Abstract

Versican is a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan of the extracellular matrix that is involved in a variety of cellular processes. We showed previously that versican, which is overexpressed in cutaneous melanomas as well as in premalignant lesions, contributes to melanoma progression, favoring the detachment of cells and the metastatic dissemination. Here, we investigated the transcriptional regulation of the versican promoter in melanoma cell lines with different levels of biological aggressiveness and stages of differentiation. We show that versican promoter up-regulation accounts for the differential expression levels of mRNA and protein detected in the invasive SK-mel-131 human melanoma cells. The activity of the versican promoter increased 5-fold in these cells in comparison with that measured in non-invasive MeWo melanoma cells. Several transcriptional regulatory elements were identified in the proximal promoter, including AP-1, Sp1, AP-2, and two TCF-4 sites. We show that promoter activation is mediated by the ERK/MAPK and JNK signaling pathways acting on the AP-1 site, suggesting that BRAF mutation present in SK-mel-131 cells impinge upon the up-regulation of the versican gene through signaling elicited by the ERK/MAPK pathway. This is the first time the AP-1 transcription factor family has been shown to be related to the regulation of versican expression. Furthermore, deletion of the TCF-4 binding sites caused a 60% decrease in the promoter activity in SK-mel-131 cells. These results showing that AP-1 and TCF-4 binding sites are the main regulatory regions directing versican production provide new insights into versican promoter regulation during melanoma progression.

Melanoma is a skin cancer with poor prognosis, which fails to respond to currently available therapies; its incidence is rising in Western populations. It arises from melanocytes, the pigmented cells residing in the epidermis. During melanoma progression through the various stages (dysplastic nevus to radial growth pattern, vertical growth pattern and the metastatic tumor), a large number of changes occur in the extracellular microenvironment where tumor cells reside (1, 2). Among these changes, we have previously described the presence of versican in human and canine melanocytic lesions and proposed that versican may be a useful marker of malignancy given that its expression is increased during tumor progression (3, 4). Furthermore, nevi with atypical dysplasia, a lesion that is considered to be a precursor of malignant melanoma, show a degree of versican positivity that correlates with the degree of nuclear atypia (5).

Versican, a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, is one of the main components of the extracellular matrix, which provides a loose and hydrated matrix during key events in development and disease (6). The protein core of versican is divided into three domains: the amino-terminal domain (G1) contains the hyaluronan-binding region, and the carboxyl-terminal domain (G3) consists of a C-type lectin adjacent to two epidermal growth factor-like domains. The middle region of the versican core protein is encoded by two large exons that encode for the GAG attachment regions (subdomains GAG-α and GAG-β). The splicing variants are named V0 (contains all domains), V1 (contains the GAG-β subdomain), V2 (contains GAG-α), and V3 (consisting only of G1 and G3 domains). Several reports have shown that versican plays a role in cell adhesion (3, 7, 8), migration (9, 10), proliferation (8, 11–13), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (14), differentiation (15, 16), invasiveness (17, 18), angiogenesis (19, 20), and apoptosis (21). These collective functions support the contribution of versican to physiological processes as well as to the development of a number of pathologic processes including atherosclerotic vascular diseases (22) and cancer (23). In this context, disruption of the versican gene in the mouse and chick leads to severe cardiac defects and alterations in chondrogenesis (24).

On the other hand, versican expression is higher in a variety of tumors of epithelial origin such as breast (25), prostate (10, 26), endometrial (27), and colon cancers (28) as well as in melanoma (3–5). We have recently shown that versican expression in melanoma cells increases tumor growth in vivo and contributes to their migratory and invasive phenotype (3). We have also demonstrated an inverse relationship between versican expression and the degree of cell differentiation, suggesting a regulation of the gene during melanoma progression (29).

The versican promoter was isolated several years ago, and transcription factor binding sites responsible for its basal expression have been demonstrated to be functional in both mesenchymal and epithelial cells (30). These studies demonstrated that this promoter harbors a typical TATA-box and has several putative regulatory sites for a number of transcription factors such as AP-2 and Sp1. More recently, it has been shown that the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling pathway and the specific binding of human TCF-4 and β-catenin account for the activation of the versican promoter in vascular smooth muscle cells (31) and that β-catenin is required for androgen receptor-mediated transactivation of the promoter in prostate stromal fibroblasts (26). A direct or indirect role of Sonic Hedgehog signaling has been also suggested for transcriptional versican regulation (32).

The purpose of the present work is, first, to analyze whether the transcriptional activity of versican gene accounts for the differential expression of protein and mRNA levels detected in the invasive melanoma cells. Second, we aimed to identify the transcription factors and signaling pathways responsible for versican up-regulation in invasive melanoma cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture—Human melanoma SK-mel-131 and MeWo cell lines were obtained from Dr. A. N. Houghton (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, NY) and Dr. F. X. Real (Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica, Barcelona, Spain), respectively. These cell lines were originally derived from a human melanoma (33). Cells were grown in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen). All cultures were tested for mycoplasma before use.

Genotype Analysis of Human Melanoma Cell Lines—Genomic DNA was obtained from a 2-ml culture of cell lines using the Gentra Puregene kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN), following the manufacturer's instructions. For BRAF and NRAS, primers were designed to amplify the exon at which most common mutations are detected: BRAF exon 11, forward primer, TTTCTTTTTCTGTTTGGCTTG, and reverse primer, ACTTGTCACAATGTCACCACA; BRAF exon 15, forward primer, TGCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAA, and reverse primer, TCAGTGGAAAAATAGCCTCA; NRAS exon 1, forward primer, CGCCAATTAACCCTGATTAC, and reverse primer, AGAGACAGGATCAGGTCAGC; NRAS exon 2, forward primer, CCCCTTACCCTCCACACC, and reverse primer, AACACAAAGATCATCCTTTCAGA. All PCRs were carried out using PCR Master Mix from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR conditions were: initial denaturing step for 5 min at 95 °C and 35 cycles for 1 min at 95 °C, 1 min at 57 °C, and 1 min at 72 °C followed by a final extension for 10 min at 72 °C, maintaining at 4 °C until single strand conformation analysis or sequencing studies were carried out.

Mutational screening for BRAF and NRAS loci was performed by single strand conformation analysis. BRAF exon 15 was directly sequenced. SSCP analysis: 3 μl of denatured PCR product was combined with loading buffer and loaded into GeneGel Excel 12.5 acrylamide gels (Amersham Biosciences) and run at 15 °C for 2 h. Samples with abnormally migrating products were sequenced as follows: PCR products were purified using GFX™ PCR DNA and gel band purification kit (Amersham Biosciences) and sequenced automatically using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and an ABI3100 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems). The mutations described in this study were designated following the recommendations of den Dunnen and Antonarakis (34). Characterization of other genotypes can be found in the supplemental material.

Isolation and Generation of Versican Promoter Reporter—A 620-bp fragment corresponding to the wild-type versican promoter was obtained by PCR from genomic DNA prepared from the undifferentiated human melanoma cell line SK-mel-1.36-1-5, a clone derived from the SK-mel-131 cell line (33). Specific oligonucleotides corresponding to the -618 (pVS-Fw 5′-ACTTTCCCTCTAGGTCCCCGA-3′) to +2 (pVS-Rv 5′-CGGTACAGTGATATAATGATGATGGGT-3′) region of the promoter sequence described by Naso et al. (30) (GenBank™ accession number U15963) were used. The amplified sequence was cloned into pCR2.1 vector using the TA cloning system (Invitrogen). The insert was recloned into the KpnI/XhoI site of pGL2-basic vector (Promega) and fused to a luciferase reporter gene; this construction was sequenced and named pGL2-pVS-626.

Generation of Promoter Mutant and Deletion Constructs—5′-Deletion constructs were generated by PCR from the pGL2-pVS-626 construct and cloned into pGL2-basic vector with the followings primers: Fw-pVS-467 (5′-GCTCCCGAGAAGAAGTGATCG-3′); Fw-pVS-361 (5′-GAAATGGGGGTGGGGAAGGAG-3′); Fw-pVS-256 (5′-GTACTTCTTGTCAGGAAGAAACGCC-3′); Fw-pVS-178 (5′-GAGCTGCCTTTCCGCCCCT-3′); Fw-pVS-120 (5′-AAGCTGCGGAGCGCTTTTG-3′), in all cases the reverse primer was pVS-Rv (5′CGGTACAGTGATATAATGATGATGGGT-3′). The PCR reactions were performed with Expand™ HiFi polymerase (Roche Diagnostics) and the specific primers for the versican promoter as follows: 30 cycles, with each cycle including 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 50 °C, and 1 min 30 s at 72 °C. The final extension step at 72 °C was carried out for 5 min. PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1 vector using the TA cloning system (Invitrogen) and then into the appropriate site of the pGL2-basic vector directing the luciferase reporter expression. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce point mutations into the AP-1 putative binding site in the versican promoter at position -36. The PCR reactions for mutagenesis were performed on 10 ng of wild-type pGL2-pVS-626 and wild-type pGL2-pVS-120 as template using Expand™ HiFi polymerase (Roche Diagnostics). The PCR was performed as follows: 18 cycles of 98 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 1 min, and 68 °C for 13 min; the final elongation step was carried out at 68 °C for 20 min. After PCR, the parental supercoiled double-stranded DNA was digested with DpnI (Roche Diagnostics) at 37 °C for 2 h, and competent Escherichia coli cells (TOP-F10) were transformed by thermal shock. Mutant construction at nt -35 and -33 was generated by using the primers Fw-pVS-120AP1mut (5′-CGGCTCTaAgGGTACAGTGATATAATGATG-3′) and Rv-pVS-120AP1mut (5′-CTGTACCcTtAGAGCCGAGGAGGAGACTCA-3′ (mutated nucleotide in low case)). All promoter constructs and the novel site mutations construct were confirmed by sequencing.

Expression and Reporter Vectors—A wild-type TCF-4 expression construct (pcDNA3-TCF4-His-HA), a dominant positive TCF-4 (pcDNA3-TCF4VP16), a native β-catenin (pcDNA3-β-catenin), and a dominant positive form of β-catenin (pcDNA3-β-catenin S37Y) were a kind gift from Dr. A. García de Herreros (Institut Municipal d'InvestigacióMèdica, Barcelona, Spain) and Dr. M. Duñach (Departament of Bioquímica i Biologia Molecular, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain). The TOP-Flash, FOP-Flash, and AP-1 reporter constructs were a gift from Dr. J. Baulida (Institut Municipal d'InvestigacióMèdica, Barcelona, Spain).

Transient Transfections and Promoter Activity Assays—Subconfluent cell cultures from starved human melanoma SK-mel-131 or MeWo cells were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine PLUS reagent (Invitrogen) in 6-well plates using 1 μg of plasmid DNA and 100 ng of the pRL-TK plasmid as a control (Promega). In cotransfection experiments, 1 μg of a second plasmid was added. Cells were transfected in fetal calf serum-free medium for 5 h and switched to 10% fetal calf serum medium for 24 h. Whenever an inhibitor such as PD98059 (40 μm) (Sigma-Aldrich), SP600125 (50 μm), mithramycin (100 μm), SB203580 (20 μm) or wortmannin (210 nm) (all from Calbiochem) was used, it was added to the 10% fetal calf serum medium 6 h before the end of the incubation. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (Promega), and luciferase and Renilla activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Immunoblotting—For versican detection, conditioned media were obtained from subconfluent cultures after starvation for 16 h, and a mixture of protease inhibitors was added (10 mm EDTA, 5 mm benzamidine, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). To make sure that every conditioned media used came from the same number of cells, duplicate wells were seeded and cells were counted in a Neubauer chamber. Media were digested with chondroitinase ABC (Sigma-Aldrich; (50 milliunits/ml in 33 mm sodium acetate, 33 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) at 37 °C for 16 h. For ERK,5 P-ERK, P-JNK, and c-Jun immunoblotting, cells were cultured with or without 40 μm PD98059 or 50 μm SP600125. Proteins were extracted by adding lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm sodium β-glycerolphosphate, 50 mm NaF, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The amount of protein was determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). The samples were resolved in a 6 or 8% polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions (SDS-PAGE). Separated proteins were transferred onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) followed by blocking for 1 h at room temperature in a solution with 5% fat-free milk in 0.05 m Tris buffer, 0.15 m NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20 (TBS-T). Membranes were either blotted with polyclonal antibody directed against versican generated in our laboratory (1:100) (3), anti-P-ERK 42/44 (1:2000), anti-ERK 42/44 (1:2000), anti P-JNK (1:1000), and anti-c-Jun (1:1000) (antibodies against ERK and P-ERK were from Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA; antibodies against P-JNK and c-Jun were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), in 5% fat-free milk in TBS-T for 16 h at 4 °C. Membranes were washed and further probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated immunoglobulin for 1 h at room temperature (anti-rabbit, 1:2000; anti-goat, 1:10000). Antibody binding was visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Biosciences).

RT-PCR of Versican—Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) from subconfluent cultures. For the RT step, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed in a 20-μl reaction volume using Expand reverse transcriptase (Roche Applied Science) as described in the protocol provided by the supplier. 10 μl of the reaction mix was subsequently used for PCR. The primers used for amplification of the specific splice variants of versican were those described previously (29). Thirty cycles were performed, each cycle including 1 min at 94 °C, 1 min at 55 °C for V0 and V1 or 53 °C for V2 and V3 isoforms, and 1 min at 72 °C for all of them. The final extension step at 72 °C was carried out for 10 min. The concentration of MgCl2 was 2 mm for V1 and V2 and 2.5 mm for V0 and V3. The sizes of the amplification products were 351 bp (V0), 386 bp (V1), 373 bp (V2), and 342 bp (V3). RT-PCR amplification of a 960-bp fragment of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as a control as described previously by Paulus et al. (35). Amplification products were resolved on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. All of the amplification fragments were isolated and digested with an appropriate restriction enzyme in order to confirm their identity.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)—To generate double-stranded DNA, probe oligonucleotides were annealed to equimolar amounts in buffer M (Roche Diagnostics) by heating at 95 °C for 5 min and slowly cooling to room temperature. 100 ng of probes were 5′-end-[γ-32P]deoxyadenine triphosphate-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and purified with Microspin S-200 HR columns (Amersham Biosciences) prior to use in electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Nuclear extracts were prepared by the method described by Schreiber et al. (36). Final nuclear protein preparations were collected in cold buffer C (400 mm NaCl, 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). For band shift experiments, 100,000 cpm of labeled oligoduplex probes were added to 10 μg of nuclear extracts in DNA binding buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 100 mm KCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.4 mm ZnSO4, 40 μm ZnCl2). To prevent nonspecific binding of nuclear proteins, 1 μg of poly(dI-dC) was added, and the binding reaction was incubated at room temperature for 20 min prior to electrophoresis. Nonlabeled oligonucleotides were added to competition experiments at a 50-fold concentration.

For supershift experiments, 2 μg of the following antibodies were used: anti-c-Jun, anti-TCF-4, anti-AP-2α (from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-β-catenin, and anti-Sp1 (from BD Biosciences). The antibodies were added to the binding reaction and incubated for 20 min at room temperature prior to electrophoresis. Normal IgG was used as control reaction, and antibody negative reactions were supplemented with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline. Protein-DNA complexes were separated from unbound DNA using a 5% (w/v) polyacrylamide in 0.5× Tris borate-EDTA nondenaturing gel run at constant voltage at room temperature. Gels were dried and the complexes visualized by autoradiography. The oligonucleotide sequences used for EMSAs are indicated in the figure legends (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

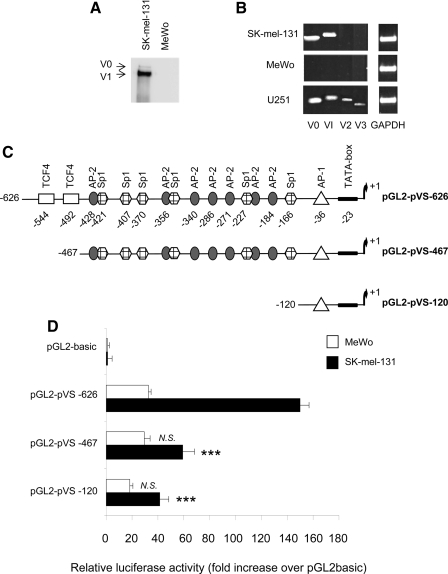

FIGURE 1.

Versican expression and activity of the versican promoter in SK-mel-131 and MeWo human melanoma cell lines. A, invasive human SK-mel-131 melanoma cells express versican isoforms V0 and V1, whereas non-invasive MeWo cells do not. Immunoblotting of conditioned media from subconfluent cultures from human melanoma cell lines SK-mel-131 (early differentiated) and MeWo (late differentiated); 24-h conditioned media treated with chondroitinase ABC were resolved in an 8% SDS-PAGE and blotted with a polyclonal antibody raised in our laboratory against versican (1:100). Arrows indicate the V0 and V1 versican isoforms. B, detection of versican isoforms by RT-PCR in both human melanoma cell lines. 1 μg of total RNA was used for the initial RT reaction. The sizes of the amplification products were 351 bp (V0), 386 bp (V1), 373 bp (V2), and 342 bp (V3). U251 human astrocytoma cells were used as a positive control (35). C, schematic maps of the versican promoter and deletion constructs, showing the putative regulatory elements. D, activity of the pGL2-pVS-626, pGL2-pVS-467, and PGL2-pVS-120 deletion constructs in SK-mel-131 and MeWo human melanoma cell lines. Transfection of cell lines was carried out with 1 μg of the indicated constructs of the human versican promoter and 100 ng of pRL-TK vector. The empty vector, pGL2-basic, was used as a control. Promoter activity is expressed as relative activity over the empty pGL2-basic construct. One representative experiment of six performed is shown. ***, p < 0.001; N.S., not significant (promoter activity versus pGL2-pVS-626 in each cell line).

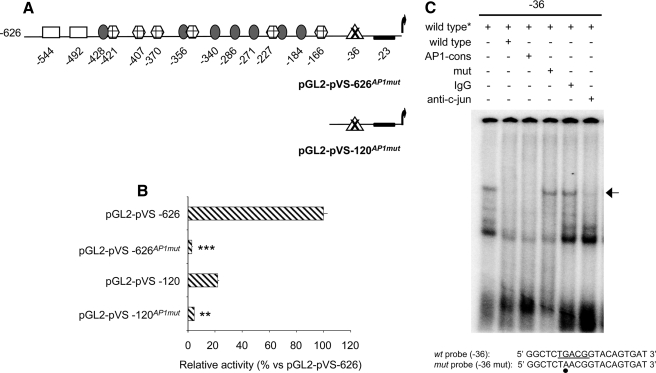

FIGURE 2.

The AP-1 binding site of the versican promoter has an essential role in SK-mel-131 melanoma cells. A, schematic representation of the versican promoter deletion constructs bearing specific mutations in the AP-1 box (pGL2-pVS-626AP1mut and pGL2-pVS-120AP1mut). B, mutation at the AP-1 site located at position -36 completely abolishes versican promoter activity. SK-mel-131 melanoma cells were transfected with pGL2-pVS-626AP1mut and pGL2-pVS-120AP1mut constructs. Cell lysates were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured. The luciferase activity numbers are expressed as relative activity versus the pGL2-pVS-626 construct. One representative experiment of six performed is shown. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (AP1mut promoter activity versus their respective controls). C, c-Jun is involved in the activation of the versican promoter at the AP-1 site. Nuclear extracts from SK-mel-131 melanoma cells were analyzed in EMSAs using the 32P-labeled AP-1 wild-type probe of the versican promoter containing the putative AP-1 binding site at nt -36. The complete sequence of the AP-1 probe is shown at the bottom of the figure, with the position of the AP-1 site underlined and the mutated nucleotide marked with a black-filled circle. Nuclear extracts were incubated with the 32P probe in the presence of 500-fold molar excess of wild-type, mutant, or AP-1 consensus cold oligonucleotides or in the presence of control rabbit IgG or an antibody against c-Jun.

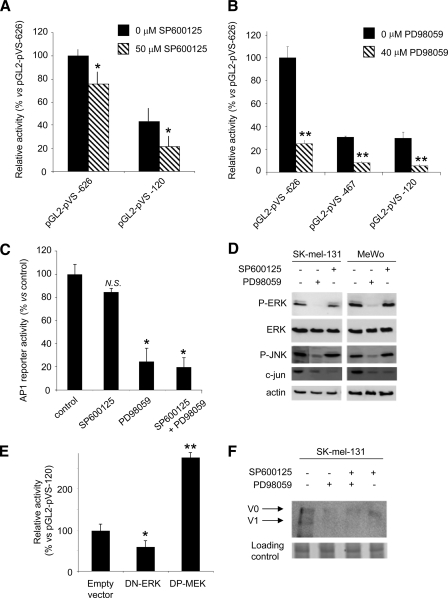

FIGURE 3.

The ERK and JNK pathways are involved in the regulation of the versican promoter. A, the JNK inhibitor SP600125 partly inhibits the activity of the whole versican promoter and the promoter construct bearing the AP-1 box. SK-mel-131 melanoma cells were transfected with the versican promoter pGL2-pVS-626 and the deletion construct pGL2-pVS-120 and treated or not with the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (50 μm) for 6 h. Cells were lysed, and the luciferase activity was measured and expressed as relative activity versus the pGL2-pVS-626 construct. One representative experiment of six performed is shown. *, p < 0.05 (promoter activity versus nontreated cells). B, the ERK inhibitor PD98059 inhibits the activity of the whole versican promoter and the promoter deletion constructs. SK-mel-131 melanoma cells were transfected with the versican promoter deletion constructs pGL2-pVS-626, pGL2-pVS-467, and pGL2-pVS-120 and treated or not with the ERK inhibitor PD98059 (40 μm) for 6 h. The luciferase activity numbers are expressed in relative activity versus the pGL2-pVS-626 construct. One representative experiment of four performed is shown. **, p < 0.01 (promoter activity versus nontreated cells). C, promoter activity in SK-mel-131 melanoma cells transfected with an AP1-reporter and treated with 40 μm PD098059 and/or 50 μm SP600125 for 6 h. The luciferase activity numbers are expressed as relative activity versus the pGL2 empty vector. One representative experiment of three is shown. *, p < 0.05 (promoter activity versus nontreated cells). N.S., not significant. D, the ERK inhibitor PD98059 inhibits ERK and JNK phosphorylation in human melanoma cells. Immunoblotting of cell extracts from subconfluent cultures from SK-mel-131 and MeWo human melanoma cell lines treated with 40 μm PD98059 or 50 μm SP600125 and blotted with antibodies against ERK and P-ERK, P-JNK, and c-Jun is shown. E, overexpression of DN-ERK and DP-MEK in SK-mel-131 melanoma cells results in a decrease and increase, respectively, in versican promoter deletion construct pGL2-pVS-120 activity. SK-mel-131 melanoma cells were cotransfected with versican promoter deletion construct pGL2-pVS-120 and DN-ERK or DP-MEK. Cell lysates were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (versus empty vector). F, immunoblotting of conditioned media from subconfluent cultures from SK-mel-131 human melanoma cell lines treated with 40 μm PD098059 and/or 50 μm SP600125 for 12 h. The conditioned media were treated with chondroitinase ABC, resolved in an 8% SDS-PAGE, and blotted with a polyclonal antibody raised in our laboratory against versican (1:100). Arrows indicate the V0 and V1 versican isoforms. The gel was stained with 0.1% Coomassie Blue; a representative band is shown as a loading control (lower panel).

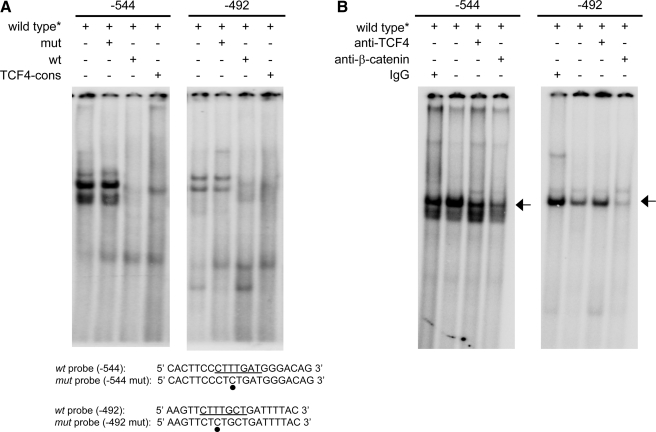

FIGURE 4.

Determination of the role of the TCF-4 binding sites in the regulation of the versican promoter. Nuclear extracts from SK-mel-131 melanoma cells were analyzed in band shift assays using the 32P-labeled TCF-4 wild-type probes of the versican promoter containing the putative TCF-4 binding sites at nt -544 and -492. The complete sequences of the TCF-4 probes are shown at the bottom of the figure, with the position of the TCF-4 sites underlined and the mutated nucleotide marked with a black-filled circle. A, nuclear extracts were incubated with the 32P probe in the presence of 500-fold molar excess of wild-type, mutant, or TCF-4 consensus cold oligonucleotides. B, nuclear extracts were incubated with the 32P probe in the presence of control rabbit IgG or an antibody against TCF-4 or β-catenin.

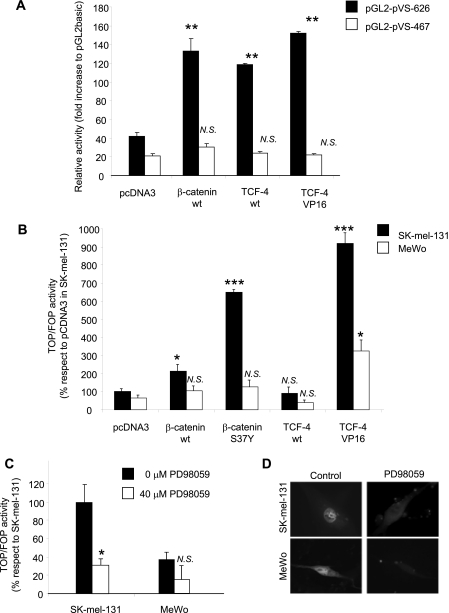

FIGURE 5.

The β-catenin/TCF-4 pathway plays a role in the regulation of the versican promoter. A, components of the β-catenin/TCF-4 pathway induce the activity of the whole versican promoter, but they have no effect on the construct lacking the two TCF-4 boxes. SK-mel-131 cells were cotransfected with the pGL2-pVS-626 construct or the pGL2-pVS-467 construct (lacking the two TCF-4 boxes) together with wild-type or mutated forms of components of the Wnt pathway. Cell lysates were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured. Results are expressed as relative activity versus the pGL2-basic. A representative experiment of four performed is shown. **, p < 0.01; N.S., not significant (promoter activity versus pcDNA3 for each construct). B, SK-mel-131 cells have higher activity in the Wnt pathway than MeWo cells according to the activity of the TOP/FOP reporter. SK-mel-131 and MeWo cells were cotransfected with TOP-Flash/FOP-Flash reporter construct together with the wild-type or mutated components of the Wnt pathway. A representative experiment of four performed is shown. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 (TOP/FOP activity versus pcDNA3 in each cell line). C, the ERK inhibitor PD98059 partially inhibits TOP/FOP reporter activity in SK-mel-131 melanoma cells. SK-mel-131 and MeWo cells were transfected with the TOP-Flash/FOP-Flash reporter construct and treated for 1.5 h with 40 μm PD089050. A representative experiment of three performed is shown. *, p < 0.05 (TOP/FOP activity versus control SK-mel-131 cells). D, β-catenin is localized outside the cell nucleus after PD89059 treatment. SK-mel-131 and MeWo cells were transfected with a β-catenin-GFP construct and treated for 1.5 h with 40 μm PD089050. Cells were observed using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse E800).

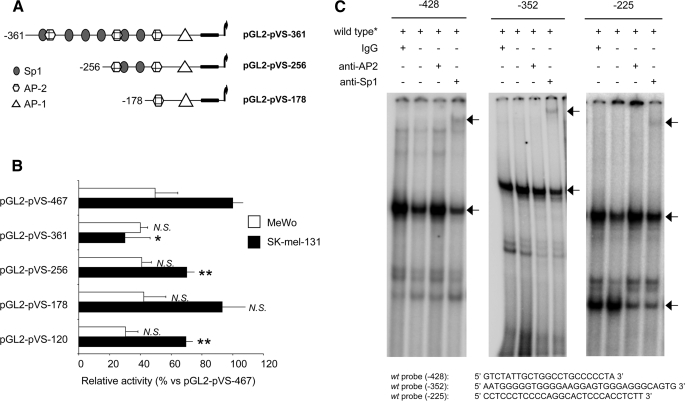

FIGURE 6.

The central region of the versican promoter containing the Sp1 and AP-2 sites has a role in the fine-tuned regulation of the promoter. A, schematic representation of the versican promoter deletion constructs targeting the Sp1 and AP-2 boxes. B, transfection of melanoma cell lines was carried out with 1 μg of versican promoter constructs and 100 ng of pRL-TK vector; the empty vector pGL2-basic was used as a control. The activity numbers are expressed as relative activity versus the pGL2-pVS-467 construct. A representative experiment of six performed is shown. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; N.S. not significant (promoter activity versus pcDNA3 in each cell line). C, the EMSA showed a specific DNA-protein complex that decreased in intensity when an antibody specific for Sp1 to the reaction was added, whereas a supershift band appears at the high molecular weight range of the gel (arrows).

β-Catenin-GFP Transfection—SK-mel-131 and MeWo cells were seeded on coverslips, incubated overnight, and transiently transfected with 1 μg of a GFP-β-catenin construct into the pEGFP plasmid (BD Biosciences-Clontech). After a 24-h incubation, cells were treated with 40 μm PD98059 for 1.5 h, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, 2% saccharose. Cells were rinsed further and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and coverslips were mounted on glass slides.

Statistical Analysis—Statistical significance was determined using the unpaired Student's t test. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Versican Expression Is Concomitant with the BRAF (V600E) Mutation in SK-mel-131 Human Melanoma Cell Line—In agreement with our previous results, the undifferentiated and invasive SK-mel-131 cell line expresses versican isoforms V0 and V1 at protein and mRNA levels, whereas the differentiated and non-invasive MeWo cells do not (Fig. 1, A and B). We characterized the genetic context of these and other cell lines, looking for the most common mutations observed in human melanoma. We found that SK-mel-131 cell line presents an activating mutation in the BRAF gene (V600E), which confers the constitutive activation of the MEK/ERK pathway, whereas MeWo cells do not (Table 1). All melanoma cell lines tested by us or other authors showed a positive correlation between the production of versican and the presence of mutations in BRAF or NRAS genes. Both cell lines harbor silent mutations in the APC gene and mutations in the CDKN2A locus (supplemental data).

TABLE 1.

Genetic context in the melanoma cell lines Genomic DNA was obtained from cell lines as described under “Experimental Procedures.” For BRAF and NRAS, primers were designed to amplify the exon in which the most common mutations are detected. Mutational screening for BRAF and NRAS loci was performed by single strand conformation analysis.

| Cell line | Stage of differentiation | BRAF | NRAS | Versican productiona |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SK-mel-131 | Early | V600E | Wild typeb | Yes |

| SK-mel-37 | Early | V600E | Wild typeb | Yes |

| SK-mel-3.44 | Early | V600E | Wild typeb | Yes |

| Rider | Early | Wild type | Q61Lb | Yes |

| MeWo | Late | Wild type | Wild typeb | No |

| DX2 | Late | Wild type | Wild typeb | No |

| SK-mel-23 | Late | Wild type | Wild typec | No |

Versican Promoter Activity Is Higher in Invasive SK-mel-131 Human Melanoma Cells—To investigate whether the versican promoter is differentially regulated in invasive and non-invasive melanoma cells, we cloned a 628-bp fragment of genomic DNA from SK-mel-1.36-1-5 human melanoma cells (-626 to +2 relative to the transcriptional initiation site) into a pGL2-control vector directing the expression of the luciferase gene. Sequence analysis indicated almost 100% homology with the sequence reported previously (30). Differences were observed in just six nucleotides: two changes in position -279 (T > G) and -357 (A > G) and four nucleotide additions (an addition ofGat -159, -309, and -406 and an addition of C at position -270). Only the change at -357 created a new Sp1 binding site. In silico analysis revealed several putative transcription factor DNA-binding elements in the 5′-region encompassing nucleotides at position -626 to +2 according to the transcription initiation site (Fig. 1C). The proximal promoter contained two binding sites for TCF-4 (nt -544 and -492), a GC-rich region containing several Sp1 and AP-2 binding sites, and finally, a proximal region (nt -120 to +2) with an AP-1 binding site (nt -36) and a TATA-box. The activity of the different constructs encompassing the putative binding elements was measured in the invasive versican-producing SK-mel-131 cells and the non-invasive MeWo cells, which do not produce versican. As shown in Fig. 1D, the transcriptional activity of the pGL2-pVS-626 construct in SK-mel-131 cells is five times higher than in the MeWo cells, indicating that transcriptional regulation accounts for the differential expression levels observed between both cell lines. Importantly, we observed, only in SK-mel-131 cells, that the deletion of the two TCF-4 boxes caused a 60% decrease in promoter activity and that the construct pGL2-pVS-120 containing the AP-1 binding site and the TATA-box retained 30% of the promoter total activity. In contrast, the activity of the different deletion constructs was not modified in MeWo cells.

AP-1 Plays an Important Role in the Regulation of Versican Promoter Activity—To analyze the contribution of the proximal AP-1 binding site (at nt -36) to the versican promoter activity in SK-mel-131 cells, we mutated this site in the whole and the short promoter constructs (pGL2-pVS-626AP1mut and pGL2-pVS-120AP1mut, respectively, see “Experimental Procedures”) (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, the promoter activity in SK-mel-131 cells was completely abolished by the mutation. It is important to notice that the point mutation of this site abolishes the action of all the other binding sites, indicating the importance of the AP-1 binding site to the activity of this promoter.

To assess the formation of AP-1 complexes at this site, EMSA studies were performed using the putative AP-1 site (TGACG) of the promoter. As shown in Fig. 2C (lane 1), a specific DNA-protein complex was detected corresponding to nuclear extracts of SK-mel-131 cells incubated in the presence of the labeled probe corresponding to the AP-1 site. The specificity of the complex was demonstrated by competition with an excess (×500) of the cold wild-type oligonucleotide or an oligonucleotide with the consensus sequence for AP-1 but was not competed by a similar excess of the cold mutant AP-1 oligonucleotide. The intensity of this complex was dramatically reduced after the incubation with an antibody against c-Jun but not with the unspecific IgG (Fig. 2C). In contrast, the incubation with an antibody against c-Fos did not affect the complex formation (data not shown). These results suggest that c-Jun may be involved in the activation of the versican promoter at the AP-1 site.

Signaling through the JNK and ERK Pathways Is Essential for Transactivation of the Versican Promoter in Melanoma Cells—The phosphorylation of c-Jun by the JNK kinase activates this transcription factor to act on its target promoters (37, 38). Therefore, we tested the effect of the JNK inhibitor SP600125 on SK-mel-131 cells transfected with either the long pGL2-pVS-626 or the short pGL2-pVS-120 versican promoter constructs. As shown in Fig. 3A, the relative activity of the short promoter pGL2-pVS-120 diminishes by 50% in the presence of SP600125, whereas the activity of the long construct pGL2-pVS-626 decreases up to 20%. Thus, versican promoter activity is regulated through c-Jun, and its activation is, at least in part, mediated by JNK.

When we used the ERK inhibitor PD98059, we observed a strong inhibitory effect on versican promoter activity in SK-mel-131 cells. This effect was detected when using the large construct or the deletion constructs pGL2-pVS-467 and pGL2-pVS-120, indicating that the ERK pathway is essential for promoter activity (Fig. 3B). To test whether the MAPK might influence the binding of transcription factors from melanoma cells to the AP-1 sequences, we transfected the SK-mel-131 cell line with an AP-1 reporter construct (see “Experimental Procedures”). When the JNK inhibitor SP600125 was added to the transfected cells, only 10% of the activity was lost; however, when we added the ERK inhibitor PD98059, we lost almost 80% of the AP-1 reporter activity, similar to the inhibition produced by adding both inhibitors at the same time (Fig. 3C). Because c-Jun is involved in the regulation of the versican promoter, we tested how the ERK inhibitor acts on c-Jun and the phosphorylation of ERK. As shown in Fig. 3D, treatment with PD98059 provoked a very important reduction in P-ERK, P-JNK, and levels of c-Jun, indicating that the pathway mainly involved in the regulation of c-Jun is the ERK pathway. Our results are in agreement with the recently described relationship between the ERK pathway and JNK activity in melanoma (39).

To further investigate the contribution of MAPK signaling to the regulation of the versican promoter, we cotransfected the short construct pGL2-pVS-120 containing the AP-1 site with either a dominant positive form of MEK (DP-MEK) or a dominant negative of ERK (DN-ERK). As expected, overexpression of DP-MEK significantly increased the activity of the pGL2-pVS-120 versican construct in the SK-mel-131 cell line whereas DN-ERK induced a decrease in the activity of the short construct (Fig. 3E). All of these results show the relevance of the ERK pathway in regulating the versican promoter.

To investigate the physiological significance of versican regulation through the MAPK pathways, we performed a Western blot of versican in SK-mel-131 cells treated with the inhibitors PD98059 and SP600125. As shown in Fig. 3F, a significant decrease in versican production is seen after PD98059 and SP600125 treatment, indicating that transcriptional regulation does result in changes at the protein level.

Other signaling pathways did not seem to have a regulatory role, as the p38 inhibitor (SB203580), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor (wortmannin), and Sp1 inhibitor (mithramycin) did not have any significant effect on versican promoter activity (supplemental data).

TCF-4 Binding Sites in the Versican Promoter Are Active in Melanoma Cells—Regulation of versican expression through TCF-4 sites has been described in other cell systems. To analyze the importance of the two TCF-4 binding sites (nt -544 and -492) in melanoma, we investigated the formation of protein-DNA complexes at these sites by EMSA. As shown in Fig. 4A, the nuclear extracts from SK-mel-131 did bind to both TCF-4 sites, and the binding was effectively competed by an excess (×500) of the cold wild-type oligonucleotide or the consensus sequence for TCF-4 but not by a similar excess of the cold mutant oligonucleotide. Furthermore, incubation with an antibody against β-catenin clearly decreased the intensity of the complex formed with the oligonucleotide encompassing the putative sites at -544 nt as well as at -492 nt, indicating that this protein was involved in binding to the TCF-4 sequences in SK-mel-131 cells (Fig. 4B). In MeWo melanoma cells, no binding at -544 was observed in EMSA assays (data not shown).

To assess the regulatory role of the TCF-4 binding sites, we cotransfected the pGL2-pVS-626 construct or the pGL2-pVS-467 construct (lacking the two TCF-4 boxes) together with expression vectors encoding components of the Wnt pathway: β-catenin (pcDNA3-β-catenin, wild type) and TCF-4 (pcDNA3-TCF-4, wild type). Alternatively, an activated form of TCF-4 (VP16-TCF4) was used. As shown in Fig. 5A, overexpression of β-catenin, TCF-4wt, or the activated form of the TCF-4 clearly increased the activity of the versican promoter (pGL2-pVS-626 construct) in SK-mel-131 cells, whereas it did not have any effect on the truncated construct pGL2-pVS-467.

Because MeWo cells do not produce versican, we also wanted to assess the contribution of the Wnt pathway in this cell line as compared with the versican-producing SK-mel-131 cells. For this purpose, we cotransfected the plasmids expressing the wild-type or mutated components of the Wnt pathway together with a TOP-Flash/FOP-Flash reporter construct in both cell lines. As observed in Fig. 5B, the activity of the β-catenin-sensitive promoter TOP-Flash in MeWo cells is lower than in SK-mel-131 cells, and the S37Y constitutively active β-catenin mutant failed to rescue the TOP-Flash activity; this suggests that this pathway is not functional in the differentiated MeWo cell line, as would be expected given their lack of versican production. The levels of β-catenin did not significantly differ between SK-mel-131 and MeWo cells as measured by Western blot in nuclear extracts or immunocytochemistry (data not shown).

Because there may be cross-talk between the ERK and the E-cadherin/β-catenin pathways (40, 41), we investigated whether ERK might modulate the β-catenin-mediated activation of the TCF-4 sites. Treatment with PD98059 of SK-mel-131 cells transfected with the TOP-Flash/FOP-Flash reporter construct significantly decreased the activity of the promoter in SK-mel-131 cells, whereas the effect on MeWo cells was much less (Fig. 5C). As activation of the TOP/FOP reporter may be mediated by a change in the intracellular location of β-catenin, we sought to analyze by immunocytochemistry whether treatment of melanoma cells with the ERK inhibitor PD98059 would alter the location of β-catenin in the cell. Using a GFP-β-catenin construct, we localized β-catenin mainly in the nucleus in control SK-mel-131 cells as well as in MeWo cells. After treatment with PD98059, β-catenin was also found in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5D).

Role of Sp1 and AP-2 Sites in the Regulation of Versican Promoter Activity—The in silico analysis of the central region of the promoter showed a large number of AP-2 and Sp1 sites. To analyze the role of these sites in the regulation of versican promoter, we generated a new set of deletion constructs (Fig. 6A). When these constructs were transfected in SK-mel-131 cells, a partial loss of promoter activity was observed for all constructs except pGL2-pVS-178 (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, EMSA indicated that Sp1 factors are indeed able to bind to the Sp1 sites in the promoter (Fig. 6C).

DISCUSSION

Malignant melanoma is characterized by the harboring of superactive kinases of the MAPK family. Mutations in BRAF or NRAS genes, found in >70% of intermittently sun-exposed melanomas, cause superactivation of ERK (42, 43). Mutations in BRAF and NRAS, which are both upstream of ERK, have been shown to be mutually exclusive in melanoma (44, 45).

In the present study, we used as models the undifferentiated and invasive SK-mel-131 cell line, which harbors a V600E-activating BRAF mutation and produces versican, and differentiated, non-invasive MeWo cells, which are wild type in this locus and do not produce versican. The genetic analysis of a panel of melanoma cell lines indicated that there is indeed a positive correlation between versican production and the existence of activating mutations in BRAF/NRAS (Table 1).

To investigate the regulation of the versican promoter in this tumor type, we cloned a 620-bp fragment and found that the activity of the versican promoter was five times higher in SK-mel-131 cells than in MeWo cells according to the production of the proteoglycan molecule and the ERK pathway activation state. In silico analysis of the versican promoter indicated the presence of AP-1 and TCF-4 binding sites together with AP-2 and Sp1 sites. The presence of TCF-4 boxes had already been shown in smooth muscle cells and epithelial prostate cells (26, 31). The constitutive activation of the ERK pathway in melanoma as a result of BRAF or NRAS mutation leads to the activation of the AP-1 pathway (46). The AP-1 complex comprises the family of proto-oncoproteins Jun and Fos, which can homo- or heterodimerize and bind its cognate consensus sequence (TGA(C/G)TCA) in the regulatory domains of many genes involved in tumor progression and the invasive phenotype (47). In SK-mel-131 cells, the transfection of the short construct pGL2-pVS-120, which contains the AP-1 binding site at -36 and lacks all of the other regulatory sites, retained ∼40% of the activity of the whole promoter, whereas directed mutagenesis of the AP-1 site abolished its activity in the short as well as the long promoter, indicating that the AP-1 site is essential for the versican promoter activity. EMSA indicated that c-Jun is the transcription factor involved in the binding to the AP-1 site in the versican promoter. It has been reported recently that a rewiring mechanism linking ERK with JNK signaling exists in human melanoma. According to this finding, constitutively active ERK increases c-Jun levels in melanoma through a double mechanism: stabilization of c-Jun protein through inactivation of GSK3β and increase of c-jun transcription through a CREB (cAMP-response element-binding protein)-mediated mechanism (39). This mechanism would lead to a feed-forward loop in which c-Jun increases the transcription of RACK-1, an adaptor protein required for activation of JNK, which would increase c-Jun transcriptional activity. Consistent with this hypothesis, treatment of SK-mel-131 cells with the ERK pathway inhibitor PD98059 potently inhibits the activity of the versican promoter and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 reduces by half the activity of the versican promoter. Similar results were obtained when SK-mel-131 cells were transfected with an AP-1 reporter. Furthermore, a dominant positive form of MEK largely increased the pGL2-pVS-120 promoter activity, and the dominant negative form of ERK decreased its activity. Our results suggest that both signaling pathways, involving either JNK or ERK, participate in the regulation of the versican promoter in invasive human melanoma cells. The ERK-JNK feed-forward loop would exist only in SK-mel-131 melanoma cells, whereas in MeWo cells, which do not have a constitutively active ERK pathway and do not express versican, it would not exist. Activation of the ERK pathway also could be the mechanism by which some mitogenic growth factors induce versican production (48).

This is the first time that the AP-1 family has been linked to the regulation of versican expression. It is presently accepted that the AP-1 complex is deeply implicated in regulating the invasive response (47). Several AP-1 target genes are related to tumor invasion, as various MMP family members (49) or the extracellular matrix-associated protein, osteonectin/SPARC (50). Versican may be another one of these proinvasive molecules regulated by AP-1 that contributes to the invasive properties of the cell with its antiadhesive and promigratory effect (3, 11, 20, 21).

The role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in epithelial cancer development has been well established (51, 52). Although melanocytes do not have an epithelial origin, recent work suggests a role for the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in melanoma development (53–55). Thus it has been described that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway controls cell fate determination in the melanocyte lineage (56, 57). β-Catenin is found in about 30% of human melanoma cell nuclei, and ∼10% of the tumors bear mutations in the APC gene, indicating a potentially specific role for this signaling pathway in this aggressive type of cancer (55). The versican gene was identified as a target gene of Wnt signaling using microarray technology to analyze human embryonic carcinoma cells stimulated with active Wnt protein (58). In human melanoma cells, versican expression is also up-regulated by the β-catenin/TCF4 pathway, because when the two TCF-4 boxes at the 5′-end of the promoter were deleted, ∼50% of the promoter activity was lost. Furthermore, β-catenin is present in transcriptional complexes with affinity to the TCF binding sites, and the activity of the promoter is up-regulated when SK-mel-131 cells are cotransfected with components of the pathway (β-catenin or TCF-4). Most interestingly, we have shown a positive cross-talk between the ERK and β-catenin pathways in these cells. Indeed, in the most aggressive SK-mel-131 cells, the activation of the promoter correlates with versican expression, strong binding of TCF-4 at nt -544, and mutation at BRAF.

Our findings support the biological function of Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation in a non-epithelial tumor, such as melanoma, and suggest that each tumor type may get specific advantages out of their own genetic background. Prostate cancer may be another example, where versican is induced by androgens through the androgen receptor with the participation of β-catenin (26). Furthermore, versican may be envisaged as a general target gene for Wnt in many cancers, together with other up-regulated genes involved in neoplasia, such as MMP-7, fibronectin, VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), cyclin D, and c-myc (58, 59), thus providing a coordinated mechanism by which tumor cells deregulate proliferation and invasion abilities. Deregulation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and, consequently, of versican expression may also be involved in the pathogenesis of other diseases such as atherosclerosis, because its promoter has also been shown to be regulated through this pathway in rat vascular smooth muscle cells (31).

Finally, although AP-1 and TCF-4 binding sites seem to be the main regulatory regions of the versican promoter, a GC-rich region bearing many putative Sp1 and AP-2 binding sites exists in the central region of the promoter. Although our results show that only 10% of the promoter activity resides in this region, this is a functional region because Sp1 binds to the promoter, as shown in EMSAs. These results suggest that Sp1 may have a fine regulatory role, similar to that suggested for Sp1 in the regulation of the MMP-9 promoter by the MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways (60). A similar situation may be conceivable for AP-2, which also has been linked to melanoma progression (61). It is also noteworthy that the PAR-1 (protease-activated receptor-1) promoter is regulated through the ratio of Sp1 to AP-2 in melanoma cells (62).

In conclusion, the present study indicates that constitutive activation of the ERK and JNK pathways, together with increased β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling, leads to a deregulated expression of versican in human malignant melanoma. Differences in versican production between invasive and non-invasive melanoma cells are thus related to the constitutive activation of the ERK pathway and the activity of the Wnt pathway. The production of versican contributes to the formation of hyaluronan-versican complexes, allowing the remodeling of the extracellular matrix, which would then become more permissible for melanoma tumor development. Furthermore, versican would also, directly or indirectly, influence cellular functions such as proliferation, adhesion, migration, and survival, further contributing to the altered functional properties of malignant melanoma cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. F. X. Real (Institut Municipal d'Investigacions Mèdiques, Barcelona, Spain) for providing the melanoma cell lines; Drs. J. Baulida and A. García de Herreros (Institut Municipal d'Investigacions Mèdiques, Barcelona, Spain) and Dr. M. Duñach (Departament de Bioquímica i Biologia Molecular, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain) for providing expression and reporter vectors; and Dr. N. Gómez and J. M. Lizcano (Departament de Bioquímica i Biologia Molecular, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain) and Dr. C. Ciudad (Departament de Bioquímica i Biologia Molecular, Universitat de Barcelona, Spain) for the ERK, JNK, and c-Jun antibodies. We also thank Anna Vilalta for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by Grants SAF2003-08750 from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (to A. B.), FIS-PI-06194 from the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (to A. F.), and 2005SGR00542 from the Generalitat de Catalunya (to A. B.). This work was also supported in part by the FEDER program of the European Union.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; GFP, green fluorescent protein; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; RT, reverse transcription; DN, dominant negative; DP, dominant positive; TCF, T cell factor.

References

- 1.Hsu, M. Y., Meier, F., and Herlyn, M. (2002) Differentiation 70 522-536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee, J. T., and Herlyn, M. (2007) J. Cell Biochem. 101 862-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Touab, M., Villena, J., Barranco, C., Arumi-Uria, M., and Bassols, A. (2002) Am. J. Pathol. 160 549-557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docampo, M. J., Rabanal, R. M., Miquel-Serra, L., Hernandez, D., Domenzain, C., and Bassols, A. (2007) Am. J. Vet. Res. 68 1376-1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Touab, M., Arumi-Uria, M., Barranco, C., and Bassols, A. (2003) Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 119 587-593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wight, T. N. (2002) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14 617-623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakko, A. J., Ricciardelli, C., Mayne, K., Suwiwat, S., LeBaron, R. G., Marshall, V. R., Tilley, W. D., and Horsfall, D. J. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 4786-4791 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang, B. L., Zhang, Y., Cao, L., and Yang, B. B. (1999) J. Cell Biochem. 72 210-220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutt, S., Kleber, M., Matasci, M., Sommer, L., and Zimmermann, D. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 12123-12131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ricciardelli, C., Russell, D. L., Ween, M. P., Mayne, K., Suwiwat, S., Byers, S., Marshall, V. R., Tilley, W. D., and Horsfall, D. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 10814-10825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang, Y., Cao, L., Yang, B. L., and Yang, B. B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 21342-21351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemire, J. M., Merrilees, M. J., Braun, K. R., and Wight, T. N. (2002) J. Cell Physiol. 190 38-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serra, M., Miquel, L., Domenzain, C., Docampo, M. J., Fabra, A., Wight, T. N., and Bassols, A. (2005) Int. J. Cancer 114 879-886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheng, W., Wang, G., La Pierre, D. P., Wen, J., Deng, Z., Wong, C. K., Lee, D. Y., and Yang, B. B. (2006) Mol. Biol. Cell 17 2009-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu, Y., Sheng, W., Chen, L., Dong, H., Lee, V., Lu, F., Wong, C. S., Lu, W. Y., and Yang, B. B. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15 2093-2104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zizola, C. F., Julianelli, V., Bertolesi, G., Yanagishita, M., and Calvo, J. C. (2007) Matrix Biol. 26 419-430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yee, A. J., Akens, M., Yang, B. L., Finkelstein, J., Zheng, P. S., Deng, Z., and Yang, B. (2007) Breast Cancer Res. 9 R47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miquel-Serra, L., Serra, M., Hernandez, D., Domenzain, C., Docampo, M. J., Rabanal, R. M., de Torres, I., Wight, T. N., Fabra, A., and Bassols, A. (2006) Lab. Investig. 86 889-901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyama, H., Hibi, T., Isogai, Z., et al. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 170 1086-1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng, P. S., Wen, J., Ang, L. C., Sheng, W., Viloria-Petit, A., Wang, Y., Wu, Y., Kerbel, R. S., and Yang, B. B. (2004) FASEB J. 18 754-756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaPierre, D. P., Lee, D. Y., Li, S. Z., Xie, Y. Z., Zhong, L., Sheng, W., Deng, Z., and Yang, B. B. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 4742-4750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wight, T. N. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13 4933-4937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theocharis, A. D., Tsolakis, I., Tzanakakis, G. N., and Karamanos, N. K. (2006) Adv. Pharmacol. 53 281-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams, D. R., Jr., Presar, A. R., Richmond, A. T., Mjaatvedt, C. H., Hoffman, S., and Capehart, A. A. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 334 960-966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricciardelli, C., Brooks, J. H., Suwiwat, S., Sakko, A. J., Mayne, K., Raymond, W. A., Seshadri, R., LeBaron, R. G., and Horsfall, D. J. (2002) Clin. Cancer Res. 8 1054-1060 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Read, J. T., Rahmani, M., Boroomand, S., Allahverdian, S., McManus, B. M., and Rennie, P. S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 31954-31963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kodama, J., Hasengaowa, Kusumoto, T., Seki, N., Matsuo, T., Ojima, Y., Nakamura, K., Hongo, A., and Hiramatsu, Y. (2007) Ann. Oncol. 18 269-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theocharis, A. D. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1588 165-172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domenzain, C., Docampo, M. J., Serra, M., Miquel, L., and Bassols, A. (2003) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1642 107-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naso, M. F., Zimmermann, D. R., and Iozzo, R. V. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 32999-33008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahmani, M., Read, J. T., Carthy, J. M., et al. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 13019-13028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahmani, M., Wong, B. W., Ang, L., Cheung, C. C., Carthy, J. M., Walinski, H., and McManus, B. M. (2006) Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84 77-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houghton, A. N., Real, F. X., Davis, L. J., Cordon-Cardo, C., and Old, L. J. (1987) J. Exp. Med. 165 812-829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.den Dunnen, J. T., and Antonarakis, S. E. (2000) Hum. Mutat. 15 7-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paulus, W., Baur, I., Dours-Zimmermann, M. T., and Zimmermann, D. R. (1996) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 55 528-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schreiber, E., Matthias, P., Muller, M. M., and Schaffner, W. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17 6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogt, P. K. (2001) Oncogene 20 2365-2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaulian, E., and Karin, M. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4 E131-E136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez-Bergami, P., Huang, C., Goydos, J. S., et al. (2007) Cancer Cell. 11 447-460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ding, Q., Xia, W., Liu, J. C., et al. (2005) Mol. Cell 19 159-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim, D., Rath, O., Kolch, W., and Cho, K. H. (2007) Oncogene 26 4571-4579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorden, A., Osman, I., Gai, W., He, D., Huang, W., Davidson, A., Houghton, A. N., Busam, K., and Polsky, D. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 3955-3957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maldonado, J. L., Fridlyand, J., Patel, H., Jain, A. N., Busam, K., Kageshita, T., Ono, T., Albertson, D. G., Pinkel, D., and Bastian, B. C. (2003) J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 95 1878-1890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chudnovsky, Y., Khavari, P. A., and Adams, A. E. (2005) J. Clin. Investig. 115 813-824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haluska, F. G., Tsao, H., Wu, H., Haluska, F. S., Lazar, A., and Goel, V. (2006) Clin. Cancer Res. 12 Suppl. 7, 2301s-2307s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Govindarajan, B., Bai, X., Cohen, C., Zhong, H., Kilroy, S., Louis, G., Moses, M., and Arbiser, J. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 9790-9795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozanne, B. W., Spence, H. J., McGarry, L. C., and Hennigan, R. F. (2007) Oncogene 26 1-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schonherr, E., Jarvelainen, H. T., Sandell, L. J., and Wight, T. N. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 17640-17647 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan, C., and Boyd, D. D. (2007) J. Cell Physiol. 211 19-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Briggs, J., Chamboredon, S., Castellazzi, M., Kerry, J. A., and Bos, T. J. (2002) Oncogene 21 7077-7091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reya, T., and Clevers, H. (2005) Nature 434 843-850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clevers, H. (2006) Cell 127 469-480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Widlund, H. R., Horstmann, M. A., Price, E. R., Cui, J., Lessnick, S. L., Wu, M., He, X., and Fisher, D. E. (2002) J. Cell Biol. 158 1079-1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen, D., Xu, W., Bales, E., et al. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 6626-6634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larue, L., and Delmas, V. (2006) Front. Biosci. 11 733-742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorsky, R. I., Moon, R. T., and Raible, D. W. (1998) Nature 396 370-373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunn, K. J., Williams, B. O., Li, Y., and Pavan, W. J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 10050-10055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willert, J., Epping, M., Pollack, J. R., Brown, P. O., and Nusse, R. (2002) BMC Dev. Biol. 2 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goodwin, A. M., and D'Amore, P. A. (2002) Angiogenesis 5 1-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jorda, M., Olmeda, D., Vinyals, A., Valero, E., Cubillo, E., Llorens, A., Cano, A., and Fabra, A. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118 3371-3385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nyormoi, O., and Bar-Eli, M. (2003) Clin. Exp. Metastasis 20 251-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tellez, C., McCarty, M., Ruiz, M., and Bar-Eli, M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 46632-46642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsao, H., Goel, V., Wu, H., Yang, G., and Haluska, F. G. (2004) J. Investig. Dermatol. 122 337-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.