Abstract

In this study, we sought to determine the distribution and expression of heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60) in the tissues of transported piglets. A total of 24 Chinese Erhualian piglets with an average body weight of 20 ± 1 kg were assessed under both 2-h transported and normal housing conditions. Results of enzymatic analysis showed that the serum creatine kinase and aspartate aminotransferase concentrations were significantly increased in the 2-h transported piglets. Acute cellular lesions characterized by granular and vacuolar degeneration of the parenchyma cells in the tested heart, liver, and kidney were also confirmed by histopathological test after 2 h transportation. These results indicate that transport stress induces tissue damage to heart, liver, and kidney. Hsp60-positive immunostaining was consistently detected in the cytoplasm of myocardial cells, hepatocytes, renal tubular epithelial cells, and epithelial cells of fundic gland. However, results of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay indicated that Hsp60 expression was only significantly elevated in the stomach, with lower expression in the heart and a non-significant trend of increased liver and kidney expression of Hsp60. These results indicate that different tissues had different sensitivities to transport stress, possibly resulting in varying levels of cytoprotection by Hsp60 in the different tissues. The expression of Hsp60 following 2 h transportation coincided with deterioration of cardiac cytoprotection in the heart and protection in the stomach. However, the direct role of Hsp60 in cytoprotection of heart and stomach tissues needs further investigation.

Keywords: Heat shock protein 60, Stress, Degeneration, Transport, Piglets

Introduction

During transportation, factors such as vibration, crowding, mixing with other animals, lack of ventilation, and deprivation of food and water can be highly stressful. This increased stress can result in increased morbidity and mortality, leading to substantial economic loss. The stress caused to fattened pigs during loading, unloading, and road transportation for the purpose of marketing and slaughter for meat in slaughterhouses is commonly reported (Pérez et al. 2002; Gosálvez et al. 2006; Mota-Rojas et al. 2006). Young piglets are usually transported to dispersive farms after weaning, but the response and tolerance of the young piglets to transport are poorly understood. The changes in the expression of pig acute phase protein during the acute phase response after prolonged transportation of pigs under commercial conditions have been evaluated (Piñeiro et al. 2007). The heat stress response (HSR) also occurs in response to transportation and, as a signal of HSR, the expression of heat shock proteins (Hsps) may change after transportation (Van Laack et al. 1993; Li et al. 2006).

Hsps are highly conserved cellular stress proteins present in every organism from bacteria to man. Based on their molecular weight, Hsps are classified into six major families, namely, small HSPs, HSP40, HSP60, HSP70, HSP90, and HSP110 (Snoeckx et al. 2001). Different Hsps localize in different cellular compartments, e.g., Hsp27 localizes in the nucleus and cytoplasm, Hsp60 localizes in the mitochondria, and Grp78/BiP and gp96 localize in the endoplasmic reticulum (Habich and Burkart 2007). Many studies have shown the importance of Hsps for the survival of cells under stress conditions (Iwaki et al. 1993; Fehrenbach et al. 2003). Since Hsps are universal cytoprotection proteins, they may enhance the tolerance to stress, increase the survival rate of stressed cells, and may also play an important role in the emergence and development of cardiovascular diseases, organism decay, or cellular aging (Snoeckx et al. 2001; Njemini et al. 2007). A number of early reports have indicated that Hsp60 exists, in particular, in the mitochondria (Briones et al. 1997; Zhao et al. 2002), and members of the HSP60 family play roles in the folding, unfolding, and translocation of mitochondrial and cellular proteins and in the assembly of oligomeric protein complexes (Bukau and Horwich 1998; Fink 1999). Although there is growing awareness regarding the protective function of Hsps and their importance in many regulatory pathways, little is known about the expression and function of Hsp60 in tissues under conditions of transport stress, particularly its role in tissue damage. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to determine the relationship between Hsp60 localization, concentration, and tissue damage in transported piglets.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental design

Castrated Chinese Erhualian piglets were raised at the China Boar Research Center (Wuxi City, China). The piglets were housed in an area of 2.5 × 3.0 m2 and fed twice daily at 06:00 and 17:30 with free access to water. When the avoirdupois of all the piglets reached 20 ± 1 kg, they were randomly divided into two groups. Twelve piglets were maintained under normal conditions as the control group, and the other 12 were loaded onto a truck and individually housed in separate cages of a common pig transport trailer for 2 h as the transportation group. The piglets were transported at a speed of 30–40 km/h without being fed or provided with water. At the end of the journey, all the animals were administered general anesthesia (10 mg/kg of pentobarbital sodium) and killed according to normal commercial practice in a dissection room. The blood samples were collected by exsanguinations and were centrifuged at 1,200 ×g for 5 min at 4°C. The sera obtained were frozen at −20°C for further analysis. Tissue specimens (heart, liver, kidney, and stomach) for histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses were fixed in paraformaldehyde solution, and those for quantifying the levels of Hsp60 were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

The animal care and experimental procedures used in this study conformed to the regulations and guidelines of the regional Animal Ethics Committee.

Enzyme activity determination

Enzyme activity of creatine kinase (CK) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured as described by the instructions given in the commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Biochemical Reagent Co., Nanjing, China), using a clinical autoanalyzer (Vital Scientific NV, The Netherlands).

Histopathological test

Four paraformaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues were sliced serially into 4-µm sections, and one of the sections was routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H.E.) and examined using light microscopy.

The degree of alteration was evaluated through H.E. staining of all tissue specimens.

Immunohistochemistry

The paraffin-embedded 4-µm serial sections of the heart, liver, kidney, and stomach tissues of piglets from both transported and control groups were mounted on Superfrost-Plus slides. The sections were immunostained using the standard streptavidin detection system.

The slices were dewaxed through two steps of xylene washings. The deparaffinized sections were rehydrated through a graded ethanol series and then blocked in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 10 min to inhibit the endogenous peroxidase. The sections were immersed in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated in a microwave oven for 20 min for antigen retrieval. Normal goat serum (diluted ready-to-use, 85-6643, Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA) was used to block the non-immune antiserum for 20 min at room temperature in a humidified chamber. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody (SPA-806, Mouse Anti-Hsp60 Monoclonal Antibody, Stressgen Bioreagents Limited Partnership, Victoria, Canada) diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and PBS instead of primary antibody was run concurrently as the negative control. Then, the slices were incubated with a biotinylated secondary mouse antibody (85-6643, diluted ready-to-use, Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, CA, USA) for 20 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber. After that, the sections were subjected to three washes of PBS and incubated for 20 min in a horseradish peroxidase–streptavidin dilution (85-6643, diluted ready-to-use, Zymed Laboratories Inc.) according to the kit directions and washed again for 3 × 5 min in PBS. 3-3′-Diaminobenzidine (00-2014, Zymed Laboratories Inc.) was used to develop the chromogen. Nuclear counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Tissues stored at −80°C were homogenized in a chilled solution (100 mg tissues/ml) containing 0.15 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 0.1 µM E-46, 0.08 µM aprotinin, 0.1 µM leupetin, and 0.1% NP-40 (Salokhe et al. 2006) using an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer on ice. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,200 ×g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and stored at −20°C for further analysis. The frozen tissue samples were slowly defrosted in a refrigerator at 4°C before preparation for ELISA. The Hsp60 concentration was determined according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The desired number of specific antibody-coated wells (cat. no. QRCT-3230033EIA, goat anti-pig heat shock protein 60, Adlitteram Diagnostic Laboratories, USA) were secured in the holder, and standards and specimens were dispensed into appropriate wells. The biotin conjugate reagent was added to the specimens’ wells and the enzyme conjugate reagent was added to each well, gently mixed for 15 s, and incubated at 36 ± 2°C for 60 min. The incubation mixture was removed and the microtiter wells were rinsed five times with deionized water. Next, 3, 3′ 5, 5-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution was added to the wells, gently mixed for 5 s, and incubated at 36 ± 2°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding stop solution and gently mixing for 30 s. Using a microtiter plate reader, the optical density at 450 nm was read within 30 min. The average absorbance values (A450) for each set of reference standards, control, and samples were calculated. A standard curve was constructed by plotting the mean absorbance obtained for each reference standard against its concentration on a linear graph, with absorbance on the vertical (y) axis and concentration on the horizontal (x) axis. The results were expressed in nanograms per milliliter according to the calibration curve obtained with serial dilutions of a known quantity of Hsp60, and these were then normalized to the β-actin (cat. no. QRCT-3230311EIA, goat anti-pig β actin, Adlitteram Diagnostic Laboratories) content of the corresponding tissues. The procedure was performed in duplicate for each sample.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses in this investigation were completed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 13.0 software with data expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05 tested by t-test for independent samples between groups.

Results

CK and AST activity determination

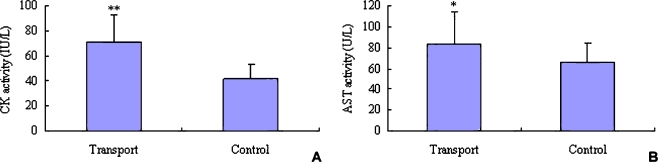

Changes in enzyme activity of CK and AST are shown in Fig. 1. After 2 h transportation, the serum CK activity was significantly higher than that of the control piglets (P < 0.01, Fig. 1a); the concentration of AST also increased in transported piglets (P < 0.05, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Changes in serum CK and AST activities in piglets. A CK activity; B AST activity. * indicates significant difference as compared to control (P < 0.05, n = 12); ** indicates significant difference as compared to control (P < 0.01, n = 12)

Histopathological test

Histopathological changes of four tested tissues (heart, liver, kidney, and stomach) are illustrated in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. After 2 h transportation, the parenchyma cells of heart, liver, and kidney showed acute degeneration characterized by enlarged cell size, and faint and lightly stained cytoplasm. Expanded intracellular spaces and numerous fine granular particles were also observed in the cytoplasm.

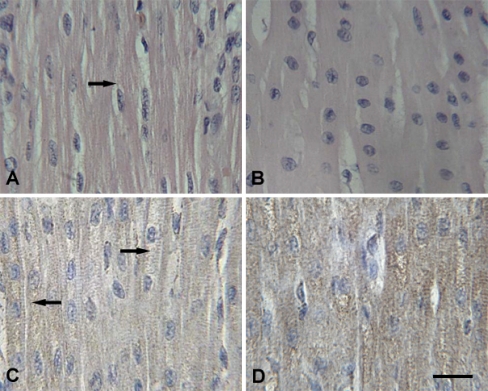

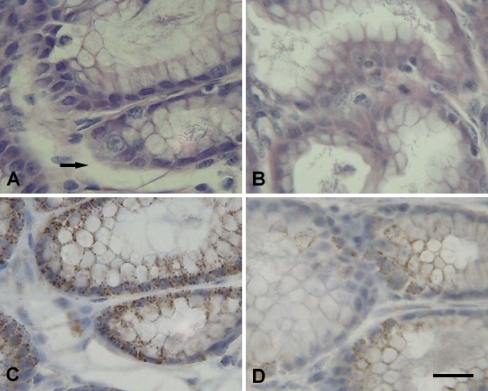

Fig. 2.

Representative photomicrographs of myocardial cells. Scale bar = 10 µm. A Granular degeneration (arrow) was observed in the cytoplasm of the myocardial fibers of transported piglets (H.E. staining). B The heart of control piglets (H.E. staining). C Positive immunolabelling of Hsp60 (arrow ←) was localized mainly in the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes (IHC staining) and Hsp60 staining was distinctly lower in the cytoplasm of granular degenerated areas (arrow →). D Hsp60 positive signals in control piglets (IHC staining)

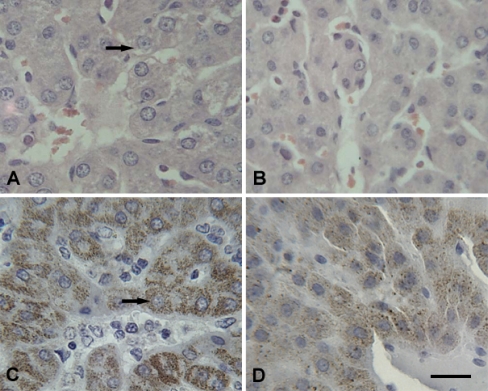

Fig. 3.

Representative photomicrographs of liver. Scale bar = 10 µm. A Granular degeneration (arrow) in hepatocytes of transported piglets was observed (H.E. staining). B The liver of control piglets (H.E. staining). C Hsp60 (arrow) was detected predominantly in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes (IHC staining) and Hsp60 staining was not well distributed in transported piglets. D Hsp60-positive signals in control piglets (IHC staining)

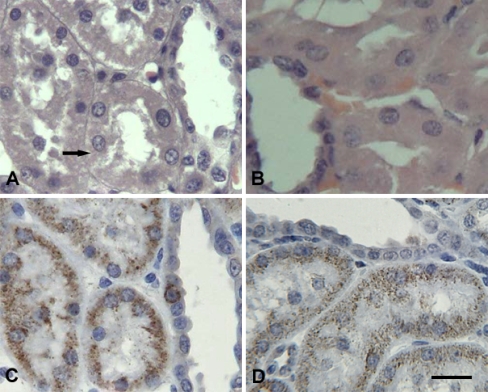

Fig. 4.

Representative photomicrographs of kidney. Scale bar = 10 µm. A Granular degeneration (arrow) was observed in the kidney of transported piglets (H.E. staining). B The kidney of control piglets (H.E. staining). C Diffuse HSP60-positive signals were observed, particularly in the basal parts of the renal tubule epithelial cells (IHC staining). D Hsp60-positive signals in control piglets (IHC staining)

Fig. 5.

Representative photomicrographs of stomach. Scale bar = 10 µm. A Acute exudation (arrow) was observed in the stomach of transported piglets (H.E. staining). B The stomach of control piglets (H.E. staining). C Positive signals were observed mainly in the basal parts of the cytoplasm, and the signal was stronger than the control piglets (IHC staining). D Hsp60-positive signals in control piglets (IHC staining)

After 2 h transportation, more fine cytoplasmic granules were found in the cytoplasm of myocardial cells of piglet hearts that were undergoing acute changes. The granular degeneration of the myocardial cells was recognized by light pink staining, tiny granular particles, and loss of striations in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2a). In the liver of 2-h transported piglets, slight granular and vacuolar degeneration was detected in the cytoplasm of hepatocytes, especially at the center of the hepatic lobule (Fig. 3a). In the kidney, the swelling of the renal tubular epithelial cells of the proximal and distal convoluted tubules showed light eosinophilic staining with fine granules and small vacuoles in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4a). Acute exudation was observed in the mucous lamina propria and submucosa of stomach of all the transported piglets after 2 h transportation (Fig. 5a).

No obvious lesions were found in the heart, liver, kidney, and stomach of control piglets (Figs. 2b, 3b, 4b, and 5b, respectively). The mean microscopic lesion scores in the collected tissue samples from all test piglets are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Microscopic lesions of tissue samples in test piglets

| Tissue type | Group | − | + | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Control (n = 12) | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transported (n = 12) | 0 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | |

| Liver | Control (n = 12) | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transported (n = 12) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| Kidney | Control (n = 12) | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transported (n = 12) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| Stomach | Control (n = 12) | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transported (n = 12) | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

“−” means no obvious pathological alteration; “+” means part of tissues have diffused granular degeneration or slight exudation in stomach; “++” means part of tissues have diffused granular degeneration and vacuolar degeneration or severe exudation in stomach; “+++” means, except granular degeneration and vacuolar degeneration, diffused cellular necrosis can also be found in the tissues; “++++” means a great quantity of severe cellular necrosis appears in the tissues

Immunohistochemistry

Immunolabelling showed that the Hsp60 was localized in the cytoplasm of parenchyma cells with very little difference between the transported groups and the control groups in Hsp60 localization in the four tested tissues. Positive Hsp60 immunostaining in the heart was largely restricted to the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes. There was an apparent decrement in the positive intracytoplasm signals of Hsp60 in the transported piglets (Fig. 2c) as compared to the control group (Fig. 2d). Hsp60 immunoreactivity was distinctly lower in the cytoplasm of the granular degenerated areas than that in the intact areas (Fig. 2c). In the liver, Hsp60-specific immunostaining was diffuse and predominantly cytoplasmic in the hepatocytes. The distribution of Hsp60 was more prominent in the hepatocytes of the transported group (Fig. 3c) compared to the control group (Fig. 3d) with stronger staining in the renal tubular epithelial cells following 2 h transportation (Fig. 4c) compared to the control piglets (Fig. 4d). Within the immunostained areas of the kidney, not all renal tubules stained to similar levels. There was higher staining in the epithelial cells of the proximal tubule than the distal tubule. Positive Hsp60 signals were diffused in the cytoplasm, particularly in the basal parts of the renal tubule epithelial cells. In the stomach, positive Hsp60 immunoreactivity was observed in some, but not all, pyloric gland cells, mainly in the basal parts of the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic Hsp60 immunoreactivity was much more prominent in the pyloric gland cells of 2 h transported piglets (Fig. 5c) than those of the control group (Fig. 5d).

ELISA results

Table 2 shows the concentrations of Hsp60 normalized to β-actin in the corresponding tissues (heart, liver, kidney, and stomach) in both of the transport and the control piglets. The results of the ELISA analysis indicated that Hsp60 expression in the heart following 2 h transport was significantly reduced (P < 0.01). In contrast, in the stomach, Hsp60 expression was significantly induced following 2 h transportation (P < 0.05). Hsp60 expression was increased in both the liver and kidney, but the differences were not significant (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

The levels of Hsp60 in the heart, liver, kidney, and stomach

| Tissue type | Group | Hsp60 (ng/ml) | β-actin (ng/ml) | Hsp60/β-actin | Changes in the Hsp60 level | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Control | 10.109 ± 3.327 | 95.461 ± 22.174 | 0.111 ± 0.04 | −62% | **<0.01 |

| Transported | 3.532 ± 1.463 | 81.462 ± 22.186 | 0.042 ± 0.016 | |||

| Liver | Control | 8.75 ± 1.695 | 86.538 ± 27.497 | 0.108 ± 0.034 | 58% | >0.05 |

| Transported | 12.865 ± 7.844 | 84.231 ± 36.34 | 0.171 ± 0.116 | |||

| Kidney | Control | 12.91 ± 1.168 | 67.385 ± 7.223 | 0.192 ± 0.015 | 9% | >0.05 |

| Transported | 15.654 ± 2.202 | 79.308 ± 15.971 | 0.209 ± 0.075 | |||

| Stomach | Control | 14.117 ± 3.184 | 60.442 ± 16.565 | 0.237 ± 0.03 | 85% | *<0.05 |

| Transported | 15.385 ± 2.75 | 35.462 ± 7.709 | 0.439 ± 0.059 |

Hsp60 expression was normalized to β-actin in four types of tissues. Significant differences were obtained for the values of control vs. transport. *stands for significance at 0.05 and **stands for significance at 0.01

Discussion

Many studies have demonstrated the importance of Hsps for the survival of cells under stress conditions in vitro (Jethmalani and Henle 1997; Verbeke et al. 2001; Hundt et al. 2007). Mammalian Hsps has induced by various ambient temperatures or environments in vivo (Fujimori et al. 1994; Kim et al. 2004). Transportation is thought to be very stressful due to exposure of the animals to unfavorable environments. This stress may induce intense physiological changes resulting in reduction in the animal’s productivity and the quality of its products (von Borell and Schäffer 2005).

Enzyme activities of CK and AST in the blood serum are often interpreted as an index of muscle damage and muscle fatigue (Fàbrega et al. 2002; Pérez et al. 2002; Li et al. 2007). CK mainly distributes in cardiac muscle fiber; when it gets pathological damage, metabolic enzyme in cardiac muscle fiber will release into the blood. CK activity in serum will strengthen rapidly (Britton et al. 1980). Increased levels of serum AST often are connected with heart and liver diseases (Wada and Kamiike 1990). The main reason of elevated AST in serum is considered as hepatic injury (Johnson et al. 1995). In the present study, we demonstrated that serum CK activity was significantly elevated following 2 h transportation compared to control piglets (P < 0.01). Serum AST concentrations were also increased in piglets (P < 0.05) following 2 h transportation. These results indicate that transport stress induced tissue damage in heart and liver. Acute cellular lesions were also observed by histopathology, with parenchyma cells of tested heart, liver, and kidney presenting with acute degeneration characterized by granular and vacuolar degeneration after 2 h transportation. Acute edema, characterized by serous exudation in the mucous lamina propria and submucosa of stomach, was observed in all transported piglets. These results demonstrate that the parenchyma cells of heart, liver, and kidney can be injured by 2 h transportation. These results are consistent with previous studies (Bao et al. 2002; Fu et al. 2004; Li et al. 2005).

Although positive immunolabelling revealed that Hsp60 was localized predominantly in the cytoplasm of cardiomyocytes, there was an obvious decreased Hsp60 immunoreactivity in the cytoplasmic areas of cardiomyocytes with the granular and vacuolar degeneration as compared to the control piglets. Quantification of Hsp60 expression using ELISA confirmed that the level of Hsp60 expression was lower in the heart of the transported piglets as compared to the control piglets (P < 0.01). This implies that Hsp60, localized in the mitochondria (Briones et al. 1997; Zhao et al. 2002), was significantly decreased after 2 h transportation and this reduced Hsp60 expression in the heart may induce intense physiological changes resulting in increased morbidity and mortality. A similar report showed that the levels of Hsp60 were attenuated in the heart of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats as compared to in the heart of the control rats (Oksala et al. 2006). The decreased expression of Hsp60 in the heart of transported piglets is in contrast to previous reports of stress-induced increases in Hsp70 both in vitro (Cumming et al. 1996) and in vivo (Schmitt et al. 2002). It has been reported that the concentration of Hsp70 was significantly higher in the heart of 2-h transported piglets than in the heart of the control piglets (Yu et al. 2007). These results imply that Hsps from different HSP families, such as Hsp70 and Hsp60, are differentially regulated in response to stress and differentially mediate cardiac cytoprotection.

Environmental stresses are very important in gastric ulcer in swine (Knežević et al. 2007). It has been reported that, 12 h after the initiation of water-immersion stress, rats were found to have acute gastric mucosal lesions and Hsp60 levels were significantly higher than that of the control rats (Fujimori et al. 1994). Sleep deprivation was also considered as a stressor, with partial sleep deprivation producing gastric lesions in the corpus or pylorus of the stomach in approximately 30–50% of the experimental rats (Guo et al. 2005). Compared to the control piglets, stressing lesions such as erosion and ulcers in the stomach have been described previously. With the exception of acute exudation in the mucous lamina propria and submucosa of stomach, they were not observed after 2 h transportation. Hsp60-positive immunoreactivity was mainly observed in the cytoplasm of pyloric gland epithelial cells of stomach with a high level of Hsp60 expression in the stomach of the transported piglets after 2 h transportation. This may be the reason that 2 h transport stress for piglets was too short to cause obvious damages or it reveals that the cells and tissues in the stomach were sufficiently protected due to overexpression of Hsp60, together with other HSP families, in the transport process. Whether Hsp60 actually protects stomach tissue from damage needs to be further investigated.

In the kidney, degenerative damage to the renal tubular epithelial cells was observed mainly in the proximal tubule. Hsp60 staining revealed that Hsp60 expression was higher in the renal tubular epithelial cells of the proximal tubule than that of the distal tubule (Fig. 4d). This is consistent with the stronger staining of the proximal convoluted tubule epithelium than that of the distal convoluted tubule in the normal human kidney as previously reported by Mallard et al. (1996). Our semi-quantitative results demonstrate that there was no significant difference in kidney Hsp60 expression between the transported piglets and the control piglets. Slight damage and stronger Hsp60 staining were also observed in the liver. Similar to streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, while the levels of Hsp60 were attenuated in the heart, Hsp60 expression was induced in the liver (Oksala et al. 2006). Although the difference was not significant, the level of Hsp60 expression in the kidney and the liver was elevated in the transported piglets. The differential induction of Hsp60 expression in the heart, liver, kidney, and stomach indicates that different tissues have varying sensitivities to transport stress, resulting in tissue-dependent cytoprotection of Hsp60.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (30430420) to Dr. Ruqian Zhao, and supported also by grants (30170682, 30571400) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

We would like to thank Hong Yu and Qiongxia Lv, College of Veterinary Medicine, Nanjing Agricultural University, for their technical advice.

References

- Bao ED, Sultan KR, Nowak B, Hartung J. Expression and localization of HSPs in the liver of transported pigs. Agric Sci China. 2002;1:690–695. [Google Scholar]

- Briones P, Vilaseca MA, Ribes A, Vernet A, Lluch M, Cusi V, Huckriede A, Agsteribbe E. A new case of multiple mitochondrial enzyme deficiencies with decreased amount of heat shock protein 60. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997;20:569–577. doi: 10.1023/A:1005303008439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton CV, Hernandez A, Roberts R. Plasma creatine kinase isoenzyme determinations in infants and children. Characterization in normal patients and after cardiac catheterization and surgery. Chest. 1980;77:758–760. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.6.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Horwich AL. The Hsp70 and Hsp60 chaperone machines. Cell. 1998;92:351–366. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming DVE, Heads RJ, Watson A, Latchman DS, Yellon DM. Differential protection of primary rat cardiocytes by transfection of specific heat stress proteins. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:2343–2349. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fàbrega E, Manteca X, Font J, Gispert M, Carrión D, Velarde A, Ruiz-de-la-Torre JL, Diestre A. Effects of halothane gene and pre-slaughter treatment on meat quality and welfare from two pig crosses. Meat Sci. 2002;62:463–472. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(02)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbach E, Veith R, Schmid M, Dickhurh HH, Northoff H, Neiss AM. Inverse response of leukocyte heat shock proteins and DNA damage to exercise and heat. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:975–982. doi: 10.1080/10715760310001595748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink AL. Chaperone-mediated protein folding. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:425–449. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XB, Sun PM, Li YB, Wang ZL, Bao ED. Tissue damages of heat-stressed broilers and expression of HSP90. J Nanjing Agric University. 2004;27:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori S, Otaka M, Itoh H, Kuwabara T, Zeniya A, Otani S, Tashima Y, Masamune O. Induction of a 60-kDa heat shock protein in rat gastric mucosa by restraint and water-immersion stress. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:544–546. doi: 10.1007/BF02361257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosálvez LF, Averós X, Valdelvira JJ, Herranz A. Influence of season, distance and mixed loads on the physical and carcass integrity of pigs transported to slaughter. Meat Sci. 2006;73:553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JS, Chau JFL, Cho CH, Koo MWL. Partial sleep deprivation compromises gastric mucosal integrity in rats. Life Sci. 2005;77:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habich C, Burkart V. Heat shock protein 60: regulatory role on innate immune cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:742–751. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt W, O’Connell-Rodwell CE, Bednarski MD, Steinbach S, Guccione S. In vitro effect of focused ultrasound or thermal stress on HSP70 expression and cell viability in three tumor cell lines. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:859–870. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki K, Chi SH, Dillmann WH, Mestril R. Induction of HSP70 in cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes by hypoxia and metabolic stress. Circulation. 1993;87:2023–2032. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jethmalani SM, Henle KJ. Intracellular distribution of stress glycoproteins in a heat-resistant cell model expressing human HSP70. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:382–387. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RD, Michael L, Conner D. Extreme serum elevations of aspartate aminotransferase. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1244–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KB, Kim MH, Lee DJ. The effect of exercise in cool, control and hot environments on cardioprotective HSP70 induction. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Hum Sci. 2004;23:225–230. doi: 10.2114/jpa.23.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knežević M, Aleksić-Kovačević S, Aleksić Z. Cell proliferation in pathogenesis of esophagogastric lesions in pigs. Int Rev Cyt. 2007;260:1–34. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)60001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LA, Xia D, Bao ED, et al. Erhualian and Pietrain pigs exhibit distinct behavioural, endocrine and biochemical responses during transport. Livest Sci. 2007;113:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2007.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li YB, Bao ED, Wang ZL, Zhao RQ. Detection of HSP mRNA transcription in transport stressed pigs by fluorescence quantitative RT-PCR. Agric Sci China. 2006;39:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Li YB, Sun PM, Wang ZL, Bao ED. Relationship between pathological lesion and distribution of HSP27 in transport stressed pigs. J Nanjing Agric University. 2005;28:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mallard K, Jones DB, Richmond J, McGill M, Foulis AK. Expression of the human heat shock protein 60 in thyroid, pancreatic, hepatic and adrenal autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:89–96. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota-Rojas D, Becerril M, Lemus C, Sánchez P, González M, Olmos SA, Ramírez R, Alonso-Spilsbury M. Effects of mid-summer transport duration on pre- and post-slaughter performance and pork quality in Mexico. Meat Sci. 2006;73:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njemini R, Bautmans I, Lambert M, Demanet C, Mets T. Heat shock proteins and chemokine/cytokine secretion profile in ageing and inflammation. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:450–454. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksala NKJ, Laaksonen DE, Lappalainen J, Khanna S, Nakao C, Hänninen O, Sen CK, Atalay M. Heat shock protein 60 response to exercise in diabetes. Effects of α-lipoic acid supplementation. J Diabetes Complications. 2006;20:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez MP, Palacia J, Santolaria MP, Aceña MC, Chacón G, Chacón M, Calvo JH, Zaragoza P, Beltran JA, García-Belenguer S. Effect of transport time on welfare and meat quality in pigs. Meat Sci. 2002;61:425–433. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(01)00216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro M, Piñeiro C, Carpintero R, Morales J, Campbell FM, Eckersall PD, Toussaint MJM, Lampreave F. Characterisation of the pig acute phase protein response to road transport. Vet J. 2007;173:669–674. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salokhe S, Sarkar A, Kulkarni A, Mukherjee S, Pal JK. Flufenoxuron, an acylurea insect growth regulator, alters development of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) by modulating levels of chitin, soluble protein content, and HSP70 and p34cdc2 in the larval tissues. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2006;85:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2005.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt JP, Schunkert H, Birnbaum DE, Aebert H. Kinetics of heat shock protein 70 synthesis in the human heart after cold cardioplegic arrest. Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg. 2002;22:415–420. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(02)00327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snoeckx LHEH, Cornelussen RN, Nieuwenhoven FA, Reneman RS, Vusse GJ. Heat shock proteins and cardiovascular pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1461–1497. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laack M, Faustman C, Sebranek JC. Pork quality and the expression of stress protein Hsp70 in swine. J Anim Sci. 1993;71:2958–2964. doi: 10.2527/1993.71112958x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke P, Clark BFC, Rattan SIS. Reduced levels of oxidized and glycoxidized proteins in human fibroblasts exposed to repeated mild heat shock during serial passaging in vitro. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1593–1602. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00752-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borell E, Schäffer D. Legal requirements and assessment of stress and welfare during transportation and pre-slaughter handling of pigs. Livest Prod Sci. 2005;97:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2005.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Kamiike W. Aspartate aminotransferase isozymes and their clinical significance. In: Ogita Z, Markert OCL, editors. Isozymes: structure, function, and use in biology and medicine, 1st ed. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1990. p. 853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Bao ED, Zhao RQ, Lv QX. Effect of transportation stress on heat shock protein 70 concentration and mRNA expression in heart and kidney tissues and serum enzyme activities and hormone concentrations of piglets. Am J Vet Res. 2007;68:1145–1150. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.68.11.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Wang JH, Levichkin IV, Stasinopoulos S, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ. A mitochondrial specific stress response in mammalian cells. The EMBO Journal. 2002;21:4411–4419. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]