Abstract

We evaluated the inhibition of striatal cholinesterase activity following intracerebral administration of paraoxon assaying activity either in tissue homogenates ex vivo or by substrate hydrolysis in situ. Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) or paraoxon in aCSF was infused unilaterally (0.5 μl/min for 2 hr) and ipsilateral and contralateral striatum were harvested for ChE assay ex vivo. High paraoxon concentrations were needed to inhibit ipsilateral striatal cholinesterase activity (no inhibition at <0.1 mM; 27% at 0.1 mM; 79% at 1 mM paraoxon). With 3 mM paraoxon infusion, substantial ChE inhibition was also noted in contralateral striatum. ChE histochemistry generally confirmed these concentration- and side-dependent effects. Microdialysates collected for up to 4 hr after paraoxon infusion inhibited ChE activity when added to striatal homogenate, suggesting prolonged efflux of paraoxon. Since paraoxon efflux could complicate acetylcholine analysis, we evaluated the effects of paraoxon (0, 0.03, 0.1, 1, 10 or 100 μM, 1.5 μl/min for 45 min) administered by reverse dialysis through a microdialysis probe. ChE activity was then monitored in situ by perfusing the colorimetric substrate acetylthiocholine through the same probe and measuring product (thiocholine) in dialysates. Concentration-dependent inhibition was noted but reached a plateau of about 70% at 1 μM and higher concentrations. Striatal acetylcholine was below the detection limit at all times with 0.1 μM paraoxon but was transiently elevated (0.5–1.5 hr) with 10 μM paraoxon. In vivo paraoxon (0.4 mg/kg, sc) in adult rats elicitedabout 90% striatal ChE inhibition measured ex vivo, but only about 10% inhibition measured in situ. Histochemical analyses revealed intense AChE and glial fibrillary acidic protein staining near the cannula track, suggesting proliferation of inflammatory cells/glia. The findings suggest that ex vivo and in situ cholinesterase assays can provide very different views into enzyme-inhibitor interactions. Furthermore, the proliferation/migration of cells containing high amounts of cholinesterase just adjacent to a dialysis probe could affect the recovery and thus detection of extracellular acetylcholine in microdialysis studies.

Introduction

Organophosphorus (OP) insecticides are used worldwide in agricultural, urban and household applications to control insect pests (Kiely et al., 2004). OP insecticides elicit acute toxicity by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE, EC 3.1.1.7) and are thus classed as anticholinesterases. Some anticholinesterases are used to treat neurodegenerative and neuromuscular diseases (Pope et al., 2005; Woltjer et al., 2006), while others have been exploited in chemical warfare and terrorism (Pope et al., 2005; Kellar, 2006; Watson et al., 2006). Around the globe, human intoxications by OP insecticides are estimated to be between 1–3 million per year, resulting in several hundred thousands of fatalities annually (Gunnell et al., 2003; Eddleston et al., 2002).

Parathion (PS) is a prototype OP insecticide, which though banned or limited in many developed countries, is still used widely elsewhere. Parathion has likely been responsible for more human fatalities than any other insecticide (Murphy 1980; WHO, 1992). Parathion undergoes oxidative desulfuration by cytochrome P450 isozymes to the reactive metabolite paraoxon (Sultatos, 1994), a highly potent ChE inhibitor (Gallo and Lawryk, 1991; Kousba et al., 2004). Inhibition of AChE by paraoxon and other anticholinesterases in vivo causes accumulation of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) in neuronal synapses and neuromuscular junctions, thereby leading to prolonged over-stimulation of cholinergic receptors and resulting cholinergic toxicity (Lotti, 2000). Signs of cholinergic toxicity following extensive acetylcholinesterase inhibition can include autonomic dysfunction, muscle fasciculations, seizures, respiratory failure and others (for review, see Pope et al., 2005).

OP insecticides may have additional macromolecular targets that modulate the expression of cholinergic toxicity associated with AChE inhibition. Paraoxon has been shown to act directly on muscarinic autoreceptors in striatal slices to decrease acetylcholine release in vitro (Liu et al., 2002). More recent studies indicate that some OP anticholinesterases can inhibit enzymes that degrade endocannabinoids, global neuronal signals that regulate the release of other neurotransmitters (Quistad et al., 2002, 2006; Nallapaneni et al., 2006, 2008). Selective non-cholinesterase sites of action could differentially influence the degree of acetylcholine accumulation elicited by anticholinesterases. There is a need to develop and characterize experimental approaches that might lead to a better understanding of such neuromodulatory mechanisms at the cholinergic synapse. We report here studies on the comparative effects of intracerebral (by either direct infusion or reverse dialysis) and systemic administration of paraoxon on striatal cholinesterase activity and acetylcholine accumulation. Evaluation of the relationship between acetylcholinesterase inhibition and acetylcholine accumulation among different OP toxicants may be useful in determining OP-selective, non-cholinesterase actions that could contribute to selective toxicity.

Methods

Chemicals

Paraoxon (O, O′-diethyl-p-nitrophenyl-phosphate, 99%) was purchased from Chem Service (West Chester, PA) and kept dessicated under nitrogen at 4°C. Acetylcholine iodide (acetyl-3H, specific activity 76.0 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Wellesley, MA). Guide cannulae (MD 2250) and microdialysis probes (MD 2204, 4 mm membrane) were purchased from Bioanalytical Systems Inc. (BAS, Lafayette, IN). All other chemicals used in this study were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). For infusion or reverse dialysis, paraoxon was dissolved in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; NaCl, 147 mM; KCl, 3 mM; MgCl2, 1 mM; CaCl2, 1.2 mM; 1.5 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) prepared on the day of use. For subcutaneous dosing, paraoxon was dissolved in peanut oil (100%, Lou Ana, Venture Foods, CA) and injected at a volume of 1 ml/kg.

Animals and Surgery

Adult, male Sprague-Dawley rats (2–3 months-old, body weight 275–299 g) were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN) and maintained in a temperature controlled room (23°C) with a 12 hr light:12 hr dark illumination cycle (0700–1900 hr). Animals were allowed free access to food and water. All surgical procedures were performed according to protocols established in the NIH/NRC Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The guide cannula for striatal infusion and dialysis was surgically inserted in rats under anesthesia (ketamine/xylazine 9:1 mixture, 0.6 ml/kg, ip) into the right striatum using the following coordinates: anterior (to bregma), 1.2 mm; lateral, −2.2 mm; and ventral, −3.4 mm (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Two screws were inserted on each side and the cannula was secured with dental cement. Animals were allowed to recover from surgery for 5–7 days prior to study. In the control experiment to evaluate possible changes in cholinesterase activity in response to the cannulation procedure, the cannula was placed above the right claustrum (an area relatively near striatum but with exceptionally low baseline AChE activity) using the coordinates: anterior, 2.2 mm; lateral, −2.2 mm; ventral, −3.4 mm (Paxinos and Watson, 1998).

Intra-striatal Infusion of Paraoxon

A microdialysis probe (MD 2204, BAS, West Lafayette, IN) minus the dialysis membrane was used for intra-striatal infusion of paraoxon. Rats (n=4–8/treatment group) were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane and the modified infusion probe was inserted into the previously placed cannula. Rats were placed in a Raturn® chamber (BAS, West Lafayette, IN) and infused with aCSF for 90 min (Karanth et al., 2006, 2007). Either aCSF or paraoxon dissolved in aCSF (0.1, 0.5, 1 or 3 mM) was then infused for 2 hr at 0.5 −l/min (preliminary studies indicated that paraoxon was stable in aCSF under these conditions). Immediately after infusion, rats were euthanized and right (ipsilateral) and left (contralateral) striatum were dissected and stored at −80°C until assay for total ChE activity, or whole brains were dissected and rapidly frozen with dry ice for subsequent histochemistry.

Ex vivo Cholinesterase Assay

Total cholinesterase (ChE) activity in striatal homogenates was measured by the method of Johnson and Russell (1975) using [3H] acetylcholine iodide as substrate (1 mM final concentration). Total protein content in striatal homogenates was measured using the Lowry method (Lowry et al., 1959) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. ChE activity was reported as nmol acetylcholine hydrolyzed/min mg protein.

In situ Cholinesterase Assay

The in situ ChE assay was modified from a standard spectrophotometric method (Ellman et al., 1961; Testylier et al., 1998; Joosen et al., 2007). For these studies, rats were briefly anesthetized with isoflurane and intact microdialysis probes (MD 2204, BAS, West Lafayette, IN) were inserted into the cannula, followed by perfusion of aCSF for 90 min to collect three 30-min baseline fractions. Paraoxon (0, 0.03, 0.1, 1, 10 or 100 μM in aCSF) was then perfused for 45 min, followed by acetylthiocholine (5 mM in aCSF) for the next 4.5 hours. Nine, 30-min fractions were collected. Thiocholine was assayed in fractions 2–9 essentially as described by Ellman and colleagues (Ellman et al., 1961). Briefly, forty μl of each dialysate fraction was mixed with 100 μl of 0.5 mM DTNB (5, 5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid, dissolved in aCSF), and absorbance was measured at 412 nm with a microplate reader (Spectra MAX340PC, Molecular Devices, Corp. Sunnyvale, CA). All values were corrected for nonenzymatic hydrolysis using no-enzyme blanks containing aCSF and DTNB.

Histochemistry

For AChE staining, frozen brains were blocked and sectioned (14 μm) in the coronal plane until a section containing striatal tissue on both left and right sides was obtained. One in every 20 slices was then collected, for a total of 10 slices per brain, spanning the cannulation site. In a control experiment, equivalent sections were similarly collected near a cannulation site in the adjacent claustrum. Histochemistry with acetylthiocholine was conducted on each collected slice by the method of Koelle and Friedenwald (1949). Reaction conditions were chosen to ensure that staining was selective for AChE and proportional in intensity to enzyme activity (Hammond et al., 1996). GFAP immunohistochemistry was carried out on fresh frozen slide-mounted sections fixed 30 min in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by three 3-min rinses with 0.1 M phosphate buffered NaCl, pH 7.4 (PBS). In a one-step staining procedure, mouse monoclonal anti-GFAP conjugated with Cy3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) diluted 1:800 in PBS was applied for 2 hr at room temperature. Digital images of stained sections were captured under a Zeiss fluorescence microscope (10X objective) and converted to inverse gray scale in a uniform manner with Adobe Photoshop.

Microdialysis

A separate group of rats (n=4) was infused with aCSF for 90 min and three 30-min baseline dialysate fractions were collected as above. Paraoxon (0,0.1 or 10 μM in aCSF) was then administered by reverse dialysis at 1.5 μl/min for 45 min, followed immediately by aCSF alone for 4.5 hours at the same flow rate. Nine 30-min fractions were collected and stored at −80°C. ACh levels were subsequently measured in fractions 2–9 (analysis was not conducted in fraction 1 to avoid possible contamination of the enzyme column by paraoxon).

Acetylcholine Analysis

Dialysates (10 μl) were analyzed for ACh levels by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described earlier (Herzog et al., 2003; Karanth et al., 2006) using electrochemical detection with a Coulochem III detector (ESA, Chelmsford, MA). An external standard curve was used to quantify acetylcholine. The detection limit of our system was 25 fmol acetylcholine/10 μl. ACh levels in dialysates were expressed as fmol/fraction.

Statistical Analysis

ACh and ChE data were analyzed by one-way and two-way ANOVA followed by linear contrasts using the JMP statistical package (SAS 1995).

Results

Pilot studies were conducted to evaluate the effects of infusing paraoxon into the striatum at low concentrations (0.1, 0.5 and 10 μM; 0.2 μl for 12 h). There was no significant effect on striatal ChE measured ex vivo with any of these concentrations (data not shown). In subsequent studies we therefore increased paraoxon concentrations, and adjusted the rate and duration of infusion. Figure 1 shows concentration-dependent inhibition of ChE activity after infusions of 0.1, 0.5, 1 or 3 mM (0.5 μl/min for 2 h). Maximal ChE inhibition (79%) occurred with 1 mM paraoxon, and was confined to the ipsilateral side. When paraoxon was increased to 3 mM, ipsilateral ChE inhibition did not increase, but inhibition was also noted on the contralateral side.

Figure 1. Effects of direct infusion of paraoxon in adult rat striatum on cholinesterase activity measured ex vivo.

Rats were infused with 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1 or 3 mM paraoxon (0.5 μl/min for 2 hours) into right (ipsilateral) striatum as described in Methods. After sacrifice, left and right striatum were dissected for radiometric assay of cholinesterase activity. Cholinesterase activity is expressed as percent of contemporaneous control values (infused with aCSF only) in the ipsilateral and contralateral striatum. Data represent mean ± SE, n = 4–6/treatment group. Asterisks indicate significant differences from controls and pound signs indicate significant differences between ipsilateral and contralateral sides (p<0.05). Combined control cholinesterase activities were 273 ± 22 and 282 ± 18 nmol acetylcholine hydrolyzed/min mg protein in the contralateral and ipsilateral side, respectively. An asterisk indicates a significant difference from control (i.e., aCSF infusion).

Acetylcholine can be measured in microdialysates following the infusion of an anticholinesterase to study the relationship between the extent of acetylcholinesterase inhibition and the degree of acetylcholine accumulation. Because of the high concentrations of paraoxon needed to elicit extensive ChE inhibition with direct infusion, however, we were concerned that residual paraoxon might leach from the tissue into microdialysates and confound the subsequent measurement of ACh (which requires an an active immobilized AChE reactor column). Indeed, when dialysates from paraoxon-infused rats were incubated with a fresh striatal homogenate, ChE activity was markedly reduced (dialysates from from rats infused with on aCSF infusions had no effect on ChE activity, Figure 2). Moreover, the anti-cholinesterase “activity” was present in dialysates collected as long as 4 hr after paraoxon infusion ended.

Figure 2. Persistent efflux of paraoxon into dialysates following infusion.

Rats were infused with aCSF or paraoxon (1 mM) as described in Methods. Dialysates were collected and aliquots pre-incubated with striatal homogenate prior to measuring cholinesterase activity. Data represent mean percent of control activity ± SE, n = 4/treatment group. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p<0.05) from controls.

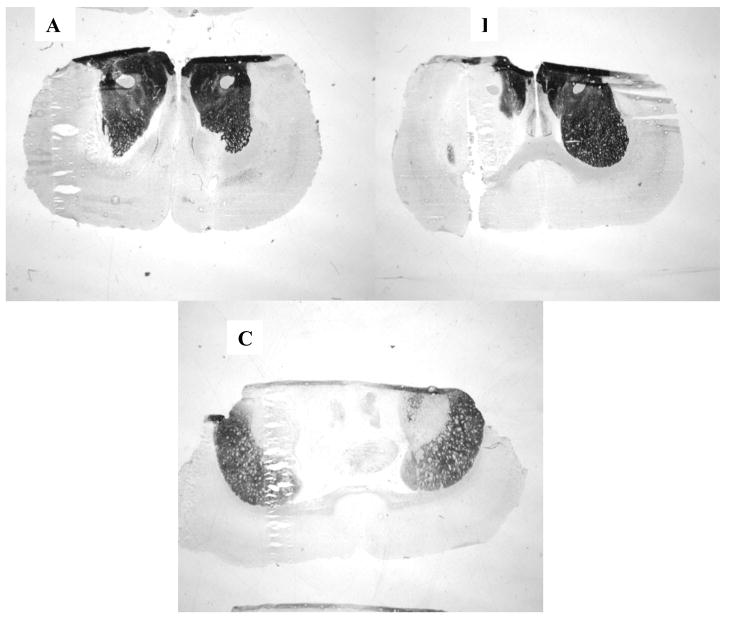

Histochemistry of brain sections revealed the distribution of AChE activity after infusion of vehicle (aCSF), or paraoxon (1 or 3 mM). After aCSF infusions, AChE staining in ipsilateral and contralateral striatum was comparably intense (Figure 3A). After infusions with 1 mM paraoxon, however (Figure 3B), most of the ipsilateral striatum lost all staining, while the contralateral side was largely unaffected. In contrast, after infusion of 3 mM paraoxon, there was marked reduction in staining on both sides. Thus, the biochemical and histochemical assays generally agreed in demonstrating unilateral ChE inhibition from paraoxon infusions at I mM, but bilateral inhibition at 3 mM.

Figure 3. Histochemical analysis of acetylcholinesterase inhibition following paraoxon infusion.

A) AChE staining in rats infused with aCSF, B) AChE staining in rats infused with 1 mM paraoxon, and C) AChE staining in rats infused with 3 mM paraoxon. In all panels, the cannulated (ipsilateral) side is on the left. Within each treatment condition, replicate animals (n=3/treatment group) showed the representative pattern of AChE staining.

The preceding results, including both the high concentrations of paraoxon needed to inhibit striatal ChE ex vivo and the apparent leaching of the inhibitor out of the tissue after terminating perfusion, led us to explore alternative means of delivering the toxicant to the brain and assessing ChE inhibition. We investigated the delivery of paraoxon through a microdialysis probe, followed by enzyme assay in situ by measuring the conversion of substrate (acetylthiocholine) delivered through the same probe. It was felt that this system might lead to a more accurate measure of the relationship between ChE inhibition and extracellular acetylcholine accumulation. The resultant in situ assays revealed a concentration-dependent inhibition of striatal ChE after reverse dialysis with 0.03 to 1 μM paraoxon (36–70%), but with no further increase at 10 μM (Figure 4) or even 100 μM (data not shown). With all concentrations of paraoxon, ChE activity recovered during the 4 hr observation period. ACh remained below the detection limit in all dialysates from rats with reverse dialysis administration of 0.1 μM paraoxon. Following 10 μM paraoxon, however, ACh was transiently detected in dialysates collected during the 30–60, 60–90 and 90–120 minute intervals, after which ACh again dropped below the limit of detection.

Figure 4. Effects of intra-striatal paraoxon administration by reverse dialysis on cholinesterase activity and acetylcholine accumulation.

Rats were perfused with 0, 0.03, 0.1, 1 or 10 μM paraoxon in the right (ipsilateral) striatum and ChE was assayed in situ as described in Methods. ChE activity (left y-axis) is reported as percent of baseline (immediately prior to paraoxon perfusion). ACh levels (right y-axis) are reported as fmoles/fraction (60 μl). Data represent mean ± SE, n = 3–4/treatment group. Note that ACh was only detected in fractions 2–4 from rats infused with paraoxon (10 μM).

For an additional perspective, we administered paraoxon systemically (0.4 mg/kg, sc) and measured striatal ChE activity by both the in situ and ex vivo assays (Figure 5). Striatal ChE was slightly but significantly inhibited from 3–4 hours after treatment when evaluated by the in situ method. At four hr after dosing, these same animals were sacrificed and striatum was dissected for ChE assay ex vivo, which demonstrated 90% inhibition.

Figure 5. Effects of subcutaneous injection of paraoxon on in situ and ex vivo cholinesterase activity.

Rats were injected with paraoxon (0.4 mg/kg, sc), and monitored for in situ cholinesterase activity for 4 hr as described in Methods. The rats were then sacrificed and cholinesterase activity was assayed ex vivo (inset). Values are expressed as mean ± SE, n = 4/treatment group. Asterisks indicate significant differences in cholinesterase activity (p<0.05) from contemporaneous controls.

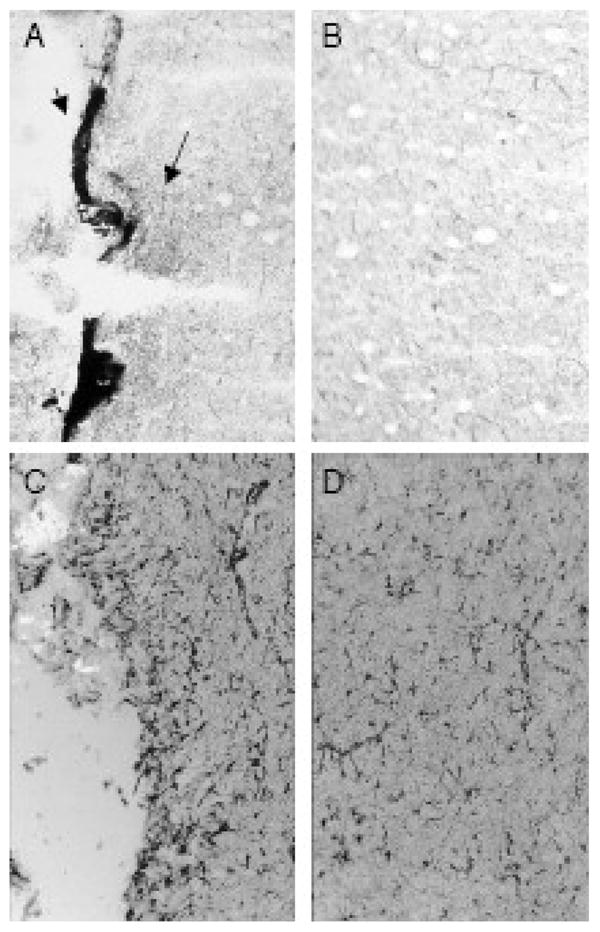

A control experiment was performed to investigate why the in situ assay showed so much less inhibition than noted with the ex vivo assay. For that purpose, two additional rats were cannulated unilaterally in the claustrum, an area immediately rostral to the striatum and containing very low levels of acetylcholinesterase activity. One week later brains were harvested and sectioned for AChE histochemistry. Tissues from both cannulated rats showed “hot spots” of AChE activity around the cannula track and its termination, i.e., the same region that would be interrogated by a microdialysis probe (Figure 6). This activity was much more intense than in the surrounding portion of the claustrum, which as noted above is normally poor in AChE. Such an increase in acetylcholinesterase staining could have been due to reactive gliosis associated with the cannulation procedure. These tissues were therefore evaluated for GFAP staining. As shown in Figure 7, GFAP staining was also increased in the general area around the cannula track.

Figure 6. Implantation of the intracerebral cannula increases AChE staining adjacent to the cannula track.

Rats were surgically implanted with a microdialysis cannula into the right claustrum, an area near the striatum but with very low AChE activity. Seven days later, brains were collected and frozen. Tissues were then serially sectioned (14 μM) around the site of cannulation and stained for AChE activity (see Methods). Panels A and B show AChE staining in two different rats 7 days after cannula implantation. Note the areas of intense staining adjacent to the cannula track, and markedly lower background staining in surrounding tissue. No such intense AChE staining was noted in the contralateral claustrum in cannulated rats, nor in control rats.

Figure 7. AChE and GFAP staining along an intracerebral cannula track.

Rats were surgically implanted with a microdialysis cannula into the claustrum as in Figure 6. Seven days later, brains were collected, frozen and tissues serially sectioned around the site of cannulation for AChE and GFAP staining (see Methods). Panels A (ipsilateral) and B (contralateral) show AChE staining. The arrows in 7A show both an area of intense staining and a larger, surrounding region of more moderate but elevated staining, while 7B shows minimal background staining in the contralateral side. Panels C (ipsilateral) and D (contralateral) show GFAP staining, with increased staining evident adjacent to the cannula track compared to lower background staining in surrounding tissue and the contralateral side.

Discussion

Organophosphorus insecticides elicit toxicity by inhibiting the enzyme AChE (Aldridge, 1950; Aldridge and Reiner, 1972; Fukuto 1990). Inhibition of AChE leads to accumulation of the neurotransmitter ACh in cholinergic synapses, leading to prolonged stimulation of cholinergic receptors and cholinergic toxicity including SLUD signs (acronym for salivation, lacrimation, urination and defecation), fasciculations, tremors, and respiratory dysfunction (Joosen et al., 2007). In some cases, prolonged activation of cholinergic signaling can also induce epileptic seizures with consequent neuropathology (Lallement et al., 1992;Shih and McDonough, 1997).

It is reasonable to assume that the degree of acetylcholine accumulation in the nervous system and thus signs of cholinergic toxicity is directly related to the extent of AChE inhibition. Direct actions of some anticholinesterases on other neuronal signaling processes may modulate the expression of cholinergic toxicity, however. Understanding the relationship between AChE inhibition, acetylcholine accumulation, and functional signs of cholinergic toxicity with different OP anticholinesterases may shed light on selective neuromodulatory mechanisms. In our studies, paraoxon infused directly into rat striatum inhibited striatal ChE activity in a concentration-related and ipsilateral-contralateral selective manner, but at concentrations that were markedly higher in magnitude than needed to inhibit striatal ChE in tissue homogenates in vitro (Mortensen et al., 1998). Jacobsson et al., (1997) reported direct infusion of an exceedingly high concentration (10 mM) of the extremely potent nerve agent soman into rat striatum and its association with extensive AChE inhibition. These authors estimated 10% efficiency of transfer through the dialysis membrane, or effective delivery of around 1 mM soman directly into the striatum. Soman has an IC50 somewhere on the order of 1 nM (Holmstedt, 1963), or essentially six orders of magnitude higher than used in the direct infusion studies by Jacobsson and coworkers (1997). Liu et al., (2002) reported that while chlorpyrifos oxon inhibited striatal cholinesterase activity in homogenates with an IC50 in the low nanomolar range (3.6 nM, 15 min at 37ºC), when added to suprafused striatal slices chlorpyrifos oxon was markedly less potent (IC50 about 1 uM, 15 min perfusion at 37ºC). It therefore appears that markedly higher concentrations of OPs are needed to inhibit cholinesterases when delivered directly to intact compared to disrupted tissues, even though organophosphorus anticholinesterases are generally quite hydrophobic and should readily pass through cellular membranes.

Other studies have noted that slow infusion of various neuroactive compounds (e.g. amphetamine sulfate, sulpiride, the D2 receptor agonist LY17155) required relatively high concentrations (1–10 mM) to diffuse 1 mm from the infusion probe (Westerink and De Vries, 2001). The approximate volume of the ipsilateral striatum is about 25 μl (Yim et al., 1997), but infusion of 60 μl of 100 μM paraoxon caused less than 25% inhibition of ChE activity measured ex vivo (see Figure 1). The exceptionally high concentrations of paraoxon needed to inhibit cholinesterase with intracerebral infusion at low flow rates could be partially due to the continuous flow of extracellular fluid, aiding in removal of inhibitor molecules prior to their interaction with target enzymes. Furthermore, there was apparent efflux of paraoxon from the tissue following termination of infusion (Figure 2), potentially confounding any subsequent analysis of ACh using an immobilized enzyme reactor column. Together, these findings suggested that direct intracerebral infusion of an anticholinesterase to study neurochemical relationships between cholinesterase inhibition, acetylcholine accumulation and potentially other neuromodulatory processes posed substantial methodological problems.

We hypothesized that localized ChE inhibition, i.e., inhibiting enzymes in the immediate area sampled by a microdialysis probe, might provide a more suitable approach for studying such neurochemical relationships. We thus administered paraoxon into the striatum using reverse dialysis with a microdialysis probe, and subsequently assayed ChE activity in situ by perfusion of the substrate acetylthiocholine and measuring its hydrolysis product (thiocholine) in dialysates (Testylier et al., 1998). Using this approach, concentration-dependent inhibition of striatal ChE was again noted (Figure 4), but with much lower concentrations of paraoxon than required to elicit inhibition in the direct infusion/ex vivo assay.

The inhibition and recovery of ChE activity after reverse dialysis of paraoxon (10 μM) generally correlated with ACh accumulation in striatal dialysates from the same animals (Figure 4). Striatal ChE inhibition of about 70% was noted thirty minutes after termination of reverse dialysis of 10 μM paraoxon, and dialysates collected at the same time contained the highest concentration of ACh (968 ± 23 fmol/fraction). A rapid decrease in ACh levels then followed, concurrent with a recovery of ChE activity(Figure 4). These results are in general agreement with the studies by Tonduli and coworkers (1999) where >65% ChE inhibition by the potent nerve agent soman was associated with the highest level of ACh accumulation in rat cortex. Interestingly, these investigators (Tonduli et al., 1999) suggested that the in situ assay of ChE underestimated the degree of inhibition compared to the classical ex vivo assay method, when relatively low levels of inhibition were elicited. Our results are in general agreement. One reason may be that the in situ assay preferentially measures activity of AChE molecules oriented towards the extracellular space, because the quaternary substrate (acetylthiocholine) does not readily cross cellular membranes (Testylier et al., 1998). Substrate charge is of little consequence, however, when tissues are homogenized (in particular in the presence of a detergent) and the substrate has more ready access to enzyme active sites.

The widespread distribution of AChE throughout cholinergic synapses in the central and peripheral nervous system assures that acetylcholine is rapidly degraded under normal conditions. AChE is one of the most efficient enzymes in biology, and this high efficiency contributes to the difficulties in measuring ACh in microdialysates. Researchers have traditionally overcome this problem by including an exogenous ChE inhibitor such as neostigmine in their microdialysis perfusion buffers (see Chang et al., 2006). Previous work from our lab (Karanth et al., 2006) has shown that perfusion of neostigmine (1 μM) by reverse dialysis into adult rat striatum can increase ACh accumulation markedly. Unfortunately, adding neostigmine to the perfusion buffer confounds the interpretation of anticholinesterase-mediated changes in ACh accumulation (Karanth et al., 2006). In the present study, with no added ChE inhibitor in the perfusion buffer, ACh was below the limit of detection in most samples taken after reverse dialysis of a lower concentration of paraoxon (0.1 μM). Using 10 μM paraoxon, however, striatal acetylcholine was briefly but significantly elevated (Figure 4).

When rats were treated systemically with paraoxon (0.4 mg/kg, sc), striatal cholinesterase was minimally inhibited (about 10%) assayed in situ, while tissues from these same rats showed about 90% inhibition when removed and assayed ex vivo (Figure 5 and inset). Aside from differences in how the tissue was sampled (intact vs. homogenized), these two approaches also used different biochemical assays to measure ChE, i.e., photometric vs. radiometric enzyme assays. In general, the radiometric and photometric methods provide relatively similar results (Nostrandt et al., 1993). A previous report (Testylier et al., 1998) showed that cortical cholinesterase inhibition measured in situ correlated quite well with inhibition measured ex vivo following intracerebroventricular administration of the nerve agent VX. In contrast, these same investigators (Testylier et al., 1998) reported that it took a massive systemic dose (10 mg/kg, sc) of VX to elicit 50% cortical cholinesterase inhibition when measured by the in situ assay (the LD50 of VX in rats given by subcutaneous administration is about 20 μg/kg; Shih and McDonough, 1999). Thus, under some conditions, lesser ChE inhibition may be detected using the in situ assay. As noted above, lesser access to cellular ChE molecules with in situ delivery of the quaternary substrate (acetylthiocholine) could contribute to these findings.

We hypothesized that the cannulation process itself may lead to inflammation and proliferation of glial cells adjacent to the cannula, along with possible disruption of local blood flow. Under these conditions, systemically administered anticholinesterase may have difficulty reaching the site being “sampled” by the dialysis probe. Indeed, when we cannulated the claustrum, an area with inherently low AChE activity, and then histochemically evaluated AChE activity 7 days later, intense areas of AChE reactivity were noted in the region immediately surrounding the cannula site (Figure 6). Moreover, areas of less intense but increased AChE activity were noted around these intensely staining regions (Figure 7). Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) staining was also markedly increased in the area surrounding the cannula track (Figure 7). The GFAP stain demonstrates, as would be expected, a significant degree of reactive astrocytosis in the vicinity of the cannula track. These cells may at least partially account for the occasional densely AChE-reactive areas; in any case they localize closely with the “shadow region” that shows modestly increased AChE activity. Thus, the morphologic evidence supports the concept that reactive increases in AChE expression may under some experimental conditions influence local acetylcholine metabolism in cannulated brain. These data suggest that cannula placement results in astrocytosis that likely disturbs the local microvasculature, and is accompanied by local increases in the expression of AChE activity. Both of these effects could contribute to persistent AChE hydrolysis measured locally by the in situ assay (i.e., a relative lack of inhibition) in rats given systemic paraoxon and exhibiting marked ChE inhibition when measured in tissue homogenates.

In conclusion, the results from this study suggest that direct intrastriatal infusion of paraoxon requires remarkably high concentrations to inhibit striatal ChE activity when measured in tissue homogenates ex vivo. In contrast, reverse dialysis of paraoxon into the striatum and assay of acetylcholine hydrolysis in situ suggested lower concentrations could locally inhibit striatal ChE and elevate extracellular ACh levels. These data raise concern that measurement of ChE activity ex vivo in tissue homogenates following in vivo dosing can potentially provide very different information than measurement of ChE activity in situ. The basis for differences in cholinesterase inhibition measured by ex vivo and in situ assays following either intracerebral or systemic anticholinesterase exposure, and the related implications for understanding mechanisms of anticholinesterase toxicity, require further study.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by research grant R01 ES009119 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH (C.N.P.), and by the Oklahoma State University Board of Reagents. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIEHS.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aldridge WN. Some properties of specific cholinesterase with particular reference to the mechanism of inhibition by diethyl p-nitrophenyl thiophosphate and analogs (E605) Biochem J. 1950;46:451–460. doi: 10.1042/bj0460451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldridge WN, Reiner E. Interaction of esterases with esters of organophosphorus and carbamic acids. North Holland, Amsterdam: 1972. Enzyme inhibitors as substrates. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Q, Savage LM, Gold PE.2006Microdialysis measures of functional increases in ACh release in the hippocampus with and without inclusion of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in the perfusate J Neurochem 97697–706 .Scopus [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, Karalliedde L, Buckley N, Fernando R, Hutchinson G, Isbister G, Konradsen F, Murray D, Piola JC, Senanayake N, Sheriff R, Singh S, Siwach SB, Smit L. Pesticide poisoning in the developing world-a minimum pesticide list. Lancet. 2002;360:1163–1167 . doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr , Featherstone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95 . doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukoto TR. Mechanism of action of organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;87:245–254 . doi: 10.1289/ehp.9087245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo MA, Lawryk NJ. Organic phosphorus pesticides. In: Hayes JWJ, Laws ER Jr, editors. Handbook of Pesticide Toxicology: Classes of Pesticides. Academic Press; New York: 1991. pp. 917–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: a continuing tragedy in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:902–909 . doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond PI, Jelacic T, Padilla S, Brimijoin S. Quantitative, video-based histochemistry to measure regional effects of anticholinesterase pesticides in rat brain. Anal Biochem. 1996;241:82–92 . doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog CD, Nowak KA, Sarter M, Bruno JP. Microdialysis without acetylcholinesterase inhibition reveals an age related attenuation in stimulated cortical acetylcholine release. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:861–863 . doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstedt B. Structure-activity relationships of the organo-phosphorus anticholinesterase agents. Handbuch der Experimentellen Pharmakologie Erganzungwerk. 1963;15:428–485. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson SO, Cassel GE, Karlsson BM, Sellström A, Persson SA. Release of dopamine, GABA and EAA in rats during intrastriatal perfusion with kainic acid, NMDA and soman: a comparative microdialysis study. Arch Toxicol. 1997;71:756–765 . doi: 10.1007/s002040050458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CD, Russell RL. A rapid, simple radiometric assay for cholinesterase, suitable for multiple determinations. Anal Biochem. 1975;64:229–238 . doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90423-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joosen MJA, van Helden HPM. Correlations between acetylcholinesterase inhibition, acetylcholine levels and EEG changes during perfusion with neostigmine and N6 –cylcopentyladenosine in rat brain. European J Pharmacol. 2007;555:122–128 . doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanth S, Liu J, Mirajkar N, Pope C. Effects of acute chlorpyrifos exposure on in vivo acetylcholine accumulation in rat striatum. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216:150–156 . doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karanth S, Liu J, Ray A, Pope C. Comparative in vivo effects of parathion on striatal acetylcholine accumulation in adult and aged rats. Toxicology. 2007;239:167–179 . doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellar KJ. Overcoming inhibitions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13263–13264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606052103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely T, Donaldson D, Grube A. Office of prevention, Pesticides, and Toxic substances. USEPA; Washington, DC.20: 2004. Pesticides Industry sales and Usage: 2000 and 2001 market estimates. [Google Scholar]

- Koelle GB, Friedenwald JS. A histochemical method for localizing ChE activity. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1949;70:617–622. doi: 10.3181/00379727-70-17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kousba AA, Sultatos LG, Poet TS, Timchalk C. Comparison of chlorpyrifos-oxon and paraoxon acetylcholinesterase inhibition dynamics: potential role of a peripheral binding site. Toxicol Sci. 2004:166–176. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lallement G, Carpentier P, Collet A, Baubichon D, Pernot-Marino I, Blanchet G. Extracellular acetylcholine changes in rat limbic structures during soman-induced seizures. Neurotoxicology. 1992;138:557–568 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Chakraborti T, Pope C. In vitro effects of organophosphorus anticholinesterases on muscarinic-receptor-mediated inhibition of acetylcholine release in rat striatum. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;178:102–108 . doi: 10.1006/taap.2001.9326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotti M. Organophosphorus compounds. In: Spencer PS, Schaumburg HH, editors. Experimental and Clinical Neurotoxicology. 2. Oxford University Press; New York: 2000. pp. 898–925. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr Al, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen SR, Brimijoin S, Hooper MJ, Padilla S. Comparison of the in vitro sensitivity of rat acetylcholinesterase to chlorpyrifos-oxon: what do tissue IC50 values represent? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;148:46–99 . doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SD. Pesticides. In: Casarett LJ, Doull J, Klassen CD, Amdur MO, editors. Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology: The basic science of poisons. Macmillan; New York: 1980. pp. 357–408. [Google Scholar]

- Nallapaneni A, Liu J, Karanth S, Pope C. Modulation of paraoxon toxicity by the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55, 212-2. Toxicology. 2006;227:173–183 . doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallapaneni A, Liu J, Karanth S, Pope C. Pharmacological enhancement of endocannabinoid signaling reduces the cholinergic toxicity of diisopropylfluorophosphate. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:1037–1043 . doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nostrandt AC, Duncan JA, Padilla S. A modified spectrophotometric method appropriate for measuring cholinesterase activity in tissue from carbaryl-treated animals. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1993;21 :196–203 . doi: 10.1006/faat.1993.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 4. Academic Press; San Diego, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Karanth S, Liu J. Pharmacology and toxicology of cholinesterase inhibitors: uses and misuses of a common mechanism of action. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;19:433–446 . doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2004.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistad GB, Nomura DK, Sparks SE, Segall Y, Casida JE. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor as a target for chlorpyrifos oxon and other organophosphorus pesticides. Toxicol Lett. 2002;135:89–93 . doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quistad GB, Klintenberg R, Caboni P, Liang SN, Casida JE. Monoacylglycerol lipase inhibition by organophosphorus compounds leads to elevation of brain 2-arachidonoylglycerol and the associated hypomotility in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;211:78–83 . doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS. Statistics and Graphics Guide, Version 3. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 1995. SAS. [Google Scholar]

- Shih TM, McDonough JH. Neurochemical mechanisms in soman-induced seizures. J Appl Toxicol. 1997;17:255–264 . doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199707)17:4<255::aid-jat441>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih TM, McDonough JH., Jr Organophosphorus nerve agents-induced seizures and efficacy of atropine sulfate as anticonvulsant treatment. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;64:147–153 . doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultatos LG. Mammalian toxicity of organophosphorus pesticides. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1994;43:271–289. doi: 10.1080/15287399409531921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testylier G, Micoud N, Martinez S, Lallement G. Simultaneous in vivo determination of acetylcholinesterase activity and acetylcholine release in the cortex of waking rat by microdialysis. Effects of VX J Neurosci Methods. 1998;81:53–61 . doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonduli LS, Testylier G, Pernot Marino I, Lallemant G. Triggering of soman-induced seizures in rats: Multiparametric analysis with special correlation between enzymatic, neurochemical and electrophysiological data. J Neurosci Res. 1999;58:464–473 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson A, Bakshi K, Opreski D, Young R, Hauschild V, King J. Cholinesterase inhibitors as chemical warfare agents: Community Preparedness Guidelines. Academic Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Westerink BHC, De Vries JB. A method to evaluate the diffusion rate of drugs from a microdialysis probe through brain tissue. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;109:53–58 . doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. IPCS International Programme on Chemical Safety No 74. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1992. Parathion Health and Safety Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Woltjer RAMD. Therapeutic use of cholinesterase inhibitors in neurodegenerative diseases. In: Gupta RC, editor. Toxicology of Organophosphate and Carbamate Compounds. Academic Press; New York: 2006. pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Yim HJ, Schallert T, Randall PK, Bungay PM, Gonzales RA. Effect of ethanol on extracellular dopamine in rat striatum by direct perfusion with microdialysis. J Neurochem. 1997;68:1527–33 . doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68041527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]