Abstract

To identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) antigens as candidates for a subunit vaccine against tuberculosis (TB), we have employed a CD4+ T-cell expression screening method. Mtb-specific CD4+ T-cell lines from nine healthy PPD positive donors were stimulated with different antigenic substrates including autologous dendritic cells (DC) infected with Mtb, culture filtrate proteins (CFP), and purified protein derivative of Mtb (PPD). These lines were used to screen a genomic Mtb library expressed in Escherichia coli and processed and presented by autologous DC. This screening led to the recovery of numerous T-cell antigens, including both novel and previously described antigens. One of these novel antigens, referred to as Mtb9.8 (Rv0287), was recognized by multiple T-cell lines, stimulated with either Mtb-infected DC or CFP. Using the mouse and guinea pig models of TB, high levels of IFN-γ were produced, and solid protection from Mtb challenge was observed following immunization with Mtb9.8 formulated in either AS02A or AS01B Adjuvant Systems. These results demonstrate that T-cell screening of the Mtb genome can be used to identify CD4+ T-cell antigens that are candidates for vaccine development.

Keywords: T Lymphocytes, Vaccination, Adjuvants

1. Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), an intracellular pathogen that invades antigen presenting cells (APC) such as macrophages in infected individuals, remains a serious health problem today, with approximately 2 billion infected individuals worldwide (http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2006/tb_factsheet_2006_1_en.pdf). Tuberculosis (TB) remains the second leading cause of death among all infectious diseases and is responsible for approximately 1.7 million deaths annually[1]. This high mortality occurs despite the use of the live attenuated Mycobacterium bovis, bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG), a live attenuated vaccine widely used outside of the United States. The lack of lifelong protection and variable efficacy afforded by BCG vaccination[2] has been the primary catalyst for the discovery of immunodominant antigens from Mtb that could be used in the development of a subunit vaccine.

There is a body of evidence that the protective immunological response to Mtb infection is derived from the cellular arm of the immune system, specifically involving the generation of antigen-specific CD4+ T-cells[3-6]. A critical role of IFN-γ in the control of mycobacterial infections has also been demonstrated in both mice[7, 8] and humans[9, 10]. The identification of the Mtb antigens that elicit CD4+ T-cell responses during infection has been attempted by a number of different methods, including biochemical fractionation of Mtb protein mixtures. Examples of the successful application of this approach include the identification of ESAT-6/Rv3875[11] and Mtb8.4/Rv1174[12] from Mtb culture filtrate protein (CFP). Although this method has been exploited by researchers, it is labor intensive with much effort expended to identify and characterize a single antigen.

Recently, we have reported a method of screening for Mtb antigens with CD4+ T-cell lines generated from healthy PPD (Mantoux skin test)-positive healthy individuals, stimulated with autologous DC infected with Mtb[13]. This approach represented a modification of an expression cloning strategy used to identify a Listeria monocytogenes CD4+ T-cell antigen[14]. The screening was performed using pools of clones from a Mtb library expressed in E. coli, which were fed to DC, incubated with the relevant autologous CD4+ T-cell line, and proliferation and IFN-γ production measured. The identification of a reactive pool led to the subsequent breakdown to identify the reactive Mtb gene fragment. Utilizing this system, we were able to identify a family of highly related genes, the Mtb9.9 family, that encode potent T-cell antigens[13].

In the current study, we report the results of a greatly expanded human CD4+ T-cell expression cloning effort. We used lines from multiple donors amplified using a variety of stimulating antigens, including DC infected with Mtb, CFP, and PPD. With this method, we have recovered numerous Mtb T-cell antigens and believe this methodology provides an effective screening of entire microbial genomes for CD4+ T-cell antigens. We also demonstrate the protective efficacy of one newly identified antigen, Mtb9.8 (Rv0287) when formulated with either AS01B or AS02A Adjuvant System. These findings demonstrate the role of T-cell subsets in in vivo protection against intracellular infections. We also present data suggesting that in the absence of reliable immune correlates of human protective responses, the Mtb9.8/Rv0287 antigen, selected for evaluation as a vaccine candidate on the basis of in vitro immuno-recognition by cells of healthy human subjects and the mouse model during early stages of Mtb infection (antigenicity), and on the basis of it’s ability to induce immune responses following experimental immunization in animal models (immunogenicity), elicited protection against M. tuberculosis challenge in both mouse and guinea pig models of TB.

2. Materials and Methods

Generation of Mtb-specific T-cell lines from PPD+ donors

PBMCs were purified from heparinized blood and apheresis product obtained from healthy individuals who were screened for participation in this study, evaluated for their tuberculin skin test reactivity and divided into PPD- and PPD+ healthy subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects and the study was approved by Western IRB, Seattle, WA. HLA typing was performed at the Puget Sound Blood Center. Donor 160 is a health care worker who became PPD skin test positive following exposure to a patient with tuberculosis and is HLA-DR13, 15 and HLA-DQ1, 7. Other donors used in this study were HLA typed as follows. Donor 7: HLA-DR13, 15, HLA-DQ1; Donor 103: HLA-DR4, 15, HLA-DQ1, 3; Donor 184: HLA-DR4, 7, HLA-DQ2, 4 and Donor 201: HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2. Dendritic cells (DC) were generated by culture of autologous adherent PBMC with GM-CSF and IL-4 for 7 days, as described[15]. DC were infected with Mtb by overnight culture at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10, as described[16]. Mtb infected DC were cultured at 104 cells/well in 96-well round bottom plates with varying numbers of monocyte depleted PBMC as responder cells (102-104). Wells that showed obvious growth of T-cells were then expanded with CD3 antibody and tested for reactivity with CFP from Mtb (kindly provided by Dr. John Belisle, Colorado State University, produced through the NIAID-NIH Tuberculosis Research Materials contract N01-AI-25147) using autologous PBMC as APC.

Construction and Screening of a Mtb Expression Library

Mtb Erdman genomic DNA was isolated and sheared by sonication to a size range of 1-4 kb. Mtb H37Rv genomic DNA was partially digested with Sau3A and size fractionated. Libraries were constructed in Lambda ZapII (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), as described[17]. Both phage libraries were excised following the manufacturer’s protocol, using approximately 106 recombinant phage. Transfected bacteria were plated to give ~50-80 transfectants per plate and colonies were pooled to establish glycerol stocks. Approximately 800 pools were created for expression screening. Generally, 400-800 pools were screened for each T-cell line. The glycerol stocks were used to establish overnight cultures (2XYT/100 μg/ml ampicillin) that were split 1:5 or 1:10 the next morning. Plates of bacteria were grown, induced and then cultured in antibiotic free medium as described[13]. IFN-γ levels in culture supernatants were determined by ELISA, as described[16]. Pools that demonstrated an increase in IFN-γ were broken down to recover the reactive clone. This was accomplished by picking 96 individual colonies from a positive pool, growing these in a 96-well plate, and repeating the screening of 20 sub-pools derived from the 8 rows and 12 columns. A final repeat of the expression screening of the pure positive Mtb clone was performed. The insert was then characterized by DNA sequencing.

The original pool complexity was selected based on reconstruction experiments utilizing a T-cell clone, 4E4, recognizing the Mtb protein CFP-10/Rv3874[17], also referred to as Mtb11[13] and MTSA-10[18]. In this reconstruction experiment, E. coli expressing rCFP-10 were mixed at different ratios with E. coli expressing vector alone, and were fed to autologous DC and subsequently incubated with the 4E4 T-cell clone. IFN-γ was measured after 48 hours of incubation. The results from this study indicated that detection of reactive pools was possible with a pool complexity as high as 1000. However, because it was assumed that many Mtb clones expressed in E. coli would have lower expression than the rCFP-10 expressing clone used in the reconstruction, a pool complexity of approximately 50-80 was chosen.

Expression of recombinant Mtb9.8

Clone TB472 was used as a template to PCR amplify the region encoding mtb9.8. The 5’ primer was designed to include a NdeI site, which also contained the starting ATG, followed by residues encoding an N-terminal six histidine tag. The 3’ primer included a HindIII site following the residues encoding the termination codon. Amplified product was digested with NdeI and HindIII and ligated into pET17b. This clone was referred to as pETMtb9.8 and the recombinant protein encoded as Mtb9.8.

Expression and purification of Mtb9.8 was performed essentially as described for other Mtb proteins[19]. Briefly, induced E. coli BL-21 (pLysE) pellets were lysed and the recombinant protein recovered in the inclusion body. Purification was via affinity chromatography on a Ni++ NTA-agarose column. Purity of the recombinant protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie blue staining, and N-terminal sequencing using traditional Edman chemistry with a Procise 494 protein sequencer (Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosystems Inc, Foster City CA). Endotoxin was determined to be less than 100 EU/mg of protein by the LAL assay (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD).

All DNA manipulations of the various clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing to eliminate the possibility of the introduction of mutations by restriction, ligation and PCR.

Mtb9.8 Peptide Synthesis

Peptides derived from the predicted amino acid sequences from the mtb9.8 gene were synthesized on a Rainin/PTI Symphony peptide synthesizer using FMOC batch chemistry with HBTU activation. Peptides were analyzed by reverse phase HPLC using a Vydac C18 column. Peptide molecular weights were verified using a Maldi TOF mass spectrometer.

Molecular Analysis of Mtb clones

DNA was prepared following the manufacturer’s protocols (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA; Promega, Madison, WI). DNA sequencing was performed using an Applied Biosystems Automated Sequencer model 373 (Foster City, CA). DNA sequences and deduced amino acid sequences were used in database searches (EMBL and Genbank release 103 and Swiss & PIR & Translated Release 97).

Proliferation and IFN-γ Assays

PBMC from PPD+ and PPD- donors were cultured in complete medium containing recombinant Mtb antigens (10 μg/ml), peptides thereof (1 μg/ml), or controls in 96-well round bottom plates (Corning Costar, Cambridge MA) at 2×105 cells/well in a volume of 200 μl. After 5 days of culture at 37°C in 5% CO2, 50 μl of culture supernatant was removed for determination of IFN-γ levels and the plates were pulsed with tritiated thymidine, as described above.

Protein Immunization in Mouse and Guinea Pig Protection Models

Groups of ten C57BL/6 mice housed at 5 mice/cage were immunized (i.m.) three times with (10 μg) Mtb9.8 mixed with AS02A or AS01B Adjuvant Systems (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium). AS01B contains monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and QS-21 in a liposomal formulation[20], whereas AS02A has the same components formulated in an oil-in-water emulsion[21]. In addition, groups of mice were immunized with BCG once at the first immunization time point or injected with saline or adjuvants alone at the three immunization timepoints. Two weeks after the last immunization, 3 mice per group were chosen randomly from each group and euthanized for immunogenicity studies. Thirty days after the last immunization, the 7 remaining mice from each group were challenged by the aerosol route with approximately 100 CFU of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC#35718). Protection was measured by enumerating the bacteriological burden (CFU) in the mouse lungs and spleen.

Guinea pigs were similarly immunized via the i.m route, three times, three weeks apart, with a 20 μg immunization dose of Mtb9.8 formulated in AS02A in a final volume of 250 μl. The protocol for Mtb9.8 formulation in AS02A (antigen:adjuvant) was identical to those described for the mouse studies but adjusted for a 20 μg immunization dose in a final volume of 250 μl. Animals were immunized with 125 μl of the final formulation per leg. BCG (a single dose of 103 cfu) was used as the positive control and administered via the intradermal route. Negative control groups include adjuvant and saline alone groups. Six weeks after the third immunization, the animals were challenged with the virulent H37Rv strain via the aerosol route by calibrating the nebulizer compartment of the Middlebrook airborne-infection apparatus to deliver approximately 20 to 50 bacteria into each lung. Survival times of infected guinea pigs was determined by observing animals on a daily basis for changes in food consumption, evidence of labored breathing, and behavioral changes. In addition, animals were weighed on a weekly basis until a sustained drop in weight was observed over several days indicating illness. At this point the animal was euthanized and the lung and spleen removed aseptically. The lower cranial lung lobe was used for inspection of pathology, and the right cranial lung lobe and the spleen were cultured for CFU of M. tuberculosis.

Ab ELISA

Animals were bled 2 weeks after the last immunization and serum IgG1 and IgG2c antibody titers were determined. Nunc-Immuno Polysorb plates were coated with 2 μg/ml of recombinant protein in 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer, blocked overnight at 4°C with PBS Tween-20 0.05% BSA 1%, incubated for 2 h at room temperature with sera at 5-fold serial dilutions, washed, and incubated with anti-IgG1-HRP or anti-IgG2c-HRP 1:2000 in PBS Tween-20 0.05% BSA 0.1%. Plates were developed using SureBlue TMB substrate (KPL Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), and read at 450 nm with a reference filter set at 650 nm using a microplate ELISA reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and SoftMax Pro5. Endpoint titers were determined with GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) with a cutoff of 0.1.

ELISPOT

MultiScreen 96-well filtration plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated with 10 μg/ml rat anti-mouse IFN-γ or TNF capture Ab (eBioscience) and incubated overnight at 4°C and then blocked with RPMI 1640 and 10% FBS at room temperature. Splenocytes were plated in duplicate at 2 × 105 cells/well, and stimulated with medium, Con A 3 μg/ml, PPD 10 μg/ml, each recombinant protein 10 μg/ml or overlapping 15 amino acid peptides (10 amino acid overlap) 10, 1 or 0.1 μg/ml for 48 h at 37°C. The plates were incubated with a biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ or TNF secondary Ab (eBioscience) at 5 μg/ml and the filters were developed using the Vectastain ABC avidin peroxidase conjugate and Vectastain AEC substrate kits (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Spots were counted on an automated ELISPOT reader (C.T.L. Serie3A Analyzer, Cellular Technology Ltd, Cleveland, OH), and analyzed with Immunospot® (CTL Analyzer LLC).

Statistical method

The difference in bacterial numbers between control mice and vaccinated mice were compared by a one-way Anova of the log10 CFU. Differences between means were assessed for statistical significance by Tukey’s test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical differences in guinea pig survival times were calculated using the Log Rank Test.

3. Results

Generation of T-cell lines

The T-cell lines were derived from a panel of PBMC from donors that had not been previously BCG immunized, had a history of occupational exposure to Mtb or contact with patients with active TB, were PPD+,but had no evidence of disease by chest X-ray (Table 1). Because we hypothesized that these donors developed protective immunity upon exposure to Mtb, it was presumed that the Mtb antigens recognized by their CD4+ T-cells would include antigens that were involved in the protective outcome.

Table 1. Summary of Donor HLA Typing and Stimulation of T Cell Lines.

T cell lines were derived from HLA-typed PBMC obtained from the apheresis product of nine healthy PPD+ donors who had no evidence of disease. Dendritic cells generated from autologous adherent PBMC were stimulated with CFP or PPD or were infected with Mtb and used to stimulate T cells.

| Donor ID | Donor HLA Typing | Stimulation |

|---|---|---|

| D7 | HLA-DR13, 15, HLA-DQ1 | Culture filtrate protein |

| D27 | Not performed | Culture filtrate protein |

| D62 | Not performed | Culture filtrate protein |

| D103 | HLA-DR4, 15, HLA-DQ1, 3 | Culture filtrate protein |

| D131 | Not performed | Infected DC |

| D 152 | Not performed | Culture filtrate protein |

| D160 | HLA-DR13, 15, HLA-DQ1, 7 | Infected DC |

| D184 | HLA-DR4, 7, HLA-DQ2, 4 | Culture filtrate protein |

| D184 | HLA-DR4, 7, HLA-DQ2, 4 | Infected DC |

| D201 | HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2 | Culture filtrate protein |

| D201 | HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2 | Infected DC |

| D201 | HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2 | Infected DC |

| D201 | HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2 | PPD |

The choice of the stimulation of the donor T-cells was next considered. In the previous study[13] stimulation of the T-cells was accomplished using autologous dendritic cells infected overnight with Mtb, based on the reasoning that the antigens produced under these conditions might mimic what occurred in the context of an actual infection. In this study, the number of donors was increased and the method of stimulation was broadened, employing two additional sources of antigen stimulation, CFP and PPD. The use of CFP was based on the substantial body of evidence in animal models that this material contains protective Mtb antigens[22-24]. PPD was used since the material clearly contains T-cell antigens based on the ability of this material to elicit DTH responses through skin testing of Mtb infected individuals. In addition to the possibility that T-cell vaccine candidates may be present within this complex mixture, the use of PPD was justified based on the interest in identifying defined antigens that might be used as an alternative skin test reagent to detect Mtb exposure.

Limiting dilution techniques were employed to establish Mtb reactive T-cell lines from a total of nine different donors with a variety of HLA DR and HLA DQ alleles (Table 1). One donor (D201) was used to generate T-cell lines using all three different stimulation methods, as a preliminary experiment to see if the different methods of stimulation resulted in the identification of different reactive Mtb antigens. These thirteen T-cell lines were used in subsequent expression screening.

Identification of Mtb T-cell antigens by expression screening

T-cell expression screening was performed with thirteen different T-cell lines, derived from nine donors (See Materials and Methods for details). Reactive Mtb clones were characterized by DNA sequencing. DNA sequencing often revealed the presence of more than one partial or complete Mtb open reading frame within the insert. To determine which ORF was reactive, the following general strategy was employed. First, the region of the insert containing the reactive ORF was localized by deleting various portions of the insert through the use of restriction sites within the insert. These Mtb clones were then tested in the expression cloning assay to determine if reactivity was retained. Generally, this method implicated a single ORF. Confirmation of the reactive ORF was usually achieved by generating overlapping peptides to the suspected reactive ORF and testing them in the expression cloning assay.

A summary of the expression cloning results is shown in Table 2. Several Mtb clones recovered represented portions of previously described human T-cell antigens, including antigen 85B/Rv1886, 85C/Rv0129, the 19 kDa antigen/Rv3763, and the 14 kDa (α-crystallin) antigen/Rv2031[25-27]. Both antigen 85B and 85C were recovered using T-cell lines from donors stimulated with CFP. Antigen 85B and 85C are major constituents of CFP[28]. The Mtb 14 kDa α-crystallin antigen, previously described to be expressed at high levels in latent Mtb infections, was recovered using T-cell lines stimulated with Mtb infected DC. An additional known gene, MPT83/Rv2873[29], that encodes a cell surface lipoprotein described to be a seroreactive antigen, was recovered using a T-cell line from Donor 152, stimulated with CFP.

Table 2. Summary of M. tuberculosis genes isolated by CD4+ T Cell Expression Cloning.

| Gene | Protein | Donor (Stimulation)1 | Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mtb 85B/Rv1886 | Ag 85B (325 aa) | D152 (CFP) | AAC44294 |

| Mtb 85C/Rv0129 | Ag 85C (340 aa) | D7 (CFP) | CAA40506 |

| Mtb 19kDa/Rv3763 | 19 kDa antigen (159 aa) | D152 (CFP) | X07945 |

| Mtb 14kDa/Rv2031 | 14 kDa (144 aa) | D184 (Infected DC) | M76712 |

| mpt83/Rv2873 | MPT83 (239 aa) | D103 (CFP) | X94597 |

| mtb39a/Rv1196 | 39kDa (391 aa) | D160 (Infected DC) | I364 |

| lhp/Rv3874 | CFP-10 (100 aa) | D160 (Infected DC) D27 (CFP) |

CAA17966 |

| esat6/Rv3875 | ESAT6 | D160 (Infected DC) D27 (CFP) |

X79562 |

| mtb9.9a/Rv1793 | Mtb9.9A (94 aa) | D160 (Infected DC) D201 (CFP) |

CAA17714 |

| mtb9.9b/Rv1793 | Mtb9.9B (94 aa) | D184 | CAB07821 |

| mtb9.9c/Rv1793 | Mtb9.9C (94 aa) | D160 | CAB06842 |

| pef-1 | Rv1788 (99 aa) | D184 (CFP) | CAA17710 |

| pef-2 | Rv1791 (99 aa) | D184 (CFP) | A70930 |

| *htcc-1/Rv3616 | HTCC-1 (392 aa) | D184 (CFP) D184 (Infected DC) D201 (PPD) |

A70957 |

| *mtb17 | Rv1919c (154 aa) | D7 (CFP) | F70808 |

| *mtb16 | Rv2626c (143 aa) | D7 (CFP) | A70573 |

| * Mtb bfr/Rv3841 | Bacterioferritin (159 aa) | D201 (CFP) | O08465 |

| *mtb9.8/Rv0287 | Mtb9.8 (97 aa) | D184 (CFP) D201 (Infected DC) D7 (CFP) D62 (CFP) |

CAA17362 |

T cell lines were stimulated with dendritic cells infected with M. tuberculosis or were stimulated with M. tuberculosis culture filtrate protein (CFP) or purified protein derivative (PPD).

denotes genes that were newly identified by the reported screening methodology.

Two genes, mtb39A and lhp (also referred to as mtb11), that we had previously recovered using expression cloning with TB patient sera and demonstrated to encode proteins that were potent T-cell antigens[17, 30] were re-isolated during the T-cell expression cloning. The Mtb39/Rv1196 protein has not been detected at significant levels in CFP, and was isolated here using a T-cell line stimulated with infected DC. Indeed, T-cells generated against CFP do not react with Mtb39. CFP-10/Rv3874, the encoded protein of lhp, is known to be present in CFP and was recovered using a T-cell line stimulated with CFP, as well as with a T-cell line stimulated with infected DC. Interestingly, the same T-cell lines that recognized CFP-10 also recognized ESAT-6/Rv3875, a known T-cell antigen encoded by the esat-6 gene located adjacent to the lhp gene, and in the same orientation. It is not clear which protein was expressed in the T-cell expression assay since in both cases the TB clones recovered contained at least a portion of each gene, and subsequent confirmation with rCFP-10 and rESAT6 confirmed reactivity of the T-cell line to both proteins.

Three members of the mtb9.9 gene family, described previously in the initial report on T-cell expression cloning of Mtb antigens[13], were recovered using T-cells from two different donors, one stimulated with infected DC and one stimulated with CFP. The gene product of one of the family members, Mtb9.9/Rv1793, was previously shown to be present in both the Mtb cellular fraction and CFP.

The T-cell expression cloning also revealed seven additional genes encoding proteins that had not previously been described as T-cell antigens. The genes encoding two of these antigens are highly related members of the PE family, a group of proteins rich in glycine and alanine, with unknown function. The two genes both encoded 99 amino acid proteins that shared 89% identity, and are referred to here as pef-1/Rv1788, and pef-2/Rv1791, based on their inclusion in the PE family. The two genes were recovered from the Mtb Erdman library. The amino acid sequence encoded by one gene was identical to that reported from the MtbH37Rv genome sequencing (Acc.#A70930) while the other protein differed by a single residue (proline at position 2) than the reported sequence (Acc.#F70929). These two genes were isolated using a single T-cell line stimulated with CFP, and based on the high level of homology between the predicted proteins, it was suspected that a single epitope common to the two proteins was recognized by these two cell lines.

An additional gene was identified using two different T-cell lines from one donor stimulated with CFP and Mtb infected DC, and a T-cell line from a second donor stimulated with PPD. This gene, referred to as httc-1/Rv3616, encodes a predicted protein of 392 amino acids (Table 2) and a detailed molecular and immunological characterization of this antigen will be described elsewhere (Skeiky, et.al-Unpublished).

Three additional genes were identified that encoded proteins reactive with a T-cell line stimulated with CFP. Two genes were recovered by screening with a single T-cell line, one encoding a predicted 154 amino acid protein and the other encoding a 143 amino acid protein. These genes were referred to as mtb17/Rv1919 and mtb16/Rv2626, based on the respective molecular weights of the predicted proteins (Table 2). The third gene isolated was Mtb bacterioferritin/Rv3841, which encodes a 159 amino acid protein (Table 2).

The final gene identified through the T-cell expression cloning was unique in that it was recognized by four of the T-cell lines, derived from four different donors. In addition, the method of stimulation included both Mtb infected DC and CFP. The recognition of this antigen by four different donor T-cell lines suggested that it was widely recognized by individuals that had been infected with TB and had protective outcomes. Because of this result, the mtb9.8 gene and Mtb9.8/Rv0287 protein were evaluated in more detail.

The mtb9.8 gene encodes a protein of 97 amino acids, referred to as Mtb9.8 here based on predicted molecular weight. This protein has also been assigned the designation Rv0287 (Table 2). A search of the GenBank database (Release 128.0) revealed only a single additional Mtb gene with significant homology (Acc. #NP_217536), encoding a 97 amino acid protein with 92% identity with Mtb9.8. The mtb9.8 gene has 15% homology to some members of the early secretory antigenic target-6 (ESAT-6) protein family, prominent antigens among those identified early after infection which induce an impressive immune response in in vitro T-cell assays[31]. The gene encoding ESAT-6 is located in the genomic region of difference-1 (RD-1) which is missing from all BCG vaccine strains but is present in all virulent members of M. tuberculosis complex. Interestingly, these small polypeptides have been identified as dominant targets for both CD4+ and CD8+ αβ T-cells[32, 33]. Like CFP-10 and ESAT-6, Mtb9.8/Rv0287 is a member of a large family of mycobacterial proteins, including 22 found in M. tuberculosis, which are encoded by genes arranged in pairs in the genome[34]. Recent work indicates that secretion of the proteins is an active process involving a membrane protein complex formed from the products of several flanking genes[35]. Several other CFP-10/ESAT-6 family members are known to be secreted, including the products of Rv0287/Rv0288 and Rv3019c/Rv3020c[36], which have recently been shown to form tight complexes, as observed for CFP-10 and ESAT-6[37].

The mtb9.8 gene was re-engineered for expression in E. coli, with an N-terminal histidine tag. Purified Mtb9.8 protein was used to generate a high titer rabbit serum. A western blot performed with this serum demonstrated that the Mtb9.8 protein is readily detected in CFP, and is present at low levels in intracellular and membrane fractions (Data not shown).

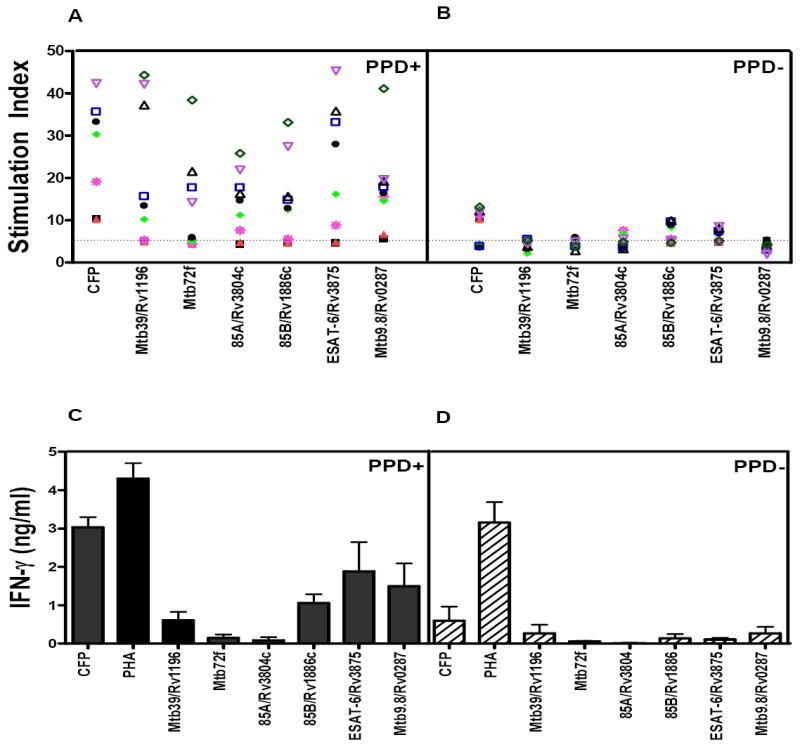

PBMC responses to Mtb9.8 in PPD positive and PPD negative individuals

PBMC from the initial nine PPD positive donors were first evaluated for responses to Mtb9.8. Proliferation and IFN-γ production were measured to Mtb9.8 and CFP (Fig. 1). Positive responders included Donors D7, D62, D201, and D184 from whom CD4+ skewed T-cell lines had been made that were reactive to Mtb9.8 in the expression cloning screens. PBMC from an additional seven PPD positive donors and twelve PPD negative donors were evaluated for proliferative responses (Fig. 1A). Using an arbitrary positive cut-off of a stimulation index of 5, Mtb9.8 elicited positive responses in 69% (11/16) of PPD positive donors, while CFP elicited positive responses in 94% (15/16) of PPD positive donors (Fig. 1A). The specificity of response was found to be high for Mtb9.8, with only 17% (2/12) of PPD negative donors responding, while 75% (9/12) of PPD negative donors responded to CFP (Fig. 1). As a control, IFN-γ production induced by the secreted Ag85 complex, ESAT-6, and Mtb72F was analyzed in the same individuals. While prior studies reported higher levels of IFN-γ from Mtb39-stimulated PBMC isolated from healthy PPD+ individuals[19], human anti-Mtb32 or anti-Mtb72f antigenicity results using PBMC isolated from a similar population have not been previously published. Interestingly, PPD positive donors that responded with low levels of IFN-γ upon stimulation with Mtb9.8, also produced low levels of IFN-γ in response to Ag85B, 85A and ESAT-6 (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Recognition of Mtb9.8 by human PBMC.

Proliferation (A, B) and IFN-γ (C, D) were measured in PBMC from nine PPD positive and negative donors. The PPD+ donor PBMC were used to generate the T cell lines used in the expression cloning. Proliferation was measured in PPD+ (A) and PPD- (B) donor PBMC by tritiated thymidine incorporation and the results reported as an SI (counts per minute of cultures with antigen/counts per minute of medium control cultures). PBMC (2 × 105 cells/well) were cultured in the presence of antigen (10 μg/ml) for 5 days. After 5 days, 50 μl of culture supernatant was carefully aspirated for determination of IFN-γ levels by ELISA, and the plates were pulsed with tritiated thymidine. After culture for a further 18 h, cells were harvested, and tritium uptake was determined by using a gas scintillation counter. IFN-γ was measured by ELISA and are reported as mean ± SEM (C, D).

Epitope Mapping in PBMC from PPD positive Healthy Individuals and M. tuberculosis infected mice

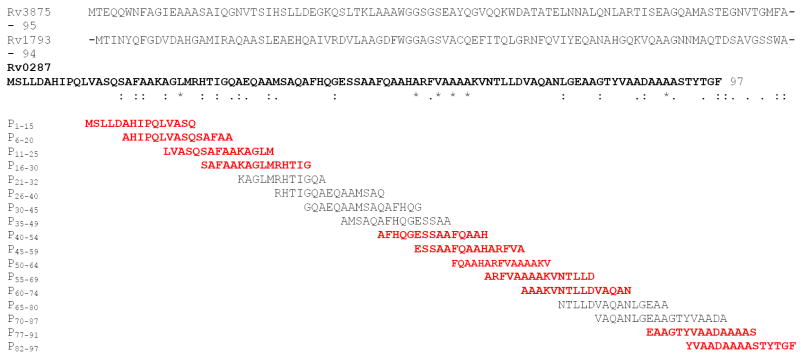

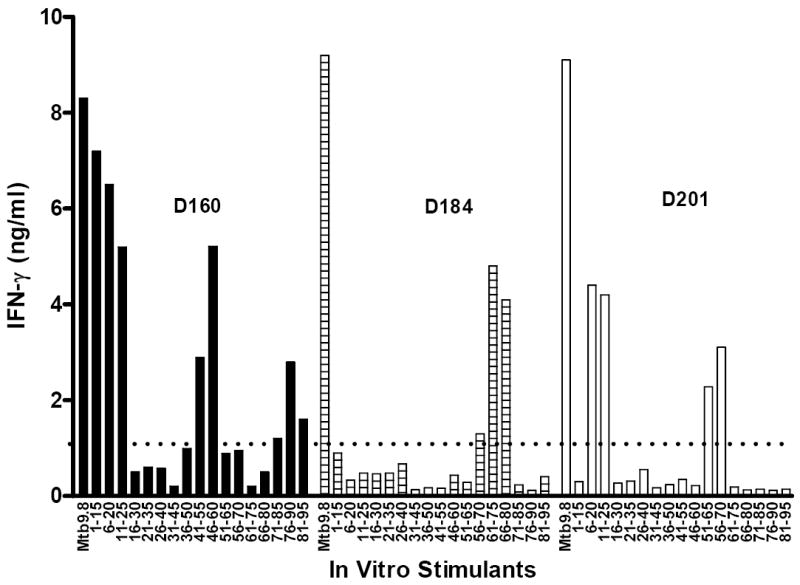

Since mounting evidence from human studies and murine models of TB points toward a role for both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells in controlling M. tuberculosis infection, we set out to identify HLA-class I- and class II-restricted T-cell responses to the Mtb9.8 antigen. PBMC derived from an Mtb9.8 responding HLA-DR3, HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DR13 TB-exposed donors were stimulated with Mtb9.8 antigen and Mtb9.8-derived 15-mer peptides overlapping by 10 amino acids (Fig. 2). After 5 days, the production of IFN-γ was assessed by ELISA (Fig. 3). IFN-γ production was detected in response to stimulation with peptides Mtb9.8 p1-15, p6-20, p11-25, p41-55, p46-60, p51-65, p56-70, p61-75, and p66-80.

Figure 2. Amino acid sequence alignment of Mtb9.8 (Rv0287) and related Mtb family members.

Identical residues are indicated by an asterix (*), and similar residues indicated by periods. Peptides reactive with PBMC from PPD positive healthy donors are in bold.

Figure 3. Response of PPD+ healthy donors to Mtb9.8 and overlapping synthetic peptides.

IFN-γ-production by PBMC purified from three PPD+ healthy donors (D160, D184, and D201) in response to stimulation with recombinant Mtb9.8 (10 μg/ml) and overlapping 15-mer peptides (1 μg/ml) was evaluated. PBMC (2×105 cells/well in a volume of 200 μl) from PPD+ donors were cultured in triplicate wells with complete medium in 96-well round bottom plates. After 5 days of culture at 37°C in 5% CO2, culture supernatants were removed for determination of IFN-γ levels by ELISA. This experiment was repeated twice and the data reported as mean values (ng/ml) of the six replicate wells.

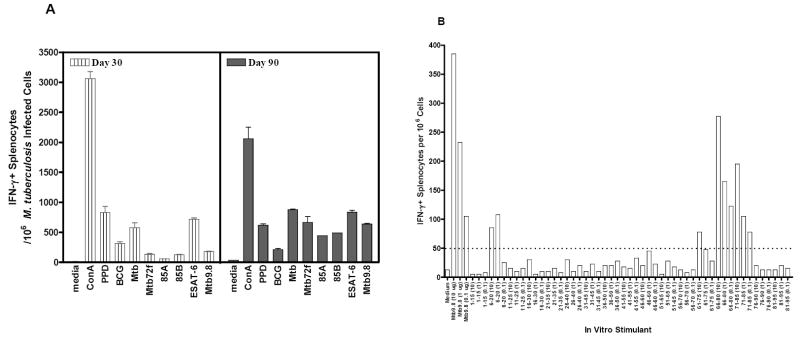

We also evaluated the recognition of Mtb9.8 and epitopes thereof in the mouse model of TB infection (Fig 4 a,b). In three independent experiments, using aerosol infection, mice were infected with M. tuberculosis and the recognition of recombinant Mtb9.8 and peptides spanning the length of Mtb9.8 were evaluated by IFN-γ ELISPOT after in vitro restimulation. The infected mice gave a significant response to the Mtb9.866-80 and Mtb9.871-85 epitopes (Fig. 4B). Thus, in C57BL/6 mice, as in humans, Mtb9.8 is a target of the T-cell response following infection with Mtb.

Figure 4. Antigenicity of Mtb9.8 and Mtb9.8-derived peptides in M. tuberculosis-infected mice.

Splenocytes from M. tuberculosis infected mice were purified 3 weeks and 3 months after infection and responses to Mtb9.8 evaluated (Panel A). Splenocytes from M. tuberculosis-infected mice were also stimulated with Mtb9.8 (10 μg/ml) and overlapping 15-mer peptides (10, 1 and 0.1 μg/ml), and IFN-γ producing splenocytes enumerated (Panel B).

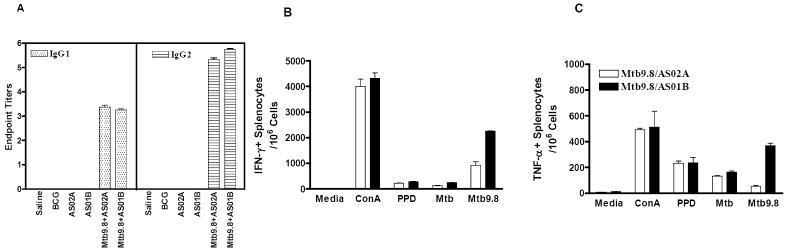

Immunization with Mtb9.8 induces an antigen-specific immune response

Groups of C57BL/6 mice (H-2b) were immunized three times three weeks apart with Mtb9.8 formulated with AS02A or AS01B adjuvants. Two weeks after the last injection, serum was collected for evaluation of anti-Mtb9.8-specific IgG1 and IgG2a responses by ELISA. The results revealed that mice immunized with these vaccines had responses of the IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses, with a slightly higher IgG2a/IgG1 ratio in mice receiving the Mtb9.8/AS01B vaccine. No Mtb9.8-specific antibody responses were detected in mice injected with saline, BCG or adjuvant alone (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Immune responses induced by the Mtb9.8/AS02A and Mtb9.8/AS01B vaccines.

Groups of ten C57BL/6 mice housed at 5mice/cage were immunized (i.m.) three times with 8 μg Mtb9.8 formulated in AS02A or AS01B. Control groups were immunized once with BCG (s.c.) or injected three times with saline or adjuvant alone. Serum samples were collected two weeks after the last injection and analyzed by ELISA for the presence of anti-Mtb9.8 IgG1 and IgG2a. Each bar represents the mean and SE of endpoint titration data from individual mice (Panel A). Two weeks after the last immunization, 3 mice were chosen randomly from each group for immunogenicity assays. Splenocytes were isolated and stimulated in vitro with Mtb9.8, PPD, Mtb lysate (each at 10 μg/ml), Con A (1 μg/ml) or medium alone. The elicitation of IFN-γ (Panel B) and TNF-α (Panel C) were assessed by ELISPOT assays with splenocytes isolated from individual experimental mice from each group. Each bar represents the mean and standard error of duplicate wells. Data shown are the mean of duplicate wells from two different experiments. These experiments were repeated with similar results.

Recall responses induced by Mtb9.8/AS01B or Mtb9.8/AS02A were also investigated by culturing splenocytes 14 days after the last boost with Mtb9.8 as well as other mycobacterial antigens including PPD, Mtb72f, 85A, 85B, and ESAT-6. IFN-γ- and TNF-secreting splenocytes cells were evaluated by ELISPOT (Fig. 5B and C). The results revealed that immunization of C57BL/6 mice with the Mtb9.8 containing vaccines induced high numbers of IFN-γ-producing splenocytes after in vitro stimulation with Mtb9.8 (Fig. 5B). Twice as many Mtb9.8-specific IFN-γ producing splenocytes were induced with the Mtb9.8/AS01B vaccine than the Mtb9.8/AS02A-containing vaccine (Fig.5B). PPD (at a 10 μg/ml dose) also stimulated the splenocyte cultures from Mtb9.8 immunized mice to produce IFN-γ.

Responses to Mtb9.8 protein in mouse and guinea pig protection models

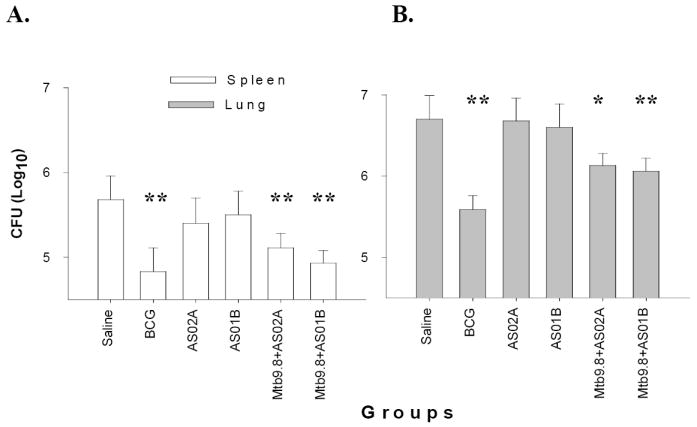

The Mtb9.8 protein was next evaluated in the murine protection model. Groups of C57BL/6 mice were injected three times with Mtb9.8 mixed with AS01B or AS02A Adjuvant System or these adjuvants alone. BCG immunized mice were utilized as a positive control group. Resistance was assessed four weeks after Mtb infection by enumeration of bacteria in both lung and spleen. A reduction of bacterial burden in the Mtb9.8 immunized groups was observed in both the lungs and the spleens compared to the groups receiving saline or adjuvant alone (Fig. 6; (*p < 0.05), **p< 0.001), although reduction in bacterial load was not as robust as that seen with the BCG immunized group.

Figure 6. Mtb9.8 protein protects against aerosol challenge with Mtb.

Groups of ten C57BL/6 mice were immunized (i.m.) three times with 8μg Mtb9.8 formulated in AS02A or AS01B. Control groups were immunized once with BCG (s.c.) or injected three times with saline or adjuvant alone. In addition, a group of five mice were immunized with BCG once. Thirty days after the last immunization, 7 of the 10 mice were challenged by the aerosol route with approximately 100 CFU of M. tuberculosis Erdman. Protection was measured by enumerating the bacteriological burden (CFU) in the mouse spleens (A) and lungs (B). Data shown are mean ± SEM [n= 7 mice];* P<0.05; **P < 0.001.

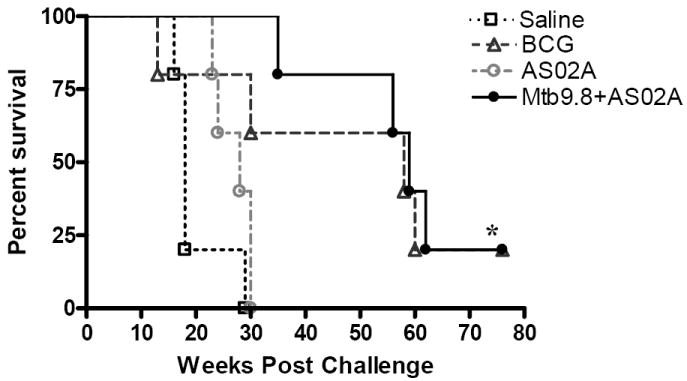

Having demonstrated that in the mouse model immunization with Mtb9.8 formulated in AS02A or AS01B protected against tuberculosis, we next evaluated whether these vaccination approaches would also protect against tuberculosis infection in the guinea pig model. Groups of five guinea pigs were immunized with three doses of 20 μg Mtb9.8 formulated in AS02A. Control groups were immunized with AS02A adjuvant alone or saline via the i.m. route or with a standard dose of 103 cfu BCG administered via the i.d. route. Thirteen weeks after the third immunization, the animals were aerosol challenged with 20-50 cfu of the virulent Mtb strain H37Rv. Protection was monitored by outward signs of infection (difficulty in breathing and weight loss) with survival as an end point. The results from this study revealed that at 30 weeks post challenge (Fig. 7), while all animals in the saline and adjuvant control groups were losing weight, moribund and had to be sacrificed, 4/5 of the guinea pigs immunized with BCG, and 5/5 of those immunized with Mtb9.8/AS02A were still alive. At 35 weeks (~5 weeks after all animals in the control groups succumbed), 4/5 of the animals in the Mtb9.8 vaccinated group were still alive. By 70 weeks (~15 months) post challenge, 20% of animals in the Mtb9.8- and BCG-immunized groups were still alive. Importantly, no significant differences in the levels of protection induced by BCG and the fusion protein vaccine were found (P > 0.05; Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the logrank test).Taken together, the results revealed that in the guinea pig model, Mtb9.8 delivered as a recombinant protein formulated in AS02A, protected guinea pigs against virulent tuberculosis challenge to an extent comparable to that seen with BCG and for periods lasting over one year.

Figure 7.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves [n=5] showing that vaccination of guinea pigs with Mtb9.8 protein formulated in AS02A substantially increased survival after low dose aerosol challenge with M. tuberculosis. A P of < 0.05 was considered significant by the Kaplan-Meier log rank test; *P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

An optimal methodology for the discovery of vaccine candidates for TB must meet several criteria. First, it should enrich for the relevant antigens sufficiently to allow for subsequent validation. Second, it should be comprehensive, so that all vaccine candidate antigens can be recovered. Third, the methodology should be relatively rapid to employ. The method employed herein, consisting of expression screening using T-cells from individuals that had protective responses following exposure to Mtb, potentially meets all these criteria. The utilization of proliferation and IFN-γ production by T-cells from protected individuals should enrich for the relevant antigens, given the known role of CD4+ T-cells in contributing to protection in animal models [3-5] and the role of IFN-γ in protection in mice and humans [7-10]. Indeed, the known genes recovered by this method included two of the Ag85 family members and the mtb39A gene, which encode antigens that have been demonstrated to offer some level of protection in animal models[17, 21, 28, 38-41]. Additionally, this method has the potential of being comprehensive through the use of multiple donors with different HLA restriction, by varying the antigenic substrate used in the T-cell stimulation, and by screening a sufficient number of Mtb pools. Finally, this method is also relatively rapid, allowing the simultaneous recovery and characterization of numerous candidate antigens.

The Mtb libraries utilized in the screening were constructed in the pBluescript SK vector, which encodes the N-terminal 4 kilodalton portion of β-galactosidase. Previous expression screening of these libraries with TB patient sera had demonstrated that the majority of reactive clones recovered encoded partial Mtb proteins fused to the 4 kilodalton portion of β-galactosidase[19, 30]. This led us to presume at the outset of the T-cell expression screening that in the majority of the clones recovered the reactive ORF would be in frame with the 4 kilodalton portion of β-galactosidase. Surprisingly, this expectation proved to be wrong, with the vast majority of the genes encoding reactive proteins residing completely within the Mtb insert. All clones recovered (with one exception) did have the relevant gene encoding the reactive protein in the expected orientation. However, the genes were not generally expressed as fusions with the 4 kilodalton portion of β-galactosidase. Instead, translation occurred in E. coli utilizing the Mtb initiation sites. Although this translation was possibly quite low in many cases, it was sufficient for detection due to the sensitivity of the T-cell assay. One consequence of this was that a strengthening of signal (both proliferation and IFN-γ production) was generally observed as sub-pools of less complexity were re-tested. A second consequence of the internal initiation of Mtb proteins was that it effectively reduced the number of pools that required screening to get complete genome coverage. Although it is possible that some Mtb genes are not able to be translated by the E. coli translational machinery and would require fusion with the 4 kilodalton portion of β-galactosidase to be recovered. It is apparent from this study that many Mtb proteins can be expressed in this manner at sufficient levels to allow detection.

Utilizing the same Mtb pools for all of the different T-cell lines assayed conferred an additional advantage during the screening process; that of generating increased knowledge regarding the composition of the pools as the study continued. When subsequent lines were tested, and previously identified positive pools were found, it was straightforward to confirm that the reactivity was due to the antigen previously identified in that pool, saving the more time-intensive step of performing the breakdown of the pool to obtain clonal isolation.

The T-cell lines utilized had various levels of complexity. Several lines were oligoclonal, recognizing only several epitopes within the Mtb genome. Other lines generated were fairly broad, recognizing more than ten different epitopes. Occasionally, it was found that the broader lines would strongly recognize all of the pools, presumably recognizing an epitope in Mtb that was shared in E. coli. These lines could not be utilized in the screening, and this finding illustrates one limitation of using E. coli as the expression host.

The choice was made to stimulate the T-cell lines with different antigenic materials, since it was presumed that using any single approach would likely bias the antigens recovered. The results reported here support that presumption. Mtb39A, an antigen recognized by the majority of PPD positive donors[20], was only recovered using a T-cell line from a single donor stimulated with infected DC. Previous characterization demonstrated that it is not expressed at significant levels in CFP, and consistent with this, was not recovered by any T-cell lines stimulated with CFP.

Of special interest are the two antigens that were recovered using T-cell lines stimulated with either infected DC or CFP. The use of infected DC as a stimulating source is relevant since it could enrich for antigens that are processed and presented in the course of a human infection. Antigens within CFP also merit additional attention, given the protection data in animal models that has been generated with this complex mixture. For this reason Mtb9.8 and HTCC-1 were chosen for further analysis.

An additional reason for concentrating on Mtb9.8 was that T-cell lines from four different donors were shown to react with the protein. This was a preliminary indication that a substantial percentage of the healthy PPD positive population had generated responses to this antigen during the acquisition of protective immunity. The analysis of PBMC from PPD positive healthy donors confirmed that the antigen was widely recognized in this population, providing further support for the antigen as a vaccine candidate. Antigenicity studies in M. tuberculosis infected mice also confirmed that Mtb9.8, specifically Mtb9.866-80 and Mtb9.871-85 epitopes, are recognized during infection.

It is evident that this strategy is effective in recovering antigens that elicit T-cell responses in individuals that have been infected with M. tuberculosis and generated protective responses. However, the existence of a correlation between the recognition of the antigens and protective outcome does not necessarily indicate a causal relationship. To address if Mtb9.8 may play a role in providing protective immunity, we used the recombinant protein in the aerosol murine model to demonstrate that partial protection can be conferred by monitoring CFU in the mouse. The Mtb9.8 antigen identified by a system primarily geared towards identifying CD4+ T cell antigens and formulated with adjuvant systems known to generate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses[20, 21], induced protection in both mouse and guinea pig models of tuberculosis. Given that protection in the mouse was assessed four weeks after challenge during the acute stage of Mtb infection, rather than during latent stages, we hypothesize that the Mtb9.8-specific CD4+ T cell subset may have played a larger role in protective immunity than the CD8+ subset[42]. The guinea pig model is generally accepted as the most demanding small animal test for TB vaccines. In this study, Mtb9.8 and AS02A gave significant protection as evident by reduced clinical development of disease and increased survival time of vaccinated guinea pigs. Collectively, the method of identification, the wide recognition by the protected human population, and the responses observed in the animal studies support further characterization of Mtb9.8 as a subunit vaccine candidate for TB.

This study provides support for the premise that an entire genome can be scanned for vaccine candidate antigens derived from an infectious agent where the CD4 T-cell response is relevant. Indeed, this approach has recently been adapted for T-cell antigen discovery in Leishmania infections[43] and Chlamydia infections[44]. Although the focus of this approach thus far has been confined to infectious disease antigen discovery, it is reasonable to presume that this approach could be adapted to the discovery of human tumor antigens where tumor specific CD4 T-cell responses have been obtained. The present study also demonstrates that TB subunit vaccines can promote efficient protection that is similar to the level provided by BCG in the mouse and susceptible guinea pig models.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Paul Sleath and Sean Steen for synthesis of synthetic peptides, Drs Mike Lodes and John Webb for M. tuberculosis recombinant libraries, Dr John Belisle for providing CFP (provided through the NIAID-NIH Tuberculosis Research Materials contract N01-AI-25147), and Pamela Ovendale, Nicole Stride, David Molesh, Liqing Zhu, Craig H. Day, and Jeffery Guderian for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported in part by grants UC1 AI067251 and R01 AI044373 and contract N01-AI-25479 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO report 2006. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning, financing. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine PE. BCG: the challenge continues. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33(4):243–5. doi: 10.1080/003655401300077144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller I, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H, Kaufmann SH. Impaired resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection after selective in vivo depletion of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ T cells. Infection and Immunity. 1987;55(9):2037–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2037-2041.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orme IM. The kinetics of emergence and loss of mediator T lymphocytes acquired in response to infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Immunology. 1987;138(1):293–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orme IM, Collins FM. Adoptive protection of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected lung. Dissociation between cells that passively transfer protective immunity and those that transfer delayed-type hypersensitivity to tuberculin. Cell Immunol. 1984;84(1):113–20. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedrazzini T, Hug K, Louis JA. Importance of L3T4+ and Lyt-2+ cells in the immunologic control of infection with Mycobacterium bovis strain bacillus Calmette-Guerin in mice. Assessment by elimination of T cell subsets in vivo. Journal of Immunology. 1987;139(6):2032–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper AM, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Griffin JP, Russell DG, Orme IM. Disseminated tuberculosis in interferon gamma gene-disrupted mice. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1993;178(6):2243–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn JL, Chan J, Triebold KJ, Dalton DK, Stewart TA, Bloom BR. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1993;178(6):2249–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jouanguy E, Altare F, Lamhamedi S, Revy P, Emile JF, Newport M, et al. Interferon-gamma-receptor deficiency in an infant with fatal bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(26):1956–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newport MJ, Huxley CM, Huston S, Hawrylowicz CM, Oostra BA, Williamson R, et al. A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335(26):1941–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorensen AL, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen AB. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and Immunity. 1995;63(5):1710–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coler RN, Skeiky YA, Vedvick T, Bement T, Ovendale P, Campos-Neto A, et al. Molecular cloning and immunologic reactivity of a novel low molecular mass antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(5):2356–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alderson MR, Bement T, Day CH, Zhu L, Molesh D, Skeiky YA, et al. Expression Cloning of an Immunodominant Family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Antigens Using Human CD4(+) T Cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191(3):551–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanderson S, Campbell DJ, Shastri N. Identification of a CD4+ T cell-stimulating antigen of pathogenic bacteria by expression cloning. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1995 Dec 1;182(6):1751–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koppi TA, Tough-Bement T, Lewinsohn DM, Lynch DH, Alderson MR. CD40 ligand inhibits Fas/CD95-mediated apoptosis of human blood-derived dendritic cells. European Journal of Immunology. 1997;27(12):3161–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewinsohn DM, Alderson MR, Briden AL, Riddell SR, Reed SG, Grabstein KH. Characterization of human CD8+ T cells reactive with Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected antigen-presenting cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;187(10):1633–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berthet FX, Rasmussen PB, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Gicquel B. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10) Microbiology. 1998;144(Pt 11):3195–203. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colangeli R, Spencer JS, Bifani P, Williams A, Lyashchenko K, Keen MA, et al. MTSA-10, the product of the Rv3874 gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, elicits tuberculosis-specific, delayed-type hypersensitivity in guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 2000 Feb;68(2):990–3. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.990-993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dillon DC, Alderson MR, Day CH, Lewinsohn DM, Coler R, Bement T, et al. Molecular characterization and human T-cell responses to a member of a novel Mycobacterium tuberculosis mtb39 gene family. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(6):2941–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2941-2950.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mettens P, Dubois PM, Demoitie MA, Bayat B, Donner MN, Bourguignon P, et al. Improved T cell responses to Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in mice and monkeys induced by a novel formulation of RTS,S vaccine antigen. Vaccine. 2008 Feb 20;26(8):1072–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skeiky YA, Alderson MR, Ovendale PJ, Guderian JA, Brandt L, Dillon DC, et al. Differential immune responses and protective efficacy induced by components of a tuberculosis polyprotein vaccine, Mtb72F, delivered as naked DNA or recombinant protein. J Immunol. 2004 Jun 15;172(12):7618–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen P. Effective vaccination of mice against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection with a soluble mixture of secreted mycobacterial proteins. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62(6):2536–44. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2536-2544.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orme I. Protective and memory immunity in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunobiology. 1994;191(45):503–8. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pal PG, Horwitz MA. Immunization with extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces cell-mediated immune responses and substantial protective immunity in a guinea pig model of pulmonary tuberculosis. Infection and Immunity. 1992;60(11):4781–92. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4781-4792.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustafa AS, Shaban FA, Abal AT, Al Attiyah R, Wiker HG, Lundin KE, et al. Identification and HLA restriction of naturally derived Th1-cell epitopes from the secreted Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen 85B recognized by antigen-specific human CD4(+) T-cell lines. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(7):3933–40. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3933-3940.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roche PW, Triccas JA, Avery DT, Fifis T, Billman-Jacobe H, Britton WJ. Differential T cell responses to mycobacteria-secreted proteins distinguish vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guerin from infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1994;170(5):1326–30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilkinson RJ, Wilkinson KA, De Smet KA, Haslov K, Pasvol G, Singh M, et al. Human T-and B-cell reactivity to the 16kDa alpha-crystallin protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1998 Oct;48(4):403–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horwitz MA, Lee BW, Dillon BJ, Harth G. Protective immunity against tuberculosis induced by vaccination with major extracellular proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(5):1530–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hewinson RG, Michell SL, Russell WP, McAdam RA, Jacobs WR., Jr Molecular characterization of MPT83: a seroreactive antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with homology to MPT70. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 1996 May;43(5):490–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-78.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillon DC, Alderson MR, Day CH, Bement T, Campos-Neto A, Skeiky YA, et al. Molecular and immunological characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CFP-10, an immunodiagnostic antigen missing in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J Clin Microbiol. 2000 Sep;38(9):3285–90. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3285-3290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skjot RL, Oettinger T, Rosenkrands I, Ravn P, Brock I, Jacobsen S, et al. Comparative evaluation of low-molecular-mass proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies members of the ESAT-6 family as immunodominant T-cell antigens. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(1):214–20. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.214-220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandt L, Elhay M, Rosenkrands I, Lindblad EB, Andersen P. ESAT-6 subunit vaccination against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(2):791–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.791-795.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brandt L, Oettinger T, Holm A, Andersen AB, Andersen P. Key epitopes on the ESAT-6 antigen recognized in mice during the recall of protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Immunology. 1996;157(8):3527–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renshaw PS, Lightbody KL, Veverka V, Muskett FW, Kelly G, Frenkiel TA, et al. Structure and function of the complex formed by the tuberculosis virulence factors CFP-10 and ESAT-6. The EMBO journal. 2005 Jul 20;24(14):2491–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Mathur SK, Zakel KL, Grotzke JE, Lewinsohn DM, et al. Individual RD1-region genes are required for export of ESAT-6/CFP-10 and for virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2004 Jan;51(2):359–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skjot RL, Brock I, Arend SM, Munk ME, Theisen M, Ottenhoff TH, et al. Epitope mapping of the immunodominant antigen TB10.4 and the two homologous proteins TB10.3 and TB12.9, which constitute a subfamily of the esat-6 gene family. Infect Immun. 2002 Oct;70(10):5446–53. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5446-5453.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Renshaw PS, Panagiotidou P, Whelan A, Gordon SV, Hewinson RG, Williamson RA, et al. Conclusive evidence that the major T-cell antigens of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex ESAT-6 and CFP-10 form a tight, 1:1 complex and characterization of the structural properties of ESAT-6, CFP-10, and the ESAT-6*CFP-10 complex. Implications for pathogenesis and virulence. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002 Jun 14;277(24):21598–603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandt L, Skeiky YA, Alderson MR, Lobet Y, Dalemans W, Turner OC, et al. The protective effect of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine is increased by coadministration with the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 72-kilodalton fusion polyprotein Mtb72F in M. tuberculosis-infected guinea pigs. Infect Immun. 2004 Nov;72(11):6622–32. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.11.6622-6632.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huygen K, Content J, Denis O, Montgomery DL, Yawman AM, Deck RR, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine. Nat Med. 1996;2(8):893–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-893. see comments. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reed SG, Alderson MR, Dalemans W, Lobet Y, Skeiky YA. Prospects for a better vaccine against tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2003;83(13):213–9. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsenova L, Harbacheuski R, Moreira AL, Ellison E, Dalemans W, Alderson MR, et al. Evaluation of the Mtb72F polyprotein vaccine in a rabbit model of tuberculous meningitis. Infect Immun. 2006 Apr;74(4):2392–401. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2392-2401.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Pinxteren LA, Cassidy JP, Smedegaard BH, Agger EM, Andersen P. Control of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection is dependent on CD8 T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000 Dec;30(12):3689–98. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200012)30:12<3689::AID-IMMU3689>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Probst P, Stromberg E, Ghalib HW, Mozel M, Badaro R, Reed SG, et al. Identification and characterization of T cell-stimulating antigens from Leishmania by CD4 T cell expression cloning. J Immunol. 2001 Jan 1;166(1):498–505. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodall JC, Yeo G, Huang M, Raggiaschi R, Gaston JS. Identification of Chlamydia trachomatis antigens recognized by human CD4+ T lymphocytes by screening an expression library. Eur J Immunol. 2001 May;31(5):1513–22. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1513::AID-IMMU1513>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]