Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the alterations in serum heat shock protein (Hsp) 70 levels during a 15-consecutive-day intermittent heat–exercise protocol in a 29-year-old male ultra marathon runner. Heat acclimation, for the purpose of physical activities in elevated ambient temperatures, has numerous physiological benefits including mechanisms such as improved cardiac output, increased plasma volume and a decreased core temperature (Tc). In addition to the central adaptations, the role of Hsp during heat acclimation has received an increasing amount of attention. The acclimation protocol applied was designed to correspond with the athlete’s tapering period for the 2007 Marathon Des Sables. The subject (VO2max = 50.7 ml·kg−1·min−1, peak power output [PPO] = 376 W) cycled daily for 90 min at a workload corresponding to 50% of VO2max in a temperature-controlled room (average WBGT = 31.9 ± 0.9°C). Venous blood was sampled before and after each session for measurement of serum osmolality and serum Hsp70. In addition, Tc, heart rate (HR) and power output (PO) was measured throughout the 90 min to ensure that heat acclimation was achieved during the 15-day period. The results show that the subject was successfully heat acclimated as seen by the lowered HR at rest and during exercise, decreased resting and exercising Tc and an increased PO. The heat exercise resulted in an initial increase in Hsp70 concentrations, known as thermotolerance, and the increase in Hsp70 after exercise was inversely correlated to the resting values of Hsp70 (Spearman’s rank correlation = −0.81, p < 0.01). Furthermore, the 15-day heat–exercise protocol also increased the basal levels of Hsp70, a response different from that of thermotolerance. This is, as far as we are aware, the first report showing Hsp70 levels during consecutive days of intermittent heat exposure giving rise to heat acclimation. In conclusion, a relatively longer heat acclimation protocol is suggested to obtain maximum benefit of heat acclimation inclusive of both cellular and systemic adaptations.

Keywords: Hsp70, Heat acclimation, Exercise, Marathon Des Sables

Introduction

Exercising in hot and humid environments is a challenge to both recreational and competitive athletes. Work performance and the threat of illness are greatest during the first week of unaccustomed heat exposure (Taylor 2006) and, therefore, illustrate the importance of heat acclimation for athletes competing in a hot environment. The physiological benefits of heat acclimation are numerous and include such mechanisms as improved cardiac output (resulting from an increased stroke volume without a compensatory increase in heart rate [HR]), increased sweat rate and plasma volume and a decreased core temperature (Tc) and mean skin temperatures at rest and during exercise (Fox et al. 1963; Wyndham et al. 1976; Shvartz et al. 1979; Buono et al. 1998; Saat et al. 2005). The reduced resting and exercise Tc increases the capacity for prolonged exercise in the heat (Shvartz et al. 1973; Buono et al. 1998; Saat et al. 2005; Thomas et al. 2006), however, the most appropriate and precise adaptation protocols for optimising heat adaptation remain debated (Armstrong et al. 1987; Houmard et al. 1990; Montain et al. 1994). The acclimation protocol applied in the current study was designed to correspond with the athlete’s tapering period for the 2007 Marathon Des Sables. Briefly, the race is a 6-day, 151-mile (243 km) endurance race across the Sahara Desert in Morocco. The race days are divided into lengths of 25, 34, 38, 82, 42 and 22 km with an average daytime temperature of up to 50°C (approximately 120°F). Participants are required to carry their own food and sleeping equipment during the race; however, they are provided with water throughout the course (the amount being dependent upon the distance covered that particular day [range 9 to 22 l·day−1]).

In addition to central and peripheral adaptations, the role of heat shock proteins (Hsp) at the cellular level during heat stress and exercise has received an increasing amount of attention (Moseley 1997; Fehrenbach et al. 2001; Walsh et al. 2001; Fehrenbach et al. 2005). It is well known that heat and exercise greatly accelerate the synthesis of the inducible Hsp, especially Hsp70 (Riabowol et al. 1988; Walsh et al. 2001; Marshall et al. 2006; Lovell et al. 2007). Hsp70 is thought to have both a cellular (Welch and Feramisco 1984) and systemic protective role (Walsh et al. 2001; Broquet et al. 2003; Hunter-Lavin et al. 2004). For example, an important role of Hsp70 is to act as molecular chaperons by binding to denatured proteins whilst acting as catalysts for the assembly of protein complexes (Beckmann et al. 1990; Morimoto et al. 1997). There have been several studies showing the up-regulation of Hsp70 during different types of exercise in normal or increased temperatures. Furthermore, a number of cross-sectional studies have suggested a role of Hsp70 in the cellular adaptation to heat acclimation (Moseley 1997; Maloyan et al. 1999; Arieli et al. 2003). However, to our knowledge, this would be the first report showing Hsp70 levels during consecutive days of intermittent heat exposure giving rise to heat acclimation. Therefore, the aim of this study was to document the alterations in the serum Hsp70 response during a 15-day heat acclimation protocol in a 29-year-old male ultra marathon runner.

Materials and methods

Subject

A male ultra marathon runner (age = 29 years, height = 177 cm, weight = 74.5 kg [pre-acclimation], VO2max = 50.7 ml·kg−1·min−1, peak power output [PPO] = 376 W, plasma osmolality = 289.1 ± 3.2 mOsm·kg−1 [average pre-exercise values during the acclimation protocol]) volunteered to complete a 15-consecutive-day heat acclimation protocol in preparation for the Marathon Des Sables. The acclimation was prescribed to coincide with the subject’s normal training load without adding any extra volume of exercise. Furthermore, the subject had no restrictions concerning food or water intake. The subject provided written informed consent in accordance with the departmental and university ethical procedures and following the principles as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The acclimation protocol was approved by the Department Ethics Committee.

Preliminary testing

The subject reported to the laboratory to undertake an incremental exercise test to exhaustion to establish both PPO and maximum HR 48 h before the initial exercise–heat exposure for purposes of prescribing the subsequent exercise intensity. Before the test, the subject was fitted with a chest strap for HR telemetry (S810i, Polar Electro, Finland), and HR was recorded beat-by-beat. The test was conducted on a SRM cycle ergometer (Schroberer Rad MeBtechnik, Germany) and began with a warm-up at 50 Watts (W) for 2 min. Thereafter, the resistance was ramped at 4 W in 10 s (equivalent to 24 W·min−1) intervals until volitional fatigue. Expired gas was sampled breath-by-breath using an automated open-circuit gas analysis system (Quark b2; Cosmed Srl, Rome, Italy). The gas analysers were calibrated immediately before the test using ambient air, assumed to contain 20.93% oxygen and 0.03% carbon dioxide, and certified standard gases containing 16.00% (SD = 0.02%) oxygen and 5.00% (SD = 0.02%) carbon dioxide (Cryoservice, Worcester, UK). The turbine flow meter used for sampling respired air flow was calibrated with a 3-l calibration syringe (Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, Missouri, USA).

Experimental design

The subject reported to the laboratory at 10.00 a.m. every morning for 15 consecutive days. At arrival, the subject was asked to provide a urine sample, after which nude body mass (NBM) was recorded (SECA Beam Pillar scale, model LS710). The subject then inserted a rectal thermistor (RECT, Model 401, Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, Missouri, USA; accuracy ±0.2°C) 10 cm past the anal sphincter for measurement of Tc. After 5 min of seated rest (allowing for postural stability), a pre-exercise blood sample was drawn by a standard venipuncture technique from the antecubital vein (Vacuette®, Greiner Bio-one, UK) for subsequent baseline analysis of serum Hsp70 concentrations and serum osmolality. Finally, baseline body temperature and HR measurements were obtained in the temperature-controlled laboratory (data was sampled with a Squirrel 1000 series data logger, Gant instruments, UK). The subject was thereafter brought to a pre-heated, temperature-controlled room (average WBGT = 31.9 ± 0.9°C) where he began the exercise trial, cycling on a friction braked (Monark, model 824E, Varberg, Sweden) cycle ergometer at 50% VO2max (75 rpm), 150 W. This intensity was maintained until the subject could not hold the cadence, and henceforth the resistance was lowered to the subject’s comfort level until completion of the 90-min protocol. The subject was allowed to freely adjust his PO to better replicate the physiological strain of the self-selected workloads characterised during ultra marathon running (Reilly et al. 2006). The subject was allowed a 5-min rest period inside the heated room after every 25 min of cycling. Room and Tc were measured continually throughout the trial. The subject was allowed to drink water ad libitum, and the total consumed volume was recorded for subsequent calculation of sweat rate (calculated as pre-NBM − post-NBM + volume of consumed water during the session)/duration of the session). Directly after the exercise trial, NBM, a urine sample and blood samples were taken as during the pre-exercise condition.

Blood samples

Venous blood was collected pre- and post-exercise into a serum separator tube (5 ml; Vacutainer® SST serum separator tube, Greiner bio-one, UK). The serum separator tubes were allowed to clot for 30 min at 4°C and thereafter centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000×g at 4°C, after which the serum was aliquoted and frozen at −80°C for subsequent analysis of serum Hsp70.

Urine and blood osmolality

The urine and plasma were measured for osmolality everyday before each trial to ensure that the subject was sufficiently euhydrated. Osmolality was determined by freezing point depression analysis (Advanced instruments, model 3320, Norwood, Massachusetts, USA).

Hsp70

Serum Hsp70 concentrations were measured by a commercially available ELISA kit (R&D systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Serum Hsp70 concentrations were quantified by interpolating the absorbance readings from a standard curve generated from a series of calibrated Hsp70 protein standards provided (R2 = 0.9986). Absorbance readings were measured at 450 nm (Biotek Synergy HT-R, Biotek Instruments, Vermont, USA). All samples were run in duplicates where after the mean was calculated and reported. All serum samples were measured for total protein using Coomassie Plus Assay Reagent (Pierce Biotechnology, New Berlin, Wisconsin, USA). A 300-μl aliquot of the Assay reagent was added to 10 μl of the samples on a 96-well microplate, and the absorbance was measured at 595 nm.

Statistical analysis

The relationship between the pre-exercise serum Hsp70 concentration and any subsequent change in serum Hsp70 concentration in response to training for each training bout was analysed using a two-tailed Spearman’s rank correlation. A non-parametric correlation was used because the Q–Q plots indicated that the normality assumption might have been violated. Conventional statistical tests can be used to analyse serial data from a single subject if autocorrelation is not substantial (Kinugasa et al. 2004). Since the Ljung–Box Q statistic at lags around one quarter along the data set were statistically insignificant, our data were not deemed to be serially dependent (SPSS 2004). Alpha was set a priori at 0.05. Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS® for Windows software (release 15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Thermoregulation, sweat rate and serum osmolality

The resting Tc decreased from 36.9°C at day 1 to 36.4°C at day 15 as shown in Fig. 1. The heat acclimation resulted in an increase in end Tc every day with an average increase of 2.4 ± 0.2°C from rest. End exercise Tc decreased from 39.2°C on day 1 to 38.9°C on day 15. The subject had the lowest end Tc (38.4°C) on day 14 (Fig. 1), although he, on that day, produced one of the highest average PO of the 15 days (150 W) (Fig. 2). The subject’s average sweat rate increased from 1.9 l·h−1 during the first 3 days to 2.5 l·h−1 in the last 3 days. The average serum osmolality was pre-exercise 289 mmol/l and post-exercise 295 mmol/l. There was no correlation between the changes in serum osmolality, sweat rate or serum Hsp70 between the days.

Fig. 1.

Thermoregulation response and cardiovascular adaptations over the acclimation period. HR at rest, Tc at rest and end Tc over the 15-day acclimation period

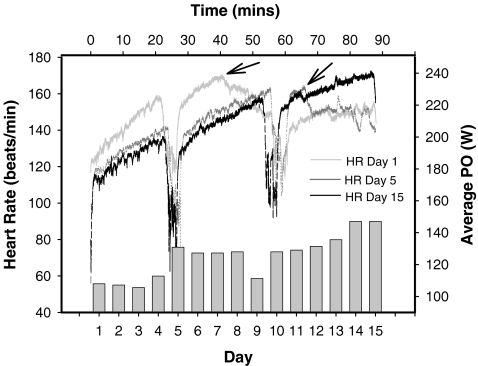

Fig. 2.

Exercise performance and cardiovascular response over the 15-day acclimation period. Representative HR data from the 90-min exercise trial are shown from days 1, 5 and 15. The subject was allowed to rest every 25 min for 5 min, as indicated by the decrease in HR at 25 and 55 min. The arrows indicate when the cadence could not be maintained and the PO was decreased. The bars in the lower part of the figure show the average PO from each of the 15 days

Heart rate

Resting HR decreased 6 beats·min−1 during the acclimation protocol as shown in Fig. 1. HR data from three representative trials (days 1, 5 and 15) are presented in Fig. 2. The data shows a clear decrease in HR during the first 40 min from day 1 compared to day 15 with a constant PO. As a result of the heat acclimation (Hargreaves and Febbraio 1998), the subject held the cadence for longer as the protocol progressed. This explains, for example, why the HR on day 15 is higher during the last 30 min compared to days 1 and 5 (Fig. 2).

Power output

Average PO over the 15-day heat acclimation is presented in Fig. 2. The subject started cycling at 50% of VO2max (75 rpm), 150 W. This intensity was, however, only maintained until the subject could not hold the cadence where after the PO was decreased. As shown in Fig. 2, the subject increased his average PO from 108 W on day 1 to 150 W on days 14 and 15. The subject maintained an output of 150 W for 40 min on day 1 before decreasing his PO stepwise, whereas he maintained an output of 150 W for the whole trial on day 15 (Fig. 2).

Hsp70

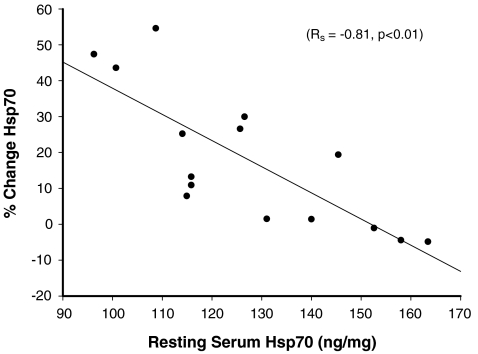

An increase in the levels of serum Hsp70 was seen after 12 out of 15 days compared to the resting values, as shown in Fig. 3 (Table 1). Figure 3 also shows that the changes between pre- and post-exercise were most pronounced during the first 5 days of the trial. The resting levels of serum Hsp70 were seen to increase over the heat acclimation period, whilst there was a significant inverse correlation between the percentage change between pre- and post-exercise and the resting serum Hsp70 levels (Spearman’s rank correlation = −0.81, p < 0.01, Fig. 4). There were no differences in total protein between the samples (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Presentation of the Hsp70 response over the 15 consecutive exercising days. The bars represent the percentage change in Hsp70 levels between resting and exercise. The line shows the resting values of Hsp70 over the 15 days

Table 1.

Serum Hsp70 values pre- and post-exercise

| Trial day | Pre-exercise (ng/ml) | Post-exercise (ng/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 108.8 | 168.0 |

| 2 | 115.9 | 131.1 |

| 3 | 125.7 | 159.0 |

| 4 | 114.1 | 142.8 |

| 5 | 96.3 | 141.9 |

| 6 | 152.7 | 150.9 |

| 7 | 158.1 | 150.9 |

| 8 | 115.0 | 124.0 |

| 9 | 131.1 | 132.9 |

| 10 | 140.1 | 141.9 |

| 11 | 126.6 | 164.4 |

| 12 | 100.8 | 144.6 |

| 13 | 115.9 | 128.4 |

| 14 | 163.5 | 155.4 |

| 15 | 145.5 | 173.5 |

Fig. 4.

The relationship between resting and change in Hsp70 concentration in response to heat exercise. It was analysed using a two-tailed Spearman’s rank correlation (Rs = −0.81, p < 0.01)

Discussion

The primary aim of this case study was to investigate the alterations in serum Hsp70 during a 15-day heat–exercise acclimation protocol on a male ultra marathon runner. We found an increase in basal levels of serum Hsp70 over the 15 days and that the increase in serum Hsp70 during exercise was inversely correlated to the resting values of serum Hsp70. This is, as far as we know, the first report showing serum Hsp70 levels during consecutive days of intermittent heat exposure.

As the primary aim of this study was to observe the serum Hsp70 response during heat acclimation, we needed to ensure that our subject was achieving the appropriate adaptations to the heat. In doing so, we continuously measured the Tc, HR, sweat rate and PO during the 15-day period. The results obtained show that the subject was successfully heat acclimated, as was seen by his lowered HR at rest and during exercise, decreased resting and exercising Tc and an increased PO (Shvartz et al. 1973; Buono et al. 1998; Saat et al. 2005).

In general, heat acclimation adaptations serve to reduce physiological strain, improve the ability to exercise in a hot environment and reduce the incidence of heat illness (Armstrong and Maresh 1991). Earlier studies have concluded that Tc is perhaps the single most critical factor for fatigue during heat stress (Nielsen et al. 1993; Gonzalez-Alonso et al. 1999). We found a reduction in resting Tc of 0.5°C, which, according to previous studies, is a substantial and an important decrease (Buono et al. 1998; Saat et al. 2005). We also found an overall decrease in end Tc of 0.3°C, which is consistent with previous studies (Wyndham et al. 1976; Saat et al. 2005).

The decrease in HR (6 beats·min−1) is also consistent with previous studies (Wyndham et al. 1976; Buono et al. 1998; Saat et al. 2005). As HR at rest and during exercise decreased, we can expect that the subject had an increased plasma volume, and subsequently, also an increased stroke volume (Wyndham et al. 1976). An expanded plasma volume will not only result in a decreased HR, it will also allow more blood to be shunted into the peripheral circulation to aid convective cooling (Patterson et al. 2004).

Hsp70

Whilst there are numerous human studies looking at Hsp70 during thermotolerance and exercise (Riabowol et al. 1988; Walsh et al. 2001; Fehrenbach et al. 2005; Marshall et al. 2006; Lovell et al. 2007), there have been very few human studies monitoring the Hsp70 response during actual heat acclimation and exercise. Thermotolerance is defined as the organism’s ability to survive an otherwise lethal heat stress from prior heat exposure, and heat acclimation is defined as the body’s ability to perform continuous work in an elevated, but non-lethal, environmental temperature (Moseley 1997). There is, however, evidence showing that thermotolerance and the long-term heat acclimation are linked and that the thermotolerance response activates long-acting cellular mechanisms (Moseley 1997; Horowitz 1998). As expected, we found an increase in serum Hsp70 after exercise during the first days of the protocol (Fehrenbach et al. 2005; Marshall et al. 2006). Furthermore, lower levels of serum Hsp70 were measured after the second day of exercise compared to the first, indicating initial desensitisation of the heat shock response, which represents the development of thermotolerance. Thus, our data is consistent with previous studies conducted on thermotolerance in humans (Riabowol et al. 1988; Walsh et al. 2001; Marshall et al. 2006; Lovell et al. 2007).

Furthermore, the increase in serum Hsp70 during exercise was inversely correlated to the resting values of serum Hsp70. Days with high pre-exercising serum Hsp70 levels generally had a smaller increase after exercise. It is interesting to note that Gjøvaag and Dahl (2006) showed the same correlation between pre-exercise values and post-exercise increase of Hsp70 in human muscles biopsies measured over 5–8 weeks of exercise (Gjovaag and Dahl 2006). A similar relationship was found by Boshoff et al. (2000) in heat shock-treated human mononuclear cells (Boshoff et al. 2000). It was hypothesised that this inverse relationship between the basal levels and the increase in Hsp70 was due to the role of Hsp70 as a negative feedback regulator in the inducible transcription of hsp70 genes through the interaction with the heat shock transcription factor (Boshoff et al. 2000). Moreover, we found that the basal levels of serum Hsp70 increased over the acclimation protocol. Similar results were found during a recent study conducted in our laboratory showing a trend towards higher basal levels of Hsp70 after 21 days of exercise–heat acclimation on six male subjects (Lovell et al, unpublished results). These results are also in agreement with previous animal studies where they have shown that heat-acclimated animals have higher basal levels of Hsp70 and an accelerated rate of Hsp70 induction when challenged to heat stress (Gehring and Wehner 1995; Horowitz et al. 1997; Maloyan et al. 1999; Arieli et al. 2003). This, therefore, allows for the conclusion that our data is indeed showing a change in the cellular response to heat acclimation, which is different from that of thermotolerance.

Possible explanations for the elevated basal Hsp70 levels have previously been suggested based on information from animal studies. One such an explanation is the dual role of heat shock proteins as chaperone and cytokine. Hsp70 acts as a chaperone during acute heat shock to, for example, protect the misfolding of proteins (Beckmann et al. 1990; Morimoto et al. 1997). It is also suggested that basal Hsp70 is up-regulated after exercise–heat acclimation to protect against delayed thermal injury by providing cytoprotection without the need for de novo protein synthesis (Maloyan et al. 1999; Horowitz 2002). Furthermore, Hsp70 when released into the circulation acts as a cytokine to activate an immune response and, therefore, plays an important role after exercise (Asea et al. 2000; Walsh et al. 2001). Hence, it could be hypothesised that the strenuous exercise conducted in this study together with the heat increases the need for higher basal Hsp70 levels to act as a cytokine and a chaperone.

Several studies and the present have shown increased levels of Hsp70 with exercise. The concentration of serum Hsp70 is a result of the release into and the uptake from the circulation. The origin of the released Hsp70 to the circulation is, however, still unknown. A variety of human cells and tissues like the brain, liver and leucocytes have been shown to increase their expression of Hsp70 in response to exercise and could, therefore, be responsible for the increase in serum Hsp70 levels (Asea et al. 2000; Fehrenbach et al. 2000; Febbraio et al. 2002; Lancaster et al. 2004). Further work is required to assess the full biological significance of the changes in extracellular Hsp70 after heat exercise.

There is a clear difference in reported serum Hsp70 values between studies (Walsh et al. 2001; Banfi et al. 2004; Marshall et al. 2006; Whitham et al. 2006), which could according to Whitham and Fortes (2006), be due to the effects of the blood handling during analysis. The reason for this is thought to be that Hsp70 are involved in chaperoning aggregated proteins and, therefore, bind to the proteins in the clotting process. Thus, the assayed serum levels of Hsp70 will be decreased (Whitham and Fortes 2006).

The findings in the present study suggest that the human Hsp70 response during heat acclimation is biphasic; an initial thermotolerance resulting in relatively high changes in Hsp70 after heat exercise and a second phase, heat acclimation, giving rise to elevated basal Hsp70 levels and only a moderate increase after heat exercise (Horowitz 1998). The results of the present study do not elucidate if the induction of serum Hsp70 is caused by heat or exercise per se. We can only assume that the increases in serum Hsp70 levels are a combination of both of them. The data further suggests that a longer heat acclimation is to be recommended (Armstrong and Maresh 1991; Voltaire et al. 2002) because the subject still had an increase in PO after 10 days, despite the fact that no extra volume of exercise was added to his training and that he was already highly trained as he had been preparing for the 2007 Marathon Des Sables for approximately 9 months.

In conclusion, this is the first report showing serum Hsp70 levels during consecutive days of intermittent heat exposure. We have shown that intermittent exercise–heat exposure gives rise to increases in the basal levels of serum Hsp70, a response different from that of thermotolerance. We also suggest that relatively longer heat acclimation protocols are beneficial to obtain the full benefit of heat acclimation inclusive of both cellular and systematic adaptations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our subject, Paul Barett, for his participation and David Hildreth for his assistance conducting this study.

References

- Arieli Y, Eynan M, Gancz H, Arieli R, Kashi Y (2003) Heat acclimation prolongs the time to central nervous system oxygen toxicity in the rat. Possible involvement of HSP72. Brain Res 962:15–20 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Armstrong LE, Maresh CM (1991) The induction and decay of heat acclimatisation in trained athletes. Sports Med 12:302–312 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Armstrong LE, Hubbard RW, DeLuca JP, Christensen EL (1987) Heat acclimatization during summer running in the northeastern United States. Med Sci Sports Exerc 19:131–136 [PubMed]

- Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt-Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW, Koo GC, Calderwood SK (2000) HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat Med 6:435–442 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Banfi G, Dolci A, Verna R, Corsi MM (2004) Exercise raises serum heat-shock protein 70 (Hsp70) levels. Clin Chem Lab Med 42:1445–1446 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beckmann RP, Mizzen LE, Welch WJ (1990) Interaction of Hsp 70 with newly synthesized proteins: implications for protein folding and assembly. Science 248:850–854 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Boshoff T, Lombard F, Eiselen R, Bornman JJ, Bachelet M, Polla BS, Bornman L (2000) Differential basal synthesis of Hsp70/Hsc70 contributes to interindividual variation in Hsp70/Hsc70 inducibility. Cell Mol Life Sci 57:1317–1325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Broquet AH, Thomas G, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Bachelet M (2003) Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J Biol Chem 278:21601–21606 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buono MJ, Heaney JH, Canine KM (1998) Acclimation to humid heat lowers resting core temperature. Am J Physiol 274:R1295–R1299 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Febbraio MA, Ott P, Nielsen HB, Steensberg A, Keller C, Krustrup P, Secher NH, Pedersen BK (2002) Exercise induces hepatosplanchnic release of heat shock protein 72 in humans. J Physiol 544:957–962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fehrenbach E, Passek F, Niess AM, Pohla H, Weinstock C, Dickhuth HH, Northoff H (2000) HSP expression in human leukocytes is modulated by endurance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32:592–600 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fehrenbach E, Niess AM, Veith R, Dickhuth HH, Northoff H (2001) Changes of HSP72-expression in leukocytes are associated with adaptation to exercise under conditions of high environmental temperature. J Leukoc Biol 69:747–754 [PubMed]

- Fehrenbach E, Niess AM, Voelker K, Northoff H, Mooren FC (2005) Exercise intensity and duration affect blood soluble HSP72. Int J Sports Med 26:552–557 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fox RH, Goldsmith R, Kidd DJ, Lewis HE (1963) Blood flow and other thermoregulatory changes with acclimatization to heat. J Physiol 166:548–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gehring WJ, Wehner R (1995) Heat shock protein synthesis and thermotolerance in Cataglyphis, an ant from the Sahara desert. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:2994–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gjovaag TF, Dahl HA (2006) Effect of training and detraining on the expression of heat shock proteins in m. triceps brachii of untrained males and females. Eur J Appl Physiol 98:310–322 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Alonso J, Teller C, Andersen SL, Jensen FB, Hyldig T, Nielsen B (1999) Influence of body temperature on the development of fatigue during prolonged exercise in the heat. J Appl Physiol 86:1032–1039 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves M, Febbraio M (1998) Limits to exercise performance in the heat. Int J Sports Med 19(Suppl 2):S115–S116 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Horowitz M (1998) Do cellular heat acclimation responses modulate central thermoregulatory activity. News Physiol Sci 13:218–225 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Horowitz M (2002) From molecular and cellular to integrative heat defense during exposure to chronic heat. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A Mol Integr Physiol 131:475–483 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Horowitz M, Maloyan A, Shlaier J (1997) HSP 70 kDa dynamics in animals undergoing heat stress superimposed on heat acclimation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 813:617–619 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Houmard JA, Costill DL, Davis JA, Mitchell JB, Pascoe DD, Robergs RA (1990) The influence of exercise intensity on heat acclimation in trained subjects. Med Sci Sports Exerc 22:615–620 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hunter-Lavin C, Davies EL, Bacelar MM, Marshall MJ, Andrew SM, Williams JH (2004) Hsp70 release from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 324:511–517 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kinugasa T, Cerin E, Hooper S (2004) Single-subject research designs and data analyses for assessing elite athletes’ conditioning. Sports Med 34:1035–1050 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lancaster GI, Moller K, Nielsen B, Secher NH, Febbraio MA, Nybo L (2004) Exercise induces the release of heat shock protein 72 from the human brain in vivo. Cell Stress Chaperones 9:276–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lovell R, Madden L, Carroll S, McNaughton L (2007) The time-profile of the PBMC HSP70 response to in vitro heat shock appears temperature-dependent. Amino Acids 33:137–144 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maloyan A, Palmon A, Horowitz M (1999) Heat acclimation increases the basal HSP72 level and alters its production dynamics during heat stress. Am J Physiol 276:R1506–R1515 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marshall HC, Ferguson RA, Nimmo MA (2006) Human resting extracellular heat shock protein 72 concentration decreases during the initial adaptation to exercise in a hot, humid environment. Cell Stress Chaperones 11:129–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Montain SJ, Sawka MN, Cadarette BS, Quigley MD, McKay JM (1994) Physiological tolerance to uncompensable heat stress: effects of exercise intensity, protective clothing, and climate. J Appl Physiol 77:216–222 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morimoto RI, Kline MP, Bimston DN, Cotto JJ (1997) The heat-shock response: regulation and function of heat-shock proteins and molecular chaperones. Essays Biochem 32:17–29 [PubMed]

- Moseley PL (1997) Heat shock proteins and heat adaptation of the whole organism. J Appl Physiol 83:1413–1417 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nielsen B, Hales JR, Strange S, Christensen NJ, Warberg J, Saltin B (1993) Human circulatory and thermoregulatory adaptations with heat acclimation and exercise in a hot, dry environment. J Physiol 460:467–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Patterson MJ, Stocks JM, Taylor NA (2004) Sustained and generalized extracellular fluid expansion following heat acclimation. J Physiol 559:327–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reilly T, Drust B, Gregson W (2006) Thermoregulation in elite athletes. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 9:666–671 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Riabowol KT, Mizzen LA, Welch WJ (1988) Heat shock is lethal to fibroblasts microinjected with antibodies against hsp70. Science 242:433–436 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saat M, Sirisinghe RG, Singh R, Tochihara Y (2005) Effects of short-term exercise in the heat on thermoregulation, blood parameters, sweat secretion and sweat composition of tropic-dwelling subjects. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Hum Sci 24:541–549 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shvartz E, Saar E, Meyerstein N, Benor D (1973) A comparison of three methods of acclimatization to dry heat. J Appl Physiol 34:214–219 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shvartz E, Bhattacharya A, Sperinde SJ, Brock PJ, Sciaraffa D, Van Beaumont W (1979) Sweating responses during heat acclimation and moderate conditioning. J Appl Physiol 46:675–680 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Taylor NA (2006) Challenges to temperature regulation when working in hot environments. Ind Health 44:331–344 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thomas MM, Cheung SS, Elder GC, Sleivert GG (2006) Voluntary muscle activation is impaired by core temperature rather than local muscle temperature. J Appl Physiol 100:1361–1369 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Voltaire B, Galy O, Coste O, Recinais S, Callis A, Blonc S, Hertogh C, Hue O (2002) Effect of fourteen days of acclimatization on athletic performance in tropical climate. Can J Appl Physiol 27:551–562 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Walsh RC, Koukoulas I, Garnham A, Moseley PL, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA (2001) Exercise increases serum Hsp72 in humans. Cell Stress Chaperones 6:386–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Welch WJ, Feramisco JR (1984) Nuclear and nucleolar localization of the 72,000-dalton heat shock protein in heat-shocked mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 259:4501–4513 [PubMed]

- Whitham M, Fortes MB (2006) Effect of blood handling on extracellular Hsp72 concentration after high-intensity exercise in humans. Cell Stress Chaperones 11:304–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Whitham M, Walker GJ, Bishop NC (2006) Effect of caffeine supplementation on the extracellular heat shock protein 72 response to exercise. J Appl Physiol 101:1222–1227 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wyndham CH, Rogers GG, Senay LC, Mitchell D (1976) Acclimization in a hot, humid environment: cardiovascular adjustments. J Appl Physiol 40:779–785 [DOI] [PubMed]