Abstract

Research shows high comorbidity between Cluster B personality disorders (PDs) and alcohol use disorders (AUDs). Studies on personality traits and alcohol use have identified coping and enhancement drinking motives as mediators in the relations among impulsivity, affective instability, and alcohol use. To the extent that PDs reflect extreme expression of these traits, drinking motives should mediate the relation between PD symptoms and alcohol involvement. This was tested using path models estimating the extent to which coping and enhancement drinking motives mediated the relation between Cluster B symptom counts and alcohol use and problems both concurrently and at a 5-year follow-up. Three hundred fifty-two adults participated in a multiwave study of risk for alcoholism (average age = 29 years at Wave 1). Enhancement motives mediated (a) the cross-sectional relation between Cluster B symptoms and drinking quantity/frequency, heavy drinking, total drinking consequences, dependence features, and AUD diagnosis and (b) the prospective relation to AUDs. Although coping motives mediated the relation between Cluster B symptoms and drinking consequences and dependence features cross-sectionally, prospective effects were limited to indirect effects through Time 1.

Keywords: alcohol use disorders, drinking motives, personality disorder symptoms, personality disorder-alcohol use disorder comorbidity

Research shows high comorbidity between personality disorders (PDs) and alcohol use disorders (AUDs; Ball, Tennen, Poling, Kranzler, & Rounsaville, 1997; Driessen, Veltrup, Wetterling, John, & Dilling, 1998; Morgenstern, Langenbucher, Labouvie, & Miller, 1997; Sher & Trull, 2002; Sher, Trull, Bartholow, & Vieth, 1999; Skodol, Oldham, & Gallagher, 1999; Verheul, Hartgers, Van Den Brink, & Koeter, 1998). For example, across studies of individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) in which rates of alcohol abuse or dependence were reported, approximately 48.8% of individuals with BPD also met criteria for an AUD, and across studies of individuals with AUDs, 14.3% of these participants also met criteria for BPD (Trull, Sher, Minks-Brown, Durbin, & Burr, 2000). Given the high rates of morbidity and dysfunction associated with these disorders, particularly when they co-occur, a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying this relation is needed (Trull et al., 2000). This knowledge would be useful not only for identifying factors relevant to prevention and treatment of PD-AUD comorbidity but also for understanding each disorder better through identification of the underlying processes or factors that affect both (Trull et al., 2000).

According to dimensional perspectives of PDs, the underlying personality traits of impulsivity and affective instability/negative affectivity are two such factors that may account for high rates of AUDs among specific PDs (Trull et al., 2000, Trull, Waudby, & Sher, 2004). Dimensional perspectives assert that PDs represent maladaptive and extreme variations of normal personality traits (see Trull & Durrett, 2005, for a review). Impulsivity and negative affectivity are two such traits that are represented in the normal population, as evidenced by their representation in standard conceptualizations of personality such as the five-factor model and by the finding that extreme levels of these traits are characteristic of Cluster B PDs (e.g., BPD, antisocial personality disorder), which are the PDs most likely to co-occur with AUDs (Trull et al., 2000, 2004). Furthermore, high scores on measures of these traits are associated with alcohol use problems (Sher et al., 1999). For example, impulsivity in childhood and adolescence is related to greater risk of future alcohol dependence (e.g., Bates & Labouvie, 1995; Caspi et al., 1997; Cloninger, Sigvardsson, & Bohman, 1988; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992; Schuckit, 1998; Zucker, Fitzgerald, & Moses, 1995), and adults with high impulsivity scores are more likely to be diagnosed with alcoholism (e.g., Bergman & Brismar, 1994), as are offspring of highly impulsive individuals (e.g., Alterman et al., 1998; Sher, 1991).

Negative affectivity and problems with emotion regulation are considered by some to be a major feature driving comorbidity of Cluster B disorders (e.g., BPD; Linehan, 1993) and substance use disorder. Because these Cluster B PDs involve lack of the ability to regulate one’s emotional states, some suggest that substance abuse results from the attempt to regulate negative emotions. Consistent with this hypothesis, negative affectivity is characteristic of both AUDs and mood disorders such as anxiety and depression (e.g., Kessler et al., 1997; Kushner et al., 1996; Sher & Trull, 1994), and scores on measures of negative affectivity are higher among individuals who meet criteria for AUDs (e.g., Brooner, Templer, Svikis, Schmidt, & Monopolis, 1990; Meszaros, Willinger, Fischer, Schonbeck, & Aschauer, 1996) and vice versa (e.g., McGue, Slutske, Taylor, & Iacono, 1997). This relationship has also been demonstrated in nonclinical samples (Sher et al., 1999), where participants with higher negative affectivity scores were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for an AUD.

Drinking motives are one set of factors that have been identified as potential mediators in the relation between impulsivity and affective instability and alcohol use (Cooper, 1994). Drinking motives are hypothesized to represent the functions alcohol use is serving for individuals and are thought to be the proximal mechanisms through which other factors, such as personality traits, operate (Sher et al., 1999). Drinking to cope with negative subjective states and emotions (coping motives) and drinking to enhance positive emotions (enhancement motives; Cooper, 1994) are the two types of motives predicted to be most relevant for explaining the relation between Cluster B PDs and alcohol problems. Given that problems with emotion regulation and affective instability are characteristic of Cluster B personality disorders (Linehan, 1993; Newhill, Mulvey, & Pilkonis, 2004; Trull, 1992, 2001; Trull et al., 2000), it follows that the alcohol use of individuals with Cluster B PDs might be motivated by the desire to cope with these negative emotions. Furthermore, in personality trait research in normal populations, coping motives tend to be associated with personality traits such as emotional instability (Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005; Theakston, Stewart, Dawson, Knowlden-Lowene, & Lehman, 2004) and negative affectivity (Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001; Stewart & Devine, 2000). Enhancement motives tend to be associated with low conscientiousness (Stewart & Devine, 2000; Stewart, Loughlin, & Rhyno, 2001; Theakston et al., 2004) and impulsivity (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000), two features relevant to Cluster B PDs such as BPD (Trull et al., 2000) and antisocial personality disorder (Slutske et al., 2002).

These two motives are also important because they are likely to be associated with the excessive alcohol consumption and negative alcohol consequences characteristic of the substance abuse problems commonly seen in PD individuals. A recent review of the drinking motives literature (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005) found that coping motives are the most likely to lead to negative consequences from drinking, whereas enhancement motives tend to have the highest associations with heavy drinking, which in turn leads to alcohol-related problems. Coping motives have been shown to lead to drinking problems both directly and indirectly, whereas enhancement motives typically lead to drinking problems indirectly through heavier alcohol consumption (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992; Cutter & O’Farrell, 1984; McCarty & Kaye, 1984; Simons et al., 2005).

The purpose of the present study was to test the extent to which coping and enhancement motives mediate the relation from personality disorder symptoms to alcohol use and alcohol-related problems concurrently and prospectively. These relations were tested in a middle-adult (average ages ranging from 29 to 34) sample. Predicted alcohol use and related problems included the variables of drinking quantity/frequency, heavy episodic drinking, total consequences from drinking, dependence features, and presence of an AUD. Specifically, we hypothesized that coping and enhancement motives would mediate the relation between alcohol-related problems and Cluster B PD symptoms, because dimensional perspectives of PDs assert that Cluster B disorders are rooted in high levels of impulsivity and affective instability compared with those PDs that are not conceptualized as a combination of these traits. Thus we tested the relations from Cluster B PD symptoms to coping and enhancement motives to alcohol-related problems while controlling for the interrelations among other PD clusters that are not assumed to involve the combination of both high impulsivity and high affective instability.

Method

These data were collected as part of a longitudinal study of young adults at risk for alcoholism. In the fall of 1987 at the University of Missouri—Columbia, approximately 80% of the incoming freshmen (all first-time college freshman who had never taken a full semester of credit hours at any postsecondary institution, N = 3,944) were contacted and asked to participate in a multiyear longitudinal research study. Approximately 80% (n = 3,156) agreed to participate and were screened for inclusion in a research study that examined a range of variables related to alcohol use and abuse (see Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991, for additional detail). Four hundred eighty-nine of those screened were selected. This sample included approximately equal numbers of men and women, and around half were considered at risk for alcoholism on the basis of interview and self-report data that indicated family histories of paternal alcoholism. Participants completed questionnaires and structured interviews measuring problems associated with alcohol and other substances at each of seven waves of assessment across 16 years (at Years 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 11, and 16). Measures of personality disorder symptomology were completed at Year 11, when most participants were 28-29 years of age. Therefore, the present study consists of data from the 11th year and the 16th year, thereby comprising two waves of data collection across a span of 5 years (see Table 1). The ordering of interviews was counterbalanced to account for any possible order effects. All procedures and measures were approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board, participants’ consent was obtained before they contributed any data, and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the federal government to protect participants’ confidentiality to the fullest extent of the law.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics.

| Variable | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A symptom count | 0.26 | 0.73 | 4.52 | 28.19 |

| Cluster B symptom count | 1.38 | 1.94 | 1.88 | 4.18 |

| Cluster C symptom count | 0.65 | 1.22 | 2.89 | 10.26 |

| Enhancement motives | 1.30 | 0.77 | -0.33 | -0.97 |

| Coping motives | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.84 | -0.32 |

| Alcohol quantity/frequency, Year 11 | 3.43 | 5.93 | 3.80 | 19.67 |

| Heavy drinking, Year 11 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 3.49 | 14.13 |

| Total consequences, Year 11 | 0.45 | 0.99 | 3.28 | 14.78 |

| Dependence features, Year 11 | 0.57 | 1.07 | 2.51 | 7.68 |

| Alcohol quantity/frequency, Year 16 | 3.93 | 9.71 | 10.31 | 147.09 |

| Heavy drinking, Year 16 | 0.32 | 0.72 | 3.98 | 18.53 |

| Total consequences, Year 16 | 0.42 | 0.90 | 2.73 | 8.62 |

| Dependence features, Year 16 | 0.57 | 1.26 | 3.30 | 13.43 |

Note. N = 352.

Participants

Participants included 155 men and 197 women with an average age of 29 years (SD = 1.02) at Year 11 and 34 years (SD = 0.83) at Year 16. Participants were primarily Caucasian (94.43%), but 3.69% were African American, 0.57% were Hispanic, 0.28% were Native American, and 1.14% were Asian American. Participants were above average in educational attainment, as 81.01% held a college or advanced degree. At Year 16, 74.93% of participants were married, 1.14% were separated, 4.56% were currently divorced, 1.14% were engaged, and 17.66% had never been married. At Year 11, 20.51% (37 men, 22 women) met criteria for a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition, DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of an AUD (past-year), compared with 15% (29 men, 23 women) at Year 16. Only 2.28% met criteria for a DSM-IV personality disorder diagnosis at the time of the Year 11 assessment. Because these diagnoses were primarily due to diagnoses of two specific PDs (obsessive-compulsive and antisocial), only overall cluster symptom counts were used for the present analyses. The low base rates for personality disorders, the lack of a diverse ethnic population, and the high educational attainment of participants are important to note, as these participants are not representative of the general population.

Materials and Procedure

AUD diagnoses

For our criterion measure of alcohol use diagnoses, we assessed past year DSM-IV AUD (abuse or dependence) and antisocial personality disorder at Years 11 and 16 using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV (DIS-IV; Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, 1995). For Year 11, interviewers completed the DIS-IV training workshop offered by the DIS-IV training staff before collecting data. Year 16 interviewers were trained by senior, experienced research staff. All interviews (both Years 11 and 16) were cross-edited by a second interviewer and an interview supervisor.

Personality disorder symptoms

For all PDs except antisocial PD, which we assessed with the DIS-IV, we assessed DSM-IV personality disorder symptoms in each participant by administering the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV; Pfolh, Blum, & Zimmerman, 1997) at Year 11. The SIDP-IV provides total symptom counts for each of the 10 individual DSM-IV personality disorders as well as diagnoses. Further, it was possible to calculate symptom counts for each of the three DSM-IV PD clusters: Cluster A (odd-eccentric) includes the paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal PDs; Cluster B (dramatic-erratic-emotional) includes the antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic PDs; and Cluster C (anxious-fearful) includes the avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive PDs.

Two master’s-level interviewers administered the SIDP-IV and DIS-IV interviews. These interviewers underwent extensive training before gathering data for this study. Training in the SIDP-IV was supervised by one of the authors of the SIDP-IV (Nancee Blum) and by Timothy J. Trull. These training sessions involved giving didactic instruction, reviewing written materials, reviewing and scoring previously taped interviews using the SIDP-IV, and conducting and scoring at least 10 practice SIDP-IV interviews that were reviewed and evaluated by the supervisor. The interviewers met weekly with senior project staff to discuss any questions regarding administration or scoring. All interviews were audiotaped, and 36 participants’ interviews were randomly selected to assess the interrater reliability of SIDP-IV scores. (Given the highly structured nature of the DIS-IV, we only conducted reliability analyses on the SIDP-IV). Intraclass correlations (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) were calculated by comparing the original symptom counts for each PD as well as the three cluster symptom counts with the corresponding independent reliability check ratings. For the individual PD symptom counts, the average intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was .73 (range = .43-.90). The ICCs for Cluster A, Cluster B, and Cluster C symptom counts were .80, .92, and .89, respectively.

Drinking motives

Coping and enhancement motives were assessed using items from Cooper’s (1994) drinking motives scales. Coping included five items such as “drink to forget about your problems” and “drink to forget about worries”. Enhancement included five items such as “drink because it’s exciting” and “drink because it gives me a pleasant feeling.” Items were rated on a scale from 0 (strongly agree) to 3 (strongly disagree). Items were reverse-scored so that high scores reflected greater endorsement of each motive. Coping and enhancement motive composites were created using an average of the five items on each scale. Coefficient alphas for coping and enhancement items were .84 and .87, respectively.

Alcohol-related variables

Measures of quantity/frequency of alcohol use, frequency of heavy drinking, measures of types of negative consequences from alcohol, and a measure of alcohol dependence features were included in questionnaire format. Alcohol quantity/frequency was calculated on the basis of items asking participants to report consumption of alcohol in the form of beer, wine, wine coolers, and hard liquor in the past 30 days, as well as in the past year (and recalculated as an index of average consumption per month). A heavy drinking composite item (α = .91) was also calculated and was based on participants’ reports of the number of times per week they consumed five or more drinks at a single sitting, the number of times participants felt “high” or “light-headed” as a result of drinking, and the number of times participants reported feeling drunk. Alcohol consequences were assessed using a list of 14 negative effects of alcohol consumption that were combined into a composite of total consequences (α = .74). Items included negative consequences from drinking alcohol such as neglecting obligations for 2 or more days because of drinking and getting into trouble at work or school. Dependence features were measured using a count of the total number of dependence features endorsed by the participant on a self-report questionnaire (see Sher et al., 1991).

Results

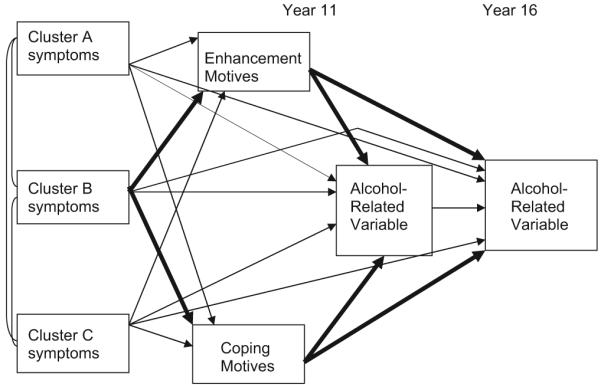

We conducted a series of path analyses using Mplus version 3.13 (Muthén & Muthén, 2005) to test the hypothesis that the relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms (expected to reflect impulsive and affectively unstable personality traits) and Year 16 alcohol-related variables was mediated by Year 11 drinking motives. We used the “model indirect” command in Mplus, which provides standardized estimates and significance tests of both specific (e.g., one mediator) and total (e.g., multiple mediators) indirect effects. The unstandardized coefficient for the indirect effect reflects the change in the outcome variable associated with one unit change in the predictor variable. More information on this technique can be found in MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004). Given that a number of the variables used in the present study were highly skewed, we tested models using estimation procedures that are robust to non-normality (producing adjusted chi-square statistics and standard errors). For continuous outcomes, we used a maximum likelihood estimator (MLMV), and for the categorical AUD outcome variable, we used a weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV). Symptoms associated with other PD clusters (A and C) were also modeled to minimize misspecification error due to variable omission, but they were not expected to relate as strongly to alcohol variables or drinking motives. Sex was modeled as an exogenous variable with paths to all other variables to account for the possible sex confounding.1 Separate fully saturated models were estimated for each dependent alcohol-related variable. Figure 1 provides a graphical display of the overall model (with the exception of the paths from sex to all other variables). Hypothesized directional paths were examined in the context of a fully saturated model, to control for all possible relations from Year 11 variables to Year 16 dependent measures. Mediation tests were conducted using Mplus. Clusters A, B and C symptom counts were correlated to account for shared variability, as were coping and enhancement motives, and paths from cluster symptom counts to both drinking motives and alcohol-related variables at Years 11 and 16 were included to ensure that the paths from Cluster B symptoms to all endogenous variables reflected variance unique to Cluster B symptoms.

Figure 1.

Path model of structural paths from Year 11 personality disorder symptoms to Year 11 drinking motives to alcohol-related variables (Year 11 and Year 16).

Bivariate correlations among upstream variables (i.e., cluster symptom counts and drinking motives) are presented in Table 2; correlations between upstream variables and downstream (i.e., alcohol-related) variables are presented in Table 3. Direct effects of sex, drinking motives, and PD symptom counts on alcohol-related variables (with indirect relationships controlled) are presented in Table 4. Stability coefficients from Year 11 alcohol variables to Year 16 alcohol variables were included to differentiate that variance which was shared uniquely between Year 11 drinking motives and Year 16 alcohol consumption or problems from that which was shared only through the relation between drinking motives and concurrent (Year 11) alcohol consumption or problems (see Table 4). This distinction is important. Mediation of the effects of motives on Year 16 alcohol variables only through concurrent Year 11 alcohol variables does not attest to the ability of motives to predict subsequent alcohol variables above and beyond what is accounted for by their relations to baseline alcohol variable levels and therefore remains agnostic as to the directionality of these effects. On the other hand, effects of motives on subsequent alcohol variables independent of the effect accounted for by Year 11 alcohol variable levels allow for tentative conclusions that motives can uniquely predict alcohol use and consequences.

Table 2. Correlations Among Independent Variables.

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cluster A | — | .36*** | .37*** | .03 | .08 |

| 2. Cluster B | — | .31*** | .25*** | .24*** | |

| 3. Cluster C | — | .09 | .16** | ||

| 4. Enhancement | — | .57*** | |||

| 5. Coping | — |

p < .01.

p < .0001.

Table 3. Correlations Between Personality Disorder Symptom Counts, Drinking Motives, and Alcohol-Related Variables at Year 11 and Year 16.

| Variable | Quantity/frequency (Year 11/Year 16) | Heavy drinking (Year 11/Year 16) | Total consequences (Year 11/Year 16) | Dependence features (Year 11/Year 16) | AUD (Year 11/Year 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A count | -.04/-.07 | -.02/-.06 | -.02/-.02 | .10/.01 | .07/-.04 |

| Cluster B count | .21**/.15** | .26**/.21** | .29**/.22** | .36**/.26** | .40**/.33** |

| Cluster C count | -.04/-.00 | -.04/-.02 | .00/-.01 | .07/-.00 | .11/.01 |

| Enhancement | .30**/.16* | .36**/.32** | .35**/.37** | .33**/.34** | .49**/.46** |

| Coping | .27**/.11* | .14*/.19** | .33**/.31** | .40**/.32** | .37**/.34** |

| Bivariate correlations, Year 11 to Year 16 | .63 | .56 | .47 | .54 | .46 |

Note. N = 352. Quantity/frequency = composite based on reported consumption of alcohol (beer, wine, wine coolers, hard liquor) in the past 30 days and the past year recalculated as an index of average consumption per month; Heavy drinking = composite based on the number of times per week participants reported consuming five or more drinks at a single sitting, feeling “high” or “light-headed” as a result of drinking, and felt drunk; Total consequences = count of the number of consequences endorsed; dependence features = a count of the total number of dependence features endorsed by the participant, such as feeling dependent on alcohol and being unable to stop after having several drinks; AUD = past-year alcohol use disorder according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

p < .05.

p < .001.

Table 4. Direct Paths From Sex, Drinking Motives, and Personality Disorder Symptom Counts to Alcohol-Related Variables at Years 11 and 16, With Indirect Paths Controlled.

| Variable | Cross-sectional effect (Year 11) | Prospective effect (Year 16) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity/frequency of drinking (Q/F) | ||

| Sex | -.20*** | -.04 |

| Enhancement | .27*** | -.09 |

| Coping | .03 | .01 |

| Cluster A | -.12* | -.07** |

| Cluster B | .21** | .00 |

| Cluster C | -.05 | .03 |

| Q/F, Year 11 | — | .65** |

| Heavy drinking (HD) | ||

| Sex | -.19*** | -.06 |

| Enhancement | .30*** | .11 |

| Coping | -.03 | .04 |

| Cluster A | -.11** | -.08** |

| Cluster B | .26*** | .06 |

| Cluster C | -.09* | -.00 |

| HD, Year 11 | — | .48*** |

| Total consequences (T Con) | ||

| Sex | .02 | -.05 |

| Enhancement | .18*** | .18*** |

| Coping | .16** | .01 |

| Cluster A | -.12** | -.04 |

| Cluster B | .30*** | .07 |

| Cluster C | -.05 | -.06 |

| T Con, Year 11 | — | .35*** |

| Dependence features (Depen) | ||

| Sex | .04 | .08 |

| Enhancement | .16** | .13** |

| Coping | .22** | .07 |

| Cluster A | .00 | -.05 |

| Cluster B | .35*** | .09 |

| Cluster C | -.05 | -.09 |

| Depen, Year 11 | — | .44** |

| AUD | ||

| Sex | -.12 | -.01 |

| Enhancement | .36*** | .26** |

| Coping | .10 | .08 |

| Cluster A | -.04 | -.10 |

| Cluster B | .32*** | .23** |

| Cluster C | -.03 | -.09 |

| AUD, Year 11 | — | .23 |

Note. N = 352. Q/F = quantity/frequency composite based on reported consumption of alcohol (beer, wine, wine coolers, hard liquor) in the past 30 days and the past year recalculated as an index of average consumption per month; HD = heaving drinking composite based on the number of times per week participants reported consuming five or more drinks at a single sitting, feeling “high” or “light-headed” as a result of drinking, and felt drunk; T Con = count of the number of consequences endorsed; Depen = a count of the total number of dependence features endorsed by the participant, such as feeling dependent on alcohol and being unable to stop after having several drinks; AUD = past-year alcohol use disorder according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The results for each alcohol-related criterion variable are presented in Tables 4 (direct effects only) and 5 (indirect effects compared with Cluster B direct effects). Fit statistics are not provided, as all models were just identified (using all manifest variables) and therefore provided perfect fit to the data.

Table 5. Standardized Coefficients for Indirect Effects From Cluster B Personality Disorder Symptom Counts to Alcohol-Related Variables, With Direct Effects for Comparison, at Years 11 and 16, and With Clusters A and C Symptom Counts Controlled.

| Variable | Cross-sectional (Year 11) |

Unique prospective (Year 16) |

Prospective (Year 11 to Year 16) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Via E | Via C | Direct | Via E | Via C | Via E | Via C | Direct | |

| Quantity/frequency | .07** | .01 | .21* | -.02 | .00 | .04* | .00 | .00 |

| Heavy drinking | .07*** | -.01 | .26*** | .03 | .01 | .04** | -.00 | .06 |

| Total consequences | .04** | .04 | .30*** | .04** | .02 | .02* | .01 | .07 |

| Dependence | .04** | .05** | .35*** | .03** | .02 | .02* | .02* | .09 |

| AUD | .08* | .02 | .32*** | .05* | .01 | .02 | .00 | .25** |

Note. N = 352, except for AUD, for which N = 351. Via E = indirect effect of Cluster B symptom count through enhancement (E) drinking motives; Via C = indirect effect of Cluster B symptom count through coping (C) drinking motives; Direct = direct effect of Cluster B symptom count; Quantity/frequency = composite based on reported consumption of alcohol (beer, wine, wine coolers, hard liquor) in the past 30 days and the past year recalculated as an index of average consumption per month; Heavy drinking = composite based on the number of times per week participants reported consuming five or more drinks at a single sitting, feeling “high” or “light-headed” as a result of drinking, and felt drunk; Total consequences = count of the number of consequences endorsed; Dependence = a count of the total number of dependence features endorsed by the participant, such as feeling dependent on alcohol and being unable to stop after having several drinks; AUD = past-year alcohol use disorder according to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Three types of mediation were tested in the present study. First, cross-sectional mediation represents the case in which all variables of interest were measured at a single time point, and the test of mediation therefore consists of testing the extent to which variance shared by both the alcohol-related outcome variable and Cluster B symptoms is accounted for by shared variance with drinking motives. This type of mediation does not address the direction of these relationships and therefore does not warrant a strong conclusion about whether Cluster B symptoms or drinking motives lead to subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. In addition to this cross-sectional mediation, there are also two types of prospective mediation. The first type of prospective mediation, typically thought of when prospective mediation is discussed, is a test of the effects of a predictor and a mediating variable on an outcome variable at a later point in time while one controls for concurrent shared variance among the predictor and outcome variables at the initial time point. In this type of mediation, inferences concerning direction are more appropriate to consider given that the initial levels of the outcome variable are controlled while one examines the effects of the variables on later levels of the variable being predicted. Although the effects of such mediation are highly suggestive, care still must be exercised in drawing inferences because unreliability in the measurement of alcohol use at both time points can lead to less than perfect control for autoregressivity. That is, the baseline measurement of the mediator may be stealthily associated with baseline variation in the alcohol-related variable that is not assessed, and the prospective path from the mediator to the outcome can carry forward this “hidden” autoregressivity. In addition, unmeasured third variables could be uniquely associated with the mediator at baseline and the alcohol-related variable at follow-up and create a spurious association implying mediation.

A second type of prospective mediation, however, is more similar to cross-sectional mediation in the conclusions that can be drawn with respect to directionality. In this instance, the variables of interest are measured at a single time point, as in cross-sectional mediation, with the addition that the outcome variable is also measured at a second time point. In this case, the mediating variable(s) can account for variance in the prospective outcome variable through a relation with the outcome variable measured at a concurrent time point. In other words, in this type of mediation, the effects of the mediating and exogenous variables are only indirectly demonstrated through the stability of the outcome variable from the first to the second time point. Similar to cross-sectional mediation, this type of prospective mediation does not allow for any conclusions regarding the directionality of effects but may still represent the most realistic mechanism under consideration and needs to be considered. These three types of mediation are henceforth referred to as cross-sectional mediation, unique prospective mediation, and prospective mediation via Year 11, respectively. The results for these three types of mediation are presented in Table 5.

Cross-Sectional Mediation

As shown in the first three columns of Table 5 (labeled “Cross-sectional”), enhancement motives partially mediated the cross-sectional relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms and Year 11 alcohol quantity/frequency, heavy drinking, total consequences, dependence features, and AUD diagnosis. This is demonstrated by the finding that all of the indirect effects through enhancement (presented in column 1 of Table 5, labeled “Via E”) are significant but can be considered only a partial mediation of the effect given that the direct effects of Cluster B symptoms on Year 11 alcohol variables are also significant when one controls for indirect effects (presented in column 3 of Table 5, labeled “Direct”). Coping motives partially mediated the relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms and dependence features. This is demonstrated by the significant indirect effect for coping motives (presented in column 2 of Table 5, labeled “Via C”) along with the significant direct effect for Cluster B symptoms that could not be accounted for by the indirect effect (presented in column 3 of Table 5, labeled “Direct”). This result is consistent with previous research showing that, compared with enhancement motives, coping motives are more directly related to alcohol dependence, rather than operating through frequency of heavy drinking (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998).

Unique Prospective Mediation

The effects for unique prospective mediation are shown in the fourth and fifth columns of Table 5 (labeled “Unique prospective”) in conjunction with column 8 (labeled “Direct”). As shown in column 4, the indirect effects from Cluster B symptoms to enhancement motives to Year 16 total consequences, dependence features, and AUD were significant, whereas those on drinking quantity/frequency and heavy drinking were not significant. These findings, when compared with the lack of significant direct effects of Cluster B symptoms on these variables (see column 8 of Table 5), show that the relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms and Year 16 total consequences and dependence features was fully mediated by enhancement motives. Although the direct effects were larger in magnitude than the combined indirect effects, these results reached the criteria for full mediation given that the direct effect was not significant after indirect effects were controlled. For Year 16 AUD, however, the indirect effect through enhancement motives was significant (see column 4), but the direct effect was also significant (see column 8). This shows that the effect of Cluster B symptoms on Year 16 AUD diagnosis was only partially mediated by enhancement motives. In other words, enhancement motives were a significant mediator of the relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms and Year 16 alcohol consequences, dependence features, and AUD diagnosis above and beyond prior levels of alcohol consequences, dependence, or presence of a diagnosis. This provides some support for our hypotheses by demonstrating that, at least with respect to alcohol consequences, drinking to enhance positive emotions can partially account for the effects of Cluster B symptoms on later alcohol problems. However, the hypothesis that drinking to cope with negative emotions accounts for this effect was not supported, as indicated by the lack of any significant indirect effects in column 5.

Prospective Mediation via Year 11

The results for prospective mediation via Year 11 are presented in the sixth and seventh columns of Table 5 (under “Prospective”), along with direct effects for Year 16 in column 8. Consistent with the results for cross-sectional mediation, enhancement motives mediated the relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms and Year 16 alcohol use quantity/frequency, heavy drinking, total consequences, and dependence features through their stability coefficients (see column 6). Coping motives also mediated the relation between Year 11 Cluster B symptoms and dependence features (see column 7). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that Cluster B effects on later drinking outcomes, with the exception of AUD diagnosis outcomes, are due to the stability of drinking patterns that are motivated in part by drinking motives. That is, all of the drinking motive mediation is “in place” at the beginning of the observation period, and its enduring influence is further mediated by the stability of drinking.

Example: Indirect Effects of Cluster B Symptoms on Heavy Drinking Through Enhancement Motives

In this section we present an example from Table 5 to demonstrate how the cross-sectional, unique prospective, and prospective via Year 11 results for the indirect effects of Cluster B symptoms on heavy drinking through enhancement motives can be obtained from the table. First, to determine the cross-sectional effects, note that the first column of Table 5 shows that the cross-sectional effect from Cluster B to heavy drinking mediated by enhancement motives is .07***. This path is significant, but the third column shows that the direct effect from Cluster B to heavy drinking is also significant (.26***), indicating that the indirect relation only partially mediates the overall effect. For unique prospective mediation, the fourth column shows that the indirect effect on heavy drinking through enhancement motives is not significant (.03). For the prospective effect via Year 11, the sixth column shows that the indirect effect of Cluster B on heavy drinking through enhancement motives is significant (.04**). So, enhancement motives (a) partially mediated the cross-sectional relation between Cluster B and heavy drinking, (b) did not show unique prospective mediation on the relation between Cluster B and heavy drinking, but (c) did show mediation of the relation between Cluster B and heavy drinking at Year 16 through the stability path for heavy drinking from Year 11 to Year 16.

Discussion

Consistent with predictions, enhancement and coping drinking motives partially accounted for the relation between PD symptoms characterized by high impulsivity and negative affectivity and alcohol-related variables. However, the effects for coping motives were limited to tests of mediation that are agnostic with respect to the directionality of effects. Only enhancement motives were shown to mediate the effects of Cluster B symptoms on alcohol-related variables at a later time point when initial levels of the alcohol-related variables were controlled.

Although coping motives were not as important as we predicted in accounting for the relationship between Cluster B symptoms and alcohol variables, their pattern of results was consistent with previous literature in demonstrating a stronger relationship between coping motives and the negative consequences associated with drinking (rather than consumption per se; Cooper et al., 1992; Cutter & O’Farrell, 1984; Kuntsche et al., 2005; McCarty & Kaye, 1984; Simons et al., 2005). In terms of accounting for alcohol consumption, as well as helping in the prediction of subsequent AUD diagnosis, enhancement motives were stronger mediators in the present analyses, which is consistent with the larger literature (Cooper et al., 1992; Cutter & O’Farrell, 1984; McCarty & Kaye, 1984).

These results support dimensional perspectives of PDs that emphasize a continuum of normal personality traits and personality pathology, particularly the assertion that extreme levels of the traits of impulsivity and affective instability underlie Cluster B PDs and their relation to AUDs (Trull et al., 2000). Given evidence that Cluster B disorders share roots in normal personality traits of impulsivity and affective instability (Trull, 1992, 2001), drinking motives that have been shown to be related to standard measures of these traits (Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; McCrae & Costa, 1985; Simons et al., 2005; Stewart & Devine, 2000; Stewart et al., 2001; Theakston et al., 2004) were in fact related to symptoms of Cluster B PDs. This finding supports the utility of considering PDs from a dimensional perspective. The lack of significant mediation of these motives for the relation from Clusters A and C symptoms to alcohol-related variables further strengthens this conclusion, (a) by showing that the effects for motives are specific to PD symptoms that are expected to correspond to high levels of affective instability and impulsivity and (b) through the specificity of the effects, which indicates that these relations are unlikely to be due to high levels of general dysfunction or distress.

Several implications for understanding and treating the alcohol use problems among individuals with PDs follow. First, results suggest that alcohol use among individuals with Cluster B PDs may be primarily a function of regulation of positive emotions but may also include regulation of negative emotions. Therefore, treatments for individuals with comorbid AUD and PD diagnoses might be most effective by focusing broadly on emotion regulation, both positive and negative (most treatment approaches focus primarily on negative emotion regulation). Second, although their high intercorrelation must be considered, the finding that coping and enhancement motives showed differential prediction for specific alcohol-related problems indicates that the distinction between them may be important. Although enhancement motives predicted heavy and frequent alcohol use and the presence of an AUD diagnosis, drinking to cope with negative emotions was limited to symptoms of being dependent on alcohol. Coping motives are less likely to be associated with measures of alcohol consumption quantity or frequency (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998; Simons et al., 2005) but are useful for differentiating among problem and nonproblem drinkers (Carpenter & Hasin, 1998) and are a risk factor for future alcohol dependence (Carpenter & Hasin, 1999). Therefore, determining whether an individual with Cluster B PD features is primarily using alcohol to cope with negative emotions, to enhance positive emotions, or both may help clinicians predict specific alcohol-related problems an individual is likely to encounter. For instance, individuals who report using alcohol primarily in situations to enhance positive emotions might be at risk for problems associated with frequently consuming large amounts of alcohol or binge drinking, whereas individuals who report using alcohol to cope with negative emotions might be more at risk for becoming physically or emotionally dependent on alcohol. In addition, using alcohol to cope with negative emotions can presumably lead to alcohol’s being used in contexts where it is usually proscribed (e.g., the workplace) or in social situations (e.g., marital arguments) where the effects of intoxication are much more likely to lead to negative consequences. In this case, the issue is not so much the amount of alcohol consumed, but rather how and when it is consumed. Use in situations deemed socially inappropriate or where emotional provocations may occur may be much more important in understanding coping-related drinking patterns and may explain the relative lack of association of coping motives with consumption-based measures but not problem-based measures in both this and other studies.

The finding that drinking motives only partially accounted for the relation between Cluster B symptoms and alcohol consumption and consequences suggests that additional factors beyond the expectancies, past experiences, and drives captured in the measurement of enhancement and coping drinking motives may have contributed to the relation between Cluster B symptoms and alcohol use. One avenue for future research should therefore be to identify additional variables that may account for this relationship. For example, one possibility includes the other factors associated with alcohol use that have been identified in previous research with normal populations, such as deviant peer group associations, novelty seeking, or other individual difference or environmental variables that may not be adequately captured in measures of drinking motives.

Aside from the findings pertaining to drinking motives, we also found that Cluster A symptoms were directly negatively related to alcohol use, and there was no association between Cluster C PD symptoms and alcohol-related problems. Overall, the findings for the three clusters are consistent with perspectives emphasizing that the underlying traits of impulsivity and affective instability shared by Cluster B PDs help explain alcohol use among those with these PDs (see Sher & Trull, 2002). In contrast, although Clusters A and C PDs may involve high levels of specific negative emotions, they are less closely tied to the traits of affective instability and impulsivity as their essential or driving features (e.g., Cluster A PDs).

With regard to the significant negative association between Cluster A PD symptoms and alcohol use, it may be that Cluster A tendencies toward isolation (see Widiger, Trull, Clarkin, Sanderson, & Costa, 2002) and high levels of introversion (Trull, 1992; Trull, Widiger, & Burr, 2001) lead to decreased social engagement, which in turn suppresses drinking, which is largely a social phenomenon. In sum, future research is needed to understand mechanisms that may lead to lower rates of drinking among those with other PDs (e.g., social isolation) and how the specific facets of personality (e.g., impulsivity and the specific types of negative emotions such as anger, sadness, and anxiety) may differentially contribute to the associations between Cluster B symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use.

One limitation of the present study is that the population consisted of nonclinical participants. This is evidenced by the low rate of diagnosable PDs. Future research is needed to test whether drinking motives operate similarly in clinical samples. One suggestion for future research is to test these relationships among samples that show higher rates of PDs. This type of replication would add evidence to the generalizability of these effects by showing that they are not only a function of normal-range functioning levels of these personality traits or alcohol use patterns. This would also enable tests of these relations among each of the specific PDs individually. Testing each PD for its specific pathways to alcohol use through mediators such as drinking motives is important for identifying possible etiological distinctions between these disorders as well as potential differences in the mechanisms underlying comorbidity with AUDs. For example, whereas antisocial PD-AUD comorbidity may be primarily driven by elevated levels of impulsivity, BPD-AUD comorbidity may be driven by a combination of impulsivity and affective instability. Testing the relation between alcohol-related problems and specific PD symptomatology would also be important for identifying specific AUD-PD relations that, while they may be important for a specific PD, may not be consistent across the other PDs in a particular cluster (e.g., comorbidity between paranoid and avoidant PDs and AUDs, see Sher & Trull, 2002) and may therefore not be identifiable using the method used in the present study.

In summary, these results have two primary implications. First, enhancement motives were more relevant to understanding the relations between Cluster B PD symptoms and alcohol use quantity/frequency, heavy drinking, and development of an AUD. The association between enhancement motives and the trait of impulsivity in previous research implicates the feature of impulsivity as a major underlying dimension in the relation between Cluster B disorders and alcohol problems. In contrast, whereas coping motives were hypothesized to relate to drinking through the connection to the underlying trait of affective instability and emotional dysregulation among PD symptoms, coping motives were only relevant to more severe consequences and dependence features, and these relations were only demonstrated cross-sectionally and prospectively, indirectly through the stability of alcohol variables. Thus, treatment of those with comorbid AUDs and PDs, or those whose Cluster B symptoms also pose a risk for the development of an AUD, should focus not only on developing more adaptive coping strategies but also on finding alternative approaches to meeting these individuals’ needs for obtaining or maintaining positive affective states. Second, these results support dimensional and/or continuum perspectives of PDs by showing that mechanisms identified in research on broad personality domains also apply to PDs believed to be rooted in normal personality constructs.

Acknowledgments

The present research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32 AA13526 and AA13987 awarded to Kenneth J. Sher and by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH52695 awarded to Timothy J. Trull.

Footnotes

As an alternative test of gender differences within these models, we conducted multigroup analyses using Mplus. For each dependent variable, the model was estimated separately for men and women without constraining paths to equality across groups (an unconstrained baseline model). The chi-square for the unconstrained model was then compared with the chi-square from a model in which all paths were constrained to be equal for men and women (constrained model). For alcohol quantity/frequency, alcohol consequences, and AUD, there was not a significant difference in chi-squares between constrained and unconstrained models: Δχ2(3) = 3.31, p = .346, Δχ2(11) = 15.52, p = .16, and Δχ2(12) = 11.94, p = .451, respectively. For heavy drinking and dependence symptoms, there was a significant difference between the constrained and unconstrained models: Δχ2(10) = 19.43, p = .035, and Δχ2(10) = 27.34, p = .002, respectively. For heavy drinking, this difference was no longer significant after we relaxed the constraint on the direct path from Cluster B symptoms to heavy drinking at Year 11, Δχ2(9) = 14.53, p = .105. Comparison of the magnitudes of the unconstrained path for each gender indicated that the path from Cluster B symptoms to heavy drinking was stronger among men (β= .34) than among women (β = .13). For alcohol dependence symptoms, the chi-square difference between constrained and unconstrained models was no longer significant after we relaxed the equality constraint on the stability coefficient from dependence symptoms at Year 11 to dependence symptoms at Year 16, Δχ2(13) = 20.20, p = .09. Comparison of the magnitudes of the unconstrained path for each gender indicated that the stability of dependence symptoms from Year 11 to Year 16 was stronger for women (β = .68) than for men (β = .20).

References

- Alterman AI, Bedrick J, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, Searles JS, McKay JR, Cook TG. Personality pathology and drinking in young men at high and low familial risk for alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:495–502. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ball SA, Tennen H, Poling JC, Kranzler HR, Rounsaville BJ. Personality, temperament, and character dimensions and the DSM-IV personality disorders in substance abusers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:545–553. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates ME, Labouvie EW. Personality environment constellations and alcohol use: A process oriented study of intra-individual change during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1995;9:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman B, Brismar B. Hormone levels and personality traits in abusive and suicidal male alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1994;18:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooner RK, Templer D, Svikis DS, Schmidt C, Monopolis S. Dimensions of alcoholism: A multivariate analysis. Journal of Studies. 1990;51:77–81. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Reasons for drinking alcohol: Relationships with DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses and alcohol consumption in a community sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:168–184. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Hasin DS. Drinking to cope with negative affect and DSM-IV alcohol use disorders: A test of three alternative explanations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:694–704. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Begg D, Dickson N, Harrington AL, Langley J, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Personality differences predict health-risk behaviors in young adulthood: Evidence from a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1052–1063. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Sigvardsson S, Bohman M. Childhood personality predicts alcohol abuse in young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1988;12:494–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1988.tb00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: The role of personality and affect regulatory processes. Journal of Personality. 2000;68:1058–1088. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cutter HSG, O’Farrell TJ. Relationship between reasons for drinking and customary drinking behavior. Journal of Studies o Alcoholn. 1984;45:321–325. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1984.45.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen M, Veltrup C, Wetterling T, John U, Dilling H. Axis I and Axis II comorbidity in alcohol dependence and the two types of alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:77–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller V. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Mackenzie TB, Fiszdon J, Valentiner DP, Foa E, Anderson N, Wangensteen D. The effects of alcohol consumption on laboratory-induced panic and state anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:264–270. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830030086013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty D, Kaye M. Reasons for drinking: Motivational patterns and alcohol use among college students. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9:185–188. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr. Updating Norman’s “adequate taxonomy”: Intelligence and personality dimensions in natural language and in questionnaires. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;49:710–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.49.3.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Slutske W, Taylor J, Iacono WG. Personality and substance use disorders: I. Effects of gender and alcoholism subtype. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:513–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meszaros K, Willinger U, Fischer G, Schonbeck G, Aschauer HN. The tridimensional personality model: Influencing variables in a sample of detoxified alcohol dependents. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1996;37:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, Miller KJ. The comorbidity of alcoholism and personality disorders in a clinical population: Prevalence rates and relation to alcohol typology variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:74–84. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3rd ed. Author; Los Angeles, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Newhill CE, Mulvey EP, Pilkonis PA. Initial development of a measure of emotional dysregulation for individuals with Cluster B personality disorders. Research on Social Work Practice. 2004;14:443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Pfolh B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. Author; Iowa City, IA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler LB, Bucholz KK, Compton WM. Alcohol Dependence and Abuse module from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV) Washington University School of Medicine; St. Louis: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Biological, psychological, and environmental predictors of alcoholism risk: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:485–494. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of alcoholics: A critical appraisal of theory and research. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Personality and disinhibitory psychopathology: Alcoholism and antisocial personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:92–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ. Substance use disorder and personality disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2002;4(1):25–29. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow BD, Vieth A. Personality and alcoholism: Issues, methods, and etiological processes. In: Leonard E, Blane H, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. pp. 54–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Correia CJ, Hansen CL, Christopher MS. An affective-motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:326–334. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Gallagher PE. Axis II comorbidity of substance use disorders among patients referred for treatment of personality disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:733–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Heath AC, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Stratham DJ, Martin NG. Personality and genetic risk for alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Devine H. Relations between personality and drinking motives in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2000;29:495–511. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain-drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Theakston JA, Stewart SH, Dawson MY, Knowlden-Loewen SAB, Lehman DR. Big-Five personality domains predict drinking motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:971–984. [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. DSM-III-R Personality Disorders and the Five-Factor Model of Personality: An Empirical Comparison. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:553–560. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ. Structural relations between borderline personality disorder features and putative etiological correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:471–481. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Waudby CJ, Sher KJ. Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders and personality disorder symptoms. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:65–75. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA, Burr R. A structured interview for the assessment of the five-factor model of personality: Facet-level relations to the Axis II personality disorders. Journal of Personality. 2001;69:175–198. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R, Hartgers C, Van Den Brink W, Koeter MWJ. The effect of sampling, diagnostic criteria and assessment procedures on the observed prevalence of DSM-III-R personality disorders among treated alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:227–236. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ, Clarkin JF, Sanderson C, Costa PT., Jr. A description of the DSM-IV personality disorders with the five-factor model of personality. In: Costa PT Jr., Widiger TA, editors. Personality disorders and the five-factor model of personality. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Moses HD. Emergence of alcohol problems and the several alcoholisms: A developmental perspective on etiologic theory and life course trajectory. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2. Risk, Disorder, and Adaptation. Wiley; New York: 1995. pp. 677–711. [Google Scholar]