Abstract

Proteins secreted from Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs) play important roles in regulating inflammatory and hemostatic responses. Inflammation is associated with the extracellular acidification of tissues and blood, conditions that can alter the behavior of secreted proteins. The effect of extracellular pH (pHo) on the release of von Willebrand factor (VWF), the VWF-propolypeptide (Proregion), interleukin-8, eotaxin-3, P-selectin, and CD63 from WPBs was investigated using biochemical approaches and by direct optical analysis of individual WPB fusion events in human endothelial cells expressing green or red fluorescent fusions of these different cargo proteins. Between pHo 7.4 and 7.0, ionomycin-evoked WPB exocytosis was characterized by the adhesion of VWF to the cell surface and the formation of long filamentous strands. The rapid dispersal of Proregion, interleukin-8, and eotaxin-3 into solution, and of P-selectin and CD63 into the plasma membrane, was unaltered over this pHo range. At pHo 6.8 or lower, Proregion remained associated with VWF, in many cases WPB failed to collapse fully and VWF failed to form filamentous strands. At pHo 6.5 dispersal of interleukin-8, eotaxin-3, and the membrane protein CD63 remained unaltered compared with that at pHo 7.4; however, P-selectin dispersal into the plasma membrane was significantly slowed. Thus, extracellular acidification to levels of pHo 6.8 or lower significantly alters the behavior of secreted VWF, Proregion, and P-selectin while rapid release of the small pro-inflammatory mediators IL-8 and eotaxin-3 is essentially unaltered. Together, these data suggest that WPB exocytosis during extracellular acidosis may favor the control of inflammatory processes.

Local acidosis is associated with inflammation and ischemia and can have significant effects on the normal function of cells, tissues, cellular, and blood components, in particularly those associated with the immune, vascular, and hemostatic systems (1-8). Endothelial cells regulate inflammatory, vascular and hemostatic responses through the secretion of a wide range of bioactive molecules from specialized secretory organelles, the Weibel-Palade bodies (WPBs).3

The major WPB core proteins are von Willebrand factor (VWF) and the VWF-propolypeptide (Proregion). VWF is synthesized as a pre-proprotein comprising an N-terminal signal peptide (pre-), and several distinct repeating structural domains (termed A, B, C, and D) arranged as D1-D2-D′-D3-A1-A2-A3-D4-B1-B2-B3-C1-C2-CK (9). During translation, the signal peptide is removed to yield proVWF, which then undergoes disulfide-linked dimerization to produce proVWF dimers (10). The Proregion domains (D1-D2) are cleaved from the main peptide in the Golgi apparatus, and further disulfide bond formation produces VWF multimers. The two resulting proteins, VWF and Proregion are co-packaged into the WPB where they noncovalently associate to form ordered tubules in a pH- and Ca2+-dependent fashion (11). Other physiologically important WPB proteins include P-selectin, interleukin-8 (IL-8), eotaxin-3, osteoprotegerin, and angiopoietin-2, (reviewed in Ref. 12).

At physiological extracellular pH (pHo 7.4) the majority of agonist-evoked WPB fusion events (∼75-90%) result in complete exocytosis and release of the stored molecules (13, 14). Secreted VWF adheres to the cell surface and can form long filamentous strands, particularly under flow conditions, that are essential for the efficient capture of platelets from solution both in vitro and in vivo (e.g. Ref. 15). Imaging individual WPB exocytotic events in live endothelial cells expressing fluorescent WPB cargo molecules has shown that Proregion, along with IL-8, disperse quickly into solution, while P-selectin rapidly diffuses into the plasma membrane at sites of fusion (14, 16).

Under acidic conditions, however, the behavior of VWF and Proregion, are reported to change. At pHo 6.4 or lower Proregion remains associated with VWF, either at the cell surface after stimulated exocytosis of WPBs (17) or in the cell following removal of the WPB membrane by detergent treatment (15). In addition, the unfurling of VWF to form long filamentous strands is attenuated (15, 17), a situation that impairs its capacity to efficiently support platelet adhesion (15). Retention of Proregion at the cell surface has led to speculation that it might play some biological role at such sites (17). In vitro Proregion is a ligand for the integrins α4β1 (VLA-4) (18) and α9β1 (VLA-9) (19) present on monocytes, leukocytes, eosinophils (VLA-4), and neutrophils (VLA-9). Thus it is possible that at sites of local acidosis produced during inflammation or ischemia, Proregion could play a role, along with other secreted factors, in regulating inflammatory responses. The influence of extracellular acidification on the release of these other secreted factors (e.g. IL-8, eotaxin-3, and P-selectin) is not known.

pHo values of 6.4 or lower represent extreme conditions of acidosis, with decreases in pHo between 7.2 and 6.5 more typically reported during inflammation or ischemia (7, 20-26). The aim of this study was to determine the influence of extracellular acidification in this range (pHo 7.4-6.5) on the release of a variety of soluble and membrane proteins of the WPB involved in coagulant and inflammatory responses. Specifically, we define more precisely the value of pHo at which VWF fails to form filamentous strands and remains associated with Proregion at the cell surface, demonstrate the rapid reversibility of this pH-dependent association at individual sites of WPB fusion, and examine in detail the influence of extracellular acidification on the release and dispersal of fluorescent fusion proteins of the soluble mediators IL-8, eotaxin-3, and the membrane proteins P-selectin and CD63 from individual WPBs.

The data show that the external conditions into which WPB deliver their cargo has significant effects on the dispersal and behavior of some but not other secreted molecules. Under acidic conditions, these changes could lead to a subtle shift from a coagulant to a more inflammatory phenotype. The data also highlight a more general problem of interpreting biochemical data of soluble secreted proteins in terms of underlying secretory granule exocytosis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Tissue Culture and Transfection—Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from TCS Cellworks (Botolph Claydon, UK) or PromoCell GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany), grown, and transfected as previously described (16). Cells were used 1 to 2 days after nucleofection.

Antibodies, Reagents, Expression Vectors, and Preparation of Buffered Solutions—Rabbit polyclonal anti-human VWF was from Dako Ltd (Ely, UK). A sheep polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody, a mouse monoclonal anti-human VWF (MCA127) antibody, and a mouse monoclonal anti-P-selectin (AK6) antibody were from Serotec (Kidlington, UK). Polyclonal antibodies specific to the putative C terminus of human Proregion were raised in rabbit and in chicken.4 rhIL-1β, rhIL-4, a goat anti-human IL-8 antibody, and a mouse anti-eotaxin-3 antibody were purchased from R&D systems (Abingdon, UK). A monoclonal antibody to the VWF propeptide (CLB-Pro35) (27) was provided by Dr. J. Voorberg (Dept. of Plasma Proteins, Sanquin Research, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Secondary antibodies coupled to fluorophores were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise. pVWF-EGFP, P-selectin-mRFP, mRFP-CD63, and IL-8-mCherry were as previously described (14, 16). Monomeric EGFP was made from the pEGFP-N1 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) by site-directed mutagenesis utilizing QuikChange (Stratagene) strategy. The alanine at position 206 was substituted with a lysine (A206K) using the following primers CTACCTGAGCTACCAGTCCaagCTGAGCAAAGACCCC (forward) and GGGGTCTTTGCTCAGcttGGACTGGTAGCTCAGGTA (reverse) (29). Unwanted mutations elsewhere in the plasmid were prevented by re-cloning the sequence encoding mEGFP into AgeI/BsrGI-digested N1 vector to produce pmEGFP-N1. The region encoding mEGFP was sequence-verified. Proregion-mEGFP was made by transferring the entire Proregion cDNA from Proregion-EGFP (16) into pmEGFP-N2 as an EcoRI/BamHI fragment. pmEGFP-N2 was obtained from pmEGFP-N1 digested with AgeI and re-ligated after filling in the 5′ overhangs of the plasmid with T4 DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The pmEGFP-N2 vector was also sequence-verified. P-selectin-EGFP was derived from P-selectin-YFP (14) by exchanging YFP with EGFP as an AgeI/BsrGI fragment cut from pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). EGFP-CD63 was a gift from Prof. Paul Luzio, Cambridge University. Exotaxin-3-mEGFP was made as follows, a sequence-verified human eotaxin-3 image clone (7262706 (BR7-d4) was purchased from Geneservice Ltd (Cambridge, UK), amplified using primers CTAAGCTTATGATGGGCCTCTCCTTG (forward) and CTTGGATCCCGCAATTGTTTCGGAGTTTTCAG (reverse), digested with HindIII/BamHI and ligated into HindIII/BamHI digested pmEGFP-N1. Experiments were carried out in physiological saline solution (140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, 0.2% bovine serum albumin) or bicarbonate-free M199 culture medium (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 0.2% bovine serum albumin and buffered between pH 8.0 and 6.5 using a combination of HEPES (10 mm) and PIPES (10 mm). Stock solutions of 0.5 m PIPES and 0.5 m HEPES at the required pH (8.0-6.5) were made by combining appropriate amounts of HEPES free acid, disodium HEPES, PIPES free acid, and disodium PIPES, calculated using the Henderson-Hasselbach equation; pH = pKa + log[base]/[acid], where the pKa of PIPES and HEPES were taken as 6.8 and 7.5, respectively. The pH of all solutions was measured and final small adjustments made with 4 m NaOH as required.

Immunocytochemistry—Nucleofected HUVEC were processed for immunofluorescence as described previously (16). Endogenous IL-8 or eotaxin-3 was up-regulated by incubating with rhIL-1β (24 h, 1 ng/ml) or rhIL-4 (24 h, 20 ng/ml). To differentiate between secreted and non-secreted VWF, cells were stimulated for 5 min at 37 °C with vehicle (0.01% ethanol) or ionomycin (2 μm), at different extracellular pH, after which the coverslips of cells were placed into fresh buffer containing either a sheep or a rabbit polyclonal anti-VWF antibody at 4 °C (see figure legends 2 and 4) and incubated for 30 min. Cells were then washed three times prior to fixation and permeabilization and probed with either a rabbit polyclonal or mouse monoclonal anti-VWF antibody (see figure legends 2 and 4), to detect intracellular VWF, and either a rabbit or chicken polyclonal antibody specific for the cleaved and processed form of Proregion found in WPBs (30), or IL-8 or eotaxin-3 specific antibodies.

Measurement of Endogenous and Secreted VWF, Proregion, and IL-8 by Specific ELISA—Cells were transferred into serum, bicarbonate-free M199 buffered with HEPES to pH 7.4 at 37 °C for 50 min. The medium was changed for fresh serum-free medium buffered to pHo 7.4 or 6.5 as described above, and cells incubated for 10 min before fresh medium (pHo 7.4 or 6.5) containing 2 μm ionomycin or vehicle (0.01% ethanol) was added for 5 min (1st 5-min period; see Fig. 5). Medium was then removed for assay and replaced in all cases with fresh ionomycin-free medium at pHo7.4 for 5 min (2nd 5-min period; see Fig. 5) followed by collection of this medium. All medium samples were centrifuged to remove cell debris and stored at -20 °C. Cell lysates were prepared in serum and bicarbonate-free M199 containing protease inhibitors (Sigma, Gillingham, UK; 1/100 dilution,) and 1% Triton X-100, centrifuged (13,200 rpm, 5 min), and the supernatant collected and stored at -20 °C. Prior to assay, the pH of medium and lysate samples from pHo 6.5 experiments was adjusted to pHo 7.4 using 22.5 μl (into 900 μl of medium sample) or 25 μl (into 1000 μl of lysate sample) of 200 mm unbuffered TRIS base and analyzed for VWF and IL-8 in duplicate by ELISA using commercial reagents and standard protocols (VWF; Dako, Ely, UK, IL-8; human IL-8 ELISA construction kit; Anti-genix America, Huntington Station, NY). The concentrations of VWF, in milliinternational unit per milliliter (mIU/ml), were calculated from a standard curve as previously described (30). Medium and lysates were also assayed for Proregion using a sandwich ELISA. ELISA plates were coated with 1.15 μg/ml monoclonal CLB-Pro35 (27). Detection used a rabbit polyclonal antibody specific to the putative C terminus of Proregion,4 followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Proregion concentrations were calculated from a standard curve made up of serial dilutions of normal human serum and expressed as arbitrary units.

FIGURE 5.

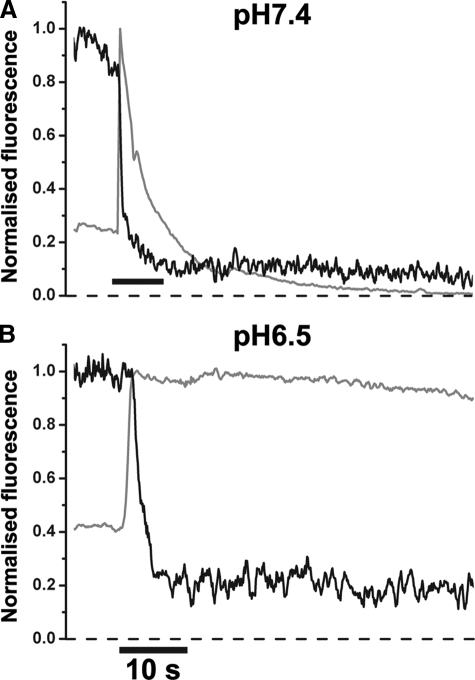

Extracellular acidification does not significantly alters the dispersal of IL-8-mCherry following WPB exocytosis. Representative time courses for the change in fluorescence of Proregion-mEGFP (gray traces) and IL-8-mcherry (black traces) from single WPBs during ionomycin evoked exocytosis into medium buffered to pHo 7.4 (A) or pHo 6.5 (B). Data were acquired sequentially at 30 frames per second and are displayed as a 5-frame average of the raw data.

Epifluorescence Imaging of Changes in Intracellular Free Calcium Ion Concentration ([Ca2+]i) and WPB Exocytosis in Living Cells—Epifluorescence imaging of changes in [Ca2+]i and WPB exocytosis in living cells, or the slow dissociation of Proregion-mEGFP from the cell surface was carried out as previously described (13, 16). The time course for dispersal of Proregion-mEGFP were determined from time lapse movies as previously described (16).

Confocal Imaging of WPB Exocytosis—Confocal imaging of WPB exocytosis was carried out as previously described (13). Cells expressing Proregion-mEGFP were transfered into Ringer solution (140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 2 mm MgCl2, 10 mm glucose, 10 mm MES, pH 5.80) containing 7 μm FM4-64 (Molecular Probes) and stimulated with 1 μm ionomycin. Confocal images were acquired at ∼7.4 frames/s.

Analysis—Image analysis was carried out as previously described (13, 14, 16). Results are expressed as mean ± S.E. or S.D. as indicated. Statistical differences (at 95% confidence limit) between population means were determined using a non-paired two way t test.

RESULTS

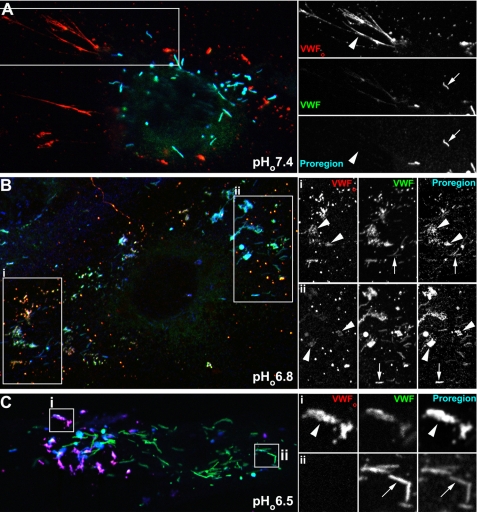

Association of Endogenous Proregion with Secreted VWF Occurs between pHo 7.0 and 6.8—To establish more precisely the level of extracellular acidification required for the retention of Proregion with VWF at the cell surface, we first determined, by immunofluorescence, the localization of Proregion, extracellular VWF (VWFo), and non-secreted VWF (within WPB) following stimulation at pHo buffered to 7.4, 7.2, 7.0, 6.8, and 6.5. Ionomycin was used as the secretagogue in all experiments because its ability to evoke WPB fusion was only marginally affected by extracellular acidification over the range pHo 7.4 to pHo 6.5 (supplemental Fig. S1). In nonstimulated cells, very little VWFo could be observed between pHo 7.4 and 6.5, and all Proregion immunoreactivity co-localized with intracellular VWF within WPB (supplemental Fig. S2a). Following stimulation at pHo 7.4, 7.2, or 7.0 extracellular deposits of VWF often comprising long filamentous strands were observed, but found to be devoid of Proregion immunoreactivity (Fig. 1A, pHo 7.4, and supplemental Fig. S2b, pHo 7.4, 7.2, or 7.0). Proregion immunoreactivity was seen within morphologically distinct WPB that had not undergone exocytosis (negative for the extracellular VWF antibody). At pHo 6.8, Proregion immunoreactivity could be observed associated with VWFo, and VWFo no longer formed long filamentous strands (Fig. 1B). At pHo 6.5, Proregion was exclusively associated with VWFo, comprising dense patches on the cell surface or within membrane cavities or partially or noncollapsed WPB, and again no filamentous strands of VWFo could be observed (Fig. 1C). These data confirm and extend the observations of Vischer and Wagner (17) to show that the association of secreted Proregion with VWFo at the cell surface occurs between pHo 7.0 and 6.8, conditions that are more commonly associated with inflammation and ischemia (see above for references).

FIGURE 1.

Proregion associates with VWFo at pHo 6.8 and lower. Representative examples of individual HUVEC following stimulation with 2 μm ionomycin at pHo 7.4 (A), 6.8 (B), and 6.5 (C). The left panels show color merged images of VWFo (red), intracellular VWF (green), and Proregion (blue) immunoreactivity. VWFo (sheep antibody) immunoreactivity was obtained on the cells while alive and intact (see “Experimental Procedures”), and intracellular VWF (mouse antibody) immunoreactivity and total Proregion (rabbit antibody) immunoreactivity on the same cells after removal of the primary VWF antibody followed by fixation and permeabilization. On the right, the individual wavelength channels from the regions indicated by the white boxes are shown on an expanded scale. Large arrowheads in the right hand right panels indicate the position of VWFo, and similar arrowheads point to the absence (A) or presence (B and C) of Proregion associated with VWFo. The small arrows in the right hand right panels show the co-localization of VWF and Proregion within non-secreted WPBs. Images for each antigen were acquired sequentially as single, confocal, optical sections. (Images for the same antigen at different pH values were acquired using the same nonsaturating settings.)

pHo-dependence of the Dynamics of Proregion Dispersal from Individual WPBs—We next determined directly the pHo-dependence of Proregion-mEGFP dispersal from individual WPBs in living HUVEC over the range pHo 8.0-6.5. The fluorescence of EGFP is sensitive to pH and was used here to indicate the point of WPB fusion, whereupon the intra-WPB pH increases to that of the bathing medium (13). Fusion of WPBs into more acidic medium results in smaller absolute increases in intra-WPB pH, and consequently smaller increases in EGFP fluorescence (13). This manifests itself in plots of the WPB fluorescence intensity, normalized to the peak of the fluorescence increase due to fusion versus time, as an elevated baseline value for the normalized fluorescence prior to fusion (e.g. Fig. 2, A and B, black traces).

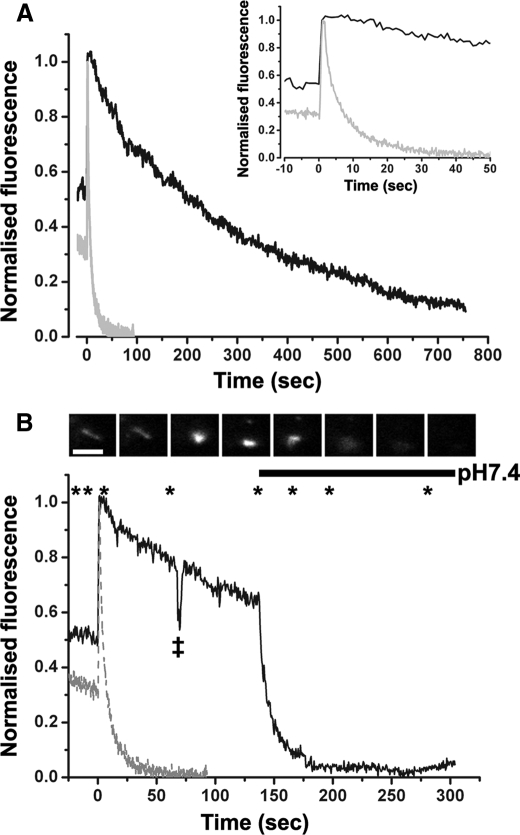

FIGURE 2.

Extracellular acidification and the dispersal of Proregion-mEGFP during WPB exocytosis. Panel A shows a representative time course for the change in fluorescence of Proregion-mEGFP in a single WPB during exocytosis evoked by 2 μm ionomycin into medium buffered to pHo 7.4 (gray trace) or pHo 6.5 (black trace). Fluorescence in each case was normalized to the peak increase. Inset in panel A is the early phase of the fluorescence changes on an expanded time scale. The solid black trace in panel B shows the effect of switching the extracellular solution pH from 6.5 to 7.4 on the loss of Proregion-mEGFP fluorescence. Asterisks indicate points at which images, shown in the montage in the upper panel of B, were taken. For reference the time course for the changes in fluorescence intensity of Proregion-mEGFP during WPB fusion into medium buffered to pH 7.4 (taken from panel A) is shown as a gray dashed line. Images were acquired at 10 frames per second, and the time course data shown were obtained from a 5-frame average of the raw data (0.5-s time resolution). The abrupt transient drop in fluorescence on the black trace, indicated by a double cross, corresponds to a focus adjustment. The scale bar in the image montage is 2 μm.

At pHo 8.0 and 7.4 there were no differences in the half-times for dispersal of Proregion-mEGFP (pH 8.0; 2.7 ± 3.17s, S.D. n = 24 WPBs, pH 7.4; 2.7 ± 3.33s, S.D. n = 120 WPB, pH 7.0). At pHo 7.0 the time for dispersal increased slightly, although this was not significantly different from that at pHo 7.4 (pH 7.0; 4.3 ± 3.17s, S.D. n = 48 WPBs); however, at pHo 6.5 its dispersal from the cell surface was dramatically slowed (pHo 6.5; 266.3 ± 26.26s, S.D. n = 153 WPBs; Fig. 2A), and Proregion-mEGFP remained associated with VWF in globular deposits on the cell surface or within partially collapsed or noncollapsed WPB (e.g. supplemental Fig. S3). The cell surface retention of Proregion-mEGFP could be rapidly reversed by switching the extracellular pH from pHo 6.5 to pHo 7.4 (Fig. 2B).

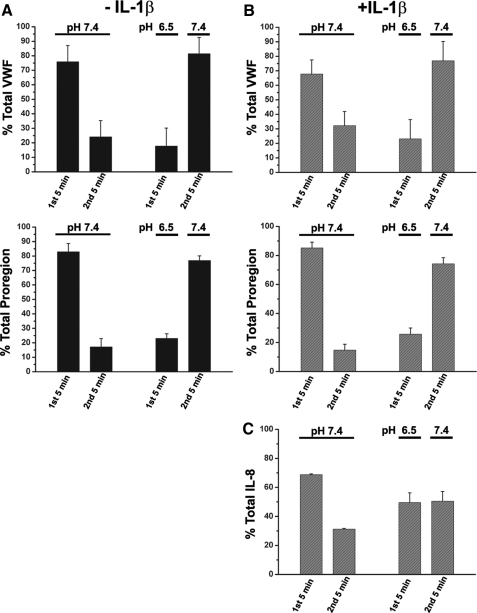

pHo and the Relationship between WPB Exocytosis and the Appearance of Soluble VWF and Proregion—The extent of WPB exocytosis is often inferred from the amounts of soluble VWF or Proregion that appear in the medium of stimulated cells. However, the data described above, and those of Vischer and Wagner (17), predict that the relationship between WPB fusion and the appearance of soluble VWF and Proregion in the medium will be more complex under acidic conditions. To examine this, we looked at the appearance of soluble VWF and Proregion in cells stimulated for 5 min at either pHo 7.4 or 6.5 and then during a second 5-min period of exposure to fresh stimulus-free medium at pHo 7.4. Consistent with the prediction we found that ionomycin-evoked WPB exocytosis at pHo 6.5 resulted in a profound decrease (70-80%) in the appearance of soluble Proregion or VWF, and that the secreted material was readily recovered by subsequently exposing the stimulated cells to fresh stimulus-free medium at pHo 7.4 (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Extracellular acidification reduces the appearance of soluble secreted VWF and Proregion but has a less profound effect on IL-8. Panel A shows the VWF (upper panel) and Proregion (lower panel) detected in the medium of IL-1β naïve cells during a 5-min period of stimulation with 2 μm at the extracellular pH indicated (1st 5 min), followed by a subsequent 5-min period of incubation in ionomycin-free medium at pHo 7.4 (2nd 5 min). Data are shown as the % of total VWF or Proregion detected over both 5-min time periods. Panel B shows the identical experiment in IL-1β-pretreated cells. Data for detection of soluble IL-8 expressed in the same way is shown in panel C. Each data column represents the pooled mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate.

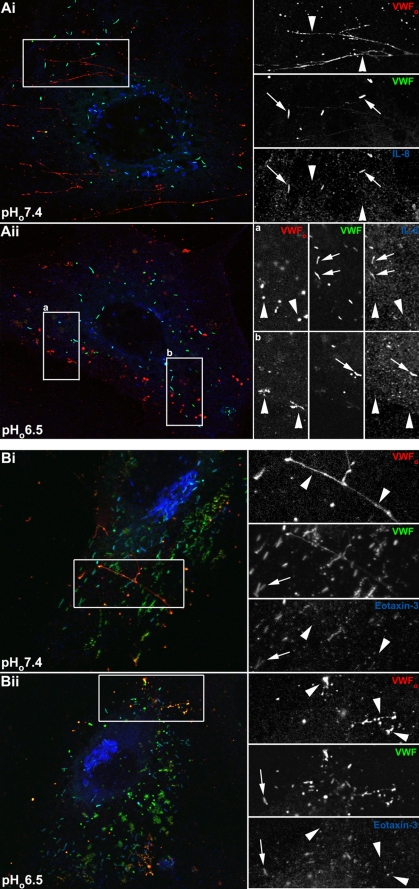

Release of IL-8 or Eotaxin-3 Is Largely Unaffected by Extracellular Acidification to pHo 6.5—IL-8-mCherry released from single WPBs at physiological pHo disperses rapidly from the site of exocytosis (14); however, its behavior following release under acidic conditions is not known. The behavior of eotaxin-3 released from individual WPBs has not been directly determined under any conditions. We first determined, by immunofluorescence, the cell surface localization of VWFo and endogenous IL-8 or eotaxin-3 following WPB exocytosis evoked by ionomycin between pHo 7.4 and 6.5. Endogenous IL-8 or eotaxin-3 was up-regulated prior to stimulation with ionomycin by IL-1β or IL-4 pretreatment, respectively. In nonstimulated cells, no extracellular IL-8 or eotaxin-3 immunoreactivity could be observed associated with the cell surface (supplemental Fig. S4A). Following WPB exocytosis at pHo 7.4 or 6.5, neither IL-8 (Fig. 4A) nor eotaxin-3 (Fig. 4B) could be detected associated with filamentous strands (pHo 7.4; Fig. 4, Ai and Bi) or globular patches (pHo 6.5; Fig. 3, Aii and Bii) of VWFo. These data indicate that the IL-8 and eotaxin-3 released from WPBs do not remain associated with VWFo during extracellular acidosis.

FIGURE 4.

IL-8 and eotaxin-3 are not associated with secreted VWFo at pHo 7.4 or 6.5. Panels A and B show representative examples of individual HUVEC following stimulation with 2 μm ionomycin at pHo 7.4. The left panels show color merged images of VWFo (red), intracellular VWF (green), and IL-8 (blue; panel A) or eotaxin-3 (blue; panel B) immunoreactivity. In panel A, VWFo (rabbit antibody) immunoreactivity was obtained on the cells while alive and intact (see “Experimental Procedures”), and intracellular VWF (mouse antibody) and IL-8 immunoreactivity on the same cells after removal of the primary VWF antibody followed by fixation and permeabilization. In panel B, a sheep polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody was used to detect VWFo, a rabbit polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody for intracellular VWF, and a mouse monoclonal antibody to human eotaxin-3. On the right, the individual wavelength channels from the regions indicated by the white boxes are shown on expanded scales. Large arrowheads in the right hand right panels indicate the position of VWFo, and similar arrowheads point to the absence of IL-8 (A) or eotaxin-3 (B) associated with VWFo at both pHo 7.4 or 6.5. The small arrows in the right hand right panels show the co-localization of VWF and IL-8 (A) and eotaxin-3 (B) within nonsecreted WPBs.

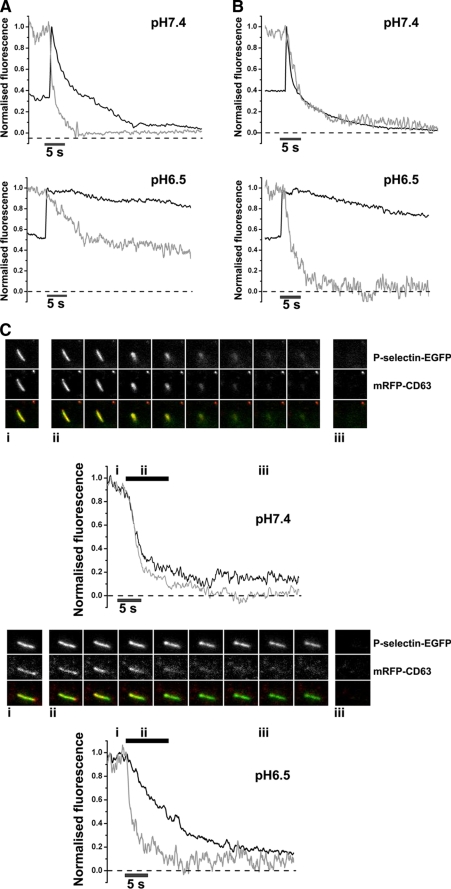

To determine directly the dynamics of IL-8 release from individual WPBs, live cells co-expressing IL-8-mCherry and Proregion-mEGFP were imaged, using the Proregion-mEGFP fluorescence to determine the point of WPB fusion during stimulation. The half-times for dispersal of IL-8-mCherry from individual WPB sites were the same at pHo 7.4 (1.0 ± 1.7, S.D. n = 88 WPBs) and pHo 6.5 (1.3 ± 2.2, S.D. n = 17 WPBs; Fig. 5). Consistent with these data, we found that extracellular acidification had a much less pronounced effect on the stimulated appearance of endogenous soluble IL-8, assayed by specific ELISA (Fig. 3C). To study the behavior of eotaxin-3 during release from individual WPBs we constructed eotaxin-3-mEGFP and expressed this in HUVEC to label WPBs (supplemental Fig. S5). Consistent with immunofluorescence data, the dispersal of eotaxin-3-mEGFP from WPBs during exocytosis was not affected by extracellular acidification (pHo 7.4; 3.0 ± 3.1s, S.D. n = 7 WPBs, pHo 6.5; 3.1 ± 2.9s, S.D. n = 11 WPBs).

Differential Effect of Extracellular Acidification on the Release of P-selectin and CD63 from Individual WPBs—The effects of extracellular acidification on the delivery of P-selectin and CD63 to the plasma membrane during WPB exocytosis are not known. Single WPB, containing Proregion-mEGFP and P-selectin-mRFP or mRFP-CD63 were imaged during stimulation at pHo ranging from 8.0 to 6.5. Between pHo 8.0 and 7.0 the kinetics of dispersal of P-selectin-mRFP were similar (half-times for dispersal from the site of fusion; pHo 8.0; 2.9 ± 0.8s, S.E. n = 24 WPBs, pHo 7.4; 2.1 ± 0.4s, S.E. n = 58 WPBs, pHo 7.0; 5.7 ± 1.6s, S.E. n = 48 WPBs). However, at pHo 6.5, the dispersal of P-selectin was substantially slowed (10.9 ± 1.8s, S.E. n = 77 WPBs Fig. 6A). In contrast the dispersal of mRFP-CD63 was not altered between pHo 7.4 (half times for dispersal of 1.8 ± 0.4s, S.E. n = 63 WPBs, Fig. 6B) and 6.5 (2.1 ± 0.4s, S.E. n = 83 WPBs at pHo6.5; Fig. 6B). These differences in behavior were confirmed in WPB co-expressing mRFP-CD63 and P-selectin-EGFP (Fig. 6C and supplemental Movies S1 and S2). Similar data were obtained using EGFP-CD63 and P-selectin-mRFP expressing WPB (not shown). Consistent with this, immunofluorescence data showed that endogenous CD63 was not associated with filamentous strands (pHo 7.4) or globular deposits (pHo 6.5) of VWFo following stimulation (not shown). No evidence was found for P-selectin association with filamentous strands of VWFo at pHo7.4 (not shown), but it could be found co-localized with globular VWFo deposits at pHo 6.5 (supplemental Fig. S6).

FIGURE 6.

Extracellular acidification slows the release of P-selectin but not CD63 from WPBs. Panels A and B show representative examples of the time course for dispersal of P-selectin-mRFP (A, gray traces) and mRFP-CD63 (B, gray traces) from individual WPBs fusing into extracellular medium buffered to pHo 7.4 (upper panels of A and B) or pHo 6.5 (lower panels of A and B). In each case, the WPBs co-expressed Proregion-mEGFP (A and B, black traces) allowing the point of fusion to be determined from the increase in luminal EGFP fluorescence (13). Proregion-mEGFP fluorescence was normalized to the peak fluorescence at the point of fusion, and to the fluorescence prior to fusion for P-selectin-mRFP and mRFP-CD63. Panel C shows examples of WPBs co-expressing P-selectin-EGFP and mRFP-CD63 during exocytosis into medium buffered to pHo 7.4 (upper panel) or pHo 6.5 (lower panel). The time course for dispersal of P-selectin-EGFP (black traces) and mRFP-CD63 (gray traces) is shown along with images of the WPBs corresponding to the points indicated (i, ii, and iii) on the fluorescence time course plots. Color-merged images show mRFP-CD63 (red) and P-selectin-EGFP (green). Images were acquired sequentially at 30 frames per second, and cells were stimulated with 2 μm ionomycin.

H+ and the Expulsion of Major Core Proteins from WPB during Exocytosis—At pHo 7.4, the fusion of WPB to the plasma membrane is characterized by a change in morphology, from a cigar to spherical shape, followed by expulsion of contents (13). Imaging single WPB containing fluorescent cargo molecules showed that at pHo 6.5 the changes in WPB morphology were often much less pronounced with some organelles showing little sign of collapse (e.g. supplemental Fig. S3, Fig. 6C, and supplemental Movie S2). Reducing pHo further, to 5.8, a value close to the resting intra-WPB pH (pH 5.5 and Ref. 13), resulted in the failure of WPB to collapse and the retention of the major core proteins VWF and Proregion within a membrane-bound cavity connected to the plasma membrane (supplemental Fig. S7).

DISCUSSION

Understanding the role of the WPB in health and disease requires not only an appreciation of the content of these unusual organelles and the range of stimuli that can cause their exocytosis but also the influence of the external environment on organelle fusion and behavior of the secreted proteins. Here we examine the effect of extracellular acidification, a well documented consequence of inflammation or ischemia, on the dynamics of dispersal of soluble core and membrane proteins from individual WPB.

Differential Effect of Extracellular Acidification on the Dispersal of WPB Core Proteins—In contrast to the divergent fates of VWF and Proregion following WPB exocytosis at physiological pH (16, 17), fusion into acidic medium leads to their retention at the cell surface and failure of VWF to form filamentous strands. Here we show that this cell surface association occurs at between pHo 7.0 and 6.8, conditions somewhat less extreme than those reported by Vischer and Wagner (17) and more likely to be achieved during ischemia or inflammation. Proregion is now known to form a major structural component of the tubules observed in WPBs by electron microscopy (11). Formation of these tubules requires the acidic environment and high Ca2+ found within the trans-Golgi network, conditions that are sensed by the Proregion (11). Alkalinization of the WPB lumen following fusion at pHo 7.4 is detected by Proregion and translated into the rapid disassembly of the tubules (characterized by the collapse in shape of the organelle), and the separation and dispersal of Proregion and VWF with distinct kinetics (13, 16). Lowering pHo to 5.8 leads to the failure of WPB to collapse or release Proregion and VWF following stimulated fusion (supplemental Fig. S7), data that are consistent with the retention of Proregion and VWF within detergent-treated WPBs at pH 5.6 (15).

Thus, an important functional consequence of WPB fusion into medium of low pHo is that Proregion-VWF tubules fail to disassemble and release VWF. Instead VWF is retained in largely intact or partially collapsed tubules of Proregion and unable to deploy correctly to form filamentous strands, a process required for efficient platelet capture (15) and essential for its function in hemostasis (9, 31). Consistent with this, the ability of platelets to adhere to stimulated endothelium either at low pHo (32), or under conditions in which the structure of the WPB is disrupted by prior WPB alkalinization (15), is reduced. The effects of external pHo on Proregion and VWF behavior and function are unlikely to be restricted to the endothelial-derived proteins. Platelets also contain and secrete VWF and Proregion from α granules, where the VWF plays a role in promoting platelet-platelet and platelet-basement membrane interactions (33-35). Alterations in the behavior of these proteins during extracellular acidosis may account in part for defects in platelet aggregation reported to occur under such conditions (1, 4). The retention of Proregion at the cell surface may allow it to function as a ligand for integrin receptors on a number of different circulating cells involved in the regulation of inflammatory processes, although this is yet to be definitively established (see Introduction).

Intact or partially collapsed tubules of Proregion and VWF, formed following WPB fusion under acidic conditions, rapidly disassembled following re-perfusion of cells with medium at pHo 7.4 (Fig. 2B). Proregion dispersed rapidly (Fig. 2B), and globular deposits of VWFo were converted into long filamentous strands (supplemental Fig. S8). Thus a more pro-coagulant (potentially pro-thrombotic) phenotype of WPB fusion, partially masked under acidic conditions, is readily restored by a re-perfusion event.

Immunofluorescence, live cell imaging, and biochemical data show that release of small molecules, including IL-8 and eotaxin-3, is much less dependent on extracellular acidification. Although IL-8 is reported to bind, to some extent, to VWF in a pH-dependent fashion (little binding at pH 7.4, optimal binding at pH 6.2 and weaker binding as pH drops lower toward 5.5) this binding was seen in the presence of high [Ca2+], conditions that mimicked those thought to exist in the trans-Golgi network and mature WPB (36). Nonetheless the weak tendency to bind VWF may account for the small (compared with Proregion and VWF) reduction in IL-8 release seen at pHo 6.5 in biochemical experiments. The release and dispersal of IL-8 and eotaxin-3 under acidic conditions suggest that signaling to inflammatory cells will be retained. This, coupled with the inability of VWF to deploy correctly, may favor the regulation of local inflammatory processes at the expense of platelet capture and coagulant.

Extracellular Acidification and the Release of Membrane Proteins from WPB—The release of P-selectin from the WPB was slowed when fusion occurred into medium at pHo 6.5 and coincided with the failure of the WPB to collapse from a rod to a spherical structure (indicating that the tubules of proregion-VWF remain partially or completely intact). Our preliminary data indicate that P-selectin-EGFP is immobile within the membrane of mature intact WPB (37), possibly due to a specific interaction between the P-selectin extracellular domain and VWF (38). The slow exit of P-selectin from the WPB probably reflects interactions between P-selectin and partially collapsed or intact tubules of Proregion-VWF. The functional implications for leukocyte recruitment and activation, of a slow delivery of P-selectin to the membrane, are not clear; retaining P-selectin at sites of WPB fusion rich in other secreted inflammatory molecules may serve to prevent its rapid internalization prolonging its lifetime on the cell surface; however, this remains to be investigated.

The effect on extracellular acidification was specific for P-selectin; the behavior of CD63 was not affected. Our preliminary data indicate that CD63 is freely mobile within the membrane of mature WPB (37), suggesting that it does not interact strongly with the core of Proregion-VWF tubules. This could be because CD63, unlike P-selectin (39), is largely embedded within the plasma membrane extending only a few nanometers beyond the membrane boundary (28). As such, its behavior may be less influenced by structural changes in the core complex resulting from fusion events under different conditions.

Interpretation of Biochemical Assays of WPB Exocytosis following Stimulation under Conditions of Extracellular Acidosis—Exocytosis is commonly identified and quantified by the appearance in medium of soluble secreted factors, typically measured using biochemical methods such as ELISA. The correct interpretation of such data requires both an understanding of the influence of the specific experimental conditions on secretogogue-driven fusion of secretory organelles and how the soluble secreted proteins behave once released. This is illustrated in the experiments describe here. ELISA assays for secreted VWF or Proregion showed that stimulation of cells with ionomycin at pHo 6.5 resulted in a profound reduction (70-85%) in the appearance of soluble VWF and Proregion (Fig. 3). Taken at face value, this might suggest an inhibition of WPB exocytosis; however, direct optical studies showed that the kinetics and extent of WPB fusion evoked by this secretagogue are only slightly altered (supplemental Fig. S3). The reason for this discrepancy arises because these secreted proteins behave differently at the cell surface when released into either mildly alkaline or acidic medium (Fig. 1 and Ref. 17). Within the same biochemical experiments, it was found that the release of another type of WPB cargo molecule, IL-8, was much less strongly influenced by extracellular acidification (Fig. 3C). The situation would be even more complex to interpret in the case of the physiological agonist histamine where under acidic conditions there is a substantial change in the efficacy of this secretagogue (supplemental Fig. S1 and Ref. 13).

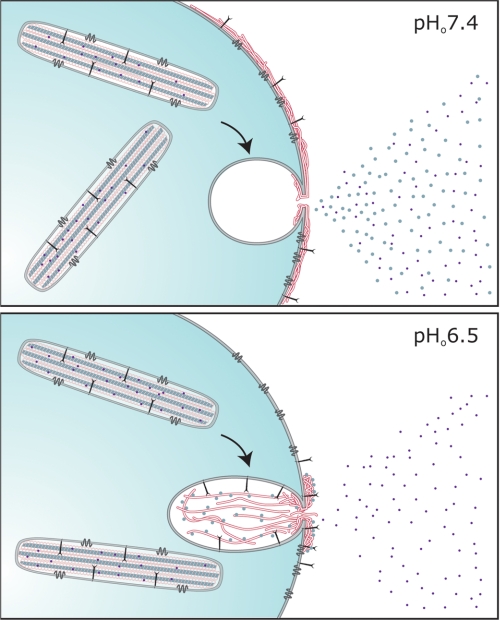

Changes in the kinetics and extent of secretogogue evoked secretory vesicle fusion, and the behavior of the secreted proteins themselves can depend on the local conditions in the extracellular environment. In many cases, the effects of specific environmental changes on these parameters cannot be predicted but have to be determined directly. Here we have shown that extracellular acidification, a condition reported to occur during inflammation or ischemia can differentially alter the dispersal of both soluble and membrane proteins released from the WPB. The inability of VWF to deploy correctly under acidic conditions, coupled with the efficient release of IL-8 and eotaxin-3, and slower release of P-selectin could subtly shift the secretory phenotype from a hemostatic to a more inflammatory mode (Fig. 7). Restoring pHo from 6.5 to 7.4 allows VWF to deploy into long filamentous strands required for efficient platelet capture.

FIGURE 7.

Influence of the external environment on the behavior of WPB cargo molecules during exocytosis. The scheme summarizes the behavior of WPB cargo molecules during exocytosis into external medium at approximately physiological pH (pHo 7.4; upper panel) and medium at pHo 6.5 (lower panel). The resting WPB is shown with CD63 (dark gray tetraspanin) and P-selectin (large linear single membrane-spanning protein) in the limiting membrane and a series of helical tubules comprising Proregion (light gray central tubule (11)) and VWF (white regions). Under normal conditions, pHo 7.4, VWF is released explosively (16) and forms long filamentous strands on the cell surface in response to fluid shear, Proregion (large gray circles) and small inflammatory molecules (small dark circles) diffuse into the bulk solution, and the membrane proteins CD63 and P-selectin are released efficiently. Under conditions reported to exist during inflammation or ischemia, pHo 6.5, VWF forms dense aggregates at the cell surface and no longer forms long filamentous strands on the cell surface in response to fluid shear, Proregion remains strongly associated with VWF and disperses very slowly, P-selectin is released more slowly while CD63 and small inflammatory molecules continue to be released efficiently.

Supplementary Material

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1-S8 and Movies S1 and S2.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: WPB, Weibel-Palade body; VWF, von Willebrand factor; PIPES, 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid; MES, 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IL, interleukin; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein.

L. J. Hewlett and M. J. Hannah, manuscript in preparation.

References

- 1.Foley, M. E., and McNicol, G. P. (1977) Lancet 1 1230-1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serrano, C. V., Jr., Fraticelli, A., Paniccia, R., Teti, A., Noble, B., Corda, S., Faraggiana, T., Ziegelstein, R. C., Zweier, J. L., and Capogrossi, M. C. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271 C962-C970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ihrcke, N. S., Parker, W., Reissner, K. J., and Platt, J. L. (1998) J. Cell. Physiol. 175 255-267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marumo, M., Suehiro, A., Kakishita, E., Groschner, K., and Wakabayashi, I. (2001) Thromb. Res. 104 353-360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng, Z. H., Wolberg, A. S., Monroe, D. M., 3rd, and Hoffman, M. (2003) J. Trauma 55 886-891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lardner, A. (2001) J. Leukoc. Biol. 69 522-530 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kellum, J. A., Song, M., and Li, J. (2004) Crit. Care 8 331-336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christou, H., Bailey, N., Kluger, M. S., Mitsialis, S. A., and Kourembanas, S. (2005) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288 H2647-H2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadler, J. E. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67 395-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner, D. D. (1990) Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 6 217-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang, R. H., Wang, Y., Roth, R., Yu, X., Purvis, A. R., Heuser, J. E., Egelman, E. H., and Sadler, J. E. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 482-487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rondaij, M. G., Bierings, R., Kragt, A., van Mourik, J. A., and Voorberg, J. (2006) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26 1002-1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erent, M., Meli, A., Moisoi, N., Babich, V., Hannah, M. J., Skehel, P., Knipe, L., Zupancic, G., Ogden, D., and Carter, T. D. (2007) J. Physiol. 583 195-212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Babich, V., Meli, A., Knipe, L., Dempster, J. E., Skehel, P., Hannah, M. J., and Carter, T. (2008) Blood 111 5282-5290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michaux, G., Abbitt, K. B., Collinson, L. M., Haberichter, S. L., Norman, K. E., and Cutler, D. F. (2006) Dev. Cell 10 223-232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannah, M. J., Skehel, P., Erent, M., Knipe, L., Ogden, D., and Carter, T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 22827-22830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vischer, U. M., and Wagner, D. D. (1994) Blood 83 3536-3544 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isobe, T., Hisaoka, T., Shimizu, A., Okuno, M., Aimoto, S., Takada, Y., Saito, Y., and Takagi, J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 8447-8453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi, H., Isobe, T., Horibe, S., Takagi, J., Yokosaki, Y., Sheppard, D., and Saito, Y. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 23589-23595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobus, W. E., Taylor, G. J. t., Hollis, D. P., and Nunnally, R. L. (1977) Nature 265 756-758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nemoto, E. M., and Frinak, S. (1981) Stroke 12 77-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson, R. M., Markle, D. R., Ro, Y. M., Goldstein, S. R., McGuire, D. A., Peterson, J. I., and Patterson, R. E. (1984) Am. J. Physiol. 246 H232-H238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagberg, H. (1985) Pflugers Arch. 404 342-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson, S. E., Lexmuller, K., Johansson, A., and Ekstrom, G. M. (1999) J. Rheumatol. 26 2018-2024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radhakrishnan, R., and Sluka, K. A. (2005) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313 921-927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodis, H. E., Poon, A., and Hargreaves, K. M. (2006) J. Dent. Res. 85 1046-1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borchiellini, A., Fijnvandraat, K., ten Cate, J. W., Pajkrt, D., van Deventer, S. J., Pasterkamp, G., Meijer-Huizinga, F., Zwart-Huinink, L., Voorberg, J., and van Mourik, J. A. (1996) Blood 88 2951-2958 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemler, M. E. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 801-811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zacharias, D. A., Violin, J. D., Newton, A. C., and Tsien, R. Y. (2002) Science (New York) 296 913-916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giblin, J. P., Hewlett, L. J., and Hannah, M. J. (2008) Blood 112 957-964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siedlecki, C. A., Lestini, B. J., Kottke-Marchant, K. K., Eppell, S. J., Wilson, D. L., and Marchant, R. E. (1996) Blood 88 2939-2950 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huck, V., Niemeyer, A., Goerge, T., Schnaeker, E. M., Ossig, R., Rogge, P., Schneider, M. F., Oberleithner, H., and Schneider, S. W. (2007) J. Cell. Physiol. 211 399-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fressinaud, E., Baruch, D., Rothschild, C., Baumgartner, H. R., and Meyer, D. (1987) Blood 70 1214-1217 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gralnick, H. R., Williams, S. B., McKeown, L. P., Magruder, L., Hansmann, K., Vail, M., and Parker, R. I. (1991) Mayo Clin. Proc. 66 634-640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zucker, M. B., Broekman, M. J., and Kaplan, K. L. (1979) J. Lab. Clin. Med. 94 675-682 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bierings, R., van den Biggelaar, M., Kragt, A., Mertens, K., Voorberg, J., and van Mourik, J. A. (2007) J. Thromb. Haemost. 5 2512-2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiskin, N. I., Mashanov, G. I., Hewlett, L. J., Knipe, L., Skehel, P. A., Molloy, J. E., Hannah, M. J., and Carter, T. C. (2004) Biophys. J. 88 264A-265A [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michaux, G., Pullen, T. J., Haberichter, S. L., and Cutler, D. F. (2006) Blood 107 3922-3924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ushiyama, S., Laue, T. M., Moore, K. L., Erickson, H. P., and McEver, R. P. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268 15229-15237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.