Abstract

C cells are primarily known for producing calcitonin, a hypocalcemic and hypophosphatemic hormone. Nevertheless, besides their role in calcium homeostasis, C cells may be involved in the intrathyroidal regulation of follicular cells, suggesting a possible interrelationship between the two endocrine populations. If this premise is true, massive changes induced by different agents in the activity of follicular cells may also affect calcitonin-producing cells. To investigate the behaviour of C cells in those circumstances, we have experimentally induced two opposite functional thyroid states. We hyperstimulated the follicular cells using a goitrogen (propylthiouracil), and we suppressed thyroid hormone synthesis by oral administration of thyroxine. In both scenarios, we measured T4, TSH, calcitonin, and calcium serum levels. We also completely sectioned the thyroid gland, specifically immunostained the C cells, and rigorously quantified this endocrine population. In hypothyroid rats, not only follicular cells but also C cells displayed hyperplastic and hypertrophic changes as well as increased calcitonin levels. When exogenous thyroxine was administered to the rats, the opposite effect was noted as a decrease in the number and size of C cells, as well as decreased calcitonin levels. Additionally, we noted that the two cell types maintain the same numerical relation (10 ± 2.5 follicular cells per C cell), independent of the functional activity of the thyroid gland. Considering that TSH serum levels are increased in hypothyroid rats and decreased in thyroxine-treated rats, we discuss the potential involvement of thyrotropin in the observed results.

Keywords: C cells, follicular cells, hypothyroidism, paracrine regulation, rat thyroid

Introduction

The thyroid gland has two different endocrine cell populations, namely, follicular cells, the most abundant cells in the gland and responsible for secreting T3 and T4, hormones that control the metabolism; and C cells or parafollicular cells, which are very scarce and primarily known for producing calcitonin, a hypocalcemic and hypophosphatemic hormone. Nevertheless, apart from their role in calcium homeostasis, C cells are probably also involved in the intrathyroidal regulation of follicular cells. This hypothesis is supported by different features, such as their characteristic ‘parafollicular’ position, their predominance in the central region of the thyroid lobe – the so-called C-cell region (McMillan et al. 1985) – and their implication in the secretion of many different regulatory peptides (Scopsi, 1990; Ahrén 1991; Sawicki, 1995). Some of these regulatory peptides display an inhibiting action on thyroid hormone secretion, such as calcitonin, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and somatostatin (Ahrén, 1989, Ahrén 1991; Zerek-Meden et al. 1989), whereas others act as local stimulators of thyroid hormone synthesis, such as gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP), helodermin, and serotonin (Ahrén, 1989; Grunditz et al. 1989; Tamir et al. 1992).

Should interrelationships between follicular cells and C cells exist when massive changes are induced in the activity of follicular cells, as occurs in hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, changes in the population of calcitonin-producing cells would be expected. We have reviewed the literature, both in humans and experimental animals, describing C-cell behaviour in different pathological states of the thyroid gland, but the data are conflicting. In some cases of induced hypothyroidism in rats, a C-cell hyperplasia is described (Peng et al. 1975; Stoll et al. 1978; Usenko et al. 1999), but opposing results are also reported (Bugnon et al. 1978; Logonder-Mlinsek et al. 1985; Zbucki et al. 2007). Similarly, in human pathology, C-cell hyperplastic changes, as well as opposing findings, have been reported in both hypothyroid and hyperthyroid states (Dhillon et al. 1982; Scheuba et al. 2000; Dadan et al. 2001). A possible explanation for the conflicting data, is the general lacking of a rigorous sampling of the thyroid gland, considering that in most species C cells are mainly concentrated in the middle third of each thyroid lobe, the so-called C-cell region (McMillan et al. 1985). The contradictory data on C-cell responses could also be explained by differences among species, treatments, and particularly, the quantification methods used to evaluate this endocrine population by different investigators.

Taking advantage of our research group experience in quantifying C-cell population (Conde et al. 1991, Conde et al. 1995; Martín-Lacave et al. 1992, Martín-Lacave et al. 1999,Martín-Lacave et al. 2002), we have experimentally induced two opposite functional thyroid states in the rat and tried to control all possible variables. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the evolution and behaviour of C cells in relation to follicular cells in different functional alterations of the thyroid gland.

Materials and methods

Animals

Studies were performed using 60 male 2-month-old Wistar rats, randomly separated into six groups of 10 rats each. Two of the groups received a normal diet for 2 and 5 weeks, and were used as control groups (Groups C). Two other groups received a solution containing 0.05% propylthiouracil (PTU; Sigma P3755) in the drinking water for 2 and 5 weeks (Groups PTU). Finally, the remaining two groups received a solution containing 0.012% of thyroxine (T4; Sigma T2376) in the drinking water for 2 and 5 weeks (Groups T4). PTU and thyroxine were prepared according to manufacturer's recommendations. Rats were given a standard laboratory diet and water ad libitum. At the end of the treatment, rats were sacrificed under anesthesia (pentobarbital, 15 mg kg−1, intraperitoneal injection) and blood samples were taken by aortic puncture. Finally, thyroid glands were extracted and immediately fixed by immersion in 4.5% buffered formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Experiments were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, National Academy of Science, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Serum analysis

Thirty minutes after sampling, the blood was centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min and sera stored at −80 °C. The level of free thyroxine was determined with microparticle enzyme immunoassays (MEIA) using an AxSYM analyser (Abbot Diagnostic, USA), with results expressed as ng T4 mL−1 of serum. The levels of serum TSH were determined by radioimmunoassay using the Rat TSH RIA Kit (AH R001, Biocode, USA), with results expressed as ng TSH mL−1 of serum, with a lower detection limit of 1 ng mL−1. The calcitonin level in rat serum was determined by an immunoenzymatic assay using the kit CT-U.S.-EASIA (KAP0421, Biosource, USA), with results expressed as pg CT mL−1 of serum. Serum concentration of total calcium was measured with an automated clinical chemistry analyser (Abbot Diagnostic). All experimental procedures were carried out following manufacturer's protocols.

Immunolocalization of C cells

The thyroid glands were totally cut into 5-µm-thick longitudinal serial sections, and mounted on slides in groups of 10 sections each. The first and last sections of the glands were located by staining the respective slides with hematoxylin-eosin, and the gland thickness was then computed by counting the number of sections between both ends and multiplying this value by 5 µm. Five equidistant levels were then established per gland and the slides containing the selected equidistant thyroid sections were immunostained by the peroxidase-labelled streptavidin-biotin (LSAB) technique to detect the presence of calcitonin. In short, after deparaffination and rehydration, sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for inhibition of endogenous peroxidase, washed in PBS, sequentially incubated with a blocking reagent for 15 min, followed by specific rabbit antiserum anti-calcitonin (DAKO A-576, Denmark), at 1 : 2000 dilution (overnight at 4 °C), then biotinylated antiserum to rabbit/mouse immunoglobulins (DAKO, LSAB2, CA, USA) for 30 min, and then streptavidin-peroxidase complex (DAKO, LSAB2) for 30 min. Washing in PBS (three 3-min changes each) was performed after each incubation. Peroxidase activity was developed using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as chromogen (Sigma), and hydrogen peroxide as substrate. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted. For negative controls, incubation with the specific antibody was omitted.

Stereological methods

The volume of at least a thyroid lobe per gland was determined using an approach to Cavalieri's principle, as we have previously described (Conde et al. 1991). The same method was used to calculate the corresponding volume of the central region of each thyroid lobe, the ‘C-cell region’, where all C cells are concentrated. To calculate the volume fraction (Vv) of the different histological components (follicular cells, C cells, colloid and interstitium) in the ‘C-cell region’, a morphometric analysis was performed using Weibel's multipurpose test system (Weibel, 1979) under an objective magnification of ×40, at the different equidistant sections selected per gland, following our previously described methods (Conde et al. 1991). Once the thyroid lobe volume and the Vv of each thyroid component were established, the absolute volumes occupied by follicular cells and C cells, respectively, were determined.

To determine the average cell areas of both C cells and follicular cells, we chose a total of 100 cells of each type from the equidistant slides immunostained for calcitonin per animal, selecting only those cells containing a nuclear profile. The cell areas were measured with an image analyzer (KONTRON, Messgerate GMBH) using projections of the thyroid sections enlarged 1500 times with a Zeiss microprojector. Once the C-cell area was established, the C-cell volume (VCC), the number of C cells per thyroid lobe (NCC) and their numerical density in the ‘C-cell region’ (NvCC) were calculated according to the method we have previously reported (Conde et al. 1995).

Accordingly, the corresponding volume of follicular cells (VFC) was estimated from the measured follicular-cell areas, taking into account their parallepipedic shape. Subsequently, the total number of follicular cells (NFC) and their numerical density (NvFC) in the ‘C-cell region’ of every thyroid lobe were calculated. The numerical relation between the two endocrine cell populations was finally computed.

Statistical analysis

For analysis of sera, statistical comparisons between control and various experimental groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (anova), followed by the Fisher test for parametric data. Morphometric data were compared using the Student's test. Values of probability less than 0.05 were considered significant. Results are expressed as mean values ± SD.

Results

Evaluation of the thyroidal status in experimental animals

To test the effectiveness of the treatments, we measured the serum concentrations of thyroxine and TSH in all experimental animals. As seen in Table 1, when PTU was administered, a hypothyroid state was induced in the rats, characterized by a dramatic decrease in T4 level and a significant increase in the TSH concentration, which was more pronounced after 5 weeks of treatment. As a result, it could be expected that the thyroid glands in goitrous animals became hyperstimulated by TSH, although low levels of thyroid hormone were eventually secreted. The opposite situation occurred when exogenous thyroxine was administered, because T4levels rose considerably, whereas serum TSH level significantly decreased. In this case, we can deduce that the functional activity of the thyroid gland was practically suppressed.

Table 1.

Variation of different parameters (rat weight, thyroid lobe volume, serum hormones and calcium) with thyroid status

| Groups of animals | Time of treatment | Body weight (g) | Thyroid volume (mm3) | T4 (ng mL−1) | TSH (ng mL−1) | Ca++ (mmol L−1) | CT (pg mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2 weeks (n = 10) | 404 ± 47 | 2.9 ± 0.89 | 59 ± 8 | 1.44 ± 0.60 | 3.06 ± 0.13 | 2.75 ± 1.61 |

| 5 weeks (n = 10) | 480 ± 46 | 2.83 ± 0.51 | 69 ± 9 | 1.27 ± 0.11 | 3.01 ± 0.07 | 4.06 ± 0.63 | |

| PTU | 2 weeks (n = 10) | 336 ± 15 | 7.04 ± 0.95*** | 29 ± 6** | 11.96 ± 1*** | 3.10 ± 0.12 | 6.43 ± 3.36* |

| 5 weeks (n = 10) | 321 ± 52* | 9.07 ± 1.72*** | 53 ± 1* | 25 ± 2.89*** | 2.94 ± 0.15 | 4.80 ± 2.14 | |

| Thyroxine | 2 weeks (n = 10) | 381 ± 45 | 1.57 ± 0.67** | 213 ± 39*** | 1.05 ± 0.80 | 2.94 ± 0.15 | 2.22 ± 0.96 |

| 5 weeks (n = 10) | 458 ± 71 | 1.73 ± 0.55*** | 257 ± 17*** | 0.37 ± 0.05** | 3.06 ± 0.08 | 2.72 ± 1.97 |

Means ± SD;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001 vs. control animals.

Because an objective of the present study was to observe the behaviour of C cells under these experimental conditions, it was necessary to assure that calcium levels did not change throughout the treatment to discard possible interferences. In fact, all the rats were normocalcemic, independent of whether they received PTU or thyroxine for 2 or 5 weeks. The following step was to evaluate the influence of the different thyroidal status on the level of serum calcitonin. As noted in Table 1, the hypothyroid rats showed an increase in the concentration of calcitonin compared to controls that was only significant after 2 weeks’ treatment, apparently returning to normal by 5 weeks. However, when thyroid activity was reduced by exogenous thyroxine, calcitonin levels slightly decreased, although these data were not statistically significant, probably as a consequence of interanimal differences considering the reduced sample size (n = 10). So, we can conclude that a hypercalcitonism appeared exclusively in PTU-treated rats.

Changes on the thyroid glands and their histological components with treatments

In relation to the effect of the treatments on the size of thyroid glands, there was a significant increase in the volume of both thyroid lobes in hypothyroid rats (Group PTU), whereas a significant decrease in T4-treated rats was found (Table 1). The average volumes of the corresponding ‘C-cell regions’ followed a parallel evolution (data not shown), whose tendency could be observed in Fig. 1. The changes in the Vv of the different thyroid components, with treatment, are presented in Table 2. As could be expected, we have found an opposing tendency in the proportions of follicular components and interstitium (connective tissue and blood vessels) between PTU- and thyroxine-treated rats in comparison with controls. In hypothyroid animals, follicular cells and interstitium significantly increased, whereas colloid decreased, whereas just the opposite changes were found in a less active state after thyroxine treatment. Furthermore, compared to controls, there was a significant decrease in the volume fraction of C cells in both experimental groups.

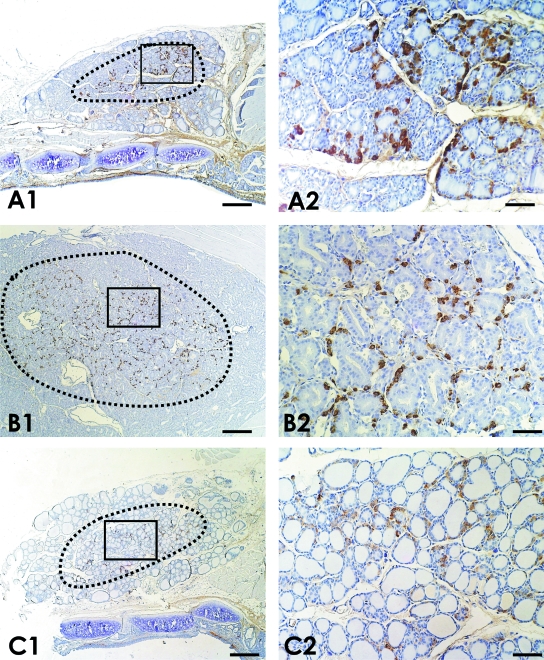

Fig. 1.

Low-power images obtained from longitudinal sections of thyroid glands belonging to (A) normal rats, (B) propylthiouracil-treated rats (Group PTU) and (C) thyroxine-treated rats, in which the corresponding ‘C-cell regions’ are delimited by black dots. The boxed areas in A1, B1 and C1 are also presented as high power images (A2, B2, C2). A noticeable increased number of C cells is observed in hypothyroid rats (Group PTU) in comparison with the other experimental animals. Immunostaining for calcitonin. Bars: A1, B1, C1 = 250 µm; A2, B2, C2 = 50 µm.

Table 2.

Variation of the volume fraction (Vv, in percentages) of the different histological components in the ‘C-cell region’ with treatment

| Groups of animals | Time of treatment | Follicular cells | C cells | Colloid | Interstitium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2 weeks | 33.14 ± 2.74 | 9.62 ± 3.98 | 18.22 ± 4.96 | 38.35 ± 4.86 |

| 5 weeks | 39.95 ± 2.89 | 10.09 ± 2.80 | 14.94 ± 3.67 | 35.02 ± 4.88 | |

| PTU | 2 weeks | 49.64 ± 5.20*** | 4.35 ± 1.23** | 4.83 ± 1.79*** | 40.09 ± 4.77** |

| 5 weeks | 51.96 ± 4.81*** | 4.78 ± 1.44*** | 6.11 ± 2.31*** | 37.16 ± 6.14** | |

| Thyroxine | 2 weeks | 29.40 ± 4.17*** | 6.85 ± 3.20*** | 48.25 ± 6.03*** | 15.21 ± 4.66*** |

| 5 weeks | 22.81 ± 2.79*** | 5.63 ± 1.93*** | 59.18 ± 4.04*** | 12.75 ± 4.11*** |

Means ± SD;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001 vs. control animals.

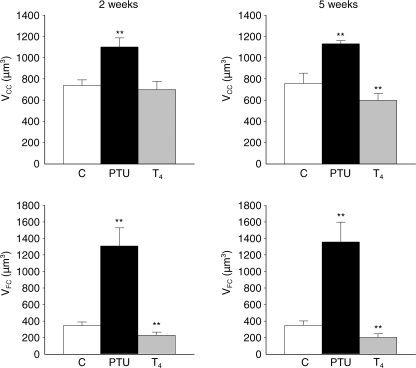

In accordance with previous changes, the average size of follicular cells (in µm3) exhibited a fourfold increase in PTU-treated rats, compared to controls (1307.03 ± 258.40 vs. 342.78 ± 55.80, after 2 weeks’ treatment), and decreased significantly (227.93 ± 37.30, after 2 weeks’ treatment) when thyroid activity was reduced by thyroxine administration (Fig. 2). Although these findings were expected, it was very interesting to observe how the C-cell population responded to the same treatments, i.e. these cells also showed hypertrophic changes in hypothyroid rats (1100.04 ± 4.08 vs. 737.20 ± 53.32 µm3 in control rats, after 2 weeks’ treatment), and the opposite in T4-treated rats (597.58 ± 77.63 vs. 755.46 ± 98.34 µm3 in control rats, after 5 weeks’ treatment) (Fig. 2). In summary, the administration of a goitrogen to the rats provoked a manifest hypertrophia in both kinds of endocrine cells, simultaneously.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the average volumes of C cells (VCC) and follicular cells (VFC) (µm3 ± SD), in control rats (C), propylthiouracil-treated rats (PTU) and thyroxine-treated rats (T4), after 2 and 5 weeks of treatment. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. control rats.

Quantitative changes of C cells

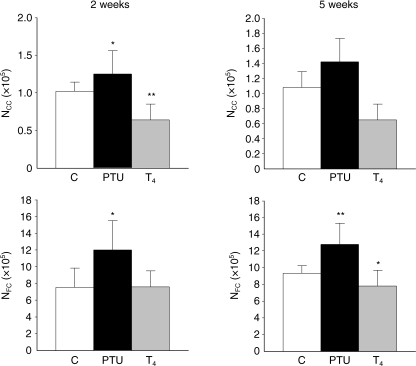

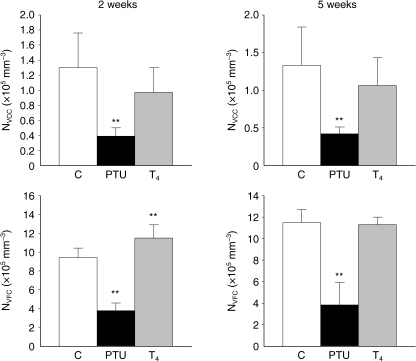

To assess the quantitative changes of C cells in relation to the functional status of the thyroid gland, two approaches were undertaken: firstly, we calculated the total number of C cells per thyroid lobe in every animal (NCC) and, second, we estimated their numerical density (NVCC). As can be seen in Fig. 3, there was an increase in the population of C cells in PTU-treated rats, which was significant after 5 weeks of treatment (1.42 × 105 ± 0.28 × 105 vs. 1.08 × 105 ± 0.48 × 105 C cells in control rats). The opposite, again, occurred on the suppressed thyroid glands because a decrease was observed that was significant after 5 weeks of thyroxine administration (0.65 × 105 ± 0.24 × 105C cells). However, the obvious C-cell hyperplasia in hypothyroid rats turned into a theoretical declining population when the NVCC was calculated (Fig. 4). These apparently contradictory findings could be understandable considering that the background over which C cells evolve – mainly follicles and connective tissue with vessels – was expanded three to four times under TSH influence.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the average numbers of C cells (NCC) and follicular cells (NFC) (× 105) in control rats (C), propylthiouracil-treated rats (PTU) and thyroxine-treated rats (T4), after 2 and 5 weeks of treatment. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. control rats.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the numerical densities of C cells (NVCC) and follicular cells (NVFC) (×105 mm−3) in control rats (C), propylthiouracil-treated rats (PTU) and thyroxine-treated rats (T4), after 2 and 5 weeks of treatment. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001 vs. control rats.

In relation to the behaviour of follicular cells depending on thyroidal status, significant hyperplastic changes were detected in hypothyroid rats, as was expected: the average number of follicular cells in the ‘C-cell region’ (NFC) varied from 9.32 × 105in control rats to 1.79 × 105after 5 weeks’ treatment (Fig. 3). Nevertheless, this turned again into a significant declining tendency when the number of follicular cells per mm3 (NVFC) was calculated (Fig. 4). In thyroxine-treated rats, a significant decrease in both NFC and NVCF was found. Therefore, we decided to estimate the numerical relation between the two endocrine cell populations, which turned out to be around 10 ± 2.5 follicular cells per each C cell, independent of the functional activity of the thyroid gland.

In general, most of the parameters considered in the present study followed a similar tendency when the same treatment was administered to rats, independent of time (after 2 or 5 weeks), with the exception of serum calcitonin levels, as previously mentioned.

Discussion

In the present work, we have induced two different models of follicular-cell activity with the aim of observing the parallel state of C-cell population. We have verified in hypothyroid rats that not only follicular cells but also C cells displayed hyperplastic and hypertrophic changes as well as increased serum calcitonin levels. The opposite was observed when exogenous T4 was administered to rats, because a decrease in the number and size of C cells was found, besides diminished serum calcitonin levels. However, the data described in the literature about similar situations in rats are very confusing and, in some cases, even contradictory (Peng et al. 1975; Bugnon et al. 1978; Stoll et al. 1978; Logonder-Mlinsek et al. 1985; Kalisnik et al. 1988). In our opinion those discrepancies could possibly be explained by the particular distribution of C cells in the thyroid gland, besides differences in the quantitative methods used by different investigators to evaluate this endocrine population.

Because C cells are concentrated in the central region of the thyroid lobe, the ‘C-cell region’ as termed by (McMillan et al. 1985), which is also the place where the most-active follicles of the gland predominate (Kalisnik et al. 1988), we circumscribed our morphometric analysis to this particular ‘C-cell region’ to avoid a larger dispersion of data when the goitrogen was applied. Although the changes in C-cell frequency with treatment were evident considering their absolute numbers (NCC), these quantitative data apparently reversed when either volume fraction (VVCC) or numerical density (NVCC) was estimated. This could be understood when taking into account the expansive growth of the thyroid gland under TSH influence. Consequently, in these circumstances, NVCC assessment proved not to be the most accurate way of comparing the population of follicular cells to C cells. Therefore, we decided to clarify the direct relationship between the two endocrine cell populations by establishing the numerical ratio between them, independent of their size and the rest of the thyroid components. For that purpose, we also estimated the average number of follicular cells in the ‘C-cell region’ and their NVFC. It was meaningful to observe that although a follicular-cell hyperplasia was evident in PTU-treated rats, this turned into a significant declining tendency when the number of follicular cells per mm3was calculated, as a result of their marked hypertrophia under TSH stimulus. Nevertheless, it was very surprising to verify that the numerical relation between follicular cells and C cells was practically maintained, independent of the thyroid status. The present data suggest that Nv estimation is not the best method to evaluate the behaviour of cellular populations under different stimuli, specifically when modifications in the cellular size are also involved.

The validity of the stereological methods applied by us to estimate the volume of the thyroid gland, and the absolute numbers of endocrine cells, are supported by the similarity of the present results to those reported by other authors in normal rats (Conde et al. 1991, Conde et al. 1995; Feinstein et al. 1996). Specifically, Feinstein et al. used the optical fractionator sampling scheme to study C cells in thyroid glands of 3-month-old rats, although fixed in Bouin's solution. They estimated an average lobe volume of 5.15 mm3 (vs. 2.9 ± 0.89 mm3), and a mean of 92 000 C cells per lobe (vs. 108 000), specifying that neither parameter differed significantly between the individual lobes of the same rat. In regard to follicular cells, Malendowicz & Benarek (1986) calculated their size and absolute number in rat thyroid glands at the same age but fixed in Bouin's solution. As a consequence of the fixation method, the average volume of follicular cells were slightly increased in comparison with our data, obtained from formalin-fixed samples, as also occurred with the previous size of the thyroid lobes.

In regard to the possible mechanisms involved in the process, and considering that TSH serum levels are increased in hypothyroid rats and decreased in T4-treated rats, we propose three possible explanations which do not exclude each other, partially related with thyrotropin functions: 1) TSH directly regulates C cells; 2) follicular cells somehow regulate the C-cell activity; and, 3) C cells regulate follicular cells.

The first hypothesis is sustained by different reports describing the appearance of a reactive C-cell hyperplasia (O'Toole et al. 1985; Kalisnik et al. 1988; Nayyar et al. 1989), or a hypercalcitonism (Clark et al. 1978) when TSH-levels were increased in rats. Nevertheless, the first evidence for TSH exerting a direct effect on parafollicular cells was provided by Nuñez & Gershon (1983), who demonstrated serotonin secretion under thyrotropin stimulus. However, the most direct evidence to establish TSH as a regulator of C cells would be to confirm the expression of TSH-receptor in C cells. To our knowledge, the presence of a TSH-receptor transcript has only been demonstrated in certain medullary thyroid carcinomas (Ros et al. 1999; Elisei et al. 1994). If we accept the hypothesis that C cells may be regulated by TSH, it is conceivable that the numerical variations that appeared in the calcitonin-producing cells in various functional or pathological thyroid situations may depend, at least partly, on the inherent changes of the TSH levels. Specifically, in the case of hypothyroidism, such as the one induced by a goitrogen in rats, or spontaneously presented in humans (for example in Hashimoto's thyroiditis), the higher level of TSH should induce a parallel C-cell hyperplasia (Dhillon et al. 1982). In contrast, under chronic suppression of serum TSH provoked by exogenous thyroxine administration, a decrease in C-cell population should be expected. Finally, in hyperthyroidism, we could also expect both a C-cell hyperplasia and a hypercalcitonism, as described by Scheuba et al. (2000).

In regard to the second hypothesis, the regulation of C cells by follicular cells could be carried out by either a local elevation of T3 and T4, or through the release of regulatory substances. For example, growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factor (IGFs) or fibroblast growth factor (FGF), and other products, such as thyroglobulin, play a decisive role in the autocrine regulation of TSH-stimulated follicular cell growth, and differentiation and synthesis of thyroid hormones (Ahrén 1991; Sawicki 1995; Ros et al. 1999; Eggo et al. 2003). According to this hypothesis, those substances could also exert a possible paracrine influence on C cells if they have appropriate membrane receptors. As far as we know, no data on this aspect of intrathyroidal regulation have been published.

In relation to the third hypothesis, C cells are probably involved in the intrathyroidal regulation of follicular cells by the secretion of different regulatory peptides such as CGRP (Zabel et al. 1987), katacalcin (Kendall et al. 1986), somatostatin (Van Noorden et al. 1977), GRP (Sunday et al. 1988), helodermin (Grunditz et al. 1989), neuromedin U (Domin et al. 1990), TRH (Gnokos et al. 1989), ghrelin (Ragha et al. 2006), as well as calcitonin. Most likely some of these peptides affect the nearby follicular cells through specific receptors. To date, the presence of specific receptors only for somatostatin (Ain et al. 1997), serotonin (Tamir et al. 1992) and TRH has been demonstrated in follicular cells (De Miguel et al. 2005).

In general, the present results constitute new evidence of the functional interplay between follicular cells and C cells. This new approach could justify the long phylogenetic and embryonic route taken by mammalian C cells to reach their definitive location in the thyroid gland, in the centre of each thyroid lobe and in close proximity to the follicular cells. Summing up, we can conclude that C cells are not exclusively involved in calcium regulation independent of follicular-cell activity; on the contrary, these cells interact with the surrounding follicular cells, enabling more effective coordinated functions between the two endocrine populations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (ref. BFI2003-0606) and the Consejería de Innovación, Ciencia y Empresa, Junta de Andalucía (CTS-439/2007, P06-CTS-01604), Spain. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Carol L. Wells and to Mr John Brown for correcting the English language.

References

- Ahrén B. Effects of VIP and helodermin on thyroid hormone secretion in the mouse. Neuropeptides. 1989;13:9–64. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(89)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrén B. Regulatory peptides in the thyroid gland: A review on their localization and function. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh.) 1991;124:225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ain KB, Taylor KD, Tofiq S, Venkataraman G. Somatostatin receptor subtype expression in human thyroid and thyroid carcinoma cell lines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1857–1862. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugnon C, Fellman D, Blasher S, Maurat JP, Bloch B. Etude cyto-immunologique des cellules C avec les antiserums anti-calcitonine ou anti-somatostatine chez des rats traités par la vitamine D, la thyroxine ou le benzyl-thiouracile. C R Soc Biol. 1978;4:691–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark OH, Rehfeld SJ, Castner B, Stroop J, Loken HF, Deftos LJ. Iodine deficiency produces hypercalcemia and hypercalcitonemia in rats. Surgery. 1978;83:626–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde E, Martín-Lacave I, Utrilla JC, González-Cámpora R, Galera H. Histometry of normal thyroid glands in neonatal and adult rats. Am J Anat. 1991;191:384–390. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001910405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde E, Martín-Lacave I, Utrilla JC, González-Cámpora R, Galera H. Postnatal variations in the number and size of C-cells in the rat thyroid gland. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;280:659–663. doi: 10.1007/BF00318368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadan J, Sawicki B, Chyczewski L, et al. Preliminary immunohistochemical investigations of human thyroid C cells in the simple and hyperactive nodular goitre. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2001;39:189–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel M, Fernández-Santos JM, Utrilla JC, et al. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone receptor expression in thyroid follicular cells: a new paracrine role of C-cells? Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:713–718. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon AP, Rode J, Leathem A, Papadaki L. Somatostatin: a paracrine contribution to hypothyroidism in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. J Clin Pathol. 1982;35:764–770. doi: 10.1136/jcp.35.7.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domin J, Al-Madani AM, Desperbasques M, Bishop AE, Polak JM, Bloom SR. Neuromedin U-like immunoreactivity in the thyroid gland of the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;260:131–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00297498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggo MC, Quiney VM, Campbell S. Local factors regulating growth and function of human thyroid cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;213:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elisei R, Pinchera A, Romei C, et al. Expression of thyrotropin receptor (TSH-R), thyroglobulin, thyroperoxidase, and calcitonin messenger ribonucleic acids in thyroid carcinomas: evidence of TSH-R gene transcript in medullary histotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:867–871. doi: 10.1210/jcem.78.4.8157713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein RE, Westergren E, Bucht E, Sjöberg HE, Grimelius L. Estimation of the C-cell numbers in rat thyroid glands using the optical fractionator. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996;44:997–1003. doi: 10.1177/44.9.8773565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnokos PJ, Tavianini MA, Liu CC, Roos BA. Thyrotropin-releasing hormone gene expression in normal thyroid parafollicular cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;3:2101–2109. doi: 10.1210/mend-3-12-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunditz T, Persson P, Hakanson R, et al. Helodermin-like peptides in thyroid C cells: Stimulation of thyroid hormone secretion and suppression of calcium incorporation into bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:1357–1361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisnik M, Vraspir-Porenta O, Kham-Lindtner T, et al. The interdependence of the follicular, parafollicular and mast cells in the mammalian thyroid gland: a review and a synthesis. Am J Anat. 1988;183:148–157. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001830205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall CH, Homer CE, Bishop AE, Polak JM. Age-related peptide production by human thyroid C cells. An immunohistochemical study. Virchows Arch A. 1986;410:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00713511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logonder-Mlinsek M, Kalisnik M, Zwitter M, Susec-Michieli M. Long-term effect of ionizing irradiation on rat parafollicular cells at various activation levels of thyroid follicular cells. Acta Stereol. 1985;4:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Malendowicz LK, Benarek J. Sex dimorphism in the thyroid gland. V. Cytologic aspests of sex dimorphism in the rat thyroid gland. Acta Anat. 1986;127:115–118. doi: 10.1159/000146273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Lacave I, Conde E, Montero C, Galera H. Quantitative changes and distribution of the C-cell population in the rat thyroid with age. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;270:73–77. doi: 10.1007/BF00381881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Lacave I, Bernabé R, Sampedro C, et al. Correlation between gender and spontaneous C-cell tumors in the thyroid gland of the Wistar rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1999;297:451–457. doi: 10.1007/s004410051371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Lacave I, Rojas F, Bernabé R, et al. Comparative immunocytochemical study of normal, hyperplastic and neoplastic C-cells of the rat thyroid gland. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;309:361–68. doi: 10.1007/s00441-002-0599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan PJ, Heidbüchel U, Vollrath L. Number and size of rat thyroid C cells: no effect of pienalectomy. Anat Rec. 1985;212:167–171. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092120210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayyar RP, Oslapas R, Paloyan E. Age related correlation between serum TSH and thyroid C cell hyperplasia in Long-Evans rats. J Exp Pathol. 1989;4:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez EA, Gershon MD. Thyrotropin-induced thyroidal release of 5-hydroxytryptamine and accompanying ultrastructural changes in parafollicular cells. Endocrinology. 1983;113:309–317. doi: 10.1210/endo-113-1-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole K, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Pushparaj N. Endocrine changes associated with the human aging process: III. Effect of age on the number of calcitonin immunoreactive cells in the thyroid gland. Human Pathol. 1985;16:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng TC, Cooper CW, Petrusz P, Volpert E. Identification of C-cells in normal and goitrous rat thyroid tissues using antiserum to rat thyrocalcitonin and the immunoperoxidase bridge technique. Endocrinology. 1975;97:1537–1544. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-6-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragha K, García-Caballero T, Nogueiras R, et al. Ghrelin localization in rat and human thyroid and parathyroid glands and tumours. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;125:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros P, Rossi DL, Acebrón A, Santisteban P. Thyroid-specific gene expression in the multi-step process of thyroid carcinogenesis. Biochemie. 1999;81:389–396. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki B. Evaluation of the role of mammalian thyroid parafollicular cells. Acta Histochem. 1995;97:389–399. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(11)80064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuba C, Kaserer K, Kotzmann H, Bieglmayer C, Niederle B, Vierhapper H. Prevalence of C-cell hyperplasia in patients with normal basal and pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin. Thyroid. 2000;10:413–416. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scopsi L. Non-calcitonin genes derived neurohormonal polypeptides in normal and pathologic thyroid C cells. Prog Surg Pathol. 1990;11:185–229. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll R, Faucounau N, Maraud R. Les adenomes à cellules folliculaires et para folliculaires de la thyroïde du rat soumis au thiamazole. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 1978;39:179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunday ME, Wolfe HJ, Roos BA, Chin WW, Spindel ER. Gastrin-releasing peptide gene expression in developing, hyperplastic, and neoplastic human thyroid C-cells. Endocrinology. 1988;122:1551–1558. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamir H, Hsiung SC, Yu PY, Adlersberg M, Nunez EA, Gershon MD. Serotonergic signalling between thyroid cells: protein kinase C and 5-HT2 receptors in the secretion and action of serotonin. Synapse. 1992;12:155–168. doi: 10.1002/syn.890120209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usenko V, Lepekhin EA, Lyzogubov V, et al. The influence of maternal hypothyroidism and radioactive iodine on rat embryonal development: Thyroid C-cells. Anat Rec. 1999;256:7–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990901)256:1<7::AID-AR2>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Noorden S, Polak JM, Pearse AGE. Single cellular origin of somatostatin and calcitonin in the rat thyroid gland. Histochemistry. 1977;53:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00511079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel ER. Stereological Methods. vol 1 London: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M, Surdyk J, Biela-Jacek I. Immunocytochemical studies on thyroid parafollicular cells in postnatal development of the rat. Acta Anat. 1987;130:251–256. doi: 10.1159/000146492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zbucki RL, Winncka MM, Sawicki B, Szynaka B, Andrzejewska A, Puchalski Z. Alterations of parafollicular (C) cells activity in the experimental model of hypothyroidism in rats. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2007;45:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerek-Melden G, Lewinski A, Kunert-Radek J. Intrathyroidal injection of somatostatin suppresses the proliferogenic effect of thyrotropin on thyroid follicular cells in rats. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 1989;1:33–38. [Google Scholar]