Abstract

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging treatment modality that employs the photochemical interaction of three components: light, photosensitizer, and oxygen. Tremendous progress has been made in the last 2 decades in new technical development of all components as well as understanding of the biophysical mechanism of PDT. The authors will review the current state of art in PDT research, with an emphasis in PDT physics. They foresee a merge of current separate areas of research in light production and delivery, PDT dosimetry, multimodality imaging, new photosensitizer development, and PDT biology into interdisciplinary combination of two to three areas. Ultimately, they strongly believe that all these categories of research will be linked to develop an integrated model for real-time dosimetry and treatment planning based on biological response.

Keywords: PDT, spectroscopy, implicit dosimetry, explicit dosimetry, dynamic process

INTRODUCTION

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an emerging cancer treatment modality based on the interaction of light, a photosensitizing drug, and oxygen.1 PDT has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of microinvasive lung cancer, obstructing lung cancer, and obstructing esophageal cancer, as well as for premalignant actinic keratosis and age-related macular degeneration. Studies have shown some efficacy in the treatment of a variety of malignant and premalignant conditions including head and neck cancer,2, 3 lung cancer,4, 5, 6 mesothelioma,7 Barrett’s esophagus,8, 9 prostate,10, 11, 12 and brain tumors.9, 13, 14, 15 Unlike radiation therapy, PDT uses nonionizing radiation and can be administered repeatedly without cumulative long-term complications since it does not appear to target DNA.

There has been tremendous progress made in the last 2 decades in new technologies and in understanding of the basic biophysical mechanisms of PDT. The most important question to be answered is: “What determines PDT efficacy for a particular patient, photosensitizer, and treatment protocol?” Answering this question will require a unified understanding of the interactions of the three basic components: light, photosensitizer, and tissue oxygenation. We have categorized the current basic research in PDT into five areas: (1) light sources, light transport, and light delivery in tissue; (2) PDT dosimetry; (3) optical and anatomic imaging; (4) new photosensitizers; and (5) PDT biology. Among these, the development of new photosensitizers and PDT biology is traditionally considered outside of the realm of PDT physics and will only be briefly described for completeness. All five areas are linked by a quantitative understanding of the dynamic processes involved in the photochemical interaction that drives PDT. In the next section, we will describe these areas separately.

THE PROBLEMS IN CLINICAL PDT

Modeling the dynamic process of PDT

Photodynamic therapy is inherently a dynamic process. There are three principal components: photosensitizer, light, and oxygen, all of which interact on time scales relevant to a single treatment. The distribution of light is determined by the light source characteristics and the tissue optical properties. The tissue optical properties, in turn, are influenced by the concentration of photosensitizer and the concentration and oxygenation of the blood. The distribution of oxygen is altered by the photodynamic process, which consumes oxygen. Finally, the distribution of photosensitizer may change as a result of photobleaching, the photodynamic destruction of the photosensitizer itself. To account for these interactions, a dynamic model of the photodynamic process is required.

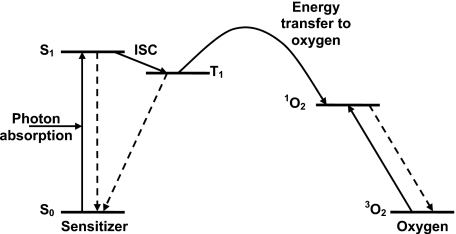

At the most fundamental level, the photodynamic process depends on the photosensitizer molecule itself. Figure 1 shows the energy level, or Jablonski, diagram for a typical type-II photosensitizer. The photochemical reaction is initiated by the absorption of a photon of light by a photosensitizer molecule in its ground state (S0), promoting it to an excited state (S1). Both this state and the ground state are spectroscopic singlet states. One essential property of a good photosensitizer is a high intersystem crossing (ISC) yield, i.e., a high probability of transition from S1 to an excited triplet state (T1). In the T1 state, the photosensitizer can transfer energy to molecular oxygen (3O2), exciting it to its highly reactive singlet state (1O2). The details of this energy transfer process are beyond the scope of this article but have been an area of active study.16

Figure 1.

Energy level diagram for a typical type II photosensitizer and oxygen. The sensitizer in its ground state (S0) absorbs a photon of light and is excited to its first singlet state (S1). It spontaneously decays to its excited triplet state (T1) via ISC. From T1, energy is transferred to ground state molecular oxygen (3O2), creating reactive singlet oxygen (1O2).

Two approaches have been used to study PDT dynamics. First, a microscopic model takes into account diffusion of oxygen and photosensitizer from blood vessels and can determine the singlet oxygen concentration in cells microscopically. Foster et al. were the first to propose such a quantitative model and to verify its results in multicell tumor spheroid models.17, 18 These models demonstrate that the dominant effect of the fluence rate in photodynamic therapy arises because the photochemical process itself consumes oxygen. If the rate of photochemical oxygen consumption is greater than the rate at which oxygen can be resupplied by the vasculature or ambient medium, an induction of transient hypoxia by PDT can result. This effect has been modeled theoretically and has been demonstrated in cell spheroids,17 animals,19 and human tissues,20 and continues to be an area of active research.21 A second, macroscopic model has also been developed.22, 23 This is an empirical model that does not take into account the actual oxygen and photosensitizer diffusion processes microscopically but instead approximates them with simpler functions. It does, however, explicitly account for the larger-scale spatial variation in fluence rate based on the diffusion approximation. This model provides a quantity (reacted singlet oxygen) that can be used directly for clinical PDT dosimetry, and that relates directly to the three-dimensional distribution of photosensitizers, light fluence rate, and a mean tissue oxygenation distribution.22, 23

Current areas of basic PDT research

Light source, transport, and delivery

PDT became popular after the invention of the laser, which allowed the production of monochromatic light that could be easily coupled into optical fibers. The wavelength of light used for PDT is typically in the wavelength range between 600–800 nm, the so called “therapeutic window.”24 In this wavelength range, the energy of each photon (hν) is high enough (>1.5 eV) to excite the photosensitizer and yet is low enough so that the light has sufficient penetration into the tissue. Early lasers were based on either argon gas lasers (488 and 514.5 nm) or frequency doubled Nd:yttrium-aluminun-garnet solid state lasers (532 nm), which were then used to pump a dye laser to produce light in the desired wavelength range. With the development of the diode laser, the laser source has become portable and a turn-key operation. Development of more powerful and cheaper laser sources, e.g., fiber lasers, which couple more efficiently into optical fiber, is an active area of research.

The invention of optical fiber allowed light to be directed easily to deliver irradiation to desired regions without the requirement of a straight light path and is another enabler of PDT. Currently, most PDT procedures are performed with optical fibers. By attaching diffuse scattering tips of various geometrical shapes at the exit end of the fiber, point, linear, and planar light sources can be produced.25 Further development in light delivery devices that produce a light field with various geometrical shapes and in power distribution modulation that covers a larger area and has higher power is still an active area of research.

Light distributions can be modeled using the diffusion approximation to radiative transport.26 The finite-element method is commonly used to solve the diffusion equation27 in an optically heterogeneous medium with arbitrary geometry. Various boundary conditions are used to describe various tissue-tissue, tissue-air, and tissue-water interfaces.26, 28 However, the solution is often inaccurate in regions without a sufficient number of multiple scattering (near the light source or nonscattering medium). In these regions Monte Carlo simulation provides more accurate results but is much slower.29 Active research is on going to solve the Boltzmann equation of light transport directly to provide accurate result while improve the speed of calculation.26, 30

PDT dosimetry

Three general strategies have been developed for dosimetry based on the cumulative dose of singlet oxygen, which is presumed to be predictive of tissue damage. Explicit dosimetry refers to the prediction of singlet oxygen dose on the basis of measurable quantities that contribute to the photodynamic effect.31 The quantities of interest are typically the distributions of light, photosensitizer, and oxygen. The distributions of photosensitizer and oxygenation can be measured via optical spectroscopy, as described above. In current clinical practice, however, the quantity most straightforward to measure is the light dose. Flat photodiode detectors have been used to measure the incident irradiance at the tissue surface in intraoperative PDT.32 These measurements, however, may not accurately reflect the fluence rate in the tissue itself because they neglect contribution of backscattered light. Detectors based on optical fibers overcome this problem by collecting light isotropically.33 The effect on the measured fluence rate is significant.34 Because these probes collect light via multiple scattering, the interface between the scattering tip and the surrounding medium can change the sensitivity of the detector by as much as a factor of 2, requiring careful calibration.35

Because complete explicit dosimetry requires measurement of three different parameters, it is inherently challenging. Two alternatives have been suggested that require measurement of only a single parameter. Direct dosimetry relies on the detection of singlet oxygen itself, either through its own phosphorescence emission or via singlet-oxygen-sensitive chromophores. Implicit dosimetry31 uses a quantity such as fluorescence photobleaching of the photosensitizer, which is indirectly predictive of the production of singlet oxygen. Strategies for direct and implicit dosimetry are under development and will be discussed in later sections.

Anatomic and optical imaging

The most commonly used medical imaging modalities include ultrasound, computer tomography (CT), magnetic resonance, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, single photon emission computer tomography, and positron emission tomography (PET). The first three modalities produce excellent anatomical images, while the latter three provide functional information (e.g., oxygen perfusion or tissue metabolism) at the expense of image resolution. Diffuse optical tomography (DOT) is a viable new biomedical imaging modality.36 This technique images the absorption and scattering properties of biological tissues and has been explored as a diagnosis tool in breast,37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42 brain,43, 44 and bones and joints.45 Some preliminary attempts have been made to perform DOT for prostate.46, 47, 48, 49 DOT at the treatment wavelength can be used as input to calculate light fluence rate distribution for PDT. In addition, it provides access to a variety of physiological parameters that cannot otherwise be measured easily. Another modality, optical coherence tomography (OCT) uses coherent light to obtain high resolution images. However, OCT is rarely used in PDT because of the limitation of penetration depth (∼1 mm).50

Most image reconstruction of DOT is based on solving the inverse problem for the diffusion equation.27 This is an ill-posed problem because of the strong scattering in the turbid medium. As a result, the image resolution of DOT is limited when compared with other imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT. The use of spectroscopic information and∕or a priori anatomic information is common to provide additional constraint to produce reliable DOT reconstruction. Interested readers can find more information from some excellent review articles.51, 52

The concept of absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy as a modality for the diagnosis of disease dates back several decades.53 In recent years, the potential for spectroscopy to diagnose cancer54 and to monitor the progress of cancer treatment55 has been increasingly appreciated. In addition to its role in diagnosis, spectroscopy is particularly applicable to PDT in determining the local drug and oxygen concentrations.56

Photodynamic therapy can cause changes in the concentration and oxygenation of blood in tissue both directly, through photochemical oxygen consumption, and indirectly, through effects on the vasculature and general physiological responses. The monitoring of these responses may, therefore, be predictive of treatment outcome. For oxygen monitoring, the difference in absorption spectra between oxy- and deoxyhemoglobin is used to determine the hemoglobin oxygen saturation, i.e., the fraction of total hemoglobin that is in its oxygenated state. This quantity can be related to the oxygen concentration in the blood using the Hill curve.57 This measurement does not directly measure the concentration of oxygen in the tissue itself, however, it is possible to model the relationship between the vascular and tissue oxygenation. This concept has been investigated in animal models in which the blood flow and∕or oxygenation were monitored and changes correlated with outcome.58, 59

New photosensitizers

Various photosensitizing drugs have been developed. The first-generation photosensitizer, hematoporphyrin derivative, is a mixture of porphyrin monomers and oligomers that is partially purified to produce the commercially available product, porfimer sodium, marketed under the tradename Photofrin®. Photofrin® was approved for treatment of early stage lung cancer in 1998 and for Barrett’s esophagus in 2003. The clinical applicability of Photofrin® has been limited by two factors. First, its absorption peak occurs at too short a wavelength (630 nm) to allow deep penetration in tissue. Second, administration of Photofrin® results in cutaneous photosensitivity lasting up to 6 weeks. These limitations have inspired the development of a second generation of photosensitizers with longer-wavelength absorption peaks and more rapid clearance from skin. Among these was benzoporphyrin derivative monoacid A (BPD-MA), or verteporfin. In preclinical trials, it was observed that verteporfin preferentially targeted neovasculature. This selectivity has been exploited for the treatment of choroidal neovascularization (CNV), an abnormal growth of vessels in the retina associated with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of blindness in the developed world. Verteporfin was approved in the U.S. under the tradename Visudyne for CNV treatment in 2000. Tetra (m-hydroxyphenyl) chlorin (mTHPC, Foscan®) is another second generation photosensitizer, a pure synthetic chlorin compound, which is activated by 652 nm light.60 The major advantages of mTHPC are a short duration of skin photosensitivity (15 days), a high quantum yield for singlet oxygen, and depth of tumor necrosis of up to 10 mm in preclinical models.61 mTHPC has been used for treatment of pleural mesothelioma,7 head-and-neck cancers,62, 63 esophagus,64, 65 prostate,10, 66 pancreas,67 arthritic joints,68 and skin cancers69 and was approved in Europe for PDT of head-and-neck and varieties of other tumors in 2001.

Another development of note is the prodrug δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Unlike other PDT drugs, ALA itself is not a photosensitizer. When taken up by cells, however, it is converted by a naturally occurring biosynthetic process into the photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). ALA can be applied topically, and was approved by the FDA in 1999 for the treatment of actinic keratosis (AK). Table 1 summaries several of the more widely used photosensitizers currently available.

Table 1.

An incomplete list of photosensitizers currently undergoing human clinical trials.

| Photosensitizer | Trade name | Approval | Excitation (nm) | Drug-light interval | Clearance time | Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porfimer sodium | Photofrin | 1998, 2003 (FDA) | 630 | 48–150 h | 4–6 weeks | Lung, Barrett’s esophagus |

| ALA-PpIX | Levulan Keratastick | 1999 (FDA) | 405, 635 | 14–18 h | ∼2 days | AK |

| Methyl aminolevulate-PpIX | Metvix | 2004 (FDA) | 405, 635 | 3 h | ∼2 days | AK |

| Hexyl aminolevulate-PpIX | Hexvix | 2005 (EU) | 405 | 1–3 h | ∼2 days | Detection of bladder tumors |

| BPD-MA | Verteporfin, Visudyne | 2000 (FDA) | 689 | 15 min | 5 days | CNV |

| mTHPC | Foscan | Phase I trials, 2001 (EU) | 652 | 48–110 h | 15 days | Head and neck, prostate, pancreas, esophagus, mesothelioma |

| Motexafin Lutetium | MLu, Lutex, Lutrin | Phase I trials | 732 | 3 h | Prostate, atherosclerosis | |

| Pd-bacteriopheophorbide | Tookad | Phase I trials | 762 | ∼30 min | ∼2 h | Prostate |

| Taloporfin sodium (mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6) | LS11 | Phase I and II trials | 664 | 1 h | CNV, liver and colorectal metastasis | |

| Silicon pthalocyanine 4 | PC-4 | Phase I trials | 672 | 24–36 h | Skin |

PDT biology

From the point of view of biological response, PDT is fundamentally different from other cancer therapies. Unlike ionizing radiation, PDT achieves its cytotoxic effects primarily though damage to targets other than DNA. The specific subcellular targets damaged by PDT depend on the photosensitizer’s localization within the cell, which varies among photosensitizers and cell lines. Different types of damage can lead to different mechanisms of cell death. Damage to mitochondria in particular can lead to apoptosis even at relatively low light doses.70 Recently, the role of autophagic cell death in PDT has been increasingly recognized.71 In addition to the variation among photosensitizers in their subcellular targets, there is considerable variability in the macroscopic targeting of photosensitizers. Photosensitizers that are retained in the vasculature can destroy tumors via vascular damage rather than direct cell killing. Some photosensitizers may act as vascular agents at short times after injection and at high fluence rates, where only the vasculature is sufficiently oxygenated, and produce direct cell kill at low fluence rates and long times after injection.72 An additional level of complexity arises from the fact that the response to PDT is not confined to the cells where the singlet oxygen is deposited but can involve physiological73 and immunological74, 75 responses as well.

CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS

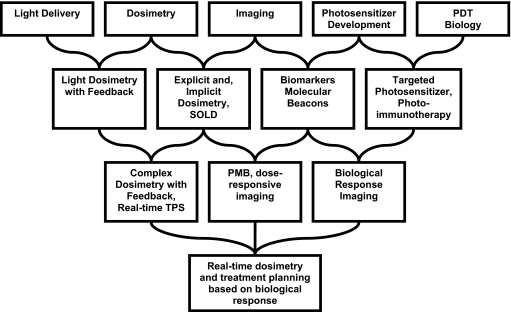

Much of the research in the early decades of PDT and its related fields proceeded in five almost independent areas, as illustrated in the top row of Fig. 2. The problems associated with light source and light delivery system development, dosimetry, and optical imaging were treated as physics problems, while photosensitizer development and PDT biology were treated as problems of chemistry and biology, respectively. In recent years, however, the most promising advances have come out of interdisciplinary collaborations among these areas. The systems and strategies currently in preclinical and clinical trials are examples of such collaborations.

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the progress of PDT development from a set of disparate fields (top row) to a collaborative effort unifying the contributions of biologists, chemists, physicists, and engineers. The second row illustrates the current state of art of research and represents integration of two separate fields. The third row illustrates the future research direction and the fourth row is the ultimate integration of all disparate fields. See text for a complete description.

Light dosimetry with real-time feedback

It is very difficult to assess the efficacy and toxicity of any treatment in a clinical trial without a rigorous quantitative measurement of the treatment given. One reason that radiotherapy has become an accepted locoregional therapy is that the dose to tissues has been quantified accurately and curative doses can be delivered safely. In our current clinical trials, we deliver a dose of light to the treatment sites based upon measurements made from implanted isotropic light detectors.34, 76 These detectors allow us to prescribe the light dose based upon actual measurements in the prostate rather than the output of the laser. This dosimetric approach also ensures that the same amount of light energy (as measured by the isotropic detectors) is deposited uniformly in the prostate within each cohort of patients as a specific dose level.

The measurement of light fluence in vivo is necessary but not sufficient to optimize the light fluence distribution. Optimization of the light fluence depends upon accurate calculation of the light fluence rate in the entire prostate volume, which in turn requires accurate characterization of the in vivo prostate optical properties as input. Many studies have been conducted to determine the in vivo optical properties of human prostate.77, 78, 79 These light fluence measurements show that the optical properties of the prostate vary substantially within a prostate gland as well as among separate prostate glands. The optical properties of prostate tissue may also vary over time during a PDT procedure.

The state of the art for prostate PDT uses only in vivo light fluence rate monitoring to determine the light fluence using equal weight of linear light sources. This is not sufficient since light fluence at only selected points are known. Integrating ultrasound imaging and the PDT dose calculation engine into the PDT delivery system, with input of tissue optical properties and drug uptake, will allow the clinician to optimize the weight of each light-delivery fiber, and thus improve the light fluence distribution in the prostate gland. Adequate treatment planning often uses various optimization engines to optimize the distribution of light source intensities.

Implicit dosimetry and dosimetric imaging

The most commonly cited example of implicit dosimetry is fluorescence photobleaching. Wilson31 suggested that the photobleaching of the photosensitizer, if moderated by the same mechanism as the photodynamic effect, could indicate the extent of damage. The theoretical basis for quantitative implicit dosimetry using fluorescence photobleaching was formalized by Georgakoudi et al.18 for the case of multicell tumor spheroids. Fluorescence photobleaching has been used in animal models to investigate the fluence-rate dependence of photodynamic therapy80, 81, 82 and has been shown to correlate with visible skin damage.83 A device for skin PDT dosimetry using photobleaching has been developed for use in clinical trials84 and work to extend the spheroid models to realistic tissues is ongoing.85

Fluorescence photobleaching is relatively inexpensive and straightforward to implement, however, its quantitative interpretation involves several challenges. First, fluorescence measurement in vivo must always account for the confounding effects of light scattering and absorption. Second, the validity of the relationship between fluorescence photobleaching and reacted singlet oxygen dose assumes that the photobleaching is mediated primarily by singlet oxygen reaction with the photosensitizer. There is experimental evidence to suggest that other bleaching mechanisms may be important for the commonly used photosensitizers Photofrin®82 and ALA-induced PpIX,86 and the in vivo photobleaching of mTHPC exhibits features that are not readily interpretable.81 Care should therefore be exercised in using photobleaching as a dose metric.

Two methods have been developed for the detection of singlet oxygen itself. Qin et al. have demonstrated a chemoluminescent compound that emits light in the presence of singlet oxygen.87 The translation of this technology into patients will require the development of a nontoxic, singlet-oxygen-specific chemoluminescent probe that distributes uniformly in tissue.

Direct measurement of singlet oxygen can be accomplished via detection of its 1270 nm phosphorescence emission, a technique known as singlet oxygen luminescence dosimetry (SOLD).88 Detection of this signal presents significant technical challenges due to the long wavelength of the emission and the weak signal. Jarvi et al.88 have developed a system based on a photomultiplier tube capable of detecting the long-wavelength emission of singlet oxygen. The emission is stimulated by a pulsed laser at the treatment wavelength, and a time-resolved measurement of the emitted signal allows determination of the singlet oxygen lifetime in the system being measured. An additional challenge is the interpretation of the singlet oxygen phosphorescence signal. The phosphorescence emission arises from a transition of oxygen from its singlet state to its ground state. This process therefore competes with the reaction of singlet oxygen with cellular and extracellular substrates. This leads to an increase in phosphorescence emission in conditions where substrates for singlet oxygen are not plentiful. To differentiate between the cellular signal corresponding to PDT effect and the extracellular signal, the time-resolved emission signal can be fit as a sum of signals with different lifetimes.

Biomarkers and molecular beacons

Because the goal of PDT is ultimately to deliver the optimal treatment to the tumor, the idea of using noninvasive detection and imaging to determine the status of tumor cells at the molecular level is very attractive. This concept has driven the development of molecular beacons, molecules that target specific molecular pathways that can be imaged using, for instance, near-infrared fluorescence. Steflova et al. have developed a series of molecular beacons whose fluorescence is quenched in their latent state and restored under the action of specific cellular processes of interest.89 Because these beacons target specific molecules, it is likely that they will be tumor-type specific, however, the variety of cellular processes that can potentially be imaged using this approach makes it very promising. Molecular beacons are a subset of the general category of cancer biomarkers, molecules which allow imaging of specific biological processes via various modalities including MRI, PET,90 and optical imaging.

Enhancement and targeting of photosensitizers

Several researchers have developed methods for enhancing the ability of a photosensitizer to target tumors. One strategy to accomplish this is to optimize the timing the administration of light to coincide with the desired distribution of the photosensitizer.72 This approach has been used to target vasculature by applying light while the photosensitizer is in circulation, for the treatment of AMD using Vertepofin and the prostate using Tookad.12 In cases where the rate of production of singlet oxygen is limited by the vascular resupply of oxygen, changes in the light fluence rate can change the distribution of deposited singlet oxygen, with higher fluence rates leading to preferential targeting of vascular-adjacent tissue. Thus, the combination of drug-light interval and fluence rate can be adjusted to enhance the treatment of the desired tissue type.

A more direct approach to photosensitizer targeting is the conjugation of the photosensitizer to a tumor-selective molecule or particle.91 The last 2 decades have seen tremendous progress in the development of tumor-targeted therapeutic and imaging agents for cancer in general.92, 93 These innovations will continue to inform the development of new photosensitizers targeted to specific tumor types.

Recent research has shown PDT induced increases of VEGF, MMPs, and∕or COX-2 in tumor microenvironment that cause resistance to standard treatment. As a result, combination of therapy that suppresses these growth factors has been proposed to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of PDT. C225, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR, has been shown to enhance the PDT treatment in ovarian cancer.94, 95 Other combined modalities seek to target treatment-induced angiogenesis and∕or inflammation to enhance the effectiveness of PDT.96

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS AND PREDICTIONS

We predict that future developments in PDT will continue the trend toward interdisciplinary work and the inclusion of more technologies and subfields, such as imaging, novel drug design, and biological modeling into the treatment planning and dosimetry processes. Below are a few predictions of future PDT physics research directions:

Light sources: Faster, cheaper, larger, smaller

A significant driver in the development of new light sources has been the advent of inexpensive, reliable diode lasers and light-emitting diodes. Diode light sources have already been made small enough to be implantable.97 We predict that this trend will continue, with future light sources becoming ever smaller, cheaper, and more efficient. On the other hand, the increases in efficiency of these light sources will also lead to lasers with greater total power output, allowing the treatment of larger volumes of tissue using a single source.

Simple increases in power are not the only advances we can expect from future light sources. New delivery systems will incorporate mechanisms to deliver a light distribution customizable to each patient’s treatment plan. In our group, we have developed a computer-controlled attenuator system for prostate PDT designed to adjust the intensities of up to 16 implanted interstitial diffusing fibers independently and in real time.98 Lilge et al. have investigated optical diffusing fibers whose emission profiles along the fiber axis can be customized to deliver much more complex light distributions than conventional diffusers.99, 100 We expect further developments in this direction to allow more and more precise control of the in vivo light distribution during PDT.

Real-time oxygen monitoring

While it has long been recognized that oxygenation of the target tissue is essential to PDT, measurements of oxygenation are now starting to be implemented in preclinical and clinical trials. We anticipate that future clinical protocols involving real-time dosimetry will also include real-time oxygen monitoring, both to prevent PDT-induced hypoxia and to take advantage of the predictive value of PDT-induced changes in blood flow and hemoglobin oxygen saturation.58 The monitoring of hemoglobin saturation and blood flow has been demonstrated in clinical trials.101 The translation of measurements of hemoglobin oxygenation into a determination of the cellular oxygen concentration requires a model of oxygen diffusion and consumption. The development of such models is ongoing and will inform future dosimetry developments.85

An alternative to hemoglobin monitoring is the use of time-resolved SOLD measurements. A sufficiently sophisticated analysis of the time dependence of the SOLD signal allows determination of the photosensitizer triplet lifetime, which is related to the local oxygen concentration. Hence, SOLD has the potential to provide both a measure of reacted singlet oxygen dose and a measure of the molecular oxygen concentration at the point of singlet oxygen generation.88 This approach has the additional advantage from the point of view of explicit dosimetry of providing an intermediate verification of the triplet lifetime predicted by the dosimetric model.

Multifunctional, multimodality photosensitizers

Another area of active research in photodynamic therapy is the development of photosensitizers and photosensitizer delivery systems that enhance the functionality of the photosensitizer.102 For instance, a photosensitizer may be linked to a fluorescent molecule to enhance its delectability under fluorescence imaging.103 Pandey et al.104 have proposed combining photosensitizers with contrast agents for optical, MRI and PET imaging, allowing image-guided PDT treatment. Zheng et al. have combined the “molecular beacon” concept with a photosensitizer to produce photodynamic molecular beacons.105 These molecules exhibit quenching that suppresses their production of 1O2 in their latent state. They can be activated by interaction with a tumor-specific molecular marker, in this case the matrix metalloproteinase MMP-7. The clinical implementation of strategies such as these has the potential to dramatically improve the targeting of the photosensitizer to the tumor. An essential component of any targeting strategy will be the ability to verify the targeting of the drug to the desired target. The distribution of the photosensitizer can be determined optically using fluorescence or absorption imaging. In addition, detailed models of the distributions and kinetics of light, photosensitizer, and oxygen will provide a quantitative relationship between the microscopic distribution and photochemical properties of the drug and the macroscopically observed treatment response.106 In cases where the drug is activated by an endogenous agent, the results will be predictable only using such sophisticated models.

Treatment planning integrated with dosimetry, imaging, and light delivery devices to allow adaptive treatment

The integration of dosimetry systems with multimodality imaging (anatomic and DOT) and light delivery devices into an integrated system has drawn great interest recently. Several groups are developing integrated systems to control light delivery, real-time light monitoring, and volumetric light fluence calculation. The group in Lund, Sweden is developing a multiple channel system of point sources that can be used as either light sources or detectors.107 A personal computer controls the position and duration of the point sources to optimize light fluence distribution. Another group in Toronto, Canada has commercialized a four-channel light source with computerized power control in each channel. Our group has developed an integrated system that incorporates PDT dosimetry that include light fluence rate at multiple points,108 a three-dimensional map of optical properties,46 drug concentration distribution,56 and tissue oxygenation.98 A kernel-based algorithm was developed to calculate light fluence rate distribution in the optically heterogeneous prostate gland,109 which, coupled with an optimization engine allows optimization of light source powers to achieve a uniform light fluence distribution.110, 98 This area of research will evolve into a totally computerized delivery, monitoring, and dosimetry system for real-time feedback control.

New dosimetry quantities based on modeling of the dynamic system

The current state of art in PDT dosimetry is to explicitly determine the quantity PDT dose, defined as the number of photons absorbed by photosensitizing drug per gram of tissue.111 While this quantity takes into account the consumption of photosensitizer, it does not consider the effect of tissue oxygenation on the quantum yield of oxidative radicals. Thus, it is only applicable in cases where ample oxygen supplies exist. It is anticipated that new dosimetry quantities based on reacted singlet oxygen [1O2]rx, e.g., a product of singlet oxygen quantum yield and PDT dose, can be used to account for kinetics of the oxygen consumption during PDT process.23 Foster et al. have determined most of fundamental parameters necessary for microscopic model of the oxygen consumption during PDT.18, 82, 106, 112 However, when applying models developed in the microscopic scale to a macroscopic environment, the values of many parameters may change, and many parameters may be observable only in the volume average, so extensive study will be required to determine the values for each specific photosensitizer.

Physiological effects of PDT will be exploited to develop systemic therapy

The ability of PDT to elicit an immune response has been recognized for some time.75 The past decade has seen dramatic progress in our understanding of the mechanisms of PDT-induced immune response.74, 113 In addition it has been demonstrated that PDT can be used to generate vaccines against specific tumor types.114, 115 This strategy is particularly attractive for the treatment of cancer, where it is likely that PDT will be used in combination with radiation and chemotherapy, both of which can have immunosuppressive effects.

As the details of the mechanisms of the immune response are better understood, it is likely that new photosensitizers and delivery mechanisms will be developed for the express purpose of enhancing the immunological response and∕or moderate treatment induced angiogenesis and inflammation. Furthermore, the parameters which optimize immune response to PDT will be different from those that maximize singlet oxygen dose or direct cell killing.116 Therefore, there will be an increasing need for the incorporation of these effects into PDT treatment planning and dosimetry. We predict that PDT vaccines will find a use as an adjuvant therapy, even in cases where the tumor location or geometry precludes conventional PDT as a primary treatment. In these cases, it may be possible to perform PDT on ex vivo tissue or cell cultures, in which case the problems of light propagation and tumor physiology are greatly simplified, allowing a level of treatment optimization not feasible in vivo.

CONCLUSIONS

We have predicted that PDT research will increasingly rely on combinations of widely varied fields, leading to more and more sophisticated treatment protocols. It is tempting to assume that such therapies will become so complex that they can only be modeled empirically, and that the role of physics will diminish. However, the history of PDT research demonstrates that many advances in the field are made not by avoiding the complexity of the problem but by embracing it. As we exploit our growing knowledge of the underlying photochemistry, biology, and physiology of PDT to develop new and better treatments, it will be more important than ever to understand and optimize those treatment parameters over which we have direct control. In the future, as in the past, it will be the understanding of the physics of PDT that will allow us to take advantage of our scientific understanding and translate it into improved clinical treatments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) Grant Nos. P01 CA87971 and R01 CA109456.

References

- Dougherty T. J., Gomer C. J., Henderson B. W., Jori G., Kessel D., Korbelik M., Moan J., and Peng Q., “Photodynamic therapy,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889 90, 889–905 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M. A., “Photodynamic therapy and the treatment of head and neck cancers,” J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 14, 239–244 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant W. E., Speight P. M., Hopper C., and Bown S. G., “Photodynamic therapy: an effective, but non-selective treatment for superficial cancers of the oral cavity,” Int. J. Cancer 71, 937–942 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg J. S., Mick R., Steveson J. P., Zhu T., Busch T. M., Shin D., Smith D., Culligan M., Dimofte A., Glatstein E., and Hahn S. M., “A phase II trial of pleural photodynamic therapy (PDT) and surgery for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with pleural spread,” J. Clin. Oncol. 22, 2192–2201 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskal T. L., Dougherty T. J., Urschel J. D., Antkowiak J. G., Regal A. M., Driscoll D. L., and Takita H., “Operation and photodynamic therapy for pleural mesothelioma: 6-year follow-up,” Ann. Thorac. Surg. 66, 1128–1133 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pass H. I. et al. , “Intrapleural photodynamic therapy: Results of a phase I trial,” Ann. Surg. Oncol. 1, 28–37 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedberg J. S., Mick R., Stevenson J., Metz J., Zhu T., Buyske J., Sterman D. H., Pass H. I., Glatstein E., and Hahn S. M., “A phase I study of Foscan-mediated photodynamic therapy and surgery in patients with mesothelioma,” Ann. Thorac. Surg. 75, 952–959 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackroyd R., Brown N. J., Davis M. F., Stephenson T. J., Marcus S. L., Stoddard C. J., Johnson A. G., and Reed M. W., “Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: A prospective, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial,” Gut 10.1136/gut.47.5.612 47, 612–617 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjehpour M., Overholt B. F., Haydek J. M., and Lee S. G., “Results of photodynamic therapy for ablation of dysplasia and early cancer in Barrett’s esophagus and effect of oral steroids on stricture formation,” Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95, 2177–2184 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan T. R., Whitelaw D. E., Chang S. C., Lees W. R., Ripley P. M., Payne H., Jones L., Parkinson M. C., Emberton M., Gillams A. R., Mundy A. R., and Browen S. G., “Photodynamic therapy for prostate cancer recurrence after radiotherapy: A phase I study,” J. Urol. 168, 1427–1432 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stripp D., Mick R., Zhu T. C., Whittington R., Smith D., Dimofte A., Finlay J. C., Miles J., Busch T. M., Shin D., Kachur A., Tochner Z., Malkowicz S. B., Glatstein E., and Hahn S. M., “Phase I trial of Motexfin Lutetium-mediated interstitial photodynamic therapy in patients with locally recurrent prostate cancer,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.529181 5315, 88–99 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersink R. A., Bogaards A., Gertner M., Davidson S. R., Zhang K., Netchev G., Trachtenberg J., and Wilson B. C., “Techniques for delivery and monitoring of TOOKAD (WST09)-mediated photodynamic therapy of the prostate: clinical experience and practicalities,” J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 79, 211–222 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal M. A., Kayar B., Hill J. S., Morgan D. J., Nation R. L., Stylli S. S., Basser R. L., Uren S., Geldard H., Green M. D., Kahl S. B., and Kaye A. H., “Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of photodynamic therapy for high-grade gliomas using a noval boronated porphyrin,” J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 519–524 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodell T. T. and Muller P. J., “Photodynamic therapy: A novel treatment for primary brain malignancy,” J. Neurosci. Nurs. 33, 296–300 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaards A., Varma A., Zhang K., Zach D., Bisland S. K., Moriyama E. H., Lilge L., Muller P. J., and Wilson B. C., “Fluorescence image-guided brain tumour resection with adjuvant metronomic photodynamic therapy: Pre-clinical model and technology development,” Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 10.1039/b414829k 4, 438–442 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson M. J., Christiansen O., Jensen F., and Ogilby P. R., “Overview of theoretical and computational methods applied to the oxygen-organic molecule photosystem,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2006-03-17-IR-851 82, 1136–1160 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster T. H., Hartley D. F., Nichols M. G., and Hilf R., “Fluence rate effects in photodynamic therapy of multicell tumor spheroids,” Cancer Res. 53, 1249–1254 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakoudi I., Nichols M. G., and Foster T. H., “The mechanism of Photofrin photobleaching and its consequences for photodynamic dosimetry,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb01889.x 65, 135–144 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson S. L., VanDerMeid K. R., Murant R. S., Raubertas R. F., and Hilf R., “Effects of various photoradiation regimens on the antitumor efficacy of photodynamic therapy for R3230AC mammary carcnimoas,” Cancer Res. 50, 7236–7241 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. W., Busch T. M., Vaughan L. A., Frawley N. P., Babich D., Sosa T. A., Zollo J. D., Dee A. S., Cooper M. T., Bellnier D. A., Greco W. R., and Oseroff A. R., “Photofrin photodynamic therapy can significantly deplete or preserve oxygenation in human basal cell carcinomas during treatment, depending on fluence rate,” Cancer Res. 60, 525–529 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. W., Busch T. M., and Snyder J. W., “Fluence rate as a modulator of PDT mechanisms,” Lasers Surg. Med. 10.1002/lsm.20327 38, 489–493 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. H., Feng Y., Lu J. Q., Allison R. R., Cuenca R. E., Downie G. H., and Sibata C. H., “Modeling of a type II photofrin-mediated photodynamic therapy process in a heterogeneous tissue phantom,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2005-05-04-RA-513 81, 1460–1468 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T. C., Finlay J. C., Zhou X., and Li J., “Macroscopic modeling of the singlet oxygen production during PDT,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.701387 6427, 642708–642720(2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. C. and Patterson M. S., in Photodynamic Therapy of Neoplastic Disease, edited by Kessel D. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1990), Vol. 1, pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Almond P. R., Photodynamic Therapy Equipment and Dosimetry (American Institute of Physics, Woodbury, NY, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru A., Wave Propagation and Scattering in Random Media (IEEE, New York, 1997). [Google Scholar]

- Cong W., Wang L. V., and Wang G., “Formulation of photon diffusion from spherical bioluminescent sources in an infinite homogeneous medium,” Biomed. Eng. Online 3, 12 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskell R. C., Svaasand L. O., Tsay T. -T., Feng T. -C., McAdams M. S., and Tromberg B. J., “Boundary conditions for the diffusion equation in radiative transfer,” J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 11, 2727–2741 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Jacques S. L., and Zheng L., “MCML-Monte Carlo modeling of light transport in multi-layered tissues,” Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 10.1016/0169-2607(95)01640-F 47, 131–146 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duderstadt J. J. and Martin W. R., Transport Theory (Wiley, New York, 1979). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. C., Patterson M. S., and Lilge L., “Implicit and explicit dosimetry in photodynamic therapy: A new paradigm,” Lasers Med. Sci. 12, 182–199 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendren S. K., Hahn S. M., Spitz F. R., Bauer T. W., Rubin S. C., Zhu T., Glatstein E., and Fraker D. L., “Phase II trial of debulking surgery and photodynamic therapy for disseminated intraperitoneal tumors,” Ann. Surg. Oncol. 8, 65–71 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijnissen J. P. and Star W. M., “Performance of isotropic light dosimetry probes based on scattering bulbs in turbid media,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/47/12/304 47, 2049–2058 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulcan T. G., Zhu T. C., Rodriguez C. E., Hsi A., Fraker D. L., Baas P., Murrer L. H., Star W. M., Glatstein E., Yodh A. G., and Hahn S. M., “Comparison between isotropic and nonisotropic dosimetry systems during intraperitoneal photodynamic therapy,” Lasers Surg. Med. 26, 292–301 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijnissen J. P. and Star W. M., “Calibration of isotropic light dosimetry probes based on scattering bulbs in clear media,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/41/7/008 41, 1191–1208 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hielscher A. H., Bluestone A. Y., Abdoulaey G. S., Klose A. D., Lasker J., Stewart M., Netz U., and Beuthan J., “Near-infrared diffuse optical tomography,” Dis. Markers 18, 313–337 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Miller E. L., Kilmer M. E., Brukilacchio T. J., Chaves T., Stott J., Zhang Q., Wu T., Chorlton M., Moore R. H., Kopans D. B., and Boas D. A., “Tomographic optical breast imaging guided by three-dimensional mammography,” Appl. Opt. 10.1364/AO.42.005181 42, 5181–5190 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J. P., Choe R., Holboke M. J., Zubkov L., Durduran T., Slemp A., Ntziachristos V., Chance B., and Yodh A. G., “Three-dimensional diffuse optical tomography in the parallel plane transmission geometry: Evaluation of a hybrid frequency domain/continuous wave clinical system for breast imaging,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.1534109 30, 235–247 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holboke M. J., Tromberg B. J., Li X., Shah N., Fishkin J., Kidney D., Butler J., Chance B., and Yodh A. G., “Three-dimensional diffuse optical mammography with ultrasound localization in a human subject,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10.1117/1.429992 5, 237–247 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S., Pogue B. W., Jiang S., Dehghani H., Kogel C., Soho S., Gibson J. J., Tosteson T. D., Poplack S. P., and Paulsen K. D., “In vivo hemoglobin and water concentrations, oxygen saturation, and scattering estimates from near-infrared breast tomography using spectral reconstruction,” Acad. Radiol. 13, 195–202 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooksby B., Jiang S., Dehghani H., Pogue B. W., Paulsen K. D., Weaver J., Kogel C., and Poplack S. P., “Combining near-infrared tomography and magnetic resonance imaging to study in vivo breast tissue: implementation of a Laplacian-type regularization to incorporate magnetic resonance structure,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10.1117/1.2098627 10, 051504–051514(2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue B. W., Poplack S. P., McBride T. O., Wells W. A., Osterman K. S., Osterberg U. L., and Paulsen K. D., “Quantitative hemoglobin tomography with diffuse near-infrared spectroscopy: Pilot results in the breast,” Radiology 218, 261–266 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J. P., Siegel A. M., Stott J. J., and Boas D. A., “Volumetric diffuse optical tomography of brain activity,” Opt. Lett. 10.1364/OL.28.002061 28, 2061–2063 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver J. P., Durduran T., Furuya D., Cheung C., Greenberg J. H., and Yodh A. G., “Diffuse optical tomography of cerebral blood flow, oxygenation, and metabolism in rat during focal ischemia,” J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076703.71231.BB 23, 911–924 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Iftimia N., Jiang H., Key L. L., and Bolster M. B., “Three-dimensional diffuse optical tomography of bones and joints,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10.1117/1.1427336 7, 88–92 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T. C. and Finlay J. C., “Prostate PDT dosimetry,” Photodiagnosis Photodynamic Therapy 3, 234–246 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Zhu T. C., Finlay J. C., Li J., Dimofte A., and Hahn S., “Two-dimensional/three dimensional hybrid interstitial diffuse optical tomography of human prostate during photodynamic therapy: Phantom and clinical results,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.701717 6434, 64341Y–64352Y (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Liengsawangwong R., Choi H., and Cheung R., “Using a priori structural information from magnetic resonance imaging to investigate the feasibility of prostate diffuse optical tomography and spectroscopy: A simulation study,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2400614 34, 266–274 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. and Zhu T. C., “Interstitial diffuse optical tomography using an adjoint model with linear sources,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.762340 6845, 68450C–68459C(2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low A. F., Tearney G. J., Bouma B. E., and Jang I. K., “Technology Insight: optical coherence tomography–Current status and future development,” Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 3, 154–162 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogue B. W., Davis S. C., Song X., Brooksby B. A., Dehghani H., and Paulsen K. D., “Image analysis methods for diffuse optical tomography,” J. Biomed. Opt. 10.1117/1.2209908 11, 033001–033017 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson A. P., Hebden J. C., and Arridge S. R., “Recent advances in diffuse optical imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/50/4/R01 50, R1–R43 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards-Kortum R. and Sevick-Muraca E., “Quantitative optical spectroscopy for tissue diagnosis,” Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.47.1.555 47, 555–606 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson B., Jerjes W., El-Maaytah M., Norris P., and Hopper C., “Optical techniques in diagnosis of head and neck malignancy,” Oral Oncol. 42, 221–228 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigio I. J. and Bown S. G., “Spectroscopic sensing of cancer and cancer therapy: current status of translational research,” Cancer Biol. Ther. 3, 259–267 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay J. C., Zhu T. C., Dimofte A., Stripp D., Malkowicz S. B., Busch T. M., and Hahn S. M., “Interstitial fluorescence spectroscopy in the human prostate during motexafin lutetium-mediated photodynamic therapy,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2005-10-04-RA-711 82, 1270–1278 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. V., “The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of hemoglobin on its dissociation curves,” J. Physiol. (Proc.) 40, iv–vii (1910). [Google Scholar]

- Yu G., Durduran T., Zhou C., Wang H. W., Putt M. E., Saunders H. M., Sehgal C. M., Glatstein E., Yodh A. G., and Busch T. M., “Noninvasive monitoring of murine tumor blood flow during and after photodynamic therapy provides early assessment of therapeutic efficacy,” Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 3543–3552 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. W., Putt M. E., Emanuele M. J., Shin D. B., Glatstein E., Yodh A. G., and Busch T. M., “Treatment-induced changes in tumor oxygenation predict photodynamic therapy outcome,” Cancer Res. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3632 64, 7553–7561 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenbaum M. C., Akande S. L., Bonnett R., Kaur H., Ioannou S., White R. D., and Winfield U. J., “Meso-tetra(hydroxyphenyl)porphyrins, a new class of potent tumour photosensitisers with favourable selectivity,” Br. J. Cancer 54, 717–725 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Geel I. P., Oppelaar H., Oussoren Y. G., van der Valk M. A., and Stewart F. A., “Photosensitizing efficacy of mTHPC-PDT compared to photofrin-PDT in the RIF1 mouse tumour and normal skin,” Int. J. Cancer 60, 388–394 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauschning W., Tan I. B., and Dolivet G., “Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with mTHPC in the palliation of advanced head and neck cancer in patients who have failed prior therapies and are unsuitable for radiatiotherapy, surgery or systemic chemotherapy,” J. Clin. Oncol. 22(14), 5596 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Biel M., “Advances in photodynamic therapy for the treatment of head and neck cancers,” Lasers Surg. Med. 38, 349–355 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovat L. B., Jamieson N. F., Novelli M. R., Mosse C. A., Selvasekar C., Mackenzie G. D., Thorpe S. M., and Bown S. G., “Photodynamic therapy with m-tetrahydroxyphenyl chlorin for high-grade dysplasia and early cancer in Barrett’s columnar lined esophagus,” Gastrointest. Endosc. 62, 617–623 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne J., Dorme N., Bourg-Heckly G., Raimbert P., and Flejou J. F., “Photodynamic therapy with green light and m-tetrahydroxyphenyl chlorin for intramucosal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus,” Gastrointest. Endosc. 59, 880–889 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. M., Nathan T. R., Lees W. R., Mosse C. A., Freeman A., Emberton M., and Bown S. G., “Photodynamic therapy using meso tetra hydroxy phenyl chlorin (mTHPC) in early prostate cancer,” Lasers Surg. Med. 10.1002/lsm.20275 38, 356–363 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira S. P., Ayaru L., Rogowska A., Moose A., Hatfield A. R., and Bown S. G., “Photodynamic therapy of malignant biliary strictures using meso-tetrahydroxyphenylchlorin,” Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19, 479–485 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansch A., Frey O., Gajda M., Susanna G., Boettcher J., Brauer R., and Kaiser W. A., “Photodynamic treatment as a novel approach in the therapy of arthritic joints,” Lasers Surg. Med. 40, 265–272 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triesscheijn M., Ruevekamp M., Antonini N., Neering H., Stewart F. A., and Baas P., “Optimizing meso-tetra-hydroxyphenyl-chlorin-mediated photodynamic therapy for basal cell carcinoma,” Photochem. Photobiol. 82, 1686–1690 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oleinick N. L., Morris R. L., and Belichenko I., “The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy: What, where, why, and how,” Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 10.1039/b108586g 1, 1–21 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buytaert E., Dewaele M., and Agostinis P., “Molecular effectors of multiple cell death pathways initiated by photodynamic therapy,” Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1776, 86–107 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Pogue B. W., Hoopes P. J., and Hasan T., “Vascular and cellular targeting for photodynamic therapy,” Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 16, 279–305 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch T. M., “Local physiological changes during photodynamic therapy,” Lasers Surg. Med. 10.1002/lsm.20355 38, 494–499 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbelik M., “PDT-associated host response and its role in the therapy outcome,” Lasers Surg. Med. 10.1002/lsm.20337 38, 500–508 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbelik M., “Induction of tumor immunity by photodynamic therapy,” J. Clin. Laser Med. Surg. 14, 329–334 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baas P., Murrer L., Zoetmulder F. A., Stewart F. A., Ris H. B., van Zandwijk N., Peterse J. L., and Rutgers E. J., “Photodynamic therapy as adjuvant therapy in surgically treated pleural malignancies,” Br. J. Cancer 76, 819–826 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. K., Whiteburst C., Pantelides M. L., and Moore J. V., “In situ comparison of 665 nm light and 633 nm wavelength light penetration in the human prostate gland,” Photochem. Photobiol. 62, 882–886 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelides M. L., Whitehurst C., Moore J. V., King T. A., and Blacklock N. J., “Photodynamic therapy for localised prostatic cancer: light penetration in the human prostate gland,” J. Urol. 143, 398–401 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T. C., Dimofte A., Finlay J. C., Stripp D., Busch T., Miles J., Whittington R., Malkowicz S. B., Tochner Z., Glatstein E., and Hahn S. M., “Optical properties of human prostate at 732 nm measured in vivo during motexafin lutetium-mediated photodyanmic therapy,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2004-06-25-RA-216.1 81, 96–105 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay J. C., Conover D. L., Hull E. L., and Foster T. H., “Porphyrin bleaching and PDT-induced spectral changes are irradiance dependent in ALA-sensitized normal rat skin in vivo,” Photochem. Photobiol. 73, 54–63 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay J. C., Mitra S., and Foster T. H., “In vivo mTHPC photobleaching in normal rat skin exhibits unique irradiance-dependent features,” Photochem. Photobiol. 75, 282–288 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay J. C., Mitra S., and Foster T. H., “Photobleaching kinetics of Photofrin in vivo and in multicell tumor spheroids indicate multiple simultaneous bleaching mechanisms,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/49/21/001 49, 4837–4860 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson D. J., de Bruijn H. S., van der Veen N., Stringer M. R., Brown S. B., and Star W. M., “Fluorescence photobleaching of ALA-induced protoporphyrin IX during photodynamic therapy of normal hairless mouse skin: The effect of light dose and irradiance and the resulting biological effect,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1998.tb05177.x 67, 140–149 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell W. J., Oseroff A., and Foster T. H., “Portable instrument that integrates irradiation with fluorescence and reflectance spectroscopies during clinical photodynamic therapy of cutaneous disease,” Rev. Sci. Instrum. 10.1063/1.2204617 77, 064302 (2006). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. K.-H., Mitra S., and Foster T. H., “A comprehensive mathematical model of microscopic dose deposition in photodynamic therapy,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2401041 34, 282–293 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dysart J. S. and Patterson M. S., “Photobleaching kinetics, photoproduct formation, and dose estimation during ALA induced PpIX PDT of MLL cells under well oxygenated and hypoxic conditions,” Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 5, 73–81 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y., Xing D., Luo S., Zhou J., Zhong X., and Chen Q., “Feasibility of using fluoresceinyl Cypridina luciferin analog in a novel chemiluminescence method for real-time photodynamic therapy dosimetry,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2005-05-20-RA-536 81, 1534–1538 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvi M. T., Niedre M. J., Patterson M. S., and Wilson B. C., “Singlet oxygen luminescence dosimetry (SOLD) for photodynamic therapy: current status, challenges and future prospects,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2006-05-03-IR-891 82, 1198–1210 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefflova K., Chen J., and Zheng G., “Using molecular beacons for cancer imaging and treatment,” Front. Biosci. 12, 4709–4721 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn H., “PET and SPECT in low-grade glioma,” Eur. J. Radiol. 56, 171–178 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solban N., Rizvi I., and Hasan T., “Targeted photodynamic therapy,” Lasers Surg. Med. 38, 522–531 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrama D., Reisfeld R. A., and Becker J. C., “Antibody targeted drugs as cancer therapeutics,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 147–159 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey R. M. and Goldenberg D. M., “Targeted therapy of cancer: New prospects for antibodies and immunoconjugates,” Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 56, 226–243 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Carmen M. G., Rizvi I., Chang Y., Moor A. C., Oliva E., Sherwood M., Pogue B., and Hasan T., “Synergism of epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted immunotherapy with photodynamic treatment of ovarian cancer in vivo,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97, 1516–1524 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cengel K. A., Hahn S. M., and Glatstein E., “C225 and PDT combination therapy for ovarian cancer: the play’s the thing,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 97, 1488–1489 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomer C. J., Ferrario A., Luna M., Rucker N., and Wong S., “Photodynamic therapy: Combined modality approaches targeting the tumor microenvironment,” Lasers Surg. Med. 38, 516–521 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisland S. K., Lilge L., Lin A., Rusnov R., and Wilson B. C., “Metronomic photodynamic therapy as a new paradigm for photodynamic therapy: Rationale and preclinical evaluation of technical feasibility for treating malignant brain tumors,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2004-03-05-RA-100.1 80, 22–30 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhu T. C., Zhou X., Dimofte A., and Finlay J. C., “Integrated light dosimetry system for prostate photodynamic therapy,” Proc. SPIE 10.1117/12.763806 6845, 68450Q–68458Q (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesselov L., Whittington W., and Lilge L., “Design and performance of thin cylindrical diffusers created in Ge-doped multimode optical fibers,” Appl. Opt. 10.1364/AO.44.002754 44, 2754–2758 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendon A., Weersink R., and Lilge L., “Towards conformal light delivery using tailored cylindrical diffusers: attainable light dose distributions,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/51/23/001 51, 5967–5975 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G., Durduran T., Zhou C., Zhu T. C., Finlay J. C., Busch T. M., Malkowicz S. B., Hahn S. M., and Yodh A. G., “Real-time in situ monitoring of human prostate photodynamic therapy with diffuse light,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2005-10-19-RA-721 82, 1279–1284 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clo E., Snyder J. W., Ogilby P. R., and Gothelf K. V., “Control and selectivity of photosensitized singlet oxygen production: challenges in complex biological systems,” ChemBioChem 8, 475–481 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Gryshuk A., Achilefu S., Ohulchansky T., Potter W., Zhong T., Morgan J., Chance B., Prasad P. N., Henderson B. W., Oseroff A., and Pandey R. K., “A novel approach to a bifunctional photosensitizer for tumor imaging and phototherapy,” Bioconjug. Chem. 16, 1264–1274 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R. K., Goswami L. N., Chen Y., Gryshuk A., Missert J. R., Oseroff A., and Dougherty T. J., “Nature: A rich source for developing multifunctional agents. Tumor-imaging and photodynamic therapy,” Lasers Surg. Med. 10.1002/lsm.20352 38, 445–467 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Chen J., Stefflova K., Jarvi M., Li H., and Wilson B. C., “Photodynamic molecular beacon as an activatable photosensitizer based on protease-controlled singlet oxygen quenching and activation,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8989–8994 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S. and Foster T. H., “Photophysical parameters, photosensitizer retention and tissue optical properties completely account for the higher photodynamic efficacy of meso-tetra-hydroxyphenyl-chlorin vs Photofrin,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1562/2005-02-22-RA-447R.1 81, 849–859 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson A., Axelsson J., Andersson-Engels S., and Swartling J., “Realtime light dosimetry software tools for interstitial photodynamic therapy of the human prostate,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2790585 34, 4309–4321 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T. C., Li J., Finlay J. C., Dimofte A., Stripp D., Malkowicz B. S., and Hahn S. M., “In vivo light dosimetry of interstitial PDT of human prostate,” Proc. SPIE 6139, 61390L–61401L (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. and Zhu T. C., “Determination of in vivo light fluence distribution in heterogeneous prostate during photodyanmic therapy,” Phys. Med. Biol. 10.1088/0031-9155/53/8/007 53, 2103–2114 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler M. D., Zhu T. C., Li J., and Hahn S. M., “Optimized interstitial PDT prostate treatment planning with the Cimmino feasibility algorithm,” Med. Phys. 10.1118/1.2107047 32, 3524–3536 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson M. S., Wilson B. C., and Graff R., “In vivo tests of the concept of photodynamic threshold dose in norma rate liver photosensitized by aluminum chlorosulphonated phthalocyanine,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1990.tb01720.x 51, 343–349 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgakoudi I. and Foster T. H., “Singlet oxygen- versus nonsinglet oxygen-mediated mechanisms of sensitizer photobleaching and their effects on photodynamic dosimetry,” Photochem. Photobiol. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1998.tb09463.x 67, 612–625 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castano A. P., Mroz P., and Hamblin M. R., “Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity,” Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 535–545 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollnick S. O., Vaughan L., and Henderson B. W., “Generation of effective antitumor vaccines using photodynamic therapy,” Cancer Res. 62, 1604–1608 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbelik M. and Sun J., “Photodynamic therapy-generated vaccine for cancer therapy,” Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 55, 900–909 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson B. W., Gollnick S. O., Snyder J. W., Busch T. M., Kousis P. C., Cheney R. T., and Morgan J., “Choice of oxygen-conserving treatment regimen determines the inflammatory response and outcome of photodynamic therapy of tumors,” Cancer Res. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3513 64, 2120–2126 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]