immunoprecipitated DNA pool, indicating association of PPARγ with the Pepck promoter within intact chromatin, was visualized by PCR (C, 35 cycles). Relative copies of immunoprecipitated Pepck promoter DNA versus input controls were further quantified by real-time PCR (B). ROSI, rosiglitazone; INS, insulin. Numbers above bars (B) show relative copies.

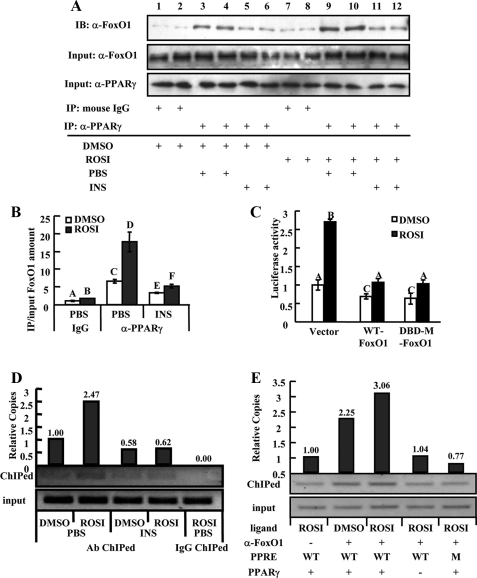

Physical Interaction between FoxO1 and PPARγ—Next, we examined whether there is a physical interaction between PPARγ and FoxO1 using coimmunoprecipitation assays. HIRc-B cells were co-transfected with pcDNA-FLAG-mFoxO1 and pcDNA-hPPARγ2 and treated with insulin, rosiglitazone, or both. As shown in Fig. 3A (upper panel), FoxO1 bands were readily detected in anti-PPARγ antibody precipitates. The band intensities were significantly enhanced by rosiglitazone (lanes 9–10 versus 3–4) and inhibited by insulin (lanes 5–6 versus 3–4, and lanes 11–12 versus 9–10). The relative amount of precipitated versus input FoxO1 in each group were quantified in the bar graph (Fig. 3B). A comparable pattern of association between endogenous FoxO1 and PPARγ was observed in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (supplemental Fig. S3a). These data suggest that FoxO1 can repress PPARγ via a direct protein-protein interaction and that this interaction is negatively regulated by insulin and positively regulated by rosiglitazone.

FIGURE 3.

FoxO1 is a PPARγ transrepresser. A, co-immunoprecipitation of PPARγ with FoxO1. HIRc-B cells co-transfected with PPARγ2 and FoxO1-WT were treated with INS (100 ng/ml), ROSI (1 μm), or both. Cell extracts were precipitated with anti-PPARγ (E-8) antibody and then immunoblotted with anti-FoxO1 antibody. Relative amounts of precipitated versus input FoxO1 in each group were quantitated (B). C, HIRc-B cells were co-transfected with FoxO1-WT, FoxO1-DBD (DBD mutant), or vector together with AOX-Luc and PPARγ2, then treated with 1 μm ROSI or DMSO control before luciferase assay. Data are presented as the average ± S.D. Letters above the bars show statistical groups (B and C, ANOVA, p < 0.05). D, D10 adipocytes were exposed to 1 μm ROSI, 100 ng/ml INS, or both, as indicated. Duplicate plates of cells were pooled for each condition. Soluble chromatin was immunoprecipitated with anti-FoxO1 antibody, and enrichment of Pepck PPRE-containing DNA sequence was visualized by PCR (35 cycles) and further quantified by real-time PCR. E, ChIP assays were performed in HIRc-B cells co-transfected with PPARγ2 and a Gpd1 promoter containing either a wild-type or mutated PPRE. Enrichment of Gpd1 PPRE-containing DNA sequences, visualized by PCR (25 cycles) and quantitated by real-time PCR, was induced by anti-FoxO1 antibody and further enhanced by ROSI but vanished when PPARγ was absent or the PPRE was mutated. Numbers above bars (D and E) show relative copies.

Further validation of this interaction was obtained by modified mammalian one-hybrid assays (supplemental Fig. S3b) and mammalian two-hybrid assays (supplemental Fig. S3, c and d). Thus, the results of the co-immunoprecipitation, one-hybrid, and two-hybrid experiments demonstrate a direct negative interaction between FoxO1 and PPARγ2, which is enhanced by rosiglitazone and inhibited by insulin treatment.

FoxO1 as a Transrepressor of PPARγ Transactivation—Because FoxO1 can serve as a transcription factor that directly interacts with specific response elements in promoter regions, we sought to determine whether its DBD contributes to the repression of PPARγ. FoxO1-DBD-M is a variant with a single amino acid substitution in the DBD (H215R) that abolishes FoxO1 transactivation (supplemental Fig. S4a). We found that the ability of this mutant to suppress PPARγ-mediated gene transcription was comparable to FoxO1-WT (Fig. 3C), suggesting that interaction of FoxO1 with its cognate DNA response element is not necessary for repression of PPARγ. This idea is further supported by the finding that transactivationally dominant negative FoxO1-Δ256 (a truncated mutant lacking the C-terminal transactivation domain) was without effect on PPARγ transactivation (as measured by endogenous gene expression (Pepck in supplemental Fig. S4b and GyK and Gpd1 in Fig. 5) or a reporter assay (data not shown)), consistent with the conclusion that FoxO1 DNA binding does not participate in PPARγ suppression.

The above data led us to hypothesize that FoxO1 is recruited to the PPRE by PPARγ and subsequently interferes with PPARγ DNA binding and gene transcription. We tested this idea by performing ChIP assays in 3T3-L1 adipocytes transduced with Ad-FoxO1-WT. Genomic DNA corresponding to the PPRE of the Pepck promoter was readily precipitated by anti-FoxO1 antibody (Fig. 3D), showing that FoxO1 and PPARγ associate at the PPARγ target gene promoter in vivo. Rosiglitazone treatment induced a marked increase in precipitated PPRE DNA copies, whereas insulin reduced the DNA copy number and inhibited the effect of rosiglitazone. Comparable results were observed when the promoter of another PPARγ target gene (Gpd1) was similarly studied (supplemental Fig. S4c). The specificity of these FoxO1 effects is supported by the data showing the absence of FoxO1 occupancy on the promoter of a non-PPARγ target gene, RPS3 (supplemental Fig. S4d). To further confirm that PPARγ mediates the association of FoxO1 with PPREs, we replicated the ChIP assays in HIRc-B cells transfected with a Gpd1 promoter containing either WT or a mutated PPRE. As demonstrated in Fig. 3E, FoxO1 was recruited to the WT PPRE in the presence of PPARγ, and this recruitment was enhanced by rosiglitazone treatment. On the other hand, recruitment was not detected when PPARγ was absent or when the PPRE was mutated, supporting the notion that functional PPARγ/PPRE association is critical for FoxO1 recruitment to the target gene promoter.

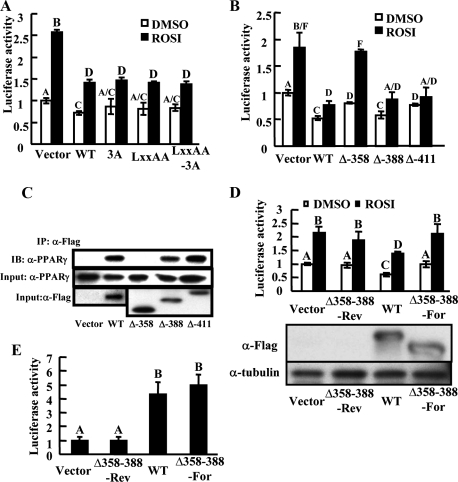

Mapping the Domain That Mediates FoxO1 Transrepression—Nuclear receptor cofactors bind to nuclear receptors via peptide motifs called nuclear receptor boxes with a consensus sequence of LXXLL (L, leucine; X, any amino acid) (26). A nuclear receptor box is present in the N terminus of FoxO1 and is conserved from mice (459LKELL463) to humans (452LKELL466) (20). We tested whether this motif mediates the transrepression of PPARγ. As shown in Fig. 4A, when LKELL was mutated to LKEAA, which is known to disrupt the interaction between FoxO1 and SIRT1 (20), the repressive effect on PPARγ transactivation was intact.

FIGURE 4.

Corresponding domain that mediates FoxO1 transrepression. A, effects of FoxO1 LXXLL motif mutation on PPARγ transactivation as assayed by the above-mentioned reporter system. B, effects of FoxO1 serial deletion mutants on PPARγ transactivation. C, physical interaction between deletion mutants of FoxO1 (FLAG fused) and PPARγ detected by co-immunoprecipitation in HIRc-B cells. D, effects of the internal deletion mutant of FoxO1 lacking aa358–388 (FoxO1-Δ358–388) on PPARγ transactivation. FoxO1-Δ358–388 was inserted into pcDNA-FLAG vector in either the forward (Δ358–388-For) or reverse orientation (Δ358–388-Rev, serves as a control). Protein loading was comparable (lower panel). E, transactivational function of FoxO1-Δ358–388 was monitored in HEK293 cells by a luciferase reporter driven by a promoter containing three copies of IGFBP1 insulin-responsive sequence (IRS) (3×IRS-Luc). Data are presented as the average ± S.D. Letters above the bars show statistical groups (ANOVA, p < 0.05).

We then conducted serial deletions to identify the domain that mediates FoxO1 transrepression. This approach showed that amino acids 358–388 comprise the putative domain that mediated both the transrepression and physical interaction with PPARγ (Fig. 4, B and C). Sequence alignment revealed that the amino acid sequence in this domain is highly conserved among FoxO1 in species ranging from worms to human (supplemental Fig. S5a). An internal deletion mutant lacking amino acids 358–388 (FoxO1-Δ358–388) abrogates the FoxO1 transrepressive effect (Fig. 4D). On the other hand, FoxO1-Δ358–388 is fully competent in transactivating a target FoxO1 promoter (Fig. 4E). Thus although the FoxO1 DBD mutant is inactive for transactivation but competent for transrepression, FoxO1-Δ358–388 is competent for transactivation but incompetent for transrepression. This shows that transrepression and transactivation are two independent dissectable intrinsic functions of FoxO1. The domain of amino acids 358–388 also contains one inverted and two atypical LXXLL motifs (LLDNL, LPSLS, and LNLL), consistent with the view that this conserved domain is critical for the transrepression function of FoxO1. However, point mutations or deletion of each of these individual putative motifs did not alter the repressive effect of FoxO1 on PPARγ, suggesting the whole 31-amino acid motif is required for the transrepression (supplemental Fig. S5, b and c).

FoxO1 Transrepression Integrates Insulin and PPARγ Signaling—The above data also suggested that, similar to transactivational function, the transrepression activity of FoxO1 is also regulatable by insulin-AKT signaling, which has potentially important physiological relevance. As an example, here we show that the insulin regulation of FoxO1 transrepression provides a molecular pathway that integrates insulin signaling and PPARγ function in fat tissue.

In mature adipocytes, both insulin and PPARγ promote triglyceride synthesis and restrain free fatty acid release. During fasting, lipolysis is activated, and it is estimated that 30–60% of the intracellular fatty acids liberated during lipolysis are re-esterified into newly synthesized triglycerides (27, 28). This re-esterification process requires glycerol 3-phosphate, which, in mature adipocytes, is derived mainly from lactate and pyruvate through the action of Pepck in a pathway termed glyceroneogenesis. To a greater less extent, GyK may also contribute to glycerol 3-phosphate production during fasting. In the fed state, adipocyte glycerol 3-phosphate is mainly produced from the glycolytic intermediate dihydroxyacetone phosphate through the action of Gpd1. All three of these key enzymes needed for glycerol 3-phosphate production are direct target genes of PPARγ in adipose tissue (Fig. 5A), and Fig. 5 (B and C) shows that rosiglitazone treatment increases Gdp1 and GyK expression, as it does Pepck (Fig. 1C). Importantly, transduction of adipocytes with FoxO1-WT represses the effect of rosiglitazone on these endogenous genes, and concomitant insulin treatment abolishes these transrepressive effects. On the other hand, while constitutively active FoxO1 also inhibits PPARγ-mediated transactivation, this effect is not inhibited by insulin treatment. Lastly, FoxO1-Δ256 was without effect (Fig. 5, B and C). These changes in gene expression patterns were comparable to the patterns of free fatty acid release. Thus, free fatty acid release from mature adipocytes was inhibited by rosiglitazone, and this effect was counteracted by FoxO1 expression in the absence of insulin (Fig. 5D). Insulin treatment suppressed free fatty acid release to low basal levels, as has been well documented in the literature, and importantly, also abolished the FoxO1 effect (Fig. 5D). In addition, FoxO1-CA showed a stronger ability to stimulate free fatty acid release than FoxO1-WT, whereas FoxO1-Δ256 was without effect (supplemental Fig. S6a).

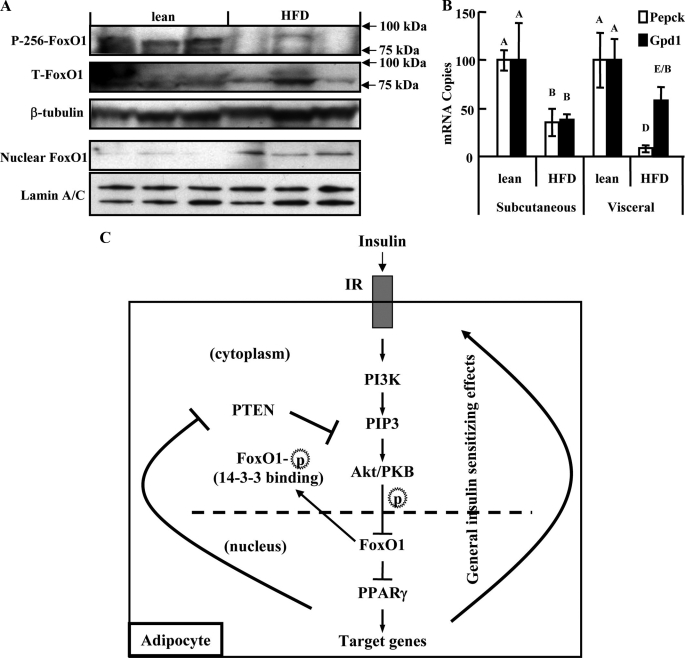

In Vivo Pathophysiological Significance of FoxO1 Transrepression—Fig. 6 (A and B) present data examining the potential in vivo effects of FoxO1 transrepression in adipose tissue. Insulin resistance is associated with decreased phosphorylation and increased nuclear accumulation of FoxO1 in the liver (29). In fat tissue from high fat diet-induced insulin-resistant mice, we observed similar findings, with reduced phosphorylation and greater nuclear accumulation of FoxO1 in visceral adipocytes harvested in the fed state (Fig. 6A). This observation was coupled to decreased mRNA expression of the PPARγ target genes Pepck and Gpd1 (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

In vivo pathophysiological significance of FoxO1 transrepression. A, phosphorylated (p-Ser256) and total FoxO1 were blotted in lysates of whole adipocytes derived from white adipose tissue of mice fed with either 60% high fat diet or control diet. FoxO1 was also blotted in the nuclear fraction of adipocytes from both groups of mice. B, mRNA expression of Pepck and Gpd1 in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues from each group of mice. Expression levels in lean mice were set to 100. Data are presented as the average ± S.D. Letters above the bars show statistical groups (ANOVA, p < 0.05, n = 3). C, proposed model for the cross-talk between insulin and PPARγ signaling. Insulin, following binding to its receptor, activates key downstream signaling substrates of the PI3K-Akt cascade. Akt, or a similar PIP3-dependent kinase, translocates to the nucleus and phosphorylates Ser-253, Ser-316, and Thr-24 of FoxO1. Phosphorylated FoxO1 may bind 14-3-3 proteins, triggering export to the cytoplasm. FoxO1 interacts with PPARγ in a manner that is enhanced by TZD chemicals such as rosiglitazone, and interferes with the ligand receptor-target gene promoter interaction, thereby shutting down PPARγ transactivation. Modification of FoxO1 by insulin-stimulated PI3K-Akt signaling weakens the FoxO1-PPARγ interaction and ameliorates the FoxO1 transrepression. Activation of PPARγ, in turn, enhances insulin-PI3K-Akt signaling tension via either general insulin sensitizing effects or direct inhibition of PI3K-Akt antagonizers such as phosphatase and tensin homolog. The transrepressional function of FoxO1 thus mediates a feed-forward circuit between PPARγ and insulin signaling in adipose tissue and could represent a fundamental biological process of adipocytes with important pathophysiological relevance.

DISCUSSION

FoxO1 is a prominent member of the FoxO subfamily of forkhead transcription factors and serves as an insulin regulatable transcription factor modulating the expression of a number of insulin-induced genes. In the current study, we have identified a novel function for FoxO1 as a potent transrepressor of PPARγ. We show that FoxO1 binds directly to PPARγ through protein-protein interactions, independent of DNA binding, and that FoxO1 represses PPARγ transactivation activity by inhibiting the association of PPARγ with its cognate DNA enhancer element. Importantly, insulin treatment leads to phosphorylation of FoxO1 causing nuclear exclusion and sequestration in the cytoplasm. Through this mechanism, insulin treatment relieves the transrepressive activity of FoxO1 on PPARγ, leading to enhanced PPARγ-mediated transactivation ability. This new mechanism of FoxO1 function provides a positive feed-forward system in which insulin treatment enhances PPARγ activity, which, in turn, leads to insulin sensitization (Fig. 6C).

Both FoxO1 and PPARγ are transcription factors, and, in general terms, the metabolic effects of FoxO1 involve stimulation of gluconeogenesis, lipolysis, and lipogenesis, and FoxO1 knockout mice have improved insulin sensitivity (11, 30). In this sense, the metabolic effects of FoxO1 may be considered prodiabetic. In contrast, PPARγ has well described actions to promote insulin sensitivity and is therefore anti-diabetic. Thus, understanding the molecular connections between these two transcription factors should provide a more integrated view of the relevant metabolic physiology. For example, FoxO1 binds to a DNA response element in the PPARγ2 promoter, leading to decreased PPARγ expression, suggesting regulatory connections between these two factors. Consistent with this concept, we observed down-regulation of PPARγ mRNA in mature adipocytes transduced with Ad-FoxO1-WT in the absence of rosiglitazone (supplemental Fig. S6b). The current studies also provide strong evidence that FoxO1 represses the intrinsic transactivational function of PPARγ, which is in line with a previous study indicating that overexpressed FoxO1 can suppress promoter activities mediated by ectopically expressed PPARγ (13). Here, we show new mechanisms integrating FoxO1 down-regulation of PPARγ activity. For example, FoxO1 directly binds to the PPARγ receptor through protein-protein interactions that do not involve FoxO1 association with DNA. This direct interaction was demonstrated through one-hybrid, two-hybrid, and co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Furthermore, our studies identified a 31-amino acid domain within FoxO1 that contains one inverted and two atypical LXXLL motifs, and this class of motif is known to interact with nuclear receptors. Based on ChIP assays, we show that interaction of FoxO1 with PPARγ leads to displacement of PPARγ from its cognate response elements on promoter regions of target genes, providing a mechanism for FoxO1 induced transrepression of PPARγ transactivation. This ability of FoxO1 to repress PPARγ transactivation was demonstrated using promoter/reporter assays in transduced cells, as well as in 3T3-L1 adipocytes where PPARγ effects on endogenous genes were suppressed by FoxO1. Importantly, insulin has robust effects on this system, because insulin treatment leads to activation of PI3K/Akt which, in turn, phosphorylates FoxO1 at Thr-24, Ser-253, and Ser-316. Phosphorylated FoxO1 is then excluded from the nucleus and sequestered in the cytosol where it associates with 14-3-3 proteins, explaining the effect of insulin to inhibit FoxO1 transactivation events. Consistent with this, we demonstrate that insulin treatment inhibits the repressive effects of FoxO1 on PPARγ transactivation. In support of the above concepts, we found that a constitutively active FoxO1, in which all three Akt phosphorylation sites are mutated, strongly represses PPARγ transactivation, and this effect is no longer inhibited by insulin treatment. In this way, insulin signaling inhibits FoxO1 function, leading to derepression of PPARγ transactivation. In turn, enhanced PPARγ activity would lead to heightened insulin sensitivity, providing a feed-forward interacting mechanism connecting insulin action and PPARγ transactivation through a reinforcing positive signaling program.

It should be noted that extracellular signals leading to mitogen-activated protein kinase activation can cause serine phosphorylation at position 112 in the A/B domain of PPARγ2, and this phosphorylation results in inhibition of PPARγ transactivation (31–35). Insulin itself can cause this modification of endogenous PPARγ by stimulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (32). However, in mature adipocytes, insulin actually enhances PPARγ function by inactivating the transrepressor FoxO1. In addition, the underlying mechanism by which serine 112 phosphorylation inhibits PPARγ2 function is that the modification in the A/B domain impairs ligand binding affinity of the ligand-binding domain (36). The effect of serine phosphorylation on transactivation becomes weaker with increasing ligand concentration and completely disappears when ligand concentration is saturating. The concentration of rosiglitazone (1 μm) used in the present study is saturating, and serine 112 phosphorylation should be without effect on PPARγ transactivation under these circumstances (36). Even with the possibility that there is some degree of serine 112 phosphorylation that attenuates the TZD effect, this is completely overcome by the enhanced PPARγ activation due to FoxO1 inactivation. In this event, the effects of insulin to increase PPARγ transactivation would be slightly underestimated in our studies making our conclusion about the FoxO1 transrepression even stronger. However, based on the studies by Shao et al. (36), because we use saturating concentrations of rosiglitazone, we think this is quite unlikely.

We found that the DBD mutant of FoxO1, which is transactivationally inactive, retains the full ability to transrepress PPARγ. On the other hand, a transrepression inactive FoxO1 mutant retains full FoxO1 transactivation ability. This demonstrates that FoxO1 has two distinct functions, which can be separated and functionally dissected. The transrepressive function of FoxO1 is DNA-independent, while the transactivation function of FoxO1 is independent of PPARγ and is mediated through FoxO1 binding to its cognate DNA response elements. Both functions of FoxO1 are inhibited by insulin.

It's of interest to note the differential regulation of the Pepck gene by insulin in liver versus adipose tissue. Insulin potently suppresses Pepck gene expression in liver, inhibiting gluconeogenesis. In adipose tissue, insulin increases Pepck gene expression by inhibiting FoxO1 transrepression of PPARγ, the major transcriptional activator of adipose Pepck, and this effect favors lipid synthesis and storage in adipocytes.

The finding that insulin can act through FoxO1 to augment TZD action may have clinical relevance with respect to anti-diabetic treatment. It is known that TZDs are often relatively less effective in more severe Type 2 diabetic patients who are under-insulinized. In addition, in clinical trials, the effects of TZDs, when used in combination with insulin or insulin secretagogue therapy, are more effective than when used alone (37, 38). This leads to the possibility that proper insulinization of diabetic patients to cause FoxO1 nuclear exclusion will enhance the clinical effectiveness of TZDs by relieving the suppressive effects of FoxO1 on PPARγ action. Perhaps this mechanism may provide an explanation for why 20–30% of diabetic patients do not respond to these agents. Consistent with this speculation, we have obtained evidence in mice indicating that FoxO1 haplo-insufficient animals are more responsive to the insulin-sensitizing effects of TZDs than are wild-type animals while on high fat diets.3

In addition to its role to transactivate a variety of target genes, PPARγ also can transrepress a set of pro-inflammatory genes, and recent evidence indicates that the anti-inflammatory effects of TZDs contribute to the insulin-sensitizing properties of this class of drugs (16, 39, 40). It will be important to determine whether the transrepressive properties of PPARγ are also inhibited by FoxO1 or whether the effects of FoxO1 are limited to suppression of PPARγ mediated gene activation.

In summary, FoxO1 can function as a transrepressor of PPARγ in adipose tissue through a direct protein-protein interaction. FoxO1 is recruited to the PPARγ receptor by rosiglitazone, and this interaction is inhibited by insulin. Although the proposed working model is derived from in vitro cell model systems and should be further validated by in vivo studies, the present study provides a molecular mechanism to integrate insulin signaling with the function of PPARγ, and the insulin-FoxO1-PPARγ axis may exert important physiological and pathophysiological effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Domenico Accili for providing the adenovirus encoding various FoxO1, Dr. Kun-Liang Guan for the FoxO1-H215R mutant plasmid, and Dr. Jun Nakae for FoxO1 LXXAA mutant plasmid. We thank Elizabeth J. Hansen for editorial assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DK 033651 and DK 074868 (to J. M. O.). This work was also supported by University of California Discovery Program Project bio03-10383 (BioStar) with matching funds from Pfizer Incorporated.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6 and Table S1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; TZD, thiazolidinedione; PPRE, PPAR response element; DBD, DNA-binding domain; CA, constitutively active; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; ANOVA, analysis of variance; WT, wild type; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ROSI, rosiglitazone; INS, insulin.

Kim, J. J., Li, P., Huntley, J., Chang, J. P., Orden, K. C., and Olefsky, J. M. (2009) Diabetes, in press.

References

- 1.Olefsky, J. M., and Saltiel, A. R. (2000) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 11 362-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehmann, J. M., Moore, L. B., Smith-Oliver, T. A., Wilkison, W. O., Willson, T. M., and Kliewer, S. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 12953-12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yki-Jarvinen, H. (2004) N. Engl. J. Med. 351 1106-1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen, E. D., Sarraf, P., Troy, A. E., Bradwin, G., Moore, K., Milstone, D. S., Spiegelman, B. M., and Mortensen, R. M. (1999) Mol. Cell 4 611-617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamori, Y., Masugi, J., Nishino, N., and Kasuga, M. (2002) Diabetes 51 2045-2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He, W., Barak, Y., Hevener, A., Olson, P., Liao, D., Le, J., Nelson, M., Ong, E., Olefsky, J. M., and Evans, R. M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 15712-15717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kops, G. J., and Burgering, B. M. (1999) J. Mol. Med. 77 656-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barthel, A., Schmoll, D., and Unterman, T. G. (2005) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16 183-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa-Hibi, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Chen, C., and Motoyama, N. (2005) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7 752-760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakae, J., Barr, V., and Accili, D. (2000) EMBO J. 19 989-996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakae, J., Kitamura, T., Kitamura, Y., Biggs, W. H., 3rd, Arden, K. C., and Accili, D. (2003) Dev. Cell 4 119-129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armoni, M., Harel, C., Karni, S., Chen, H., Bar-Yoseph, F., Ver, M. R., Quon, M. J., and Karnieli, E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 19881-19891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowell, P., Otto, T. C., Adi, S., and Lane, M. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 45485-45491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liao, W., Nguyen, M. T., Yoshizaki, T., Favelyukis, S., Patsouris, D., Imamura, T., Verma, I. M., and Olefsky, J. M. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. 293 E219-E227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vollenweider, P., Clodi, M., Martin, S. S., Imamura, T., Kavanaugh, W. M., and Olefsky, J. M. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 1081-1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pascual, G., Fong, A. L., Ogawa, S., Gamliel, A., Li, A. C., Perissi, V., Rose, D. W., Willson, T. M., Rosenfeld, M. G., and Glass, C. K. (2005) Nature 437 759-763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan, W., Yanase, T., Morinaga, H., Mu, Y. M., Nomura, M., Okabe, T., Goto, K., Harada, N., and Nawata, H. (2005) Endocrinology 146 85-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan, W., Yanase, T., Morinaga, H., Okabe, T., Nomura, M., Daitoku, H., Fukamizu, A., Kato, S., Takayanagi, R., and Nawata, H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 7329-7338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patsouris, D., Mandard, S., Voshol, P. J., Escher, P., Tan, N. S., Havekes, L. M., Koenig, W., Marz, W., Tafuri, S., Wahli, W., Muller, M., and Kersten, S. (2004) J. Clin. Investig. 114 94-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakae, J., Cao, Y., Daitoku, H., Fukamizu, A., Ogawa, W., Yano, Y., and Hayashi, Y. (2006) J. Clin. Invest. 116 2473-2483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu, Y., Kawate, H., Ohnaka, K., Nawata, H., and Takayanagi, R. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26 6633-6655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan, W., Yanase, T., Wu, Y., Kawate, H., Saitoh, M., Oba, K., Nomura, M., Okabe, T., Goto, K., Yanagisawa, J., Kato, S., Takayanagi, R., and Nawata, H. (2004) Mol. Endocrinol. 18 127-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sears, D. D., Hsiao, A., Ofrecio, J. M., Chapman, J., He, W., and Olefsky, J. M. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 364 515-521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan, W., Yanase, T., Nomura, M., Okabe, T., Goto, K., Sato, T., Kawano, H., Kato, S., and Nawata, H. (2005) Diabetes 54 1000-1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pfaffl, M. W. (2001) Nucleic Acids Res. 29 e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McInerney, E. M., Rose, D. W., Flynn, S. E., Westin, S., Mullen, T. M., Krones, A., Inostroza, J., Torchia, J., Nolte, R. T., Assa-Munt, N., Milburn, M. V., Glass, C. K., and Rosenfeld, M. G. (1998) Genes Dev. 12 3357-3368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tordjman, J., Chauvet, G., Quette, J., Beale, E. G., Forest, C., and Antoine, B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 18785-18790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eubank, D. W., Duplus, E., Williams, S. C., Forest, C., and Beale, E. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 30561-30569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qu, S., Altomonte, J., Perdomo, G., He, J., Fan, Y., Kamagate, A., Meseck, M., and Dong, H. H. (2006) Endocrinology 147 5641-5652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakae, J., Biggs, W. H., 3rd, Kitamura, T., Cavenee, W. K., Wright, C. V., Arden, K. C., and Accili, D. (2002) Nat. Genet. 32 245-253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosooka, T., Noguchi, T., Kotani, K., Nakamura, T., Sakaue, H., Inoue, H., Ogawa, W., Tobimatsu, K., Takazawa, K., Sakai, M., Matsuki, Y., Hiramatsu, R., Yasuda, T., Lazar, M. A., Yamanashi, Y., and Kasuga, M. (2008) Nat. Med. 14 188-193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu, E., Kim, J. B., Sarraf, P., and Spiegelman, B. M. (1996) Science 274 2100-2103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams, M., Reginato, M. J., Shao, D., Lazar, M. A., and Chatterjee, V. K. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 5128-5132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camp, H. S., and Tafuri, S. R. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 10811-10816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rangwala, S. M., Rhoades, B., Shapiro, J. S., Rich, A. S., Kim, J. K., Shulman, G. I., Kaestner, K. H., and Lazar, M. A. (2003) Dev. Cell 5 657-663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shao, D., Rangwala, S. M., Bailey, S. T., Krakow, S. L., Reginato, M. J., and Lazar, M. A. (1998) Nature 396 377-380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zinman, B., Hoogwerf, B. J., Duran Garcia, S., Milton, D. R., Giaconia, J. M., Kim, D. D., Trautmann, M. E., and Brodows, R. G. (2007) Ann. Intern. Med. 146 477-485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts, V. L., Stewart, J., Issa, M., Lake, B., and Melis, R. (2005) Clin Ther. 27 1535-1547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hevener, A. L., Olefsky, J. M., Reichart, D., Nguyen, M. T., Bandyopadyhay, G., Leung, H. Y., Watt, M. J., Benner, C., Febbraio, M. A., Nguyen, A. K., Folian, B., Subramaniam, S., Gonzalez, F. J., Glass, C. K., and Ricote, M. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117 1658-1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghisletti, S., Huang, W., Ogawa, S., Pascual, G., Lin, M. E., Willson, T. M., Rosenfeld, M. G., and Glass, C. K. (2007) Mol. Cell 25 57-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.