Abstract

Human B cells can be cultured ex vivo for a few weeks, following stimulation of the CD40 cell surface molecule in the presence of recombinant cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4). However, attempts to produce polyclonal antigen-specific human antibodies by in vitro culture of human B cells obtained from immunized donors have not been successful. It has been shown in mice that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a potent mitogen for B cells and plays an important role in the generation of antigen-specific antibody responses. Although it has long been believed that LPS has no direct effect on human B cells, recent data indicating that IL-4-activated human B cells are induced to express Toll-like receptor-4, the main LPS receptor, prompted us to study the effects of LPS on the proliferation and antibody secretion of human B cells. Our results showed that LPS caused a reduction in the expansion of CD40-activated human B cells, accompanied by an increase in antigen-specific antibody secretion. This result suggested that some, but not all, B cells were able to differentiate into antibody-secreting cells in response to LPS. This increased differentiation could be explained by the observation that LPS-stimulated human B cells were induced to secrete higher amounts of IL-6, a pleiotropic cytokine well-known for its B-cell differentiation activity. In vivo, the effect of LPS on cytokine secretion by B cells may not only enhance B-cell differentiation but also help to sustain a local ongoing immune response to invading Gram-negative bacteria, until all pathogens have been cleared from the organism.

Keywords: antibody secretion, human B cell, interleukin-6, lipopolysaccharide

Introduction

Following antigenic challenge, resting human B cells are induced to proliferate and differentiate into plasma and memory cells. This process requires help from activated T cells by direct cell–cell interactions and the secretion of soluble factors.1,2 One of the key interactions has been identified by the group of Banchereau who showed that ligation of the inducible T-cell surface molecule, CD154, with its ligand (CD40) constitutively expressed on B cells, was essential for B-cell survival.3,4 Indeed, human B cells can be cultured ex vivo for several weeks, using cell lines constitutively expressing CD154 or anti-CD40 antibodies and the addition of recombinant cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4).5,6

The possibility of growing human B cells ex vivo, with subsequent differentiation into antibody-secreting cells, has led us to investigate the use of in vitro culture for the production of human polyclonal antibodies with defined specificities, by starting with peripheral blood B cells from immunized donors. Such antibodies, prepared in vitro, could be used as substitutes to human plasma-derived hyperimmune immunoglobulin G (IgG) preparations. Although we could detect the presence of antigen-specific IgG in human B-cell cultures, the proportion of these specific antibodies among the total IgG secreted was very low (R. Lemieux and R. Bazin, unpublished observations). Recent work by Pasare and Medzhitov showed that generation of antigen-specific antibody responses in mice required activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) expressed on B cells.7 Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) has been known for many years to be a potent mitogen for mouse B cells but has long been considered to have no effect on human B cells.8 This could be explained by the fact that mouse B cells constitutively express a variety of TLRs9,10 including TLR-4, the main receptor for LPS, while naïve and memory human B cells express only very low levels of TLR-4.11 However, it has been shown recently that IL-4 up-regulates TLR-4 surface expression on human peripheral B cells,12 suggesting that human B cells could become responsive to LPS after activation. The present study was undertaken to evaluate the effects of LPS on the proliferation and antibody secretion of CD40-activated human B cells cultured in the presence of cytokines. Our results demonstrated that LPS had a direct effect on activated human B cells, resulting in a decreased rate of cell expansion accompanied by a significant increase in the secretion of tetanus toxoid (TT)-specific and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-specific antibodies.

Materials and methods

Human and mouse B-cell isolation

Blood samples were collected from healthy individuals into heparinized tubes (Vacutainer; BD Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) after obtaining informed consent. Samples were then pooled and diluted in one volume of phosphate-buffered saline (Invitrogen Canada Inc., Burlington, Canada) containing glucose (2 g/l; Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd, Oakville, Canada). For some experiments, white blood cells were obtained using leucoreduction chambers after platelet collection by aphereris from consenting volunteers, as described elsewhere.13 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were prepared by density centrifugation over Ficoll–Paque (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Inc., Baie D’Urfé, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Human B cells were purified by negative selection using the StemSep® Human B-Cell Enrichment kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Purified human B cells were > 95% CD19+ as determined by flow cytometry analysis. In some experiments, B cells were further purified into CD138+ cells, using the EasySep® Human CD138 Selection Kit (StemCell Technologies). Mouse B cells were isolated from the spleens of female BALB/c mice (Charles Rivers, Montreal, Canada), using the StemSep® Mouse B-Cell Enrichment kit (StemCell Technologies).

Cell culture

Purified B cells were seeded at 2·5 × 105 cells/ml in the wells of flat-bottom Primaria six-well microplates (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, Canada), in the presence of 1 × 104 gamma-irradiated CD154-expressing L4.5 cells/ml unless otherwise indicated. The L4.5 cell line was prepared in our laboratory.6 The cells were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% ultra-low IgG fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, 10 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 6 ng/ml sodium selenite (all from Invitrogen), 50 U/ml human recombinant IL-2 (rIL-2), 50 ng/ml human rIL-10 (both from Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 50 U/ml human rIL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Half of the medium was replaced every 2–3 days and freshly irradiated L4.5 cells were added every 4–5 days. When indicated, LPS (Escherichia coli 026 : B6) (Sigma-Aldrich Canada Ltd) was added to the cultures at a final concentration of 20 μg/ml. Cell numbers and viability were evaluated by triplicate counts using trypan blue (0·4%) exclusion on a haemocytometer. Human B-cell lines (SUP-B15, Raji, Ramos, Daudi, SKW6·4, Pfeiffer, DB and RPMI-8226) were all obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured as follows: SUP-B15 in IMDM containing 20% FBS, Ramos in IMDM containing 5% FBS and all other cell lines in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, in the presence or absence of 20 μg/ml LPS.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Total IgG and IgM concentrations were measured in culture supernatants using a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in 96-well round-bottom plates (Immulon II, Dynatech Laboratories, Alexandria, VA) adsorbed with either goat anti-human IgG (Fc fragment-specific) or goat anti-human IgM (Fc5μ fragment-specific). Bound IgG or IgM were revealed with a goat anti-human IgG, IgM, IgA (H+L) peroxidase conjugate. All antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. (West Grove, PA). Tetramethyl-benzidine (TMB; ScyTek Laboratories, Logan, UT) was used as substrate and optical densities were read at 450 nm on an MRX 386-4RD microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories). The antigen-specific ELISA was performed in microplates coated with 2·5 μg/ml of either TT (EMD Biosciences, Inc., San Diego, CA) or HBsAg (a kind gift from Dr Alan Shaw, Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, PA) and the bound antibodies were revealed using an anti-human IgG (Fc-specific) peroxidase conjugate. The concentration of IL-6 in the culture supernatants of B cells stimulated for 3 days or of CD138+ B cells stimulated for 2 days with or without LPS (20 μg/ml) was measured using the Human IL-6 ELISA Development Kit from Peprotech, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was prepared using the Absolutely RNA® Miniprep Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) followed by a 15-min treatment with DNAse (Invitrogen) and the amount and purity of RNA were determined on a NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using oligo(dT) as primer. The resulting complementary DNA was subjected to quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using human gene-specific primers for IL-6 and IL-10 (SuperArray Biosciences Corporation, Frederick, MD). Expression of IL-6 and IL-10 messenger RNA (mRNA) was normalized using GAPDH expression. The PCR were performed using the RT2 SYBR Green Master Mix (SuperArray Biosciences Corporation) on an Mx3005P® QPCR System (Stratagene).

Results

Effect of LPS on human B-cell proliferation and antibody secretion

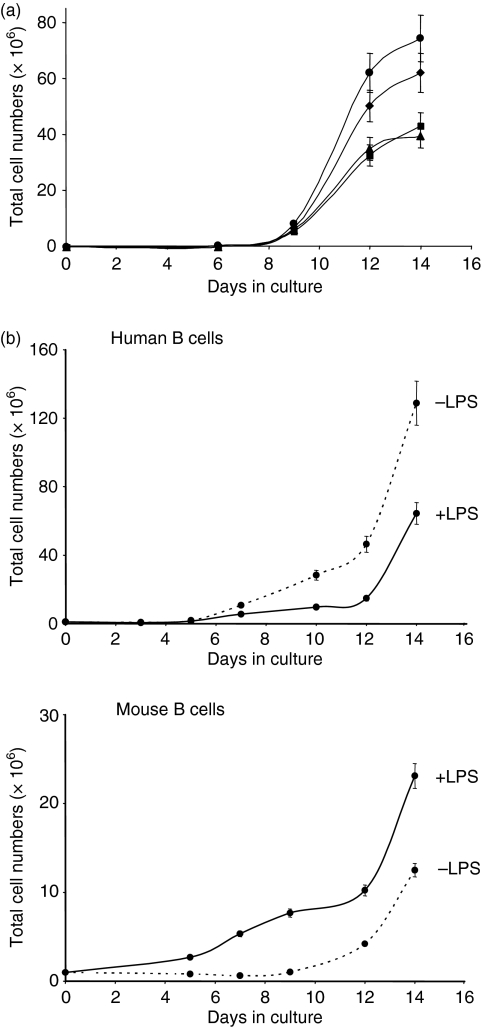

Lipopolysaccharide is a well-recognized mouse, but not human, B-cell mitogen that acts in the absence of other signals. Although it is now possible to grow human B cells in vitro by providing essential signals such as CD40 ligation and cytokines, the direct effect of LPS on human B cells remains largely unknown. We first analysed the effects of LPS on the proliferation of human B cells isolated from several different donors and cultured using the previously described CD40–CD154 system.14 A dose–response analysis was performed using LPS concentrations ranging from 5 to 20 μg/ml. The results obtained showed that at a dose of 5 μg/ml, LPS induced a slight increase in B-cell proliferation, although this increase was not considered to be significant because error bars for triplicate counts overlapped those of the control culture at day 14 (Fig. 1a). The addition of higher doses of LPS resulted in a decrease in B-cell proliferation. The 20-μg/ml dose was used in subsequent experiments, in which the effect of LPS (20 μg/ml) on human B cells was compared to the already known mitogenic effect of LPS on mouse B cells cultured in the same environment (Fig. 1b). The results obtained after 14 days of culture showed a significant and differential effect of LPS which reduced the expansion of human B cells from most donors tested (five donors out of seven) while stimulating the expansion of mouse B cells. This latter result confirmed the already known mitogenic effect of LPS on mouse B cells. Occasionally, we observed that the expansion of human B cells from some donors (two donors out of seven tested) was similar in the presence or absence of LPS (data not shown), suggesting that these donors were less responsive to LPS. Cell viability was high (> 90%) in all cultures, as evaluated by trypan blue exclusion. Because the reduction in human B-cell expansion observed in the presence of LPS was not a consequence of increased apoptosis, we hypothesized that it could be the result of the differentiation of some, but not all, B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells. Total IgG and IgM concentrations were thus measured by ELISA in culture supernatants harvested after 7 and 10 days of culture in the presence or absence of LPS. The results obtained (Table 1) showed that secretion was higher at day 10 compared to day 7 but did not reveal an increase in immunoglobulin secretion (expressed as μg per 106 cells) in the presence of LPS. Evaluation of total immunoglobulin production did not permit the detection of an effect of LPS on B-cell differentiation.

Figure 1.

Effect of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on the proliferation of human and mouse B cells. (a) Human B cells were purified and cultured in the CD40–CD154 system, in the absence (♦) or in the presence of 5 (•), 10 (▴) or 20 (▪) μg/ml Escherichia coli (026:B6) LPS for 14 days. (b) Human and BALB/c mouse B cells were purified and cultured in the CD40–CD154 system, in the presence (solid line) or absence (dotted line) of 20 μg/ml LPS for 14 days. The number and viability of cells were evaluated by triplicate counts using trypan blue exclusion. The accepted standard deviation between counts was ≤ 15%. Additional counts were made when the standard deviation exceeded 15% after three counts. Results shown in (a) are representative of two independent experiments. Results shown in (b) were obtained with B cells from one donor but were typical of experiments carried out with B cells from five different donors.

Table 1.

Effect of lipopolysaccharide on total immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G secretion

| Culture condition | IgM secretion (μg/106cells)1 | IgG secretion (μg/106cells) |

|---|---|---|

| Day 7 | ||

| −LPS | 1·1 | 1·4 |

| +LPS | 0·9 | 1·2 |

| Day 10 | ||

| −LPS | 2·8 | 8·1 |

| +LPS | 1·5 | 5·0 |

IgG and IgM, immunoglobulin G and M; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

B cells from one donor were cultured in the presence or absence of LPS for 10 days before measurement of IgM and IgG levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Results are representative of five separate experiments with B cells from three different donors.

Secretion was expressed as μg/106 cells using B-cell counts in the cultures at the indicated times, to normalize for the differences in cell expansion.

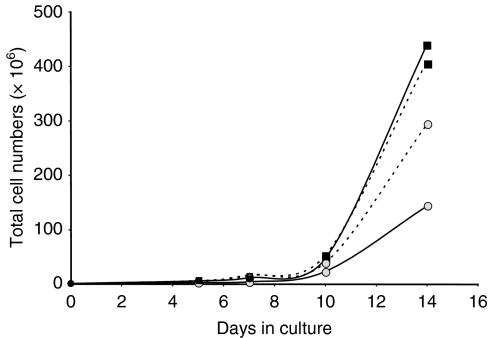

At day 10, the secretion of IgG was much higher than that of IgM (Table 1), suggesting that differentiation of memory B cells was predominant at this stage of the cultures. However, it is known that prolonged in vitro CD40 stimulation can trigger naïve B cells to switch from secretion of IgM to IgG secretion and expression of CD27 in vitro, even in the absence of antigen or somatic hypermutation.15 It was not possible, therefore, using cell surface marker analyses (CD27, murine IgG), to determine whether cells from the naïve or memory B-cell subpopulations, or a combination of both, had a reduced expansion in LPS-supplemented cultures. However, the expansion of naïve and memory B cells can be differentially controlled in the CD40–CD154 system by varying the CD154 signal intensity.14 To determine whether B cells from one compartment (naïve or memory) were more responsive to LPS, we compared the expansion of human B cells in cultures performed with a low CD40 stimulation (ratio of L4.5 to B cells of 1 : 25, see Materials and methods section) or high CD40 stimulation (ratio of L4.5 to B cells of 1 : 3), in the presence or absence of LPS. The latter condition is known to support the expansion of naïve but not memory B cells.14,15 The results (Fig. 2) clearly showed that only B cells grown in conditions of low CD40 stimulation had reduced expansion in the presence of LPS, suggesting that the reduced proliferation observed in LPS-supplemented cultures involved memory but not naïve B cells. Polyclonal activators such as CpG DNA have been shown to increase antigen-specific memory B-cell differentiation into plasma cells as a means to maintain serological memory for long periods of time.16 Lipopolysaccharide is also a polyclonal activator, at least for mouse B cells, so we tested whether an increase in antigen-specific antibody secretion could be detected in LPS-supplemented cultures.

Figure 2.

Effect of CD40 stimulation level on the proliferative response of human B cells to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Purified human B cells were cultured using a high (▪) or a low ( ) CD40 stimulation for 14 days, in the presence (solid line) or absence (dotted line) of 20 μg/ml Escherichia coli LPS. The number and viability of cells were evaluated by trypan blue exclusion counting. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

) CD40 stimulation for 14 days, in the presence (solid line) or absence (dotted line) of 20 μg/ml Escherichia coli LPS. The number and viability of cells were evaluated by trypan blue exclusion counting. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

Effect of LPS on antigen-specific antibody secretion

The B cells used in the cultures described above were derived from donors selected for the presence of TT-specific or HBsAg-specific antibodies in their plasma. We therefore measured the secretion of TT-specific and HBsAg-specific antibodies in these cultures. Results (Table 2) showed that, contrary to total IgG secretion, the secretion of antigen-specific antibodies was significantly increased in cultures supplemented with LPS (from 2 up to 34 times). This increase was not antigen-driven, because no antigen (TT or HBsAg) was added to the cultures. The increased secretion of antigen-specific antibodies did not influence significantly the total IgG secretion because antigen-specific antibodies represent only a minor proportion of the antibodies produced by cultured B cells (R. Lemieux and R. Bazin, unpublished observations). Such an increase in antigen-specific antibody secretion strongly suggested that the subpopulation undergoing differentiation in the presence of LPS was part of the memory B-cell subset.

Table 2.

Increased secretion of antigen-specific antibodies in presence of lipopolysaccharide

| Experiment | Total IgG (μg/106cells) | Ratio ‘A’ (+LPS/−LPS) | Antigen-specific IgG (OD/106cells)1 | Ratio ‘B’ (+LPS/−LPS) | Overall increase (Ratio B/A) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −LPS | 8·1 | 0·62 | 0·133 | 2·3 | 3·7 |

| +LPS | 5·0 | 0·306 | ||||

| 2 | −LPS | 9·2 | 0·84 | 0·032 | 1·7 | 2·0 |

| +LPS | 7·7 | 0·054 | ||||

| 3 | −LPS | 4·2 | 0·79 | 0·018 | 34·1 | 43·2 |

| +LPS | 3·3 | 0·613 | ||||

| 4 | −LPS | 5·3 | 0·32 | 0·012 | 9·3 | 29·1 |

| +LPS | 1·7 | 0·112 | ||||

| 5 | −LPS | 5·6 | 1·30 | 0·187 | 2·1 | 1·6 |

| +LPS | 7·3 | 0·390 | ||||

IgG, immunoglobulin G; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; OD, optical density.

Total IgG and tetanus toxin-specific (exp. 1, 2, 4 and 5) or hepatitis B surface antigen-specific (exp. 3) antibodies were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, after 10 days of culture in the presence or absence of LPS. The experiments were performed using B cells from three different donors.

The OD at similar dilutions of culture supernatants were used as a measure of the amount of antigen-specific antibodies and normalized by dividing with the cell number at day 10. Ratio ‘A’: relative increase : decrease in total IgG secretion in presence of LPS. Ratio ‘B’: relative increase in antigen-specific IgG secretion in presence of LPS. Ratio B/A : increase in antigen-specific IgG secretion among total IgG.

Increased IL-6 and IL-10 expression in LPS-supplemented cultures

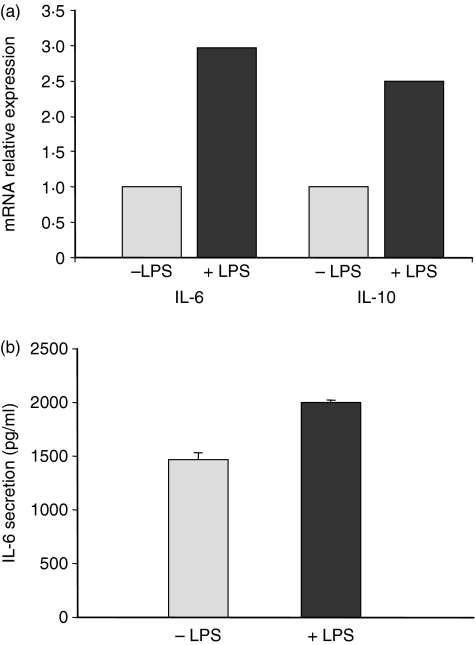

In addition to being a potent mitogen for mouse B cells, LPS has also been shown to induce the secretion of cytokines such as IL-1017 and transforming growth factor-β18 by these cells. We postulated that the increase in antigen-specific antibody secretion observed in LPS-supplemented human B-cell cultures could be the result of the secretion of cytokines able to induce memory B-cell differentiation into plasma cells, such as IL-6 and IL-10. We therefore measured the IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA levels in cultured human B cells by quantitative real-time PCR. Results showed a significant increase in IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA expression (two to three times) after 6 hr of culture in the presence of LPS compared to the control condition in the absence of LPS (Fig. 3a). This increase in mRNA expression was followed by an increase in IL-6 secretion evaluated after 3 days in LPS-supplemented cultures, as shown in Fig. 3b. It is likely that a similar increase in IL-10 secretion also occurred, although it could not be determined experimentally because IL-10 was already present (50 ng/ml) in the culture medium. The increase in IL-6 secretion (1·5 times) was less than the increase in IL-6 mRNA (two to three times), suggesting that a significant proportion of IL-6 was readily consumed by surrounding cells.

Figure 3.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-10 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression and secretion following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. (a) IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in human B cells, following a 6-hr stimulation with LPS and using GAPDH mRNA expression as an internal control. Relative expression was calculated using IL-6 mRNA expression in unstimulated B cells as the baseline. (b) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay quantification of IL-6 in culture supernatants of human B cells grown in the presence or absence of LPS for 3 days. B cells were from the same donor as for the IL-6 mRNA expression analysis. Results are representative of four separate experiments, with B cells from different donors.

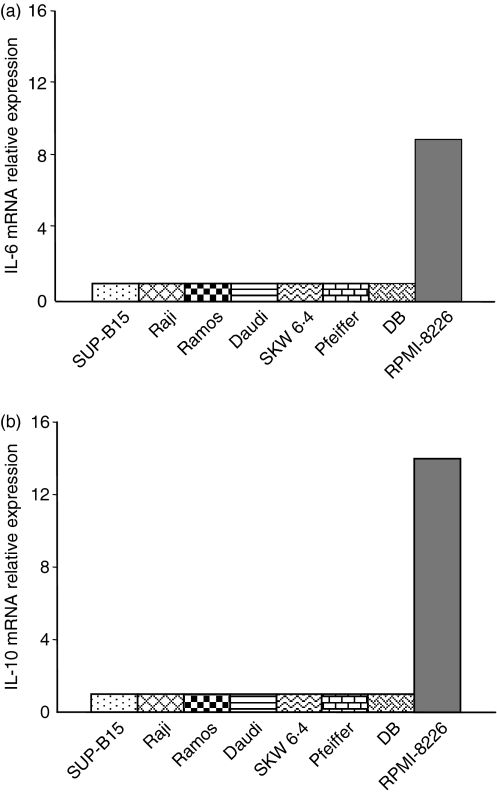

IL-6 and IL-10 expression by human B-cell lines following LPS stimulation

We were interested to determine whether all B cells or only a particular B-cell subset could respond to LPS by increasing cytokine secretion. Attempts to identify such cells by flow cytometry analysis of LPS receptor expression (TLR-4) or binding of LPS conjugated to a fluorescent dye in conjugation with B-cell subset-specific markers were unsuccessful (data not shown). We therefore used a series of eight human B-cell lines representing different stages of maturation, from pre-B cells to plasma cells to determine whether responsiveness to LPS could be related to a specific stage of B-cell maturation. Each cell line was cultured for 6 hr in the presence or absence of LPS and IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA levels were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR (Fig. 4). In the absence of LPS stimulation, none of the B-cell lines studied significantly expressed IL-6 or IL-10 mRNA (Ct > 35). After LPS stimulation, expression of IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA was induced only in the RPMI-8226 plasma cell line. Cytokine secretion by LPS-stimulated RPMI-8226 cells was confirmed by ELISA (data not shown). This result suggested that the B cells at or near the plasma cell differentiation stage were more responsive to LPS, resulting in an increase in cytokine secretion.

Figure 4.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-10 messenger RNA (mRNA) expression in human B-cell lines following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. SUP-B15 (pre-B), Raji, Ramos, Daudi, SKW6.4, Pfeiffer, DB (all mature B-cell lines expressing different surface markers) and RPMI-8226 (plasma cell) were cultured in the presence or absence of LPS for 6 hr, before IL-6 and IL-10 mRNA expression analysis by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. GAPDH mRNA expression was used as an internal control. Relative expression was calculated using IL-6 or IL-10 mRNA expression in unstimulated cells as the baseline.

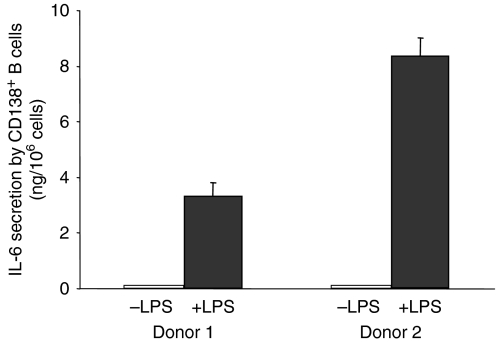

IL-6 secretion by CD138+ B cells following LPS stimulation

To confirm the effect of LPS on plasma cells, human CD138+ B cells were isolated by positive selection from purified resting B-cell populations and cultured for 2 days in the presence or absence of LPS. Interleukin-6 secretion was measured in the culture supernatants by ELISA. Results showed that CD138+ B cells cultured in the absence of LPS did not secrete detectable amounts of IL-6, whereas LPS-stimulated CD138+ B cells secreted significant amounts of IL-6 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion by purified CD138+ B cells following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation. CD138+ B cells were isolated from purified B cells using peripheral blood mononuclear cells from two different donors and cultured for 2 days as described in the Materials and Methods, in the presence or absence of LPS. Secretion of IL-6 was measured in the supernatants by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to evaluate the effects of LPS on CD40-activated human B cells. We showed that addition of LPS to human B cells resulted in a reduced expansion that could be correlated with an increase in antigen-specific secretion but not total antibody secretion. This observation demonstrates a direct effect of LPS on human B cells, although this effect differs from the well-characterized mitogenic effect of LPS on murine B cells. Our results also suggest co-operation between different B-cell subsets in the response to LPS, in which a first B-cell subset directly responds to LPS by increasing the secretion of cytokines such as IL-6, which subsequently trigger the differentiation of another B-cell subset. Part of this conclusion is based on the work done using human B-cell lines arrested at different stages of maturation. The RPMI-8226 plasma cell line was the only cell line among the eight cell lines tested that responded to LPS by significantly increasing IL-6 and IL-10 secretion. None of the mature B-cell lines expressing the CD27 memory cell marker (Raji, Ramos, Daudi, DB; Dr S. Néron, personal communication) were influenced by LPS, suggesting that mature memory B cells cannot directly respond to LPS. We further showed that normal CD138+ B cells responded to LPS by secreting significant amounts of IL-6. Although low numbers of CD138+ B cells are present in purified B-cell populations (usually < 5%) when cultures are initiated, their ability to respond to LPS very rapidly could influence the overall outcome of the culture. Whether other B-cell subsets are equally responsive to LPS remains to be determined.

It is well known that the response to LPS is mediated by binding to specific receptors, such as TLR-4. Although low TLR-4 expression could be detected on cultured B cells by flow cytometry (data not shown), it was not possible to associate this expression with a particular B-cell subset. Identification of TLR-4-expressing or LPS-binding B cells may indeed be difficult, because it is known that the level of expression of TLR-4 is low on B cells11 and because the putative target cells (B cells at or near the plasma stage) are not very abundant in the CD40–CD154 system, at least at or before day 7 when the increase in antigen-specific antibody secretion is already detectable. Concerning the low expression of TLR-4 on B cells, it should be noted that another LPS receptor (RP105) has recently been identified and shown to be preferentially expressed on mature B cells and to co-operate with TLR-4 in the LPS-induced B-cell activation.19,20 This receptor may therefore contribute to mediating the effects of LPS on B cells that were observed in the present study.

The significant and sometimes dramatic (34-fold for HBsAg) increases in the secretion of antigen-specific antibodies in the presence of LPS may be seen as surprising considering that the total amount of secreted antibodies was not significantly increased. However, it should be emphasized that the secretion of total or antigen-specific antibodies was not measured in comparable units (μg for total antibodies and optical density for antigen-specific antibodies). It is not easy to quantify the dose of antigen-specific antibodies that can yield the observed optical density, although it is likely to be in the picogram or nanogram range for high-affinity antibodies, given the high sensitivity of the ELISA. Since the total amount of secreted antibodies was in the 10-μg range (per 106 cells), it indicates that LPS could increase the secretion of antibodies with hundreds of different specificities (in addition to the assayed TT-specific and HBsAg-specific antibodies) without significantly affecting the total amount of antibodies secreted during the culture period. Alternatively, an inhibitory effect of LPS on the secretion of some populations of antibodies cannot be ruled out.

Although the precise identity of the cells responsible for the increased IL-6 and IL-10 expression in LPS-supplemented B-cell cultures is still speculative, but certainly includes CD138+ B cells, the increase in antigen-specific secretion, but not total antibody secretion, strongly suggests that only a small B-cell subset was induced to differentiate in response to IL-6. Even though IL-10 mRNA expression was also increased in LPS-supplemented cultures, it is unlikely that this cytokine could have contributed to the antigen-specific B-cell differentiation observed in the CD40–CD154 system, because IL-10 was already present in the culture medium at a concentration of 50 ng/ml, which is much higher than the reported endogenous production (0·3–0·4 ng/ml),21 even after the two- to threefold increase observed in mRNA expression after LPS stimulation. Susceptible B cells must therefore express the IL-6 receptor. The IL-6 receptor is composed of two molecules, CD126 which specifically binds IL-6 and CD130, a common signal transduction unit used by several cytokines and responsible for signal transduction after binding to the CD126/IL-6 complex.22,23 Although we speculate that B cells at or the near plasma cell stage are responsible for differentiation-inducing cytokine secretion, they would not be likely to use IL-6 in an autocrine way because normal human plasma cells do not express CD126.24 A recent analysis of the expression of CD126 on peripheral blood B cells revealed that CD126 expression was completely restricted to CD27+ memory B cells (with the exception of a small population of CD27− IgG+ memory B cells).25 Expression of CD126 was variable even within the CD27+ IgG+ compartment, which represents about 7% of total B cells, with significant expression on 23% of the cells only. Therefore, only a small proportion of the total memory B-cell pool is likely to be responsible for the increased secretion of antigen-specific antibodies observed as early as the 7th day in LPS-stimulated cultures.

It is known that there is a wide variation in the individual response to infection that may be related to genetic polymorphisms.26 For example, there is a great interindividual variability in the response to bacterial products such as LPS. This variability has been associated with differences in gene expression between low and high LPS responders.27 In the present study, we also observed a difference in responsiveness to LPS for B cells from some donors for which there was no effect of LPS on expansion. This lack of effect may be because of the inability of the B cells from these donors to increase cytokine secretion in response to LPS, possibly because of insufficient numbers of CD138+ (or other LPS-responsive) B cells in the starting B-cell population, with the subsequent absence of effect on B-cell differentiation. Further characterization of the LPS-resistant cultured B cells may permit clarification of the mechanism involved.

In conclusion, this work revealed a functional interaction between LPS and human B cells which induced B cells to secrete cytokines. Although this activity was revealed in an in vitro culture system and resulted in the differentiation of some B cells, the physiological significance of the effects of LPS on human B cells may not be limited to increased B-cell differentiation. Indeed, IL-6 is known to have many effects on a number of different cells in addition to its role as a B-cell differentiation factor.28 Secretion of IL-6 by human B cells in response to LPS may help to sustain a local ongoing immune response to invading Gram-negative bacteria, until all pathogens have been cleared from the organism.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Sonia Néron for critical review of the manuscript and Chantal Roberge for excellent technical assistance.

References

- 1.Noelle RJ, Snow EC. Cognate interactions between helper T cells and B cells. Immunol Today. 1990;11:361–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90142-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop GA, Hostager BS. B lymphocyte activation by contact-mediated interactions with T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2001;13:278–85. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banchereau J, Bazan F, Blanchard D, et al. The CD40 antigen and its ligand. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:881–922. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray D, Siepmann K, Wohlleben G. CD40 ligation in B cell activation, isotype switching and memory development. Semin Immunol. 1994;6:303–10. doi: 10.1006/smim.1994.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banchereau J, de PaoliP, Valle A, Garcia E, Rousset F. Long-term human B cell lines dependent on interleukin-4 and antibody to CD40. Science. 1991;251:70–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1702555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neron S, Pelletier A, Chevrier MC, Monier G, Lemieux R, Darveau A. Induction of LFA-1 independent human B cell proliferation and differentiation by binding of CD40 with its ligand. Immunol Invest. 1996;25:79–89. doi: 10.3109/08820139609059292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;438:364–8. doi: 10.1038/nature04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coutinho A, Gronowicz E, Bullock WW, Moller G. Mechanism of thymus-independent immunocyte triggering. Mitogenic activation of B cells results in specific immune responses. J Exp Med. 1974;139:74–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Applequist SE, Wallin RP, Ljunggren HG. Variable expression of Toll-like receptor in murine innate and adaptive immune cell lines. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1065–74. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruprecht CR, Lanzavecchia A. Toll-like receptor stimulation as a third signal required for activation of human naive B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:810–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernasconi NL, Onai N, Lanzavecchia A. A role for Toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: up-regulation of TLR9 by BCR triggering in naive B cells and constitutive expression in memory B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4500–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mita Y, Dobashi K, Endou K, Kawata T, Shimizu Y, Nakazawa T, Mori M. Toll-like receptor 4 surface expression on human monocytes and B cells is modulated by IL-2 and IL-4. Immunol Lett. 2002;81:71–5. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neron S, Thibault L, Dussault N, Cote G, Ducas E, Pineault N, Roy A. Characterization of mononuclear cells remaining in the leukoreduction system chambers of apheresis instruments after routine platelet collection: a new source of viable human blood cells. Transfusion. 2007;47:1042–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neron S, Racine C, Roy A, Guerin M. Differential responses of human B-lymphocyte subpopulations to graded levels of CD40–CD154 interaction. Immunology. 2005;116:454–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fecteau JF, Neron S. CD40 stimulation of human peripheral B lymphocytes: distinct response from naive and memory cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:4621–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dalwadi H, Wei B, Schrage M, Spicher K, Su TT, Birnbaumer L, Rawlings DJ, Braun J. B cell developmental requirement for the G alpha i2 gene. J Immunol. 2003;170:1707–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tian J, Zekzer D, Hanssen L, Lu Y, Olcott A, Kaufman DL. Lipopolysaccharide-activated B cells down-regulate Th1 immunity and prevent autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:1081–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miura Y, Shimazu R, Miyake K, Akashi S, Ogata H, Yamashita Y, Narisawa Y, Kimoto M. RP105 is associated with MD-1 and transmits an activation signal in human B cells. Blood. 1998;92:2815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogata H, Su I, Miyake K, et al. The toll-like receptor protein RP105 regulates lipopolysaccharide signaling in B cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:23–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burdin N, Peronne C, Banchereau J, Rousset F. Epstein–Barr virus transformation induces B lymphocytes to produce human interleukin 10. J Exp Med. 1993;177:295–304. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamasaki K, Taga T, Hirata Y, et al. Cloning and expression of the human interleukin-6 (BSF-2/IFN beta 2) receptor. Science. 1988;241:825–8. doi: 10.1126/science.3136546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibi M, Murakami M, Saito M, Hirano T, Taga T, Kishimoto T. Molecular cloning and expression of an IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. Cell. 1990;63:1149–57. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rawstron AC, Fenton JA, Ashcroft J, et al. The interleukin-6 receptor alpha-chain (CD126) is expressed by neoplastic but not normal plasma cells. Blood. 2000;96:3880–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fecteau JF, Cote G, Neron S. A new memory CD27– IgG+ B cell population in peripheral blood expressing VH genes with low frequency of somatic mutation. J Immunol. 2006;177:3728–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes CL, Russell JA, Walley KR. Genetic polymorphisms in sepsis and septic shock: role in prognosis and potential for therapy. Chest. 2003;124:1103–15. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wurfel MM, Park WY, Radella F, Ruzinski J, Sandstrom A, Strout J, Bumgarner RE, Martin TR. Identification of high and low responders to lipopolysaccharide in normal subjects: an unbiased approach to identify modulators of innate immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175:2570–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.4.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Snick J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:253–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.001345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]