Abstract

Objective To determine the incidence of cervical cancer after several negative cervical smear tests at different ages.

Design Prospective observational study of incidence of cervical cancer after the third consecutive negative result based on individual level data in a national registry of histopathology and cytopathology (PALGA).

Setting Netherlands, national data.

Population 218 847 women aged 45-54 and 445 382 aged 30-44 at the time of the third negative smear test.

Main outcome measures 10 year cumulative incidence of interval cervical cancer.

Results 105 women developed cervical cancer within 2 595 964 woman years at risk after the third negative result at age 30-44 and 42 within 1 278 532 woman years at risk after age 45-54. During follow-up, both age groups had similar levels of screening. After 10 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidence rate of cervical cancer was similar: 41/100 000 (95% confidence interval 33 to 51) in the younger group and 36/100 000 (24 to 52) in the older group (P=0.48). The cumulative incidence rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I+ was twice as high in the younger than in the older group (P<0.001).

Conclusions The risk for cervical cancer after several negative smear results by age 50 is similar to the risk at younger ages. Even after several negative smear results, age is not a good discriminative factor for early cessation of cervical cancer screening.

Introduction

The debate on early cessation of cervical cancer screening for women with several consecutive negative smear results and no abnormalities by age 50 has been ongoing for about 15 years, with no clear conclusions in terms of a change to guideline for these women. Several authors have studied this issue by analysing the detection rates of preinvasive cervical lesions in these women.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 In general, they observed considerably lower detection rates than in similarly screened younger women. On the basis of this finding they argued that continued screening in this particular group of women is not as efficient as screening among younger women and could be stopped at the expense of only a limited increase in the incidence of cervical cancer among these older women.2 4 6 9 This could result in considerable savings for the screening programmes. In the Netherlands, for example, it would apply to about half of the women attending screening around age 50.10

Because there is strong evidence that cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions have a higher probability to progress to invasive cancer at older ages,11 12 a lower detection rate after age 50 alone does not represent conclusive evidence for lower screening efficiency. Data on invasive cancer have since become available in a Dutch nationwide pathology registry with screening histories linked to diagnostic histological outcomes (including cancer) at the individual level. We measured the incidence of invasive cancer after several consecutive negative smear results in women around age 50 and in younger women. This bypasses the problems associated with using cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions and enables a more conclusive evaluation of whether there is more reason to relax screening in older than in younger women with similar negative screening histories.

Methods

Data

From the Dutch nationwide network and registry of histopathology and cytopathology (PALGA), we retrieved information on all cervix uteri cytological and histological tests until 31 March 2004. In principle, all pathology laboratories in the Netherlands participate in this computerised system. The registration began in the late 1970s and achieved practically complete coverage of pathology laboratories in 1990.13 The network registers smears and biopsies taken in all settings: primary smears within the screening programme, opportunistic screening, or because of medical complaints, and secondary (diagnostic and follow-up) tests, regardless of whether they are taken or read by public or private healthcare providers and laboratories. The retrieved file contained data for all but one pathology laboratory, accounting for less than 1% of smears taken yearly. In the Netherlands, cervical cancer screening became widespread after an extensive pilot project that started in 1976. Around 1980, the programme inviting women aged 35-53 with a three year interval reached almost national coverage. A considerable amount of opportunistic screening in young women coexisted next to the organised programme,14 and the programme was reorganised in 1996. Women are now invited once every five years between ages 30 and 60.15 In 2003, 77% of women at risk (that is, those with a cervix) in this age group had had at least one smear in the preceding five years.16 The most commonly used screening tool is a conventional Pap smear, although the share of liquid based cytology smears is increasing.

In the network, women are identified through their birth date and the first four letters of their (maiden) family name. This identification code enabled linkage of the tests belonging to the same woman, allowing us to follow the individual screening and disease histories. Because this code is not always unique, it introduces an upward bias in the incidence after a negative screen. To avoid this bias, we excluded women with 0.5% of the most common first four letters of the family name—that is, about 30% of women. The cut-off point of 0.5% was chosen because we observed that the incidence of cervical cancer after a negative result stabilised around this point.17 An independent analysis comparing the network data with a regional dataset with virtually no incorrect matches of the identification code showed that this was an adequate method of avoiding the problem of incorrect identification matches.18

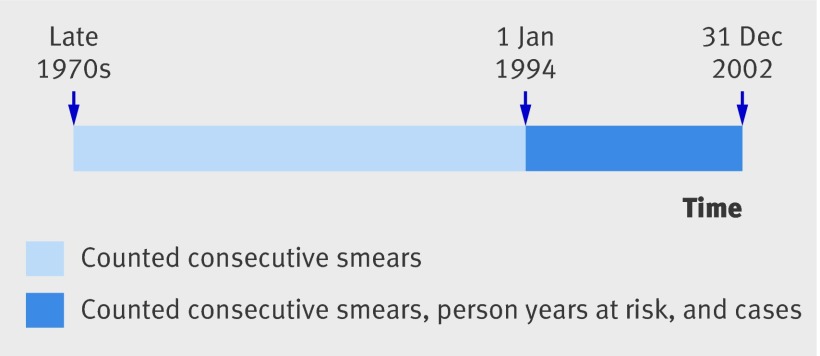

Final diagnoses for all non-cancer excerpts (that is, all cytology and all non-cancer biopsies) in the retrieved network file were based on the network’s SNOMED (systemised nomenclature of medicine) oriented codes. In contrast, we identified cases of cervical cancer by (manually) checking the free text of the pathology reports for all excerpts that included SNOMED-oriented codes for cervical cancer for the period 1994-2002. The follow-up (person years at risk and cases) in the present analysis was therefore left censored at the beginning of 1994 and right censored at the end of 2002. Figure 1 shows a schematic presentation of the study.

Fig 1 Schematic presentation of study. Consecutive primary smears counted throughout entire period covered by PALGA system (from late 1970s onwards), whereas person years at risk and cases counted from 1 January 1994 to 31 December 2002. Person years and cases accrued before 1 January 1994 excluded from analysis (left censoring)

Statistical analysis

We selected women in two age groups, 45-54 (“the older group”) and 30-44 (“the younger group”) and included them if they had a third consecutive negative primary smear result in this age interval at any time since the beginning of the registration. Women with previous histological (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I+) or cytological (borderline dyskaryosis or worse) abnormalities were excluded. Women were followed up from the date of the third negative smear until the date of the first diagnosis of cervical cancer or until the end of 2002. We could not censor the follow-up in case of death from other causes because we had no information on the time of death. However, we estimate that the potential impact on our results was small because the mortality rate in women in the Netherlands below age 65 is low (below 1% per year since the 1980s).19

For both age groups, we first calculated the cumulative incidence rate of cervical cancer in the period 1994-2002 by time since the third negative result. Because for most women (about 85% in the older group and 80% in the younger group) a maximum of 10 years of follow-up was available, we focused on the cumulative incidence rate during these first 10 years. We tested the difference in the cumulative incidence rate between the age groups for significance assuming a Poisson distribution for the number of women with cancer—that is, cases (null hypothesis: no difference in the cumulative incidence rate between the age groups). We estimated the 95% confidence intervals using the non-parametric Kaplan-Meier product limit estimator for log(hazard).20 We tested the difference in the incidence rates between the two age groups during the whole follow-up period (the hazard rate) by Cox regression with left and right censoring. Time dependency of relative hazards was tested by splitting the total follow-up time in two periods with a roughly equal number of cases.

Results

We identified 218 847 women in the older group and 445 382 in the younger group who met our inclusion criteria (table 1). The average interval between the three consecutive negative results (that is, between the first and the second, and the second and the third smear) was 40 months in the older group and 39 months in the younger group, reflecting the fact that women could accumulate the three registered negative smears either in about the 20 years before 1996, when recommendations tried to limit screening to once in three years, or in the seven years since 1996 to 2002, with the recommendation of one smear per five years. In the period between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2002, 1.3 and 2.6 million person years in follow-up accrued in these groups, respectively, an average of 5.84 and 5.83 years per woman (table 2). The two groups had a similar rate of screening after the third negative smear (table 3): about a third had none, about a third had one, and the remaining third had more than one further primary test registered. Forty two women in the older group and 105 women in the younger group developed cervical cancer (table 2).

Table 1.

Description of study population by five year age groups

| Age 30-44 at entry | Age 45-54 at entry | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 | 45-49 | 50-54 | ||

| No of women | 126 748 | 156 435 | 162 199 | 124 254 | 94 593 | |

| CIR† | 36 (23 to 58) | 39 (26 to 59) | 45 (32 to 61) | 38 (22 to 66) | 33 (21 to 53) | |

†Cumulative incidence rate (95% CI) per 100 000 women at 10 years after third consecutive negative smear result.

Table 2.

Incidence of invasive cervical cancer after third consecutive negative smear result for two age groups

| Time (years) since third negative smear | Age (years) at entry | P value‡ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-44 | 45-54 | |||||||

| Woman years* | Women with invasive cancer | Cumulative incidence rate† (95% CI) | Woman years* | Women with invasive cancer | Cumulative incidence rate† (95% CI) | |||

| ≤1 | 324 512 | 4 | 1 (0 to 3) | 172 920 | 3 | 2 (1 to 5) | 0.66 | |

| >1-≤3 | 628 471 | 16 | 6 (4 to 10) | 344 825 | 16 | 11 (7 to 17) | 0.09 | |

| >3-≤5 | 563 725 | 27 | 16 (12 to 21) | 304 194 | 5 | 14 (10 to 21) | 0.65 | |

| >5-≤10 | 837 359 | 43 | 41 (33 to 51) | 378 075 | 13 | 36 (24 to 52) | 0.48 | |

| >10-≤15 | 200 225 | 11 | 70 (51 to 95) | 65 373 | 4 | 73 (39 to 135) | 0.85 | |

| >15−≤20 | 41 672 | 4 | 128 (79 to 207) | 13 145 | 1 | 105 (50 to 219) | 0.27 | |

| Total | 2 595 964 | 105 | — | 1 278 532 | 42 | — | — | |

*Accrued between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2002.

†At end point of interval, per 100 000 women.

‡Two sided, for difference in rate between two age groups at specific time points.

Table 3.

Percentage of primary screening tests after third consecutive negative smear result*

| No of tests | Age (years) at entry | |

|---|---|---|

| 30-44 | 45-54 | |

| 0 | 35 | 35 |

| 1 | 27 | 33 |

| 2 | 18 | 18 |

| 3 | 10 | 8 |

| ≥4 | 10 | 7 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

*Average number of years at risk for further smears after third negative smear was 6.7 and 6.4 among women aged 30-44 and 45-45, respectively.

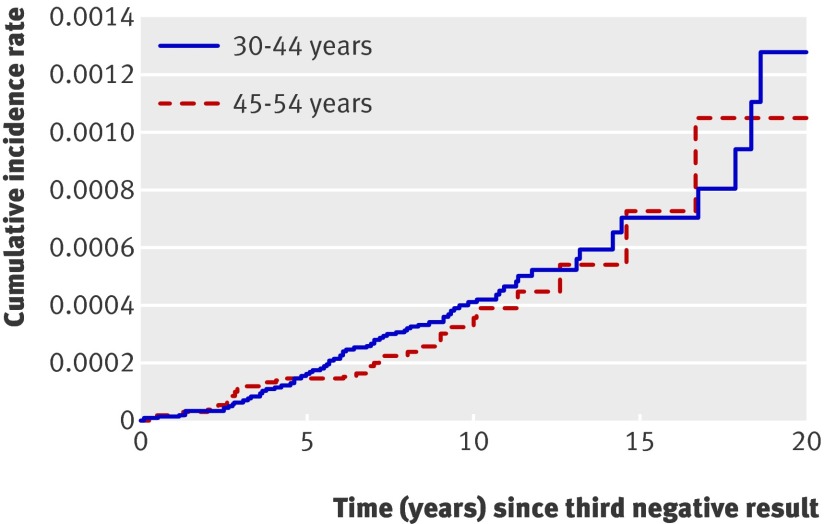

During follow-up, the difference in the cumulative incidence rate between the age groups was never significant (fig 2 and table 2) . Table 4 shows the average absolute yearly incidence rates.

Fig 2 Cumulative incidence rate for invasive cancer by age group and time since third consecutive negative smear result

Table 4.

Incidence rates per 100 000 woman years at risk (95% CI) by age group and year in follow-up

| Time (years) since third negative smear | Age (years) at entry | |

|---|---|---|

| 30-44 | 45-54 | |

| ≤1 | 1.23 (0.46 to 3.28) | 1.74 (0.56 to 5.39) |

| >1-≤2 | 0.94 (0.30 to 2.91) | 1.15 (0.29 to 4.59) |

| >2-≤3 | 3.87 (2.20 to 6.81) | 8.18 (4.84 to 13.81) |

| >3-≤5 | 4.76 (3.26 to 6.94) | 1.63 (0.68 to 3.91) |

| >5-≤7 | 5.58 (3.77 to 8.26) | 1.84 (0.69 to 4.90) |

| >7-≤9 | 3.97 (2.26 to 6.99) | 4.60 (2.07 to 10.24) |

| >9-≤11 | 6.26 (3.47 to 11.30) | 6.20 (2.33 to 16.51) |

| >11-≤13 | 3.40 (1.10 to 10.55) | 6.97 (1.74 to 27.88) |

| >13-≤15 | 9.20 (3.45 to 24.52) | 7.74 (1.09 to 53.49) |

| >15-≤20 | 9.31 (3.49 to 24.80) | 7.39 (1.04 to 52.43) |

The average age of women was 37.3 years in the younger group and 48.7 years in the older group. Pooling women into two large age groups does not seem to have affected this result, as the cumulative incidence rate for cervical cancer at 10 years in smaller five year age groups also did not differ significantly (table 1, P=0.24).

The overall hazard ratio was 0.84 (95% confidence interval 0.59 to 1.21) for the older compared with the younger group. The test for time dependency of the relative hazards was non-significant (P=0.86).

We also varied the criterion for study eligibility from requiring three to requiring either two or four consecutive negative results. This changed the absolute level of risk but not the relation between the two age groups. After two consecutive negative results, the 10 year cumulative incidence rate for cancer was 45/100 000 (39 to 52) in the younger group and 48/100 000 (38 to 61) in the older group. Within 10 years after four consecutive negative smears, the cumulative incidence rate in the younger group was 47/100 000 (34 to 65), whereas in the older group it was 26/100 000 (14 to 47). By 15 years, however, the cumulative incidence rate after four consecutive negative smears in the older group caught up with that in the younger group (74/100 000 (45 to 121) in the younger group and 82/100 000 (26 to 257) in the older group).

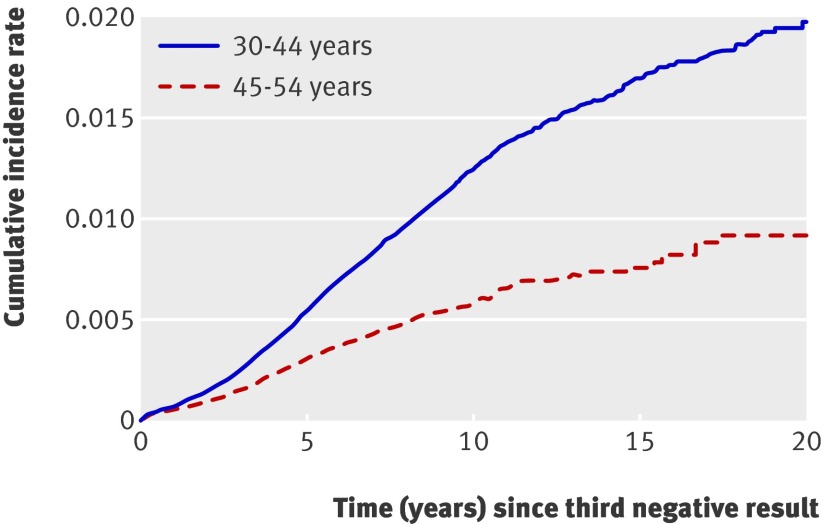

We also calculated the cumulative incidence rate with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I+ as the end point (table 5, fig 3) . By 10 years, the cumulative incidence rate was 1258/100 000 (1209 to 1308) in the younger group and 594/100 000 (547 to 645) in the older group. The difference between both groups was significant throughout the entire follow-up. Use of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II+ or grade III+ as the end point instead of grade I+ also showed that preinvasive lesions are more commonly detected in the younger groups. The cumulative incidence rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade II+ was 721/100 000 (684 to 759) among younger and 258/100 000 (227 to 293) among older women. The cumulative incidence rate of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade III+ was 445/100 000 (417 to 476) among younger and 165/100,000 (140 to 194) among older women.

Fig 3 Cumulative incidence rate for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I+ (CIN I+) by age group and time since third consecutive negative smear result

Table 5.

Incidence of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia I+ (CIN I+) after third consecutive negative smear result for two age groups

| Time (years) since third negative smear | Age (years) at entry | P value‡ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-44 | 45-54 | |||||||

| Woman years* | Women with CIN I+ | Cumulative incidence rate† (95% CI) | Woman years* | Women with CIN I+ | Cumulative incidence rate† (95% CI) | |||

| ≤1 | 324 381 | 233 | 72 (63 to 82) | 172 850 | 90 | 52 (42 to 64) | 0.008 | |

| >1-≤3 | 627 524 | 584 | 258 (241 to 277) | 344 441 | 172 | 152 (135 to 172) | <0.001 | |

| >3-≤5 | 561 412 | 834 | 555 (529 to 583) | 303 363 | 240 | 310 (284 to 339) | <0.001 | |

| >5-≤10 | 829 336 | 1192 | 1258 (1209 to 1308) | 375 786 | 224 | 594 (547 to 645) | <0.001 | |

| >10-≤15 | 196 753 | 197 | 1707 (1622 to 1796) | 64 635 | 30 | 769 (686 to 862) | <0.001 | |

| >15−≤20 | 40 898 | 24 | 1986 (1841 to 2143) | 12 995 | 5 | 920 (772 to 1096) | <0.001 | |

| Total | 2 580 304 | 3064 | — | 1 274 070 | 761 | — | — | |

*Accrued between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 2002.

†At end point of interval, per 100 000 women.

‡Two sided for difference in rate between two age groups at specific time points.

Discussion

The relative risk of developing cervical cancer after a third consecutive negative smear result among women around age 50 did not differ significantly from the risk in younger women. This outcome was not biased by differential screening during follow-up because there was no difference between the age groups in this respect. Evidence available in the literature does not show that either the differential screening sensitivity for high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or the differential effectiveness of treatment of screen detected cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, in the context of the overall highly successful treatment and a decreasing detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with increasing age, differ between these two age groups to such a degree that they would bias our conclusions.21 22 23 24 25 26 Therefore it is reasonable to assume that after several consecutive negative results the screening efficiency in terms of detection and prevention of cervical cancer is at the same level around age 50 as it is at younger ages.

In the analysed age groups (30-54 years), the incidence rate of cervical cancer in the general population was between 10 and 14 per 100 000 woman years in the period 2001-5.27 These rates are a reflection of different screening histories including those of well screened women included in our analysis, where the latter tend to decrease the general population incidence rates. Whether the relatively low incidence rates observed in both our study groups warrant continued screening should thus be determined by subsequent analyses.

We observed a lower risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades I+, II+, and III+ in the older group. In this respect, our results are consistent with those of others,2 4 6 and confirm that cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is not an accurate intermediate end point for the question addressed.

Because we included women as soon as they had the third consecutive negative result, younger women will on average have been screened more intensely at a younger age than women included in the older group; the older women might therefore be at higher risk. The selection criterion of being disease free on three consecutive screenings, however, and the finding that the screening attendance after the third negative result was similar in both groups make such a bias unlikely. We tested this in an additional analysis in which we included women from the younger group in the older group if they continued to have negative smears after age 44. The result was the same: in the older group the 10 year cumulative incidence rate slightly decreased from 36 (24 to 52) to 34 (25 to 48) per 100 000.

We selected women with negative screening histories—that is, women who had never had cytological or histological evidence of neoplasia. In everyday practice, complete screening histories might not always be known and might contain abnormalities. Women with previous abnormalities—that is, at least abnormal cytology—remain at higher risk for invasive cancer, despite later consecutive negative smear results.28 In our data, inclusion of women with screen detected abnormalities followed by three consecutive primary negative results did not affect the two age groups differently: the cumulative incidence rate at 10 years was 42 (30 to 57)/100 000 in the older group and 42 (34 to 51)/100 000 in the younger group.

Implications of the study

The similarity in the cumulative incidence rate between the two age groups is not unexpected given the observed age specific incidence before screening became widespread29 (that is, before about 1970 in most developed countries). In the Netherlands, as well as in several western European countries, the incidence before screening rose rapidly to a peak around ages 44-49 and declined thereafter. Thus, when women in the 30-44 year group (average age about 37) are ageing, they proceed from a lower to a higher risk age. The opposite is true for women in the 45-54 year group (average age about 50). This translates into roughly equal levels of cumulative incidence rate for cancer during the first 10 years for the two age groups (that is, from age 37 to 47, and from 50 to 60 years, respectively).29 In some other countries, like the United Kingdom and the United States, the decline in the incidence before screening at older ages is slower. If this pattern is because of a real different age effect and not a cohort effect, the relative reduction in incidence of cancer gained through continued screening in the older group would be even higher than in the Netherlands.

The question of age specific screening efficiency can be further explored by comparing the average number of life years lost per extra incident case if screening had been discontinued after three negative smear results. Younger women have a longer remaining life expectancy than older women, but they also have lower death rates from cervical cancer. The life expectancy of women in the Netherlands is 42, 33, and 24 years at ages 40, 50, and 60, respectively,30 while the five year mortality rate from clinical cervical cancer (approximated by stage IIB+) increases from about 45% to 70% and 70-75%, respectively, at the same ages.31 Assuming that the five year mortality rates approximate the total death, around 20 years are lost per incident case in the absence of screening for all three ages, which means that decreasing life expectancy and the increasing cancer death compensate each other. At even older ages, however, the number of life years lost per incident case starts to decrease.

Our data do not permit a simple extension of our study to older ages. For example, in 79 586 women satisfying the criteria at ages 55-64, the 10 year cumulative incidence rate was 47/100 000 (23 to 99) and was statistically comparable with that in women below age 55. Women aged 55-64 years, however, had a considerably lower screening intensity after the third negative result: 60% had no further smear compared with 35% in women below age 55. In women above 64, screening intensity decreases even further. This diminishes the actual comparability of women aged 55 or older with women below that age, and, as a consequence, we cannot draw clear conclusions on the relative screening efficiency for this age group.

The continued risk for cervical cancer is consistent with the considerable rate of (apparently) incident human papillomavirus (HPV) infections throughout the age span we focused on.32 33 As it is the screen detected cervical intraepithelial neoplasia rather than an HPV infection that can be treated, HPV screening instead of cytological screening could eliminate relatively few extra HPV infections before the age of 50. In case of HPV screening, our conclusions would therefore remain the same. This would also mean that the HPV vaccine might succeed in attaining its full potential of eradicating up to 70% of cervical cancer only if it offers protection from a persistent HPV infection for many decades—that is, also after age 50. This again will depend strongly on the (unknown) proportion of infections at age 50 and over that are caused by reactivated latent infections acquired earlier in life.34 35

From the UK data on the timing of screening smears before the (pseudo-) diagnosis of cervical cancer in cases and controls, Sasieni et al showed that the protection a negative smear offers to younger women (age 20-39) is lower than among women aged 40 or older.36 As a consequence, they advocated shorter screening intervals for younger than for older women. The differences in our results are consistent with two important differences between studies. Firstly, in the UK data older women had probably accumulated more screening tests before the analysed negative smear than younger women. A lower number of earlier smears tends to increase the subsequent incidence of cervical cancer. In our analysis, women had similar screening histories (three consecutive negative results before the beginning of follow-up). Secondly, the increase in the risk for cervical cancer among younger British cohorts might have played a role.37 No such increase has been observed in the Netherlands.38

Conclusions

By being able to use invasive cancer as the relevant end point, our analysis gives a more evidence based answer to the ongoing discussion on continued screening in women with several negative smear results by age 50. It showed that it would not be consistent to stop screening these women while not also relaxing the screening policy for younger women with similar screening histories. In this respect, our conclusion lends support to the current cervical cancer screening guidelines in England and other developed countries,36 39 40 41 42 which do not discriminate women by age up to 60-65.

Whether individual tailoring of recommendations for further screening by using the information on individual screening histories would be an efficient and feasible alternative to the current fixed schedule in any age group remains to be explored.

What is already known on this topic

The detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in adequately screened women with several consecutive negative smear results by age 50 is considerably lower than among younger similarly screened women

The probability of progression of a cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesion to cervical cancer increases by age

What this study adds

The risk for cervical cancer after several negative smear results by age 50 is similar to that at younger ages

It is therefore not consistent to stop screening women with several consecutive negative smears after age 50

Contributors: MvB, EL, DH, and MR designed the study. MvB and MR collected the data. MR and CL analysed the data. MR, MvB, and DH wrote the manuscript, which was critically revised by EL, CL, M-LE-B, and RB. All authors interpreted the data and decided to submit the manuscript for publication. MR and MvB are guarantors.

Funding: This study was financed by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM, grant No 3022/07 DG MS/CvB/NvN). The authors wrote the manuscript independent of the funder. The RIVM had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: The department of public health of the Erasmus MC received a grant from GSK, a manufacturer of an HPV vaccine, for research on the cost effectiveness of HPV vaccination in 2007 and 2008. This research and manuscript were neither funded nor supported by GSK. RB has been participating since 1989 in the screening research group at the department. He has been affiliated with RAND since 2000. Since 2007, he has been a director of evidence based strategies-disease modelling and economic evaluation at Pfizer, who develop and sell various drugs for cancer and other diseases. This research and manuscript were neither funded nor supported by Pfizer.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b1354

References

- 1.Baay MF, Smits E, Tjalma WA, Lardon F, Weyler J, Van Royen P, et al. Can cervical cancer screening be stopped at 50? The prevalence of HPV in elderly women. Int J Cancer 2004;108:258-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruickshank ME, Angus V, Kelly M, McPhee S, Kitchener HC. The case for stopping cervical screening at age 50. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:586-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flannelly G, Monaghan J, Cruickshank M, Duncan I, Johnson J, Jordan J, et al. Cervical screening in women over the age of 50: results of a population-based multicentre study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2004;111:362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafsson L, Sparen P, Gustafsson M, Pettersson B, Wilander E, Bergstrom R, et al. Low efficiency of cytologic screening for cancer in situ of the cervix in older women. Int J Cancer 1995;63:804-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogilvie D. Early discharge of low-risk women from cervical screening. J Public Health Med 2001;23:272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Wijngaarden WJ, Duncan ID. Rationale for stopping cervical screening in women over 50. BMJ 1993;306:967-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Pettinger M, Johnson SR, Hubbell FA, Lane DS, et al. Incidence of cervical cytological abnormalities with aging in the women’s health initiative: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:410-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawaya GF, Kerlikowske K, Lee NC, Gildengorin G, Washington AE. Frequency of cervical smear abnormalities within 3 years of normal cytology. Obstet Gynecol 2000;96:219-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Wijngaarden WJ, Duncan ID. Upper age limit for cervical screening. BMJ 1993;306: 1409-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Dutch Network and National Database for Pathology (PALGA). Results of retrieval action of cervix uteri tests until 31-03-2007. Utrecht: Prismant, 2007.

- 11.Van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JD. Epidemiological evidence for age-dependent regression of pre-invasive cervical cancer. Br J Cancer 1991;64:559-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCredie MRE, Sharples KJ, Paul C, Baranyai J, Medley G, Jones RW, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2008;9:425-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PALGA. Description of the PALGA system and computer network. (In Dutch.) Utrecht, Netherlands: PALGA, 2004. www.palga.nl0

- 14.Van Ballegooijen M. Effects and costs of cervical cancer screening. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Department of Public Health, Erasmus University, 1998.

- 15.National Health Insurance Council. Starting points for the restructuring of the organised cervical cancer screening programme. Final decision. (In Dutch.) Amstelveen, Netherlands: ZiekenfondsRaad, 1993.

- 16.Rebolj M, van Ballegooijen M, Berkers LM, Habbema D. Monitoring a national cancer prevention program: successful changes in cervical cancer screening in the Netherlands. Int J Cancer 2007;1206:806-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akker-van Marle MEvd, van Ballegooijen M, Habbema JD. Low risk of cervical cancer during a long period after negative screening in the Netherlands. Br J Cancer 2003;88:1054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rebolj M. Recent developments in the Dutch cervical cancer screening programme (thesis). Rotterdam: Department of Public Health, Erasmus MC, 2008.

- 19.Central Bureau of Statistics. Survival tables per sex and age. (In Dutch.) Voorburg/Heerlen, Netherlands: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2008. http://statline.cbs.nl

- 20.Harrell FE. Regression modelling strategies. With applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer, 2001.

- 21.Flannelly G, Bolger B, Fawzi H, De Lopes AB, Monaghan JM. Follow up after LLETZ: could schedules be modified according to risk of recurrence? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2001;108:1025-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koliopoulos G, Arbyn M, Martin-Hirsch P, Kyrgiou M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Diagnostic accuracy of human papillomavirus testing in primary cervical screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis of non-randomized studies. Gynecol Oncol 2007;104:232-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchell H, Hocking J. Influences on the risk of recurrent high grade cervical abnormality. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2002;12:728-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettersson F, Malker B. Invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix following diagnosis and treatment of in situ carcinoma. Record linkage study within a National Cancer Registry. Radiother Oncol 1989;16:115-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soutter WP, de Barros Lopes A, Fletcher A, Monaghan JM, Duncan ID, Paraskevaidis E, et al. Invasive cervical cancer after conservative therapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Lancet 1997;349:978-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dillner J, Rebolj M, Birembaut P, Petry KU, Szarewski A, Munk C, et al. Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutch Comprehensive Cancer Centres. Cancer registry online: core indicators. www.ikcnet.nl

- 28.Coldman A, Phillips N, Kan L, Matisic J, Benedet L, Towers L. Risk of invasive cervical cancer after Pap smears: the protective effect of multiple negatives. J Med Screen 2005;12:7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gustafsson L, Ponten J, Bergstrom R, Adami HO. International incidence rates of invasive cervical cancer before cytological screening. Int J Cancer 1997;71:159-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Central Bureau of Statistics. Mortality, causes of death and euthanasia: life expectancy in years per sex in 2005. (In Dutch.) Voorburg/Heerlen, Netherlands: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2007. http://statline.cbs.nl.

- 31.Rijke de JM, van der Putten HW, Lutgens LC, Voogd AC, Kruitwagen RF, van Dijck JA, et al. Age-specific differences in treatment and survival of patients with cervical cancer in the southeast of The Netherlands, 1986-1996. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:2041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Syrjanen S, Shabalova I, Petrovichev N, Podistov J, Ivanchenko O, Zakharenko S, et al. Age-specific incidence and clearance of high-risk human papillomavirus infections in women in the former Soviet Union. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:217-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grainge MJ, Seth R, Guo L, Neal KR, Coupland C, Vryenhoef P, et al. Cervical human papillomavirus screening among older women. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;11:1680-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trottier H, Franco EL. The epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Vaccine 2006;24(suppl 1):S1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moscicki AB, Palefsky J, Smith G, Siboshski S, Schoolnik G. Variability of human papillomavirus DNA testing in a longitudinal cohort of young women. Obstet Gynecol 1993;82:578-85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasieni P, Adams J, Cuzick J. Benefit of cervical screening at different ages: evidence from the UK audit of screening histories. Br J Cancer 2003;89:88-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cook GA, Draper GJ. Trends in cervical cancer and carcinoma in situ in Great Britain. Br J Cancer 1984;50:367-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van der Aa MA, de Kok IM, Siesling S, van Ballegooijen M, Coebergh JW. Does lowering the screening age for cervical cancer in The Netherlands make sense? Int J Cancer 2008;123:1403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anttila A, Ronco G, Clifford G, Bray F, Hakama M, Arbyn M, et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and policies in 18 European countries. Br J Cancer 2004;91:935-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hawkes AP, Kronenberger CB, MacKenzie TD, Mardis AL, Palen TE, Schulter WW, et al. Cervical cancer screening: American College of Preventive Medicine practice policy statement. Am J Prev Med 1996;12:342-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 2006;56:11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer—recommendations and rationale. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/cervcan/cervcanrr.htm.