Abstract

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) is an essential cytokine for T-lymphocyte homeostasis. We have previously reported that all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) enhances the secretion of IL-2 from human peripheral blood T cells in vitro, followed by increased proliferation and inhibition of spontaneous cell death. In this study we used a transgenic IL-2 gene luciferase reporter model to examine the effects of atRA in vivo. In contrast to the observations in human T cells, we found an overall reduction in luciferase-reported IL-2 gene expression in mice treated with atRA. Whole-body luminescence of anti-CD3-treated and non-treated mice was reduced in mice receiving atRA. Accordingly, after 7 hr, IL-2 gene expression was on average 55% lower in the atRA-treated mice compared with the control mice. Furthermore, mice fed a vitamin A-deficient diet had a significantly higher basal level of luciferase activity compared with control mice, demonstrating that vitamin A modulates IL-2 gene expression in vivo. Importantly, the atRA-mediated inhibition of IL-2 gene expression was accompanied by decreased DNA synthesis in murine T cells, suggesting a physiological relevance of the reduced IL-2 gene expression observed in transgenic reporter mice.

Keywords: cytokines, mouse, spleen/lymphnodes, T cells

Introduction

Interleukin-2 (IL-2) is primarily produced by T cells, and this cytokine is central for the activation of T and B lymphocytes and natural killer cells.1,2 The IL-2 propagates the immune response, and can terminate it by promoting activation-induced cell death of T cells.3,4 Moreover, activated T cells deprived of IL-2 undergo spontaneous apoptosis, termed activated T-cell autonomous death.5 In recent years, IL-2 has also been ascribed a fundamental role in regulatory T-cell homeostasis.6

An estimated 250 million preschool children worldwide are vitamin A deficient,7 and the deficiency state is associated with impaired vision, retarded growth and impaired adaptive and innate immune responses.8,9 Clinical trials have shown that vitamin A supplementation reduces morbidity and mortality from various infectious diseases, including measles, measles-related pneumonia, diarrhoea, human immunodeficiency virus infection and malaria,10 and numerous studies in animal models have confirmed the ability of vitamin A to prevent infections and to strengthen the immune system.9,11,12 The majority of the effects of vitamin A are mediated by all-trans retinoic acid (atRA), which acts as a ligand for the transcription factors: the retinoic acid receptors (RARs).13 The RARs, in co-operation with their heterodimeric partners retinoid X receptors, activate gene expression through binding to their cognate DNA element in the regulatory region of target genes.13

We have previously shown that atRA promotes proliferation and inhibits spontaneous cell death of activated human peripheral blood T lymphocytes in vitro.14,15 The atRA induced potent stimulation of IL-2 secretion from T cells, and both the proliferative and death-inhibiting effects of atRA were shown to be dependent on enhanced IL-2 secretion.14,15 Studies performed in vivo have demonstrated different effects of vitamin A on IL-2 secretion. Whereas Wiedermann and co-workers demonstrated enhanced IL-2 secretion from spleen cells of vitamin A-deficient rats,16,17 other studies have shown reduced or non-affected secretion of IL-2 in vitamin-A-deficient animals.18–22

To determine whether the stimulating effect of atRA on IL-2 production and proliferation of human T cells was evident in an in vivo situation, we took advantage of a recently generated IL-2 gene luciferase reporter model. This commercially available transgenic mouse strain carries 10·7 kilobases (kb) of the murine IL-2 gene promoter/enhancer region in front of a modified firefly luciferase complementary DNA (cDNA; Caliper Life Sciences, Alameda, CA) which enables real-time non-invasive molecular imaging of IL-2 gene expression in intact animals.

Here we show that in contrast to human T cells in vitro, IL-2 gene expression in vivo was inhibited in mice receiving atRA. In accordance, vitamin A-deficient mice exhibited increased basal IL-2 gene expression. The effect of atRA on murine T cells was also confirmed in vitro, indicating a different effect of atRA on IL-2 gene expression in murine and human T cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

The atRA was purchased from Fluka Biochimica (Buchs, Switzerland). Corn oil was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, MO). For in vivo studies mice were administered a high dose of atRA (50 mg/kg body weight) suspended in corn oil 23 or vehicle control (corn oil) by gavage feeding. The mice received a total volume of 300 μl. Purified hamster anti-mouse CD3ε monoclonal antibody (anti-CD3), isotype control and anti-mouse CD28 antibody (anti-CD28) were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA). Both 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) and ionomycin were purchased from Sigma.

Mice

The mice were kept under conditions in compliance with the rules and guidelines from the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations, and the study was reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority. The IL-2 reporter mice used in this study were from Caliper Life Sciences, and carried a transgene containing 10·7 kb from the murine IL-2 promoter/enhancer region, a human β-globin intron 2, modified firefly luciferase cDNA and a 0·28-kb 3′ end untranslated region of the IL-2 gene. The background strain of these mice is CD1, and the coat colour is albino. Only female mice between the ages of 2 and 6 months were used. For assessment of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity in vitro, cells from transgenic reporter mice with three identical NF-κB sites (5′-GGGACTTTCC-′3) derived from the immunoglobulin κ-light chain enhancer region, coupled to the luciferase reporter gene were used.24

Vitamin A-deficient mice

The vitamin A-deficient mice used in these experiments were the offspring of dams who where fed a vitamin A-deficient diet (C 1016; Altromin, Lage, Germany) from the onset of the gestation period, and were maintained on this diet until after the offspring were weaned. Once weaned, the offspring were fed this vitamin A-deficient diet throughout the course of the experiment. Mice fed this diet have previously been shown to have significantly lower levels of retinol and retinylesters in the liver than mice fed a normal vitamin A-sufficient diet.23

In vivo imaging of luciferase activity

Mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane (Baxter, Deerfield, IL) (2·5%) and placed in a light-proof imaging chamber, and kept anaesthetized throughout the imaging period. D-luciferin (Biosynth, Staad, Switzerland) (4 mg; ∼ 150 mg/kg) dissolved in 200 μl phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7·8, was injected into each mouse intraperitoneally. Seven minutes later the whole mouse was imaged for 1 min on the ventral side. The imaging system used was IVIS100 (Caliper Life Sciences). The images were processed using the software IgorPro 4.06 (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) and photons emitted from the entire mouse were quantified using Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences) and expressed as photons/second/cm2/steradian.

Measurement of luciferase activity in cell cultures

Luciferase activity in isolated cells was measured directly in the 96-well cell culture plates using the IVIS Imaging System 100 Series (Caliper Life Sciences). In brief, 2 μl D-luciferin (0·13 mg/ml) was added to each well, and the plate was placed in a light-proof imaging chamber. After 4 min, the plate was imaged for 1 min. The imaging system used was IVIS100 (Caliper Life Sciences). The images were processed using software IgorPro 4.06 (Wavemetrics). Quantification of luciferase activity (photons/second/well/steradian) was performed by use of Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences).

Isolation of T cells from spleen and lymph nodes

T cells from spleen and lymph node were isolated by negative selection using Dynabeads according to the manufacturer’s procedure (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). In brief, organs were removed and forced through a 60-mesh screen (Sigma). Cell suspensions were incubated with antibodies to non-T cells for 15 min at 4°. Magnetic beads were then added and incubated for another 25 min at room temperature before beads and adherent cells were separated with a magnet. The purity of the T-cell preparations was on average 90%, as determined by flow cytometric analysis with antibody to CD3.

Cell culturing

The T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), 2 mm glutamine, 125 U/ml penicillin, 125 μg/ml streptomycin and 50 μmβ-mercaptoethanol at 37° in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. For some of the experiments, T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3. Briefly, 96-well plates were incubated with 2 μg/ml anti-CD3 for 1 hr at 37°. Wells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and cells were added subsequently.

Measurement of DNA synthesis

Cells were cultured in flat-bottomed microtitre plates in triplicates at an initial density of 1 × 105/0·2 ml. After pulsing the cells with 1·25 μCi of [3H]thymidine (TRA120; Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK) for the last 20 hr of a 72-hr incubation, the cells were transferred to Unifilter-96 GF/C filters (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) by using a Packard FilterMate cell harvester (Packard Bioscience Company, Meridan, CT) and counted on a Topcount liquid scintillation counter (Packard) using 25 μl MicroScint cocktail (Packard) per well.

Isolation of messenger RNA and real time polymerase chain reaction

The messenger RNA (mRNA) from cultured splenic T cells was isolated using magnetic oligo-dT beads from Genovision (West Chester, PA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sonication of the cell lysate was performed for 5 seconds, 60% output, using Vibracell (Sonics and Materials Inc., Newtown, CT). The cDNA synthesis was performed using an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of IL-2 and cyclophilin B was performed using the LightCycler from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). Primers were designed using Roche’s LightCycler Probe Design Software version 1.0. The protocol for Roche’s LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I was used and optimized for each primer set. A melting curve analysis was performed at the end of each reaction to detect the presence of potential non-specific PCR products, and the PCR was optimized to eliminate such products. Both primer pairs gave a PCR product of the expected length. A standard curve made from the cDNA template was made for each experiment and each primer set. The amount of target gene relative to reference gene was quantified using Roche’s LightCycler Relative Quantification software. The IL-2 primers utilized were forward primer: 5′-CCTGAGCAGGGAGAATTACA-3′, reverse primer: 5′-TCCAGAACATGCCGCAGA-3′ and the cyclophilin B primers were forward primer: 5′-CAAGCTGAAGCACTACG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-AGGCCGTTCTAGCTTC-3′.

Statistical analysis

spss 14.0 for Windows was used to perform the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, independent sample t-test and paired sample t-test as indicated.

Results

All-trans retinoic acid inhibits IL-2 gene expression in vivo

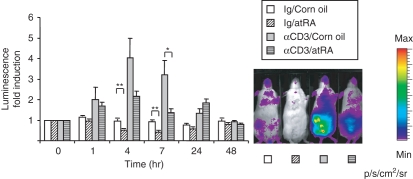

To examine the effects of atRA on IL-2 gene expression in vivo, we used a mouse reporter model containing the 10·7-kb murine IL-2 gene in front of a modified firefly luciferase cDNA. Luciferase activity measured as luminescence reflects activation of the IL-2 gene. In the absence of stimuli, the reporter model displayed a more or less generalized signal throughout the animal with highest expression in the abdominal region. To activate T cells, mice were injected with 1 μg anti-CD3 antibody, which binds to the CD3ε chain of the mouse T-cell receptor and mimics T-cell receptor activation.25 Such low doses of anti-CD3 have been shown to induce immune responses without causing immunosuppression.26,27 As early as 1 hr after injection of anti-CD3 antibody, we observed a rise in whole-body luminescence with the highest expression in the abdominal region (Fig. 1). The induction was maximal after 4–7 hr and returned to baseline by 24–48 hr (Fig. 1). In mice receiving an oral dose of atRA, the anti-CD3-mediated increase was significantly less after 7 hr of treatment (55% lower than anti-CD3, P< 0·05, n= 10) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, in mice injected with control antibody, atRA reduced basal luminescence by approximately 50% at 4 and 7 hr (P< 0·01, n= 10) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Down-regulation of interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene expression in whole mice following all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) administration. The IL-2 luciferase reporter mice were given atRA (50 mg/kg) or corn oil before injection of anti-CD3 antibody or control antibody (Ig) as indicated. Images were taken before atRA/anti-CD3 administration (0 hr) and then after 1 hr, 4 hr, 7 hr, 24 hr and 48 hr. (n= 5 at 24 hr and n= 3 at 48 hr, n= 10 at the other time-points). Average luciferase activity at each time-point is shown relative to luciferase activity at 0 hr ± SEM. *P< 0·05, **P< 0·01, independent samples t-test. One representative example of whole-body luminescence at 7 hr of mice treated as indicated is shown.

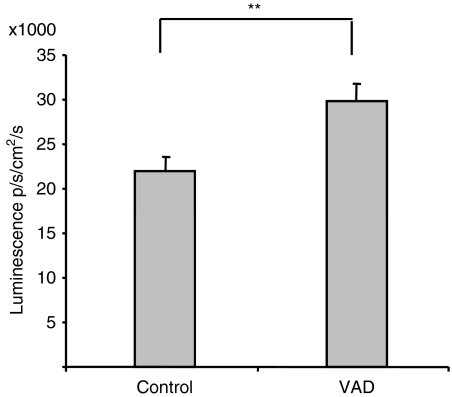

IL-2 gene expression is increased in vitamin A-deficient mice

Since atRA apparently inhibited IL-2 gene expression, we wanted to examine whether IL-2 gene expression was altered in mice made deficient for vitamin A. To this end, basal IL-2 promoter-driven luminescence was examined in vitamin A-deficient mice and in mice fed a standard vitamin A-sufficient diet. Whole body luminescence was increased by 36% in vitamin A-deficient mice compared to control mice (P< 0·01, n= 20) (Fig. 2), demonstrating that vitamin A influences IL-2 gene expression in vivo.

Figure 2.

Vitamin A-deficient (VAD) mice have a higher basal activity of interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene expression. Twenty VAD mice and 20 age-matched controls were anaesthetized and injected with 200 μl luciferin in phosphate-buffered saline. After 7 min, luminescence of the whole mouse was examined. Average luminescence ± SEM is shown. **P< 0·01, n= 20, independent samples t-test.

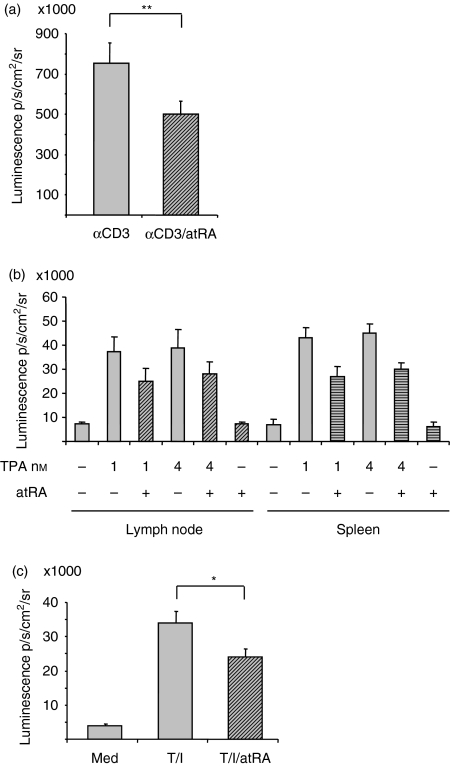

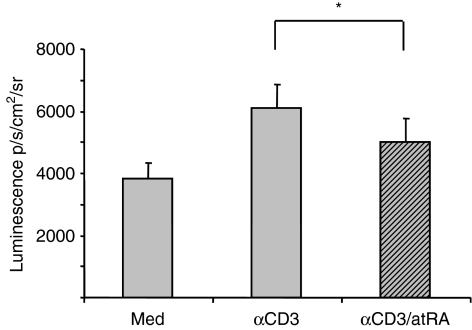

All-trans RA inhibits IL-2 gene expression in murine T cells in vitro

To examine whether the difference in atRA-mediated IL-2 gene expression in murine versus human T cells was the result of in vivo compared with in vitro conditions, we determined IL-2 promoter-driven luminescence in cultured murine T cells. To this end, murine splenic T cells were stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of atRA. Analogous to the in vivo-state, atRA inhibited luciferase activity in cells stimulated with anti-CD3, and on average the luminescence was reduced by 31 ± 5% after 4 hr of treatment (mean ± SEM) (P< 0·01, n= 9) (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

All-trans retinoic acid (atRA) inhibits interleukin-2 (IL-2) gene activity in isolated cells. (a) T cells from spleen were cultures in triplicates with immobilized anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of atRA (100 nm). (b) T cells from lymph nodes and spleen were cultured in triplicates with or without 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA; 1 or 4 × 10−9m) in the presence or absence of atRA (100 nm). (c) T cells from spleen were cultured in triplicates with TPA (10−9 m) and ionomycin (0·5 μm) in the presence or absence of atRA (100 nm). (a–c) After 4 hr, luciferin was added, and luminescence was examined as described in the Materials and methods. Average luminescence ± SEM are shown of the median of triplicates from cells of nine mice (a and c) and four mice (b; **P< 0·01, paired samples t-test, *P< 0·05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

In human peripheral blood T cells, the most pronounced effect of atRA was seen with TPA as the stimulating agent. To test whether the contrasting effect noted in mice and human T cells could be the result of different stimuli or different sources of T cells, cells from either lymph nodes or spleen were stimulated with two different concentrations of TPA in the presence or absence of atRA. As shown in Fig. 3(b), TPA induced luciferase activity in both spleen and lymph node T cells, and atRA inhibited the luminescence in T cells from both organs (Fig. 3b). Also in T cells stimulated with TPA and ionomycin, atRA significantly inhibited the increased luciferase activity determined after 4 hr (Fig. 3c). Evidently, in contrast to human T cells, atRA causes reduced IL-2 gene expression in mice both in vivo and in vitro.

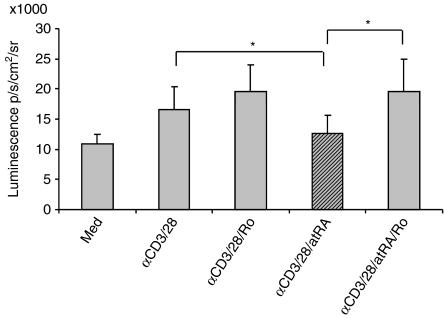

The effect of atRA on IL-2 expression is mediated via RARs

Most of the effects of atRA are mediated via its binding to RARs, which combine with the retinoid X receptor family to form heterodimeric transcription factor complexes. To examine whether the effect of atRA was mediated through RARs, the RARα antagonist Ro 41-5253 was employed. However, in this experiment, cells tended to die when exposed to the strong stimuli of immobilized anti-CD3 in combination with Ro 41-5253 (data not shown). Hence, in this experiment, T cells were stimulated with a combination of soluble anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies which deliver a weaker signal to the cell. Moreover, because the antagonist has to be present in a molar excess,28 a concentration of 10 nm RA and 500 nm Ro 41-5253 was used. As shown in Fig. 4, atRA inhibited luciferase activity in stimulated cells at physiological concentrations (10 mm), and the inhibition could be reversed by the RARα antagonist. This suggests that RARα is involved in the atRA-mediated inhibition of IL-2 gene expression.

Figure 4.

An antagonist of retinoic acid receptor (RAR) reverses the inhibiting effect of all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) on interleukin-2 (IL-2) expression. T cells from spleen were left untreated or stimulated with anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) in triplicates in the presence or absence of atRA (10 nm). Where indicated, cells were pretreated with Ro 41-5253 (500 nm). After 4 hr, luciferin was added, and the luminescence was examined. The average luminescence ± SEM of the median of triplicates from cells of six mice is shown, *P< 0·05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

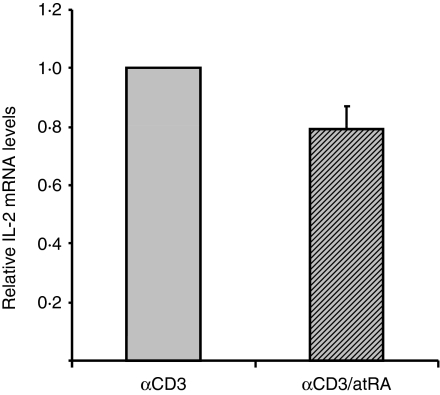

All-trans RA inhibits IL-2 mRNA expression and proliferation of isolated murine T cells

To examine whether the changes we observed in luciferase activity in murine cells reflects endogenous regulation of IL-2, we measured IL-2 mRNA levels in isolated splenic T cells. Quantitative PCR was performed using primers specific for murine IL-2 and the control gene cyclophilin B. In the absence of stimuli no IL-2 mRNA was detected (data not shown). However, IL-2 was induced by anti-CD3, and atRA inhibited this increase by an average of 20% in cells from six out of eight mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

All-trans retinoic acid (atRA) inhibits interleukin-2 (IL-2) messenger RNA (mRNA) in in vitro stimulated cells. T cells from spleen were stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of atRA (100 nm). After 4 hr cells were harvested and mRNA was isolated as described in the Materials and methods. Real time polymerase chain reaction was performed with primers to IL-2 and cyclophilin B was used as internal control. The average of relative IL-2 mRNA ± SEM is shown of cells of six mice.

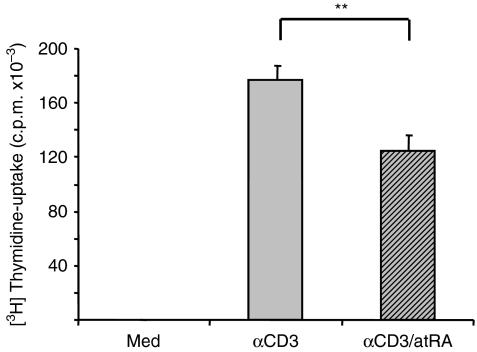

In human T cells the increased IL-2 production induced by atRA was accompanied by increased proliferation of the cells.14 We next examined whether the decrease in IL-2 gene expression in murine T cells by atRA was reflected in altered T-cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 6, T cells displayed an increased DNA synthesis upon stimulation with immobilized anti-CD3, and atRA inhibited this induction by approximately 30% without affecting cell viability (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that atRA-mediated inhibition of IL-2 gene expression in mice may have physiological consequences in terms of reduced proliferation of T cells.

Figure 6.

All-trans retinoic acid (atRA) inhibits proliferation of isolated splenic T cells. T cells from spleen were left untreated or stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 (2 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of atRA (100 nm) for 3 days. [3H]Thymidine was added for the last 24 hr, and DNA synthesis was determined as described in the Materials and methods. Bars represent average counts/min ± SEM of the median of triplicates of cells from eight mice. **P< 0·01, paired samples t-test.

All-trans RA inhibits NF-κB activation in murine splenic T cells in vitro

The IL-2 promoter contains multiple response elements including those for nuclear factor of activated T cells, activating protein-1 and NF-κB.2 In another study on human T lymphocytes, we did not see any changes in the activity of common response elements in the presence of atRA (Ertesvag et al., unpublished results). However, we have previously shown that atRA inhibits basal NF-κB activity in mice using in vivo imaging of NF-κB-luciferase reporter mice.23 Furthermore, mice fed a vitamin A-deficient diet demonstrated an increase in NF-κB promoter activity both in whole mice and in isolated T cells.23 To test whether atRA also inhibited anti-CD3-stimulated NF-κB activity in splenic T cells, we measured NF-κB luminescence in T cells in cultures from transgenic NF-κB-luciferase reporter mice. As shown in Fig. 7, atRA significantly inhibited NF-κB activity in splenic T cells, suggesting that one possible mechanism by which atRA might inhibit IL-2 gene activity in murine T cells could be via the inhibition of NF-κB.

Figure 7.

All-trans retinoic acid (atRA) inhibits anti-CD3-stimulated nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity in T cells. T cells were isolated from spleens of NF-κB-regulated luciferase reporter mice and cultured in triplicates alone or with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody (2 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of atRA (100 nm). After 4 hr, luminescence was recorded as described in the Materials and methods. The average luminescence of medians ± SEM (*P< 0·05, n= 5, Wilcoxon signed-rank test) is shown.

Discussion

Interleukin-2 has a key role in determining the magnitude and duration of primary and secondary immune responses, and atRA can influence IL-2 expression and IL-2 signalling.14,15,29–32 We demonstrated that atRA, via induction of IL-2, increases proliferation and inhibits the spontaneous death of human T lymphocytes,14,15 and we have also shown that atRA can potentiate IL-2-mediated proliferation of T cells.29 It was therefore surprising to observe the inhibition of IL-2 gene expression in mice in vivo in the presence of RA. We found that atRA reduced IL-2 gene expression both in whole mice and in cells from lymph nodes and spleen. Furthermore, vitamin A-deficient mice expressed significantly higher basal luminescence than mice fed a vitamin A-sufficient diet. The apparent discrepancy between our previous in vitro studies on human T cells and the present in vivo effects in mice could have several explanations. First, the IL-2 reporter may not reflect regulation of endogenous IL-2, second there could be differences between in vitro and in vivo conditions and moreover the results may reflect a fundamental difference in IL-2 regulation in mice and humans.

Based on the data presented, we find the first two alternatives less likely to be responsible for the observed effects. We strongly believe that the IL-2 luciferase reporter model reflects regulation of endogenous IL-2 based on the following observations. When examining untreated mice, basal luminescence was observed in the abdominal region, which is in accordance with previously demonstrated IL-2 expression in mature T lymphocytes of the lamina propria of the gut.33 Moreover, when examining the various organs, basal luminescence was observed in the thymus and lymph nodes, whereas low luminescence was observed in spleen and liver, and no luciferase activity was detected in non-lymphoid organs like brain, fat, heart, kidney, skin, lung or muscle (data not shown), which also correlates with known cell and organ-specific expression of IL-2.33 The IL-2 promoter-driven luminescence was shown to be regulated by classical IL-2 gene inducers such as anti-CD3 antibody, and according to the provider (Caliper Life Sciences), IL-2 gene activity was diminished by immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporine A, which is known to inhibit IL-2 expression. The transient nature of induction of the IL-2 gene also correlates with known expression profiles of endogenous IL-2.34 We also confirmed the effect of atRA by measuring IL-2 mRNA, and we demonstrated that the reduced level of IL-2 gene activity in murine T cells treated with atRA in vitro was reflected in reduced proliferation of the cells. Taken together, these observations strongly indicate that the IL-2 luciferase reporter model used in the present study is a reliable model for studying the regulation of IL-2 gene expression.

To address the possibility that atRA has differential effects on IL-2 expression in T cells under in vitro and in vivo conditions, we subjected isolated T cells from lymphoid organs to atRA. By demonstrating inhibition of IL-2 gene activity by atRA also in isolated cells, we concluded that atRA has a similar inhibitory effect on IL-2 gene expression in murine T cells in vitro as in vivo. The previous human study was performed on T cells isolated from peripheral blood,14 whereas the present study included T cells isolated from spleen and lymph nodes. It could therefore be argued that the source of lymphocytes, and hence their activation status, could be responsible for the different effects observed in mice and humans. Because of the small amount of blood obtainable from mice we were not able to perform these studies on murine peripheral blood T cells, and we therefore cannot rule out this possibility. However, because the activation status as measured by thymidine uptake in unstimulated mouse T cells was very low and similar to that in unstimulated human T cells (data not shown), we believe that the differences in activation status between the two sources of T cells cannot explain the different responses. This left us with the last alternative; i.e. that IL-2 expression is differentially regulated by atRA in murine and human T cells.

Mice have been considered the primary mammalian experimental model in most fields of biological research including studies related to the immune system. Fewer than 300 of the protein-coding genes in the mouse genome lack a detectable homologue in the human genome, while a similar fraction of human genes lack a detectable homologue in mice. Despite the relatively few differences between the genomes of the two species, an increasing number of reports reveal differences in both the innate and the adaptive parts of the immune defence between mice and humans.35 The overall positive effect of vitamin A in the immune system has been extensively documented both in humans and in animals,9–12 and the stimulatory effect of atRA that we observe on IL-2 gene expression in human T-cell cultures fits well into this scheme. Still there have been reports on vitamin A and the murine immune system that have not been easy to fit into this simple model. For instance, retinol was found to inhibit the secretion of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-2 in vitro and also to inhibit the proliferation of lymphocytes from mice infected with Leishmania major.20 Moreover, Colizzi and Malkovsky demonstrated that vitamin A-deficient mice infected with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin secreted relatively more IL-2 than mice fed a control diet.36 These latter reports fit rather well with our current results based on IL-2 gene expression studies in transgenic reporter mice. Interestingly, it has been shown that atRA can induce the homing of T cells from lymphoid organs to the gut.37,38 We therefore tested whether the reduced IL-2 gene expression that we noted in lymphoid cells and organs of atRA-treated reporter mice could be the result of redistribution of T cells from lymphoid organs to the gut. However, close examination of the intestine ex vivo revealed no increased IL-2 gene expression 7 hr after administration of atRA (data not shown).

There has been some controversy regarding the effect of vitamin A on T-cell cytokine production in rodent models. The classical view has been that vitamin A deficiency is associated with increased T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine secretion (IFN-γ and IL-2) and inhibited Th2 cytokine secretion (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-10),39,40 and correspondingly, that addition of vitamin A induces secretion of Th2 cytokines and repression of secreted Th1 cytokines.41–44 However, this view has been challenged by other reports demonstrating that the number of IL-10-producing cells was higher, and of IFN-γ-producing and IL-2-producing cells was lower in vitamin A-deficient mice compared to control mice.21 The picture is also complicated by the fact that the signature cytokines by Th1 and Th2 cells differ between humans and mice. For example, whereas mouse Th1 cells produce IL-2 and IFN-γ and Th2 cells produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-13, the synthesis of IL-2, IL-6 and IL-10 by human T cells is not as tightly restricted to a single cell subset.45,46 In humans, it appears that precursor CD4+ cells secrete IL-2 when stimulated before they differentiate into either Th1 or Th2 cells.47 Nevertheless, secretion of IL-2 has been regarded as an early and reliable indication for T-cell activation. Our present study supports the view that vitamin A deficiency is associated with a bias towards Th1 responses (increased IL-2 secretion) in mice. However, given the notion that IL-2 stimulates an immune response in T cells, it is difficult to understand how vitamin A inhibits IL-2 but may impose a positive effect on general immune function. One explanation for this apparent inconsistency could be that factors other than IL-2 are central in inflicting a robust immune response in mice. For instance, IL-4 has been shown to be more important than IL-2 for the survival of T lymphocytes in mice.48 However, an even more interesting candidate to explain the different effect of atRA-mediated regulation of IL-2 in mice compared with humans is NF-κB. Although NF-κB is established as an important regulator of IL-2 expression,49 the atRA-mediated induction of IL-2 in human T cells was not associated with activation of NF-κB (Ertesvag et al., unpublished results). It was therefore an interesting observation that atRA in the present study inhibited the activation of NF-κB in murine splenic T cells. We have previously reported that atRA inhibits NF-κB promoter activity in NF-κB luciferase reporter mice,23 and given the key role of NF-κB in inflammation,50 we related this effect of atRA to its anti-inflammatory role. It is possible that vitamin A has a more anti-inflammatory role in mice than in humans, and that the role of vitamin A as a regulator of the immune system in humans is a more subtle one. An anti-inflammatory role of vitamin A is supported by the bias towards Th1 inflicted by increased IL-2 secretion in the present study. Evidently, more research is required to understand how vitamin A stimulates the immune system in both mice and humans, and our results emphasize that caution should be exercised when extrapolating results obtained in mice directly to human physiology – and vice versa.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hilde R. Haug and Camilla Solberg for technical assistance and Lene Gilen for assistance with animal breeding. This work has been supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society, The Norwegian Research Council, The Freia Research Foundation, The Jahre Research Foundation, The Blix Family Legacy, The Rakel and Otto Christian Bruuns Legacy and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AtRA

all-trans retinoic acid

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- IFN

interferon

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- kb

kilobase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RAR

retinoic acid receptor

- Th1

T helper type 1

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gaffen SL, Liu KD. Overview of interleukin-2 function, production and clinical applications. Cytokine. 2004;28:109–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rothenberg EV, Ward SB. A dynamic assembly of diverse transcription factors integrates activation and cell-type information for interleukin 2 gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9358–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng L, Fisher G, Miller RE, Peschon J, Lynch DH, Lenardo MJ. Induction of apoptosis in mature T cells by tumour necrosis factor. Nature. 1995;377:348–51. doi: 10.1038/377348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhein J, Walczak H, Baumler C, Debatin KM, Krammer PH. Autocrine T-cell suicide mediated by APO-1/(Fas/CD95) Nature. 1995;373:438–41. doi: 10.1038/373438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildeman DA, Zhu Y, Mitchell TC, Kappler J, Marrack P. Molecular mechanisms of activated T cell death in vivo. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:354–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:665–74. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Vitamin A Deficiency. 2008. [accessed 7 August 2008]. http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/vad/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.Underwood BA. Vitamin A in human nutrition: public health considerations. In: Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry and Medicine. 2nd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 211–27. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephensen CB. Vitamin A, infection, and immune function. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:167–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semba RD. Vitamin A and immunity to viral, bacterial and protozoan infections. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:719–27. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blomhoff HK, Smeland EB. Role of retinoids in normal hematopoiesis and the immune system. In: Blomhoff R, editor. Vitamin A in Health and Disease. 1st edn. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1994. pp. 451–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross AC, Hämmerling UG. Retinoids and the immune system. In: Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry and Medicine. New York: Raven Press Ltd; 1994. pp. 521–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangelsdorf DJ, Umeson K, Evans RM. The retinoid receptors. In: Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry and Medicine. 2nd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 319–49. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ertesvag A, Engedal N, Naderi S, Blomhoff HK. Retinoic acid stimulates the cell cycle machinery in normal T cells: involvement of retinoic acid receptor-mediated IL-2 secretion. J Immunol. 2002;169:5555–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engedal N, Ertesvag A, Blomhoff HK. Survival of activated human T lymphocytes is promoted by retinoic acid via induction of IL-2. Int Immunol. 2004;16:443–53. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiedermann U, Hanson LA, Kahu H, Dahlgren UI. Aberrant T-cell function in vitro and impaired T-cell dependent antibody response in vivo in vitamin A-deficient rats. Immunology. 1993;80:581–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiedermann U, Hanson LA, Bremell T, Kahu H, Dahlgren UI. Increased translocation of Escherichia coli and development of arthritis in vitamin A-deficient rats. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3062–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3062-3068.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carman JA, Hayes CE. Abnormal regulation of IFN-gamma secretion in vitamin A deficiency. J Immunol. 1991;147:1247–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carman JA, Pond L, Nashold F, Wassom DL, Hayes CE. Immunity to Trichinella spiralis infection in vitamin A-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1992;175:111–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankenburg S, Wang X, Milner Y. Vitamin A inhibits cytokines produced by type 1 lymphocytes in vitro. Cell Immunol. 1998;185:75–81. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephensen CB, Jiang X, Freytag T. Vitamin A deficiency increases the in vivo development of IL-10-positive Th2 cells and decreases development of Th1 cells in mice. J Nutr. 2004;134:2660–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawson HD, Ross AC. Chronic marginal vitamin A status affects the distribution and function of T cells and natural T cells in aging Lewis rats. J Nutr. 1999;129:1782–90. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.10.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austenaa LM, Carlsen H, Ertesvag A, Alexander G, Blomhoff HK, Blomhoff R. Vitamin A status significantly alters nuclear factor-kappaB activity assessed by in vivo imaging. FASEB J. 2004;18:1255–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1098fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carlsen H, Moskaug JO, Fromm SH, Blomhoff R. In vivo imaging of NF-kappa B activity. J Immunol. 2002;168:1441–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leo O, Foo M, Sachs DH, Samelson LE, Bluestone JA. Identification of a monoclonal antibody specific for a murine T3 polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1374–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellenhorn JD, Hirsch R, Schreiber H, Bluestone JA. In vivo administration of anti-CD3 prevents malignant progressor tumor growth. Science. 1988;242:569–71. doi: 10.1126/science.2902689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirsch R, Gress RE, Pluznik DH, Eckhaus M, Bluestone JA. Effects of in vivo administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody on T cell function in mice. II. In vivo activation of T cells. J Immunol. 1989;142:737–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Apfel C, Bauer F, Crettaz M, et al. A retinoic acid receptor alpha antagonist selectively counteracts retinoic acid effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7129–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engedal N, Gjevik T, Blomhoff R, Blomhoff HK. All-trans retinoic acid stimulates IL-2-mediated proliferation of human T lymphocytes: early induction of cyclin D3. J Immunol. 2006;177:2851–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allende LM, Corell A, Madrono A, et al. Retinol (vitamin A) is a cofactor in CD3-induced human T-lymphocyte activation. Immunology. 1997;90:388–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1997.00388.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballow M, Xiang S, Greenberg SJ, Brodsky L, Allen C, Rich G. Retinoic acid-induced modulation of IL-2 mRNA production and IL-2 receptor expression on T cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1997;113:167–9. doi: 10.1159/000237536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dennert G. Immunostimulation by retinoic acid. Ciba Found Symp. 1985;113:117–31. doi: 10.1002/9780470720943.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang-Snyder JA, Rothenberg EV. Spontaneous expression of interleukin-2 in vivo in specific tissues of young mice. Dev Immunol. 1998;5:223–45. doi: 10.1155/1998/12421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferran C, Dy M, Sheehan K, et al. Inter-mouse strain differences in the in vivo anti-CD3 induced cytokine release. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;86:537–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb02966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mestas J, Hughes CC. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172:2731–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colizzi V, Malkovsky M. Augmentation of interleukin-2 production and delayed hypersensitivity in mice infected with Mycobacterium bovis and fed a diet supplemented with vitamin A acetate. Infect Immun. 1985;48:581–3. doi: 10.1128/iai.48.2.581-583.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, Song SY. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity. 2004;21:527–38. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cantorna MT, Nashold FE, Hayes CE. Vitamin A deficiency results in a priming environment conducive for Th1 cell development. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1673–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carman JA, Smith SM, Hayes CE. Characterization of a helper T lymphocyte defect in vitamin A-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1989;142:388–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui D, Moldoveanu Z, Stephensen CB. High-level dietary vitamin A enhances T-helper type 2 cytokine production and secretory immunoglobulin A response to influenza A virus infection in BALB/c mice. J Nutr. 2000;130:1132–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.5.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephensen CB, Rasooly R, Jiang X, et al. Vitamin A enhances in vitro Th2 development via retinoid X receptor pathway. J Immunol. 2002;168:4495–503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwata M, Eshima Y, Kagechika H. Retinoic acids exert direct effects on T cells to suppress Th1 development and enhance Th2 development via retinoic acid receptors. Int Immunol. 2003;15:1017–25. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cantorna MT, Nashold FE, Hayes CE. In vitamin A deficiency multiple mechanisms establish a regulatory T helper cell imbalance with excess Th1 and insufficient Th2 function. J Immunol. 1994;152:1515–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, Giedlin MA, Coffman RL. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136:2348–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mosmann TR, Sad S. The expanding universe of T-cell subsets: Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–46. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sad S, Mosmann TR. Single IL-2-secreting precursor CD4 T cell can develop into either Th1 or Th2 cytokine secretion phenotype. J Immunol. 1994;153:3514–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vella AT, Dow S, Potter TA, Kappler J, Marrack P. Cytokine-induced survival of activated T cells in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3810–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bunting K, Wang J, Shannon MF. Control of interleukin-2 gene transcription: a paradigm for inducible, tissue-specific gene expression. Vitam Horm. 2006;74:105–45. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)74005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senftleben U, Karin M. The IKK/NF-kappa B pathway. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]