Abstract

The centromeric and telomeric heterochromatin of eukaryotic chromosomes is mainly composed of middle-repetitive elements, such as transposable elements and tandemly repeated DNA sequences. Because of this repetitive nature, Whole Genome Shotgun Projects have failed in sequencing these regions. We describe a novel kind of transposon-based approach for sequencing highly repetitive DNA sequences in BAC clones. The key to this strategy relies on physical mapping the precise position of the transposon insertion, which enables the correct assembly of the repeated DNA. We have applied this strategy to a clone from the centromeric region of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. The analysis of the complete sequence of this clone has allowed us to prove that this centromeric region evolved from a telomere, possibly after a pericentric inversion of an ancestral telocentric chromosome. Our results confirm that the use of transposon-mediated sequencing, including positional mapping information, improves current finishing strategies. The strategy we describe could be a universal approach to resolving the heterochromatic regions of eukaryotic genomes.

INTRODUCTION

The centromeric and telomeric heterochromatin of eukaryotic chromosomes is mainly composed of middle-repetitive elements, such as transposable elements, and tandemly repeated DNA sequences. As these chromosomal regions play an important role in chromosome segregation and nuclear architecture, a comprehensive description of their sequences is essential for understanding chromosome behavior and chromosome evolution.

Recently, the Drosophila Heterochromatin Genome Project has shown that current shotgun strategies are capable of determining high-quality contiguous sequence of heterochromatic regions with a high density of transposable elements, but not of regions containing satellite DNA repeats (1). Likewise, in all ‘finished’ genomes, there are many heterochromatic regions, including all the centromeres, not yet sequenced. Sequencing such regions is likely to rely on both an understanding of the structural organization of centromeric regions and the development of special approaches to sequence individual large-insert clones (2).

Although BAC clones may be sequenced efficiently using shotgun-based sequencing strategies, in many cases when the insert is repetitive DNA, shotgun techniques fail. The reasons are varied: difficulties in the subcloning, elimination of certain repetitive sequences, rearrangements and principally, uncertainties in the final assembly process. At present, despite the substantial efforts made by specialized sequence finishing groups, the highly repetitive heterochromatin regions of genomes remain unfinished.

Currently, transposon-mediated sequencing is broadly used as an effective alternative to classical shotgun strategies, since it simplifies the making of clone libraries. However, no benefit has yet been derived from one of the most potentially powerful tools for sequencing by transposon: the possibility of mapping the position of the transposon insertion (3). Therefore, it is important to test whether a transposon-based sequencing strategy using positional information is an effective approach to the sequencing of large-insert heterochromatic clones.

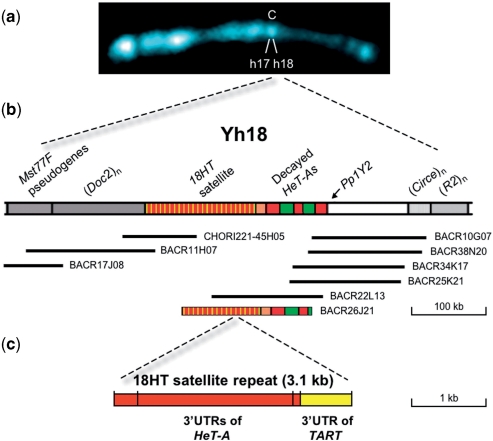

Drosophila maintains its telomeres by occasional targeted transposition of telomere-specific non-LTR retrotransposons (HeT-A, TART and TAHRE in the D. melanogaster subgroup) to chromosome ends, and not by the more common mechanism of telomerase-generated G-rich repeats (4–8). However, arrays of telomeric elements have been found in centromeric and pericentromeric heterochromatin (9–15). The centromeric region of the Y chromosome of D. melanogaster comprises the heterochromatic bands h17–h18. Past cytomolecular studies of the region h18 showed that it contains a tandem array of HeT-A- and TART-related sequences, collectively named the 18HT satellite, as well as several degenerate HeT-A elements (Figure 1) (13). The discovery of telomeric retrotransposons at this centromeric site led to the suggestion that the centromere of the Y was derived from a telomere by an intra-chromosomal rearrangement (13,16). In support of this hypothesis, Berloco and collaborators (15) have found HeT-A-related sequences in the centromeric region of the Y chromosome of all species analyzed, independently of the position of the centromere within these chromosomes.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the Y centromeric region h18 encompassing the 18HT satellite. (a) Prometaphase Y chromosome counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The centromere is indicated with a C and the regions h17 and h18 are also indicated. (b) Schematic representation of region h18 showing the 18HT satellite and the extent of the assembled contig. The position of the gene Pp1Y2, the pseudogenes Mst77F and some retrotransposons are also indicated. The names of the BACs are indicated. BACR26J21 appears at the bottom. (c) Structural organization of the 18 HT satellite repeat unit. The 3.1-kb tandem repeat unit contains three truncated 3′ UTRs of HeT-A and one truncated 3′ UTR of TART.

Since the initial finding of telomeric sequences in the centromeric region of the D. melanogaster Y chromosome, we have been working towards the determination of the sequence of this region. Once BACs from region h18 were identified (14), BACR26J21 was selected because it contains both 18HT satellite repeats and degenerate HeT-A elements. In addition, BACR26J21 represents the typical problematic heterochromatic BAC, making it an ideal candidate to test our transposon-based sequencing strategy.

We conclude that the use of transposon-mediated sequencing, including positional mapping information, allows a substantial improvement of the current finishing strategies. This could become a universal approach to resolving the heterochromatic regions of the genomes. Importantly, the complete sequence of this clone has allowed us to prove that this centromeric region evolved from a telomere, possibly after a pericentric inversion of an ancestral telocentric chromosome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and reagents

Bacterial cultures were grown in LB broth supplemented with 1.5% agar when appropriate. SOC medium (2% bacto-tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 10 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MgSO4, 20 mM glucose) was used for recovery of cells following electroporation.

Restriction enzymes and T4 ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA) and Promega (Madison, WI). All oligonucleotides were purchased from Isogen (IJsselstein, The Netherlands). The pMOD<oriV/KAN-2> transposon construction vector was a generous gift from Epicentre (Madison, WI).

Qiagen (Valencia, CA) products were used for plasmid purification and DNA gel extraction. Hyperactive mutant Tn5 transposase, carrying the mutations EK54/MA56/LP372 (17), was a generous gift from W. S. Reznikoff.

Construction of plasmids carrying artificial transposons

To obtain the pMOD2<oriV/KAN-2/I-SceI> vector, a 0.6-kb EcoRI–SalI fragment containing the recognition sequence for I-SceI was prepared from pSCM522 (18), blunted, gel-purified, and ligated to HindIII-digested, blunted and dephosphorylated pMOD2<oriV/KAN-2>. A 0.75-kb HindIII–PstI fragment containing the recognition sequence for PI-SceI was prepared from pBSVDEX (19), blunted, gel-purified and ligated to SacI-digested, blunted and dephosphorylated pMOD2<oriV/KAN-2/I-SceI>, resulting in pMOD2<oriV/KAN-2/I-SceI/PI-SceI> vector (pJW599) constructed by J.W. (Supplementary Figure 1a).

Integration of Tn5-like transposons into BAC DNA

Transposome complexes were formed by incubating 1 μg of the 3.3-kb PshAI-released transposon DNA from plasmid pJW599 (Supplementary Figure 1b) with 10 μg/μl of hyperactive mutant Tn5 transposase for 2 h at 37°C in 40 μl of a buffer containing 50 mM Tris–acetate (pH 7.5), 150 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate and 4 mM spermidine. Transposition reactions were carried out by incubating 14 μl of transposon–transposase complexes with 1 μg of BACR26J21 DNA for 2 h at 37°C in a 20 μl reaction volume. Reactions were stopped with 0.1% SDS and 10 min incubation at 70°C. The transposon–transposase complexes were desalted on agarose cones and transformed into EPI300T1R cells (Epicentre, Madison, WI) by electroporation. Cells were plated on LB medium containing 30 μg/ml of kanamycin and 12.5 μg/ml of chloramphenicol. Around 2500 transformants were obtained in a single experiment (Figure 2a-1).

Figure 2.

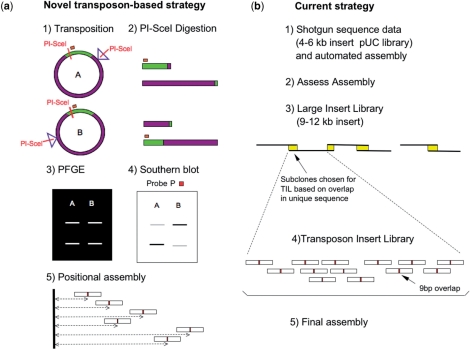

Clone-based strategies to sequence highly repetitive regions. (a) Novel transposon-based strategy [see also Szybalski et al. (36)]. (1) In vitro transposition of Tn599 into BACR26J21 generates a library of clones that carry this transposon at random positions. A and B represent clones where Tn599 is inserted at different positions. (2) PI-SceI digestion of each clone generates two DNA fragments. (3) In the case of A and B, the two sets of fragments are identical in size, as can be seen in the PFGE image. (4) In order to distinguish between the two putative positions of the transposon in the clone, a Southern blot analysis is performed, using the probe P, that marks the fragment that carries most of the vector used in the construction of the BAC library. (5) Sequencing of each clone is performed using two primers reading outwards from both ends of the transposon. The reads are then assembled using both positional and sequence data. (b) Current strategy. (1) Collect shotgun sequence data and assemble the data into sequence contigs using computer programs. (2) Assess the likelihood of resolution before committing to the LIL-TIL strategy. (3) Generation of a Large Insert Library. Large insert subclones are then chosen for TIL based on overlap in sequence believed to occur only once in the clone. The diagram illustrates how, by choosing a number of subclones that overlap in unique sequence, a minimum tile path can be built to correctly assemble large sections of repeats. (4) Build each LIL subclone using a Transposon Insert Library (TIL). (5) Combination of the LIL-TIL strategy, existing read-pair information and restriction digest data to build a correct assembly.

Induction of oriV-controlled replication and DNA extraction

Overnight cultures grown in LB supplemented with 30 μg/ml kanamycin and 12.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol were used to inoculate fresh cultures that were grown in the same medium. At an A590 = 0.2–0.3, l-arabinose inducer was added to the final concentration of 0.01% and cultures were grown for an additional 4–5 h before the cells were harvested. DNA from the induced recombinant BACs carrying transposon insertions was prepared by the alkaline lysis method with the R.E.A.L. Prep 96 (Quiagen. Valencia, CA).

Mapping of Tn599 transposon insertions

To determine the position of the transposon insertion, each clone was digested with PI-SceI (Figure 2a-2). In each clone there are two PI-SceI recognition sites: one of them is at a fixed position in the vector used to construct the RPCI-98 library, and the other is the one we have introduced in the transposon Tn599. After digestion of the clones, two fragments were generated and fractionated by PFGE in a CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). 1% (w/v) agarose gels were run in 0.5× TAE (1× TAE is 40 mM Tris–acetate/2 mM EDTA) at 6V/cm, 14°C for 20 h with a pulse time ramp from 0.4–10 s (Figure 2a-3). However, in order to distinguish the two fragments, the DNA from the PFG was transferred to a Hybond™-N+ nylon membrane and hybridized with probe P (Figure 2a-4). This probe derived from a region of the plasmid vector used to construct the BAC library and was obtained by PCR using pBACe3.6 DNA as a template, the primers P-Fw: 5′ AAGGCCGTAATATCCAGCTG 3′ and P-Rv: 5′ CTTCGTGTAGACTTCCGTTG 3′ and the following cycling parameters: an initial denaturalization step at 94°C for 5 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min; 55°C for 30 s; 72°C for 1 min followed by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The obtained PCR product was labeled with [32P] dCTP using ‘Rad prime DNA radiolabeling kit’ (Invitrogen) according to supplier's recommendations. Figure 2a-1 displays an example where two clones with the transposon inserted at different positions, generate (after PI-SceI digestion) two sets of fragments of the same two sizes (Figure 2a-2). Taking the sizes alone one could not distinguish the relative position of the transposon from the fixed PI-SceI recognition site. It was only after hybridization with the probe P that one could discern the two fragments, and thus, place them in the correct order (Figure 2a-4).

Sequencing and sequence assembly

Transposon-based DNA sequencing was performed using the standard dye terminator chemistry with two different primers; TN-FP (5′-GCCAACGACTACGCACTAGCCAAC-3′) and TN-RP (5′-GAGCCAATATGCGAGAACACCCGAGAA-3′). The following PCR cycling parameters were used: initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s; 55°C for 20 s; 60°C for 4 min, followed by a final extension step at 60°C for 5 min. Reactions were analyzed in an ABI Prism 3730 Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at the sequencing facility of the Unidad de Genómica Antonia Martín Gallardo, PCM-UAM.

Sequence assembly of the transposon-based sequencing approach was carried out using preGap4 and Gap4 assembly tools, from the Staden package (20). After the sequences were clipped for transposon's ME, each mate pair was linked by aligning the 9-bp duplicated region, and minicontigs for each clone, of around 1500 bases long, were built. This union is very important when dealing with highly similar repetitive sequences (>99% identity among different repeat units), since it provides longer reads, where single nucleotide differences are more likely to show up, narrowing the chances of misassemblies. Then small assembly projects were generated separately for eight windows of 20 kb. The size of the window was decided considering that PFGE fragment size measurement is associated with an inevitable error. Each minicontig was placed in one subproject, according to its Tn599 insertion position. In each small project, assembly was done by sequence overlap, still bearing in mind the relative position within the window. Afterward, each subproject was joined to its neighbor subproject, and assembled by sequence overlap until all sequences had been assembled together into a single contig (Figure 2a-5). For the final sequence (FM992409), 933 reads (with an average read length of 817 nucleotides per read) were assembled, giving 4.7-fold coverage of BACR26J21.

The strategy used at The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute for sequencing and finishing repetitive clones was the following: the clone BACR26J21 was shotgunned using a 4–6-kb pUC subclone library and an assembly was produced using Phrap (Philip Green) (Figure 2b-1). Gap4 (20), Orchid (Flowers) and Confirm (Attwood) were then used to assess the integrity of the assembly (Figure 2b-2). Where misassemblies occurred in the repeat, copies were compared against each other and base pair differences were identified and tagged. These differences were then used to identify regions of unique sequence within the repeat. Using paired read information it is often possible to then position reads accurately based on their overlap in unique sequence to contiguate the clone. Because this approach was not sufficient in the case of BACR26J21, a LIL–TIL strategy was employed. The LIL–TIL strategy involves the generation of a Large Insert Library (LIL), which is then combined with the existing data (Figure 2b-3). Large insert subclones (9–12 kb) are then chosen to generate a Transposon Insert Library (TIL), based on overlap in sequence believed to occur only once in the clone (assuming roughly uniform shotgun coverage). TILs were generated using a kit-based approach (Figure 2b-4). Transposons randomly inserted into the subclone were sequenced outwards from the transposon insertion site. TIL read-pairs were then joined up based on the 9-bp duplication site to give contiguous TIL read-pairs in excess of 1 kb. The combination of the LIL-TIL strategy, existing read-pair information and restriction digest data was used to build a correct assembly (Figure 2b-5). For the final sequence (CU076040) 6354 reads (with an average read length of 872 nucleotides per read) were assembled, giving12.2-fold coverage of BACR26J21.

Sequence analysis

The BACR26J21 assembled sequence was analyzed by BLAST through the FlyBase server (http://flybase.bio.indiana.edu) and by dot plot analyses using Dotter (21). The comparison of the two independent sequences for BACR26J21 was carried out by BLAST2.

RESULTS

Transposon requirements

In order to develop a technique for successful sequencing, in an automated manner, of any large heterochromatic insert clone, we modified an existing transposon used for sequencing. Most vectors used in the construction of BAC libraries contain a homing endonuclease recognition site to provide a tool for linearization (http://bacpac.chori.org/vectorsdet.htm). The introduction of the same recognition site into the transposon facilitates the mapping of its insertion by measuring the two fragments generated by a single digestion. Combining the positional information and the sequence data at the assembly stage, similar sequences that derive from different positions within the repetitive DNA would never be assembled together.

Our method relies on the use of a Tn5-like transposon to generate, in vitro, a library of clones, with the transposon inserted randomly along the entire length of the sequence of interest (22). Since repetitive sequences are rather unstable, a single-copy-number clone (BAC) is necessary. However, BACs have the disadvantage of a very low yield of DNA. Therefore, for the construction of the transposon, we have used the plasmid pMOD2<oriV/KAN-2> that carried the inducible origin of replication oriV, which, only upon production of TrfA in the host cell, transforms the clone from single-copy to multiple copies [for advantages of this system see Wild et al. (23)].

To allow the mapping of the insertion we have implemented the transposon with two rare sites, PI-SceI and I-SceI. These double stranded DNAses are extremely unusual in that they have large recognition sites (18 bp for I-SceI and 39 bp for PI-SceI). For instance, an 18-bp recognition sequence will occur only once in every 7 × 1010 bp of random sequence, which is equivalent to only one site in 20 mammalian-sized genomes (24). However, unlike standard restriction endonucleases, homing endonucleases tolerate some sequence degeneracy within their recognition sequence (25,26). In any case, the chance of finding their recognition sites in the target sequence of a large insert clone is extremely low. This makes the mapping strategy universal, independent of the nature of the genome DNA being used.

Taking all these facts into consideration, the plasmid construction was carried out as described in Methods, producing the final plasmid pMOD2<oriV/KAN-2/I-SceI/PI-SceI>, from which the artificial transposon Tn599 was obtained by digestion with the restriction enzyme PshAI. In summary, the final transposon comprised the following significant traits: (i) two mosaic-end (ME) sequences at the ends of the transposon [necessary for the transposon to be able to integrate (27)], (ii) known sequences adjacent to the ME, that serve as priming sites for sequencing the insert region contiguous to the transposon, (iii) a kanamycin-resistance gene, (iv) an inducible origin of replication, oriV, (v) a recognition site for I-SceI and (vi) a recognition site for PI-SceI (Supplementary Figure 1).

An optimized transposon-based strategy for sequencing highly repetitive DNA

To test whether our novel strategy improves upon the standard shotgun sequencing and directed finishing approach, a challenging BAC from the RPCI-98 D. melanogaster BAC Library was independently sequenced by both procedures. The cloning vector used in the construction of this library was pBACe3.6, which has a PI-SceI recognizion site at its position 11371–11407 (http://bacpac.chori.org/vectorsdet.htm). We chose BACR26J21 based on our previous physical analyses of the centromeric region h18 of the Y chromosome (Figure 1). According to our data, BACR26J21 should carry about 100 kb of 18HT satellite repeats and decayed HeT-As elements interspersed with transposable elements (13,14). The length of the insert of BACR26J21 was estimated to be around 160 kb.

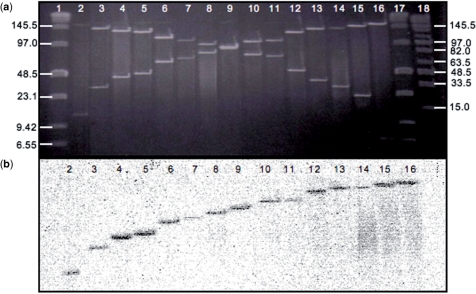

The optimized transposon-based strategy consisted of: (i) in vitro transposition of Tn599 into the BAC clone (Figure 2a-1), (ii) physical mapping of 620 clones from the transposon insertion library, which provides around 5-fold coverage of the clone (Figure 2a-2–4, see Methods section) and (iii) sequencing and assembly using the positional information (Figure 2a-5). Figure 3a and b display an example of the information required for correct mapping of the transposon in each clone. Figure 3a is the image of a PFGE gel with PI-SceI-digested DNA, and Figure 3b displays the same DNA hybridized to the radioactive labeled probe P.

Figure 3.

Mapping of the Tn599 insertions. (a) PFGE image of a set of clones (lanes 2–16) carrying the transposon, after digestion with PI-SceI. (b) Corresponding Southern blot hybridized with labeled probe. Data from (a) and (b) together allows the correct mapping of the transposon in each clone. Lanes 1 and 17 corresponds to Low Range PFGE Marker (NEB) and Lane 18 is Mid Range I PFGE Marker (NEB). Run conditions were 6 V/cm, 14°C for 20 h and a pulse time ramp of 0.4–10 s.

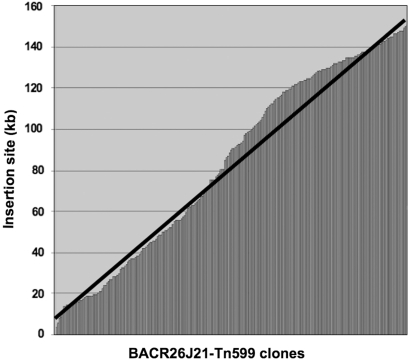

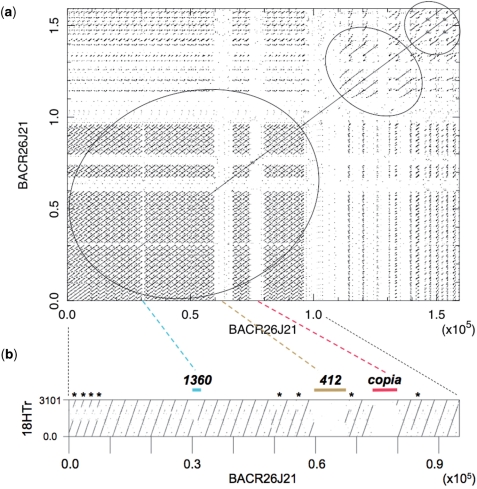

Although Kang and collaborators (22) observed randomness of the Tn5 transposition in the Escherichia coli genome, we decided to check the randomness of insertion of our Tn599 transposon into the highly repetitive DNA. In Figure 4 we have represented, in the x-axis, all the mapped BACR26J21-Tn599 clones and in the y-axis their correspondent sizes. As can be seen, the distribution of Tn599 insertions was even along the entire heterochromatic BACR26J21 (perfect randomness is represented by a black line). Thus, it seems that Tn5-like transposons can also be used to sequence heterochromatic BACs with satellite regions.

Figure 4.

Distribution of 620 insertions of Tn599 along the BACR26J21 is represented on the horizontal axis of the graph. Positions of the insertion sites within the BAC clone are shown in the vertical axis. The black line represents perfect randomness in the distribution of the insertions.

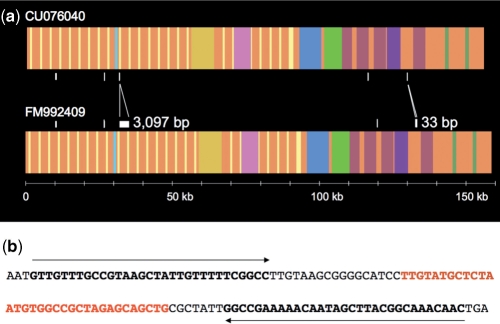

BLAST2 comparison of the two independent sequences of BACR26J21 obtained by the two sequencing approaches (CU076040 and FM992409) shows them to be nearly identical (Figure 5a). There are seven single-nucleotide differences, two additional A's in a poly(A), 33 extra nucleotides in the non-repeat region of the BAC clone and 3097 extra nucleotides in the tandem repeated region. The 33 extra nucleotides are present in the middle of a small palindrome within a HeT-A element. These 33 nucleotides correspond to the expected ones for such a position in the canonical HeT-A element (Figure 5b). The 3097 extra nucleotides in the tandem repeat region correspond exactly with one additional 18HT repeat unit. The standard restriction digest data, used as a quality control, does not provide enough information to be able to discern in tandem repeated regions. As the optimized transposon-based approach contains positional information, it seems reasonable to consider its consensus sequence to be more reliable.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of the two sequence assemblies of BACR26J21. (a) Diagram showing the location of the nucleotide differences between the assemblies (CU076040 versus FM992409). The assembly that utilizes positional information appears at the bottom (FM992409). In order to facilitate the comparison, different colors are given to different transposons. (b) Sequence showing that the extra 33 nucleotides (in red) are located in the middle of a 31-bp palindrome (in black bold).

Overall organization of the newly acquired sequence from the centromeric region h18 of the D. melanogaster Y chromosome and parsimonious reconstruction of its evolution

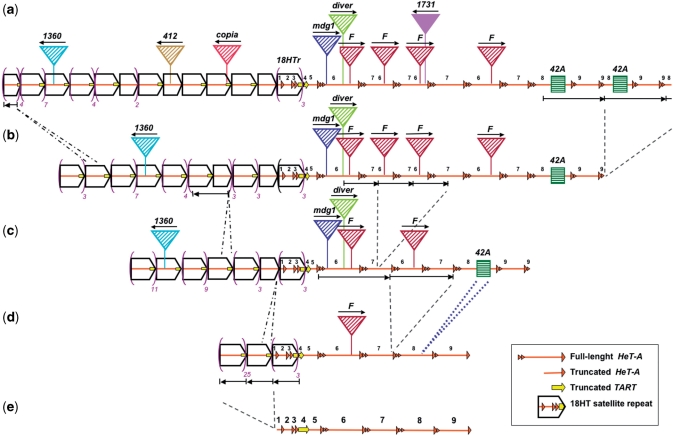

Dot plot analyses of the sequence obtained for BACR26J21 show, as we anticipated, that around two thirds of the insert corresponds to tandem repeats (large circle in Figure 6a). Specifically, this repeated region contains 29 18HT satellite repeats (Figure 6b). Looking at the transition between the 18HT repeats and the decayed telomeric elements, we were able to precisely determine the DNA region that underwent amplification, generating the more abundant 3.1-kb repeat unit (Supplementary Data). In addition, three types of smaller repeats (around 2 kb) were also detected (see asterisks in Figure 6b). These repeats were probably generated by major deletions, and two of them subsequently amplified by unequal crossovers (Figure 7d to a). Along the repeats we found three transposons: 1360, 412 and copia with 95%, 99% and 99% nucleotide identity to the canonical elements, respectively (Figures 6b and 7a). After the satellite repeats we found degenerated HeT-A elements (87% nucleotide identity), interspersed with several transposable elements: one mdg1, one diver, one 1731 and four F-elements with 95%, 96%, 100% and 97% nucleotide identity, respectively. We also found a small segmental duplication from the euchromatic region 42A present at two different sites at the distal end of the sequence (Figure 7a). These observations showed that, in addition to deletions and transposon insertions, several regions, indicated by circles in Figure 6a, had gone through amplification events. Thus, based on regional sequence homology, the four F-elements appear to derive from a single transposition event, and the region where it was inserted would have been subsequently amplified. The same would have happened to the region containing the duplication from 42A. (Figure 7 and Supplementary Data).

Figure 6.

Sequence analyses of BACR26J21. (a) Self comparison of the BACR26J21 sequence shows the presence of tandem repeat sequences. Circles indicate the positions of tandem repeated sequences (b) Dot plot analysis of the first 95 kb of BACR26J21 (x-axis) against the 3.1-kb sequence of the repeat unit of the 18 HT satellite (y-axis) generated using Dotter (21). Asterisks indicate the positions of deleted units. The positions of the transposons 1360, 412 and copia are also indicated. Numbering is in base pairs.

Figure 7.

Parsimonious reconstruction of the evolution of the centromeric region of the Y chromosome of D. melanogaster. (a) Schematic representation of the sequence of the centromeric region h18 of the Y chromosome, not to scale. The sequence of BACR26J21 was analyzed by BLAST through FlyBase and by dot plot analyses. Slim orange arrows represent HeT-As decayed by deletions and/or few small inversions. A yellow arrow (or fragment of it) represents 3′ UTR TART sequences. Pentagons (rightward open arrowheads) including HeT-A and TART sequences represent units of the 18HT satellite (Figure 1c). Each colored triangle represents a different transposon, with its orientation indicated by a thin black arrow, and its name displayed on top. All transposable elements are degenerate in comparison to the canonical element (http://flybase.org/), except 1731, which has been recently inserted. Green squares represent a small segmental duplication from the euchromatic region 42A. (e) to (a) is the order of the inferred evolutionary steps. Amplifications and deletions of various regions are indicated by two different types of discontinuous lines. For example, the region including sequences of four telomeric elements went through amplification, giving rise to the 18HT satellite, (e) to (d). Insertions of transposable elements are shown with triangles and the insertion of the sequence from 42A is indicated by a blue dotted line, (d) to (c). The outcome of three deletion events within the units of the 18HT satellite is indicated by contraction of the pentagon, (c) to (a). Violet parentheses have been used to reduce the diagram of the 18HT satellite region. (e) Schematic representation of the ancestral telomeric region. The telomeric array was composed of nine different telomeric elements, numbered from 1 to 9: four truncated HeT-As (1, 2, 3 and 5), one truncated TART (4) and four full-length HeT-As (6, 7, 8 and 9). Numbers have been preserved all along the scheme in order to help visualize the amplified regions.

Although the evolution of this chromosomal region could have followed an intricate path, the most parsimonious reconstruction suggests that the ancestral structure was a head-to-tail array of nine telomeric elements: four truncated HeT-As (elements 1, 2, 3 and 5 in Figure 7e), one truncated TART (element 4) and four full-length HeT-As (elements 6, 7, 8 and 9). The HeT-As 1, 2 and 3 and part of the TART element conformed the 3.1-kb segment that was originally amplified to form the 18HT satellite, which had already been described (10,13). We know that four of the HeT-As are full-length because for each of them we see its ORF sequence, its 3′ UTR sequence and in its most 5′UTR region we can even see the characteristic short sequences that derive from the 3′ end of the upstream element to the master copy from which each HeT-A element was retrotranscribed (28). In fact, it is the difference in the number and composition of these short sequences at the 5′UTR that has been used to distinguish among the HeT-A elements. There are several aspects of the reconstructed ancestral telomeric array that make it resemble a current Drosophila telomere. First of all, the existence of complete HeT-A elements is a typical feature of D. melanogaster telomeres (29,30). Second, the head-to-tail orientation of the telomeric retrotransposons is also a characteristic feature of telomeric arrays. Third, the reconstructed ancestral telomeric array has a similar length to the ones found at present Drosophila telomeres (29,30). For all these evidences we claim that this centromeric region has a large array of telomeric retrotransposons, and thus, that it evolved from an ancestral telomere.

DISCUSSION

The possibility of sequencing tandemly repeated regions by the presented transposon-based approach represents major progress in the development of a universal technique that will enable the characterization of the centromeres of eukaryotic genomes.

Although the sequences obtained by the two approaches are similar, the use of positional information reduces the number of reads required. Thus, the optimized transposon-mediated sequencing method needed seven times less sequences than the currently used strategy (933 reads versus 6354 reads), which represents a decrease in the cost. In addition, it is important to highlight that the final assembly of the highly repetitive DNA in BACR26J21 was achieved by the presented optimized method with coverage as low as 4.7-fold, thanks to the inclusion of positional information. When comparing the coverage obtained by both methods (4.7-fold versus 12.2-fold), the current method coverage is only increased 2.6 times (while the number of reads used was seven times larger). This means that the presented transposon method generates a less piled up assembly where the reads were distributed more homogeneously along the sequence. Taken altogether, these observations show the optimized transposon-mediated strategy to be a very effective and efficient method for sequencing highly repetitive regions.

The potential of this technique resides in the feasible automation of the transposon insertion mapping. We envision that the sizes of the PI-SceI-digested fragments can be easily measured with high resolution by optical mapping (31). This technique would serve not only to measure the sizes but also to make the necessary distinction between the two fragments. Instead of using probes to hybridize and mark one of the fragments upon measuring the sizes, we would suggest the use of triple helix formation with fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides (32), prior to extending the DNA fragments into the surface. In this manner, the transposon insertion mapping could be done at the single molecule level by automated fluorescent microscopy. Developing a single molecule approach to obtaining the positional information would increase the accuracy of the mapping, which implies a reduction in the number of clones needed to obtain a high quality sequence.

Consistent with the major morphological changes undergone by Drosophila Y chromosomes, Berloco et al. (15) found that the Y chromosome in the melanogaster subgroup are either telocentric or metacentric (Supplementary Figure 2). However, they have always found HeT-A-related sequences in the centromeric region, independently of the position of the centromere. It seems that intra-chromosomal rearrangements have recurrently occurred in these species, probably by means of an inversion.

Understanding the presence of telomere-specific retroelements (HeT-A and TART) at the centromeric region of the Y chromosome is a long standing issue. Two hypotheses have been considered so far: one favors the idea that small fragments of telomeres could have been moved into the Y chromosome (10,30) while the other considers the possibility of an entire or almost entire telomere being present (13,14). The two scenarios resemble one another, with the only apparent difference in the size of the fragment being moved. However, the mechanisms that would give rise to each are different. It is well known that Y chromosomes frequently acquire segmental duplications during evolution (33). Consequently, one could consider that the telomeric sequences in non-telomeric regions of the Y chromosome derive from small telomeric fragments, moved into the Y via transposition. On the other hand, if we found evidences of the presence of an entire telomere at the centromere of the Y chromosome, then the most likely origin would be an intra-chromosomal rearrangement. To definitively resolve this issue the sequence of a large portion of this region has been determined in this work, and its analysis suggests that the centromeric region h18 evolved from a telomere, possibly after a pericentric inversion of an ancestral telocentric chromosome. Finally, the genomic structure of this centromeric region could also be considered to support the hypothesis that centromeres were derived from telomeres during the evolution of the eukaryotic chromosome (34,35).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación [BFU2008-02947-C02-01/BMC to A.V.]; an institutional grant from the Fundación Ramón Areces to the Centro de Biología Molecular ‘Severo Ochoa’; the Molecular Genetics Fund established by W. Szybalski at the UW Foundation; and The Wellcome Trust. Funding for open access charge: Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (BFU2008-02947-C02-01).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Drs William S. Reznikoff and I. Y. Goryshin for the kind gift of the hyperactive Tn5 transposase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoskins RA, Carlson JW, Kennedy C, Acevedo D, Evans-Holm M, Frise E, Wan KH, Park S, Mendez-Lago M, Rossi F, et al. Sequence finishing and mapping of Drosophila melanogaster heterochromatin. Science. 2007;316:1625–1628. doi: 10.1126/science.1139816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole CG, McCann OT, Collins JE, Oliver K, Willey D, Gribble SM, Yang F, McLaren K, Rogers J, Ning Z, et al. Finishing the finished human chromosome 22 sequence. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R78. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-5-r78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devine SE, Chissoe SL, Eby Y, Wilson RK, Boeke JD. A transposon-based strategy for sequencing repetitive DNA in eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 1997;7:551–563. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason JM, Biessmann H. The unusual telomeres of Drosophila. Trends Genet. 1995;11:58–62. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)88998-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardue M-L, Danilevskaya ON, Lowenhaupt K, Slot F, Traverse KL. Drosophila telomeres: new views on chromosome evolution. Trends Genet. 1996;12:48–52. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)81399-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levis RW, Ganesan R, Houtchens K, Tolar LA, Sheen F-M. Transposons in place of telomeric repeats at a Drosophila telomere. Cell. 1993;75:1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90318-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abad JP, De Pablos B, Osoegawa K, De Jong PJ, Martin-Gallardo A, Villasante A. TAHRE, a novel telomeric retrotransposon from Drosophila melanogaster, reveals the origin of Drosophila telomeres. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:1620–1624. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villasante A, Abad JP, Planelló R, Méndez-Lago M, Celniker SE, de Pablos B. Drosophila telomeric retrotransposons derived from an ancestral element that was recruited to replace telomerase. Genome Res. 2007;17:1909–1918. doi: 10.1101/gr.6365107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Traverse KL, Pardue M-L. Studies of HeT DNA sequences in the pericentric regions of Drosophila chromosomes. Chromosoma. 1989;97:261–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00371965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Danilevskaya O, Lofsky A, Kurenova EV, Pardue M-L. The Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster contains a distinctive subclass of Het-A-related repeats. Genetics. 1993;134:531–543. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.2.531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Losada A, Abad JP, Villasante A. Organization of DNA sequences near the centromere of the Drosophila melanogaster Y chromosome. Chromosoma. 1997;106:503–512. doi: 10.1007/s004120050272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Losada A, Agudo M, Abad JP, Villasante A. HeT-A telomere-specific retrotransposons in the centric heterochromatin of Drosophila melanogaster chromosome 3. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1999;262:618–622. doi: 10.1007/s004380051124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agudo M, Losada A, Abad JP, Pimpinelli S, Ripoll P, Villasante A. Centromeres from telomeres? The centromeric region of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster contains a tandem array of telomeric HeT-A- and TART-related sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3318–3324. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.16.3318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abad JP, de Pablos B, Agudo M, Molina I, Giovinnazo G, Martín-Gallardo A, Villasante A. Genomic and cytological analysis of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: telomere-derived sequences at internal regions. Chromosoma. 2004;113:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berloco M, Fanti L, Sheenm F-M, Levis RW, Pimpinelli S. Heterochromatin distribution of HeT-A and TART like sequences in several Drosophila species. Cytogenetic Genome Res. 2005;110:124–133. doi: 10.1159/000084944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agudo M, Abad JP, Molina I, Losada A, Ripoll P, Villasante A. A dicentric chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster showing alternate centromere inactivation. Chromosoma. 2000;109:190–196. doi: 10.1007/s004120050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goryshin IY, Reznikoff WS. Tn5 in vitro transposition. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7367–7374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monteilhet G, Perrin A, Thierry A, Colleaux L, Dujon B. Purification and characterization of the in vitro activity of I-SceI, a novel and highly specific endonuclease encoded by a group I intron. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:1407–1413. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.6.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gimble FS, Thorner J. Purification and characterization of VDE, a site-specific endonuclease from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:21844–21853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staden R. The Staden sequence analysis package. Mol. Biotechnol. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sonnhammer EL, Durbin R. A dot-matrix program with dynamic threshold control suited for genomic DNA and protein sequence analysis. Gene. 1995;167 doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00714-8. GC1–GC10 (1996) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang Y, Durfee T, Glasner JD, Qiu Y, Frisch D, Winterberg KM, Blattner FR. Systematic mutagenesis of the Escherichia coli genome. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:4921–4930. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.15.4921-4930.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wild J, Hradecna Z, Szybalski W. Conditionally amplifiable BACs: switching from single-copy to high-copy vectors and genomic clones. Genome Res. 2002;12:1434–1444. doi: 10.1101/gr.130502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jasin M. Genetic manipulation of genomes with rare-cutting endonucleases. Trends Genet. 1996;12:224–228. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gimble FS, Wang J. Substrate recognition and induced DNA distortion by the PI-SceI endonuclease, an enzyme generated by protein splicing. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;263:163–180. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argast GM, Stephens KM, Emond MJ, Monnat RJ., Jr. I-PpoI and I-CreI homing site sequence degeneracy determined by random mutagenesis and sequential in vitro enrichment. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;280:345–353. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou M, Bhasin A, Reznikoff WS. Molecular genetic analysis of transposase-end DNA sequence recognition: cooperativity of three adjacent base-pairs in specific interaction with a mutant Tn5 transposase. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:913–925. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danilevskaya ON, Arkhipova IR, Traverse KL, Pardue M-L. Promoting in tandem: the promoter for telomere transposon HeT-A and implications for the evolution of retroviral LTRs. Cell. 1997;88:647–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81907-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abad JP, De Pablos B, Osoegawa K, De Jong PJ, Martin-Gallardo A, Villasante A. Genomic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster telomeres: full-length copies of HeT-A and TART elements at telomeres. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:1613–1619. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George JA, DeBaryshe PG, Traverse KL, Celniker SE, Pardue M-L. Genomic organization of the Drosophila telomere retrotransposable elements. Genome Res. 2006;16:1231–1240. doi: 10.1101/gr.5348806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacalone J, Delobette S, Gibaja V, Ni L, Skiadas Y, Qi R, Edington J, Lai Z, Gebauer D, Zhao H, et al. Optical mapping of BAC clones from the human Y chromosome DAZ locus. Genome Res. 2000;10:1421–1429. doi: 10.1101/gr.112100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Géron-Landre B, Roulon T, Desbiolles P, Escudé C. Sequence-specific fluorescent labeling of double-stranded DNA observed at the single molecule level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gvozdev VA, Kogan GL, Usakin LA. The Y chromosome as a target for acquired and amplified genetic material in evolution. Bioessays. 2005;27:1256–1262. doi: 10.1002/bies.20321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villasante A, Abad JP, Méndez-Lago M. Centromeres were derived from telomeres during the evolution of the eukaryotic chromosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10542–10547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703808104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villasante A, Méndez-Lago M, Abad JP, Montejo de Garcíni E. The birth of the centromere. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2872–2876. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.23.5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szybalski W, Wild J, Villasante A, Méndez-Lago M. Transposon-based innovative method for sequencing highly repetitive DNA in BAC/oriV clones. 2005 USPTO Serial No. 11/077530 (WARF[2005] P04312US). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.